Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) signaling has essential roles in the development of the nervous system from neural induction to the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of neural cells. Ca2+ signaling pathways are shaped by interactions among metabotropic signaling cascades, intracellular Ca2+ stores, ion channels, and a multitude of downstream effector proteins that activate specific genetic programs. The temporal and spatial dynamics of Ca2+ signals are widely presumed to control the highly diverse yet specific genetic programs that establish the complex structures of the adult nervous system. Progress in the last two decades has led to significant advances in our understanding of the functional architecture of Ca2+ signaling networks involved in neurogenesis. In this review, we assess the literature on the molecular and functional organization of Ca2+ signaling networks in the developing nervous system and its impact on neural induction, gene expression, proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Particular emphasis is placed on the growing evidence for the involvement of store-operated Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels in these processes.

Keywords: Calcium, Stem cells, Neural development, STIM1, Orai1, CRAC channel

1. Introduction

The development of the nervous system occurs through a series of carefully choreographed steps in which neural stem/progenitor cells (NSCs) proliferate, migrate considerable distances from the germinal centers to their destinations, and ultimately differentiate into billions of neurons and glia that populate the brain. As these events unfold, rhythmic bursts of Ca2+ signals in the developing cells direct specific cellular Ca2+ responses to influence each step of this process. Cellular Ca2+ signals regulate nearly every aspect of neural development including neural induction [1], proliferation [2,3], migration [4], and differentiation [5]. A multiplicity of Ca2+ signaling proteins expressed in the developing brain create diverse Ca2+ signals to accommodate these processes [6]. The prototypical components of this toolkit include G-protein-coupled (GPCRs) and tyrosine kinase-linked receptors (RTKs) that sense extracellular cues, and numerous Ca2+-permeable channels that flux Ca2+ into the cell through the plasma membrane or that release Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Downstream of Ca2+ entry are Ca2+-binding effector proteins such as calmodulin, and Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors, enzymes, and ion channels which mediate effector functions. Finally, Ca2+ pumps and exchangers refill Ca2+ stores or extrude Ca2+ from the cell to maintain the resting intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). The temporal and spatial characteristics of the Ca2+ signal created by the concerted actions of all these Ca2+ signaling components encode specific messages that control the types of cellular programs that are activated [7,8]. This review summarizes our current understanding of the major pathways of Ca2+ influx that orchestrate the key effector functions of neural development (Fig. 1). A particular focus of this review is on the organization and functional role of store-operated CRAC channels in these development processes.

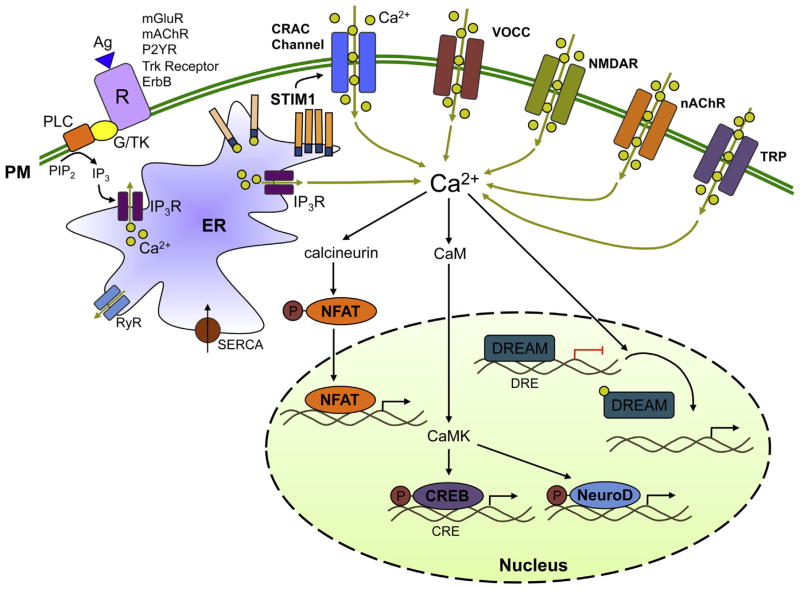

Fig. 1. Calcium signaling pathways in neural progenitor cells.

Extracellular agonists (Ag) bind to cell surface receptors (R), including G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) such as mGluR, mAChR, and P2YR, and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as Trk receptors and ErbB receptors. GPCRs activate phospholipase C (PLC)-β and RTKs activate PLCγ through G protein (G) or tyrosine kinase-coupled pathways (TK), respectively. PLC cleaves PIP2 to produce IP3, which mobilizes Ca2+ from ER stores via IP3R Ca2+ release channels. Upon store depletion, the luminal EF-hand domain of STIM1 senses the loss of ER [Ca2+], triggering STIM1 to oligomerize and translocate from the bulk ER to plasma membrane-ER junctions where it activates store-operated Ca2+ entry through CRAC channels. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VOCCs) mediate Ca2+ influx in response to membrane depolarization. NMDA receptors (NMDAR) and nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChRs) are Ca2+-permeable channels that are activated by neurotransmitters glutamate and ACh, respectively. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are Ca2+-permeable channels that are activated by a wide variety of stimuli. These Ca2+ influx pathways contribute to a rise in cytosolic [Ca2+]i, which activates various Ca2+-dependent downstream gene expression pathways through regulation of transcription factors such as NFAT, CREB, NeuroD, and DREAM. Activation of these pathways has been linked to proliferation, migration, and differentiation of neural progenitor cells.

2. The molecular and functional organization of Ca2+ signaling

2.1. Spatial organization of Ca2+ signaling

At rest, the cytosolic concentration ([Ca2+]i) in eukaryotic cells is maintained at very low levels (50–100 nM). The opening of plasma membrane or organelle Ca2+ channels results in a sudden rise in [Ca2+]i which alters the conformation of numerous nearby proteins and enzymes to initiate biological responses [6]. The wide range of cellular functions regulated by cellular Ca2+ signals begets the question of how selectivity is encoded by such a promiscuous messenger. One solution to this problem, it appears, is surprisingly simple: the spatial profile of the Ca2+ signal delivers a targeted message to control the type of downstream response. Local Ca2+ signals, or Ca2+ microdomains, develop rapidly near open Ca2+ channels, creating spatial Ca2+ gradients of high [Ca2+]i near the open pore which can reach tens of micromolar [9,10]. The subsequent diffusion of Ca2+ away from the source is limited by cytoplasmic buffers and membrane pumps such that [Ca2+]i declines steeply with distance [9,11]. Hence, localization of Ca2+ signaling complexes and downstream effectors in close proximity to the Ca2+ channels provide a means for rapid and specific activation of Ca2+-dependent responses. These concepts are supported not only by modeling studies [9,10], but also the differential effects of fast and slow Ca2+ chelators such as BAPTA and EGTA on the activation of Ca2+-dependent cellular responses. Disruption of a Ca2+-sensitive process by millimolar concentrations of BAPTA but not EGTA indicates that the process is located within tens of nanometers from the pore of a nearby Ca2+ channel [12,13]. Thus, for many Ca2+-mediated functions, the physiological response is determined by the spatial relationship between Ca2+ channels and their Ca2+-sensitive effectors.

For example, at many central synapses, the rapid release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic terminals is due to highly localized Ca2+ elevations established by tight molecular coupling of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel to a Ca2+ sensor at the transmitter release site [12,14]. This specialized coupling is organized by a protein scaffold that physically tethers Ca2+ channel to synaptic vesicle [15]. Since the rate of vesicle exocytosis is steeply dependent on [Ca2+] [16], the compartmentalization of Ca2+ into local signaling domains has important consequences for regulating neurotransmitter release and synaptic strength [17,18]. Another type of specialized coupling arises from the spatial summation of Ca2+ entering from a cluster of multiple channels. In vestibular hair cells, adrenal chromaffin cells, and at the neuromuscular junction, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel microdomains are functionally associated with voltage-and Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels [19–21]. The two classes of ion channels are physically assembled into macromolecular channel–channel complexes that underlie their functional relationship [13,21]. As with synaptic vesicles, the close interaction between Ca2+ channels and BK channels ensure rapid and robust effector activation.

In an interesting extension of local coupling, Ca2+ sensors can detect local signals and relay the signal to targets located outside the microdomain. Of particular importance of this type of coupling to neural developmental is the control of gene expression by localized Ca2+ signals through L-type Ca2+ and store-operated CRAC channels [22,23]. In these examples, a Ca2+ signal at the mouth of the Ca2+ channel activates a Ca2+ sensor (e.g., calmodulin), which in turn activates distal signaling pathways (MAP kinase or calcineurin/NFAT) resulting in gene expression in the nucleus [22,23] (as discussed further below). The mechanisms underlying the operation of these diverse localized Ca2+-driven cellular responses are likely to be pervasive throughout nervous system development and in the mature nervous system.

2.2. Store-operated calcium entry

Of the many mechanisms of Ca2+ entry found in animal cells, one of the most widespread is store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) [24]. Store-operated channels (SOCs) are so named because they are activated by the depletion of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [25]. They deliver Ca2+ to refill ER stores as well as evoke sustained Ca2+ signals that drive a wide range of effector functions including gene expression, secretion, and motility [24]. Physiologically, SOC activation is triggered through the stimulation of GPCRs or RTKs which act through the phospholipase C (PLC)-inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) signal transduction pathway to stimulate the release of Ca2+ from ER stores via IP3R Ca2+ release channels. The Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel, encoded by the Orai pore proteins (Orai1-3) and activated by the ER Ca2+ sensors STIM1 and STIM2, is the most extensively characterized store-operated channel [24,26–28].

The complex choreography of SOCE activation and the calcium current (ICRAC) underlying SOCE is well characterized in many cell types [29]. Upon store-depletion, the luminal EF-hand domain of STIM1 senses the loss of bound Ca2+, triggering a conformation change in STIM1 that leads to the oligomerization and translocation of STIM1 to plasma membrane (PM)-ER junctions where it forms distinct puncta [30–32] (Fig. 1). Orai1 also redistributes within the PM to accumulate at sites opposite to STIM1 [33]. This juxtaposition is mediated by direct interactions between STIM1 and Orai1, leading to Orai1 channel activation [34,35]. The ensuing Ca2+ entry into the cytosol is taken up into the ER by the sarco-endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump. Refilling of ER stores is again sensed by STIM1, resulting in dissociation of the Orai1-STIM1 complex and deactivation of the Ca2+ channel [36]. Each time an agonist stimulates ER Ca2+ release, a fraction of the released Ca2+ is transported out of the cell by plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase pumps (PMCA) and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Therefore, SOCE plays a homeostatic role in ensuring adequate repletion of the ER Ca2+ stores. CRAC channels also play an active role in inducing both short-term (i.e., maintenance of cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations, secretion) as well as long-term (i.e., gene expression) signaling pathways [37].

CRAC channels are endowed with many distinguishing biophysical and regulatory features that make them uniquely suited to generate these Ca2+ signals. These features include high Ca2+ selectivity and low unitary conductance [24,38]. CRAC channels are not voltage-dependent and can therefore conduct Ca2+ at negative membrane potentials, when voltage-sensitive channels such as voltage-gated Ca2+ (Cav) channels or NMDAR channels are inactive. Their small unitary conductance coupled with their extremely high Ca2+ selectivity and tight localization at PM-ER junctions enables these channels to form a highly efficient and selective Ca2+ influx mechanism, uniquely poised to create Ca2+ microdomains that activate specific Ca2+ response pathways. Furthermore, the kinetics of CRAC channel activation and deactivation occurring on slow time scales of tens of seconds to minutes are well suited for mediating oscillations and Ca2+ waves that are commonly required to drive key events in development such as gene transcription and cell proliferation. For example, CRAC channels are functionally coupled to the activation of NFAT and c-fos [2,22,39], leukotriene production [40], and PMCA [41].

When expressed heterologously together with STIM1 in HEK293 cells, the three Orai isoforms (Orai1-3) that make up the CRAC channel family produce store-operated currents with only modest differences in their inactivation properties and pharmacology [42,43]. Still, Orai1 remains the best-studied member of the class with numerous mouse models generated to study its role in SOCE in different tissues and a growing list of loss- and gain-of-function mutations linked to human disease [44]. By contrast, there are no genetic models for Orai2 or Orai3 nor have they been conclusively implicated in SOCE in any cell type to date. The three Orai proteins (Orai1-3) are broadly expressed in many tissues and organs including the brain [45–47] and in the murine nervous system, the expression of Orai2 and Orai3 is particularly noteworthy in the cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum [42,45,48] (Allen Brain Atlas). Further, both in the brain and in other tissues, the expression of Orai1 overlaps with that of Orai2 and/or Orai3, raising the possibility of heteromeric channels composed of multiple Orai isoforms [49,50]. Heteromeric Orai3-Orai1 channels have been reported to show sensitivity to activation by arachidonic acid when expressed in HEK293 cells [51], raising the possibility that such channels may display activation behaviors distinct from canonical store-operated channels. Thus, an interesting possibility is that these differences in gating and regulation give rise to the functional diversity of Ca2+ signals noted in different cell types. These and other possibilities require further study using specific mouse models.

Historically, CRAC channels were first described in immune cells and other nonexcitable cells lacking the ability to fire action potentials [reviewed in ref. [24]]. However, they are now known to be present in virtually all cells, and a growing literature on SOCE implicates them in the regulation of numerous Ca2+-mediated functions in the brain [52–56]. Given the neuroectodermal lineage and nonexcitable nature of neural stem/progenitors cells, CRAC channels may have a particularly important role for neurodevelopmental processes including neurogenesis, proliferation, and migration (as discussed further below).

2.3. Spontaneous Ca2+ transients and oscillations

Oscillatory Ca2+ signals generated by periodic discharges of Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx are a widespread presentation of cellular Ca2+ signaling through all stages of neural development and are implicated in driving numerous genetic programs [3,8] including proliferation, migration, and differentiation [5,57–60]. For example, in the embryonic mouse neural crest, spontaneous Ca2+ transients establish a neuronal preference for undifferentiated neural crest cells [61]. In the embryonic rat neocortical ventricular zone (VZ), patterns of spontaneous [Ca2+]i changes in cortical precursor cells influence neurogenesis and proliferation [62]. Likewise, in Xenopus and zebrafish spinal neurons, spontaneous Ca2+ transients are present at early stages and regulate axonal growth and differentiation [7,63,64] as well as neurotransmitter phenotype of developing neurons [65]. The downstream effects of these Ca2+ signals are thought to be mainly achieved through regulation of activity of transcription factors and intermediate signaling proteins.

Experimental and computational models indicate that the periodic discharges of Ca2+ arise from coordinated interplay of Ca2+ influx and release from intracellular Ca2+ stores [66,67]. Oscillations generally dissipate in the absence of Ca2+ entry [68–70], indicating a requirement of Ca2+ influx for the maintenance of these Ca2+ signals. Among the various molecules implicated in the Ca2+ influx necessary to sustain oscillations are voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and neurotransmitter-gated receptors such as GABA and glutamate. At earliest stages, before synapses have formed in the developing brain, glutamate and GABA signal through NMDA and GABAA receptors in a paracrine, nonsynaptic mode of intercellular communication [71,72] to elevate [Ca2+]i. GABA activates depolarizing chloride currents which can open voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, while ligand-gated glutamate receptors generate Na+ and Ca2+ influx [73,74]. TRP channels [75], metabotropic transmitter receptors [59,76], and mechanoreceptors [77] also generate spontaneous Ca2+ transients that direct neural development. Few studies have as yet examined the potential role of Orai channels for Ca2+ oscillations in neural development. However, a study in mouse neural progenitors found that elimination of Orai1 activity through knockin of a loss of function Orai1 mutation (R93W) abrogates Ca2+ oscillations seen in heterozygous WT/R93W Orai1 mice [2], suggesting that CRAC channels may be critically important for generating Ca2+ oscillations in the developing nervous system.

It is generally believed that oscillations offer an advantage over sustained Ca2+ signals in driving many types of effector responses due to the high signal-to-noise discrimination by the effector proteins for digital signals [78–80]. High Ca2+ thresholds of the effector responses coupled with slow activation kinetics allow for discrimination of true Ca2+ inputs from stray events. In this manner, the signature of the oscillatory signal (frequency, duration, amplitude) also offers a way to discriminate between particular end points that co-exist in the same cell [7,61,78,81]. One of the best-described examples of this type of discrimination is the dependence of the efficacy and specificity of gene expression of the NFAT, NFkB, and Oct1-OAP transcriptional pathways on oscillations of specific frequency and amplitude [78].

3. Physiological roles of Ca2+ signaling in neural development

As described in the preceding sections, numerous ion transport pathways are implicated in regulating neurogenesis, from proliferation and migration of neural progenitor cells to differentiation. Below we describe the functional role of specific Ca2+ pathways that have been implicated in these processes, with an emphasis on ion channels mediating Ca2+ influx. Table 1 provides a list of the Ca2+ proteins and ion transports mechanisms that are discussed in the following sections.

Table 1.

Ca2+ mobilization pathways in neural development.

| Channel | Cell types and stages expressed | Physiological role | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage-operated Ca channels (VOCCs) | |||

| L-type Ca2+ (DHP-Ca2+) channel | Xenopus ectoderm cells at blastula stage → end of gastrulation | Neural competence/neural induction | [84–86] |

| Gene expression/cell fate | [87,91] | ||

| Zebrafish embryonic spinal cord interneuron progenitors | Neuronal fate/differentiation (secondary to glycinergic depolarization) | [173] | |

| Mouse postnatal NSCs | Neuronal differentiation | [132] | |

| Mouse/Rat NSCs | Neuronal differentiation, through increased expression of NeuroD | [122,172,174] | |

| L-type/N-type Ca2+ channel | Mouse cortical neurons | Termination of migration | [156] |

| Cerebellar granular neurons | Neuronal migration | [153,154] | |

| Receptor-operated channels (ROCs) | |||

| NMDA glutamate receptor | Mouse embryonic cortical neurons of VZ/SVZ | Neuronal precursor migration | [72,176] |

| Rat adult NSCs | Neuronal fate/differentiation | [122] | |

| Nicotinic ACh receptor | Mouse cortical NSCs | Early cortical development | [135] |

| GABAA receptor | Mouse postnatal cortical neurons of SVZ | Reducing neuronal precursor migration speed | [177] |

| Immature cerebellar granule cells | Proliferation (secondary to Ca2+ influx via VOCCs) | [178] | |

| Store-operated Ca channels (SOCCs) | |||

| Orai1/STIM1 | Mouse embryonic and adult NSCs | Proliferation and gene expression | [2] |

| G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) | |||

| mGluR5 | Mouse immature cortical neurons | Spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations/gene expression | [76] |

| Mouse adult hippocampal NSCs | Proliferation | [150] | |

| P2YR1 | Mouse NSCs | Proliferation | [129,130,158] |

| Rat radial glial cells in the cortical VZ | Proliferation (through IP3-mediated Ca2+ release) | [59] | |

| Mouse intermediate neural progenitors | Migration from the VZ to SVZ | [157] | |

| mAChR | Rat embryonic cortical NSCs | Proliferation | [138,140] |

| Inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) | Mouse neural crest | Neuronal differentiation | [61] |

| Human NSCs | Cell cycle length/neurogenesis | [179] | |

| Gap junctions | |||

| Connexin 43 | Rat radial glial cells in the cortical VZ | Proliferation | [59] |

| Mouse forebrain precursors | Interkinetic nuclear migration | [154] | |

| Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels | |||

| TRPC3 | Mouse embryonic NSCs | Radial glial-mediated neuronal migration | [180] |

| TRPC1 | Rat embryonic neural stem cells | Proliferation | [127] |

| Stretch channels | |||

| Piezo1 | Human embryonic NSCs | Lineage specification (neurogenesis) | [77] |

| Channel regulators | |||

| Calfacilitin | Chick embryo neural plate | Neural plate development | [96] |

| Neuronatin | Xenopus early neuroectodermal cells | Neural induction | [93] |

3.1. Early neurogenesis

The formation of the vertebrate nervous system is initiated during gastrulation in a process called neural induction, when the cells of the embryonic ectoderm choose neural fate over epidermal fate and give rise to neural progenitors. This decision of cell fate involves inductive signals from a specialized cluster of cells in the dorsal mesoderm called the ‘neural organizing center,’ which triggers neural development in the dorsal ectoderm [82]. A critical signaling mechanism involved in the development of neuroectoderm from the ectoderm is the inhibition of the potent epidermal-inducer, BMP, by factors secreted from the dorsal mesoderm—noggin, chordin, and follistatin [82]. There is increasing evidence that Ca2+ signaling has an instructive role in the initiation of the neuroectoderm-specific gene expression programs [83]. In amphibians for example, an increase in [Ca2+]i is both necessary and sufficient to commit the ectoderm to a neural fate during embryo development [84]. In Xenopus laevis embryos, direct visualization of Ca2+ dynamics revealed localized domains of Ca2+ transients restricted to the dorsal ectoderm cells, just prior to the onset of neural induction in these cells [85]. In contrast, [Ca2+]i elevations are not observed in the ventral ectoderm or mesoderm during this time. Studies in amphibians have found that L-type (or dihydropyridine-sensitive) Ca2+ channels in the ectoderm are required for the acquisition of neural fate [85–87]. Moreover, the temporal pattern of channel expression correlates with neural competence; the ability of the ectoderm cells to differentiate toward neural tissue is optimal when the L-type Ca2+ channel density is highest [86]. Further, the neural inducer noggin has been shown to activate Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels to induce transcription of the immediate early gene (IEG) c-fos [88]. The protein encoded by c-fos interacts with the product of another IEG, Jun, to form a heterodimeric transcription factor and has been implicated in the control of cell cycle entry, cell proliferation, and neural differentiation [88–90], suggesting that Ca2+ signals promote neural fate by modulating signal transduction pathways that control gene expression. Indeed, Ca2+ transients also regulate the expression of early proneural genes such as Zic3 [85,91]. In amphibian embryos and animal caps, the Ca2+-regulated arginine N-methyltransferase xPRMT1b has been implicated as a direct link between [Ca2+]i increase and the induction of neural fate [92]. The overexpression of xPRMT1b induces the expression of Zic3 and the neural differentiation marker N-tubulin. Expression of these genes likely involves Ca2+-mediated gene transcription as discussed further below.

In mammals, an increase in [Ca2+]i also appears to be the key signal that controls neural fate determination [93]. However, while the main source of Ca2+ increase in amphibian ectoderm is influx through voltage-operated Ca2+ channels, mammalian embryonic stem cells do not express VOCCs and therefore must employ alternate pathways [94,95]. Indeed, Yanagida et al., observed store-operated Ca2+ currents in mouse embryonic stem cells [94] which was attributed to TRPC channels based on the detection of TRPC1 and TRPC2 mRNA. However, at the time of that study, the molecular identity of the SOC had not yet been determined and the potential role of the CRAC channel family in mediating these store-operated currents was not evaluated. More recently, a screen to identify neural induction genes in mammals identified neuronatin (Nnat), an ER membrane protein that physically antagonizes SERCA2 activity to regulate the intracellular Ca2+ level [93]. Knocking down Nnat inhibits neural induction in ESCs by reducing the level of intracellular Ca2+. Together, these results suggest that a key source of Ca2+ for neural induction involves intracellular stores, and potentially, SOCE. Recently, the CRAC channel family was shown to be an important Ca2+ entry mechanism for gene expression in embryonic and adult neural stem/progenitor cells [2], but its potential role in regulating the induction of early neural genes remains to be explored.

After neural induction, the neuroectoderm forms the neural plate, which consists of neuroepithelial/neural stem cells that are the precursors to neural tissue. These neuroepithelial cells are successively replaced by radial glial cells, the main progenitor cell type during development of the embryonic and postnatal CNS. The progenitor cell bodies are contained in the ventricular zone (VZ) and through cycles of self-renewal and differentiation will give rise to most of the neurons as well as glial cells in the brain. Recently, Papanayotou et al. described a novel L-type Ca2+ channel modulator called calfacilitin that is required for neural plate development in the chick embryo [96]. Calfacilitin binds to L-type CaV1.2 channels to slow inactivation thereby facilitating Ca2+ infux, which leads to increased expression of neural plate specifier genes Geminin and Sox2.

3.2. Gene expression

A major mechanism controlling neurogenesis is the regulated expression of specific genes driven by extracellular cues. Ca2+ signals mediate a key role in this process by activating signaling pathways that converge on transcription factors which then initiate the expression of a large number of proteins critical for proliferation, migration, and differentiation [97]. Ca2+-dependent activation of transcription factors can occur either directly through Ca2+ interaction with transcription factors that are pre-bound to their targets, or indirectly through Ca2+-sensitive proteins that affect transcription factor activity. A well-known example of the former is Ca2+ regulation of the transcription factor, Downstream Regulatory Element (DRE) Antagonist Modulator (DREAM) [98]. DREAM is a Ca2+ sensor with four EF-hand Ca2+-binding domains and it acts as a transcriptional repressor by binding DNA at DRE sequences. Ca2+ stimulation abolishes DREAM’s ability to bind DRE and repress transcription. DREAM is highly expressed in the brain and regulates transcription of the early immediate gene c-fos [98] as well as expression of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels [99].

Among the indirect pathways, a well-characterized example is Ca2+ regulation of the NFAT family of transcription factors. NFAT activation is indirectly coupled to Ca2+ mobilization: Ca2+ elevations activate the phosphatase calcineurin, which dephosphorylates NFAT, causing NFAT to translocate to the nucleus where, working in conjunction with the fos/jun complex, it controls a wide variety of genes in diverse cell types [100]. First shown to be important in the immune system, NFAT is now known to be widely expressed in the nervous system, although its role in neuronal development is only recently beginning to be understood [101]. At the molecular level, NFAT-directed gene transcription regulates the expression of several key proteins critical for activity responses including IP3Rs, GluRs, and pro-nociceptive genes in neurons [102–104]. Calcineurin-NFAT signaling is critical for neurotrophin-mediated axonal growth and guidance during vertebrate development [105,106] as well as presynaptic development [107], dendritogenesis [108], and neuronal survival [107–110].

Several sources of Ca2+ entry have been shown to regulate NFAT activity. In cortical and hippocampal neurons, for example, neurotrophins binding to Trk receptors activate PLC-IP3 signaling, causing an increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels that activate NFAT transcription via calcineurin [103,105]. Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels has also been shown to activate NFAT, which is especially critical for excitation-dependent gene transcription underlying functions such as synaptic plasticity [111]. Further, influx of Ca2+ through NMDA receptor regulates neuronal survival in the cortex through an NFAT-dependent survival pathway [110]. In neural stem/progenitor cells, CRAC channels have a prominent role in activating NFAT-dependent gene expression. Ca2+ signaling through CRAC channels stimulates the nuclear translocation of NFAT and NFAT-dependent gene transcription, with murine knockouts of Orai1 and/or STIM1 showing impaired NFAT-dependent gene transcription [2]. Interestingly, the differential effects of BAPTA and EGTA indicate that NFAT activation is stimulated by local Ca2+ signals around CRAC channels, suggesting that calcineurin may be physically associated with CRAC channels [2]. This finding is similar to the spatial coupling observed between CRAC channels and NFAT activation in HEK cells and between L-type Ca2+ channels and NFAT activation in hippocampal neurons [39,112]. The molecular basis for the tight coupling between calcineurin and the Ca2+ channel appears to involve the anchoring protein AKAP79, which targets calcineurin to calmodulin-bound Ca2+ channels, so that local Ca2+ entering at the plasma membrane can effectively and selectively activate calcineurin/NFAT signaling to the nucleus [112,113].

cAMP response element binding (CREB) protein is another important transcription factor whose transcriptional activity is regulated by calcium-activated signaling pathways and which mediates responses to extracellular cues and local activity in the developing brain [114]. Multiple signaling pathways converge onto CREB including cAMP dependent protein kinase A and Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs), which activate CREB activity by phosphorylation at three critical serine residues (Ser-133, Ser-142 and Ser-143). Ser-133 has been examined extensively and the prevailing evidence shows that this residue becomes phosphorylated by a wide range of stimuli, both Ca2+-dependent and independent [115]. However, Ser-142 and Ser-143 are phosphorylated strictly in a Ca2+-dependent manner [116]. CREB regulates a wide range of biological processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, and cell survival [115,117]. For example, in the rat embryonic subventricular zone, the action of the second messenger cAMP downstream of GPCR signaling supports the differentiation of neural progenitor cells via up-regulation of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Moreover, cAMP signaling in conjunction with Ca2+ entry through VOCCs promotes the morphological and functional maturation of NSCs, an effect dependent on CREB activation [118]. Activated CREB is largely absent in stem cells, and transiently upregulated in NSCs and young neurons during the first few weeks of differentiation [119]. Loss of CREB signaling results in cell death and loss of neuronal gene expression [120]. These wide-ranging roles of CREB for circuit development are likely mediated by several cofactors that interact with phosphorylated form of CREB, and which in many cases are themselves regulated by Ca2+ (e.g., the CREB binding protein, CBP) [115].

A hallmark of neurogenesis is the expression of the basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) proneural genes which are critical for cell fate determination and differentiation of progenitor cells. NeuroD is a bHLH transcription factor that plays an important role in the survival and differentation of many neuronal tissues including the hippocampal dentate gyrus neurons, cerebellar granule neurons, and developing inner ear neurons. Studies have suggested that NeuroD acts as a Ca2+-regulated transcription factor [121,122]. In cerebellar granule neurons, neuronal activity stimulates Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated calcium channels to induce CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of NeuroD and thereby stimulate dendritic growth [121]. In adult neural progenitor cells, excitation is coupled to neurogenesis through L-type Ca2+ channel activation, which increases expression of NeuroD and inhibits expression of glial fate genes [122]. Thus, in both embryonic and adult neural progenitor cells, Ca2+ signaling regulates specific transcriptional networks to drive specific steps of neurogenesis.

3.3. Proliferation

Calcium signaling regulates many fundamental steps of the cell cycle, including the transitions between the various phases of the cell cycle, the transcription of immediate early genes, and the regulating events that control quiescence and cell division [123–125]. In the brain, the niche of proliferating cells comprise primarily three cell types: type B cells (most stem-like), type C cells (transient amplifying cells), and type A cells (migrating neuroblasts) (Fig. 2). Type B cells are slowly dividing and give rise to the rapidly proliferating type C cells (TAPs) through asymmetric division. Type C cells then go on differentiate into type A cells which acquire a migratory phenotype that is then associated with a decline in proliferation [126]. Proliferation of these progenitors is regulated by a variety of extrinsic factors that include the growth factors EGF and FGF [127–129] and neurotransmitters that evoke Ca2+ elevations [59,73,130,131], likely through specific ion transport pathways in each cell type. Some studies have implicated voltage-gated Ca2+ channels as an important route of Ca2+ entry in late stage neural precursors [132]. However, NSCs are derived from non-excitable epithelial cell lineage and are thus more akin to non-neuronal cell types in terms of Ca2+ influx [133], raising the possibility that CRAC channels could function as a major Ca2+ regulatory mechanism to regulate NSC proliferation.

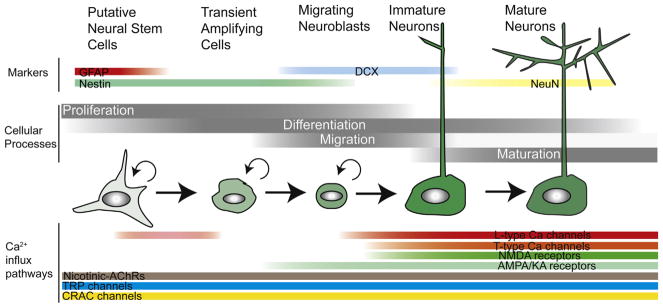

Fig. 2. Schematic of the different stages of neurogenesis in the developing brain.

Neurogenesis proceeds through several overlapping stages: proliferation, differentiation, migration, and maturation. The Ca2+ influx pathways expressed during these stages are indicated. Commonly used immunohistological markers for staging neurogenesis are also shown above.

Indeed, consistent with this possibility, we have found that CRAC channels encoded by Orai1 and STIM1 comprise the major mechanism for the sustained and oscillatory Ca2+ signals activated by EGF and the neurotransmitter, ACh, in mouse subventricular zone NSCs [2]. STIM1 and Orai1-mediated SOCE is seen in NSCs at every age (embryonic, neonatal, and adult NSCs), indicating that this Ca2+ entry mechanism is conserved throughout development and is preserved well into adulthood. Knockin of a non-functional Orai1 mutant (R93W Orai1) or conditional knockouts of Orai1 in the brain severely impaired NSC proliferation both in vitro and in vivo [2], indicating that CRAC channels have a major influence on the proliferation of subventricular NSCs. Although not formally proven, these effects are likely mediated by calcineurin/NFAT-mediated transcription of cell cycle proteins as inhibiting calcineurin/NFAT signaling also evoked impairment of proliferation comparable to that seen with loss of CRAC channel function [2]. These findings establish CRAC channels as a novel mechanism for regulation of Ca2+ signaling, gene expression, and proliferation in NSCs. Because NFAT is upregulated in hypoxia-treated NSCs [134], these results raise the possibility that CRAC channel-mediated regulation of calcineurin/NFAT signaling may also be important for regulating the proliferative response seen following brain injury.

Signaling through cholinergic receptor pathways also plays a major role in neuronal cell proliferation [131]. Acetylcholine (ACh) is present in the brain prior to synaptogenesis and the onset of neurotransmission, suggesting that its action is mediated via non-classical neurotransmitter signaling. Both muscarinic (mAChRs) and nicotinic (nAChRs) acetylcholine receptors are expressed in neuronal progenitor cells [135–139] and their activation is known to increase proliferation and neurogenesis [138,140] likely through stimulation of SOCE [2]. AChRs induce Ca2+ influx, which can stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and ERK signaling pathways that govern proliferation and DNA synthesis [138,139,141–144]. Intracellular Ca2+ can modulate the MAPK cascade through two mechanisms—calcium-dependent tyrosine kinase (PYK2) or calmodulin—that converge upon the Ras pathway leading to MAPK activation [145]. An increase in intracellular Ca2+ evoked by thapsigargin is sufficient to induce ERK activation to levels similar to those induced by AChR agonists, underlying the importance of Ca2+ in this pathway [146].

In addition to CRAC channels and the aforementioned cholinergic pathways, other influx mechanisms including TRP channels are also implicated in Ca2+ influx and regulation of proliferation of neural progenitors [75]. Interestingly, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels do not seem to play a role until later stages of NSC development [127,132,147,148] (Fig. 2). These late-stage progenitors become sensitive to GABAergic transmission, which acts as a depolarizing stimulus—opposite to what is seen in mature neurons where GABA is inhibitory. GABAergic signaling appears to be paired with increased expression of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and loss of either excitatory GABAergic transmission or voltage-gated Ca2+ channels lead to diminished proliferation [148,149], highlighting the importance of this transition for progenitor function. In addition, glutamatergic signaling involving both metabotropic glutamate receptors [150] as well as NMDA receptors is implicated in the proliferation of DCX positive late stage progenitors [122]. Both NMDA receptor blockade as well as inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels impair proliferation of hippocampal progenitors [122], suggesting a growing importance of activity dependent pathways for nurturing and tuning the proliferative response.

3.4. Migration

A key step in neurodevelopment, one that is also seen following brain injury, is the directed migration of NSCs to widespread and distant areas of the brain. Precise migration of NSCs is regulated by a complex interplay of cell-autonomous programs and environmental factors in which Ca2+ signaling has a critical role. Studies in immune cells have previously shown that Ca2+ signaling regulates the migration of hematopoetic cells, in this case functioning as a stop signal [151]. In the thymus, elevations in intracellular Ca2+ are sufficient to arrest the motility of migrating thymocytes, a feature that may enable developing T-cells to interact more effectively with antigen presenting cells [152]. The role of Ca2+ in NSCs is more complicated as it appears that Ca2+ signaling has an important influence both for initiating the transition of highly proliferating NSCs to a migratory phenotype as well as motility itself [4,60]. In the development of the cerebellum, for example, the appearance of N-type Ca2+ channels is associated with migration of granule cells [153]. Ca2+ influx through N-type Ca2+ channels is believed to induce specific Ca2+ fluctuations whose amplitude and frequency control the rate of cell migration [154]. However, in the neurogenic region of the subventricular zone, NSCs appear to require low levels of activity, possibly involving gap junctions, to maintain their migratory behavior [155,156]. As NSCs arrive at the sites where they are ultimately incorporated, they exhibit increased Ca2+ signaling which arrests their migratory phenotype [156]. Although more studies are needed to understand the basis of the various results, one possibility is that Ca2+ both facilitates and inhibits migration based on its amplitude and kinetic signature. Low to modest levels of Ca2+ signaling may be required to sustain migratory behavior, but high levels may function to stop motility [156].

Among various extrinsic factors, purinergic agonists [157,158], growth factors [159], and chemokines [160–162] are well-known modulators of NSC migration. For example, ATP regulates the migration of intermediate neuronal progenitors from the ventricular zone to the subventricular zone by acting through the purinergic P2Y1 receptor [157]. Progenitor cells in the ventricular zone are extensively coupled in clusters via gap junctions and can communicate with neighboring cells by releasing ATP through gap junctions/hemichannels [163]. Genetic knockdown of the P2Y1 receptor or blockade of ATP signaling by P2Y1 inhibitors reduces Ca2+ transients in intermediate progenitor cells and impairs their migration to the subventricular zone [157]. Likewise, numerous trophic and differentiation factors regulate neuronal migration. For example, one study has shown that neuregulin1 (NRG1), a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family that binds to the tyrosine kinase ErbB4, evokes intracellular signaling that induce migration of neuronal progenitor cells [164]. NRG1/ErbB4 signaling is involved in tangential migration of olfactory bulb interneuron precursors in the rostral migratory stream [165] and in migration of cortical interneuron precursors from the ventral telencephalon [166]. Mechanistically, NRG1 stimulation of ErbB4 results in a sustained [Ca2+] increase in neural progenitors which involves store-operated calcium entry [159]. NRG1-induced migration is dependent on Ca2+ influx and is positively regulated by NMDAR activation [159]. It is known that local polarization of Ca2+ elevation can confer proper directionality [167] suggesting that extrinsic chemical gradients might be sensed using finely tuned local Ca2+ transients. The Ca2+ entry pathways stimulated by the aforementioned extrinsic factors have not yet been identified. However, their ability to stimulate GPCRs leading to release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores raises the possibility that CRAC channel mediated Ca2+ influx may be a major mechanism of the intracellular response.

3.5. Differentiation

In addition to proliferation and migration, there is extensive evidence for a powerful influence of Ca2+ signaling for various aspects of neuronal differentiation, including the appearance of ion channels that confer neuronal excitability, neurotransmitter specification, axonal pathfinding, and dendritic outgrowth [3,63,65,168–170]. Both spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations as well as activity driven Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated N- and L type channels are implicated in these differentiation events, which is typically accompanied by the appearance of specific neurotransmitters prior to synapse formation [65,168,171]. The initiation of differentiation in the newly emerging cells occurs through induction of transcription factors that promote the expression of ion channels and receptors favoring a neuronal phenotype [3,171]. For example, one study has shown that depolarization of neural progenitors by GABAergic excitation, which would be expected to evoke activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, promotes the induction of NeuroD and neuronal differentiation while impairing proliferation [172]. A key hallmark of this process is the dependence on activity, with increases in intracellular Ca2+ enhancing the expression of ion channels, receptors, and neurotransmitters that shape the neuronal phenotype [3]. In this manner, the hard-wired stereotypic development of the early brain that is driven by cell autonomous genetic programs can be modified by activity-driven environmental cues to shape overall brain development.

4. Concluding remarks

The central role of Ca2+ signaling in directing many aspects of neurogenesis is now well accepted. This has occurred in large part through the development of new tools including genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators that have transformed our understanding of how Ca2+ signals are generated, compartmentalized, and dissipated. Several key molecular players mediating Ca2+ signaling including the molecules of SOCE and nature of the signals linking the opening of these channels to downstream effector responses have been identified. A large body of literature also exists about the properties of numerous Ca2+ signals at different stages of neuronal development and their roles for cell autonomous functions such as gene expression or cell proliferation. The largest area of uncertainty perhaps relates to how Ca2+ signaling networks regulate the development of specific neuronal circuits, and how aberrant function of particular Ca2+ signaling proteins affects the function and development of these circuits. The existence of so many routes of Ca2+ influx (STIM/Orai channels, Cav channels, TRP channels, and various ligand-gated channels) additionally begets the question of why so many pathways for Ca2+ influx are needed in the developing brain. The answer to this teleological question is likely multi-faceted. Multiple pathways are needed not only for conferring functional specificity, but also to bestow a safety net in case one pathway is compromised. Redundancy may explain why brain and T-cell development in mice lacking functional Orai1/STIM1 channels are seemingly normal despite the abrogation of SOCE. In addition, neural stem cells have been lauded for their potential to cure neurodegenerative diseases and ameliorate brain injuries. However, whether functions of particular Ca2+ signaling proteins can be controlled in ways to generate specific outcomes of therapeutic value still remains unclear. If the pace of progress in the last several years is any indication, however, it is highly probable that the ability to manipulate Ca2+ signals to selectively influence the behavior and function of neural stem cells for therapeutic applications may not be too far off.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the laboratory for helpful discussions and Priscilla Yeung for helpful comments on the manuscript. A. Toth was supported by the Julius Kahn predoctoral fellowship and A. Shum by an AHA predoctoral fellowship. Research in the laboratory is supported by NIH grants NS057499 and NS094011.

References

- 1.Moreau M, Leclerc C. The choice between epidermal and neural fate: a matter of calcium. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:75–84. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.15272372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somasundaram A, Shum AK, McBride HJ, Kessler JA, Feske S, Miller RJ, Prakriya M. Store-operated CRAC channels regulate gene expression and proliferation in neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci. 2014;34:9107–9123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0263-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spitzer NC. Electrical activity in early neuronal development. Nature. 2006;444:707–712. doi: 10.1038/nature05300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng JQ, Poo MM. Calcium signaling in neuronal motility. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:375–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg SS, Spitzer NC. Calcium signaling in neuronal development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004259. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu X, Spitzer NC. Distinct aspects of neuronal differentiation encoded by frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Nature. 1995;375:784–787. doi: 10.1038/375784a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhlen P, Fritz N. Biochemistry of calcium oscillations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neher E. Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neher E. Concentration profiles of intracellular calcium in the presence of a diffusible chelator. Exp Brain Res Ser. 1986;14:80–96. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parekh AB. Ca2+ microdomains near plasma membrane Ca2+ channels: impact on cell function. J Physiol. 2008;586:3043–3054. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Augustine GJ, Santamaria F, Tanaka K. Local calcium signaling in neurons. Neuron. 2003;40:331–346. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkefeld H, Sailer CA, Bildl W, Rohde V, Thumfart JO, Eble S, Klugbauer N, Reisinger E, Bischofberger J, Oliver D, Knaus HG, Schulte U, Fakler B. BKCa-Cav channel complexes mediate rapid and localized Ca2+-activated K+ signaling. Science. 2006;314:615–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1132915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaeser PS, Regehr WG. Molecular mechanisms for synchronous, asynchronous, and spontaneous neurotransmitter release. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:333–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaeser PS, Deng L, Wang Y, Dulubova I, Liu X, Rizo J, Sudhof TC. RIM proteins tether Ca2+ channels to presynaptic active zones via a direct PDZ-domain interaction. Cell. 2011;144:282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heidelberger R, Heinemann C, Neher E, Matthews G. Calcium dependence of the rate of exocytosis in a synaptic terminal. Nature. 1994;371:513–515. doi: 10.1038/371513a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becherer U, Moser T, Stuhmer W, Oheim M. Calcium regulates exocytosis at the level of single vesicles. Nat Neurosci. 2003;8:426–434. doi: 10.1038/nn1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bollmann JH, Sakmann B. Control of synaptic strength and timing by the release-site Ca2+ signal. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:426–434. doi: 10.1038/nn1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts WM, Jacobs RA, Hudspeth AJ. Colocalization of ion channels involved in frequency selectivity and synaptic transmission of presynaptic active zones of hair cells. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3664–3684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03664.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robitaille E, Adler EM, Charlton MP. Strategic location of calcium channels and transmitter release sites of frog neuromuscular synapses. Neuron. 1990;5:773–779. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90336-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prakriya M, Lingle CJ. Activation of BK channels in rat chromaffin cells requires summation of Ca2+ influx from multiple Ca2+ channels. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1123–1135. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Capite J, Ng SW, Parekh AB. Decoding of cytoplasmic Ca(2+) oscillations through the spatial signature drives gene expression. Curr Biol. 2009;19:853–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolmetsch RE, Pajvani U, Fife K, Spotts JM, Greenberg ME. Signaling to the nucleus by an L-type calcium channel-calmodulin complex through the MAP kinase pathway. Science. 2001;294:333–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1063395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:1383–1436. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parekh AB, Putney JW. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prakriya M, Feske S, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Rao A, Hogan PG. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2005;437:902–905. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis RS. The molecular choreography of a store-operated calcium channel. Nature. 2007;446:284–287. doi: 10.1038/nature05637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luik RM, Wu MM, Buchanan J, Lewis RS. The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:815–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luik RM, Wang B, Prakriya M, Wu MM, Lewis RS. Oligomerization of STIM1 couples ER calcium depletion to CRAC channel activation. Nature. 2008;454:538–542. doi: 10.1038/nature07065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu MM, Buchanan J, Luik RM, Lewis RS. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:803–813. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu P, Lu J, Li Z, Yu X, Chen L, Xu T. Aggregation of STIM1 underneath the plasma membrane induces clustering of Orai1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:969–976. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navarro-Borelly L, Somasundaram A, Yamashita M, Ren D, Miller RJ, Prakriya M. STIM1-Orai1 interactions and Orai1 conformational changes revealed by live-cell FRET microscopy. J Physiol. 2008;586:5383–5401. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.162503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park CY, Hoover PJ, Mullins FM, Bachhawat P, Covington ED, Raunser S, Walz T, Garcia KC, Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS. STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell. 2009;136:876–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Ca2+-store-dependent and—independent reversal of Stim1 localization and function. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:762–772. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parekh AB. Store-operated CRAC channels: function in health and disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:399–410. doi: 10.1038/nrd3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNally BA, Prakriya M. Permeation, selectivity and gating in store-operated CRAC channels. J Physiol. 2012;590:4179–4191. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.233098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kar P, Nelson C, Parekh AB. Selective activation of the transcription factor NFAT1 by calcium microdomains near Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14795–14803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.220582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang WC, Di Capite J, Singaravelu K, Nelson C, Halse V, Parekh AB. Local Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels stimulates production of an intracellular messenger and an intercellular pro-inflammatory signal. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4622–4631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bautista DM, Lewis RS. Modulation of plasma membrane calcium-ATPase activity by local calcium microdomains near CRAC channels in human T cells. J Physiol. 2004;556:805–817. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.060004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lis A, Peinelt C, Beck A, Parvez S, Monteilh-Zoller M, Fleig A, Penner R. CRACM1, CRACM2, and CRACM3 are store-operated Ca2+ channels with distinct functional properties. Curr Biol. 2007;17:794–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dehaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Putney JW., Jr Calcium inhibition calcium potentiation of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 calcium release-activated calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17548–17556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lacruz RS, Feske S. Diseases caused by mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2015;1356:45–79. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Feske S, Cruz-Guilloty F, Oh-hora M, Neems DS, Hogan PG, Rao A. Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16232–16243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gross SA, Wissenbach U, Philipp SE, Freichel M, Cavalie A, Flockerzi V. Murine ORAI2 splice variants form functional Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19375–19384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wissenbach U, Philipp SE, Gross SA, Cavalie A, Flockerzi V. Primary structure, chromosomal localization and expression in immune cells of the murine ORAI and STIM genes. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gruszczynska-Biegala J, Pomorski P, Wisniewska MB, Kuznicki J. Differential roles for STIM1 and STIM2 in store-operated calcium entry in rat neurons. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schindl R, Frischauf I, Bergsmann J, Muik M, Derler I, Lackner B, Groschner K, Romanin C. Plasticity in Ca2+ selectivity of Orai1/Orai3 heteromeric channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19623–19628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907714106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inayama M, Suzuki Y, Yamada S, Kurita T, Yamamura H, Ohya S, Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. Orai1–Orai2 complex is involved in store-operated calcium entry in chondrocyte cell lines. Cell Calcium. 2015;57:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Both Orai1 and Orai3 are essential components of the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels. J Physiol. 2008;586:185–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emptage NJ, Reid CA, Fine A. Calcium stores in hippocampal synaptic boutons mediate short-term plasticity, store-operated Ca2+ entry, and spontaneous transmitter release. Neuron. 2001;29:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baba A, Yasui T, Fujisawa S, Yamada RX, Yamada MK, Nishiyama N, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y. Activity-evoked capacitative Ca2+ entry: implications in synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7737–7741. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07737.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singaravelu K, Lohr C, Deitmer JW. Regulation of store-operated calcium entry by calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in rat cerebellar astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9579–9592. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2604-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartmann J, Karl RM, Alexander RP, Adelsberger H, Brill MS, Ruhlmann C, Ansel A, Sakimura K, Baba Y, Kurosaki T, Misgeld T, Konnerth A. STIM1 controls neuronal Ca(2+) signaling, mGluR1-dependent synaptic transmission, and cerebellar motor behavior. Neuron. 2014;82:635–644. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lalonde J, Saia G, Gill G. Store-operated calcium entry promotes the degradation of the transcription factor Sp4 in resting neurons. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blankenship AG, Feller MB. Mechanisms underlying spontaneous patterned activity in developing neural circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:18–29. doi: 10.1038/nrn2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamamoto N, Lopez-Bendito G. Shaping brain connections through spontaneous neural activity. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:1595–1604. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weissman TA, Riquelme PA, Ivic L, Flint AC, Kriegstein AR. Calcium waves propagate through radial glial cells and modulate proliferation in the developing neocortex. Neuron. 2004;43:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uhlen P, Fritz N, Smedler E, Malmersjo S, Kanatani S. Calcium signaling in neocortical development. Dev Neurobiol. 2015;75:360–368. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carey MB, Matsumoto SG. Spontaneous calcium transients are required for neuronal differentiation of murine neural crest. Dev Biol. 1999;215:298–313. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Owens DF, Kriegstein AR. Patterns of intracellular calcium fluctuation in precursor cells of the neocortical ventricular zone. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5374–5388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05374.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gomez TM, Spitzer NC. In vivo regulation of axon extension and pathfinding by growth-cone calcium transients. Nature. 1999;397:350–355. doi: 10.1038/16927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ashworth R, Bolsover SR. Spontaneous activity-independent intracellular calcium signals in the developming spinal cord of the zebrafish embryo. Dev Brain Res. 2002;139:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Borodinsky LN, Root CM, Cronin JA, Sann SB, Gu X, Spitzer NC. Activity-dependent homeostatic specification of transmitter expression in embryonic neurons. Nature. 2004;429:523–530. doi: 10.1038/nature02518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS. Signaling between intracellular Ca2+ stores and depletion-activated Ca2+ channels generates [Ca2+]i oscillations in T lymphocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1994;103:365–388. doi: 10.1085/jgp.103.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lewis RS. Calcium oscillations in T-cells: mechanisms and consequences for gene expression. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;5:925–929. doi: 10.1042/bst0310925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jairaman A, Yamashita M, Schleimer RP, Prakriya M. Store-operated Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels regulate PAR2-activated Ca2+ signaling and Cytokine production in airway Epithelial cells. J Immun. 2015;195:2122–2133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Capacitative calcium entry supports calcium oscillations in human embryonic kidney cells. J Physiol. 2005;562:697–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jones BF, Boyles RR, Hwang SY, Bird GS, Putney JW. Calcium influx mechanisms underlying calcium oscillations in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2008;48:1273–1281. doi: 10.1002/hep.22461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Demarque M, Represa A, Becq H, Khalilov I, Ben-Ari Y, Aniksztejn L. Paracrine intercellular communication by a Ca2+- and SNARE-independent release of GABA and glutamate prior to synapse formation. Neuron. 2002;36:1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manent JB, Demarque M, Jorquera I, Pellegrino C, Ben-Ari Y, Aniksztejn L, Represa A. A noncanonical release of GABA and glutamate modulates neuronal migration. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4755–4765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0553-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.LoTurco JJ, Owens DF, Heath MJS, Davis MBE, Kriegstein AR. GABA and glutamate depolarize cortical progenitor cells and inhibit DNA synthesis. Neuron. 1995;15:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Owens DF, Boyce LH, Davis MBE, Kriegstein AR. Excitatory GABA responses in embryonic and neonatal cortical slices demonstrated by gramicidin perforated-patch recordings and calcium imaging. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6414–6423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06414.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morgan PJ, Hubner R, Rolfs A, Frech MJ. Spontaneous calcium transients in human neural progenitor cells mediated by transient receptor potential channels. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:2477–2486. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Flint AC, Dammerman RS, Kriegstein AR. Endogenous activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors in neocortical development causes neuronal calcium oscillations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12144–12149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pathak MM, Nourse JL, Tran T, Hwe J, Arulmoli J, Le DTT, Bernardis E, Flanagan LA, Tombola F. Stretch-activated ion channel Piezo1 directs lineage choice in human neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16148–16153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409802111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dolmetsch RE, Xu K, Lewis RS. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature. 1998;392:933–936. doi: 10.1038/31960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dupont G, Combettes L, Bird GS, Putney JW. Calcium oscillations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parekh AB. Decoding cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS, Goodnow CC, Healy JI. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997;386:855–858. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weinstein DC, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Neural Induction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:411–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leclerc C, Neant I, Moreau M. The calcium: an early signal that initiates the formation of the nervous system during embryogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:3. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moreau M, Leclerc C, Gualandris-Parisot L, Duprat A-M. Increased internal Ca2+ mediates neural induction in the amphibian embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12639–12643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leclerc C, Webb SE, Daguzan C, Moreau m, Miller AL. Imaging patterns of calcium transients during neural induction in Xenopus laevis embryos. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3519–3529. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Drean G, Leclerc C, Duprat AM, Moreau M. Expression of L-type Ca2+ channel during early embryogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Int J Dev Biol. 1995;39:1027–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leclerc C, Neant I, Webb SE, Miller AL, Moreau M. Calcium transients and calcium signalling during early neurogenesis in the amphibian embryo Xenopus laevis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leclerc C, Duprat A-M, Moreau M. Noggin upregulates Fos expression by a calcium-mediated pathway in amphibian embryos. Dev Growth Differ. 1999;41:227–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1999.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brown JR, Nigh E, Lee RJ, Ye H, Thompson MA, Saudou F, Pestell RG, Greenberg ME. Fos family members induce cell cycle entry by activating cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5609–5619. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sheng M, Greenberg ME. The regulation and function of c-fos and other immediate early genes in the nervous system. Neuron. 1990;4:477–485. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90106-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leclerc C, Lee M, Webb SE, Moreau M, Miller AL. Calcium transients triggered by planar signals induce the expression of ZIC3 gene during neural induction in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2003;261:381–390. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Batut J, Vandel L, Leclerc C, Daguzan C, Moreau M, Neant I. The Ca2+-induced methyltransferase xPRMT1b controls neural fate in amphibian embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15128–15133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502483102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lin HH, Bell E, Uwanogho D, Perfect LW, Noristani H, Bates TJ, Snetkov V, Price J, Sun YM. Neuronatin promotes neural lineage in ESCs via Ca(2+) signaling. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1950–1960. doi: 10.1002/stem.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yanagida E, Shoji S, Hirayama Y, Yoshikawa F, Otsu K, Uematsu H, Hiraoka M, Furuichi T, Kawano S. Functional expression of Ca2+ signaling pathways in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Calcium. 2004;36:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang K, Xue T, Tsang SY, Van Huizen R, Wong CW, Lai KW, Ye Z, Cheng L, Au KW, Zhang J, Li GR, Lau CP, Tse HF, Li RA. Electrophysiological properties of pluripotent human and mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1526–1534. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Papanayotou C, De Almeida I, Liao P, Oliveira NM, Lu SQ, Kougioumtzidou E, Zhu L, Shaw A, Sheng G, Streit A, Yu D, Wah Soong T, Stern CD. Calfacilitin is a calcium channel modulator essential for initiation of neural plate development. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1837. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Parekh AB, Muallem S. Ca(2+) signalling and gene regulation. Cell Calcium. 2011;49:279. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carrion AM, Link WA, Ledo F, Mellstrom B, Naranjo JR. DREAM is a Ca2+-regulated transcriptional repressor. Nature. 1999;398:80–84. doi: 10.1038/18044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Naranjo JR, Mellstrom B. Ca2+-dependent transcriptional control of Ca2+ homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:31674–31680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.384982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2205–2232. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Graef IA, Chen F, Crabtree GR. NFAT signaling in vertebrate development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;5:505–512. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Groth RD, Coicou LG, Mermelstein PG, Seybold VS. Neurotrophin activation of NFAT-dependent transcription contributes to the regulation of pro-nociceptive genes. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1162–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Groth RD, Mermelstein PG. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells)-dependent transcription: a role for the transcription factor NFATc4 in neurotrophin-mediated gene expression. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8125–8134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-08125.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Groth RD, Weick JP, Bradley KC, Luoma JI, Aravamudan B, Klug JR, Thomas MJ, Mermelstein PG. D1 dopamine receptor activation of NFAT-mediated striatal gene expression. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:31–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nguyen T, Di Giovanni S. NFAT signaling in neural development and axon growth. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008;26:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Graef IA, Wang F, Charron F, Chen L, Neilson J, Tessier-Lavigne M, Crabtree GR. Neurotrophin and netrins require calcineurin/NFAT signaling to stimulate outgrowth of embryonic axons. Cell. 2003;113:657–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Freeman A, Franciscovich A, Bowers M, Sandstrom DJ, Sanyal S. NFAT regulates pre-synaptic development and activity-dependent plasticity in Drosophila. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46:535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ding B, Wang W, Selvakumar T, Xi HS, Zhu H, Chow CW, Horton JD, Gronostajski RM, Kilpatrick DL. Temporal regulation of nuclear factor one occupancy by calcineurin/NFAT governs a voltage-sensitive developmental switch in late maturing neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:2860–2872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3533-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Benedito AB, Lehtinen M, Massol R, Lopes UG, Kirchhausen T, Rao A, Bonni A. The transcription factor NFAT3 mediates neuronal survival. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2818–2825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vashishta A, Habas A, Pruunsild P, Zheng JJ, Timmusk T, Hetman M. Nuclear factor of activated T-cells isoform c4 (NFATc4/NFAT3) as a mediator of antiapoptotic transcription in NMDA receptor-stimulated cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15331–15340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4873-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Graef IA, Mermelstein PG, Stankunas K, Neilson JR, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Crabtree GR. L-type calcium channels and GSK-3 regulate the activity of NF-ATc4 in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1999;401:703–708. doi: 10.1038/44378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oliveria SF, Dell’Acqua ML, Sather WA. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron. 2007;55:261–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kar P, Samanta K, Kramer H, Morris O, Bakowski D, Parekh AB. Dynamic assembly of a membrane signaling complex enables selective activation of NFAT by Orai1. Curr Biol. 2014;24:1361–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.West AE, Chen WG, Dalva MB, Dolmetsch RE, Kornhauser JM, Shaywitz AJ, Takasu MA, Tao X, Greenberg ME. Calcium regulation of neuronal gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11024–11031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lonze BE, Ginty DD. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35:605–635. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kornhauser JM, Cowan CW, Saywitz AJ, Dolmetsch RE, Griffith EC, Hu LS, Haddad C, Xia Z, Greenberg ME. CREB transcriptional activity in neurons is regulated by multiple, calcium-specific phosphorylation events. Neuron. 2002;34:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Redmond L, Kashani AH, Ghosh A. Calcium regulation of dendritic growth via CaM Kinase IV and CREB-mediated transcription. Neuron. 2002;34:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lepski G, Jannes CE, Nikkhah G, Bischofberger J. cAMP promotes the differentiation of neural progenitor cells in vitro via modulation of voltage-gated calcium channels. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:155. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Merz K, Herold S, Lie DC. CREB in adult neurogenesis–master and partner in the development of adult-born neurons? Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1078–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Herold S, Jagasia R, Merz K, Wassmer K, Lie DC. CREB signalling regulates early survival, neuronal gene expression and morphological development in adult subventricular zone neurogenesis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gaudilliere B, Konishi Y, Iglesia Ndl, Yao G-I, Bonni A. A CaMKII-neuroD signaling pathway specifies dendritic morphogenesis. Neuron. 2004;41:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Deisseroth K, Singla S, Toda H, Monje M, Palmer TD, Malenka RC. Excitation-neurogenesis coupling in adult neural stem/progenitor cells. Neuron. 2004;42:535–552. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Santella L. The role of calcium in the cell cycle: facts and hypotheses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:317–324. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Santella L, Kyozuka K, De Riso L, Carafoli E. Calcium, protease action and the regulation of the cell cycle. Cell Calcium. 1998;23:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Berridge MJ. Calcium signalling, cell proliferation BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular. Cell Dev Biol. 1995;17:491–500. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fiorio Pla A, Maric D, Brazer SC, Giacobini P, Liu X, Chang YH, Ambudkar IS, Barker JL. Canonical transient receptor potential 1 plays a role in basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)/FGF receptor-1-induced Ca2+ entry and embryonic rat neural stem cell proliferation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2687–2701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0951-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Raballo R, Rhee J, Lyn-Cook R, Leckman JF, Schwartz ML, Vaccarino FM. Basic fibroblast growth factor (Fgf2) is necessary for cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5012–5023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-05012.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]