Abstract

Long-branch attraction (LBA) is a major obstacle in phylogenetic reconstruction. The phylogenetic relationships among Juniperus (J), Cupressus (C) and the Hesperocyparis-Callitropsis-Xanthocyparis (HCX) subclades of Cupressoideae are controversial. Our initial analyses of plastid protein-coding gene matrix revealed both J and C with much longer stem branches than those of HCX, so their sister relationships may be attributed to LBA. We used multiple measures including data filtering and modifying, evolutionary model selection and coalescent phylogenetic reconstruction to alleviate the LBA artifact. Data filtering by strictly removing unreliable aligned regions and removing substitution saturation genes and rapidly evolving sites could significantly reduce branch lengths of subclades J and C and recovered a relationship of J (C, HCX). In addition, using coalescent phylogenetic reconstruction could elucidate the LBA artifact and recovered J (C, HCX). However, some valid methods for other taxa were inefficient in alleviating the LBA artifact in J-C-HCX. Different strategies should be carefully considered and justified to reduce LBA in phylogenetic reconstruction of different groups. Three subclades of J-C-HCX were estimated to have experienced ancient rapid divergence within a short period, which could be another major obstacle in resolving relationships. Furthermore, our plastid phylogenomic analyses fully resolved the intergeneric relationships of Cupressoideae.

Rapid radiation of a clade, especially with longer external branches relative to internal branches, is a major obstacle in phylogenetic reconstruction1,2,3. Homoplastic mutations occurring along the long external branches can obscure the true phylogenetic signal on the internal branches, then long-branch attraction (LBA) occurs, with the long branches erroneously clustered together4,5. The LBA artifact was suggested to adversely affect the accuracy of tree reconstruction in many phylogenetic studies6,7,8,9,10,11. It could be amplified in phylogenomics, thereby resulting in a strongly supported but incorrect phylogeny6,12.

Major factors contributing to LBA include faster substitution rate in nonadjacent phylogenetic lineages4, poor taxon sampling due to extinction or unavailability of some taxa13, and unsuitable models of sequence evolution accounting for base compositional heterogeneity14,15 and lineage-specific changes16. Multiple strategies proposed to alleviate the LBA artifact include increasing the representation of taxon sampling5,10,17,18,19; removing the long branch5,9,20, although this method cannot be applied to a trichotomy; excluding third codon positions21; using amino acids instead of nucleotides22,23,24; removing unreliable aligned regions25; removing rapidly evolving genes or sites7,10,26,27,28; applying the site-heterogeneous CAT model;24,29,30,31 and applying coalescent-based tree-building methods32,33.

The cypress family, Cupressaceae, contains about 140 species in 32 genera (17 monotypic) with worldwide distribution34,35,36,37. Recent molecular phylogenetic studies have divided this family into seven subfamilies35,36,38. Five subfamilies (i.e., Cunninghamioideae, Cupressoideae, Sequoioideae, Taiwanioideae and Taxodioideae) are distributed solely in the Northern Hemisphere, and Athrotaxidoideae and Callitroideae are indigenous to the Southern Hemisphere. Cupressoideae, the largest subfamily of Cupressaceae, contains about 100 species in 13 genera34,35,36,37. Species of Cupressoideae are important in the North Hemisphere forest, and many are constructive and dominant species. Many species are also economically important as timber sources, especially species of Calocedrus, Chamaecyparis, Cupressus and Thuja.

Because the Cupressoideae are an ecologically and economically important group, many phylogenetic studies have been performed to resolve intergeneric relationships35,36,38,39,40,41. With the application of several genetic markers and sufficient taxon sampling, two recent phylogenetic studies of Cupressaceae35,36 strongly supported Cupressoideae as monophyletic. Although these two studies resolved most of the intergeneric relationships, discrepancies among different gene trees were detected depending on the phylogenetic positions of the Thuja-Thujopsis and Chamaecyparis-Fokienia clades as well as relationships in the Juniperus (J)-Cupressus (C)-Hesperocyparis-Callitropsis-Xanthocyparis (HCX) clade (the J-C-HCX clade thereafter). In fact, the phylogenetic relationships among the three subclades of J-C-HCX have long been controversial in a series of phylogenetic studies; various relationships, including HCX (J, C), J (C, HCX) or C (J, HCX) were supported by different datasets and/or analyses35,36,39,40,41,42,43,44.

Plastid phylogenomics has been successfully used to determine difficult-to-resolve low-level relationships of plant groups45,46,47,48,49,50. In this study, we investigated 10 newly sequenced plastomes and seven previously published ones, representing 11 of the 13 genera in this subfamily, to resolve the intergeneric relationships of Cupressoideae. One or two representative species from each of the subfamilies Cunninghamioideae, Sequoioideae, Taiwanioideae and Taxodioideae were included as outgroups. Phylogenetic analyses based on original protein-coding genes (PCGs) suggested a sister relationship between Juniperus and Cupressus (Fig. 1). However, both Juniperus and Cupressus have long stem branches, so LBA may explain this relationship. In this case, plastid phylogenomics could be used to verify the effectiveness of the multiple strategies previously mentioned in alleviating the LBA artifact and reconstructing a robust Cupressoideae phylogeny. Comparative analyses based on data filtering and modifying, evolutionary model selection and coalescent phylogenetic reconstruction were used to explore efficient methods to alleviate the LBA artifact on the phylogenetic reconstruction of the J-C-HCX clade and resolve the intergeneric relationships of Cupressoideae.

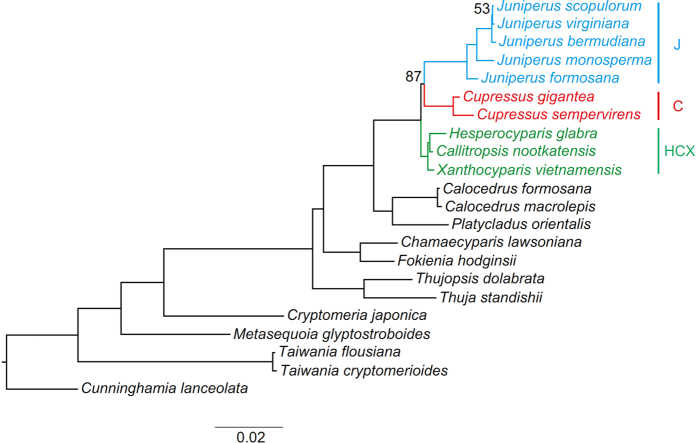

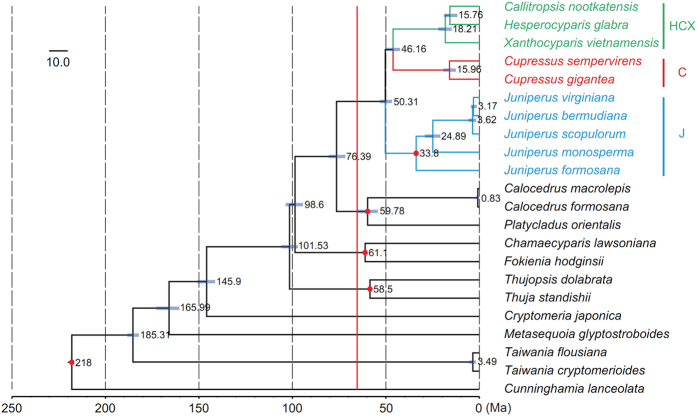

Figure 1. Phylogeny of Cupressoideae by maximum likelihood (ML) analysis of the PCG matrix under the GTRGAMMA model.

Support for the branches was estimated from 1,000 bootstrapping replicates. The numbers on branches are bootstrap support values, and bootstrap values of 100% are not shown.

Results

Sequence characteristics of data matrices

The PCG matrix has an aligned length of 81,423 bp with 11,394 bp parsimony-informative sites (Table 1). The characteristics of modified matrices from PCG by various filtering methods are in Table 1.

Table 1. Sequence characteristics of the applied data matrices.

| Datasets | No. of sites (bp) | No. of variable sites (bp) | No. of parsimonious-informative sites (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCG | 81,423 | 17,882 | 11,394 |

| PCG12 | 54,282 | 9,596 | 6,055 |

| AA | 27,141 | 7,613 | 5,117 |

| PCG-GB-relaxed | 74,528 | 16,278 | 10,765 |

| PCG-GB-default | 68,588 | 12,797 | 8,345 |

| PCG-GB-strict | 63,299 | 9,900 | 6,227 |

| PCG-Iss-9 | 28,494 | 10,867 | 7,160 |

| PCG-Iss-73 | 52,929 | 7,015 | 4,234 |

| PCG-slope-12 | 28,995 | 11,045 | 7,290 |

| PCG-slope-70 | 52,428 | 6,837 | 4,104 |

| PCG-R2-11 | 19,362 | 7,801 | 5,215 |

| PCG-R2-71 | 62,061 | 10,081 | 6,179 |

| PCG-OV-slow-partition | 10,286 | 10,286 | 3,798 |

| PCG-OV-medium-partition | 10,286 | 10,286 | 3,798 |

| PCG-OV-fast-partition | 10,286 | 10,286 | 3,798 |

| PCG-TIGER-slow-partition | 10,286 | 10,286 | 3,798 |

| PCG-TIGER-medium-partition | 10,286 | 10,286 | 3,798 |

| PCG-TIGER-fast-partition | 10,286 | 10,286 | 3,798 |

| PCG-OV-sorted | 77,173 | 13,632 | 7,810 |

PCG, PCG12, AA, PCG-GB-relaxed, PCG-GB-default, PCG-GB-strict, PCG-Iss-9, PCG-Iss-73, PCG-slope-12, PCG-slope-70, PCG-R2-11, PCG-R2-71, PCG-OV-slow-partition, PCG-OV-medium-partition, PCG-OV-fast-partition, PCG-TIGER-slow-partition, PCG-TIGER-medium-partition, PCG-TIGER-fast-partition and PCG-OV-sorted are explained in Materials and Methods.

Intergeneric relationships of Cupressoideae

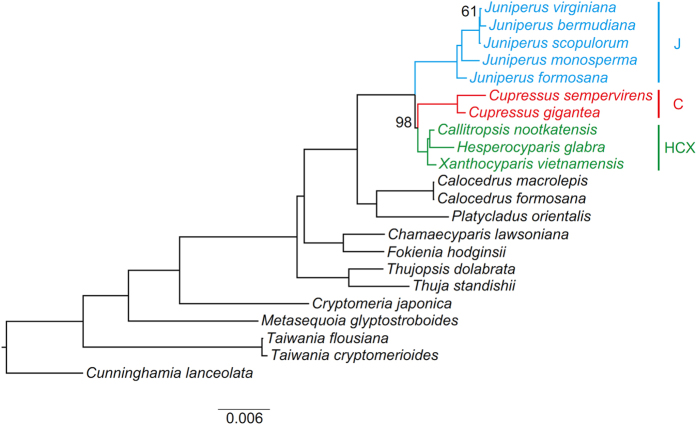

The ML analysis of the PCG matrix fully resolved the intergeneric relationships of Cupressoideae (Fig. 1). Thuja-Thujopsis was resolved as the first diverged clade, and Chamaecyparis-Fokienia as second, then sister pairs of Calocedrus-Platycladus and J-C-HCX. Analyses of matrices including PCG-OV/TIGER-slow/medium-partition and PCG-OV-sorted showed low resolution on intergeneric relationships of Cupressoideae (Supplementary Fig. S1g,h). Other analyses of PCG12, AA, PCG-GB-relaxed/default/strict, PCG-Iss-9/73, PCG-slope-12/70, PCG-R2-11/71, PCG-OV/TIGER-fast-partition, PCG-GTR-CAT and PCG-ASTRAL recovered the same relationships as for PCG except relationships in J-C-HCX (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 2. Phylogeny of Cupressoideae by the ML analysis of the PCG-Iss-73 matrix under the GTRGAMMA model.

Support for the branches was estimated from 1,000 bootstrapping replicates. The numbers on branches are bootstrap support values, and bootstrap values of 100% are not shown.

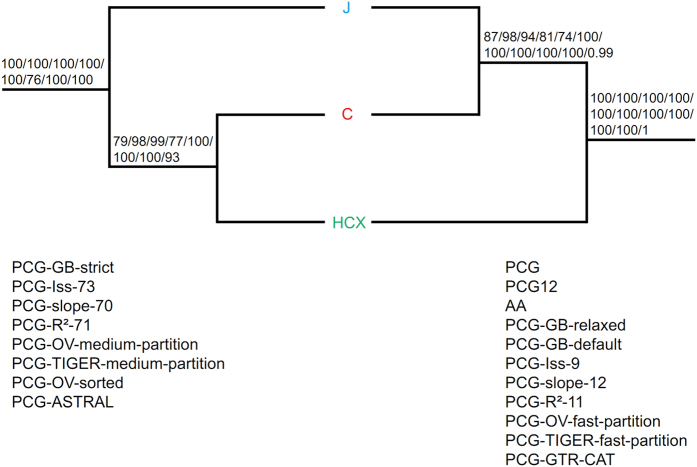

For J-C-HCX, HCX (J, C) was resolved in analyses of PCG, PCG12, AA, PCG-GB-relaxed/default, PCG-Iss-9, PCG-slope-12, PCG-R2-11, PCG-OV/TIGER-fast-partition, PCG-GTR-CAT (Figs 1 and 3; Supplementary Fig. S1a–h,j). However, a relationship of J (C, HCX) was supported in analyses of PCG-GB-strict, PCG-Iss-73, PCG-slope-70, PCG-R2-71, PCG-OV/TIGER-medium-partition, PCG-OV-sorted and PCG-ASTRAL (Figs 2 and 3; Supplementary Fig. S1c,e–h,k).

Figure 3. Reduced schematic trees showing different relationships and support inferred from all analyses.

Two topologies resolved by analyses are shown. The left J (C, HCX) was supported by analyses of PCG-GB-strict, PCG-Iss-73, PCG-slope-70, PCG-R2-71, PCG-OV-medium-partition, PCG-TIGER-medium-partition, PCG-OV-sorted and PCG-ASTRAL, and bootstrap values from each analysis are shown on branches. The right HCX (J, C) was supported by analyses of PCG, PCG12, AA, PCG-GB-relaxed, PCG-GB-default, PCG-Iss-9, PCG-slope-12, PCG-R2-11, PCG-OV-fast-partition, PCG-TIGER-fast-partition and PCG-GTR-CAT, and bootstrap values are shown on branches. The complete topologies inferred from these datasets are in Figs 1 and 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1.

Comparisons of branch lengths of subclades J, C and HCX in multiple analyses

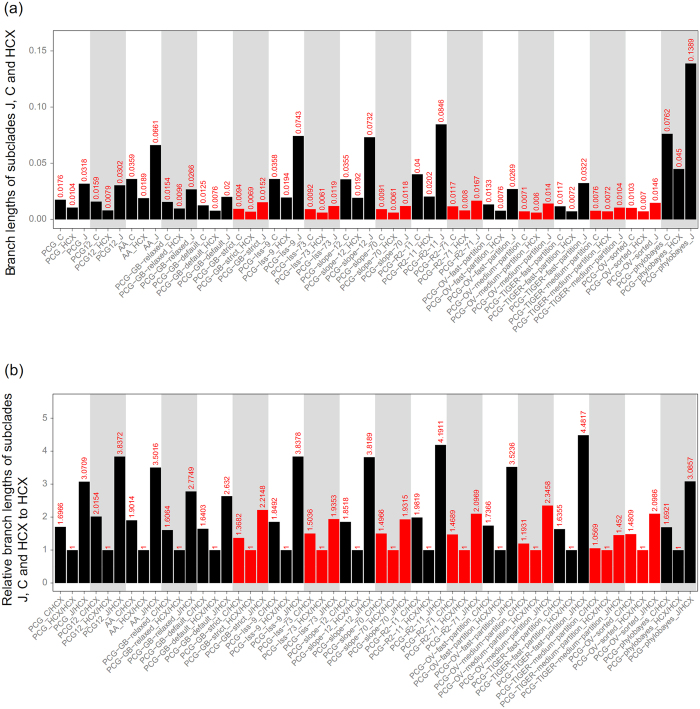

Branch lengths of all three subclades were significantly reduced in analyses of PCG-GB-strict, PCG-Iss-73, PCG-slope-70 and PCG-R2-71 (Fig. 4a), and branch lengths of subclades J and C were reduced in analyses of PCG-OV/TIGER-medium-partition and PCG-OV-sorted (Fig. 4a). For analyses resolving J (C, HCX), the branch length ratio of subclades C to HCX ranged from 1.0569 to 1.5036 and ratio of J to HCX from 1.4520 to 2.3458 (Fig. 4b). For analyses resolving HCX (J, C), the branch length ratio of C to HCX ranged from 1.6064 to 2.0154 and ratio of J to HCX from 2.632 to 4.4817 (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Comparison of branch lengths of subclades J, C and HCX in multiple analyses.

The branch lengths for each of three subclades were calculated from the ML trees shown in Figs 1 and 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1. (a) Branch lengths for each subclade. The numbers above bars are branch length values. (b) Relative branch lengths of subclades J, C and HCX to HCX. The numbers above bars are the branch length ratio for each of three subclades relative to HCX.

Divergence time estimations

The estimated divergence times based on matrices for PCG-Iss-73 (Fig. 5; Table 2) and PCG (Supplementary Fig. S5; Supplementary Table S4) were similar. By the PCG-Iss-73 matrix, the divergence time between subclades J and C-HCX was estimated at 50.31 million years ago (Ma; 46.84 to 53.34 Ma), and the split between C and HCX at 46.16 Ma (42.45 to 50.24 Ma) (Fig. 5; Table 2). By the PCG matrix, the divergence of subclades J-C from HCX was estimated at 48.79 Ma (47.48 to 50.29 Ma) and between subclades J and C at 47.64 Ma (46.16 to 48.87 Ma) (Supplementary Fig. S5; Supplementary Table S4). Our divergence time estimations are robust to topology differences.

Figure 5. Chronogram of Cupressoideae based on the PCG-Iss-73 matrix inferred by using treePL.

Blue bars represent the minimum and maximum estimation of node ages. Red dots represent fossil calibration points in Supplementary Table S3. Red line indicates the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary.

Table 2. Estimated divergence time for the Cupressoideae clades based on the PCG-Iss-73 matrix.

| Clade | PL point (Ma) | PL min (Ma) | PL max (Ma) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crown of Cupressoideae | 101.53 | 97.08 | 105.87 |

| Crown of Thuja-Thujopsis clade | 58.50 | 58.50 | 58.50 |

| MRCA of Chamaecyparis and Juniperus | 98.60 | 94.42 | 103.54 |

| Crown of Chamaecyparis-Fokienia clade | 61.10 | 61.10 | 61.10 |

| MRCA of Platycladus and Juniperus | 76.39 | 71.67 | 80.61 |

| MRCA of Platycladus and Calocedrus | 59.78 | 54.27 | 65.34 |

| Crown of J-C-HCX clade | 50.31 | 46.84 | 53.34 |

| Crown of Juniperus | 33.80 | 33.80 | 33.80 |

| Crown of C-HCX subclade | 46.16 | 42.45 | 50.24 |

| Crown of HCX subclade | 18.21 | 14.88 | 22.01 |

| MRCA of Hesperocyparis and Callitropsis | 15.76 | 11.68 | 18.87 |

Penalized likelihood (PL) point represents the point age estimation in the maximum likelihood best tree. PL min and PL max represent the minimum and maximum estimations by 1,000 maximum likelihood bootstrap trees. Ma: million years ago. MRCA: most recent common ancestor. J-C-HCX: Juniperus-Cupressus-Hesperocyparis-Callitropsis-Xanthocyparis.

Discussion

Plastid phylogenomics fully resolved relationships among sampled genera of Cupressoideae with high support (Figs 1 and 2; Supplementary Fig. S1). We resolved Thuja-Thujopsis as diverging first, then Chamaecyparis-Fokienia. Our results agree with those of Mao et al.35 and most analyses of Yang et al.36. However, analyses of the nuclear LFY of Yang et al.36 resolved reverse relationships, and their mitochondrial rps3 resolved a monophyletic Chamaecyparis-Fokienia clade nested with a paraphyletic Thuja-Thujopsis clade. Our analyses of PCG-GB-strict, PCG-Iss-73, PCG-slope-70, PCG-R2-71, PCG-OV/TIGER-medium-partition, PCG-OV-sorted and PCG-ASTRAL resolved a relationship of J (C, HCX) (Figs 2 and 3; Supplementary Fig. S1c,e–i,k). This result agrees with previous analyses of plastid markers35,36,42 or combined plastid and nuclear matrix molecular analyses35,41. However, a relationship of HCX (J, C) was supported by the nuclear markers of Needly36,40, ABI342 and Leafy36, the mitochondrial marker of rps336, combined plastid markers44, and combined plastid and nuclear markers36. This topology was also recovered by some of our analyses involving original or slightly modified matrices or more complex models (Figs 1 and 3; Supplementary Fig. S1a–h,j). A relationship C (J, HCX) was also resolved by nrITS39,40,42,44, Needly44 and combined plastid and nuclear markers42,44.

Most previous analyses of plastid data except that of Terry and Adams44 revealed a relationship J (C, HCX). We also revealed this relationship with analyses of data matrices by removing unreliable aligned regions, substitution saturation genes and rapidly evolving sites or coalescent phylogenetic reconstruction on 82 aligned PCGs. The branch lengths of J and C were significantly reduced in these analyses (Fig. 4a). The branch length ratios of J and C relative to HCX in analyses of resolved J (C, HCX) were all much smaller than those in analyses of resolved HCX (J, C) (Fig. 4b). The LBA between subclades J and C and ancient rapid divergence [within 4.15 My between 46.16 and 50.31 Ma for J (C, HCX), or within 1.15 My between 48.79 and 47.64 Ma for HCX (J, C)] among three subclades (Fig. 5; Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S5; Supplementary Table S4) should jointly explain the long controversy about their relationships.

Filtering out unreliable alignment regions has been found critical for accurate phylogenetic inference51. Data filtering is sometimes efficient in reducing LBA in systematic analyses25. We recovered the relationship J (C, HCX) when using the strict strategy (PCG-GB-strict) (Supplementary Fig. S1c). Data filtering by using default or relaxed strategies (PCG-GB-relaxed/default) could also reduce the branch lengths of the subclades J and C to a certain degree (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. S1c); however, the resolved HCX (J, C) was probably due to unremoved homoplastic mutations along the stem of subclades J and C. In this study, data filtering by Gblocks was efficient in reducing the LBA artifact.

Rapidly evolving sites could accumulate multiple mutations, which tend to be saturated and contribute to LBA52,53,54. Although the plastome has usually been considered a single linked locus, processes such as recombination, gene conversion, heteroplasmy, and incomplete lineage sorting may also cause a heterogeneous evolutionary rate among different plastid genes55,56,57,58,59,60. The concatenated plastome dataset composed of subsets with different evolutionary rates could generate well-supported but conflicting phylogenetic topologies32,61. An effective way to reduce the effect of LBA is to remove rapidly evolving data62. For example, the phylogenetic position of Gnetales has long been controversial; the sister relationships between Gnetales and cupressophytes (the “Gnecup” hypothesis) seems to be caused by LBA. Removing rapidly evolving genes and three genes (psbC, rpl2 and rps7) that experienced many parallel amino acid substitutions supported a sister relationship between Gnetales and Pinaceae (the “Gnepine” hypothesis)10. The “Gnepine” hypothesis was also supported when excluding 2,250 of the mostly varied sites from the plastome matrix27. Removing saturated genes (PCG-Iss-73, PCG-slope-70, PCG-R2-71) significantly reduced branch lengths of the subclades J and C and recovered J (C, HCX) (Figs 2 and 4; Supplementary Fig. S1e,f). In addition, J (C, HCX) was supported when using the PCG-OV/TIGER-medium-partition including moderately evolving sites (Supplementary Fig. S1g,h). Furthermore, analysis of PCG-OV-sorted strongly favored J (C, HCX) when removing 4,250 mostly varied sites (Supplementary Fig. S1i). However, analyses of PCG-Iss-9, PCG-slope-12, PCG-R2-11 and PCG-OV/TIGER-fast-partition strongly supported HCX (J, C), which should be affected by LBA. In agreement with previous studies10,27,28,54,63, our results once again suggested LBA to be related to rapidly evolving sites.

Furthermore, we also found that the coalescent tree-building method (PCG-ASTRAL) could alleviate the LBA artifact in J-C-HCX. The coalescent method has been considered to better accommodate topological heterogeneity among gene trees32,61. This method is based on summary statistics calculated across all gene trees; a small number of outlier genes that significantly deviate from the coalescent model have relatively little effect on the accurate inference of the species tree64. The coalescent method may be efficient in reducing LBA32,33. Our coalescent analyses recovered J (C, HCX), which further supported the efficiency of this method in reducing the LBA artifact (Supplementary Fig. S1k).

Analyses of PCG12, AA and PCG-GTR-CAT have been found efficient in reducing LBA. More silent substitutions were suggested to occur at third codon positions, which should be downweighted in phylogenetic reconstruction65,66. Excluding third-codon positions has been used to reduce LBA and recovered monophyletic gymnosperms with Gnetales as sister to conifers21. In contrast, when including third-codon positions, gymnosperms were paraphyletic and Gnetales were inferred as sister to all other seed plants. Analyses of amino acids instead of nucleotides have been suggested to reduce systematic error introduced by substitutional saturation and to reduce LBA for reconstructing accurate phylogenetic relationships22,23,24. The site-heterogeneous mixture CAT model may be used to deal with heterotachy67 and has been found quite effective in overcoming the effect of LBA24,29,30,31. However, these three methods support a relationship of HCX (J, C) (Supplementary Fig. S1a,b,j), so they may not alleviate the effect of the LBA artifact in J-C-HCX.

Some previously reported methods have been efficient in reducing relative branch lengths of subclades J and C, and the LBA artifact was alleviated in phylogenetic reconstruction of J-C-HCX. However, some valid methods for other taxa are inefficient in reducing the LBA artifact and recovering HCX (J, C). As mentioned previously, LBA could be produced by complex sources. Different methods are appropriate for different groups. Multiple strategies should be carefully considered and justified to reduce LBA in phylogenetic reconstruction.

Materials and Methods

Taxon sampling

Young, fresh leaves were sampled from 10 species representing nine genera of the subfamily Cupressoideae from the Botanical Garden of the Kunming Institute of Botany (KIB), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), or from the field in the island of Taiwan (Supplementary Table S1). Vouchers were deposited in the herbarium at KIB, CAS (KUN). A total of 22 Cupressaceae species representing five of seven subfamilies were included in this study, among which 17 species represent 11 of 13 genera of the subfamily Cupressoideae, with five species from the subfamilies Cunninghamioideae, Sequoioideae, Taiwanioideae and Taxodioideae used as outgroups (Supplementary Table S1). Because of inaccessibility, we were unable to obtain any samples of Microbiota or Tetraclinis. For J-C-HCX, we collected representative species for each of three genera of HCX; we also sampled two or more species to represent lineage diversification of Cupressus and Juniperus based on previous studies35,41.

Plastid DNA extraction and sequencing

Pure plastid DNA was extracted from about 50 g of fresh leaves68,69. The concentration and sample integrity of the extracted plastid DNA were confirmed by using a Qubit Fluorometer (Beijing Genomics Institute [BGI], Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) and agarose gel electrophoresis. A 50 mg sample of purified DNA was fragmented and used to construct short-insert libraries according to the manufacturer’s manual (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The plastome was sequenced by using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform at BGI. For each species, approximately four million 90 bp paired-end reads from a 500 bp insert library were produced.

Reads filtering, plastome assembly and annotation

The BGI sequencing platform was used for preliminary filtering of raw reads. We used the NGS QC Toolkit70 for further quality control, and 2.39% to 7.73% of low-quality reads were rejected. Then, high-quality paired-end reads were de novo assembled by using the CLC Genomic Workbench v7.0.3 (CLC Inc., Arhus, Denmark) with the default parameters (word size = 64). A single contig with the full-length consensus sequence was acquired for each of the 10 sampled species. The accuracy of the assembled plastomes was further verified by using SOAPdenovo271. The contigs were then aligned with the reference plastome of Cryptomeria japonica (GenBank accession no. NC_010548) by using local BLAST, and aligned contigs were ordered by using Geneious R8 (http://www.geneious.com/)72 according to overlaps and the reference plastome. To further validate the plastome assembly, Illumina paired-end reads were mapped onto the consensus sequences by using Bowtie v2.0.0-beta473. Discrepancies were corrected according to the majority of mapped reads.

The plastomes were initially annotated by using Dual Organellar GenoMe Annotator (DOGMA)74. The exact boundaries of the annotated genes were manually verified by alignment with orthologs in other published gymnosperm plastomes. The tRNA genes were further determined by using tRNAscan-SE (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/)75. The 10 annotated plastome sequences have been deposited in GenBank (accession nos KX832620-KX832629).

Plastome sequence alignment, concatenation and phylogenetic analysis

The 82 protein-coding genes shared by 22 annotated plastomes were extracted by using bedtools76. The codon-based alignment of each gene involved use of MUSCLE77 implemented in MEGA v6.0678. Then, 82 aligned genes were concatenated to one supermatrix (PCG with 81,423 nt).

The PCG matrix was used for primary phylogenetic inference. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis involved use of RAxML v8.1.1179 at the XSEDE Teragrid of the CIPRES science Gateway (http://www.phylo.org/)80, including tree robustness assessment with 1,000 rapid bootstrap replicates with the GTRGAMMA substitution model.

Data filtering and modifying, evolutionary model selection and coalescent phylogenetic reconstruction

A series of strategies including data filtering and modifying, evolutionary model selection and coalescent phylogenetic reconstruction were used to alleviate the potential effect of the LBA artifact on phylogenetic reconstruction.

Data filtering and modifying

We used a series of data filtering and modifying of the PCG matrix (1) using only the first and second codon positions (the “PCG12” matrix); (2) using amino acid data (the “AA” matrix) (ProtTest v381 was used to infer the optimal model of sequence evolution under Bayesian information criterion); and (3) removing unreliable aligned regions. Gblocks v0.91b51,82 was used to filter the unreliable aligned regions. Relaxed, default and strict parameters (“Minimum Number of Sequences for a Conserved Positions” = 11/11/21, “Minimum Number of Sequences for a Flank Position” = 11/17/21, “Maximum Number of Contiguous Nonconserved Positions” = 10/8/5, “Minimum Length of a Block” = 5/10/50 and “Allowed Gap Positions” = “With Half/None/None”) were used to produce the “PCG-GB-relaxed/default/strict” matrices, respectively.

Fourth, we excluded substitution saturation genes. The substitution saturation index (Iss) defined by Xia et al.83 was used to determine the potential phylogenetic signal for each of 82 aligned PCGs by using DAMBE v6.1.984. If the value of Iss is lower than that of Iss.c for a symmetrical and an asymmetrical tree, the orthologous genes have not experienced substitution saturation and contain a phylogenetic signal for recovering true evolutionary relationships83. The “PCG-Iss-9” matrix comprised 9 saturated genes with Iss values significantly higher than that of Iss.c (Supplementary Table S2). In addition, the linear regression of Patristic distance and uncorrected p distance was used to determine the degree of substitution saturation for each of 82 PCGs by using TreSpEx v1.185. Density distributions of the slope or R2 value were plotted by using R v3.2.2 (R Development Core Team 2012). Genes located in left shoulders of the slope or R2 density plots were considered saturated. The “PCG-slope-12” and “PCG-R2-11” matrices were built by using 12 and 11 detected saturated genes (Supplementary Fig. S2). The “PCG-Iss-73”, “PCG-slope-70” and “PCG-R2-71” matrices were built by removing saturated genes detected in these two analyses.

Fifth, we built rate-partitioned data subsets. Observed variability (OV)86 and Tree Independent Generation of Evolutionary Rates (TIGER)87 methods were used to measure the relative evolutionary rate for each of the aligned nucleotide sites in PCG. Using methods previously described32,54,61,63, we explored the distribution of signal in PCG by separating the moderately evolving sites from the slowly and rapidly evolving sites (Supplementary Fig. S3). First, we sorted all parsimony-informative sites (PISs) in a concatenated dataset based on estimated evolutionary rate. Then, we divided these PISs into three partitions with equal number of PISs (i.e. slow, medium and fast partitions). The sites in the second tertiles (moderately evolving sites) were used for phylogenetic reconstruction and the sites in the first and third tertiles (slowly and rapidly evolving sties) were used for comparison. Next, all parsimony uninformative sites (PUIS) and constant sites were included in each of three partitions for proper model estimation. The “PCG-OV-slow/medium/fast-partition” matrices and the “PCG-TIGER-slow/medium/fast-partition” matrices were finally obtained.

Sixth, we removed the most rapidly evolving sites. We used OV sorting as described86 to rank the PCG matrix from the mostly varied sites to the mostly conserved sites based on measuring character state variation in each alignment position. Then a series of alignments was generated by successively removing the mostly varied sites from the OV-sorted alignment in increments of 250. For each step, two data partitions were obtained: (1) “A” partitions comprising the shortened OV-sorted alignment and (2) “B” partitions containing the mostly varied sites. After model fitting for each partition by using ModelTest88, the ML distances for A and B partitions and the uncorrected p distances for B partitions were calculated by using PAUP*89. Two Pearson correlation analyses of pairwise distances were conducted at each step, correlating the 1) ML distances for A and B partitions and 2) ML and uncorrected p distances for B partitions (Supplementary Fig. S4b). The stopping point for site removal was determined as the point at which the two correlations showed a significant increase86. A sharp increase in Pearson correlation coefficient (r) occurred when removing 3,750 sites (position 77,673), and stopped when removing 4,250 sites (position 77,173) (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Goremykin et al.86 suggested that varied sites be removed until the end of the sharp increase in these two correlation analyses. Therefore, the optimal stopping point for varied site removal was identified at position 77,173 (“PCG-OV-sorted”) (Supplementary Fig. S4b). The ML phylogenetic reconstruction under a GTRGAMMA model and the bootstrap support measurement of alternative hypotheses, HCX (J, C), J (C, HCX) and C (J, HCX), were performed for each partition (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Supplementary Fig.S4a shows that HCX (J, C) was highly supported by including 1,750 mostly varied sites (position 79,673). J (C, HCX) was strongly supported by removing 2,250 (position 71,973) to 6,000 (position 75,423) mostly varied sites (position 71,973).

Evolutionary model selection

PhyloBayes v3.290 was used to build Bayesian inference trees (PCG-GTR-CAT) for PCG with a site-heterogeneous mixture model, GTR-CAT67. Two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo chains were run for 45,600 cycles. The first 20% cycles were discarded as burn-in. Convergence of these two runs was determined when the discrepancies reached 0.3 (maxdiff < 0.3) and the minimum effective size was larger than 50.

Coalescent phylogenetic reconstruction

For the coalescent method, an individual gene tree for each of 82 PCGs was inferred by using RAxML with the GTRGAMMA substitution model. Species trees were reconstructed with the 82 estimated gene trees by using ASTRAL (PCG-ASTRAL)91,92.

Divergence time estimations

Dating analyses involved a relaxed clock method, penalized likelihood93 in treePL94, which could smooth rate changes between adjacent branches of the phylogeny by applying a penalty93. The ML trees with branch length generated by RAxML analysis of the PCG-Iss-73 and PCG matrices were used as the input trees. This method applied a smoothing parameter, λ, to determine the magnitude of the penalty. The optimal smoothing value was determined empirically by using cross-validation93,94. For the trees from the PCG-Iss-73 and PCG matrices, the cross-validation tested 13 smoothing values separated by one order of magnitude, starting at 1 × 10−6. Furthermore, the minimum age of the Cupressaceae crown node was constrained at 157.2 Ma as described35. The maximum age of Cupressaceae crown node was assigned as 218 Ma, the estimated mean age of the stem lineage of Cupressaceae35. In addition, minimum age constraints from fossil data35 were applied to another four nodes within Cupressaceae. The detailed fossil calibrations for the five nodes are in Supplementary Table S3. We generated 1,000 ML bootstrap trees with branch lengths by using RAxML. The minimum and maximum age for the internal nodes were calculated from dating 1,000 bootstrap trees by using treePL and TreeAnnotator v1.8.495.

Additional Information

Accession codes: KX832620-KX832629

How to cite this article: Qu, X.-J. et al. Multiple measures could alleviate long-branch attraction in phylogenomic reconstruction of Cupressoideae (Cupressaceae). Sci. Rep. 7, 41005; doi: 10.1038/srep41005 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wei-Bang Sun from Kunming Botanical Garden, KIB/CAS, Kunming, Yunnan and Yu-Chung Chiang from National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, for collecting materials as well as Zhi-Rong Zhang, Si-Yun Chen, Jun-Bo Yang and Hong-Tao Li at the molecular laboratory of the Germplasm Bank of Wild Species, KIB/CAS for technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (grant no. 2014CB954100-01), the iFlora Cross and Cooperation team (31129001), the Applied Fundamental Research Foundation of Yunnan Province (2014GA003) and a Talent Project of Yunnan Province (2011CI042).

Footnotes

Author Contributions T.-S.Y. and D.-Z.L. designed the research. X.-J.Q. conducted the experiments. X.-J.Q. and J.-J.J. analyzed the data. X.-J.Q., T.-S.Y. and S.-M.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Rokas A. & Carroll S. B. Bushes in the tree of life. PLoS Biol. 4, e352 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield J. B. & Lockhart P. J. Deciphering ancient rapid radiations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 258–265 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H. et al. Resolving difficult phylogenetic questions: why more sequences are not enough. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000602 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Cases in which parsimony or compatibility methods will be positively misleading. Syst. Zool. 27, 401–410 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten J. A review of long-branch attraction. Cladistics 21, 163–193 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann H., Van der Giezen M., Zhou Y., De Raucourt G. P. & Philippe H. An empirical assessment of long-branch attraction artefacts in deep eukaryotic phylogenomics. Syst. Biol. 54, 743–757 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajibabaei M., Xia J. N. & Drouin G. Seed plant phylogeny: gnetophytes are derived conifers and a sister group to Pinaceae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 40, 208–217 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleidorn C. et al. On the phylogenetic position of Myzostomida: can 77 genes get it wrong? BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 150 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampl V. et al. Phylogenomic analyses support the monophyly of Excavata and resolve relationships among eukaryotic “supergroups”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3859–3864 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B. J., Yonezawa T., Zhong Y. & Hasegawa M. The position of Gnetales among seed plants: overcoming pitfalls of chloroplast phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 2855–2863 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. S., Wang Y. N., Hsu C. Y., Lin C. P. & Chaw S. M. Loss of different inverted repeat copies from the chloroplast genomes of Pinaceae and cupressophytes and influence of heterotachy on the evaluation of gymnosperm phylogeny. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 1284–1295 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Ezpeleta N. et al. Detecting and overcoming systematic errors in genome-scale phylogenies. Syst. Biol. 56, 389–399 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy M. D. & Penny D. A framework for the quantitative study of evolutionary trees. Syst. Zool. 38, 297–309 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Foster P. G. Modeling compositional heterogeneity. Syst. Biol. 53, 485–495 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jermiin L. S., Ho S. Y. W., Ababneh F., Robinson J. & Larkum A. W. D. The biasing effect of compositional heterogeneity on phylogenetic estimates may be underestimated. Syst. Biol. 53, 638–643 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart P. & Steel M. A tale of two processes. Syst. Biol. 54, 948–951 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedtke S. M., Townsend T. M. & Hillis D. M. Resolution of phylogenetic conflict in large data sets by increased taxon sampling. Syst. Biol. 55, 522–529 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. W. & Iles W. J. D. Different gymnosperm outgroups have (mostly) congruent signal regarding the root of flowering plant phylogeny. Am. J. Bot. 96, 216–227 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick K. S. et al. Improved phylogenomic taxon sampling noticeably affects Nonbilaterian relationships. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 1983–1987 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall M. R. & Ervin A. B. 18S gene trees are positively misleading for monocot/dicot phylogenetics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 30, 97–106 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson M. J., Wojciechowski M. F., Hu J. M., Khan T. S. & Brady S. G. Error, bias, and long-branch attraction in data for two chloroplast photosystem genes in seed plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 782–797 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki Y., Simpson A. G. B., Dacks J. B. & Roger A. J. Phylogenetic artifacts can be caused by leucine, serine, and arginine codon usage heterogeneity: dinoflagellate plastid origins as a case study. Syst. Biol. 53, 582–593 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S., Clements M. D. & Beilstein M. A. A duplicate gene rooting of seed plants and the phylogenetic position of flowering plants. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365, 383–395 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G. & Vila R. What is the phylogenetic signal limit from mitogenomes? The reconciliation between mitochondrial and nuclear data in the Insecta class phylogeny. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 315 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisimova M. et al. State-of the art methodologies dictate new standards for phylogenetic analysis. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 161 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H., Lartillot N. & Brinkmann H. Multigene analyses of bilaterian animals corroborate the monophyly of Ecdysozoa, Lophotrochozoa, and Protostomia. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1246–1253 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B. J. et al. Systematic error in seed plant phylogenomics. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 1340–1348 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goremykin V. V., Nikiforova S. V., Cavalieri D., Pindo M. & Lockhart P. The root of flowering plants and total evidence. Syst. Biol. 64, 879–891 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot N., Brinkmann H. & Philippe H. Suppression of long-branch attraction artefacts in the animal phylogeny using a site-heterogeneous model. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, S4 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann H. & Philippe H. Animal phylogeny and large-scale sequencing: progress and pitfalls. J. Syst. Evol. 46, 274–286 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot N. & Philippe H. Improvement of molecular phylogenetic inference and the phylogeny of Bilateria. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 1463–1472 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z. X., Liu L., Rest J. S. & Davis C. C. Coalescent versus concatenation methods and the placement of Amborella as sister to water lilies. Syst. Biol. 63, 919–932 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Xi Z. X. & Davis C. C. Coalescent methods are robust to the simultaneous effects of long branches and incomplete lineage sorting. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 791–805 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabberley D. J. Mabberley’s plant-book: a portable dictionary of plants, their classification, and uses. 3rd edn (Cambridge University Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Mao K. S. et al. Distribution of living Cupressaceae reflects the breakup of Pangea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7793–7798 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Y., Ran J. H. & Wang X. Q. Three genome-based phylogeny of Cupressaceae s.l.: further evidence for the evolution of gymnosperms and Southern Hemisphere biogeography. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 64, 452–470 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Q. & Ran J. H. Evolution and biogeography of gymnosperms. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 75, 24–40 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadek P. A., Alpers D. L., Heslewood M. M. & Quinn C. J. Relationships within Cupressaceae sensu lato: a combined morphological and molecular approach. Am. J. Bot. 87, 1044–1057 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little D. P., Schwarzbach A. E., Adams R. P. & Hsieh C. F. The circumscription and phylogenetic relateonships of Callitropsis and the newly descriibed genus Xanthocyparis (Cupressaceae). Am. J. Bot. 91, 1872–1881 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little D. P. Evolution and circumscription of the true cypresses (Cupressaceae: Cupressus). Syst. Bot. 31, 461–480 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Mao K. S., Hao G., Liu J. Q., Adams R. P. & Milne R. I. Diversification and biogeography of Juniperus (Cupressaceae): variable diversification rates and multiple intercontinental dispersals. New Phytol. 188, 254–272 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. P., Bartel J. A. & Price R. A. A new genus, Hesperocyparis, for the cypresses of the Western Hemisphere (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 91, 160–185 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. G., Bartel J. A. & Adams R. P. Phylogenetic relationships among the New World cypresses (Hesperocyparis; Cupressaceae): evidence from noncoding chloroplast DNA sequences. Plant Syst. Evol. 298, 1987–2000 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. G. & Adams R. P. A molecular re-examination of phylogenetic relationships among Juniperus, Cupressus, and the Hesperocyparis-Callitropsis-Xanthocyparis clades of Cupressaceae. Phytologia 97, 67–75 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Parks M., Cronn R. & Liston A. Increasing phylogenetic resolution at low taxonomic levels using massively parallel sequencing of chloroplast genomes. BMC Biol. 7, 84 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. P., Huang J. P., Wu C. S., Hsu C. Y. & Chaw S. M. Comparative chloroplast genomics reveals the evolution of Pinaceae genera and subfamilies. Genome Biol. Evol. 2, 504–517 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks M., Cronn R. & Liston A. Separating the wheat from the chaff: mitigating the effects of noise in a plastome phylogenomic data set from Pinus L. (Pinaceae). BMC Evol. Biol. 12, 100 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njuguna W., Liston A., Cronn R., Ashman T. L. & Bassil N. Insights into phylogeny, sex function and age of Fragaria based on whole chloroplast genome sequencing. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 66, 17–29 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P. F., Zhang Y. X., Zeng C. X., Guo Z. H. & Li D. Z. Chloroplast phylogenomic analyses resolve deep-level relationships of an intractable bamboo tribe Arundinarieae (Poaceae). Syst. Biol. 63, 933–950 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhsam M. et al. Does complete plastid genome sequencing improve species discrimination and phylogenetic resolution in Araucaria? Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 1067–1078 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G. & Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst. Biol. 56, 564–577 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann H. & Philippe H. Archaea sister group of bacteria? Indications from tree reconstruction artifacts in ancient phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 817–825 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani D. Identifying and removing fast-evolving sites using compatibility analysis: an example from the Arthropoda. Syst. Biol. 53, 978–989 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling E. A., Peterson K. J. & Pisani D. Phylogenetic-signal dissection of nuclear housekeeping genes supports the paraphyly of sponges and the monophyly of eumetazoa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 2261–2274 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medgyesy P., Fejes E. & Maliga P. Interspecific chloroplast recombination in a Nicotiana somatic hybrid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 6960–6964 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogihara Y., Terachi T. & Sasakuma T. Intramolecular recombination of chloroplast genome mediated by short direct-repeat sequences in wheat species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 8573–8577 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajora O. P. & Dancik B. P. Chloroplast DNA variation in Populus.3. novel chloroplast DNA variants in natural Populus X Canadensis hybrids. Theor. Appl. Genet. 90, 331–334 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe A. D. & Randle C. P. Recombination, heteroplasmy, haplotype polymorphism, and paralogy in plastid genes: implications for plant molecular systematics. Syst. Bot. 29, 1011–1020 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Jakob S. S. & Blattner F. R. A chloroplast genealogy of Hordeum (Poaceae): long-term persisting haplotypes, incomplete lineage sorting, regional extinction, and the consequences for phylogenetic inference. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1602–1612 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C. C., Xi Z. X. & Mathews S. Plastid phylogenomics and green plant phylogeny: almost full circle but not quite there. BMC Biol. 12, 11 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z. X., Rest J. S. & Davis C. C. Phylogenomics and coalescent analyses resolve extant seed plant relationships. PLoS ONE 8, e80870 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostka M., Uzlikova M., Cepicka I. & Flegr J. SlowFaster, a user-friendly program for slow-fast analysis and its application on phylogeny of Blastocystis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 341 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota-Stabelli O. et al. Ecdysozoan mitogenomics: evidence for a common origin of the legged invertebrates, the Panarthropoda. Genome Biol. Evol. 2, 425–440 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Liu L., Edwards S. V. & Wu S. Y. Resolving conflict in eutherian mammal phylogeny using phylogenomics and the multispecies coalescent model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14942–14947 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A., Hansmann S., Samigullin T., Antonov A. & Martin W. Gnetum and the angiosperms: molecular evidence that their shared morphological characters are convergent, rather than homologous. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1006–1009 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Chaw S. M., Parkinson C. L., Cheng Y. C., Vincent T. M. & Palmer J. D. Seed plant phylogeny inferred from all three plant genomes: monophyly of extant gymnosperms and origin of Gnetales from conifers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4086–4091 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot N. & Philippe H. A Bayesian mixture model for across-site heterogeneities in the amino-acid replacement process. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1095–1109 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X. S., Zeng F. H. & Yan L. F. An efficient method for the purification of chloroplast DNA from higher plants. J. Wuhan Bot. Res. 12, 277–280 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R. K. et al. Methods for obtaining and analyzing whole chloroplast genome sequences. Methods Enzymol. 395, 348–384 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R. K. & Jain M. NGS QC Toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS ONE 7, e30619 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R. et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. GigaScience 1, 18 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M. et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B. & Salzberg S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman S. K., Jansen R. K. & Boore J. L. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 20, 3252–3255 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schattner P., Brooks A. N. & Lowe T. M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W686–W689 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A. R. & Hall I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A. & Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. A. et al. A RESTful API for access to phylogenetic tools via the CIPRES Science Gateway. Evol. Bioinform. 11, 43–48 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D., Taboada G. L., Doallo R. & Posada D. ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 27, 1164–1165 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 540–552 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. H., Xie Z., Salemi M., Chen L. & Wang Y. An index of substitution saturation and its application. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 26, 1–7 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. & Xie Z. DAMBE: software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. J. Hered. 92, 371–373 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struck T. H. TreSpEx-detection of misleading signal in ohylogenetic reconstructions based on tree information. Evol. Bioinform. 10, 51–67 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goremykin V. V., Nikiforova S. V. & Bininda-Emonds O. R. P. Automated removal of noisy data in phylogenomic analyses. J. Mol. Evol. 71, 319–331 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins C. A. & McInerney J. O. A method for inferring the rate of evolution of homologous characters that can potentially improve phylogenetic inference, resolve deep divergence and correct systematic biases. Syst. Biol. 60, 833–844 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. & Crandall K. A. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14, 817–818 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4 (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot N., Lepage T. & Blanquart S. PhyloBayes 3: a Bayesian software package for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating. Bioinformatics 25, 2286–2288 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirarab S. et al. ASTRAL: genome-scale coalescent-based species tree estimation. Bioinformatics 30, I541–I548 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirarab S. & Warnow T. ASTRAL-II: coalescent-based species tree estimation with many hundreds of taxa and thousands of genes. Bioinformatics 31, 44–52 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson M. J. Estimating absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times: a penalized likelihood approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 101–109 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. A. & O’Meara B. C. treePL: divergence time estimation using penalized likelihood for large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 28, 2689–2690 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Suchard M. A., Xie D. & Rambaut A. Bayesian Phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1969–1973 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.