SUMMARY

Beneficial microorganisms hold promise for the treatment of numerous gastrointestinal diseases. The transfer of whole microbiota via fecal transplantation has already been shown to ameliorate the severity of diseases such as Clostridium difficile infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and others. However, the exact mechanisms of fecal microbiota transplant efficacy and the particular strains conferring this benefit are still unclear. Rationally designed combinations of microbial preparations may enable more efficient and effective treatment approaches tailored to particular diseases. Here we use an infectious disease, C. difficile infection, and an inflammatory disorder, the inflammatory bowel disease ulcerative colitis, as examples to facilitate the discussion of how microbial therapy might be rationally designed for specific gastrointestinal diseases. Fecal microbiota transplantation has already shown some efficacy in the treatment of both these disorders; detailed comparisons of studies evaluating commensal and probiotic organisms in the context of these disparate gastrointestinal diseases may shed light on potential protective mechanisms and elucidate how future microbial therapies can be tailored to particular diseases.

KEYWORDS: Clostridium difficile, fecal microbiota transplantation, microbiota, probiotics, ulcerative colitis

INTRODUCTION

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is an effective and promising therapy for a number of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases, including Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The simultaneous administration of a community of microorganisms in FMT is thought to exert therapeutic effects by restoring functions to the diseased intestine normally conferred by the native microbiota. The particular beneficial strains in FMT are currently incompletely defined, but an improved understanding of the therapeutic benefits conferred by individual microbial strains could enable tailored applications of microbial therapy that circumvent the logistical and ethical issues currently surrounding FMT.

Techniques of FMT administration vary, with fecal preparations being given via oral capsules, nasogastric tubes, nasoduodenal tubes, colonoscopy, or enema (1, 2). Both related and unrelated donors have been used. Donor screening in either case is necessary to reduce the risk of the spread of infectious diseases or other health conditions. Studies originally focused on the use of fresh feces, but frozen fecal preparations have also been shown to be effective (3), and this finding has facilitated the setup of stool banks as a source of preparations (4).

A recent review of case series studies found no serious adverse events attributable to FMT (5), but this procedure is not entirely without risks. There have been two reported cases of patients contracting norovirus following FMT, although transmission was not linked to the donor in these cases (6). There is also concern that FMT in immunocompromised patients could lead to the acquisition of opportunistic infections, but the available data suggest that this is not a common problem for this patient population (7, 8). However, there is some evidence that FMT can lead to the development of noninfectious diseases. FMT for CDI has been linked to relapses in IBD (7, 9) and to the development of peripheral neuropathy, Sjögren's disease, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and rheumatoid arthritis (10). There has also been a reported case of the development of obesity following FMT from an overweight donor (11), but further study is needed to understand the impacts of FMT beyond the GI tract. Furthermore, while donor screening is necessary to reduce the risk of the spread of disease, recruitment and screening of donors are difficult processes with low rates of success (12). FMT is currently designated a biological agent by the FDA, and physicians must submit an investigational new drug application to administer FMT for any indication other than recurrent CDI (13). Uncertainty about the potential long-term effects of FMT and how to appropriately regulate this treatment has limited its use (14). In contrast, development of treatments containing only the effective components of FMT by using combinations of specific microbial strains would alleviate many of these drawbacks that result largely from the undefined nature of fecal preparations.

The focus of this review is to highlight the mechanisms of action by which specific strains of microorganisms known as probiotics exert beneficial effects on the intestinal environment. This information could be used to refine FMT into rationally designed combination microbial therapies that will provide specific benefits of FMT without the potential risks associated with unknown components. Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that confer health benefits when consumed, are usually administered as individual strains or small cocktails of strains and have been shown to reduce the severity of several infectious and inflammatory diseases of the GI tract (15–18). There are several suggested mechanisms by which these diverse microorganisms may confer protection (19–21), including effects on the composition of the resident microbiota, the GI epithelial barrier, and host immune responses. However, in the context of particular diseases, certain functions may confer a greater degree of benefit. Infectious diseases, for example, may require reinforcement of the GI barrier, maintenance or restoration of a normal microbiota, and perhaps direct antipathogen effects. In contrast, diseases with an autoimmune component may be mitigated by probiotic strains that decrease inflammatory responses of the mucosal immune system. Given that the potency of each of these potential mechanisms differs on a strain-specific level, informed selection of probiotic strains to be administered therapeutically in place of FMT is essential.

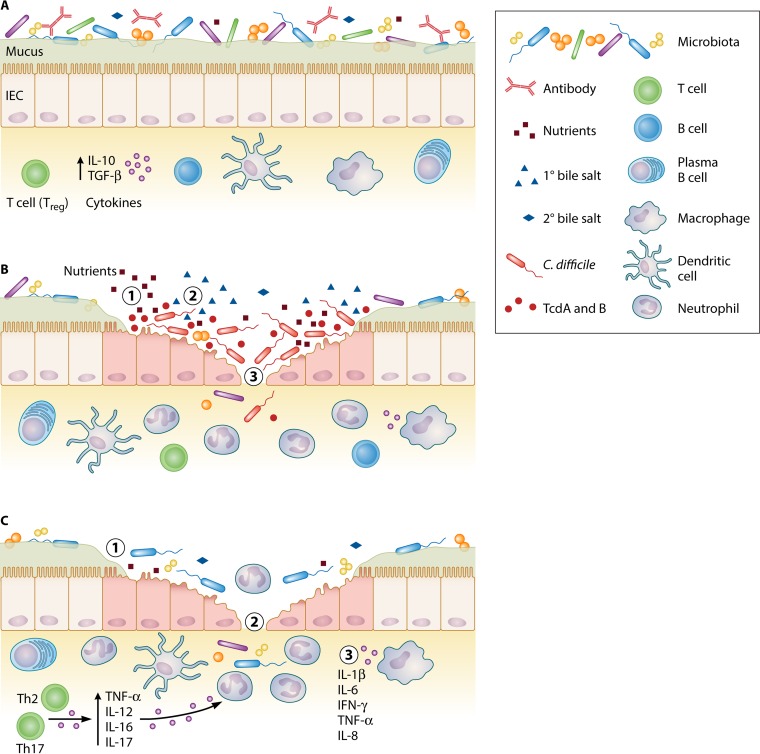

In this review, we use CDI and the inflammatory bowel disease ulcerative colitis (UC) as illustrative cases to explore how microbial therapy might be tailored to either infectious or autoimmune diseases. Both CDI and UC are serious GI diseases that are increasing in prevalence (22, 23). Numerous trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of FMT for CDI, especially for recurrent infections, and recent smaller-scale trials have suggested that UC may also be treated with microbial therapy (22–24). In the case of CDI, pseudomembranous colitis arises from colonization with pathogenic C. difficile and direct toxin-mediated damage of the host GI epithelium (Fig. 1A and B). In contrast, UC develops when genetically susceptible individuals exhibit a breakdown of the GI barrier due to aberrant inflammatory immune responses to microbial antigens (22) (Fig. 1A and C). Comparison of these two diseases with disparate pathogenic mechanisms allows consideration of how particular probiotic strains may be more appropriate in certain disease contexts. We may thus gain insight into which particular organisms could best be applied to the treatment of these and other infectious and inflammatory GI diseases.

FIG 1.

The gastrointestinal mucosa in health, CDI, and UC. (A) The healthy mucosa is characterized by a diverse microbiota that confers colonization resistance and proper immunomodulation; few freely available nutrients; low levels of primary bile salts relative to secondary bile salts; secretory antibody capable of sequestering commensals, pathogens, and other antigens; an intact barrier with healthy epithelial cells and thick layers of mucus containing antimicrobial peptides; few immune cells; and a cytokine milieu dominated by anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β. (B) Disruption of the microbiota results in increased nutrients permissive for C. difficile growth (1) and high concentrations of primary bile salts relative to secondary bile salts (2). These changes promote C. difficile spore germination and growth to high concentrations within the intestine. C. difficile toxins damage epithelial cytoskeletal components, leading to cell death and ulcerations (3). Probiotics may promote colonization resistance through multiple mechanisms, including competition for nutrients and the generation of secondary bile salts that prevent C. difficile germination. Probiotics may also directly inhibit the growth of C. difficile by producing bacteriocins or other inhibitory compounds. Some probiotics produce antitoxin proteases and may stimulate antibody production to sequester C. difficile and toxin. Reinforcing epithelial barriers and modulating inflammation may also promote healing and limit injurious host responses to infection. (C) Ulcerative colitis is characterized by an altered microbiota of decreased diversity (1), damage to the gastrointestinal epithelium (2), as well as aberrant, overly inflammatory host immune responses (3). By helping to maintain a normal microbiota and reinforce the barrier function of the epithelium, probiotics may limit exposure to inflammatory signals. Modulation of the mucosal immune system, including the cytokine milieu, neutrophil infiltration and function, and T cell differentiation, may also help redress aberrant responses to luminal antigens and prevent host-mediated damage to the mucosa. Abbreviations: IEC, intestinal epithelial cell; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; TcdA and TcdB, C. difficile toxins A and B, respectively; TGF, transforming growth factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

To permit discussion of potential microbial therapeutics for infectious diseases as exemplified by CDI and for inflammatory diseases as exemplified by UC, this review is divided into two major sections. We begin each section with an overview of disease pathophysiology followed by a discussion of applicable therapeutic traits identified for particular probiotic and commensal organisms. Emphasis is placed on probiotic strains for which clinical trials have been conducted for the diseases of interest, although additional commensal strains shown to have potential benefits in experimental systems are also considered. By identifying specific organisms with particular mechanisms of action, we can inform studies and trials of rationally combined microbial therapeutics tailored to individual infectious or inflammatory GI diseases.

C. DIFFICILE INFECTION

CDI is an increasing health problem, leading to nearly 500,000 diagnoses and approximately 30,000 deaths annually in the United States alone (25). C. difficile is an obligate anaerobe but can survive for months in the external environment as a dormant spore (26, 27). Spores are highly resistant to many environmental stresses, including ethanol-based disinfectants (28). In susceptible hosts, ingested spores germinate in response to bile salts and amino acids found in the intestine (29). Some individuals develop asymptomatic colonization with C. difficile, while others develop pathogenic CDI. Symptoms of CDI range from mild diarrhea to severe pseudomembranous colitis and death (30). Both asymptomatic and diseased individuals shed infectious spores in their feces that can then spread and infect new hosts (31).

CDI is a toxin-mediated disease, and it has been suggested that patients asymptomatically colonized by C. difficile may have more robust neutralizing immune responses against C. difficile toxins than patients who develop symptoms (32). Most C. difficile strains encode two toxins, TcdA and TcdB, but strains that produce only TcdB or no toxins have also been isolated; only strains without toxins are considered to be avirulent (33–36). TcdA and TcdB bind to any of a number of host cell receptors (37–40) and, once inside host cells, act as monoglucosyltransferases to inactivate Rho family GTPases (41, 42). This inactivation leads to rounding and death of GI epithelial cells, disrupting the epithelial barrier (33, 43, 44). Some strains of C. difficile also encode a binary toxin, C. difficile transferase (CDT) (45), which ADP-ribosylates actin and leads to actin depolymerization and rearrangement of microtubules (45, 46).

In addition to effects on cell death and proliferation, C. difficile toxins perturb the intestinal epithelial barrier by affecting cytoskeletal components and junctional complexes (47). Both TcdA and TcdB mediate the dissociation of the proteins zonula occludins 1 (ZO-1) and ZO-2 in epithelial tight junctions, leading to the separation of F-actin (48) and modulating the integrity of the epithelial barrier (49). The influx of luminal compounds across the intestinal barrier exposes immune cells to bacterial components as well as numerous inflammatory damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from necrotic epithelial cells. TcdA also disrupts epithelial cell polarization, thus affecting the distribution of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the nature and magnitude of immune responses to DAMPs (49). Maintaining the integrity of the junctional complexes between epithelial cells and reinforcing the integrity of the epithelial barrier may thus help to limit damage induced by C. difficile toxins and host inflammatory responses (Fig. 1B).

Risk Factors for Developing CDI

A healthy and intact gut microbiota decreases susceptibility to CDI, a phenomenon known as colonization resistance (50). Indeed, recent studies of CDI in humans have found that decreased microbial diversity is associated with severe and recurrent CDI (51) and have also identified patterns of microbiota change associated with recovery from CDI (52). Antibiotic exposure is the primary risk factor for the development of symptomatic CDI because this treatment perturbs the gut microbiota and reduces colonization resistance (50). Broad-spectrum antibiotics are of the greatest concern for the development of CDI; clindamycin, cephalosporins, aminopenicillins, and fluoroquinolones are all particularly associated with an increased risk of CDI (53–55). Antibiotic treatment depletes members of the two dominant bacterial phyla in the gut, the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes (56, 57). Antibiotics also lead to increases in the numbers of Proteobacteria, which are associated with susceptibility to CDI in humans (56–59). Studies in both humans and animals have indicated that changes in the microbiota brought on by antibiotic treatment can be long lasting, although this depends on the antibiotic used (56, 57, 60, 61). These changes in the gut microbiota facilitate the development of CDI following antibiotic therapy.

In addition to antibiotic use, other factors that influence susceptibility to CDI include age, exposure to health care environments, the use of proton pump inhibitors for conditions such as peptic ulcers, and the production of antitoxin antibodies. Asymptomatic colonization with C. difficile is common in infants; in fact, it is estimated that up to 21 to 48% of infants are asymptomatically colonized with C. difficile (62). Although it is not known why colonized infants generally do not develop disease, it has been suggested that they could be protected by a lack of functional toxin receptors or by antibodies in breast milk (63). Asymptomatic colonization can also occur in adults (62), but old age is a risk factor for the development of symptomatic CDI (64–66). The elderly are thought to be more susceptible because of changes in their gut microbiomes, immunosenescence, increased exposure to health care environments, antibiotic use, and other comorbidities (64, 67). Hospitalization is a major risk factor for both the asymptomatic carriage of C. difficile and the acquisition of pathogenic CDI (26). Proton pump inhibitors are thought to increase the risk of CDI by altering the composition of the gut microbiota (68).

Natural anti-C. difficile TcdA and TcdB antibodies in the general population have been proposed to be protective factors against disease development (69, 70). Toxin-reactive IgG and IgA can be detected in the intestine and serum and have the potential to block toxin binding to epithelial receptors and promote toxin clearance from the intestine (71). The presence of antibodies that are reactive to C. difficile TcdA has been positively correlated with asymptomatic carriage of C. difficile (32), although there are conflicting reports regarding whether naturally occurring antitoxin antibodies and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIG) affect the disease course (32, 69, 70, 72–83). Questions thus remain as to the extent to which antibody levels may confer protection against CDI.

Treatment of CDI and Disease Recurrence

Treatment of CDI generally involves prescription of either metronidazole or vancomycin. Metronidazole is the preferred treatment for mild disease due to its cost-effectiveness, but it is associated with rates of treatment failure higher than those for vancomycin in severe and complicated cases of CDI (84). Severe and recurrent cases may be treated with combination therapy of intravenous metronidazole with oral vancomycin or with a vancomycin taper. A more recently developed antibiotic, fidaxomicin, has a cure rate similar to that of vancomycin (85) but is currently recommended only for recurrent CDI due to its expense (84). In particularly complicated cases, surgical intervention may be required to remove the infected colon (84).

Recurrence of CDI following completion of treatment is common, occurring in up to 20 to 40% of cases after one episode and in up to 60% of cases after a first reoccurrence (86). This can occur via a relapse of the initial infection or from reinfection with spores from the environment (87, 88). The risk of recurrence is high because current therapies are limited to antibiotics that kill much of the gut microbiota along with C. difficile. This wholesale killing results in decreased colonization resistance due to the suppression of levels of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes (89–91). Vancomycin in particular has dramatic and long-lasting effects on the composition of the microbiota (61). Fidaxomicin, in contrast, has the least profound effect on the gut microbiota (90) and is associated with lower rates of CDI recurrence than vancomycin (85, 90). The serious problem of recurrence has led to interest in nonantibiotic therapies to treat CDI, including microbial-based therapies such as FMT and probiotics.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation and CDI

FMT seeks to reconstitute a healthy gut microbiota and colonization resistance against CDI through the administration of fecal preparations from a healthy donor. Numerous studies have shown that FMT restores microbial diversity in recipients (92–95). A recent study by van Nood et al. demonstrated that FMT dramatically increased cure rates among patients receiving vancomycin therapy for recurrent CDI (92). A recent review of case series studies demonstrated that 85% of 480 patients with recurrent CDI were successfully treated by using FMT (5), illustrating the potential of the use of microbes as a therapy to restore colonization resistance against CDI. Although whole fecal samples are most often administered in FMT, a few studies have demonstrated the use of defined bacterial consortia to cure CDI in mice (96) and humans (97–99). The RePOOPulate study, for example, recently utilized a defined mixture of 33 fecal bacterial strains to treat recurrent CDI (97). Trials testing the ability of the feces-derived bacterial spore preparation SER-109 to prevent CDI recurrence have unfortunately shown conflicting results (100, 101). Animal studies comparing FMT and defined bacterial consortia found that both approaches speed the restoration of the intestinal microbiota after antibiotic administration and promote the recovery of host secretory IgA (sIgA), intestinal epithelial MUC2, and defensin levels (102). Still, although FMT and more specific formulations are thought to restore colonization resistance by increasing gut microbial diversity, the exact mechanisms involved and the specific microbial species responsible for inhibiting C. difficile growth are not well described. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the efficacy of FMT for the treatment of CDI could lead to the development of more defined probiotic therapeutics to reestablish colonization resistance and ameliorate disease.

Clinical Trials Evaluating Probiotic Efficacy against CDI

Numerous clinical trials over the past few decades have evaluated the efficacy of probiotics against C. difficile (Table 1), identifying some individual strains and cocktails of beneficial microbes that may be candidates for further use in rationally designed combined microbial therapies. These trials tested primarily lactic acid-producing bacteria, including Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and Bifidobacterium species, and the probiotic yeast Saccharomyces boulardii. Most studies have evaluated the ability of probiotics to prevent primary CDI in patients receiving antibiotic therapy, although a few have specifically considered the prevention of recurrent CDI. The majority of trials to date have been unable to determine a statistically significant benefit of probiotic administration for the prevention of CDI, although a recent meta-analysis found benefits of some probiotic formulations (103). Many studies are limited by a number of biases, including a lack of appropriate randomization, poorly defined outcome measures, and reliance on post hoc analyses. Critically, most studies are small in scale and underpowered (104). Particularly in studies considering antibiotic-associated diarrhea as a primary outcome and C. difficile infection as a secondary outcome, low incidences of CDI in small study populations limit evidence of efficacy (105). Results of individual trials are also difficult to compare, as the selection and preparation of probiotic agents, treatment lengths, study methods, patient populations, and means of identifying CDI cases all vary.

TABLE 1.

Clinical trials evaluating probiotic efficacy in preventing primary and recurrent CDI

| Study type and reference | Yr | Species (daily dose[s]) | Endpoint | Patient population | Conclusion(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial trials showing benefit | |||||

| 334 | 2007 | Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus (4.2 × 1010 CFU) | Primary CDI | 112 adults | Decreased incidence of primary CDI in patients receiving antibiotics when given probiotic bacteria |

| 335 | 2010 | Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285, L. casei LBC80R (5 × 1010 CFU or 1011 CFU) | Primary CDI | 255 adult inpatients | Low- and high-dose probiotic mixtures confer protection against acquisition of primary CDI in adult patients |

| Bacterial trials showing no benefit | |||||

| 336 | 2001 | LGG (2 × 1010 CFU) | Primary CDI | 267 adults | No statistically significant difference in primary CDI in adults with probiotic administration |

| 337 | 2004 | L. acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum (2 × 1010 CFU) | Primary CDI | 138 adults >65 yr old | No statistically significant difference in primary CDI in elderly patients with probiotic administration |

| 338 | 2005 | LGG (80 mg lyophilized LGG given with 640 mg inulin) | Recurrent CDI | 15 adults with recurrent CDI | No significant difference in recurrent CDI detected |

| 339 | 2007 | L. acidophilus, B. bifidum, L. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus (1.5 × 109 CFU of each) | Primary CDI | 42 adults | No statistically significant difference in primary CDI in adults with probiotic administration |

| 340 | 2007 | L. acidophilus CL1285, L. casei LBC80R (5 × 1010 CFU) | Primary CDI | 89 adult inpatients | No statistically significant difference in primary CDI with probiotic administration |

| 341 | 2008 | L. acidophilus (Florajen) (6 × 1010 CFU) | Primary CDI | 40 adult inpatients | No statistically significant difference |

| 342 | 2009 | L. plantarum 299v (5 × 1010 CFU) | Recurrent CDI | 20 adults with at least 1 CDI episode in previous 2 mo | No statistically significant difference |

| 343 | 2010 | BIO-K+ CL128 (L. acidophilus CL1285 and L. casei) (49 g and then 98 g) | Primary CDI | 437 adult inpatients | No statistically significant difference |

| 106 | 2013 | L. acidophilus CUL60 and CUL21, B. bifidum CUL20 and CUL34 (6 × 1010 CFU) | Primary CDI | 2,941 adult inpatients >65 yr old | No statistically significant difference in primary CDI with probiotic administration |

| S. boulardii trials showing benefit | |||||

| 110 | 1994 | S. boulardii (1 g; 3 × 1010 CFU) | Recurrent CDI | 124 adults with initial and recurrent CDI | Combination of antibiotic and S. boulardii therapy decreases CDI recurrence relative to antibiotics alone |

| 344 | 2000 | S. boulardii (1 g) | Recurrent CDI | 32 adults with CDI | Statistically significant decrease in CDI recurrence with S. boulardii administration in combination with high-dose vancomycin but not metronidazole or low-dose vancomycin |

| 345 | 2005 | S. boulardii (500 mg) | Primary CDI | 246 children treated for otitis media or respiratory infections | S. boulardii decreased the risk of CDI in children receiving antibiotics although with a borderline level of significance |

| S. boulardii trials showing no benefit | |||||

| 346 | 1989 | S. boulardii (1 g) | Primary CDI | 180 adult patients | No statistically significant decrease in CDI |

| 347 | 1989 | S. boulardii (1 g) | Recurrent CDI | 13 patients | Non-statistically significant decrease in CDI diarrhea with S. boulardii administration |

| 348 | 1995 | S. boulardii (1 g; 3 × 1010 CFU) | Primary CDI | 193 adult patients receiving antibiotics | No significant difference in incidence of primary CDI between groups |

| 349 | 1998 | S. boulardii (226 mg) | Primary CDI | 69 patients >65 yr old receiving antibiotics | No statistically significant difference in incidence of CDI |

| 350 | 2006 | S. boulardii (1 × 1010 CFU) | Primary CDI | 151 adults receiving antibiotics | No statistically significant difference in incidence of CDI |

A recent large clinical trial tested the use of Lactobacillus acidophilus (CUL60 and CUL21) and Bifidobacterium bifidum (CUL20 and CUL34) in older patients receiving antibiotic therapy and found no benefit in terms of diarrhea severity or abdominal symptoms (106). Nevertheless, a few earlier trials and meta-analyses found benefits of other probiotic strains for the treatment of CDI. One meta-analysis found beneficial effects of using Saccharomyces boulardii, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), and certain probiotic mixtures to reduce the risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and of using S. boulardii to reduce the risk of CDI (15), although there has been some criticism of the trials included in this study (107, 108). Of the four trials able to meet the stringent criteria of a Cochrane review in 2008 (109), only one showed a significant benefit of probiotics (S. boulardii) for preventing CDI recurrence (110). Thus, although transfer of the whole microbiota through FMT can be effective in treating CDI, the administration of currently available individual probiotic strains and some cocktails does not appear to reliably confer protection.

Rational design of probiotic cocktails that provide the protective effects associated with FMT while avoiding the transfer of potentially deleterious strains would provide a much needed therapy for CDI. Below, we discuss individual strains associated with colonization resistance and inhibition of the deleterious effects of C. difficile. Further study of these strains could lead to the development of effective probiotic therapies for CDI.

Microbial Taxa Associated with Colonization Resistance against CDI

Recent studies have attempted to identify individual commensal microbes associated with colonization resistance or susceptibility to CDI in both humans and animal models. This work has the potential to uncover taxa that are responsible for the efficacy of FMT against CDI and that could be incorporated into future defined therapeutic cocktails. Several studies have identified bacterial taxa associated with colonization resistance versus the development of CDI in antibiotic-treated mice challenged with C. difficile. In general, mice that remain healthy after challenge with C. difficile exhibit increased levels of Firmicutes relative to mice that develop CDI (111). The families Porphyromonadaceae and Lachnospiraceae (111, 112) and the genera Lactobacillus, Alistipes, and Turicibacter (112) are also associated with colonization resistance against CDI in mice. In contrast, the Escherichia and Streptococcus genera (112) and the Enterobacteriaceae family (111) are correlated with increased susceptibility to CDI. A recent analysis identified individual bacterial species associated with colonization resistance in antibiotic-treated mice (113). This study identified Clostridium scindens, Clostridium saccharolyticum, Moryella indoligenes, Pseudoflavonifractor capillosus, Porphyromonas catoniae, Barnesiella intestinihominis, Clostridium populeti, Blautia hansenii, and Eubacterium eligens as being protective against CDI (113). The majority of these species belong to Clostridia cluster XIVa (phylum Firmicutes) (113). It has been suggested that members of Clostridia cluster XIVa may protect against C. difficile colonization through their ability to metabolize bile salts, as discussed below.

Human studies have also implicated particular microbial taxa in modulating susceptibility to CDI. In general, high levels of members of the phylum Bacteroidetes, consisting of strictly Gram-negative anaerobes, are thought to be protective against CDI, whereas increased numbers of Proteobacteria are thought to increase susceptibility (58, 59, 99, 114, 115). These correlations are also consistent with observations that FMT recipients have increased levels of Bacteroidetes and decreased levels of Proteobacteria following recovery from CDI (92, 93, 95, 116). More specifically, the family Ruminococcaceae and the genus Blautia are also associated with colonization resistance to CDI, while multiple groups have found that the family Peptostreptococcaceae and the genera Enterococcus and Lactobacillus are associated with susceptibility (58, 94, 113, 115, 117, 118).

Not all bacteria within the same group confer equivalent benefits of colonization resistance in humans. Some taxa of the family Lachnospiraceae (belonging to Clostridia cluster XIVa) are associated with protection in humans and mice (58, 115, 118), and FMT has also been shown to increase levels of Lachnospiraceae (116, 117, 119). However, some taxa within this family are actually associated with increased susceptibility to CDI (115). There are also conflicting reports regarding the role of some bacteria. For example, some studies associate streptococci with colonization resistance (118), and others associate them with susceptibility (58, 113). Such examples highlight the need for both experimental reproducibility and species- and strain-level specificity when determining probiotic potential. In order to develop targeted probiotic therapies, more studies will be needed to determine which bacterial strains are able to confer colonization resistance.

Mechanisms of Colonization Resistance against CDI

The mechanisms by which commensal bacteria mediate colonization resistance against C. difficile are incompletely understood; however, several possible mechanisms of colonization resistance are discussed below. It is likely that successful probiotic therapeutics for CDI would restore colonization resistance by one or more of these mechanisms.

Nutrient availability and competition for resources.

Commensal bacteria are thought to provide colonization resistance by occupying nutrient niches that could be exploited by C. difficile (120). Levels of nutrients and metabolites in the mouse gut are substantially altered by antibiotic treatment (121, 122), presumably due to the elimination of bacteria with specific metabolic functions. This change in nutrient availability in turn favors C. difficile growth. Antibiotic-treated, CDI-susceptible mice exhibit elevated intestinal levels of carbohydrates (121) and sialic acid (123), which enhance C. difficile growth. C. difficile has also been shown to consume succinate in vitro, which is present at higher concentrations in mice following antibiotic treatment (124). It is likely that restoration of the gut metabolome to a preantibiotic state through FMT is a factor in restoring colonization resistance to CDI.

The concept of niche exclusion in the gut environment has led to interest in the use of nontoxigenic C. difficile (NTCD) as a probiotic to prevent recurrent infections by toxigenic strains. This strategy is based on observations that people asymptomatically colonized with C. difficile are less likely than uncolonized individuals to develop symptomatic CDI when hospitalized (125). Administration of NTCD following clindamycin treatment in the hamster model protects most animals from death due to challenge with toxigenic C. difficile (126, 127). Human studies have also shown some promise for this strategy: phase 1 clinical trials indicated that oral ingestion of NTCD strain VP20621 is safe in healthy humans (128), and phase 2 trials showed that 11% of patients who received VP20621 developed recurrent CDI, in contrast to 30% of patients who received placebo (129). Although the mechanism by which NTCD is able to prevent colonization by toxigenic C. difficile has not been thoroughly investigated, it is hypothesized that prior NTCD colonization allows NTCD to outcompete newly introduced toxigenic strains (129). NTCD is thus an intriguing illustration of how certain bacterial species may occupy particular niches within the gut and provide colonization resistance against toxigenic C. difficile. However, it should be noted that toxigenic strain 630Δerm can share toxin genes with NTCD strains via horizontal gene transfer in vitro (130). Whether this transfer would be a potential danger in vivo by converting NTCD to a toxigenic form remains to be seen.

Bile salt metabolism and colonization resistance.

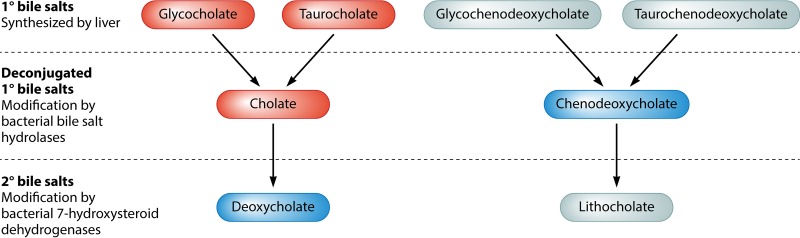

Levels of different bile salts in the gut are thought to affect C. difficile colonization by directly modulating its germination and growth. The primary bile salts glycocholate (GCA), glycochenodeoxycholate, taurocholate (TA), and taurochenodeoxycholate are synthesized by the liver to aid in the breakdown, digestion, and absorption of lipids in the small intestine (Fig. 2) (131). Although most bile salts are reabsorbed in the ileum and recycled by the liver, about 5% of bile salts pass into the large intestine, where they act as substrates for bacterial modification (131). Primary bile salts are deconjugated from their amino acid groups by bacterial bile salt hydrolases to make cholate (CA) and chenodeoxycholate (CDCA) (131). These bile salts can be further modified by bacterial 7-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases to form the secondary bile salts deoxycholate (DCA) and lithocholate (LCA) (131). Although a wide variety of bacteria are capable of carrying out bile salt deconjugation, only a few intestinal bacteria can synthesize secondary bile salts (131). CDCA inhibits the germination of C. difficile, while TA, GCA, and CA all enhance C. difficile germination (29, 132). DCA is also capable of enhancing the germination of C. difficile spores but inhibits the growth of vegetative cells (29, 132). These findings suggest that levels of different bile salts in the intestine exert fine control over C. difficile germination and outgrowth.

FIG 2.

Summary of bile salt metabolism. Primary bile salts (1°) produced by the host liver are modified and deconjugated by intestinal bacteria to form secondary bile salts (2°). Bile salts that stimulate the germination of C. difficile spores and thus increase susceptibility to CDI are shown in red. Bile salts that are known to inhibit the sporulation or outgrowth of C. difficile and therefore contribute to colonization resistance are shown in blue. Probiotics with 7-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity may enhance colonization resistance by decreasing the intestinal levels of glycocholate, taurocholate, and cholate and by increasing the levels of deoxycholate.

Antibiotic treatment results in alterations in bile salt levels that favor the germination and growth of C. difficile. Intestinal extracts from antibiotic-treated mice contain higher levels of primary bile salts than do extracts from untreated mice (121, 133, 134). Spores incubated with intestinal extracts from antibiotic-treated mice also germinate better than do spores incubated with untreated mouse extracts (133). The addition of the bile salt chelator cholestyramine to these intestinal extracts eliminated C. difficile germination, showing that germination occurs in response to bile salts in the mouse intestine (133). Furthermore, patients with CDI have higher levels of primary bile salts and lower levels of secondary bile salts than do healthy controls (135), and FMT has been shown to restore bile salt levels to those observed in healthy individuals (136). FMT efficacy thus appears to be mediated at least in part by restoring normal bile salt metabolism in CDI patients.

The role of secondary bile salts in protecting against C. difficile colonization suggests that bacteria with 7-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity could be used as probiotics against CDI. C. scindens, a Clostridia cluster XIVa bacterium that produces a 7α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, has been associated with colonization resistance against CDI in both mice and humans (113). The administration of C. scindens to antibiotic-treated mice restored DCA and LCA concentrations to preantibiotic levels, and intestinal contents from these mice were shown to inhibit the growth of vegetative C. difficile (113). Furthermore, feeding antibiotic-treated mice C. scindens prior to challenge with C. difficile significantly improved survival (113). C. scindens may thus be an attractive candidate for inclusion in novel probiotic formulations.

Production of anti-C. difficile compounds.

The production of molecules by the gut microbiota that have direct antibacterial activity may also contribute to colonization resistance against C. difficile. Organic acids produced by bacteria have been proposed to inhibit the in vitro growth of C. difficile, with culture supernatants from strains of Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, and Bifidobacterium species demonstrating pH-dependent anti-C. difficile activity (137–139). Growth of C. difficile is also inhibited by supernatants from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens cultures (140). Although the exact inhibitory molecule(s) within these culture supernatants remains to be identified, antibiotic-treated mice given B. amyloliquefaciens prior to challenge with C. difficile exhibit decreased disease severity (140), suggesting that these molecules are also active in vivo. Both lacticin 3147, produced by Lactococcus lactis strain DP3147 (141, 142), and thuricin CD, produced by Bacillus thuringiensis DPC 6431 (143), are bacteriocins that are inhibitory to C. difficile. Thuricin CD has potent activity against C. difficile without any apparent significant effects on other gut commensals (91, 143); however, mouse studies suggest that B. thuringiensis DPC 6431 spores pass through the mouse GI tract without germinating, limiting the probiotic potential of this strain (144). In contrast, lacticin 3147 is inhibitory toward other gut commensals (141), likely limiting its potential for restoring colonization resistance. More research is thus needed to identify strains that can both produce compounds specific for C. difficile and remain in the C. difficile-infected GI tract long enough to exert an effect.

Other Mechanisms of Action of Beneficial Microbes and Probiotics against CDI

Inactivation of C. difficile toxins.

Factors that directly target C. difficile toxins also have the potential to ameliorate disease by limiting the damaging effects of CDI on the GI epithelium. S. boulardii has been shown to secrete a 54-kDa protease capable of degrading TcdA, TcdB, and their brush border membrane receptors in vitro (145, 146). Blocking this protease abrogated protective effects of S. boulardii against C. difficile toxin-mediated epithelial cell damage in vitro (146), suggesting that S. boulardii protects against CDI pathogenesis at least in part via toxin degradation. However, this stands in contrast to data from another study that found no increase in survival of mice administered toxins preincubated with S. boulardii (147). The role of S. boulardii in direct toxin inactivation thus remains incompletely understood.

Probiotics also have the potential to inactivate C. difficile toxins indirectly by increasing the production of antitoxin neutralizing antibodies. TcdA-reactive IgM and IgA antibodies are induced by the administration of S. boulardii in vivo (148). One hypothesis is that such antibodies could prevent the binding of TcdA to its receptors on epithelial cells, thus limiting histological damage. This hypothesis is supported by data from a study in which a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies directed against TcdA and TcdB was administered intraperitoneally to hamsters prior to C. difficile challenge. This approach was found to protect against GI damage and death from CDI (149, 150). The administration of the TcdB-reactive antibody bezlotoxumab in combination with either metronidazole or vancomycin has also been shown to decrease rates of CDI recurrence in humans (151). It is unclear whether organisms other than S. boulardii can also induce antibodies with neutralization activity against C. difficile toxins. More studies are needed to determine the degree of protection conferred by C. difficile toxin-specific antibodies and to identify probiotic strains capable of stimulating such responses.

Antibody-mediated control of C. difficile bacteria.

Several studies have shown that the administration of probiotic organisms can increase total secretory IgA levels in rodents (148, 152–154), which may contribute to the control of C. difficile bacteria (72, 77–81). S. boulardii, for example, increases total secretory IgA levels in conventional rats and mice as well as in germfree mice colonized with S. boulardii (148, 152–155). Studies of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12, Escherichia coli EMO, and Lactobacillus casei and L. rhamnosus strains showed effects on total secretory IgA levels in rodent models (153, 156–158). However, the mechanisms by which some probiotics increase secretory IgA levels are not well understood, and more studies are needed to determine whether such changes in antibody production could protect against CDI.

Inhibition of mucus layer disruption.

Mucus forms a semipermeable barrier between the GI epithelium and the lumen. It consists of mucin glycoproteins, which are produced by goblet cells within the epithelium (159). The secreted glycoprotein MUC2 and the membrane-bound mucins MUC1, MUC3, and MUC17 form a dense meshwork to which numerous bioactive molecules, including trefoil factor peptides, resistin-like molecule β (RELMβ), Fc-γ binding protein, and antimicrobial peptides, as well as commensal bacteria are able to bind (160, 161). This mucus barrier normally prevents the direct contact of bacteria with the epithelium.

CDI is associated with changes in mucus thickness and composition (162) that promote the binding of C. difficile to mucus and increase the risk of epithelial cell damage from C. difficile toxins (163–166). Intestinal biopsy specimens from CDI patients show decreased MUC2 expression levels relative to those in healthy patients (162). C. difficile and CDI stool samples decrease MUC2 levels and alter mucus oligosaccharide composition in cultured human intestinal epithelial cells (162). Incubation with TcdA also decreases mucin exocytosis in the HT29-Cl.16E human colonic goblet cell line (167). As such, a key mechanism of FMT and probiotics in protecting against CDI may be to restore mucus composition in order to maintain an effective barrier.

A limited number of probiotics have been well studied with regard to the modulation of mucin production. Intestinal epithelial cells exposed to Lactobacillus plantarum 299v or LGG have been shown to upregulate MUC2 (168) and MUC3 (169) expression, respectively. In the case of LGG, this upregulation is mediated via the secreted soluble protein p40, which activates the epidermal growth factor receptor and induces mucin expression from GI epithelial cells (170). Preincubation of epithelial cells in vitro with L. rhamnosus ATCC 7469 has been shown to maintain mucin expression upon incubation with enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) (171). Interestingly, an increase in mucus layer thickness via the addition of exogenous mucus increased the ability of L. rhamnosus to prevent the adherence and pathogenic effects of ETEC, suggesting that an intact mucus layer may support the protective effects of probiotics. The induction of increased mucus and mucin expression has also been noted for the probiotic bacterial cocktail VSL#3 (L. casei, L. plantarum, L. acidophilus, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, B. longum, B. breve, B. infantis, and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus) incubated with HT29 cells in vitro (172) as well as in vivo when fed to laboratory rats (173). A probiotic yeast strain, Saccharomyces cerevisiae CNCM I-3856, also upregulates MUC1 mRNA expression in epithelial cells in vitro (174), possibly via the induction of butyrate (175, 176). However, some probiotic strains, such as E. coli Nissle 1917, have minimal effects on mucus (172). In addition to species differences, the in vivo abilities of particular probiotics to affect the mucus layer may furthermore differ depending on the age (177) and overall GI microbiota composition (178) of patients. Thus, currently, only some probiotic strains are clearly capable of influencing mucus production, and more research is needed to evaluate their effects on restoring mucus specifically in the context of CDI.

Maintenance of the intestinal epithelial cell barrier and tight junction expression.

Microbes may promote the maintenance of the epithelial barrier between luminal contents and host cells through the modulation of mucus production (as discussed above) or by influencing regulatory factors, such as cytokines, that affect intestinal permeability (see the discussion below on the cytokine milieu). However, many probiotics have also been shown to influence the barrier function of epithelial cells by modulating the expression of junctional complexes (Table 2). These complexes normally seal together adjacent epithelial cells and prevent the indiscriminate translocation of particles from the gut lumen into host tissues. Although the role of junctional complexes in the pathogenesis of CDI is not well studied, it is possible that reinforcing the GI epithelial barrier via modulation of junctional complexes may help to reduce the leakiness associated with CDI-induced inflammation and possibly help repair damage induced by C. difficile toxins.

TABLE 2.

Effects of probiotics on the gastrointestinal epitheliuma

| Organism and genus | Species | Strain(s), company, or trade name | Effect(s) on epithelial barrier | Model system(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||||

| Lactobacillus | L. rhamnosus | GG (ATCC 53103) | TER ↑ | Alcoholic liver disease in male Sprague-Dawley rats | 351 |

| L. rhamnosus | GG (ATCC 53103) | Prevented ↓ in ZO-1, claudin-1, symplekin, p130, and fordin | Chronic alcohol feeding in mice | 293 | |

| L. rhamnosus | GG (ATCC 53103) | Occludin, claudin-1, ZO-1 ↑ when given with gliadin | Caco-2 cells | 352 | |

| L. rhamnosus | GG (ATCC 53103) p40 and p75 proteins | PKCε and PKCβI membrane translocalization; prevents occludin, ZO-1, E-cadherin, and B-catenin redistribution in ERK1/2- and PKC-dependent manners | Caco-2 cells exposed to H2O2 | 353 | |

| L. rhamnosus | GG (ATCC 53103) | TER, claudin-1, ZO-1, and occludin ↑ | In vitro human epidermal keratinocytes | 185 | |

| L. rhamnosus | ATCC 7469 | ZO-1, TLR2, and TLR4 ↑; PKCα unchanged; prevents mucus disruption | ETEC-infected IPEC-J2 cells | 171 | |

| L. acidophilus | ATCC 4356 | TER ↑, ↑ occludin and ZO-1 phosphorylation | Control and EIEC-infected Caco-2 cells | 354 | |

| L. plantarum | ATCC 10241 | Transient TER ↑ | In vitro human epidermal keratinocytes | 185 | |

| L. plantarum | CGMCC 1258 | Prevented ↓ in occludin | ETEC-infected piglets | 355 | |

| L. plantarum | 299v | No change in bacterial translocation to cervical and mesenteric lymph nodes | 5-FU-treated rats | 356 | |

| Streptococcus | S. thermophilus | ATCC 19258 | TER ↑, ↑ occludin and ZO-1 phosphorylation | Control and EIEC-infected Caco-2 cells | 354 |

| Bifidobacterium | B. bifidum | WU12 | ↑ occludin mRNA in Caco-2 cells after TNF-α exposure | Caco-2 cells | 192 |

| B. longum | ATCC 51870 | TER (TLR2 dependent), claudin-1 and -4, ZO-1, and occludin ↑ | In vitro human epidermal keratinocytes | 185 | |

| B. infantis | Isolated from VSL#3 | Prevented TNF-α- and IFN-γ-induced TER ↓, ↑ claudin-3 and -4, occludin, and ZO-1; prevented redistribution of claudin-1 and occludin in vivo | T84 cells, IL-10-deficient mice | 357 | |

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||||

| Escherichia | E. coli | Nissle 1917 | ↑ ZO-1 in the absence of inflammation; ↑ ZO-1 and ZO-2 in DSS colitis; ↓ recruitment of inflammatory leukocytes to colon | Monoassociated mice and DSS colitis | 358 |

| Probiotic cocktails | L. rhamnosus and L. helveticus | R0011 and R0052 (Lacidofil) | Intestinal permeability ↓, ↓ bacterial adherence to epithelium | Chronic stress in rats | 359 |

| S. thermophilus and L. acidophilus | ATCC 19258 and ATCC 4356 | ↑ TER, ↑ phosphorylation of occludin and ZO-1 | Caco-2 cells, EIEC-infected Caco-2 cells | 354 | |

| Yeast | |||||

| Saccharomyces | S. boulardii | Biocodex | No change in TER in control or infected T84 cells; partial protection from ↑ HRP flux in Shigella flexneri coinfection; restoration or preservation of claudin-1 and ZO-2 expression at later time points | Control and Shigella flexneri-infected T84 cells | 190 |

| S. boulardii | Biocodex | Prevents EPEC-induced activation of the ERK1/2 MAP kinase pathway; preservation of ZO-1 distribution | EPEC-stimulated T84 cells | 186 | |

| S. boulardii | Biocodex | Prevented EHEC-induced MLC phosphorylation linked to ↓ TER | EHEC-infected T84 cells | 360 | |

| S. boulardii | Biocodex | Inhibited IL-1β- and TcdA-induced ↑ in IL-8 expression, ERK1/2 and JNK/SAPK but not p38 activation; ↓ ERK1/2 activation in TcdA-treated ileal loop | NCM460 human colonocytes; mouse ileal loop | 361 | |

| S. boulardii | Perenterol | ↑ brush border enzyme activity | Duodenal biopsy specimens from S. boulardii-treated healthy human volunteers | 362 | |

| S. cerevisiae | CNCM I-3856 | No effect on barrier function | IPEC-1 cells with ETEC exposure | 174 |

DSS, dextran sodium sulfate; EHEC, enterohemorrhagic E. coli; EIEC, enteroinvasive E. coli; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; IPEC-1, newborn piglet intestinal epithelial cell line; JNK/SAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase; MAP, mitogen-activated protein; MLC, myosin light chain; PKC, protein kinase C; TER, transepithelial resistance; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease.

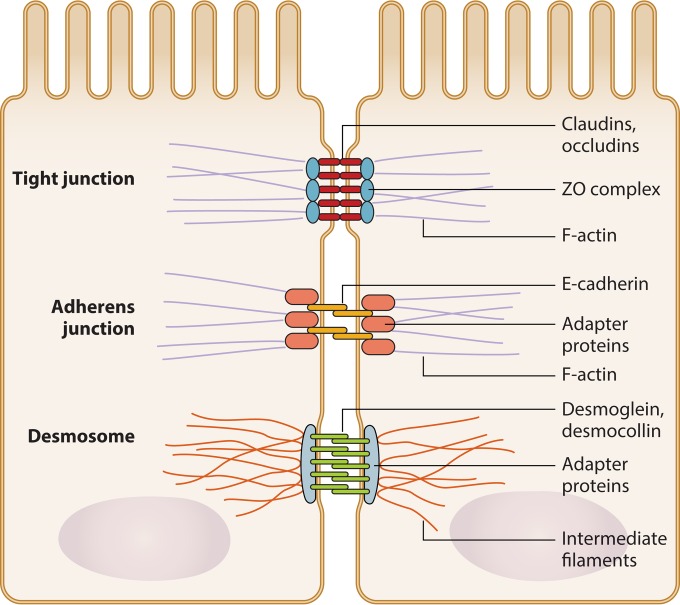

Junctional complexes are composed of tight junctions, adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes (179) (Fig. 3). Most work on junctional complexes and probiotic organisms has centered on tight junctions, whose transmembrane components include claudins, occludins, and junction-associated molecule (JAM) family proteins. These transmembrane components interact with plaque proteins, including zonula occludens (ZO) family members (180), in order to mediate intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal reorganization (181, 182). The expression of tight junction molecules in the healthy gut is modulated by numerous environmental signals, including metabolic compounds such as acetate and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (183), although the exact mechanisms by which this occurs are still unclear. Some studies suggest that butyrate, an SCFA whose level increases with probiotic administration, decreases intestinal permeability through the induction of AMP-activated protein kinase activity and the increased assembly of tight junctions in Caco-2 monolayers (184). Junctional complex expression is also influenced by innate immune functions of epithelial cells, such as by TLR recognition of microbial ligands (185).

FIG 3.

Epithelial cell junctional complex. Junctional complexes hold together adjacent epithelial cells. Tight junctions at the apical end of junctional complexes are composed of occludin and claudin proteins that span the intercellular space and bind intracellular adapter proteins, such as zonula occludens (ZO) complex proteins. Adherens junctions are composed of E-cadherins and adapter proteins. Desmosomes are formed of desmoglein and desmocollin proteins that bind internal adapter proteins. Adapter proteins associated with tight junctions, adherens junctions, and desmosomes in turn bind components of the cytoskeleton, including F-actin or intermediate filaments.

Several probiotic organisms are capable of modulating junctional complexes to restore or maintain the intestinal epithelial barrier. The probiotic yeast S. boulardii increases the expression of ZO-1 in T84 cells (186) and has been associated with decreased intestinal permeability in numerous studies (155, 187–190). Similarly, both Bifidobacterium longum and LGG have been shown to induce the upregulation of claudin-1, ZO-1, and occludin protein levels in keratinocytes (185). Intriguingly, the in vitro increase in keratinocyte transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) induced by a B. longum lysate, but not by an L. rhamnosus GG lysate, was abrogated in the presence of a TLR2-neutralizing antibody, suggesting that these bacteria act on different pathways to influence tight junction molecule expression (185). An in vivo infectious model recently demonstrated that a defined mixture of 33 probiotic bacterial strains prevented the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium-induced disruption of ZO-1 and claudin-1 in mice and ameliorated disease severity (191).

There is evidence that the effects of probiotics on epithelial cell junctional complexes are highly strain specific. One study using Caco-2 cells exposed to probiotics found that while all tested Bifidobacterium strains increased TER, a measure of barrier integrity, only 6 of 15 tested Lactobacillus strains showed a similar increase (192). Even fewer strains were able to prevent the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-induced decrease in TER (192). Furthermore, the effect of the most protective strain of B. bifidum (WU12) on TER was strikingly attenuated when it was heat killed, suggesting that metabolic or secreted factors produced by B. bifidum mediate beneficial effects (192). Another study found that L. plantarum L2 was able to reduce TNF-α levels, intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis, and ileal mucosa erosion in an ischemia reperfusion injury model (193). By reinforcing the GI epithelial barrier, probiotic organisms may help to repair or prevent damage induced by C. difficile toxins or host inflammatory immune cells.

Summary of Potential Mechanisms of Action of FMT against CDI and Implications for Probiotics

C. difficile infection is a toxin-mediated disease that leads to severe damage of the GI mucosa (Fig. 1B). Numerous factors may help to prevent initial colonization with C. difficile or to maintain an asymptomatic infection and limit damage after sporulation in susceptible individuals.

The phenomenon of colonization resistance in preventing CDI is particularly well studied and presents one major mechanism through which beneficial microbes may help to ameliorate disease pathogenesis and symptoms. Strains that are able to alter bile salt concentrations or limit the availability of other resources may discourage growth of and colonization by C. difficile. Delivery of NTCD is also a promising novel therapy due to its potential competition with toxigenic C. difficile for an intestinal niche (126, 127). Future work administering C. scindens and NTCD (128, 129) holds promise for the use of these strains as preventative therapies in antibiotic-treated patients or as treatments for CDI. Further studies on colonization resistance will help identify additional microbes that could be beneficial in treating CDI.

Direct targeting of C. difficile or its toxins is another way in which probiotics may protect against CDI even after pathogen colonization and sporulation. Indeed, the probiotic yeast S. boulardii has been found to secrete a protease capable of degrading C. difficile toxin A (145, 146). It is interesting to note that this is the only probiotic strain for which such direct anti-C. difficile toxin activity has been identified and one of the few strains shown to have efficacy against CDI in clinical trials (109, 110). The identification of other yeast or bacterial strains with antitoxin activity may provide further potential therapeutic strains.

Other probiotic strains may help to ameliorate disease symptoms and limit damage by promoting the reinforcement and repair of the epithelial barrier. Such reinforcement may help protect the host from increased exposure to C. difficile toxins. In vitro studies also suggest that the effects of probiotics may be greater with an intact mucus layer, suggesting that probiotics may be more beneficial as prophylactic agents. However, further studies are needed to determine whether the effects of these probiotic strains seen in vitro confer protection in the context of CDI.

Finally, the administration of probiotic organisms may be beneficial by harnessing the host immune response to alleviate CDI disease progression and symptoms. For example, increasing the production of secretory IgA may promote the sequestration of toxins within the intestinal lumen (72, 77–81, 148). Stimulation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as TLRs has also been found to limit CDI severity (194). However, such a strategy must be pursued with care: it has also been hypothesized that some degree of damage in CDI may be immune mediated, with decreased toxin-associated damage being seen in mice deficient in neutrophils, mast cells, or the inflammatory cytokine gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (194). Although live probiotics may have adverse effects in severely immunocompromised individuals (195, 196), probiotic strains that are able to attenuate inflammatory responses in immunocompetent hosts may thus limit host-induced histological damage and improve disease symptoms. In order to identify optimal probiotics for the treatment of CDI, it will be crucial to identify those strains that are able to alleviate symptoms associated with deleterious inflammatory responses without undermining the ability to control C. difficile infection. Current knowledge of immunomodulatory effects of probiotics and implications for their use in GI diseases are discussed in further detail below in the context of UC.

ULCERATIVE COLITIS

Ulcerative colitis is a serious GI disorder currently affecting an estimated 1 million to 1.3 million people in the United States (197, 198). UC is more common in developed countries and in urban areas. The incidence and prevalence of UC and Crohn's disease (CD), another common form of IBD, are both highest in northern Europe and North America; however, incidence is also increasing in other regions of the world, including South America and Africa (197). Although often grouped together with CD, UC has an etiology distinct from that of CD, with different associated genes, inciting factors, responses to therapies, and affected bowel regions (22, 199).

UC pathology is characterized by diffuse mucosal inflammation and histological alterations limited to the mucosal layer of the colon (200). The inflammation seen in UC is chronic but waxes and wanes in intensity. Various degrees of immune cell infiltration may be observed in the mucosa depending on whether the individual is experiencing active disease or remission (22). In active disease, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and granulocytes may all be seen within the mucosa (201). Ulcerations, goblet cell depletion, and fewer crypts are also observed. In advanced disease, epithelial cells may undergo dysplasia and increase the risk of epithelial cancer (202, 203). Symptoms of mild to moderate disease may include rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal cramping, while more severe cases may present with fever, weight loss, anemia, and severe abdominal pain (22). UC may also cause extra-abdominal symptoms affecting the eyes, kidneys, and joints (204).

Risk Factors for Developing Ulcerative Colitis

The development of UC is thought to be a multihit process, with genetic predispositions leading to disease only upon exposure to as-yet-poorly understood environmental triggers. Several genetic correlations have been identified, with a recent meta-analysis identifying 47 loci associated with IBD, 19 of which were specific for susceptibility to UC rather than CD (199). Still, twin studies have shown that the overall genetic concordance for UC is low relative to those for CD and other genetic diseases (22). Environmental exposures related to a Western diet and lifestyle have also been linked to the development of UC (205, 206). Other known epidemiological risk factors include appendectomy (207) and smoking (208), both of which reduce disease risk.

Ulcerative Colitis Pathophysiology

Although the exact mechanisms of UC pathogenesis are still incompletely understood, disease is generally believed to stem from inflammatory immune responses to the microbiota in genetically susceptible individuals (209). The major factors contributing to active disease are thought to include impaired barrier integrity of the GI epithelium, an altered microbiota, and aberrant immune responses to GI antigens and microbes; these factors are discussed in more detail below (Fig. 1C). Other factors that may also play a role, such as adiposity, regulatory RNA, angiogenesis, and the inflammasome, have been reviewed elsewhere (210) and are not discussed here.

Intestinal permeability.

Intestinal permeability is a major component of UC pathology and may serve as a potential novel therapeutic target (211). Breakdown of the epithelial barrier may lead to increased and prolonged exposure to bacterial antigens or other insults that in turn may compound inflammatory responses and intestinal damage. Whether intestinal permeability is a cause or a consequence of disease is still a question of debate. However, several genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified numerous UC susceptibility loci that contain genes involved in intestinal permeability and pathogen recognition, suggesting a causative effect (199, 212, 213). Many of these genes are known to be expressed by epithelial cells, including GNA12, which is associated with tight junction assembly (199); CDH1, encoding the adherens protein E-cadherin (199, 212); and LAMB1, encoding the laminin beta 1 subunit expressed by the intestinal basement membrane. Some studies have also found UC susceptibility to be associated with polymorphisms in the multidrug resistance 1 gene (MDR1) (also known as ABCB1) encoding P-glycoprotein, a protein responsible for pumping substances out of epithelial cells to help maintain barrier function (213, 214).

The mucus layer that forms an additional barrier between epithelial cells and the GI lumen is dysregulated and thinned in individuals with UC (215, 216). This is proposed to be the result of defects in mucin production as well as increased numbers of mucus-degrading (mucolytic) bacteria in individuals with UC (217). Indeed, MUC2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, demonstrating the need for this factor for the maintenance of gut homeostasis (215). Nod-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein 6 (NLRP6), which is known to be important for mucin exocytosis from epithelial cells, has also been linked to colitis susceptibility in mouse models (218, 219). UC patients have significantly reduced numbers of mucin-containing goblet cells in uninflamed ileal biopsy specimens relative to controls (220), suggesting that dysregulation of mucus production occurs even in the absence of host inflammatory cell responses. Decreased mucus layer thickness allows increased contact between the microbiota and the epithelium in UC patients (221) and may exacerbate immunostimulation and inflammation.

The microbiota and dysbiosis.

The microbiota of UC patients is vastly different from those of healthy controls, although it is unclear whether this is a cause or a consequence of the chronic inflammation associated with UC. Dysbiosis may be influenced by genetic risk factors leading to impaired intestinal epithelial barrier integrity as well as dietary factors such as high intake of fat, refined sugar, iron, and aluminum (222).

There are alterations in several bacterial groups within the microbiota of UC patients relative to healthy individuals. Like those suffering from CDI, UC patients have decreased prevalences of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes and increased prevalences of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria, especially Enterobacteriaceae (223, 224). UC patients were also specifically found to have increased prevalences of Porphyromonadaceae and enteroadherent E. coli in addition to decreased prevalences of Prevotella, Catenibacterium, Streptococcus, and Asteroleplasma species relative to healthy patients (224, 225). Patients with active UC disease have also been reported to have a decreased prevalence of Lactobacillus species relative to patients in remission (226).

The mechanisms by which dysbiosis influences the development of UC are currently unclear; however, it is possible that dysbiosis early in life may predispose individuals to UC by negatively affecting the maturation of the immune system (227). GI immune tissues such as Peyer's patches, isolated lymphoid follicles, and mesenteric lymph nodes are all underdeveloped in the absence of microbial stimulation (228). Indeed, models known to develop spontaneous colitis, including interleukin 10 (IL-10)- and T cell receptor-deficient mice, do not develop colitis if they are raised under germfree conditions (228–230), indicating that aberrant immune responses to a deregulated microbiota play a role in inciting colitis. Furthermore, cohousing of wild-type mice with colitis-prone Tbx21−/− Rag−/− mice induces the development of colitis in wild-type mice (228). Although the exact signaling pathways through which this susceptibility is conferred are still unclear, these data suggest that exposure to certain colitogenic strains of bacteria within a dysbiotic microbiota can be sufficient to induce colitis. Together, these studies demonstrate that dysbiosis is both a consequence of immune deregulation and a factor that affects disease susceptibility and progression.

Aberrant immune responses.

UC is characterized by the infiltration and activation of many immune cells in the mucosa, including neutrophils, macrophages (231), and T cells (232). These inflammatory cells are recruited and activated by the production of numerous chemokines and cytokines that are upregulated in the mucosa of UC patients, further promoting inflammation and damage in active disease (233). Serum levels of chemokines that attract monocytes, dendritic cells, T cells, and neutrophils, including CXCL5 and CCL23, are elevated in UC patients compared to healthy controls (234). Levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), macrophage inflammatory protein 3 (MIP3) (CCL23), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) (CCL2), MIP3β (CCL21), and granulocyte chemotactic protein 2 (CXCL6) are also elevated in the periphery of UC patients (234). CCL25-CCR9 interactions, which regulate leukocyte recruitment to the intestine, also play a role in mediating colitis (235). Novel antibodies such as vedolizumab and PF-00547659, which prevent homing of leukocytes to the gut, have been found to ameliorate symptoms of active UC in clinical trials (22). The ability to modulate immune cell recruitment and the level of inflammatory cytokines may thus confer protection against increased disease severity.

TNF-α.

In addition to their role in immune cell recruitment, inflammatory cytokines can be directly pathogenic. The best example of this is TNF-α, which promotes fibroblast proliferation, increased adhesion molecule expression, neutrophil activation, disruption of junctional complexes, and the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ (236). UC patients have increased levels of TNF-α relative to healthy controls (237). The administration of infliximab, a monoclonal antibody against TNF-α, has shown some success in the treatment of steroid-refractory UC (238), highlighting the critical role of this cytokine in mediating disease pathogenesis.

Th2 cells.

Despite the abundance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-16, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), that can be found in UC patients (234, 237, 239–241), UC has traditionally been considered a CD4+ T helper cell type 2 (Th2) disease (242, 243). This view stemmed from the observation that increased levels of Th2-associated cytokines, including IL-5 and IL-13, can be measured in UC patients and experimental colitis models (239, 243, 244). Th2-associated cytokines have been shown in some studies to induce damaging effects at the mucosa. IL-13, for example, is thought to mediate epithelial cell cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and barrier dysfunction in some situations (239, 245). However, the importance of Th2 cytokines in UC pathogenesis relative to other cytokine pathways is currently unclear.

Th17 cells.

Recent evidence also suggests an important role for Th17 cells, a subset of CD4+ T cells that secrete primarily IL-17 (242, 243), in UC pathogenesis. Th17 cells and their associated cytokines increase neutrophil recruitment to areas of inflammation, as discussed below; however, the extent to which Th17-associated cytokines such as IL-17A are pathogenic versus protective is controversial (246). A recent GWAS identified numerous Th17-related genes associated with UC susceptibility (199). Multiple genes in the IL-23 pathway that induces Th17 cell differentiation, including IL23R, JAK2, STAT3, and IL12B, were also associated with susceptibility to both UC and CD (199). Both rodents with colitis and patients with active UC disease have increased amounts of IL-17 and Th17 cells in the mucosa relative to controls (247–249). Although some studies have shown that antibody depletion of IL-17 increases the severity of acute colitis in mice (250), other mouse experiments conversely demonstrated that IL-17 receptor (IL-17R) deficiency reduces colitis severity (251). Novel drugs that block IL-17 activity have also been shown to confer protection in models of chronic colitis (252, 253). Thus, there is currently much evidence to suggest a critical role for Th17 cells and their associated cytokines in UC pathogenesis.

Neutrophils.

The recruitment and activation of neutrophils at the intestinal mucosa are striking features of UC pathophysiology (254, 255). Neutrophils are innate immune cells that normally protect the host against microbial pathogens and dying cells through pathogen phagocytosis and the production of reactive oxygen species, antimicrobial peptides, and proteases such as elastase that are exuded from specialized granules. Numbers of neutrophils are increased in both the periphery (256) and colons (257) of UC patients. Neutrophils secrete both proinflammatory factors such as IL-17 (258), leukotrienes, and CXCL8 (257) as well as anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 (259). Matrix metalloproteases, which are involved in the activation of chemokines such as CXCL5 and CXCL8, are also secreted by neutrophils to facilitate the recruitment of additional immune cells.

The exact role played by neutrophil expansion and activation in UC pathogenesis has been the subject of much debate, with different experimental colitis models suggesting different effects of neutrophils on disease severity. Neutrophils are important in wound healing and the maintenance of homeostatic processes through their phagocytosis of damaging cellular debris as well as through the secretion of growth-promoting factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), lipoxins, and protectins (257). Some studies have reported that depletion of Gr1+ CD11b+ cells, including neutrophils, exacerbates mouse models of colitis, suggesting a protective role for neutrophils (260, 261). However, other studies have demonstrated the opposite effect (262), perhaps due to differences in neutrophil depletion methods.

Although neutrophils are normally short-lived cells, a buildup of neutrophils in chronic UC inflammation can overwhelm the ability of resident macrophages to clear this cell population, leading to neutrophil necrosis and the release of damaging granule contents (257). Thus, the ability of certain factors to either inhibit (IL-8, IL-1, IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF], and C5a) (257, 263) or promote (IL-10 and TNF-α) (264, 265) neutrophil apoptosis can influence the degree of tissue damage. The massive transmigration of neutrophils through the epithelium and the release of elastase have also been associated with decreased expression levels of tight junction and adherens junction proteins (266). Elevated levels of fecal elastase have been found to correlate with disease severity in UC patients (267). It thus appears that neutrophils may contribute to both disease pathogenesis and recovery in UC.

Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis

Unfortunately, current treatment options for UC are limited and unable to induce remission in all patients. Given the inflammatory nature of this disease, most treatments entail immunosuppression. First-line treatments, typically sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylates, including mesalamine, olsalazine, and balsalazide, induce remission in about 50% of patients (22, 268). If 5-aminosalicylate therapy fails, patients with milder UC may be prescribed oral glucocorticoids or immunosuppressives (269). Azathioprine (270), 6-mercaptopurine (271), and monoclonal antibody inhibitors of TNF-α, including infliximab (272) and adalimumab (273, 274), have all shown efficacy as immunosuppressives for UC. In more severe cases, patients may receive intravenous glucocorticoids or cyclosporine to attempt to induce remission (269, 275). Maintenance therapy during remission may include oral or rectal 5-aminosalicylates or thiopurines, azathioprine, or 6-mercaptopurine.

Side effects of these treatments can be serious, including acute pancreatitis and bone marrow suppression (276). Patients who are unable to tolerate treatment or whose disease does not respond to treatment may develop serious complications such as toxic megacolon, bowel perforation, uncontrolled bleeding, and carcinoma or high-grade dysplasia, each of which is an indication for colectomy (277). Unlike CD, colectomy is often curative for UC. However, as many as 40 to 50% of patients develop pouchitis, whereby the artificial rectum surgically created from ileal tissue after colectomy becomes inflamed (278). Pouch failure is estimated to occur in 4 to 10% of patients (22, 279). This inflammatory condition is thought to result from changes in the microbiota within the ileal pouch, but the disease mechanism is still unclear (279). These side effects and the often limited effectiveness of current treatments mean that novel treatments for UC are needed.

Ulcerative Colitis and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

Given that UC is thought to stem from dysbiosis and aberrant immune responses to the microbiota, there was early interest in the use of probiotics and FMT to treat UC. However, the mechanisms by which FMT may ameliorate UC are unknown, and the use of FMT as adjunctive therapy remains controversial (280–282). Following FMT, IBD patients exhibit microbiome compositions that resemble those of their donors (24, 283–285). A recent randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy of FMT to that of a water enema control found a significant difference in levels of remission between the two groups, with 24% of FMT-treated patients achieving clinical remission (24). However, another randomized clinical trial in the same year reported no statistically significant difference in remission rates between patients who received FMT from a healthy donor (41% remission) and control patients who received FMT using their own feces (25% remission) (285). A recent meta-analysis of case series studies of FMT for the treatment of IBD showed that 45% of patients achieved clinical remission following treatment, with higher rates of remission being observed for CD patients than for UC patients (286). More research is needed to determine why some IBD patients receiving FMT experience remission (283) while others have no change in symptoms despite alterations in their gut microbiomes (284). The identification of microbial taxa that are associated with remission in patients who respond to FMT treatment could result in the development of more targeted probiotic therapeutics with greater efficacy.

Clinical Trials of Probiotics and Ulcerative Colitis

Although this field is still in its infancy, recent clinical trials and meta-analyses suggest that probiotics may be a viable option for adjuvant therapy in some UC patients (Table 3). A recent systematic review of clinical trials evaluating probiotics for the treatment of IBD concluded that although there was no evidence to suggest benefit in CD treatment, probiotics and prebiotics were useful in helping to induce and maintain remission of UC (16). Twenty-one trials using probiotics for UC treatment were identified in this review, with most trials considering either E. coli Nissle 1917 or the probiotic cocktail VSL#3. One double-blind double-dummy study showed that E. coli Nissle 1917 therapy was as effective as mesalamine in maintaining remission (17). Another study showed significantly greater induction of remission among pediatric UC patients treated with VSL#3 than among placebo-treated controls (18). A few smaller-scale studies showed that other probiotics, including Bio-Three (Enterococcus faecalis, Clostridium butyricum, and Bacillus mesentericus) (287) and Bifidobacterium breve (288), also reduced disease activity. Thus, although there is still a paucity of well-designed, large-scale, randomized, controlled trials, there is the potential that microbial therapy could serve as a viable alternative to pharmacological therapy for UC.

TABLE 3.