Abstract

Background

Understanding the regulatory interplay of relevant microRNAs (miRNAs) and mRNAs in the rejecting allograft will result in a better understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of alloimmune injury.

Methods

167 allograft biopsies, with (n=47) and without (n=120) central histology for Banff scored acute rejection (AR), were transcriptionally profiled for mRNA and miRNA by whole genome microarrays and multiplexed microfluidic QPCR respectively. A customized database was curated (GO-Elite) and used to identify AR specific dysregulated mRNAs and the role of perturbations of their relevant miRNAs targets during AR.

Results

AR specific changes in 1035 specific mRNAs were mirrored by AR specific perturbations in 9 relevant miRNAs as predicted by Go-Elite, and were regulated specifically by p53 and FoxP3. Infiltrating lymphocytes and the renal tubules drove the miRNA tissue pertubations in rejection, involving message degradation and transcriptional/translational activation. The expression of many of these miRNAs significantly associated with the intensity of the Banff scored interstitial inflammation and tubulitis.

Conclusion

There is a highly regulated interplay between specific mRNA/miRNAs in allograft rejection that drive both immune mediated injury and tissue repair during acute rejection.

Keywords: Acute rejection, microarray, miRNA, biomarkers, kidney transplantation

Introduction

The coordinated regulation of the allo and innate immune responses in HLA disparate renal transplants and the complex interplay of messenger and microRNA molecules remains to be better understood in acute rejection and accelerated chronic allograft injury and tolerance [1-6]. We proposed to glean a holistic view of graft injury and repair at the transcriptional systems-level, by evaluating the interplay of perturbed messenger RNA (mRNAs) and microRNA (miRNA) pairs in AR by a combination of microarrays, multiplex microfluidic QPCR and bioinformatics.

miRNAs, small RNA molecules of 19-23 nucleotides in length, can be found within introns of genes, are derived from genes and byproducts of mRNA processing [7], and have been recently interrogated in organ transplant injury [7-10]. miRNAs can impact hundreds of mRNA targets, and can impact protein translation/function through transcriptional regulation, mRNA degradation and protein binding, [7, 8]. To investigate the interactions between dysregulated mRNAs and their regulating miRNAs during renal allograft rejection, we utilized an integrated approach combing different transcriptional measurement technologies and data analyses strategies to infer and validate AR specific mRNA/miRNA perturbations and thus expand our understanding of previously described and novel transcriptional processes in graft injury and repair.

Methods

Patient and sample population

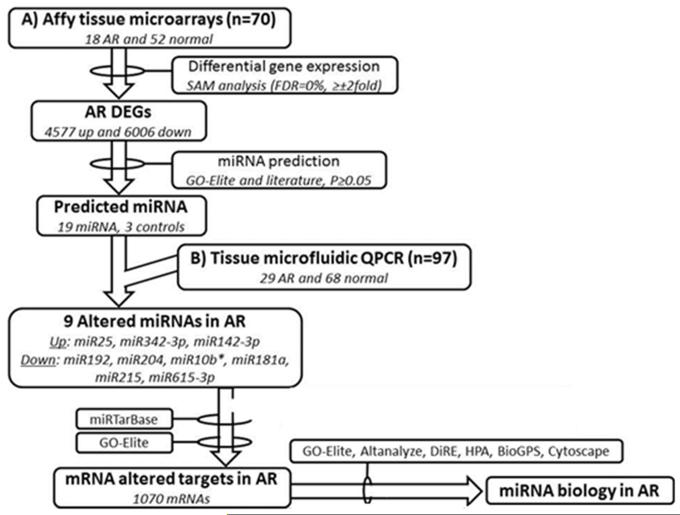

The study population consisted of 167 renal allograft biopsy tissue samples from pediatric renal allograft recipients transplanted at Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford between the years 2003–2006. Routine surveillance tissue biopsies were collected from these patients at implantation (0), 3, 6, 12 and 24 months post-transplantation, and at indication of renal dysfunction for diagnostic histological evaluation. Histological scores were measured for chronic and acute histological Banff [11-14] schema by a central pathologist (NK) for all patients. Detailed clinical and demographic data was collected on all enrolled patients. Stable (STA) samples were defined by an absence of all chronic and acute Banff categories (interstitial fibrosis [ci=0], tubulitis [t=0] and interstitial infiltrate [i=0]), and with minimal tubular atrophy (ct<1). AR samples were defined by a minimum tubulitis (t) and infiltrate (i) score of one or greater in both. Only cellular rejection samples were considered for this study, hence all selected AR samples were C4d negative, and were negative for measured donor specific antibodies at tissue sampling. Tissue diagnosis of BK nephropathy and recurrent diseases samples were exclusion criteria for this study. A total of 167 unique tissue biopsy samples were included in the study from 167 unique patients, and stratified into two groups: Group1 (n=70; 18 AR, 52 noAR) patient samples were used for microarray discovery of AR specific mRNA and GO-Elite prediction of AR specific miRNAs, and Group2 (n=97; 29 AR, 68 noAR) patient samples were used for AR specific miRNA QPCR validation (Figure1; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Project design and analysis flow

Table 1.

Demographic details of 167 study subjects, subdivided into 2 independent Groups

| Parameter | mRNA microarray (Group1; n=70) |

miRNA QPCR (Group2; n=97) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor age (years) | 30.6±11.2 | 29.2±13 | NS |

| Donor sex (male, %) | 48% | 56% | 0.1 |

| Cold ischemia time (hours) | 8.1±4.8 | 10.8±2.0 | 0.4 |

| Transplant type (deceased, %) | 57% | 61% | 0.28 |

| Recipient age (years) | 11.9±5.5 | 13.3±1.1 | 0.6 |

| Recipient sex (male, %) | 61% | 59% | 0.8 |

| Delayed graft function (cases, %) | 26% | 19% | 0.06 |

| AR samples (cases, % of biopsies included in study) |

10 (34%) | 29 (30%) | 1 |

Sample preparation

Total RNA was extracted from biopsy samples using TRIzol® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per manufactures’ protocol. Total RNA was measured for RNA integrity using the RNA 6000 Nano LabChip® Kit on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) (acceptable RNA quality was a RNA integrity number exceeding 7) [15, 16].

mRNA analysis by whole genome microarrays

100ng of extracted total-RNA was first reverse transcribed into cDNA and then amplified. Amplified cDNA was then labeled with Biotin using the Ovation™ Biotin System (NuGEN Technologies, San Carlos, CA), fragmented and hybridized onto Affymetrix GeneChip® Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Arrays comprising more than 54,000 probe sets, covering 38,500 human genes (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA), following the manufactures’ protocol. Microarrays were scanned using the GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA) on predefined settings [1]. The microarrays were normalized and analyzed using the latest versions of R (2.13.0) statistical computing environment [17] and Bioconductor 2.8 [18] and varied data analyses tools were utilized, inclusive of Affymetrix Pressurized Logistics Module (affyPLM; [19], Guanine Cytosine Robust Multi-Array Analysis [GCRMA] [20], Linear Model for Microarray Analysis [LIMMA] [21], Affymetrix LIMMA Graphical User Interface [affylmGUI; [22] and statistical analysis of microarrays or SAM [23]. Microarray data was normalized using probe-level linear modeling [24] and to enable assimilation of data analysis with public microarray data, Affymetrix probe identifiers were re-annotated using AILUN [25]. Differentially expressed genes (DEG) were defined by a fold discovery rate or FDR of 1% and a fold change ≥2 comparing AR and NORM biopsies.

mRNA/miRNA selection in AR

Using the mRNA DEGs defined from the transplant biopsies associated with AR, we used a customized software algorithm (NS), called GO-Elite [26], to predict miRNAs that target these altered genes. Unlike most pathway resource tools that are limited to one resource input, that can often become outdated, GO-Elite has curated input from various annotation public databases, inclusive of miRTarBase [27], TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org), RNAhybrid (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid/), miRBase (http://www.mirbase.org) and Pictar (http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de), PAZAR (http://www.pazar.info) and Amadeus (http://acgt.cs.tau.ac.il/amadeus) that functionally or inferentially link miRNA/mRNA. This software can be run using an intuitive graphical user interface, through command-line arguments, using a web interface and through the program GenMAPP-CS. The advantage of this program is that it exploits the structured nature of biological ontologies to report a minimal set of non-overlapping terms. GO-Elite uses a hypergeometric distribution method to select a miRNA association if it proposed in a minimum of 2 different miRNA annotation data sources. Using a Fisher test for target enrichment, we identified 19 miRNAs that were significant for their expression in AR; selection criteria for these miRNAs is shown in Table 2. We also selected 4 reference miRNAs for QPCR validation from GO-Elite (Table 2). All selected microRNAs were analyzed by QPCR on an independent set of biopsies (Group2) to confirm the biological validity of the “in silico” prediction on the discovery set of samples (Group1).

Table 2.

List of 19 miRNAs investigated in renal transplant biopsies by microfluidic QPCR, along with 3 endogenous reference miRNA

| miRNA name/ symbol |

Fisher adjusted P-value |

Source | Hypothesized direction in AR |

Resource |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted miRNAs | ||||

| hsa-miR-101-3p | 8.30E-09 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-182-5p | 9.39E-09 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-301b | 3.44E-07 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-215 | 2.18E-06 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-429 | 2.51E-06 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-142-3p | 3.46E-06 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| miR419-5p | 7.45E-05 | Kidney | down | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-25 | 0.0006 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-17-5p | 0.009 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-192 | 0.0009 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-615-3p | 0.0079 | Kidney | down | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-28-5p | 0.0081 | Kidney | down | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-181a | 0.0066 | Kidney/ lymphocytes | up | GO-Elite [26]/ [51] |

| hsa-miR-362-3p | 0.0182 | Kidney | down | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-194 | 0.0164 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| hsa-miR-342-3p | 0.0480 | Kidney | up | GO-Elite [26] |

| Control miRNAs | ||||

| hsa-miR-204 | NA | Kidney | Down | [52] |

| hsa-miR-211 | NA | miR204 family (sequence homology) |

Down | [53] |

| hsa-miR-10b | NA | Kidney (mouse) | up | [54] |

| Endogenous reference miRNAs | ||||

| hsa-miR-191 | NA | Cancer | Stable | [55]/ [56] |

| hsa-miR-103 | NA | insulin sensitivity | Stable | [55] / [57] |

| RNU6B (U6) | NA | unknown | Stable | [52, 55, 58] |

hsa-miR= Human miRNA, NA=not applicable

Microfluidic quantitative PCR for miRNA validation

miRNA within the total RNA (50ng) was reverse transcribed using MegaPlex RT primers Human V3 (Applied Biosystems [ABI], Foster City, CA), with ‘Card A’ and ‘Card B’ primers in separate reactions, adding Multiscribe Reverse Transcriptase (ABI) and other components in a final volume of 8ul for 40 cycles, followed by enzyme inactivation in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf Vapo-Protect, Hamburg, Germany). Specific target amplification (STA) was performed using 2ul of the RT reaction along with Megaplex PreAmp primers (ABI) and Taqman PreAmp Master mix (ABI) to 5ul final volume, again ‘Card A’ and ‘Card B’ primers in separate reactions, for 18 cycles in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf), then diluted 1:10 with sterile water (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), following Fluidigm’s miRNA advance development protocol (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, CA). Microfluidic quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) was performed using the 96.96 dynamic BioMark array (Fluidigm) with 2.25ul of the diluted sample from the STA, along with Taqman Assays (ABI) for each miRNA (Table 2), Taqman Universal master mix (ABI) and Loading reagents were primed and loaded onto the chip via the HX IFC Controller (Fluidigm). The QPCR was run with default parameters for gene expression data collection as advised by Fluidigm. Standard Comparative Ct was used to determine relative fold change gene expression using miR-hs-191 as the internal endogenous control reference and Universal Human Total-RNA as the external comparative reference (Agilent).

Bioinformatic and statistical analysis

Using previously published bioinformatics approaches for array data analyses [28] [29], tissue specific mRNA targets were identified significant for biopsy confirmed AR (p<0.001; FDR<1%; fold change ≥2) from the discovery sample set in group1. GO-Elite was next used to infer significant miRNA/mRNA interactions, and based on this a list of miRNAs were then verified in the same biopsy samples (Group1) used for mRNA discovery and then validated in independent samples (Group2) by microfluidic QPCR. To further validate the interactome loop between mRNA/miRNAs, the Go-Elite was used to reverse map the significant miRNAs by QPCR to multiple other mRNA targets. Some of these were again validated (Group2) by QPCR to confirm the biological link between the specific mRNA/miRNA in graft rejection. DEG targets of the miRNA and DEG lists were analyzed to identify enriched biological processes, normal renal histological staining and canonical pathway analysis using the SOURCE [30], GeneCards® [31], BioGPS [32], Human Protein Atlas [33, 34] and PubMed. Nominal clinical variables were analyzed using either an unpaired Students T-Test for two groups or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for 3 or more groups using Graphpad Prizm (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Categorical clinical and histopathology data (Banff score ≥1) were analyzed using a Fisher exact test. Correlations were performed using a Pearson correlation coefficient with absolute value > 0.3 and P-value < 0.05 considered significant for miRNA expression, mRNA gene expression and allograft function. Probe-sets that did not map to a gene symbol after re-annotation (AILUN) were removed, along with duplicate gene symbol entries, thus each gene was only considered once in each list. Non-parametric trend test for order groups [35] for the association of miRNA expression was conducted against a semi-quantitative (0-3; 0= less than 5% of renal parenchyma affected, 1=6-25% of renal parenchyma affected, 2= 26-50% of renal parenchyma affected and 3= greater than 51% of renal parenchyma affected) chronic (ct) and acute injury (t and i) score on contemporaneous biopsies. A multivariate confounder analysis was performed using multivariate logistic regression and a probability < 0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analyses. Post-hoc probabilities are presented for microarray analyses.

Results

Confirming the transcriptional mRNA signature of AR and predicting their relevant miRNA targets by GO-Elite

There was a strong signal for many significantly (p<0.01; FDR<1%) perturbed genes (n=10,583) in the biopsy tissue at the time of established rejection, as previously shown in our studies [35]; with 4577 up-regulated and 6006 down-regulated genes (fold change >2), with overlapping molecular and biological functions as previously published [36]. Prediction of highly enriched (p<0.01) microRNA targets with GO-Elite identified miRNAs that were predicted to directly interact with many AR genes (Table 2, 3).

Table 3.

Expression of miRNA and their experimentally validated mRNA targets

| miRNA | Altered in AR* (QPCR) |

Experimentally verified target (miRTarBase) |

Altered in AR* (Microarrays) |

miRNA-mRNA correlation (Pearson, p<0.05) |

Normal kidney protein expression (IHC, Human Protein Atlas) |

Cell specific expression (BioGPS, 3× median, microarrays) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glomerulus | Tubule | ||||||

| miR25 | Up | PRMT5 | Down | − | + | +++ | 721 Bcell, CD34+ cell, Bronchial epithelial cell |

| TP53 | Down | − | − | − | 721 Bcell | ||

| miR181a | Down | CDX2 | Up | − | − | − | No cell specificity |

| ATM | Up | − | +++ | +++ | CD8+ Tcell, CD4+ Tcell, CD56+ NK cell | ||

| HIPK2 | Up | − | ++ | +++ | No cell specificity | ||

| miR204 | Down | TGFBR1 | Up | −0.51 | + | +++ | No cell specificity |

| TGFBR2 | Up | −0.44 | No data | No data | Adipocyte, smooth muscle cell, CD4+ Tcell | ||

| SNAI1 | Up | −0.55 | +++ | +++ | No cell specificity | ||

| SPDEF | Up | − | No data | No data | No cell specificity | ||

| miR192 | Down | MAD2L1 | Up | − | − | +++ | 721 Bcell, CD105+ Endothelial cell, small intestine |

| HRH1 | Up | −0.53 | + | ++ | No cell specificity | ||

| LMNB2 | Up | −0.58 | No data | No data | 721 Bcell, CD34+ cell, CD105+ endothelial cell | ||

| DTL | Up | − | − | −/+ | CD105+ Endothelial cell, 721 Bcell, CD34+ cell | ||

| miR10b* | Down | NCOR2 | Up | − | + | +++ | No cell specificity |

| miR142-3p | Up | RAC1 | Down | − | −/+ | + | Amygdala |

| miR215 | Down | ACVR2B | Up | − | + | ++ | Placenta |

| miR342-3p | Up | No targets | − | − | − | − | − |

| miR615-3p | Down | No targets | − | − | − | − | − |

Note: only significantly altered miRNA, mRNA targets and correlations listed. Official gene symbol listed for mRNA targets.

= significantly altered compared to normal. IHC = immunohistochemistry,

= negative/ absent,

= very weak,

= weak,

=moderate,

=strong

miRNA alterations in AR: inferential informatics and QPCR measurements

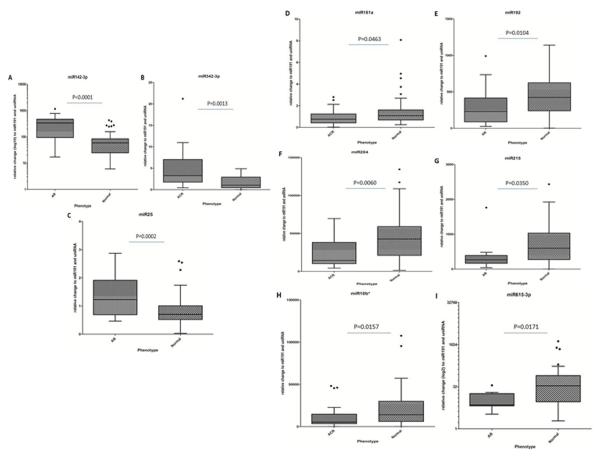

The 16 selected miRNAs were analyzed for differences in abundance in AR in an independent cohort of samples (Group2). Three miRNAs (miR191, miR103, RNU6B (U6)) were selected as the endogenous reference or ‘house-keeping’ miRNA, based on these miRNAs having invariant expression in AR and STA samples with low co-efficient of variation across all study samples. Nine of the 16 miRNAs were significantly (P<0.05) altered in AR (Figure 2, Table 3) with increased expression of 3 (miR142-3p, miR342-3p and miR25) and decreased expression of 6 (miR181a, miR192, miR204, miR215, miR10b* and miR615-3p) in rejecting versus non-rejecting biopsy tissue (Figure 2). Among the 10,583 DEGs found with AR, 1,035 mRNAs were identified as predicted targets of one or more of these 9 miRNAs, when at least two miRNA algorithms were in agreement in GO-Elite.

Figure 2.

Differentially regulated miRNAs in transplant tissues biopsies, with miR142-3p (A), miR342-3p (B) and miR25 (C) all up-regulated in those biopsies with histological evidence of AR compared to normal biopsies. In addition, miR181a (D), miR192 (E), miR204 (F), miR215 (G), miR10b* (H), miR615-3p (I) were all down-regulated in AR compared to normal biopsies.

As the predictions of the mRNA/miRNAs for AR was made by “in silico” informatics, there was a possibility that there may be changes in expression in other highly homologous miRNA family members that may be missed by the software prediction. Both miR211 and miR204 belong to the same miRNA family and have very high mature seed sequence homology with only two base pair nucleotide differences. We tested expression of miR211, which was not predicted to be differentially expressed in AR by GO-Elite, as well as miR204, which was predicted to be altered in AR by Go-Elite. Our QPCR validation confirmed the specificity of the Go-Elite prediction for this miRNA family, as only miR204, and not miR211, was significantly altered, per the software prediction, in AR.miR211 was not inferred by Go-Elite and was not differentially altered in AR, suggesting that miRNA alterations in AR are very specific and not family wide. None of the clinical confounders shown in Table 1 impacted miRNA alterations in AR by multivariate confounder analysis.

Public Database experimental validation of AR specific miRNA/mRNA interactions

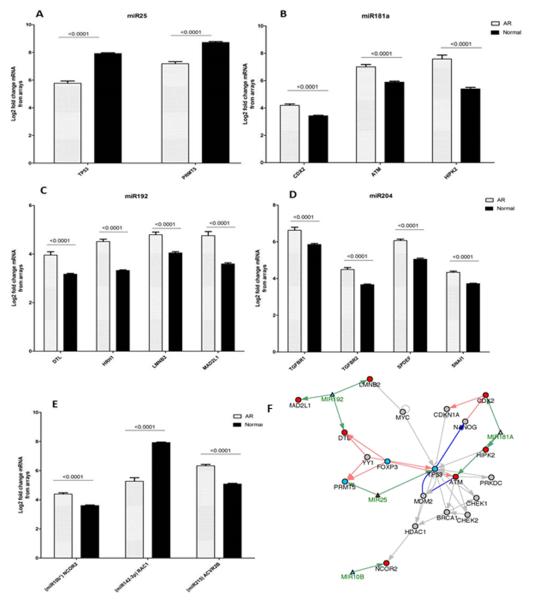

Seven out of 9 of the QPCR validated had experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions, across 50 common mRNAs from the mirTarBase [27], 16 of which are highly regulated also in the AR mRNA microarray data (Table 3 and Figure 3). These 50 mRNAs have highly coordinated biological interactions, centered around the apoptotic regulator and miR25 target, tumor protein 53 or TP53 (Figure 3F). Inverse relationships between miRNA and the 50 target mRNAs were observed for PRMT5 (protein arginine methyltransferase 5) and TP53 (miR25 targets, Fig3A) and ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 or RAC1 (miR142-3p target, Fig3E), where the targets for each were down-regulated and the miRNAs themselves upregulated in AR. The opposite was also found for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2), ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) and HIPK2 (homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2) (miR181a targets, Fig3B); MAD2L1 (mitotic arrest deficient-like 1), HRH1 (histamine receptor H1), LMNB2 (lamin B2) and DTL (denticleless E3 ubiquitin protein ligase homolog) (miR192 targets, Fig3C); TGFβR1 (transforming growth factor, beta receptor 1), TGFβR2 (transforming growth factor, beta receptor 2), SPDEF (SAM pointed domain containing ETS transcription factor) and SNAI1 (snail family zinc finger 1) (miR204 targets, Fig3D); NCOR2 (nuclear receptor corepressor 2) (miR10B* targets, Fig3E) and ACVR2B (activin A receptor, type IIB) (miR215 target, Fig3E).

Figure 3.

Expression of experimentally verified mRNA targets (via miRTarBase) of the altered miRNA, measured by Affymetrix Hu133+2.0 arrays in transplant biopsies. (A) miR25 up-regulated targets TP53 and PRMT5 in AR. (B) miR181a down-regulated targets CDX2, ATM and HIPK2 in AR. (C) miR192 up-regulated targets DTL, HRH1, LMNB2 and MAD2L1 in AR. (D) miR204 up-regulated targets TGFβR1, TGFβR2, SPDEF and SNAI1 in AR. (E) Up-regulated targets NCOR2 and ACVR2B of miR10B* and miR215, respectively, along with down-regulated target RAC1 of miR142-3p in AR. (F) mRNA target interactions of the altered miRNA leads to various mechanism of cell cycle and DNA repair through p53 signaling.

Individual miRNA/mRNA interactions predicted from GO-Elite identified that each of the 6 miRNAs significantly downregulated in AR, coordinated the expression of a large number of mRNAs that follow highly coordinated expression changes: 211 predicted mRNA targets for miR342-3p (increased), 130 for miR192 (decreased), 224 for miR25 (increased), 195 for miR181a (decreased), 113 for miR215 (decreased) and 147 for miR142-3p (increased) Interestingly, inverse regulation relationships between the miRNA and the target mRNAs were only observed for miR25, miR142-3p, miR342-3p and miR615-3p, suggesting that these miRNAs employ a mechanism other than message degradation.

miRNA/mRNA measurements and allograft biopsy histology correlations: message degradation and transcriptional activation implicated

To further explore the relationship and mechanism of action for the detected miRNAs and their mRNA targets we performed a correlation analysis (Pearson) in the 29 samples in Group1 for matched mRNA array/miRNA QPCR in these transplant biopsy samples. miR192 (mRNAs: HRH1 and LMNB2) and miR204 (mRNAs: TGFBR1, TGFBR2 and SNAI1) correlate (negatively) significantly with their targets (Table 3). The remaining altered targets did not correlate with their matched miRNAs, suggesting additional forms of regulation impact mRNA levels that need additional exploration (|r |< 0.3). The same analysis was performed with the miRNA QPCR/GO-Elite predicted mRNA targets (all Group2 samples), whose expression correlates highly with their matched miRNAs. The expression of 168/211 mRNA targets strongly (r=−0.63; p=0.01) negatively correlated with their target miR342-3p, and weaker negative correlations were also seen between 22/224 mRNAs and their target miR25, and 6/147 mRNAs and their target miR142-3p (r < −0.3, p < 0.05). These negative correlations are strong evidence for a direct relationship of message degradation as the mechanism of action in these mRNAs by their targeted miRNAs. Conversely, we observed that positively correlation of miRNA/predicted mRNAs for miR192 (44/130 mRNA targets), miR215 (19/113 mRNA targets) and miR181a (8/195 mRNA targets). The remaining targets were all positively correlated less than our selected threshold. These positive correlations are unexpected and suggest that these particular miRNA work through transcriptional activation mechanisms, rather than the expected mechanisms of transcription degradation of their predicted targets.

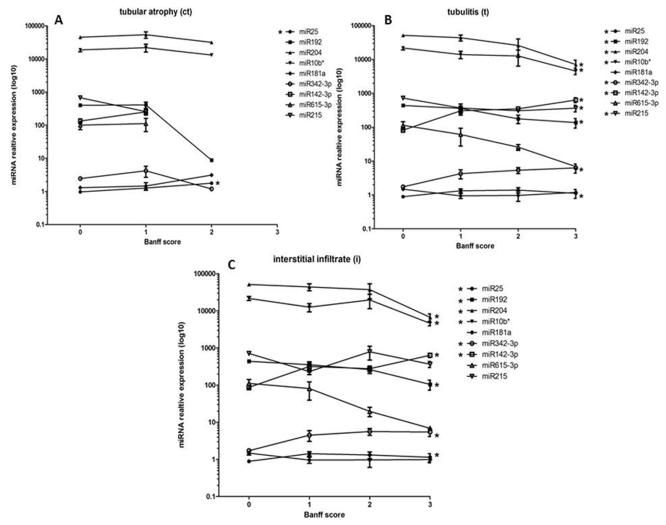

miRNA and Banff grade correlations: miRNA origins relate to lymphocytic infiltration and tubular injury

To evaluate the impact of miRNA transcriptional alterations and tissue compartment injuries in AR, we performed a trend analysis between the expression of the miRNA and the centrally and blindly scored, quantitative Banff grades of tubular atrophy (ct), tubulitis (t) and lymphocytic infiltrate (i) (Figure 4). We observed that miR25 was found to have a significant positive trend with the Banff ct grade (z=2.42, P=0.016, Figure 4A), indicating that the expression of miR25 increases as chronic tubular atrophy increases. For the Banff tubulitis score (Figure 4B), we observed a significant positive trend for miR25 (z=2.25, P=0.025), miR342-3p (z=4.44, P=0.0001) and miR142-3p (z=4.16, P=0.0001). A negative significant trend was observed for Banff t score and miR192 (z=−3.07, P=0.002), miR204 (z=−3.78, P=0.0001), miR10b* (z=−2.96, P=0.003) and miR215 (z=−2.12, P=0.034). In addition, we observed a positive significant trend for miR25 (z=1.96, P=0.05), miR342-3p (z=4.55, P=0.0001) and miR142-3p (z=3.94, P=0.0001) with the Banff i score (Figure 4C). A negative trend was observed for miR192 (z=−3.1, P=0.002), miR204 (z=−3.67, P=0.0001) and miR10b* (z=−2.7, P=0.007) with the Banff i score. The increase in miRNA expression paralleling the increase in the Banff t and i scores suggest that the origin of these are the infiltrating lymphocytes. The negative trend, indicating a decrease in miRNA expression as Banff score t and i score increases strongly suggests that many of these miRNAs are of tubular origin and are a function of the lymphocyte-mediated injury. These trends also indicate that there is a ‘dose’ effect of the lymphocytes, thus these miRNA may serve as severity biomarkers.

Figure 4.

miR25 expression significantly trends with Banff pathology scores for tubular atrophy (A), along with several other miRNAs for Banff scores of tubulitis (B) and infiltrate (C). Significant positive trends were observed between miR25, miR342-3p and miR142-3p and Banff t and i scores, indicating a likely lymphocyte origin for these miRNAs. Significant negative trends were observed for miR192, miR204 andmiR10b* and Banff t and i scores, with miR215 significantly tending (negative) with Banff t only. This suggests an origin of the tubular cells in response to injury during AR. A significant positive trend was only observed between miR25 and Banff ct score, suggesting a role for this miRNA in tubular injury also.

Go-Elite inferred miRNA biology in AR: Non-redundant miRNA of lymphocyte origin targeting tubules, associated with FOXP3

To understand the underlying biology, GO-Elite was used to perform pathway, immune cell marker and transcription factor binding site enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed targets of all nine regulated miRNAs. We also investigated the protein expression of the 16 (miRTarBase) differentially expressed mRNA in normal kidney tissue (Human Protein Atlas) and mRNA expression across cell types (BioGPS, Table 3). From these pathway-level analyses, each miRNA was found to affect a distinct repertoire of biological processes (diverse pathways such as TOR signaling, Gap Junction, Notch signaling, Signaling via HIDAC 2, Synaptic vesicle, and Hedgehog signaling), and a common enriched pathway across the majority of the miRNA was the TGFB signaling pathway.

To further infer on the cellular location and origin of the altered miRNA we investigated the normal expression of their mRNA targets across various cell types and specifically their protein expression in the kidney, using publically available databases of Human Protein Atlas and BioGPS. Investigating the normal protein expression of the 16 experimentally verified mRNA targets, using the data collated by kidney immunohistochemistry, most targets were expressed in the tubules of the normal kidney, with some staining evident in the glomerulus (Table 3). This staining pattern indicates that the miRNA changes in AR likely occur due to the rejection specific tubulitis injury in AR. To further elucidate the most abundant cellular sources of the target mRNAs we performed enrichment analysis of the 10,583 AR specific mRNAs against publically available microarray based normal cellular expression across over 120 cell and tissue types (GSExx) in BioGPS (http://biogps.org) (Table 3). Using the threshold of greater than three times the median expression, the top most abundant cellular origins of the mRNA were from lymphocytes (CD8, CD4, CD34, NK and B cell), followed by endothelial cells. We also observed enrichment in markers for IL15 stimulated NK cells (miR142-3p specifically), memory B cells (miR181a specifically) and dendritic cells (miR192 specifically). Taking these cellular origin findings together we observe that, as expected, the miRNA alterations in the renal tubules result in lymphocyte specific mRNA alterations resultant of the lymphocytic infiltration by different immune specific cells in tubules, the interstitium, vessels and the glomeruli- the hallmarks of graft rejection.

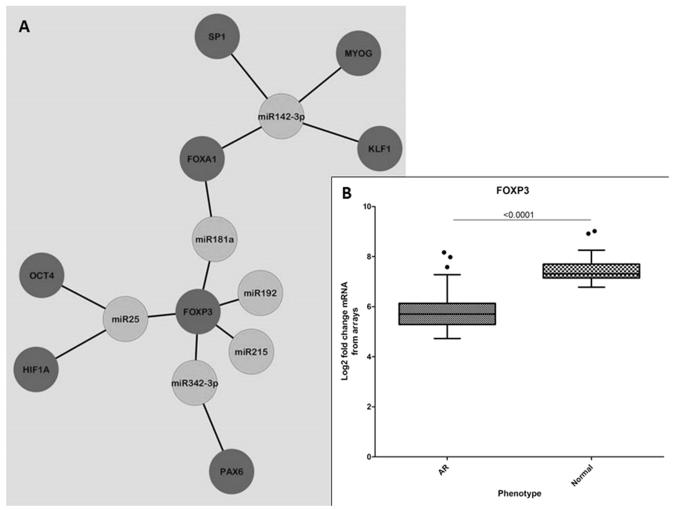

To identify enriched predicted upstream transcriptional regulators, we used the GO-Elite databases (PAZAR and Amadeus), and observed an overwhelming enrichment of FOXP3 regulating a large number of mRNAs targeted by the various altered miRNAs. Collating this data into interaction nodes we observe that FOXP3 is associated with miR25, miR181a, miR192, miR215 and miR342-3p (Figure 3A). This finding was confirmed by an independent analysis of transcription factor binding sites using DiRE (Distant Regulatory Elements of co-regulated genes [http://dire.dcode.org]) where we observed that FOXP3 was constantly in the top 10 identified transcription factors for each miRNA investigated. Indeed, FOXP3 itself is found to be down-regulated in AR compared to STA biopsies (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Transcription factors associated with altered miRNA. (A) Network node displaying the association of various transcription factors (blue) that are predicted to regulate the mRNA targets of the altered miRNA (green). There is a clear cluster of FOXP3 as a consistent transcription factor that regulates a number of the mRNA targets of all altered miRNA except for miR142-3p. (B) FOXP3 is down-regulated in AR (AR), as per mRNA measured by microarrays, which is consistent with its targets also being down-regulated in AR.

Discussion

To better understand the overall immune response in an HLA incompatible allograft, a transcriptionally based systems biology approach, using the bioinformatics integration of lab generated/ validated and publically available mRNA/miRNA associations allows for an in depth analysis of the allograft response to rejection injury. There are two major sources for the perturbations in miRNA and mRNA expression observed in transplant biopsies undergoing rejection: signal from the axis of injury causation, i.e. the infiltrating lymphocytes, and the other is from the injured allograft, with signals of tissue injury and tissue repair. We performed a series of trend analyses with miRNA/mRNA public data experimental validations, cell specific miRNA/mRNA public data expression, miRNA/mRNA QPCR/array lab based validations and quantitative pathology indices for compartmentalized injury. Up-regulated miRNAs, seem to be mostly expressed in the renal tubules and the endothelium, and have a significant positive trend for Banff inflammation (i) and tubulitis (t) scores, suggesting that they may prove to be biomarkers of allograft injury and rejection severity. Alterations in the transcriptional regulation by FOXP3, p53 and TGFb appear to control variations in the expression of many of these kidney tubule specific miRNAs in rejection, and appear to drive downstream transcriptional alterations of lymphocyte and tissue injury specific mRNAs as mediators of tubular injury in graft rejection. We also observe that AR specific miRNA alterations may be regulating downstream mRNAs by mechanisms involving both message degradation and transcriptional activation, and we believe this supports that further studies are needed to better understand the divergence of these miRNA roles in graft rejection. This knowledge can better position us to develop better therapeutics and strategies to selectively tackle both sides of the equation, injury and repair.

A limitation of this study is that we only validated the predicted miRNA interactions from the customized software analysis by Go-Elite; de novo miRNA discovery using miRNA arrays would have likely yielded additional candidates. The miRNAs dysregulated in kidney transplants in this study, like an earlier study by Anglicheau et al. [37], appear to play pivotal roles in the recruitment of different immune infiltrates in graft rejection [38], from T and B cell migration (miR181a), T and B cell survival (miR17-92 cluster), TH2 polarization (miR155) and HLA-G expression and DC activation (miR148a, miR152) [39]. miR142-3p was found to be dysregulated in AR in our study of kidney transplant rejection, as well as in a miRNA study on human small bowel transplant rejection by Asaoka et al. [40], and in a heterotopic allogeneic mouse heart transplant model by Wei et al. [41]. This finding supports our previous studies on that there are common immune core mechanisms of acute rejection in solid organ transplants in humans and rodents, irrespective of tissue source [28] [42]. miR142 has strong expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes [37] and in infiltrating mononuclear cells, specifically CD3+ T cells and CD14+ macrophages [40]. The lymphocytic origin of this particular miRNA is the most probable reason for its detection in AR across different organs. As most of the upregulated miRNAs and mRNAs in AR in this study are mainly of lymphocyte origin and most of the down-regulated miRNAs of tubular origin, it is not unreasonable to postulate that the up-regulated miRNAs reflect the increased burden of infiltrating lymphocytes in rejection, and conversely the down regulated miRNA reflect the tubular injury and fallout as a consequence/ response of rejection injury.

Fibrosis and possible epithelial-to mesenchymal transition (EMT) related mechanisms are observed in the mRNA changes in AR where we see up-regulation of transforming growth factor β receptor 1 and 2 (TGFβR1 and TGFβR2), activin A receptor, type IIB (ACVR2B) and Snail 1 (SNAI1) [43]. Altered expression of homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2), ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) as well as SAM pointed domain containing ETS transcription factor (SPDEF), caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) and MAD2 mitotic arrest deficient-like 1 (MAD2L1) signal via p53 to promote both cell cycle arrest and progression. An increase in DNA repair is supported by the upregulation of denticleless E3 ubiquitin protein ligase homolog (DTL) and DNA replication factor 1 (CDT1) complex, drivers for chromatin stabilization (NCOR2, LAMB2, PRMT5) are also increased. The data supports therefore that the kidney responds to counteract rejection injury and DNA damage via a TP53 mediated mechanism that also promote cell cycle signaling to repair and repopulate renal tubules. It is well established that AR and immune related injury is strongly associated with the appearance of subsequent chronic allograft injury and its progression [1-3]. A number of our identified miRNAs also play a role in immune related chronic fibrosis (miR142-3p, miR215, miR204 and miR192) as they have also been shown to be differentially altered in renal allograft biopsies with chronic allograft injury [44].

Taking the negative correlations with their respective mRNA targets into account, we see that miR25, miR342, miR204, miR615-3p, miR192 (in part) and miR142-3p are working through ‘message degradation’ and not translational repression. Interestingly, we observed that miR192, miR181a and miR215 were positively correlated with their mRNA targets, indicating that an increase in miRNA expression is also causing an increase in mRNA expression. As these miRNA-mRNA pairs are based upon sequence complementary [45, 46], the standard assumption of message degradation can be challenged, and we can postulate that there is a form of transcriptional regulation at play. The simple hypothesis of message degradation is further complicated when we evaluate miR369-3, as it appears to play different roles in the same cells based on their basal activity. Vasudevan et al. were able to show that miR369-3 up-regulated the translation of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) during cell cycle arrest by binding of the miRNA to the AU-rich region of the 3′ untranslated region in TNF-α; though this same miRNA was able switch and subsequently act in repressing translation in the same cells once proliferating [45]. miR373 promotes transcriptional activation of E-cadherin and cold-shock domain-containing protein C2 by binding in a sequence complementary fashion to the promoters of these genes. This binding it extremely sequence specific with various synthesized versions of miR373 as mismatch mutations were unable to promote mRNA expression [46]. All of this strongly suggests that we have identified a number of miRNAs that play a role in both transcriptional and translational regulation in the renal allograft. Further investigation into the biological functions of these miRNAs in the context of rejection and kidney injury is deserving.

Finally, we were able to identify forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) as the major transcription factor that that was predicted to target a large number of the mRNA targets and miRNA relevant in AR. It is has been well established that FOXP3 is a marker of T-regulatory cells and that these cells can attenuate the incidence and severity of rejection [47, 48]. Therefore the altered regulation of FOXP3 in AR is not a surprising finding, however when placed in the context of its association with known miRNAs (miR155, miR21 and miR31 [49, 50]), its new associations in this study with rejection specific miRNAs targets, and its pivotal role with miRNA/mRNA interactions in our customized bioinformatics analyses, increases the potential for additional studies to explore the mechanisms and impact of the miRNA/mRNA transcriptional regulation by FOXP3 in graft rejection.

In conclusion, we have identified a number of novel miRNA that are differentially altered during an episode of AR. Taking the novel approach of integrating a number of different technologies, databases and analyses we have begun to understand the role that these miRNA play in both immune injury and allograft repair. From this we have identified that the graft undergoes cell cycling and DNA damage repair pathways revolving around the pivotal molecule p53 and immune specific miRNA/mRNA changes regulated by FOXP3. We find that infiltrating lymphocytes and the renal tubules are the main source of the miRNA changes in rejection that these miRNAs appear to work via both message degradation as well as transcriptional or translational activation. The miRNAs identified by this study, validated by larger datasets and mechanistic studies, will prove to be integral to how we understand the mechanisms of injury and repair during AR, potentially leading to new treatments to alleviate the immune related injury in graft rejection.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families for participating in this research. The authors also acknowledge from Minh Thien Vu for help with the manuscript preparation. This project was funded by NIH grants UO1AI055795 (MS), RO1AI061739 (MS), and ARRA funding 3UO1 AI077821-0351 (MS).

Abbreviations

- miRNA

micro RNA

- mRNA

message RNA

- AR

acute rejection allograft

- NORM

stable/normal allograft

- DEG

differentially expressed genes

Footnotes

Author contributions

MV was responsible study design, experiments, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. MTV was responsible for the statistical analysis and manuscript writing. TK and MS were responsible for study design, data interpretation and manuscript writing. NS was involved in bioinformatics. SCH and HD performed experiments. RS helped in manuscript writing.

Financial Disclosure

MS is a Consultant for Bristol Meyers Squibb, Organ-I, ISIS, UCB, Genentech and Immucor. TS and NS are Consultants for Organ-I and Immucor.

References

- 1.Naesens M, et al. Microarray expression profiling associates progressive histological damage of renal allografts with innate and adaptive immunity. Kidney International. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.245. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nankivell BJ, et al. Natural history, risk factors, and impact of subclinical rejection in kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78(2):242–9. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000128167.60172.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitalone MJ, et al. Transcriptome changes of chronic tubulointerstitial damage in early kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89(5):537–47. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ca7389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nankivell BJ, et al. The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(24):2326–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roedder S, et al. A Three-Gene Assay for Monitoring Immune Quiescence in Kidney Transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roedder S, et al. The kSORT assay to detect renal transplant patients at high risk for acute rejection: results of the multicenter AART study. PLoS Med. 2014;11(11):e1001759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431(7006):350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack GS. MicroRNA gets down to business. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(6):631–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt0607-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duong Van Huyen JP, et al. MicroRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers of heart transplant rejection. Eur Heart J. 2014 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betts G, et al. Examination of serum miRNA levels in kidney transplant recipients with acute rejection. Transplantation. 2014;97(4):e28–30. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000441098.68212.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Racusen LC, Halloran PF, Solez K. Banff 2003 meeting report: new diagnostic insights and standards. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(10):1562–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Racusen LC, et al. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int. 1999;55(2):713–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solez K, et al. Banff 07 classification of renal allograft pathology: updates and future directions. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(4):753–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solez K, et al. Banff ’05 Meeting Report: differential diagnosis of chronic allograft injury and elimination of chronic allograft nephropathy (‘CAN’) Am J Transplant. 2007;7(3):518–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleige S, Pfaffl MW. RNA integrity and the effect on the real-time qRT-PCR performance. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27(2-3):126–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeder A, et al. The RIN: an RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R. F. f. S. Computing. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bioconductor. 2011 Available from: http://www.bioconductor.org.

- 19.Bolstad BM, et al. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):185–93. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jean(ZHIJIN) Wu RI, MacDonald James, Gentry Jeff. GCRMA (2.22.0) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wettenhall JM, et al. affylmGUI: a graphical user interface for linear modeling of single channel microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(7):897–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(9):5116–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemieux S. Probe-level linear model fitting and mixture modeling results in high accuracy detection of differential gene expression. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:391. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen R, Li L, Butte A. AILUN: reannotating gene expression data automatically. Nature Methods. 2007;4(11) doi: 10.1038/nmeth1107-879. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zambon AC, et al. GO-Elite: a flexible solution for pathway and ontology over-representation. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(16):2209–10. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu SD, et al. miRTarBase: a database curates experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D163–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen-Orr SS, et al. Cell type-specific gene expression differences in complex tissues. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):287–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, et al. A peripheral blood diagnostic test for acute rejection in renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(10):2710–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diehn M, et al. SOURCE: a unified genomic resource of functional annotations, ontologies, and gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):219–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rebhan M, et al. GeneCards: integrating information about genes, proteins and diseases. Trends Genet. 1997;13(4):163. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu C, et al. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 2009;10(11):R130. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uhlen M, et al. A human protein atlas for normal and cancer tissues based on antibody proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4(12):1920–32. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500279-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsson P, et al. Towards a human proteome atlas: high-throughput generation of mono-specific antibodies for tissue profiling. Proteomics. 2005;5(17):4327–37. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med. 1985;4(1):87–90. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780040112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarwal M, et al. Molecular heterogeneity in acute renal allograft rejection identified by DNA microarray profiling. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):125–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anglicheau D, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles predictive of human renal allograft status. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(13):5330–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813121106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spiegel JC, Lorenzen JM, Thum T. Role of microRNAs in immunity and organ transplantation. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e37. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411002080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manaster I, et al. MiRNA-mediated control of HLA-G expression and function. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asaoka T, et al. MicroRNA signature of intestinal acute cellular rejection in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded mucosal biopsies. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):458–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei L, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs during allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(5):1113–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roedder S, et al. Significance and suppression of redundant IL17 responses in acute allograft rejection by bioinformatics based drug repositioning of fenofibrate. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vitalone MJ, et al. The dual role of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in chronic allograft injury in pediatric renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;92(7):787–95. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31822d092c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scian MJ, et al. MicroRNA profiles in allograft tissues and paired urines associate with chronic allograft dysfunction with IF/TA. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(10):2110–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03666.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science. 2007;318(5858):1931–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Place RF, et al. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bestard O, et al. Presence of FoxP3+ regulatory T Cells predicts outcome of subclinical rejection of renal allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(10):2020–6. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chrobak P. Control of T cell responses, tolerance and autoimmunity by regulatory T cells: current concepts. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2003;46(4):131–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu LF, et al. Foxp3-dependent microRNA155 confers competitive fitness to regulatory T cells by targeting SOCS1 protein. Immunity. 2009;30(1):80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rouas R, et al. Human natural Treg microRNA signature: role of microRNA-31 and microRNA-21 in FOXP3 expression. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(6):1608–18. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen CZ, et al. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303(5654):83–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Y, et al. Development of a micro-array to detect human and mouse microRNAs and characterization of expression in human organs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(22):e188. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang FE, et al. MicroRNA-204/211 alters epithelial physiology. FASEB J. 2010;24(5):1552–71. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-125856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beuvink I, et al. A novel microarray approach reveals new tissue-specific signatures of known and predicted mammalian microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(7):e52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peltier HJ, Latham GJ. Normalization of microRNA expression levels in quantitative RT-PCR assays: identification of suitable reference RNA targets in normal and cancerous human solid tissues. RNA. 2008;14(5):844–52. doi: 10.1261/rna.939908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Costinean S, et al. Pre-B cell proliferation and lymphoblastic leukemia/high-grade lymphoma in E(mu)-miR155 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(18):7024–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602266103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trajkovski M, et al. MicroRNAs 103 and 107 regulate insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2011;474(7353):649–53. doi: 10.1038/nature10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liang Y, et al. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal human tissues. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]