Abstract

Defective viruses often have pivotal roles in virus-induced diseases. Although Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is etiologically associated with Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) and primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), defective KSHV has not been reported. Using differential genetic screening methods, we show that defective KSHV is present in KS tumors and PEL cell lines. To investigate the role of defective viruses in KSHV-induced pathogenesis, we isolated and characterized a lytic replication-defective KSHV, KV-1, containing an 82-kb genomic deletion of solely lytic genes. Cells harboring KV-1 escaped G0/G1 apoptosis induced by spontaneous lytic replication occurred in cells infected with regular KSHV but maintained efficient latent replication. Consequently, KV-1-infected cells had phenotypes of enhanced cell proliferation and transformation potentials. Importantly, KV-1 was packaged as infectious virions by using regular KSHV as helpers, and KV-1-like variants were detected in cultures of two of five KSHV cell lines and 1 of 18 KS tumors. These results point to a potential role for defective viruses in the regulation of KSHV infection and malignant transformation.

Herpesviruses establish and maintain persistent latent infection in the hosts after primary infection. Upon activation by specific host or environmental factors, the viruses reactivate, producing virions that spread to other hosts (60). Latent infection of gammaherpesviruses is often associated with the development of malignancies, while lytic replication is a termination phase leading to cell deaths (35, 75). The switch of viral latent infection to lytic replication is initiated with the induction of transcription transactivators of viral immediate-early genes and coordinated with cellular transcription factors (66, 75).

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), is a gammaherpesvirus etiologically associated with Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and multicentric Castleman's disease (47). The establishment of KSHV latent infection in the hosts could occur years before the development of KS (23, 24). In KS lesions, KSHV maintains latency in most spindle cells (16, 18, 41, 54, 55, 69, 71, 72), the hallmark of KS; however, it also undergoes lytic replication in a small proportion of tumor cells (9, 13, 36, 51, 68-70, 72). Similarly, lytic replication has also been observed in a small proportion of cells in PEL and in multicentric Castleman's disease (53, 68, 74). Although lytic replication is a termination phase for most herpesviruses, for KSHV it also produces oncogenic, angiogenic, and antiapoptotic viral products (1, 4, 10, 22, 38, 45, 62) that could potentially promote cell proliferation in tumor cells. Thus, the role of KSHV lytic replication in tumor development is controversial (43, 46).

In KSHV-infected PEL cell lines, the majority of the cells maintain latent infection, whereas a small proportion of them also undergoes spontaneous lytic replication (44, 48, 78, 80, 83). KSHV replication in KSHV-infected cell lines appears to closely mimic that in KS tumors. Using these cell lines, several KSHV immediate-early genes have been identified and shown to be capable of activating viral lytic replication (29, 40, 42, 73, 82).

Defective viruses are commonly found in viral infections; many of them play pivotal roles in the development of viruses-induced diseases (3, 7, 30-32, 49, 52, 57, 65, 67, 77). Defective viruses have been described in herpesviruses (20, 21). Early studies have demonstrated the ability of defective herpesviruses in regulating viral infection (20, 21), including the modulation of persistent latent infection both in vitro and in animal models, characterized by cellular proliferation and transformation (12, 15, 19, 58, 59, 63). In the present study, we have shown that defective KSHV is present in KS tumors. In addition, we have demonstrated that cells harboring a lytic replication-defective KSHV not only maintain efficient latent replication but also have enhanced cell proliferation and transforming potentials. Our results suggest that KSHV lytic replication is not essential for promoting cell proliferation in our system and, more importantly, illustrate a potential role for defective viruses in the regulation of KSHV infection and malignant transformation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

KS specimens and sample preparation.

KS specimens were obtained from the University Hospital of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. KS lesions were biopsied during regular clinical examinations, and the diagnosis of KS was confirmed by histopathologic examination. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, ethanol precipitated, resuspended in deionized distilled water at 100 ng/μl, and stored at 4°C.

PCR-based differential genetic screening (DGS) method.

Two PCR assays, one for detecting latent nuclear antigen (LNA) and one for detecting KS330, were carried out simultaneously on the same specimen. The relative amplification efficiencies of the two assays were calibrated with genomic DNA from a full-length recombinant KSHV BAC36 (81). A specimen that has substantially lower KS330 signal is likely to have defective KSHV with deletion in KS330 locus. The primers used for the assays are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

KSHV primers used for PCR-DGS and mapping of KV-1 genome

| Orf or region | Primer | Sequence | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | KS33 | 5′-CGGTTTGCTTTCGAGGACTATT-3′ | 473 |

| KS34 | 5′-ATTTGACAGGCGAGACGACAG-3′ | ||

| Orf4 | KS11 | 5′-TAACATCCATGAAAGCGAAAGGTA-3′ | 523 |

| KS12 | 5′-GTTAGGGCGACAGCGGTTAGTAGT-3′ | ||

| K2 | KS23 | 5′-AATGCTTCCGCGACCTCTG-3′ | 430 |

| KS24 | 5′-AAAACACGCACCGCTTGACC-3′ | ||

| K6 | MIP-1F | 5′-GGTAGATAAATCCCCCCCCTTTG-3′ | 490 |

| MIP-1R | 5′-AGCATATAAGGAACTCGGCGTTAC-3′ | ||

| Orf16 | KS13 | 5′-CCTGTGGATTAAACGAACCTGAGT-3′ | 434 |

| KS14 | 5′-CAATAATGCAATGCTTCCCAATAG-3′ | ||

| Orf25, MCP | MCP-1F | 5′-GAAATTACCCACGAGATCGC-3′ | 327 |

| MCP-1R | 5′-AGGCAACGTCAGATGTGAC-3′ | ||

| Orf26, KS330 | KS330F | 5′-GACTCTTCGCTGATGAACTGG-3′ | 569 |

| KS330R | 5′-AGCACTCGCAGGGCAGTACG-3′ | ||

| Orf26, KS330 | KS330F2 | 5′-TCCGTGTTGTCTACGTCCAG-3′ | 232 |

| KS330R2 | 5′-AGCCGAAAGGATTCCACCAT-3′ | ||

| Orf25-27 | KS9 | 5′-TGCGTGGTGTCGTGTGATGCTTAC-3′ | 1,603 |

| KS10 | 5′-AGGGTTCAGTGTCCGGCAGGTAGA-3′ | ||

| Orf29a | KS15 | 5′-AAAGCCGCGCCTATTGG-3′ | 410 |

| KS16 | 5′-TCTTTCCGTGTCTCCTTGGTATTA-3′ | ||

| Orf41 | KS17 | 5′-TCACATCACCGGACCAGACACT-3′ | 213 |

| KS18 | 5′-GATAGGGGGATGAGCCAGAATGAT-3′ | ||

| Orf50 | KS19 | 5′-GGCCACCGGTAGTTCACAGACG-3′ | 506 |

| KS20 | 5′-GTCGCCTCTGCCGCCGTAGC-3′ | ||

| Orf54 | KS27 | 5′-AACGACGCCGGATTTGACG-3′ | 401 |

| KS28 | 5′-TGGGTATGTTTTCGGACGCTATTT-3′ | ||

| Orf56 | KS29 | 5′-TAGACCAGATCAGGGGCAAACTCA-3′ | 586 |

| KS30 | 5′-TGGTCGCCTGGAAATATCACACTT-3′ | ||

| Orf57 | Orf57F | 5′-CAGGGGGCAAAGACGACGAACTC-3′ | 482 |

| Orf57R | 5′-GCGACTCTGCATGCCTGGGATAG-3′ | ||

| K9, vIRF | KS25 | 5′-TGGAGCCGGACACGACAACTAAGA-3′ | 688 |

| KS26 | 5′-GGCCCGGAGACCCCACTGC-3′ | ||

| Orf60 | KS47 | 5′-CCGCCTTGGCCTGGATAAACC-3′ | 578 |

| KS48 | 5′-GCTCAGCGATGCCGACAAGGACT-3′ | ||

| Orf65 | KS43 | 5′-GACGCCGCGGAAACTCG-3′ | 206 |

| KS44 | 5′-GTGGCTCGCATGAATACCC-3′ | ||

| K12 | KS45 | 5′-ATGCCCTCGATACGCCTGCTCTTC-3′ | 333 |

| KS46 | 5′-TGCCCTCCTCCCTCCTCACTCC-3′ | ||

| K13 | KS55 | 5′-AAAAACGCGGGTCTAAGTGAAGC-3′ | 193 |

| KS56 | 5′-ACGGATGACAGGGAAGTGGTATTG-3′ | ||

| Orf72 | KS53 | 5′-GTCGATAATAGAGGCGGGCAATGA-3′ | 507 |

| KS54 | 5′-CCGCGCTTTTTAACTTCTGACTCT-3′ | ||

| Orf73, LNA | Orf73IF | 5′-GTAGGAAACGAAACAGGT-3′ | 821 |

| Orf73IR | 5′-ATTCTTGGATGCTTCTTCT-3′ | ||

| K14 | K14F | 5′-GGGCGCCGCGTAGTGGAG-3′ | 323 |

| K14R | 5′-GCGCAGGTGAGGGCAGCAGAG-3′ | ||

| Orf74 | KS21 | 5′-GCGGGCAGGAGCGATAGATA-3′ | 361 |

| KS22 | 5′-ATAACACATGGCCTGCTTGCTGAC-3′ | ||

| Orf75 | KS31 | 5′-AACGTGGCCAGGTACTTTGTGATA-3′ | 508 |

| KS32 | 5′-TGTCGCGATAGAGGTTAGGGTAGG-3′ | ||

| RHS | K15F | 5′-TTATAATGTGGAAAGTGCTACCT-3′ | 271 |

| K15R | 5′-ACAAACTTTAACAACCGAACTACT-3′ | ||

| RHS-TR | KS49 | 5′-GCACATAACAAGCAAAGAAGC-3′ | 416 |

| KS50 | 5′-GCGGGGGCGGGGACCAG-3′ | ||

| TR | KS58 | 5′-CGGGGCGCGGGGTGTTC-3′ | 102 |

| KS59 | 5′-TGCGAGGAGTCTGGGCTGTCTTGT-3′ | ||

| TR-vIRF | KS59 | 5′-TGCGAGGAGTCTGGGCTGTCTTGT-3′ | 2,164 |

| KS60 | 5′-ACATTTCTGGTGGGGTTGG-3′ | ||

| Junction | KS59 | 5′-TGCGAGGAGTCTGGGCTGTCTTGT-3′ | 271 |

| J604 | 5′-GCCGGGCGACGAAGATAGCAC-3′ |

DNA hybridization.

Dot blot and Southern blot hybridizations were performed essentially as previously described (25). For dot blot hybridization, DNA loading was calibrated by hybridization with a β-actin probe.

Detection of HHVs.

PCR assays for different HHVs, including herpes simplex virus type 1 (79), herpes simplex virus type 2 (79), varicella-zoster virus (64), cytomegalovirus (17), Epstein-Barr virus (39), HHV-6 (79), and HHV-7 (8) were performed as previously described. The primers used are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for the detection of different HHVs

| Virusa | Primer | Sequence | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 | HSV1-F | 5′-CCAACTACCCCGATCATCAG-3′ | 532 |

| HSV1,2-R | 5′-AGCGGGGCTGCGTTCGGATGG-3′ | ||

| HSV-2 | HSV2-F | 5′-CTCCGATTCGACCACATATG-3′ | 657 |

| HSV1,2-R | 5′-AGCGGGGCTGCGTTCGGATGG-3′ | ||

| VZV | VZVD-F | 5′-GTAACCCCGCGTCCTTCATTTC-3′ | 376 |

| VZVD-R | 5′-CCCGGCTTTGTTAGTTTTGGTTG-3′ | ||

| EBV | EBVBamF | 5′-CCCGGGGCCACCTTCATCAC-3′ | 428 |

| EBVBamR | 5′-GGCAGCCTAATCCCACCCAGACTA-3′ | ||

| CMV | HCMV-F | 5′-CCAAGCGGCCTCTGATAACCAAGCC-3′ | 435 |

| HCMV-R | 5′-CAGCACCATCCTCCTCTTCCTCTGG-3′ | ||

| HHV-6 | HHV6-F | 5′-AAGCTTGCACAATGCCAAAAAACAG-3′ | 223 |

| HHV6-R | 5′-CTCGAGTATGCCGAGACCCCTAATC-3′ | ||

| HHV-7 | HHV7-F | 5′-TATCCCAGCTGTTTTCATATAGTAAC-3′ | 186 |

| HHV7-R | 5′-GCCTTGCGGTAGCACTAGATTTTTTG-3′ |

HSV-1 and -2, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2; VZV, varicella-zoster virus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; HHV-6 and -7, human herpesvirus types 6 and 7.

KVNAtyping.

KVNAtyping was performed as previously described (25).

KV-1 genomic mapping.

Genomic mapping was carried out by PCR assays and genomic library screening. All KSHV primers were designed from BC-1 KSHV sequences except RHS sequence primers, which were from BCBL-R KSHV sequences (50, 61). The sequences of all PCR primers and the sizes of their products are listed in Table 1. A cosmid library was constructed from C29 DNA by using SuperCos 1 cosmid vector according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Statagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and screened as previously described (61). The inserts were excised with EcoRI and mapped to confirm the organization of KSHV genes.

Detection of KV-1 virions.

PD-1 and C10 cultures were treated with tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate (TPA) at 20 ng/ml for 4 days to induce lytic replication. Virions were isolated as previously described (76), treated with pronase to destroy any viral capsids, and then treated with DNase to destroy any physically associated DNA (56) before being incubated with DNA extraction solution containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 200 μg of proteinase K/ml in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.8) buffer. The virion DNA was then purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and analyzed with major capsid protein (MCP)-PCR and junction-PCR assays.

KSHV latent and lytic protein expression.

Immunofluorescence assay was performed as previously described (26). The percentage of positive cells was calculated from the number of positive cells versus total cells (range, 48 to 238) counted in randomly selected ×40 microscope fields. LNA protein was detected with a rat monoclonal antibody (ABI, Maryland, Md.) and revealed with a rabbit anti-rat immunoglobulin-fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Minor capsid protein (mCP) was detected with a mouse monoclonal antibody (26) and revealed with a rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin-fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (Sigma). Cells were counterstained with Evan's blue solution. All of the cells were stained red, whereas those reacted with specific antibodies fluoresced green.

Apoptosis and cell cycle analysis.

DNA strand breaks and DNA content was determined by TdT assay and propidium iodide staining, respectively, as previously described (27). For DNA strand break analysis, HL60 cells treated with 0.15 μM camptothecin for 4 h were used as positive controls, while untreated HL60 cells were used as negative controls.

Cell proliferation and transformation assays.

Cell proliferation rate was determined by using a cell proliferation assay kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.). Soft agar assay was performed as previously described (22). The results of colony-forming efficiencies are the averages of three replicates, with standard deviations from one representative experiment.

RESULTS

Defective KSHV is present in KS tumors.

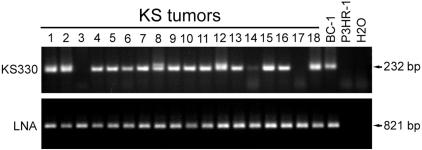

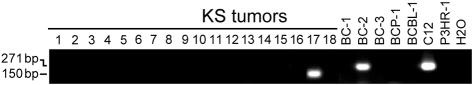

To detect defective KSHV, we developed a PCR-based DGS method (PCR-DGS) in which two PCR assays for detecting sequences of different KSHV genes are simultaneously carried out on the same specimen. Since all genes have one copy in each KSHV genome, similar levels of signals in both assays should be observed after calibration of amplification efficiencies if only full-length KSHV genome is present. In contrast, if the specimen harbors a dominant defective genome with deletion in one of the two genes, we expect to observe differential signals with absent or weak signal from the affected gene. In the present study, we have chosen LNA (open reading frame 73 [Orf73]) as the target sequence for the first PCR assay because LNA is an essential latent gene for KSHV episomal persistence, serving as a stable marker for KSHV genomes. We designed a second PCR assay for KS330 (Orf26), which is the most commonly used locus for diagnostic detection of KSHV. As expected, all 18 KS tumors examined had similar LNA signals (Fig. 1). Most tumors also had similar levels of KS330 signals. However, differential signals were detected in three tumors: tumors 3 and 17 had negative KS330 signals, and tumor 14 had substantially lower KS330 signal. These results indicated that defective KSHV with deletions in KS330 locus were present in these tumors.

FIG. 1.

Detection of defective KSHV in KS tumors by PCR-DGS. All KS tumors examined had similar levels of LNA signals; however, KS tumors 3 and 17 had no KS330 signal, whereas tumor 14 had much weaker signal, indicating that these tumors harbored defective KSHV.

Isolation of a defective KSHV, KV-1.

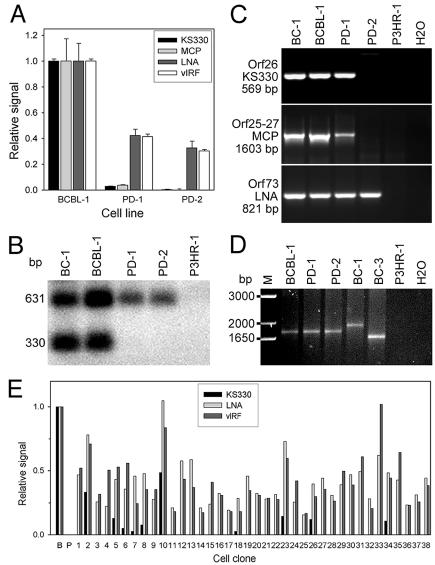

Further virologic and phenotypic characterizations of the defective KSHV detected by PCR-DSG were not possible because of the limited amount of the paraffin-embedded specimens. Isolation of cell lines harboring defective KSHV would be ideal for such characterizations. Although isolation of stable KSHV-positive cell cultures from KS tumors remains elusive (37), cell lines established from patients with PEL are extensively used to study KSHV replication (2, 14, 24, 25, 56). For that reason, we used PCR-DGS to examine cultures of five KSHV-infected cell lines (BC-1, BC-2, BC-3, BCP-1, and BCBL-1). Initial screening yielded ambiguous evidence of defective KSHV in these cultures (data not shown). However, the PCR-DGS could fail to detect defective KSHV if it is only present in a subset of cells that harbor high copies of KSHV genomes (20 to 100 copies/cell). Therefore, we turned to dot blot hybridization-based DGS with probes designed from LNA and three other KSHV loci/genes: KS330, MCP (Orf25), and vIRF (Orf-K9). Substantial differences in hybridization signals were detected in one of the cultures, PD-1, derived from BCBL-1 cell line after 8 months of standard tissue culture (Fig. 2A). When initially isolated, PD-1 displayed a higher cell proliferation rate than its parental cell line (see below section) and continued to increase over time for approximately two additional months before it stabilized at a high rate thereafter. The resulting stable culture was named PD-2. Although strong LNA and vIRF signals were detected in PD-1 and PD-2 cultures, KS330 and MCP signals were much lower in PD-1 cells (2.87% [P = 0.0001] and 3.76% [P = 0.010], respectively) than in BCBL-1 cells (100%) and were 0 in PD-2 cells (P = 0.00007 and 0.009, respectively) (Fig. 2A). The relative ratios of KS330/LNA and KS330/vIRF signals dropped from 1 in BCBL-1 cells to 0.0678 and 0.0693 in PD-1 cells and to 0 in PD-2 cells. Interestingly, compared to BCBL-1 cells (100%), LNA signals were detected at a reduced level in PD-1 (42.3% ± 4.83%; P = 0.014) and PD-2 (32.63% ± 5.26%; P = 0.020) (Fig. 2A) cells. Similar results were obtained with vIRF probe (41.43% ± 1.89% [P = 0.00001] for PD-1 and 30.30% ± 1.08% [P = 0.0005] for PD-2), indicating that there were fewer KSHV genomes per cell in both cultures than in BCBL-1 culture. Southern blot hybridization assay confirmed the low (0.64% of BCBL-1 cells) and zero KS330 signals in PD-1 and PD-2 cells, respectively (Fig. 2B). Similar to LNA and vIRF, KS631 (Orf75) probe signals from PD-1 and PD-2 cells were 32 and 28% of those found for BCBL-1 cells. To further confirm that PD-2 was negative for the KS330 and MCP loci, we performed more-sensitive PCR assays (Fig. 2C). Indeed, PD-2 cells were negative in the KS330- and Orf25-27-PCR assays, whereas both BCBL-1 and PD-1 cells were positive. All cultures had strong signals in an LNA-PCR assay. Together, these results indicated that a defective KSHV with genomic deletions, including KS330 and MCP loci, were present in PD-1 and PD-2 cultures and was named as KV-1. KV-1 was apparently more aggressive and replaced the regular KSHV in PD-1 culture. The PD-2 culture was subsequently cultured for an additional 4 months (for a total of 14 months) to establish a stable cell line. Although KS330 and MCP signals remained undetectable in PD-2 culture by either hybridization or PCR assays after this period, LNA and vIRF signals remained constant, suggesting the stability and efficient latent replication of KV-1 in PD-2 cells.

FIG. 2.

Detection and isolation of defective KSHV in KSHV-infected cell lines. (A) Results from dot blot hybridization with KS330, MCP, LNA, and vIRF probes demonstrating that PD-1 cells have much lower KS330 and MCP sequence signals than BCBL-1 cells and that PD-2 cells had no detectable KS330 and MCP sequence signals. The results show the averages from one representative experiment, along with the standard deviations. (B) Results of Southern blot hybridization with KS330 and KS631 dual probes demonstrating the absence of KS330 signals in PD-1 and PD-2 cells in relative to KS631 sequence signals. BC-1 and P3HR-1 were positive and negative cell controls, respectively. (C) Results of PCR assays for the detection of KS330, Orf25-27, and LNA sequences, demonstrating that PD-2 culture was negative for KS330 and Orf25-27 sequences, whereas BCBL-1 and PD-1 cultures were positive for KS330 and Orf25-27 sequences. BCBL-1, PD-1, and PD-2 cell lines were positive for LNA. BC-1 and P3HR-1 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (D) KVNAtyping demonstrating that PD-1 and PD-2 harbored the same KVNAtype as their parental cell line BCBL-1. Both BC-1 and BC-3 had different KVNAtypes. (E) KSHV signals in 38 monoclonal cultures derived from a PD-1 culture, as determined by dot blot hybridization with KS330, LNA, and vIRF probes. Two cell types were present in the PD-1 culture: cells harboring only KV-1 and cells harboring both the regular KSHV and KV-1. The results presented are the averages from one representative experiment. BCBL-1 (B) and P3HR-1 (P) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

To exclude the presence of other herpesviruses, specific PCR assays for Epstein-Barr virus, HHV-6, HHV-7, herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, varicella-zoster virus, and cytomegalovirus were performed. Like the parental cell line, PD-1 and PD-2 cultures were negative for all of these viruses (data not shown).

Origin of KV-1.

LNA has molecular polymorphism due to sequence variations in its internal repeat domain, defining a stable but unique genotype, named KVNAtype, for an individual KSHV isolate (25). To confirm that KV-1 was originated from BCBL-1 KSHV, KVNAtype analysis was carried out for PD-1 and PD-2 cells. The same BCBL-1 KVNAtype was identified in both PD-1 and PD-2 cells (Fig. 2D), confirming the BCBL-1 origin of the variant.

To further characterize and determine the origin of KV-1, a PD-1 culture was subcloned by limiting serial dilution. A PD-1 culture was chosen because of the dynamic transition of KSHV genomic population in this culture, which contained both the regular KSHV and KV-1 genomes, thus providing clues for the origin of the variant. Of a total of 38 resulting monoclonal PD-1 cell cultures, 28 had no detectable KS330 signal but had LNA and vIRF signals equal to 16 to 102% of those found in BCBL-1 cells by dot blot hybridization (Fig. 2E). The remaining 10 cultures had KS330 signals (3 to 49% of BCBL-1 cells) in addition to LNA and vIRF signals (18 to 105% of BCBL-1 cells) (Fig. 2E). The absence of KS330 signal in 28 PD-1 clones was further confirmed by PCR analysis (data not shown). Therefore, as we expected, two cell types were present in PD-1 culture: cells harboring only KV-1 genomes and cells harboring both regular KSHV and KV-1 genomes, suggesting that the variant had originated from a single viral genome.

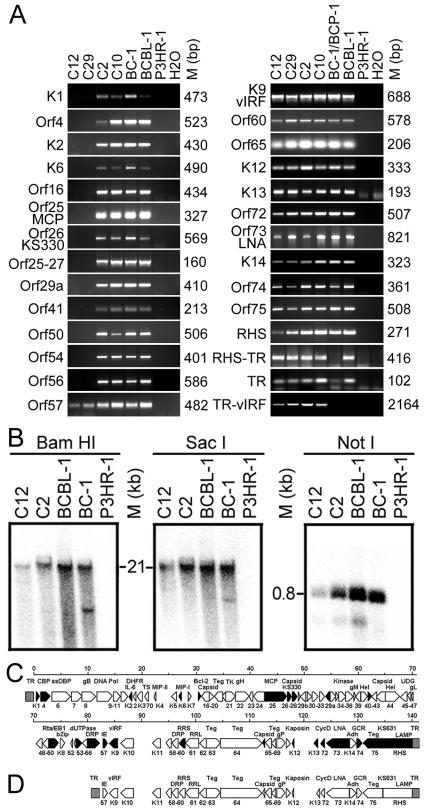

Mapping of DNA sequence deletion in KV-1 genome.

PCR analysis was performed on PD-1 monoclonal cell cultures for 27 Orfs or genomic regions scattered across the entire KSHV genome. All KS330-positive clones (C2 and C10) were positive for all of the Orfs or genomic regions examined (Fig. 3A), confirming the presence of regular KSHV genomes in these clones. In contrast, all KS330-negative clones (C12 and C29) were negative for Orfs from nucleotide position 1 (K1) to 81,967 (Orf56) and positive for Orfs or genomic regions from nucleotide position 82,717 (Orf57) to 140,500 (RHS) and terminal repeat (TR) sequences (Fig. 3A), indicating the presence of a single KSHV variant in PD-1 cell culture. To identify the deletion junction, a PCR assay was designed to amplify sequences from TR to vIRF (TR-vIRF). As expected, a PCR product of 2.1- to 2.2-kb was obtained from all clones (Fig. 3A). No TR-vIRF product was obtained for BC-1 and BCBL-1 cell lines since they do not harbor KV-1. Sequencing of the TR-vIRF product identified the junction point to be 288 bp inside the first TR unit and 82,094 bp inside the long unique coding region (LUR) (Fig. 4). Hence, KV-1 genome has an LUR of ∼58.5-kb, whereas the remaining 82-kb genome has been deleted.

FIG. 3.

Genomic mapping of KV-1. (A) Representative PCR assays on two KS330-negative (C12 and C29) and two KS330-positive (C2 and C10) monoclonal cultures indicated that only sequences from nucleotide positions 82717 (Orf57) to 140500 (RHS) and TR sequences were present in the KV-1 genome. BC-1 and BCBL-1 cells were used as positive controls in all experiments except the RHS-PCR assay, in which BC-1 was replaced with BCP-1 because RHS sequences in BC-1 differ from those in BCBL-1 (50). DNA from P3HR-1 cells and H2O were used as negative controls. The deletion junction sequences were PCR amplified with forward primer from TR and reverse primer from vIRF sequences (TR-vIRF). (B) Southern blot hybridization with BamHI-, SacI-, and NotI-digested C12 and C2 DNA with a TR probe to determine TR structure and length in KV-1 genome (see the text for details). (C and D) Diagrams illustrating the regular BCBL-1 KSHV genome (C) as postulated from the known BC-1 KSHV genome (61), along with the putative KV-1 genome that contains a 58-kb LUR flanking by 21-kb TR sequences (D). Orfs and regions marked in black blocks were used for PCR genomic mapping.

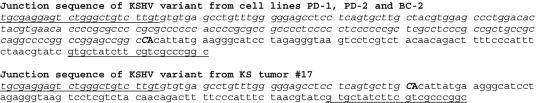

FIG. 4.

Junction sequences of KSHV defective viruses. Sequences in italics are from KSHV TR, while sequences in regular type are from KSHV LUR. The junction nucleotides were labeled in boldface capital letters. Underlined sequences were used as primers for the detection of the junction sequences and defective variants.

To further confirm the genomic deletion, a cosmid library was constructed from C29 cells harboring only KV-1 genomes. Of 106 colonies screened with mixed probes from nucleotide positions 1 to 82094, no positive clone was identified. In contrast, 42 of 2 × 105 colonies were found to be positive by using either vIRF or RHS as probes. Six of the clones with insert sizes ranging from 8 to 46 kb were isolated. One of these clones with a 46-kb insert was positive for sequences from Orf57 to LNA, as well as TR sequences, but negative for sequences from K14 to RHS by hybridization and PCR assays, whereas another clone with an 8-kb insert contained part of the RHS sequence and ca. 6.3 kb of the TR sequence. These results were consistent with those obtained by PCR mapping and suggested that KV-1 retained a large proportion of TR region. Preliminary physical mapping of these clones indicated that the genetic organization in KV-1 genome was identical to the same region of the regular BCBL-1 KSHV genome.

To determine the length of TR region, we performed Southern blot hybridization with C12 harboring only KV-1 genomes and C2 harboring both KV-1 and regular KSHV genomes by using TR probe (Fig. 3B). When digested with BamHI and SacI that do not cleave TR, both C12 and C2 produced a single band of ∼21 kb, which was similar to that of the BCBL-1 cell line. A 0.8-kb band was identified for all of the cell lines digested with NotI that cleaved once in each TR. From these results, we concluded that KV-1 retained the original BCBL-1 KSHV TR structure and almost the entire length of TR region. Figure 3C and D show the genomic map for regular KSHV and a putative genomic map for KV-1.

KV-1-like variants are present in KSHV-infected cell lines and KS tumors.

The identification of KV-1 junction makes it possible to design a specific assay for the diagnostic detection of KV-1. A sensitive junction-PCR assay with primers designed from the identified deletion junction sequences was developed and used to directly detect the prevalence of KV-1 in KSHV-infected cell lines and KS tumors. Amplification of a 271-bp band indicates the presence of KV-1 genomes. When cultures of the same five KSHV cell lines were reexamined, an additional BC-2 culture produced a band with a size similar to that of C12 (Fig. 5). Sequence determination indicated that the BC-2 variant had the same junction point as KV-1 had (Fig. 4). However, examination of earlier-passage BC-2 cells failed to detect the deletion junction, suggesting that, similar to PD-1, the BC-2 variant was newly derived in the culture.

FIG. 5.

Detection of KV-1-like variants in KS tumors and KSHV-infected cell lines by junction-PCR amplification. One of eighteen KS tumors and BC-2 culture was found to be positive by junction-PCR, indicating the presence of KV-1-like variants.

When the 18 KS tumors were reexamined, one of them tumor 17, which also had differential signals in the original screening, generated a band of ∼150 bp, whereas all of the other specimens were consistently negative (Fig. 5). Sequencing of the 150-bp band identified a KSHV variant similar to KV-1 but with a new junction point at 409 bp inside the first TR unit and 82,094 bp inside the LUR (Fig. 4).

KV-1 maintains efficient latent infection but is defective in lytic replication.

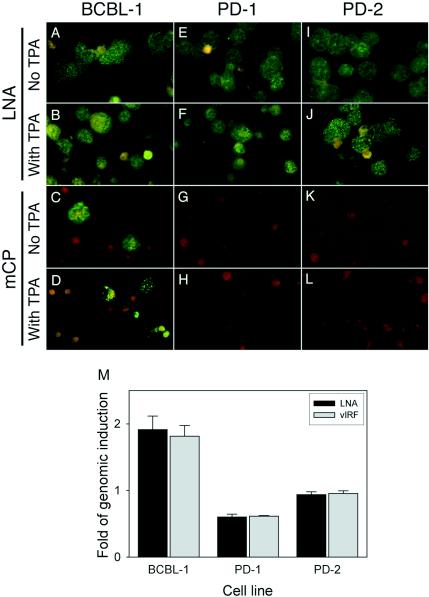

The fact that PD-2 was maintained for 14 months with stable LNA and vIRF signals strongly indicated that KV-1 maintained stable latent infection. Examination of KV-1 genome revealed that all of the deleted KSHV genes are exclusively lytic genes, whereas all of the known latent genes are preserved (Fig. 3D). To further examine KSHV replication, cells were stained for the expression of mCP (Orf65) to detect lytic replication and for the expression of LNA to detect latent replication. PD-1 and PD-2 cells were compared to parental BCBL-1 cells harboring a replication-competent KSHV (56) that constantly underwent spontaneous lytic replication in a small proportion of cells (25). All cells from three cell lines were LNA positive and showed a typical speckle nuclear staining pattern (Fig. 6A, E, and I), confirming that, like BCBL-1 cells, PD-1 and PD-2 cells maintained efficient latent replication. A total of 4.410% ± 0.790% of the BCBL-1 cells stained mCP positive, whereas only 0.013% ± 0.025% of PD-1 cells showed mCP-positive staining (P = 0.009), and no mCP-positive staining was detected in PD-2 cells (P = 0.009) (Fig. 5C, G, and K). We further determined whether KV-1 could be induced into lytic replication in PD-1 and PD-2 cell cultures by TPA, a phorbol ester previously shown to induce KSHV into lytic replication in BCBL-1 cell line (56). KSHV genomic signals in BCBL-1 cells were increased 1.815 ± 0.1615 (P = 0.006)- and 1.913 ± 0.204 (P = 0.022)-fold after TPA induction, as assayed by dot blot hybridization with vIRF and LNA probes, respectively (Fig. 6M). In parallel, the percentage of mCP-positive BCBL-1 cells was increased to 15.903% ± 2.632% after TPA treatment (P = 0.00009) (Fig. 6D), confirming the induction of lytic replication. In contrast, only a minor increase of mCP-positive cells (0.063% ± 0.075%) for PD-1 culture (P = 0.182), and no positive cells for PD-2 culture were observed after TPA induction (Fig. 6H and L). Accordingly, no genomic induction was observed for PD-1 and PD-2 cells after TPA induction (Fig. 6M). These results confirm that KV-1 is lytic replication defective.

FIG. 6.

KSHV latent and lytic replication in KV-1-infected cells. (A to L) Detection of KSHV latent and lytic replication in uninduced and TPA-induced cells by measuring the expression of LNA and mCP by immunofluorescence assay. All cells from BCBL-1, PD-1, and PD-2 cultures expressed LNA with or without TPA induction (A, B, E, F, I, and J). Only BCBL-1 cell line had some uninduced cells stained mCP-positive (C), and the number of positive cells was increased after TPA induction (D). mCP expression was rarely or not detectable in PD-1 and PD-2 cells with or without TPA induction (G, K, H, and L). (M) Results from dot blot hybridization with LNA and vIRF probes, demonstrating the increase of KSHV genomes by TPA induction in BCBL-1 cells but not in PD-1 and PD-2 cells. The results are averages from one representative experiment with the standard deviations.

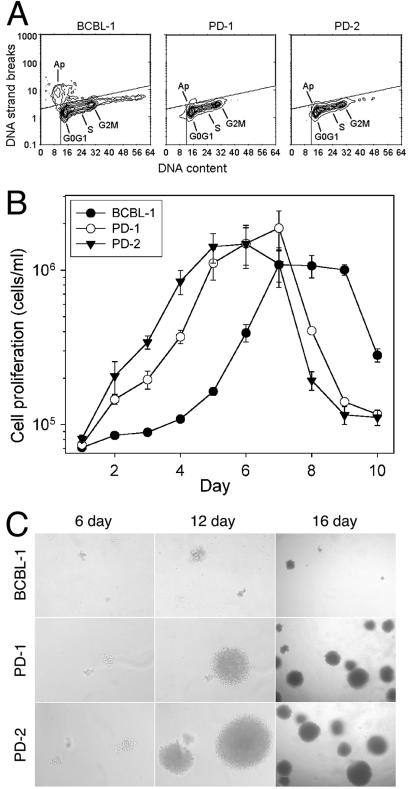

KV-1 had more aggressive malignant phenotypes.

We further determined the phenotypic alterations of KV-1. Since lytic replication, which could lead to cell deaths, was constantly detected in some BCBL-1 cells but not in PD-2 cells and rarely in PD-1 cells (Fig. 6C, G, and K), cell cycle progression and apoptosis were examined. PD-1 and PD-2 cells had only slightly more cells in the G0/G1 and S phases and slightly fewer cells in the G2/M phases than BCBL-1 cells (39.5 and 40.3% versus 37.4% for G0/G1 phase, 45.4 and 44.4% versus 43.9% for S phase, and 15 and 15.4% versus 18.8% for G2/M phase); however, they had much fewer cells (3.9 and 2.3%) undergoing apoptosis than BCBL-1 cells (15.6%) (Fig. 7A). The apoptotic rates in PD-1 and PD-2 cells were similar to that found in the negative control HL60 cells (2.7% [data not shown]). Since most BCBL-1 apoptotic cells were in G0/G1 phase, the PD-1 and PD-2 cells appeared to resist G0/G1 cell arrest and apoptosis. Indeed, PD-2 had the highest cell proliferation rate and reached late log phase the earliest, followed by PD-1 and then the parental cell line (Fig. 7B). The cell doubling times of PD-1 and PD-2 cells were 2.09 ± 0.18 (P = 0.004)- and 3.34 ± 0.17 (P = 0.0009)-fold shorter than that of BCBL-1 cells in optimal condition.

FIG. 7.

Phenotypes of KV-1-infected cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle and apoptosis of BCBL-1, PD-1, and PD-2 cells. Although PD-1 and PD-2 cells had only minor differences from BCBL-1 cells in cell cycle progression, they had much fewer cells undergoing apoptosis than BCBL-1 cells. (B) Cell proliferation rates of BCBL-1, PD-1, and PD-2 cells. PD-1 and PD-2 cells had higher proliferation rates and reached late log phase earlier than their parental BCBL-1 cells. The results are averages of three replicates with the standard deviations from a representative experiment. (C) Representative fields of soft agar assay on days 6, 12, and 16 (magnifications, ×10, ×10, and ×4, respectively), showing that PD-1 and PD-2 colonies had higher growth rates than BCBL-1 colonies. The same colonies were documented on days 6 and 12 to facilitate comparison.

KSHV-infected cell lines are transformed as defined by their anchorage-independent growth (11). To determine whether PD-1 and PD-2 cells retained the transforming property, soft agar assays were performed. Compared to BCBL-1 cells (7.3% ± 0.6%), PD-1 and PD-2 cells had higher colony-forming efficiencies in soft agar (15.9% ± 1.5% [P = 0.004] and 19% ± 1.9% [P = 0.012], respectively). PD-1 and PD-2 cell colonies also grew faster than BCBL-1 cell colonies (Fig. 7C). Together, these results indicate that PD-1 and PD-2 had enhanced malignant phenotypes.

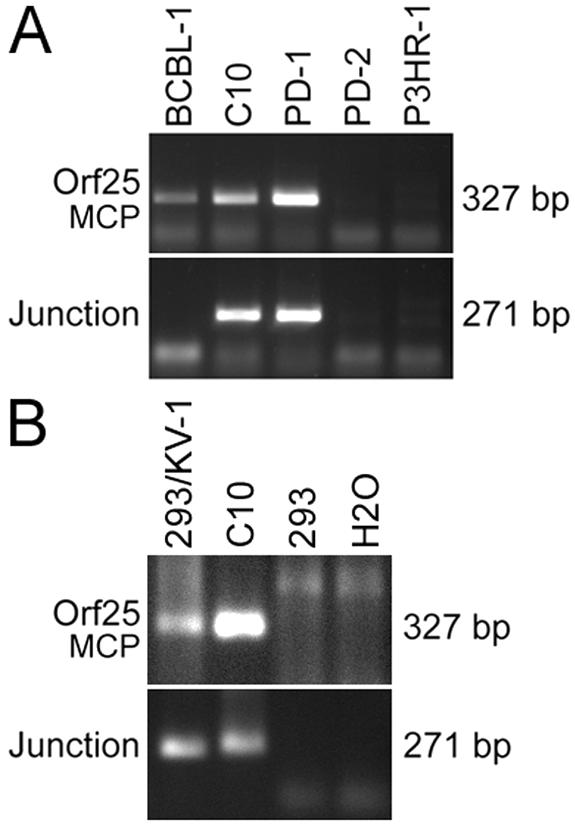

KV-1 can be packaged as infectious virions with regular virus as a helper.

Because KV-1 is defective in lytic replication, it is unlikely that the variant itself could produce infectious virions. However, since the packaging signals in TR region are preserved (Fig. 3D), KV-1 can potentially be packaged into virions by using regular KSHV as helper viruses. To determine whether KV-1 can be packaged as virions, we used TPA to induce PD-1 and C10 clone, both of which contain both KV-1 and regular KSHV. BCBL-1 and PD-2 cells were used as controls. Supernatants were then subjected to differential centrifugation to isolate virions. Virion preparations were further treated with pronase and DNase to destroy any viral capsids and physically associated DNA, respectively. Virion DNA was then extracted and subjected to PCR amplification (Fig. 8A). MCP signals were detected in virion preparations from BCBL-1, C10, and PD-1 cells, indicating the presence of regular KSHV virions in the supernatants of induced cells. No MCP signal was detected in virion preparations from PD-2 and P3HR-1 cells. As expected, junction-PCR detected specific signals in virion preparations from C10 and PD-1 cells but not in virion preparations from BCBL-1 cells, which only harbored regular KSHV, or from PD-2 cells, which only harbored KV-1.

FIG. 8.

Detection of infectious KV-1 virions. (A) Detection of KV-1 virions. DNA from purified virions was subjected to PCR amplification for detecting regular KSHV genomes (MCP-PCR) and KV-1 genomes (junction-PCR). Virions from C10 and PD-1 cells were positive for junction-PCR, indicating that KV-1 was packaged as virions. (B) KV-1 virions were infectious. 293 cells were infected with KV-1 virions from C10 cells and maintained for four passages over 12 days before being examined for KV-1 signal. KV-1-infected 293 cells were positive for MCP and junction sequences, indicating the presence of both regular KSHV and KV-1.

To further determine whether KV-1 virions were infectious, we used a virion preparation from C10 cells to infect 293 cells. The KV-1-infected 293 cells were then maintained for four passages over a period of 12 days, and its total DNA was extracted and subjected to PCR amplification. Both regular KSHV (MCP-PCR) and KV-1 (junction-PCR) were detected in 293 cells infected with KV-1 virions (Fig. 8B). In a parallel experiment, 293 cells infected with virus preparation from BCBL-1 cells were only positive for MCP-PCR but not junction-PCR (data not shown). From these results, we concluded that KV-1 was only packaged as infectious virions in cells containing both KV-1 and regular KSHV.

DISCUSSION

Using DGS methods, we have shown that defective KSHV is present in 3 of 18 KS tumors, including one with a KV-1-like variant, and in 2 of 5 cultures of KSHV-infected cell lines. Early studies for detecting KSHV sequences in KS tumors with limited sets of primers, such as KS330, usually had only 70 to 95% positive rates. Although the failure to reach 100% detection rate was often attributed to low-quality of DNA, particularly those from paraffin-embedded specimens, the presence of defective KSHV could also be accounted for such outcomes. Further examination by multiple PCR-, hybridization-, or microarray-DGS methods should reveal more defective KSHV in KS tumors, including those that have a mixture of regular and defective KSHV. Identification of additional KSHV variants could in return facilitate the development of specific assays for the detection of these variants in clinical specimens.

Since the establishment of stable KSHV-positive cell culture directly from KS lesions is not feasible (37), we have not been able to directly characterize defective KSHV in KS tumors. Nevertheless, we have isolated and characterized a lytic replication-defective KSHV, KV-1, from KSHV-infected cultures. PD-2 and PD-1 cells harboring KV-1 had no and weak viral lytic replication, respectively, which was consistent with deletion of lytic genes in KV-1 genome. In contrast, both PD-1 and PD-2 cells maintained efficient latent replication. Although viral genome copies in PD-1 and PD-2 cells were lower than in parental BCBL-1 cells, PD-2 cells maintained stable KV-1 genome copies months after the initial isolation. A similar observation was made for KV-1-positive PD-1-derived monoclonal cell cultures. Furthermore, PD-1 and PD-2 cells maintained efficient LNA protein expression at levels similar to that of BCBL-1 cells. These results indicate that KV-1 maintains stable episomal persistence, which are consistent with observations by others that LNA and TR sequence are the sole elements needed for stable maintenance and replication of KSHV episomes (5).

Compared to parental cell line BCBL-1, PD-1 and PD-2 had higher cell proliferation rates and enhanced transforming potentials. PD-1 and PD-2 cells also had lower apoptotic rates than BCBL-1 cells. The high apoptotic activity in BCBL-1 cells, most of which were in G0/G1 phase, also correlated with lytic replication, suggesting that KSHV lytic replication was capable of triggering G0/G1 cell arrest and apoptosis. It has been reported that lytic replication of herpesviruses induces apoptosis, whereas latent replication prevents cells from apoptosis (28, 33, 34). It appears that cells infected with KV-1 escape spontaneous lethal lytic replication avoiding G0/G1 apoptosis, which could account for their enhanced cell proliferation and transformation potentials. Interestingly, in advanced stage of KS tumors, reduced KSHV lytic protein expression is correlated with decreased apoptosis without compromising latent protein expression (72), an expected scenario if infection by lytic replication-defective KSHV is present and progresses to dominance such as is observed with KV-1 in PD-1 culture. Further investigations of regulation of cell cycle progression and apoptosis by KSHV and its defective viruses are warranted.

Results from the characterizations of KV-1 have also shed light on the role of lytic replication in KSHV-induced malignancies. The deleted region contains exclusively lytic genes, many of which, such as K1, vIL-6, vMIP-I, vMIP-II, and vBcl-2, are capable of regulating cellular signaling pathways involved in cell cycle progression and apoptosis (47). It has been postulated that lytically infected cells and the expression of these regulatory genes are important in sustaining KS tumors by constantly recruiting new cells for subsequent transformation, directly or through a paracrine mechanism (46, 47). Our data suggest that KSHV lytic replication and lytic genes are not essential for sustaining cell growth in PD-1 and PD-2 cells. As discussed above, defective lytic replication was likely the reason why PD-1 and PD-2 cells could escape apoptosis, leading to higher cell proliferation rates than BCBL-1 cells.

Although defective lytic replication of herpesviruses is a disadvantage for viral spread and propagation, viral transmission could potentially be achieved through aggressive cellular proliferation and blood circulation of virus-infected cells within the host, as well as mucosal contacts of the infected subject with a new subject. In fact, a recent study has elegantly demonstrated donor cell transmission in posttransplant KS patients (6). Such a scenario could also occur in other modes of KSHV transmission. Defective viruses could also maturate with coexisting regular viruses as helpers and spread and infect new cells or hosts. Indeed, cells harboring both KV-1 and regular KSHV (PD-1 and C10) can be induced to produce infectious KV-1 virions (Fig. 8).

Although the latency of herpesviruses is primarily controlled at the gene expression level (60, 66), our results suggest that genetic alterations such as genomic deletions and mutations of lytic cycle genes could potentially lead to defective lytic replication and render the viruses undergoing permanent latent replication. We proposed genomic alterations as an alternative mechanism that controls latency in herpesviruses. As demonstrated with KV-1, lytic replication-defective viruses have an advantage for cell proliferation and episomal propagation. The detection of a KV-1-like variant in BC-2 culture suggests that defective KSHV could be present in other cell lines. In fact, long-term culture of KSHV-infected cell lines leads to their reduction of inducibility for lytic replication (unpublished results). Since KSHV-infected cell lines, including BCBL-1, were clonal, as demonstrated by analysis of immunoglobulin heavy-chain rearrangements and restriction enzyme pattern of KSHV TR region (2, 11, 14, 61), these cell lines were likely originated from clonal viral infection, suggesting that the genetic alterations of viral genomes such as those identified in BCBL-1 and BC-2 cultures occurred after initial viral infection. Genomic mapping also showed that there was only one KSHV variant in PD-1 and PD-2 cells, suggesting that KV-1 originated from a single viral genome and was subsequently propagated and segregated to progeny cells. This conclusion was further supported by the isolation of PD-1 monoclonal cell lines harboring only KV-1 genomes, as well as monoclonal cell lines harboring both KV-1 and the regular BCBL-1 KSHV genomes. Since cells harboring KV-1 genomes had a growth advantage, it is expected that they would outgrow cells harboring regular KSHV genomes.

The detection of KV-1-like variants in a BC-2 culture and one KS lesion suggest that the KV-1 junction sequences are likely “hotspots” for generating genomic deletion and lytic replication-defective viruses. KSHV TR region contains highly repetitive sequences with high GC content, which could render the region prone to recombination. On the other hand, analysis of the junction sequence from KSHV LUR failed to identify any specific features that could render it vulnerable to genetic alterations. Nevertheless, if “hotspots” are indeed present in the KSHV genome, they are more likely to undergo genetic alterations to generate defective viruses, which can then control KSHV latent infection. In this scenario, the regulation of KSHV latent infection is operated at the genomic level and should have the same effect as those operated at the gene expression level.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Chamness, R. Clark, A. Infante, and C. Gauntt for helpful discussions and R. Salinas for technical help in the flow cytometric analysis.

This study was supported by Public Health Service grants HL60604 and CA096512 from the National Institutes of Health to S.-J.G.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arvanitakis, L., E. Geras-Raaka, A. Varma, M. C. Gershengorn, and E. Cesarman. 1997. Human herpesvirus KSHV encodes a constitutively active G-protein-coupled receptor linked to cell proliferation. Nature 385:347-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvanitakis, L., E. A. Mesri, R. G. Nador, J. W. Said, A. S. Asch, D. M. Knowles, and E. Cesarman. 1996. Establishment and characterization of a primary effusion (body cavity-based) lymphoma cell line (BC-3) harboring Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) in the absence of Epstein-Barr virus. Blood 88:2648-2654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aziz, D. C., Z. Hanna, and P. Jolicoeur. 1989. Severe immunodeficiency disease induced by a defective murine leukaemia virus. Nature 338:505-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bais, C., B. Santomasso, O. Coso, L. Arvanitakis, E. G. Raaka, J. S. Gutkind, A. S. Asch, E. Cesarman, and E. A. Mesri. 1998. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature 391:86-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballestas, M. E., and K. M. Kaye. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 mediates episome persistence through cis-acting terminal repeat (TR) sequence and specifically binds TR DNA. J. Virol. 75:3250-3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barozzi, P., M. Luppi, F. Facchetti, C. Mecucci, M. Alu, R. Sarid, V. Rasini, L. Ravazzini, E. Rossi, S. Festa, B. Crescenzi, D. G. Wolf, T. F. Schulz, and G. Torelli. 2003. Post-transplant Kaposi's sarcoma originates from the seeding of donor-derived progenitors. Nat. Med. 9:554-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkower, A. S., F. Lilly, and R. Soeiro. 1980. Expression of viral RNA in Friend virus-induced erythroleukemia cells. Cell 19:637-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berneman, Z. N., D. V. Ablashi, G. Li, M. Eger-Fletcher, M. S. Reitz, Jr., C. L. Hung, I. Brus, A. L. Komaroff, and R. C. Gallo. 1992. Human herpesvirus 7 is a T-lymphotropic virus and is related to, but significantly different from, human herpesvirus 6 and human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10552-10556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blasig, C., C. Zietz, B. Haar, F. Neipel, S. Esser, N. H. Brockmeyer, E. Tschachler, S. Colombini, B. Ensoli, and M. Sturzl. 1997. Monocytes in Kaposi's sarcoma lesions are productively infected by human herpesvirus 8. J. Virol. 71:7963-7968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boshoff, C., Y. Endo, P. D. Collins, Y. Takeuchi, J. D. Reeves, V. L. Schweickart, M. A. Siani, T. Sasaki, T. J. Williams, P. W. Gray, P. S. Moore, Y. Chang, and R. W. Weiss. 1997. Angiogenic and HIV-inhibitory functions of KSHV-encoded chemokines. Science 278:290-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boshoff, C., S.-J. Gao, L. E. Healy, S. Matthews, A. J. Thomas, R. A. Warnke, J. A. Strauchen, E. Matutes, R. A. Weiss, P. S. Moore, O. W. Kamel, and Y. Chang. 1998. Establishing a KSHV+ cell line (BCP-1) from peripheral blood and characterizing its growth in Nod/SCID mice. Blood 91:1671-1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell, D. E., M. C. Kemp, M. L. Perdue, C. C. Randall, and G. A. Gentry. 1976. Equine herpesvirus in vivo: cyclic production of a DNA density variant with repetitive sequences. Virology 69:737-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannon, J. S., J. Nicholas, J. M. Orenstein, R. B. Mann, P. G. Murray, P. J. Browning, J. A. DiGiuseppe, E. Cesarman, G. S. Hayward, and R. F. Ambinder. 1999. Heterogeneity of viral IL-6 expression in HHV-8-associated diseases. J. Infect. Dis. 180:824-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cesarman, E., P. S. Moore, P. H. Rao, G. Inghirami, D. M. Knowles, and Y. Chang. 1995. In vitro establishment and characterization of two AIDS-related lymphoma cell lines containing Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood 86:2708-2714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dauenhauer, S. A., R. A. Robinson, and D. J. O'Callaghan. 1982. Chronic production of defective-interfering particles by hamster embryo cultures of herpesvirus persistently infected and oncogenically transformed cells. J. Gen. Virol. 60:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis, M. A., M. Sturzl, C. Blasig, A. Schreier, H.-G. Guo, M. Reitz, S. R. Opalenik, and P. J. Browning. 1997. Expression of human herpesvirus 8-encoded cyclin D in Kaposi's sarcoma spindle cells. J. Nat. Can. Inst. 89:1868-1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demmler, G. J., G. J. Buffone, C. M. Schimbor, and R. A. May. 1988. Detection of cytomegalovirus in urine from newborns by using polymerase chain reaction DNA amplification. J. Infect. Dis. 158:1177-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dupin, N., C. Fisher, P. Kellam, S. Ariad, M. Tulliez, N. Franck, E. van Marck, D. Salmon, I. Gorin, J. P. Escande, R. A. Weiss, K. Alitalo, and C. Boshoff. 1999. Distribution of human herpesvirus-8 latently infected cells in Kaposi's sarcoma, multicentric Castleman's disease, and primary effusion lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4546-4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleckenstein, B., G. W. Bornkamm, and H. Ludwig. 1975. Repetitive sequences in complete and defective genomes of herpesvirus saimiri. J. Virol. 15:398-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frenkel, N. 1981. Defective interfering herpesviruses, p. 91-120. In A. J. Nahmias, W. R. Dowdle, and R. F. Schinzai (ed.), The human herpesviruses: an interdisciplinary perspective. Elsevier-North Holland, New York, N.Y. p. 91-120.

- 21.Frenkel, N., H. Locker, and D. A. Vlazny. 1980. Studies of defective herpes simplex viruses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 354:347-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao, S.-J., C. Boshoff, S. Jayachandra, R. A. Weiss, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1997. KSHV ORF K9 (vIRF) is an oncogene which inhibits the interferon signaling pathway. Oncogene 15:1979-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao, S.-J., L. Kingsley, D. R. Hoover, T. J. Spira, C. R. Rinaldo, A. Saah, J. Phair, R. Detels, P. Parry, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. Seroconversion of antibodies against Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi's sarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 335:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao, S.-J., L. Kingsley, M. Li, W. Zheng, C. Parravicini, J. Ziegler, R. Newton, C. R. Rinaldo, A. Saah, J. Phair, R. Detels, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. KSHV antibodies among Americans, Italians, and Ugandans with and without Kaposi's sarcoma. Nat. Med. 2:925-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao, S.-J., Y.-J. Zhang, J.-H. Deng, C. S. Rabkin, O. Flore, and H. B. Jenson. 1999. Molecular polymorphism of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) latent nuclear antigen: evidence for a large repertoire of viral genotypes and dual infection with different viral genotypes. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1466-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao, S. J., J. H. Deng, and F. C. Zhou. 2003. Productive lytic replication of a recombinant Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in efficient primary infection of primary human endothelial cells. J. Virol. 77:9738-9749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorczyca, W., J. Gong, B. Ardelt, F. Traganos, and Z. Darzynkiewicz. 1993. The cell cycle related differences in susceptibility of HL-60 cells to apoptosis induced by various antitumor agents. Cancer Res. 53:3186-3192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregory, C. D., C. Dive, S. Henderson, C. A. Smith, G. T. Williams, J. Gordon, and A. B. Rickinson. 1991. Activation of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes protects human B cells from death by apoptosis. Nature 349:612-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruffat, H., S. Portes-Sentis, A. Sergeant, and E. Manet. 1999. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus-8) encodes a homologue of the Epstein-Barr virus bZIP protein EB1. J. Gen. Virol. 80:557-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartley, J. W., and W. P. Rowe. 1966. Production of altered cell foci in tissue culture by defective Moloney sarcoma virus particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 55:780-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang, A. S., and D. Baltimore. 1970. Defective viral particles and viral disease processes. Nature 226:325-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang, M., C. Simard, and P. Jolicoeur. 1989. Immunodeficiency and clonal growth of target cells induced by helper-free defective retrovirus. Science 246:1614-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inoue, Y., M. Yasukawa, and S. Fujita. 1997. Induction of T-cell apoptosis by human herpesvirus 6. J. Virol. 71:3751-3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawanishi, M. 1993. Epstein-Barr virus induces fragmentation of chromosomal DNA during lytic infection. J. Virol. 67:7654-7658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kieff, E., and T. Shenk. 1998. Modulation of apoptosis by herpesviruses. Semin. Virol. 8:471-480. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirshner, J. R., K. Staskus, A. Haase, M. Lagunoff, and D. Ganem. 1999. Expression of the open reading frame 74 (G-protein-coupled receptor) gene of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus: implications for KS pathogenesis. J. Virol. 73:6006-6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lebbe, C., P. de Cremoux, G. Millot, M. P. Podgorniak, O. Verola, R. Berger, P. Morel, and F. Calvo. 1997. Characterization of in vitro culture of HIV-negative Kaposi's sarcoma-derived cells. In vitro responses to alfa interferon. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 289:421-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, H., J. Guo, M. Li, J. K. Choi, M. DeMaria, M. Rosenzweig, and J. U. Jung. 1998. Identification of an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif of K1 transforming protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5219-5228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin, J. C., S. C. Lin, B. K. De, W. P. Chan, and B. L. Evatt. 1993. Precision of genotyping of Epstein-Barr virus by polymerase chain reaction using three gene loci (EBNA-2, EBNA-3C and EBER): predominance of type A virus associated with Hodgkin's disease. Blood 81:3372-3381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin, S. F., D. R. Robinson, G. Miller, and H. J. Kung. 1999. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes a bZIP protein with homology to BZLF1 of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 73:1909-1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linderoth, J., E. Rambech, and M. Dictor. 1999. Dominant human herpesvirus type 8 RNA transcripts in classical and AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Pathol. 187:582-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lukac, D. M., J. R. Kirshner, and D. Ganem. 1999. Transcriptional activation by the product of open reading frame 50 of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for lytic viral reactivation in B cells. J. Virol. 73:9348-9361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukac, D. M., R. Renne, J. R. Kirshner, and D. Ganem. 1998. Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection from latency by expression of the ORF 50 transactivator, a homolog of the EBV R protein. Virology 252:304-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller, G., L. Heston, E. Grogan, L. Gradoville, M. Rigsby, R. Sun, D. Shedd, V. M. Kusharyov, S. Grossberg, and Y. Chang. 1997. Selective switch between latency and lytic replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and Epstein-Barr virus in dually infected body cavity lymphoma cells. J. Virol. 71:314-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore, P. S., C. Boshoff, R. A. Weiss, and Y. Chang. 1996. Molecular mimicry of human cytokine and cytokine response pathway genes by KSHV. Science 274:1739-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore, P. S., and Y. Chang. 1998. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded oncogenes and oncogenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 23:65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore, P. S., and Y. Chang. 2001. Molecular virology of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356:499-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore, P. S., S.-J. Gao, G. Dominguez, E. Cesarman, O. Lungu, D. M. Knowles, R. Garber, D. J. McGeoch, P. Pellett, and Y. Chang. 1996. Primary characterization of a herpesvirus-like agent associated with Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Virol. 70:549-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neel, B. G., L. H. Wang, B. Mathey-Prevot, T. Hanafusa, H. Hanafusa, and W. S. Hayward. 1982. Isolation of 16L virus: a rapidly transforming sarcoma virus from an avian leukosis virus-induced sarcoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:5088-5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicholas, J., J.-C. Zong, D. J. Alcendor, D. M. Ciufo, L. J. Poole, R. T. Sarisky, C. J. Chiou, X.-Q. Zhang, X.-Y. Wan, H.-G. Guo, M. S. Reitz, and G. S. Hayward. 1998. Novel organizational features, captured cellular genes, and strain variability within the genome of KSHV/HHV8. J. Int. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 23:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orenstein, J. M., S. Alkan, A. Blauvelt, K. T. Jeang, M. D. Weinstein, D. Ganem, and B. Herndier. 1997. Visualization of human herpesvirus type 8 in Kaposi's sarcoma by light and transmission electron microscopy. AIDS 11:F35-F45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parks, W. P., E. S. Hubbell, R. J. Goldberg, F. J. O'Neill, and E. M. Scolnick. 1976. High frequency variation in mammary tumor virus expression in cell culture. Cell 8:87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parravicini, C., M. Corbellino, M. Paulli, U. Magrini, M. Lazzarino, P. S. Moore, and Y. Chang. 1997. Expression of a virus-derived cytokine, KSHV vIL-6, in HIV-seronegative Castleman's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 151:1517-1522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rainbow, L., G. M. Platt, G. R. Simpson, R. Sarid, S.-J. Gao, H. Stoiber, C. S. Herrington, P. S. Moore, and T. F. Schulz. 1997. The 222- to 234-kilodalton latent nuclear protein (LNA) of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) is encoded by orf73 and is a component of the latency-associated nuclear antigen. J. Virol. 71:5915-5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reed, J. A., R. G. Nador, D. Spaulding, Y. Tani, E. Cesarman, and D. M. Knowles. 1998. Demonstration of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cyclin D homolog in cutaneous Kaposi's sarcoma by colorimetric in situ hybridization using a catalyzed signal amplification system. Blood 91:3825-3832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renne, R., W. Zhong, B. Herndier, M. McGrath, N. Abbey, D. Kedes, and D. Ganem. 1996. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat. Med. 2:342-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Revoltella, R., L. Bertolini, and C. Friend. 1979. In vitro transformation of mouse bone marrow cells by the polycythemic strain of Friend leukemia virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1464-1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robinson, R. A., B. E. Henry, R. G. Duff, and D. J. O'Callaghan. 1980. Oncogenic transformation by equine herpesviruses (EHV). I. Properties of hamster embryo cells transformed by ultraviolet-irradiated EHV-1. Virology 101:335-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson, R. A., R. B. Vance, and D. J. O'Callaghan. 1980. Oncogenic transformation by equine herpesviruses. II. Coestablishment of persistent infection and oncogenic transformation of hamster embryo cells by equine herpesvirus type 1 preparations enriched for defective interfering particles. J. Virol. 36:204-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roizman, B., R. J. Whitley, and C. Lopez. 1993. The human herpesviruses. Raven Press, Ltd., New York, N.Y.

- 61.Russo, J. J., R. A. Bohenzky, M. Chien, K. Chen, D. Maddalena, M. Yan, J. P. Parry, D. Peruzzi, I. S. Edelman, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. Nucleotide sequence of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14862-14867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarid, R., T. Sato, R. Bohenzky, J. Russo, and Y. Chang. 1997. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) encodes a functional bcl-2 homolog. Nat. Med. 3:293-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schroder, C. H., H. C. Kaerner, K. Munk, and G. Darai. 1977. Morphological transformation of rat embryonic fibroblasts by abortive herpes simplex virus infection: increased transformation rate correlated to a defective viral genotype. Intervirology 8:164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Serfling, U., N. S. Penneys, W. Y. Zhu, M. Sisto, and C. Leonardi. 1993. Varicella-zoster virus DNA in granulomatous skin lesions following herpes zoster: a study by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Cutan. Pathol. 20:28-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shields, A., W. N. Witte, E. Rothenberg, and D. Baltimore. 1978. High frequency of aberrant expression of Moloney murine leukemia virus in clonal infections. Cell 14:601-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Speck, S. H., T. Chatila, and E. Flemington. 1997. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus: regulation and function of the BZLF1 gene. Trends Microbiol. 5:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Staal, S. P., J. W. Hartley, and W. P. Rowe. 1977. Isolation of transforming murine leukemia viruses from mice with a high incidence of spontaneous lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:3065-3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Staskus, K. A., R. Sun, G. Miller, P. Racz, A. Jaslowski, C. Metroka, H. Brett-Smith, and A. T. Haase. 1999. Cellular tropism and viral interleukin-6 expression distinguish human herpesvirus 8 involvement in Kaposi's sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman's disease. J. Virol. 73:4181-4187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Staskus, K. A., W. D. Zhong, K. Gebhard, B. Herndier, H. Wang, R. Renne, J. Beneke, J. Pudney, D. J. Anderson, D. Ganem, and A. T. Haase. 1997. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression in endothelial (spindle) tumor cells. J. Virol. 71:715-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stürzl, M., G. Ascherl, C. Blasig, S. R. Opalenik, B. Ensoli, and P. J. Browning. 1998. Expression of the human herpesvirus 8-encoded viral macrophage inflammatory protein-1 gene in Kaposi's sarcoma lesions. AIDS 12:1105-1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stürzl, M., C. Blasig, A. Schreier, F. Neipel, C. Hohenadl, E. Cornali, G. Ascherl, S. Esser, N. H. Brockmeyer, M. Ekman, E. E. Kaaya, E. Tschachler, and P. Biberfeld. 1997. Expression of HHV-8 latency-associated T0.7 RNA in spindle cells and endothelial cells of AIDS-associated, classical and African Kaposi's sarcoma. Int. J. Cancer 72:68-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stürzl, M., C. Hohenadl, C. Zietz, E. Castanos-Velez, A. Wunderlich, G. Ascherl, P. Biberfeld, P. Monini, P. J. Browning, and B. Ensoli. 1999. Expression of K13/v-FLIP gene of human herpesvirus 8 and apoptosis in Kaposi's sarcoma spindle cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91:1725-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sun, R., S. F. Lin, L. Gradioville, Y. Yuan, F. Zhu, and G. Miller. 1998. A viral gene that activates lytic cycle expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:10866-10871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teruya-Feldstein, J., P. Zauber, J. E. Setsuda, E. L. Berman, L. Sorbara, M. Raffeld, G. Tosato, and E. S. Jaffe. 1998. Expression of human herpesvirus-8 oncogene and cytokine homologues in an HIV-seronegative patient with multicentric Castleman's disease and primary effusion lymphoma. Lab. Investig. 78:1637-1642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wagner, E. K., and D. C. Bloom. 1997. Experimental investigation of herpes simplex virus latency. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:419-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang, Y. C., Q. Zhang, and E. A. Montalvo. 1998. Purification of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) and analyses of the structural proteins. J. Virol. Methods 73:219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamamoto, Y., C. L. Gamble, S. P. Clark, A. Joyner, T. Shibuya, M. E. MacDonald, D. Mager, A. Bernstein, and T. W. Mak. 1981. Clonal analysis of early and late stages of erythroleukemia induced by molecular clones of integrated spleen focus-forming virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:6893-6897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu, Y., J. B. Black, C. S. Goldsmith, P. J. Browning, K. Bhalla, and M. K. Offermann. 1999. Induction of human herpesvirus-8 DNA replication and transcription by butyrate and TPA in BCBL-1 cells. J. Gen. Virol. 80:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang, L., S. Nikkari, M. Skurnik, T. Ziegler, R. Luukkainen, T. Mottonen, and P. Toivanen. 1993. Detection of herpesviruses by polymerase chain reaction in lymphocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 36:1080-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhong, W., H. Wang, B. Herndier, and D. Ganem. 1996. Restricted expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genes in Kaposi's sarcoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6641-6646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou, F. C., Y. J. Zhang, J. H. Deng, X. P. Wang, H. Y. Pan, E. Hettler, and S. J. Gao. 2002. Efficient infection by a recombinant Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cloned in a bacterial artificial chromosome: application for genetic analysis. J. Virol. 76:6185-6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhu, F. X., T. Cusano, and Y. Yuan. 1999. Identification of the immediate-early transcripts of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 73:5556-5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zoeteweij, J. P., S. T. Eyes, J. M. Orenstein, T. Kawamura, L. Wu, B. Chandran, B. Forghani, and A. Blauvelt. 1999. Identification and rapid quantification of early- and late-lytic human herpesvirus 8 infection in single cells by flow cytometric analysis: characterization of antiherpesvirus agents. J. Virol. 73:5894-5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]