Abstract

Objectives

Since the introduction of non-vitamin K antagonist (VKA) oral anticoagulants (NOACs), an additional treatment option, apart from VKAs, has become available for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). For various reasons, it is important to consider patients’ preferences regarding type of medication, particularly in view of the established relationship between preferences towards treatment, associated burden of treatment, and treatment adherence. This review aimed to systematically analyse the scientific literature assessing the preferences of AF patients with regard to long-term oral anticoagulant (OAC) treatment.

Methods

We searched the MEDLINE, Scopus and EMBASE databases (from 1980 to 2015), added records from reference lists of publications found, and conducted a systematic review based on all identified publications. Outcomes of interest included any quantitative information regarding the opinions or preferences of AF patients towards OAC treatment, ideally specified according to different clinical or convenience attributes describing different OAC treatment options.

Results

Overall, 27 publications describing the results of studies conducted in 12 different countries were included in our review. Among these, 16 studies analysed patient preferences towards OACs in general. These studies predominantly assessed which benefits (mainly lower stroke risk) AF patients would require to tolerate harms (mainly higher bleeding risk) associated with an OAC. Most studies showed that patients were willing to accept higher bleeding risks if a certain threshold in stroke risk reduction could be reached. Nevertheless, most of the publications also showed that the preferences of AF patients towards OACs may differ from the perspective of clinical guidelines or the perspective of physicians. The remaining 11 studies included in our review assessed the preferences of AF patients towards specific OAC medication options, namely NOACs versus VKAs. Our review showed that AF patients prefer easy-to-administer treatments, such as treatments that are applied once daily without any food/drug interactions and without the need for bridging and frequent blood controls.

Conclusion

Stroke risk reduction and a moderate increase in the risk of bleeding are the most important attributes for an AF patient when deciding whether they are for or against OAC treatment. If different anticoagulation options have similar clinical characteristics, convenience attributes matter to patients. In this review, AF patients favour attribute levels that describe NOAC treatment.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| For patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), stroke risk reduction and a moderate increase in bleeding risk are the most important attributes of anticoagulation treatment. AF patients are willing to accept higher bleeding risks for significant stroke risk reductions. |

| When the clinical characteristics of anticoagulation treatments are similar, patients with AF prefer easy-to-administer treatments (i.e. once-daily application, no food/drug interactions, no need for bridging, and no need for frequent blood controls). |

Introduction

With a prevalence of 1–3 % in the general population, atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac disorder [1–7], and its prevalence is expected to increase markedly in most countries in the next few years [5–8]. AF patients have been reported to be at high risk for heart failure and thromboembolic events [8, 9]. In particular, the risk of ischaemic strokes is up to fivefold higher than in the general population [6, 8–10]. Current AF guidelines recommend the assessment of thromboembolic event/stroke risk and, if a certain risk exists in a patient, lifelong oral anticoagulant (OAC) treatment [7, 11]. To assess the risk of stroke in patients with AF, the CHADS2 score [12] or the CHA2DS2-VASc score instruments have been recommended [13]. Based on these, patients with a CHADS2/CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥1 are at mild or high risk of stroke and should consequently receive OAC treatment, while patients with a score equal to 1 may receive aspirin [7, 11].

For several decades, vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) have been the only OAC treatment option for AF patients; however, in 2011, the first non-VKA oral anticoagulant (NOAC) became available for these patients as an alternative to VKA treatment. To date, four NOACs have been approved for stroke prevention in non-valvular AF (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban). Most clinical studies have shown that NOAC treatment in AF patients with a need for anticoagulation is at least as effective and safe as VKA treatment [14–16]; however, former studies also indicate that a difference in patient perception may exist with regard to the treatment options mentioned [17–19]. This may be of particular importance because, inherently, every treatment should be centred on the patient. This is especially relevant in the long-term treatment of chronic diseases such as AF because patient preferences may influence not only the long-term adherence of patients but also the physician–patient relationship and, finally, the real-world effectiveness of a particular type of treatment [20].

Consequently, it is important to know which anticoagulation treatment characteristics AF patients prefer. In line with this, clinical guidelines highly recommend taking into account the views and preferences of an AF patient when deciding on OAC therapy options [7, 11, 21, 22]. In this way, the patient is enabled to make an informed decision, in partnership with the healthcare professionals, about their upcoming treatment. In turn, this will enable healthcare professionals to understand the patient’s view, which can be assumed to be of utmost importance, especially in the long term [22].

Little is known about the preferences of AF patients with regard to OAC therapy; therefore, the objective of this analysis was to conduct a systematic literature review summarising the results of studies dealing with the preferences of AF patients towards OAC treatment.

Methods

The methods applied in this review are consistent with those proposed in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [23].

Study Selection

We searched the MEDLINE, Scopus and EMBASE databases (from 1980 to 2015), added records from reference lists of publications found, and conducted a systematic review based on all identified publications. All in all, we conducted a literature search on the basis of 20 queries, which included the terms ‘preferences’, ‘atrial fibrillation’ and ‘discrete choice experiment’, amongst others.1 Inclusion criteria for studies were defined as follows:

The study was published between 1980 and 2015, and written in either German or English.

The study quantitatively assessed the opinions or preferences of AF patients towards OAC therapy; qualitative studies, authors’ opinions regarding patient opinions or preferences, as well as studies dealing with physicians’ opinions only, were excluded.

We excluded all studies that did not describe the questionnaire used or the applied preference elicitation technique in sufficient detail.

Outcomes of interest included any quantitative information about the opinions or preferences of AF patients towards OAC treatment. If studies provided detailed insights, or even a trade-off assessment of different (partly competing) attributes describing OAC treatment options, results of these assessments were included.

Assessment of Study Eligibility and Inclusion

All titles and abstracts identified through the initial search in the digital literature were reviewed independently by two reviewers, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion and/or referral to a third reviewer if necessary. Articles were excluded when they were obviously considered irrelevant, which was decided on the basis of their titles and abstracts. Eligibility of the remaining articles was assessed on the basis of the inclusion criteria listed above. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses that met the inclusion criteria were not included in our review but were used to identify any other potentially relevant articles. A comparison of our results with those of identified systematic reviews or meta-analyses addressing similar topics is presented in the Discussion section of this paper.

The methodological quality and the main characteristics of the included studies were evaluated on the basis of the following types of information:

Addressed disease (AF only or additional diseases).

Single-centre versus multicentre study.

Selection of surveyed patients (random, consecutive or convenience sample).

Sample size (number of patients).

Type of surveyed persons (AF patients, patients with other cardiovascular diseases, general public).

OAC experience of surveyed persons.

Main study objective (assessment of patient preferences towards OACs in general versus preferences towards specific OAC medication types, i.e. mainly VKAs versus NOACs).

Preference elicitation technique used, with a focus on how potential trade-offs between different treatment attributes associated with different anticoagulation options were dealt with. Here we differentiated between studies using simple descriptive methods (e.g. self-developed questionnaires investigating the importance of specific attributes, based on Likert scales), trade-off/threshold/standard gamble techniques or, more recently, developed preference elicitation techniques (e.g. analytical hierarchy method, traditional conjoint analysis or discrete choice analysis). In addition, we assessed whether the included studies primarily dealt with clinical attributes associated with different anticoagulation options (mainly thromboembolic events and bleeding rates), respective convenience attributes (e.g. frequency of intake, interaction with other drugs/food, regular blood controls), or both.

Data Extraction

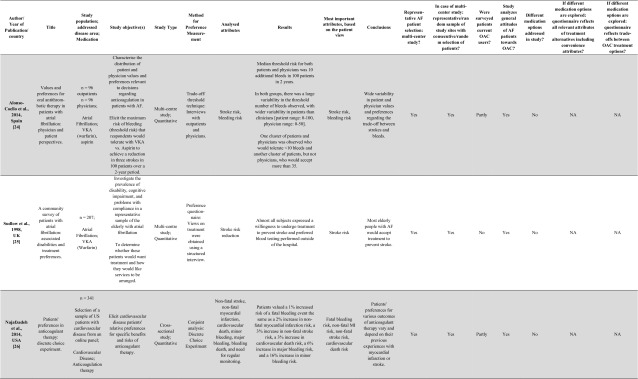

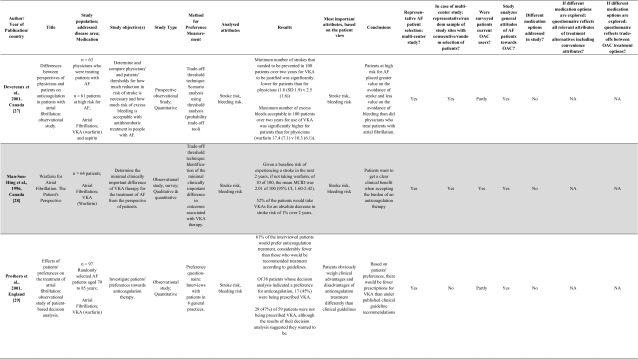

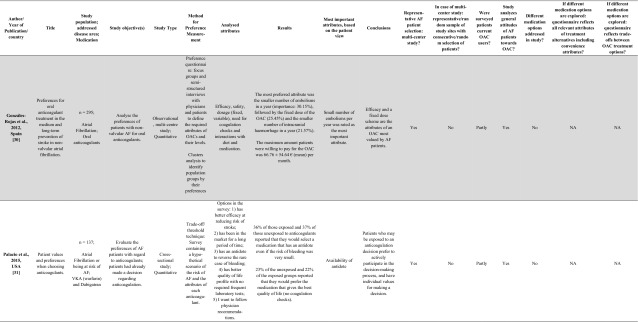

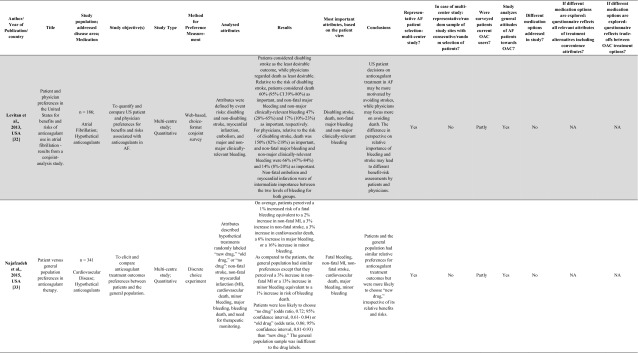

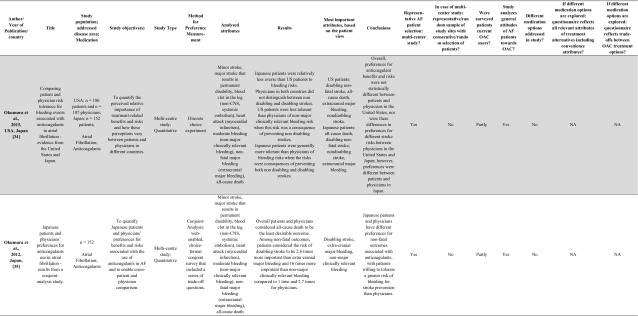

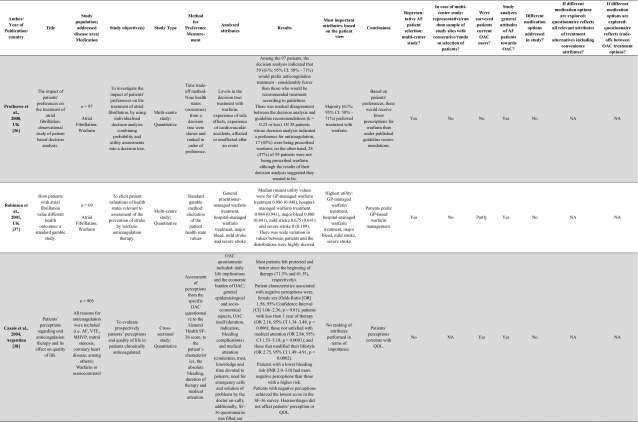

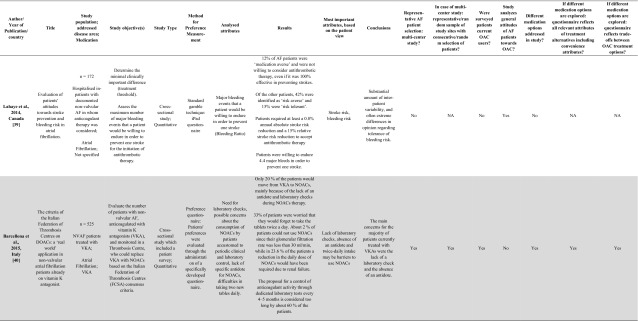

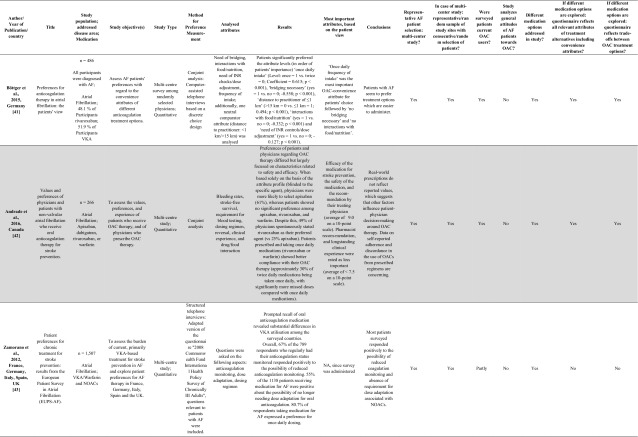

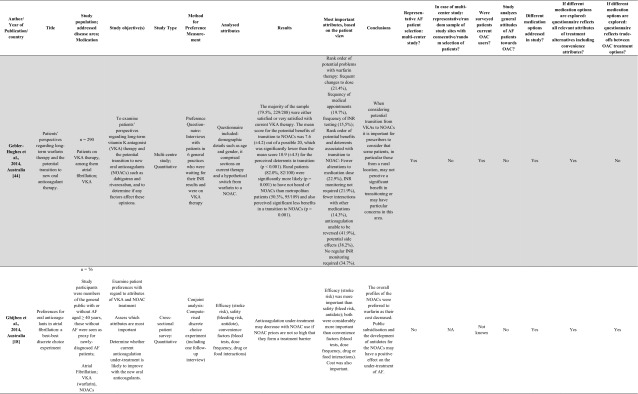

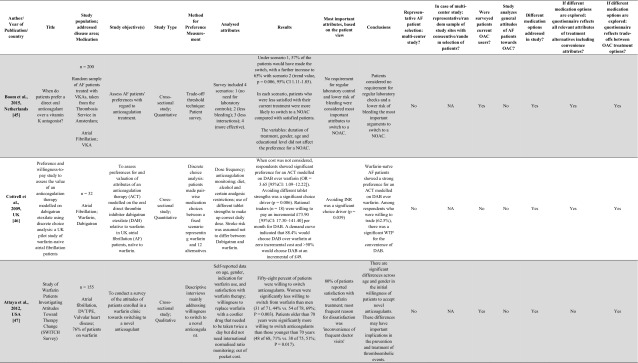

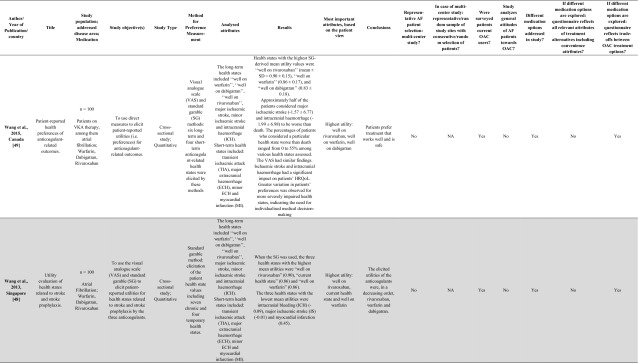

Information regarding study design (including sample definition and methodology), characteristics of study participants (sample size, addressed disease), analysed attributes or attribute levels in the study, and study results (qualitative or quantitative data with regard to patient opinions/preferences) were collected for each included publication and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the studies included in the systematic literature review

AF atrial fibrillation, OAC oral anticoagulant, NA not applicable, VKA vitamin K antagonist, DCE discrete choice experiment, MI myocardial infarction, SD standard deviation, MCID minimal clinically important difference, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio, CNS central nervous system, GP general practitioner, VTE venous thromboembolism, MHVP mechanical heart valve prosthesis, CHD coronary heart disease, SF-36 Short-Form 36, INR international normalised ratio, QOL quality of life, DOACs direct oral anticoagulants, NVAF non-valvular atrial fibrillation, NOACs non-VKA oral anticoagulants, WTP willingness to pay, DVT deep vein thrombosis, PE pulmonary embolism, HRQoL health-related quality of life, EUPS-AF European Patient Survey in AF, NK not known, ACT anticoagulation therapy, DAB dabigatran etexilate, VAS visual analogue scale, SG standard gamble, ICH intracranial haemorrhage, TIA transient ischaemic attack, ECH extracranial haemorrhage

Statistical Analysis and Synthesis

Our main focus was to investigate which anticoagulation treatment would be preferred by AF patients. This was done on a per-study basis; no meta-analysis was conducted due to the expected diversity of studies in terms of analysed samples and methodology used to elicit preferences.

Results

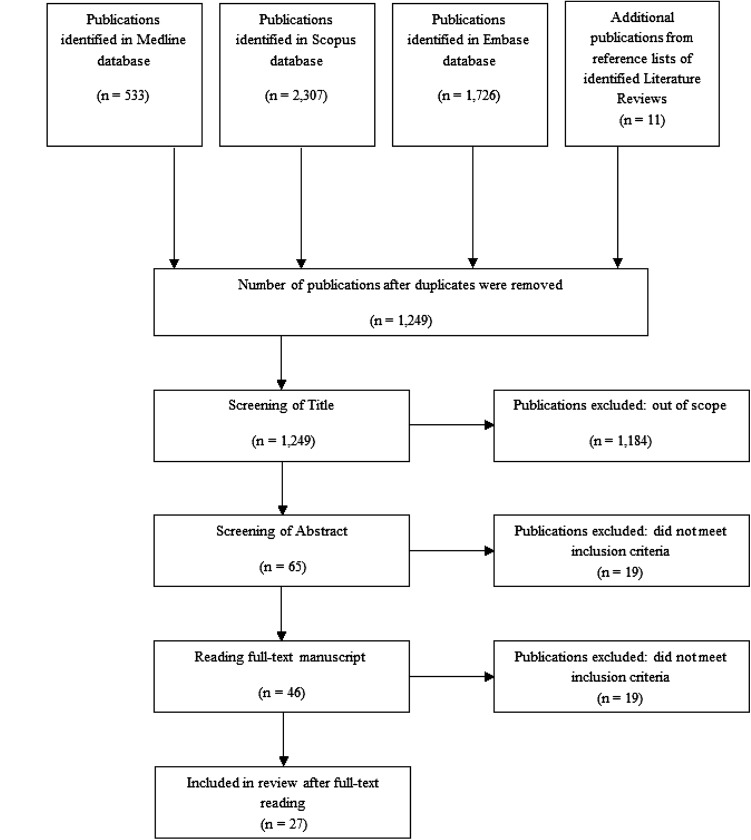

Study Selection and Characteristics

The electronic search identified 4577 records, including duplicates, and 1249 records after duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). Based on the screening of titles, a further 1184 records (94.8 %) were removed, with an additional 19 records being removed after screening of the abstract, and 19 being removed after reading the manuscript, resulting in 27 studies being included in the review. An overview of selected study characteristics, as well as study methodology and study results, are provided in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart illustrating the study selection process

All studies used patient surveys to elicit patient preferences, with six studies including additional physician surveys. The number of patients included varied between 32 and 1507, and the identified studies were conducted in 12 different countries.

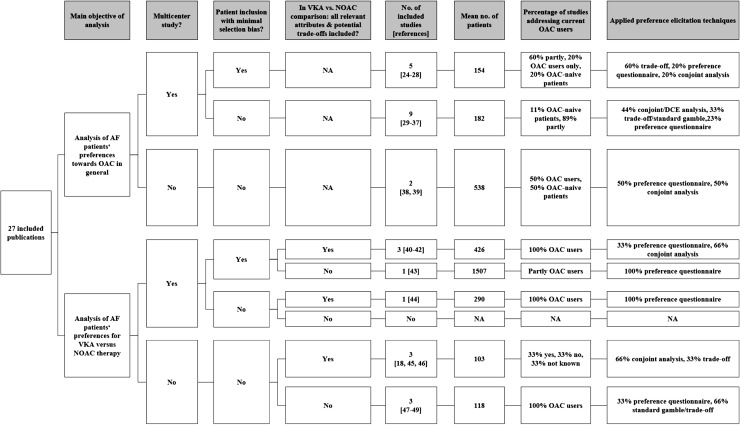

Figure 2 describes the main types of included studies; 16 studies analysed patient preferences towards OAC in general [24–39]. These studies predominantly assessed which benefits (mainly lower stroke risk) AF patients would require to tolerate harms (mainly higher bleeding risk) associated with an OAC. Five of these studies were multicentre studies that applied different techniques to ensure a representative inclusion of patients (mean number of patients 154) [24–28]. In these studies, the majority of surveyed patients were current OAC users. In addition, the majority of these five studies used a trade-off methodology for the survey.

Fig. 2.

Main characteristics of the included studies. VKA vitamin K antagonist, NOAC non-VKA oral anticoagulant, OAC oral anticoagulant, AF atrial fibrillation, NA not applicable, DCE discrete choice experiment

An additional nine studies could also be characterised as multicentre studies but they applied a convenience sample of patients (mean number of patients 182) [29–37]. As previously, the majority of surveyed patients were OAC users, and the preference elicitation technique used most commonly was conjoint analysis. Finally, two of the studies assessing general preferences towards OAC use were single-centre studies (mean number of patients 538) [38, 39]. In these studies, one used a trade-off technique surveying OAC-naïve patients, and the other used a preference questionnaire interviewing current OAC users.

The remaining 11 included studies assessed AF patient preferences towards specific OAC medication options, namely NOACs versus VKAs (Fig. 2) [18, 40–49]. Three of these could be characterised as multicentre studies ensuring a representative inclusion of patients and applying a methodology that addressed most of the known differences between VKAs and NOACs (mean number of patients 426) [40–42]. All of these three studies addressed OAC users only. One study used a descriptive preference questionnaire, while two others used conjoint analysis.

One additional multicentre study including a representative sample of 1507 AF patients (partly OAC users) used a descriptive preference questionnaire [43]; however, this study did not include all known differences between NOACs and VKAs as attributes. Another study in the group of multicentre studies analysing preferences towards NOACs or VKAs was based on a convenience sample of OAC users. This study used a descriptive preference questionnaire (290 patients) [44].

In three additional single-centre studies that included most of the known differences between NOACs and VKAs as attributes of the preference survey (mean number of patients 103), one study used the trade-off technique, and two others used conjoint or discrete choice analysis [18, 45, 46]. One study addressed current OAC users, one study addressed OAC-naïve patients, and one study addressed members of the general public without known OAC status.

Finally, three single-centre studies including a convenience sample of AF patients (100 % OAC users; mean number of patients 118) mostly used a standard gamble/trade-off technique (two studies), while one study used a preference questionnaire [47–49]. None of these studies addressed all known differences between NOAC or VKA treatment.

Preferences of Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Patients Towards Oral Anticoagulation Therapy

In the 16 included studies that dealt with the preferences of AF patients towards OAC therapy in general, the main question addressed was what degree of stroke risk reduction AF patients would require in order to accept an anticoagulation therapy-associated higher bleeding risk.

The five studies with the highest methodology ranking as indicated above showed that AF patients are willing to accept certain bleeding risks for a decrease in the probability of experiencing a stroke. However, there was substantial variability in the threshold number of bleeds observed for the acceptance of OAC, both between the different studies and, more so, between surveyed participants within the studies. A Spanish survey reported a threshold of 10 additional bleeds in 2 years, while a Canadian survey reported 17 additional bleeds in 2 years (both for acceptance of OACs) [24, 27]. In the same survey, the minimum required stroke prevention rate for the acceptance of OAC with its associated higher bleeding risk was 1.8 strokes per 100 patient years. An additional Canadian survey reported 52 % of AF patients would accept warfarin treatment if it was associated with a 1 % stroke risk reduction over 2 years [28]. A recent US survey showed that AF patients valued a 1 % increased risk of a fatal bleeding event the same as a 2 % increase in non-fatal myocardial infarction risk, a 3 % increase in non-fatal stroke risk, a 3 % increase in cardiovascular death risk, a 6 % increase in major bleeding risk, and a 16 % increase in minor bleeding risk [26].

The results of the 11 studies with a lower methodological quality were generally in line with the above results. In another Canadian survey, patients required at least a 0.8 % annual absolute stroke risk reduction and a 15 % relative stroke risk reduction to accept antithrombotic therapy. Patients were willing to endure 4.4 major bleeds in order to prevent one stroke [41]. This study identified different patient segments on the basis of general attitudes towards anticoagulation; 12 % of patients were seen as ‘medication averse’, meaning that they would not be willing to consider anticoagulation therapy even if it were to be 100 % effective. Among the other patients, 42 % were identified as ‘risk averse’, indicating that the patients were not willing to consider antithrombotic therapy if there was any increased risk of bleeding compared with the ‘no therapy option’, and 15 % were ‘risk tolerant’, denoting that these patients did not appear to care about the risk of bleeding at all. The remaining patients could not be assigned to either of these categories [39].

Interestingly, studies comparing the general willingness of patients to accept OAC treatment with clinical guidelines concluded that significantly fewer patients (61 %) would be willing to accept such a therapy than is recommended in clinical guidelines [29]. Furthermore, several studies found that patients and physicians evaluate stroke and bleeding risks differently, with physicians interpreting bleeding risks as more important and stroke risk as less important than patients do [27, 32, 35].

Preferences of AF Patients Towards Specific OAC Attributes

Eleven identified studies analysed patient preferences towards OAC treatment and included, either additionally or separately, attributes that were different from either stroke/thromboembolic event or bleeding risk. Overall, these attributes can be called ‘convenience attributes’ describing NOACs and VKAs as alternative treatment options.

Among the three studies with the highest methodological quality, one German survey analysed the preferences of AF patients towards convenience attributes of anticoagulation options [41]. Based on a discrete choice analysis of AF patients receiving either VKAs or therapy with one specific NOAC agent, a once-daily frequency of intake was the most important attribute describing different treatment options, followed by ‘no bridging necessary’, and ‘no interactions with food/nutrition’. The authors of this particular survey concluded that German AF patients would be willing to accept an additional distance of 29.3 km to see the treating physician in order to receive treatment that would incorporate once-daily intake, no necessary bridging in case of surgeries, less food/drug interaction and an absence of monthly blood tests, if such a treatment was compared with VKA treatment [41]. However, in an Italian study, only 20 % of AF patients stated they would be willing to move from VKA to NOAC therapy. Patients not willing to switch to an NOAC agent mentioned that the lack of an antidote and the absence of regular laboratory checks were the main reasons for their preference towards VKA treatment. The majority of patients indicated that they would prefer regular coagulation laboratory monitoring during treatment with NOACs. The absence of such monitoring would be a source of concern for patients because they would be afraid of suffering a thrombotic or haemorrhagic complication. Thirty-three percent of the study population indicated that they were concerned about forgetting to take the two daily tablets and about the associated risk of non-adherence [40]. The third of these studies, a recent Canadian survey, concluded that real-world OAC prescriptions do not reflect reported patient preferences, which suggests that other factors influence patient–physician decision making around OAC therapy. The authors additionally concluded that data on self-reported adherence to OAC therapy and discordance in the use of OACs from prescribed regimens raise important concerns and warrant further investigation [41].

Here too, and as mentioned earlier, the results of the studies with a lower methodological quality were generally in line with the above results. With regard to their results, no substantial differences were observed between studies surveying different patient types (OAC users versus OAC-naïve patients) or between studies using different preference elicitation techniques. In the majority of studies, AF patients preferred an OAC treatment that, based on convenience attributes, was in line with an NOAC treatment. All in all, of the 11 studies addressing patient preferences towards either NOACs or VKAs, 8 concluded that AF patients prefer NOAC therapy.

However, as illustrated by an Australian survey that analysed AF patient preferences using a discrete choice design including both clinical and convenience attributes associated with either VKA or NOAC treatment, the majority of the above studies also showed that clinical efficacy and safety associated with an OAC alternative are of paramount importance with respect to convenience factors such as regular blood tests, dose frequency, or drug or food interactions [18].

Discussion

Main Results and Comparison with the Literature

Several studies analysed the attitudes of AF patients towards OAC treatment in general, especially the view of AF patients towards the trade-off between a lower stroke and higher bleeding risk. Most of the literature shows that patients are willing to accept higher bleeding risks if a certain threshold in reduced stroke risk can be reached. Nevertheless, the majority of the publications also showed that many AF patients may weigh bleeding risk and stroke risk differently from both physicians and clinical guidelines. Therefore, based on the preferences of AF patients only, fewer patients would receive anticoagulation treatment than may be expected on the basis of recommendations found in clinical guidelines. Consequently, preferences of AF patients may be one important and potentially modifiable explanation for the often observed OAC undertreatment of patients [50, 51]. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to not only identify but also to understand patient preferences with regard to anticoagulation treatment in order to improve adherence to guideline recommendations. Besides that, it is also important that the treating physician educates and informs the patient about stroke and bleeding risks since, in that way, adherence to guideline recommendations can be further improved. All the publications we analysed reported a high variability of AF patient preferences towards anticoagulation treatment; some of the analyses even identified specific AF patient segments, defined by different degrees of bleeding risk aversion.

The above-mentioned results were confirmed by two previous systematic reviews. The authors of the first review concluded that higher patient values and preferences regarding thromboprophylaxis treatment may depend on patients’ prior experience with the treatments, as well as on the methods used for preference elicitation [52]. The second review argued that AF patient preferences may indicate that fewer patients would take VKAs compared with the recommendations of the guidelines. Based on this review, at a stroke rate of 1 % with aspirin, half of the participants would prefer VKAs and, at a rate of 2 % with aspirin, two thirds would prefer VKA treatment [53].

As shown in our review, a second part of the scientific literature analysed the preferences of AF patients towards OAC treatment by including ‘convenience’ attributes, which characterise the alternative OAC treatment options, VKAs and NOACs. Generally, the published data show that AF patients, in accordance with clinical guidelines, weigh clinical attributes such as stroke or bleeding risk more heavily than convenience attributes. Therefore, it is in line with the preferences of AF patients that a treating physician first investigates the clinical effectiveness and safety of the recommended anticoagulant before suggesting alternative treatment choices to the patient. However, this review also showed that if alternative OAC treatments are similar in terms of efficacy and safety, as is the case with many anticoagulation options in AF, convenience attributes such as mode of application, interactions with food or drugs, availability of an antidote, need for bridging, or frequency of application may matter to patients. Furthermore, patients may not only have a preference for a more convenient mode of application but the adherence of patients may also depend on the convenience of medication therapy. Thus, it has been shown that a less frequent dosing schedule, such as once daily on chronic cardiovascular disease medication, is associated with higher treatment adherence [54].

We also identified a variability of results with regard to preferences towards these convenience attributes, which could be explained by several reasons. First, patients analysed in the included studies were different from each other in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, study site characteristics (inpatient versus outpatient treatment, general practitioners [GPs] versus cardiologists) and current anticoagulation treatment, or in terms of the treatment experience of surveyed patients. For example, one German study found that AF patients currently treated with VKAs for at least 3 months (which may be an indicator of stable anticoagulation) did not show any clear preference for or against monthly blood checks, whereas patients treated with an NOAC agent had a clear preference against such checks [41]. Thus, it is important to inform the patient about the differences between NOACs and VKAs, which are apparent in the need for regular blood checks, amongst others. With VKAs, regular checks are necessary, whereas with NOACs, no regular checks are needed.

Second, study methodologies differed markedly between the different studies in terms of the number of included study sites, patient inclusion criteria and patient selection, and the preference elicitation technique used. Because of this, it cannot be ruled out that the selected questions in the descriptive questionnaires used in several studies also influenced reported results. In some studies, interviews were conducted face-to-face, whereas others used phone, written or online interviews, therefore interviewer bias cannot be excluded in these studies [29]. On the other hand, when questionnaires were sent out to participants, there was the risk of non-response bias, potentially leading to skewed results of the study [25].

Three studies analysing preferences towards NOACs versus VKAs used trade-off/standard gamble techniques. These comprise a method that offers the opportunity to compare therapy preference between two different options [45]. The hypothetical efficacy of the intervention is systematically varied until the lowest risk reduction, the point at which patients are willing to take the therapy, is found [28]. A disadvantage of this method is that the consideration of more than two options might generate confusion or fatigue in respondents, resulting in a notable proportion of respondents indicating initial choices that were internally inconsistent [55].

Finally, four studies applied a conjoint analysis/discrete choice experiment (DCE) to analyse preferences towards either NOACs or VKAs. DCE was introduced into health economics as a technique to identify the key characteristics of alternative treatments because patients were concerned with aspects of healthcare other than only clinical outcomes. This method has been used to elicit preferences for health and healthcare in a range of contexts and is now, to a certain degree, seen as a gold-standard technique. The method assumes that the value of medical treatments depends on a number of characteristics. DCE allows one to simultaneously weigh various characteristics of different therapeutic options and to establish the relative importance of each characteristic in the implementation of that therapeutic option. It can also be used to estimate how individuals trade these characteristics; for instance, the rate at which they are willing to give up one characteristic for an increase in another [56]. The main reason for applying a DCE is that simply asking patients to rate treatment-related attributes generally yields no substantial information since patients will state in such a survey that they want all the benefits and none of the indirect/direct costs [57]. One advantage of applying a DCE is that patients are forced to make a trade-off between two or more options and that they have to choose, as is the case in reality, between options that may be associated with utility-increasing and utility-decreasing attribute levels [58].

The studies included in our review that used a DCE technique came to similar conclusions. An Australian study that included both clinical and convenience attributes concluded that the overall profiles of NOACs, compared with VKA treatment, are preferred by patients, especially if an antidote exists and if there are reasonable costs for NOAC treatment [18]. Similarly, in an Italian study that included bleeding risk as an attribute, patients preferred once-daily tablet treatment without regular monitoring [56]. In a German DCE study, AF patients also favoured attribute levels that are best presented by a once-daily NOAC treatment [41].

In addition to the above-mentioned difficulties in comparing the identified studies, due to differences in their methodology, we acknowledge two additional limitations. First, our research was based on a review of publications available in the selected databanks only and, second, due to methodological differences between the studies, we did not conduct a quantitative meta-analysis.

Conclusions

Our review of the preferences of AF patients towards anticoagulation shows that stroke risk reduction and limited bleeding risk are the most important attributes for an AF patient when deciding whether they are for or against a certain treatment. In the stroke risk/bleeding risk trade-off assessment, physicians may be more sensitive to bleeding risk than patients. AF patients are willing to accept higher bleeding risks if a certain threshold in reduced stroke risk can be reached.

Treating physicians should take patient preferences into account when deciding on the type of OAC treatment. If different anticoagulation options have similar clinical characteristics, convenience attributes matter to patients. In this review, AF patients favour attribute levels that describe NOAC treatment (e.g. once-daily intake, no regular blood tests and less drug/food interaction). Whether these convenience advantages may also contribute to improving the percentage of patients in need of lifelong OACs in order to receive such a treatment is open for future research.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest

Thomas Wilke has received honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies, including Novo Nordisk, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Sanofi-Aventis; Thomas Kohlmann has received honoraria from Bayer Vital GmbH, Germany; Rupert Bauersachs has acted as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Bayer Vital GmbH, Germany, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Sabine Bauer and Sabrina Müller have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Bayer Vital GmbH, Germany.

Author Contributions

Thomas Wilke participated in the conception, planning and interpretation of this study, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version. He also acts as overall guarantor for this work.

Sabine Bauer participated in the planning and analysis of the data, critically reviewed the draft manuscript, and approved the final version.

Sabrina Müller participated in the conception and planning of the work, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Thomas Kohlmann participated in the conception of the work, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Rupert Bauersachs participated in the conception of the work, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Footnotes

Search strings entered in MEDLINE were ‘discrete AND choice AND experiment AND atrial AND fibrillation’, ‘discrete AND choice AND experiment AND anticoagulation’, ‘treatment AND preferences AND atrial AND fibrillation’, ‘treatment AND preferences AND atrial AND fibrillation’, ‘discrete AND choice AND experiment AND af’, ‘discrete AND choice AND experiment AND ac’, ‘dce AND atrial fibrillation’, ‘dce AND anticoagulation’, ‘discrete AND choice AND experiment AND cardiac AND arrhythmia’, ‘treatment AND preference AND cardiac AND arrhythmia’, ‘treatment AND preferences AND cardiac AND arrhythmia’, ‘anticoagulant AND discrete AND choice’, ‘anticoagulant AND patient AND preference’, ‘discrete AND choice AND anticoagulation’, ‘discrete AND choice AND anticoagulant’, ‘conjoint AND preference AND anticoagulation’, ‘trade off AND preference AND anticoagulation’, ‘preference AND atrial fibrillation’, ‘preference AND anticoagulation’, ‘preference AND anticoagulant’.

References

- 1.Ryder KM, Benjamin EJ. Epidemiology and significance of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:R131–R138. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00713-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chugh SS, Blackshear JL, Shen WK, Hammill SC, Gersh BJ. Epidemiology and natural history of atrial fibrillation: clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:371–378. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chien K, Su T, Hsu H, Chang W, Chen P, Chen M, et al. Atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence and risk of stroke and all-cause death among Chinese. Int J Cardiol. 2010;139:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, Borowsky L, Pomernacki NK, Singer DE. Comparison of risk stratification schemes to predict thromboembolism in people with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:810–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilke T, Groth A, Mueller S, Pfannkuche M, Verheyen F, Linder R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation: an analysis based on 8.3 million patients. Europace. 2013;15:486–493. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis RC, Hobbs FDR, Kenkre JE, Roalfe AK, Iles R, Lip GYH, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the general population and in high-risk groups: the ECHOES study. Europace. 2012;14:1553–1559. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GYH, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369–2429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirchhof P, Auricchio A, Bax J, Crijns H, Camm J, Diener H, et al. Outcome parameters for trials in atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2803–2817. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, McMurray JJV. A population-based study of the long-term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew/Paisley study. Am J Med. 2002;113:359–364. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friberg L, Hammar N, Rosenqvist M. Stroke in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: report from the Stockholm Cohort of Atrial Fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:967–975. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123:e269–e367. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214876d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864–2870. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fumagalli S, Cardini F, Roberts AT, Boni S, Gabbai D, Calvani S, et al. Psychological effects of treatment with new oral anticoagulants in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: a preliminary report. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:99–102. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghijben P, Lancsar E, Zavarsek S. Preferences for oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a best-best discrete choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:1115–1127. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakhai A, Sandberg A, Mittendorf T, Greiner W, Oberdiek AMS, Berto P, et al. Patient perspective on the management of atrial fibrillation in five European countries. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Pol M, Hennessy D, Manns B. The role of time and risk preferences in adherence to physician advice on health behavior change. Eur J Health Econ. [Epub 16 Apr 2016]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Jones C, Pollit V, Fitzmaurice D, Cowan C. The management of atrial fibrillation: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;348:g3655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). NICE guidelines (CG180), atrial fibrillation (update): the management of atrial fibrillation. 2014. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG180. Accessed 15 June 2016.

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alonso-Coello P, Montori VM, Díaz MG, Devereaux PJ, Mas G, Diez AI, et al. Values and preferences for oral antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: physician and patient perspectives. Health Expect. 2014;18(6):2318–2327. doi: 10.1111/hex.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudlow M, Thomson R, Kenny RA, Rodgers H. A community survey of patients with atrial fibrillation: associated disabilities and treatment preferences. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1775–1778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Najafzadeh M, Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK, Polinski JM, Avorn J, Schneeweiss SS. Patients’ preferences in anticoagulant therapy: discrete choice experiment. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:912–919. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devereaux PJ, Anderson DR, Gardner MJ, Putnam W, Flowerdew GJ, Brownell BF, et al. Differences between perspectives of physicians and patients on anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: observational study. BMJ. 2001;323:1218–1222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7323.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O’Connor A, Wells G, Lemelin J, Wood W, et al. Warfarin for atrial fibrillation. The patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1841–1848. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440150095011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Protheroe J, Fahey T, Montgomery AA, Peters TJ. Effects of patients’ preferences on the treatment of atrial fibrillation: observational study of patient-based decision analysis. West J Med. 2001;174:311–315. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.5.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.González-Rojas N, Gimenez E, Fernandez MA, Heineger AI, Martinez JL, Villar J, et al. Preferences for oral anticoagulant treatment in the medium and long term prevention of stroke in non valvular atrial fibrillation [in Spanish] Rev Neurol. 2012;55:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palacio AM, Kirolos I, Tamariz L. Patient values and preferences when choosing anticoagulants. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:133–138. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S64295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levitan B, Yuan Z, González JM, Hauber AB, Lees M, Piccini JP, et al. Patient and physician preferences in the United States for benefits and risks of anticoagulant use in atrial fibrillation: results from a conjoint-analysis study. Value Health. 2013;16:A11. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Najafzadeh M, Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK, Polinski J, Avorn JL, Schneeweiss S. Patient versus general population preferences in anticoagulant therapy. Value Health. 2015;18:A9–A10. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okumura K, Inoue H, Yasaka M, Gonzalez JM, Hauber AB, Levitan B, et al. Comparing patient and physician risk tolerance for bleeding events associated with anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: evidence from the United States and Japan. Value Health Reg Issues. 2015;6:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okumura K, Inoue H, Yasaka M, Gonzalez JM, Hauber AB, Iwamoto K, et al. Japanese patients and physicians preferences for anticoagulants use in atrial fibrillation: results from a conjoint-analysis study. Value Health. 2012;15(7):A380. doi: 10.36469/9904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Protheroe J, Fahey T, Montgomery AA, Peters TJ. The impact of patients’ preferences on the treatment of atrial fibrillation: observational study of patient based decision analysis. BMJ. 2000;320:1380–1384. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7246.1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson A, Thomson R, Parkin D, Sudlow M, Eccles M. How patients with atrial fibrillation value different health outcomes: a standard gamble study. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2001;6:92–98. doi: 10.1258/1355819011927288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casais P, Meschengieser SS, Sanchez-Luceros A, Lazzari MA. Patients’ perceptions regarding oral anticoagulation therapy and its effect on quality of life. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1085–1090. doi: 10.1185/030079905X50624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lahaye S, Regpala S, Lacombe S, Sharma M, Gibbens S, Ball D, et al. Evaluation of patients’ attitudes towards stroke prevention and bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:465–473. doi: 10.1160/TH13-05-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barcellona D, Luzza M, Battino N, Fenu L, Marongiu F. The criteria of the Italian Federation of Thrombosis Centres on DOACs: a “real world” application in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients already on vitamin K antagonist. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s11739-014-1155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Böttger B, Thate-Waschke I, Bauersachs R, Kohlmann T, Wilke T. Preferences for anticoagulation therapy in atrial fibrillation: the patients’ view. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;40:406–415. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrade JG, Krahn AD, Skanes AC, Purdham D, Ciaccia A, Connors S. Values and preferences of physicians and patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who receive oral anticoagulation therapy for stroke prevention. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:747–753. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zamorano JL, Greiner W, Sandberg A, Oberdiek AMS, Bakhai A. Patient preferences for chronic treatment for stroke prevention: results from the European Patient Survey in Atrial Fibrillation (EUPS-AF) [poster]. Presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress; 25–29 Aug 2012: Munich.

- 44.Gebler-Hughes ES, Kemp L, Bond MJ. Patients’ perspectives regarding long-term warfarin therapy and the potential transition to new oral anticoagulant therapy. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5:220–228. doi: 10.1177/2042098614552073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boom MS, Berghuis EM, Nieuwkerk PT, Pinedo S, Ba Ller HR. When do patients prefer a direct oral anticoagulant over a vitamin K antagonist? Neth J Med. 2015;73:368–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cottrell S, LeReun C, Tilden D, Robinson P. Preference and willingness to pay study to assess the value of an anticoagulation therapy modelled on dabigatran etexilate using discrete choice analysis: a UK pilot study of warfarin-naive atrial fibrillation patients. Value Health. 2009;12:A339. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(10)74667-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Attaya S, Bornstein T, Ronquillo N, Volgman R, Braun LT, Trohman R, et al. Study of warfarin patients investigating attitudes toward therapy change (SWITCH Survey) Am J Ther. 2012;19:432–435. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182373591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Kong MC, Ko Y. Utility evaluation of health states related to stroke and stroke prophylaxis. Value Health. 2013;16:A292. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.1514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Xie F, Kong MC, Lee LH, Ng HJ, Ko Y. Patient-reported health preferences of anticoagulant-related outcomes. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;40:268–273. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilke T, Groth A, Mueller S, Pfannkuche M, Verheyen F, Linder R, et al. Oral anticoagulation use by patients with atrial fibrillation in Germany. Adherence to guidelines, causes of anticoagulation under-use and its clinical outcomes, based on claims-data of 183,448 patients. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:1053–1065. doi: 10.1160/TH11-11-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilke T, Groth A, Pfannkuche M, Harks O, Fuchs A, Maywald U, et al. Real life anticoagulation treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation in Germany: extent and causes of anticoagulant under-use. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;40:97–107. doi: 10.1007/s11239-014-1136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.MacLean S, Mulla S, Akl EA, Jankowski M, Vandvik PO, Ebrahim S, et al. Patient values and preferences in decision making for antithrombotic therapy: a systematic review. Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e1S–e23S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Man-Son-Hing M, Gage BF, Montgomery AA, Howitt A, Thomson R, Devereaux PJ, et al. Preference-based antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: implications for clinical decision making. Med Decis Mak. 2005;25:548–559. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05280558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coleman CI, Roberts MS, Sobieraj DM, Lee S, Alam T, Kaur R. Effect of dosing frequency on chronic cardiovascular disease medication adherence. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:669–680. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.677419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Williams JI, Levy L, Naylor CD. Using a trade-off technique to assess patients’ treatment preferences for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Med Decis Mak. 1996;16:262–282. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moia M, Mantovani LG, Carpenedo M, Scalone L, Monzini MS, Cesana G, et al. Patient preferences and willingness to pay for different options of anticoagulant therapy. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8:237–243. doi: 10.1007/s11739-012-0844-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, Moro D, de Bekker-Grob EW. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:883–902. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reed Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Muhlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed]