Abstract

Importance

Drug coupons are widely used, but their effects are not well understood.

Objective

To quantify the effect of coupons on statin use and expenditures

Design

Retrospective cohort analysis of IMS Health LRx LifeLink database

Setting

U.S. retail pharmacy transactions

Participants

Incident statin users who initiated branded atorvastatin or rosuvastatin between June 2006 and February 2013

Main Outcomes and Measures

Monthly statin utilization [pill-days of therapy], switching [filling a different statin], termination [failure to refill statin for 6 months], and out-of-pocket and total costs

Results

Of 1.1 million incident atorvastatin and rosuvastatin users, 2% used a coupon for at least one statin fill. At one year, compared to non-coupon users, those who used a statin coupon on their first fill were dispensed an equal number of monthly pill-days (23.7 vs. 23.8), were less likely to switch statins (14.4 vs. 16.3%), and were less likely to have terminated statin therapy (31.3 vs. 39.2%). At 4 years, coupon users were more likely to have switched (45.5 vs. 40.8%) and less likely to have terminated statin therapy (50.6 vs. 61.1%) compared to non-coupon users. Those who used greater numbers of coupons were substantially less likely to switch and terminate statin therapies. Monthly out-of-pocket costs were lower among coupon than non-coupon users at 1 year ($9.7 vs. $15.1), but total monthly costs were qualitatively similar ($115.5 vs. $116.9). At 4 years, monthly out-of-pocket costs among coupon users remained lower ($14.3 vs. $16.6) compared to non-coupon users. Sensitivity analyses supported the main results.

Conclusions

Coupons for branded statins are associated with higher utilization and lower rates of discontinuation and short-term switching to other statin products.

INTRODUCTION

Although 86% of prescriptions filled in the United States in 2013 were generics, payers and patients spent $232 billion on branded medications, accounting for 71% of all prescription drug costs.1 Pharmaceutical companies employ a variety of promotional strategies to encourage the use of these single-source branded medications. One such strategy is the use of drug coupons, which are widely available at physicians’ offices and on the Internet, and can be used to decrease patient copays for certain medications.2,3 Between 2009 to 2011, the number of coupons offered in the United States increased 260% and approximately 11% to 13% of branded prescriptions were associated with a copay coupon.4

Debate surrounding the appropriateness and “moral hazard”5 of coupons mirrors that of other promotional activities, such as direct-to-consumer advertising6,7 and the use of free samples.8 Proponents argue that coupons lower patients’ out-of-pocket costs, reduce cost-related nonadherence, and provide a safer alternative to drug samples by requiring dispensing through licensed pharmacists.3,9 Opponents argue that coupons incentivize patients to initiate and adhere to expensive branded therapies, increasing out-of-pocket and third party spending that ultimately drives higher premiums for coupon-users and non-users alike.3,9,10,11

Despite their increasing prevalence, there is remarkably little evidence regarding the effect of coupons on prescription drug utilization or expenditures. One retrospective cohort study used commercial pharmacy claims from incident statin patients to examine the impact of coupons on brand-name statin utilization and spending. The authors found that coupon users had higher rates of adherence and substantially higher total statin costs than those who initiated generic statins.3,9 Despite these insights, the authors only examined prescription fills, restricted their follow-up to a single observation at 12 months, and used a cross-sectional study design that limited causal inference.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing the effect of coupon use on utilization and expenditures among incident statin-users. We focused on statins because the indications for statin use consist of prevalent and costly chronic conditions, and because there are multiple statins on the market, some of which have been heavily marketed and promoted with drug coupons.

METHODS

We examined data from used the IMS Health LifeLink™ LRx Anonymized Longitudinal Prescription database, consisting of prescriptions from retail, food store, independent, and mass merchandiser pharmacies, all of which represent approximately two-thirds of retail prescriptions dispensed in the United States.12 These data include detailed information about the quantity, form, and dose of medications dispensed as well as annual flags to indicate individuals who utilized a mail-order pharmacy. The data are generated on a daily basis at pharmacies and are then automatically transmitted to IMS Health through weekly feeds. The prescription data are also linked to the above-noted database using a patented algorithm based on 16 different fields such as the patient’s first name, last name, and date of birth. Each prescription claim contains information about the retail transaction (days supply, number of refills), patient (year of birth, sex), product (National Drug Code [NDC]), and the payer and prescription drug plan. We used payer and plan variables to identify statin claims associated with copay coupons.

Setting and Participants

We derived a closed cohort of incident statin users from a larger extract that contained all prescriptions from January 2006 through August 2013 for any patient who filled two or more prescriptions for an opioid in one of eleven states over any 1-year period during that time. This extract, derived for a separate study, consisted of 5.3 billion retail transactions from more than 50 million patients, 1.5 million prescribers and 52,000 pharmacies.

Participants were incident statin users, defined by evidence of no prior statin use for at least a 6-month period with evidence of other prescription claims activity, who initiated branded atorvastatin or rosuvastatin. Medicare and Medicaid prohibit coupon use, so we excluded individuals over the age of 65 or who otherwise used Medicaid or Medicare. We categorized patients into four mutually exclusive groups: (1) coupon used on first statin fill (initial coupon users); (2) coupon used on statin fill, but not the first (subsequent coupon users); (3) coupon used on non-statin fills (other coupon users); or (4) no coupons used (non-coupon users). Our final dataset included approximately 700,000 coupons for atorvastatin (82%) or rosuvastatin (18%), which together accounted for 87% of all statin coupons observed.

To account for potential differences between early and late coupon adopters, we excluded individuals who used a coupon for either statin before coupons were widely available for that drug, which we defined as the use of a coupon for at least 0.1% of all commercial claims for a given drug during a particular month. For our primary analyses, we included only individuals who used pharmacies that consistently reported data to IMS throughout the study period and who filled at least one prescription for any drug within the first and last 6 months of the study period.

Measures

We examined three measures of utilization and two measures of cost. First, we calculated the quantity of a prescription medicine sufficient for one day of therapy (pill-day) and then examined the average monthly number of pill-days supplied. We allowed for unlimited “stockpiling”13 and thus accounted for inherent differences in prescription quantity across different pharmacy claims. Second, we calculated switching as the probability of switching statins from one month to the next. Third, we calculated the proportion of people who terminated therapy, defined as a 6-month period without any statin utilization. Fourth, we calculated the average monthly out-of-pocket costs for statins, reflecting the amount of co-insurance the payer determined is owed by the patient for the transaction, based on an individual’s benefit design. These values represent the patient’s out-of-pocket costs after any discount from a coupon was applied. Finally, we quantified patients’ total costs for statins (the copay plus the amount billed to insurance, i.e., what the pharmacy is paid from all sources). We excluded claims with missing cost information from our analyses that examined out-of-pocket and total costs.

In some cases, individuals had multiple statin transactions during a given month that made it difficult to easily assign patients to a particular statin therapy. In our main analyses, we dropped individuals who could not be assigned to a single statin therapy based on either the plurality of their claims in a given month or by comparison of their current month’s use to their use during the prior or subsequent month.

Statistical Analysis

We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) models, accounting for within-subject correlations over time to calculate the predicted and marginal effects of coupon use between coupon users in each group and their counterfactual non-coupon counterparts. We used the number of months contributed by each person included in the cohort (i.e. person-months) as our unit of analysis. We controlled for the age and sex of individual respondents and included flexible specifications for time on drug, measured in months, and controlled for the year and month that therapy was initiated. Our data did not include diagnoses, so we controlled for differences in patient comorbidities using the Chronic Disease Score, a method of quantifying comorbid burden using automated pharmacy claims that has been validated as a measure of hospitalizations, expenditures, and mortality.14 In order to allow the effect of time on drug to vary with initial coupon status, we included interactions between a cubic spline with five knots in time on drug and coupon utilization of the individual.15 To calculate the effect of coupons, we included dummy variables for coupon utilization, which indicate whether a coupon was used that month.

We modeled the number of pills dispensed in a given month using a negative binomial specification; out-of-pocket costs, pharmacy costs, and monthly pill utilization were modeled using a Poisson distribution. In most analyses, we estimated GEE models with exchangeable correlation matrices. However, in our constant store sample it was necessary to assume independence between observations in order for the model to converge. We used GEE logistic regression, which allows for within subject correlation over time, to examine the effects of drug coupons on switching and termination. In order to interpret the results of our models, we used “recycled predictions” to construct a synthetic comparison group for each of our three coupon categories15,16 and computed the predicted value for each person-month in each group. This approach provides a method of standardizing the average predicted values over the distribution of other covariates. We then computed average marginal differences as the average difference between the coupon group predicted values and the comparison group predicted values. We computed standard errors for average predicted values and marginal differences using the delta method from cluster-robust variance matrices.17 All models were estimated using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, because we limited our primary analyses to a closed cohort of individuals, we repeated our analyses, allowing subjects to enter and leave the cohort. Second, since our data do not capture mail-order medications, we repeated our analyses excluding individuals who filled any prescriptions by mail order during the analysis period. Third, since our original extract oversampled opioid users, we repeated our analyses after limiting them to individuals who had no opioid prescription fills from incident statin use until termination or censoring. Fourth, we varied rules that allowed for unlimited stockpiling, allowing patients to stockpile fewer pills from one prescription to a subsequent prescription. Fifth, we varied our definition of statin termination to include those with no statin fills for 3 months or 9 months.

RESULTS

Characteristics of coupon and non-coupon users

Our final sample consisted of approximately 1.1 million incident atorvastatin (66%) and rosuvastatin (34%) users. Of these, 7,839 (.7%) used a coupon on their first statin fill, 12,864 (1.2%) used a coupon on a subsequent statin fill, 11,473 (1.1%) used a coupon for a non-statin product, and approximately 1 million patients (97%) filled a prescription for an incident statin without any associated coupon use (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of coupon users and non-users prior to initiating atorvastatin or rosuvastatin therapy*

| Coupon Users | Non-users | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Incident statin coupon | Subsequent statin coupon | Incident non-statin coupon | No coupon use | |

| Female, % | 55 | 54 | 54 | 57 |

|

| ||||

| Age, mean, median, (IQR) | 49, 51 (11) | 50, 52 (11) | 48, 49 (12) | 50, 51 (11) |

|

| ||||

| Insurance status,% | ||||

| Commercially insured | 96 | 96 | 94 | 89 |

| None/Cash | 4 | 4 | 6 | 11 |

|

| ||||

| Number of unique prescribers**, mean, median (IQR) | 4, 3 (3) | 4, 3 (3) | 5, 4 (4) | 4, 3 (3) |

|

| ||||

| Number of unique pharmacies**, mean, median (IQR) | 2, 1 (1) | 2, 1 (1) | 2,1 (2) | 2, 1 (1) |

|

| ||||

| Drug utilization | ||||

| Prescriptions**, mean, median (IQR) | 22, 18 (18) | 27, 22 (24) | 30, 23 (27) | 26, 21 (24) |

|

| ||||

| Coupon use | ||||

| Coupons used prior to first statin**, mean, median (IQR) | 1, 0 (0) | 0, 0 (0) | 1, 0 (1) | --- |

|

| ||||

| Unique therapeutic classes**, mean, median (IQR) | 8, 7 (6) | 9, 8 (7) | 10, 8 (8) | 9, 8 (7) |

|

| ||||

| Chronic disease score**, mean, median (IQR) | 2, 2 (2) | 2, 2 (2) | 2, 2 (2) | 2, 2 (2) |

|

| ||||

| Costs | ||||

| Total copay**, mean, median (IQR) | 249, 86 (345) | 227, 96 (285) | 2134, 110 (354) | 246, 88 (283) |

| Total cost**, mean, median (IQR) | 2422, 1530 (2302) | 2905, 1876 (2824) | 3760, 2354 (3773) | 2864, 1698 (2859) |

|

| ||||

| Total Patients, N | 7839 | 12864 | 11473 | 1018739 |

values represent column percents unless otherwise noted

based on claims filled 6 months prior to incident statin fill date

Source: IMS Health Lifelink LRx Data, 2007–2013

Overall, coupon and non-coupon users had similar demographic characteristics, prescription drug utilization, and comorbid conditions. Coupon users were significantly more likely to fill claims through an insurer (96% initial coupon users vs. 89% non-coupon users; p<.05), and other coupon users had significantly higher median copays ($110 vs. $88; p<.05) and total pharmacy costs ($2354 vs. $1698; p<.05) than non-coupon users.

Appendix Figure 1 depicts trends in branded and generic atorvastatin dispensing during the study period among coupon users and non-users. In January 2007, there were approximately 223,000 branded prescription transactions without a coupon and a negligible number of branded sales where a coupon was used. Branded sales remained relatively flat until May 2012, when generic atorvastatin was released. This was associated with a reduction of approximately 95% in branded sales and 75% reduction in coupon use over the ensuing 15 months as the generic product took hold. A similar trend for rosuvastatin is shown in Appendix Figure 2, although a generic formulation of the product was not introduced during the study period.

Effect of coupons on statin utilization, switching and termination

Table 2 depicts differences in utilization, switching, and termination between coupon users on atorvastatin or rosuvastatin and their counterfactual non-coupon counterparts within each group (initial, subsequent, non-statin). Overall, coupon users had similar levels of statin utilization and switching compared to their non-coupon users. At 1 year, initial coupon users were dispensed 0.1 fewer average pill days per month, were 1.9% less likely to switch statins (16.6 vs. 18.9%; p<.05), and were 6.9% less likely to terminate statin therapy (31.3 vs. 39.2%; p<.001) than non-coupon users. Differences in termination amplified over time; at 4 years, initial coupon users were 11.1% less likely to terminate statin therapy than non-coupon users (50.6 vs. 60.7%; p<.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences in average monthly atorvastatin and rosuvastatin utilization among coupon users and non-users.*

| Time following incident statin fill | Time

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 1 year | 2 years | 3 years | 4 years | |

| Statin Utilization (Average pill-days dispensed) | |||||

|

| |||||

| No coupons | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 29.1 (0.0) | 23.7 (0.0) | 24.5 (0.0) | 24.7 (0.0) | 25.4 (−0.1) |

|

| |||||

| Other coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 28.3 (−0.1) | 23.7 (−1.2) | 24.7 (−2.8) | 24.9 (−4.4) | 25.2 (−6.1) |

| Difference from counterfactual** | −0.7 (−0.1) | 0.1 (−1.2) | 0.2 (−2.8) | 0.2 (−4.4) | −0.1 (−6.1) |

|

| |||||

| Initial statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 28.4 (−0.2) | 23.8 (−3.0) | 24.3 (−6.7) | 24.7 (−10.5) | 24.7 (−14.3) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −0.8 (−0.2) | −0.1 (−3.0) | −0.4 (−6.7) | 0.0 (−10.5) | −0.6 (−14.3) |

|

| |||||

| Subsequent statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 26.7 (−0.1) | 24.0 (−2.1) | 24.5 (−4.6) | 24.8 (−7.2) | 25.1 (−9.9) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −2.2 (−0.1) | 0.3 (−2.1) | −0.2 (−4.6) | 0.0 (−7.2) | −0.4 (−9.9) |

|

| |||||

| Statin Switching (Cumulative probability of switching from one statin to another) | |||||

|

| |||||

| No coupons | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 1.5 (0.0) | 16.6 (−0.1) | 27.4 (−0.2) | 35.6 (−0.3) | 42.8 (−0.4) |

|

| |||||

| Other coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 1.9 (−0.1) | 18.9 (−0.4) | 31.5 (−0.7) | 42.3 (−1.0) | 51.4 (−1.2) |

| Difference from counterfactual | 0.3 (−0.1) | 1.9 (−0.5) | 3.6 (−0.7) | 5.9 (−1.0) | 7.7 (−1.3) |

|

| |||||

| Initial statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 1.4 (−0.2) | 14.4 (−0.9) | 25.5 (−1.8) | 36.0 (−3.5) | 45.5 (−5.6) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −0.1 (−0.2) | −1.9 (−1.0) | −1.1 (−1.8) | 1.8 (−3.5) | 4.7 (−5.6) |

|

| |||||

| Subsequent statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 1.4 (−0.2) | 15.6 (−0.8) | 28.3 (−1.1) | 39.3 (−1.4) | 48.8 (−1.6) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −0.2 (−0.2) | −1.4 (−0.8) | 0.6 (−1.1) | 3.4 (−1.4) | 5.6 (−1.7) |

|

| |||||

| Statin Termination (Cumulative Probability of failure to refill for period of at least 6 months) | |||||

|

| |||||

| No coupons | |||||

| Predicted level, percent terminating (SE) | 12.0 (−0.1) | 39.2 (−0.1) | 50.8 (−0.2) | 56.3 (−0.2) | 60.7 (−0.2) |

|

| |||||

| Other coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, percent terminating (SE) | 2.3 (−0.1) | 14.9 (−0.3) | 24.1 (−0.4) | 30.2 (−0.5) | 35.9 (−0.6) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −9.9 (−0.1) | −25.1 (−0.4) | −27.6 (−0.5) | −27.0 (−0.5) | −25.7 (−0.6) |

|

| |||||

| Initial statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, percent terminating (SE) | 8.2 (−0.5) | 31.3 (−1.0) | 41.8 (−1.3) | 46.3 (−1.6) | 50.6 (−2.1) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −3.5 (−0.5) | −6.9 (−1.1) | −8.7 (−1.3) | −9.9 (−1.6) | −10.5 (−2.1) |

|

| |||||

| Subsequent statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level, percent terminating (SE) | 0.4 (−0.1) | 8.3 (−0.5) | 15.1 (−0.6) | 20.7 (−0.8) | 25.9 (−1.0) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −11.6 (−0.1) | −30.6 (−0.5) | −35.2 (−0.7) | −34.9 (−0.8) | −33.9 (−1.0) |

Values represent 12-month averages at varying duration of follow-up;

Difference from counterfactual represents the difference in average predicted values between coupon users and their counterfactual non-coupon using counterparts within each group (initial, subsequent, non-statin);

Source: IMS Health Lifelink LRx Data, 2007–2013

Compared to initial coupon users, the association between coupon use and statin utilization and switching was similar for subsequent and other coupon users. However, both subsequent and other coupon users were less likely to terminate statin therapy than initial coupon users: at 2 years, subsequent coupon users were 35.2% less likely to terminate statin therapy than non-users (15.1 vs. 50.8%; p<.0001), whereas initial coupon users were 8.7% less likely to terminate treatment (41.8 vs. 50.8%; p<.0001). These patterns continued to persist through 4 years of follow up.

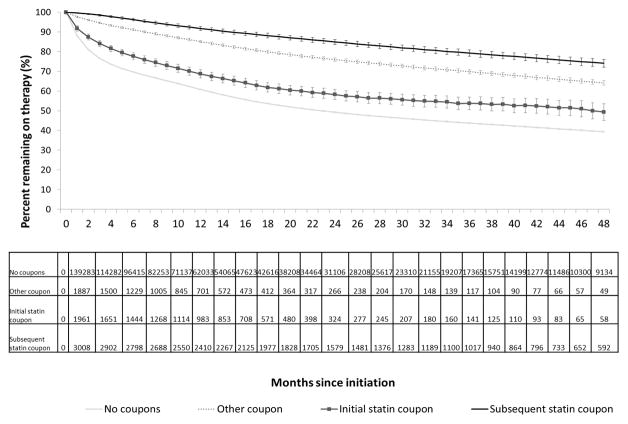

The cumulative probability of statin termination over time among the four groups is shown in Figure 3. Rates of discontinuation were greatest for non-coupon users. The length of time until a discontinuation rate of 25% was 10 months for initial coupon users (95% CI: 9–10 months), 35 months for subsequent statin coupon users (95% CI: 33–37 months), 23 months for other coupon users (95% CI: 23–24), and 7 months for non-coupon users (95% CI: 7–7).

Effect of varying levels of coupon utilization

Higher levels of coupon use resulted in higher utilization and a lower probability of switching and termination (Table 3). For example, at 3 years, initial coupon users were 5.2% more likely to switch and 0.6% more likely to terminate than non-coupon users. However, at 3 years, incident statin users who used coupons for five or more fills were 16% less likely to switch and 28% less likely to terminate than non-coupon users.

Table 3.

Association Between Coupons and Utilization Among Incident Statin Coupon Users.

| Time following incident statin fill | Time

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 1 year** | 2 years** | 3 years** | 4 years** | |

| Statin Utilization (Average pill-days dispensed) | |||||

|

| |||||

| No coupons | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 26.5 (0.0) | 23.7 (0.0) | 24.5 (0.0) | 24.7 (0.0) | 25.4 (−0.1) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use on first fill only | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 24.0 (−0.2) | 23.0 (−4.0) | 23.4 (−8.9) | 23.6 (−13.8) | 24.6 (−19.5) |

| Difference from counterfactual* | −2.5 (−0.3) | −0.9 (−4.0) | −1.1 (−8.9) | −1.0 (−13.8) | −0.6 (−19.5) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for two fills | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 26.3 (−0.3) | 24.5 (−6.6) | 24.3 (−14.0) | 24.1 (−21.4) | 24.3 (−29.5) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −0.6 (−0.3) | 0.4 (−6.6) | −0.3 (−14.0) | −0.5 (−21.4) | −0.8 (−29.5) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for three or four fills | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 29.1 (−0.2) | 23.6 (−3.8) | 23.6 (−8.1) | 25.7 (−13.8) | 30.5 (−22.9) |

| Difference from counterfactual | 2.1 (−0.2) | −0.6 (−3.9) | −1.2 (−8.1) | 0.8 (−13.8) | 4.2 (−22.9) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for five or more fills | |||||

| Predicted level, pill-days (SE) | 30.1 (−0.1) | 25.7 (−3.3) | 26.8 (−7.2) | 27.1 (−11.3) | 26.3 (−14.9) |

| Difference from counterfactual | 3.1 (−0.1) | 1.5 (−3.3) | 1.8 (−7.2) | 2.2 (−11.3) | 0.9 (−14.9) |

|

| |||||

| Statin Switching (Cumulative probability of switching from one statin to another) | |||||

|

| |||||

| No coupons | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 3.0 (0.0) | 16.7 (−0.1) | 27.4 (−0.2) | 35.8 (−0.3) | 43.0 (−0.4) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use on first fill only | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 5.2 (−0.6) | 18.8 (−1.5) | 30.6 (−2.7) | 39.8 (−5.0) | 48.3 (−7.5) |

| Difference from counterfactual | 2.2 (−0.6) | 2.5 (−1.5) | 3.8 (−2.7) | 5.2 (−5.0) | 7.1 (−7.5) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for two fills | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 2.3 (−0.8) | 11.7 (−2.5) | 20.8 (−4.3) | 35.5 (−6.2) | 38.0 (−7.2) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −0.7 (−0.8) | −4.5 (−2.5) | −5.6 (−4.3) | 1.9 (−6.2) | −2.4 (−7.2) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for three or four fills | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 0.7 (−0.3) | 14.2 (−2.2) | 26.4 (−4.2) | 40.4 (−7.1) | 46.9 (−12.2) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −2.3 (−0.3) | −2.2 (−2.2) | −0.6 (−4.3) | 6.5 (−7.1) | 8.8 (−12.1) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for five or more fills | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 0.0 (0.0) | 4.7 (−1.3) | 13.5 (−2.8) | 18.2 (−4.2) | 18.3 (−4.3) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −2.9 (−0.1) | −11.3 (−1.3) | −13.1 (−2.8) | −15.5 (−4.2) | −22.2 (−4.3) |

|

| |||||

| Statin Termination (Cumulative Probability of failure to refill for period of at least 6 months) | |||||

|

| |||||

| No coupons | |||||

| Predicted level, percent terminating (SE) | 19.1 (−0.1) | 39.2 (−0.1) | 50.9 (−0.2) | 56.4 (−0.2) | 60.9 (−0.2) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use on first fill only | |||||

| Predicted level, percent terminating (SE) | 19.9 (−1.1) | 39.6 (−1.4) | 51.9 (−1.7) | 57.0 (−1.9) | 62.2 (−2.2) |

| Difference from counterfactual | 1.1 (−1.1) | 1.0 (−1.5) | 1.0 (−1.7) | 0.6 (−1.9) | 0.9 (−2.2) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for two fills | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 8.9 (−1.4) | 33.9 (−3.1) | 45.7 (−3.9) | 52.9 (−5.0) | 61.2 (−6.2) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −9.5 (−1.4) | −3.9 (−3.1) | −4.8 (−3.9) | −3.7 (−5.0) | −0.2 (−6.2) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for three or four fills | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 2.9 (−0.6) | 24.6 (−2.5) | 35.4 (−3.4) | 45.3 (−5.1) | 54.0 (−14.7) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −15.3 (−0.6) | −13.1 (−2.5) | −15.0 (−3.4) | −10.6 (−5.1) | −0.3 (−14.7) |

|

| |||||

| Coupon use for five or more fills | |||||

| Predicted level, percent switching (SE) | 0.0 (0.0) | 10.4 (−1.7) | 20.4 (−2.8) | 27.2 (−4.3) | 30.2 (−5.9) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −17.9 (−0.1) | −26.8 (−1.7) | −28.7 (−2.8) | −27.9 (−4.3) | −29.2 (−5.9) |

Difference from counterfactual represents the difference in average predicted values between coupon users and their counterfactual non-coupon using counterparts within each group (initial, subsequent, non-statin).

Source: IMS Health Lifelink LRx Data, 2007–2013

Effect of coupon use on out-of-pocket and total costs

All coupon users had consistently lower out-of-pocket costs than non-coupon users (Table 4). At one year, average monthly out-of-pocket costs for statins appeared $5 lower for initial coupon users than for non-coupon users; however, this difference was not statistically significant ($9.7 vs. $15.9, NS). Between 2 and 4 years of follow-up, this difference persisted, ranging from $2–$6.

Table 4.

Differences in average monthly atorvastatin and rosuvastatin expenditures between coupon and non-coupon users.

| Time following incident statin fill | Time

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 1 year | 2 years | 3 years | 4 years | |

| Average Copayment, $ | |||||

|

| |||||

| No coupons | |||||

| Predicted level (SE) | 19.4 (−0.1) | 15.9 (−0.1) | 17.0 (−0.1) | 16.1 (−0.1) | 15.2 (−0.2) |

|

| |||||

| Other coupon | |||||

| Predicted level (SE) | 16.1 (−0.2) | 13.0 (−3.0) | 13.4 (−6.7) | 12.6 (−9.7) | 12.1 (−12.6) |

| Difference from counterfactual* | −3.4 (−0.1) | −2.9 (−3.0) | −3.6 (−6.7) | −3.4 (−9.7) | −3.1 (−12.6) |

|

| |||||

| Initial statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level (SE) | 16.4 (−1.7) | 9.7 (−10.2) | 11.0 (−25.8) | 14.3 (−51.6) | 14.3 (−70.0) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −2.9 (−1.7) | −5.4 (−10.2) | −6.1 (−25.8) | −2.8 (−51.6) | −2.3 (−70.0) |

|

| |||||

| Subsequent statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level (SE) | 12.9 (−0.3) | 14.7 (−11.0) | 15.6 (−25.3) | 14.6 (−36.6) | 12.2 (−41.6) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −7.6 (−0.3) | −1.3 (−11.0) | −1.4 (−25.3) | −1.6 (−36.6) | −3.1 (−41.6) |

|

| |||||

| Average Total Cost, $ | |||||

|

| |||||

| No coupons | |||||

| Predicted level (SE) | 128.4 (−0.1) | 104.6 (−0.2) | 112.4 (−0.2) | 115.9 (−0.2) | 121.4 (−0.4) |

|

| |||||

| Other coupon | |||||

| Predicted level (SE) | 127.3 (−0.3) | 106.7 (−6.2) | 114.9 (−14.5) | 118.2 (−23.0) | 121.6 (−32.0) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −2.5 (−0.3) | 1.3 (−6.2) | 1.7 (−14.5) | 1.9 (−23.0) | 0.0 (−32.0) |

|

| |||||

| Initial statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level (SE) | 143.3 (−1.3) | 115.5 (−14.9) | 117.3 (−32.7) | 121.8 (−52.5) | 123.7 (−72.3) |

| Difference from counterfactual | 6.8 (−1.2) | 1.4 (−14.9) | −2.6 (−32.7) | 0.5 (−52.5) | −1.5 (−72.3) |

|

| |||||

| Subsequent statin coupon | |||||

| Predicted level (SE) | 118.1 (−0.4) | 109.6 (−10.1) | 115.6 (−23.3) | 121.1 (−37.6) | 125.1 (−52.5) |

| Difference from counterfactual | −9.9 (−0.3) | 3.6 (−10.1) | 1.6 (−23.3) | 3.7 (−37.6) | 2.6 (−52.5) |

Difference from counterfactual represents the difference in average predicted values between coupon users and their counterfactual non-coupon using counterparts within each group (initial, subsequent, non-statin)

Source: IMS Health Lifelink LRx Data, 2007–2013

The association between coupon use and total costs differed from those for out-of-pocket costs. Overall, there were negligible differences in monthly average total costs between coupon users and non-coupon users. At 1 month, total costs were approximately $7 higher for initial coupon users compared to their non-coupon users ($143.3 vs. $136.5, p<0.001). However, for longer periods of follow-up, this difference decreased and total costs for initial coupon users were very similar to that of non-coupon users.

Sensitivity analyses

Repeating our analyses stratified by atorvastatin and rosuvastatin (Appendix Tables 1 and 2) with an open cohort of statin patients, patients with no use of mail-order prescription services and patients with limited opioid use (Appendix Table 3) did not substantively impact the results from our main analyses. Similarly, allowing for unlimited stockpiling, varying the time period defining termination, and using an alternative method for comorbidity adjustment had little impact on our main results.

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study of statin users among commercially insured incident statin users, those who used a coupon on their first fill were dispensed a similar quantity of pills than non-coupon users over 1 year, but were less likely to have switched statins or to have terminated treatment altogether after 12 months of follow-up. There was a dose-response association present, and these effects increased modestly over time. At one 1year, coupon users had out-of-pocket costs that were approximately $1–$5/month lower than non-coupon users but had similar total costs. These results are important because the use of drug coupons is increasing, and how little is known about the effects of these coupons on patients’ utilization, out-of-pocket costs, and total costs.

Our study contributes to a growing evidence-base regarding the effect of drug coupons on drug utilization and expenditures. One prior report used a hypothetical insurance program and publicly available retail prices for statins to suggest that coupons may lead to lower out-of-pocket costs among patients, but significantly higher costs for insurers due to a reduction in the use of generic products.3 A second study using commercial pharmacy claims from incident statin patients suggested that coupon users had more statin fills one year after statin initiation and both higher out-of-pocket and total statin prescription costs compared to generic statin initiators and non-coupon users of branded statins.9 In contrast to these studies, we found that statin coupons were associated with similar levels of utilization and total pharmacy costs. There are important differences between our approach and these prior studies that may account for these differences, including our use of longitudinal GEE models that account for within-subject correlations over time, as well as our analytic approach that increased comparability across the groups of coupon users and non-users.18

Manufacturers’ use of drug coupons remains a controversial area of pharmaceutical policy. In addition to historic concerns that are similar to those regarding direct-to-consumer advertising 6 and the distribution of free medication samples8, there are particular provisions in payment policy that preclude the use of coupons for services covered by nearly all federal health care programs.19 Despite safeguards to prevent unauthorized use, a survey commissioned by the National Coalition on Health Care found that 6% of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D were using coupons19, an issue under recent study by the Office of the Inspector General.20 The practice of providing drug coupons has also been challenged by groups outside of the federal government. For example, in 2012, a group of trade union health plans sued eight large drug manufacturers claiming that drug coupon programs violate federal bribery laws.21 Massachusetts has prohibited drug coupons since 1988, which made it the only state with a complete ban on coupons. However, in 2013, the Massachusetts legislature created an exception to the law that allowed the use of coupons for branded drugs with no generic equivalent.22

The rapid growth of specialty drug utilization in the United States, which totaled an estimated $87 billion in 2012, are projected to reach $400 billion by 202023. This also lends added urgency to the issue of drug coupons. In one analysis examining the use of coupons for biologic anti-inflammatory or multiple sclerosis medications among the commercially insured, coupons offset more than 60% of patients’ out-of-pocket costs. While this substantially reduced patients’ cost-sharing, it also circumvented payer efforts to constrain rising health care costs through the use of pharmacy benefits management.24 The use of coupons in this setting may be increasingly common as payers attempt to manage specialty costs through higher deductibles as well as changes to pharmacy benefit design, such as the use of higher cost-sharing tiers in lieu of the standard three-tier design as well as step-therapy or fail-first programs that steer physicians and patients towards lower cost therapies.

Our analyses had several limitations. First, we were unable to determine the dollar amount of the coupon used and therefore, the savings to the consumer, after accounting for coupons. Second, our analysis was limited to individuals filling prescriptions through retail pharmacies, since our data did not include individual-level claims data for transactions filled through mail-order services. Third, we assumed that the availability of a drug coupon only affects individuals who choose to use such a coupon, even though it is possible that the availability of a coupon affects the broader equilibrium prescription drug prices, formulary assignment, and out-of-pocket costs. Fourth, our analyses were not designed to account for additional market complexities, such as atorvastatin’s patent expiry and potential switching from statin to non-statin lipid lowering therapies that may also have been relevant to the primary associations of interest. Fifth, these data capture only prescriptions paid for and given to an individual patient; therefore we were unable to account for prescriptions that were filled but never picked up. Sixth, we derived our analytic cohort from a larger cohort of opioid recipients, which may have diminished the generalizability of our findings. However, restricting our analyses to patients with no opioid fills after their incident statin fill had no substantive impact on our main results. Finally, our analyses do not allow determination of whether drug coupons result in lower utilization of generic medications.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite their increasing use, relatively little is known regarding the effect of drug coupons on consumer behavior. In the case of statins, we found that drug coupons are associated with greater utilization and lower rates of statin discontinuation and short-term switching. It is unclear whether coupons have a similar effect when applied in other therapeutic contexts, and these associations may be of particular interest and importance in the coming decade as manufacturers continue to design programs that buffer patients from high cost-sharing, which simultaneously reduce patient’s potential cost-burden while preserving demand for higher cost, branded products.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

Support and Acknowledgments

Dr. Alexander is supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL107345). Dr. Riggs is supported by NIH Grant T32HL007180. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, analysis, or interpretation of the data and preparation or final approval of the manuscript prior to publication. The authors gratefully acknowledge Christine Buttorff for comments on an earlier manuscript draft.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Alexander is Chair of the FDA’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee, serves as a paid consultant to IMS Health and serves on an IMS Health scientific advisory board. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from the following IMS Health Incorporated information service(s): IMS Health LifeLink™ (2006–2013). The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IMS Health Incorporated or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

References

- 1.Aiken M. Use and shifting costs of healthcare: A review of the use of medicines in the U.S. in 2013. [Accessed April 3, 2015];IMS Health. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/portal/site/imshealth/menuitem.762a961826aad98f53c753c71ad8c22a/?vgnextoid=2684d47626745410VgnVCM10000076192ca2RCRD.

- 2.Starner CI, Alexander GC, Bowen K, Qiu Y, Wickersham PJ, Gleason PP. Specialty drug coupons lower out-of-pocket costs and may improve adherence at the risk of increasing premiums. Health Aff. 2014;33:1761–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grande D. The Cost of Drug Coupons. JAMA. 2012;307:2375–2376. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visante. Pharmaceut Care Manage Assoc. Nov, 2011. How copay coupons could raise prescription drug costs by $32 billion over the next decade [white paper] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz D. Drug coupons: a good deal for the patient, but not the insurer. Kaiser Health News; Oct, 2012. http://kaiserhealthnews.org/news/drug-coupons/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornfield R, Donohue J, Berndt ER, Alexander GC. Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers and providers, 2001–2010. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhutada NS, Cook CL, Perri M., 3rd Consumers responses to coupons in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. Health Mark Q. 2009;26:333–46. doi: 10.1080/07359680903315902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander GC1, Zhang J, Basu A. Characteristics of patients receiving pharmaceutical samples and association between sample receipt and out-of-pocket prescription costs. Med Care. 2008;46:394–402. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181618ee0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daugherty JB, Maciejewski ML, Farley JF. The impact of manufacturer coupon use in the statin market. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19:765–72. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.9.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross JS, Kesselheim AS. Prescription-drug coupons--no such thing as a free lunch. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1188–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1301993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coupons for Patients, but Higher Bills for Insurers. New York Times; Jan 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.IMS Health. Longitudinal LRX Insights. http://www.imsbrogancapabilities.com/en/market-insights/lrx.html.

- 13.Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, Malone DC. Measurement of Adherence in Pharmacy Administrative Databases: A Proposal for Standard Definitions and Preferred Measures. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2006;40:1280–1288. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark DO, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Baluch WM, Simon GE. A chronic disease score with empirically derived weights. Med Care. 1995;33:783–95. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199508000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. pp. 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Mahendra G. [Accessed July 28, 2015];Using “Recycled Predicitions” for Computing Marginal Effects. Available at: http://www.lexjansen.com/wuss/2009/hor/HOR-Li.pdf.

- 17.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graubard B, Edward L, Korn E. Predictive Margins with Survey Data. Biometrics. 1999;55:652–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Accessed June 10, 2015];Drug companies fend off competition from generics by offering discount coupons. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/drug-companies-fend-off-competition-from-generics-by-offering-discount-coupons/2012/10/01/c7a393be-f05f-11e1-ba17-c7bb037a1d5b_story.html.

- 20.Levinson DR., Inspector General . Manufacturer Safeguards May Not Prevent Copayment Coupon Use for Part D Drugs. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General; Sep, 2014. (OEI-05-12-00540) [Google Scholar]

- 21. [Accessed June 10, 2015];Consumer group sues 8 drugmakers over drug coupons. Available at: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/industries/health/drugs/story/2012-03-07/drug-coupons-lawsuit/53400686/1.

- 22. [Accessed June 10, 2015];The 189th General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleXXII/Chapter175H/Section3.

- 23.CVS Caremark. [Accessed June 10, 2015];Specialty Trend Management: Where to Go Next, Insights. 2013 Available at: http://www.cvshealth.com/sites/default/files/Insights%202013.pdf.

- 24.Starner CI, Alexander GC, Bowen K, Qui Y, Wickersham P, Gleason PP. Specialty Drug Coupons Lower Out-of-pocket Costs and May Improve Adherence at the Risk of Increasing Premiums. Health Affairs. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0497. Published online October 6, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.