Abstract

The number of survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is expected to dramatically increase over the next decade. Significant and unique challenges confront survivors for decades after their underlying indication (malignancy or marrow failure) has been cured by HCT. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Late Effects Consensus Conference in June 2016 brought together international experts in the field to plan the next phase of survivorship efforts. Working groups laid out the roadmap for collaborative research and health care delivery. Potentially lethal late effects (cardiac/vascular, subsequent neoplasms, and infectious), patient-centered outcomes, health care delivery, and research methodology are highlighted here. Important recommendations from the NIH Consensus Conference provide fresh perspectives for the future. As HCT evolves into a safer and higher-volume procedure, this marks a time for concerted action to ensure that no survivor is left behind.

Keywords: National Institutes of Health, consensus, Late effects, Hematopoietic cell, transplantation, Review, Educational, 2017, Survivorship

INTRODUCTION

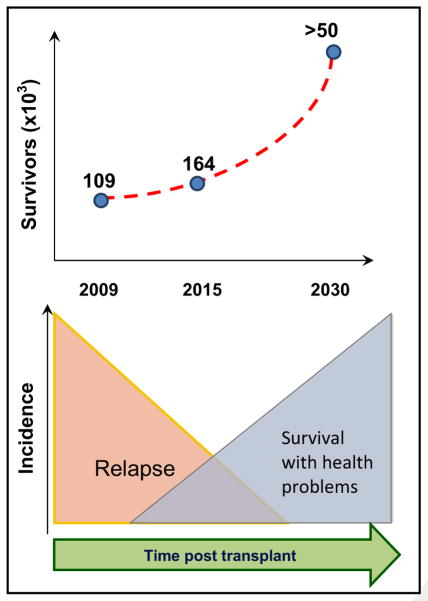

Significant increases in hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) volumes in recent years, surpassing 18,000 in the United States in 2014 alone [1], have been superimposed over steady improvement in early transplantation-related mortality [2,3]. The current population of >100,000 survivors in the United States is projected to increase 5-fold by 2030, with 14% of the population ages <18 years and 25% ages ≥60 years at transplantation [4]. HCT survivors continue to remain at risk for late effects long after the risk of malignancy relapse has abated (Figure 1). Late effect risks vary over time but tracking and management are challenging because they often occur after transition of clinical care away from the transplantation center.

Figure 1.

HCT survivorship. Projected numbers of HCT survivors and temporal course after HCT.

Observational studies in recent years have uncovered much of what we currently understand about late effects in transplantation survivors. The spectrum of late effects impacts multiple domains of health, severity ranges from mild to lethal, the latency of onset can range from months to decades, risk patterns are unique for each late effect and dependent upon the interval after HCT, and pediatric survivors may be more vulnerable. Pathobiology is driven by therapeutic exposure, immune dysregulation, and genetic predisposition. The nature, incidence, and management of late effects have been extensively reviewed [5–10]. Although there is growing appreciation for the lasting impact of late effects, many aspects remain elusive and much further effort is necessary to understand, monitor, and integrate their management into routine survivorship care. Unresolved challenges include health care delivery, understanding the actual pathobiology driving individual late effects, the poor evidence base for screening, prevention and management guidelines in this unique population, and methodological considerations in designing adequately powered studies with biological samples.

To address shortcomings, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored a HCT late effects initiative with the objectives of defining the critical issues or barriers in the field, setting research priorities, creating a successful organizational framework for studying late effects (biology, observational, and interventional studies). The focus was defined as critical survivorship issues occurring >1 year after autologous or allogeneic transplantation that were unique to the field of HCT. Potential areas of overlap with the chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) consensus project [11,12], such as chronic inflammation and pulmonary failure, were avoided. The scope was limited to the most important challenges that would advance the science or change guidelines/clinical care/standard approach [13]. Six broad areas of emphasis were identified, as follows: health care delivery [14]; research methodology and study design [15]; subsequent neoplasms (SN) [16]; quality-of-life and psychosocial outcomes [17]; immune dysregulation [18]; and cardiac, vascular, and metabolic events [19]. Working groups involved international experts, representation of adult and pediatrics, subject matter experts, governmental agencies, advocacy groups, and transplantation societies. Deliberations culminated in a final consensus conference in June 2016. Several important aspects of late complications not specifically covered by the final consensus conference have been the subjects of comprehensive review [7,20].

The purpose of this review is to highlight the fresh perspectives provided by the NIH consensus conference and to summarize their recommendations for a broader audience. This educational review is divided into 3 sections. The first will discuss the magnitude, pathogenesis, management, gaps, and research priorities for late events that are potentially lethal—cardiac, vascular, and metabolic events; SN; and immune dysfunction. The next will focus on patient-centered outcomes and research priorities. The last section will describe health care delivery cost versus value to survivors and unique aspects of research methodology. Table 1 summarizes the key recommendations from the conference [15–19,21].

Table 1.

Overview of Research Priorities Identified by the NIH HCT Late Effects Consensus Conference

| Working Group | HCT Survivorship: Research Gaps and Priorities |

|---|---|

| Cardiac, vascular, and metabolic | Arterial disease

|

Cardiac dysfunction

| |

| SN | CVRF

|

| Immune dysregulation | Late infections

|

Immune reconstitution

| |

| Quality-of-life and psychosocial outcomes | Prevention of infections

|

| Research methodology and study design | |

| Health care delivery | Health care delivery models

|

Coverage and value

|

POTENTIALLY LETHAL LATE EFFECTS

Large retrospective studies confirm that if an allogeneic HCT recipient is alive at 2 years, the recipient is unlikely to relapse but has a 20% probability of delayed mortality over the next 15 to 20 years [22–24]. This delayed nonrelapse mortality (at a rate of 4 to 9 times that of the general population) typically strikes when the recipient has left the influence of the transplantation center. The most frequent causes of delayed mortality are cardiac/vascular, SN, infections, and pulmonary [22,23]. The passage of time should not induce complacency because the standardized mortality ratio at 15 years after HCT remains elevated at 2.2-fold that of the general population [22]. Moreover, it is notable that the incidence for cardiac/vascular and SN continues to increase with time from HCT and does not peak before the completion of the second decade of survivorship. Many causes of delayed mortality are potentially surmountable if we focus research attention on understanding the unique pathobiology of HCT. Improved understanding and awareness of post-HCT physiology will also afford institution of effective early screening methods specific to the HCT population, so that pre-emptive and targeted therapies can be developed.

Magnitude of Impact, Pathogenesis, and Management

Cardiac/vascular/metabolic

It is useful to categorize 3 groups of cardiovascular complications: cardiac dysfunction, arterial disease, and metabolic risk factors. HCT survivors are at a ~4-fold higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared with the general population [25], which tends to occur prematurely, with the first event such as myocardial infarction occurring ~14 years earlier than in the general population, which suggests accelerated cardiovascular aging.

The pathogenesis of elevated CVD risk has been attributed to multiple factors, including pre-HCT therapeutic exposures (eg, anthracycline chemotherapy, chest radiation), HCT conditioning, GVHD, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs); eg, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, sarcopenic obesity, endocrinopathy [26,27]. Endothelial damage and growth hormone deficiency are potential emerging CVD risk factors after HCT [19]. Prospective studies examining the influence of these risk factors are needed.

Current management guidelines emphasize early screening for CVRFs and high-risk lifestyle behaviors to provide opportunity for pre-emptive management of arterial disease [5,6,28,29]. While there is general consensus that screening should begin by 1 year after HCT, existing guidelines have been extrapolated from the general population and probably underestimate the risk of coronary artery disease [5,6,30,31]. The optimal initiation, frequency, and duration of screening methodologies remain undefined. Screening for asymptomatic vascular disease using imaging studies (eg, coronary artery calcium scoring, vascular intima-media thickness), or blood biomarkers of endothelial injury remains an active area of investigation [19]. Outcome after post-HCT heart failure is poor, with <50% surviving 5 years [32,33], emphasizing the need for preventive strategies. Echocardiography has been advocated for screening of asymptomatic cardiac disease, but there is little consensus regarding its cost-effectiveness [34].

SN

SN after HCT are categorized into 3 groups: lymphoid malignancies (including post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder [PTLD]), myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML), and solid tumors. Although lymphomas and leukemias develop relatively early after transplantation, solid tumors tend to have a longer latency, measurable in decades [35–38]. Significant methodological challenges make it difficult to provide accurate estimates of risk for each tumor type compared with the general population [16] but some generalizations can be made. Overall, the risk of subsequent solid tumors has been reported to be more than 2-fold the expected rate in the general population and there is a strikingly high incidence of skin malignancies [39]. A unique aspect of hematologic SN in allogeneic HCT recipients is that they need to be distinguished from recurrence and SN of donor-cell origin [40]. In patients with relevant risk factors, up to 30 times higher risks of PTLD have been reported [41,42]. MDS/AML risk is related to cumulative therapeutic exposure and is a late effect more likely to be encountered after autologous HCT [43].

Outcomes for PTLD [44] and therapy-related MDS/AML [43,45,46] reflect their aggressive biology. For solid tumors, outcomes after allogeneic are variable, with poorer prognosis for female reproductive, bone and joint, lower gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system tumors but with comparable outcomes for thyroid, testis, breast, oral cavity, soft tissue tumors, and melanoma [47].

The pathobiologic drivers for SN have implicated therapeutic chemotherapy and radiation exposure, the unique immunologic milieu after HCT, immunosuppression, and oncogenic virus reactivation (Epstein Barr virus, human papilloma virus). Pediatric survivors seem particularly vulnerable, with a higher risk of SN in younger recipients exposed to total body irradiation [37,48]. Chronic GVHD (and associated immunosuppressive therapy) has been consistently associated with a 2-fold to 3-fold higher rate of overall SN than in the general population [49]. Donor-cell origin SN is a fascinating phenomenon that has been associated with extreme telomere erosion after graft expansion [50,51]. There are insufficient data to conclusively determine the impact of histo-incompatibility (HLA mismatch), allogeneic donor graft source, and T cell depletion on SN. Fertile areas for pathobiologic research include the mechanisms underlying viral mutagenesis, factors that control the development of T large granular lymphocytes, changes in the recipient milieu and tissue niches, and characterizing the impact of donor cells promoting SN [16].

Pediatric and adult management guidelines for HCT survivors emphasize a healthy lifestyle; sun avoidance; and regular dental, gynecologic, and dermatologic follow-up along with age- and gender- appropriate primary care screening for malignancy [52,53]. There are limited data on the effectiveness of screening approaches. No specific therapeutic recommendations and SN outcomes after HCT appear to be generally inferior compared with the general population [54–56].

Immune dysregulation

The risk of infectious mortality does decline over time. However, there is growing awareness that lethal infections in the absence of GVHD may occur very late after HCT [22–24,57,58]. A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation and Research (CIBMTR) study of >10,000 2-year HCT survivors with a median follow-up of 9 years estimated that 10% to 20% of all deaths were caused by infection in the absence of active GVHD [24]. Unfortunately, these retrospective analyses are limited with respect to the pathogens responsible, risk factors, and the influence of prolonged prior immunosuppression/GVHD.

The pathogenesis of late infection is related to dysregulated immune reconstitution. Optimal immune reconstitution has been operationally defined as the restoration of functional pathogen-specific immunity and establishment of anticancer immunity without dysregulation by GVHD and/or HCT-associated autoimmunity [18]. Factors influencing immune reconstitution include age, underlying disease, immunosuppressive state, prior infections, conditioning regimen, donor type, degree of match, stem cell source, immunosuppression, anti-infective practice, GVHD, viral infections, and therapies to prevent relapse [59–63]. GVHD, cytomegalovirus infection, or HLA-mismatched transplantations are more likely to have delayed, incomplete, or dysregulated immune reconstitution [64–67]. Functional asplenia predisposes to fulminant S. pneumoniae sepsis in subjects with prior GVHD [66]. Persistently low CD4 counts or immunoglobulin levels have been associated with late infectious morbidity [57,68]. Immunologic deficits are detectable using sensitive immunologic assays even beyond 10 years [69,70]. In 1 study, two-thirds of infectious deaths were due to pneumonia, and a pathogen was detectable in 57%, with Aspergillus and cytomegalovirus being the 2 prominent causes [67].

The management of late infection is essentially prevention with antimicrobial prophylaxis, vaccination approaches, and immunoglobulin (IVIG). Revaccination after HCT is an important aspect of survivorship care. Guidelines recommend the administration of killed-organism vaccines as early as 3 to 6 months after transplantation [58,71] but there is considerable variation in schedule implementation [72]. Passive transfer of immunity with IVIG provides short-term protection against infection with a repletion threshold commonly set at <400 mg/dL [73]. However, evidence for the benefits of IVIG is weak, overuse may impair long-term humoral recovery after bone marrow transplantation [74], and studies of its use late after HCT have not been conducted.

Gaps and Priorities for Research

Cardiac/vascular/metabolic

Several intriguing issues surround the increased risk of CVD in HCT survivors. Postulated underlying pathogenic mechanisms include GVHD, pre-HCT and post-HCT therapeutic exposure (chemotherapy, radiation, and immunosuppressive drugs), endothelial dysfunction, and growth hormone deficiency; however, their relative contributions are undefined [19]. Almost all known CVRFs (dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, renal dysfunction, other endocrinopathy) are elevated in HCT recipients compared with in the general population. There is a pronounced allogeneic effect for vascular and metabolic consequences [75]. The role of chronic GVHD is controversial for the allogeneic effect and may not be the only explanation. Conventional models of vascular risk extrapolated from the general population, such as the Framingham risk score, underestimate the true risk of arterial disease and is emblematic of the issues surrounding screening strategies. Sensitive screening techniques before the occurrence of irreversible damage are probably necessary in high-risk subsets of this vulnerable population. Intervention approaches need to be developed around validated screening strategies to target the most vulnerable recipients. Specific studies aimed at understanding and preventing arterial disease and cardiac dysfunction (heart failure, valvular disease, and arrhythmias), as well as decreasing CVRFs (hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and sarcopenic obesity) after HCT [19].

SN

The greatest challenge is to conduct the kind of large scale, long-term prospective studies that will provide definitive information on the magnitude of risk for diverse SN subtypes, risk factors, and mechanisms of pathogenesis and to optimize preventative, screening, and therapeutic approaches. This will need to be coupled with banking of cryopreserved donor and recipient blood or marrow cells and SN tissues with detailed clinical data. Resources that support longitudinal biomarker studies will be critical [16].

Immune dysregulation

Existing data have identified late infections as a significant lethal complication [22–24]. However, the nature of the pathogens, the relationship to the extent of immune reconstitution, vaccine preventability, and risk factors are largely unknown. To address delayed infectious mortality, it is critical to understand the pathogens responsible, the risk factors, and immunologic correlates. A long-term, multicenter, prospective study with samples collected for immunologic testing has been identified as a critical priority [18]. Such a study will also allow, as an adjunct, the measurement of microbiota changes after HCT and the association of such changes with late infections and immunity. Refinement of current infection control guidelines will require a registry of vaccine-preventable and other rare infectious diseases (eg, late aspergillosis or pneumocystis pneumonia).

PATIENT-REPORTED CONCERNS: PSYCHOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL LONG-TERM EFFECTS

Patients with chronic illness may present considerable mental strain, interfering with health condition, subjective well-being, and social outcomes. Long-term HCT survivors, although not usually considered as patients with “chronic illness,” are susceptible to late complications [76,77] and are, therefore, at risk for considerable long-term psychological distress, which may impact their outcomes negatively. Health status evaluation includes an appraisal of the psychosocial state together with the assessment of their physical impairment. The clinical condition of HCT survivors may not necessarily correspond with the patient’s concerns; indeed the most frequent subjective complaints in long-term survivors include fatigue, eye discomfort, musculoskeletal problems, cognitive impairment, sexual dysfunction, emotional distress, and depression [7]. This part of the review discusses the relevance of psychological distress, the risk of suicide and accidents, as well as social outcomes in long-term HCT survivors.

Psychological Distress and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Psychological distress is a state of emotional suffering characterized by symptoms of depression and anxiety that may impact the day-to-day living of an individual [78,79]. It is considered to be a transient phenomenon triggered by external stressors, rather than a psychiatric illness. In the general population, socio-demographic factors related with psychological distress are gender, age, ethnicity, and social discrimination (eg, minorities). Stressors that may provoke psychological distress are cancer and chronic illness, family-related conflicts and divorce, work-related conflicts, sexual dysfunction, infertility, and financial strain [80,81]. In a National Health Interview Survey from the United States, overall 3% of a civilian population ages 18 to 64 had serious psychological distress [82]. Women and persons with chronic illness were more at risk [82]. With increased income, the percentage of serious psychological discomfort decreased [82,83]. Interestingly, all stressors relevant in a general population may be enhanced in HCT survivors [82].

Adverse psychological outcomes have been evaluated in 1065 long-term HCT survivors [84]. Compared with healthy siblings, survivors were more likely to report anxiety, depression, and somatization. Twenty-two percent of HCT survivors reported psychological distress, compared with 8% of healthy siblings. Interestingly, after adjustment for socio-demographic variables such as age, sex, race, education, income, insurance, and self-reported heath status, there was no longer a statistical difference. This means that the same factors are involved in long-term survivors as in healthy siblings; however, some of these factors (education, low income, insurance, and self-reported health status) might have a stronger impact in long-term survivors [84]. Similar to the general population, the main risk factors for psychological distress were low income and poor self-reported health, but unique HCT factors were steroids and chronic GVHD.

In a prospective longitudinal cohort study, 319 HCT patients were assessed before transplantation, at day 90, and at 1, 3, and 5 years after HCT. At some point, 22% of all patients had symptoms of depression. Physical improvement occurred earlier than psychological and work recovery. Chronic GVHD as well as social isolation were contributing factors for post-transplantation psychological distress [85].

People exposed to a terrifying traumatic event are at increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), leading to symptoms including flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event [86]. PTSD is increasingly reported after HCT [87]. In a prospective study on 239 patients treated with allogeneic HCT, up to 15% fulfilled criteria of PTSD at least once during the assessments, performed before HCT, as well as on day 100 and 12 months after HCT. Burden of pain, being female, and medical complications were the main risk factors [88]. Parents of children undergoing HCT also report traumatic thoughts. However, a large number of these parents later experience post-traumatic growth that is, interestingly, proportionate to the level of post-traumatic stress [89].

Suicides and Accidents

Suicide is a rare event after HCT; however, when it occurs, it is a catastrophic event for the family as well as the care team. Suicidal ideation is more often reported in long-term survivors, compared with healthy siblings, particularly in patients with low income. Anxiety, depression, and somatization were all associated with suicidal ideation [84]. In a study on severe chronic GVHD after HCT with nonmyeloablative conditioning, 5% of the patients needed hospitalization because of suicidal ideation related to their GVHD [90]. In a large population-based cohort study, the cumulative incidence at 10 years for suicide deaths increased up to 100 per 100,000 patients for both allogeneic and autologous HCT recipients [91]. The standard mortality rate and the absolute excess rate of death by suicide were higher with 2.12 (95% confidence interval, 1.83 to 2.45) and 20.91, respectively, compared with the general population. Despite similar cumulative incidences for suicide after allogeneic and autologous HCT, the risk factors differed. Relapse after autologous and chronic GVHD after allogeneic HCT was associated with more suicide deaths. HCT survivors are also at increased risk for accidents. Deficits in both physical and mental health have been shown to be risk factors for accidental deaths in a cancer population [92,93]. After HCT, ocular problems, cardiovascular complications, cognitive impairment, or depression (hidden suicide) might be involved.

Return to Work and Social Late Effects

Return to work or equivalent is ultimately an important goal for recipients of HCT. Moreover, employment after HCT is a good indicator for significant health recovery after transplantation. On the other hand, unemployment after HCT may contribute to financial strain and psychosocial late effects. In the general population, the prevalence of anxiety and depression has been shown to be consistently associated with unemployment and poverty [94].

There are various reasons for inability to return to work after transplantation. Both physical and mental late effects may impede return to normal social life. Return to work ranges between 54% and 74%, depending on time since HCT and the population at risk. A proportion of patients who return to work are not able to obtain full-time employment. Occupational status in 177 long-term survivors showed that 52% were working full-time, 27% were working part-time, and 17% were on sick leave, disability pension, or old-age pension [95]. Not working at all or working part-time was related with poor health status, older age at transplantation, being a woman, and being born abroad. In a longitudinal life style survey of 1000 patients from United States who had undergone autologous or allogeneic HCT, survivors unemployed because of health problems were more likely to report fatigue and pain and had poorer quality of life [96]. On the other hand, better physical functioning by 6 months after transplantation predicted return to work after HCT [97].

Unemployment in long-term survivors may be related to lower income and the need for work disability pension. In a cohort of long-term patients (≥5 years after HCT), the need for disability pension increased up to 37%, which was significantly higher than what is expected in the age-matched general population (3.8%). Older age at HCT and at study time, living alone, poor physical or mental health condition, and fatigue were possible determinants predicting need of social and financial support [98]. The need of disability pension may have an impact on the patient’s outcome. In a population-based study from Sweden, mortality was higher for individuals with than without disability pension, in males and females of all age groups [99].

Recipients of allogeneic HCT experience substantial financial burden. Despite insurance coverage, out-of-pocket costs, medical copayment, travel costs to the center, and unemployment may contribute to financial difficulties after HCT. The financial burden may increase when additionally the caregiver, who previously was sharing the family income, has loss of income due to missed work and increased out-of-pocket expenses [100]. In a questionnaire-based study of 268 survivors of HCT, 73% reported that their sickness had hurt them financially. Of the responders, 47% experienced a decrease of household income >50%, selling/mortgaging home, or withdrawing money from retirement accounts [101,102]. Financial difficulties do not seem to decrease with longer survival since HCT. Greater financial and employment stress may reduce physical and mental well-being of HCT survivors [103].

Conclusions

Physical complications and psychological distress are closely related in long-term HCT survivors. A multidisciplinary management approach involving physical and psychological support is therefore indicated. Screening for psychological distress can be easily integrated into routine care of HCT survivors [104]. The difficulty in resuming gainful employment may lead survivors to financial strain; these survivors are particularly vulnerable for poor psychological outcome. Adequate social support should therefore be an integral part of post-transplant survivorship care.

At the Late Effects Consensus Conference conducted by the NIH in 2016, 1 of the issues addressed was health-related quality of life [17]. Based on the current literature in this field, the working group on quality-of-life and psychosocial outcomes described the state of knowledge of physical, psychological, social, and financial late effects, as well as adherence to medication and health behavior in long-term HCT survivors. The working group further addressed the methodological difficulties in this field of research and identified the actual gaps of knowledge. This comprehensive work on patient-centered outcomes could represent the basis for recommendations on the care of long-term survivors and defines priorities of future research in health-related quality-of-life issues.

HCT SURVIVORSHIP: RESEARCH METHODS AND CARE DELIVERY

The number of HCT survivors continues to progressively increase over time and lifelong follow-up for screening and prevention of post-transplantation late effects is recommended [4,5,105]. However, considerable research is still needed to define the risk factors and prevention and management of transplantation-related late complications. Two working groups within the NIH Blood and Marrow Transplant Late Effects Consensus Conference addressed issues specific to research methodology [15] and care delivery for HCT survivors [21].

HCT Survivorship: Research Methodology

Despite robust institutional databases and observational registries (eg, CIBMTR), research on HCT survivors poses challenges because of changing trends in the practice of transplantation, lack of adequate data on pretransplantation exposures, the low incidence and long latency of late effects, and incomplete information on follow-up and late complications. The pathogenesis of most late effects remains largely unknown. Additionally, heterogeneity of patient populations and exposures, competing endpoints, and missing data present analytic challenges.

To better understand the incidence, risk factors, and pathogenesis of late effects after transplantation, there is a critical need to establish new cohorts or expand existing cohorts that capture comprehensive and complete follow-up of HCT recipients. Ideally, this will be accompanied by detailed data on pretransplantation and post-transplantation exposures, chronic GVHD, patient-reported outcomes, and health care costs. Investment in information technology solutions to enhance the efficiency of data capture and sharing will facilitate this research. High priority areas include late effects with high incidence of morbidity and mortality, higher risks than the general population, and modifiable risk factors. Bio repositories with pre- and post-HCT patient and donor specimens, as well as fresh frozen tissue in patients with SN, will facilitate investigations using existing and future technologies. With the exception of quality of life, patient-reported outcomes have not been thoroughly investigated in HCT survivors, and studies will enhance our understanding of their application in this population. Thus, to address research questions around late effects, there is an immediate need for initiatives that leverage sharing between existing data and sample sources along with the evaluation of innovative study designs and analytic methods specific to HCT survivors.

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY FOR HCT SURVIVORS

Health Care Delivery Models

The health care needs of HCT survivors are best addressed through patient-centered health delivery models that take into account transplantation-related issues [106]. Hence, care needs to be responsive to patient health care needs and preferences, closely coordinated between the referring and transplantation center clinical providers, account for variability of resources and personnel available among institutions, and adaptable to changes in patient status (eg, presence of chronic GVHD or other HCT-related complications). At the same time, several barriers to providing comprehensive and coordinated care exist at the patient, caregiver, provider, and institutional level. Lack of high-quality evidence and clinical trials, operational barriers, and inadequate payment models also limit HCT survivorship care.

There is no “ideal” care model for HCT survivors and care has to be individualized to patient preferences, health status, and ongoing need for HCT-related care. Models can range from an integrated model where care is provided as part of ongoing follow-up at the transplantation center to a transitional care model, where the patient is transitioned to a nontransplantation provider at a certain time point [107,108]. Regardless, care needs to address patient health maintenance, health promotion and education, surveillance for disease recurrence and for late complications, screening for SN, psychosocial support, rehabilitation and reintegration into society, financial counseling, and patient and caregiver quality of life.

Research is critically needed for the development and validation of HCT-specific care models. This can be best facilitated by establishment of data and research infrastructure such as leveraging existing registries or multi-institutional trial mechanisms (eg, CIBMTR, Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network), databases at transplantation centers, and accessibility to large secondary administrative databases. Systematic evaluation of the generation, delivery, and implementation of treatment summary and survivorship care plans is needed. Other areas of research include role of supportive therapies, rehabilitation and reintegration of survivors, and survivorship issues faced by caregivers and families. Better understanding of the impact of health care disparities in provision and utilization of HCT survivorship care is also needed.

Coverage and Value

Survivorship care needs to be value based where it offers the most optimal outcomes and quality of life to the patient at the lowest possible cost [109]. Hence, health care coverage is an important aspect of HCT survivorship [110]. The fee-for-service payment model has been used traditionally, but is not well suited for coverage of survivorship care given lack of incentives for providing preventive care and care coordination. There exists considerable interest in evaluating alternative payment models such as pay-for-performance, bundled payments, and patient-centered medical home. These mechanisms are promising, but individually, they have several limitations in application to HCT survivorship care, where outcomes and metrics for payment are not well defined and patients frequently have an unpredictable clinical course and can transition from 1 site or phase of care to another. Ultimately integrated or hybrid models for coverage of HCT survivorship are needed that consider the need for significant face-to-face time and care coordination, complex chronic disease care, involvement of range of clinical providers and specialists, coverage of preventive and treatment services, transition from 1 phase and place of care to another, and coverage of patient out-of-pocket expenditures [111].

To inform research and policy on coverage for HCT survivorship, databases that can be linked at the patient level and provide detailed patient characteristics, outcomes, patient-reported outcomes, costs, and resource utilization are urgently needed. Research is needed to understand the impact, risk factors, and interventions for financial toxicity in HCT survivors. Cost-effectiveness analyses comparing nontransplantation therapies with transplantation and among different modalities of transplantation are needed to better define the value of this procedure for specific diseases. Validated patient-reported outcomes measures that can inform research on costs and value in HCT are generally lacking and need to be developed. Clinical trials need to routinely include endpoints that inform coverage and value.

Conclusion

Improving early outcomes along with growing awareness of the impact of late complications on HCT survivors has mandated a comprehensive reappraisal of late effects. The NIH HCT Late Effects Initiative has identified priority areas for future effort. Opportunities abound for the prospect of further improving survival by addressing the potentially lethal late effects (cardiovascular, SN, and immune dysregulation) and key metrics of quality of life for HCT survivors in an optimized health care delivery model.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Upneet Chawla for editorial assistance and Alicia Rovo for critical reading of and helpful comments on the manuscript.

Financial disclosure: This research was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, NHLBI, NIH.

Conflict of interest statement: The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the NIH or the United States Government. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Pasquini MC, Zhu X. Current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR Summary Slides. 2015. Vol 20162015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn T, McCarthy PL, Jr, Hassebroek A, et al. Significant improvement in survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation during a period of significantly increased use, older recipient age, and use of unrelated donors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2437–2449. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy PL, Jr, Hahn T, Hassebroek A, et al. Trends in use of and survival after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in North America, 1995–2005: significant improvement in survival for lymphoma and myeloma during a period of increasing recipient age. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1116–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Majhail NS, Tao L, Bredeson C, et al. Prevalence of hematopoietic cell transplant survivors in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1498–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Lee SJ, et al. Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:348–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.12.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savani BN, Griffith ML, Jagasia S, Lee SJ. How I treat late effects in adults after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3002–3009. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-263095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syrjala KL, Martin PJ, Lee SJ. Delivering care to long-term adult survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3746–3751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark CA, Savani M, Mohty M, Savani BN. What do we need to know about allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:1025–1031. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majhail NS, Rizzo JD. Surviving the cure: long term followup of hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:1145–1151. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tichelli A, Rovo A. Survivorship after allogeneic transplantation-management recommendations for the primary care provider. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10:35–44. doi: 10.1007/s11899-014-0243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavletic SZ, Lee SJ, Socie G, Vogelsang G. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: implications of the National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:645–651. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavletic SZ, Vogelsang GB, Lee SJ. 2014 National Institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: preface to the series. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:387–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Battiwalla M, Hashmi S, Majhail N, Pavletic S, Savani BN, Shelburne N. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: developing recommendations to improve survivorship and long-term outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.10.020.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashmi SK, Bredeson C, Duarte RF, et al. National Institutes of Health Blood and Marrow Transplant Late Effects Initiative: the Healthcare Delivery Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.025.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw BE, Hahn T, Martin PJ, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: the Research Methodology and Study Design Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.08.018.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton LM, Saber W, Baker KS, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: consensus recommendations for subsequent neoplasms. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.005.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bevans M, El-Jawahri A, Tierney DK, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: consensus recommendations for patient-centered outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.011.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gea-Banacloche J, Komanduri K, Carpenter P, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: consensus recommendations for immune dysregulation and pathobiology. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armenian SH, Chemaitilly W, Chen M, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: the Cardiovascular Disease and Associated Risk Factors Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.08.019.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shanis D, Merideth M, Pulanic TK, Savani BN, Battiwalla M, Stratton P. Female long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: evaluation and management. Semin Hematol. 2012;49:83–93. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashmi SK, Bredeson C, Duarte RF, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: consensus recommendations for healthcare delivery. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatia S, Francisco L, Carter A, et al. Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2007;110:3784–3792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin PJ, Counts GW, Jr, Appelbaum FR, et al. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1011–1016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2230–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chow EJ, Mueller BA, Baker KS, et al. Cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality among recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:21–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-1-201107050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armenian SH, Chow EJ. Cardiovascular disease in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancer. 2014;120:469–479. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rovo A, Tichelli A, Marrow T Late Effects Working Party of the European Group for B. Cardiovascular complications in long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Semin Hematol. 2012;49:25–34. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passweg JR, Halter J, Bucher C, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review and recommendations for follow-up care for the general practitioner. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13696. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffith ML, Savani BN, Boord JB. Dyslipidemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: evaluation and management. Blood. 2011;116:1197–1204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nieder ML, McDonald GB, Kida A, et al. National Cancer Institute-National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute/Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium First International Consensus Conference on Late Effects after Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: long-term organ damage and dysfunction. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1573–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain NA, Chen MY, Shanbhag S, et al. Contrast enhanced cardiac CT reveals coronary artery disease in 45% of asymptomatic allo-SCT long-term survivors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:451–452. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armenian SH, Sun CL, Shannon T, et al. Incidence and predictors of congestive heart failure after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:6023–6029. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-358226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armenian SH, Sun CL, Francisco L, et al. Late congestive heart failure after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5537–5543. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thavendiranathan P, Grant AD, Negishi T, Plana JC, Popovic ZB, Marwick TH. Reproducibility of echocardiographic techniques for sequential assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and volumes: application to patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtis RE, Metayer C, Rizzo JD, et al. Impact of chronic GVHD therapy on the development of squamous-cell cancers after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: an international case-control study. Blood. 2005;105:3802–3811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, Rizzo JD, et al. Secondary solid cancers after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation using busulfan-cyclophosphamide conditioning. Blood. 2011;117:316–322. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rizzo JD, Curtis RE, Socie G, et al. Solid cancers after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113:1175–1183. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Socie G, Baker KS, Bhatia S. Subsequent malignant neoplasms after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:S139–S150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omland SH, Gniadecki R, Haedersdal M, Helweg-Larsen J, Omland LH. Skin cancer risk in hematopoietic stem-cell transplant recipients compared with background population and renal transplant recipients: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:177–183. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flynn CM, Kaufman DS. Donor cell leukemia: insight into cancer stem cells and the stem cell niche. Blood. 2007;109:2688–2692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-021980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis RE, Travis LB, Rowlings PA, et al. Risk of lymphoproliferative disorders after bone marrow transplantation: a multi-institutional study. Blood. 1999;94:2208–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landgren O, Gilbert ES, Rizzo JD, et al. Risk factors for lymphoproliferative disorders after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113:4992–5001. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-178046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metayer C, Curtis RE, Vose J, et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia after autotransplantation for lymphoma: a multicenter case-control study. Blood. 2003;101:2015–2023. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orazi A, Hromas RA, Neiman RS, et al. Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders in bone marrow transplant recipients are aggressive diseases with a high incidence of adverse histologic and immunobiologic features. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:419–429. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/107.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Howe R, Micallef IN, Inwards DJ, et al. Secondary myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia are significant complications following autologous stem cell transplantation for lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:317–324. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boehm A, Sperr WR, Leitner G, et al. Comorbidity predicts survival in myelodysplastic syndromes or secondary acute myeloid leukaemia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:945–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehrhardt MJ, Brazauskas R, He W, Rizzo JD, Shaw BE. Survival of patients who develop solid tumors following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:83–88. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz JL, Kopecky KJ, Mathes RW, Leisenring WM, Friedman DL, Deeg HJ. Basal cell skin cancer after total-body irradiation and hematopoietic cell transplantation. Radiat Res. 2009;171:155–163. doi: 10.1667/RR1469.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Majhail NS. Secondary cancers following allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation in adults. Br J Haematol. 2011;154:301–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dickson MA, Papadopoulos EB, Hedvat CV, Jhanwar SC, Brentjens RJ. Acute myeloid leukemia arising from a donor derived premalignant hematopoietic clone: a possible mechanism for the origin of leukemia in donor cells. Leuk Res Rep. 2014;3:38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.lrr.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee J, Kook H, Chung I, et al. Telomere length changes in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:411–415. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chow EJ, Anderson L, Baker KS, et al. Late effects surveillance recommendations among survivors of childhood hematopoietic cell transplantation: a Children’s Oncology Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inamoto Y, Shah NN, Savani BN, et al. Secondary solid cancer screening following hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1013–1023. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ashton LJ, Le Marsney RE, Dodds AJ, et al. A population-based cohort study of late mortality in adult autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients in Australia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:937–945. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Socie G, Henry-Amar M, Devergie A, et al. Poor clinical outcome of patients developing malignant solid tumors after bone marrow transplantation for severe aplastic anemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1992;7:419–423. doi: 10.3109/10428199209049797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friedberg JW, Neuberg D, Stone RM, et al. Outcome in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome after autologous bone marrow transplantation for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3128–3135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leather HL, Wingard JR. Infections following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:483–520. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1143–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alsharif M, Cameron SE, Young JA, et al. Time trends in fungal infections as a cause of death in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: an autopsy study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:746–755. doi: 10.1309/AJCPV9DC4HGPANKR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bachanova V, Brunstein CG, Burns LJ, et al. Fewer infections and lower infection-related mortality following non-myeloablative versus myeloablative conditioning for allotransplantation of patients with lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:237–244. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomblyn M, Young JA, Haagenson MD, et al. Decreased infections in recipients of unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation from donors with an activating KIR genotype. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Burik JA, Carter SL, Freifeld AG, et al. Higher risk of cytomegalovirus and aspergillus infections in recipients of T cell-depleted unrelated bone marrow: analysis of infectious complications in patients treated with T cell depletion versus immunosuppressive therapy to prevent graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1487–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young JA, Logan BR, Wu J, et al. Infections after transplantation of bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells from unrelated donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abrahamsen IW, Somme S, Heldal D, Egeland T, Kvale D, Tjonnfjord GE. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: the impact of stem cell source and graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica. 2005;90:86–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Antin JH. Immune reconstitution: the major barrier to successful stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:43–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalhs P, Panzer S, Kletter K, et al. Functional asplenia after bone marrow transplantation. A late complication related to extensive chronic graft-versus-host disease. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:461–464. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-6-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bjorklund A, Aschan J, Labopin M, et al. Risk factors for fatal infectious complications developing late after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Storek J, Gooley T, Witherspoon RP, Sullivan KM, Storb R. Infectious morbidity in long-term survivors of allogeneic marrow transplantation is associated with low CD4 T cell counts. Am J Hematol. 1997;54:131–138. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199702)54:2<131::aid-ajh6>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Le RQ, Melenhorst JJ, Battiwalla M, et al. Evolution of the donor T-cell repertoire in recipients in the second decade after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:5250–5256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Storek J, Joseph A, Espino G, et al. Immunity of patients surviving 20 to 30 years after allogeneic or syngeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:3505–3512. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:309–318. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carpenter PA, Englund JA. How I vaccinate blood and marrow transplant recipients. Blood. 2016;127:2824–2832. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-550475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carpenter PA, Kitko CL, Elad S, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: V. The 2014 Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1167–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sullivan KM, Storek J, Kopecky KJ, et al. A controlled trial of long-term administration of intravenous immunoglobulin to prevent late infection and chronic graft-vs.-host disease after marrow transplantation: clinical outcome and effect on subsequent immune recovery. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1996;2:44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tichelli A, Bucher C, Rovo A, et al. Premature cardiovascular disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;110:3463–3471. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun CL, Kersey JH, Francisco L, et al. Burden of morbidity in 10+ year survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: report from the bone marrow transplantation survivor study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1073–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tichelli A, Rovo A, Socie G. Late effects after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation–critical issues. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2012;43:132–149. doi: 10.1159/000335271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Measurement for a human science. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:152–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Drapeau A, Marchand A, Beaulieu-Prévost D. In: Epidemiology of Psychological Distress, Mental Illnesses—Understanding, Prediction and Control. Labate PL, editor. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Horwitz AV. Distinguishing distress from disorder as psychological outcomes of stressful social arrangements. Health (London) 2007;11:273–289. doi: 10.1177/1363459307077541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ridner SH. Psychological distress: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:536–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weissman JF, Pratt LA, Miller EA, Parker JD. Serious psychological distress among adults: United States, 2009–2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2015:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Orpana HM, Lemyre L, Gravel R. Income and psychological distress: the role of the social environment. Health Rep. 2009;20:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sun CL, Francisco L, Baker KS, Weisdorf DJ, Forman SJ, Bhatia S. Adverse psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) Blood. 2011;118:4723–4731. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Recovery and long-term function after hematopoietic cell transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma. JAMA. 2004;291:2335–2343. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yehuda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:108–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.El-Jawahri AR, Vandusen HB, Traeger LN, et al. Quality of life and mood predict posttraumatic stress disorder after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2016;122:806–812. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Esser P, Kuba K, Scherwath A, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology in the course of allogeneic HSCT: a prospective study. J Cancer Surviv. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0579-7.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Forinder U, Norberg AL. Posttraumatic growth and support among parents whose children have survived stem cell transplantation. J Child Health Care. 2014;18:326–335. doi: 10.1177/1367493513496666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Flowers ME, Traina F, Storer B, et al. Serious graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation following nonmyeloablative conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:277–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tichelli A, Labopin M, Rovo A, et al. Increase of suicide and accidental death after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a cohort study on behalf of the Late Effects Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Cancer. 2013;119:2012–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kendal WS, Kendal WM. Comparative risk factors for accidental and suicidal death in cancer patients. Crisis. 2012;33:325–334. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Loberiza FR, Jr, Cannon AJ. Sounding the alarm on deaths from suicide and accidents after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2013;119:1936–1937. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weich S, Lewis G. Poverty, unemployment, and common mental disorders: population based cohort study. BMJ. 1998;317:115–119. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7151.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Winterling J, Johansson E, Wennman-Larsen A, Petersson LM, Ljungman P, Alexanderson K. Occupational status among adult survivors following allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:836–842. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Morrison EJ, Ehlers SL, Bronars CA, et al. Employment status as an indicator of recovery and function one year after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:1690–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Syrjala KL. Prospective predictors of return to work in the 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0105-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tichelli A, Gerull S, Holbro A, Buser A, Halter J, Passweg J. Inability to return to work and need for work disability pension among long term survivors of HSCT. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:265. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2017.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Karlsson NE, Carstensen JM, Gjesdal S, Alexanderson KA. Mortality in relation to disability pension: findings from a 12-year prospective population-based cohort study in Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35:341–347. doi: 10.1080/14034940601159229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Meehan KR, Fitzmaurice T, Root L, Kimtis E, Patchett L, Hill J. The financial requirements and time commitments of caregivers for autologous stem cell transplant recipients. J Support Oncol. 2006;4:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Khera N, Chang YH, Hashmi S, et al. Financial burden in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim W, McNulty J, Chang YH, et al. Financial burden after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a qualitative analysis from the patient’s perspective. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1259–1261. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hamilton JG, Wu LM, Austin JE, et al. Economic survivorship stress is associated with poor health-related quality of life among distressed survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology. 2013;22:911–921. doi: 10.1002/pon.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hoodin F, Zhao L, Carey J, Levine JE, Kitko C. Impact of psychological screening on routine outpatient care of hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1493–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Lee SJ, et al. Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:337–341. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Majhail NS. Optimizing quality and efficiency of healthcare delivery in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s11899-015-0264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Halpern MT, Viswanathan M, Evans TS, Birken SA, Basch E, Mayer DK. Models of cancer survivorship care: overview and summary of current evidence. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e19–e27. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, Hudson MM. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:804–812. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ramsey S, Schickedanz A. How should we define value in cancer care? Oncologist. 2010;15(suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Preussler JM, Denzen EM, Majhail NS. Costs and cost-effectiveness of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1620–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Maziarz RT, Farnia S, Martin P, Komanduri KV. Optimal benefits for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a consensus opinion. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:1671–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]