1. Introduction

Osteotomies are generally performed for osteoarthritis and osteonecrosis. The corrective osteotomy technique is adapted to correct lower limb deformities caused by trauma, infections and congenital diseases such as Blount’s disease, rickets and skeletal dysplasia. Previous literature has discussed the surgical procedure, period and technique of osteotomies to correct these deformities.1, 2, 3

As we mainly treat knee-joint deformities at our hospital, we occasionally encounter younger patients who wish to undergo cosmetic corrective surgical treatment for bowlegs. They have no pain or functional disorder in their knees, and therefore could live an ordinary life without surgical treatment. However, most cannot live an active social life because of mental trauma and psychiatric disorders. From the patient’s appearance, it is impossible to notice these factors and understand their true suffering.

Generally, cosmetic corrective surgery is not performed for asymptomatic bowlegs. Doctors hesitate to perform cosmetic operations, as post-operative complications and patient satisfaction cannot be guaranteed. However, we chose to perform cosmetic high tibial osteotomy (HTO) in specific cases. Personality disorders, especially in younger patients, are associated with poor cosmetic surgery outcomes.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 However, by supporting the patient’s physical and mental condition before the operation, we obtained good clinical results both physically and mentally. HTO is a useful tool for physical conditions that include mental factors. Given the availability of cosmetic knee osteotomy techniques to correct lower limb deformities in younger patients, we report on surgical planning and several important technical points.

2. Methods

Mechanical and anatomic axes were measured by using standing X-ray preoperatively and postoperatively. We measured femoral tibial angle (FTA), lateral proximal femoral angle (LPFA), mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (mLDFA), medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA), lateral distal femoral angle (LDFA), anatomical medial neck shaft angle (aMNSA), anatomical lateral distal femoral angle (aLDFA) and Mikulicz line. Concerning Mikulicz line, we defined the center of the eminence as 0%, while both tibial edges were 100%. The center of rotation angulation (CORA) was judged by preoperative X-ray. The CORA is the ideal point for the center of correction. The intersection point of the proximal and distal mechanical axes is defined as the CORA.9 As the CORA was at the proximal tibia (Table 1), we performed the cosmetic surgical treatment by using open-wedge HTO technique. The correction angle was examined using standing X-ray. We planned for the Mikulicz line to pass through the center of the eminence and slightly outward. This would yield a postoperative standing FTA of 174°. The medial aspect of the proximal tibia was exposed and the biplanar open wedge osteotomy was performed as described method.10 Tuberosity fragment stays with distal fragment. After biplanar osteotomy, the osteotomy site was slowly opened by the wedge opener until the planned realignment of the knee was obtained. The Mikulicz line during the surgical correction was checked at the full extension of the knee by carefully using a straight steel rod and fluoroscopic control. Beta-tricalcium phosphate blocks, OSferion 60 (Olympus Terumo Biomaterial, Tokyo, Japan) were inserted as a bone filler into the gap. After that, a Tomofix locking plate (Johnson & Johnson, New Jersey, USA) was prepositioned and fixed.

Table 1.

Preoperative X-ray evaluation of the mechanical and anatomic axes (degrees).

| Case.1 Right |

Left | Case.2 Right |

Left | Case.3 Right |

Left | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTA | 186 | 183 | 180 | 180 | 183 | 183 |

| LPFA | 95 | 95 | 89 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| mLDFA | 85 | 85 | 90 | 90 | 87 | 88 |

| MPTA | 80 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 81 |

| LDTA | 92 | 91 | 91 | 91 | 87 | 88 |

| aMNSA | 132 | 132 | 130 | 130 | 131 | 131 |

| aLDFA | 85 | 84 | 83 | 83 | 82 | 82 |

FTA: femoral tibial angle, LPFA: lateral proximal femoral angle, mLDFA: mechanical lateral distal femoral angle, MPTA: medial proximal tibial angle, LDTA: lateral distal tibial angle, aMNSA: anatomical medial neck shaft angle, aLDFA: anatomical lateral distal femoral angle. Normal range of MPTA is 85–90°.

Between HTO for symptomatic elderly patients and younger asymptomatic patients, there is no difference in postoperative rehabilitation. The day after surgery, range of motion, muscle strengthening exercises and partial weight bearing were started. The patients were permitted full weight bearing within the limit of their pain. Two weeks after surgery, all patients could walk with/without support equipment.

3. Results

3.1. Case 1: 33-year-old male

As this patient was previously anxious about his bowlegs (Fig. 1a), he learned about cosmetic corrective surgery from an authority on knee osteotomies. He presented to our hospital seeking a high tibial osteotomy. He had no knee pain or functional disorder. During his initial consultation, the patient’s expression was stiff. He only wanted cosmetic surgery. I did not understand his psychological background, which was concerning because he wanted to undergo cosmetic surgery despite a lack of symptoms. The physiotherapist, nurse and I talked with him for over 2 months following his initial consultation, and gained sufficient confidence in his interest in the surgery. When he was a child, his friends teased him about his bowlegs. This event was a mental trauma that led him to withdraw from community life. We performed HTO (Fig. 1b). Following HTO, the right FTA was improved from preoperative 186° to postoperative 174° and left FTA was improved from 183° to 175°. He has since returned to an active social life.

Fig. 1.

X-ray images (Case 1). (a) preoperative imaging, with Mikulicz line noted; (b) postoperative imaging, with Mikulicz line noted.

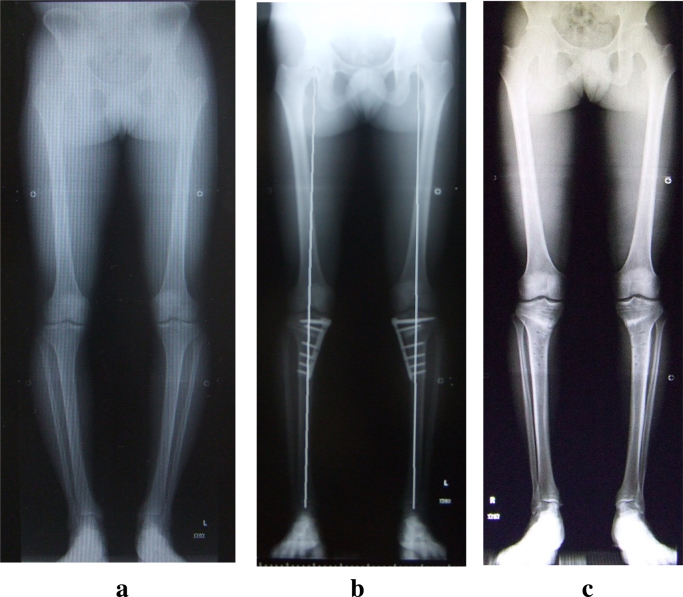

3.2. Case 2: 25-year-old male

As this patient was previously anxious about his bowlegs (Fig. 2a), he self-learned about corrective techniques. He was referred to our hospital to undergo HTO. He had no knee pain or functional disorder. The patient wished to discuss cosmetic surgical treatment during his initial consultation, but his expression and voice was stiffened by tension and anxiety. He didn’t say anything about himself except for his occupation, which was a professional dancer. He only asked questions about our achievements with HTO for corrective operations. The medical staff and I talked with him for over 2 months following his initial consultation. Although dancing is graceful and elegant, it is highly competitive on the professional level. The beauty of body line and pliability is an important factor for competitive scoring. This makes appearance critical. For professional dancers, their appearance affects their life directly and becomes an important factor when selecting a partner. He felt compromised by his bowlegs and had therefore abandoned professional dancing. We performed HTO (Fig. 2b and c). Following HTO, the right FTA was improved from preoperative 180° to postoperative 174° and left FTA was improved from 180° to 175°. He has since returned to competition and achieved positive results.

Fig. 2.

X-ray images (Case 2). (a) preoperative imaging; (b) postoperative imaging following open-wedge HTO, with Mikulicz line noted; (c) following hardware removal.

3.3. Case 3: 39-year-old female

This patient has had long-term anxiety about her bowlegs. She learned about corrective surgery from an authority on knee osteotomies. She presented to our hospital to discuss cosmetic treatment with HTO. She had no knee pain or functional disorder. During the initial consultation the patient’s expression was stiff. To understand her psychological background, my medical staff and I talked with her for over 2 months about the procedure. When the patient was a junior high school student, her friends teased her about her bowlegs. This led her to avoid community life. We performed HTO. Following HTO, the right FTA was improved from preoperative 183° to postoperative 174° and left FTA was improved from 183° to 173°. She has since returned to an active social life, and is currently doing ballet.

3.4. X-p evaluations

Our cases did not have rotational anomalies. As the CORA was at the proximal tibia, we performed HTO. Following HTO, the FTA, MPTA and Mikulicz lines were improved from preoperative 182.5 ± 2.3°, 81.3 ± 0.8° and 83.7 ± 19.6% medial to postoperative 174.1 ± 0.8°, 89.5 ± 0.5° and 1.25 ± 5.1% lateral. All legs grossly appeared well aligned (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Postoperative changes in FTA, MPTA and Mikulicz lines compared with preoperative measurements.

4. Discussion

High tibial osteotomy is generally performed for osteoarthritis or osteonecrosis in older patients. In Japan, the HTO correction angle allows for mild valgus, generally lying between 165°–170° of FTA.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Good post-operative results have been commonly reported.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20 In our series all patients were younger. Post-traumatic changes, post-infectious changes and congenital diseases can lead to bowlegs in younger patients. When planning surgical correction, it is necessary to distinguish between the painful bowlegs of older patients and the painless bowlegs in younger patients. Excessive valgus correction is not suitable for those who seek to engage in sports or an active lifestyle.

If corrective surgery is performed before epiphyseal closing, the corrected limbs will return to their former state. Our cases were different from older or congenital bowlegs. These cases demanded an attractive shape following surgical treatment. Our patients had already closed their epiphyses, so it was thought that there was little risk that they would return to their preoperative state. A previous report found that the best cosmetic correction angle for younger patients is 173°–174°, which is a slight valgus correction. Moreover, it was reported that recurrent deformities were rarely seen in younger patients, compared with those observed in undercorrected cases of HTO for osteoarthritic knees.21 We planned for the Mikulicz line to pass through the center of the eminence and slightly outward. This would yield a postoperative standing FTA21 of 174° after corrective surgical treatment.

When we perform cosmetic corrections on younger patients, it is necessary to consider lower limb rotational anomalies. In an evaluation of lower limb rotation, it was reported that leg evaluation is performed visually by checking the angles made by the thigh and foot axes. The femur is evaluated by checking for bilateral leg axis symmetry when patients flex their knees to 90° while in the prone position. When it is difficult to perform a macroscopic evaluation of the lower limbs, computed tomography is necessary.22, 23 If it is necessary to correct a rotational anomaly, we perform our osteotomies below the tibial tuberosity or use external fixation.21

Even if a patient wishes for corrective surgery, it is generally not ideal to perform a procedure on the lower limbs of younger patients without pre-existing pain or reduced function. With respect to the correction of the bowlegs of younger patients, the level of success demanded by younger patients is high. If the patient regards the operation as easy, postoperative treatment will become difficult. These factors should be discussed prior to surgical treatment. Especially, patients with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) do not have functional disorders caused by bowlegs but still restrict their activities. These patients typically feel inferior about their appearance. Some patients’ social lives are affected. Childhood trauma and surrounding social challenges can be the root of mental issues. The objective judgement of their appearance is difficult for these patients. Patients with BDD also tend to be skeptical of medical staff. It is important that the physician obtain the patient’s confidence.

The positive effects and utility of cosmetic operations have been reported. However, when a surgeon decides to perform a cosmetic corrective operation, the patient type must be considered.24, 25 Cosmetic surgery is more complex for adolescents than adults,4 because there are more factors that affect the satisfaction of these patients. Patients that are younger, male, have unrealistic expectations for cosmetic outcomes, have minimal deformity, are motivated to obtain surgery based on relationship issues and have a history of depression, anxiety, or personality disorders are associated with poor outcomes.5 In particular, patients who have unreasonable expectations tend to be dissatisfied with cosmetic operations. Some of these patients have BDD, which was reported to be a predictor of poor outcomes.7, 8 Patients don’t necessarily tell their doctor the truth. Some reports have indicated that a preoperative psychiatric assessment is necessary when considering a cosmetic procedure.26, 27 When deciding to perform cosmetic surgery, medical staff should understand the psychiatric background of the patient, especially if the cosmetic surgery is being performed despite a lack of symptoms. A good relationship with the patient is critical. Until a smiling face was mutually present, all medical staff sought to understand the patient’s personality and to form a trusting relationship. This contributed to avoiding distrust with respect to postoperative symptoms such as pain. Thus, it is considered that cosmetic surgery should be performed only after patients have been able to speak from their hearts and talk freely about everything with medical staff, and that a trusting relationship between patients and medical staff has been established. These patients rehabilitated successfully and became self-confident about a return to a normal social life.

Deformity correction using HTO is not only a treatment for osteoarthritis and osteonecrosis but is also useful for cosmetic deformity correction. Moreover, recent studies have shown that limb malalignment and leg length differences are causes of osteoarthritis.28, 29, 30, 31 Cosmetic correction is considered to be useful in the prevention of osteoarthritis. Risks include excessive hope and the possibility of operative complications. Cosmetic correction of the asymptomatic bowlegs of younger patients should not be performed without due consideration. After all medical staff understand the patient’s mental background sufficiently and forms a good relationship with the patient, the physician should explain the operative treatment in detail. Cosmetic corrections should only be performed once the physician decides to support the patient after the procedure.

5. Conclusion

Deformity correction using HTO is not only a treatment for osteoarthritis and osteonecrosis but is also useful for bowleg correction. However, unlike surgical treatment for osteoarthritis or osteonecrosis, it is necessary to require many important points. The patients who requested purely cosmetic operation had mental suffering. As cosmetic surgery on patients with mental disorders is often associated with poor outcomes, to obtain a good result both physically and mentally, it is very important to gain sufficient confidence, to plan surgical procedure, and to support the patient’s mental condition throughout surgery and postoperative management.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Mr. Shinya Tada for his psychiatric intervention.

References

- 1.Huang Y., Gu J., Zhou Y. Osteotomy at the distal third of tibial tuberosity with LCP L-buttress plate for correction of tibia vara. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masrouha K.Z., Sraj S., Lakkis S. High tibial osteotomy in young adults with constitutional tibia vara. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Putzeys P., Wilmes P., Merle M. Triple tibial osteotomy for the correction of severe bilateral varus deformity in a patient with late-onset Blount's disease. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:731–735. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2061-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamburoğlu H.O., Ozgür F. Postoperative satisfaction and the patient's body image, life satisfaction, and self-esteem: a retrospective study comparing adolescent girls and boys after cosmetic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005;31:739–745. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honigman R.J., Phillips K.A., Castle D.J. A review of psychosocial outcomes for patients seeking cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1229–1237. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000110214.88868.CA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castle D.J., Honigman R.J., Phillips K.A. Does cosmetic surgery improve psychosocial wellbeing. Med J Aust. 2002;176:601–604. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarwer D.B., Crerand C.E. Didie ER Body dysmorphic disorder in cosmetic surgery patients. Facial Plast Surg. 2003;19:7–18. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarwer D.B., Wadden T.A., Pertschuk M.J. Body image dissatisfaction and body dysmorphic disorder in 100 cosmetic surgery patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1644–1649. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199805000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paley D., Herzenberg J.E., Tetsworth K. Deformity planning for frontal and sagittal plane corrective osteotomies. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25:483–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staubli A.E., Jacob H. Evolution of open-wedge high-tibial osteotomy: experience with a special angular stable device for internal fixation without interposition material. Int Orthop. 2010;34:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0902-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujisawa Y., Masuhara K., Shiomi S. The effect of high tibial osteotomy on osteoarthritis of the knee: An arthroscopic study of 54 knee joints. Orthop Clin North Am. 1979;10:585–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habata T., Uematsu K., Hattori K. High tibial osteotomy that does not cause recurrence of varus deformity for medial gonarthrosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:962–967. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasuda K., Majima T., Tsuchida T. A ten- to 15-year follow-up observation of high tibial osteotomy in medial compartment osteoarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;282:186–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majima T., Yasuda K., Katsuragi R. Progression of joint arthrosis 10 to 15 years after high tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;381:177–184. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200012000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aoki Y., Yasuda K., Mikami S. Inverted V-shaped high tibial osteotomy compared with closing-wedge high tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the knee Ten-year follow-up result. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1336–1340. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B10.17532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koshino T., Yoshida T., Ara Y. Fifteen to twenty-eight years' follow-up results of high tibial valgus osteotomy for osteoarthritic knee. Knee. 2004;11:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeuchi R., Aratake M., Bito H. Clinical results and radiographical evaluation of opening wedge high tibial osteotomy for spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:361–368. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koshino T. The treatment of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee by high tibial osteotomy with and without bone-grafting or drilling of the lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi R., Umemoto Y., Aratake M. A mid term comparison of open wedge high tibial osteotomy vs unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. J Orthop Surg Res. 2016;201(5):65. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-5-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeuchi R., Saito T., Koshino T. Clinical results of a valgus high tibial osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee and the ipsilateral ankle. Knee. 2008;15:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koshino T. Osteotomy around young deformed knees: 38-year super-long-term follow-up to detect osteoarthritis. Int Orthop. 2010;34:263–269. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0873-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakase T. Basic principle of deformity correction, Osteotomy, Mechanical axis, Joint orientation. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 2013;87:572–586. In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herzenberg J. Rotation and angulation-rotation deformities. In: Paley D., editor. Principles of deformity correction. Springer-Verlag; Heiderberg: 2002. pp. 235–268. [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Soest T., Kvalem I.L., Skolleborg K.C. Psychosocial changes after cosmetic surgery: a 5-year follow-up study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:765–772. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822213f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Soest T., Kvalem I.L., Roald H.E. The effects of cosmetic surgery on body image, self-esteem, and psychological problems. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:1238–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wildgoose P., Scott A., Pusic A.L. Psychological screening measures for cosmetic plastic surgery patients: a systematic review. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:152–159. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12469532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin Z., Wang D., Ma Y. Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and appearance assessment of young female patients undergoing facial cosmetic surgery: a comparative study of the Chinese Population. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;15:1–7. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2015.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golightly Y.M., Allen K.D., Renner J.B. Relationship of limb length inequality with radiographic knee and hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15:824–829. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey W.F., Yang M., Cooke T.D. Association of leg-length inequality with knee osteoarthritis: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:287–295. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma L., Song J., Dunlop D. Varus and valgus alignment and incident and progressive knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1940–1945. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.129742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanamas S., Hanna F.S., Cicuttini F.M. Does knee malalignment increase the risk of development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:459–467. doi: 10.1002/art.24336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]