Significance

Polycyclic lipids produced by bacteria and eukaryotes can be preserved in sedimentary rocks for millions of years. These ancient lipids can function as “molecular fossils” or biomarkers that can inform us about the types of organisms and environments on early Earth. However, proper interpretation of these biomarkers requires a comprehensive understanding of the taxonomic distribution, biosynthesis, and physiological function of these lipids in modern organisms. In this study, we discover that a marine bacterium produces two arborinols, a class of lipids previously identified only in flowering plants. This discovery addresses a current incongruity in biomarker signatures and also provides insight into the evolution of the biosynthetic pathways of biomarker lipids.

Keywords: triterpene synthase, isoarborinol, sterol, biomarker, natural products

Abstract

Cyclic triterpenoids are a broad class of polycyclic lipids produced by bacteria and eukaryotes. They are biologically relevant for their roles in cellular physiology, including membrane structure and function, and biochemically relevant for their exquisite enzymatic cyclization mechanism. Cyclic triterpenoids are also geobiologically significant as they are readily preserved in sediments and are used as biomarkers for ancient life throughout Earth's history. Isoarborinol is one such triterpenoid whose only known biological sources are certain angiosperms and whose diagenetic derivatives (arboranes) are often used as indicators of terrestrial input into aquatic environments. However, the occurrence of arborane biomarkers in Permian and Triassic sediments, which predates the accepted origin of angiosperms, suggests that microbial sources of these lipids may also exist. In this study, we identify two isoarborinol-like lipids, eudoraenol and adriaticol, produced by the aerobic marine heterotrophic bacterium Eudoraea adriatica. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrates that the E. adriatica eudoraenol synthase is an oxidosqualene cyclase homologous to bacterial lanosterol synthases and distinct from plant triterpenoid synthases. Using an Escherichia coli heterologous sterol expression system, we demonstrate that substitution of four amino acid residues in a bacterial lanosterol synthase enabled synthesis of pentacyclic arborinols in addition to tetracyclic sterols. This variant provides valuable mechanistic insight into triterpenoid synthesis and reveals diagnostic amino acid residues to differentiate between sterol and arborinol synthases in genomic and metagenomic datasets. Our data suggest that there may be additional bacterial arborinol producers in marine and freshwater environments that could expand our understanding of these geologically informative lipids.

Cyclic triterpenoids are a broad class of lipids produced by diverse bacteria and eukaryotes (1). The most studied of these molecules are the tetracyclic sterols (e.g., cholesterol) and their derivatives (e.g., steroid hormones), which are essential in eukaryotes and play critical roles in membrane structure and in cellular signaling (2–4). In addition to sterols, plants synthesize a diverse array of cyclic triterpenoids that have a variety of functions, including defense against pests and pathogens (5–7). A few bacteria have been shown to produce sterols (8), however, the most common bacterial cyclic triterpenoids are the pentacyclic hopanoids, which are thought to function as “sterol surrogates” in bacterial membranes (9, 10). Although the majority of interest in cyclic triterpenoids stems from their essential physiological roles and unique enzymatic biosynthesis (5, 7, 11), these lipids are also significant from a geological perspective. Cyclic triterpenoids are quite recalcitrant and, as a result, are well preserved in sedimentary rocks and can serve as geological biomarkers that link organisms to environments deep in Earth’s history (12).

The interpretation of geological biomarkers is primarily based on the occurrence of their diagenetic precursors in extant organisms and/or their prevalence in specific ecosystems (12). However, incomplete understanding of the distribution and function of potential biomarkers in modern systems can lead to inconsistencies in their interpretations. For example, arborane biomarkers are thought to be derived from isoarborinol, an unusual pentacyclic triterpenol whose only known extant sources are certain flowering plants (13–16). Thus, arborane biosignatures are considered robust indicators of angiosperms and of terrestrial input into marine and lacustrine environments. However, the detection of arborane signatures in Permian and Triassic sediments (17–19), which predates the accepted first appearance of angiosperms, as well as compound-specific 13C values that are inconsistent with plant sources, led researchers to propose that there were microbial sources of isoarborinol (19–21). These sources, however, remain undiscovered.

The discovery of arborinol lipids in a microbe would also be significant from a biochemical perspective. Cyclic triterpenoid lipids are synthesized by cyclization of a 30-carbon acyclic isoprenoid substrate through a series of carbocation intermediates in the central cavity of a terpene cyclase (class II) enzyme (11, 22). These enzymes can be distinguished based on three general characteristics: the use of squalene or oxidosqualene as the initial substrate, the conformation of the acyclic substrate in the more energetically favorable all-chair (CCC) versus the more strained chair−boat−chair (CBC or B boat), and the total number and size of the rings generated in the final product (e.g., tetracyclic sterols versus pentacyclic hopanoids and isoarborinol) (5, 7, 23). Hopanoid synthases fold squalene into the CCC conformation and generate a pentacyclic structure (11, 24), whereas sterol synthases cyclize oxidosqualene in the CBC conformation and generate a tetracyclic structure (25). An arborinol synthase represents a unique combination of these characteristics. It is similar to a sterol cyclase in that it cyclizes oxidosqualene in the CBC conformation (6, 7, 23) but differs in that its final product has the pentacyclic structure similar to a bacterial hopanoid (23). Various hopanoid, sterol, and plant triterpenoid synthases have been characterized, including a rice isoarborinol synthase (IAS) (6). However, a microbial enzyme that cyclizes oxidosqualene in the CBC conformation to an arborinol lipid has yet to be identified.

Here, we present two pentacyclic triterpenols, eudoraenol and adriaticol, produced by the marine heterotrophic bacterium Eudoraea adriatica (26). These molecules represent the first arborane lipids identified outside of the plant kingdom. Further, the E. adriatica eudoraenol synthase (EUS) is the first example of a microbial enzyme that cyclizes an oxidosqualene precursor in the CBC conformation to a pentacyclic triterpenol. EUS is phylogenetically distinct from plant triterpene synthases, indicating that it is not derived from the known eukaryotic IAS. To further understand the relationship between these enzymes, we created a bacterial lanosterol synthase (LAS) gain of function variant with substitutions in four key amino acid residues that synthesizes both tetracyclic and pentacyclic triterpenols. These results together support the hypotheses that synthesis of the arborane skeleton has likely arisen more than once within the oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC) family and that Permian and Triassic arborane biomarkers are likely from a microbial source.

Results

E. adriatica Produces Unique Triterpenols of the Arborinol Class.

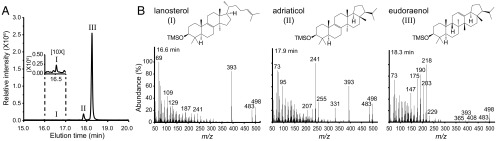

An OSC homolog was previously identified in the aerobic heterotrophic bacterium E. adriatica (8, 27), a member of the family Flavobacteriaceae in the phylum Bacteriodetes that was isolated from surface waters of the Adriatic Sea (26). Our lipid analysis of E. adriatica identified a trace amount of lanosterol along with two potential sterol-like triterpenols whose spectra were distinct from any that had been previously published (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). The two compounds, found in a 7:1 ratio, were purified by reversed-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC), and their structures were determined using 800-MHz 1H NMR (Fig. S2 and Tables S1 and S2). The spectra of both compounds showed six methyl singlets and two methyl doublets typical of the hopane skeleton. Heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) spectra localized the double bonds at positions 12 and 8, indicating that these were isomers of the fernanes neomotiol and isomotiol, respectively (Fig. S2). Mass spectra confirmed the positions of the double bonds with a diagnostic ion at m/z = 218 for the major Δ12 compound and its derivatives, and diagnostic ions at m/z = 259, 301, and 331 for the free Δ8 compound, its acetate, and its trimethylsilyl (TMS) ether, respectively (Fig. S2) (28). The stereochemical configurations were determined by chemical correlation with isoarborinol (16) and boehmerol (29), both of which arise from CBC cyclization (7), using acid-catalyzed isomerization. The major triterpenol isomerized to boehmerol and the minor component was formed in the acid-catalyzed isomerization of isoarborinol (Fig. S2). These data demonstrate that E. adriatica is producing two triterpenoids of the arborane class that we have named eudoraenol and adriaticol, respectively. These are the first new OSC products with a constitutional hopanoid skeleton to be discovered since boehmerol was reported 30 y ago (29), as well as the first evidence of bacterial synthesis of pentacyclic CBC triterpenols derived from oxidosqualene.

Fig. 1.

Polycyclic triterpenols detected in E. adriatica. (A) GC-MS total ion chromatogram (TIC) of the alcohol-soluble fraction of a total lipid extract (TLE), derivatized to TMS ethers, of E. adriatica showing three distinct peaks eluting at 16.6 min (I), 17.9 min (II) and 18.3 min (III). (Inset) Peak I visible when a 10× concentrate was loaded. Triterpenols shown here constitute ∼1% of the TLE. (B) Mass spectrum (MS) of compound I identified as lanosterol by comparison with published spectra. MS of compound II with structure determined by NMR and designated adriaticol. MS of compound III with structure determined by NMR and designated eudoraenol. NMR data are listed in Table S1 and shown in Fig. S2. GC-MS analysis of acetate esters is shown in Fig. S1.

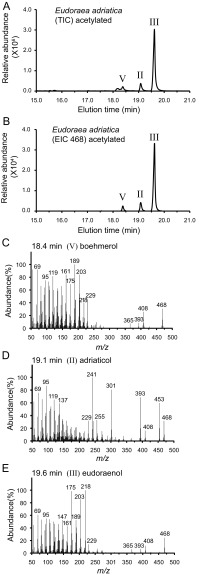

Fig. S1.

Polycyclic triterpenoids detected in E. adriatica (as in Fig. 1 except acetate ester derivatives). (A) GC-MS TIC of the alcohol-soluble fraction of a TLE (derivatized to acetate esters) of E. adriatica. (B) GC-MS EIC (m/z 468) of the alcohol-soluble fraction of a TLE (derivatized to acetate esters) of E. adriatica. We detected boehmerol (V) only when we derivatized to acetate esters. (C) MS peak eluting at 18.4 m identified as compound V, boehmerol. (D) MS of the peak eluting at 19.1 m identified as compound II, adriaticol. (E) MS peak eluting at 19.6 m identified as compound III, eudoraenol.

Fig. S2.

NMR analyses of E. adriatica triterpenols. (A) The 800-MHz 1H NMR spectra of eudoraenol and adriaticol. (B) The 201-MHz 13C NMR spectrum of eudoraenol. (C) The 800-MHz HMBC spectra of methyl regions of eudoraenol and adriaticol. (D) The 800-MHz heteronuclear single quantum coherence−distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (HSQC-DEPT) spectra of eudoraenol and adriaticol. (E) Diagnostic molecular ions of eudoraenol and adriaticol. (F) Acid-catalyzed rearrangements of eudoraenol and adriaticol. MsOH, methanesulfonic acid.

Table S1.

The 800-Mz 1H and 201-Mz 13C NMR assignments

| Position | Eudoraenol | Adriaticol |

| 1 | 34.57 | 35.4 |

| 1.46, m | 1.20, m; 1.732, dt 13.0, 3.5 | |

| 2 | 29.04 | 27.6 |

| 1.63, m; 1.72, m | 1.58 m; 1.66 m | |

| 3 | 79.23 | 78.9 |

| 3.237, dt 11.9, 5.3 | 3.229, dt 11.8, 4.5 | |

| 4 | 39.39 | 38.7 |

| 5 | 47.59 | 50.3 |

| 1.385, dd 11.5, 2.5 | 1.016, dd 12.7, 2.0 | |

| 6 | 18.91 | 18.3 |

| 1.313, m; 1.59, m | 1.48, m; 1.69, m | |

| 7 | 32.50 | 26.3 |

| 1.20, m; 1.88, m | 2.01, m; 2.15, m | |

| 8 | 39.33 | 134.9 |

| 9 | 43.31 | 134.6 |

| 2.025, dd 11.2, 6.3 | ||

| 10 | 36.78 | 37.3 |

| 11 | 24.80 | 19.0 |

| 1.932, m; 2.072, m | 1.93, m; 1.98, m | |

| 12 | 119.23 | 30.9 |

| 5.114, dt 3.5, 3.0 | 1.302, dd 13.1, 9.9 | |

| 13 | 145.52 | 37.0 |

| 14 | 43.50 | 40.4 |

| 15 | 25.16 | 28.3 |

| 1.111, m; 1.62, m | 1.22 and/or 1.82 | |

| 16 | 34.69 | 36.1 |

| 1.66, m; 1.90, m | 1.46, m; 1.68, m | |

| 17 | 39.72 | 42.8 |

| 18 | 52.95 | 52.9 |

| 2.140, m | 1.50, m | |

| 19 | 23.11 | 20.4 |

| 1.268, m; 1.69, m | 1.27, m; 1.40, m | |

| 20 | 28.33 | 28.1 |

| 1.22, m; 1.87, m | 1.22, m; 1.82,m | |

| 21 | 60.34 | 59.7 |

| 1.15, m | 0.97, m | |

| 22 | 31.71 | 30.7 |

| 1.48, m | 1.45, m | |

| 23 | 28.81 | 27.8 |

| 0.981, s Me | 1.000, s Me | |

| 24 | 16.00 | 15.3 |

| 0.818, s Me | 0.808, s Me | |

| 25 | 24.03 | 18.8 |

| 0.997, s Me | 0.969, s Me | |

| 26 | 21.27 | 22.1 |

| 0.925, s Me | 0.957, s Me | |

| 27 | 23.74 | 16.3 |

| 1.141, s Me | 0.679, s Me | |

| 28 | 18.52 | 14 |

| 0.781, s Me | 0.758, s Me | |

| 29 | 22.48 | 21.9 |

| 0.936, d 6.5 Me | 0.893, d 6.5 Me | |

| 30 | 22.60 | 22.8 |

| 0.846, d 6.6 Me | 0.829, d 6.5 Me |

All 13C data are in boldface; coupling constants are given in Hertz. The assignments were determined by HSQC-DEPT, HMBC, and correlation spectroscopy (COSY) 2D NMR experiments. The 1H and 13C chemical shifts are given to three and two decimal places, respectively, if directly observed, or two and one decimal places, respectively, if determined from 2D spectra. Me, methyl.

Table S2.

HPLC retention times and percent composition of various cyclic triterpenoids identified in this study

| Triterpenol | HPLC RT, min | Strain ABB595 composition, % | Strain ABB686 composition, % |

| Lanosterol | 47.2 | 13.4 | 59.8 |

| Parkeol | 47.2 | 2.9 | 20.0 |

| Boehmerol | 52.2 | 0.2 | 3.2 |

| Unidentified | 54.1 | — | 0.2 |

| Unidentified | 58.9 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Unidentified | 58.9 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Eudoraenol | 74.0 | 72.5 | 0.3 |

| Adriaticol | 76.1 | 10.2 | 9.4 |

| Isoarborinol | 78.4 | 0.6 | 5.9 |

Strain ABB595 is oxidosqualene-producing E. coli strain expressing the wild type E. adriatica osc. Strain ABB686 is oxidosqualene-producing E. coli strain expressing the M. alcaliphilum osc variant W252S, H254Y, Y521V, N717Y.

E. adriatica and Plant OSC Are Phylogenetically Distinct.

Because the phylogenetic distribution of OSC homologs in bacteria is sporadic, it was unclear whether the E. adriatica OSC was derived by evolutionary diversification of a bacterial or eukaryotic OSC or by acquisition of a plant IAS through horizontal gene transfer. To address this, we determined the phylogenetic relationship of over 800 terpenoid cyclase homologs obtained from the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) genomic and metagenomic databases using maximum likelihood analysis (30, 31). We found that the E. adriatica cyclase does not cluster with plant triterpenoid synthases and, in particular, is distinct from the rice IAS (Fig. 2A). Instead, the E. adriatica OSC branches within a distinct clade of OSCs from three single-cell genomes of Eudoraea species isolated from the North Sea as well as 16 metagenomic OSC sequences (Fig. 2B). The metagenomic sequences separate into two distinct clades reflecting different ecosystems—one from marine sources and the other from lacustrine sources. These data indicate that eudoraenol and adriaticol may be produced in freshwater as well as marine environments and that there could be additional extant bacterial producers of similar triterpenoids.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of EUS. (A) Unrooted maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of OSC homologs identified in genomes and metagenomes (851 sequences) with bacterial squalene-hopene cyclases (SHC) and eukaryotic squalene tetrahymanol cyclases (STC) as the outgroup. Sequences in each branch have been collapsed for clarity. Bacterial clades are colored in blue or red, with the total number of genome and metagenome sequences as well as representative cultured organisms listed for each group. (B) Expanded Bacterial OSC Group 1 branch from the phylogenetic tree in A. JGI locus tag numbers are listed for each metagenome sequence in parentheses. The scale bar indicates 0.1 changes per nucleotide site.

E. adriatica OSC Synthesizes Eudoraenol and Adriaticol Directly from Oxidosqualene.

Detection of a minor amount of lanosterol in E. adriatica extracts raised the possibility that the E. adriatica OSC does not synthesize eudoraenol and adriaticol directly. Rather, it was conceivable that the E. adriatica OSC first synthesizes a partially cyclized CBC compound, and then additional protein(s) subsequently modify this product to generate eudoraenol and adriaticol. Precedence for this multiple-enzyme scenario exists in the synthesis of the pentacyclic triterpenoid tetrahymanol (32). In this case, eukaryotes use a single cyclase to synthesize tetrahymanol directly from squalene, but bacteria use a two enzyme system with the first cyclizing squalene to diploptene and the second catalyzing a ring expansion to tetrahymanol.

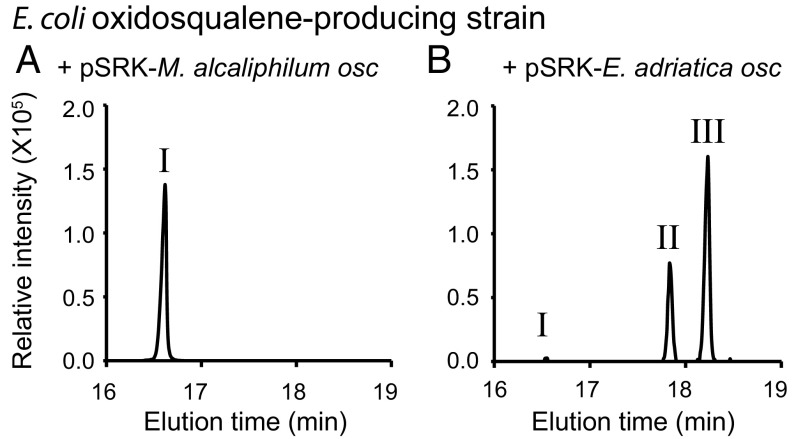

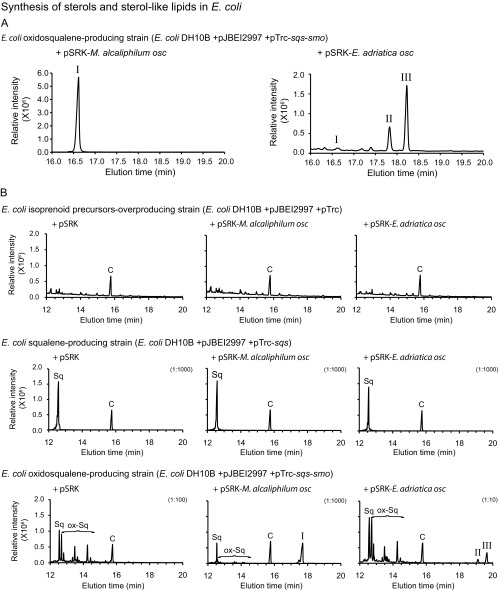

To determine if the E. adriatica OSC cyclizes oxidosqualene directly to eudoraenol and adriaticol, we developed an inducible heterologous expression system using three plasmids in Escherichia coli. The first plasmid increases overall isoprenoid synthesis by overexpression of the mevalonate pathway (33). The second plasmid enables synthesis of the acyclic triterpenoids squalene and/or oxidosqualene by encoding the squalene synthase (sqs) gene alone or together with the squalene epoxidase (smo) gene from the sterol-producing bacterium Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum. Finally, the third plasmid encodes putative OSC (osc) genes. Expression of M. alcaliphilum osc, which encodes an LAS, in an oxidosqualene-producing E. coli strain resulted in lanosterol synthesis (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3) (32). Expression of E. adriatica osc in an oxidosqualene-producing E. coli strain resulted in synthesis of eudoraenol and adriaticol as well as a trace amount of lanosterol, as observed in E. adriatica lipid extracts (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3). Expression of the E. adriatica osc in a squalene-producing E. coli strain did not result in any cyclic triterpenoid production (Fig. S3). These results confirm that E. adriatica OSC synthesizes the pentacyclic triterpenols eudoraenol and adriaticol directly from an oxidosqualene precursor.

Fig. 3.

Sterol and eudoraenol synthesis in an E. coli heterologous OSC expression system. GC-MS extracted ion chromatograms (EIC m/z 498) of the alcohol-soluble fraction of a TLE (derivatized to TMS ethers) of an oxidosqualene-producing strain of E. coli overexpressing either (A) M. alcaliphilum osc or (B) E. adriatica osc from plasmid pSRK. Lipid content of peaks was identified by MS as follows: 16.6 min lanosterol (I), 17.8 min adriaticol (II), and 18.2 min eudoraenol (III). TICs of samples and controls are shown in Fig. S3.

Fig. S3.

Synthesis of sterols and sterol-like lipids in E. coli. (A) TIC corresponding to Fig. 3. (Left) TIC of E. coli strain overexpressing M. alcaliphilum OSC (WT) (alcohol fraction, TMS) and (Right) TIC of E. coli strain overexpressing E. adriatica OSC (WT) (alcohol fraction, TMS). Peaks eluting at 16.6 min identified as lanosterol (I), 17.8 min identified as adriaticol (II), and 18.2 min identified as eudoraenol (III). (B) GC-MS analysis (TIC) of acetate ester derivatives of TLE of E. coli overexpression strains. Each E. coli (DH10B) strain harbors three plasmids: (i) pJBEI2997 [pACYC ori, chloramphenicol resistant (CmR)] (33) encodes eight genes that, together, overexpress the melvalonate pathway resulting in overproduction of isoprenoid precursors; (ii) a pTrc derivative [ColE1 ori, ampicillin resistant (AmpR)] (47) encoding no gene (empty), one gene (M. alcaliphilum sqs), or two genes (M. alcaliphilum sqs and smo) resulting in no effect, squalene (Sq) synthesis, or oxidosqualene (ox-Sq) synthesis, respectively; and (iii) a pSRK derivative [pBBR1 ori, gentamicin resistant (GmR)] encoding no gene, M. alcaliphilum osc, or E. adriatica osc resulting in no effect, lanosterol (I) synthesis, or adriaticol (II) and eudoraenol (III) synthesis, respectively. Cholestanol standard peak is marked with a C. Dilution factor is indicated in parentheses.

Identification of Key Residues Distinguishing Pentacyclic Versus Tetracyclic Triterpenol Synthases.

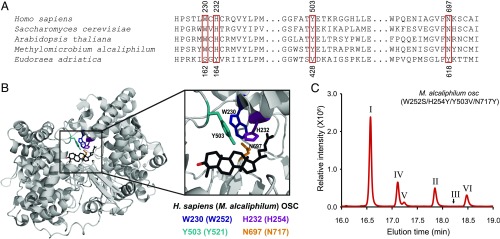

The predominant synthesis of pentacyclic arborinol lipids rather than tetracyclic sterols by E. adriatica eudoraenol synthase indicates that homology alone is not sufficient to predict the full lipid profile of a putative cyclase. We took a comparative analysis approach to determine specific amino acid residues that are necessary for synthesis of the fifth (E) ring structure that could aid in identification of other OSCs that potentially synthesize pentacyclic lipids. First, we identified amino acid residues that are conserved in EUS and conserved among sterol synthases but that differ between the groups by aligning E. adriatica EUS with a diversity of bacterial OSCs known to synthesize tetracyclic sterols (Fig. 4A) (8). We further selected residues that are likely to be in the active site cavity near the site of formation of the E ring by alignment with the Homo sapiens LAS X-ray crystal structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1W6K] (Fig. 4B) (34). We then made reciprocal substitutions by changing the identity of residues in M. alcaliphilum LAS to those in E. adriatica EUS, and vice versa, and determined the lipid profile of these variant enzymes using our E. coli heterologous expression system.

Fig. 4.

Identification of key residues necessary for synthesis of pentacyclic arborinol versus tetracyclic sterols. (A) Partial amino acid sequence alignment of selected OSCs. Top numbers reflect positions in H. sapiens and bottom numbers reflect those in E. adriatica. Red boxes indicate positions that were changed by site-directed mutagenesis. (B) X-ray crystal structure of H. sapiens OSC (gray cartoon representation; PDB ID code 1W6K) bound to lanosterol (black stick representation with the C3–OH in red). Side chains of amino acids of interest are shown in stick representation in color as indicated (H. sapiens/M. alcaliphilum numbering). (C) GC-MS TIC of the alcohol-soluble fraction of a TLE (derivatized to TMS ethers) of E. coli oxidosqualene production strain overexpressing the M. alcaliphilum OSC W252S/H254Y/Y503V/N717Y variant, demonstrating partial conversion of an LAS to an EUS. Peaks labeled with Roman numerals have been identified by MS and/or NMR as follows: lanosterol (I), adriaticol (II), eudoraenol (III), parkeol (IV), boehmerol (V), and isoarborinol (VI). Structures of these lipids are shown in Fig. S4, and mass spectra are shown in Fig. S5.

Two positions that are highly conserved in LAS, H232 (histidine) and Y503 (tyrosine) (H. sapiens numbering), had a substantial difference in identity from the homologous residues in E. adriatica EUS [Y164 (tyrosine) and V428 (valine)] (Fig. 4A). Previous studies of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae LAS indicated that this hydrogen-bonded H–Y pair plays a key role in both cyclization and terminal proton abstraction to yield the tetracyclic structure of lanosterol (35–38), suggesting that these residues could potentially contribute to the formation of the eudoraenol and adriaticol pentacyclic structure. To test this, we changed these residues, both individually and in combination, in M. alcaliphilum LAS to the corresponding E. adriatica EUS residues (Table S3; lipid structures shown in Fig. S4). The LAS H254Y single variant had significantly reduced oxidosqualene cyclization in general, whereas the Y521V variant synthesized parkeol, a lanosterol isomer, in addition to lanosterol (Table S3). Although we found that the H254Y/Y521V double variant synthesized a trace amount of adriaticol in addition to lanosterol and parkeol, those two changes alone were not sufficient to enable LAS to synthesize the main EUS pentacyclic structure, eudoraenol.

Table S3.

Lipids identified by GC-MS, HPLC and NMR analysis in E. coli strains expressing M. alcaliphilum osc and E. adriatica osc

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |

| Amino acid substitutions | Lanosterol | Adriaticol | Eudoraenol | Isoarborinol | Boehmerol | Parkeol |

| M. alcaliphilum OSC | ||||||

| Wild type | + | |||||

| W252(230)S | + | tr. | + | |||

| H254(232)Y | + | |||||

| Y521(503)V | + | + | ||||

| N717(697)Y | + | + | ||||

| W252(230)S, N717(697)Y | + | tr. | tr. | + | ||

| H254(232)Y, Y521(503)V | + | tr. | + | |||

| H254(232)Y, Y521(503)V, N717(697)Y | tr. | tr. | tr. | tr. | ||

| W252(230)S, H254(232)Y, Y521(503)V | + | tr. | tr. | tr. | + | |

| W252(230)S, H254(232)Y, Y521(503)V, N717(697)Y | + | + | tr. | + | + | + |

| E. adriatica OSC | ||||||

| Wild type | + | + | + | tr. | tr. | + |

| S162(230)W | ||||||

| Y164(232)H | + | |||||

| V428(503)Y | + | + | + | |||

| Y618(697)N | + | + | + | tr. | ||

| Y164(232)H, V428(503)Y | tr. | |||||

| S162(230)W Y618(697)N | ||||||

| S162(230)W, Y164(232)H, V428(503)Y, Y618(697)N |

Homologous residue in H. sapiens OSC indicated in parentheses; tr., trace.

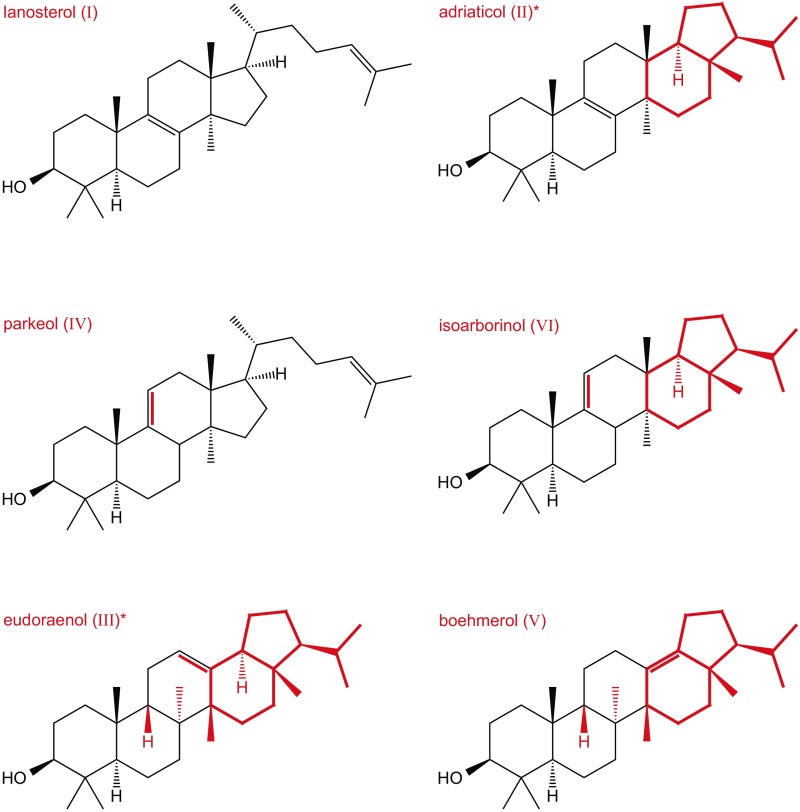

Fig. S4.

Structures of lipids detected in this study. Asterisks (*) indicate new structures. Red highlights differences from lanosterol.

Continuing our comparative analysis, we found that E. adriatica EUS residues S162 (serine) and Y618 (tyrosine) not only differ from the corresponding M. alcaliphilum LAS residues W252 (tryptophan) and N717 (asparagine) but are also adjacent to the above residues (H254 and Y521) in the active site cavity (Fig. 4B). Although the identities of these four residues are not completely conserved in all LAS homologs (24), they tend to covary and always differ from those in EUS. We changed these residues alone and in combination with the previous substitutions in the M. alcaliphilum LAS and tested the variant proteins to determine whether these residues could contribute to the synthesis of the pentacyclic arborinols. The W252S/N717Y double variant synthesized the pentacyclic lipids adriaticol and isoarborinol in addition to tetracyclic parkeol and lanosterol. However, the single variants (W252S or N717Y alone) only synthesized parkeol and lanosterol (Table S3), indicating that these residues together affect synthesis of the E ring. An M. alcaliphilum LAS variant with all four substitutions (W252S, H254Y, Y521V, and N717Y) synthesized tetracyclic lanosterol and parkeol and pentacyclic adriaticol and isoarborinol as well as trace amounts of pentacyclic isomers eudoraenol and boehmerol, with all products retaining the CBC conformation (Fig. 4C, Fig. S5, and Table S3).

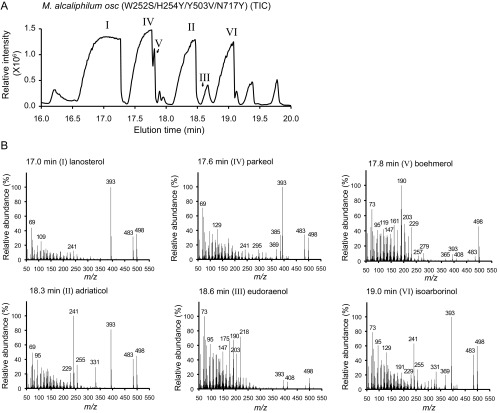

Fig. S5.

M. alcaliphilum OSC mutagenesis. (A) GC-MS TIC of the alcohol-soluble fraction of a TLE (derivatized to TMS ethers) of an E. coli oxidosqualene production strain overexpressing the M. alcaliphilum OSC W252S/H254Y/Y503V/N717Y variant (same sample as in Fig. 4C, 100× loaded). Peaks labeled with Roman numerals have been identified by MS and/or NMR as follows: lanosterol (I), adriaticol (II), eudoraenol (III), parkeol (IV), boehmerol (V), and isoarborinol (VI). (B) MS of peaks in A eluting at 17.0 min (I, lanosterol), 17.6 min (IV, parkeol), 17.9 min (V, boehmerol), 18.3 min (II, adriaticol), 18.6 min (III, eudoraenol), and 19.0 min (VI, isoarborinol).

Finally, we constructed the reciprocal substitutions of these four residues in E. adriatica EUS to the identity of those in M. alcaliphilum LAS. Although three of the four single substitution variants still synthesized pentacyclic structures, the identity of those structures shifted with each substitution (Table S3). The EUS Y164H single variant synthesized eudoraenol but not adriaticol, whereas the EUS V428Y substitution resulted in isoarborinol synthesis in addition to eudoraenol and adriaticol. The EUS Y618N also synthesized both eudoraenol and adriaticol, but the dominant product was a tetracyclic structure, which we have tentatively identified as protosta-20 (22), 24-dien-3-ol. The S162W substitution completely eliminated both tetracyclic and pentacyclic lipid synthesis, which made it difficult to interpret the results of subsequent combined substitutions (Table S3). Nonetheless, these single substitution results suggest that the collective identity of these four amino acid residues is important not only for the synthesis of the additional ring in pentacyclic versus tetracyclic triterpenoids but also for the positioning of the double bonds and the stereochemistry of the methyl groups in the final product.

Discussion

Bioinformatics coupled to lipid analyses and protein characterization have contributed significantly to our understanding of the taxonomic distribution of microbial lipid biomarkers, the enzymatic mechanisms of their synthesis, and the potential evolutionary relationships of their biosynthetic pathways (39). Here, this combined approach revealed two triterpenols that not only address a current incongruity in biomarker signatures but also provide mechanistic insight into polycyclic triterpenoid biosynthesis.

Eudoraenol and adriaticol are unique in both their chemical structure and biological source. Their structures are similar to isoarborinol, a C3-oxygenated pentacyclic triterpenol whose only known biological source is certain families of angiosperms (13). However, some have hypothesized that there must be microbial sources for arborinol lipids because their diagenetic derivatives, arboranes, have been identified in geologic samples whose deposition is inconsistent with the distribution of isoarborinol in modern organisms (17–21). Although E. adriatica does not produce isoarborinol per se, it does synthesize an isoarborinol isomer, adriaticol. This represents the first bacterial source of this class of lipids, thereby linking arborinol/arborane compounds to a potential bacterial source through geologic time.

In addition, the E. adriatica EUS is the first example of a triterpenoid synthase from a bacterium that cyclizes oxidosqualene to a pentacyclic triterpenol, which is significant from both an evolutionary and biochemical perspective. Phylogenetic analysis of an isoarborinol synthase (IAS) from Oryza sativa (rice) demonstrated that it was recently derived from a plant cycloartenol synthase (6). Our analysis demonstrates that E. adriatica EUS is phylogenetically distinct from O. sativa IAS and most likely was not acquired via horizontal gene transfer from a plant source. Rather, this enzyme likely evolved separately within bacteria, being either derived from an LAS consistent with the proposed evolutionary scheme of Fischer and Pearson (23) or instead from a squalene-hopene cyclase consistent with the proposals of Ourisson et al. (21). The identification of EUS now enables structural and biochemical studies of this bacterial arborinol class of enzymes that could provide experimental evidence for these evolutionary scenarios.

Further, structural and enzymatic studies of EUS could provide insight into the cyclization mechanism of triterpene synthases—the key step in determining the basic cyclic structure of various polycyclic triterpenoids (35). Using a reverse genetics approach guided by amino acid variations between EUS and LAS, we demonstrated that substitution of four amino acid residues (W230/252S, H232/254Y, Y503/521V, and N697/717Y; H. sapiens/M. alcaliphilum numbering) in the LAS active site cavity resulted in a gain of function variant that could cyclize an additional (E) ring to synthesize pentacyclic as well as tetracyclic triterpenoids. We hypothesize that these four substitutions allow for nondiscriminate cyclization (40) by LAS resulting in increased synthesis of tetracyclic parkeol as well as synthesis of various pentacyclic triterpenols. Given the close proximity of these four residues, these substitutions may also alter the LAS cavity to accommodate a bulkier pentacyclic structure. Single amino acid substitutions of these homologous residues in yeast and fungal LAS impact various aspects of the cyclization reaction, including carbocation stabilization, backbone rearrangement, and deprotonation of the final product (11, 34, 38, 41–43). However, in those studies, substitutions only inhibit or alter synthesis of tetracyclic sterols and do not enable the synthesis of pentacyclic triterpenoids. A recent study of a plant triterpene synthase, the Avena strigosa (oat) β-amyrin synthase (SAD1), demonstrated that substitution of an amino acid residue adjacent to the active site cavity disrupted formation of the E ring of the pentacyclic triterpenol β-amyrin (44). This substitution, S725F (homologous to H. sapiens LAS residue S699), is two amino acid residues downstream of our M. alcaliphilum LAS N717Y substitution, which enabled the synthesis of pentacyclic triterpenoids. Even though the β-amyrin synthase differs from lanosterol and arborinol synthases in that it cyclizes oxidosqualene in the CCC rather than the CBC conformation (5, 7), these data demonstrate that this region is critical to the formation of the E ring in both plant and bacterial triterpenoid synthases. Thus, our studies together underscore the functional diversity of triterpenoid synthases and demonstrate the potential for engineering the specificity of these cyclases to synthesize novel triterpenoids and other secondary metabolites.

Finally, the four EUS amino acid residues identified in this study can now be used as diagnostic markers to discover other potential sources of arborinols and related lipids. Although the distribution of EUS in genomic databases is currently restricted to Eudoraea species (perhaps reflecting a sampling bias in genomic databases), analysis of metagenomic sequences reveals that there are potentially other marine (e.g., North Sea) or lacustrine (e.g., Lake Huron) bacterial sources. Thus, using the E. coli heterologous expression system developed here, we can now experimentally determine if any of these other putative arborinol synthases can synthesize eudoraenol, isoarborinol, or perhaps other triterpenoids. Ultimately, this combined bioinformatics and biochemical approach should enable us to identify additional unique biomarker lipid synthesis enzymes, analyze their products, and link them to cultured and/or uncultured organisms as well as ancient and/or modern environments. This, in turn, will inform our understanding of the evolutionary history of biomarker lipids and allow for more robust interpretations of their occurrence in the rock record.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Culture.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table S4. E. adriatica DSM 19308 was cultured in Bacto Marine Broth (Difco 2216) at 30 °C with shaking at 225 rpm. E. coli was cultured in lysogeny broth or terrific broth (TB) at 30 °C or 37 °C with shaking at 225 rpm. Media for E. coli was supplemented, if necessary, with gentamicin (15 μg/mL), carbenicillin (100 μg/mL), and/or chloramphenicol (20 μg/mL).

Table S4.

Bacterial strains

| Strain | Genotype/Description | Source |

| Eudoraea adriatica (PVW365) | Wild type (DSM 19308) | DSMZ |

| Escherichia coli DH10B (PVW1022) | Strain used for cloning and for heterologous expression F− endA1 recA1 galE15 galK16 nupG rpsL ΔlacX74 Φ80lacZΔM15 araD139 Δ(ara,leu)7697 mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC)λ− | Invitrogen |

Molecular Cloning.

Plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Tables S5 and S6. Details of molecular cloning techniques are described in SI Materials and Methods (45).

Table S5.

Plasmids

| Plasmid | Description | Source |

| pSRKGm (pABB037) | pBBR1 ori, lac promoter, GmR | (46) |

| pSRKGm-lacUV5 (pABB251) | pBBR ori, lacUV5 promoter, GmR | (32) |

| pSRKGm-lacUV5-rbs5 (pABB492) | pBBR1 ori, lacUV5 promoter, GmR; | This study |

| RBS of pABB251 altered by SDM using oligonucleotide AB409 | ||

| pTrc99a (pABB276) | pBR322 ori, lacUV5 promoter, AmpR | (47) |

| pJBEI2997 (pABB302) | p15A ori, CmR, Addgene #35151 (pBbA5c-MevT(CO)-MBIS(CO, ispA)), J. Keasling and T.S. Lee | (33) |

| pTrc-sqs (pABB303) | Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum MEALZ_3096 (squalene synthase) expression plasmid | (32) |

| pTrc-sqs-smo (pABB394) | Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum MEALZ_3096-MEALZ_0767 (squalene synthase-squalene epoxidase) expression plasmid; | This study |

| MEALZ_3096 was amplified by PCR with primers AB206 and AB243, MEALZ_0768 was amplified by PCR with primers AB244 and AB245, and both fragments were cloned together into the NcoI site of pTrc99a via SLIC. | ||

| pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497) | Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum MEALZ_3096-MEALZ_0767 (squalene synthase-squalene epoxidase) expression plasmid, stronger ribosome binding site; | This study |

| RBS upstream of smo altered in pABB394 by SDM using oligonucleotide AB408 | ||

| pSRK-EAD-osc (pABB471) | Eudoraea adriatica G504DRAFT_2316 (OSC) expression plasmid | This study |

| G504DRAFT_2316 was amplified by PCR with primers AB351 and AB352 and cloned into the NcoI site of pSRK-lacUV5-Gm (pABB251) via SLIC. | ||

| pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc (pABB577) | Eudoraea adriatica G504DRAFT_2316 (OSC) expression plasmid, stronger ribosome binding site; | This study |

| RBS in pABB471 altered by SDM using oligonucleotide AB425 | ||

| pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-Y164H_V428Y (pABB624) | SDM of pABB577 using oligonucleotides AB456 and AB457 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-Y164H (pABB723) | SDM of pABB577 using oligonucleotide AB456 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-V428Y (pABB724) | SDM of pABB577 using oligonucleotide AB457 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-S162W (pABB775) | SDM of pABB577 using oligonucleotide AB492 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-Y618N (pABB777) | SDM of pABB577 using oligonucleotide AB494 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-S162W_Y618N (pABB779) | SDM of pABB577 using oligonucleotides AB492 and AB494 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-S162W_Y164H_V428Y_Y618N (pABB781) | SDM of pABB577 using oligonucleotides AB493, AB494 and AB457 | This study |

| pSRK-MAH-osc (pABB473) | M. alcaliphilum MEALZ_0768 (OSC) expression plasmid | This study |

| MEALZ_0768 was amplified by PCR with primers AB347 and AB348 and cloned into the NcoI site of pSRK-lacUV5-Gm (pABB251) via SLIC. | ||

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc (pABB578) | M. alcaliphilum MEALZ_0768 (OSC) expression plasmid, stronger ribosome binding site; | This study |

| RBS in pABB473 altered by SDM using oligonucleotide AB426 | ||

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-H254Y (pABB645) | SDM of pABB578 using oligonucleotide AB452 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-Y521V (pABB663) | SDM of pABB578 using oligonucleotide AB453 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-N717Y (pABB730) | SDM of pABB578 using oligonucleotide AB462 | This study |

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-W252S (pABB744) | SDM of pABB578 using oligonucleotide AB485 | (this study) |

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-H254Y_Y521V (pABB644) | SDM of pABB578 using oligonucleotides AB452 and AB453 | (this study) |

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-W252S_N717Y (pABB749) | SDM of pABB578 using oligonucleotides AB462 and AB485 | (this study) |

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-H254Y_Y521V_N717Y (pABB732) | SDM of pABB644 with oligonucleotide AB462 | (this study) |

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-W252S_H254Y_Y521V (pABB733) | SDM of pABB644 with oligonucleotide AB461 | (this study) |

| pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-W252S_H254Y_Y521V_N717Y (pABB665) | SDM of pABB578 using oligonucleotides AB461, AB453 and AB485 | (this study) |

EAD, E. adriatica; MAH, M. alcaliphilum; RBS, ribosome binding site; SDM, site-directed mutagenesis.

Table S6.

Oligonucleotides

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | Notes |

| AB012 | ccagggttttcccagtcac | pSRK R seq |

| AB190 | aatgcagctggcacgacagg | pSRK F seq |

| AB204 | caattaatcatccggctcgt | pTrc F seq |

| AB205 | cgcttctgcgttctgattta | pTrc R seq |

| AB206 | acaatttcacacaggaaacagacatgagcgcattacaaccaacact | pTrc-sqs-smo cloning |

| AB243 | cgcatcatcatttttctaattattatagtgctgacttagctttcagggattg | pTrc-sqs-smo cloning |

| AB244 | taagtcagcactataataattagaaaaatgatgatgcgtatcaagtaactaaagatgg | pTrc-sqs-smo cloning |

| AB245 | gggtaccgagctcgaattcttattaacgcttgaaataatcgctaaaaatcccc | pTrc-sqs-smo cloning |

| AB347 | acaatttcacacaggaaacagcaatgttgactgtaaaacccgcttgg | pSRK-MAH-osc cloning |

| AB348 | gcttggcgtaatcatggtcattatcatttttctaacatccttaaattatagatcctacaa | pSRK-MAH-osc cloning |

| AB351 | ggataacaatttcacacaggaaacagcaatgcaaaatattgaacaggccat | pSRK-EAD-osc cloning |

| AB352 | cgcttggcgtaatcatggtcattactaagaaattttctcatttagttttcccctg | pSRK-EAD-osc cloning |

| AB353 | cgattgtctatcgagacagatgaac | EAD-osc 186-F seq |

| AB354 | gcacttcttgaaacggaagg | EAD-osc 397-F seq |

| AB408 | atgatgatgcgtaggaggtaactaaagatgg | smo RBS SDM |

| AB409 | ttcacacaggaggcaagcatatgaccatg | pSRK RBS SDM |

| AB425 | caatttcacacaggaggcaagcatatgcaaaatattgaacag | pSRK-EAD-osc RBS SDM |

| AB426 | caatttcacacaggaggcaagcatatgttgactgtaaaacc | pSRK-MAH-osc RBS SDM |

| AB450 | tgttcggcacggtcatgc | MAH-osc 178-F seq |

| AB452 | cgctactggtgctattgccgaatggtg | MAH-osc H254Y |

| AB453 | ggctggtcgactgttgaattaacgcgcg | MAH-osc Y521V |

| AB456 | cgaaaaatttccggtcatgtaaggattatttatttaccgatg | EAD-osc Y164H |

| AB457 | gtggatggaccagctatgacaaagctatagggag | EAD-osc V428Y |

| AB461 | ccgtcgcgctacagctgctattgccgaatgg | MAH-osc W252S_H254Y |

| AB462 | aacatttccggcgtattttactataattgcatgatcacttatgc | MAH-osc N717Y |

| AB484 | gttgccgaggacggcatg | MAH-osc 397-F seq |

| AB485 | ccgtcgcgctacagctgccattgccgaatg | MAH-osc W252S |

| AB492 | ATCCCCGAAAAATTTggGGTTATGTAAGGATTAT | EAD-osc S162W |

| AB493 | ATCCCCGAAAAATTTggGGTCATGTAAGGATTAT | EAD-osc S162W_Y164H |

| AB494 | CAATGAGTGGATTGTTTaATAAAACAACGATGATCTC | EAD-osc Y618N |

Here, seq denotes sequencing primer.

Heterologous Expression.

Expression strains used in this study are listed in Table S7. E. coli DH10B strains harboring three plasmids, a pTrc99a derivative, a pSRKgm derivative, and pJBEI2997 (Addgene plasmid #35151) (33, 46, 47), were cultured at 37 °C, shaking in TB supplemented with chloramphenicol, carbenicillin, and gentamicin until midexponential phase. Expression was induced with 500 µM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 30 h to 40 h at 30 °C, shaking at 225 rpm.

Table S7.

Expression strains

| Expression strain | Strain + plasmids |

| ABB582 | pTrc (pABB276), pSRK-gm-rbs (pABB492) |

| ABB584 | pTrc (pABB276), pSRK-gm-MAH_osc-rbs5 (pABB578) |

| ABB585 | pTrc (pABB276), pSRK-gm-EAD_osc-rbs5 (pABB577) |

| ABB587 | pTrc-sqs (pABB303), pSRK-gm-rbs (pABB492) |

| ABB589 | pTrc-sqs (pABB303), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc (pABB578) |

| ABB590 | pTrc-sqs (pABB303), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc (pABB577) |

| ABB592 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-gm-rbs (pABB492) |

| ABB594 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc (pABB578) |

| ABB595 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc (pABB577) |

| ABB641 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-Y164H_V428Y (pABB624) |

| ABB727 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-Y164H (pABB723) |

| ABB728 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-V428Y (pABB724) |

| ABB653 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-H254Y_Y521V (pABB644) |

| ABB654 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-H254Y (pABB645) |

| ABB684 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-Y521V (pABB663) |

| ABB686 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-W252S_H254Y_Y521V_N717Y (pABB665) |

| ABB735 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-N717Y (pABB730) |

| ABB737 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-H254Y_Y521V_N717Y (pABB732) |

| ABB738 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-W252S_H254Y_Y521V (pABB733) |

| ABB754 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-W252S (pABB744) |

| ABB757 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-MAH-osc-W252S_N717Y (pABB749) |

| ABB782 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-S162W (pABB775) |

| ABB783 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-Y618N (pABB777) |

| ABB784 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-S162S_Y618N (pABB779) |

| ABB785 | pTrc-sqs-synRBS-smo (pABB497), pSRK-rbs5-EAD-osc-S162S_Y164H_V428Y_Y618N (pABB781) |

All expression strains: E. coli DH10B + pJBEI2997 (pABB302, CmR) + a pTrc plasmid (pABB276 and derivatives, AmpR) + a pSRK plasmid (pABB037 and derivatives, GmR). Data source is this study.

Lipid Extraction and Analysis.

Lipids were extracted from cells harvested from 4 mL to 50 mL of bacterial culture using a modified Bligh–Dyer extraction method (48, 49). Cells were first sonicated in 10:5:4 (v:v:v) methanol (MeOH):dichloromethane (DCM):water, and then the phases were separated by mixing with twice the volume of 1:1 (v:v) DCM:water followed by incubation at −20 °C and centrifugation. The organic phase was transferred to a new vial where solvents were evaporated under N2 to yield the total lipid extract (TLE). The alcohol-soluble fractions of some TLEs were further purified by Si column chromatography (50). Lipids were derivatized to either acetate esters with 1:1 (v:v) pyridine:acetic anhydride or to TMS ethers with 1:1 (v:v) bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA):pyridine before analysis by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Further details of the lipid extraction and analysis techniques are described in SI Materials and Methods.

NMR Analysis.

The TLEs were saponified and fractionated by preparative TLC as described in SI Materials and Methods. The triterpenol fraction was further fractionated by reversed-phase HPLC and characterized by NMR using a Bruker Avance III HD with an Ascend 800-MHz magnet and a 5-mm triple resonance inverse (TCI) cryoprobe at 30 °C using deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) as the solvent. Calibration was by the residual solvent signal (7.26 ppm). The relative proportions of the triterpenols were determined by the integrals of the HPLC differential refractometer signal and the integrals of the 1H NMR spectra. Acid-catalyzed isomerization of eudoraenol was carried out in dry CDCl3 using 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) with 1H NMR monitoring as described in SI Materials and Methods. The major product was determined to be boehmerol, by comparison of its 1H NMR spectrum with that of an authentic standard (51). Acid-catalyzed isomerization of isoarborinol [obtained from sorghum (52)] was carried out in dry CDCl3 using 2% (vol/vol) methanesulfonic acid as described in SI Materials and Methods. The products were determined to be adriaticol and an unknown triterpenol in a 2:1 ratio. The unknown triterpenol is likely to be the Δ7 9α-isomer, in analogy to the product of isomerization of lanosterol (53).

Bioinformatics Analysis.

We identified 941 triterpene cyclases, including squalene-hopene cyclases, squalene-tetrahymanol cyclases, and various OSCs using Methylococcus capsulatus Bath OSC (locus tag: MCA2873) to query the JGI Integrated Microbial Genomes & Microbiomes (IMG/M) databases (31) using the basic local alignment search tool for proteins (BLASTP) (54). For phylogenetic analysis of metagenome sequences, we selected only those that were larger than 400 amino acids, for a final total of 851 sequences. Protein sequences were aligned via Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation (MUSCLE) (55) using Geneious (Biomatters Limited) and large gaps were removed from metagenomic sequence alignments using the Gblocks server (56). Maximum likelihood trees were constructed by maximum likelihood (PhyML) (30) using the LG+gamma model, four gamma rate categories, 10 random starting trees, nearest-neighbor interchanges (NNI) branch swapping, and substitution parameters estimated from the data. OSC trees were generated and edited through the interactive tree of life (iTOL) (57), using squalene-hopene cyclases and squalene-tetrahymanol cyclases as the outgroup.

SI Materials and Methods

General Molecular Biology Techniques.

All plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are described in Tables S5 and S6, respectively. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). PCR was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using Taq DNA polymerase or Phusion high-fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs). Plasmid DNA was isolated using the GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Thermo Scientific). DNA fragments used during cloning procedures were purified using the GeneJET gel extraction kit. DNA was sequenced by Elim Biopharmaceuticals.

Plasmid Cloning and Mutagenesis.

Plasmids were constructed by sequence and ligation independent cloning (SLIC), adapted from ref. 45. Briefly, complementary overhangs were created on gel-purified PCR product inserts and a restriction enzyme-linearized vector by incubation with T4 DNA polymerase (EMD Millipore) in the absence of nucleotides followed by annealing and transformation without ligation. Site-directed mutagenesis of plasmids was performed using the Quikchange Lightning Multi kit (Agilent) or by DNA synthesis with 2.5 U PfuUltra II Fusion HS DNA Polymerase (Agilent), one oligonucleotide (0.2 μM) encoding the desired change, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and 50 ng of plasmid DNA in a 25-μL reaction with a 1-min/kb extension time at 68 °C, followed by DpnI digestion. E. coli strains were transformed by electroporation using a MicroPulser Electroporator (BioRad) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Lipid Extraction.

Cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 4,500 × g at 4 °C for 10 min (25 mL to 50 mL of E. adriatica, 4 mL to 20 mL of E. coli), and cell pellets were stored at −20 °C before lipid extraction. Lipids were extracted using a modified Bligh−Dyer extraction method (48, 49). Cells were resuspended in 2 mL of deionized water and transferred to a solvent-washed Teflon centrifuge tube containing 5 mL of methanol and 2.5 mL of DCM, vortexed (30 s) and then sonicated for 1 h in a water bath sonicator; 10 mL of deionized water and 10 mL of DCM were added, and then samples were vortexed and incubated for 1 h to overnight at −20 °C. Samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 2,800 × g at 4 °C, and the organic layer was transferred to a baked glass vial and evaporated under N2. This TLE was stored at −20 °C.

Lipid Purification.

Selected samples were further purified via silica gel column chromatography (49, 50). Briefly, an aliquot of the TLE was loaded onto a ∼1.5-mL packed volume Si Pasteur pipet column and eluted first with hexane (hydrocarbon fraction), then 8:2 (v:v) hexane:DCM (aromatic fraction), then DCM (ketone fraction), and finally 1:1 (v:v) ethyl acetate:DCM (alcohol fraction). C-30 sterols and eudoraenol compounds eluted in the alcohol fraction. E. adriatica typically yielded 40 mg of TLE/liter which was ∼1% triterpenols (0.4 μg/liter). E. coli overexpressing the M. alcaliphilum LAS variant (Fig. 4) typically yielded 148 mg of TLE/liter which was ∼19% triterpenols (28 μg/liter).

Lipid Derivatization.

Before analysis, TLEs, along with 200 ng of cholestanol standard, or alcohol fractions were derivatized to either acetate esters by incubating in 100 μL of 1:1 acetic anhydride:pyridine or to trimetyhlsilylethers by incubating in 50 µL of 1:1 N,O-BSTFA:pyridine for 1 h at 70 °C. Samples were dried under N2 after derivatization and resuspended in 200 μL of DCM.

GC-MS Analysis.

C-30 sterols and arborinol compounds were analyzed via GC-MS. Lipid extracts were separated on an Agilent 7890B Series GC through a 30-m Agilent DB5HT column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.1 μm film thickness) with helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow of 1.0 mL/min and programmed as follows: 100 °C for 4 min, then 20 °C/min to 250 °C and held for 1 min; then 2 °C/min to 280 °C and held for 10 min, and finally 5 °C/min to 330 °C and held for 4 min; 2 μL of each sample was injected in splitless mode at 250 °C. The GC was coupled to a 5977A Series mass-selective detector (MSD) with the ion source at 230 °C and operated at 70 eV in electron ionization (EI) mode scanning from 50 Da to 850 Da in 0.5 s. All lipids except eudoraenol and adriaticol were identified based on their retention time and comparison with previously confirmed laboratory standards, published spectra, and spectra deposited in the American Oil Chemists’ Society Lipid Library (lipidlibrary.aocs.org/index.cfm) and National Institute of Standards and Technology databases. Mass spectra properties [m/z (relative intensity %)] for compounds are as follows:

Eudoraenol: 426 (34, M+), 383 (4), 257 (8), 229 (11), 218 (100), 203 (78), 189 (43), 175 (96), 161 (38), 147 (54), 133 (46), 119 (51), 105 (58), 95 (83), 81 (65), 69 (73), 55 (74).

Eudoraenol acetate: 468 (36, M+), 453 (45), 408 (6), 393 (6), 365 (5), 271 (5), 257 (7), 218 (100), 203 (83), 189 (48), 175 (93), 161 (36), 147 (48), 133 (41), 119 (43), 105 (48), 95 (51), 81 (51), 69 (63), 55 (49).

Eudoraenol TMS ether: 498 (21, M+), 408 (3), 393 (4), 257 (6), 229 (11), 218 (100), 211 (17), 203 (59), 190 (78), 175 (72), 161 (26), 147 (44), 133 (30), 121 (32), 107 (32), 95 (42), 81 (39), 73 (65), 55 (28).

Adriaticol: 426 (42, M+), 411 (80), 393 (19), 273 (16), 259 (99), 241 (64), 229 (19), 215 (12), 199 (12), 173 (17), 159 (21), 137 (42), 109 (51), 95 (85), 81 (76), 69 (92), 55 (100).

Adriaticol acetate: 468 (48, M+), 453 (100), 393 (42), 301 (100), 289 (9), 255 (25), 241 (85), 229 (23), 215 (12), 187 (13), 159 (25), 137 (53), 95 (75), 69 (62), 55 (51).

Adriaticol TMS ether: 498 (23, M+), 483 (19), 393 (44), 331 (16), 255 (22), 241 (67), 229 (15), 215 (8), 189 (12), 159 (16), 143 (37), 131 (47), 119 (27), 107 (45), 93 (53), 81 (72), 73 (100), 55 (33).

NMR Analysis.

The TLEs were saponified by heating with 10% (vol/vol) sodium hydroxide (NaOH)/MeOH at reflux for 16 h. The reaction mixtures were partitioned between water and hexane/ethyl acetate (EtOAc) 2:1; the organic layers were filtered through neutral alumina and concentrated to dryness with a stream of nitrogen. The saponified lipids were fractionated by preparative TLC on glass-backed plates (10 cm in length) coated with a 0.25-mm layer of silica gel 60 F254 using hexane/EtOAc 4:1 as the developing solvent. The triterpenol fraction was further fractionated by reversed-phase HPLC with a system consisting of a Waters 6000A pump, Waters 410 differential refractometer, and two Altex Ultrasphere ODS 5-μm 10 × 250 mm columns in series using a flow rate of 3 mL/min MeOH. After evaporation of the HPLC solvent, the triterpenols were characterized by NMR using a Bruker Avance III HD with an Ascend 800 MHz magnet and a 5-mm TCI cryoprobe at 30 °C using deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) as the solvent. Calibration was by the residual solvent signal (7.26 ppm). The relative proportions of the triterpenols were determined by the integrals of the HPLC differential refractometer signal and the integrals of the 1H NMR spectra.

Acid-catalyzed isomerization of eudoraenol was carried out in dry CDCl3 using 1% TFA with 1H NMR monitoring. After 10 min at 30 °C, only traces of the starting material remained, and the reaction was quenched with 15 mL of d5-pyridine and analyzed using preparative TLC, HPLC, and 1H NMR as described above. The major product was determined to be boehmerol by comparison of its 1H NMR spectrum with that of an authentic standard (51). Acid-catalyzed isomerization of isoarborinol [obtained from sorghum (52)] was carried out in dry CDCl3 using 2% (vol/vol) methanesulfonic acid. After 2.5 h at 40 °C, 66% of the starting material remained, and the reaction was quenched and analyzed as described above. The products were determined to be adriaticol and an unknown triterpenol in a 2:1 ratio. The unknown triterpenol is likely to be the Δ7 9α-isomer, in analogy to the product of isomerization of lanosterol (53). 1H NMR (d, doublet; m, multiplet; s, singlet; t, triplet): 5.306 (m, 1 H); 3.240 (m, 1 H); 1.066 (s, 3 H); 0.991 (s, 3 H); 0.906 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3 H); 0.895 (s, 3 H); 0.884 (s, 3 H); 0.833 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3 H); 0.789 (s, 3 H); and 0.714 (s, 3 H).

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the P.V.W. laboratory and Prof. Roger E. Summons for helpful discussions of this work. This study was supported by National Science Foundation Grants EAR-1451767 (to P.V.W.) and OCE-1061957 (to J.L.G.). The acquisition of the 800-MHz NMR spectrometer was made possible by National Institutes of Health Grant S10 OD012254.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617231114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Volkman JK. Sterols and other triterpenoids: Source specificity and evolution of biosynthetic pathways. Org Geochem. 2005;36(2):139–159. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks LW, Casey WM. Physiological implications of sterol biosynthesis in yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:95–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu F, et al. Dual roles for cholesterol in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(41):14551–14556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503590102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Cholesterol feedback: From Schoenheimer’s bottle to Scap’s MELADL. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S15–S27. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800054-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thimmappa R, Geisler K, Louveau T, O’Maille P, Osbourn A. Triterpene biosynthesis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65(65):225–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue Z, et al. Divergent evolution of oxidosqualene cyclases in plants. New Phytol. 2012;193(4):1022–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eschenmoser A, Arigoni D. Revisited after 50 years: The stereochemical interpretation of the biogenetic isoprene rule for the triterpenes. Helv Chim Acta. 2005;88(12):3011–3050. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei JH, Yin X, Welander PV. Sterol synthesis in diverse bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2016;7(990):990. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kannenberg EL, Poralla K. Hopanoid biosynthesis and function in bacteria. Naturwissenschaften. 1999;86(4):168–176. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sáenz JP, et al. Hopanoids as functional analogues of cholesterol in bacterial membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(38):11971–11976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515607112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abe I. Enzymatic synthesis of cyclic triterpenes. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24(6):1311–1331. doi: 10.1039/b616857b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Summons RS, Lincoln SA. Biomarkers: Informative molecules for studies in geobiology. In: Knoll AH, Canfield DE, Konhauser KO, editors. Fundamentals of Geobiology. 1st Ed. Blackwell; West Sussex, UK: 2012. pp. 269–296. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters KE, Waters CC, Moldowan JM. 2007. Biomarkers and Isotopes in Petroleum Exploration and Earth History, The Biomarker Guide (Cambridge Univ Press, Cambridge, UK), Vol 2.

- 14.Hemmers H, Gulz PG, Marner FJ, Wray V. Pentacyclic triterpenoids in epicuticular waxes from Euphorbia lathyris L, Euphorbiaceae. Z Naturforsch C. 1989;44(3-4):193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohmoto T, Nikaido T, Nakadai K, Tohyama E. [Studies on the triterpenoids and the related compounds from gramineae plants. VII] Yakugaku Zasshi. 1970;90(3):390–393. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.90.3_390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vorbrueggen H, Djerassi C, Pakrashi SC. Arborinol, ein neuer triterpen-typus. Ann Chem Justus Liebig. 1963;668(1):57–76. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauke V, et al. Novel triterpene derived hydrocarbons of arborane fernane series in sediments: Part I. Tetrahedron. 1992;48(19):3915–3924. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauke V, et al. Novel triterpene derived hydrocarbons of the arborane fernane series in sediments: Part II. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1992;56(9):3595–3602. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauke V, et al. Isoarborinol through geological times: Evidence for its presence in the Permian and Triassic. Org Geochem. 1995;23(1):91–93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaffe R, Hausmann KB. Origin and early diagenesis of arborinone isoarborinol in sediments of a highly productive fresh water lake. Org Geochem. 1995;22(1):231–235. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ourisson G, Albrecht P, Rohmer M. Predictive microbial biochemistry—From molecular fossils to procaryotic membranes. Trends Biochem Sci. 1982;7(7):236–239. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siedenburg G, Jendrossek D. Squalene-hopene cyclases. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(12):3905–3915. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00300-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer WW, Pearson A. Hypotheses for the origin and early evolution of triterpenoid cyclases. Geobiology. 2007;5(1):19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2007.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoshino T, Sato T. Squalene-hopene cyclase: Catalytic mechanism and substrate recognition. Chem Commun (Camb) 2002;(4):291–301. doi: 10.1039/b108995c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summons RE, Bradley AS, Jahnke LL, Waldbauer JR. Steroids, triterpenoids and molecular oxygen. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1470):951–968. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alain K, Intertaglia L, Catala P, Lebaron P. Eudoraea adriatica gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel marine bacterium of the family Flavobacteriaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58(Pt 10):2275–2281. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villanueva L, Rijpstra WI, Schouten S, Damsté JS. Genetic biomarkers of the sterol-biosynthetic pathway in microalgae. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2014;6(1):35–44. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Budzikiewicz H, Wilson JM, Djerassi C. Mass spectrometry in structural and stereochemical problems 32. Pentacyclic triterpenes. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85(22):3688–3699. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oyarzun ML, Garbarino JA, Gambaro V, Guilhem J, Pascard C. Two triterpenoids from Boehmeria excelsa. Phytochemistry. 1987;26(1):221–223. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52(5):696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen IM, et al. Supporting community annotation and user collaboration in the integrated microbial genomes (IMG) system. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:307. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2629-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banta AB, Wei JH, Welander PV. A distinct pathway for tetrahymanol synthesis in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(44):13478–13483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511482112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peralta-Yahya PP, et al. Identification and microbial production of a terpene-based advanced biofuel. Nat Commun. 2011;2:483. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoma R, et al. Insight into steroid scaffold formation from the structure of human oxidosqualene cyclase. Nature. 2004;432(7013):118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature02993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abe I. The oxidosqualen cyclases: One substrate, diverse products. In: Osbourn A, Goss RJ, Carter GT, editors. Natural Products: Discourse, Diversity and Design. Wiley Blackwell; Oxford: 2014. pp. 297–315. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu TK, Chang CH. Enzymatic formation of multiple triterpenes by mutation of tyrosine 510 of the oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ChemBioChem. 2004;5(12):1712–1715. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lodeiro S, Wilson WK, Shan H, Matsuda SP. A putative precursor of isomalabaricane triterpenoids from lanosterol synthase mutants. Org Lett. 2006;8(3):439–442. doi: 10.1021/ol052725j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu TK, Liu YT, Chang CH, Yu MT, Wang HJ. Site-saturated mutagenesis of histidine 234 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase demonstrates dual functions in cyclization and rearrangement reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(19):6414–6419. doi: 10.1021/ja058782p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newman DK, Neubauer C, Ricci JN, Wu CH, Pearson A. Cellular and molecular biological approaches to interpreting ancient biomarkers. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2016;44(44):493–522. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson A, Budin M, Brocks JJ. Phylogenetic and biochemical evidence for sterol synthesis in the bacterium Gemmata obscuriglobus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(26):15352–15357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536559100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimura M, Kushiro T, Shibuya M, Ebizuka Y, Abe I. Protostadienol synthase from Aspergillus fumigatus: Functional conversion into lanosterol synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391(1):899–902. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lodeiro S, Segura MJ, Stahl M, Schulz-Gasch T, Matsuda SP. Oxidosqualene cyclase second-sphere residues profoundly influence the product profile. Chem BioChem. 2004;5(11):1581–1585. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer MM, Xu R, Matsuda SP. Directed evolution to generate cycloartenol synthase mutants that produce lanosterol. Org Lett. 2002;4(8):1395–1398. doi: 10.1021/ol0257225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salmon M, et al. A conserved amino acid residue critical for product and substrate specificity in plant triterpene synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(30):E4407–E4414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605509113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li MZ, Elledge SJ. SLIC: A method for sequence- and ligation-independent cloning. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;852:51–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-564-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan SR, Gaines J, Roop RM, 2nd, Farrand SK. Broad-host-range expression vectors with tightly regulated promoters and their use to examine the influence of TraR and TraM expression on Ti plasmid quorum sensing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(16):5053–5062. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01098-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amann E, Ochs B, Abel KJ. Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;69(2):301–315. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37(8):911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welander PV, et al. Identification and characterization of Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 hopanoid biosynthesis mutants. Geobiology. 2012;10(2):163–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2011.00314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Summons RE, et al. Lipid biomarkers in ooids from different locations and ages: Evidence for a common bacterial flora. Geobiology. 2013;11(5):420–436. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Son KC, Severson RF, Arrendale RF, Kays SJ. Isolation and characterization of pentacyclic triterpene ovipositional stimulant for the sweet potato weevil from Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38(1):134–137. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nes WD, Wong RY, Griffin JF, Duax WL. On the structure, biosynthesis, function and phylogeny of isoarborinol and motiol. Lipids. 1991;26(8):649–655. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaylor JL, Delwiche CV, Swindell AC. Enzymatic isomerization (Delta(8)- Delta(7)) of intermediates of sterol biosynthesis. Steroids. 1966;8(3):353–363. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(4):540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: An online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(Web server issue):gkw290. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]