Abstract

European medical students should have acquired adequate prescribing competencies before graduation, but it is not known whether this is the case. In this international multicenter study, we evaluated the essential knowledge, skills, and attitudes in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics (CPT) of final‐year medical students across Europe. In a cross‐sectional design, 26 medical schools from 17 European countries were asked to administer a standardized assessment and questionnaire to 50 final‐year students. Although there were differences between schools, our results show an overall lack of essential prescribing competencies among final‐year students in Europe. Students had a poor knowledge of drug interactions and contraindications, and chose inappropriate therapies for common diseases or made prescribing errors. Our results suggest that undergraduate teaching in CPT is inadequate in many European schools, leading to incompetent prescribers and potentially unsafe patient care. A European core curriculum with clear learning outcomes and assessments should be urgently developed.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

☑ Previous studies have shown that recent medical graduates are responsible for the majority of prescribing errors in clinical practice. Additionally, it has been reported that final‐year medical students do not feel prepared for their prescribing task and lack confidence in prescribing.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

☑ This international multicenter study evaluated the essential clinical pharmacology and therapeutics (CPT) competencies of final‐year medical students across Europe.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS TO OUR KNOWLEDGE

☑ Undergraduate teaching in CPT is inadequate in many European medical schools, leading to incompetent prescribers and potentially unsafe patient care. Medical students taught mainly with problem‐based learning CPT curricula have significantly better prescribing competencies than students taught mainly with traditional learning CPT curricula.

HOW THIS MIGHT CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE

☑ A European core curriculum in CPT should be developed with clear learning outcomes, with emphasis on teaching and gaining early experience in drug prescribing for patients in a real‐life clinical setting. There is a need for a robust European assessment structure to ensure these outcomes are met.

In most European countries, medical graduates enter directly into clinical practice immediately after graduation and are required to prescribe drugs on a daily basis. In order to prescribe safely and effectively, graduates should have acquired a minimum set of prescribing competencies (i.e., knowledge, skills, attitudes) by the time they graduate. Although there is no uniform description of what this minimal set should be, the European Association of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (EACPT) stated that European graduates should have sufficient knowledge of commonly prescribed drugs, the ability to adequately treat the most common diseases, a rational approach to drug selection, and the ability to write a prescription safely and unambiguously.1 Unfortunately, findings suggest that European medical graduates do not possess these minimum competencies, because they feel unprepared for their future prescribing task and have little confidence in their prescribing competencies.2, 3, 4 Moreover, prescribing errors are common in hospitals, with one review reporting that errors occurred in about 7% of hospital prescriptions, 2% of patient days, and 50% of hospital admissions.5 A large UK study found a prescription error rate of 8.9% for all medication orders,2 with junior doctors (Foundation Years 1 and 2) being twice as likely as consultants to make a prescribing error. This is even more worrying given that junior doctors write a large proportion of hospital prescriptions.2

Poor undergraduate teaching in pharmacology and clinical pharmacology and therapeutics (CPT) may underlie this lack of prescribing competencies,2 although there are marked differences in the quantity and quality of CPT education within and between European countries.1, 6, 7 This emphasizes the need for a uniform core curriculum in CPT for European medical schools, as suggested by the EACPT in 2007.1 However, much of the available information that could form the basis for curriculum development is out of date, mainly based on expert opinion, and lack supporting quantitative data.8, 9, 10, 11 To gain insight into the level of essential CPT knowledge, skills, and attitudes of final‐year medical students, in order to highlight gaps in knowledge and competence, and to serve as a baseline evaluation for further investigations, we carried out an international multicenter study involving final‐year medical students in several European medical schools. Based on the available literature, we hypothesized that the prescribing competencies of final‐year medical students in Europe are insufficient to prescribe safely and effectively after graduation.

RESULTS

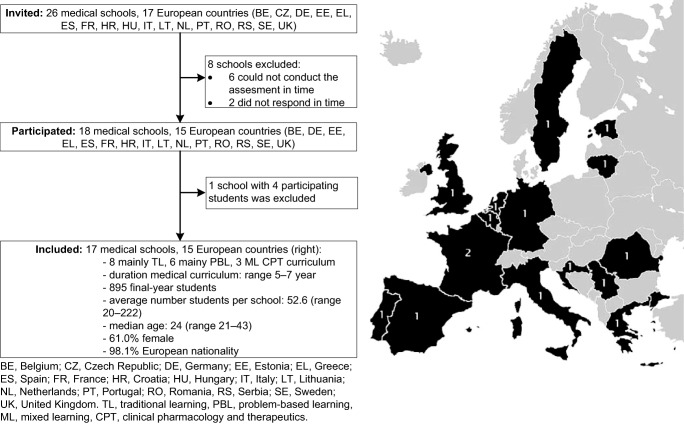

Between 1 March 2015 and 31 March 2016, 17 medical schools (65%; 17/26) from 15 European countries provided data for 895 final‐year students (Figure 1). Three of these medical schools included final‐year and penultimate‐year students, but as there were no relevant differences in demographics and assessment scores (maximum difference 0.6 SD) between these groups in all medical schools, the data for these students were included for analysis.

Figure 1.

Left: Study flow diagram. Right: Map of the number of included medical schools by country.

Knowledge and skills

Students' overall knowledge score was 69.6% (SD 14.9), with the lowest score (50.0%; SD 20.9) being for interactions and contraindications (Table 1). Overall, 46.2% (range 15–76) of the therapies were inappropriate and 54.7% (range 34–65) of the prescriptions contained one or more prescribing errors. The most common errors were “less effective drug choice” (19.6%), “incomplete/incorrect drug prescription” (18.0%), and “overdosing” (17.9%).

Table 1.

Essential knowledge and skills in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics of European final‐year students (n = 895).

| Knowledge (MCQsa) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological mechanisms of actionb | % (SD) | 79.3 (18.1) |

| Side effectsb | % (SD) | 79.4 (17.7) |

| Interactions and contraindicationsb | % (SD) | 50.0 (20.9) |

| Totalb | % (SD) | 69.6 (14.9) |

| Skills (clinical case scenarios) | ||

| Total number of therapies | n | 4.195 |

| Appropriatec | % (range) | 26.2 (5–52) |

| Suboptimalc | % (range) | 27.6 (15–40) |

| Inappropriatec | % (range) | 46.2 (15–76) |

| ‐ Not immediately harmful | % (range) | 81.1 (63–100) |

| ‐ Potentially harmful | % (range) | 15.2 (0–35) |

| ‐ Potentially lethal | % (range) | 3.7 (0–13) |

| Total number of prescriptions | n | 5.429 |

| Total number of prescribing errors | n | 5.104 |

| Number of prescriptions including errors | n (%) | 2.771 (54.7) |

| Type of errorsd | ||

| ‐ Not indicated/inappropriate for indication | % | 9.1 |

| ‐ Less effective drug choice | % | 19.6 |

| ‐ Underdosing | % | 7.8 |

| ‐ Overdosing | % | 17.9 |

| ‐ Too short duration | % | 5.5 |

| ‐ Too long duration | % | 11.3 |

| ‐ Incorrect route | % | 1.4 |

| ‐ Incomplete/incorrect drug prescription | % | 18.0 |

| ‐ Protecting/preventing medication omitted | % | 3.0 |

| ‐ Drug group name | % | 2.3 |

| ‐ Inappropriate abbreviation | % | 0.9 |

| ‐ Therapeutic duplicity | % | 0.7 |

| ‐ Other | % | 2.5 |

MCQs, multiple‐choice questions.

Percent of the total maximum score with equal weighting per medical school.

Percent of the total number of drug therapies with equal weighting per school.

Percent of the total number of prescribing errors with equal weighting per school.

Attitudes

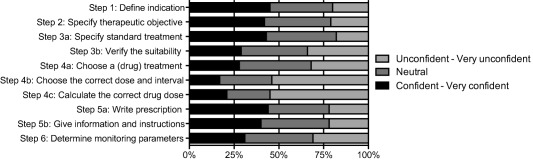

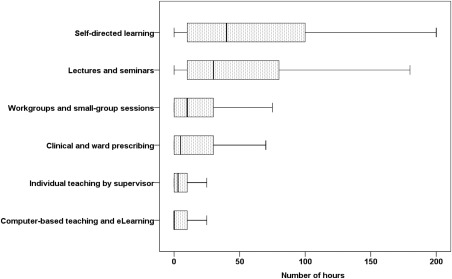

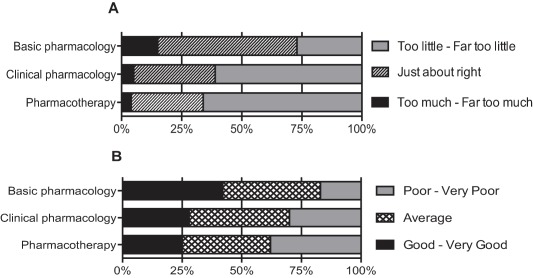

Few students felt confident about their prescribing skills (Figure 2). In total, 70% (range 19–93) of the students reported that they had “written/typed a drug prescription during undergraduate study” 10 or fewer times, of whom 45% (range 0–72) had never written out a prescription. Students estimated they spent most study hours on self‐directed learning (201 hours) and lectures and seminars (78 hours), and the least on computer‐based teaching and eLearning (13 hours) and individual teaching with the supervisor (22 hours) (Figure 3). Most students (>60%) were not satisfied about the undergraduate teaching in clinical pharmacology and pharmacotherapy they had received and thought that too little time was devoted to these subjects (Figure 4 a,b). Most students (61%) felt confident about finding relevant drug information to support prescribing. Forty‐one percent of the students felt that their medical curriculum had not adequately prepared them for their future prescribing responsibilities as junior doctor, 30% were neutral, and only 29% thought they were adequately prepared.

Figure 2.

Self‐reported confidence in prescribing skills according to WHO 6‐step method (n = 895).

Figure 3.

The median number of estimated hours devoted to various methods to teach clinical pharmacology and therapeutics during undergraduate curricula (interquartile range and 10–90 percentiles shown).

Figure 4.

Amount (a) and rating (b) of basic pharmacology, clinical pharmacology, and pharmacotherapy teaching in undergraduate medical curricula.

Associations

Students taught mainly with problem‐based learning or mixed learning CPT curricula had significantly higher overall knowledge scores than students taught mainly with traditional learning curricula (+6.8%; 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.6 to 9.0; P < 0.001, and +3.9 %; 95% CI 1.0 to 7.0; P < 0.05, respectively) and a significantly lower rate of inappropriate therapies (−29.4%; 95% CI –22.7 to –35.5; P < 0.001, and –14.7%; 95% CI –2.9 to –25.1; P < 0.05, respectively). Students who had written more than 10 prescriptions as undergraduates had significantly lower rates of inappropriate drug prescribing than those who had written fewer than 10 prescriptions (–8.9%; 95% CI –0.7 to –16.5; P < 0.05). For each point increase on the Likert scale of prescribing confidence, the rate of inappropriate drug prescribing significantly decreased by 12.9% (95% CI –7.0 to –18.4; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Although there were differences between medical schools, our results show an overall lack of essential prescribing competencies among final‐year medical students in 15 European countries. In particular, the students had a poor knowledge of drug interactions and contraindications, and chose inappropriate therapies for common diseases (46%) or made prescribing errors (55%). Students taught mainly with problem‐based learning or mixed learning CPT curricula had significantly better knowledge (+7 and +4%, respectively) and chose fewer inappropriate therapies (–29% and –15%, respectively) than students taught mainly with traditional CPT curricula. Overall, students lacked confidence about essential prescribing skills, and most were not satisfied about the quantity and quality of undergraduate teaching in clinical pharmacology and pharmacotherapy they had received. Only 29% of the students felt adequately prepared for their future prescribing task as doctors. These findings suggest that undergraduate teaching in CPT in European medical schools may fail to provide newly qualified doctors with sufficient prescribing competencies, which has potential consequences for patient care and treatment effectiveness.

Limitations

The study had a number of limitations. First, the sample represented only a small proportion of the final‐year students in each school and thus findings about prescribing competencies cannot necessarily be extrapolated to the whole cohort. Second, the use of English for the assessment could have introduced bias, because this increased the difficulty of the assessment for nonnative English‐speaking students; however, only nine students (1%) considered the use of English an obstacle (data not shown). Third, the inaccessibility of decision‐support facilities, such as formularies and guidelines, during the assessment does not reflect clinical practice, but we investigated knowledge and skills that European graduates should intrinsically possess without having to resort to guidelines or standards. Fourth, the study was carried out during the final year, and so results may underestimate prescribing competence at the end of the year. However, it is unlikely that students significantly improved their competence in the remaining months, because in most medical schools clinical prescribing training is not trained during this period. Fifth, there may have been selection bias, with participating students being more conscientious than average students or more likely to participate (students were selected by the local study coordinator), or participating medical schools connected to the EACPT Network of Teachers in Pharmacotherapy might devote more hours to CPT education than nonparticipating medical schools. However, in all cases competencies would probably have been overestimated. Sixth, since seven coordinators organized multiple sessions, we cannot rule out that some students told fellow students about the assessments, although they were specifically instructed not to do so. Lastly, because the assessment was performed in a controlled setting, it can be questioned whether the same results would be found in clinical practice. However, it is unlikely that competence would be better in clinical practice, given the time pressure, stress, and distractions on hospital wards.

Interpretation of results

Our findings suggest that European final‐year medical students do not have the required level of prescribing competencies, as defined by the EACPT.1 Although a gold standard for sufficient knowledge is not available, we believe, in line with the UK Prescribing Safety Assessment,12 that medical graduates should have high test scores (≥80–90%) to be able to prescribe safely and effectively after graduation. In particular, students had a poor knowledge of drug interactions and contraindications (50%), as also reported for junior and senior doctors.13 This poor knowledge could be because the quantity and quality of undergraduate clinical pharmacology teaching is inadequate, as implied by the students. Despite the growing digital support (e.g., apps, websites), clinical pharmacology remains a target for educational improvement, because an adequate knowledge of drug interactions and contraindications, especially of commonly prescribed drugs, remains crucial to prescribe safely and to minimize the risk of harm to patients.14

Nearly half of the therapies (46%) were inappropriate, with a substantial proportion of these being potentially harmful (15%) or potentially lethal (4%). This is worrying because the clinical cases were based on common diseases that European graduates will encounter regularly in daily practice. Although this is the first European multicenter study, similar deficits in prescribing skills have been observed in smaller local studies in the past.15, 16, 17 Together with our results, this implies that the level of prescribing skills of European graduates remains insufficient and has not substantially improved over the last few years. The students' opinions about their education suggest that the lack of prescribing skills is because of inadequate undergraduate pharmacotherapy teaching.

The number of erroneous prescriptions (55%) was higher than that reported in a UK study (44%).17 This high rate is perhaps not surprising, since 70% of the European students had written fewer than 10 drug prescriptions during their medical training. Gaining experience in writing drug prescriptions may be an important area for curriculum improvement, because “experienced” students made significantly fewer inappropriate drug prescriptions. Subanalysis showed that one of the main factors influencing prescribing experience is curriculum type: 54% of the students taught mainly with problem‐based learning curricula had written fewer than 10 prescriptions compared with 78% of the students taught mainly with traditional‐based learning curricula. Problem‐based learning curricula may put more emphasis on writing prescriptions during clinical clerkships.

Although in practice most prescribing errors are intercepted by pharmacists and nurses before they cause harm,2 the high error rate may have implications for patient safety. The most common type of error was “less effective drug choice,” i.e., the prescription of an inferior drug for an indication. This might be because medical curricula do not emphasize the use of European and national guidelines for the treatment of common diseases. Dosage errors and incomplete drug prescriptions were also common, which is in line with previous studies among junior doctors.2, 5

One could argue that the prescribing knowledge and skills assessed in this study are appropriate for a generalist (e.g., general practitioner) rather than a specialist (e.g., urologist) medical professional. The latter would undergo additional subspecialty training to acquire the relevant knowledge and skills that are domain‐specific. However, we believe, in line with the EACPT criteria,1 that medical graduates should have broad‐based knowledge and skills in CPT in order to prescribe safely and effectively once qualified, regardless of their future specialty. Moreover, one could ask whether it is essential to have knowledge and skills because electronic prescribing systems alert healthcare professionals to potentially harmful drug combinations and contraindications. However, not all of prescribing systems perform well or consistently and many provide a high volume of irrelevant drug safety alerts, which could lead to “alert fatigue.”18 Moreover, in clinical practice doctors do not always refer to relevant prescribing guidelines, because they are missing, out of date, or too voluminous. Prescribing in these or acute situations is a reason why doctors should have ready knowledge and a broad skills set.

As reported earlier, we found that final‐year medical students did not feel confident about essential prescribing skills.4, 19, 20 In particular, they lacked confidence in how to calculate doses and how to choose the right dose and interval of administration, probably because many students had had little practice in prescribing. In contrast to our previous study, in which we found confidence to be poorly correlated with assessed prescribing skills,19 we found prescribing confidence to be significantly associated with less inappropriate drug prescribing (–13% per point increase). This difference might be because of the different methods used to assess prescribing skills (i.e., oral vs. written assessment). However, this finding, together with the fact that a lack of self‐confidence is undesirable for students' professional development,20 indicates that graduates need to feel confident in their prescribing competence in order to cope with the demanding task of prescribing.

Although students' familiarity with a “problem‐based” assessment method could have influenced results, to our knowledge this is the largest study to show that students taught mainly with problem‐based learning curricula have considerably better prescribing knowledge and skills than students taught mainly with traditional CPT curricula. Since nearly half of the participating medical schools (n = 8; 47%) have traditional CPT curricula, curricular changes might be appropriate, especially since students spent most study hours on passive activities (e.g., learning and listening) and very few on active activities (e.g., clinical prescribing). These findings are similar to the results of a study among 30 medical schools in the UK.6 Although curricular change is a slow and demanding process, it is essential in order to increase the prescribing competencies of future European doctors.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This is the first international multicenter study to report an overall lack of essential prescribing competencies among European final‐year medical students. These results are disturbing. To redress the situation, we suggest the following: 1) a European CPT curriculum should be developed with clear learning outcomes, emphasis on gaining early experience of drug prescribing for real patients in a clinical setting and completing prescriptions; 2) a robust European assessment structure (“European Prescribing License”) should be set up to ensure these outcomes are met; 3) best practices and teaching materials in CPT should be shared among European medical schools; and 4) CPT education should be continued during postgraduate training.

METHODS

Study design and participants

In this descriptive, cross‐sectional study, 26 medical schools in 17 European countries administered a standardized assessment and questionnaire to a sample of their final‐year medical students (Figure 1). Medical schools connected to the EACPT Network of Teachers in Pharmacotherapy (NOTIP) were invited to participate. NOTIP is a European platform for medical schools and CPT teachers who develop and share teaching materials and participate in joint research projects. A minimum sample size of 36 students per school was required, assuming that 90% of students would have an assessment score of 90% or higher, and a standard error of 0.05. The final‐year students were expected to graduate within 1 year. Students were included only if they had followed the undergraduate CPT program at their medical school. The Dutch Ethics Review Board of Medical Education approved the study (Approved Project no. NVMO‐ERB 457). Further approval in other countries was not necessary. All participants gave their informed consent.

Assessment tool and questionnaire: design

Based on the minimal set of prescribing competencies defined by EACPT,1 a Web‐based assessment tool and questionnaire (in English) were developed by the participating centers. The tool consisted of 24 multiple‐choice questions (MCQs, knowledge) and five clinical case scenarios (skills). The MCQs covered basic pharmacological mechanisms of action (n = 8), drug side effects (n = 8), drug–drug interactions, and drug–disease contraindications (n = 8) of essential drug(s), as listed in the World Health Organization (WHO) list of essential medicines.21 The questions about the clinical case scenarios assessed essential CPT knowledge, that is, ready knowledge in CPT that every medical graduate should have acquired before graduation (example: Supplemental Figure 1).14

The scenarios described diseases selected from the list of 40 core diseases that European medical graduates should know how to treat, namely, acute bronchitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, community‐acquired pneumonia, osteoarthritis, essential hypertension (example: Supplemental Figure 2).8 Scenarios were presented in the same format,22 but differed in complexity (disease severity and complicating factors, such as age, comorbidity, and comedication). For each case, the student could choose to prescribe a new drug (maximum of two per case), not to prescribe a drug, and/or stop comedication. Prescribing a new drug meant that the student had to complete an electronic prescription form, including drug name, dose, dosage, duration of treatment, and route of administration.

A standardized questionnaire (attitudes), based on the literature and our previous work (Supplemental Figure 3),3, 4, 6, 19, 20 asked about demographics, self‐reported confidence in prescribing skills (WHO 6‐step23), estimated number of drugs prescribed, estimated number of study hours, evaluation of CPT education received, and perceived preparedness for prescribing. The heads of undergraduate CPT education (local coordinators) indicated the type of CPT curriculum at their medical school (Table 2).

Table 2.

Types of curriculum for clinical pharmacology and therapeutics

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Mainly traditional learning curriculum | >50% of education consists of one or more of the following: lectures (formal), self‐directed learning (textbooks), oral and written exams, essays |

| Mainly problem‐based learning curriculum | >50% of education consists of one or more of the following: seminars (interactive), small working groups (case scenarios), role playing and patient simulation including OSCEs, clinics including prescribing for real patients |

| Mixed learning curriculum | Equal mixture (50/50%) of traditional learning and problem‐based learning |

OSCE, Objective Structured Clinical Examination.

Assessment tool and questionnaire: validity and reliability

The face and content validity of the assessment and questionnaire were established during two online modification rounds with an expert panel of 10 local coordinators. MCQs were based on example questions and final attainment levels of the Dutch National Pharmacotherapy Assessment, which assesses the essential prescribing knowledge of final‐year medical students.24 Minor modifications to the content were made on the basis of a pilot test with 20 medical students from one medical school (Netherlands). The construct validity of the MCQs was based on the scores of clinical pharmacologists/internists not otherwise involved in the study (one from each participating country). With an average score of 91.4% (standard deviation (SD) 6.6), the MCQs evaluated knowledge known by European experts. The internal consistency of the MCQs was good (Guttman Lambda 2 of 0.70).25 The P‐values (percent of correctly answered questions) for individual questions ranged from 0.25 to 0.95, indicating a good spread of difficulty. The item‐rest correlations (rir) for all questions were positive, so no questions were excluded from analyses.

Data collection

The local coordinator selected a random sample of final‐year medical students who would graduate within a year. Recruitment was done during regular teaching sessions, by email, and/or with announcements on electronic notice boards. Selected students were asked to complete the assessment and questionnaire within 60 minutes in a computer room at a scheduled time under the supervision of a local teacher. Seven coordinators organized more than one session to recruit students; information exchange between peers was explicitly prohibited. At the start of the assessment, students were informed about the study objective and received instructions. They were not allowed to use references (except an English dictionary) or to consult each other, or the supervisor. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and without consequences to prevent test‐driven learning prior to the assessment.

Scoring

All MCQs were scored as right or wrong (1–0). Scores are expressed as a percentage of the maximum score. The scoring scheme for the clinical cases was developed by participating coordinators and was based on corresponding European guidelines26, 27, 28, 29 adjusted for local practice (Table 3).2 For each case, the choice of therapy (i.e., newly prescribed drug or no drug, and/or stopped comedication) was classified as appropriate, suboptimal, or inappropriate by the main researcher (D.B.). In case of doubt, a second person was consulted (T.S.). If there was disagreement, the topic was discussed until consensus was reached. To assess interrater reliability, a third assessor (J.T.) scored a purposive sample of 100 drug choices. The proportion of absolute agreement and kappa coefficient between D.B. and J.T. were 89% and 0.85, respectively, indicating substantial agreement.30 Lastly, students' prescriptions were screened by D.B. for prescribing errors, as defined by Dean et al.,31 and categorized by type (Table 1).2

Table 3.

Marking scheme adapted from the EQUIP classification scheme including examples of drug therapies prescribed by students

| Category | Subcategory | Description | Examples (related clinical case) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate | • A drug therapy is defined as appropriate if the correct drug, dose, dosage, duration, and route is chosen according to the European and/or local guidelines | • amoxicillin 500mg three times a day for 5 days per os (CAPa) | |

| Suboptimal | • The dose of drug therapy is slightly too high (half to two times the normal dose) for the condition being treated | • esomeprazole 40mg once daily (GERDb) | |

| • The dose of drug therapy is slightly too low for the condition being treated to produce the desired outcome | • paracetamol 1000mg twice daily (osteoarthritisc) | ||

| • The duration of drug therapy is slightly too long for the condition being treated | • amoxicillin 14 days therapy (CAP) | ||

| • The duration of drug therapy is slightly too short for the condition being treated to produce the desired outcome | • omeprazole 3 weeks (GERD) | ||

| • Second or third choice of drug is prescribed instead of first‐choice drug for the condition being treated (according to the local or (inter)national guidelines) | • ranitidine instead of omeprazole (GERD) | ||

| • Symptomatic drug therapy is prescribed without strong scientific benefits for the patient | • acetylcysteine (bronchitisd) | ||

| Inappropriate | Not immediately harmful | • The drug dose is too high (three times to four times the normal dose) for the condition being treated | • enalapril 20 mg once daily (hypertensione) |

| • The drug dose is too low for the condition being treated to expect a beneficial outcome | • amoxicillin 375mg once daily (CAP) | ||

| • The duration of the drug therapy is too long for the condition being treated resulting in drug overuse | • omeprazole life‐long (GERD) | ||

| • The duration of the drug therapy is too short for the condition being treated to produce the desired outcome | • valsartan 1 week (hypertension) | ||

| • Incorrect drug formulation for route of drug administration | • ceftriaxone per os (CAP) | ||

| • No drug therapy is prescribed although the condition requires initiation of drug therapy | • no additional analgesic prescribed (osteoarthritis) | ||

| • Omission of protective or preventive drug therapy | • NSAID without PPI (osteoarthritis) | ||

| • Unnecessary drug therapy is prescribed for which there is no valid medical indication | • amoxicillin (bronchitis) | ||

| • Duplicate drug therapy is prescribed without benefits for the patient | • two times salbutamol (bronchitis) | ||

| • The prescription lacked drug name, dose, dosage, duration, route, or included inappropriate abbreviations, or drug class instead of generic name, or was illegible | • ‘PPI’ (GERD) | ||

| Potentially harmful | • The drug dose is too high (four to ten times the normal dose) for the condition being treated with increased risk of adverse effects | • tramadol 500 mg once daily (osteoarthritis) | |

| • Unnecessary drug therapy is prescribed for which there is no valid medical indication and with increased risk of adverse effects | • amitriptyline (osteoarthritis) | ||

| • Intravenous drug therapy is prescribed while not medically necessary | • ceftriaxone intravenous (CAP) | ||

| • Duplicate drug therapy is prescribed with increased risk of adverse effects | • two times ibuprofen (osteoarthritis) | ||

| • Drug therapy could exacerbate the patient's condition including drug‐drug interaction or drug‐disease contraindication | • propranolol and asthma (hypertension) | ||

| Potentially lethal | • Serum drug levels are likely to be toxic based on common dosage guidelines | • naproxen 50 g (osteoarthritis) | |

| • Errors including decimal points or units resulting in severe toxicity | • salbutamol 200 mg (bronchitis) | ||

| • Drug therapy being administered has a high potential to cause cardiopulmonary arrest in the dose ordered | • amlodipine 300 mg (hypertension) |

CAP, mild community‐acquired pneumonia (pneumonia severity index I).

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease (grade A) not sufficiently responding to lifestyle changes.

Osteoarthritis not sufficiently responding to treatment with paracetamol.

Uncomplicated acute bronchitis.

Essential hypertension not sufficiently responding to hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily and lifestyle changes.

Statistical analysis

Weighting was used to ensure that each medical school had the same influence in the descriptive analyses. Linear regression analysis was used to compare overall knowledge scores by curriculum type. A Poisson regression model was used to analyze whether curriculum type, number of drugs prescribed, and overall self‐reported confidence in prescribing skills were associated with different rates of inappropriate therapy (i.e., not immediately harmful, potentially harmful, and potentially lethal). Data were collected and analyzed using SPSS v. 22.0 (Chicago, IL).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.B., J.T., T.S., S.B., Y.B., B.C., T.C., R.L., R.M., T.M., E.M., P.P., Y‐M.P., C.P., A.R., R.R., E.J.S., B.T., K.W., T.V., M.R., and M.A. wrote the article; D.B., J.T., T.V., M.R., and M.A. designed the research; D.B., J.T., S.B., Y.B., B.C., T.C., R.L., R.M., T.M., E.M., P.P., Y‐M.P., C.P., A.R., R.R., E.J.S., B.T., K.W., T.V., M.R., and M.A. performed the research; D.B. and T.S. analyzed the data; D.B., T.V., M.R., and M.A. contributed new reagents/analytical tools.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the medical students who participated in this study. We are additionally grateful to the clinical pharmacologists/internists who completed the online assessment: Elena Albu from Gr. T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy; Ivana Cegec from University Hospital Centre Zagreb; Antoine Coquerel from the University of Caen Normandy; Gintautas Gumbrevièius from the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences; Apostolos Hatzitolios from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki; António Lourenço from NOVA Medical School; Floris van Molkot from Maastricht University; Fabrizio De Ponti from the University of Bologna; Dagmar Rüütel from the Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs; Patricio Soares da Silva from the University of Porto; Petra Thürmann from Witten/Herdecke University; Sasa Vukmirovic from the University of Novi Sad; Vincent Yip from the University of Liverpool. Also, we thank Ana Sabo from the University of Novi Sad, and Robert Rissmann and Marleen Hessel from Leiden University Medical Center for their contribution to this study in the data collection process. Lastly, we would like to thank the Working Group National Pharmacotherapy Assessment of the Dutch Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmacy for providing the example questions and final attainment levels of the national assessment.

References

- 1. Maxwell, S.R. , Cascorbi, I. , Orme, M. & Webb, D.J. Joint BPS/EACPT Working Group on Safe Presribing. Educating European (junior) doctors for safe prescribing. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 101, 395–400 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. An indepth investigation into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees in relation to their medical education: EQUIP study. <http://www.gmc‐uk.org/FINAL_Report_prevalence_and_causes_of_prescribing_errors.pdf_28935150.pdf> (2009). Accessed 24 May 2016.

- 3. Tobaiqy, M. , McLay, J. & Ross, S. Foundation year 1 doctors and clinical pharmacology and therapeutics teaching. A retrospective view in light of experience. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64, 363–372 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heaton, A. , Webb D.J. & Maxwell, S.R. Undergraduate preparation for prescribing: the views of 2413 UK medical students and recent graduates. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 66, 28–34 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lewis, P.J. , Dornan, T. , Taylor, D. , Tully, M.P. , Wass, V. & Ashcroft, D.M. Prevalence, incidence and nature of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug. Saf. 32, 379–389 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Shaughnessy, L. , Haq, I. , Maxwell, S.R. & Llewelyn, M. Teaching of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics in UK medical schools: current status in 2009. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 143–148 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keijsers, C.J. et al Education on prescribing for older patients in the Netherlands: a curriculum mapping. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 71, 603–609 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Orme, M. , Frolich, J. & Vrhovac, B. Towards a core curriculum in clinical pharmacology for undergraduate medical students in Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 58, 635–640 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nierenberg, D.W. A core curriculum for medical students in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 31, 307–311 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walley, T. & Webb, D.J. Developing a core curriculum in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics: a Delphi study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 44, 167–170 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ross, S. & Maxwell, S.R. Prescribing and the core curriculum for tomorrow's doctors: BPS curriculum in clinical pharmacology and prescribing for medical students. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 74, 644–661 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maxwell, S.R. , Cameron, I.T. & Webb, D.J. Prescribing safety: ensuring that new graduates are prepared. Lancet. 385, 579–581 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keijsers, C.J. , Leendertse, A.J. , Faber, A. , Brouwers, J.R. , de Wildt, D.J. & Jansen, P.A. Pharmacists' and general practitioners' pharmacology knowledge and pharmacotherapy skills. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 55, 936–943 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brinkman, D.J. et al What should junior doctors know about the drugs they frequently prescribe? A Delphi study among physicians in The Netherlands. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 118, 456–461 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harding, S. , Britten, N. & Bristow, D. The performance of junior doctors in applying clinical pharmacology knowledge and prescribing skills to standardized clinical cases. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 69, 598–606 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. How prepared are medical graduates to begin practice? A comparison of three diverse UK medical schools. Final report for the GMC Education Committee. <http://dro.dur.ac.uk/10561/1/10561.pdf> (2008). Accessed 24 May 2016.

- 17. Sandilands, E.A. et al Impact of a focussed teaching programme on practical prescribing skills among final year medical students. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 71, 29–33 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Metzger, J. , Welebob, E. , Bates, D.W. , Lipsitz, S. & Classen, D.C. Mixed results in the safety performance of computerized physician order entry. Health Aff. (Millwood). 29, 655–663 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brinkman, D.J. , Tichelaar, J. , van Agtmael, M.A. , de Vries , T.P. & Richir, M.C. Self‐reported confidence in prescribing skills correlates poorly with assessed competence in fourth‐year medical students. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 55, 825–830 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brinkman, D.J. , Tichelaar, J. , van Agtmael, M.A. , Schotsman, R. , de Vries , T.P. & Richir, M.C. The prescribing performance and confidence of final‐year medical students. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 96, 531–533 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines 18th list. <http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/18th_EML_Final_web_8Jul13.pdf> (2013). Accessed 24 May 2016.

- 22. Vollebregt, J.A. , Metz, J.C. , de Haan, M. , Richir, M.C. , Hugtenburg, J.G. & de Vries , T.P. Curriculum development in pharmacotherapy: testing the ability of preclinical medical students to learn therapeutic problem solving in a randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 61, 345–351 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de Vries, T.P. , Henning, R.H. , Hogerzeil, H.V. & Fresle, D.A. Guide to Good Prescribing. 1st ed (World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kramers, K. , Tichelaar, J. , Abdi, A. & de Vries, T. Het ‘rijexamen’ voor de voorschrijver. Med. Contact. 70, 912–913 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sijtsma, K. On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach's alpha. Psychometrika. 74, 107–120 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. European Medicines Agency . Guideline on the evaluation of drugs for the treatment of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease. <http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2011/03/WC500103307.pdf> (2011). Accessed 24 May 2016.

- 27. Woodhead, M. et al Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, E1–59 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mancia, G. et al ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 34, 2159–2219 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organisation . Cancer pain relief: with a guide to opioid availability. <http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/37896/1/9241544821.pdf> (1996). Accessed 24 May 2016.

- 30. Viera, A.J. & Garrett, J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 37, 360–363 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dean, B. , Barber, N. & Schachter, M. What is a prescribing error? Qual. Health Care. 9, 232–237 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information