Abstract

The gluconeogenesis pathway, which has been known to normally present in the liver, kidney, intestine, or muscle, has four irreversible steps catalyzed by the enzymes: pyruvate carboxylase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase, and glucose 6-phosphatase. Studies have also demonstrated evidence that gluconeogenesis exists in brain astrocytes but no convincing data have yet been found in neurons. Astrocytes exhibit significant 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-3 activity, a key mechanism for regulating glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. Astrocytes are unique in that they use glycolysis to produce lactate, which is then shuttled into neurons and used as gluconeogenic precursors for reduction. This gluconeogenesis pathway found in astrocytes is becoming more recognized as an important alternative glucose source for neurons, specifically in ischemic stroke and brain tumor. Further studies are needed to discover how the gluconeogenesis pathway is controlled in the brain, which may lead to the development of therapeutic targets to control energy levels and cellular survival in ischemic stroke patients, or inhibit gluconeogenesis in brain tumors to promote malignant cell death and tumor regression. While there are extensive studies on the mechanisms of cerebral glycolysis in ischemic stroke and brain tumors, studies on cerebral gluconeogenesis are limited. Here, we review studies done to date regarding gluconeogenesis to evaluate whether this metabolic pathway is beneficial or detrimental to the brain under these pathological conditions.

Keywords: gluconeogenesis, glycolysis, stroke, glioma, metastatic breast cancer, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, lactate, pyruvate recycling

Gluconeogenesis pathway

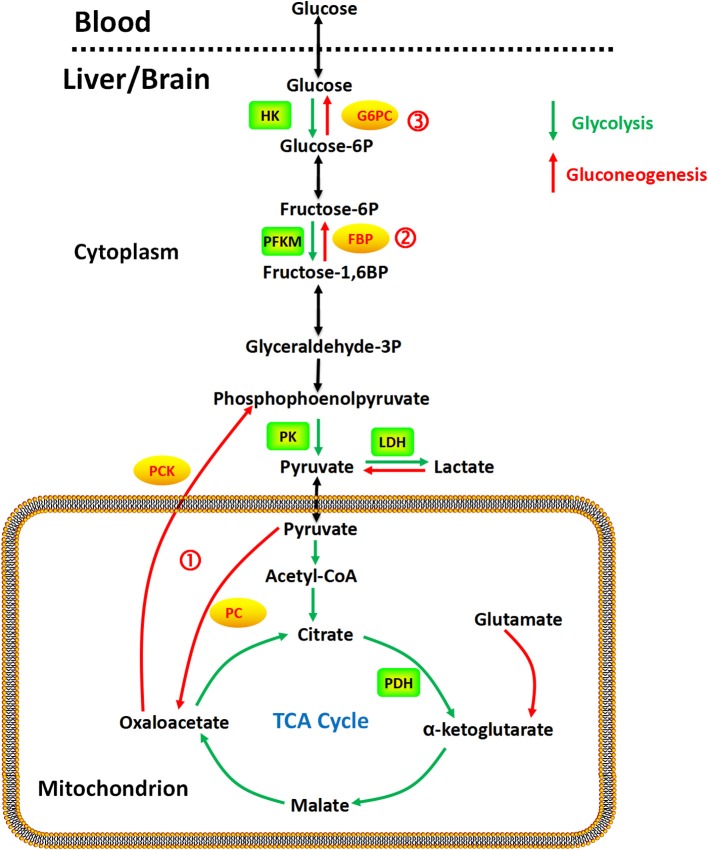

The gluconeogenesis pathway (Figure 1) has four irreversible steps catalyzed by the enzymes: pyruvate carboxylase (PC), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK), fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP), and glucose 6-phosphatase (G6PC; van den Berghe, 1996), which have been found in the liver, kidney, intestine, and muscle. In the brain, astrocytes exhibit significant 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-3 (PFKFB3) activity (Herrero-Mendez et al., 2009), a key mechanism for regulating glycolysis and gluconeogenesis through synthesis or hydrolysis of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (Hers, 1983). Gluconeogenesis in astrocytes has been demonstrated with aspartate, glutamate, alanine, and lactate as precursors (Ide et al., 1969; Phillips and Coxon, 1975; Dringen et al., 1993a; Schmoll et al., 1995). Alterations in promoter methylation of the fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase gene, which is the rate limiting enzyme in the gluconeogenic pathway, have been found in cancer cells, potentially affecting mRNA levels and expression of the enzyme (Bigl et al., 2008). No studies have found evidence of gluconeogenic activity in neurons to our knowledge.

Figure 1.

Gluconeogenesis is a multistep metabolic process that generates glucose from pyruvate or a related three-carbon compound (lactate) and glutamine. Several reversible steps in gluconeogenesis are catalyzed by the same enzymes used in glycolysis. There are three irreversible steps in the gluconeogenic pathway: (1) conversion of pyruvate to PEP via oxaloacetate, catalyzed by PC and PCK; (2) dephosphorylation of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate by FBP; and (3) dephosphorylation of glucose 6-phosphate by G6PC.

PC is a mitochondrial enzyme in the ligase class that catalyzes the irreversible carboxylation of pyruvate to oxaloacetate in the metabolic pathway of gluconeogenesis. The reaction is dependent on biotin, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and magnesium (Jitrapakdee and Wallace, 1999; Jitrapakdee et al., 2008). Acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) is the allosteric effector of PC in humans (Adina-Zada et al., 2012).

PCK is an enzyme in the lyase family that converts oxaloacetate into phosphoenolpyruvate and carbon dioxide, either in the cytosol or mitochondria via the cytosolic (PCK1) or mitochondrial (PCK2) isoforms of the enzyme, respectively. In the human liver, PCK is approximately equally distributed in the cytosol and the mitochondria (Atkin et al., 1979). Cytosolic PCK has been found with FBP in the liver, kidney, small intestine, stomach, adrenal gland, testis, and prostate. The co-localization of these two enzymes in these tissues suggest that gluconeogenesis may not be restricted to liver and kidney (Yánez et al., 2003).

FBP is a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the dephosphorylation of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate to fructose 6-phosphate and inorganic phosphate in gluconeogenesis and the Calvin cycle (Paksu et al., 2011). Two human isoforms of the enzyme have been reported in the liver and muscle (Adams et al., 1990). Both isoforms are inhibited by adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and fructose 2,6-bisphosphate, a competitive substrate inhibitor of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (Dzugaj and Kochman, 1980; el-Maghrabi et al., 1993; Tillmann and Eschrich, 1998). FBP activity is upregulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in normal monocytes (Fujisawa et al., 2000). The liver isoenzyme has also been found in the kidney, type II pneumocytes, and monocytes (Dzugaj and Kochman, 1980; Kikawa et al., 1994; Gizak et al., 2001). Human FBP has been detected in leukocytes (Sybirna et al., 2006), prostate, ovary, adrenal gland, pancreas, heart, and stomach (Yánez et al., 2003). FBP inhibitors are being investigated as potential therapy for type 2 diabetes due their capability to reduce gluconeogenesis (van Poelje et al., 2011).

G6PC is an enzyme situated in the endoplasmic reticulum and hydrolyzes glucose 6-phosphate to produce glucose and inorganic phosphate. A number of isoforms have been noted in humans, including glucose 6-phosphatase-α (G6PC), glucose 6-phosphatase-2 (G6PC2), and glucose 6-phosphatase-β (G6PC3; Hutton and O'Brien, 2009). In humans, the glucose 6-phosphatase-α (G6PC) gene is primarily expressed in the liver, kidney, intestine, and less so in pancreatic islets, although current knowledge on this gene's tissue expression and its enzyme characteristics is limited. The g6pc2 gene is predominantly expressed in pancreatic islets (Hutton and O'Brien, 2009), whereas the g6pc3 gene is ubiquitously expressed with predominance in the brain, muscle, and kidney (Martin et al., 2002).

The bifunctional 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFKFB) is responsible for phosphorylating fructose 6-phosphate to fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, which in turn activates phosphofructokinase-1 and the glycolytic pathway (Yalcin et al., 2009). Of the four PFKFB isoenzymes, PFKFB3 is distinguished by the presence of multiple AUUUA instability motifs in its 3′ untranslated region (Chesney et al., 1999), a very high kinase-to-phosphatase activity ratio (740:1; Sakakibara et al., 1997), high expression in rapidly proliferating transformed cells (Chesney et al., 1999), solid tumors and leukemias (Chesney et al., 1999; Kessler and Eschrich, 2001; Atsumi et al., 2002), and regulation by several proteins essential for tumor progression [e.g., HIF-1α (Obach et al., 2004), Akt (Manes and El-Maghrabi, 2005), and PTEN (Cordero-Espinoza and Hagen, 2013)]. Different nomenclature also recognizes two PFKFB3 isoforms, termed “inducible” and “ubiquitous” (Navarro-Sabaté et al., 2001). The inducible isoform has been shown to be induced by hypoxia. Heterozygous genomic deletion of the pfkfb3 gene has been found to reduce both the glucose metabolism and growth of tumors in mice (Telang et al., 2006).

Taken together, as shown in Figure 1, gluconeogenesis is a multistep metabolic process that generates glucose from pyruvate or a related three-carbon compound (lactate, alanine). Seven reversible steps in gluconeogenesis are catalyzed by the same enzymes used in glycolysis. There are three irreversible steps in the gluconeogenic pathway: (1) conversion of pyruvate to PEP via oxaloacetate, catalyzed by PC and PCK; (2) dephosphorylation of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate by FBP-1; and (3) dephosphorylation of glucose 6-phosphate by G6PC.

Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis in the brain

It is commonly believed that gluconeogenesis is normally present only in the liver, kidney, intestine, or muscle (Chen et al., 2015). Emerging studies, however, are showing evidence that gluconeogenic activity can also occur in the brain. While initial studies were not able to detect dephosphorylation of glucose-6-phosphate (Nelson et al., 1985; Dienel et al., 1988; Schmidt et al., 1989), subsequent studies revealed a functional G6PC complex in the brain (Bell et al., 1993; Forsyth et al., 1993; Schmoll et al., 1997) capable of hydrolyzing glucose-6-phosphate into glucose at a significant rate (Ghosh et al., 2005). Immunofluorescence studies have shown co-localization of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) with G6PC in astrocytes. While reactive astrocytes in a variety of abnormal brains were strongly G6PC positive, neoplastic astrocytes were often only weakly positive. G6PC was yet found in radial glia, neurons or oligodendroglia. Normally, astrocytes store glycogen. The demonstration that a subset of astrocytes also contain G6PC suggests that they are competent in gluconeogenesis, serving as a potential energy pathway for neurons (Bell et al., 1993). It has been suggested that G6PC may be silent under physiological conditions and become activated at times of stress (Ghosh et al., 2005). It is also possible that G6PC is not an essential enzyme for astrocytes to release glucose, and instead use a glucose concentration gradient to promote flow of glucose from astrocytes to neurons (Gandhi et al., 2009).

The interstitial microenvironment in the brain is unique. Due to the metabolic gatekeeping of astrocytes, which form bridges between neurons and blood vessels, the interstitial space is characterized by low levels of glucose (Fellows et al., 1992), high levels of glutamate (Yudkoff et al., 1993), and high levels of branched chain α-ketoacids (Daikhin and Yudkoff, 2000). After passing through the blood–brain barrier (BBB), glucose is mainly taken up and processed by astrocytes for neuronal energy requirements (Pellerin, 2008), resulting in an interstitial glucose level that is lower than that in the blood (Fellows et al., 1992; Gruetter et al., 1992). Brain glutamate consists of amino groups primarily derived from branched chain amino acids (BCAA; (Yudkoff et al., 1993)). This is made possible by neutral amino acid transporters that are highly expressed in brain endothelial cells (del Amo et al., 2008). Astrocytes then produce glutamine via transfer of an amino group from BCAA to glutamate, derived from α-ketoglutarate through the TCA cycle, with the resulting branched chain α-ketoacids released into the interstitial space and taken up by neurons for glutamine metabolism by deamination (Yudkoff et al., 1993).

Astrocytes are unique in that they use glycolysis to produce lactate, which is then shuttled into neurons and used for oxidative metabolism as yet another source of energy (Dringen et al., 1993b). Excess lactic acid is either removed via the vasculature or temporarily stored by metabolic conversion into glucose and glycogen or into alanine (Dringen et al., 1993a). Signal transduction involved in glycogen synthase (GS) activation (Hurel et al., 1996; Sung et al., 1998) aids in lactic acid conversion to glycogen in astrocytes and other cells with gluconeogenic potential (Dringen et al., 1993a; Bernard-Hélary et al., 2002). At times of high energy demand, lactate is formed as byproducts of anaerobic glycolysis by neighboring neurons, which can subsequently be used as substrates for gluconeogenesis. By retaining lactate intracellularly, lethal levels of lactic acidosis can be prevented by the use of gluconeogenic processes in astrocytes (Beckner et al., 2005).

In the liver, pyruvate is produced within the cell cytoplasm from glucose via glycolysis or conversion of alanine via alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in the Cahill cycle, which is then transported into the mitochondria (Bricker et al., 2012). Within the mitochondria, pyruvate may act as a substrate for the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex, via the oxidative pathway, to produce ATP through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and the oxidative phosphorylation reaction, or it can be taken up by PC through the gluconeogenesis pathway to produce glucose. In oxidative phosphorylation, oxidation of pyruvate to carbon dioxide involves the collaboration of the PDH complex, the TCA cycle, and the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which consumes oxygen to produce energy in the form of ATP. Under hypoxia or oxidative phosphorylation enzyme dysfunction, mitochondrial ATP production becomes interrupted. Under these circumstances, glycolysis becomes the primary source of energy, increasing the generation of lactate, an anion produced by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the last step of glycolysis. In addition, impairment of the rate-limiting enzyme (FBP) in gluconeogenesis also results in lactate accumulation, as this metabolic route represents the predominant pathway to lactate utilization.

Enzymes involved in lactate metabolism have been shown to play critical roles in cancer cell growth and survival. In patients with G6PC deficiency (von Gierke disease), a significant difference in the cerebral arterio-venous lactate concentration has been demonstrated, suggesting that lactate may be used as an energy source by the brain (Fernandes et al., 1982). In ischemic stroke, hypoxia causes accumulation of lactic acid intracellularly, resulting in inhibition of glycolysis and subsequent suppression of ATP production. Neither mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation nor anaerobic glycolysis alone can produce ATP at a sufficient rate to maintain brain function (D'Alecy et al., 1986).

To date, other enzymes involved in the gluconeogenesis pathway, such as PC and PFKFB, have yet to be elucidated in the brain.

Gluconeogenesis under pathological conditions

Gluconeogenesis has been found to play a role in several pathological conditions. In the setting of ischemic stroke, mitochondrial ATP production becomes interrupted. Glycolysis becomes the primary source of energy, increasing the generation of lactate. Glucagon, a peptide hormone that activates gluconeogenesis, has a stimulatory effect on brain mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and may play a role in neuroprotection against hypoxic damage (D'Alecy et al., 1986). High glutamate levels have been implicated to be neurotoxic in stroke, head trauma, multiple sclerosis, and neurodegenerative diseases (Matés et al., 2002). The brain interstitium also contains glutamine (Yudkoff et al., 1993) and BCAA (Yudkoff, 1997; Daikhin and Yudkoff, 2000), which can serve as energy substrates through gluconeogenesis (DeBerardinis et al., 2007) and contribute to brain cancer growth and survival. Glucose formed by hepatic gluconeogenesis may be metabolized in brain tumors and generate lactate through glycolysis (Pichumani et al., 2016). Gliomas with low levels of phosphorylated Akt have been demonstrated to respond to erlotinib (Haas-Kogan et al., 2005). While increased levels of glycolytic enzymes were found in brain cancer cells (Chen et al., 2007; Palmieri et al., 2009), enhanced glucose uptake is not a feature of breast cancer brain metastasis (Chen, 2007; Kitajima et al., 2008; Bochev et al., 2012; Manohar et al., 2013). Brain metastatic cancer cells from the breast proliferate in the absence of glucose by acquiring enhanced FBP-based gluconeogenesis capabilities (Chen et al., 2015). Furthermore, the high metabolic demand and nutrient consumption of tumor cells prevent tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) proliferation and differentiation, leading to functional impairment through suppressed IFN-γ production (Chang et al., 2013; Gubser et al., 2013) and TIL exhaustion (Ho et al., 2015). Phosphoenolpyruvate deficiency was found to increase sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)-mediated Ca2+ re-uptake, preventing Ca2+- nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) signaling and T-cell activation (Ho et al., 2015). Promoting phosphoenolpyruvate production in T cells may prove to be a promising strategy to improve the tumoricidal effects of TIL and adoptive cellular transfer (ACT) (Ho et al., 2015). Other enzymes involved in the gluconeogenesis pathway, such as PC and PFKFB, have not been well-studied in the brain under pathological conditions.

Ischemic stroke

Clinical experience and animal model studies have led to the conclusion that hypoxia initially begins with a compromise in brain function, followed by respiratory and then finally cardiovascular collapse. Lundy et al. (1984) have shown that hypoxic rats first lose brain electrical activity, have respiratory arrest ~84 s later, and then finally experience cardiovascular collapse after another 71 s. Studies done in hypoxic dogs have likewise found that brain electrical activity ceases before the animals experience cardiovascular collapse (Herin et al., 1978). Previous studies have demonstrated that elevated blood ketones increased survival times of up to five times longer in mice subjected to hypoxic conditions (Eiger et al., 1980). Similarly, butanediol-induced ketosis was associated with improved neurologic function in hypoxic rats, and exogenous glucagon further potentiated this hypoxic tolerance (Eiger et al., 1980).

Hyperglycemia during acute stress has been associated with increased mortality (Dungan et al., 2009). Glucose control improves clinical outcomes, particularly in hospitalized patients with acute myocardial infarctions, undergoing coronary bypass surgery, or patients on ventilator support (Furnary et al., 2003; Malmberg et al., 2005; Van den Berghe et al., 2006). A high proportion of patients with acute stroke may develop hyperglycemia, including those without pre-existing diabetes (Capes et al., 2000; Kent et al., 2001; McCormick et al., 2008). Multiple studies suggest that stress-induced hyperglycemia after acute stroke is associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality (Capes et al., 2000; Kent et al., 2001; McCormick et al., 2008). Stress-induced hyperglycemia has been attributed to increased stressed hormones, increased autonomic outflow from the hypothalamus or medulla, unmasking of occult diabetes mellitus, decreased plasma insulin concentrations or organ sensitivity, or damage to the glucose-regulating centers in the brain (Wass and Lanier, 1996). The toxicity of hyperglycemia does not appear to be related to the osmotic load of glucose or the direct effect of lactate, but the increase in blood glucose concentrations at the time of brain ischemia provides more substrate for anaerobic glycolysis and worsening intracellular acidosis (Pulsinelli et al., 1982). The resulting acidosis interferes with glycolysis, protein synthesis and activity, ion homeostasis, neurotransmitter release and reuptake, enzyme function, free radical production or scavenging, and stimulus-response coupling (Wass and Lanier, 1996). Previous studies have supported the point of demarcation between good and poor outcomes for glucose concentrations ranging from ~100 to 400 mg/dL (Wass and Lanier, 1996). Interestingly, while glucose-mediated exacerbation of neurological injury is well-documented in adults, it may not occur in newborns (Vannucci and Yager, 1992). Glucose pretreatment in perinatal animals have been shown to prolong survival and decrease permanent brain damage after systemic hypoxia, asphyxia, or cerebral ischemia. These studies highlight the importance of stress hyperglycemia as a pathologic factor in stroke progression, and suggests that lowering blood glucose levels after ischemic stroke may improve clinical outcome.

Glucagon levels may be elevated in stress conditions such as hypoxia and starvation. Glucagon has a direct and substrate-specific stimulatory effect on brain mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and may play a role in neuroprotection against hypoxic damage by stimulating or sustaining mitochondrial ATP production necessary for neuronal function (D'Alecy et al., 1986). Plasma glucagon levels of 0.7 μg/ml have been observed in pathological conditions such as exsanguination (Lindsey et al., 1975). Investigators have shown that systemic administration of glucagon can stimulate oxidative phosphorylation in hepatic (Siess and Wieland, 1978) and cardiac cells (Friedmann et al., 1980). Kirsch et al. (Kirsch and D'Alecy, 1984) found that glucagon enhanced the incorporation of β-hydroxybutyrate into CO2 in rat brain slices. However, D'Alecy et al. found that glucagon's stimulatory effect on ATP production is not due to direct stimulation of β-hydroxybutyrate oxidation (D'Alecy et al., 1986). Glucagon's stimulatory effect on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is thought to be mediated by adenylate cyclase activation, producing elevated cytosolic 3′,5′-cAMP and ultimately acting to stimulate electron flow between cytochrome c1 and cytochrome c (Garrison and Haynes, 1975; Halestrap, 1978; Hoosein and Gurd, 1984). Glucagon may also act directly on isolated mitochondria and specifically alter oxidative metabolism, as Yun J. et al. (2009) I-labeled monoiodoglucagon has been demonstrated to directly bind to rat brain membranes and mitochondria and alter glutamate-mediated oxidative metabolism (D'Alecy et al., 1986). Glucagon may confer neuroprotection by stimulating mitochondrial substrate oxidation and ATP production which had been initially suppressed by hypoxia.

Glutamine, a substrate used in gluconeogenesis, is a precursor molecule for glutathione, which protects against ROS toxicity. It has been shown that glutamine supplementation can maintain high levels of glutathione and subsequently avoid oxidative stress damage (Amores-Sánchez and Medina, 1999). However, on the other spectrum, high glutamate levels has been implicated to be neurotoxic in stroke, head trauma, multiple sclerosis and neurodegenerative diseases (Matés et al., 2002). It has been shown that exogenous α-tocopherol could prevent N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-induced increases in glutamine synthetase, an enzyme specific to glial cells. As α-tocopherol is an antioxidant, its involvement suggests that ROS may be associated with the glutamate excitotoxic process (Davenport Jones et al., 1998).

Hepatic gluconeogenesis activity has been demonstrated in rat models to be significantly increased in the setting of cerebral ischemia (Wang et al., 2013). In the acute phase (24 h) of stroke, rats developed higher fasting blood glucose and insulin levels in addition to the upregulation of hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression, including phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, glucose-6-phosphatase, and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (Wang et al., 2013). Hepatic gluconeogenesis-associated positive regulators, such as FoxO1, CAATT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs), and cAMP responsive element-binding protein (CREB), were also upregulated. In terms of insulin signaling transduction, the phosphorylation of insulin receptor (IR), insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS1) at the tyrosine residue, Akt, and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), were attenuated in the liver, while negative regulators such as phosphorylation of p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and IRS1 at the serine residue, were increased. In addition, the brains of rats with stroke exhibited a reduction in phosphorylation of IRS1 at the tyrosine residue and Akt. Circulating cortisol, glucagon, C-reactive protein (CRP), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), and resistin levels were elevated, but adiponectin was reduced. This suggests that cerebral ischemic stroke may modify the intracellular and extracellular environments, favoring hyperglycemia, and hepatic gluconeogenesis.

Gliomas

One of the mechanisms for cancer cell growth and survival is enhanced glucose metabolism through aerobic glycolysis, also known as the Warburg effect (Vander Heiden et al., 2009). There is a high metabolic demand in malignant tumor cells for biochemical building blocks, such as amino acids for protein synthesis, nucleic acids for gene replication, and fatty acids for phospholipid membrane barriers (Locasale and Cantley, 2011). Amino acids, such as glutamine, has been shown to be a source of energy production in gluconeogenesis (DeBerardinis et al., 2007). In advanced-stage cancers, energy may be derived from enhanced oxidation of BCAA, valine, leucine, and isoleucine (Beck and Tisdale, 1989; Pisters and Pearlstone, 1993; Baracos and Mackenzie, 2006). The brain interstitium contains high levels of glutamine (Yudkoff et al., 1993) and BCAA (Yudkoff, 1997; Daikhin and Yudkoff, 2000) which can serve as energy substrates through gluconeogenesis (DeBerardinis et al., 2007), and their abundance may contribute to brain cancer growth and survival.

A number of evidence has demonstrated that cancer consists of a subset of stem cells that may be responsible for resistance to conventional cancer therapies and promote tumor growth (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). It has been observed that cancer stem cells from glioblastomas depend on G6PC and use the enzyme to counteract glycolytic inhibition (Abbadi et al., 2014). Interestingly, the knockdown of G6PC was able to decrease the aggressive phenotype of glioblastoma stem cells, potentially through the downregulation of the CD133/AKT pathway and an increase in glycogen accumulation through activation of GS and inhibition of glycogen phosphorylase, which has been previously shown to induce cancer cell death (Lee et al., 2004; Favaro et al., 2012). G6PC knockdown also reduced migration, invasion, and cell viability (Abbadi et al., 2014). A number of studies have suggested that cancer cells have elevated levels of glycogen (Rousset et al., 1981), which is accumulated in response to hypoxic stimulation for later use in several cancer cell lines (Pelletier et al., 2012). In U87 glioma cells, glycogen accumulation induces premature cell senescence (Favaro et al., 2012).

Recent studies have found that glioblastomas and brain metastases have the capacity to oxidize acetate in the citric acid cycle (Mashimo et al., 2014), which is unexpected as there is no simple pathway for acetate to enter the lactate or pyruvate pool (Cerdan et al., 1990; Håberg et al., 1998a,b; Deelchand et al., 2009; Marin-Valencia et al., 2012). There have been studies describing “pyruvate recycling,” where acetate converts into the TCA intermediates to generate pyruvate (Cerdan et al., 1990; Cruz et al., 1998; Håberg et al., 1998a,b; Serres et al., 2007; Deelchand et al., 2009). The net synthesis of pyruvate can be achieved by malate decarboxylation to pyruvate through the activity of malic enzyme, and oxaloacetate decarboxylation through the conjugated actions of PCK and pyruvate kinase (Olstad et al., 2007). Pyruvate can then enter the TCA cycle via acetyl-CoA. Pyruvate recycling is well-described in the liver (Freidmann et al., 1971) and the kidney (Rognstad and Katz, 1972). Pyruvate recycling degrades compounds such as glutamate, glutamine, or aspartate, which are originally derived from pyruvate carboxylation, to pyruvate and reenter the TCA cycle as acetyl CoA (Olstad et al., 2007). Pyruvate recycling has been reported in rat brain following infusion of acetate (Cerdan et al., 1990; Cruz et al., 1998).

In the liver, systemic acetate may also enter the citric acid cycle. Although net synthesis of glucose from acetyl groups does not occur in mammalian liver, acetate may convert into oxaloacetate and enter gluconeogenesis. Glucose formed by hepatic gluconeogenesis may then be metabolized in brain tumors and generate lactate through glycolysis, contributing to the brain tumor lactate pool (Pichumani et al., 2016). Studies that tracked radioactively-labeled acetate revealed that the majority of lactate in brain tumors is from acetate directly metabolized in human glioblastomas and brain metastasis, contributing up to 48% of the acetyl-CoA pool (Mashimo et al., 2014; Pichumani et al., 2016). Acetate may also produce lactate elsewhere in the body and enter blood circulation to be transported to the tumor and used as an energy source. Many human tumors have elevated lactate dehydrogenase 5 (LDH5) levels, and the lactate dehydrogenase C (LDHC) gene has been found to be expressed in many tumors. Alternatively, neighboring astrocytes may convert the monocarboxylate chain of lactate to glycogen and transport to neurons as glucose (DiNuzzo et al., 2011).

Mutations in the PTEN gene have also been demonstrated to commonly occur in gliomas (Cantley and Neel, 1999; Sano et al., 1999; Zundel et al., 2000; Fan et al., 2002), leading to loss of negative regulation on the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway. This results in phosphorylation, and hence deactivation, of GS kinase-3 (GSK3) and subsequent dephosphorylation/activation of GS. When the pathway is stimulated, inactivated GSK3 is unable to interact with other kinases to constitutively inhibit GS. Decreased expression of PTEN was found in 29 of 42 (69%) of glioblastomas from human patients based on immunostains (Sano et al., 1999). A study that tested six glioblastoma specimens through immunoblotting found decreased levels of PTEN in all six samples and increased activation/phosphorylation of downstream Akt in 4 of 6 (67%) glioblastomas (Ermoian et al., 2002). Recently, phosphorylated Akt has been found in 18 of 29 (62%) glioblastoma specimens and 22 of 40 (55%) gliomas of any grade. Interestingly, none of the 22 gliomas with high levels of phosphorylated Akt responded to treatment with erlotinib, an epidermal growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. However, 8 of 18 tumors with low levels of phosphorylated Akt respond to the drug. Increased activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway was also associated with tumor progression in these specimens (Haas-Kogan et al., 2005).

Other factors include PDH, a potential mediator that protects against cancer and has been observed to reduce glioblastoma growth (Adeva et al., 2013). Mitochondrial DNA mutations have also been detected in a number of cancers. Succinate dehydrogenase genes have been shown to act as a tumor suppressor and thus mutations in these genes increases the risk of tumor progression (Adeva et al., 2013).

Brain metastatic cancer (breast cancer)

One of the driving forces behind altered energy metabolism is the factors that influence the extrinsic tissue microenvironment, such as the presence of hypoxia or hypoglycemia (Yun J. et al., 2009). These factors exist in the microenvironment during unregulated tumor expansion and to which metastatic cancer cells migrate, which may contrast the primary site where nutrients and growth factors may be more abundant (Fidler, 2003; Martinez-Outschoorn et al., 2011). There is great diversity between the microenvironments of various tissues. Cancer cells can extravasate from their primary site and reach multiple organs, but its proliferation is restricted by the secondary site's microenvironment (Fidler, 2003). The malignancy of such cancer cells is largely determined by its compatibility with the microenvironment of the host tissue. Studies have shown that tissue stromal cells can be reprogrammed to metabolize lactate secreted by cancer cells (Martinez-Outschoorn et al., 2011; Yuneva et al., 2012).

The role of various energy sources in the growth and survival of metastatic brain cancer remains to be elucidated. It has been demonstrated that mRNA of genes involved in glycolysis are elevated in brain metastatic cells (Chen et al., 2007). However, with the low glucose level in the brain's interstitium, metastatic cancer growth, and survival would require metabolic reprogramming within cancer cells, such as enhancing gluconeogenic enzyme levels, or modifications in the tissue microenvironment to take advantage of other energy sources. While increased levels of glycolytic enzymes were found in brain cancer cells (Chen et al., 2007; Palmieri et al., 2009), studies have demonstrated that enhanced glucose uptake is not a feature of breast cancer brain metastasis (Chen, 2007; Kitajima et al., 2008; Bochev et al., 2012; Manohar et al., 2013). This suggests that glucose may not be the primary or only energy source for brain metastasis.

Recently, it was found that, unlike native brain cancer cells, brain metastatic cancer cells from the breast could proliferate in the absence of glucose by acquiring enhanced gluconeogenesis capabilities, with increased oxidation of BCAA and glutamine, and upregulation of FBP (Chen et al., 2015). The study also found FBP upregulation in clinical specimens of brain metastasis and growth inhibition when FBP is knocked down in orthotopic brain metastasis formed by breast cancer cells, suggesting that activation of FBP-based gluconeogenesis is important for the growth and survival of metastatic cancer cells in the brain. The role of BCAA in metastatic brain cancer survival is further supported by studies that found higher sensitivity in tracing (Adina-Zada et al., 2012) C-BCAA for brain metastasis imaging compared to the glucose analog tracer (Tillmann and Eschrich, 1998) FDG, suggesting high levels of BCAA uptake by brain metastatic cancer cells (Chen, 2007; Kitajima et al., 2008; Bochev et al., 2012; Manohar et al., 2013).

Interestingly, in hepatocellular carcinoma, glycolytic tumors with increased (Tillmann and Eschrich, 1998) F-FDG uptake use glucose as a nutrient source for proliferation, whereas low glycolytic tumors show increased (Adina-Zada et al., 2012) C-acetate uptake accompanying lipid synthesis (Vavere et al., 2008). This has been well-correlated to histological grade, with glycolytic cancers having a higher histological grade than low glycolytic tumors (Yun M. et al., 2009). In contrast to typical glycolytic tumors, low glycolytic tumors were still able to preserve hepatic gluconeogenesis with autophagy as a supporting mechanism (Jeon et al., 2015). With the advent of modern imaging techniques such as PET, radiolabeling of glucose with (Tillmann and Eschrich, 1998) F has successfully imaged the altered metabolism of cancer, revolutionizing conventional cancer diagnosis (Xu et al., 2013).

Host-mediated immunity in malignancy

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes such as cytotoxic T cells are well-known to provide host protection against cancerous cells and infectious pathogens (Shiao et al., 2011; Braumüller et al., 2013). In tumors, however, the cytotoxic functions of TIL such as IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-17, and granzyme B production are inhibited by multiple environmental factors (Cham et al., 2008; Mellman et al., 2011; Michalek et al., 2011; Shiao et al., 2011; Finlay et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2013). Alterations in nutrient availability, such as lactate and tryptophan metabolites, in the tumor microenvironment can limit TIL activity (Yang et al., 2013). Increased expression of inhibitory checkpoint receptors, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (Lag3), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) desensitizes T cell receptor (TCR) signaling and contributes to their functional impairment (Baitsch et al., 2012), commonly referred to as “functional exhaustion” (Wherry, 2011). These discoveries have led to the development of cancer immunotherapies that reawaken exhausted TIL by blocking inhibitory checkpoint receptors and the use of ACT with tumor-specific T cells to restore the repertoire of cytotoxic T cells to eradicate tumors.

T cells undergo a metabolic switch similar to cancer cells and upregulate aerobic glycolysis and glutaminolysis for proliferation and differentiation into activated effector T cells (Ho et al., 2015). PI3K, Akt, and mTOR activation triggers the switch to anabolic metabolism by inducing transcription factors such as Myc and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1; Wang et al., 2011; MacIver et al., 2013). Anergic T cells are unable to activate Ca2+ and NFAT signaling and have diminished rates of aerobic glycolysis and anabolic metabolism following stimulation (Srinivasan and Frauwirth, 2007; Zheng et al., 2009). Similarly, CD8+ T cells with increased PD-1 expression are unable to activate mTOR or aerobic glycolysis following TCR stimulation, whereas T cells with hyper-HIF1α activity and aerobic glycolysis are refractory to functional exhaustion (Parry et al., 2005; Doedens et al., 2013; Staron et al., 2014).

It is likely that, given their similar metabolic profiles and nutrient requirements, the high metabolic demand and nutrient consumption of tumor cells prevent TIL proliferation and differentiation, leading to functional impairment. Recent studies have shown that when glycolytic rates are low, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) suppresses IFN-γ production in T cells (Chang et al., 2013; Gubser et al., 2013). Studies have also found that CD4+ T cells in tumors were deprived of glucose which resulted in diminished tumoricidal functions, suggesting that glucose deprivation might contribute to TIL exhaustion (Ho et al., 2015). Ho et al. (2015) also demonstrated increased hexokinase 2 (HK2) expression in melanoma cells that allowed for a more efficient evasion of CD4 T cell-mediated immune surveillance, indicating that competition for nutrients could exist between TIL and tumor cells. Furthermore, phosphoenolpyruvate deficiency was found to increase SERCA-mediated Ca2+ re-uptake, preventing Ca2+-NFAT signaling and T cell activation. Promoting phosphoenolpyruvate production in T cells may prove to be a promising strategy to improve the tumoricidal effects of TIL and ACT.

Conclusion and future studies

In addition to glycolysis which has been extensively studied on the mechanisms of ischemic stroke and brain tumors, studies on alternative pathways, gluconeogenesis, during such a stress conditions, are limited. It is becoming more recognized as an important pathway for alternative energy sources in the brain.

The biochemical mechanisms for astrocytes to convert from glycolysis or glycogenolysis to gluconeogenesis for neuronal energy remain to be elucidated. AMP or hexose phosphate depletion may activate FBP and suppress phosphofructokinase. A decrease in the level of fructose-2,6-biphosphate by low phosphofructokinase activity may favor lactate or glutamate for oxidative energy production and glycogen synthesis. Further studies are needed to discover how the gluconeogenesis pathway is controlled in the brain, which may lead to the development of therapeutic targets to control energy levels, and therefore cellular survival, in ischemic stroke patients or inhibit gluconeogenesis in brain tumors to promote malignant cell death and tumor regression.

Author contributions

JY participated in the study design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting and revising version to be published. XG participated in the critical revision and final approval of the version to be published. JS participated in the figure design of the version to be published. YD participated in the concept and study design, critical revision, and final approval of version to be published.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid (14GRNT20460246) (YD), Merit Review Award (I01RX-001964-01) from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation R&D Service (YD), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81501141) (XG), and Beijing NOVA program (xx2016061) (XG).

References

- Abbadi S., Rodarte J. J., Abutaleb A., Lavell E., Smith C. L., Ruff W., et al. (2014). Glucose-6-phosphatase is a key metabolic regulator of glioblastoma invasion. Mol Cancer Res. 12, 1547–1559. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0106-T [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams A., Redden C., Menahem S. (1990). Characterization of human fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase in control and deficient tissues. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 13, 829–848. 10.1007/BF01800207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeva M., González-Lucán M., Seco M., Donapetry C. (2013). Enzymes involved in l-lactate metabolism in humans. Mitochondrion 13, 615–629. 10.1016/j.mito.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adina-Zada A., Zeczycki T. N., Attwood P. V. (2012). Regulation of the structure and activity of pyruvate carboxylase by acetyl coa. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 519, 118–130. 10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amores-Sánchez M. I., Medina M. A. (1999). Glutamine, as a precursor of glutathione, and oxidative stress. Mol. Genet. Metab. 67, 100–105. 10.1006/mgme.1999.2857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin B. M., Utter M. F., Weinberg M. B. (1979). Pyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase activity in leukocytes and fibroblasts from a patient with pyruvate carboxylase deficiency. Pediatr. Res. 13, 38–43. 10.1203/00006450-197901000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsumi T., Chesney J., Metz C., Leng L., Donnelly S., Makita Z., et al. (2002). High expression of inducible 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (ipfk-2; pfkfb3) in human cancers. Cancer Res. 62, 5881–5887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baitsch L., Fuertes-Marraco S. A., Legat A., Meyer C., Speiser D. E. (2012). The three main stumbling blocks for anticancer t cells. Trends Immunol. 33, 364–372. 10.1016/j.it.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baracos V. E., Mackenzie M. L. (2006). Investigations of branched-chain amino acids and their metabolites in animal models of cancer. J. Nutr. 136, 237S–242S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck S. A., Tisdale M. J. (1989). Nitrogen excretion in cancer cachexia and its modification by a high fat diet in mice. Cancer Res. 49, 3800–3804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckner M. E., Gobbel G. T., Abounader R., Burovic F., Agostino N. R., Laterra J., et al. (2005). Glycolytic glioma cells with active glycogen synthase are sensitive to pten and inhibitors of pi3k and gluconeogenesis. Lab. Invest. 85, 1457–1470. 10.1038/labinvest.3700355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. E., Hume R., Busuttil A., Burchell A. (1993). Immunocytochemical detection of the microsomal glucose-6-phosphatase in human brain astrocytes. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 19, 429–435. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1993.tb00465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard-Hélary K., Ardourel M., Magistretti P., Hévor T., Cloix J. F. (2002). Stable transfection of cdnas targeting specific steps of glycogen metabolism supports the existence of active gluconeogenesis in mouse cultured astrocytes. Glia 37, 379–382. 10.1002/glia.10046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigl M., Jandrig B., Horn L. C., Eschrich K. (2008). Aberrant methylation of human l- and m-fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase genes in cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 720–724. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochev P., Klisarova A., Kaprelyan A., Chaushev B., Dancheva Z. (2012). Brain metastases detectability of routine whole body (18)f-fdg pet and low dose ct scanning in 2502 asymptomatic patients with solid extracranial tumors. Hell. J. Nucl. Med. 15, 125–129. 10.1967/s002449910030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braumüller H., Wieder T., Brenner E., Aßmann S., Hahn M., Alkhaled M., et al. (2013). T-helper-1-cell cytokines drive cancer into senescence. Nature 494, 361–365. 10.1038/nature11824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker D. K., Taylor E. B., Schell J. C., Orsak T., Boutron A., Chen Y. C., et al. (2012). A mitochondrial pyruvate carrier required for pyruvate uptake in yeast, drosophila, and humans. Science 337, 96–100. 10.1126/science.1218099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley L. C., Neel B. G. (1999). New insights into tumor suppression: Pten suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 4240–4245. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capes S. E., Hunt D., Malmberg K., Gerstein H. C. (2000). Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet 355, 773–778. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)08415-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdan S., Künnecke B., Seelig J. (1990). Cerebral metabolism of [1,2-13c2]acetate as detected by in vivo and in vitro 13c nmr. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 12916–12926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cham C. M., Driessens G., O'Keefe J. P., Gajewski T. F. (2008). Glucose deprivation inhibits multiple key gene expression events and effector functions in cd8+ t cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 2438–2450. 10.1002/eji.200838289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. H., Curtis J. D., Maggi L. B., Jr., Faubert B., Villarino A. V., O'sullivan D., et al. (2013). Posttranscriptional control of t cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell 153, 1239–1251. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E. I., Hewel J., Krueger J. S., Tiraby C., Weber M. R., Kralli A., et al. (2007). Adaptation of energy metabolism in breast cancer brain metastases. Cancer Res. 67, 1472–1486. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Lee H. J., Wu X., Huo L., Kim S. J., Xu L., et al. (2015). Gain of glucose-independent growth upon metastasis of breast cancer cells to the brain. Cancer Res. 75, 554–565. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. (2007). Clinical applications of pet in brain tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 48, 1468–1481. 10.2967/jnumed.106.037689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney J., Mitchell R., Benigni F., Bacher M., Spiegel L., Al-Abed Y., et al. (1999). An inducible gene product for 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase with an au-rich instability element: role in tumor cell glycolysis and the warburg effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3047–3052. 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Espinoza L., Hagen T. (2013). Increased concentrations of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate contribute to the warburg effect in phosphatase and tensin homolog (pten)-deficient cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36020–36028. 10.1074/jbc.M113.510289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz F., Scott S. R., Barroso I., Santisteban P., Cerdán S. (1998). Ontogeny and cellular localization of the pyruvate recycling system in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 70, 2613–2619. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikhin Y., Yudkoff M. (2000). Compartmentation of brain glutamate metabolism in neurons and glia. J. Nutr. 130, 1026S–1031S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alecy L. G., Myers C. L., Brewer M., Rising C. L., Shlafer M. (1986). Substrate-specific stimulation by glucagon of isolated murine brain mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Stroke 17, 305–312. 10.1161/01.STR.17.2.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport Jones J. E., Fox R. M., Atterwill C. K. (1998). Nmda-induced increases in rat brain glutamine synthetase but not glial fibrillary acidic protein are mediated by free radicals. Neurosci. Lett. 247, 37–40. 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00285-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis R. J., Mancuso A., Daikhin E., Nissim I., Yudkoff M., Wehrli S., et al. (2007). Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19345–19350. 10.1073/pnas.0709747104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deelchand D. K., Nelson C., Shestov A. A., Uğurbil K., Henry P. G. (2009). Simultaneous measurement of neuronal and glial metabolism in rat brain in vivo using co-infusion of [1,6-13c2]glucose and [1,2-13c2]acetate. J. Magn. Reson. 196, 157–163. 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Amo E. M., Urtti A., Yliperttula M. (2008). Pharmacokinetic role of l-type amino acid transporters lat1 and lat2. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 35, 161–174. 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienel G. A., Nelson T., Cruz N. F., Jay T., Crane A. M., Sokoloff L. (1988). Over-estimation of glucose-6-phosphatase activity in brain in vivo. Apparent difference in rates of [2-3h]glucose and [u-14c]glucose utilization is due to contamination of precursor pool with 14c-labeled products and incomplete recovery of 14c-labeled metabolites. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 19697–19708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNuzzo M., Maraviglia B., Giove F. (2011). Why does the brain (not) have glycogen? Bioessays 33, 319–326. 10.1002/bies.201000151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doedens A. L., Phan A. T., Stradner M. H., Fujimoto J. K., Nguyen J. V., Yang E., et al. (2013). Hypoxia-inducible factors enhance the effector responses of cd8(+) t cells to persistent antigen. Nat. Immunol. 14, 1173–1182. 10.1038/ni.2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dringen R., Schmoll D., Cesar M., Hamprecht B. (1993a). Incorporation of radioactivity from [14c]lactate into the glycogen of cultured mouse astroglial cells. Evidence for gluconeogenesis in brain cells. Biol. Chem. Hoppe Seyler 374, 343–347. 10.1515/bchm3.1993.374.1-6.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dringen R., Gebhardt R., Hamprecht B. (1993b). Glycogen in astrocytes: possible function as lactate supply for neighboring cells. Brain Res. 623, 208–214. 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91429-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dungan K. M., Braithwaite S. S., Preiser J. C. (2009). Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 373, 1798–1807. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60553-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzugaj A., Kochman M. (1980). Purification of human liver fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 614, 407–412. 10.1016/0005-2744(80)90230-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiger S. M., Kirsch J. R., D'Alecy L. G. (1980). Hypoxic tolerance enhanced by beta-hydroxybutyrate-glucagon in the mouse. Stroke 11, 513–517. 10.1161/01.STR.11.5.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Maghrabi M. R., Gidh-Jain M., Austin L. R., Pilkis S. J. (1993). Isolation of a human liver fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase cdna and expression of the protein in Escherichia coli. Role of asp-118 and asp-121 in catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 9466–9472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermoian R. P., Furniss C. S., Lamborn K. R., Basila D., Berger M. S., Gottschalk A. R., et al. (2002). Dysregulation of pten and protein kinase b is associated with glioma histology and patient survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 1100–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Aalto Y., Sanko S. G., Knuutila S., Klatzmann D., Castresana J. S. (2002). Genetic profile, pten mutation and therapeutic role of pten in glioblastomas. Int. J. Oncol. 21, 1141–1150. 10.3892/ijo.21.5.1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro E., Bensaad K., Chong M. G., Tennant D. A., Ferguson D. J., Snell C., et al. (2012). Glucose utilization via glycogen phosphorylase sustains proliferation and prevents premature senescence in cancer cells. Cell Metab. 16, 751–764. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellows L. K., Boutelle M. G., Fillenz M. (1992). Extracellular brain glucose levels reflect local neuronal activity: a microdialysis study in awake, freely moving rats. J. Neurochem. 59, 2141–2147. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J., Berger R., Smit G. P. (1982). Lactate as energy source for brain in glucose-6-phosphatase deficient child. Lancet 1, 113. 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)90257-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler I. J. (2003). The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 453–458. 10.1038/nrc1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay D. K., Rosenzweig E., Sinclair L. V., Feijoo-Carnero C., Hukelmann J. L., Rolf J., et al. (2012). Pdk1 regulation of mtor and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 integrate metabolism and migration of cd8+ t cells. J. Exp. Med. 209, 2441–2453. 10.1084/jem.20112607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth R. J., Bartlett K., Burchell A., Scott H. M., Eyre J. A. (1993). Astrocytic glucose-6-phosphatase and the permeability of brain microsomes to glucose 6-phosphate. Biochem. J. 294(Pt 1), 145–151. 10.1042/bj2940145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidmann B., Goodman E. H., Jr., Saunders H. L., Kostos V., Weinhouse S. (1971). An estimation of pyruvate recycling during gluconeogenesis in the perfused rat liver. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 143, 566–578. 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90241-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann N., Mayekar M., Wood J. M. (1980). The effects of glucagon and epinephrine on two preparations of cardiac mitochondria. Life Sci. 26, 2093–2098. 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90594-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa K., Umesono K., Kikawa Y., Shigematsu Y., Taketo A., Mayumi M., et al. (2000). Identification of a response element for vitamin d3 and retinoic acid in the promoter region of the human fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase gene. J. Biochem. 127, 373–382. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnary A. P., Gao G., Grunkemeier G. L., Wu Y., Zerr K. J., Bookin S. O., et al. (2003). Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 125, 1007–1021. 10.1067/mtc.2003.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi G. K., Cruz N. F., Ball K. K., Dienel G. A. (2009). Astrocytes are poised for lactate trafficking and release from activated brain and for supply of glucose to neurons. J. Neurochem. 111, 522–536. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06333.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison J. C., Haynes R. C. (1975). The hormonal control of gluconeogenesis by regulation of mitochondrial pyruvate carboxylation in isolated rat liver cells. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 2769–2777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A., Cheung Y. Y., Mansfield B. C., Chou J. Y. (2005). Brain contains a functional glucose-6-phosphatase complex capable of endogenous glucose production. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11114–11119. 10.1074/jbc.M410894200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizak A., Rakus D., Kolodziej J., Zabel M., Ogorzalek A., Dzugaj A. (2001). Human lung fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase is localized in pneumocytes ii. Histol. Histopathol. 16, 53–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruetter R., Novotny E. J., Boulware S. D., Rothman D. L., Mason G. F., Shulman G. I., et al. (1992). Direct measurement of brain glucose concentrations in humans by 13c nmr spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 1109–1112. 10.1073/pnas.89.3.1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubser P. M., Bantug G. R., Razik L., Fischer M., Dimeloe S., Hoenger G., et al. (2013). Rapid effector function of memory cd8+ t cells requires an immediate-early glycolytic switch. Nat. Immunol. 14, 1064–1072. 10.1038/ni.2687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas-Kogan D. A., Prados M. D., Tihan T., Eberhard D. A., Jelluma N., Arvold N. D., et al. (2005). Epidermal growth factor receptor, protein kinase b/akt, and glioma response to erlotinib. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97, 880–887. 10.1093/jnci/dji161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håberg A., Qu H., Haraldseth O., Unsgård G., Sonnewald U. (1998a). In vivo injection of [1-13c]glucose and [1,2-13c]acetate combined with ex vivo 13c nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: a novel approach to the study of middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 18, 1223–1232. 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håberg A., Qu H., Bakken I. J., Sande L. M., White L. R., Haraldseth O., et al. (1998b). In vitro and ex vivo 13c-nmr spectroscopy studies of pyruvate recycling in brain. Dev. Neurosci. 20, 389–398. 10.1159/000017335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap A. P. (1978). Stimulation of the respiratory chain of rat liver mitochondria between cytochrome c1 and cytochrome c by glucagon treatment of rats. Biochem. J. 172, 399–405. 10.1042/bj1720399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herin R. A., Hall P., Fitch J. W. (1978). Nitrogen inhalation as a method of euthanasia in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 39, 989–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Mendez A., Almeida A., Fernández E., Maestre C., Moncada S., Bola-os J. P. (2009). The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by apc/c-cdh1. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 747–752. 10.1038/ncb1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hers H. G. (1983). The control of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis by protein phosphorylation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 302, 27–32. 10.1098/rstb.1983.0035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho P. C., Bihuniak J. D., Macintyre A. N., Staron M., Liu X., Amezquita R., et al. (2015). Phosphoenolpyruvate is a metabolic checkpoint of anti-tumor t cell responses. Cell 162, 1217–1228. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoosein N. M., Gurd R. S. (1984). Identification of glucagon receptors in rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 4368–4372. 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurel S. J., Rochford J. J., Borthwick A. C., Wells A. M., Vandenheede J. R., Turnbull D. M., et al. (1996). Insulin action in cultured human myoblasts: contribution of different signalling pathways to regulation of glycogen synthesis. Biochem. J. 320(Pt 3), 871–877. 10.1042/bj3200871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton J. C., O'Brien R. M. (2009). Glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29241–29245. 10.1074/jbc.R109.025544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide T., Steinke J., Cahill G. F. (1969). Metabolic interactions of glucose, lactate, and beta-hydroxybutyrate in rat brain slices. Am. J. Physiol. 217, 784–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon J. Y., Lee H., Park J., Lee M., Park S. W., Kim J. S., et al. (2015). The regulation of glucose-6-phosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase by autophagy in low-glycolytic hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 463, 440–446. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jitrapakdee S., Wallace J. C. (1999). Structure, function and regulation of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochem. J. 340(Pt 1), 1–16. 10.1042/bj3400001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jitrapakdee S., St Maurice M., Rayment I., Cleland W. W., Wallace J. C., Attwood P. V. (2008). Structure, mechanism and regulation of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochem. J. 413, 369–387. 10.1042/BJ20080709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent T. A., Soukup V. M., Fabian R. H. (2001). Heterogeneity affecting outcome from acute stroke therapy: making reperfusion worse. Stroke 32, 2318–2327. 10.1161/hs1001.096588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R., Eschrich K. (2001). Splice isoforms of ubiquitous 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase in human brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 87, 190–195. 10.1016/S0169-328X(01)00014-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikawa Y., Inuzuka M., Takano T., Shigematsu Y., Nakai A., Yamamoto Y., et al. (1994). Cdna sequences encoding human fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase from monocytes, liver and kidney: application of monocytes to molecular analysis of human fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase deficiency. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199, 687–693. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch J. R., D'Alecy L. G. (1984). Glucagon stimulates ketone utilization by rat brain slices. Stroke 15, 324–328. 10.1161/01.STR.15.2.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima K., Nakamoto Y., Okizuka H., Onishi Y., Senda M., Suganuma N., et al. (2008). Accuracy of whole-body fdg-pet/ct for detecting brain metastases from non-central nervous system tumors. Ann. Nucl. Med. 22, 595–602. 10.1007/s12149-008-0145-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. N., Guo P., Lim S., Bassilian S., Lee S. T., Boren J., et al. (2004). Metabolic sensitivity of pancreatic tumour cell apoptosis to glycogen phosphorylase inhibitor treatment. Br. J. Cancer 91, 2094–2100. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey C. A., Faloona G. R., Unger R. H. (1975). Plasma glucagon levels during rapid exsanguination with and without adrenergic blockade. Diabetes 24, 313–316. 10.2337/diabetes.24.4.313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locasale J. W., Cantley L. C. (2011). Metabolic flux and the regulation of mammalian cell growth. Cell Metab. 14, 443–451. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy E. F., Luyckx B. A., Combs D. J., Zelenock G. B., D'Alecy L. G. (1984). Butanediol induced cerebral protection from ischemic-hypoxia in the instrumented levine rat. Stroke 15, 547–552. 10.1161/01.STR.15.3.547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIver N. J., Michalek R. D., Rathmell J. C. (2013). Metabolic regulation of t lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31, 259–283. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg K., Rydén L., Wedel H., Birkeland K., Bootsma A., Dickstein K., et al. (2005). Intense metabolic control by means of insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction (digami 2): effects on mortality and morbidity. Eur. Heart J. 26, 650–661. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manes N. P., El-Maghrabi M. R. (2005). The kinase activity of human brain 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase is regulated via inhibition by phosphoenolpyruvate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 438, 125–136. 10.1016/j.abb.2005.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar K., Bhattacharya A., Mittal B. R. (2013). Low positive yield from routine inclusion of the brain in whole-body 18f-fdg pet/ct imaging for noncerebral malignancies: results from a large population study. Nucl. Med. Commun. 34, 540–543. 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32836066c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Valencia I., Good L. B., Ma Q., Malloy C. R., Patel M. S., Pascual J. M. (2012). Cortical metabolism in pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency revealed by ex vivo multiplet (13)c nmr of the adult mouse brain. Neurochem. Int. 61, 1036–1043. 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. C., Oeser J. K., Svitek C. A., Hunter S. I., Hutton J. C., O'Brien R. M. (2002). Identification and characterization of a human cdna and gene encoding a ubiquitously expressed glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit-related protein. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 29, 205–222. 10.1677/jme.0.0290205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Outschoorn U. E., Pavlides S., Howell A., Pestell R. G., Tanowitz H. B., Sotgia F., et al. (2011). Stromal-epithelial metabolic coupling in cancer: integrating autophagy and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43, 1045–1051. 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashimo T., Pichumani K., Vemireddy V., Hatanpaa K. J., Singh D. K., Sirasanagandla S., et al. (2014). Acetate is a bioenergetic substrate for human glioblastoma and brain metastases. Cell 159, 1603–1614. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matés J. M., Pérez-Gómez C., Nú-ez de Castro I., Asenjo M., Márquez J. (2002). Glutamine and its relationship with intracellular redox status, oxidative stress and cell proliferation/death. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34, 439–458. 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00143-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M. T., Muir K. W., Gray C. S., Walters M. R. (2008). Management of hyperglycemia in acute stroke: how, when, and for whom? Stroke 39, 2177–2185. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I., Coukos G., Dranoff G. (2011). Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 480, 480–489. 10.1038/nature10673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalek R. D., Gerriets V. A., Jacobs S. R., Macintyre A. N., MacIver N. J., Mason E. F., et al. (2011). Cutting edge: distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory cd4+ t cell subsets. J. Immunol. 186, 3299–3303. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Sabaté A., Manzano A., Riera L., Rosa J. L., Ventura F., Bartrons R. (2001). The human ubiquitous 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase gene (pfkfb3): promoter characterization and genomic structure. Gene 264, 131–138. 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00591-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson T., Lucignani G., Atlas S., Crane A. M., Dienel G. A., Sokoloff L. (1985). Reexamination of glucose-6-phosphatase activity in the brain in vivo: no evidence for a futile cycle. Science 229, 60–62. 10.1126/science.2990038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obach M., Navarro-Sabaté A., Caro J., Kong X., Duran J., Gómez M., et al. (2004). 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (pfkfb3) gene promoter contains hypoxia-inducible factor-1 binding sites necessary for transactivation in response to hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 53562–53570. 10.1074/jbc.M406096200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olstad E., Olsen G. M., Qu H., Sonnewald U. (2007). Pyruvate recycling in cultured neurons from cerebellum. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 3318–3325. 10.1002/jnr.21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paksu M., Kalkan G., Asilioglu N., Paksu S., Dinler G. (2011). Gluconeogenesis defect presenting with resistant hyperglycemia and acidosis mimicking diabetic ketoacidosis. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 27, 1180–1181. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823b412d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri D., Fitzgerald D., Shreeve S. M., Hua E., Bronder J. L., Weil R. J., et al. (2009). Analyses of resected human brain metastases of breast cancer reveal the association between up-regulation of hexokinase 2 and poor prognosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 1438–1445. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry R. V., Chemnitz J. M., Frauwirth K. A., Lanfranco A. R., Braunstein I., Kobayashi S. V., et al. (2005). Ctla-4 and pd-1 receptors inhibit t-cell activation by distinct mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9543–9553. 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9543-9553.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin L. (2008). Brain energetics (thought needs food). Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 11, 701–705. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328312c368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier J., Bellot G., Gounon P., Lacas-Gervais S., Pouysségur J., Mazure N. M. (2012). Glycogen synthesis is induced in hypoxia by the hypoxia-inducible factor and promotes cancer cell survival. Front. Oncol. 2:18. 10.3389/fonc.2012.00018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M. E., Coxon R. V. (1975). Incorporation of isotopic carbon into cerebral glycogen from non-glucose substrates. Biochem. J. 146, 185–189. 10.1042/bj1460185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichumani K., Mashimo T., Vemireddy V., Kovacs Z., Ratnakar J., Mickey B., et al. (2016). Hepatic gluconeogenesis influences (13)c enrichment in lactate in human brain tumors during metabolism of [1,2-(13)c]acetate. Neurochem. Int. 97, 133–136. 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisters P. W., Pearlstone D. B. (1993). Protein and amino acid metabolism in cancer cachexia: investigative techniques and therapeutic interventions. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 30, 223–272. 10.3109/10408369309084669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsinelli W. A., Waldman S., Rawlinson D., Plum F. (1982). Moderate hyperglycemia augments ischemic brain damage: a neuropathologic study in the rat. Neurology 32, 1239–1246. 10.1212/WNL.32.11.1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rognstad R., Katz J. (1972). Gluconeogenesis in the kidney cortex. Quantitative estimation of carbon flow. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 6047–6054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset M., Zweibaum A., Fogh J. (1981). Presence of glycogen and growth-related variations in 58 cultured human tumor cell lines of various tissue origins. Cancer Res. 41, 1165–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara R., Kato M., Okamura N., Nakagawa T., Komada Y., Tominaga N., et al. (1997). Characterization of a human placental fructose-6-phosphate, 2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase. J. Biochem. 122, 122–128. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano T., Lin H., Chen X., Langford L. A., Koul D., Bondy M. L., et al. (1999). Differential expression of mmac/pten in glioblastoma multiforme: relationship to localization and prognosis. Cancer Res. 59, 1820–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K., Lucignani G., Mori K., Jay T., Palombo E., Nelson T., et al. (1989). Refinement of the kinetic model of the 2-[14c]deoxyglucose method to incorporate effects of intracellular compartmentation in brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 9, 290–303. 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmoll D., Führmann E., Gebhardt R., Hamprecht B. (1995). Significant amounts of glycogen are synthesized from 3-carbon compounds in astroglial primary cultures from mice with participation of the mitochondrial phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase isoenzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 227, 308–315. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmoll D., Houston M. P., Watkins S. L., Burchell A. (1997). Expression of constructs between the glucose-6-phosphatase promoter and a reporter gene in an insulinoma cell line: regulation by glucose, dibutyryl camp and dexamethasone. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 25:180S. 10.1042/bst025180s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serres S., Bezancon E., Franconi J. M., Merle M. (2007). Brain pyruvate recycling and peripheral metabolism: an nmr analysis ex vivo of acetate and glucose metabolism in the rat. J. Neurochem. 101, 1428–1440. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04442.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiao S. L., Ganesan A. P., Rugo H. S., Coussens L. M. (2011). Immune microenvironments in solid tumors: new targets for therapy. Genes Dev. 25, 2559–2572. 10.1101/gad.169029.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siess E. A., Wieland O. H. (1978). Glucagon-induced stimulation of 2-oxoglutarate metabolism in mitochondria from rat liver. FEBS Lett. 93, 301–306. 10.1016/0014-5793(78)81126-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M., Frauwirth K. A. (2007). Reciprocal nfat1 and nfat2 nuclear localization in cd8+ anergic t cells is regulated by suboptimal calcium signaling. J. Immunol. 179, 3734–3741. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staron M. M., Gray S. M., Marshall H. D., Parish I. A., Chen J. H., Perry C. J., et al. (2014). The transcription factor foxo1 sustains expression of the inhibitory receptor pd-1 and survival of antiviral cd8(+) t cells during chronic infection. Immunity 41, 802–814. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung C. K., Choi W. S., Scalia P. (1998). Insulin-stimulated glycogen synthesis in cultured hepatoma cells: differential effects of inhibitors of insulin signaling molecules. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 18, 243–263. 10.3109/10799899809047746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sybirna N., Dziewulska-Szwajkowska D., Barska M., Dzugaj A. (2006). Mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes show increased fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase activity in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cell Biol. Int. 30, 624–630. 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telang S., Yalcin A., Clem A. L., Bucala R., Lane A. N., Eaton J. W., et al. (2006). Ras transformation requires metabolic control by 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase. Oncogene 25, 7225–7234. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillmann H., Eschrich K. (1998). Isolation and characterization of an allelic cdna for human muscle fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Gene 212, 295–304. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00181-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berghe G., Wilmer A., Milants I., Wouters P. J., Bouckaert B., Bruyninckx F., et al. (2006). Intensive insulin therapy in mixed medical/surgical intensive care units: benefit versus harm. Diabetes 55, 3151–3159. 10.2337/db06-0855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berghe G. (1996). Disorders of gluconeogenesis. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 19, 470–477. 10.1007/BF01799108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Poelje P. D., Potter S. C., Erion M. D. (2011). Fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase inhibitors for reducing excessive endogenous glucose production in type 2 diabetes. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 203, 279–301. 10.1007/978-3-642-17214-4_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden M. G., Cantley L. C., Thompson C. B. (2009). Understanding the warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324, 1029–1033. 10.1126/science.1160809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci R. C., Yager J. Y. (1992). Glucose, lactic acid, and perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Pediatr. Neurol. 8, 3–12. 10.1016/0887-8994(92)90045-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavere A. L., Kridel S. J., Wheeler F. B., Lewis J. S. (2008). 1-11c-acetate as a pet radiopharmaceutical for imaging fatty acid synthase expression in prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 327–334. 10.2967/jnumed.107.046672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Dillon C. P., Shi L. Z., Milasta S., Carter R., Finkelstein D., et al. (2011). The transcription factor myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon t lymphocyte activation. Immunity 35, 871–882. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y., Chen C. J., Lin S. Y., Chuang Y. H., Sheu W. H., Tung K. C. (2013). Hyperglycemia is associated with enhanced gluconeogenesis in a rat model of permanent cerebral ischemia. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 367, 50–56. 10.1016/j.mce.2012.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wass C. T., Lanier W. L. (1996). Glucose modulation of ischemic brain injury: review and clinical recommendations. Mayo Clin. Proc. 71, 801–812. 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)64847-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherry E. J. (2011). T cell exhaustion. Nat. Immunol. 12, 492–499. 10.1038/ni.2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G. Z., Li C. Y., Zhao L., He Z. Y. (2013). Comparison of fdg whole-body pet/ct and gadolinium-enhanced whole-body mri for distant malignancies in patients with malignant tumors: a meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 24, 96–101. 10.1093/annonc/mds234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalcin A., Telang S., Clem B., Chesney J. (2009). Regulation of glucose metabolism by 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatases in cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 86, 174–179. 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yánez A. J., Nualart F., Droppelmann C., Bertinat R., Brito M., Concha I. I., et al. (2003). Broad expression of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase provide evidence for gluconeogenesis in human tissues other than liver and kidney. J. Cell Physiol. 197, 189–197. 10.1002/jcp.10337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Soga T., Pollard P. J. (2013). Oncometabolites: linking altered metabolism with cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3652–3658. 10.1172/JCI67228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkoff M., Nissim I., Daikhin Y., Lin Z. P., Nelson D., Pleasure D., et al. (1993). Brain glutamate metabolism: neuronal-astroglial relationships. Dev. Neurosci. 15, 343–350. 10.1159/000111354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkoff M. (1997). Brain metabolism of branched-chain amino acids. Glia 21, 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun J., Rago C., Cheong I., Pagliarini R., Angenendt P., Rajagopalan H., et al. (2009). Glucose deprivation contributes to the development of kras pathway mutations in tumor cells. Science 325, 1555–1559. 10.1126/science.1174229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun M., Bang S. H., Kim J. W., Park J. Y., Kim K. S., Lee J. D. (2009). The importance of acetyl coenzyme a synthetase for 11c-acetate uptake and cell survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Nucl. Med. 50, 1222–1228. 10.2967/jnumed.109.062703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuneva M. O., Fan T. W., Allen T. D., Higashi R. M., Ferraris D. V., Tsukamoto T., et al. (2012). The metabolic profile of tumors depends on both the responsible genetic lesion and tissue type. Cell Metab. 15, 157–170. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Delgoffe G. M., Meyer C. F., Chan W., Powell J. D. (2009). Anergic t cells are metabolically anergic. J. Immunol. 183, 6095–6101. 10.4049/jimmunol.0803510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zundel W., Schindler C., Haas-Kogan D., Koong A., Kaper F., Chen E., et al. (2000). Loss of pten facilitates hif-1-mediated gene expression. Genes Dev. 14, 391–396. 10.1101/gad.14.4.391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]