Abstract

Increased use of vancomycin has led to the emergence of vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA). To investigate the mechanism of VISA development, 39 methicillin-susceptible strains and 3 MRSA strains were treated with vancomycin to induce non-susceptibility, and mutations in six genes were analyzed. All the strains were treated with vancomycin in vitro for 60 days. MICs were determined by the agar dilution and E-test methods. Vancomycin was then removed to assess the stability of VISA strains and mutations. Following 60 days of vancomycin treatment in vitro, 29/42 VISA strains were generated. The complete sequences of rpoB, vraS, graR, graS, walK, and walR were compared with those in the parental strains. Seven missense mutations including four novel mutations (L466S in rpoB, R232K in graS, I594M in walk, and A111T in walR) were detected frequently in strains with vancomycin MIC ≥ 12 μg/mL. Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test indicated these mutations might play an important role during VISA evolution. After the vancomycin treatment, strains were passaged to vancomycin-free medium for another 60 days, and the MICs of all strains decreased. Our results suggest that rpoB, graS, walk, and walR are more important than vraS and graR in VISA development.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin, drug-resistance, mutations, jonckheere-terpstra trend test

Introduction

Multiple antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus continues to be one of the most common pathogens of both hospital-associated and community-associated infections worldwide (Klevens et al., 2007; Popovich et al., 2007; Hidron et al., 2008; Kallen et al., 2010). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and viral hepatitis B are the three major infectious diseases worldwide and pose a serious threat to public health (Dantes et al., 2013). Vancomycin is the first-line antibiotic therapy for MRSA infections (Sieradzki et al., 1999; Deresinski, 2005; Moellering, 2005). However, increased use of vancomycin has led to the emergence of vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) (Hiramatsu et al., 1997b). Currently, the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) categorizes S. aureus as vancomycin susceptible (VSSA) (MIC ≤ 2 μg/mL), vancomycin intermediate resistant (4–8 μg/mL), and vancomycin resistant (VRSA) (MIC ≥ 16 μg/mL) (Patel, 2014). VISA has been reported more frequently worldwide and has aroused considerable concern (Hiramatsu et al., 1997a, 2002; Tenover and Moellering, 2007; Rishishwar et al., 2016).

VRSA emerged in 1997 due to acquisition of the vanA gene from vancomycin-resistant enterococci (Hiramatsu et al., 1997a; Chang et al., 2003). Previous studies indicated that spontaneous mutations play important roles in the evolution of drug resistance (Drlica, 2003; Andersson and Hughes, 2014). However, the genetic mechanism of vancomycin resistance in VISA strains has not been identified fully (Cameron et al., 2016). Several of mutations in multiple genes and gene regulation systems are needed to achieve a VISA phenotype. Several genetic alterations in two-component regulatory systems have been reported to be strongly associated with a VISA phenotype, including mutations in the vraSR operon (Mwangi et al., 2007), graRS (Howden et al., 2008b; Neoh et al., 2008; Cui et al., 2009), and walRK (Howden et al., 2011; Shoji et al., 2011). VraS may serve as a switch for the activity of the “cell wall stimulon” (Gardete et al., 2012). The vraS I5N mutation was found to confer heterogeneous vancomycin resistance when introduced into a vancomycin-susceptible MRSA strain (Katayama et al., 2009). The graR N197S mutation was suggested to convert strain Mu3 into the VISA phenotype (Neoh et al., 2008). Howden et al. confirmed that the T136I mutation in graS is also a key mediator of vancomycin resistance (Howden et al., 2008b). The G223D mutation in walK and the K208R mutation in walR were associated with increased vancomycin MICs (Howden et al., 2011; Shoji et al., 2011). The rpoB gene, which encodes an RNA polymerase subunit, also plays an important role in the evolution of VISA (Matsuo et al., 2011). The H481Y mutation in rpoB has been confirmed by allelic replacement experiments to increase vancomycin resistance during development of the VISA phenotype in the Mu3 (hVISA) strain (Matsuo et al., 2011). The majority of previous reports on the genetic mechanism of VISA development have focused on clinical MRSA strains (Doddangoudar et al., 2012). The development of vancomycin non-susceptibility might be affected by methicillin or other drug resistance, and so VISA development in methicillin-susceptible strains warrants investigation.

In this study, 39 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus and 3 MRSA strains were treated with increasing concentrations of vancomycin in vitro to investigate the genetic mechanism underlying development of vancomycin resistance. The genes (rpoB, vraS, graSR, and walRK) important for development of vancomycin non-susceptibility were analyzed after 60 days of vancomycin treatment and compared with those in the parental strains. Our results suggest that four novel mutation sites are important for VISA development: L466S in rpoB, R232K in graS, I594M in walK, and A111T in walR.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Forty-two VSSA strains (numbered as S1–S42) used in this study were purchased from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center, China Center of Industrial Culture Collection, Agricultural Culture Collection of China, China Forestry Culture Collection Center, China Center for Type Culture Collection, China Pharmaceutical Culture Collection, National Center for Medical Culture Collections, and China Agricultural University. All strain's background were described in Table 1. Only S22 and S24 were obtained from patients, others were separated from animals or environment. Among these 42 strains, three were MRSA (S3, S34, and S37). All strains were stored at −80°C.

Table 1.

All strains' background.

| Strain ID | Provider | Strain ID | Provider | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1a | 21676b | CICC | S22 | 23656 (ATCC 25923) | CICC |

| S2 | 21600 (ATCC 27217c) | CICC | S23 | 22944 | CICC |

| S3 | 01334 | ACCC | S24 | 1.2465 (ATCC 6538) | CGMCC |

| S4 | 01340 | ACCC | S25 | AB 91119 | CCTCC |

| S5 | 01332 | ACCC | S26 | 10201 | CICC |

| S6 | 01331 | ACCC | S27 | 10499 (ATCC 12600) | ACCC |

| S7 | 01339 | ACCC | S28 | 01012 | ACCC |

| S8 | 10341 | CFCC | S29 | 141405 | CPCC |

| S9 | 1.8721 (ATCC 29213) | CGMCC | S30 | 26003 | CMCC |

| S10 | 1.1697 | CGMCC | S31 | 26112 | CMCC |

| S11 | 1.1476 | CGMCC | S32 | 01011 | ACCC |

| S12 | 141396 | CPCC | S33 | 26001 | CMCC |

| S13 | 140594 | CPCC | S34 | 141431 | CPCC |

| S14 | 140575 | CPCC | S35 | 140660 | CPCC |

| S15 | 21648 | CICC | S36 | 1.1529 | CGMCC |

| S16 | 10786 | CICC | S37 | P1 | CAU |

| S17 | 22942 | CICC | S38 | AB18 | CAU |

| S18 | AB 94004 | CCTCC | S39 | CD1 | CAU |

| S19 | AB 91093 | CCTCC | S40 | CD9 | CAU |

| S20 | AB 91053 | CCTCC | S41 | CD7 | CAU |

| S21 | 23699 | CICC | S42 | 01336 | ACCC |

Strain number;

Center ID;

ATCC ID.

CICC, China Center of Industrial Culture Collection; ACCC, Agricultural Culture Collection of China; CFCC, China Forestry Culture Collection Center; CPCC, China Pharmaceutical Culture Collection; CMCC, National Center for Medical Culture Collections; CCTCC, China Center for Type Culture Collection; CGMCC, China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center; CAU, China Agricultural University.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The vancomycin MICs of all S. aureus parental strains were determined by standardized agar dilution methods, according to the CLSI guidelines (Cockerill, 2012). E-tests were performed using glycopeptide resistance detection strips (bioMérieux), including vancomycin, oxacillin, rifampicin, teicoplanin, according to the manufacturer's instructions. For determination of MICs, a single colony was inoculated in brain-heart infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated at 37°C. At a cell density of 0.5 McFarland units (108 CFU/mL), bacteria were streaked evenly onto Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C, and the MICs were read after 18–24 h of incubation.

In vitro development of vancomycin non-susceptibility

All S. aureus strains were incubated on BHI agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) plates with vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 50% of the initial MIC. Plates were incubated at 37°C, and the strains were passaged to fresh medium containing the same vancomycin concentration every 24 h. MICs were re-determined after 4 days of treatment using the E-test method. The vancomycin concentration was increased to 50% of the new MIC level of each strain. This process was repeated every 4 days for 60 days. Stability of VISA strains was then determined by passaging onto vancomycin-free agar plates every 24 h for 60 days.

Sequence analysis and mutation detection

To identify the point mutations and amino acid changes between 60-day-treated and parental strains, the rpoB, vraS, graS, graR, walK, and walR genes of all treated and parental strains were amplified using the primers shown in Table 2. One colony of each strain was treated with lysostaphin and lysozyme, and genomic DNA was extracted using a TIANamp bacteria DNA kit (Tiangen, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification using genomic DNA as the template was performed using Ex Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd, Kyoto, Japan). The amplification conditions for rpoB, graS, and walK were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final step at 72°C for 7 min. The amplification conditions for vraS, graR, and walR were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final step at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were purified, and their sequences were analyzed. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence comparisons of each pair of treated and parental strains were performed using DNAMAN8.0 (Lynnon Biosoft, USA). Based on the amino acid sequence alignment, the missense mutations were analyzed by Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test.

Table 2.

Sequences of Primers.

| Gene | 5′–3′ primer sequence | Product length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| vraS F | GACGTAGAGGTGATTTATCGATGAACCACT | 1044 |

| vraS R | TTAATCGTCATACGAATCCTCCTTATTTAA | |

| graS F | ATGAGTATGGAACTTGGCGCA | 1592 |

| graS R | TTCCCAGATCCAGAGGGACC | |

| graR F | GGATTAAAGATTTTCAAAGTC | 675 |

| graR R | GAGATTTCAAAAAATAAGCTAC | |

| walR F | ACCAGGTTGGACAGAAGACG | 2000 |

| walR R | TGTGCATTTACGGAGCCCTT | |

| walK F | CGCGTAGAGGCGTTGGATA | 1983 |

| walK R | TGGCTGTCATAGGTGTCGTT | |

| rpoB F1 | GCAAGGTATGCCATCTGCAAAG | 1954 |

| rpoB R1 | TTGCTTCGGCGATACATCCA | |

| rpoB F2 | ACGTGAACGTGCTCAAATGG | 2262 |

| rpoB R2 | ATGCCTTTGTAGCGAACACG |

The presence of mecA and vanA in all strains was detected as described previously using the following primers: mecA forward 5′-TGGCTATCGTGTCACAATCG-3′; reverse 5′-CTGGAACTTGTTGAGCAGAG-3′; vanA forward 5′-ATGAATAGAATAAAAGTTGC-3′; reverse 5′-TCACCCCTTTAACGCTAATA-3′ (Saha et al., 2008). The multilocus sequence typing (MLST) genotypes of all strains were also determined as described (Enright et al., 2000). Seven housekeeping genes of all parental strains were sequenced to obtain the sequence type (ST) of each strain.

Statistical analysis

Based on the relationships between the MICs and time points during the vancomycin treatment, the 42 strains were grouped by hierarchical clustering (Tibshirani et al., 2001). After the in vitro treatment, genotypes were coded as 0, 1, or 2 for each SNP in sequenced genes. The association between each mutation site and MICs measured after 60 days vancomycin treatment was analyzed using the Jonckheere-Terpstra (JT) trend test (Jonckheere, 1954). P < 0.05 were considered to indicate significance. All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software (version 2.1).

Results

Development of vancomycin-intermediate resistance in S. aureus in vitro

Forty-two VSSA strains were treated with vancomycin in vitro for 60 days. After induction, although the MICs varied, only the MIC of the S10 strain remained unchanged compared with its parental strain. In contrast, the MICs of many strains increased significantly (Figure 1). Twenty-nine VISA strains were generated within 60 days, while 13 strains remained vancomycin susceptible (MIC < 4 μg/mL). The maximum MIC of 16 μg/mL was achieved in 4/29 strains: S8, S15, S16, and S41. The MICs of these four strains met the standard for VRSA rather than VISA strains; however, the vanA gene cluster, a common vancomycin-resistance determinant, was absent (data not shown). The MICs of all strains were listed in Table 3.

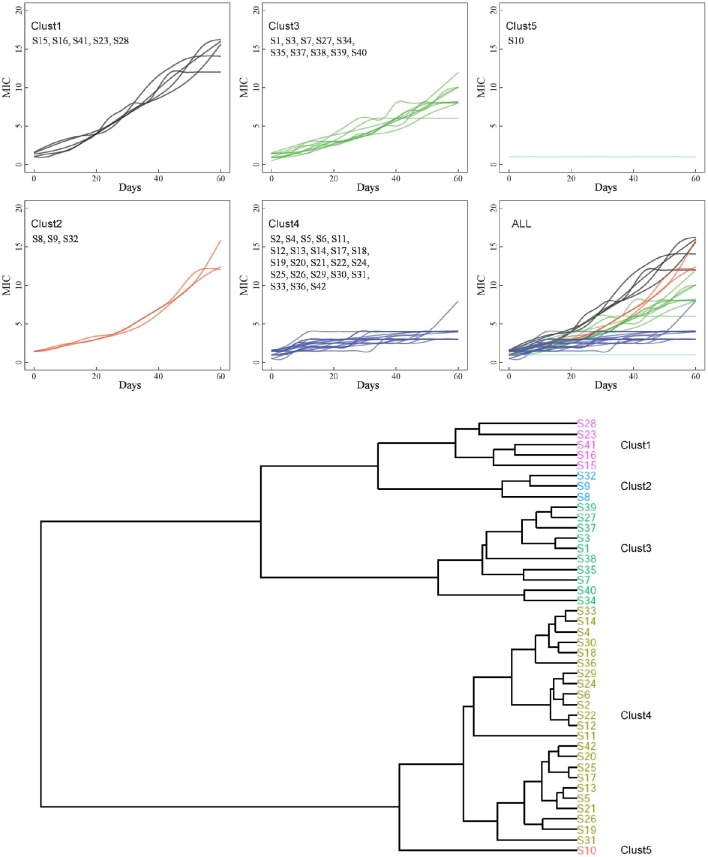

Figure 1.

Hierarchical clustering of 42 strains. Based on the association between MICs and time point, the entire 42 strains were grouped into 5 clusters by hierarchical clustering.

Table 3.

Amino acids mutations in VISA development.

| Cluster | Strain | STa | MICb(μg/mL) | RpoB | vraS | graR | graS | walK | walR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | S15 | 97 | 1.5/16 | L466Sc, H481N, T1182I | V15G | —d (Q148Q)e | I59L, R232K | R222K, A468T, I594M | A111T |

| S16 | 239 | 1.5/16 | —(S466S, N481N) | G15V | — (Q148Q) | — (K232K) | I594M, (K222K, T468T) | A111T | |

| S41 | 9 | 1.0/16 | L466S, H481N | V15G | D148Q | L26F, I59L, R232K | R222K, A468T, I594M | A111T | |

| S28 | 943 | 1.5/14 | T1182I | Q126K | K17E, (Q148Q) | I59L, D97E | L265R | — | |

| S23 | 943 | 1.0/12 | T1182I | T331I | — (Q148Q) | I193M | — | — | |

| C2 | S8 | 6 | 1.5/16 | D1046V | — | — (D148D) | L59I | D266N | — |

| S9 | 5 | 1.5/12 | R917S | — | — (D148D) | — | G25A | — | |

| S32 | 243 | 1.5/12 | F279L, I1182T | — | — (Q148Q) | L26F, D97E | T270S, (T468T) | — | |

| C3 | S35 | 8 | 1.5/12 | L466S, H481N | V15G | — (Q148Q) | R232K | R222K, K294N, D302N, A468T, I594M | A111T |

| S1 | 8 | 1.5/10 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | L59I | — | P216S | |

| S3 | 239 | 1.5/10 | T1182I, (S466S, N481N) | — | — (Q148Q) | L26F, I59L, R232K | — (K222K, T468T) | — | |

| S7 | 243 | 1.5/10 | T518M | — | V136I, S207G, (Q148Q) | L59I | H385P, (T468T) | — | |

| S27 | 464 | 1.0/8 | — | — | S79F, (Q148Q) | — | — | A111V | |

| S37 | 9 | 1.0/8 | — (N481N) | L105F | — (D148D) | L59I, E97D | R264K, L265R, D302N | — | |

| S38 | 9 | 1.0/8 | — | — | — (D148D) | L59I, E97D | — | — | |

| S39 | 9 | 1.0/8 | — | G92D | — (D148D) | L26F | — | — | |

| S40 | 9 | 1.0/8 | — | — | — (D148D) | L26F, G209S | L10F, S506Y, S591F | — | |

| S34 | 464 | 0.5/6 | — | — | — (D148D) | — | — | — | |

| C4 | S11 | 96 | 1.0/8 | D631E, T1182I | — | — (D148D) | F26L | A243T | — |

| S5 | 239 | 1.5/4 | Y737F, I1182T | G15V | Q148H | L59I | K540R, G560C, (T468T) | — | |

| S13 | 464 | 1.5/4 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | I183K, R265L, H464Y | — | |

| S17 | 943 | 1.5/4 | T1182I | — | — (Q148Q) | I59L, D97E | — | R119H | |

| S19 | 464 | 1.0/4 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | — | F192L | |

| S20 | 464 | 1.0/4 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | T471I | — | |

| S21 | 464 | 1.5/4 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | V15L, R265L | — | |

| S25 | 243 | 1.5/4 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | — (T468T) | — | |

| S26 | 464 | 1.0/4 | — | G20A | — (Q148Q) | W158C | L265R, T279I | — | |

| S31 | 464 | 1.5/4 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | — (T468T) | — | |

| S42 | 5 | 1.5/4 | — | — | — (D148D) | F26L, R160H, Y223D, I224T | D302N | — | |

| S2 | 5 | 1.5/3 | — | — | — (D148D) | — | R265L | — | |

| S4 | 243 | 1.5/3 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | — (T468T) | — | |

| S6 | 243 | 1.5/3 | P945S, I1182T | — | — (Q148Q) | I59L | — (T468T) | — | |

| S12 | 464 | 1.5/3 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | F26L, L59I | D290E | — | |

| S14 | 464 | 1.0/3 | G1139V, T1182I | — | — (Q148Q) | F26L | R343H | — | |

| S18 | 96 | 1.0/3 | T1182I | — | — (D148D) | — | R265L, R298M | R222L | |

| S22 | 243 | 1.5/3 | T1182I | — | I136V, G207S, (Q148Q) | T224I | — (T468T) | — | |

| S24 | 464 | 1.5/3 | I1182T | — | — (Q148Q) | — | — | P216L | |

| S29 | 464 | 1.5/3 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | — | — | |

| S30 | 464 | 0.5/3 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | — | — | R107H | |

| S33 | 30 | 1.0/3 | — | — | — (Q148Q) | F26L, Y223D | L265R, L314P | — | |

| S36 | 770 | 0.5/3 | — | — | — (D148D) | L26F, D223Y | — | — | |

| C5 | S10 | 9 | 1.0/1 | — | — | — (D148D) | L26F, D223Y, T224I | — | K208N, P216Q |

ST, sequence type.

MIC (μg/mL), MICs of parental/vancomycin treated strains.

Bold indicates the novel mutations.

Dash indicates amino acids had no change after 60 days vancomycin treatment.

Parentheses indicates the amino acids remain unchanged.

Based on the relationships between the MICs and time points, the 42 strains were grouped into five clusters by hierarchical clustering (Figure 1). Eight strains were found in C1 and C2 and showed the highest MICs (12–16 μg/mL). These strains exhibited rapid development of vancomycin-intermediate resistance, which was accompanied by several common mutations in sequenced genes, such as L466S and H481N in rpoB, R232K in graS, R222K, A468T, and I594M in walK, and A111T in walR (Table 3).

The third cluster comprised 10 strains. The MICs of these strains increased gradually over time, reaching 6–12 μg/mL. Twenty-three strains, including 12 VSSA strains, were grouped in C4 and exhibited slow development of vancomycin non-susceptibility, resulting in MICs of 3–8 μg/mL. Only the MIC of S11, which harbored the A243T mutation in walK, increased to 8 μg/mL (Table 3). Only strain S10 was grouped in C5. The MIC of S10 was unchanged after the 60 days of treatment.

The sequence type (ST) of all parental strains was shown in Table 3. Most (8/9) of the strains with MICs ≥ 12 μg/mL were assigned to different ST types.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of all S. aureus strains

To determine susceptibilities to other antibiotics after 60 days of treatment, the oxacillin, rifampicin, and teicoplanin MICs of all strains were measured by the E-test. The MICs of several strains from each cluster are shown in Table 4. All of the 42 VSSA parental strains were initially susceptible to teicoplanin, three (S3, S34, and S37) were resistant to oxacillin, and two (S3 and S16) were resistant to rifampicin. After vancomycin treatment, the teicoplanin MICs of most strains increased, while the oxacillin and rifampicin MICs of most strains did not change. In contrast, the oxacillin MICs of five strains (S3, S15, S16, S34, and S37) decreased. Three VISA strains (S1560, S3560, and S3760) became resistant to rifampicin, and the five rifampicin resistant strains carried Asn (N) in the 481st amino acid of rpoB (Table 3). However, the parental strains S37 and S4160, which also carried this Asn (N), were susceptible to rifampicin.

Table 4.

Antibiotic susceptibilities changes of strains.

| Cluster | Straina | MIC (μg/mL) | Antibiotic susceptibility | E-test MIC (μg/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXA | RIF | TEI | OXA | RIF | TEI | |||

| C1 | S15 | 1.5 | S | S | S | 1 | 0.064 | 2 |

| S1560 | 16 | S | R | I | 0.5 | >256 | 16 | |

| S16 | 1.5 | S | R | S | 1 | >256 | 4 | |

| S1660 | 16 | S | R | R | 0.5 | >256 | 16 | |

| S41 | 1 | S | S | S | 0.5 | 0.064 | 1 | |

| S4160 | 16 | S | S | S | 0.5 | 0.064 | 8 | |

| S28 | 1.5 | S | S | S | 0.25 | 0.064 | 4 | |

| S2860 | 14 | S | S | I | 0.25 | 0.064 | 16 | |

| C2 | S8 | 1.5 | S | S | S | 0.5 | 0.064 | 2 |

| S860 | 16 | S | S | I | 0.5 | 0.064 | 16 | |

| S9 | 1.5 | S | S | S | 0.25 | 0.064 | 2 | |

| S960 | 12 | S | S | I | 0.25 | 0.064 | 16 | |

| S32 | 1.5 | S | S | S | 0.125 | 0.064 | 2 | |

| S3260 | 12 | S | S | I | 0.125 | 0.064 | 16 | |

| C3 | S3 | 1.5 | R | R | S | >256 | >256 | 1 |

| S360 | 10 | R | R | S | 32 | >256 | 8 | |

| S34 | 0.5 | R | S | S | 32 | 0.064 | 0.5 | |

| S3460 | 6 | R | S | S | 8 | 0.064 | 4 | |

| S35 | 1.5 | S | S | S | 0.25 | 0.064 | 1 | |

| S3560 | 12 | S | R | S | 0.5 | >256 | 8 | |

| S37 | 1 | R | S | S | >256 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| S3760 | 8 | R | R | S | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| C4 | S2 | 1.5 | S | S | S | 0.125 | 0.064 | 2 |

| S260 | 3 | S | S | S | 0.25 | 0.064 | 2 | |

| S5 | 1.5 | S | S | S | 0.125 | 0.064 | 1 | |

| S560 | 4 | S | S | S | 0.125 | 0.064 | 2 | |

| S11 | 1 | S | S | S | 0.5 | 0.064 | 0.064 | |

| S1160 | 8 | S | S | S | 0.5 | 0.064 | 8 | |

| C5 | S10 | 1 | S | S | S | 0.25 | 0.064 | 1 |

| S1060 | 1 | S | S | S | 0.25 | 0.064 | 1 | |

OXA, oxacillin; RIF, rifampicin; TEI, teicoplanin. S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

No subscript represents parental strains.

Subscript indicates strains treated by vancomycin for 60 days.

Amino acid mutations involved in VISA development

The complete sequences of rpoB, vraS, graS, graR, walK, and walR were amplified from all strains. Only missense mutations were observed by amino acid sequence alignment between the 60 days' vancomycin-treated strains and parental strains. A large number of SNPs were detected, and the mutations varied among the strains. Multiple nonsynonymous mutations in the six genes are shown in Table 3.

In rpoB, we found 10 distinct amino acid changes in 13/29 (44.8%) VISA strains: F279L, L466S, H481N, T518M, D631E, Y737F, R917S, D1046V, and T1182I/I1182T. No amino acid substitution was found at the 466th or 481st locus in the VSSA strains treated by vancomycin for 60 days. Notably, the T1182I/I1182T mutations not only occurred frequently in VISA strains but were also found in VSSA strains. In vraS, seven distinct missense mutations were identified in 10/29 (34.5%) VISA strains. No nonsynonymous SNPs were found in the other VISA or VSSA strains. In the graRS operon, 19 distinct mutations were identified in 20/29 (69.0%) VISA strains. The L26F/F26L, I59L/L59I, and Y223D mutations were present in both VISA and VSSA strains, while the D223Y and T224I mutations were detected only in VSSA strains. Twenty-two of the 29 (75.9%) VISA strains harbored mutations in the walRK operon, including 23 distinct mutations in walK and 5 in walR. Among these mutations, R222K, A468T, and I594M in walK and A111T in walR occurred more frequently. Furthermore, all VSSA strains lacked R222K, I594M, and A111T but carried several other mutations.

Overall, three VISA strains (S15, S35, and S41) contained the L466S and H481N mutations in rpoB, accompanied by the mutations R232K in graS, R222K, A468T, and I594M in walK, and A111T in walR and acquired high-level vancomycin resistance (MIC ≥ 12 μg/mL). The walK mutation was carried most frequently by VISA strains. A previous report stated that mutations in walK were most frequent in 39 clinical VISA strains from various countries (Shoji et al., 2011).

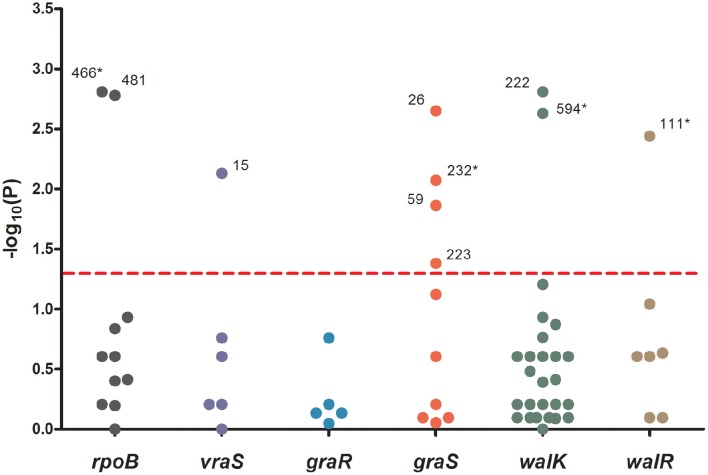

To analyze the associations between mutation sites and MICs, strain genotypes were coded as 0, 1, or 2 for each mutation in sequenced genes. The associations between mutations and MICs at 60 days were analyzed using the Jonckheere-Terpstra (JT) trend test. As shown in Figure 2, 10 mutations (L466S and H481N in rpoB, V15G in vraS, L26F, I59L, Y223D, and R232K in graS, R222K, and I594M in walK and A111T in walR) were significantly correlated with the MIC differences, including four novel mutation sites (L466S in rpoB, R232K in graS, I594M in walK and A111T in walR). These four mutation sites were only occurred in five strains with MICs ≥ 10 μg/mL and have not been reported to date. The P values of all mutations in graR were >0.05, indicating that this gene might be relatively unimportant in the process of VISA development.

Figure 2.

The significance of association between each mutation sites and MICs. Data was analyzed by Jonckheere-Terpstra (JT) trend test. The x axis shown six sequenced genes and the y axis shown −log10 of the P values resulting from the JT trend test. Each dot represented a mutation site, and the number beside the dot shown the amino acid position. P < 0.05 were considered significant. *The novel mutation sites found in this study.

Stability of vancomycin non-susceptibility

To investigate the stability of vancomycin non-susceptibility, strains were incubated on vancomycin-free agar plates for another 60 days after the vancomycin treatment. The MICs of all strains (except S10) decreased after the removal of vancomycin, while S35 and S41 remained as VISA strains. Six genes (rpoB, vraS, graS, graR, walK, and walR) were sequenced and compared with the genes before vancomycin removal. The strains with mutations were shown in Table 5; 27 reverse mutations and 13 random mutations were detected compared with those vancomycin treated strains. Only the reverse mutation F10L in walK might be related to a decrease in the MIC.

Table 5.

Mutations after removal of vancomycin.

| Cluster | Strain | MIC (μg/mL)a | rpoB | vraS | graR | graS | walK | walR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | S15 | 3 | I1182Tb | —c | — | — | — | — |

| S16 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S41 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S28 | 3 | I1182T | — | — | — | R265L, A554G | — | |

| S23 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| C2 | S8 | 2 | — | — | — | — | N266D | — |

| S9 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S32 | 2 | — | — | — | E97D | L265R | — | |

| C3 | S35 | 6 | — | — | — | — | N294K, N302D | — |

| S1 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S3 | 2 | I1182T | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S7 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S27 | 3 | I1182T | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S37 | 3 | — | — | — | — | K264R, R265L, N302D | — | |

| S38 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S39 | 2 | T1182I | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S40 | 1 | — | — | — | — | F10L, Y506S, F591S | — | |

| S34 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| C4 | S11 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| S5 | 3 | — | — | H148Q, V136I, S207G | F26L | — | — | |

| S13 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S17 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S19 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | L192F | |

| S20 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S21 | 3 | — | — | E15D | — | — | — | |

| S25 | 2 | — | — | I136V, G207S | — | — | — | |

| S26 | 1 | — | — | — | — | R265L | — | |

| S31 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S42 | 2 | — | S39F | — | — | N302D | — | |

| S2 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S4 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S6 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S12 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S14 | 1 | I1182T | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S18 | 2 | I1182T | — | — | — | L265R | — | |

| S22 | 2 | I1182T | — | V136I, S207G | — | — | — | |

| S24 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S29 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S30 | 1 | I1182T | — | — | — | — | — | |

| S33 | 1 | — | — | — | — | P314L | — | |

| S36 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| C5 | S10 | 1 | I1182T | — | — | — | — | N208K, Q216P |

MIC (μg/mL), MICs after vancomycin removal for 60 days.

Bold indicates reverse mutations.

Dash indicates the amino acids remain unchanged.

Discussion

VISA strains are increasingly prevalent in the hospital setting and are a major issue in the treatment of MRSA infections. It has been suggested that the occurrence of VISA strains is relatively frequent, representing a threat to public health (Sader et al., 2009). Prolonged vancomycin exposure in patients can contribute to generation of VISA, resulting in treatment failure (Liu et al., 2011). In addition, VISA can also be generated in vitro from VSSA strains by exposure to vancomycin (Matsuo et al., 2011; Doddangoudar et al., 2012). Previous studies of the mechanisms of VISA development focused on clinical MRSA strains (Doddangoudar et al., 2012), while few studies have addressed VISA development in methicillin-susceptible strains. In this study, 29 (69%) VISA strains were generated from 42 S. aureus strains by vancomycin treatment for 60 days in vitro. Our results suggest that seven mutation sites are important for VISA development, including four novel mutations: L466S in rpoB, R232K in graS, I594M in walK, and A111T in walR.

Hierarchical clustering which can directly decompose the dataset into a set of disjoint clusters was performed to trace the dynamic changes in VISA development, and investigate different vancomycin non-susceptibility evolution patterns. The 42 strains were grouped into five clusters, and the MICs of nine strains (eight from C1 and C2 and one from C3) were ≥12 μg/mL (Figure 1). Among those nine strains, only S28 and S23 were assigned to the same ST type (Table 3). 38/42 parental strains was susceptible to oxacillin, rifampicin and teicoplanin. The three MRSA strains (S3, S34, and S37) were resistant to oxacillin, and 2/42 strains (S3 and S16) were resistant to rifampicin. Strains S3 and S16 developed high MICs (10–16 μg/mL) after vancomycin treatment. Three methicillin-susceptible strains—S8, S15, and S41—showed the highest MIC of 16 μg/mL. There was no significant correlation between VISA development and initial resistance to oxacillin, rifampicin or teicoplanin. The oxacillin MICs of five strains (S3, S15, S16, S34, and S37) decreased after vancomycin treatment. It has been suggested that upon acquisition of vancomycin resistance, some strains show a concomitant decrease in oxacillin resistance (Bhateja et al., 2006), and a previous study reported that mutated graR may impair oxacillin resistance (Neoh et al., 2008). In this study, no graR mutation was detected in these five strains. The H481Y/N mutation is located in the rifampin resistance-determining region, and this locus has been reported repeatedly in clinical rifampicin-resistant S. aureus strains (Aubry-Damon et al., 1998; O'Neill et al., 2006; Mick et al., 2010). In this study, five rifampicin-resistant strains harbored the Asn (N) mutation in the 481st amino acid of rpoB (Table 3). However, the parental strains S37 and S4160, which harbor Asn (N), were susceptible to rifampicin. In summary, no significant association was found between these mutations and antibiotic susceptibility changes.

The genetic basis for vancomycin resistance in VISA remains unclear. The rpoB, vraSR, graSR, and walRK genes have been reported to be highly associated with vancomycin resistance. In this study, the complete sequences of rpoB, vraS, graS, graR, walK, and walR were analyzed and compared with those of the susceptible parental strains. Seven mutations occurred more frequently in strains with high MICs (12–16 μg/mL), including L466S and H481N in rpoB, R232K in graS, R222K, A468T, and I594M in walK, and A111T in walR (Table 3). In vitro experiment and JT trend test indicated that four novel mutation sites were important for VISA development—L466S, R232K, I594M, and A111T—which were first reported in this study (Figure 2).

Alam et al. reported that rpoB H481 is the predominant locus associated with an increased vancomycin MIC (Alam et al., 2014). The mutations H481Y/N in rpoB play a dual role in rifampin and vancomycin resistance (Watanabe et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2013). Moreover, it has been suggested that the rpoB mutation itself, and not any other incidental genetic change caused by rifampin resistance, was responsible for the decreased vancomycin susceptibility (Matsuo et al., 2011). In this study, two mutations (L466S and H481N) were significantly associated with increased vancomycin MICs. Although the L466S mutation had not been reported previously, it might be important for the development of VISA.

In vraS, the 15th amino acid locus was significantly associated with MIC according to the JT trend test, but both the V15G and G15V mutations were detected in different VISA strains. Therefore, V15G/G15V seemed to be less important in VISA development.

D148Q mutation in graR was reported previously to be important for development of high-level resistance (Neoh et al., 2008; Doddangoudar et al., 2012). In this study, only the S41 strain contained the D148Q mutation in graR (MIC = 16 μg/mL), while 28/42 (66.7%) VSSA parental strains initially harbored Gln (Q) at locus 148. Therefore, we speculated that the D148Q mutation in graR did not significantly affect the development of vancomycin resistance. The S79F mutation is important in the development of VISA strains (Neoh et al., 2008; Shoji et al., 2011; Doddangoudar et al., 2012; Hafer et al., 2012). Among our strains, only S27 carried the S79F mutation, and exhibited a MIC of 8 μg/mL. According to the JT trend test, no mutation in graR and four mutations (L26F, I59L, Y223D, and R232K) in graS were significantly related to elevated vancomycin MICs. However, the L26F/F26L, I59L/L59I, and Y223D mutations were detected in both VISA and VSSA strains. Thus, these mutation sites were unlikely to be responsible for VISA development. The R232K mutation occurred frequently (3/9) in strains with high MICs (12–16 μg/mL) and was absent in VSSA strains. This suggests that the R232K mutation is involved in the development of vancomycin-intermediate resistance.

G223D mutation in walK and K208R mutation in walR were associated with increased vancomycin MICs (Howden et al., 2011; Shoji et al., 2011). However, these genetic changes are not observed frequently in clinical and laboratory S. aureus strains (Howden et al., 2008a,b; Kato et al., 2010). Shoji et al. collected 39 clinical VISA strains from various countries worldwide and then analyzed the complete sequences of vraSR, graSR, clpP, and walRK. Nine of the 39 (23%) VISA strains from four countries harbored R222K and A468T mutations in walK. The L10F and A243T mutations in walK and P216S in walR have been reported previously in VISA strains (Shoji et al., 2011; Hafer et al., 2012). In this study, 3/9 VISA strains with MICs ≥ 12 μg/mL harbored the R222K mutation, S3 and S16 initially carried Lys (K) at locus 222. The A468T mutation occurred in the same three VISA strains as R222K, while other ten strains carried Thr (T) including seven VISA strains initially (Table 3). Therefore, A468T seemed to be important for VISA development. According to the JT trend test, R222K, I594M in walK and A111T in walR were significantly associated with vancomycin resistance. Although the mutations I594M in walK and A111T in walR have not been reported to date, they were frequently detected (4/9) in strains with MICs ≥ 12 μg/mL. The presence of I594M and A111T in the same strain may result in development of the VISA phenotype.

Overall, seven amino acid changes—L466S, H481N, R232K, R222K, A468T, I594M, and A111T—were detected frequently in our VISA strains. Although the four novel non-synonymous mutations L466S, R232K, I594M, and A111T have not been reported to date, we speculate that these mutations may play an important role in development of VISA strains, together with the H481N, R222K, and A468T mutations, synergistically promote and maintain high-level vancomycin resistance. Several other mutations were detected in both VISA and VSSA strains or in only VSSA strains. Whether these mutations affect development of a VISA phenotype remains unknown. Notably, certain VISA strains did not harbor any important mutations within the sequenced genes. The increased MICs of these strains may be caused by mutations in other undetected/unidentified genes, such as the proteolytic regulatory gene clp (Shoji et al., 2011) and the accessory gene regulator agr (Sakoulas et al., 2002, 2005).

After removal of vancomycin for 60 days, the MICs of all strains decreased. The L10F mutation in walK has been reported previously in VISA strains, thus, the reverse mutation F10L in walK might be associated with loss of vancomycin resistance. These findings suggest that VISA development is affected by a complex gene regulatory network, although other genes or pathways might be involved in decreased MICs observed. The presence of stop codons in vraS and graR was reported to be related to loss of vancomycin non-susceptibility (Doddangoudar et al., 2012). However, no stop codon was detected in this study.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that prolonged vancomycin exposure leads to development of vancomycin-intermediate resistance in methicillin-susceptible S. aureus strains. Compared with the susceptible parental strains, four novel missense mutations—L466S in rpoB, R232K in graS, I594M in walK and A111T in walR—were detected in high-level vancomycin-resistant strains. Our results also suggest that rpoB, graS, walK and walR are more important than vraS and graR in the evolution of vancomycin non-susceptibility.

Author contributions

YJ, XH, and RW conceived and designed the experiments. YW, XL, LJ, and WH. performed the experiments. XX, YJ, XH, and RW analyzed the data, YW and YJ. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University (TD2012-03), the Special Fund for Forest Scientific Research in the Public Welfare (201404102), Natural Science Foundation of China (51108029) and a “One-Thousand Person Plan” award.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer SA and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation and the handling Editor states that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

References

- Alam M. T., Petit R. A., Crispell E. K., Thornton T. A., Conneely K. N., Jiang Y., et al. (2014). Dissecting vancomycin-intermediate resistance in Staphylococcus aureus using genome-wide association. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 1174–1185. 10.1093/gbe/evu092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson D. I., Hughes D. (2014). Microbiological effects of sublethal levels of antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 465–478. 10.1038/nrmicro3270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry-Damon H., Soussy C. J., Courvalin P. (1998). Characterization of mutations in the rpoB gene that confer rifampin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 2590–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhateja P., Purnapatre K., Dube S., Fatma T., Rattan A. (2006). Characterisation of laboratory-generated vancomycin intermediate resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 27, 201–211. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron D. R., Jiang J. H., Kostoulias X., Foxwell D. J., Peleg A. Y. (2016). Vancomycin susceptibility in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is mediated by YycHI activation of the WalRK essential two-component regulatory system. Sci. Rep. 6:30823. 10.1038/srep30823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S., Sievert D. M., Hageman J. C., Boulton M. L., Tenover F. C., Downes F. P., et al. (2003). Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N.Engl. J. Med. 348, 1342–1347. 10.1056/NEJMoa025025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerill F. R. (2012). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically: Approved Standard. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cui L., Neoh H. M., Shoji M., Hiramatsu K. (2009). Contribution of vraSR and graSR point mutations to vancomycin resistance in vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 1231–1234. 10.1128/AAC.01173-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantes R., Mu Y., Belflower R., Aragon D., Dumyati G., Harrison L. H., et al. (2013). National burden of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, United States, 2011. JAMA Intern. Med. 173, 1970–1978. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deresinski S. (2005). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an evolutionary, epidemiologic, and therapeutic odyssey. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 562–573. 10.1086/427701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doddangoudar V. C., O'Donoghue M. M., Chong E. Y., Tsang D. N., Boost M. V. (2012). Role of stop codons in development and loss of vancomycin non-susceptibility in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2101–2106. 10.1093/jac/dks171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drlica K. (2003). The mutant selection window and antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52, 11–17. 10.1093/jac/dkg269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright M. C., Day N. P., Davies C. E., Peacock S. J., Spratt B. G. (2000). Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Cameron D. R., Davies J. K., Kostoulias X., Stepnell J., Tuck K. L., et al. (2013). The RpoB H148Y rifampicin resistance mutation and an active stringent response reduce virulence and increase resistance to innate immune responses in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 207, 929–939. 10.1093/infdis/jis772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardete S., Kim C., Hartmann B. M., Mwangi M., Roux C. M., Dunman P. M., et al. (2012). Genetic pathway in acquisition and loss of vancomycin resistance in a methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain of clonal type USA300. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002505. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafer C., Lin Y., Kornblum J., Lowy F. D., Uhlemann A. C. (2012). Contribution of selected gene mutations to resistance in clinical isolates of vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 5845–5851. 10.1128/AAC.01139-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidron A. I., Edwards J. R., Patel J., Horan T. C., Sievert D. M., Pollock D. A., et al. (2008). NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 29, 996–1011. 10.1086/591861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu K., Aritaka N., Hanaki H., Kawasaki S., Hosoda Y., Hori S., et al. (1997a). Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet 350, 1670–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu K., Hanaki H., Ino T., Yabuta K., Oguri T., Tenover F. C. (1997b). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40, 135–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu K., Okuma K., Ma X. X., Yamamoto M., Hori S., Kapi M. (2002). New trends in Staphylococcus aureus infections: glycopeptide resistance in hospital and methicillin resistance in the community. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 15, 407–413. 10.1097/00001432-200208000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howden B. P., McEvoy C. R., Allen D. L., Chua K., Gao W., Harrison P. F., et al. (2011). Evolution of multidrug resistance during Staphylococcus aureus infection involves mutation of the essential two component regulator WalKR. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002359. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howden B. P., Smith D. J., Mansell A., Johnson P. D., Ward P. B., Stinear T. P., et al. (2008a). Different bacterial gene expression patterns and attenuated host immune responses are associated with the evolution of low-level vancomycin resistance during persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. BMC Microbiol. 8:39. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howden B. P., Stinear T. P., Allen D. L., Johnson P. D., Ward P. B., Davies J. K. (2008b). Genomic analysis reveals a point mutation in the two-component sensor gene graS that leads to intermediate vancomycin resistance in clinical Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 3755–3762. 10.1128/AAC.01613-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonckheere A. R. (1954). A distribution-free k-sample test against ordered alternatives. Biometrika 41, 133–145. 10.1093/biomet/41.1-2.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kallen A. J., Mu Y., Bulens S., Reingold A., Petit S., Gershman K., et al. (2010). Health care-associated invasive MRSA infections, 2005-2008. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 304, 641–648. 10.1001/jama.2010.1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama Y., Murakami-Kuroda H., Cui L., Hiramatsu K. (2009). Selection of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus by imipenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 3190–3196. 10.1128/AAC.00834-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y., Suzuki T., Ida T., Maebashi K. (2010). Genetic changes associated with glycopeptide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: predominance of amino acid substitutions in YvqF/VraSR. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 37–45. 10.1093/jac/dkp394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens R. M., Morrison M. A., Nadle J., Petit S., Gershman K., Ray S., et al. (2007). Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 298, 1763–1771. 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Bayer A., Cosgrove S. E., Daum R. S., Fridkin S. K., Gorwitz R. J., et al. (2011). Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, 285–292. 10.1093/cid/cir034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo M., Hishinuma T., Katayama Y., Cui L., Kapi M., Hiramatsu K. (2011). Mutation of RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB) promotes hVISA-to-VISA phenotypic conversion of strain Mu3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 4188–4195. 10.1128/AAC.00398-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mick V., Domínguez M. A., Tubau F., Liñares J., Pujol M., Martín R. (2010). Molecular characterization of resistance to Rifampicin in an emerging hospital-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone ST228, Spain. BMC Microbiol. 10:68. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moellering R. C., Jr. (2005). The management of infections due to drug-resistant gram-positive bacteria. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24, 777–779. 10.1007/s10096-005-0062-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi M. M., Wu S. W., Zhou Y., Sieradzki K., de Lencastre H., Richardson P., et al. (2007). Tracking the in vivo evolution of multidrug resistance in Staphylococcus aureus by whole-genome sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9451–9456. 10.1073/pnas.0609839104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neoh H. M., Cui L., Yuzawa H., Takeuchi F., Matsuo M., Hiramatsu K. (2008). Mutated response regulator graR is responsible for phenotypic conversion of Staphylococcus aureus from heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate resistance to vancomycin-intermediate resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 45–53. 10.1128/AAC.00534-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill A. J., Huovinen T., Fishwick C. W., Chopra I. (2006). Molecular genetic and structural modeling studies of Staphylococcus aureus RNA polymerase and the fitness of rifampin resistance genotypes in relation to clinical prevalence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 298–309. 10.1128/AAC.50.1.298-309.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel J. B. (2014). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-Fourth Informational Supplement. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Popovich K., Hota B., Rice T., Aroutcheva A., Weinstein R. A. (2007). Phenotypic prediction rule for community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 2293–2295. 10.1128/JCM.00044-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rishishwar L., Kraft C. S., Jordan I. K. (2016). Population genomics of reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. mSphere 1:e00094-16. 10.1128/mSphere.00094-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sader H. S., Jones R. N., Rossi K. L., Rybak M. J. (2009). Occurrence of vancomycin-tolerant and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains (hVISA) among Staphylococcus aureus causing bloodstream infections in nine USA hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64, 1024–1028. 10.1093/jac/dkp319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha B., Singh A. K., Ghosh A., Bal M. (2008). Identification and characterization of a vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Kolkata (South Asia). J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 72–79. 10.1099/jmm.0.47144-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakoulas G., Eliopoulos G. M., Fowler V. G., Moellering R. C., Novick R. P., Lucindo N., et al. (2005). Reduced susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to vancomycin and platelet microbicidal protein correlates with defective autolysis and loss of accessory gene regulator (agr) function. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 2687–2692. 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2687-2692.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakoulas G., Eliopoulos G. M., Moellering R. C., Wennersten C., Venkataraman L., Novick R. P., et al. (2002). Accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1492–1502. 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1492-1502.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M., Cui L., Iizuka R., Komoto A., Neoh H. M., Watanabe Y., et al. (2011). walK and clpP mutations confer reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 3870–3881. 10.1128/AAC.01563-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieradzki K., Roberts R. B., Haber S. W., Tomasz A. (1999). The development of vancomycin resistance in a patient with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 517–523. 10.1056/NEJM199902183400704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover F. C., Moellering R. C., Jr. (2007). The rationale for revising the clinical and laboratory standards institute vancomycin minimal inhibitory concentration interpretive criteria for Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44, 1208–1215. 10.1086/513203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R., Walther G., Hastie T. (2001). Estimating the number of clusters in a data set via the gap statistic. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 63, 411–423. 10.1111/1467-9868.00293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y., Cui L., Katayama Y., Kozue K., Hiramatsu K. (2011). Impact of rpoB mutations on reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 2680–2684. 10.1128/JCM.02144-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]