Abstract

Background

The objective of this population-based, large sample size study was to investigate the socioeconomic inequality of overweight and obesity among the elderly in Iran.

Methods

Baseline data of 3000 persons aged ≥60 years who participated in the Bushehr Elderly Health (BEH) program was analyzed. Overweight and obesity were defined as a body mass index (BMI) equal to or higher than 25 and 30, respectively. Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured by an asset index, constructed using principal component analysis, income, education level, and employment status. The Concentration Index and the Lorenz curve were used to illustrate the levels of inequality for overweight and obesity by gender.

Results

The frequencies among men and women were, respectively, 840 (57.7%) and 1131 (73.2%), P < 0.001, for overweight, and 211 (14.7%) and 511 (33.7%), P < 0.001, for obesity. There were direct associations between asset index quintiles and both overweight and obesity among both genders (Ps for trend <0.01) except for obesity among men (P for trend = 0.118). The overall Concentration Indices for overweight and obesity were 0.031 (95%CI = 0.016–0.046, P < 0.001) and 0.041 (95%CI = 0.004–0.078, p = 0.028), respectively.

Conclusion

Findings support the direct relationship between SES and obesity among women as previously reported in developing countries.

Keywords: Obesity, Overweight, Socioeconomic Status, Elderly, Iran

Background

Nowadays, non-communicable diseases are the main public health concerns. These diseases are the cause of about 5% of deaths in the world [1]. Overweight and obesity are the main risk factors for many non-communicable diseases like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, and some types of cancers [2].

Statistics show, in both developed and developing countries, that the prevalence of overweight and obesity is growing. In addition, from 1980 to 2013, there was an increase in the worldwide prevalence of overweight and obesity—from 28.8 to 36.9% in men and from 29.8 to 38.0% in women [3]. It is estimated that, in 2010, overweight and obesity caused 3.4 million deaths and led to 3.9% of the years of life lost (YLL) and 3.8% of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) in the world [3]. Twenty-three percent of ischemic heart diseases, 44% of diabetes, and 7 to 14% of some types of cancer are attributed to overweight and obesity [4]. Obesity was once associated with high-income countries, but now it is prevalent in low-income countries as well. There are countries in which obesity kills more people than underweight. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 65% of the world’s population lives in high-income and middle-income countries [4]. Therefore, the distribution of overweight and obesity is not equal in all countries, and there is some kind of inequality in its burden among countries.

Health inequalities refer to differences in health status of certain population groups, particularly between people of different socio-economic groups, that can be avoidable and unfair [5]. Various indicators have been used to determine socioeconomic status (SES) of individuals including income, education, occupation, asset/wealth, race/ethnicity, and housing characteristics. Each indicator stratifies people in a different way that affects health outcomes differently; however, these indicators are highly correlated [6]. For example although income provides a direct measurement of SES, it is advised to use asset because it provides more valid SES indicator in developing countries [7].

The prevalence of obesity varies across societies and even different groups in a society. In developed countries, obesity is considered to affect people of lower SES more [8], but there is still a debate as to whether obesity affects poor or rich people more in developing countries. According to a review study conducted in 1989, there was a positive association between SES and obesity in developing countries. Results of that study showed that obesity was a problem of richer people in the studied countries [9]. Recent evidence also indicates that the burden of obesity in developing countries tend to shift to some specific SES groups [10–12].

On the other hand, people all around the world are living longer. In 2015, there were about 900 million people aged 60 years and above in the world, and it is expected that this number will reach 2 billion people by 2050 [13]. Additionally, there were 125 million people aged 80 years and above in the world, and it is estimated that by 2050 that number will grow to about 434 million people. This process of shifting the distribution of population to older ages—which is known as population aging—started in high-income countries; now, middle-income and low-income countries are also expecting a growing percentage of the elderly in their populations. According to WHO, by the middle of the century, many countries like Chile, China, Iran, and Russia will have a proportion of elderly people to the general population similar to that in Japan. Population aging can be seen as a success for public health policies and socioeconomic development [13].

Although many studies have investigated the relationship between SES and obesity, there are few reports on that relationship in the elderly. Moreover, some reports from developing countries suffer from methodological limitations in selection of participants or measurement of SES indicators. The objective of this population-based, large sample size study was to investigate the socioeconomic inequality of overweight and obesity among the elderly in Iran, a developing country.

Methods

Baseline data of the Bushehr Elderly Health (BEH) program was analyzed in this study. The BEH Program is a population-based, prospective cohort study currently being conducted in Bushehr, Iran. The study’s rationale, design, and preliminary results were described elsewhere [14]. A total of 3000 persons aged ≥60 years were selected through a multistage, stratified cluster random sampling method from an estimated population of about 10 000 individuals. The number of participants was proportional to the number of households residing in each of 75 strata of Bushehr port, Iran.

Overweight and obesity were defined as a body mass index (BMI) equal to or higher than 25 and 30, respectively. Height was measured using a stadiometer and weight was measured after removing heavy outer garments and shoes. The BMI was defined as weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m).

We used four widely used SES indicators including: asset index, income level, educational level, and employment status in this study. To collect household asset data, we used a questionnaire in which we asked if participants owned any of 20 household assets (See Table 2 for the list of household assets). We also surveyed participants’ incomes, educational levels, and employment status (See Table 1).

Table 2.

Frequency of Home Assets owned by participants

| Asset | Frequency* | Asset | Frequency* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refrigerator | 2998 (99.93) | PC/Laptop | 1075 (35.83) |

| Freezer | 2903 (96.77 | Internet/Wi Fi | 1045 (34.83) |

| Black/White TV | 23 (0.77) | Radio | 1330 (44.33) |

| Color TV | 2034 (67.80) | Vacuum | 2593 (86.43) |

| LCD TV | 1246 (41.53) | Mobile phone | 2850 (95.00) |

| Landline | 2670 (89) | Bicycle | 170 (5.76) |

| Washing machine | 2655 (88.5) | Motorcycle | 516 (17.20) |

| Dish washing machine | 203 (6.77) | Car | 1339 (44.63) |

| Sofa | 1458 (48.60) | Boat | 27 (0.90) |

| Microwave | 783 (26.10) | Watch | 1591 (53.03) |

*[N (%)]

Table 1.

Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of participants in Bushehr Elderly Health Program

| Characteristics [N (%)] | Men [1455 (48.5)] | Women [1545 (51.5)] |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| ≤ 64 | 616 (42.3) | 674 (43.6) |

| 65–69 | 317 (21.8) | 378 (24.5) |

| 70–74 | 230 (15.8) | 200 (12.9) |

| 75–79 | 166 (11.4) | 181 (11.7) |

| ≥ 80 | 126 (8.7) | 112 (7.2) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 5 (0.3) | 20 (1.3) |

| Married | 1378 (94.7) | 884 (57.2) |

| Widowed | 68 (4.7) | 619 (40.1) |

| Divorced | 4 (0.3) | 22 (1.4) |

| Current occupation | ||

| Employed | 133 (9.1) | 23 (1.5) |

| Retired | 1195 (82.1) | 126 (8.2) |

| Unemployed* | 127 (8.7) | 1396 (90.4) |

| Education | ||

| No education | 315 (21.6) | 777 (50.3) |

| Primary school | 400 (27.5) | 459 (29.7) |

| Secondary School | 276 (19.0) | 151 (9.8) |

| High school | 287 (19.7) | 125 (8.1) |

| University | 177 (12.2) | 33 (2.1) |

| Basic health insurance | 1393 (95.7) | 1479 (95.7) |

*homemaker for female

Statistical analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to construct an asset index for each individual. We then grouped the participants into quintiles according to their asset indices [15]. PCA has been widely used to construct SES index from binary asset ownership variables such as those collected in this study in developing countries. This method reduces the number of variables into a smaller number of dimensions named principal components (PC) which are uncorrelated to each other using a multivariate statistical technique. A principal component is a linear weighted combination of household asset variables [16]. A total of 6 PCs were retained with higher eigenvalues (>1) accounting for 52.0% of the variance.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity was defined as the number of participants with overweight or obesity divided by total participants, grouped by sex, age range, and socioeconomic quintiles. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the association of BMI and asset index. A test for trends across ordered groups was used to assess if there was a linear trend for overweight or obesity prevalence across the socioeconomic levels. Additionally, Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to compare the prevalence between employment status groups.

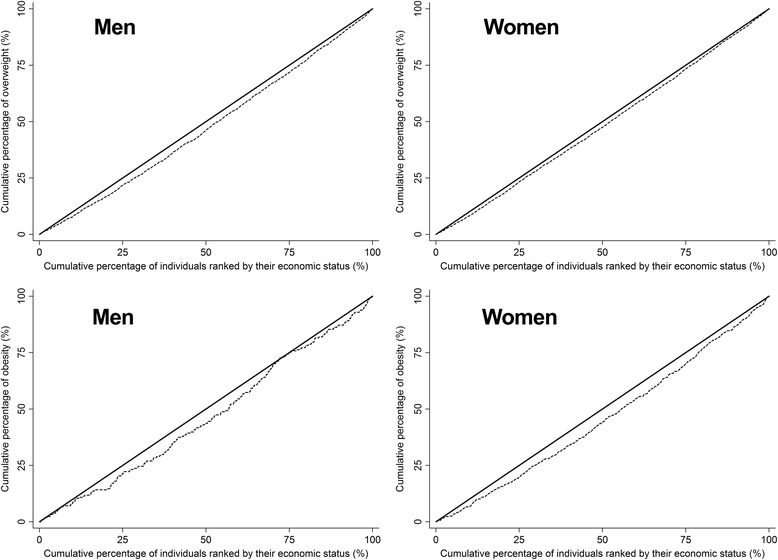

The Concentration Index, as a summary measure of health inequality, was calculated in participants with overweight and obesity by using the convenient regression method. The asset index was calculated using PCA and was considered to be the socioeconomic index in this analysis. The Lorenz curve was used to graphically present the inequality as a plot of (1) cumulative proportion of the population ranked by asset index against (2) cumulative proportion of overweight or obesity in the population. The Concentration Index is defined as twice the area between the Lorenz curve and the line of equality. The Concentration Index takes a negative sign when the Lorenz curve is above the line of equality indicating the concentration of health variable (obesity in this study) concentrates among low socioeconomic groups and vice versa [17].

P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and statistical analyses were performed using the Stata statistical package, release 13.

Results

A total of 1455 (48.5%) men and 1545 (51.5%) women with mean age and standard deviation (SD) of 67.9 ± 7.1 participated in this study. Other baseline and socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 2 presents the list of home assets identified by participants and used to construct the asset index, including the number of individuals who had each item.

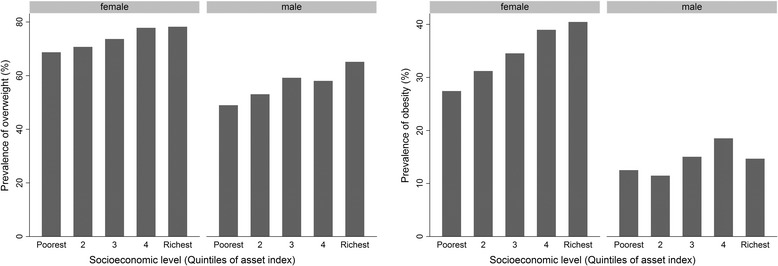

The mean and SD of BMI was 25.9 ± 4.1 kg/m2 for men and 28.3 ± 5.3 kg/m2 for women. The frequency of overweight and obesity were 840 (57.7%) and 211 (14.7%) among men, and 1131 (73.2%) and 511 (33.7%) among women, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the prevalence of overweight and obesity over asset index quintiles by sex groups, and Table 3 shows the prevalence of overweight and obesity at different socioeconomic levels.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of overweight (left) and Obesity (right) in different levels of socio-economic status by sex

Table 3.

Sex-specific Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity by Different Socio-economic Status Indices

| Overweight N (%) | Obesity N (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | P | Women | P | Men | P | Women | P | ||

| Asset Index | Quintile 1 | 116 (49.0) | <0.001* | 283 (68.7) | 0.001* | 29 (12.5) | 0.118* | 110 (27.4) | <0.001* |

| Quintile 2 | 131 (53.0) | 215 (70.7) | 28 (11.5) | 93 (31.2) | |||||

| Quintile 3 | 171 (59.2) | 229 (73.6) | 43 (15.0) | 106 (34.5) | |||||

| Quintile 4 | 181 (58.0) | 228 (77.8) | 57 (18.5) | 113 (39.0) | |||||

| Quintile 5 | 241 (65.1) | 176 (78.2) | 54 (14.7) | 89 (40.5) | |||||

| C Monthly Household Income (10,000 RLS) |

<250 | 68 (53.1) | 0.001* | 171 (65.0) | 0.006* | 14 (11.2) | 0.352* | 63 (25.2) | 0.100* |

| 250–500 | 70 (59.3) | 141 (72.7) | 17 (14.5) | 52 (27.5) | |||||

| 500–1000 | 430 (53.4) | 649 (74.5) | 113 (14.2) | 317 (36.8) | |||||

| 1000–2000 | 243 (66.8) | 140 (80.0) | 59 (16.3) | 68 (39.1) | |||||

| >2000 | 21 (70.0) | 13 (81.3) | 6 (20.7) | 6 (37.5) | |||||

| Education level | No Education | 174 (55.2) | 0.664* | 536 (69.0) | 0.256* | 47 (15.3) | 0.092* | 219 (29.1) | 0.018* |

| Primary | 227 (56.8) | 350 (76.3) | 54 (13.6) | 161 (35.5) | |||||

| Secondary | 159 (57.6) | 114 (75.5) | 43 (15.8) | 63 (42.0) | |||||

| High School | 171 (59.6) | 104 (83.2) | 49 (17.1) | 52 (41.6) | |||||

| University | 109 (61.6) | 27 (81.8) | 18 (10.2) | 16 (48.5) | |||||

| Employment Status | Employed | 75 (56.4) | 0.762† | 16 (69.6) | 0.452† | 22 (16.5) | 0.173† | 10 (43.5) | 0.122† |

| Unemployed** | 70 (55.1) | 1017 (72.9) | 11 (9.1) | 450 (32.9) | |||||

| Retired | 695 (58.2) | 98 (77.8) | 178 (15.0) | 51 (40.8) | |||||

*Ps = Trend test across ordered groups

**Homemaker for women

† P for Pearson Chi-squared test

The overall Concentration Index for overweight was 0.031 (95%CI = 0.016–0.046), P < 0.001 [0.056 (95%CI = 0.030–0.081, P < 0.001) for men and 0.035 (95%CI = 0.017–0.052, P < 0.001) for women]. Furthermore, the overall Concentration Index for obesity was 0.041 (95%CI = 0.004–0.078, p = 0.028) [0.071 (95%CI = −0.002–0.143, p = 0.055) for men and 0.086 (95%CI = 0.045–0.127, p < 0.001) for women]. Figure 2 illustrates the Lorenz curves for overweight and obesity.

Fig. 2.

Lorenz curves for overweight (top) and obesity (bottom) by sex

Discussion

Findings of the present study show that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the elderly was higher in higher socioeconomic groups. The association between SES and overweight and obesity was more obvious in women than in men. Although there were differences in the findings for various SES indicators, the highest degree of inequality was seen among women.

Sobat et al. [9] reported in their literature review that there was a reverse association between SES and obesity among women in developed countries. The association was consistent for men and children. However, the direction of the association was positive in developing countries. Since that time, many studies have investigated the relationship and approved the findings [18, 19]. Findings of the present study are consistent with the previous reports from developing countries; however, the direct association was not seen among men.

Philipson et al. [20] reasoned in their reverse hypothesis that energy imbalance (through increase in intake and decline in consumption) can explain the higher obesity prevalence in higher SES groups in developing countries. Although this is a good explanation for findings among women, it is not well understood why the results are different for men. In the present study, the relationship between SES and obesity prevalence among men resembles the one in previous studies conducted in developed countries. Dinsa et al. [21] also showed that even in the developing world, the relationship between SES and obesity in middle-income countries was mainly mixed among men, compared to the direct relationship among men in low-income countries. The modifying effects of smoking and work-related physical activity on the relationship between SES and obesity have been mentioned; however, none would explain the relationship adequately as to men [21]. Further investigation is needed to explore the mechanisms behind the effects of socioeconomic development on that relationship.

Moreover, findings of the present study show that the relationship between SES and obesity in the elderly resembles that in adulthood. Previous studies in children also showed that, in developed countries, obesity was more prevalent in lower-income people, but in developing countries it was more common in higher-income people [22]. On the other hand, as SES changes during life, risk of obesity changes accordingly [23]. These findings show that the association of SES and obesity seen in adulthood is generalizable to other age groups, such as children and the elderly, just as we found with the elderly in the present study.

Another point in the relationship between SES and obesity is that the direction of relationship depends on the type of SES indicator. Dinsa et al. [21] found that income and wealth were directly associated with obesity in developing countries; however, the association between education and obesity was inverse or non-significant. This finding was consistent among men and women [21]. In the present study, we found that there was a direct, statistically significant association between obesity and assets and also obesity and education among women. The association for income and employment was not statistically significant. There was not, however, any significant association between SES indicators and obesity among men. It seems that there are many complexities in the relationship between SES and obesity that makes that dynamic so difficult to interpret. For example: Aitsi-Selmi et al. [24] found that education modifies the association of wealth and obesity in middle-income countries [25]. Understanding obesogenic mechanisms of SES is necessary in order to interpret the association. It might be necessary to put more emphasis on the social aspects of obesity that cause the attitudes of educated women in developing countries to resemble those of women in developed countries, under the influence of globalization [9, 19]. On the other hand, as societies develop, technological changes push the relationship between SES and obesity from a direct association toward a reverse relationship [19, 20]. However, these changes occur differently according to time, level of development, and other factors such as sex and age. The intermediate pattern observed among men might be a reflection of this changing, dynamic, complex phenomenon.

Exploring the relationship between SES and overweight, as well as obesity, might help us to better understand the mechanism behind this relationship and the resulting inequalities. The findings of the present study showed that there was a direct association between SES and overweight among both men and women. It might be said that as societies develop, the pattern of the relationship between SES and obesity changes more quickly than that between SES and overweight. In other words, overweight is more resistant to the modifying factors. Therefore, any change in the direction of overweight’s relationship with SES would occur at later stages of development. However, few studies have investigated the relationship between SES and overweight.

Finally, the inequality of both overweight and obesity was concentrated in higher SES groups. This is consistent with findings of Alaba and Chola’s study [26] in South Africa that reported a positive, relatively small (particularly for women) Concentration Index for obesity. The Concentration Index observed in the present study was relatively small as well. Concentration Indices for obesity and overweight reported from other studies, mostly from developed countries, were not so large; however, they were mostly negative [27–32].

Strength and limitations

This is the largest population-based study which has investigated the health of the elderly in Iran. Moreover, measurement of various indicators including assets, income, education, and employment enabled us to more reliably assess socioeconomic level of participants and compare the results. Exact measurement of weight and height in a randomly selected sample with a high response rate (>90%) enabled us to estimate the prevalence of obesity and overweight in various SES groups by age group and gender.

However, as health status in the elderly is highly affected by SES during early life and adulthood, it would be highly informative if we had that SES information. Moreover, because there are recall problems among the elderly, and literacy rates were relatively low, especially among women, there might be some limitations on the validity of answers to some questions (e.g., those for income level, education, and household assets). Both limitations can cause non-differential misclassification of participants into SES groups and introduce an information bias towards the null. However, a very high correlation between various SES variables would guarantee an acceptable reliability.

Conclusion

Results of the present study support the direct relationship between SES and obesity previously reported in developing countries. However, this study was conducted on elderly people, while many others had been conducted on adults and children. Developing countries, like Iran, should note that as they develop, the concentration of inequality in obesity will move to the poorer people who are the most vulnerable group in the society. Socioeconomic interventions seem necessary to mitigate that inequality and its potential adverse effects.

Acknowledgements

Authors of this article would like to thank all of the staff of medical research centers at BPUMS and TUMS for their commitment and cooperation. We also thank all people who participated in this study.

Funding

Funding for BEH Programmed was jointly provided by the Persian Gulf Biomedical Sciences Research Institute affiliated with Bushehr (Port) University of Medical Sciences (BPUMS) and the Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute, affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS). Researchers from both research centers have contributed in design and conduction of this research project.

Availability of data and materials

A large amount of data has been collected for this study. The datasets on which the conclusions of this manuscript rely to is available. Interested researchers may access to the data via corresponding author AO (a.ostovar@bpums.ac.ir) or IN (inabipour@gmail.com).

Authors’ contributions

AO conceived the study and performed data analysis and interpretation. AR drafted the manuscript and participated in the data collection, study design and conduction. MM and RH helped draft the manuscript, participated in the study design and conduction, data analysis and interpretation. IN, BL and NM participated in the study design and interpretation of the findings. HD, FS and GS participated in the study design, data collection and analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript.

Competing interests

Authors of this manuscript declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics approval has been obtained from Ethics Committee of Bushehr University of Medical Sciences with the ethical committee reference number of B-91–14-2. A written informed consent has been obtained from each participant of this study as well.

Abbreviations

- BEH

Bushehr Elderly Health

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- DALLY

Disability Adjusted Life Years

- PCA

Principal Component Analysis

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SES

Socioeconomic Status

- WHO

World Health Organization

- YLL

Years of Life Lost

Contributor Information

Alireza Raeisi, Email: Darman719@yahoo.com.

Mohammadbagher Mehboudi, Email: mbmehboudi@gmail.com.

Hossein Darabi, Email: darabi53@yahoo.com.

Iraj Nabipour, Email: inabipour@gmail.com.

Bagher Larijani, Email: larijanib@tums.ac.ir.

Neda Mehrdad, Email: nmehrdad@tums.ac.ir.

Ramin Heshmat, Email: rheshmat@tums.ac.ir.

Gita Shafiee, Email: g-shafiee@farabi.tums.ac.ir.

Farshad Sharifi, Email: farshad.sharifi@gmail.com.

Afshin Ostovar, Phone: +98 771 4550178, Email: a.ostovar@bpums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.WHO. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

- 2.WHO . Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;348(9945):766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su D, Hu R, Fang L, Zhang J, Wang H, He Q, et al. The association between socioeconomic status and blood pressure control in diagnosed hypertension patients. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2015;49(5):424–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(9):647–52. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.9.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oakes JM, Kaufman JS. Methods in social epidemiology. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moser C, Felton A. The construction of an asset index measuring asset accumulation in Ecuador, in Chronic poverty research centre working paper, Global Economy and Development. Washington DC: The Brookings Institution; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Beydoun M. The obesity epidemic in the United States—gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobal J, Stunkard AJ. Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989;105(2):260–75. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens G, Singh G, Lu Y, Danaei G, Lin J, Finucane M, et al. National, regional, and global trends in adult overweight and obesity prevalences. Popul Health Metrics. 2012;10(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soon H. Pattern of dietary behaviour and obesity in Ahwaz, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7(1–2):163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danaei G, Singh G, Paciorek C, Lin J, Cowan M, Finucane M, et al. The global cardiovascular risk transition: Associations of four metabolic risk factors with national income, urbanization, and western diet in 1980 and 2008. Circulation. 2013;127(14):1493–1502. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris DC. Global inequality in kidney care. Med J Aust. 2015;202(5):227–8. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostovar A, Nabipour I, Larijani B, Heshmat R, Darabi H, Vahdat K, et al. Bushehr Elderly Health (BEH) Programme, phase I (cardiovascular system) BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009597. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Donnell O, EV Doorslaer, A Wagstaff, Lindelow M. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data, A Guide to Techniques and Their Implementation. WBI Learning Resources Series. Washington, D.C: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2008.

- 16.Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(6):459–468. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1171–80. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteiro CA, Moura EC, Conde WL, Popkin BM. Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: a review. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(12):940–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:29–48. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philipson TJ, Posner RA. The long-run growth in obesity as a function of technological change. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(3):S87–107. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinsa GD, Goryakin Y, Fumagalli E, Suhrcke M. Obesity and socioeconomic status in developing countries: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012;13(11):1067–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cameron AJ, Spence AC, Laws R, Hesketh KD, Lioret S, Campbell KJ. A Review of the Relationship Between Socioeconomic Position and the Early-Life Predictors of Obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(3):350–62. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu H, Guoa G. Lifetime Socioeconomic Status, Historical Context, and Genetic Inheritance in Shaping Body Mass in Middle and Late Adulthood. Am Sociol Rev. 2015;80(4):705–737. doi: 10.1177/0003122415590627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aitsi-Selmi A, Chandola T, Friel S, Nouraei R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG. Interaction between education and household wealth on the risk of obesity in women in Egypt. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aitsi-Selmi A, Bell R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG. Education modifies the association of wealth with obesity in women in middle-income but not low-income countries: an interaction study using seven national datasets, 2005–2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alaba O, Chola L. Socioeconomic inequalities in adult obesity prevalence in South Africa: a decomposition analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(3):3387–406. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110303387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke PM, Hayes AJ. Measuring achievement: changes in risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(3):552–61. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ljungvall A, Gerdtham UG. More equal but heavier: a longitudinal analysis of income-related obesity inequalities in an adult Swedish cohort. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(2):221–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajizadeh M, Campbell MK, Sarma S. Socioeconomic inequalities in adult obesity risk in Canada: trends and decomposition analyses. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(2):203–21. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Using concentration index to study changes in socio-economic inequality of overweight among US adolescents between 1971 and 2002. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(4):916–25. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh B, Cullinan J. Decomposing socioeconomic inequalities in childhood obesity: evidence from Ireland. Econ Hum Biol. 2015;16:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An R. Educational disparity in obesity among U.S. adults, 1984–2013. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(9):637–642.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

A large amount of data has been collected for this study. The datasets on which the conclusions of this manuscript rely to is available. Interested researchers may access to the data via corresponding author AO (a.ostovar@bpums.ac.ir) or IN (inabipour@gmail.com).