Abstract

Low antihypertensive medication adherence is common. Over recent years, the impact of low medication adherence on increased morbidity and healthcare costs has become more recognized, leading to interventions aimed at improving adherence. We analyzed a 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication between 2007 and 2012 to assess whether reductions occurred in discontinuation and low adherence. Discontinuation was defined as having no days of antihypertensive medication supply for the final 90 days of the 365 days following initiation. Low adherence was defined as having a proportion of days covered <80% during the 365 days following initiation among beneficiaries who did not discontinue treatment. Between 2007 and 2012, 41,135 Medicare beneficiaries in the 5% sample initiated antihypertensive medication. Discontinuation was stable over the study period (21.0% in 2007 and 21.3% in 2012; p-trend=0.451). Low adherence decreased from 37.4% in 2007 to 31.7% in 2012 (p-trend<0.001). After multivariable adjustment, the relative risk of low adherence for beneficiaries initiating treatment in 2012 versus in 2007 was 0.88 (95% confidence interval 0.83–0.92). Low adherence was more common among racial/ethnic minorities, beneficiaries with Medicaid buy-in (an indicator of low income), and those with polypharmacy, and was less common among females, beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication with multiple classes or a 90 day prescription fill, with dementia, a history of stroke, and those who reached the Medicare part D coverage gap in the previous year. In conclusion, low adherence to antihypertensive medication has decreased among Medicare beneficiaries however rates of discontinuation and low adherence remain high.

Keywords: Medication adherence, Medicare, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, epidemiology, risk factors, trends

Introduction

The majority of older US adults have hypertension.1 Despite the availability of effective antihypertensive medication, the prevalence of uncontrolled blood pressure (systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg) among older adults with hypertension is high.2 According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2012, 38% of US adults ≥ 60 years of age with hypertension who were taking antihypertensive medication had uncontrolled blood pressure.2

Low adherence to antihypertensive medication is common and a major contributing factor to uncontrolled blood pressure, excess healthcare costs, and increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) events among adults with hypertension.3, 4 The importance of medication adherence was noted as early as the second Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC), published in 1980.5 Over the past several decades, there have been “calls to action” to address the high incidence of discontinuation and low adherence to medications,3, 4, 6–8 and a number of randomized controlled trials evaluating interventions to improve adherence to antihypertensive medication have been conducted.3, 4, 8 Meta-analysis of these interventions suggest many are efficacious.9–11 However, there is limited consensus as to what types of interventions are superior, and it is unclear whether they have been translated into improvements in adherence among patients in clinical practice. The purpose of this study was to evaluate secular trends in antihypertensive medication discontinuation and low adherence among Medicare beneficiaries initiating treatment between 2007 and 2012. Also, we identified sociodemographic characteristics and comorbid conditions associated with antihypertensive medication discontinuation and low adherence which may be useful for guiding the development of future adherence interventions.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of Medicare beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication between 2007 and 2012 using data from a 5% random sample of beneficiaries. Medicare is a federally funded insurance program that provides healthcare coverage to US adults 65 years of age and older, who are disabled, or with end-stage renal disease. De-identified data on Medicare beneficiaries, including inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drug claims, were obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Use of these data was approved by CMS and by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board.

Initiation was defined by the first claim for antihypertensive medication between 2007 and 2012. To ensure complete data capture for defining antihypertensive medication initiation and adherence, we restricted the analyses to beneficiaries with inpatient (Medicare Part A), outpatient (Medicare Part B) and pharmacy (Medicare Part D) coverage from the 365 days prior to their first antihypertensive medication fill during the study period (i.e., look-back period) to 365 days following initiation (i.e., follow-up period). As Medicare claims are not complete for beneficiaries with Medicare Part C coverage (Medicare Advantage), beneficiaries who had Part C coverage at any point during the look-back or follow-up period were excluded from all analyses. To confirm that beneficiaries were not prevalent users of antihypertensive medication, we restricted our analyses to beneficiaries with no claims for antihypertensive medication fills during the look-back period. To increase the likelihood that the antihypertensive medication was being used to lower blood pressure, we required beneficiaries to have ≥ 2 outpatient claims linked to physician evaluation and management codes, ≥ 7 days apart, with International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses of 401.x (malignant, benign or unspecified essential hypertension) during the look-back period. We excluded beneficiaries who were < 65 years of age at the start of the 365 day look-back period as these beneficiaries are not representative of the general Medicare population.

Antihypertensive medication fills

We identified prescription antihypertensive medication fills using claims in the Medicare Part D file. Antihypertensive medication classes included aldosterone receptor antagonists, alpha blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), beta blockers (BB), calcium channel blockers (CCB), central acting agents, direct vasodilators, diuretics (thiazide, loop, and potassium-sparing, separately), and renin inhibitors. All antihypertensive medication classes filled within 7 days of the first claim for antihypertensive medication (index fill), were considered as part of a beneficiary’s initial treatment regimen. Beneficiaries were further categorized as initiating antihypertensive treatment with a single class, multiclass/multiple pill, or multiclass/combination therapy. Combination therapy was defined as initiating treatment with one pill containing multiple antihypertensive classes.

Outcomes

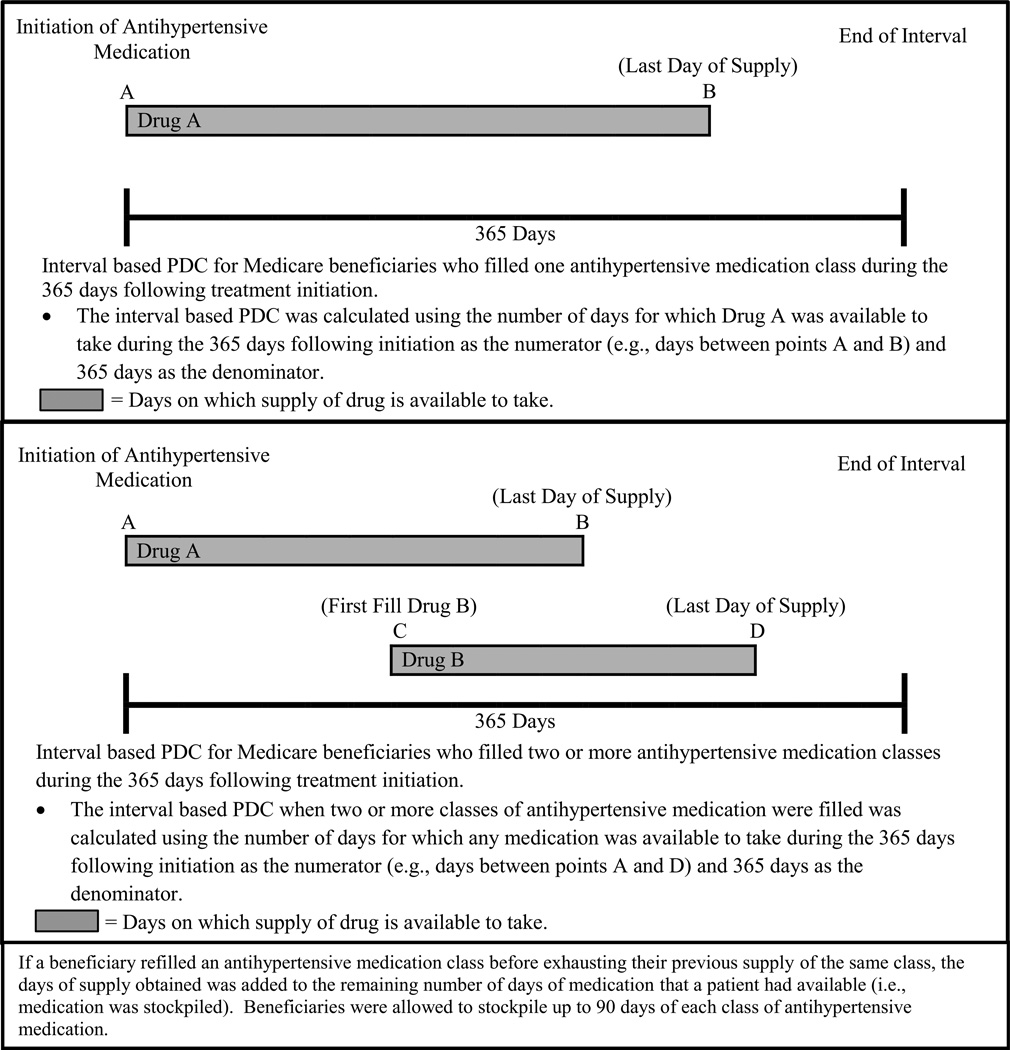

Discontinuation was defined as having no days of antihypertensive medication available to take during the final 90 days of the 365 days following treatment initiation.12 Antihypertensive medication adherence was calculated by assessing the interval-based proportion of days covered (PDC).13 The PDC was calculated using the number of days for which medication was available to take during the 365 days following initiation as the numerator and 365 days as the denominator (Figure 1, Top Panel).13, 14 For beneficiaries who filled more than one class of antihypertensive medication in the 365 days following initiation, we calculated the PDC counting days with any medication available to take in the numerator and 365 days as the denominator (Figure 1, Bottom Panel). Low adherence was defined by a PDC < 80%.13, 14 A PDC < 80% has been associated with increased mortality risk15 and is the convention for studies of adherence to antihypertensive medication.3, 13, 16

Figure 1.

Interval based proportion of days covered (PDC) calculation method for defining medication adherence among beneficiaries on one class of antihypertensive medication (Top Panel) and two or more classes of antihypertensive medication (Bottom Panel).

Covariates

We selected covariates, a priori, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, dementia, depression, diabetes, coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, chronic kidney disease (CKD), heart failure (HF), a serious fall injury, polypharmacy, initiating antihypertensive medication with a 90 day prescription, and entering the Medicare Part D coverage gap. Polypharmacy was defined as having fills for ≥10 different medications. We also used Medicaid buy-in, payments of Medicare premiums by Medicaid, as a marker of low-income status. We utilized previously published algorithms and claims data to define these covariates during the look-back period (Table S1). We also separately assessed incident co-morbid conditions and having Medicaid buy-in, polypharmacy, and entering the Medicare Part D coverage gap during the 182 days following initiation, as development of these factors may influence medication taking behavior.

Statistical analyses

We calculated characteristics of beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication in each calendar year from 2007 through 2012. For each year, we also calculated the percentage of beneficiaries who discontinued antihypertensive medication and, among those who did not discontinue treatment, had low adherence in the 365 days following initiation. Discontinuation and low adherence were calculated for the overall population and in subgroups defined by age (66–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, ≥85 years), sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian, other), antihypertensive medication classes initiated, and initiating treatment with multiple drug classes or a 90 day prescription. We assessed linear trends across calendar year using Poisson regression for dichotomous variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Next, we calculated risk ratios (RR) for antihypertensive medication discontinuation and, separately, low adherence associated with calendar year of initiation and the variables listed in the study covariates section above. After calculating unadjusted RRs, we conducted a second model including multivariable adjustment for all variables in the look-back period simultaneously. We also conducted a third multivariable model adjusting for all variables in the second model and variables from the 182 days following antihypertensive medication initiation as described above. To avoid co-linearity, each antihypertensive medication class was evaluated in separate regression models with beneficiaries initiating an antihypertensive medication class being compared to beneficiaries initiating treatment without that class.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, we required beneficiaries to have ≥ 1 claim, versus ≥ 2 claims in the main analyses, for a diagnosis of hypertension in the look-back period. Second, we defined discontinuation as having no antihypertensive medication available to take during the final 60 days, versus 90 days in the main analysis, of follow-up. Third, we restricted the population to beneficiaries without a history of CHD, HF, diabetes or CKD because beneficiaries with these conditions may be prescribed antihypertensive medication for reasons other than hypertension. Fourth, as loop diuretics are often used for reasons other than hypertension, we excluded loop diuretics as an antihypertensive medication. Fifth, we excluded beneficiaries who had a claim for a skilled nursing facility stay during the look-back or follow-up period from analyses since these beneficiaries may have incomplete pharmacy claims. For low adherence, we also included a sixth sensitivity analysis using the prescription-based PDC method.13 In a final analysis, we calculated the percentage of beneficiaries who discontinued antihypertensive medication or had low adherence, pooled together, utilizing the interval-based PDC calculation in each calendar year. The RR of discontinuation or low adherence pooled together over calendar years was also calculated. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Between 2007 and 2012, we identified 41,135 Medicare beneficiaries in the 5% sample who met the eligibility criteria for the current analysis and initiated antihypertensive medication. Across the years studied, the mean age of beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication ranged from 75.9 to 76.7 years (Table 1). The percentage of those who initiated antihypertensive medication that were men and white increased between 2007 and 2012. The percentage of beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication with thiazide diuretics or combination therapy decreased. Initiation of prescriptions with a 90 day supply nearly doubled over the study time frame. A prior diagnosis of diabetes, CHD, CKD, depression, and polypharmacy increased, while Medicaid buy-in decreased, between 2007 and 2012.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication, by calendar year.

| Calendar Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 2007 n=6,350 |

2008 n=7,379 |

2009 n=7,083 |

2010 n=6,947 |

2011 n=6,749 |

2012 n=6,627 |

p-trend |

| Mean age, years | 76.6 (7.4) | 76.7 (7.5) | 76.3 (7.3) | 76.0 (7.4) | 75.9 (7.5) | 76.2 (7.5) | <0.001 |

| Age group, years | |||||||

| 65–69 | 20.6 | 20.4 | 22.0 | 23.5 | 25.1 | 23.2 | <0.001 |

| 70–74 | 24.4 | 24.8 | 24.6 | 25.4 | 24.4 | 25.5 | 0.264 |

| 75–79 | 21.7 | 20.4 | 20.2 | 19.7 | 19.3 | 19.2 | <0.001 |

| 80–84 | 17.5 | 17.0 | 17.8 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 15.9 | <0.001 |

| 85+ | 15.9 | 17.4 | 15.3 | 15.1 | 15.6 | 16.3 | 0.267 |

| Male | 36.5 | 37.1 | 38.3 | 39.6 | 40.4 | 40.7 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 80.6 | 81.8 | 82.1 | 83.4 | 83.9 | 83.7 | <0.001 |

| Black | 10.1 | 9.7 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.5 | <0.001 |

| Asian | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 0.072 |

| Other | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.272 |

| Antihypertensive drug class initiated |

|||||||

| Thiazide-type diuretic | 23.9 | 24.2 | 23.0 | 21.9 | 21.7 | 21.1 | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 17.8 | 17.7 | 17.1 | 16.6 | 16.9 | 18.3 | 0.913 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor |

32.6 | 30.5 | 32.7 | 32.6 | 34.1 | 32.6 | 0.018 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker |

14.8 | 15.4 | 14.7 | 15.0 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 0.034 |

| Loop diuretic | 10.5 | 10.9 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 0.486 |

| Beta blocker | 26.6 | 26.2 | 26.0 | 26.9 | 26.5 | 27.6 | 0.114 |

| Other | 8.0 | 8.6 | 8.3 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 0.035 |

| Single/Multiclass | |||||||

| Single Class | 71.3 | 72.0 | 72.8 | 73.3 | 72.9 | 73.9 | <0.001 |

| Multiclass/multiple pill | 12.0 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 0.221 |

| Multiclass/Combination therapy |

16.7 | 15.9 | 15.2 | 15.0 | 14.5 | 13.5 | <0.001 |

| Initiated with a 90 day fill | 17.3 | 19.3 | 23.4 | 28.5 | 31.7 | 33.7 | <0.001 |

| Year before initiation | |||||||

| Medicaid buy-in | 25.6 | 21.5 | 21.9 | 20.3 | 20.2 | 20.4 | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 10.5 | 10.9 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 11.2 | 10.2 | 0.758 |

| Diabetes | 26.3 | 26.3 | 27.3 | 28.0 | 28.7 | 29.1 | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 20.0 | 18.9 | 19.2 | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.7 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 7.0 | 6.8 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 0.039 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10.1 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 13.2 | 14.0 | 15.7 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 9.5 | 9.3 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 9.0 | 0.596 |

| History of depression | 24.6 | 25.1 | 24.7 | 26.3 | 27.1 | 27.5 | <0.001 |

| Falls | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 0.706 |

| Polypharmacy | 20.5 | 19.8 | 20.3 | 22.2 | 22.3 | 22.8 | <0.001 |

| Medicare part D coverage gap |

19.0 | 20.2 | 20.5 | 20.6 | 19.6 | 19.5 | 0.968 |

|

Six months after initiation |

|||||||

| Medicaid buy-in | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 0.059 |

| Newly diagnosed dementia |

2.4 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 | <0.001 |

| Newly diagnosed diabetes | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.117 |

| Newly diagnosed coronary heart disease |

4.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 0.013 |

| Newly diagnosed stroke | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.008 |

| Newly diagnosed chronic kidney disease |

3.5 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 0.018 |

| Newly diagnosed heart failure |

0.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.935 |

| Newly diagnosed depression |

6.7 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 0.163 |

| Falls | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.688 |

| Polypharmacy | 12.1 | 13.2 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 0.770 |

| Medicare part D coverage gap |

8.7 | 6.5 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

Numbers in table for age are mean (standard deviation) and percent for all other characteristics.

Multiclass=Incident prescription fill for ≥2 medications within 7 days.

Antihypertensive medication discontinuation

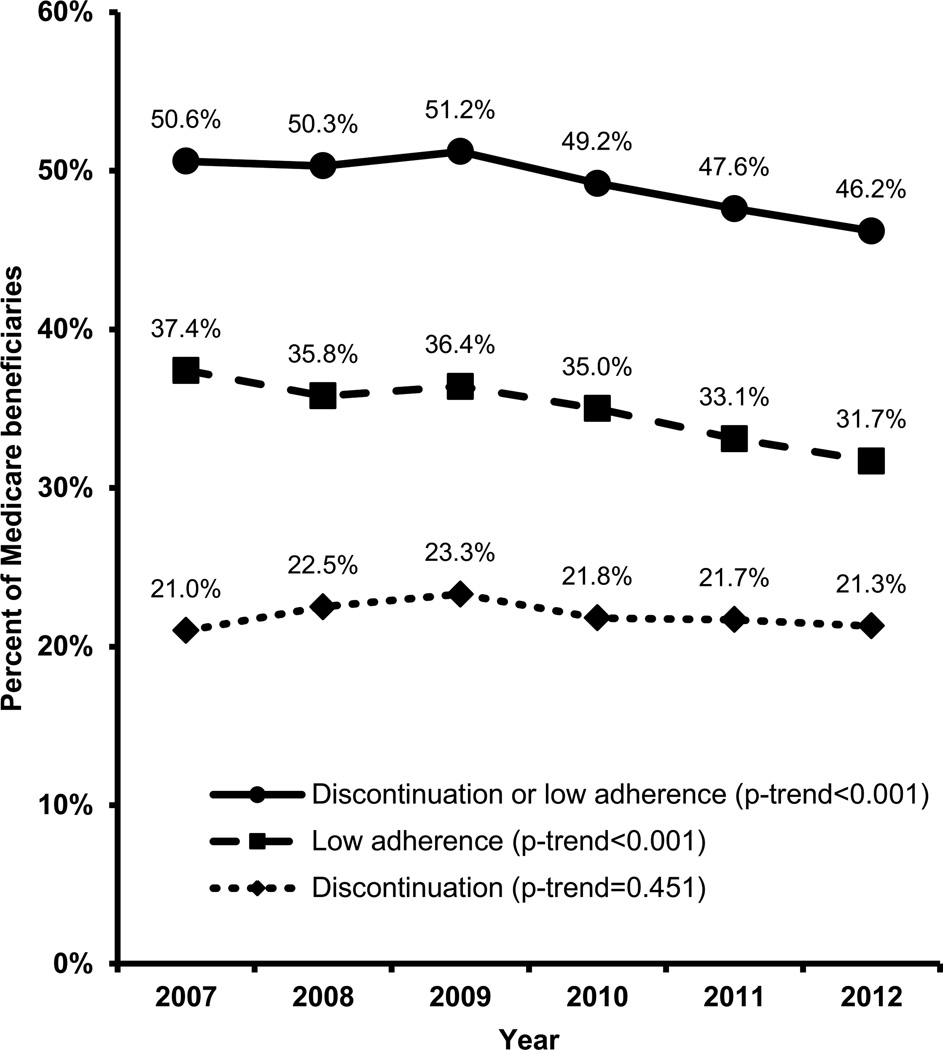

Among beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication in 2007, 21.0% discontinued treatment compared with 21.3% in 2012 (Figure 2; p-trend across calendar years 0.451). The percentage of beneficiaries who discontinued treatment decreased among those 70–74 years old and increased among beneficiaries ≥ 85 years old (Table S2). There were no secular trends in antihypertensive medication discontinuation by sex, race/ethnicity, and with the exception of ARBs, antihypertensive drug class initiated. Among Medicare beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication with an ARB, 21.1% in 2007 discontinued treatment compared with 17.2% in 2012 (p-trend=0.011).

Figure 2.

Percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who discontinued and/or had low adherence to antihypertensive medication within one year of initiation in 2007 through 2012. Discontinuation was defined as having no days of supply for any antihypertensive medication class during the last 90 days of the 365 day follow-up period. Low adherence was defined as an interval-based proportion of days covered <80% during the 365 day follow-up period among beneficiaries who did not discontinue treatment.

After multivariable adjustment, women were less likely to discontinue antihypertensive medication compared with men while blacks, Hispanics, and Asians were more likely to discontinue treatment compared with white beneficiaries (Table 2). Initiation of antihypertensive medication with a CCB, ACE-I, ARB, BB, multiclass regimen, and a 90 day prescription fill, and a history of stroke or dementia in the look-back period were associated with a lower risk of discontinuation. Beneficiaries who had Medicaid buy-in, a serious fall injury, or were on polypharmacy in the year prior to initiating antihypertensive medication had a higher risk of discontinuation. Incident diagnoses of stroke, HF, polypharmacy, and reaching the Medicare Part D coverage gap in the six months after initiation were associated with lower risk of discontinuation.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and multivariable adjusted relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for antihypertensive medication discontinuation among Medicare beneficiaries in 2007–2012.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) |

Multivariable Adjusted 1 RR (95% CI) |

Multivariable Adjusted 2 RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calendar year* | |||

| 2007 | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| 2008 | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 1.09 (1.02–1.16) | 1.08 (1.02–1.15) |

| 2009 | 1.11 (1.04–1.18) | 1.13 (1.06–1.20) | 1.12 (1.05–1.20) |

| 2010 | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) |

| 2011 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) |

| 2012 | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) |

| Age, years | |||

| 65–69 | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| 70–74 | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) |

| 75–79 | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) |

| 80–84 | 1.02 (0.96–1.08) | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) |

| 85+ | 1.00 (0.95–1.07) | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| Female | 0.89 (0.86–0.93) | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) | 0.87 (0.84–0.91) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| Black | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 1.07 (1.01–1.15) | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) |

| Hispanic | 1.32 (1.21–1.44) | 1.17 (1.06–1.28) | 1.16 (1.06–1.27) |

| Asian | 1.25 (1.14–1.38) | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 1.12 (1.02–1.24) |

| Other | 1.13 (1.02–1.26) | 1.11 (1.00–1.24) | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) |

| Antihypertensive drug class initiated |

|||

| Thiazide-type diuretic | 0.94 (0.89–0.98) | 1.16 (1.09–1.23) | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 0.84 (0.80–0.89) | 0.89 (0.84–0.93) | 0.89 (0.84–0.93) |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor |

0.81 (0.78–0.85) | 0.88 (0.84–0.91) | 0.87 (0.83–0.90) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker |

0.83 (0.79–0.88) | 0.85 (0.81–0.91) | 0.86 (0.81–0.91) |

| Loop diuretic | 1.33 (1.27–1.40) | 1.40 (1.32–1.47) | 1.44 (1.36–1.52) |

| Beta blocker | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | 0.90 (0.87–0.95) | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) |

| Other | 1.14 (1.08–1.22) | 1.28 (1.20–1.36) | 1.29 (1.21–1.37) |

| Single/Multiclass | |||

| Single Class | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| Multiclass/multiple pill | 0.62 (0.57–0.66) | 0.62 (0.58–0.67) | 0.66 (0.61–0.71) |

| Multiclass/Combination therapy |

0.80 (0.76–0.85) | 0.84 (0.79–0.89) | 0.84 (0.79–0.88) |

| Initiated with a 90 day fill | 0.71 (0.68–0.75) | 0.73 (0.70–0.77) | 0.72 (0.69–0.76) |

| Year before initiation | |||

| Medicaid buy-in | 1.24 (1.19–1.29) | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) | 1.15 (1.10–1.21) |

| Dementia | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) |

| Diabetes | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | 1.03 (0.99–1.09) |

| Stroke | 0.87 (0.81–0.95) | 0.85 (0.79–0.93) | 0.87 (0.80–0.95) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | 1.02 (0.96–1.08) |

| Heart failure | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | 0.97 (0.90–1.03) | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) |

| History of depression | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) |

| Falls | 1.10 (1.01–1.19) | 1.12 (1.03–1.21) | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) |

| Polypharmacy | 1.19 (1.14–1.24) | 1.13 (1.07–1.18) | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) |

| Medicare part D coverage gap |

1.10 (1.06–1.15) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) |

| Six months after initiation | |||

| Medicaid buy-in | 0.87 (0.76–0.99) | 0.95 (0.83–1.08) | |

| Newly diagnosed dementia | 0.84 (0.74–0.97) | 0.88 (0.77–1.01) | |

| Newly diagnosed diabetes | 0.94 (0.81–1.07) | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) | |

| Newly diagnosed coronary heart disease |

0.91 (0.82–1.00) | 0.94 (0.85–1.04) | |

| Newly diagnosed stroke | 0.82 (0.70–0.96) | 0.83 (0.71–0.98) | |

| Newly diagnosed chronic kidney disease |

0.94 (0.85–1.03) | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | |

| Newly diagnosed heart failure |

0.36 (0.21–0.61) | 0.38 (0.22–0.64) | |

| Newly diagnosed depression | 0.85 (0.78–0.92) | 0.95 (0.87–1.03) | |

| Falls | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | 1.04 (0.90–1.19) | |

| Polypharmacy | 0.66 (0.62–0.71) | 0.73 (0.68–0.79) | |

| Medicare part D coverage gap |

0.71 (0.64–0.78) | 0.76 (0.69–0.84) |

RR=relative risk; CI=confidence interval.

Discontinuation was defined as having no days of supply for any antihypertensive medication class during the last 90 days of the 365 day follow-up period.

Multiclass=Incident prescription fill for ≥2 medications within 7 days.

Multivariable Adjusted 1: includes calendar year, age, race/ethnicity, sex, antihypertensive drug class initiated, and Medicaid buy-in, dementia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, history of depression, falls, polypharmacy, Medicare part D coverage gap from the year prior to antihypertensive medication initiation.

Multivariable Adjusted 2: includes variables in Model 1 and variables from the six months after antihypertensive medication initiation.

To avoid co-linearity, each antihypertensive medication class was evaluated in separate regression models with beneficiaries initiating an antihypertensive medication class being compared to beneficiaries initiating treatment without that class.

P-trend unadjusted =0.451; multivariable adjusted 1 =0.302; multivariable adjusted 2 =0.501

Low adherence to antihypertensive medication

The percentage of Medicare beneficiaries with low adherence to antihypertensive medication in the year after initiation decreased overall from 37.4% in 2007 to 31.7% in 2012 (Figure 2; p-trend <0.001). The percentage with low adherence to antihypertensive medication decreased over time among beneficiaries < 85 years old, men and women, and white and black beneficiaries (Table S3). After multivariable adjustment, low adherence declined between 2007 and 2012 (Table 3). Women were less likely than men to have low adherence while black, Hispanic, Asian, and those of other race/ethnicities were more likely to have low adherence compared to white beneficiaries. Initiation of antihypertensive treatment with a CCB, ACE-I, BB, a multiclass regimen, and a 90 day prescription fill were associated with decreased risk for low adherence. Beneficiaries who had Medicaid buy-in, diabetes, CHD, CKD, and who were on polypharmacy in the year prior to initiation were more likely to have low adherence while those with dementia, a history of stroke, and Medicare coverage gap in the year prior to initiation were less likely to have low adherence. Polypharmacy and reaching the Medicare Part D Coverage Gap in the six months after initiation was associated with a decreased risk of low adherence while having a serious fall in the six months after initiation was associated with a higher risk of low adherence.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and multivariable adjusted relative risk and 95% confidence intervals for low adherence to antihypertensive medication among Medicare beneficiaries in 2007–2012, excluding beneficiaries who discontinued treatment.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) |

Multivariable Adjusted 1 RR (95% CI) |

Multivariable Adjusted 2 RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calendar year* | |||

| 2007 | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| 2008 | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 0.97 (0.92–1.01) |

| 2009 | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) |

| 2010 | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) |

| 2011 | 0.89 (0.84–0.93) | 0.93 (0.88–0.97) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) |

| 2012 | 0.85 (0.80–0.89) | 0.89 (0.84–0.93) | 0.88 (0.83–0.92) |

| Age, years | |||

| 65–69 | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| 70–74 | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) |

| 75–79 | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) |

| 80–84 | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) |

| 85+ | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| Female | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| Black | 1.37 (1.31–1.43) | 1.37 (1.31–1.44) | 1.36 (1.30–1.43) |

| Hispanic | 1.50 (1.41–1.61) | 1.37 (1.28–1.47) | 1.37 (1.28–1.47) |

| Asian | 1.21 (1.11–1.32) | 1.10 (1.01–1.21) | 1.11 (1.02–1.22) |

| Other | 1.21 (1.11–1.32) | 1.18 (1.08–1.29) | 1.18 (1.09–1.29) |

| Antihypertensive drug class initiated |

|||

| Thiazide-type diuretic | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 0.82 (0.80–0.85) | 0.85 (0.82–0.89) | 0.86 (0.82–0.89) |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor |

0.83 (0.79–0.86) | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) | 0.86 (0.84–0.89) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker |

1.13 (1.09–1.17) | 1.10 (1.06–1.15) | 1.11 (1.06–1.15) |

| Loop diuretic | 1.18 (1.12–1.23) | 1.33 (1.26–1.39) | 1.34 (1.28–1.41) |

| Beta blocker | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 0.95 (0.92–0.99) | 0.96 (0.92–0.99) |

| Other | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) |

| Single/Multiclass | |||

| Single Class | 1(ref) | 1(ref) | 1(ref) |

| Multiclass/multiple pill | 0.65 (0.62–0.69) | 0.65 (0.61–0.69) | 0.67 (0.63–0.71) |

| Multiclass/Combination therapy |

1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) |

| Initiated with a 90 day fill | 0.77 (0.74–0.80) | 0.78 (0.76–0.82) | 0.78 (0.75–0.81) |

| Year before initiation | |||

| Medicaid buy-in | 1.21 (1.17–1.25) | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | 1.11 (1.07–1.15) |

| Dementia | 0.76 (0.72–0.81) | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) | 0.76 (0.71–0.80) |

| Diabetes | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 1.08 (1.04–1.13) |

| Stroke | 0.87 (0.81–0.92) | 0.88 (0.82–0.94) | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) |

| Heart failure | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) |

| History of depression | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 1.01 (0.97–1.04) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) |

| Falls | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 1.02 (0.95–1.10) |

| Polypharmacy | 1.14 (1.10–1.18) | 1.14 (1.09–1.18) | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) |

| Medicare part D coverage gap |

0.99 (0.95–1.02) | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | 0.89 (0.85–0.93) |

| Six months after initiation | |||

| Medicaid buy-in | 0.91 (0.82–1.01) | 0.98 (0.88–1.08) | |

| Newly diagnosed dementia | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | |

| Newly diagnosed diabetes | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 1.06 (0.95–1.17) | |

| Newly diagnosed coronary heart disease |

0.99 (0.92–1.07) | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | |

| Newly diagnosed stroke | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 1.11 (1.00–1.23) | |

| Newly diagnosed chronic kidney disease |

1.02 (0.94–1.10) | 1.04 (0.97–1.13) | |

| Newly diagnosed heart failure |

1.10 (0.89–1.35) | 1.11 (0.89–1.38) | |

| Newly diagnosed depression | 0.94 (0.88–1.00) | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | |

| Falls | 1.25 (1.14–1.38) | 1.31 (1.19–1.44) | |

| Polypharmacy | 0.76 (0.72–0.80) | 0.83 (0.78–0.87) | |

| Medicare part D coverage gap |

0.72 (0.67–0.78) | 0.74 (0.69–0.80) |

RR=relative risk; CI=confidence interval.

Low adherence was defined as an interval-based proportion of days covered<80% during the 365 day follow-up period among beneficiaries who did not discontinue treatment.

Multiclass=Incident prescription fill for ≥2 medications within 7 days.

Multivariable Adjusted 1–includes calendar year, age, race/ethnicity, sex, antihypertensive drug class initiated, and Medicaid buy-in, dementia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, history of depression, falls, polypharmacy, Medicare part D coverage gap from the year prior to antihypertensive medication initiation.

Multivariable Adjusted 2–includes variables in Model 1 and variables from the six months after antihypertensive medication initiation.

To avoid co-linearity, each antihypertensive medication class was evaluated in separate regression models with beneficiaries initiating an antihypertensive medication class being compared to beneficiaries initiating treatment without that class.

P-trend unadjusted <0.001; multivariable adjusted 1 <0.001; multivariable adjusted 2 <0.001

Sensitivity analysis

There were no statistically significant changes in the percentage of beneficiaries who discontinued antihypertensive medication between 2007 and 2012 in any of the sensitivity analyses (Table S4). The percentage of beneficiaries with low adherence decreased between 2007 and 2012 in each of the sensitivity analyses (Table S5). The percentage of beneficiaries who discontinued or had low adherence to antihypertensive medication in the year after initiation decreased from 50.6% in 2007 to 46.2% in 2012 (Figure 2; Table S6; p-trend <0.001).

Discussion

In the current study of Medicare beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication, approximately 20% discontinued treatment within one year and this percentage remained constant between 2007 and 2012. In contrast, a decline in low adherence to antihypertensive medication occurred over this time period. However, in 2012, almost 50% of beneficiaries either discontinued antihypertensive medication or had low adherence in the year following treatment initiation.

Previous studies have suggested that treatment discontinuation is an intentional action while low adherence involves both intentional actions and unintentional behaviors.3, 17–19 Patients who discontinue antihypertensive medication report more side effects and cite concerns about medication as high relative to their need for treatment.17–19 These barriers may be difficult to overcome to keep patients on treatment. In contrast, some barriers to achieving high adherence can be overcome.17–19 For example, patient-centered care, including improved patient/provider communication and patient education has been associated with increased medication adherence.4, 20 It has been reported that healthcare has become more patient-centered over the past decade.21, 22 Also, a number of studies have reported interventions aimed at improving adherence prior to and during the time frame of this study, with some being effective.3, 4, 6–11 The translation of these interventions into clinical practice may explain some of the reduction in low adherence observed in the current study.

Black and Hispanic beneficiaries were more likely to discontinue and have low adherence to antihypertensive medication compared with whites, which is consistent with prior studies.23, 24 Cost has been cited as the largest barrier to antihypertensive medication adherence among blacks and Hispanics in the United States.23, 24 In previous studies, reductions in copayments for antihypertensive medication have been associated with an increase in adherence.25, 26 Patient-provider trust has also been reported as a barrier to antihypertensive medication adherence among racial/ethnic minorities in the US.27 Building trust between physicians and patients through improved communication and race concordant physician/patient pairings has been shown to improve antihypertensive medication adherence, and these may be useful approaches to decreasing disparities in adherence.28 Given the association between low adherence to antihypertensive medication and increased CVD risk and an approximately 30% higher risk for CVD mortality among blacks compared with whites, improving medication adherence among black adults should be a priority.1, 3, 4

Initiating antihypertensive medication treatment with an ARB was associated with a lower risk for discontinuation. Risk of discontinuation of ARBs was also lower in an analysis of the Marketscan® database for patients initiating treatment in 2001 through 2003, and can potentially be explained by lower rates of side effects for ARBs compared with other antihypertensive drug classes.29 Initiating treatment with a 90 day prescription fill became more common between 2007 and 2012 and was associated with decreased risk of discontinuation and low adherence. Longer prescription fills may help beneficiaries circumvent patient-system barriers to adherence including limited access to a pharmacy.30, 31

Medicaid buy-in and polypharmacy in the year prior to initiating antihypertensive medication were associated with a higher risk of both discontinuation and low adherence. Although beneficiaries with Medicaid buy-in receive assistance in paying for their healthcare utilization and medications, these patients are still subject to copayments and cost may be a barrier to achieving high adherence.24, 32 Also, recent studies have shown high out-of-pocket expenses associated with polypharmacy, and the need for multiple medications can result in patients choosing to take some medications but not others.33 Interventions that reduce copayments for chronic disease medications, including antihypertensive medication, antidiabetes drugs, and statins, have demonstrated overall improvements in adherence and may be useful in reducing the need for patients to choose between drugs.25, 26 Incident polypharmacy and entering the Medicare Part D coverage gap during follow-up were associated with decreased risk of antihypertensive medication discontinuation. Polypharmacy and entering the Medicare Part D coverage gap during follow-up are likely markers of beneficiaries who are filling their medication.24

A serious fall injury during the look-back period was associated with an increased risk for antihypertensive medication discontinuation and a serious fall injury in the 6 months following initiation was associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence. Side effects of antihypertensive medication including dizziness and syncope could contribute to patients’ worries over fall risk.32 Although antihypertensive medication has been associated with an increased fall risk in previous studies, the risk attributable to antihypertensive treatment is low.34 In the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial, intensive versus standard BP treatment (systolic blood pressure <120 mm Hg vs. systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg) was not associated with an increased risk for serious fall injuries.35, 36 Additionally, the risk for falls can be mitigated by interventions including multiple risk factor assessment, physical therapy, and exercise.37

Beneficiaries with a history of diabetes, CKD, and CHD were more likely to have low antihypertensive medication adherence. These populations may encounter several barriers to maintaining high antihypertensive medication adherence including low income, a high prevalence of depression, and complex medication-taking regimens including polypharmacy.38 Given the high CVD risk among adults with diabetes, CKD and CHD, identifying the barriers preventing antihypertensive medication adherence and developing interventions to improve adherence in patients with these comorbidities are needed. A history of dementia and stroke were associated with a lower risk of both discontinuation and low adherence. Many patients with dementia or a history of stroke have caregivers, which has been associated with better medication adherence.39, 40

The current study has several strengths. Medicare provides high generalizability to older US adults.41 The large sample size allowed us to study trends in medication adherence over time in sub-groups. The longitudinal data in Medicare made it possible to study adults initiating antihypertensive medication, and also allowed us to evaluate incident development of co-morbid conditions and other characteristics during the 182 days following initiation of antihypertensive medication. Despite these strengths, this study should be interpreted in the context of its potential limitations. First, while Medicare data was available through 2013, as a result of requiring 365 days of follow-up to calculate discontinuation and low adherence following initiation of antihypertensive medication, we were only able to present results for beneficiaries who initiated treatment through December 31, 2012. Second, pharmacy fill data only provide an indirect measure of adherence and we cannot be certain the medication that Medicare beneficiaries filled was consumed. Also, it is possible that some beneficiaries purchased antihypertensive medication out-of-pocket or through alternate health plans without submitting claims for reimbursement through Medicare. If this occurred, the percentage of beneficiaries who discontinued treatment or had low adherence would be lower than we report. However, paying for medications without submitting claims is not common among Medicare beneficiaries.42 In addition, exam results are not available in Medicare claims and trends in blood pressure control could not be determined. Also, clinical considerations that lead to the initiation and use of antihypertensive medication are not available in claims data. Finally, we studied older Medicare beneficiaries and the generalizability of our findings to younger adults is unknown.

Future research should include interventions that are focused on populations at high risk for discontinuation and low adherence including racial/ethnic minorities, people with low income-status, and those with polypharmacy. Among racial/ethnic minorities, research should identify characteristics that may explain racial disparities in antihypertensive medication discontinuation and low adherence. Additionally, further investigating the association between incident development of co-morbid conditions and other characteristics with discontinuation and low adherence following initiation is warranted in order to provide information on which patient population may benefit from closer monitoring for low adherence and treatment discontinuation.

Perspectives

While there was no change in the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who discontinued antihypertensive medication in the year following treatment initiation from 2007 to 2012, the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries with low antihypertensive medication adherence declined over the study time period. However, a substantial percentage of Medicare beneficiaries initiating antihypertensive medication in 2012, approximately 50%, discontinued treatment or had low adherence. Data from the current study support the need for continued monitoring of antihypertensive medication adherence and interventions aimed at improving rates of discontinuation and low adherence in patients initiating antihypertensive medication.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is New

This study shows that rates of low adherence to antihypertensive medication have declined from 2007 to 2012 among older US adults. Additionally, approximately 50% of older US adults initiating antihypertensive medication have low adherence or discontinue treatment within one year.

What is Relevant

Low antihypertensive medication adherence is associated with uncontrolled blood pressure and increased risk for cardiovascular disease events. Several interventions have been tested in randomized trials with the goal of improving antihypertensive medication adherence. It is unclear whether these interventions have been translated into clinical practice and resulted in improved adherence rates. We identified sociodemographic and clinical conditions associated with antihypertensive medication discontinuation and low adherence in order to inform future medication adherence interventions.

Summary

This study suggests that efforts to improve antihypertensive medication adherence over the past several decades may have been translated into clinical practice. However, low adherence to antihypertensive medication remains common.

Acknowledgments

None

Sources of Funding

Gabriel S. Tajeu: NIH/NHLBI 5T32 HL00745733 (PI-Suzanne Oparil)

Shia T. Kent: NIH/NHLBI 5T32 HL00745733 (PI-Suzanne Oparil)

Ian Kronish: K23 HL098359; R01-HL123368; R01 HS024262

Marie Krousel-Wood: 5K12HD043451-14; 1 U54 GM104940; UL1TR001417

Daichi Shimbo: NHLBI K24-HL125704

Disclosures

Shia T. Kent received grant support from Amgen, Inc.

Daichi Shimbo is a consultant for Abbott Vascular and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation

Paul Muntner receives grant support from Amgen Inc.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–e322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoon SS, Gu Q, Nwankwo T, Wright JD, Hong Y, Burt V. Trends in blood pressure among adults with hypertension: United states, 2003 to 2012. Hypertension. 2015;65:54–61. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: Its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119:3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnier M. Medication adherence and persistence as the cornerstone of effective antihypertensive therapy. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:1190–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The 1980 report of the joint national committee on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:1280–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill MN, Miller NH, DeGeest S American Society of Hypertension Writing Group. ASH position paper: Adherence and persistence with taking medication to control high blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2010;12:757–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabate E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. 2003:211. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Manias E, Lal L, Salas M, Hughes DA, Ratzki-Leewing A, Grubisic M. Impact of interventions on medication adherence and blood pressure control in patients with essential hypertension: A systematic review by the ispor medication adherence and persistence special interest group. Value Health. 2013;16:863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Bethesda (MD): 2004. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgado MP, Morgado SR, Mendes LC, Pereira LJ, Castelo-Branco M. Pharmacist interventions to enhance blood pressure control and adherence to antihypertensive therapy: Review and meta-analysis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:241–253. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD000011. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raebel MA, Schmittdiel J, Karter AJ, Konieczny JL, Steiner JF. Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med Care. 2013;51:S11–S21. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829b1d2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, Lee JL, Jan SA, Brookhart MA, Solomon DH. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:457–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishisaka DY, Jukes T, Romanelli RJ, Wong KS, Schiro TA. Disparities in adherence to and persistence with antihypertensive regimens: An exploratory analysis from a community-based provider network. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297:177–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kronish IM, Woodward M, Sergie Z, Ogedegbe G, Falzon L, Mann DM. Meta-analysis: Impact of drug class on adherence to antihypertensives. Circulation. 2011;123:1611–1621. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.983874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hugtenburg JG, Timmers L, Elders PJ, Vervloet M, van Dijk L. Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: A challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:675–682. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S29549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R. Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: Application of the necessity-concerns framework. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowry KP, Dudley TK, Oddone EZ, Bosworth HB. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence to antihypertensive medication. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1198–1203. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014 national healthcare quality and disparities report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. Jun, http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr14/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tajeu GS, Kazley AS, Menachemi N. Do hospitals that do the right thing have more satisfied patients? Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40:348–355. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gellad WF, Haas JS, Safran DG. Race/ethnicity and nonadherence to prescription medications among seniors: Results of a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1572–1578. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0385-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes HM, Luo R, Hanlon JT, Elting LS, Suarez-Almazor M, Goodwin JS. Ethnic disparities in adherence to antihypertensive medications of medicare part d beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1298–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chernew ME, Shah MR, Wegh A, Rosenberg SN, Juster IA, Rosen AB, Sokol MC, Yu-Isenberg K, Fendrick AM. Impact of decreasing copayments on medication adherence within a disease management environment. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:103–112. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maciejewski ML, Farley JF, Parker J, Wansink D. Copayment reductions generate greater medication adherence in targeted patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:2002–2008. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyre AD, Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Kawasaki L, DeSalvo KB. Prevalence and predictors of poor antihypertensive medication adherence in an urban health clinic setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoenthaler A, Allegrante JP, Chaplin W, Ogedegbe G. The effect of patient-provider communication on medication adherence in hypertensive black patients: Does race concordance matter? Ann Behav Med. 2012;43:372–382. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9342-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elliott WJ, Plauschinat CA, Skrepnek GH, Gause D. Persistence, adherence, and risk of discontinuation associated with commonly prescribed antihypertensive drug monotherapies. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:72–80. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.01.060094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liberman JN, Girdish C. Recent trends in the dispensing of 90-day-supply prescriptions at retail pharmacies: Implications for improved convenience and access. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2011;4:95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Odegard PS, Capoccia K. Medication taking and diabetes: A systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:1014–1029. doi: 10.1177/0145721707308407. discussion 1030-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Islam T, Morisky DE, Webber LS. Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence in hypertension management: Perspective of the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:753–769. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. Nov, Prescription drug cost-sharing and antihypertensive drug access among state medicaid fee for service plans. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/Medicaid_State_Laws.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters R, Beckett N, McCormack T, Fagard R, Fletcher A, Bulpitt C. Treating hypertension in the very elderly-benefits, risks, and future directions, a focus on the hypertension in the very elderly trial. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1712–1718. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7050. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright JT, Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM, Lamb SE. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muntner P, Judd SE, Krousel-Wood M, McClellan WM, Safford MM. Low medication adherence and hypertension control among adults with ckd: Data from the regards (reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:447–457. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.02.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foebel AD, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA. Caregiver status affects medication adherence among older home care clients with heart failure. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24:718–721. doi: 10.3275/8475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trivedi RB, Bryson CL, Udris E, Au DH. The influence of informal caregivers on adherence in copd patients. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44:66–72. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirel LB, Wheatcroft G, Parker JD, Makuc DM. Health characteristics of medicare traditional fee-for-service and medicare advantage enrollees: 1999–2004 national health and nutrition examination survey linked to 2007 medicare data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yun H, Curtis JR, Saag K, Kilgore M, Muntner P, Smith W, Matthews R, Wright N, Morrisey MA, Delzell E. Generic alendronate use among medicare beneficiaries: Are part d data complete? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:55–63. doi: 10.1002/pds.3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.