Abstract

The recent failures of potential disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) may reflect the fact that the enrolled participants in clinical trials are already too advanced to derive a clinical benefit. Thus, well-validated biomarkers for the early detection and accurate diagnosis of the preclinical stages of AD will be crucial for therapeutic advancement. The combinatorial use of biomarkers derived from biological fluids, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), with advanced molecular imaging and neuropsychological testing may eventually achieve the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity necessary to identify people in the earliest stages of the disease when drug modification is most likely possible. In this regard, positive amyloid or tau tracer retention on positron emission tomography imaging, low CSF concentrations of the amyloid-β 1-42 peptide, high CSF concentrations in total tau and phospho-tau, mesial temporal lobe atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging, and temporoparietal/precuneus hypometabolism or hypoperfusion on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography have all emerged as biomarkers for the progression to AD. However, the ultimate AD biomarker panel will likely involve the inclusion of novel CSF and blood biomarkers more precisely associated with confirmed pathophysiologic mechanisms to improve its reliability for detecting preclinical AD. This review highlights advancements in biological fluid and imaging biomarkers that are moving the field towards achieving the goal of a preclinical detection of AD.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13311-016-0481-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Mild cognitive impairment, Biomarker, Cerebrospinal fluid, Positron emission tomography, Amyloid

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has an extensive preclinical stage, which is initiated 15 to 20 years prior to the emergence of clinical signs [1, 2]. Neuropathologic examination of older people who died with a clinical diagnosis of no cognitive impairment (NCI) or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) often reveal similar pathological signatures to those with frank AD [3–7], suggesting a heterogeneous asymptomatic phase of AD that varies in elderly individuals. These concepts have energized the field to develop a biomarker for identifying individuals in the earliest preclinical stages of AD, to facilitate early intervention and to delay or perhaps even prevent the onset of clinical symptoms. Moreover, biomarkers for AD progression may also have clinical utility for tracking the efficacy of potential disease-modifying therapies.

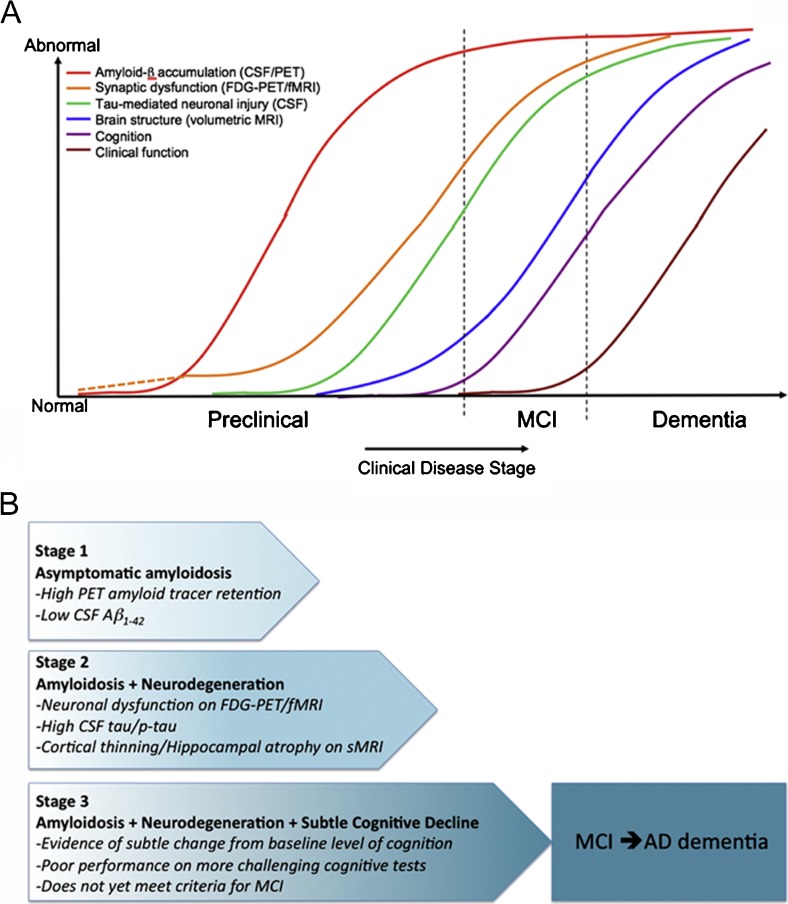

The National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) developed new working criteria for using a panel of prognostic fluid and imaging biomarkers to determine the likelihood of AD pathology and the staging of preclinical AD and the progression to prodromal and then clinical AD [1, 8], which included cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid-β (Aβ)42, amyloid positron emission tomography (PET), CSF total tau, threonine 181 (T181) phospho-tau, mesial temporal lobe (MTL) atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and tempoparietal/precuneus hypometabolism or hypoperfusion on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET (Fig. 1) [1, 9]. In general, findings to date have suggested that cerebral amyloidosis, as measured by increased amyloid PET signal and lower CSF levels of Aβ42, precedes markers of neurodegeneration and synaptic dysfunction (e.g., FDG-PET, MRI, and CSF tau) prior to the onset of subtle cognitive impairment related to AD. More specifically, loss of hippocampal volume on MRI and the ratio of CSF Aβ42 to total tau or phospho-tau are predictive of longitudinal changes in cognitive measures in the face of mounting AD pathology and its clinical sequelae [9–13]. In addition, arterial spin labeling MRI is used to examine the influence of changes in resting cerebral blood flow, as well as blood oxygenation level-dependent signal response in relation to PET-derived regional amyloid load [14, 15], or to memory encoding in the MTL [16]. Finally, new advances in tau PET imaging and novel fluid biomarkers hold promise to increase biomarker reliability. In fact, tau PET imaging studies suggest that tau accumulation may track better with cognitive decline compared with Aβ deposition in people with AD [17–19]. The combinatorial use of fluid and imaging biomarkers with neuropsychological testing may eventually achieve the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity necessary to identify people in the earliest stages of the disease when modification is most likely possible. In this regard, advancing biomarker research to clinical diagnostic settings will be critical for recruiting appropriate individuals who meet inclusion criteria for clinical trials. This article reviews the latest advancements in biological fluid and imaging biomarkers that are moving the field towards achieving this goal.

Fig. 1.

Current models for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression biomarkers. (A) A revised hypothetical model of biomarkers identifying preclinical AD [1], as originally proposed by Jack et al. [9]. In this model, amyloid β (Aβ) changes (red) as identified by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42 assay or positron emission tomography (PET) amyloid imaging precede markers for synaptic dysfunction (orange), as evidenced by fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). These alterations are closely associated with increased CSF tau (green), which serves as a surrogate for neuronal injury. The dashed orange line indicates that synaptic dysfunction may be detectable in apolipoprotein E (ApoE) ε4 carriers before detectable Aβ deposition. Brain atrophy on structural MRI (sMRI; blue) and subtle decline in cognitive function (purple) mark the transition from preclinical AD to mild cognitive impairment (MCI). (B) Hypothetical staging of preclinical AD. Stage 1 and 2 individuals may not progress to stage 3, whereas stage 3 individuals may be more likely to progress to MCI and AD. Reprinted from Alzheimer’s and Dementia, Sperling et al., Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease, 7 (3): 280-292, with permission from Elsevier

CSF Core Biomarkers

The CSF is in direct contact with the extracellular space of the brain and serves as a substrate for biochemical changes related to brain pathology. With respect to AD, the current core CSF biomarkers—Aβ42, total tau, and phospho-tau (phosphorylated specifically at residue T181)—are assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or multiplexed assays as surrogates for mounting neuropathologic plaque and neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) lesions. Hence, it is generally thought that lower CSF Aβ42 levels correlate with accumulating plaque deposition and higher CSF tau levels correlate with neuronal injury during AD progression.

Early CSF biomarker studies were cross sectional and focused on differentiating AD from control patients. After it was found that Aβ is generated as a soluble protein during normal cellular metabolism and secreted into the CSF [20], biomarker research found that CSF total Aβ was decreased slightly in AD [21, 22]. However, as these initial findings did not discriminate between different Aβ isoforms, there was considerable overlap between patients with AD and controls, while other studies reported no change in CSF total Aβ in AD [23]. As the Aβ42 isoform was found to be more prone than Aβ40 to aggregate at physiologic pH and form the nidus of senile plaques [24, 25], subsequent analysis of CSF Aβ42 used C-terminal-specific antibodies. These early reports consistently showed a ~50% decrease in Aβ42 in moderate AD compared with age-matched control subjects [26–29].

The first study of CSF total tau as a biomarker for AD used a pan-tau antibody that recognized both unphosphorylated and phosphorylated tau, and reported an ~1000% increase in CSF tau from older patients with AD compared with younger adult controls [30]. Subsequent age-matched studies using tau monoclonal antibodies that detect all isoforms of tau independently of phosphorylation state found an ~200% to 300% increase in total tau in AD [31–33]. ELISA methods were also developed for phospho-tau as a putative readout of tau pathology by targeting epitopes associated with NFTs, including threonine 181, threonine 231, and serine 396 + 404 (the PHF-1 epitope), among others, with observations of up to ~300% increases in these phospho-tau moieties in the CSF of patients with AD [34–36]. Blennow [37] evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of core CSF biomarkers for differentiating AD from controls. CSF Aβ42 demonstrated a mean sensitivity of 86% and a mean specificity of 89%. By contrast, total tau yielded a mean sensitivity of 81% and a mean specificity of 91%, whereas the diagnostic accuracy of multiple forms of phospho-tau also yielded a mean sensitivity of 81% and a mean specificity of 91% [37]. Moreover, combining measurements of Aβ42 and tau concentrations in CSF improved diagnostic potential. For example, the CSF ratio of phospho-tau (T181) to Aβ42 was found to be superior to either measure alone for identifying AD among controls and other neurologic diseases, with a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 97% [38]. Another report revealed a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 86% using the CSF ratio of total tau to Aβ42 [39]. While Aβ42 demonstrates good sensitivity for differentiating AD from nondemented subjects, combining CSF Aβ42 and tau measures for the differential diagnosis of AD appears to mitigate some of the nonspecific biochemical characteristics of Aβ42, which is also reduced in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, multiple system atrophy, Lewy body dementia (LBD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), vascular dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and neuroinflammation, in addition to AD [40, 41]. However, CSF phospho-tau levels are particularly useful in differentiating AD from other dementias such as LBD, FTD, and vascular dementia with more than 80% specificity [42].

CSF biomarker development naturally extended to longitudinal studies and the utility of Aβ42, total tau, and phospho-tau for predicting conversion from NCI to MCI and to AD. In this regard, high CSF total tau and low CSF Aβ42 was found in 90% of MCI cases that progressed to AD compared with 10% of stable MCI cases [43]. Likewise, high CSF phospho-tau (T231) was also found in MCI cases that progressed to AD compared with stable MCI cases and correlated with decline on neuropsychological testing [44, 45]. Several additional longitudinal studies of clinically well-characterized cohorts validated the concept that the CSF core biomarkers could be used to help predict likelihood of conversion. Notably, Hansson et al. [46] showed that the combination of high total-tau with a low Aβ42/phospho-tau (T181) ratio at baseline yielded 95% sensitivity and 87% specificity for the detection of incipient AD. Fagan et al. [10] compared baseline CSF samples from 139 patients with Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scores of CDR 0 (cognitively normal or NCI), CDR 0.5 (MCI or very mild AD), or CDR 1 (mild AD) with follow-up clinical assessments [10]. Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for age, sex, education, and APOE genotype revealed that participants with CSF total tau/Aβ42 and phospho-tau (T181)/Aβ42 significantly predicted conversion from CDR 0 to CDR greater than 0, with higher ratios predicting a faster rate of conversion than those with low ratios [10]. Interestingly, the tau/Aβ42 ratios were similar in CDR 0.5 (MCI) and CDR 1 (mild AD), underscoring the diagnostic potential of the biomarker for identifying prodromal disease. A more recent analysis of CSF samples from patients in the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort showed that the tau/Aβ42 ratio was the most robust combination for predicting dementia due to AD in subjects with MCI [47].

Given the effects of apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4) gene dosage on the risk of AD and age at dementia onset [48], several groups have evaluated biomarker trajectories as a function of ε4 allele number, with varying agreement [49–53]. Most recently, 2 studies examined the effects of ApoE4 on longitudinal CSF core biomarkers within cohorts of cognitively normal middle-to-older-aged subjects. Sutphen et al. [52] found that ε4 homozygotes yielded among the lowest CSF Aβ42 levels, whereas ε4 noncarriers were associated with the highest CSF Aβ42 levels, with heterozygotes falling in the middle range. Moreover, longitudinal increases for total tau and total tau/Aβ42 and decreases in cognitive function appeared to overlap to a greater extent in ε4 carriers than in noncarriers [52]. Likewise, Toledo et al. [53] found that ε4 carriers showed higher CSF tau and lower Aβ42 values than ε3/ε3 patients, with the largest effect observed for Aβ42. Whereas Aβ42 values remained stable up to the beginning of the seventh decade in healthy controls without any ε4 alleles, Aβ42 levels of healthy controls with 1 or 2 ε4 alleles showed a decrease beginning during the fifth decade of life and plateaued at the middle of the eighth decade. Hence, the ApoE gene dosage risk factor for AD may be reflected in CSF biomarkers—particularly low Aβ42 levels—in middle age as a potential signal for the onset of preclinical AD.

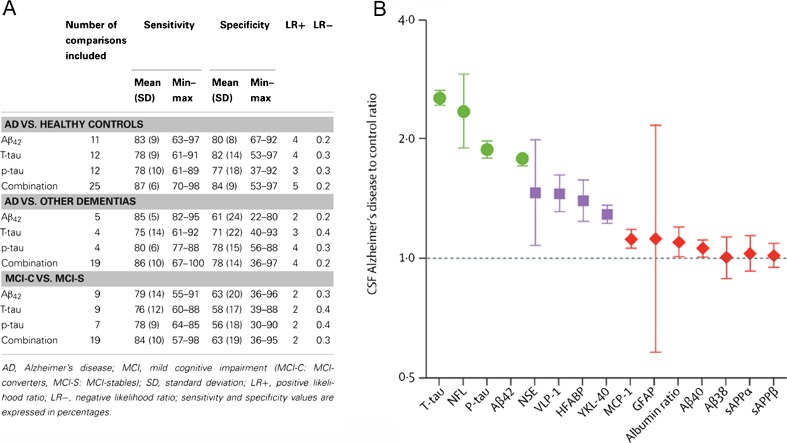

The progression from single-center studies to multicenter efforts were initially faced with problems related to intersite differences such as CSF collection, storage methods and assay platforms [54]. For example, a 12-center study of 750 individuals with NCI, MCI, and AD recruited in Europe and the USA found that the combination of CSF Aβ42/ phospho-tau (T181) and total tau identified incipient AD within the MCI group with fairly good accuracy, but with lower sensitivity (83%) and specificity (72%) than reported for single-center studies [11]. The Aβ42 assay had considerable intersite variability, and the authors highlighted the need for standardization of analytical techniques and clinical diagnostics [11]. Indeed, standardization efforts became a major focus for multisite studies, including the AD Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Within the Biomarker Core of ADNI, efforts were made to standardize the analysis of all collected baseline CSF samples by using the same multiplexed xMAP bead-based platform (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) with Aβ42, phospho-tau (T181), and total tau monoclonal antibodies provided in the INNO-BIA Alz Bio3 immunoassay kit (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium). The initial utility of the approach was demonstrated by comparing cut-off values of Aβ42, phospho-tau (T181), and total tau in an ADNI clinical cohort of control participants, and subjects with MCI and AD and comparing those values with CSF from independent, autopsy confirmed control and AD cases [55]. The baseline CSF profile for total tau/Aβ42 was detected in 33 of 37 ADNI participants with MCI who converted to probable AD during the first year of the study. By contrast, Aβ42 cut-off values derived from the ADNI cohort was the most sensitive biomarker for AD in the autopsy cohort, with a receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (AUC) of 0.913 and sensitivity for AD detection of 96.4% [55]. Using this same standardized procedure, Shaw et al. [56] analyzed within-site and intersite assay reliability across 7 ADNI centers using aliquots of CSF from normal controls and patients with AD. Each center performed 3 analytical runs using separate fresh aliquots of each CSF sample examined and data were analyzed using mixed-effects modeling to determine assay precision. The coefficient of variation was 5.3% for Aβ42, 6.7% for total tau, 10.8% for phospho-tau within centers, and 17.9% for Aβ42, 13.1% for total tau, and 14.6% for phospho-tau between centers [56]. More recently, Toledo et al. [57] investigated biomarker changes in ADNI controls, and subjects with MCI and AD across multiple centers over a 4-year period using standardized procedures [57]. In this study, clinical diagnosis was associated with abnormal baseline levels of both Aβ42 and total tau, or with abnormal phospho-tau (T181) levels alone. Moreover, low baseline Aβ42 predicted greater increases in phospho-tau (T181) levels on follow-up, whereas neither baseline total tau nor phospho-tau was associated with an Aβ42 decrease during follow-up, suggesting that changes in Aβ42 levels precede tau levels [57]. Notably, the longitudinal stability of these biomarkers varied in patients with normal baseline levels: 1 group remained stable over time, whereas the other had decreasing Aβ42 and increasing phospho-tau (T181) levels over time. When the stable population was excluded from analysis, the time taken to reach cut point levels of biomarkers was significantly shortened. Hence, longitudinal analysis of CSF biomarkers revealed substantial cohort heterogeneity and the lack of a clear association between level changes and cognitive status, at least over a span of 4 years. However, the suggestion that changes in Aβ42 levels precede tau levels reflects a similar finding in a European cohort showing that levels of Aβ42 are already fully decreased at least 5 to 10 years before conversion to AD, whereas increases in the tau markers appear later for converters [58]. However, as proposed by the new working criteria for AD, the appearance of elevated baseline CSF tau and other markers of neurodegeneration may reliably predict the onset of cognitive impairment in preclinical subjects [10, 59]. Hence, despite lingering pre- and post-analytic issues of intersite variability, the CSF core biomarkers developed to date are useful for the early diagnosis of AD and prediction of disease progression (Fig. 2). Altered baseline levels in these markers, used in combination with imaging and other novel fluid biomarkers, as discussed below, may be clinically beneficial for the reliable identification of preclinical and prodromal disease for the efficient design of drug intervention clinical trials (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Summary of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker diagnostic performance. (A) Sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios of CSF core biomarkers based on primary studies published after the introduction of new criteria recommended by the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association workgroups [96].* (B) Head-to-head CSF biomarker performance based on average Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to control ratios. Biomarkers are differentiated based on significant differences with good effect sizes (green), significant differences with moderate effect sizes (purple), or nonsignificant or significant with minor effect sizes (red) [97]** *Reprinted from Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 6, 47, Ferreira et al., Meta-review of CSF core biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: the state-of-the-art after the new revised diagnostic criteria, pp. 1-24, 2014 (Open Access). **Reprinted from The Lancet Neurology, Olsson et al., CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis, doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00070-3 2016, with permission from Elsevier.

Novel CSF Biomarkers

Despite the promise for CSF core biomarkers for the identification of presymptomatic AD, the inherent heterogeneity in the progression of mounting plaque and tangle load over time between patients, as well as the presence of mixed pathologies and different comorbidities, highlight the need to augment the CSF core biomarkers with novel proteins to improve diagnostic accuracy in longitudinal studies [60–62]. A growing list of candidate biomarkers for AD derived from the CSF has been proposed, including apolipoprotein isoforms [63, 64], brain-derived neurotrophic factor [65], prostaglandin D2 synthase:transthyretin dimers [66], synuclein isoforms [67, 68], ubiquitin [69, 70], SNAP-25 [71], neurogranin [72–74], visinin-like protein 1 (VILIP-1) and chitinase-3-like protein 1 (YKL-40) [52, 75, 76], and the neurofilament light chain (NFL) [77–79]. In particular, a longitudinal CSF analysis of the postsynaptic protein, neurogranin, in 378 healthy controls and subjects with MCI and AD revealed significantly higher neurogranin in MCI converters and patients with AD compared with controls and MCI nonconverters [74]. Neurogranin was strongly correlated with CSF tau but not Aβ42 levels, and high neurogranin levels were significantly associated with deterioration in cognitive performance, hippocampal volume on MRI, and cortical glucose metabolism on FDG-PET in healthy controls [74]. Likewise, CSF levels of the neuronal calcium sensor VILIP-1 differentiated CDR 0.5 to 2 from CDR 0 controls and individuals with other dementias such as LBD and FTD and correlated with CSF tau, phospho-tau (T181), and brain volume. CSF VILIP-1/Aβ42 predicted future cognitive impairment at least as well as the tau/Aβ42 ratios, and VILIP-1 and VILIP-1/Aβ42 accurately predicted the presence or absence of amyloid PET positivity, regardless of clinical diagnoses, suggesting its augmentative utility for preclinical AD screening [80]. NFL has also emerged as a potential surrogate marker for disease pathogenesis related to axonal pathology. In this regard, a recent study using cases from the ADNI cohort showed that CSF NFL was higher in subjects with MCI and AD than individuals with NCI, and that higher NFL concentration was associated with faster whole-brain and hippocampal atrophy, white matter intensity changes, and cognitive deterioration over time [79]. Another potential CSF marker for disease progression is pro nerve growth factor (proNGF), which is the predominant NGF moiety in brain that displays dual survival/apoptotic properties and is increased in MCI and AD postmortem brain tissue [81–83]. Our group recently showed that CSF levels of proNGF were higher in subjects with amnestic MCI and mild AD, as well as CDR 0.5 and 1, than in people with NCI or CDR 0, respectively [84]. Increasing CSF proNGF was significantly associated with cognitive deterioration, and the combination of proNGF/Aβ42 performed better than tau/Aβ42 for distinguishing amnestic MCI from controls [84]. Collectively, these novel CSF biomarkers could reflect molecular changes associated with disease pathogenesis, including deficiencies in synaptic function and cell survival factors.

With respect to inflammatory pathways, the proinflammatory chitinase YKL-40, which was isolated initially in a proteomic screen, displayed significantly higher levels in CDR 0.5 and 1 compared with CDR 0 individuals in a discovery and validation cohort, with CSF YKL-40/Aβ42 ratio predicting the conversion from CDR 0 to CDR > 0, as well as total tau/Aβ42 and phospho-tau (T181)/Aβ42 [85]. Other notable promising CSF candidate markers include protein modulators of the endosomal–autophagy–lysosomal system [86], which may reflect the major disturbances found in these pathways in MCI and AD [87–89]; protein and lipid markers of oxidative stress in MCI and AD [90–92]; and alterations in microRNA profiles that may reflect underlying dysregulation of amyloid and tau pathways [93–95]. Two recent meta-reviews [96, 97] provide a current state of the field with respect to the utility of CSF core (Fig. 2A) and novel (Fig. 2B) biomarkers for identifying people at risk for dementia. As the most rigorously tested surrogates for AD pathogenesis, CSF amyloid-beta Aβ and tau levels will continue to help refine a reliable composite biomarker along with imaging and cognitive parameters. Ultimately, the addition of novel biomarkers to augment the differential diagnosis of AD and other dementias in their preclinical and prodromal stages may provide a front-line screen for early intervention and optimal subject recruitment for clinical trials.

Molecular Neuroimaging Biomarkers

The development of PET radioligands for the in vivo detection of fibrillary Aβ deposits and intracellular tau aggregates has provided a significant advance in biomarker development, complementing CSF studies and expanding our knowledge of how early amyloid plaques and NFTs begin to develop in the preclinical phases of AD. Although the relative role that these hallmark AD pathologies play in the onset of synaptic loss, neuronal cell death, and clinical symptoms of MCI and early AD remain to be determined, it is becoming evident that they precede clinical onset by years or decades [1].

Although amyloid PET and CSF biomarkers can identify early AD with similar accuracy [98], highly sensitive imaging radioligands used in combination with other novel AD biomarkers will be critical for timely initiation of therapy trials in pathological aging, MCI, and early AD.

Pittsburgh compound B [PiB; [C-11]6-OH-BTA-1; [N-methyl-11C]2-(4’-methylaminophenyl)-6-hydroxybenzothiazole] is the most widely used amyloid imaging agent and the first Aβ selective radiotracer to differentiate AD from NCI by PET [99, 100]. PiB binds with a high affinity to β-sheet structured amyloid aggregates [101], and owing to its good brain penetrance and fast clearance is suitable for PET imaging [102]. In NCI controls, PiB PET retention is typically low in cortical, subcortical, and cerebellar regions, while in AD it is high in cortical regions displaying Aβ plaques at postmortem evaluation [103]. With respect to CSF core biomarkers, a strong concordance between PiB-PET and CSF Aβ42 was seen in mixed cohorts of NCI and AD [104, 105], or NCI, MCI, and AD [106], with no correlation between PiB-PET and CSF tau [104]. These findings were corroborated in other cohorts with NCI [107], MCI [108, 109] and AD [105]. Some longitudinal studies suggested that amyloid PET may be more sensitive than CSF Aβ42 in identifying subjects with MCI who will convert to AD. Forsberg et al. [108] reported that all those with MCI who converted to AD had high PiB PET retention, but less than half of them had pathological CSF Aβ42. In another study, 87% of MCI cases had high PiB retention, with only 53% having pathological CSF Aβ42 [109]. A clinical-pathological study of a PiB-negative patients with NCI reported that 12 months after PET scan there was a decrease in CSF Aβ42 and a slight increase in CSF tau and p-tau concentrations, and 6 months later the individual transitioned to MCI [110]. In this case, brain autopsy revealed primarily diffuse Aβ plaques in the neocortex, suggesting that compared with PiB-PET, CSF Aβ42 is a more sensitive biomarker for detection of AD pathology [110].

Postmortem brain studies indicate that PiB binding is most prominent in classic neuritic plaques and vascular Aβ deposits [cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)] [111–114], yet it does not bind to NFTs or non-AD neuropathology [112, 115–118]. While both Aβ plaques and CAA can contribute to PiB- retention in vivo, CAA is most frequent in the occipital lobe, which is less affected with plaques when compared with other cortical regions [119, 120]. Johnson et al. [119] reported that all nondemented subjects diagnosed with clinically probable CAA and all AD subjects were PiB-positive. Global cortical PiB retention in CAA was greater relative to NCI cases, and lower than in AD; however, the occipital-to-global PiB ratio was greater in CAA than in AD, similar to other CAA cohorts [121]. An autopsy evaluation of a PiB positive patient with mild AD (CDR = 1; Mini-Mental State Examination score = 25) and a clinical diagnosis of LBD found numerous neocortical diffuse Aβ plaques but only rare cored plaques and severe CAA [111]. These mixed results support the need for postmortem evaluation of PiB-PET-imaged brains for validating radioligand sensitivity and specificity, and for estimating the threshold level of underlying pathology for PET positivity. Moreover, the presence of Aβ deposits in PiB negative patients with NCI and MCI brings into question the sensitivity of PiB for detecting fibrillary Aβ [110, 117, 122]. Several studies used postmortem brain tissue analysis and in vitro [H-3]PiB binding to validate PiB’s utility in quantifying fibrillar Aβ load and to distinguish among NCI, MCI, and AD. [H-3]PiB binding in the precuneus cortex was significantly higher in AD compared with NCI and MCI groups, and greater [H-3]PiB binding levels correlated strongly with a more severe CERAD (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease) pathology scores and antemortem cognitive impairment [123, 124]. In other studies, [H-3]PiB binding in multiple brain regions was able to distinguish between clinical categories, and correlated with concentrations of fibrillar Aβ by ELISA [125, 126].

About 10% to 20% of patients with clinical AD are PiB negative, in agreement with autopsy reports, suggesting that they may have been clinically misdiagnosed [4, 100]. In a study using [F-18]florbetapir PET imaging, amyloid PET-negative individuals with AD and MCI were more likely to be ApoE4-negative, exhibit lower CSF tau concentrations, and perform better on longitudinal cognitive testing, while amyloid PET-negative subjects with MCI also had milder hippocampal atrophy and hypometabolism [127]. It is also well established that 20% to 30% of NCI subjects are PiB positive [99, 118, 128–132], consistent with autopsy evidence of significant AD pathology in NCI cases [7, 133, 134]. This incidence increases up to 65% in those aged > 80 years [135]. However, these observations are influenced by a study center’s threshold for defining amyloid positivity, its clinical definition of “cognitively normal”, and ApoE genotype status. ApoE4 is associated with higher PiB PET retention in elderly NCI [131, 136], while in people with MCI it confers an increased likelihood of converting to AD [137, 138]. Compared with noncarriers, ApoE4-positive patients with a PiB negative scan have more than double the rate of progression to PiB positive [139], reminiscent of ApoE4 effects on lower CSF Aβ42. An association between ApoE4 and increased PiB PET retention was reported in cross-sectional [140] and longitudinal [141] analyses of AD cohorts, while some investigations found no such association [99, 138, 142], and ApoE2 was associated with lower PiB PET retention [136]. The reason for preserved cognition despite significant plaque load in PiB positive NCI is not clear. It has been suggested that resilience to AD pathology can be due to less advanced “maturation” of amyloid plaques, preservation of neurons and synapses, less accumulation of soluble tau in synapses, and less severe inflammatory responses [143]. Nevertheless, PiB positive individuals with NCI are at risk for developing cognitive decline when compared with PiB negative individuals with NCI matched by age and education [132, 144–146], and PiB positive in elderly people with NCI is a marker for preclinical AD [1]. Similarly, PiB positive subjects with MCI are more likely to convert to AD [108, 109, 146], and individuals with amnestic MCI are more likely to be PiB positive than those with nonamnestic MCI [147, 148]. Thus, amyloid PET imaging is useful in identifying people that will develop AD, or those with pathology unrelated to AD.

One of the main drawbacks of PiB-PET imaging is the short radioactive half-life of carbon-11 (~20 min), which limits the distribution of [C-11] PiB to PET imaging centers with on-site cyclotrons. However, longer-lived fluorine-18 (F-18)-labeled amyloid PET tracers have been developed that are similarly effective in detecting fibrillar Aβ pathology [149, 150]. [F-18]flutemetamol is a 3’-fluoro analog of PiB (3’-F-PiB) with similar retention characteristics, although slightly greater retention in white matter [151]. In a phase I clinical study of subjects with NCI and mild AD, the AD group had greater retention of [F-18]flutemetamol in the neocortex and striatum but not in the white matter, cerebellum, and pons [152]. A multicenter phase II trial of [F-18]flutemetamol in 15 older patients with NCI (>55 years), 10 young subjects with NCI (<55 years), 20 patients with amnestic MCI, and 27 patients with early AD reported 93.1% sensitivity and 93.3% specificity [153]. As expected, regional retention levels of [F-18]flutemetamol and PiB correlated strongly in MCI and AD [153], supporting the notion that these 2 related tracers are comparable in detecting fibrillar Aβ deposits in vivo. A clinicopathological study in a large end-of-life population demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity of [F-18]flutametamol [154]. [F-18]florbetapir [(E)-4-(2-(6-(2-(2-(2-[F-18]-fluoroethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)pyridin-3-yl)vinyl)-N-methyl benzenamine; [F-18]AV-45; or amyvid] [155] has also proven to be effective in imaging Aβ fibrillar pathology in vivo [156]. Those with AD displayed higher [F-18]florbetapir retention in cortical regions when compared with NCI, while white matter and cerebellar retention was not different between AD and NCI [157]. In a large multicenter trial, positive [F-18]florbetapir PET scans were seen in 28% of NCI (>55 years old), 47% of MCI, and 85% with AD [158]. [F-18]florbetapir PET was negative in subjects with NCI younger than 50 years of age, and correlated with neuritic plaques assessed postmortem in 29 terminally ill patients [159]. High sensitivity and specificity was reported for [F-18]florbetapir PET using global cortical standardized uptake value ratio to differentiate AD from NCI [160]. [F-18]florbetaben [(E)-4-(2-(4-(2-(2-(2-[F-18]fluoroethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)phenyl)-vinyl)-N-methyl-benzenamine; [F-18]AV-1 or BAY-94-9172] has higher neocortical PET retention in AD compared with NCI or patients with FTD [161, 162]. Increased [F-18]florbetaben gray matter retention was reported in AD compared with MCI or non-AD dementias [163]. High sensitivity and specificity of [F-18]florbetaben was seen in a multicenter phase II study consisting of 69 subjects with NCI and 81 with clinically probable AD [164], a single-center phase 0 study of 10 subjects with NCI and 10 patients with clinically probable AD [165], and in a clinicopathological study from a multicenter phase III trial [166]. These studies indicate the utility of these new tracers as markers for AD.

Non-amyloid PET imaging methods can provide complementary information, such as assessing neuronal dysfunction with FDG-PET [167]. In patients with AD, decreased FDG-PET levels of cerebral glucose metabolism show a typical regional pattern of posterior temporoparietal to frontal hypometabolism [168–170]. Similar changes in cerebral metabolism were reported in NCI individuals with an ApoE4 allelle [171, 172], and in MCI [173–180]. FDG PET also predicted progression from NCI and MCI to AD [181–183]. The relationship between PiB-PET and FDG-PET remains to be determined in studies involving large cohorts of individuals with NCI, MCI, and AD. Agreement between these 2 methods is high in differentiating AD from NCI, but lower in classifying those with MCI [184]. MCI subjects were noticed to display positive correlations between PiB-PET and FDG-PET, possibly reflecting increased brain reserve in nonconverting MCI subjects [185]. Lowe et al. [147] reported that PiB-PET and FDG-PET had similar diagnostic accuracy, however, PiB PET was significantly better at separating MCI subtypes. In contrast, others have not observed significant correlations between PiB-PET and FDG-PET in patients with AD, and cognitive performance correlated strongly with FDG-PET but not with PiB-PET [186]. Amyloid deposition and brain atrophy are common in older individuals with NCI and MCI [100], and hippocampal atrophy can be detected in elderly NCI, MCI and AD using structural MRI [187–191]. MRI studies demonstrated that the rate of hippocampal atrophy is associated with conversion from MCI to AD [189, 192–197]. Globally, cerebral atrophy is observed spreading from within the MTL (i.e., hippocampal volume and entorhinal cortex thickness) to the parietal, occipital, and frontal lobes over the course of the disease, with future MCI converters most closely reflecting this pattern and exhibiting the highest rates of change [198–200]. Notably, a significant positive correlation was reported between rates of whole-brain atrophy on volumetric MRI and cortical PiB PET retention in AD [201–204].

AD is a multiproteinopathy with fibrillar aggregates of both Aβ and tau. While Aβ is widely believed to precede tau pathology, when compared with amyloid plaques NFTs correlate better with cognitive dysfunction in AD [205]. Thus, the recent development of tau-specific tracers has been an important advance to complement amyloid imaging, although less vigorously characterized and validated [206]. Multiple challenges associated with development of tau ligands relate to different ultrastructural and isoform composition of tau deposits, and have been addressed elsewhere [207]. Several groups reported tau-selective PET radioligands, including [F-18]-labeled THK compounds [208–217]; PBB compounds [218–220]; and [F-18]-labeled T807 and T808 compounds [18, 19, 221–224]; and with the tau imaging field developing rapidly new PET tracers are emerging [225]. Characterization studies of many of these tau candidate ligands are ongoing in subjects with NCI and AD, while studies of MCI are just emerging. [F18]AV-1451 (or [F18]T807) has a promising pattern of retention corresponding to known distribution of NFT in AD brains [226]. This ligand shows an association with cognitive impairment [17, 227], greater PET retention in the oldest with NCI [19], MCI, and AD compared with younger subjects with NCI [221]. In elderly NCI from the Harvard Aging Brain Study Cohort, cortical [18-F]AV-1451 PET correlated with CSF measures of total tau and phosphorylated tau [228]. [18-F]AV-1451 PET was abnormally high in cortical, entorhinal, and parahippocampal regions (but not in the hippocampus) in individuals with MCI and AD compared with patients with NCI and greater radioligand retention in the inferior temporal gyrus correlated with impaired cognition [18, 19]. Another study of [18-F]AV-1451 PET (20 patients with NCI, 15 with MCI, and 20 with AD) observed that retention was increased in multiple cortical regions in patients with AD and in the entorhinal cortex in MCI; increased PET retention correlated with impaired global cognitive performance [229]. It has also been reported that regional [F-18]AV-1451 PET retention corresponded to clinical manifestation of AD and increased [F-18]AV-1451 PET signal in the hippocampus correlated strongly with regional structural MR (volume) impairment only in the presence of Aβ pathology [230]. Although these reports indicate that [F-18]AV-1451 may be an additional tool for diagnosing AD, a lack of extensive imaging-to-postmortem validation impedes further advancement in the field [206]. Only a limited in number tau ligand autoradiographic investigations using autopsy tissue sections have compared AD with non-AD tauopathy cases. Two studies have reported that AV-1451 binds preferentially to AD tau isoforms and displays a binding distribution corresponding better to NFTs than to Aβ plaques [231, 232]. While binding to TDP-43 and α-synuclein pathology was minimal or absent, these studies identified off-target binding in some areas, which requires further investigation [231, 232]. Another investigation of [F-18]AV-1451 binding using postmortem brain tissue also reported high specific signal in AD compared with non-AD tauopathies, however, no correlation was observed with tau pathology load within groups [233]. [F-18]AV-1451 imaging combined with postmortem histopathology of an autopsy case carrying the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene mutation showed a strong correlation between regional tau pathology and antemortem PET retention [234]. The extent to which tau PET radioligands can discriminate between the accumulation of tau pathology in AD and other age-related tauopathies remains to be determined [235].

Although amyloid and tau PET imaging represent major advances in AD, there are still a number of limitations and unresolved questions. In contrast to their good specificity, the sensitivity of PiB-PET imaging and related [F-18] ligands is not well characterized for relatively low but histologically detectable Aβ deposits. Analyses of large numbers of PET-positive and PET-negative cases, with short imaging-to-autopsy interval, will be required to establish threshold levels of Aβ and tau pathologies necessary for diagnostic accuracy. A major challenge for neuroimaging in AD is how to determine the onset of amyloid and tau accumulation in pathology-burdened individuals with NCI and MCI, and its association with cognitive measures and CSF biomarkers. As the field focuses on PET imaging studies to help determine the clinical significance of presymptomatic pathology and identify people at risk for cognitive decline, more studies are needed to compare directly the relative merit of amyloid and tau PET to CSF biomarkers, MRI, FDG, and clinical measures for earlier detection of AD, to improve the selection of patients for clinical trials, and for monitoring pathology progression and therapeutic efficacy.

Blood-Based biomarkers

The resources and costs related to CSF and imaging biomarkers make it difficult to incorporate them into routine clinical practice. Thus, there is a focus on the discovery and validation of biomarkers in peripheral blood. As blood collection is minimally invasive and inexpensive to perform, blood-based biomarkers, developed and refined based on strong concordance with CSF and brain imaging parameters, would present a significant breakthrough in moving routine screening for incipient dementia into community-based clinics. However, the seclusion of the central nervous system (CNS) from the peripheral circulatory system is a significant challenge for blood-based biomarkers to diagnose neurological disorders such as AD. Nevertheless, discovery- and hypothesis-based approaches have led to the identification of numerous biomarker candidates associated with AD in blood, plasma, and serum.

To date, plasma Aβ and tau levels have not mirrored the sensitivity and specificity of their CSF counterparts. In general, Aβ42 or Aβ40 levels in plasma are found to be either unchanged or, in cases where higher plasma levels of either Aβ42 or Aβ40 are reported for AD, there is broad overlap between patients and controls [236]. With respect to predicting AD conversion in cognitively normal people, some studies report that high plasma Aβ42, or a high Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, is a risk indicator for future AD, whereas others report the opposite [237–239]. These equivocal findings suggest that plasma Aβ does not reflect brain Aβ turnover or metabolism [28]. For instance, there is no correlation between plasma Aβ species and brain amyloid load as determined by PiB binding [104]. Plasma assays for tau have been hampered by a lack of analytical sensitivity for accurate measurement. However, the recent application of digital ELISA technology revealed that plasma tau levels were significantly higher in patients with AD compared with controls and those with MCI, but with substantial overlap among the groups, with no correlation between tau levels in plasma and CSF [240]. In a significant advance for examining amyloid and tau in blood, Fiandaca et al. [241] examined these proteins in neurally derived blood exosomes derived from patients with AD, with FTD, and healthy controls [241]. Blood exosomal levels of total tau, phospho-tau (T181), phospho-tau (S396), and Aβ42 were significantly higher in patients with AD than in matched controls, with combined levels showing 96% sensitivity. Moreover, analysis of blood exosomes in a group of AD patients at two different time points showed that the levels of these four markers were elevated in the blood of cognitively normal individuals who later developed AD, up to 10 years before clinical diagnosis of the disease [241]. Hence exosomes may provide a blood-based window into CNS activity and provide a more suitable substrate for marking preclinical AD stages.

Several studies have reported promising novel blood biomarkers for AD. Combined multivariate analysis of levels of 120 known signaling and inflammatory proteins in plasma identified 18 candidate proteins that together identified patients with AD and predicted future AD in those with MCI with high accuracy [242]. Another study using plasma from patients with probable AD and controls found a significant AD-related increase in the ratio of proatrial natriuretic peptide, a vasodilator, to carboxy-terminal endothelin-1 precursor fragment, a vasoconstrictor (training set sensitivity = 81%, specificity = 82%) [243]. O’Bryant et al. [244] performed multianalyte profiling of 396 control and AD serum samples from the Texas Alzheimer’s Research Consortium and 170 control and AD plasma samples from ADNI to develop a novel serum plasma biomarker algorithm based on 11 proteins differentially expressed between the two diagnostic groups (e.g., C-reactive protein, adiponectin, and pancreatic polypeptide). When combined with biological (e.g., glucose, cholesterol) and demographic (e.g., age, apoE status) variables, the biomarker yielded good accuracy (AUC = 0.88) comparable with the CSF total tau/Aβ42 (AUC = 0.92) for these patients [244].

More recently, Doecke et al. [245] identified a plasma biomarker panel that consisted of 18 proteins, including cortisol, ApoE, pancreatic polypeptide, and epidermal growth factor receptor, that discriminated patients with AD from healthy controls, with high sensitivity and specificity (85% and 93%, respectively). Hu et al. [246] identified 17 proteins and peptides that were associated with MCI or AD in a test cohort, which yielded four candidates in the validation cohort. Two of these four analytes, pancreatic polypeptide and ApoE, were among those included in the plasma biomarker panel developed by Doecke et al. [245]. However, Hu et al. [246] found that a different set of two plasma proteins, pancreatic polypeptide and B-type natriuretic peptide, were correlated with CSF levels of Aβ42 and total tau/Aβ42 ratios. This concordance with core CSF biomarkers suggested that these two peptides could be useful blood surrogates for predicting the progression to clinical AD.

A newly developed SOMAscan discovery-based platform was used to analyze 1129 plasma proteins simultaneously in blood samples from patients with AD and healthy controls [247]. In the discovery set, a 5-protein classifier (S100A9, CD84, CD226, AIF1, and ESAM) was identified that discriminated people with AD from healthy controls with a sensitivity and specificity of 90.0% and 84.2%, respectively, outperforming CSF tau and Aβ42 markers from the same cases. In a validation study, the classifier discriminated controls from individuals with MCI with 96.7% sensitivity and 80% specificity [247]. Finally, an unbiased mass spectrometric lipidomics approach was used to identify a plasma phospholipid panel that predicted phenoconversion to MCI or AD within a 2 to 3-year timeframe with > 90% accuracy [248]. Thus, these novel discovery-based studies in plasma may also prove useful in the detection of AD in its earliest stages.

The field of blood-based biomarkers lags behind that of CSF as there is a significant lack of standardization in collection procedures and analytical platforms, which likely provides the main source for variability and low reproducibility rates across centers [241, 247, 249]. In this regard, an initial set of guidelines was developed to standardize the preanalytical procedures related to the utilization of blood-based biomarkers [250]. Once refined, a set of universal guidelines will allow the field to more accurately assess and cross-validate potential blood-based biomarkers to home in on a panel that either augments existing core CSF and imaging parameters or provides suitable diagnostic accuracy for noninvasive, low-cost screening for incipient dementia in community settings.

Circulating Autoantibodies as Biomarkers

Blood-based autoantibodies against neuronal proteins associated with neuroinflammation, vascular dysfunction/blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption, and altered cholesterol/lipid metabolism suggest that autoimmunity markers may correlate with specific stages in the pathophysiology and comorbidities associated with AD.

The initial indication that autoimmunity could play role in the pathophysiology of AD was based on the identification of Aβ autoantibodies in cognitively normal older individuals [251–253]. Based on these results, active and passive amyloid immunotherapy has been tested in patients with AD [254–256]. Although active immunotherapy did not prove to be an effective treatment for patients with AD, administration of anti-Aβ antibodies is still currently being tested in patients with AD as therapeutic agents (i.e., aducanumab) [257–259]. The results released from the phase Ib trial for aducanumab indicate an encouraging reduction in brain amyloid and slowing of cognitive decline in patients with CDRs of 0.5 and 1.0 [259]. Nevertheless, while the scientific community anxiously awaits the results of passive Aβ immunotherapy in phase III trials, other autoantibodies have been identified as potential diagnostic biomarkers for AD [260, 261].

The use of protein, peptides, and even peptoid arrays has led to the identification of autoantibodies specific to patients with AD. Autoantibodies against targets involved in synaptic activity, including neurotransmitters and receptors, are associated with cognitive decline, suggesting their use as signals of brain malfunction [262–271] (Table 1). With respect to inflammation, the relationship between neurodegeneration and autoimmunity was recently genetically confirmed in an epidemiological study where specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms in TREM2 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2) and complement factors were shown to overlap between AD and immune diseases [272]. These findings suggest that alterations of the BBB and activation of neuroinflammation are intrinsic components of AD pathophysiology. In this regard, autoantibodies against glial fibrillary acidic protein and S100β have been associated with leakiness of the BBB and peripheral immune cell access to the CNS [263, 273]. Autoantibodies against other proteins that modulate the BBB have also been identified (Table 1) [274, 275]. Detection of autoantibodies is also associated with metabolic dysfunction and oxidative stress [276–281] (Table 1). Autoantibodies against proteins involved in energy metabolism, such as aldolase and adenosine triphosphate synthase β, have also been shown to be significantly higher in the sera of patients with AD than in healthy individuals [282–284]. The role of the antigenic proteins and the role of autoimmunity in the pathophysiology of AD is still unclear, but there is enough evidence to suggest that further studies could lead to the establishment of an autoimmune panel with increased specificity and sensitivity for differentiating among AD, normal aging, and other dementing disease processes.

Table 1.

Autoantibodies found associated with Alzheimer’s disease

| Biological function | Target protein | References |

|---|---|---|

| Synaptic transmission | Dopamine | [262, 263] |

| Serotonin | [262, 263] | |

| Glutamate | [262, 263] | |

| Hydroxytryptamine | [262, 263] | |

| Adrenergic receptors | [264, 265] | |

| N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors | [266–268] | |

| Nicotinic acetycholine receptor | [269] | |

| Amphiphysin-1 | [270] | |

| Proopiomelanocortin | [271] | |

| Inflammation | Glial fibrillary acidic protein | [263, 273] |

| S100β | [263, 273] | |

| Galectin 1 | [271] | |

| MAPKAPK5 | [271] | |

| Blood–brain barrier/endothelial | Rabaptin 5 | [274] |

| Angiotensin-2 type-1 receptor | [275] | |

| Metabolism | Oxidized low-density lipoproteins | [278] |

| Phosphorylcholine | [277, 279, 280] | |

| Gangliosides GM1 And GQ1b | [276, 281] | |

| Aldolase | [282–284] | |

| ATP synthase β | [282–284] | |

| Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L34 | [271] | |

| Pentatricopeptide repeat domain 2 | [271] | |

| Gene expression | FERM domain containing 8 | [271] |

| C9orf9 | [271] | |

| Centaurin, alpha 2 | [271] | |

| DnaJ homolog subfamily C | [271] | |

| Ankyrin repeat and KH domain containing 1 | [271] |

MAPKAPK5 = mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 5; ATP = adenosine triphosphate

Blood Metabolites

Lipids, amino acids, vitamins, and cholesterol are plasma metabolites that have been associated with AD [285]. Higher levels of cholesterol are associated with increased metabolism of amyloid precursor protein [286]. Consistently, a high cholesterol level in serum is associated with higher risk of cognitive impairment and AD. By contrast, reduced levels of plasma antioxidants, such as vitamin E, C, D, and others, correlated with both vascular dementia and AD [287, 288]. Recently, a panel of 24 plasma metabolites was developed as diagnostic biomarkers of AD that included phosphocholine metabolites and amino acids [289]. The differential abundance of the 24 metabolites accounted for a 90% sensitivity as biomarkers for the preclinical stage of AD. The authors anticipate challenges associated with validation and reproduction of the results obtained in different cohorts [289]. Differential comorbidities, especially metabolic disorders such as diabetes and hyperlipidemia, may also contribute to the lack of specificity and sensitivity desired for the use of metabolic biomarkers as a diagnostic tool. Moreover, current instrumentation and analytical software limitations preclude the analysis of the whole metabolome. Despite these technical obstacles, the combination of identified metabolites and autoantibodies could be a robust analytical panel for the preclinical diagnosis of AD.

Conclusion

Several potential disease-modifying drugs have been developed for AD based on translational rationales, yet have failed to show any effect on disease progression or cognitive function in clinical trials. However, these failures may simply be due to the fact that the patients with AD being treated are already too advanced to derive a clinical benefit. Thus, well-validated biomarkers for early detection and accurate diagnosis of the preclinical stages of AD will be crucial for therapeutic advancement. While positive amyloid or tau tracer retention on PET imaging, low CSF concentrations of Aβ42, and high CSF concentrations in total tau and phospho-tau are accurate biomarkers for the progression to AD, the ultimate AD biomarker panel will likely show improved reliability for detecting preclinical AD through the inclusion of novel markers that are more precisely associated with confirmed pathophysiologic mechanisms. In this regard, it is imperative to recognize AD as a multifactorial disease arising from heterogeneous etiologies, and that a combinatorial approach of imaging and fluid biomarkers reflecting disease pathogenesis integrated with genetic screening and sensitive neuropsychological testing will be required. In addition, the establishment of standards for sample collection and the unified calibration of specific instrumentation will be necessary to avoid multicenter variability. Altogether, the results described here illustrate that the field is inching closer to the development of a reliable and accurate diagnostic tool that will lead to the discovery of efficient therapeutic strategies for combating the onset of dementia.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Required Author Forms Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article. (PDF 1225 kb)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants PO1AG14449, RO1AG043375, AG025204, AG052528, R21AG026032, and R21AG042146; the Saint Mary’s Foundation, Miles for Memories of Battle Creek, MI; and Barrow Neurological Institute Barrow and Beyond.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13311-016-0481-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling RA, Karlawish J, Johnson KA. Preclinical Alzheimer disease-the challenges ahead. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:54–58. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, et al. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:397–405. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and "preclinical" Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:358–368. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::AID-ANA12>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Wilson RS. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurology. 2005;64:834–841. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152982.47274.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markesbery WR, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Davis DG, Smith CD, Wekstein DR. Neuropathologic substrate of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:38–46. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mufson EJ, Chen EY, Cochran EJ, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Kordower JH. Entorhinal cortex beta-amyloid load in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:469–490. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, et al. 2014 Update of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: A review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:e1–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer's pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:119–128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid tau/beta-amyloid(42) ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:343–349. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.noc60123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Hansson O, et al. CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2009;302:385–393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snider BJ, Fagan AM, Roe C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and rate of cognitive decline in very mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:638–645. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trojanowski JQ, Vandeerstichele H, Korecka M, et al. Update on the biomarker core of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative subjects. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattsson N, Tosun D, Insel PS, et al. Association of brain amyloid-beta with cerebral perfusion and structure in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Brain. 2014;137:1550–1561. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tosun D, Joshi S, Weiner MW. the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. Multimodal MRI-based imputation of the Abeta+ in early mild cognitive impairment. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2014;1:160–170. doi: 10.1002/acn3.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bangen KJ, Restom K, Liu TT, et al. Assessment of Alzheimer's disease risk with functional magnetic resonance imaging: an arterial spin labeling study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31(Suppl. 3):S59–S74. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brier MR, Gordon B, Friedrichsen K, et al. Tau and Abeta imaging, CSF measures, and cognition in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:338ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:110–119. doi: 10.1002/ana.24546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholl M, Lockhart SN, Schonhaut DR, et al. PET imaging of tau deposition in the aging human brain. Neuron. 2016;89:971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Esch F, et al. Isolation and quantification of soluble Alzheimer's beta-peptide from biological fluids. Nature. 1992;359:325–327. doi: 10.1038/359325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farlow M, Ghetti B, Benson MD, Farrow JS, van Nostrand WE, Wagner SL. Low cerebrospinal-fluid concentrations of soluble amyloid beta-protein precursor in hereditary Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1992;340:453–454. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91771-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Nostrand WE, Wagner SL, Shankle WR, et al. Decreased levels of soluble amyloid beta-protein precursor in cerebrospinal fluid of live Alzheimer disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2551–2555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Gool WA, Kuiper MA, Walstra GJ, Wolters EC, Bolhuis PA. Concentrations of amyloid beta protein in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:277–279. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of A beta 42(43) and A beta 40 in senile plaques with end-specific A beta monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is A beta 42(43) Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT., Jr The carboxy terminus of the beta amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreasen N, Blennow K. Beta-amyloid (Abeta) protein in cerebrospinal fluid as a biomarker for Alzheimer's disease. Peptides. 2002;23:1205–1214. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(02)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreasen N, Hesse C, Davidsson P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid(1-42) in Alzheimer disease: differences between early- and late-onset Alzheimer disease and stability during the course of disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:673–680. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta PD, Pirttila T, Mehta SP, Sersen EA, Aisen PS, Wisniewski HM. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta proteins 1-40 and 1-42 in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:100–105. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sunderland T, Linker G, Mirza N, et al. Decreased beta-amyloid1-42 and increased tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2003;289:2094–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandermeeren M, Mercken M, Vanmechelen E, et al. Detection of tau proteins in normal and Alzheimer's disease cerebrospinal fluid with a sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1828–1834. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb09823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blennow K, Wallin A, Agren H, Spenger C, Siegfried J, Vanmechelen E. Tau protein in cerebrospinal fluid: a biochemical marker for axonal degeneration in Alzheimer disease? Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1995;26:231–245. doi: 10.1007/BF02815140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori H, Hosoda K, Matsubara E, et al. Tau in cerebrospinal fluids: establishment of the sandwich ELISA with antibody specific to the repeat sequence in tau. Neurosci Lett. 1995;186:181–183. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vigo-Pelfrey C, Seubert P, Barbour R, et al. Elevation of microtubule-associated protein tau in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1995;45:788–793. doi: 10.1212/WNL.45.4.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu YY, He SS, Wang X, et al. Levels of nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated tau in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's disease patients : an ultrasensitive bienzyme-substrate-recycle enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62554-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohnken R, Buerger K, Zinkowski R, et al. Detection of tau phosphorylated at threonine 231 in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurosci Lett. 2000;287:187–190. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanmechelen E, Vanderstichele H, Davidsson P, et al. Quantification of tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 in human cerebrospinal fluid: a sandwich ELISA with a synthetic phosphopeptide for standardization. Neurosci Lett. 2000;285:49–52. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. NeuroRx. 2004;1:213–225. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maddalena A, Papassotiropoulos A, Muller-Tillmanns B, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease by measuring the cerebrospinal fluid ratio of phosphorylated tau protein to beta-amyloid peptide42. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1202–1206. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.9.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapaki E, Paraskevas GP, Zalonis I, Zournas C. CSF tau protein and beta-amyloid (1-42) in Alzheimer's disease diagnosis: discrimination from normal ageing and other dementias in the Greek population. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:119–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Babic M, Svob Strac D, Muck-Seler D, et al. Update on the core and developing cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. Croat Med J. 2014;55:347–365. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2014.55.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blennow K, Dubois B, Fagan AM, Lewczuk P, de Leon MJ, Hampel H. Clinical utility of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the diagnosis of early Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang JH, Korecka M, Toledo JB, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM. Clinical utility and analytical challenges in measurement of cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta(1-42) and tau proteins as Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Clin Chem. 2013;59:903–916. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.202937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riemenschneider M, Lautenschlager N, Wagenpfeil S, Diehl J, Drzezga A, Kurz A. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and beta-amyloid 42 proteins identify Alzheimer disease in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1729–1734. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buerger K, Ewers M, Andreasen N, et al. Phosphorylated tau predicts rate of cognitive decline in MCI subjects: a comparative CSF study. Neurology. 2005;65:1502–1503. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183284.92920.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buerger K, Teipel SJ, Zinkowski R, et al. CSF tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 231 correlates with cognitive decline in MCI subjects. Neurology. 2002;59:627–629. doi: 10.1212/WNL.59.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Londos E, Blennow K, Minthon L. Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer's disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:228–234. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duits FH, Teunissen CE, Bouwman FH, et al. The cerebrospinal fluid "Alzheimer profile": easily said, but what does it mean? Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:713–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, et al. Apolipoprotein E status as a predictor of the development of Alzheimer's disease in memory-impaired individuals. JAMA. 1995;273:1274–1278. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520400044042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engelborghs S, Sleegers K, Cras P, et al. No association of CSF biomarkers with APOEepsilon4, plaque and tangle burden in definite Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2007;130:2320–2326. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lautner R, Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and the diagnostic accuracy of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1183–1191. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leoni V. The effect of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype on biomarkers of amyloidogenesis, tau pathology and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49:375–383. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sutphen CL, Jasielec MS, Shah AR, et al. Longitudinal cerebrospinal fluid biomarker changes in preclinical Alzheimer disease during middle age. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:1029–1042. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toledo JB, Zetterberg H, van Harten AC, et al. Alzheimer's disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker in cognitively normal subjects. Brain. 2015;138:2701–2715. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verwey NA, van der Flier WM, Blennow K, et al. A worldwide multicentre comparison of assays for cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46:235–240. doi: 10.1258/acb.2009.008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:403–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, et al. Qualification of the analytical and clinical performance of CSF biomarker analyses in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:597–609. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0808-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toledo JB, Xie SX, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM. Longitudinal change in CSF Tau and Abeta biomarkers for up to 48 months in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:659–670. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1151-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buchhave P, Minthon L, Zetterberg H, Wallin AK, Blennow K, Hansson O. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of beta-amyloid 1-42, but not of tau, are fully changed already 5 to 10 years before the onset of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:98–106. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pettigrew C, Soldan A, Moghekar A, et al. Relationship between cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease and cognition in cognitively normal older adults. Neuropsychologia. 2015;78:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Counts SE, Mufson EJ. Putative CSF protein biomarker candidates for amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Transl Neurosci. 2010;1:2–8. doi: 10.2478/v10134-010-0004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perrin RJ, Craig-Schapiro R, Malone JP, et al. Identification and validation of novel cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for staging early Alzheimer's disease. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e16032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roe CM, Fagan AM, Williams MM, et al. Improving CSF biomarker accuracy in predicting prevalent and incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;76:501–510. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820af900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Puchades M, Hansson SF, Nilsson CL, Andreasen N, Blennow K, Davidsson P. Proteomic studies of potential cerebrospinal fluid protein markers for Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;118:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang J, Sokal I, Peskind ER, et al. CSF multianalyte profile distinguishes Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:526–529. doi: 10.1309/W01Y0B808EMEH12L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li G, Peskind ER, Millard SP, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid concentration of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cognitive function in non-demented subjects. PLOS ONE. 2009;4:e5424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lovell MA, Lynn BC, Xiong S, Quinn JF, Kaye J, Markesbery WR. An aberrant protein complex in CSF as a biomarker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;70:2212–2218. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312383.39973.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Milne J, Andras A, et al. Alpha- and gamma-synuclein proteins are present in cerebrospinal fluid and are increased in aged subjects with neurodegenerative and vascular changes. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26:32–42. doi: 10.1159/000141039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Toledo JB, Korff A, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Zhang J. CSF alpha-synuclein improves diagnostic and prognostic performance of CSF tau and Abeta in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:683–697. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1148-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iqbal K, Flory M, Khatoon S, et al. Subgroups of Alzheimer's disease based on cerebrospinal fluid molecular markers. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:748–757. doi: 10.1002/ana.20639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I. Elevated levels of tau and ubiquitin in brain and cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(Suppl. 1):289–296. doi: 10.1017/S1041610297005024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brinkmalm A, Brinkmalm G, Honer WG, et al. SNAP-25 is a promising novel cerebrospinal fluid biomarker for synapse degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:53. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kvartsberg H, Duits FH, Ingelsson M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of the synaptic protein neurogranin correlates with cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1180–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tarawneh R, D'Angelo G, Crimmins D, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of the synaptic marker neurogranin in Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:561–571. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Skillback T, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurogranin: relation to cognition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2015;138:3373–3385. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kester MI, Teunissen CE, Sutphen C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid VILIP-1 and YKL-40, candidate biomarkers to diagnose, predict and monitor Alzheimer's disease in a memory clinic cohort. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:59. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0142-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tarawneh R, Lee JM, Ladenson JH, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. CSF VILIP-1 predicts rates of cognitive decline in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2012;78:709–719. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318248e568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Skillback T, Farahmand B, Bartlett JW, et al. CSF neurofilament light differs in neurodegenerative diseases and predicts severity and survival. Neurology. 2014;83:1945–1953. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Skillback T, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Mattsson N. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease and subcortical axonal damage in 5,542 clinical samples. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5:47. doi: 10.1186/alzrt212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zetterberg H, Skillback T, Mattsson N, et al. Association of Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Concentration With Alzheimer Disease Progression. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:60–67. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tarawneh R, D'Angelo G, Macy E, et al. Visinin-like protein-1: diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:274–285. doi: 10.1002/ana.22448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Counts SE, Mufson EJ. The role of nerve growth factor receptors in cholinergic basal forebrain degeneration in prodromal Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:263–272. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fahnestock M, Michalski B, Xu B, Coughlin MD. The precursor pro-nerve growth factor is the predominant form of nerve growth factor in brain and is increased in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:210–220. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peng S, Wuu J, Mufson EJ, Fahnestock M. Increased proNGF levels in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:641–649. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.6.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Counts SE, He B, Prout JG, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid proNGF: a putative biomarker for early Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13:800–808. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160129095649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Craig-Schapiro R, Perrin RJ, Roe CM, et al. YKL-40: a novel prognostic fluid biomarker for preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Armstrong A, Mattsson N, Appelqvist H, et al. Lysosomal network proteins as potential novel CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2014;16:150–160. doi: 10.1007/s12017-013-8269-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]