Abstract

Cluster headache is a relatively rare headache disorder, typically characterized by multiple daily, short-lasting attacks of excruciating, unilateral (peri-)orbital or temporal pain associated with autonomic symptoms and restlessness. To better understand the pathophysiology of cluster headache, we used RNA sequencing to identify differentially expressed genes and pathways in whole blood of patients with episodic (n = 19) or chronic (n = 20) cluster headache in comparison with headache-free controls (n = 20). Gene expression data were analysed by gene and by module of co-expressed genes with particular attention to previously implicated disease pathways including hypocretin dysregulation. Only moderate gene expression differences were identified and no associations were found with previously reported pathogenic mechanisms. At the level of functional gene sets, associations were observed for genes involved in several brain-related mechanisms such as GABA receptor function and voltage-gated channels. In addition, genes and modules of co-expressed genes showed a role for intracellular signalling cascades, mitochondria and inflammation. Although larger study samples may be required to identify the full range of involved pathways, these results indicate a role for mitochondria, intracellular signalling and inflammation in cluster headache.

Cluster headache is a relatively rare brain disorder, typically characterized by multiple-daily, short-lasting (15–180 min) attacks of excruciating, unilateral, (peri-)orbital or temporal headache associated with ipsilateral facial autonomic symptoms and restlessness1,2. In up to 90% of patients, attacks strike in defined periods of several weeks to months alternating with attack-free periods of several months to years (episodic cluster headache). In the remaining 10%, attacks keep on recurring without attack-free periods longer than a month (chronic cluster headache). The lifetime prevalence is 0.05–0.4%3,4 and the male-to-female ratio 4.4: 14,5.

The etiology of cluster headache is unknown. Triggered by neuroimaging data and the circadian and annual rhythmicity of attacks and periods of cluster headache, an important role has been postulated for the hypothalamus and the sleep-, pain-, and autonomic function-modulating, hypothalamic neuropeptide hypocretin (orexin)6,7,8,9. Activation of the trigeminovascular system and possibly associated inflammatory processes have been implicated in causing and aggravating the pain10,11,12. Although family members of cluster headache patients seem to be at increased risk of developing cluster headache3, indicating contribution of genetic factors, genetic studies into cluster headache have been largely unsuccessful13,14. Some studies suggested involvement of the HCRTR2 gene that encodes the hypocretin type 2 receptor, but this finding could not be confirmed in other studies15. A main complicating factor for genetic association studies in cluster headache is that they included at best only a few hundred cases rather than the many thousands which are usually required for such studies.

Gene expression profiling is an alternative approach to identify disease genes and pathways requiring only several tens of cases. However, as well-characterized human post-mortem brain samples are difficult to obtain in these numbers, gene expression profiling studies for brain disorders have been mostly performed in whole blood samples. Promising results were obtained for epilepsy16 and psychiatric17,18 and neurodegenerative disorders19,20,21,22,23, with gene expression differences similar to those observed in post-mortem brain material19,20,21,22,23. Two gene expression profiling studies using microarray technology have been performed in cluster headache24,25. In one, whole blood gene expression levels from three cluster headache patients and three controls were compared; 90 differentially expressed genes were identified, including upregulated calcium-binding proteins suggesting a possible role for non-infectious inflammation25. In the other study, immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines from eight lithium-responsive cluster headache patients and 10 controls were compared26. Over 1,100 differentially expressed genes were identified of which many are involved in endoplasmic reticulum protein processing25. Remarkably, only 10 genes overlapped between both studies, of which six showed differential expression when comparing the same patient outside and during a cluster period in-between attacks24. The limited overlap between these studies is likely explained by the small sample sizes and differences in gender, age, medication, tissues, and other factors.

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) is a deep sequencing-based technique that is more robust and detects a wider range of transcripts than microarray technology26. In the present study, we used RNA-seq to compare whole blood gene expression profiles of 39 well characterized participants with cluster headache (19 episodic; 20 chronic) and 20 matched controls. Besides analysing the RNA-seq data per gene, a clustering approach was applied to group genes into modules based on co-expression and study the association of these modules with cluster headache. Special attention was given to hypocretin-related genes and genes previously found to be differentially expressed in cluster headache.

Results

Whole blood gene expression profiles of 40 participants with cluster headache (20 episodic; 20 chronic) and 20 controls were obtained using an RNA-seq approach. The RNA-seq data of one participant with episodic cluster headache were excluded because of inferior RNA-seq data quality (Table 1). In participants with cluster headache, blood samples were collected outside attacks; in 25/39 participants within one day from the last attack (10 episodic and 15 chronic patients), in 8/39 participants between one to seven days (4 episodic and 4 chronic patients), and in the remaining 6 within 94 days (5 episodic and 1 chronic patient). Participants with episodic cluster headache were studied within a “cluster period” (i.e. preventative treatment is still necessary because when lowering the treatment the patient perceives upcoming, or first symptomatology, of attacks). There were no differences between participants with episodic and chronic cluster headache for attack frequency and medication use in the month prior to sampling. Leukocyte counts did not differ between participants with cluster headache and controls (Supplementary Table 1). On average 23.9 million high-quality paired-end sequencing reads were obtained per sample (range: 21.4–30.2 million). On average 91% (range: 88–93%) of reads could be uniquely aligned to the genome, of which 77% (range: 71–82%) to known exons. A total of 13,416 genes with sufficiently high expression (after removal of genes with<1 count per million (CPM) in a minimum of 15 samples) were present in our dataset.

Table 1. Demographics of the experimental groups used in the study.

| Controls | Episodic CH | Chronic CH | P-value Controls vs CH | P-value Controls vs episodic vs chronic CH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of individuals | 20 | 19 | 20 | ||

| Age (years) | 42.2 ± 12.4 | 40.0 ± 9.0 | 45.0 ± 13.4 | 0.97c | 0.39c |

| Gender (M/F) | 15/5 | 15/4 | 15/5 | 1d | 0.86c |

| Current smokers (n) | 10 | 10 | 11 | 0.79d | 0.90d |

| Packyears (n) | 11.6 ± 15.4 | 8.4 ± 11.5 | 14.7 ± 17.3 | 0.99c | 0.49c |

| Days since latest attack | — | 6.8 ± 13.9 | 5.8 ± 20.8 | — | 0.70e |

| Attack frequency during month prior to sampling (#/day) | — | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 2.1 | — | 0.13e |

| Prophylactic treatment | — | — | |||

| - Verapamil | 8 | 10 | 0.76f | ||

| - Othera | 4 | 10 | 0.096f | ||

| - None | 7 | 3 | 0.29f | ||

| Acute treatment | — | — | |||

| - Sumatriptan s.c. | 13 | 15 | 0.73f | ||

| - Oxygen | 6 | 11 | 0.22f | ||

| - Otherb | 3 | 4 | 1f | ||

| - None | 2 | 3 | 1f |

Table gives mean ± standard deviation or exact number. All prophylactic treatment listed is current treatment, and all acute treatment is used within one month before blood sampling. CH: cluster headache; F: females; M: males; RIN: RNA integrity value.

aOther prophylactics used include lithium, frovatriptan, prednisolone, pizotifen, amitriptyline, mometasonfuroate and propranolol.

bOther acute treatment used include morphine, naproxen, paracetamol, ibuprofen and rizatriptan. Medication is only included in the table when used by >10% of cluster headache patients.

cANOVA.

dChi-square test.

eStudents t-test.

fFisher exact test.

Identification of differentially expressed genes

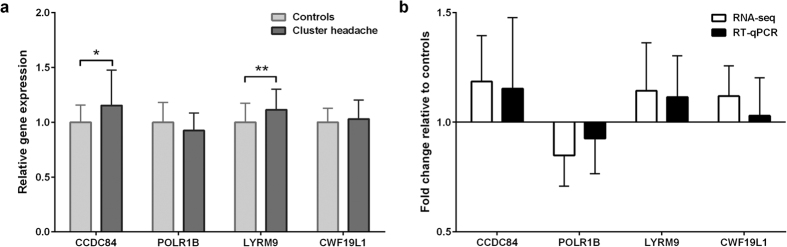

Expression differences between participants with cluster headache and controls were very modest, in fact no gene was found significant with a False Discovery Rate (FDR) of 0.05 or 0.1 (Table 2). Removing samples (n = 2) with a large time (>30 days) between inclusion and last attack did not affect results (Fig. S1). The Global Test, however, showed that the overall gene expression profile did differ between participants with cluster headache and controls (P = 0.037). This indicates that differential expression even after correction for multiple testing might have been identified if a larger sample size had been used. More lenient P-value thresholds were used for the selection of genes for follow up analyses (Table 2). Similar results were obtained for episodic and chronic cluster headache when these subsets were tested against controls (Table 2). RT-qPCR analysis of four genes from the top 15 differentially expressed genes identified in the RNA-seq dataset could not fully confirm differential expression, with only two genes (LYRM9 and CCDC84) showing significantly differential expression (Fig. 1a). Irrespective of the statistical significance, we could replicate the fold-changes in expression (Fig. 1b).

Table 2. Number of differentially expressed genes based on different P-value thresholds.

| P < 0.005 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.05 | FDR < 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH vs controls | 310 | 614 | 2,347 | 0 |

| Episodic CH vs controls* | 90 | 226 | 1,313 | 0 |

| Chronic CH vs controls* | 125 | 200 | 1,233 | 0 |

CH: cluster headache; FDR: false discovery rate.

*Post-hoc analysis for cluster headache subtypes of differentially expressed genes for cluster headache.

Figure 1. RT-qPCR validation of genes differentially expressed between cluster headache patients and controls.

Four genes were chosen from the top 15 differentially expressed genes between participants with cluster headache and controls. Data were normalized to TBP mRNA expression. (a) Gene expression measured by RT-qPCR in the cluster headache group relative to the expression in the control group. (b) Comparison of fold-change of gene expression in participants with cluster headache relative to controls measured by RNA-seq and RT-qPCR. Means ± SD, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Brain, oxidation and intracellular signalling functions associated with cluster headache

As interpreting individual genes is highly susceptible to false-positive findings, several analysis methods were applied to explore the RNA-seq dataset at the level of functional gene sets. First, a pathway enrichment analysis was performed to identify functions overrepresented in lists of differentially expressed genes. Two P-value thresholds (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01; see Table 1 for the respective number of genes) for differential expression were used, and pathways that were overrepresented in both lists of genes were considered associated with cluster headache (Table 3). This way, the effect of possible false-positive associations was reduced. The top overrepresented pathway in genes with P < 0.05 is “GABA Receptor Signalling”. Most other overrepresented pathways involved signalling molecules, e.g. NUR77, CD28, Prolactin and IL-4.

Table 3. Pathways significantly overrepresented in the genes differentially expressed in cluster headache.

| Pathway | Threshold DEGs P < 0.05 |

Threshold DEGs P < 0.01 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | Count | P-value | Count | |

| GABA Receptor Signaling | 0.00053 | 13 | 0.043 | 4 |

| Calcium-induced T Lymphocyte Apoptosis | 0.0015 | 18 | 0.028 | 6 |

| Nur77 Signaling in T Lymphocytes | 0.0066 | 15 | 0.0040 | 7 |

| CD28 Signaling in T Helper Cells | 0.0098 | 28 | 0.021 | 10 |

| Cdc42 Signaling | 0.015 | 29 | 0.014 | 11 |

| Role of BRCA1 in DNA Damage Response | 0.017 | 21 | 0.023 | 8 |

| IGF-1 Signaling | 0.022 | 24 | 0.025 | 9 |

| Actin Nucleation by ARP-WASP Complex | 0.023 | 15 | 0.0083 | 7 |

| Prolactin Signaling | 0.026 | 19 | 0.041 | 7 |

| IL-4 Signaling | 0.026 | 19 | 0.041 | 7 |

| PTEN Signaling | 0.043 | 25 | 0.045 | 9 |

| Telomerase Signaling | 0.044 | 23 | 0.026 | 9 |

P-value thresholds for differential gene expression are P < 0.05 and P < 0.01. Pathways are included if overrepresented in lists of differentially expressed genes based on both P-value thresholds. DEGs: differentially expressed genes.

Next, the Global Test was applied, which takes into account the full list of results, instead of merely a selection of differentially expressed genes. The Global Test is therefore especially suited to identify gene sets of which many genes show subtle associations while each individual gene association might be too small to be identified in the differential gene expression analysis27. Several functions associated with cluster headache are related to the brain, including “Calcium-release channel activity” (P = 0.0083), “Ganglioside metabolic process” (P = 0.0025) and Reactome pathways “GABA receptor activation” (P = 0.0066) and “Inhibition of voltage gated Ca2+channels via Gbeta/gamma subunits” (P = 0.0074) (Table 4). Other functions associated with cluster headache include several developmental and metabolism-related processes. Lastly, molecular function “Glutathione peroxidase activity” (P = 0.0013) and biological process “Response to hydroperoxide” (P = 0.006) are related to oxidation processes.

Table 4. Differentially regulated functional gene sets identified with the Global Test.

| Term ID | Description | P-value | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Function | |||

| GO:0004602 | Glutathione peroxidase activity | 0.0013 | 11 |

| GO:0015278 | Calcium-release channel activity | 0.0083 | 11 |

| GO:0043560 | Insulin receptor substrate binding | 0.0085 | 11 |

| GO:0031490 | Chromatin DNA binding | 0.0100 | 49 |

| Biological process | |||

| GO:0009235 | Cobalamin metabolic process | 0.0014 | 13 |

| GO:0001573 | Ganglioside metabolic process | 0.0025 | 16 |

| GO:0045682 | Regulation of epidermis development | 0.0026 | 30 |

| GO:0046033 | AMP metabolic process | 0.0037 | 13 |

| GO:0019082 | Viral protein processing | 0.0044 | 10 |

| GO:1901068 | Guanosine-containing compound metabolic process | 0.0047 | 24 |

| GO:0033194 | Response to hydroperoxide | 0.0060 | 14 |

| GO:0007220 | Notch receptor processing | 0.0061 | 18 |

| GO:0035357 | Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor signaling pathway | 0.0066 | 12 |

| GO:0008206 | Bile acid metabolic process | 0.0077 | 20 |

| GO:0032515 | Negative regulation of phosphoprotein phosphatase activity | 0.0083 | 13 |

| GO:0070987 | Error-free translesion synthesis | 0.0091 | 14 |

| GO:0045123 | Cellular extravasation | 0.0097 | 29 |

| Reactome | |||

| R-HSA-1660661 | Sphingolipid de novo biosynthesis | 0.0022 | 24 |

| R-HSA-428157 | Sphingolipid metabolism | 0.0043 | 48 |

| R-HSA-977444 | GABA B receptor activation | 0.0064 | 18 |

| R-HSA-977443 | GABA receptor activation | 0.0066 | 19 |

| R-HSA-997272 | Inhibition of voltage gated Ca2+channels via Gbeta/gamma subunits | 0.0074 | 11 |

| R-HSA-400042 | Inhibition of insulin secretion by adrenaline noradrenaline | 0.0075 | 16 |

| R-HSA-1296065 | Inwardly rectifying K channels | 0.0089 | 12 |

Association with previously identified differentially expressed genes and hypocretin

The Global Test was also applied to study the overlap with genes previously identified as differentially expressed in cluster headache24,25. To this end, the 9024 and 1,17225 previously identified genes were imported as custom gene sets into the Global Test. No association was found with cluster headache with either gene set in our data set (P = 0.33 and P = 0.14, respectively). To study the association with cluster headache with hypocretin in the RNA-seq data, two custom gene sets were constructed in the STRING database and in the Euretos Knowledge Platform BRAIN. In STRING, 138 predicted functional partners of HCRT were identified, of which 49 were identified in blood with high enough expression. In BRAIN, 127 genes linked to HCRT were identified, of which 66 were identified in blood with high enough expression. No association was found with cluster headache for the custom hypocretin gene sets in the RNA-seq data (P = 0.39 and P = 0.19, respectively).

Inflammation, mitochondria and intracellular signalling-related modules associated with cluster headache

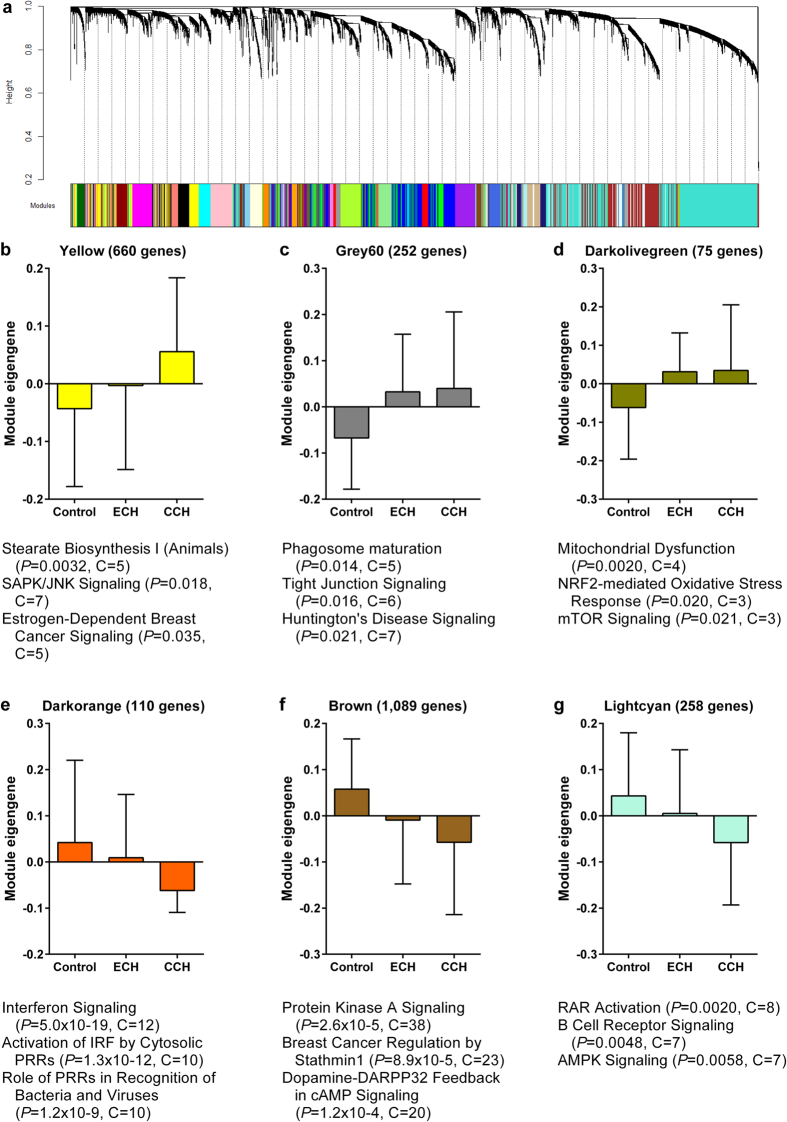

Besides studying differentially expressed genes, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was used to cluster genes in modules based on co-expression in the RNA-seq dataset, and to study the association of each of the modules with cluster headache. Because co-expression often results from genes being part of the same biological process, this method not only reduces the effect of multiple testing, but also greatly enhances the possibility for biological interpretation of an association. A total of 40 co-expression modules were identified, ranging in size from 34 to 2,903 genes, of which 6 showed an association with cluster headache (Fig. 2). Three modules contained genes with higher expression in cluster headache (i.e. “Yellow”, “Grey60” and “Darkolivegreen” modules), as visualized in the bar graphs of the module eigengenes, which can be considered as the optimal summary of the expression pattern of the genes in the modules (Fig. 2). These modules are enriched for genes involved in metabolic pathways and intracellular signalling (Yellow), phagocytosis and brain-related signalling (Grey60) and mitochondria (Darkolivegreen). Lower expression in cluster headache was seen for the modules “Darkorange”, “Brown” and “Lightcyan”. These modules contain genes involved in inflammation (Darkorange) and intracellular signalling (Brown and Lightcyan).

Figure 2. Gene co-expression modules in whole blood associated with cluster headache.

Detection of co-expression modules in RNA-seq data of whole blood samples of cluster headache patients and controls using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). (a) The cluster dendrogram that gave rise to 40 modules, indicated by different colours. (b–g) Bar graphs of the module eigengenes in controls, episodic (ECH) and chronic cluster headache (CCH) of the six modules associated with cluster headache. The module eigengene can be considered the optimal summary of the module-specific gene expression pattern. Top three pathways significantly overrepresented in each module are listed below each bar graph. P = P-value, C = count of genes in the module belonging to the pathway.

Discussion

In this study we determined whole blood gene expression profiles of 19 participants with episodic cluster headache, 20 with chronic cluster headache, and 20 controls using an RNA-seq approach. To identify genes and pathways associated with cluster headache, analysis methods were applied that searched for association with single genes or for association with modules of co-expressed genes. Differential gene expression did not reveal a single cluster headache-associated gene that survived FDR multiple testing correction, hence differences in expression of genes in cluster headache, at best, are very modest.

As cluster headache-associated genes might be involved in multiple pathways, we conducted two types of functional enrichment analysis: functional enrichment in the lists of differentially expressed genes using a standard pathway enrichment method and the Global Test. These analyses suggest that inter- and intracellular signalling pathways involving brain-related molecules (e.g. GABA and ion channels) and inflammation-related molecules (e.g. CD28 and interleukin-4 (IL-4)), metabolism and oxidation might be involved in cluster headache. Although these findings should be interpreted with caution as inflammation-related processes seem to show up rather frequently in gene expression studies in blood28,29, inflammatory mediators such as IL-2 and soluble adhesion molecules have repeatedly been associated with cluster headache11,12,30,31. Abnormal expression of inflammatory genes in cluster headache was also observed in one of the earlier gene expression profiling studies25, although the genes identified in that study did not overlap with the genes found in our gene expression analysis.

Clustering analysis with WGCNA identified 40 modules of co-expressed genes in the gene expression data, of which six were associated with cluster headache. Associating gene co-expression modules to a disorder may provide potentially useful biological information with a disorder32, as gene co-expression modules capture a wide variety of biological factors, e.g. tissue composition and activity of transcription factors. Genes involved in inflammation and intracellular signalling were enriched in cluster headache-associated modules and the differential gene expression analysis, supporting a pathophysiological role of these processes in cluster headache. Association with mitochondria was only found in the co-expression analysis. This finding, however, might still be relevant as altered mitochondrial function has been detected with phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy in skeletal muscle and brain in cluster headache33,34 and migraine (reviewed by Sparaco et al.35).

A role for hypocretin in the pathophysiology of cluster headache has previously been suggested36,37,38. Global Test analysis of the custom hypocretin gene sets, however, failed to reveal evidence for involvement of hypocretin in our RNA-seq data, which is in line with the absence of genetic association of HCRTR2 gene variants with cluster headache in the largest sample studied so far15. Blood may, however, not be the most appropriate tissue to study possible deregulation of the hypocretin pathway. Only 49/139 and 66/127 genes of the two custom hypocretin gene sets could be measured reliably in blood. Moreover, changes in the hypocretin pathway may not be readily reflected at the RNA level and the timing of blood sampling in relation to cluster headache attacks might be critical. A recent study in cerebrospinal fluid, in which significantly reduced hypocretin peptide levels were found in cluster headache patients39, further indicates that analysis of other tissues than blood is required to identify all genes and pathways involved in cluster headache. Then again, the worth of blood is supported by the finding that several biomarkers, including PACAP-3840 and methionine-enkephalin41, show altered levels during the course of a cluster headache attack in blood plasma.

Our results are in sharp contrast with an earlier gene profiling study in which microarray of immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines identified over 1,100 differentially expressed genes, suggesting rather massive gene deregulation in cluster headache25. We are unsure how to explain these marked differences. Possible reasons might be the small sample size of only eight patients who were also using lithium, and the differences in studied tissue. Both tissue type and medication use have previously been shown to have substantial effect on gene expression42,43,44. The Global Test analysis in our study did not identify associations for this and another gene set previously found differentially expressed24,25. Moreover, when comparing our top differentially expressed genes (P < 0.005) we could confirm only two genes that were identified in both previous studies: mastermind like transcriptional coactivator 2 (MAML2), a transcriptional coactivator involved in Notch signalling45, and lysozyme (LYZ), an antibacterial agent and possible inflammatory biomarker for Alzheimer disease46 and Niemann-Pick Type C47. Our results suggest that uncovering significant differentially expressed genes in cluster headache requires even larger study samples than the 59 we tested. Future studies on cluster headache and other episodic disorders should consider careful matching of study designs with previous studies, to enable result comparison and meta-analysis and should take into account the time of blood withdrawal relative to the occurrence of attacks (i.e. for cluster headache inside or outside an attack period).

In contrast to the previously published gene expression studies for cluster headache, we included episodic as well as chronic cluster headache patients and patients using various types of treatment (so the effect of a specific treatment on the differential gene expression analysis is low). Whereas including episodic and chronic cluster headache patients allowed stratification of patients by cluster headache subtype, given the fact that gene expression differences were only moderate and stratifying patients into subgroups would reduce power, most analyses compared all cluster headache patients with controls. Although the majority of patients (25 out of 39) was included within one day from their last attack, also patients were included with a broader range in time during inclusion and last attack. No information was collected about the time between the inclusion and the start and end of the cluster period in the episodic patients, therefore the gene expression analyses could not be controlled for periodicity of the cluster headache attacks. Importantly, removing patients over 30 days from their last attack did not change the results of the differential gene expression analysis, reflecting the robustness of the results. By allowing a broader time range between inclusion and last attack, our results provide information not only on the gene expression profile related to having an attack per se, but also to having cluster headache and being in an attack cluster. On the other hand, the heterogeneity of the cohort may have suppressed effect sizes and the number of genes that reached the different P-value thresholds. Resampling the same patients during different stages of the disease or including patients only on the same day of a cluster headache attack may aid to unravel differential gene expression patterns directly caused by a cluster headache attack from those caused by other cluster headache-related pathways.

In summary, we performed the largest gene expression profiling study to date in whole blood samples of 39 participants with cluster headache and 20 controls. Gene expression differences between cluster headache and controls were modest at the gene level. However, when analysed at the functional gene set level, genes associated with cluster headache were enriched for intracellular signalling cascades involving brain- and inflammation-related genes. Similar functions as well as mitochondrial functions were enriched in the cluster headache-associated modules of co-expressed genes. Larger study samples will be required to identify the full range of cluster headache-associated genes and pathways.

Methods

Participants

Male and female cluster headache patients and headache-free controls between 18 and 65 years of age were recruited from our specialised headache out-patient clinic and as part of the Leiden University Cluster headache Analysis (LUCA) programme48. Diagnoses of episodic and chronic cluster headache were made according to ICHD-III criteria1. In a personal interview, information was collected on cluster headache history, medication use during the month before sampling, and active smoking and number of pack years (Table 1, Supplementary Table 3). Special effort was made to record the time of the last cluster headache attack prior to blood sampling. No inclusion criteria were formulated regarding time since last cluster headache attack, but as a result of including patients at an outpatient headache clinic most patients were in a “cluster period”. For each two participants with cluster headache one control was included that was matched for gender, age and smoking habits. Demographic features of the three experimental groups (controls, episodic cluster headache and chronic cluster headache) that were used for the RNA-seq analysis were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test were used for comparisons between episodic and chronic cluster headache groups. All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the LUMC. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Peripheral venous blood samples were drawn at the LUMC between May 2014 and September 2015 into: 1) EDTA-containing Vacutainer tubes for leukocyte differential count, and 2) PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes (PreAnalytiX, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for RNA isolation. Leukocyte counts were obtained using standard leukocyte differential count within two hours after blood collection. PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes were incubated overnight at room temperature and subsequently stored at −20 °C.

RNA isolation and sequencing

PAXgene Blood RNA tubes were thawed and incubated for two hours at room temperature before RNA isolation using the PAXgene Blood miRNA kit (PreAnalytiX). Globin mRNA was depleted using the GLOBINclear™ Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). RNA quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Foster City, CA, USA); all samples had a minimal RNA integrity number (RIN) of 7. RIN values of controls, episodic, and chronic cluster headache samples were 8.5 ± 0.3, 8.5 ± 0.3 and 8.3 ± 0.5, respectively (P-value controls vs episodic vs chronic cluster headache = 0.23, ANOVA). TruSeq RNA-Seq libraries were constructed with a circa 160 base pair (bp) insert size, followed by 90 bp paired-end RNA-sequencing on the Illumina Hiseq4000 by BGI Tech Solutions in Hong Kong (www.bgitechsolutions.com).

Sequencing data processing

RNA-seq reads were processed and aligned using the Gentrap pipeline (version 0.3.1) of the Sequencing Analysis Support Core (SASC) of the LUMC (https://humgenprojects.lumc.nl/sasc/). In brief, adapter sequences were clipped from RNA-seq reads using Cutadapt (version 1.5)49 and low-quality bases were removed using Sickle (version 1.33)50. Next, sequencing reads were aligned to the human genome reference GRCh38 using TopHat (version 2.0.13)51, allowing only for unique alignments (max_multihits = 1, read-mismatches = 2, read-gap-length = 2 and mate-inner-dist = 160). Refseq transcript annotations were obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html), and read fragments aligned to known exons were counted per gene using Htseq (version 0.6.1p1)52. All analyses were performed on the gene level.

Quality of the RNA-seq dataset was assessed using FastQC53. Sample quality was assessed by: 1) hierarchical clustering of Spearman correlations between samples, 2) a multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot to visualize sample-to-sample distances, and 3) box plots of count distribution using R (version 3.2.2) and the Bioconductor package Limma (version 3.14.15)54. Next, the RNA-seq data was pre-processed for differential gene expression analysis. First, the data was filtered for low-expressed genes by removing genes with less than 1 CPM in at least 15 samples. Differences in library sizes were then normalized using the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) function in the Bioconductor EdgeR package (version 3.10.5)55. The data was converted to a logarithmic scale using the Limma voom transformation.

Differential gene expression analysis

Differential gene expression between cluster headache or the episodic or chronic subsets and control samples was calculated in Limma by fitting a linear model. To this end, data were normalized for age, gender, current smoking status, and leukocyte counts (basophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils). Effects of medication use on differential gene expression were visualized in a heatmap of the top differentially expressed genes. Samples did not cluster on medication use, therefore, medication was not included as a cofactor in the differential gene expression analysis. FDR was used for multiple testing correction. In addition, several nominal P-value thresholds were applied to classify genes as differentially expressed for functional annotation (Table 2). The Global Test package was applied to test the overall gene expression data for differences between cluster headache and controls28.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

WGCNA was used to construct gene modules based on pairwise correlations between gene expression levels in the RNA-seq data56,57. First, outlier samples were removed more strictly than for the differential gene expression analysis, as they can have large impact on co-expression values. Seven additional samples were removed based on Spearman correlation analysis between samples and MDS plot inspection, leaving 18 control, 19 episodic and 15 chronic cluster headache samples. Next, a signed weighted adjacency matrix was calculated using the power of 15. The power of 15 was chosen from a range of 1 to 20, as it maximized the fit of the scale free topology (R2 > 0.8). Of the adjacency matrix, a topological overlap matrix-based dissimilarity measure was calculated that was used as input for hierarchical clustering. The dynamic tree-cutting algorithm was used to define the modules58. A total of 40 modules were identified, each with a minimal size of 30 genes. Pearson correlations between modules eigengenes (which can be considered the optimal summary of the module-specific gene expression pattern) and cluster headache were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Functional annotation of gene sets and modules

Enrichment analysis of canonical pathways in the lists of differentially expressed genes and the cluster headache-associated modules was performed using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA, Ingenuity Systems®; http://www.ingenuity.com). Only experimentally observed links between genes and pathways were included. The full list of genes that remained after filtering of low-expressed genes (with less than 1 CPM in at least 15 samples) was used as reference gene set. Only pathways from which five or more genes were observed in a list of differentially expressed genes or in a module, or three or more in a module containing up to 100 genes, were included.

Next, the Global Test was applied to identify gene sets associated with cluster headache in the full list of genes27. The Global Test is especially designed to identify related genes consistently associated with a trait, but with small effects that may not reach significance when assessing individual genes. The Global Test might, therefore, identify more subtle functional associations with cluster headache than the gene set enrichment analysis in IPA. Gene sets were included if annotated by Gene Ontology (GO) terms or REACTOME pathways from the curated molecular signature database of the Broad institute (version 5.1) if they contained 10 or more genes. GO terms associated with cluster headache with P < 0.01 were summarized with REVIGO59 by removing redundant terms and only preserving GO terms with a maximum allowed similarity of 0.5.

Custom hypocretin gene sets were built manually in the STRING database for known and predicted protein associations (version 10, http://string-db.org/)60 and in the Euretos Knowledge Platform BRAIN (https://www.euretos-brain.com/). In STRING, a manual gene set was built from predicted functional partners of HCRT based on gene co-expression, high-throughput experiments, databases and text mining; only predicted functional partners with high confidence (confidence score of 0.9 or higher) were included. In BRAIN, all genes linked to the concepts “HCRT”, “HCRTC2” and “orexins” were included. These links are based on a wide variety of databases and text mining. Association of the custom hypocretin gene sets with cluster headache was calculated using the Global Test.

RT-qPCR validation

Findings from the RNA-sequencing data analysis were validated in the same RNA samples by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). To this end, first-strand cDNA was synthesized with the RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA synthesis kit using random hexamer primers (Thermo Scientific Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania). RT-qPCR experiments were carried out in duplicate on the CFX384 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using iQ™ SYBR® Green (Bio-Rad) as fluorophore and exon-spanning primers (Supplementary Table 2). TBP was selected as reference gene based on its low variability in the RNA-seq data and high stability in RT-qPCR analysis. The RT-qPCR data was analysed with Bio-Rad CFX ManagerTM Software (version 3.1). Statistical analysis was performed using a linear model, correcting for age, gender, current smoking status and leukocyte counts (basophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils).

Additional Information

Accession codes: Sequence data has been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the EBI and the CRG, under accession number EGAS00001001918.

How to cite this article: Eising, E. et al. Identifying a gene expression signature of cluster headache in blood. Sci. Rep. 7, 40218; doi: 10.1038/srep40218 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D.E. Blom, M. Schuijt and B.C. Eveleens-Maarse for their medical assistance. This work was supported by grants of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, i.e. the Center of Medical System Biology established by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (to A.M.J.M.v.d.M.) and Spinoza 2009 (to MDF) and EU-funded FP7 “EUROHEADPAIN” grant (nr. 6026337 to M.D.F. & A.M.J.M.v.d.M. & G.M.T.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: E.E., B.d.V., G.M.T. and A.M.J.M.v.d.M. Performed the experiments and analysed the data: E.E. and L.S.V. Provided expert assistance and suggestions: N.P., G.M.T. and P.A.C.H. Wrote the manuscript: E.E. and A.M.J.M.v.d.M. Read and revised the manuscript: E.E., N.P., B.d.V., M.D.F., P.A.C.H., G.M.T. and A.M.J.M.v.d.M.

References

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33, 629–808 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt A. D. & Goadsby P. J. Cluster headache. BMJ 344, e2407 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. B. Epidemiology and genetics of cluster headache. Lancet Neurol. 3, 279–83 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischera M., Marziniak M., Gralow I. & Evers S. The incidence and prevalence of cluster headache: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Cephalalgia 28, 614–8 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekbom K., Svensson D. A., Traff H. & Waldenlind E. Age at onset and sex ratio in cluster headache: observations over three decades. Cephalalgia 22, 94–100 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudrow L. The cyclic relationship of natural illumination to cluster period frequency. Cephalalgia 7 Suppl 6, 76–8 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. Cluster headache: severity and temporal profiles of attacks and patient activity prior to and during attacks. Cephalalgia 1, 209–16 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goadsby P. J. Pathophysiology of cluster headache: a trigeminal autonomic cephalgia. Lancet Neurol. 1, 251–7 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naegel S., Holle D. & Obermann M. Structural imaging in cluster headache. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 18, 415 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrar R. G., Black D. F., Dodick D. W. & Davis D. H. Outcome of trigeminal nerve section in the treatment of chronic cluster headache. Neurology 60, 1360–2 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardebo J. E. How cluster headache is explained as an intracavernous inflammatory process lesioning sympathetic fibers. Headache 34, 125–31 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond P. D. Mechanisms of autonomic disturbance in the face during and between attacks of cluster headache. Cephalalgia 26, 633–41 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainero I. et al. Genes and primary headaches: discovering new potential therapeutic targets. J Headache Pain 14, 61 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürks M. Genetics of cluster headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 14, 132–9 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller C. M. et al. Cluster headache and the hypocretin receptor 2 reconsidered: a genetic association study and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia 35, 741–7 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner H. M. et al. mRNA blood expression patterns in new-onset idiopathic pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia 54, 272–9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E. & Tsai S. J. Genome-wide microarray analysis of gene expression profiling in major depression and antidepressant therapy. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 64, 334–40 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbett K. A. et al. Coordinated messenger RNA/microRNA changes in fibroblasts of patients with major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 77, 256–65 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrokolias A. et al. Huntington’s disease biomarker progression profile identified by transcriptome sequencing in peripheral blood. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23, 1349–56 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehadeh L. A. et al. SRRM2, a potential blood biomarker revealing high alternative splicing in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 5, e9104 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B. et al. PGC-1alpha, a potential therapeutic target for early intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 52ra73 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougeot J. L., Li Z., Price A. E., Wright F. A. & Brooks B. R. Microarray analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes from ALS patients and the SAFE detection of the KEGG ALS pathway. BMC Med. Genomics 4, 74 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Knock J. et al. Gene expression profiling in human neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 8, 518–30 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrand C. et al. Gene expression profiling in cluster headache: a pilot microarray study. Headache 46, 1518–34 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M. et al. Preliminary Transcriptome Analysis in Lymphoblasts from Cluster Headache and Bipolar Disorder Patients Implicates Dysregulation of Circadian and Serotonergic Genes. J. Mol. Neurosci. 56, 688–95 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- t Hoen P. A. et al. Deep sequencing-based expression analysis shows major advances in robustness, resolution and inter-lab portability over five microarray platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, e141 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeman J. J., van de Geer S. A., de Kort F. & van Houwelingen H. C. A global test for groups of genes: testing association with a clinical outcome. Bioinformatics 20, 93–9 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepgul N., Cattaneo A., Zunszain P. A. & Pariante C. M. Depression pathogenesis and treatment: what can we learn from blood mRNA expression? BMC Med. 11, 28 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. Y. et al. Biomarkers in schizophrenia: A focus on blood based diagnostics and theranostics. World J. Psychiatry 6, 102–17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg A., Sjostrand C., Sominanda A., Fogdell-Hahn A. & Remahl A. I. Interleukin-2 gene expression in different phases of episodic cluster headache–a pilot study. Acta Neurol. Scand. 124, 130–4 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remahl A. I., Bratt J., Mollby H., Nordborg E. & Waldenlind E. Comparison of soluble ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin levels in patients with episodic cluster headache and giant cell arteritis. Cephalalgia 28, 157–63 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente A. From ‘differential expression’ to ‘differential networking’ - identification of dysfunctional regulatory networks in diseases. Trends Genet. 26, 326–33 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodi R. et al. Quantitative analysis of skeletal muscle bioenergetics and proton efflux in migraine and cluster headache. J. Neurol. Sci. 146, 73–80 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagna P. et al. Phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy in cluster headache. Neurology 48, 113–8 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparaco M., Feleppa M., Lipton R. B., Rapoport A. M. & Bigal M. E. Mitochondrial dysfunction and migraine: evidence and hypotheses. Cephalalgia 26, 361–72 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. R., Akerman S. & Goadsby P. J. Modulation of nociceptive dural input to the trigeminal nucleus caudalis via activation of the orexin 1 receptor in the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 2825–33 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. R. & Goadsby P. J. Cluster headache, hypothalamus, and orexin. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 13, 147–54 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J. M. Hypocretin (orexin): role in normal behavior and neuropathology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 125–48 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barloese M. et al. Reduced CSF hypocretin-1 levels are associated with cluster headache. Cephalalgia 35, 869–76 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuka B. et al. Release of PACAP-38 in episodic cluster headache patients - an exploratory study. J Headache Pain 17, 69 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosnaim A. D. et al. Changes in plasma methionine-enkephalin levels associated with a cluster headache episode. Am J Ther. 20, 463–8 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium G. T. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science 348, 648–60 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vause C. V. & Durham P. L. Identification of cytokines and signaling proteins differentially regulated by sumatriptan/naproxen. Headache 52, 80–9 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z. et al. Therapeutic concentration of lithium stimulates complement C3 production in dendritic cells and microglia via GSK-3 inhibition. Glia 63, 257–70 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Sun T., Kobayashi K., Gao P. & Griffin J. D. Identification of a family of mastermind-like transcriptional coactivators for mammalian notch receptors. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 7688–700 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmfors L. et al. Protective properties of lysozyme on beta-amyloid pathology: implications for Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 83, 122–33 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M. S. et al. Plasma signature of neurological disease in the monogenetic disorder Niemann-Pick Type C. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 8051–66 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbrink L. A. et al. Stepwise web-based questionnaires for diagnosing cluster headache: LUCA and QATCH. Cephalalgia 33, 924–31 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnetjournal 17, 10–12 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Joshi N. A. & Sickle F. J.: A sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files [Software] Available at https://github.com/najoshi/sickle (2011).

- Trapnell C., Pachter L. & Salzberg S. L. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25, 1105–11 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P. T. & Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. [Software] Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc (2010).

- Ritchie M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J. & Smyth G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–40 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P. & Horvath S. Fast R Functions for Robust Correlations and Hierarchical Clustering. J. Stat. Softw. 46 (2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P. & Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 559 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P., Zhang B. & Horvath S. Defining clusters from a hierarchical cluster tree: the Dynamic Tree Cut package for R. Bioinformatics 24, 719–20 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supek F., Bosnjak M., Skunca N. & Smuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One 6, e21800 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini A. et al. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D808–15 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.