Abstract

Background

Infant mortality is one of the priority public health issues in developing countries like Nepal. The infant mortality rate (IMR) was 48 and 46 per 1000 live births for the year 2006 and 2011, respectively, a slight reduction during the 5 years’ period. A comprehensive analysis that has identified and compared key factors associated with infant mortality is limited in Nepal, and, therefore, this study aims to fill the gap.

Methods

Datasets from Nepal Demographic and Health Surveys (NDHS) 2006 and 2011 were used to identify and compare the major factors associated with infant mortality. Both surveys used multistage stratified cluster sampling techniques. A total of 8707 and 10,826 households were interviewed in 2006 and 2011, with more than 99% response rate in both studies. The survival information of singleton live-born infants born 5 years preceding the two surveys were extracted from the ‘childbirth’ dataset. Multiple logistic regression analysis using a hierarchical modelling approach with the backward elimination method was conducted. Complex Samples Analysis was used to adjust for unequal selection probability due to the multistage stratified cluster-sampling procedure used in both NDHS.

Results

Based on NDHS 2006, ecological region, succeeding birth interval, breastfeeding status and type of delivery assistance were found to be significant predictors of infant mortality. Infants born in hilly region (AOR = 0.43, p = 0.013) and with professional assistance (AOR = 0.27, p = 0.039) had a lower risk of mortality. On the other hand, infants with succeeding birth interval less than 24 months (AOR = 6.66, p = 0.001) and those who were never breastfed (AOR = 1.62, p = 0.044) had a higher risk of mortality.

Based on NDHS 2011, birth interval (preceding and succeeding) and baby’s size at birth were identified to be significantly associated with infant mortality. Infants born with preceding birth interval (AOR = 1.94, p = 0.022) or succeeding birth interval (AOR = 3.22, p = 0.002) shorter than 24 months had higher odds of mortality while those born with a very large or larger than average size had significantly lowered odds (AOR = 0.17, p = 0.008) of mortality.

Conclusion

IMR and associated risk factors differ between NDHS 2006 and 2011 except ‘succeeding birth interval’ which attained significant status in the both study periods. This study identified the ecological region, birth interval, delivery assistant type, baby’s birth size and breastfeeding status as significant predictors of infant mortality.

Keywords: Infant mortality, Region, Birth interval, Birth size, Breastfeeding, Nepal

Background

Infant mortality is defined as the death of a child before reaching the age of one in a specific year or period [1]. Early childhood is a vital period that determines their future health status. Therefore, infant mortality is a sensitive and important indicator that can be used to ascertain the physical quality of life index (PQLI) and wellbeing of a country [2, 3]. Infant mortality remains a major public health priority in many developing countries, and strategies aimed at addressing this challenge are of paramount importance. There are still many factors significantly associated with infant mortality that remain unexplored.

Globally, an estimated 4.6 million deaths occur annually during infancy, 99% of which occur in developing countries [1]. Global IMR has reduced to 34 deaths per 1000 live births in 2013 from an initial estimated 63 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 [1, 4]. The infant mortality rate (IMR) has been declining steadily over the last century around the world; however, some developing countries like Nepal are still far behind. Despite the reduction in infant mortality by two thirds by many countries indicating a progress towards achieving the millennium development goal (MDG)-4 by the year 2015, this has not been evident in sub-Saharan Africa and some Asian countries including Nepal [5, 6]. Hence, disparities and inter-country variations still exist around the world in terms of IMR [7]. Recent trends of childhood deaths in African and Asian countries show that one out of every 12 infants does not survive until adulthood [8]. Additionally, global decline of child mortality is however dominated by the slow decline in sub-Saharan Africa [9].

In the last decade, Nepal made a substantial progress in many aspects of health care delivery; however, infant mortality remains a significant health challenge in the country [10–12]. Between 2006 and 2011 (a period of 5 years), only a marginal reduction was achieved in the rate of infant mortality in Nepal - from 48/1000 live births in 2006 to 46/1000 live births in 2011 [13, 14]. IMR in Nepal is higher in comparison to other Southeast Asian countries such as India, which has an IMR of 42 per 1000 live births; Bangladesh, 41 per 1000 live births and Sri-Lanka, 9 per 1000 live births [15–17]. Progress in IMR reduction is relatively slow when compared to other health indicators like maternal health and immunization of Nepal [10, 18]. Socioeconomic, demographic, ecological and other factors are associated with infant mortality in Nepal [10, 19]. In addition, there are inequalities in infant mortality within the country. For instance, most of the infant death occurs in Mountain region (73/1000 live births) [5], Far Western development regions (65/1000 live births) [13] and those residing in rural areas (47/1000 live births) [20].

Previous studies have explored the factors associated with infant mortality in Nepal. Khadka, Lieberman, Giedraitis, Bhatta and Pandey [20] reported the socioeconomic and proximate determinants associated with infant mortality in their recent study using NDHS. Similarly, Paudel Deepak, Thapa Anil, Shedain Purusotam Raj and Paudel Bhuwan [18] has analysed the trends and determinants related to neonatal mortality in Nepal using NDHS 2001 to 2011. Although many studies have been carried out previously to investigate factors contributing to infant mortality in Nepal using NDHS datasets of different surveys, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies conducted to compare the factors associated with the slow reduction in infant mortality between 2006 and 2011 using NDHS data. Hence, this study aims to explore the significant factors associated with infant mortality in 2006 and in 2011 in Nepal separately and then to fill the gaps by comparing the key factors associated with the slow reduction in infant mortality between 2006 and 2011 using two corresponding NDHS data.

Methods

Data sources

NDHS is a nationally representative survey conducted every 5 years in Nepal with the aim of providing reliable and up-to-date information on health and population issues in the country. It is a measure of the worldwide Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) project in the country. More precisely, DHS collects data on maternal and child health, reproductive health and fertility, immunisation and child survival, HIV and AIDS; maternal mortality, child mortality, malaria, and nutrition amongst women and children [21]. The datasets analysed in this study were extracted from the 2006 and 2011 NDHS. Furthermore, the study included only singleton live births born 5 years preceding both surveys. Both NDHS used multistage stratified cluster sampling technique. At first geographical areas were randomly selected, and then a complete list of dwellings and households were compiled. From those listed 20–30 households were selected using a systematic sampling procedure and then trained interviewers conducted household interviews with the eligible study population [13, 14].

In the 2011 survey, a total of 11,353 households were selected and 10,826 were successfully interviewed [13]. From these selected households, 12,674 eligible women (15–49 years) and 4323 eligible men (15–49 years) were successfully interviewed. Similarly, for the 2006 survey, a total of 8707 households were successfully interviewed out of 9036 selected households. Furthermore, 10,793 and 4397 eligible women and men of 15–49 years completed the interview, respectively [14]. The details of sampling instruments, sampling techniques, data collection and management used by NDHS have been previously discussed and published [4, 18, 20].

Dependent variable

The dependant or outcome variable of this study is Infant Mortality. It has been defined as the probability of a child dying before the age of one (<12 months) in a specific year or period [1]. In regression analysis, the survival status of infants was further recoded as ‘1’ for infant who died within the first 12 months of life and ‘0’ for infants who survived beyond 12 months of life.

Study framework and independent variables

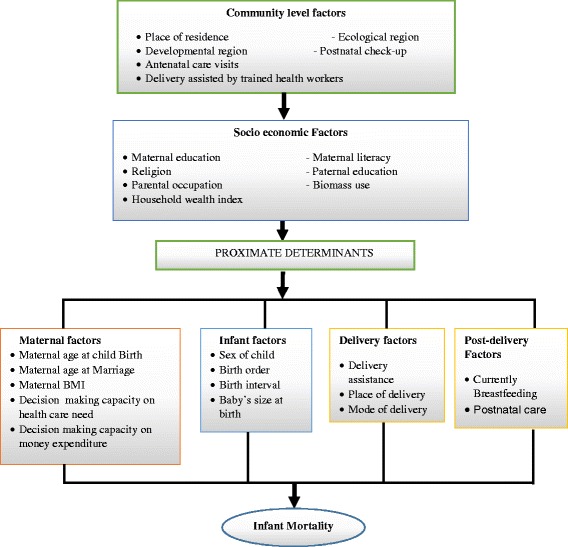

In this study, modified version of Mosley and Chen’s [22] conceptual framework was used considering the context of Nepal (Fig. 1). Factors related to infant mortality were grouped into three levels, namely community factors, socio-economic factors and proximate factors. Mosley and Chen anticipated that proximate factors such as maternal, infant, delivery and post-delivery factors would directly influence infant mortality; and the socioeconomic and community level factors would have an indirect influence [22].

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework for factors affecting Infant Mortality

Selected independent variables along with definitions and coding categories are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operational definition and categorisation of selected explanatory variables for both NDHS 2006 and NDHS 2011

| Variables | Definitions and category |

|---|---|

| Community level factors | |

| Development regions (Administrative) | Developmental regions (1 = Far-Western; 2 = Mid-Western; 3 = Western; 4 = Central; 5 = Eastern) |

| Ecological regions | Ecologically defined area. Division according to ecological zone (3 = Mountain; 2 = Hill; 1 = Terai) |

| Residence | Residence type (1 = Urban; 2 = Rural) |

| Antenatal care visits in the cluster | Any antenatal care service received by mother during pregnancy (0 = Yes; 1 = No) |

| Delivery assisted by trained health workers in the cluster | Birth assistance during delivery in the cluster (0 = Yes/Some; 1 = No/None) |

| Postnatal check-up/care received by mothers in the cluster | Postnatal check-up by mothers after delivery (0 = Yes; 1 = No) |

| Socio economic factors | |

| Maternal education | Maternal formal years of schooling/education (0 = No education; 1 = primary; 2 = secondary; 3 = Higher) |

| Paternal education | Father’s formal years of schooling/education (0 = No education; 1 = primary; 2 = secondary; 4 = Higher) |

| Religion | Religion of parents (1 = Hindu; 2 = Buddhist; 3 = Muslim; 4 = Christian/Kirat/other) |

| Maternal literacy | Mother’s literacy level (1 = able to read whole sentence or only parts; 2 = unable to read at all) |

| Paternal occupation | Father’s employment status (0 = Unemployed; 1 = Employed; 2 = Don’t know) |

| Maternal occupation | Mother’s employment status (0 = Unemployed; 1 = employed) |

| Wealth index | Household index of amenities/families economic status (1 = Poorest; 2 = Poorer; 3 = Middle; 4 = Richer; 5 = Richest) |

| Biomass use (cooking fuel) | Types of cooking fuel used in the family (1 = relatively non-polluting; 2 = relatively high polluting) |

| Proximate determinants | |

| Mother’s age at child birth | Maternal age at childbirth as categorical variable (1 = ≤16 years; 2 = 17–21 years; 3 = ≥22 years) |

| Mother’s age at marriage | Maternal age at first marriage as categorical variable (1 = ≤16 years; 2 = 17–21 years; 3 = ≥22 years) |

| Maternal Marital Status | Maternal marital status (0 = never married; 1 = Currently married; 2 = Widowed; 3 = Divorced/Separated) |

| Decision making on own health care need | Decision making capacity of mothers on her own health care needs (1 = Respondent alone; 2 = Respondent and husband/partner/other; 3 = Husband/partner alone; 4 = Someone else) |

| Decision making capacity on money expenditure | Decision making capacity of mothers on money expenditure. (1 = Respondent alone; 2 = Respondent and husband/partner/other; 3 = Husband/partner alone; 4 = Someone else) |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | Maternal BMI as per WHO classification (1 = Underweight (<18.50); 2 = Normal range (18.50–24.99); 3 = Overweight/Obese- at risk (>25.0) aMaternal BMI Asian (1 = Underweight (<18.49); 2 = Normal range (18.5–24.99); 3 = Overweight/Obese- at risk (>25.0) |

| Sex of child | Sex of infant (0 = Male; 1 = Female) |

| Birth order/rank | Birth rank of infant as a categorical variable (1 = 1st birth rank; 2 = 2nd or 3rd birth rank; 3 = ≥4th birth rank) |

| Birth interval | Succeeding birth interval (0 = ≤24 months; 1= > 24 months) Preceding birth interval (0 = ≤24 months; 1= > 24 months) |

| Baby’s size at birth (Birth size defined by baby’s birth weight) | Subjective assessment of the respondent on the baby’s birth size (1 = very large/larger than average (>3000 g); 2 = average (2500 to 3000 gm); 3 = very small/smaller than average (<2500 g)) |

| Place of delivery | Delivery place (0 = Home; 1 = Health Facility) |

| Mode of delivery | Mode of delivery (1 = Non-caesarean section/Normal/vaginal; 2 = caesarean section) |

| Delivery assistant by | Type of delivery assistance (1 = Professionals (Doctors, Nurses and Midwives; 2-Traditional births attendants (TBAs); 3 = combined; 4 = No assistance) |

| Currently Breastfeeding | Breastfeeding status during the time of interview (1 = yes; 2 = No) |

aMaternal BMI Asian was used in this study

Statistical analysis

To adjust for unequal selection probability due to multistage cluster sampling, Complex Samples Analyses was used in the data analysis and modelling procedures. In the Complex samples analysis procedure, appropriate strata, cluster and weight variables were used to compute more accurate standard errors and confidence intervals. Three stage statistical analyses were conducted in this study. At the first stage, univariate analysis was carried out and IMR was reported, while at the second stage bivariate analysis assessed the unadjusted association (crude odds ratio (COR)) between infant mortality and each of the categorical predictors of interest using simple binary logistic regression analysis. All factors which were with a p value ≤ =0.1 (statistically significant at 10%) in the second stage were candidate factors for next stage multivariable regression analysis. In the third stage, a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the adjusted effect of factors on infant mortality for community level, socio economic level and proximate level factors, separately, and three sets of adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported.

Finally, an additional overall multiple logistic regression analysis was performed. The three sets of significant predictors obtained at the third stage modelling were entered into the final multiple regression model one after another from community level, then socioeconomic level and proximate level hierarchically. At each step of the modelling, the effect of these factors on the infant mortality was assessed and significant factors (at 5% level) were retained for next step of the modelling, using a stepwise backward elimination regression method. This hierarchical regression modelling process was repeated for 2006 and 2011 datasets separately.

The statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp USA).

Results

The study consisted of a total of 5836 live births with 280 infant deaths for NDHS 2006 and 5274 live births with 241 infant deaths for NDHS 2011. The unweighted IMR were 48 and 46 deaths per 1000 live births for NDHS 2006 and NDHS 2011, respectively.

IMR for NDHS 2006 and 2011 (univariate analysis Tables 2 and 3)

Table 2.

Infant Mortality Rate by selected background characteristics in the population of Nepal, 2006 (Total: 5836)

| Community level Factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| NDHS 2006 | ||

| Variables | IMRa | P value |

| Region | 0.007 | |

| Far-Western | 60 | |

| Mid-Western | 65 | |

| Western | 30 | |

| Central | 34 | |

| Eastern | 35 | |

| Ecological Region (5836) | 0.003 | |

| Terai | 45 | |

| Hill | 30 | |

| Mountain | 78 | |

| Residence(5836) | 0.062 | |

| Urban | 30 | |

| Rural | 43 | |

| Maternal Antenatal care visits (2946) | 0.001 | |

| Yes | 17 | |

| No | 35 | |

| Delivery assisted (4494) | 0.013 | |

| Yes | 40 | |

| No | 74 | |

| Post-natal care (maternal) (734) | ||

| Yes | 21 | |

| No | 42 | |

| Socioeconomic level Factors | ||

| Maternal education (5836) | 0.012 | |

| No education | 48 | |

| Primary | 37 | |

| Secondary | 23 | |

| Partner’s education (5836) | 0.048 | |

| No education | 53 | |

| Primary | 41 | |

| Secondary | 37 | |

| Higher | 25 | |

| Religion (5836) | 0.383 | |

| Hindu | 43 | |

| Buddhist | 21 | |

| Muslim | 43 | |

| Kirat | 46 | |

| Christian/others | 51 | |

| Maternal literacy (5836) | 0.025 | |

| Able to read parts or whole sentence | 33 | |

| Unable to read at all | 48 | |

| Partner’s occupation (5836) | 0.379 | |

| Unemployed | 23 | |

| Employed | 42 | |

| Don’t Know | 22 | |

| Maternal occupation (5836) | 0.002 | |

| Unemployed | 22 | |

| Employed | 48 | |

| Biomass use (5836) | 0.001 | |

| Relatively non-polluting | 10 | |

| Relatively high polluting | 45 | |

| Wealth Index (5836) | 0.094 | |

| Poorest | 52 | |

| Poorer | 38 | |

| Middle | 51 | |

| Richer | 30 | |

| Richest | 28 | |

| Proximate level Factors | ||

| Maternal Factors | ||

| Mother’s age at Marriage (5836) | 0.063 | |

| <16 years | 46 | |

| 17-21 years | 38 | |

| >22 years | 22 | |

| Maternal age at Child Birth (5836) | 0.104 | |

| <16 years | 53 | |

| 17-21 years | 42 | |

| >22 years | 30 | |

| Mother marital status (5836) | 0.532 | |

| Married | 42 | |

| Widowed | 23 | |

| Divorced/Separated | 20 | |

| Decision making on own health care need (5836) | 0.007 | |

| Respondent alone | 24 | |

| Respondent & husband/partner/other | 37 | |

| Husband/Partner alone | 53 | |

| Someone else | 46 | |

| Decision making on own health care need (5836) | 0.007 | |

| Respondent alone | 31 | |

| Respondent & husband/partner/other | 56 | |

| Husband/Partner alone | 54 | |

| Someone else | 135 | |

| Maternal BMI (Asian) (5836) | 0.064 | |

| Underweight <18.49 | 46 | |

| Normal range 18.5-24.99 | 42 | |

| Overweight/obsess >=25.00 | 18 | |

| Infant Factors | ||

| Sex of Child (5836) | 0.419 | |

| Male | 39 | |

| Female | 44 | |

| Birth order (5836) | 0.004 | |

| 1st birth rank | 56 | |

| 2nd or 3rd birth | 31 | |

| >4th birth rank | 43 | |

| Preceding Birth Interval (5836) | 0.001 | |

| <=24 months | 57 | |

| >24 months | 26 | |

| Succeeding Birth Interval (5836) | 0.001 | |

| <=24 months | 131 | |

| >24 months | 26 | |

| Baby’s size at birth (4494) | 0.013 | |

| Very large/Larger than average | 34 | |

| Average | 37 | |

| Very small/Smaller than average | 64 | |

| Delivery Factors | ||

| Place of delivery (4496) | 0.016 | |

| Home | 45 | |

| Health Facility | 26 | |

| Deliver Assisted by (4494) | 0.001 | |

| Professional | 22 | |

| TBA | 40 | |

| Combined | 113 | |

| No assistance | 74 | |

| Mode of delivery (4494) | 0.045 | |

| Normal (non-caesarean section) | 42 | |

| Caesarean Section | 12 | |

| Currently breastfeeding (5836) | 0.001 | |

| Yes | 34 | |

| No | 58 | |

Number and weighted numbers of infant and their respective percentages were calculated before calculating the infant mortality rate (IMR)

Unit: Death per 1000 live births

Abbreviations: IMR infant mortality rate

aWeighted

Table 3.

Infant Mortality Rate by selected background characteristics in the population of Nepal, 2011 (Total: 5274)

| Community level Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDHS 2011 | ||||

| Variables | IMRa | P value | ||

| Region 5274) | 0.582 | |||

| Far-Western | 54 | |||

| Mid-Western | 42 | |||

| Western | 47 | |||

| Central | 43 | |||

| Eastern | 37 | |||

| Ecological Region (5274) | 0.001 | |||

| Terai | 41 | |||

| Hill | 44 | |||

| Mountain | 61 | |||

| Residence (5274) | 0.022 | |||

| Urban | 40 | |||

| Rural | 44 | |||

| Maternal Antenatal care visits (2994) | 0.036 | |||

| Yes | 20 | |||

| No | 38 | |||

| Delivery assisted (4183) | 0.085 | |||

| Yes | 42 | |||

| No | 78 | |||

| Post-natal care (maternal) (2994) | 0.189 | |||

| Yes | 18 | |||

| No | 26 | |||

| Socioeconomic level Factors | ||||

| Maternal education (5274) | 0.356 | |||

| No education | 49 | |||

| Primary | 43 | |||

| Secondary | 36 | |||

| Higher | 28 | |||

| Partner’s education (5274) | 0.010 | |||

| No education | 57 | |||

| Primary | 52 | |||

| Secondary | 35 | |||

| Higher | 21 | |||

| Religion (5274) | 0.617 | |||

| Hindu | 44 | |||

| Buddhist | 58 | |||

| Muslim | 30 | |||

| Kirat | 0 | |||

| Christian/others | 22 | |||

| Maternal literacy (5274) | 0.017 | |||

| Able to read parts or whole sentence | 36 | |||

| Unable to read at all | 53 | |||

| Paternal occupation (5274) | 0.905 | |||

| Unemployed | 0 | |||

| Employed | 44 | |||

| Don’t Know | 40 | |||

| Maternal occupation (5274) | 0.726 | |||

| Unemployed | 46 | |||

| Employed | 40 | |||

| Biomass use (5274) | 0.050 | |||

| Relatively non-polluting | 43 | |||

| Relatively high polluting | 29 | |||

| Others | 62 | |||

| Wealth Index (5274) | 0.610 | |||

| Poorest | 48 | |||

| Poorer | 44 | |||

| Middle | 45 | |||

| Richer | 45 | |||

| Richest | 30 | |||

| Proximate level Factors | ||||

| Maternal Factors | ||||

| Mother’s age at Marriage (5274) | 0.092 | |||

| <16 years | 49 | |||

| 17-21 years | 47 | |||

| >22 years | 30 | |||

| Maternal age at Child Birth (5274) | 0.466 | |||

| <16 years | 48 | |||

| 17-21 years | 39 | |||

| >22 years | 39 | |||

| Mother marital status (5274) | 0.871 | |||

| Married | 44 | |||

| Widowed | 47 | |||

| Divorced/Separated | 25 | |||

| Decision making on own health care need (5274) | 0.370 | |||

| Respondent alone | 45 | |||

| Respondent & husband/partner/other | 37 | |||

| Husband/Partner alone | 45 | |||

| Someone else | 55 | |||

| Decision making on own health care need (5274) | 0.455 | |||

| Respondent alone | 25 | |||

| Respondent & husband/partner/other | 29 | |||

| Husband/Partner alone | 59 | |||

| Someone else | 57 | |||

| Maternal BMI (Asian) (2557) | 0.493 | |||

| Underweight <18.49 | ||||

| Normal range 18.5-24.99 | ||||

| Overweight/obsess >=25.00 | ||||

| Infant Factors | ||||

| Sex of Child (5836) | 0.212 | |||

| Male | 47 | |||

| Female | 40 | |||

| Birth order (5836) | 0.272 | |||

| 1st birth rank | 51 | |||

| 2nd or 3rd birth | 40 | |||

| >4th birth rank | 39 | |||

| Preceding Birth Interval (5836) | 0.009 | |||

| <=24 months | ||||

| >24 months | ||||

| Succeeding Birth Interval (5836) | 0.001 | |||

| <=24 months | 151 | |||

| >24 months | 41 | |||

| Baby’s size at birth (4494) | 0.004 | |||

| Very large/Larger than average | 29 | |||

| Average | 41 | |||

| Very small/Smaller than average | 70 | |||

| Delivery Factors | ||||

| Place of delivery (4496) | 0.316 | |||

| Home | 46 | |||

| Health Facility | 38 | |||

| Deliver Assisted by (4494) | 0.437 | |||

| Professional | 39 | |||

| TBA | 45 | |||

| Combined | 36 | |||

| No assistance | 78 | |||

| Mode of delivery (4494) | 0.018 | |||

| Normal (non-caesarean section) | 45 | |||

| Caesarean Section | 11 | |||

| Currently breastfeeding (5836) | 0.002 | |||

| Yes | 36 | |||

| No | 57 | |||

Number and weighted numbers of infant and their respective percentages were calculated before calculating the infant mortality rate (IMR)

Unit: Death per 1000 live births

Abbreviations: IMR infant mortality rate

aWeighted

Tables 2 and 3 summarizes the IMR for the NDHS 2006 and 2011, respectively. The highest IMR was recorded in the Mountain region with 78 deaths per 1000 live births in 2006 and 61 deaths per 1000 live births in 2011. For both surveys, infants whose mothers had no education (74/1000 live births in NDHS 2006, 49/1000 live births in 2011), gave birth to her first child at the age younger than 16 years (53/1000 live births in 2006, 49/1000 live births in 2011) and did not have decision making authority on their own health care and money expenditure were found to have the highest IMR (Tables 2 and 3). In NDHS 2011, furthermore, IMR was also higher among infants who were born with preceding and succeeding birth interval of more than 24 months.

Factors associated with infant mortality (third stage multiple logistic regression analysis Tables 4 and 5)

Table 4.

Factors associated with infant mortality in Nepal in 2006 (unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio)

| NDHS 2006 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||

| COR | 95%CI | P value | AOR | 95%CI | P value | |||

| Community level factors | ||||||||

| Region | 0.002 | 0.022 | ||||||

| Far-Western | 1.770 | 1.019 | 3.074 | 0.043 | 1.498 | 0.903 | 2.483 | 0.116 |

| Mid-Western | 1.931 | 1.233 | 3.024 | 0.004 | 1.818 | 1.061 | 3.118 | 0.030 |

| Western | 0.866 | 0.446 | 1.682 | 0.669 | 0.810 | 0.387 | 1.696 | 0.573 |

| Central | 0.985 | 0.631 | 1.539 | 0.948 | 1.053 | 0.632 | 1.754 | 0.842 |

| Eastern | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Ecological Zone | 0.004 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Terai | 0.553 | 0.300 | 1.020 | 0.058 | 0.687 | 0.384 | 1.229 | 0.204 |

| Hill | 0.361 | 0.188 | 0.692 | 0.002 | 0.425 | 0.216 | 0.834 | 0.013 |

| Mountain | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Delivery Assisted | 0.014 | 0.012 | ||||||

| Some assistance | 0.517 | 0.360 | 0.874 | 0.014 | 0.496 | 0.288 | 0.855 | 0.012 |

| No assistance | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Socioeconomic Factors | ||||||||

| Maternal occupation | 0.003 | 0.016 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.466 | 0.284 | 0.767 | 0.003 | 0.537 | 0.324 | 0.889 | 0.016 |

| Employed | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Maternal Education | 0.008 | |||||||

| No education | 2.194 | 1.335 | 3.606 | 0.022 | ||||

| Incomplete | 1.677 | 0.878 | 3.205 | 0.116 | ||||

| primary/Primary Incomplete Secondary/Secondary | 1.000 | |||||||

| Paternal Education | 0.025 | |||||||

| No education | 2.199 | 1.240 | 3.898 | 0.007 | ||||

| Incomplete | 1.659 | 0.929 | 2.962 | 0.086 | ||||

| primary/Primary | 1.517 | 0.844 | 2.724 | 0.162 | ||||

| Incomplete Secondary/Secondary Higher | 1.000 | |||||||

| Maternal Literacy | 0.026 | |||||||

| Unable to read at all | 1.469 | 1.047 | 2.061 | 0.026 | ||||

| Able to read parts or whole sentence | 1.000 | |||||||

| Wealth Index | 0.049 | |||||||

| Poorest | 1.905 | 0.946 | 3.835 | 0.071 | ||||

| Poorer | 1.371 | 0.644 | 2.921 | 0.411 | ||||

| Middle | 1.845 | 0.847 | 4.019 | 0.122 | ||||

| Richer | 1.081 | 0.534 | 2.191 | 0.827 | ||||

| Richest | 1.000 | |||||||

| Biomass use | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Relatively non-polluting | 0.208 | 0.088 | 0.490 | 0.001 | 0.237 | 0.099 | 0.571 | 0.002 |

| Relatively high polluting | 1.000 | |||||||

| Proximate Factors | ||||||||

| Maternal factors | ||||||||

| Decision Making on own | 0.012 | |||||||

| health care need | ||||||||

| Respondent alone | 0.498 | 0.299 | 0.828 | 0.008 | ||||

| Respondent and | 0.796 | 0.514 | 1.234 | 0.306 | ||||

| Husband/partner/other | 1.143 | 0.767 | 1.701 | 0.509 | ||||

| Husband/Partner Alone/Someone Else | 1.000 | |||||||

| Decision Making capacity on money expenditure | 0.019 | |||||||

| Respondent alone | 0.203 | 0.071 | 0.581 | 0.003 | ||||

| Respondent and | 0.383 | 0.130 | 1.124 | 0.080 | ||||

| husband/partner/other | 0.370 | 0.140 | 0.980 | 0.046 | ||||

| Husband/Partner Alone | 1.000 | |||||||

| Someone Else | ||||||||

| Maternal BMI | 0.067 | |||||||

| Underweight | 2.693 | 1.161 | 6.246 | 0.021 | ||||

| Normal range | 2.459 | 1.131 | 5.345 | 0.023 | ||||

| Overweight/Obese | 1.000 | |||||||

| Mother’s age at marriage | 0.093 | |||||||

| <16 years | 2.208 | 1.016 | 4.797 | 0.045 | ||||

| 17–21 years | 1.803 | 0.851 | 3.819 | 0.123 | ||||

| >22 years | 1.000 | |||||||

| Mother’s age at child birth | 0.074 | |||||||

| <16 years | 1.854 | 1.080 | 3.184 | 0.026 | ||||

| 17–21 years | 1.449 | 0.941 | 2.231 | 0.092 | ||||

| >22 years | 1.000 | |||||||

| Infant factors | ||||||||

| Sex of child | 0.419 | |||||||

| Male | 0.875 | 0.633 | 1.211 | 0.419 | ||||

| Female | 1.000 | |||||||

| Birth order | 0.003 | |||||||

| >4th birth rank | 0.754 | 0.507 | 1.121 | 0.162 | ||||

| 2nd or 3rd birth | 0.535 | 0.375 | 0.764 | 0.001 | ||||

| 1st birth rank | 1.000 | |||||||

| Preceding Birth Interval | 0.001 | |||||||

| <=24 months | 2.240 | 1.592 | 3.153 | 0.001 | ||||

| >24 months | 1.000 | |||||||

| Succeeding Birth Interval | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||

| <=24 months | 5.653 | 3.729 | 8.569 | 0.001 | 6.694 | 3.757 | 11.92 | 0.001 |

| >24 months | 1.000 | 1.000 | 5 | |||||

| Baby’s size at birth | 0.027 | |||||||

| Very large/larger than | 0.516 | 0.304 | 0.877 | 0.015 | ||||

| average | 0.566 | 0.358 | 0.895 | 0.015 | ||||

| Average | 1.000 | |||||||

| Very small or smaller than average | ||||||||

| Delivery factors | ||||||||

| Place of delivery | 0.027 | |||||||

| Home | 1.781 | 1.108 | 2.863 | 0.017 | ||||

| Health Facility | 1.000 | |||||||

| Delivery assisted by | 0.001 | 0.016 | ||||||

| Professional | 0.276 | 0.127 | 0.599 | 0.001 | 0.374 | 0.148 | 0.944 | 0.038 |

| TBA | 0.522 | 0.312 | 0.873 | 0.014 | 0.619 | 0.306 | 1.254 | 0.182 |

| Combined | 1.593 | 0.639 | 3.972 | 0.315 | 2.027 | 0.710 | 5.782 | 0.185 |

| No assistance | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Mode of Delivery | 0.060 | |||||||

| Normal delivery | 3.520 | 0.945 | 13.108 | 0.060 | ||||

| Caesarean Section | 1.000 | |||||||

| Currently breastfeeding | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||

| No | 1.773 | 1.333 | 2.358 | 0.001 | 2.650 | 1.928 | 3.645 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

Abbreviations: COR crude odds ratio, AOR adjusted odds ratio

Table 5.

Factors associated with infant mortality in Nepal in 2011 (unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio)

| NDHS 2011 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||

| COR | 95% CI | P value | AOR | 95% CI | P value | |||

| Community level factors | ||||||||

| Region | 0.409 | |||||||

| Far-Western | 1.498 | 0.995 | 2.254 | 0.053 | ||||

| Mid-Western | 1.135 | 0.739 | 1.744 | 0.561 | ||||

| Western | 1.271 | 0.826 | 1.956 | 0.274 | ||||

| Central | 1.176 | 0.716 | 1.933 | 0.520 | ||||

| Eastern | 1.000 | |||||||

| Ecological Zone | 0.124 | |||||||

| Terai | 0.653 | 0.424 | 1.004 | 0.052 | ||||

| Hill | 0.712 | 0.484 | 1.046 | 0.083 | ||||

| Mountain | 1.000 | |||||||

| Delivery Assisted | 0.091 | 0.015 | ||||||

| Some assistance | 0.523 | 0.247 | 1.109 | 0.091 | 0.347 | 0.148 | 0.814 | 0.015 |

| No assistance | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Socioeconomic Factors | ||||||||

| Maternal occupation | 0.726 | |||||||

| Unemployed | 1.073 | 0.721 | 1.598 | 0.726 | ||||

| Employed | 1.000 | |||||||

| Maternal Education | 0.329 | |||||||

| No education | 1.754 | 0.706 | 4.361 | 0.225 | ||||

| Incomplete | 1.521 | 0.587 | 3.940 | 0.387 | ||||

| primary/Primary | 1.273 | 0.488 | 3.320 | 0.621 | ||||

| Incomplete Secondary/Secondary | 1.000 | |||||||

| Paternal Education | 0.004 | 0.010 | ||||||

| No education | 2.844 | 1.405 | 5.757 | 0.004 | 3.011 | 1.471 | 6.162 | 0.003 |

| Incomplete | 2.555 | 1.245 | 5.246 | 0.011 | 2.788 | 1.354 | 5.738 | 0.006 |

| primary/Primary | 1.676 | 0.815 | 3.446 | 0.159 | 1.756 | 0.909 | 3.389 | 0.093 |

| Incomplete Secondary/Secondary Higher |

1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Maternal Literacy | 0.017 | |||||||

| Unable to read at all | 1.481 | 1.072 | 2.046 | 0.017 | ||||

| Able to read parts or whole sentence | 1.000 | |||||||

| Wealth Index | 0.582 | |||||||

| Poorest | 1.620 | 0.926 | 2.835 | 0.091 | ||||

| Poorer | 1.466 | 0.781 | 2.750 | 0.233 | ||||

| Middle | 1.527 | 0.824 | 2.830 | 0.178 | ||||

| Richer | 1.497 | 0.766 | 2.924 | 0.237 | ||||

| Richest | 1.000 | |||||||

| Biomass use | 0.054 | |||||||

| Relatively non-polluting | 0.594 | 0.349 | 1.008 | 0.054 | ||||

| Relatively high polluting | 1.000 | |||||||

| Proximate Factors | ||||||||

| Maternal factors | ||||||||

| Decision Making on own health care need | 0.421 | |||||||

| Respondent alone | 0.823 | 0.470 | 1.441 | 0.495 | ||||

| Respondent and | 0.657 | 0.389 | 1.110 | 0.116 | ||||

| Husband/partner/other | 0.817 | 0.495 | 1.349 | 0.428 | ||||

| Husband/Partner Alone/ Someone Else |

1.000 | |||||||

| Decision Making capacity on money expenditure | 0.455 | |||||||

| Respondent alone | 0.429 | 0.062 | 2.985 | 0.391 | ||||

| Respondent and | 0.498 | 0.069 | 3.601 | 0.488 | ||||

| husband/partner/other | 1.042 | 0.132 | 8.208 | 0.969 | ||||

| Husband/Partner Alone Someone Else |

1.000 | |||||||

| Maternal BMI | 0.467 | |||||||

| Underweight | 0.603 | 0.251 | 1.447 | 0.256 | ||||

| Normal range | 0.693 | 0.356 | 1.350 | 0.280 | ||||

| Overweight/Obese | 1.000 | |||||||

| Mother’s age at marriage | 0.490 | |||||||

| <16 years | 1.230 | 0.656 | 2.307 | 0.517 | ||||

| 17–21 years | 1.001 | 0.543 | 1.845 | 0.999 | ||||

| >22 years | 1.000 | |||||||

| Mother’s age at child birth | 0.127 | |||||||

| <16 years | 1.623 | 0.933 | 2.824 | 0.086 | ||||

| 17–21 years | 1.576 | 1.008 | 2.465 | 0.046 | ||||

| >22 years | 1.000 | |||||||

| Infant factors | ||||||||

| Sex of child | 0.213 | |||||||

| Male | 1.193 | 0.903 | 1.577 | 0.213 | ||||

| Female | 1.000 | |||||||

| Birth order | 0.273 | |||||||

| >4th birth rank | 1.312 | 0.875 | 1.968 | 0.187 | ||||

| 2nd or 3rd birth | 1.009 | 0.659 | 1.545 | 0.967 | ||||

| 1st birth rank | 1.000 | |||||||

| Preceding Birth Interval | 0.001 | 0.038 | ||||||

| <=24 months | 2.121 | 1.459 | 3.084 | 0.001 | 1.941 | 1.036 | 3.635 | 0.038 |

| >24 months | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Succeeding Birth Interval | 0.001 | 0.003 | ||||||

| <=24 months | 4.162 | 2.579 | 6.717 | 0.001 | 3.215 | 1.505 | 6.866 | 0.003 |

| >24 months | 1.000 | |||||||

| Baby’s size at birth | 0.003 | 0.025 | ||||||

| Very large/larger than | 0.399 | 0.233 | 0.684 | 0.001 | 0.170 | 0.047 | 0.624 | 0.008 |

| average | 0.569 | 0.365 | 0.886 | 0.013 | 0.717 | 0.333 | 1.546 | 0.394 |

| Average Very small or smaller than average |

1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Delivery factors | ||||||||

| Place of delivery | 0.316 | |||||||

| Home | 1.230 | 0.820 | 1.846 | 0.316 | ||||

| Health Facility | 1.000 | |||||||

| Delivery assisted by | 0.291 | |||||||

| Professional | 0.482 | 0.224 | 1.038 | 0.062 | ||||

| TBA | 0.556 | 0.255 | 1.215 | 0.141 | ||||

| Combined | 0.448 | 0.126 | 1.597 | 0.215 | ||||

| No assistance | 1.000 | |||||||

| Mode of Delivery | 0.029 | 0.022 | ||||||

| Normal delivery | 4.073 | 1.152 | 14.399 | 0.029 | 4.423 | 1.664 | 3.379 | 0.022 |

| Caesarean Section | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Currently breastfeeding | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||||||

| No | 1.618 | 1.190 | 2.202 | 0.002 | 2.382 | 1.674 | 3.390 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

Abbreviations: COR crude odds ratio, AOR adjusted odds ratio

Tables 4 and 5 summarizes the identified factors associated with infant mortality for the NDHS 2006 and 2011, respectively. For NDHS 2006, among community level factors, the study found that infants born in the Mid-Western region had 82% higher odds of dying; the odds of death for infants born in Hilly region was reduced by 57% compared to those born in the Mountain region; and infants born to mothers who received some assistance during delivery had reduced the odds of death by 50% (Tables 4 and 5). Within only the group of socioeconomic level factors, the study revealed that infants born to unemployed mothers or born in families using relatively non-polluting cooking fuel had lowered odds of death (Tables 4 and 5). Considering proximate level factors specifically, infants who were born with a shorter than 24 months succeeding birth interval, and not breastfed were found to have significantly higher odds of death. On the other hands, the odds of mortality for infants who were delivered by the assistance of professionals reduced significantly.

For NDHS 2011, delivery assistance was the only community level factor that was significantly associated with infant mortality (Tables 4 and 5). Assistance during delivery (AOR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.15–0.81, p = 0.015) was found to have protective effect for infants. For socioeconomic level factors, only paternal education was found to be significant negatively associated with infant mortality (p = 0.010). Regarding proximate level determinants, only some infant and delivery factors were found to be strongly associated with infant mortality (Tables 4 and 5). Infants who were born through normal delivery modes; who were born with a preceding or a succeeding interval of less than 24 months; who were born very small or smaller than average; or who were not breastfed were found to have significant higher odds of dying compared to their counterparts.

Final factors associated with infant mortality (final overall hierarchical multiple logistic regression analysis Table 6)

Table 6.

Overall significant adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for IMR in 2006 and 2011

| Variables | 2006 | 2011 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95%CI | P value | AOR | 95%CI | P value | |||

| Ecological Zone | 0.004 | |||||||

| Terai | 0.687 | 0.384 | 1.229 | 0.204 | ||||

| Hill | 0.425 | 0.216 | 0.834 | 0.013 | ||||

| Mountain | 1.000 | |||||||

| Preceding Birth Interval | 0.022 | |||||||

| <=24 months | 1.941 | 1.036 | 3.635 | 0.022 | ||||

| >24 months | 1.000 | |||||||

| Succeeding Birth | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Interval | 6.656 | 3.736 | 11.859 | 0.001 | 3.215 | 1.505 | 6.866 | 0.002 |

| <=24 months >24 months |

1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Baby’s size at birth | 0.015 | |||||||

| Very large/larger than | 0.170 | 0.047 | 0.624 | 0.008 | ||||

| average | 0.717 | 0.333 | 1.546 | 0.394 | ||||

| Average Very small or smaller than average |

1.000 | |||||||

| Delivery assisted by | 0.016 | |||||||

| Professional | 0.370 | 0.144 | 0.951 | 0.039 | ||||

| TBA | 0.589 | 0.277 | 1.254 | 0.168 | ||||

| Combined | 2.050 | 0.678 | 6.198 | 0.201 | ||||

| No assistance | 1.000 | |||||||

| Currently Breastfeeding | 0.044 | |||||||

| No | 1.618 | 1.014 | 2.580 | 0.044 | ||||

| Yes | 1.000 | |||||||

AOR model for 2006 and 2011 was obtained after including all three final models (community, socioeconomic and proximate) through backward elimination

Abbreviations: COR crude odds ratio, AOR adjusted odds ratio

The final overall model identified ecological region, succeeding birth interval, currently breastfeeding and type of delivery assistance as the significant predictors affecting infant mortality for NDHS 2006 (Table 6). Infants who were born in Mountain region; who were born with a succeeding birth interval of less than 24 months (AOR = 6.66, 95% CI: 3.74–11.86, p = 0.001) and who were not breastfed (AOR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.01–2.58, p = 0.044) had significantly higher odds of dying. However, the odds of mortality were reduced odds by 63% (AOR = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.14–0.95, p = 0.039) for those infants who were delivered through the assistance of professionals (doctors, nurses and midwives) (AOR = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.14–0.95, p = 0.039).

For NDHS 2011, three (all proximate level) infant factors were identified by the final model. Infants born with preceding birth intervals (AOR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.04–3.64, p = 0.022) or succeeding birth intervals (AOR = 3.22, 95% CI: 1.51–6.87, p = 0.002) less than 24 months had significant higher odds of mortality compared to their counterparts. In addition, infants who were born very large or larger than average had significantly reduced odds (AOR = 0.17, 95%CI: 0.05–0.62, p = 0.008) of dying compared to those born very small or smaller than average.

Discussion

This study explored and compared the associated risk factors of infant mortality using evidence from NDHS 2006 and 2011. The bivariate and multivariate regression models of this study found a number of significant predictors (Tables 4 and 5); however, they could not retain their significance in the final model (Table 6). Without losing any important association, the following discussion will be mainly based on the findings revealed by the final hierarchical overall model, which was built with a backward elimination regression approach with an inclusion of all possible significant predictors obtained from previous models.

Findings from NDHS 2006 and 2011

Based on the final overall model (Table 6), infants born in hilly ecological region, delivery assistance by professionals and current breastfeeding status appeared as protective factors against infant mortality while succeeding birth interval of less than 24 months (2 years) was identified to be associated with the increased risk of infant mortality in the both study periods. Hence, both proceeding and succeeding birth intervals of less than 24 months (2 years) were associated with a significant increased risk of infant death, however, very large/larger than average birth size was negatively associated with infant mortality.

Comparisons of the findings between 2006 and 2011 NDHS

Only succeeding birth interval was the common factor for both surveys (Table 6). Ecological region, type of delivery assistance and current breastfeeding status were found to have a significant impact on infant mortality only in 2006 survey however they didn’t show their significant impacts in 2011 survey. Preceding birth interval and baby birth size emerged as new significant factors in 2011 survey. Interestingly, different levels factors (community level, proximate level factors (delivery and infant) affected infant mortality in 2006 while in 2011 only proximate level factors, more specifically, infant factors played an important role on infant mortality (See Table 6). No socio-economic level or maternal factors were found to be significant for both surveys based on the final overall model.

Discussion of the findings between 2006 and 2011 NDHS

Ecological region

In our study, ecological region was found as a significant predictor for 2006 survey only, its less important impact for 2011 survey could be attributed to improved transportation, availability of health care facilities and increased human resources in health, although not reach to the expected level, in Nepal [23]. Dev [4] reported that infants born in Mountain region in Nepal had 42% increased odds of mortality within the infancy period compared to those in the Terai region. Infants born in Hill and Terai had significantly achieved 55% reduction in mortality between 1996 and 2011 compared to those born in the Mountain region [5]. Based on the findings of Baral, Lyones, Skinner and van Teijlingen [24] mothers from the central and Terai region were more likely to utilise health care services compared to those from Far Western region and Mountain areas. The study further reveals that the majority of people living in mountainous zone (far and mid-western region) had lower access to healthcare services and had relatively poor standard of living. Furthermore, access to health care facilities is limited due to poor transportation and difficult geographical terrain [10]. Human development index (HDI) of the people living in mountainous Mid-Western and Far-Western regions was 0.398, extensively lower compared to those living in Kathmandu valley, which was 0.622 in 2011 [25]. Another study reported an insignificant association between regional variation and infant mortality [26]. Some other studies have identified that eco-developmental region was significantly associated with infant mortality [4, 7, 18].

Delivery factors

Regarding health service coverage, delivery assistance showed its important effect when only community level factors were adjusted and it lost its significance in the final overall model (Tables 4 and 5). A similar study in Indonesia also found delivery assistance as a protective factor for infant mortality [26]. Unassisted births had a greater risk of infant mortality compared to those who had some assistance [24]. In Nepal, access to delivery services especially comprehensive obstetric care is inadequate because of limited human resources and extreme geographical locations [24]. As a consequence, the majority of infants who are born with birth complications like birth asphyxia and prematurity do not get timely treatment which leads to their death [27]. Limited access to caesarean section facility could be a possible explanation for higher infant mortality among those normally delivered [13].

The final overall model confirmed that type of delivery assistance was a significant predictor (Table 6) for 2006 survey and it failed to find the similar significant association for NDHS 2011. This could be attributed to more implementations of maternal and child health related policy and strategies during 2005 to 2009 [27]. Those infants who were delivered with professional assistance (doctors, nurses and midwives) were less likely to die. Professional assistance during delivery was found to be a protective predictor against the infant mortality. A similar study conducted in Indonesia also reported consistent findings with this study [28]. In addition, mothers living in urban areas were advantaged with delivery assistance reporting that 51% of urban births were assisted by professionals while only 14% of births were assisted in rural areas [24]. Those infants born to mothers who were able to make decisions on her own had reduced odds of infant mortality compared to those whose decisions were made by someone else. Some studies reported significant association between infant mortality and mother’s decision-making capacity [29, 30]. Nonetheless, a cross-sectional study conducted in India could not find any significant association, although mothers’ decision-making capacity was found to affect the quality of child care and access to health information [31]. Neupane and Doku [32] and several other studies also had consistent findings with our result [20, 28]. Nepal government endorsed a skilled birth attendant policy in 2006 and maternal incentive schemes in 2005 to encourage women to utilise maternity care services [13, 27]. The policies implemented during that period increased service coverage in 2011 compared to 2006 to some extent [13]. Our study further identified that IMR was higher among those who did not utilise the available facilities. Research has reported that geographical difficulties and poor transportation are possible barriers for the underutilisation of maternal health services in rural areas [20, 24, 28].

Although it lost its significance in the final overall model, normal delivery was identified to be associated with an increased likelihood of infant death for 2011 survey. Contrastingly, Titaley, Dibley and Roberts found a lower risk of mortality among infants who were delivered normally compared to those delivered through caesarean section [26]. However, the finding was not significant in their study. In addition, another study conducted by the same authors reported different findings that an increased risk of dying among neonates born through normal delivery [26]. In Nepal, access to delivery services especially comprehensive obstetric care is inadequate because of limited human resources and extreme geographical locations [24]. As consequence, the majority of infants who are born with birth complications like birth asphyxia and prematurity do not get timely treatment which leads to their death [27]. Limited access to caesarean section facility could be a possible explanation for higher infant mortality among those normally delivered [13]. Similar to ours, other studies also could not find any significant association between maternal age and infant mortality [26, 32].

Birth intervals

Interestingly, none of the maternal factors were found to be significant predictors of infant mortality however, infant factors played very important role on infant survival, particularly for 2011 survey. Birth intervals (preceding and succeeding)1 were positively correlated with infant survival (Table 6). Those infants born to a short (less than 24 months) preceding or succeeding birth interval were at higher risk of mortality compared to those born with a longer birth interval (more than 24 months). Several epidemiological studies conducted in developing countries supported the findings for birth interval and infant mortality [20, 26, 33]. Spacing between pregnancies is an influential factor of infant mortality. A study illustrated that women with a short birth interval between pregnancies do not get sufficient time to maintain their normal body structure and nutritional status [26]. The birth spacing between pregnancies strongly correlates with child survival in Nepalese population and other developing countries [12]. According to the Indonesian study, a short birth interval increased the odds of infant death during the neonatal period [34]. Those infants born with less than 2 years (<24 months) preceding or succeeding birth interval had a greater risk of dying compared to those born with more than 2 years’ interval.

Baby birth size

Another known significant predictor of infant mortality was baby’s size at birth in literature and this study confirmed that those infants who were born with very large or larger than average size at birth had significantly lower odds of dying compared to those born with very small or smaller than average birth size. A study conducted in India among neonates revealed that mortality was highest among newborns whose birth size was smaller than average [35]. Another epidemiological study also found a similar association reporting lower odds of dying among infants born with average or larger than average birth sizes [36].

Breastfeeding

This study also confirmed that current breastfeeding (during the time of survey) was a protective predictor for infant survival. Those infants who were not currently being breastfed had 2.65 times higher risk of dying compared to their counterparts. Studies have identified that breastfed children were more likely to be protected from several infections and mortality [37]. A meta-analysis conducted between 1966 and 2009 found breastfeeding to be protective against Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). The same study further reported that infants who were breastfed for any duration were more likely to be protected against mortality [38]. Khanal, Sauer and Zhao [37] identified breastfeeding as one of the protective factor for infant survival. Other researchers further identified consistent findings that breastfeeding reduces the risk of major infections as well as SIDS during infancy [38, 39].

Other important factors

Several policies like Maternal Incentive Scheme and Free Delivery Services, addressing transportation and health service coverage issues related to maternal and child health were implemented during that period (2006 and 2011), which could be a potential explanation for the insignificant impact of eco-developmental regions on infant mortality [27]. Our study identified significantly higher odds of infant mortality among those infants whose mothers did not receive antenatal services, however, the association lost significance after controlling for all other community level factors (Tables 4 and 5).

Based on the final overall model, paternal education and maternal literacy status were not found to be significantly associated with infant mortality in both surveys. In Nepalese patriarchal society, the father contributes the major input to family’s economic status and dominates decision making. Hence, the significant association between infant mortality and father’s education indicated a protective effect on infant’s survival [40]. Similar studies conducted in Indonesia and in Nepal reported insignificant association between maternal educational status and infant mortality [32, 34], which is consistent with our findings. A study conducted in Nepal found wealth index as one of the significant socioeconomic predictors of infant mortality [20]. However, our study found an insignificant association between the wealth index and infant mortality. A consistent finding was also reported by one of the survival analysis conducted in Nepal [34]. Although odds of dying for those infants born to families using relatively non-polluting cooking fuel was lower compared to their counterparts, biomass use was found not to be associated with infant mortality for NDHS 2011 in our study [41, 42].

To sum up, this study used the data from two DHS period (2006 and 2011) to identify and compare the significant predictors of infant mortality in the Nepalese context. Succeeding birth internal was the only factor which was common in both these periods. Other factors significant in either of these period were hilly ecological region, delivery assistance by professionals, current breastfeeding status and birth size. Most of the study findings are consistent with the existing literature from around the world in infant mortality. This study thus helps to establish these factors in the Nepalese context. Additionally, this study suggest variation in the factors significantly affecting infant mortality between the two DHS periods such as birth size which was significant in 2011 but not in 2006. Study incorporating the data from the upcoming NDHS 20016 might provide more clarity regarding this.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study found four factors in NDHS 2006 and three factors in NDHS 2011 that were significantly associated with infant mortality based on the final overall model. For NDHS 2006, infants who were born in hilly region; who were born with a succeeding birth interval of ≥ 24 months; who were delivered with professional assistance; and who were being breastfed, had lower odds of dying. For NDHS 2011, infants who were born with a preceding or succeeding birth interval of >24 months; and who were born with a larger or larger than average size had significant lower odds of dying. Succeeding birth interval was the only common factor significantly associated with infant mortality for both the study periods.

Infant mortality is still significantly high in Nepal based on the two nationally representative survey data, NDHS 2006 and NDHS 2011, implying that there is an urgent need for the country to implement more targeted public health interventions which can accelerate the decrease in infant mortality with an aim to improve the infant survival rate. The study revealed that geographical difficulties and service coverage had influenced infant mortality; therefore, it is essential to increase the access and availability of health care services in hard-to-reach areas. Inter-sectoral collaboration between health and other sectors in areas such as parental literacy and indoor air pollution can bring better result. We recommend that efforts on increasing the number of health facilities along with skilled health care providers, and providing accessible basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care should be encouraged. Furthermore, this study found that birth interval was the strongest predictor in both surveys. Therefore, intervention programs should particularly focus on addressing birth spacing using efficient strategies like strengthening of family planning programs in the community. Similarly, study incorporating the data from the upcoming NDHS 2016 is recommended to establish the significant predictors in the Nepalese context.

Strengthens and limitations of the study

One of the strengths of this study is the use of well-documented data from the NDHS 2006 and 2011, which are nationally representative surveys with a high response rate (99%). Questionnaires were internationally validated and used standardised methods of data collection with larger sample size. Both surveys had a large sample size which allowed for the inclusion of a wide range of variables that are associated with infant mortality and permitted insight examination of multiple predictors, possible interactive association and confounding effects. Furthermore, this study categorised a wide array of potential factors into three different groups under conceptual framework including: community, socioeconomic and proximate level factors, and helped to further identify the most significant factors within and between different levels. This study used complex sample analysis, which accounts for the sampling weight due to multistage stratified sampling used in both surveys, to obtain accurate estimation for standard errors and confidence intervals. This study compared and examined the difference in factors associated with infant mortality in Nepal between the 2006 and 2011 national surveys, which has not been reported yet. Hence, the comparison provides evidence-based recommendations for further studies, interventions planning and policy decisions making.

As DHS are derived from cross-sectional surveys, such data might be subjected to recall bias. The association of infant mortality with factors drawn from statistical analysis might lack a temporal relationship because of the nature of the study design. Furthermore, this study only included singleton live-births 5 years preceding the surveys. Another limitation of this study is regarding small number of observations in some categories defined by several independent variables, where recoding/regrouping was not possible. These sparse observations caused some computational difficulties in regression analysis and some important variables such as maternal antenatal visit, birth order, maternal age and BMI etc. might have been missed as significant predictors in this study.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Chhavi Raman Chaualgain, Rijwana Chaulagain, Dr. Helman Alfanso, Josephine C. Agu and Vishnu Khanal for their generous support with the study and/or with the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

NDHS data is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

RL conducted the whole study including data analysis and wrote the first draft of this manuscript. YZ supervised during the whole study. YZ, SP and EO contributed to the revision and final draft of this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ information

RL was studying Master of Public Health in the Curtin University, Western Australia while conducting this study. RL is now full time employee of Maltesr International in Nepal as Health Coordinator.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee, (Approval number: RDHS-34-15). Permission to use the data sets and further analysis was also obtained from Macro International (research agency).

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- AOR

Adjusted odd ratio

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- COR

Crude odd ratio

- DHS

Demographic and health survey

- HDI

Human development index

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IMR

Infant mortality rate

- MDG

Millennium development goal

- NDHS

Nepal demographic and health survey

- PQLI

Physical quality of life index

- SIDS

Sudden infant death syndrome

Footnotes

Preceding: Before Succeeding: Subsequent.

Contributor Information

Reeta Lamichhane, Email: rcsindhu@gmail.com.

Yun Zhao, Email: Y.Zhao@exchange.curtin.edu.au.

Susan Paudel, Email: replysusan1@gmail.com.

Emmanuel O. Adewuyi, Email: e.adewuyi@postgrad.curtin.edu.au

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Statistical Information System (WHOSIS) WHO; 2014 [Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/indicatordefinitions/en/.

- 2.Reidpath DD, Allotey P. Infant mortality rate as an indicator of population health. J epidemiol community health. 2003;57(5):344–346. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storeygard A, Balk D, Levy M, Deane G. The global distribution of infant mortality: a subnational spatial view. Popul space place. 2008;14(3):209–229. doi: 10.1002/psp.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dev R. Topographical differences of infant mortality in Nepal: demographic and health survey 2011: Doctoral dissertation. USA: University of Washington; 2014.

- 5.Sreeramareddy C, Kumar H, Sathian B. Time trends and inequalities of under-five mortality in Nepal: a secondary data analysis of four demographic and health surveys between 1996 and 2011. Plos one. 2013; 8 (11) DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0079818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hajizadeh M, Nandi A, Heymann J. Social inequality in infant mortality: what explains variation across low and middle income countries? Social science & medicine. 2014; 101 (0):36–46. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Sartorius BK, Sartorius K. Global infant mortality trends and attributable determinants—an ecological study using data from 192 countries for the period 1990–2011. Popul health metrics. 2014;12(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12963-014-0029-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Streatfield P, Khan W, Bhuiya A, Hanifi S, Alam N, Ouattara M, et al. Cause-specific childhood mortality in Africa and Asia: evidence from INDEPTH health and demographic surveillance system sites. Global health action. 2014; 7 DOI:10.3402/gha.v7.25363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Murray CJL, Laakso T, Shibuya K, Hill K, Lopez AD. Can we achieve millennium development goal 4? New analysis of country trends and forecasts of under-5 mortality to 2015. The lancet. 2007 [cited 2007/9/28/]; 370 (9592):1040–1054. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61478-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Adhikari R, Podhisita C. Household headship and child death: evidence from Nepal. BMC int health hum rights. 2010;10(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deepak Paudel AT, Purusotam Raj Shedain, Bhuwan Paudel,. Trends and determinants of neonatal mortaltiy in Nepal: further analysis of demographic and health survey 2001–2011. The DHS Program 2013 [cited March 2013]; http://www.dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fa75-further-analysis.cfm.

- 12.Thapa S. Declining trends of infant, child and under-five mortality in Nepal. J trop pediatr. 2008;54(4):265–268. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) [Nepal]. Nepal demographic and health survey, 2011, 2012. kathmandu, Nepal: Naiotnal Planning Commission;

- 14.Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) [Nepal]. Nepal demographic and health survey, 2006, 2007. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health and Population, New ERA, and Macro International Inc.;

- 15.MENA Report . India : infant mortality rate in India. London: Albawaba (London) Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moniruzzaman Uzzal. Bangladesh exceeds MDG target for reducing child mortality. Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2014 [cited 27 March, 2014]. Available from: http://www.dhakatribune.com/development/2014/mar/23/bangladesh-exceeds-mdg-target-reducing-child-mortality.

- 17.Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, Mooney MD, Levitz CE, Schumacher AE, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2013;384(9947):957–979. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60497-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paudel Deepak, Thapa Anil, Shedain Purusotam Raj, Paudel Bhuwan. Trends and determinants of Neonatal mortaltiy in Nepal: further analysis of demographic and health survey 2001–2011. The DHS Program 2013 [cited March 2013]; http://www.dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fa75-further-analysis.cfm.

- 19.Pandey JP, Dhakal MR, Karki S, Poudel P, Pradhan MS. Maternal and child health in Nepal: the effects of caste, ethnicity, and regional identity: further analysis of the 2011 Nepal demographic and health survey. 2013. http://preview.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FA73/FA73.pdf. Accessed Mar 2013.

- 20.Khadka KB, Lieberman LS, Giedraitis V, Bhatta L, Pandey G. The socio-economic determinants of infant mortality in Nepal: analysis of Nepal demographic health survey, 2011. BMC pediatr. 2015;15(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0468-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fabic MS, Choi Y, Bird S. A systematic review of demographic and health surveys: data availability and utilization for research. Bull world health organ. 2012;90(8):604–612. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.095513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosley WH, Chen LC. An analythical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. Bull world health organ. 2003;81(2):140–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malla D, Giri K, Karki C, Chaudhary P. Achieving millennium development goals 4 and 5 in Nepal. BJOG. 2011;118(s2):60–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baral Y, Lyones K, Skinner J, van Teijlingen E. Maternal health services utilisation in Nepal: progress in the new millennium. Health sci j. 2012;6(4):618–633. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Government of Nepal. Nepal Human Development Index Report 2014, 2014. Kathmandu, Nepal:

- 26.Titaley CR, Dibley M, Agho K, Roberts C, Hall J. Determinants of neonatal mortality in Indonesia. BMC public health. 2008; 8 DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-8-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Bhadari T, Dangal G. Maternal mortality: paradigm shift in Nepal. Nepal j obstet gynaecol. 2014;7(2):3–8. doi: 10.3126/njog.v7i2.11132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Titaley CR, Dibley MJ, Roberts CL. Type of delivery attendant, place of delivery and risk of early neonatal mortality: analyses of the 1994–2007 Indonesia demographic and health surveys. Health policy plan. 2012;27(5):405–416. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adhikari R, Sawangdee Y. Influence of women’s autonomy on infant mortality in Nepal. Reprod health. 2011;8(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fantahun M, Berhane Y, Wall S, Byass P, Högberg U. Women’s involvement in household decision‐making and strengthening social capital—crucial factors for child survival in Ethiopia. Acta paediatr. 2007;96(4):582–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy SNMAM. Multi-level determinants of regional variations in infant mortality in India: a state level analysis. Int j child health hum dev. 2013;6(2):173–91. Available from: https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-3502791901/multi-level-determinants-of-regional-variations-in.

- 32.Neupane S, Doku DT. Neonatal mortality in Nepal: a multilevel analysis of a nationally representative. J epidemiol glob health. 2014;4(3):213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiferaw Y, Zinabu M, Abera T. Determinant of infant and child mortality in Ethiopia. SSRN Working Paper Series. 2012; DOI:10.2139/ssrn.2188355.

- 34.Chin B, Montana L, Basagaña X. Spatial modeling of geographic inequalities in infant and child mortality across Nepal. Health place. 2011;17(4):929–936. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar C, Singh PK, Rai RK, Singh L. Early neonatal mortality in India, 1990–2006. J community health. 2013;38(1):120–130. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sovio U, Dibden A, Koupil I. Social determinants of infant mortality in a historical Swedish cohort. Paediatr perinat epidemiol. 2012;26(5):408–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khanal V, Sauer K, Zhao Y. Exclusive breastfeeding practices in relation to social and health determinants: a comparison of the 2006 and 2011 Nepal demographic and health surveys. BMC public health. 2013;13(1):958. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hauck FR, Thompson JM, Tanabe KO, Moon RY, Vennemann MM. Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):103–110. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rijal P, Agrawal A, Pokharel H, Pradhan T, Regmi M. Maternal mortality: a review from eastern Nepal. Nepal j obstetrics gynaecol. 2014;9(1):33–36. doi: 10.3126/njog.v9i1.11185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mondal N, Hossain K, Ali K. Factors influencing infant and child mortality: a case study of Rajshahi district, Bangladesh. J hum ecol. 2009;26(1):31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devakumar D, Semple S, Osrin D, Yadav SK, Kurmi OP, Saville NM, et al. Biomass fuel use and the exposure of children to particulate air pollution in southern Nepal. Environ int. 2014;66:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pope DP, Mishra V, Thompson L, Siddiqui AR, Rehfuess EA, Weber M, Bruce NG. Risk of low birth weight and stillbirth associated with indoor air pollution from solid fuel use in developing countries. Epidemiologic reviews. 2010:mxq005. http://epirev.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2010/04/08/epirev.mxq005.short. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

NDHS data is available upon request to the corresponding author.