Abstract

Chronic infection with Friend retrovirus is associated with suppressed antitumor immune responses. In the present study we investigated whether modulation of T-cell responses during acute infection would restore antitumor immunity in persistently infected mice. T-cell modulation was done by treatments with DTA-1 anti- glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor monoclonal antibodies. The DTA-1 monoclonal antibody is nondepleting and delivers costimulatory signals that both enhance the activation of effector T cells and inhibit suppression by regulatory T cells. DTA-1 therapy produced faster Th1 immune responses, significant reductions in both acute virus loads and pathology and, most importantly, long-term improvement of CD8+ T-cell-mediated antitumor responses.

A growing body of evidence indicates that CD4+ regulatory T cells not only play a critical role in preventing autoimmune diseases, but also help prevent immunopathology during immune responses against infectious agents (2, 3, 16, 35, 37, 40). However, the constitutive immunosuppressive activity by regulatory T cells necessary to prevent autoreactivity might also inhibit initial responses to infections until inflammatory signals become sufficient to override inhibitory signals (46). The resulting delay in reacting to a quickly replicating infectious agent could exacerbate pathology and might also aid in the establishment of persistent infections. For example, the establishment of chronic hepatitis C virus infections is strongly associated with the presence of virus-specific regulatory T cells (25) and weak or absent Th1 responses (8, 12, 22, 30, 32).

In the Friend virus (FV) model of retrovirus infection (15, 19), our investigators previously found that virus persistence was associated with an immunosuppressive population of CD4+ T cells (17). Those studies were done with a strain of mice that is somewhat analogous to people infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the respect that the mice are able to reduce infection and recover from acute disease but develop long-term persistent infections. The persistently infected mice have weakened mixed lymphocyte responses compared to naïve mice and, interestingly, fail to reject transplants of FBL-3 tumors. FBL-3 is an FV-induced tumor which is rapidly rejected by naïve mice (17). The failure to reject FBL-3 tumors was unexpected, because the tumor expresses immunogenic FV antigens and can be used to immunize mice against infection with FV. Thus, it was expected that the FV-exposed mice would have stronger rather than weaker anti-FBL-3 responses. Normal naïve mice reject FBL-3 through a CD8+ T-cell-mediated mechanism (50), but they become unable to reject the tumors after receiving an adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells from persistently infected mice (17). CD4+ T cells from persistently infected mice also suppress cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in mixed lymphocyte cultures, indicating a generalized nonspecific immunosuppression (17). These results are consistent with those for CD4+ regulatory T cells, which can also suppress in a nonspecific manner once they become activated (47).

In the present studies we sought to determine if virus spread, pathology, and immunosuppression could be prevented by modulating the T-cell response during the acute phase of FV infection. Several groups have reported that CD4+ regulatory T cells can be depleted by in vivo administration of antibodies to CD25. However, since CD25, the alpha-chain of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor, is also up-regulated on activated effector T cells, in vivo administration of anti-CD25 antibody during acute FV infection could deplete activated effector T cells as well as regulatory T cells. CD4+ regulatory T cells also constitutively express the glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor family-related gene (GITR) at high levels (27), and it has been shown that a monoclonal antibody (DTA-1) against GITR delivers an agonistic signal that eliminates suppression by regulatory T cells without causing depletion in vivo (43). Furthermore, anti-GITR delivers costimulatory signals to antigen-activated effector cells, thereby enhancing specific effector responses directly as well as indirectly (20, 21, 33, 34, 49). Thus, in vivo DTA-1 antibody administration could potentially attenuate suppression while simultaneously intensifying the anti-FV effector T-cell response. Indeed, we found that administration of anti-GITR during the first 10 days of FV infection increased Th1 cytokine production by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, significantly reduced acute infection levels, prevented FV-induced splenomegaly, and restored long-term antitumor immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Experiments were done using (C57BL/10 × A.BY) F1 mice bred at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories. The relevant FV resistance genotype of these mice is H-2b/b Fv1b/b Fv2r/s Rfv3r/s. All mice were females of 12 to 24 weeks of age at the beginning of the experiments and were treated in accordance with the regulations and guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Rocky Mountain Laboratories and the National Institutes of Health.

Virus and virus infection.

The FV stock used in these experiments was uncloned FV complex containing B-tropic Friend murine leukemia helper virus and polycythemia-inducing spleen focus-forming virus (24). The complex was prepared as a 10% spleen cell homogenate from BALB/c mice infected 14 days previously with 3,000 spleen focus-forming units of uncloned virus stock. For virus challenge experiments, mice were injected intravenously with 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered balanced salt solution containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 1,500 spleen focus-forming units of FV complex. Chronically infected mice were mice that had been infected at least 8 weeks previously and had recovered from FV-induced splenomegaly. Virus levels are usually stable at approximately 104 infectious centers per spleen by 6 to 8 weeks postinfection.

Treatment of mice with antibodies.

The rat-derived anti-GITR-producing hybridoma (DTA-1) (43) was grown in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Supernatant was harvested, spun at 500 × g for 10 min to remove cells and debris, and frozen at −20°C. Supernatants were pooled, quantified, and stored at −20°C. For in vivo treatments, 0.5 ml of the supernatant containing 70 μg of antibody was injected intraperitoneally every other day from the day of infection until day 10 postinfection. Control mice were treated with an equal amount of rat immunoglobulin (Ig).

Palpation for splenomegaly.

FV disease progression was followed by spleen palpation of anesthetized mice, a standard procedure used to follow progression of FV infection as previously described (14). Palpations were done in a blinded manner, and splenomegaly was rated on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 being normal, 2 being moderately splenomegalic (three to five times enlarged), and 3 and 4 being severely splenomegalic (large enough to protrude to or past the ventral midline and weighing 10 to 20 times a normal spleen).

Tumor inoculation and measurement of tumor size.

Mice were injected intradermally on the dorsal region with 107 FBL-3 cells in 0.1 ml of RPMI 1640. FBL-3 is an FV-induced tumor line derived from a C57BL/6 (B6) mouse, and the subline used in these experiments expresses FV antigens but does not produce infectious virus. Following tumor transplantation, the tumor diameters were measured in two directions using a pressure-sensitive micrometer, and means from the two measurements were plotted.

Infectious center assays.

Titrated numbers of spleen cells from infected mice were plated onto susceptible Mus dunni cells, cocultivated for 5 days, fixed with ethanol, stained with Friend murine leukemia helper virus envelope-specific MAb720, and developed with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and substrate to detect foci of infected cells (9).

Intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry.

Cell surface and intracellular cytokine staining were performed using Becton Dickinson/PharMingen reagents (except where noted) and the Cytofix/Cytoperm intracellular cytokine staining kit. T-cell antibodies were fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti-CD43 (1B11), phycoerythrin (PE)-anti-CD25 (PC61), PE-anti-CD44 (IM7), allophycocyanin (APC)-anti-CD4(RM4-5), and APC-anti-CD8(53-6.7). Dead cells (propidium iodidehigh) were excluded from all cell surface analyses. For intracellular cytokine staining, erythrocyte-depleted spleen cells were incubated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 (23) for 5 h at 37°C in the presence of monensin (2 μg/ml). Anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 were used to obtain a broad perspective of the full range of T-cell activity in the infected mice (44). Cells were washed twice, incubated with anti-Fcγ 2/3 receptor (2.4G2) to block Fc receptors, and stained with APC-labeled anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-CD43 in round-bottom 96-well plates. The cells were then washed, permeabilized, and reacted with PE-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for IL-2 (CalTag, Burlingame, Calif.), IL-4, IL-10, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Data were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) from 100,000 CD4- or CD8-gated events acquired per sample and were analyzed using BD Cellquest Pro software (version 4.0.1; Becton Dickinson). Surface markers were analyzed on cells directly ex vivo. Tetramers were obtained from Beckman Coulter (San Diego, Calif.).

RESULTS

Reduced disease and virus load in anti-GITR-treated mice.

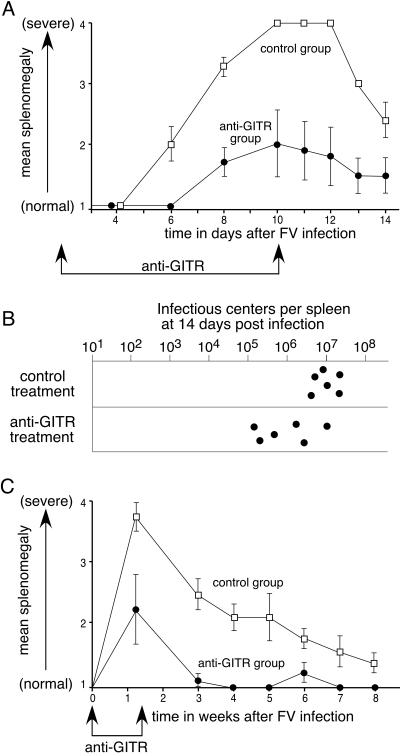

The effect of in vivo anti-GITR treatment on acute FV-induced disease was investigated by treating mice with anti-GITR antibody every other day from the day of infection until 10 days postinfection. The predominant gross pathology associated with acute FV infection is splenomegaly, which was gauged every day following infection. At 6 days postinfection, five of the six control mice already had moderate FV-induced splenomegaly, while all treated mice were still normal (Fig. 1A). By 10 days postinfection all control-treated mice had severely enlarged spleens that protruded across their ventral midlines. In contrast, none of the six treated mice developed severe splenomegaly during the first 2 weeks of infection. Mice were sacrificed at 14 days postinfection to measure levels of virus-producing spleen cells (infectious centers). The average spleen weight at 2 weeks was significantly lower in the treatment group than in the control group (data not shown), and the anti-GITR group had an average of eightfold fewer infectious centers (Fig. 1B). The reduction in infectious centers was as much as 100-fold in two of the mice. Thus, the effects of anti-GITR were a slower onset and reduced severity of clinical signs and a significant decrease in acute infection levels at 2 weeks postinfection. A study extended for 8 weeks showed significantly less severe splenomegaly and faster recovery than in control mice over the first 6 weeks of palpations (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Effects of anti-GITR therapy on acute FV infection. (A) Mean severity of splenomegaly data for the rat Ig control group (squares) and the anti-GITR group (circles) are plotted over time in days. The beginning and end of anti-GITR therapy are indicated by arrows. Each dot represents the mean on a scale from 1 (normal) to 4 (severely splenomegalic) (14). Mann-Whitney tests showed the differences to be significant between 6 and 14 days (P < 0.05; n = 6 mice/group). (B) Infectious center assays at 2 weeks postinfection showed significantly fewer virus-producing cells in the spleens of mice treated with anti-GITR than in control mice (P = 0.026 by Mann-Whitney test using log10 values). (C) Splenomegaly was plotted over time in weeks, with the beginning and end of anti-GITR therapy indicated by arrows. Error bars indicate standard deviations and the differences between the groups were significant for all time points from 1 to 6 weeks postinfection (P < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney test; n = 6 mice/group).

Anti-GITR effects on cell surface activation markers and cytokines.

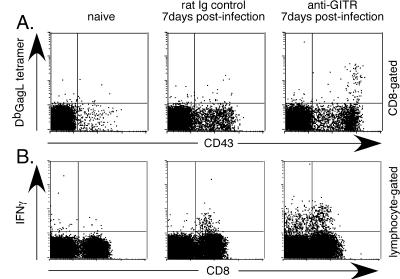

The difference in splenomegaly between the groups evident at 8 days postinfection suggested that the treated group might have developed earlier immune responses. CD8+ T cells were examined to determine if faster virus control and reduced pathology in the anti-GITR group correlated with differences in cell surface activation markers and/or cytokine production. IFN-γ was of special interest, because it has previously been associated with recovery from FV infection (31). At 1 week postinfection the level of activated CD8+ T cells (CD43+) increased in both groups due to FV infection (Fig. 2A). However, the response was significantly higher in the anti-GITR group than in the control group. There was also a significantly greater expansion of CD8+ T cells specific for the FV gagL epitope (5, 39), as measured by tetramer staining (Fig. 2A). In addition, the anti-GITR group also had significantly more CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ (Fig. 2B). Thus, anti-GITR therapy produced a faster expansion of activated CD8+ T cells, including those producing IFN-γ.

FIG. 2.

Surface markers and cytokine production by CD8+ T cells at 1 week postinfection. CD8-gated T cells were analyzed for CD43 and Db GagL tetramer (39) expression at 1 week postinfection. The mean percentage of CD43-positive cells was 13.5% for the infected/rat Ig control group and 18.6% for the anti-GITR group (P = 0.0022 by Mann-Whitney test; n = 6 mice/group). Tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells averaged 0.2% in the infected/rat Ig control mice and 0.6% in anti-GITR mice (P = 0.0152; n = 6 mice/group). The mean percentage of CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ was significantly greater in the anti-GITR group (2.2%) than in the infected/rat Ig control group (1.2%; P = 0.0022; n = 6 mice/group).

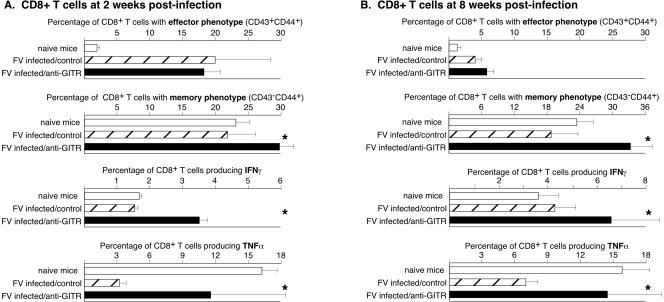

By 2 weeks postinfection, the percentage of CD8+ T cells with the cell surface phenotype of effector cells was approximately equal in the control and anti-GITR groups, but a higher percentage from the anti-GITR group had differentiated into memory cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, the anti-GITR group still had higher percentages of IFN-γ-producing cells. The in vitro activation required for intracellular cytokine staining consistently gave a moderate background of TNF-α-producing cells from naïve mice (Fig. 3A). TNF-α production by naive cells following in vitro stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for intracellular cytokine staining is not uncommon (M. Slifka, personal communication). Interestingly, TNF-α-producing CD8+ T cells were significantly diminished in FV-infected mice, indicating immunosuppression relative to naïve mice (Fig. 3A). Anti-GITR therapy significantly reversed this suppression.

FIG. 3.

Surface markers and cytokine production by CD8+ T cells at 2 and 8 weeks postinfection. Stars indicate statistically different values (P < 0.05) between the control-treated and anti-GITR-treated groups as determined by Mann-Whitney tests. n = 6 for both the control-treated groups and the anti-GITR groups at both 2 weeks postinfection (A) and 8 weeks postinfection (B). Error bars indicate standard deviations.

To determine if the short-term anti-GITR therapy during acute infection had any sustained effects on CD8+ T cells, the analyses were repeated on spleen cells taken at 8 weeks postinfection. The percentages of effector cells in the control and test groups had decreased to slightly above normal levels and were not significantly different. Interestingly, only the anti-GITR group had an expanded population of CD8+ T cells with a memory phenotype (Fig. 3B). Also, the anti-GITR group still had significantly more IFN-γ- and TNF-α-producing CD8+ T cells than the control group at this late time point (Fig. 3B).

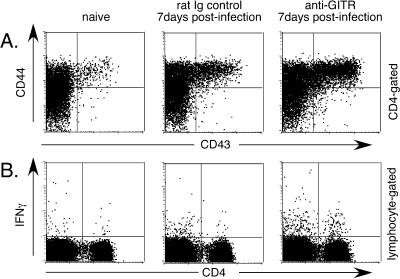

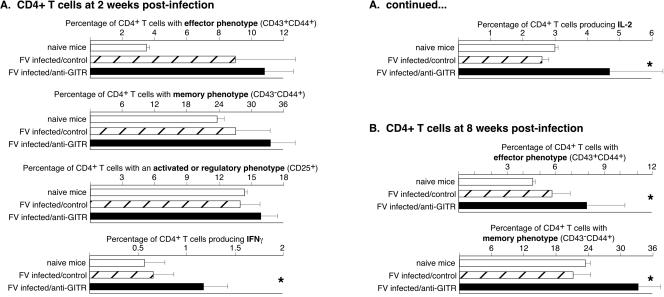

CD4+ T cells were analyzed in a similar manner. At 1 week postinfection the mean percentage of activated CD4+ T cells in the anti-GITR group was almost double that in the control group, and there were five times as many CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ (Fig. 4). By 2 weeks postinfection the percentages of CD4+ T cells producing the Th1 cytokines IL-2 and IFN-γ were significantly higher in the anti-GITR group than in the control group (Fig. 5A). No IL-4- or IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells were detected in either group at either 1 or 2 weeks postinfection (data not shown). As previously shown (43), in vivo administration of anti-GITR was nondepleting and did not significantly alter the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CD25. By 8 weeks postinfection there were only slightly higher levels of CD4+ T cells with an effector phenotype in the anti-GITR group, but the level of memory cells averaged over 10% higher (Fig. 5B). No significant differences in cytokine production between the groups were observed at the 8-week time point (data not shown). Results indicated that anti-GITR treatment significantly affected the differentiation of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells into memory cells following FV infection.

FIG. 4.

Surface markers and cytokine production by CD4+ T cells at 1 week postinfection. (A) CD4-gated T cells were analyzed for CD43 and CD44 expression at 1 week postinfection. The mean percentage of CD43/44 double-positive cells was 2.6% in the naïve group, 9.6% in the rat Ig control group, and 16.7% in the anti-GITR group (P = 0.0022 by Mann-Whitney test; n = 6 mice/group). (B) Lymphocyte-gated spleen cells were analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining for cytokine production by CD4+ T cells. The mean percentage of CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ was significantly greater in the anti-GITR group (1.0%) than in the rat Ig control group (0.2%; P = 0.0022; n = 6 mice/group). None of the groups made detectable levels of IL-4 or IL-10 (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Surface markers and cytokine production by CD4+ T cells at 2 and 8 weeks postinfection. Stars indicate statistically different values (P < 0.05) between the control-treated and anti-GITR-treated groups as determined by Mann-Whitney tests. n = 6 for both the control-treated groups and the anti-GITR groups at both 2 weeks postinfection (A) and 8 weeks postinfection (B). Error bars indicate standard deviations from the mean.

Restoration of antitumor responses following anti-GITR therapy.

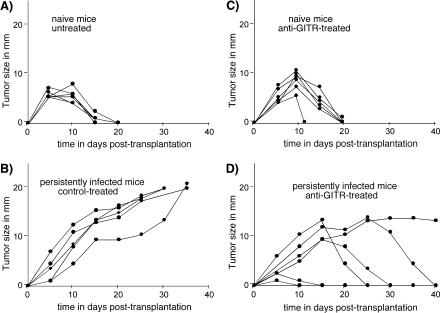

A critical aspect of this study was to determine if anti-GITR therapy could prevent or ameliorate the suppression of antitumor responses that our group had previously observed in chronically infected mice. A group of mice was treated during the first 10 days of infection and then tested for their ability to reject transplants of FBL-3 tumors at 8 weeks postinfection. As shown previously, naïve mice rejected FBL-3 tumor transplants quite rapidly (Fig. 6A), whereas the tumors grew out of control in mice persistently infected with FV (Fig. 6B). Anti-GITR therapy did not significantly change rejection times in uninfected mice (Fig. 6C), but there was a significant improvement in the infected mice (Fig. 6D). Five of the six mice completely rejected their tumors, and the remaining mouse was able to stabilize tumor size at approximately 14 mm in diameter. Rejection times in the treated mice were quite variable. Two of the mice in the anti-GITR group appeared to have anamnestic responses, as evidenced by little tumor growth and fast rejection times. Three of the four remaining mice were able to reject their tumors completely, while the other maintained a constant tumor size. Thus, the overall effect of the anti-GITR treatment was restoration of the antitumor responses, which were suppressed in the control group. Interestingly, anti-GITR treatment at the time of FBL-3 tumor transplantation did not improve the antitumor responses of persistently infected mice (data not shown). These results indicated that therapy must be initiated early in the course of infection.

FIG. 6.

Improved antitumor responses following anti-GITR therapy. Tumor growth is plotted over time in the various groups. Each line represents tumor growth in a single mouse. The mice were transplanted with 107 FBL-3 tumor cells by intradermal injection at 8 weeks postinfection with FV. In accordance with animal care and use rules at Rocky Mountain Labs to prevent pain and suffering, all animals were euthanized if their tumors grew to a mean diameter greater than 20 mm.

DISCUSSION

A central aspect of the immune system is its ability to mount reactions against foreign invaders while maintaining tolerance to self. In an uninfected individual, the T-cell repertoire is in a nonreactive status, prevented from engaging in autoimmune reactions by peripheral tolerance mechanisms, including the suppressive activity of CD4+ regulatory T cells. However, upon viral infection the speed and efficiency with which the immune response is able to initiate a response often dictates the course and severity of subsequent disease. Because suppression by CD4+ regulatory T cells involves both cell-to cell interactions and secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines, it has both specific and nonspecific features (47, 48). Therefore, it is possible that early during an infection a delay in antiviral immune responses may occur during the shift from T regulatory cell-induced quiescence to activation. If so, then the attenuation of regulatory T-cell function during the early phase of viral infection should lead to faster and stronger immune responses. This is precisely what we observed in FV-infected mice treated with anti-GITR. A similar enhancement of antiviral immunity was recently shown when mice were depleted of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells prior to infection with herpes simplex virus (46).

Treatment with anti-GITR during the first 10 days of FV infection resulted not only in significantly reduced acute infection and pathology, but also in a long-lasting reduction in FV-induced suppression of antitumor responses. The finding of an anamnestic response in two of the transplant mice (Fig. 6) was consistent with the finding of increased numbers of T cells with a memory phenotype in the anti-GITR group (Fig. 3 and 5). The variability in the tumor rejection times suggested that it might be possible to improve the anti-GITR dosage or treatment schedule to induce a more consistent effect. Alternatively, GITR-negative regulatory T cells may also be suppressing CD8+ T-cell responses (18), or anti-GITR may have only a partial effect. It was recently shown that agonistic signals through the 4-1BB molecule were more potent than anti-GITR signaling in preactivated regulatory T cells (7). Thus, anti-4-1BB antibody might produce a stronger effect than anti-GITR antibody.

Our finding that early anti-GITR treatment produced a significant effect on antitumor responses 50 days after cessation of therapy indicated that the treatment produced a relatively stable alteration in the immunological status of the mice. A stable alteration was also indicated by sustained Th1 responses in the anti-GITR group, as evidenced by increased percentages of IFN-γ- and TNF-α-producing CD8+ T cells at 8 weeks postinfection (Fig. 3B).

It was recently shown that chronic infections of mice with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus resulted in a gradual impairment of the function of virus-specific CD8+ T cells (52). Impairment of CD8+ T-cell function due to chronic stimulation could partially account for the inability of mice persistently infected with FV to reject FBL-3 tumors, since FBL-3 rejection is mediated by CD8+ T cells (50) specific for an FV gag antigen (5, 28). However, the CD8+ T cells in the anti-GITR-treated mice were also subjected to chronic stimulation, yet those mice were able to reject FBL-3 tumors. Furthermore, the immunosuppression in mice persistently infected with FV is not limited to FV-induced tumors but has also been observed as a suppressed response in which no chronic stimulation could have occurred, e.g., suppressed mixed lymphocyte reactions and suppressed rejection of tumors not of FV origin (17). Finally, our group previously showed that the suppression of FBL-3 tumor responses could be passed from persistently infected mice to naïve mice by adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells, but not of CD8+ T cells (17). Taken as a whole, the data indicate that the impairment of CD8+ T cells in mice persistently infected with FV is not solely due to chronic stimulation, but it is strongly influenced by a subset of CD4+ T cells with immunosuppressive activity and that activity could be reversed by GITR ligation. The long-term inhibition of immunosuppression following only 10 days of anti-GITR therapy during acute infection indicates that the activity of these cells during the early phase of infection is of critical importance in establishing the immunosuppressive state. This conclusion is supported by the finding that anti-GITR therapy did not improve responsiveness when given at the time of tumor transplantation but had to be given early. These results suggest that anti-GITR prevented induction of regulatory T cells but did not reverse suppression in already-induced cells.

We did not observe increases in CD4+/CD25+ T cells after FV infection, as has been observed in Leishmania infections associated with suppression by regulatory T cells (3). It has been proposed that in addition to the “natural” CD4+/CD25+ regulatory T cells that normally control autoimmune responses through a cell-to-cell contact mechanism (37, 41), there are also “adaptive” regulatory T cells that develop as a consequence of suboptimal stimulation or costimulation during an infection (4, 26, 45). To date, there is no pattern of cell surface markers that unambiguously distinguishes regulatory T cells from other T cells, and subsets of regulatory T cells, such as Th3 cells that secrete transforming growth factor β (6) and Tr1 cells that secrete IL-10 (13), have been described, as well as CD4+/CD25− regulatory T cells (26, 51). Thus, regulatory T cells represent a complex subset of cells that still requires further definition. Our investigators recently found that immunosuppressive CD4+ T cells that arise in response to FV infection and inhibit CD8+ T-cell function are contained in both the CD25-positive and -negative subsets (10).

The present results suggest the possibility of using anti-GITR therapy in modulating regulatory T cells and controlling immunosuppression. For example, human immunodeficiency virus-infected and human T-cell leukemia type 1-infected patients are at high risk of developing malignancies because of their immunosuppressed state (38), and there is evidence that an aspect of the immunosuppression in these patients may be due to regulatory T cells (1, 11, 29). Anti-GITR modulation of suppressor cells might be a safer approach than more radical therapies, such as general depletion of regulatory T cells by anti-CD25 antibodies, because of less chance of inducing autoimmune disease. However, adult mice with a C57BL genetic background such as those used in our studies are relatively resistant to the development of autoimmune disease (36, 42), and anti-GITR has the potential to induce autoimmune disease in more susceptible mouse strains (21, 43). Thus, our experiments demonstrate the potential benefits of modulation by anti-GITR, but further improvement must be made to more specifically down-regulate suppression of antiviral responses while maintaining suppression of autoimmune responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aandahl, E. M., J. Michaelsson, W. J. Moretto, F. M. Hecht, and D. F. Nixon. 2004. Human CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells control T-cell responses to human immunodeficiency virus and cytomegalovirus antigens. J. Virol. 78:2454-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aseffa, A., A. Gumy, P. Launois, H. R. MacDonald, J. A. Louis, and F. Tacchini-Cottier. 2002. The early IL-4 response to Leishmania major and the resulting Th2 cell maturation steering progressive disease in BALB/c mice are subject to the control of regulatory CD4+ CD25+ T cells. J. Immunol. 169:3232-3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belkaid, Y., C. A. Piccirillo, S. Mendez, E. M. Shevach, and D. L. Sacks. 2002. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature 420:502-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bluestone, J. A., and A. K. Abbas. 2003. Natural versus adaptive regulatory T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:253-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, W., H. Qin, B. Chesebro, and M. A. Cheever. 1996. Identification of a gag-encoded cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope from FBL-3 leukemia virus shared by Friend, Moloney, and Rauscher murine leukemia virus-induced tumors. J. Virol. 70:7773-7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, Y., V. K. Kuchroo, J. Inobe, D. A. Hafler, and H. L. Weiner. 1994. Regulatory T cell clones induced by oral tolerance: suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science 265:1237-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi, B. K., J. S. Bae, E. M. Choi, W. J. Kang, S. Sakaguchi, D. S. Vinay, and B. S. Kwon. 2004. 4-1BB-dependent inhibition of immunosuppression by activated CD4+ CD25+ T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75:785-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramp, M. E., P. Carucci, S. Rossol, S. Chokshi, G. Maertens, R. Williams, and N. V. Naoumov. 1999. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) specific immune responses in anti-HCV positive patients without hepatitis C viraemia. Gut 44:424-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dittmer, U., D. M. Brooks, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 1998. Characterization of a live-attenuated retroviral vaccine demonstrates protection via immune mechanisms. J. Virol. 72:6554-6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dittmer, U., H. He, R. J. Messer, S. Schimmer, A. R. M. Olbrich, C. Ohlen, P. D. Greenberg, I. M. Stromnes, M. Iwashiro, S. Sakaguchi, L. H. Evans, K. E. Peterson, G. Yang, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2004. Functional impairment of CD8+ T cells by regulatory T cells during persistent retroviral infection. Immunity 20:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garba, M. L., C. D. Pilcher, A. L. Bingham, J. Eron, and J. A. Frelinger. 2002. HIV antigens can induce TGF-β1-producing immunoregulatory CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 168:2247-2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerlach, J. T., H. M. Diepolder, M. C. Jung, N. H. Gruener, W. W. Schraut, R. Zachoval, R. Hoffmann, C. A. Schirren, T. Santantonio, and G. R. Pape. 1999. Recurrence of hepatitis C virus after loss of virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response in acute hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 117:933-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groux, H., A. O'Garra, M. Bigler, M. Rouleau, S. Antonenko, J. E. de Vries, and M. G. Roncarolo. 1997. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature 389:737-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasenkrug, K. J., D. M. Brooks, M. N. Robertson, R. V. Srinivas, and B. Chesebro. 1998. Immunoprotective determinants in Friend murine leukemia virus envelop protein. Virology 248:66-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasenkrug, K. J., and B. Chesebro. 1997. Immunity to retroviral infection: the Friend virus model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7811-7816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hori, S., T. L. Carvalho, and J. Demengeot. 2002. CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells suppress CD4+ T cell-mediated pulmonary hyperinflammation driven by Pneumocystis carinii in immunodeficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:1282-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwashiro, M., R. J. Messer, K. E. Peterson, I. M. Stromnes, T. Sugie, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2001. Immunosuppression by CD4+ regulatory T cells induced by chronic retroviral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9226-9230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonuleit, H., and E. Schmitt. 2003. The regulatory T cell family: distinct subsets and their interrelations J. Immunol. 171:6323-6327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabat, D. 1989. Molecular biology of Friend viral erythroleukemia. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 148:1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanamaru, F., P. Youngnak, M. Hashiguchi, T. Nishioka, T. Takahashi, S. Sakaguchi, I. Ishikawa, and M. Azuma. 2004. Costimulation via glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor in both conventional and CD25+ regulatory CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 172:7306-7314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohm, A. P., J. S. Williams, and S. D. Miller. 2004. Cutting edge: ligation of the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor enhances autoreactive CD4+ T cell activation and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 172:4686-4690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamonaca, V., G. Missale, S. Urbani, M. Pilli, C. Boni, C. Mori, A. Sette, M. Massari, S. Southwood, R. Bertoni, A. Valli, F. Fiaccadori, and C. Ferrari. 1999. Conserved hepatitis C virus sequences are highly immunogenic for CD4+ T cells: implications for vaccine development. Hepatology 30:1088-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levings, M. K., R. Sangregorio, F. Galbiati, S. Squadrone, R. de Waal Malefyt, and M. G. Roncarolo. 2001. IFN-alpha and IL-10 induce the differentiation of human type 1 T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 166:5530-5539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lilly, F., and R. A. Steeves. 1973. B-tropic Friend virus: a host-range pseudotype of spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV). Virology 55:363-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald, A. J., M. Duffy, M. T. Brady, S. McKiernan, W. Hall, J. Hegarty, M. Curry, and K. H. Mills. 2002. CD4 T helper type 1 and regulatory T cells induced against the same epitopes on the core protein in hepatitis C virus-infected persons. J. Infect. Dis. 185:720-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuirk, P., and K. H. Mills. 2002. Pathogen-specific regulatory T cells provoke a shift in the Th1/Th2 paradigm in immunity to infectious diseases. Trends Immunol. 23:450-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McHugh, R. S., M. J. Whitters, C. A. Piccirillo, D. A. Young, E. M. Shevach, M. Collins, and M. C. Byrne. 2002. CD4+ CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells: gene expression analysis reveals a functional role for the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor. Immunity 16:311-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohlen, C., M. Kalos, L. E. Cheng, A. C. Shur, D. J. Hong, B. D. Carson, N. C. Kokot, C. G. Lerner, B. D. Sather, E. S. Huseby, and P. D. Greenberg. 2002. CD8+ T cell tolerance to a tumor-associated antigen is maintained at the level of expansion rather than effector function. J. Exp. Med. 195:1407-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostrowski, M. A., J. X. Gu, C. Kovacs, J. Freedman, M. A. Luscher, and K. S. MacDonald. 2001. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific CD4+ T cell immunity to gag in HIV-1-infected individuals with differential disease progression: reciprocal interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 responses. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1268-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pape, G. R., T. J. Gerlach, H. M. Diepolder, N. Gruner, M. Jung, and T. Santantonio. 1999. Role of the specific T-cell response for clearance and control of hepatitis C virus. J. Viral Hepat. 6(Suppl. 1):36-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson, K. E., M. Iwashiro, K. J. Hasenkrug, and B. Chesebro. 2000. Major histocompatibility complex class I gene controls the generation of gamma interferon-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells important for recovery from Friend retrovirus-induced leukemia. J. Virol. 74:5363-5367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehermann, B., and F. V. Chisari. 2000. Cell mediated immune response to the hepatitis C virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 242:299-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronchetti, S., G. Nocentini, C. Riccardi, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2002. Role of GITR in activation response of T lymphocytes. Blood 100:350-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronchetti, S., O. Zollo, S. Bruscoli, M. Agostini, R. Bianchini, G. Nocentini, E. Ayroldi, and C. Riccardi. 2004. GITR, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, is costimulatory to mouse T lymphocyte subpopulations. Eur. J. Immunol. 34:613-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakaguchi, S. 2003. Control of immune responses by naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells that express Toll-like receptors. J. Exp. Med. 197:397-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakaguchi, S. 2004. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:531-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakaguchi, S. 2003. Regulatory T cells: mediating compromises between host and parasite. Nat. Immunol. 4:10-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scadden, D. T. 2003. AIDS-related malignancies. Annu. Rev. Med. 54:285-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schepers, K., M. Toebes, G. Sotthewes, F. A. Vyth-Dreese, T. A. Dellemijn, C. J. Melief, F. Ossendorp, and T. N. Schumacher. 2002. Differential kinetics of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in the regression of retrovirus-induced sarcomas. J. Immunol. 169:3191-3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shevach, E. M. 2002. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:389-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shevach, E. M. 2000. Regulatory T cells in autoimmmunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:423-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu, J., S. Yamazaki, and S. Sakaguchi. 1999. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+ CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 163:5211-5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu, J., S. Yamazaki, T. Takahashi, Y. Ishida, and S. Sakaguchi. 2002. Stimulation of CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 3:135-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson, S. J., G. A. Hollander, E. Mizoguchi, D. Allen, A. K. Bhan, B. Wang, and C. Terhorst. 1997. Expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by TCR alpha beta+ and TCR gamma delta+ T cells in an experimental model of colitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinman, R. M., D. Hawiger, and M. C. Nussenzweig. 2003. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:685-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suvas, S., U. Kumaraguru, C. D. Pack, S. Lee, and B. T. Rouse. 2003. CD4+ CD25+ T cells regulate virus-specific primary and memory CD8+ T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 198:889-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi, T., Y. Kuniyasu, M. Toda, N. Sakaguchi, M. Itoh, M. Iwata, J. Shimizu, and S. Sakaguchi. 1998. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells: induction of autoimmune disease by breaking their anergic/suppressive state. Int. Immunol. 10:1969-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thornton, A. M., and E. M. Shevach. 2000. Suppressor effector function of CD4+ CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells is antigen nonspecific. J. Immunol. 164:183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tone, M., Y. Tone, E. Adams, S. F. Yates, M. R. Frewin, S. P. Cobbold, and H. Waldmann. 2003. Mouse glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor ligand is costimulatory for T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15059-15064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Udono, H., M. Mieno, H. Shiku, and E. Nakayama. 1989. The roles of CD8+ and CD4+ cells in tumor rejection. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 80:649-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uraushihara, K., T. Kanai, K. Ko, T. Totsuka, S. Makita, R. Iiyama, T. Nakamura, and M. Watanabe. 2003. Regulation of murine inflammatory bowel disease by CD25+ and CD25− CD4+ glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family-related gene+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 171:708-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wherry, E. J., J. N. Blattman, K. Murali-Krishna, R. van der Most, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J. Virol. 77:4911-4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]