Abstract

The concept that proteins exist in numerous different conformations or conformational substates, described by an energy landscape, is now accepted, but the dynamics is incompletely explored. We have previously shown that large-scale protein motions, such as the exit of a ligand from the protein interior, follow the dielectric fluctuations in the bulk solvent. Here, we demonstrate, by using mean-square displacements (msd) from Mössbauer and neutron-scattering experiments, that fluctuations in the hydration shell control fast fluctuations in the protein. We call the first type solvent-slaved or α-fluctuations and the second type hydration-shell-coupled or β-fluctuations. Solvent-slaved motions are similar to the α-fluctuations in glasses. Their temperature dependence can be approximated by a Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher relation and they are absent in a solid environment. Hydration-shell-coupled fluctuations are similar to the β-relaxation in glasses. They can be approximated by a Ferry or an Arrhenius relation, are much reduced or absent in dehydrated proteins, and occur in hydrated proteins even if embedded in a solid. They can be responsible for internal processes such as the migration of ligands within myoglobin. The existence of two functionally important fluctuations in proteins, one slaved to bulk motions and the other coupled to hydration-shell fluctuations, implies that the environment can control protein functions through different avenues and that no real protein transition occurs at ≈200 K. The large number of conformational substates is essential; proteins cannot function without this reservoir of entropy, which resides mainly in the hydration shell.

Proteins are the molecules that perform most biological functions, from storage of dioxygen (O2) to enzyme catalysis. A central goal of protein science is to relate structure, dynamics, and function. Although investigations of protein structures and functions are well organized industries, protein dynamics is still in its infancy. Dynamics studies are best performed on proteins whose structures and functions are well known, e.g., myoglobin (Mb), the protein that gives muscles their red color. A hybrid picture of Mb is shown in Fig. 1. The lower part displays a piece of the protein backbone, namely, three α-helices. The upper part presents a space-filling view of the protein atoms. The active center, a heme group with a central iron atom, is red. Two cavities are also shown, Xe1 and the heme cavity. The protein is surrounded by the hydration shell, one to two layers of water, and is embedded in the bulk solvent. In Mb's role as an oxygen-storage protein, O2 enters the protein, stays some time in Xe1, then binds at the heme iron (1). CO follows a similar path through the protein. The structure of Mb shows no permanent channel that leads from the outside to either Xe1 or the heme pocket or from Xe1 to the heme pocket. Thus, structural fluctuations are necessary for function (2).

Fig. 1.

A stylized look into Mb displays the parts of the protein that are involved in protein dynamics and function. The lower half of the structure shows three α-helices, part of the protein backbone, with one side chain as an example. The upper half provides a space-filling view. Between the two halves is a heme group (in red). Hydration waters are shown as red-and-white spheres. Two cavities that can hold ligands are also depicted. The hydration shell and the bulk solvent envelop the protein and dominate protein dynamics.

Fluctuations imply that Mb possesses numerous different conformations, called conformational substates (CS) (3). The different CS can be described by an energy landscape (EL) (4), the central concept in the folding (5), dynamics, and function of proteins. The EL is a construct in ≈3N dimensions, where N is the number of atoms forming the protein and the hydration shell. A substate is a point in this hyperspace, and structural fluctuations are represented by jumps between points. Initially, we assumed that protein conformations could be organized into a simple, rough EL (1). Experiments showed, however, that there are wells within wells within wells, and an organization of the EL with several tiers of decreasing free-energy barriers ensued (6). The top tier, denoted by CS0, contains a small number of CS with different structures that can have different functions: in A0 Mb is involved in NO enzymatics; in A1 it acts as an oxygen-storage system (7). Each of the CS0 substates can assume a very large number of CS1, called statistical substates. They perform the same function but with different rates. Here, we will show that the statistical substates comprise two tiers, CS1α and CS1β. Fluctuations between CS1α substates are slaved to the solvent motions and involve sizeable structural changes (8). Fluctuations between CS1β substates parallel the fluctuations in the protein's hydration shell but are essentially independent of the fluctuations in the bulk solvent. They involve mainly amino acid side chains and the hydrogen-bond network in the hydration shell.

The Conformational Mean-Square Displacement

The experimental exploration of protein function and dynamics is performed by measuring the time and temperature dependences of selected observables (6). Here, we use the mean-square displacement (msd), 〈x2(T)〉, of the protein atoms.§ In solids, atoms vibrate about their equilibrium positions and rarely move interatomic distances, and the 〈x2(T)〉 is small. In proteins conformational motions can produce larger msd. The time and temperature dependences of 〈x2(T)〉 thus can provide information about protein motions. We describe our approach by using the Mössbauer effect (9-11), in which a nuclear level with energy E0 and mean life τ emits a gamma ray. The fraction of gamma rays that receive the full energy E0 and suffer neither a recoil energy loss nor a Doppler broadening is given by the Lamb-Mössbauer factor

|

1 |

The msd is measured along the wave vector k0 of the gamma rays. The magnitude of k0 is given by k0 = E0/[hcrossed]c; f(T) and E0 together thus yield 〈x2(T)〉. The favorite isotope for biological studies is 57Fe, with a mean life τ = 140 ns, E0 = 14.4 keV, and  Å-2. Fig. 2A shows 〈x2(T)〉 as found for 57Fe embedded in a Mb crystal (9). To evaluate the data, we note that 〈x2(T)〉 consists of a vibrational and a conformational component (3),

Å-2. Fig. 2A shows 〈x2(T)〉 as found for 57Fe embedded in a Mb crystal (9). To evaluate the data, we note that 〈x2(T)〉 consists of a vibrational and a conformational component (3),

|

2 |

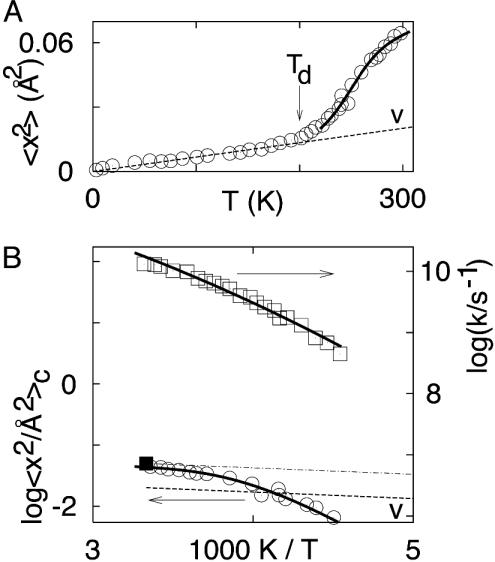

Fig. 2.

Mössbauer scattering compared with hydration shell dielectric beta process. (A) The msd of 57Fe in a Mb crystal, measured by Mössbauer spectroscopy [according to Parak et al. (9)]. The dashed line, denoted by V, is the vibrational contribution to 〈x2(T)〉; it is also plotted in B. (B) The rectangles (right y axis) give the rate coefficient kβ(T) for the dielectric relaxation of the hydration water in a metmyoglobin crystal (27). The circles (left y axis) are 〈x2(T)〉c for 57Fe in a deoxymyoglobin crystal (9). The solid square at 300 K gives the 〈x2(T)〉c as measured by x-ray diffraction (28-30). The dotted line is the extrapolation of the x-ray value to low temperatures.

Below 200 K, 〈x2(T)〉 is dominated by vibrations and thus, apart from zero-point motions, is proportional to T. The deviation from linearity above 200 K in hydrated proteins is due to activated transitions between CS that give rise to 〈x2(T)〉c = 〈x2(T)〉 - 〈x2(T)〉v. To obtain 〈x2(T)〉c we extrapolate 〈x2(T)〉 linearly from 10 K to 170 K and subtract the extrapolated from the measured value above 200 K. The data so obtained are redrawn in Fig. 2B as log〈x2(T)〉c versus 1,000 K/T. 〈x2(T)〉c approximately follows an Arrhenius relation, thus implying that it is caused by thermally activated fluctuations with a rate coefficient kc(T). Similar deviations from the linear vibrational low-temperature behavior are also seen by other techniques, such as elastic neutron scattering and vibrational echo experiments. The different experimental techniques are characterized by rate coefficients km; crudely speaking, they see mainly motions that are faster than km. For Mössbauer experiments on 57Fe, km is given by 1/τ, where τ is the mean life of the decaying state, 140 ns. For the elastic neutron-scattering experiments, km is determined by the energy resolution Γ through the Heisenberg uncertainty relation as km = Γ/[hcrossed]. In practice, km for neutrons ranges from 109 s-1 to 1011 s-1.

Protein Fluctuations and the msd

To study the fluctuations that are responsible for 〈x2(T)〉c we relate their rate, kc(T), to their msd, 〈x2(T)〉c. A minimal model to establish this connection consists of two equal-energy wells (12, 13). Parak (11) has pointed out, however, that a two-well model is insufficient to describe protein motions, because many substates are involved. They analyze the Mössbauer line shape by using the Langevin equation to describe the iron motions as a series of infinitesimal steps (11, 14-17). Here, we assume that the conformational motions of the protein cause the 57Fe atom sitting at the center of the heme group in Mb to make a random walk among CS with steps of size s at the rate kc(T). During the time τ = 1/km, the iron atom makes n = kc(T) τ = kc(T)/km steps and travels a total distance (kc(T)/km) s. Because the walk is random, the iron atom explores a region of size

|

3 |

if the region is not bounded. This case applies at low temperatures, say below 250 K, where the 57Fe atom visits only a part of the available CS. At higher temperatures, however, the 57Fe atom explores essentially the entire conformational space accessible to it and Eq. 3 is no longer valid. Two limiting situations are easy to describe for the bounded case. If the random walk takes place in a square well, the msd will converge to a temperature-independent value. If, on the other hand, the confining potential can be approximated by a harmonic potential, V(x) = ½ bx2, the msd is given by (18)

|

4 |

Before discussing the data in Fig. 2 further, we make a few remarks about proteins and glasses. Despite their different constructions, they have similar properties (19). They are inhomogeneous, governed by an EL (4, 20), and exhibit two types of fluctuations, α and β, also called primary and secondary relaxation processes (21-23), with rate coefficients kα(T) and kβ(T). Both also show relaxation phenomena at liquid helium temperatures (24). kα(T) can be approximated by a Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher relation,

|

5 |

kβ(T) is usually described by an Arrhenius relation, kβ(T) = A exp{-H/kBT}, but a Ferry relation (25),

|

6 |

changing to an Arrhenius law at low T, has also been suggested (26). A, E, and T0 are parameters to be determined experimentally. Over a broad range of temperature, the β-fluctuations are much faster than the α-fluctuations. The two can be distinguished in an Arrhenius plot. Consider 3:1 glycerol/water, the glass-forming solvent often used in protein studies (1). Approximating kα(T) with an Arrhenius relation yields H ≈ 65 kJ/mol, log(A/s-1) ≈ 20 at 250 K, and H ≈ 110 kJ/mol, log(A/s-1) ≈ 35 at 200 K, whereas typical values for kβ(T) are H ≈ 10-30 kJ/mol, log (A/s-1) ≈14-15 at both temperatures.

Armed with this information, we continue the search for the fluctuations that are responsible for 〈x2(T)〉c in Fig. 2B. The clue comes from a measurement of the dielectric relaxation in an Mb crystal by Singh et al. (27), also shown in Fig. 2B. This measurement is dominated by hydration-shell water. An Arrhenius fit to the rate coefficient at 250 K gives H ≈ 30 kJ/mol and log(A/s-1) ≈ 16, values typical for the β-relaxation. We therefore label the relaxation kβ(T). A comparison of kβ(T) with 〈x2(T)〉c shows two different temperatures regimes. Above ≈250 K 〈x2(T)〉c is proportional to T. Eq. 4 suggests that the iron atom now explores the entire accessible conformation space during the Mössbauer lifetime of 140 ns. This conclusion is supported by a comparison of 〈x2(T)〉c measured by the Mössbauer effect with the value obtained in x-ray and neutron diffraction experiments (28-30). At 300 K, the Mössbauer experiment yields 〈x2(T)〉c ≈ 0.04 Å2. In x-ray diffraction, the msd is an equilibrium property; it characterizes all CS that the iron atom can populate. At 300 K, the conformational msd seen by the x-rays and by neutrons is ≈0.05 Å2 (28-30), indicated in Fig. 2 by the filled square. With Eq. 4, the value 〈x2(T)〉c ≈ 0.04 Å2 gives b ≈ 60 kJ/mol Å2.

Below ≈250 K, 〈x2(T)〉c and kβ(T) have essentially the same temperature dependence, implying that the dielectric fluctuations in the hydration water and the conformational motions sensed by the 57Fe are coupled and that Eq. 3 holds. We assume that only a fraction ε of the transitions in the hydration shell cause the iron atom to move so that the observed fluctuations are given by kc(T) = ε kβ(T). Eq. 3 then gives for the msd seen by the iron atom 〈x2(T)〉c = ε (kβ/km) s2. The Mössbauer data permit the determination of the product εs2 but not of the individual factors. We can distinguish two extreme cases. If ε = 1, the data in Fig. 2B give a step size s ≈ 0.009 Å. If, on the other hand, we assume a two-well model, with s2 ≈ 〈x2(300 K)〉c, we get ε ≈ 0.002. Neither of these two limiting cases is realistic, but additional experiments and computations are needed to separate ε and s.

The β-Relaxation in Proteins

The Mössbauer experiment is just one example proving the existence of the β-relaxation in proteins. Neutron-scattering (31-34) and vibrational echo (35) data also support this conclusion. Although Mössbauer experiments are restricted to a few proteins, neutrons can be used on essentially all proteins. On the other hand, whereas the Mössbauer experiments look at one well defined atom within the protein, neutrons see mainly the hydrogen atoms that are widely distributed and hence yield averages that are not always meaningful (30). Of the large number of relevant published data we select three examples. They are given in Fig. 3, on the left side as published, namely, 〈x2(T)〉 vs. T, and, on the right side, as log〈x2(T)〉c vs. 1,000 K/T. Fig. 3 A and B displays 〈x2(T)〉 as determined by elastic neutron scattering with log(km/s-1) ≈ 10 from hydrated and dehydrated bacteriorhopsin (33). Fig. 3 C and D presents neutron-scattering data from lysozyme, with log(km/s-1) ≈ 9 (34). Fig. 3 E and F shows data from an IR echo experiment on Mb (35). The data in Figs. 2 and 3, measured on several proteins with four separate techniques, are all dominated by β-relaxations and demonstrate the predominant role of hydration water.

Fig. 3.

Hydration shell fluctuation is essential for protein β relaxation. (Left) The observables are plotted linearly versus temperature. (Right) The logarithms of the conformational components of the observables are redrawn vs. 1,000 K/T. (A and B) Mean-square displacement, 〈x2(T)〉, of the hydrogens in bacteriorhodopsin at 2 wt% hydration (open squares) and 35 wt% hydration (circles), as measured by neutron scattering with log(km/s-1) ≈ 10. [according to Ferrand et al. (33)]. (C and D) msd for lysozyme in various solvents (70% lysozyme/30% water; 50% glycerol/50% lysozyme; 80% glycerol/20% lysozyme and dry lysozyme), measured by neutron scattering, with log(km/s-1) ≈ 9 [from Tsai et al. (34)]. (E and F) Pure dephasing rate versus T in IR vibrational echo experiments with Mb in three different solvents (trehalose, 95% glycerol/5% water, 50% ethylene glycol/50% water. [From Rector et al. (35).]

Fig. 3 shows that the conventional plots, 〈x2(T)〉 vs. T, are hard to interpret, whereas the plots of log〈x2(T)〉c vs. 1,000 K/T show that the conformational msd can be approximated over a broad range of temperature by Arrhenius or Ferry relations. The Arrhenius behavior together with the values of the activation enthalpies, ≈20 kJ/mol for hydrated bacteriorhodopsin and lysozyme and ≈12 kJ/mol for hydrated Mb, shows that these are β-relaxations, as noted earlier by Doster et al. (31). However, evidence of the α-relaxation does not exist. In dehydrated samples, all conformational motions are absent, whereas in hydrated proteins the β-fluctuations are present even in a rigid environment such as solid trehalose. The β-fluctuations are consequently independent of the α-fluctuations in the bulk solvent, at least at temperatures below ≈280 K. This observation, together with the result from the Mössbauer experiment discussed above, demonstrates that the β-fluctuations in the protein are linked to the β-fluctuations in the hydration shell. The msd for a given protein in different environments display essentially the same slopes, but are shifted in amplitude, implying that the hydration level and the cosolvents affect mainly the entropy in the hydration shell, and not the enthalpy barrier to conformational motion. To determine the average step size s for the motions seen by neutrons, we need to know the relevant rate coefficient kβ(T) in the respective solvents. We have not found such data. Some information comes from a neutron-scattering study on lysozyme embedded in pure glycerol (36) that showed that 〈x2(T)c〉 for the glycerol and for the embedded lysozyme are identical. This result implies that the hydrogen atoms in the protein see the full motions of molecules in the shell and also suggests that glycerol can replace water. Many proteins not discussed in Figs. 2 and 3 also exhibit hydration-shell-coupled motions. Such motions dominate, for instance, the response of photosynthetic reaction center proteins to internal charge separation, where the sensitivity to hydration has been quantified (37-39). “Hydration shell” in this case likely refers to buried water.

Fluctuations and Function in Mb

How do β-fluctuations relate to protein function? Before proposing an answer, we describe three different classes of processes in proteins: Class I, solvent-slaved processes follow the dielectric (α) fluctuations in the bulk solvent (8); they are absent in rigid environments and in dehydrated proteins (40). Class II, hydration-shell-coupled processes follow the β-fluctuations in the hydration shell; they are absent in dehydrated proteins. Class III, vibrational (nonslaved) processes are independent of the fluctuations in the solvent and the hydration shell. Each class controls a different aspect of the binding of small ligands such as CO or O2 to Mb. We still do not have a complete understanding of binding, but crucial features have become clear through a combination of kinetic (1, 41) and x-ray studies (42-44). A CO, after entering Mb, spends some time in the pocket denoted as Xe1 in Fig. 1, migrates to the heme cavity, and ultimately forms a covalent bond to the heme iron. In Fig. 4, the rate coefficients for the elementary steps are compared with the rate coefficients for the three classes of fluctuations. kα(T) characterizes the α-fluctuations in the bulk solvent, here a 3:1 glycerol/water solvent (45). kβ(T), the rate coefficient of the β-fluctuations in the hydration water in a Mb crystal, has been measured between 220 and 300 K (27); it can be fit with the Ferry relation, Eq. 6, between 220 and 300 K, giving EF = 4.9 kJ/mol, log(AF/s-1) = 12. To extrapolate kβ(T) below 220 K, we can either continue with the Ferry expression or use the Arrhenius form. The data below 250 K suggest the latter and they yield the Arrhenius parameters H ≈ 34 kJ/mol and log (A/s-1) ≈ 16.8, values typical for the β-relaxation in glasses. The extrapolation is shown as a dashed line in Fig. 4. An extrapolation with the Ferry relation does not differ significantly. The validity of the extrapolation is supported by a measurement of the β-fluctuations in a 1D hydration layer on clay, which shows an Arrhenius behavior between 130 and 210 K, with H ≈ 38 kJ/mol, log(A/s-1) ≈ 14 (46).

Fig. 4.

Temperature dependence of rate coefficients for fluctuations and processes in Mb. Solvent: 3:1 glycerol/water, except for kβ(T), which was measured in a metMb crystal. Solid lines indicate measured values, dashed lines are extrapolations. α denotes the rate coefficient kα(T) for the solvent dielectric relaxation; β denotes the rate coefficient kβ(T). Exit is the rate coefficient for the exit of CO from Mb. DA denotes the rate coefficient kDA for the passage of CO from the Xe1 cavity to the bound state at the heme iron. kexit is parallel to kα(T). DA parallels β.

Rate coefficients for the three elementary protein processes are also shown in Fig. 4. kexit(T), describing the exit of CO from Mb, follows kα(T) over many orders of magnitude in rate but is slower by a temperature-independent factor of ≈105. The slowing is caused by entropy: Opening the gate for the exit or entry of a ligand is not a one-step process such as opening a solid door but is the result of numerous small steps, each given approximately by kα(T) (8). The transit from Xe1 (D) to the bound state at the heme iron (A) proceeds with essentially the same rate in different solvents (41), occurs even if the solvent is solid (1), but is absent in dehydrated Mb (47). Moreover, the paths D→A are complex (48) and involve several steps, most likely caused by buried alternate conformations (49). If different steps had different enthalpy barriers, kDA(T) would not have the smooth temperature dependence shown in Fig. 4. These observations imply that migration through the protein is enabled by internal β-fluctuations that are coupled to the β-fluctuations in the hydration shell. This connection is supported by a comparison of kDA(T) and kβ(T): kDA(T) and the extrapolated kβ(T) are essentially parallel from above 250 to 130 K. The fact that kDA(T) is much slower than kβ(T) implies entropy control: Only a small fraction of the fluctuations in the hydration shell couple to the internal fluctuations that permit the passage from Xe1 to the heme iron. The fact that both the solvent-slaved and the hydration-controlled motions involve random walks with a large number of steps implies that the number of statistical substates in CS1α and in CS1β must be large. Finally, consider nonslaved processes. One example is the covalent binding of a ligand, for instance CO, to the heme iron, characterized by kBA. This process does not appear to be controlled by external fluctuations but is entropically slowed by vibrations (50).

The characteristics of the three classes of processes hint as to their origins. The slaved motions are absent in a rigid environment; they need volume and/or shape fluctuations. Molecules as large as isonitriles can enter and leave Mb, but no permanent opening exists. The opening must be dynamic, involving large structural motions (51). Changes in shape, induced by collisions with “icebergs” in the surrounding liquid (52), may be involved. Hydration-controlled motions most likely involve side chains (53-57).

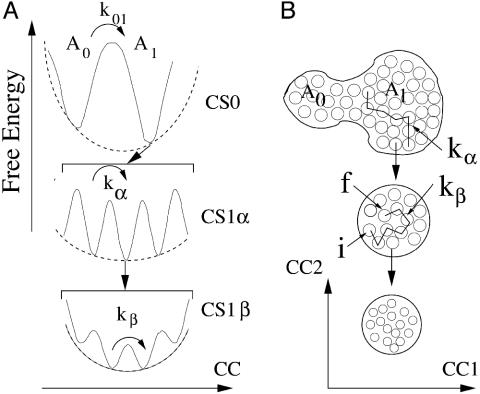

The Energy Landscape

The present analysis leads to the EL of Mb in Fig. 5. The left side gives a 1D view of the EL, the right view is 2D. The top tier, denoted by CS0, contains a small number of taxonomic substates with different structures that can have different functions (7). Each of the CS0 can assume a very large number of statistical substates CS1. They perform the same function but with different rates. The statistical substates comprise two subtiers, 1α and 1β. Transitions between CS1α, given by kα(T), are slaved to the solvent motions and involve large structural changes. In each CS1α reside CS1β. The β-fluctuations, given by kβ(T), are transitions between CS1β. Below the CS1β are at least two more tiers (24, 58). Presumably, the hierarchical arrangement of substates is responsible for control of functionally important protein motions (59). Motions in tier 0 are the result of a large number of successive transitions among CS1α. If these are blocked, transitions between the CS0 cannot occur. If motions in tier1β are absent, we infer that transitions in tier1α are blocked. How far down the control reaches is not known.

Fig. 5.

The EL of Mb. (Left) A projection of the very-high-dimensional EL onto one conformational coordinate. (Right) A projection onto two conformational coordinates. We call the CS0 taxonomic substates, because they can be distinguished and characterized in detail. In each CS0 reside a large number of CS1α substates. In each CS1α a large number of CS1β substates reside. The numbers of substates in CS1α and CS1β is so large that their properties must be described by distributions. We call them statistical substates. The substates below CS1 likely involve local regions of the protein.

Fig. 5A is imperfect; it is a 1D cross section through a conformational space of a few thousand dimensions. Fig. 5B, a two-dimensional view, already gives a more realistic impression. It shows, for instance, that a very large number of different pathways go from one substate to another one. In the actual conformational hyperspace, with a few thousand dimensions, the number of pathways leading from one CS to another one is extremely large, and return to the starting point is unlikely.

Glass Temperatures

The study of protein dynamics is to a large extent the study of relaxations and fluctuations. These can be characterized by their glass transition temperature, Tg, which is conventionally defined as the temperature where the rate coefficient is 10-2 s-1. With this definition, Fig. 4 gives  K for the α-fluctuations and

K for the α-fluctuations and  K for the extrapolated β-fluctuations. The two glass temperatures depend differently on the protein environment.

K for the extrapolated β-fluctuations. The two glass temperatures depend differently on the protein environment.  is slaved to the bulk solvent and in a solid environment is essentially infinite.

is slaved to the bulk solvent and in a solid environment is essentially infinite.  depends weakly on solvent and is finite even in a solid environment. Proteins thus have two glass temperatures with very different properties. The “dynamic transition temperature Td” (11, 31, 32) is not defined in terms of a rate but is the temperature where 〈x2(T)〉c appears to vanish (Fig. 2). No transition takes place at Td; processes continue smoothly below Td, and 200 K is not a special protein temperature.

depends weakly on solvent and is finite even in a solid environment. Proteins thus have two glass temperatures with very different properties. The “dynamic transition temperature Td” (11, 31, 32) is not defined in terms of a rate but is the temperature where 〈x2(T)〉c appears to vanish (Fig. 2). No transition takes place at Td; processes continue smoothly below Td, and 200 K is not a special protein temperature.

Summary and Outlook

Mössbauer effect, neutron-scattering, photon echo, and flash photolysis experiments show that proteins are not semirigid isolated systems, as they are depicted in textbooks. Their dynamics and functions are coupled to motions in the bulk solvent and the hydration shell. We identify three types of protein motions, solvent-slaved, hydration-shell-coupled, and vibrational (nonslaved). Solvent-slaved motions follow the dielectric (α) fluctuations in the bulk solvent and are absent in a solid environment and in dehydrated proteins; their rate coefficients can be approximated by a Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher relation. They involve large-scale conformational changes and govern, for instance, the entrance and exit of ligands such as dioxygen in Mb. Hydration-shell-coupled motions follow fast (β) fluctuations in the hydration shell, occur even if the protein is embedded in a solid, but are absent in dehydrated proteins. They involve side chains and permit processes such as the passage of ligands inside Mb. The recognition that the solvent-slaved and the hydration-shell-coupled fluctuations are different changes the EL of Mb. Tier 1, containing the statistical substates (CS1) involves two “subtiers,” CS1α and CS1β. Solvent-slaved motions are fluctuation among the substates in tier 1α, and hydration-shell-coupled motions are fluctuations in the newly identified tier 1β.

The present work has used only a small fraction of the data that already exist in the literature. Moreover, we have restricted the evaluation to elastic processes. Quasielastic and inelastic processes provide additional information about the fluctuations in proteins. We have also used single-valued rate coefficients, implying exponential time dependences. Processes in complex systems such as proteins, however, are, in general, nonexponential in time; observables must be described by distributions. Many puzzles remain to be solved. We have skirted one particular problem, the relation between α- and β-fluctuations at high temperatures. Below about 270 K, the two can be distinguished unambiguously. Above 270 K, however, it is not clear if the two fluctuations merge or continue separately. Proteins most likely have more than one β-process (37), as some glasses do, but their roles and characteristics are not yet clear. A solution may well be easier to find in proteins, because the two processes can be controlled separately. The study of fluctuations in proteins may be relevant not only for biology but also for the physics of glasses. Finally, we have only discussed the effect of the bulk solvent and the hydration shell on protein dynamics and function. Proteins in the cell, however, interact and we expect that such interactions will affect both dynamics and function. The exploration of such interactions is another challenge for the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kazuyuki Akasaka, Robert Austin, Joel Berendzen, Angel García, Matthew Hastings, Vassiliy Lubchenko, Kia Ngai, Uli Nienhaus, Fritz Parak, Michel Peyrard, Reinhard Schweitzer-Stenner, Steve Sligar, Jeremy Smith, and Peter Wolynes for advice, help, discussions, and often severe, but always constructive, criticism. The research is supported by Department of Energy Contract W-7405-ENG-36 and the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Abbreviations: CS, conformational substates; EL, energy landscape; Mb, myoglobin; msd, mean-square displacement [〈x2(T)〉].

Footnotes

Notation here can lead to confusion. 〈x2(T)〉 is measured along one direction given by the experiment. For isotropic motions one has 〈x2〉 = 〈r2/3〉. In the literature, the notation 〈u2〉 sometimes means 〈r2〉, sometimes 〈x2〉. Here, all amplitude data are reported as 〈x2〉.

References

- 1.Austin, R. H., Beeson, K. W. Eisenstein, L., Frauenfelder, H. & Gunsalus, I. C. (1975) Biochemistry 14, 5355-5373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Case, D. A. & Karplus, M. (1979) J. Mol. Biol. 132, 343-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frauenfelder, H., Petsko, G. A. & Tsernoglou, D. (1979) Nature 280, 558-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frauenfelder, H., Sligar, S. G. & Wolynes P. G. (1991) Science 254, 1598-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onuchic, J. N., Luthey-Schulten, Z. & Wolynes, P. G. (1997) Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 48, 545-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ansari, A., Berendzen, J., Bowne, S. F., Frauenfelder, H., Iben, I. E. T., Sauke, T. B., Shyamsunder, E. & Young, R. D. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 5000-5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frauenfelder, H., McMahon, B. H., Austin, R. H., Chu, K. & Groves, J. T. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 2370-2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenimore, P. W., Frauenfelder, H., McMahon, B. H. & Parak, F. G. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16047-16051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parak, F., Knapp, E. W. & Kucheida, D. (1982) J. Mol. Biol. 161, 177-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keller, H. & Debrunner, P. G. (1980) Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 68-71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parak, F. G. (2003) Rep. Prog. Phys. 66, 103-129. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bee, M. (1988) Quasielastic Neutron Scattering (Adam-Hilger, Bristol, U.K.).

- 13.Becker, T. & Smith, J. C. (2003) Phys. Rev. E 67, 021904-021912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knapp, E. W., Fischer, S. W. & Parak, F. G. (1983) J. Chem. Phys. 78, 4701-4711. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parak, F. & Knapp, E. W. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 7088-7092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parak, F., Heidemeier, J. & Knapp, E. W. (1988) in Biological and Artificial Intelligence Systems, eds. Clementi, E. & Chin, S. (ESCOM, Leiden, The Netherlands), pp. 23-28.

- 17.Nadler, W. & Schulten, K. (1986) J. Chem. Phys. 84, 4015-4025. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandrasekhar, S. (1943) Rev. Mod. Phys. 15, 2-91. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iben, I. E. T., Braunstein, D., Doster, W., Frauenfelder, H., Hong, M. K., Johnson, J. B., Luck, S., Ormos, P., Schulte, A. & Steinbach, P. J. (1989) Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 1916-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stillinger, F. H. & Weber T. A. (1982) Phys. Rev. A 25, 978-989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angell, C. A., Ngai, K. L., McKenna, G. B., McMillan, P. F. & Martin, S. W. (2000) J. Appl. Phys. 88, 3113-3157. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green, J. L., Fan, J. & Angell, C. A. (1994) J. Phys. Chem. 98, 13780-13790. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngai, K. L. & Paluch, M. (2004) J. Chem. Phys. 120, 857-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorn-Leeson, D., Wiersma, D. A., Fritsch, K. & Friedrich, J. (1997) J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 6331-6340. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryngelson, J. D. & Wolynes, P. G. (1989) J. Phys. Chem. 93, 6902-6915. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peyrard, M. (2001) Phys. Rev. E 64, 011109-011115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh, G. P., Parak, F., Hunklinger, S. & Dransfeld, K. (1981) Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 685-688. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vojtechovsky, J., Chu, K., Berendzen, J., Sweet, R. M. & Schlichting, I. (1999) Biophys. J. 77, 2153-2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chong, S.-H., Joti, Y., Kidera, A., Gō, N., Ostermann, A., Gassmann, A. & Parak, F. (2001) Eur. Biophys. J. 30, 319-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostermann, A., Tanaka, I., Engler, N., Niimura, N. & Parak, F. G. (2002) Biophys. Chem. 95, 183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doster, W., Cusack, S. & Petry, W. (1989) Nature 337, 754-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabel, F., Bicout, D., Lehnert, U., Tehei, M., Weik, M. & Zaccai, G. (2002) Q. Rev. Biophys. 35, 327-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrand, M., Dianoux, A. J., Petry, W. & Zaccai, G. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90, 9668-9672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai, A. M., Neumann, D. A. & Bell, L. N. (2000) Biophys. J. 79, 2728-2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rector, K. D., Engholm, J. R., Rella, W. W., Hill, J. R., Dlott, D. D. & Fayer, M. D. (1999) J. Phys. Chem. A 103, 2381-2387. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paciaroni, A., Cinellli, S. & Onori, G. (2002) Biophys. J. 83, 1157-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMahon, B. H., Müller, J. D., Wraight, C. A. & Nienhaus, G. U. (1998) Biophys. J. 74, 2567-2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palazzo, G., Mallardi, A., Hochkoeppler, A., Cordone, L. & Venturoli, G. (2002) Biophys. J. 82, 558-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kriegl, J. M., Forster, F. K & Nienhaus, G. U. (2003) Biophys. J. 85, 1851-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dantsker, D., Samuni, U., Friedman, A. J., Yang, M., Ray, A. & Friedman, J. M. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 315, 239-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleinert, T., Doster, W., Leyser, H., Petry, W., Schwarz, V. & Settles, M. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 717-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlichting, I., Berendzen, J., Phillips, G. N., Jr., & Sweet, R. M. (1994) Nature 371, 808-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srajer, V., Ren, Z., Teng, T. Y., Schmidt, M., Ursby, T., Bourgeois, D., Pradervand, C., Schildkamp, W., Wulff, M. & Moffat, K. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 13802-13815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schotte, F., Lim, M. H., Jackson, T. A., Smirnov, A. V., Sornan, J., Olson, J. S., Phillips, G. N., Wulff, M. & Anfinrud, P. A. (2003) Science 300, 1944-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huck, J. R., Noyel, G. A. & Jorat, L. J. (1988) IEEE Trans. Electr. Insul. 23, 627-638. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergman, R., Swenson, J., Börjesson, L. & Jacobsson, P. (2000) J. Chem. Phys. 113, 357-363. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagen, S. J., Hofrichter, J. & Eaton, W. A. (1996) J. Phys. Chem. 100, 12008-12021. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamb, D. C., Nienhaus, K., Arcovito, A., Draghi, F., Miele, A. E., Brunori, M. & Nienhaus, G. U. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11636-11644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teeter, M. M. (2004) Protein Sci. 13, 313-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McMahon, B. H., Stojkovic, B. P., Hay, P. J., Martin, R. L. & García, A. E. (2000) J. Chem. Phys. 113, 6831-6850. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bourgeois, D., Vallone, B., Schotte, F., Arcovito, A., Miele, A. E., Sciara, G., Wulff, M., Anfinrud, P. & Brunori, M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8704-8709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xia, X. & Wolynes, P. G. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2990-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kneller, G. R. & Smith, J. C. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 242, 181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Careri, G. (1998) Progr. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 70, 223-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doster, W. & Settles, M. (1999) in Hydration Processes in Biology, ed. Bellissent-Funel, M.-C. (IOS Press, Amsterdam), pp. 177-191.

- 56.Tarek, M. & Tobias, D. J. (2002) Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 138101-138104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Engler, N., Ostermann, A., Niimura, N. & Parak, F. G. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10243-10248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hofmann, C., Aartsma, T. J., Michel, H. & Köhler, J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 15534-15538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palmer, R. G., Stein, D. L., Abrahams, E. & Anderson, P. W. (1984) Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 958-961. [Google Scholar]