Abstract

Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clinically, chronic GVHD is a pleiotropic, multiorgan syndrome involving tissue inflammation and fibrosis that often results in permanent organ dysfunction. Chronic GVHD is fundamentally caused by replacement of the host’s immune system with donor cells, although the heterogeneity of clinical manifestations suggests that patient, donor, and transplant factors modulate the phenotype. The diagnosis of chronic GVHD and determination of treatment response largely rely on clinical examination and patient interview. The 2005 and 2014 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Projects on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic GVHD standardized the terminology around chronic GVHD classification systems to ensure that a common language and procedures are being used in clinical research. This review provides a summary of these recommendations and illustrates how they are being used in clinical research and the potential for their use in clinical care.

Introduction

When the hematopoietic system of a nongenetically identical donor is transplanted into a recipient, the resulting inflammation and immune dysregulation can lead to chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Chronic GVHD is the most common long-term complication after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT),1 and it decreases the success of transplantation by increasing the risk of death and disability.2,3 Chronic GVHD is the leading cause of nonrelapse mortality in transplant survivors otherwise cured of their diseases,4-8 and its adverse effects include physical, functional, and psychosocial deficits, inability to return to work, and poor quality of life (QOL).3,9-13 It is tragic that in the course of trying to cure 1 life-threatening disease, we often cause collateral suffering and death due to a common iatrogenic complication.

Most cases of chronic GVHD are diagnosed within the first year after HCT, but 5% to 10% of affected patients do not develop signs and symptoms until later. Approximately 30% of chronic GVHD is de novo without any preceding acute GVHD.14 At onset, many patients have an inflammatory skin rash, oral sensitivities or dryness, or dry, irritated eyes. Transaminase elevations and eosinophilia are common. These early manifestations are relatively easy to control with standard corticosteroid-based immunosuppression but often recur with the same or new manifestations when immunosuppression is tapered. Other manifestations that are less common but much more difficult to control include skin sclerosis or fasciitis, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, oral ulcers unresponsive to local therapies, severe dry eyes, serositis, and gastrointestinal (GI) involvement.15 These manifestations respond poorly to standard immunosuppressive therapies, cause significant organ dysfunction, and are often persistent or permanent.

Because there are no accepted diagnostic biomarkers, and pathologic samples may be difficult to obtain, most chronic GVHD evaluations are based on clinical examinations and patient interviews. The previous lack of objective criteria and reliance on clinician reporting meant that clinical research was dependent on the unstructured reports of individual clinicians who varied greatly in their experience and attention to chronic GVHD manifestations. In an effort to standardize reporting, the 2005 and 2014 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Projects on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic GVHD (henceforth called the “NIH Consensus Conferences” for simplicity) made recommendations for diagnostic criteria, severity scoring, and response assessments to be used in clinical trials. These recommendations have largely been adopted for therapeutic clinical trials by cooperative groups and industry. However, they are less commonly reported in observational and retrospective studies because the measurement tools have not been routinely implemented in clinical care.

This review will focus on the classification systems of chronic GVHD, which include the diagnostic criteria, assessments of organ involvement, and methods to document improvement or worsening during treatment. Throughout, I will try to provide historical perspective for these concepts in the context of therapeutic studies and clinical care. Finally, I will summarize my perspective on the persistent gaps in research and practice, and review ongoing efforts to address these issues.

Historical perspective

Chronic GVHD was first described in 1978 as a wasting syndrome observed in some long-term survivors of allogeneic HCT.16,17 Affected patients had severe sclerosis with joint contractures, lung involvement, weight loss, dry eyes, and other organ manifestations reminiscent of autoimmune diseases. Initially, patients did not receive any treatment other than supportive care when they first developed symptoms. In 1981, Sullivan et al reported that treatment with corticosteroid-based therapy controlled symptoms and improved survival.18 A series of randomized trials over the next 3 decades tried to improve initial treatment of chronic GVHD. In summary, nothing has proven to be superior to single-agent prednisone for initial treatment of chronic GVHD, and no secondary treatment has proven superior to others once the disease progresses or recurs when steroids are tapered.1,19

Currently, between 10% and 70% of patients develop chronic GVHD depending upon donor and transplant characteristics; multicenter and registry statistics show an aggregate cumulative incidence of 30% to 50%.14,20 Use of bone marrow instead of peripheral blood,21-24 specific acute GVHD prophylaxis regimens (eg, broad or selective T-cell depletion,25-28 posttransplant cyclophosphamide29-31), and donor types (eg, umbilical cord blood20,32-34) appear to decrease the incidence, severity, and treatment refractoriness of chronic GVHD. Although data are limited, chronic GVHD manifestations, severity, and outcomes are not different depending on conditioning regimen intensity. Nonrelapse mortality of patients with chronic GVHD has improved over the decades, likely because of better supportive care.14,35 There are no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved treatments for chronic GVHD, although ongoing trials are testing several agents for this indication.

2005 and 2014 NIH Consensus Conferences

In 2004, the NIH convened experts to identify barriers to progress in chronic GVHD research. The following year, Steven Pavletic and Georgia Vogelsang chaired the 2005 NIH Consensus Conference at which findings and recommendations were presented. Six working groups published their papers in 2005 to 2006, summarizing consensus recommendations for diagnosis and scoring,36 histopathology,37 biomarkers,38 response criteria,39 ancillary and supportive care,40 and clinical trials.41

Between 2005 and 2014, many studies were published using the criteria recommended by the 2005 NIH Consensus Conference. A survey of experts in 2013 confirmed agreement with many of the 2005 recommendations but also identified several areas of controversy based on experience with the criteria in practice. For example, experts thought that active disease and irreversible “fixed” deficits should be distinguished, and organ dysfunction entirely attributed to a nonchronic GVHD etiology should be excluded from severity and response scoring.42 To address these controversies, as well as review progress and update recommendations, a second NIH Chronic GVHD Consensus Conference took place in 2014.43 The 250 participants reaffirmed most of the previous 2005 recommendations, and a new series of 6 papers was published.44-49 The response criteria had the most changes because of empiric data published in the 10 years since the original conference.46

NIH late acute and overlap chronic GVHD

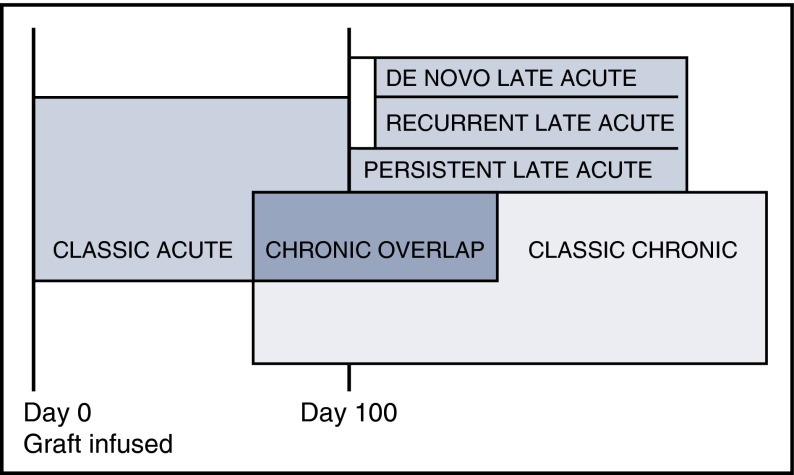

Prior to 2005, any alloimmunity that resulted in clinical manifestations before day 100 was called acute GVHD, whereas any clinical alloimmunity after day 100 was considered chronic GVHD.50 The 2005 NIH Consensus Conference abolished the day 100 dividing line and redefined acute and chronic GVHD as distinct clinical syndromes without a time restriction (Figure 1). Classic acute GVHD occurs before day 100 and is staged according to the percentage of body surface area with rash, total bilirubin elevation, and volume of diarrhea. Late acute GVHD occurs after day 100 and is defined as signs and symptoms of acute GVHD without chronic GVHD. Late acute GVHD is further subdivided into “persistent” if it is a continuation of classic acute GVHD, “recurrent” if classic acute GVHD resolves then recurs after day 100, or “de novo” if initial onset is after day 100 without any prior acute GVHD. Some studies show a higher mortality for patients with late acute GVHD compared with patients with classic chronic GVHD20,51 whereas others do not.52,53 Recognition of the late acute GVHD category decreased the incidence of chronic GVHD because many patients with alloimmunity after day 100 do not meet with diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD based on organ involvement but were previously considered chronic GVHD based solely on time since transplant.54 Although the 2014 NIH Consensus Conference recommended that patients with late acute could be included in chronic GVHD trials with appropriate stratification,45 in practice they are usually excluded.

Figure 1.

Acute, late acute, chronic overlap, and classic chronic GVHD. The box sizes do not reflect prevalence.

The 2005 NIH Consensus Conference also recommended a new category called “overlap chronic GVHD” when concurrent acute and chronic GVHD are present, because of the perception that once patients are diagnosed with chronic GVHD, ongoing acute GVHD portends a worse prognosis. Although controversial because of the different interpretations of how nausea, anorexia, diarrhea, erythematous or maculopapular rashes, and elevated liver function tests should be attributed to acute or chronic GVHD, and the clinical observation that most patients have some elements of acute GVHD at some point in their chronic GVHD experience, “overlap chronic GVHD” was retained in the 2014 update.53 Some studies show worse survival with overlap chronic GVHD compared with classic chronic GVHD,55 but others do not. Overlap chronic GVHD is allowed in chronic GVHD clinical trials, although it is recommended that detailed information about concurrent acute GVHD be captured to allow stratification during the analysis.

NIH diagnostic criteria

The NIH diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD changed little between 2005 and 2014. Per the 2014 NIH criteria, the diagnosis of chronic GVHD requires (a) at least 1 diagnostic manifestation or (b) 1 distinctive manifestation confirmed by biopsy or testing of the same or other involved organ.45 “Diagnostic” manifestations sufficient by themselves to establish the diagnosis of chronic GVHD may be found in the skin, mouth, GI tract, lung, fascia, and genitalia (for example, lichen planus or lichen sclerosis, poikiloderma, sclerosis, or esophageal webs) (Figure 2). There are no diagnostic features of the nails, eyes, liver, or other organs. If the lung is the only site of chronic GVHD without a distinctive manifestation elsewhere, then a lung biopsy showing bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome is required to establish the diagnosis of chronic GVHD for the purpose of clinical trials enrollment. “Distinctive” criteria are clinically suspicious for chronic GVHD but are not sufficient by themselves to establish the diagnosis because other etiologies could account for the signs, so a confirmatory test is required. Examples of distinctive features are papulosquamous lesions, oral ulcers, onycholysis, or dry gritty eyes. Examples of confirmatory tests are tissue biopsies (eg, skin, mouth, lung, liver, GI, genital), organ-specific testing (eg, pulmonary function tests, Schirmer tests), imaging (eg, a barium swallow showing an esophageal ring), or evaluation by a specialist such as an ophthalmologist or gynecologist confirming GVHD. Biopsy evidence showing “likely” GVHD is sufficient; the histopathology does not need to be definitive as long as other potential etiologies are not present. Because the differential diagnosis for liver test abnormalities and GI symptoms in the posttransplant setting is broad, histopathologic confirmation may be especially important as a prior study reported incorrect attribution to GVHD in many cases.56

Figure 2.

Diagnostic skin and mouth manifestations. (A) Lichen planus and poikiloderma. (B) Fasciitis and sclerosis. (C) Sclerosis. (D) Oral lichen planus.

It is important to realize that the NIH diagnostic criteria were devised for clinical trials to ensure that study participants had unequivocal chronic GVHD. Many patients with signs and symptoms encountered in practice will not meet the NIH diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD but nevertheless have active alloimmunity requiring systemic immunosuppression to improve symptoms and prevent ongoing organ damage. Clinical studies that require participants to meet the NIH diagnostic criteria should collect data to confirm eligibility because a multicenter cooperative group study found that up to 10% of enrolled patients actually did not meet NIH diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD (Paul Carpenter, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, oral communication, October 2015).

Until 2016, the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) used the older case report forms that did not reflect NIH recommendations out of concern that trying to collect observational data from medical records according to the new NIH consensus criteria would be impossible given documentation standards. The CIBMTR has now updated their 2016 case report forms to capture chronic GVHD according to NIH recommendations, but it remains to be seen whether data quality will be sufficient for analysis.

NIH severity scoring

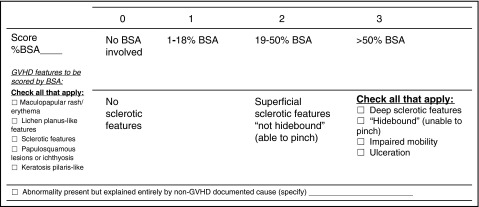

Signs and symptoms of chronic GVHD vary between individuals and in the same individual over time, making determination of GVHD severity challenging. The most frequently involved organs in patients with chronic GVHD are skin, mouth, and liver, with less frequent involvement of eye, lung, GI tract, joint/fascia, and genital tract.20 Organs are scored on a 0 to 3 scale from no involvement/no symptoms to severe functional compromise. Most organs have a single scale to capture severity; however, the skin and lung have multiple components that contribute to maximum severity. For the skin, the highest score from items about body surface area involvement and severity of sclerosis is used to determine global severity (Figure 3). For the lung, pulmonary function test results are used if available, otherwise the lung score is based on symptoms. Higher organ scores for the skin,57,58 lung,59 GI tract,60 and liver61 have been associated with worse survival.

Figure 3.

2014 NIH skin score. BSA, body surface area.

Fixed deficits vs active inflammatory or fibrotic disease may be hard to distinguish clinically, and most are not differentiated in severity scoring. For example, dry eyes from destruction of lacrimal glands and joint contractures from sclerosis are often permanent but are still included when scoring their respective organs. In contrast, residual hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and poikiloderma from prior inflammatory skin involvement are no longer counted as part of body surface area involvement.

Patients with chronic GVHD have many concurrent medical issues that may trigger a score on the chronic GVHD assessment form yet be unrelated to chronic GVHD, for example, skin rashes due to drug toxicity or infection, skin erythema from sun exposure, infectious diarrhea, or poor pulmonary function tests that predated transplantation. All dysfunction should be scored on the chronic GVHD assessment sheet with other etiologies noted as appropriate. New with the 2014 criteria, if an abnormality is entirely due to a nonchronic GVHD cause then the organ is excluded from the calculation of global severity. If chronic GVHD at least partly explains the organ dysfunction, then the score is used in global severity calculation without modification. This compromise was reached because it is impossible to parse out the chronic GVHD component vs other etiologies when there are multiple causes. By noting whether nonchronic GVHD causes contribute to organ dysfunction, investigators can analyze the data depending on the objective of their study. A scientist interested in biomarkers might want to exclude all cases with non-GVHD-contributing causes to obtain a more homogeneous affected population; another scientist might want to include patients with skin rashes from non-GVHD causes as controls to compare with rashes caused by GVHD. One study reported that 78.3% of abnormalities were attributed wholly to chronic GVHD whereas 14.4% were attributable to other causes, especially in the lung, GI tract, and skin; 7.3% were attributed to both chronic GVHD and other causes.62 Exclusion of abnormalities entirely due to other causes decreased global severity by 1 or more categories in 7% of patients.

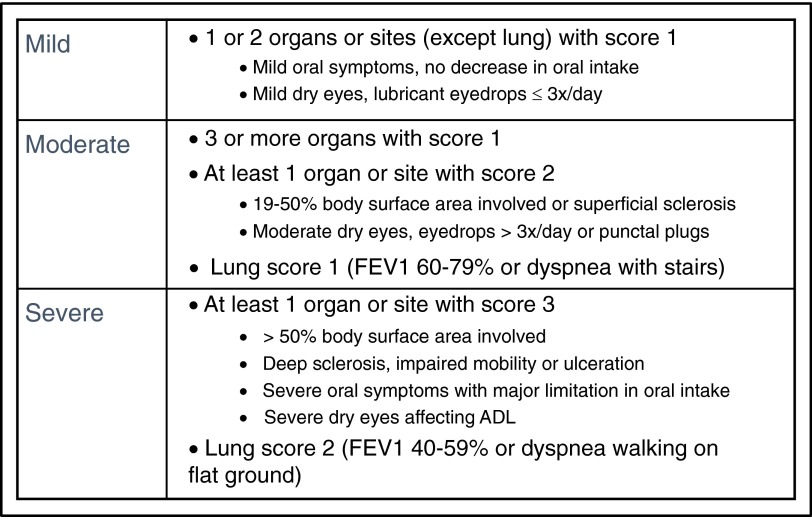

Global severity scoring is divided into mild, moderate, or severe based on the number and severity of involved organs (Figure 4). Mild disease is 2 or fewer organs with no more than score 1 and no lung involvement. For patients with mild disease, treatment with topical or local therapies may be sufficient, although systemic therapy is often given for patients presenting with high-risk features. Moderate disease is 3 or more organs with score 1, any organ with score 2, or lung with score 1, and usually requires systemic immune-suppressive treatment. Severe disease is any organ with a score of 3 or lung with a score of 2, and means that substantial organ damage already exists. In 1 multicenter prospective study, severity at onset was 19% mild, 53% moderate, and 28% severe.20 Studies show that mild disease is associated with a good prognosis whereas severe disease is associated with higher treatment-related mortality and lower survival.63

Figure 4.

Calculation of mild, moderate, and severe global severity, with examples. If the entire abnormality in an organ is noted to be unequivocally explained by a non-GVHD documented cause, that organ is not included for calculation of the global severity. If the abnormality in an organ is attributed to multifactorial causes (GVHD plus other causes) the scored organ will be used for calculation of the global severity regardless of the contributing causes (no downgrading of organ severity score). ADL, activities of daily living; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Different ethnic groups may have unique chronic GVHD natural histories. For example, studies of ethnic Japanese patients show they differ from Western populations with less severe chronic GVHD and a lower death rate.64 Moderate-severe disease and overlap chronic GVHD also have less prognostic significance for the Japanese population, perhaps because of better overall outcomes.65

NIH response criteria

Individual organs

Defining response criteria that are reliable and sensitive to clinically meaningful changes in chronic GVHD activity has proven challenging. Historically, investigators relied on clinical impressions to determine improvement or worsening. The original 2005 criteria for organ response offered more objective categories but were still based on expert opinion. Patients were scored for 8 organs before introduction of a treatment, and then at calendar-driven time points later. The organs considered in response assessment included skin, mouth, liver, upper GI, lower GI, esophagus, lung, and eye. Genital tract and joint/fascia were not included due to lack of validated measures.

The 2014 Consensus recommendations simplified data collection and scoring based on results of studies performed between the 2 conferences.46 The 2014 criteria eliminated the need for precise body surface area reporting, the Schirmer test,66 and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide,67,68 modifications which decreased the burden on patients and clinicians. Two data elements that are easy to assess during the physical examination were added for joint/fascia,69 so now 9 organs contribute to response assessment. The 2014 modification also revised handling of attribution: if organ dysfunction is entirely explained by a nonchronic GVHD cause, that organ is excluded from calculation of the overall response.

One area of ongoing confusion is why the response criteria and the severity scoring criteria for organs are not identical. The rationale for using different tools is that the goals are different. Measures to document severity are broader and designed to be used in clinic by nonchronic GVHD specialists who lack specific training. Categories are simplified to ensure complete capture of reliable information. The global severity score is multidimensional and designed to document cross-sectional assessments. There are ceiling effects where patients scoring in the highest category do not have room to worsen, and step effects where slight changes can result in placement in different categories. In contrast, the response assessment tools are more detailed and capture granular chronic GVHD disease activity. The ability to detect changes along unidimensional or linear scales is emphasized. Nevertheless, the severity scoring and response measures are more closely aligned in the 2014 criteria than the 2005 criteria in that the skin, eyes, lungs, and joints share identical scoring criteria. However, differences remain including unique items for assessing mouth, esophagus, and upper and lower GI tract. Pulmonary and liver function tests are analyzed on a continuous scale for response assessment rather than the categorical scale used for severity scoring.

Some disease manifestations such as sclerosis have been notoriously hard to quantify, and different methods of response assessment may account for some of the widely divergent success rates reported in the literature for agents such as imatinib.70-74 Efforts to identify other quantitative methods of disease assessment based on radiographic images are being developed for the skin75,76 and lung.77,78

One challenge is the reproducibility of the clinician-reported information derived from physical examinations. Studies suggest that some measures are reliable such as oral ulcers79 whereas reproducibility is poor for some measures such as body surface area involved with moveable sclerosis.80 A randomized phase 2 study of extracorporeal photopheresis used trained assessors who were blinded to patient treatment so they could quantify objective measures81 but this level of complexity adds additional barriers to chronic GVHD treatment trials.

Patient-reported outcomes

The Response Criteria Working Group also recommended collection of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and functional measures. The PRO surveys take a median of 10 to 15 minutes to complete80 and include the Lee Symptom Scale,82-84 and either the Short Form-36 (SF-36)85 or the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Bone Marrow Transplant version (FACT-BMT)86 plus the Human Activity Profile (HAP).87 In addition, there is a patient chronic GVHD activity assessment form that captures skin itching, skin and/or joint tightening, mouth sensitivity, genital discomfort, eye symptoms, and global ratings of chronic GVHD severity and improvement.46 The FDA has issued guidance about the qualification process for PROs88 to help sponsors pursuing labeling claims. However, the requirements are very stringent. To date, only 1 instrument for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations has been qualified by the FDA.89 In addition, missing data and analytic limitations pose barriers for PROs meeting regulatory requirements. Despite these challenges, 1 study found that changes in clinician-reported outcomes and PROs predicted survival better than other measures, suggesting that even though interpretation of PRO data requires consideration of response bias and measurement error, PROs offer unique and important clinical information.90

NIH overall response

Based on individual organ measures, responses are classified as complete response (CR; no manifestations of chronic GVHD, including “fixed” defects), partial response (PR; clinically meaningful improvement in 1 or more organs without clinically meaningful progression in any other organ), and disease progression (clinically meaningful worsening in 1 or more organs regardless of improvement in other organs). Cases not meeting the definition of CR, PR, or disease progression are considered stable disease. Note that once the pretreatment and posttreatment organ measures are known, the overall response is calculated and does not rely on clinician-reported interpretations of response. Different clinicians may perform the pretreatment and posttreatment assessments, although confidence is enhanced if the same clinician performs both evaluations to eliminate interrater variation.

Both CR and PR are considered meaningful short-term responses in clinical trials. The FDA has indicated that objective GVHD response is the most appropriate primary end point in phase 2 and possibly phase 3 trials, paired with PROs as secondary end points.47 The very long-term significance of CR/PR is unclear because data are mixed about their association with survival73,90 or eventual successful discontinuation of immunosuppression.91 However, if chronic GVHD is viewed as a truly chronic alloimmune syndrome akin to autoimmune diseases, then it might be unrealistic to expect any current treatments will result in CR and ability to stop immunosuppression without some ongoing symptoms; rather, the goals of treatment should perhaps be preservation of function and QOL with the least toxicity, anticipating the potential need for prolonged or lifelong treatment.

Alternate end points besides chronic GVHD response and PROs have been suggested. For example, because addition of a new systemic chronic GVHD treatment is considered treatment failure in clinical trials,46 some investigators have argued that the best measure of treatment success is not having to change to another treatment, so called “failure-free survival” (FFS).92,93 Although FFS is intuitively attractive and data are easy to capture, concerns about the lack of standardized practice approaches to managing chronic GVHD, including the thresholds for changing treatments, and external influences such as the availability of alternative treatments has prevented FFS from gaining traction as a meaningful end point for FDA consideration.

Some investigators have advocated combining clinician-reported, patient-reported and laboratory testing into a composite disease activity scale, similar to scales developed for autoimmune diseases such as the Crohn Disease Activity Index (CDAI).94 However, the FDA has expressed skepticism about this type of end point for chronic GVHD, citing the complexity of the different measures and concerns about the attribution of separate contributions.

Gaps in research and practice

The 2005 and 2014 NIH Consensus Conferences have standardized criteria for clinical trials and removed a major barrier to industry interest in testing new agents for chronic GVHD. The payoff is clear as clinical trials activity in the chronic GVHD space has increased dramatically, including exciting novel agents targeting specific biologic pathways. I believe the next major frontier is to identify patients who are destined to develop hard-to-treat phenotypes, for example, sclerosis/fasciitis, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, unresponsive oral ulcers, severe dry eyes, serositis, and GI involvement, and to intervene early and effectively.

Most practitioners view using the NIH chronic GVHD recommendations in their entirety as too burdensome for use in routine clinical practice.95 Although some aspects such as the response criteria are primarily designed for research use, other classification systems such as severity scoring offer a straightforward systematic approach to assessing organ dysfunction. The PRO instruments measure patient symptoms and QOL using a concise battery. Use of these tools in the clinic might help ensure consistent evaluation of all potentially involved organs, contributing to optimal clinical care, even for patients not participating in clinical trials. Careful screening over time might detect evolving chronic GVHD earlier so that treatment can be started before permanent organ dysfunction develops. These are hypotheses to be tested.

It can be very challenging to conduct clinical trials in chronic GVHD. The population is small, scattered, and heterogeneous. Their clinical manifestations are a mixture of reversible and fixed deficits. Patients receive a variety of potent immunosuppressive agents over the years, and often have a background of chronic illness that leads to frequent infections and disability. However, the unmet need for effective therapies is very great, and trying to enroll patients into clinical trials if possible will help ensure promising approaches can be evaluated expeditiously.

Summary

Chronic GVHD remains a formidable barrier to successful allogeneic transplantation. Efforts to prevent or ameliorate its clinical significance have been more successful in the last 5 years, primarily though alterations in graft sources and acute GVHD prophylaxis. Lingering concerns about whether the graft-versus-malignancy effect is compromised if GVHD is prevented await more randomized trials. Targeted immunotherapy that does not risk chronic GVHD is another potential solution to the chronic GVHD problem for some patients. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells or other narrow spectrum cellular populations and other targeted immunologic approaches will have lower or negligible risks of alloimmune side effects. Approaches that separate GVHD from the immunologic benefits of allogeneic cells are likely where the ultimate solution to chronic GVHD will come from: preventing it in the first place. There is tangible progress in this direction.

The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in the interest and attention given to chronic GVHD. Among HCT practitioners, there seems to be a greater reluctance to accept chronic GVHD as an inevitable long-term complication of allogeneic transplantation. Many novel agents are being tested, with clinical trials built on the NIH Consensus recommendations. Active collaborations between clinical and laboratory scientists are identifying promising biomarkers. I am optimistic that between better prevention and better treatment, future generations of transplant survivors will suffer less from the devastation of chronic GVHD.

Acknowledgments

The author gives special thanks to Paul Martin, Mary Flowers, Yoshihiro Inamoto, Joseph Pidala, and 3 anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

This work was supported by grants CA163438 and CA118953 from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute. The Chronic GVHD Consortium (U54 CA163438) is part of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). RDCRN is an initiative of the Office of Rare Disease Research (ORDR), NCATS, funded through collaboration between NCATS and the National Cancer Institute.

Authorship

Contribution: S.J.L. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephanie J. Lee, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave N, D5-290, Seattle, WA 98109; e-mail: sjlee@fredhutch.org.

References

- 1.Lee SJ, Flowers ME. Recognizing and managing chronic graft-versus-host disease. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008;2008:134-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraser CJ, Bhatia S, Ness K, et al. Impact of chronic graft-versus-host disease on the health status of hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2006;108(8):2867-2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pidala J, Kurland B, Chai X, et al. Patient-reported quality of life is associated with severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease as measured by NIH criteria: report on baseline data from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2011;117(17):4651-4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatia S, Francisco L, Carter A, et al. Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2007;110(10):3784-3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Socié G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, et al. ; Late Effects Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(1):14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman JM, Majhail NS, Klein JP, et al. Relapse and late mortality in 5-year survivors of myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia in first chronic phase. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1888-1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin PJ, Counts GW Jr, Appelbaum FR, et al. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(6):1011-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(16):2230-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pidala J, Kurland BF, Chai X, et al. Sensitivity of changes in chronic graft-versus-host disease activity to changes in patient-reported quality of life: results from the Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Consortium. Haematologica. 2011;96(10):1528-1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker KS, Gurney JG, Ness KK, et al. Late effects in survivors of chronic myeloid leukemia treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation: results from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2004;104(6):1898-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khera N, Storer B, Flowers ME, et al. Nonmalignant late effects and compromised functional status in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(1):71-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun CL, Francisco L, Kawashima T, et al. Prevalence and predictors of chronic health conditions after hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2010;116(17):3129-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA. 2004;291(19):2335-2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arai S, Arora M, Wang T, et al. Increasing incidence of chronic graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic transplantation: a report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(2):266-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flowers ME, Martin PJ. How we treat chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2015;125(4):606-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graze PR, Gale RP. Chronic graft versus host disease: a syndrome of disordered immunity. Am J Med. 1979;66(4):611-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shulman HM, Sale GE, Lerner KG, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus-host disease in man. Am J Pathol. 1978;91(3):545-570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan KM, Shulman HM, Storb R, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease in 52 patients: adverse natural course and successful treatment with combination immunosuppression. Blood. 1981;57(2):267-276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin PJ, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, Lee SJ, Flowers ME. Treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease: Past, present and future. Korean J Hematol. 2011;46(3):153-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arora M, Cutler CS, Jagasia MH, et al. Late acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(3):449-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. ; Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1487-1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedrichs B, Tichelli A, Bacigalupo A, et al. Long-term outcome and late effects in patients transplanted with mobilised blood or bone marrow: a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(4):331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flowers ME, Parker PM, Johnston LJ, et al. Comparison of chronic graft-versus-host disease after transplantation of peripheral blood stem cells versus bone marrow in allogeneic recipients: long-term follow-up of a randomized trial. Blood. 2002;100(2):415-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohty M, Kuentz M, Michallet M, et al. ; Société Française de Greffe de Moelle et de Thérapie Cellulaire (SFGM-TC). Chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic blood stem cell transplantation: long-term results of a randomized study. Blood. 2002;100(9):3128-3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soiffer RJ, Lerademacher J, Ho V, et al. Impact of immune modulation with anti-T-cell antibodies on the outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2011;117(25):6963-6970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleakley M, Heimfeld S, Loeb KR, et al. Outcomes of acute leukemia patients transplanted with naive T cell-depleted stem cell grafts. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(7):2677-2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kröger N, Solano C, Wolschke C, et al. Antilymphocyte globulin for prevention of chronic graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker I, Panzarella T, Couban S, et al. ; Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group. Pretreatment with anti-thymocyte globulin versus no anti-thymocyte globulin in patients with haematological malignancies undergoing haemopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):164-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luznik L, O’Donnell PV, Symons HJ, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(6):641-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luznik L, Bolaños-Meade J, Zahurak M, et al. High-dose cyclophosphamide as single-agent, short-course prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2010;115(16):3224-3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mielcarek M, Furlong T, O’Donnell PV, et al. Posttransplantation cyclophosphamide for prevention of graft-versus-host disease after HLA-matched mobilized blood cell transplantation. Blood. 2016;127(11):1502-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunstein CG, Fuchs EJ, Carter SL, et al. ; Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood. 2011;118(2):282-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eapen M, Rocha V, Sanz G, et al. ; Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research; Acute Leukemia Working Party Eurocord (the European Group for Blood Marrow Transplantation); National Cord Blood Program of the New York Blood Center. Effect of graft source on unrelated donor haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation in adults with acute leukaemia: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(7):653-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arora M, Nagaraj S, Wagner JE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) following unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT): higher response rate in recipients of unrelated donor (URD) umbilical cord blood (UCB). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(10):1145-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SJ. Have we made progress in the management of chronic graft-vs-host disease? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2010;23(4):529-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(12):945-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shulman HM, Kleiner D, Lee SJ, et al. Histopathologic diagnosis of chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: II. Pathology Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(1):31-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schultz KR, Miklos DB, Fowler D, et al. Toward biomarkers for chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: III. Biomarker Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(2):126-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, et al. ; Response Criteria Working Group. Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(3):252-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic Graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(4):375-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin PJ, Weisdorf D, Przepiorka D, et al. ; Design of Clinical Trials Working Group. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: VI. Design of Clinical Trials Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(5):491-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inamoto Y, Jagasia M, Wood WA, et al. ; Chronic GVHD Consortium. Investigator feedback about the 2005 NIH diagnostic and scoring criteria for chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(4):532-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavletic SZ, Vogelsang GB, Lee SJ. 2014 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: preface to the series. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(3):387-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carpenter PA, Kitko CL, Elad S, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: V. The 2014 Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(7):1167-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(3):389-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Lee SJ, Wolff D, Kitko C, et al. Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: IV. The 2014 Response Criteria Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(6):984-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin PJ, Lee SJ, Przepiorka D, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: VI. The 2014 Clinical Trial Design Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(8):1343-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paczesny S, Hakim FT, Pidala J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: III. The 2014 Biomarker Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(5):780-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shulman HM, Cardona DM, Greenson JK, et al. NIH Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease: II. The 2014 Pathology Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(4):589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69(2):204-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arora M, Nagaraj S, Witte J, et al. New classification of chronic GVHD: added clarity from the consensus diagnoses. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43(2):149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cho BS, Min CK, Eom KS, et al. Feasibility of NIH consensus criteria for chronic graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia. 2009;23(1):78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuzmina Z, Eder S, Böhm A, et al. Significantly worse survival of patients with NIH-defined chronic graft-versus-host disease and thrombocytopenia or progressive onset type: results of a prospective study. Leukemia. 2012;26(4):746-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vigorito AC, Campregher PV, Storer BE, et al. ; National Institutes of Health. Evaluation of NIH consensus criteria for classification of late acute and chronic GVHD. Blood. 2009;114(3):702-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pidala J, Vogelsang G, Martin P, et al. Overlap subtype of chronic graft-versus-host disease is associated with an adverse prognosis, functional impairment, and inferior patient-reported outcomes: a Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Consortium study. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):451-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobsohn DA, Montross S, Anders V, Vogelsang GB. Clinical importance of confirming or excluding the diagnosis of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28(11):1047-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobsohn DA, Kurland BF, Pidala J, et al. Correlation between NIH composite skin score, patient-reported skin score, and outcome: results from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2012;120(13):2545-2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Curtis LM, Grkovic L, Mitchell SA, et al. NIH response criteria measures are associated with important parameters of disease severity in patients with chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(12):1513-1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baird K, Steinberg SM, Grkovic L, et al. National Institutes of Health chronic graft-versus-host disease staging in severely affected patients: organ and global scoring correlate with established indicators of disease severity and prognosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(4):632-639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pidala J, Kim J, Anasetti C, et al. The global severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease, determined by National Institutes of Health consensus criteria, is associated with overall survival and non-relapse mortality. Haematologica. 2011;96(11):1678-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Inamoto Y, Martin PJ, Storer BE, et al. ; Chronic GVHD Consortium. Association of severity of organ involvement with mortality and recurrent malignancy in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica. 2014;99(10):1618-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aki SZ, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, et al. Confounding factors affecting the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease Organ-Specific Score and global severity. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(10):1350-1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arai S, Jagasia M, Storer B, et al. Global and organ-specific chronic graft-versus-host disease severity according to the 2005 NIH Consensus Criteria. Blood. 2011;118(15):4242-4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Atsuta Y, Suzuki R, Yamamoto K, et al. Risk and prognostic factors for Japanese patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37(3):289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aisa Y, Mori T, Kato J, et al. Validation of NIH consensus criteria for diagnosis and severity-grading of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Int J Hematol. 2013;97(2):263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Inamoto Y, Chai X, Kurland BF, et al. ; Chronic GVHD Consortium. Validation of measurement scales in ocular graft-versus-host disease. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(3):487-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bergeron A, Chevret S, Chagnon K, et al. Budesonide/formoterol for bronchiolitis obliterans after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(11):1242-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams KM, Cheng GS, Pusic I, et al. Fluticasone, azithromycin, and montelukast treatment for new-onset bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(4):710-716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Inamoto Y, Pidala J, Chai X, et al. ; Chronic GVHD Consortium. Assessment of joint and fascia manifestations in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(4):1044-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arai S, Pidala J, Pusic I, et al. A randomized phase II crossover study of imatinib or rituximab for cutaneous sclerosis after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(2):319-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Masson A, Bouaziz JD, Peffault de Latour R, et al. Limited efficacy and tolerance of imatinib mesylate in steroid-refractory sclerodermatous chronic GVHD. Blood. 2012;120(25):5089-5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olivieri A, Locatelli F, Zecca M, et al. Imatinib for refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease with fibrotic features. Blood. 2009;114(3):709-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olivieri A, Cimminiello M, Corradini P, et al. Long-term outcome and prospective validation of NIH response criteria in 39 patients receiving imatinib for steroid-refractory chronic GVHD. Blood. 2013;122(25):4111-4118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baird K, Comis LE, Joe GO, et al. Imatinib mesylate for the treatment of steroid-refractory sclerotic-type cutaneous chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(6):1083-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clark J, Yao L, Pavletic SZ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in sclerotic-type chronic graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(8):918-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gottlöber P, Leiter U, Friedrich W, et al. Chronic cutaneous sclerodermoid graft-versus-host disease: evaluation by 20-MHz sonography. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17(4):402-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Galbán CJ, Boes JL, Bule M, et al. Parametric response mapping as an indicator of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(10):1592-1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Galbán CJ, Han MK, Boes JL, et al. Computed tomography-based biomarker provides unique signature for diagnosis of COPD phenotypes and disease progression. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1711-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Treister NS, Stevenson K, Kim H, Woo SB, Soiffer R, Cutler C. Oral chronic graft-versus-host disease scoring using the NIH consensus criteria. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(1):108-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mitchell SA, Jacobsohn D, Thormann Powers KE, et al. A multicenter pilot evaluation of the National Institutes of Health chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) therapeutic response measures: feasibility, interrater reliability, and minimum detectable change. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(11):1619-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Flowers ME, Apperley JF, van Besien K, et al. A multicenter prospective phase 2 randomized study of extracorporeal photopheresis for treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;112(7):2667-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee S, Cook EF, Soiffer R, Antin JH. Development and validation of a scale to measure symptoms of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8(8):444-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Merkel EC, Mitchell SA, Lee SJ. Content validity of the Lee Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Symptom Scale as assessed by cognitive interviews. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(4):752-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vasconcellos de Souza C, Vigorito AC, Miranda EC, et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of the Lee Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Symptom Scale in a Brazilian population. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(7):1313-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 86.McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Cella DF, et al. Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) scale. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19(4):357-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herzberg PY, Heussner P, Mumm FH, et al. Validation of the human activity profile questionnaire in patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(12):1707-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Prodcut Development to Support Labeling Claims. December 2009. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- 89.Leidy NK, Murray LT, Jones P, Sethi S. Performance of the EXAcerbations of chronic pulmonary disease tool patient-reported outcome measure in three clinical trials of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(3):316-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Palmer J, Chai X, Pidala J, et al. Predictors of survival, nonrelapse mortality, and failure-free survival in patients treated for chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2016;127(1):160-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Martin PJ, Storer BE, Carpenter PA, et al. Comparison of short-term response and long-term outcomes after initial systemic treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(1):124-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Inamoto Y, Storer BE, Lee SJ, et al. Failure-free survival after second-line systemic treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2013;121(12):2340-2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Inamoto Y, Flowers ME, Sandmaier BM, et al. Failure-free survival after initial systemic treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2014;124(8):1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F Jr. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70(3):439-444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Duarte RF, Greinix H, Rabin B, et al. Uptake and use of recommendations for the diagnosis, severity scoring and management of chronic GVHD: an international survey of the EBMT-NCI Chronic GVHD Task Force. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(1):49-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]