Abstract

Functional localization of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in vertebrate muscle and brain depends on interaction of the tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization (WAT) sequence, at the C-terminus of its major splice variant (T), with a proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD), of the anchoring proteins, collagenous (ColQ) and proline-rich membrane anchor. The crystal structure of the WAT/PRAD complex reveals a novel supercoil structure in which four parallel WAT chains form a left-handed superhelix around an antiparallel left-handed PRAD helix resembling polyproline II. The WAT coiled coils possess a WWW motif making repetitive hydrophobic stacking and hydrogen-bond interactions with the PRAD. The WAT chains are related by an ∼4-fold screw axis around the PRAD. Each WAT makes similar but unique interactions, consistent with an asymmetric pattern of disulfide linkages between the AChE tetramer subunits and ColQ. The P59Q mutation in ColQ, which causes congenital endplate AChE deficiency, and is located within the PRAD, disrupts crucial WAT–WAT and WAT–PRAD interactions. A model is proposed for the synaptic AChET tetramer.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase, polyproline II, tetramerization domain, WWW motif, X-ray structure

Introduction

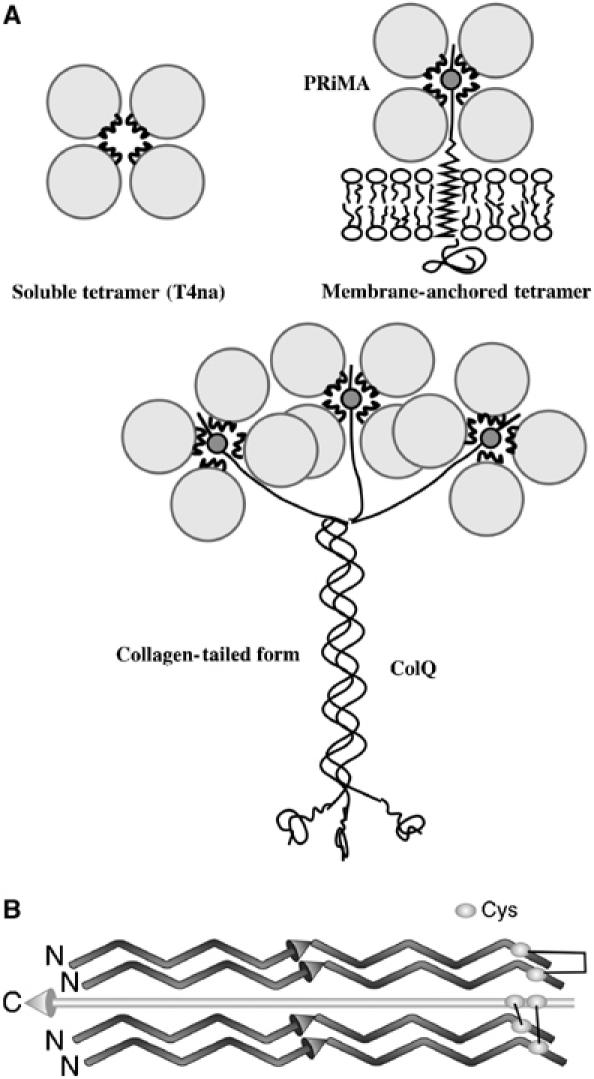

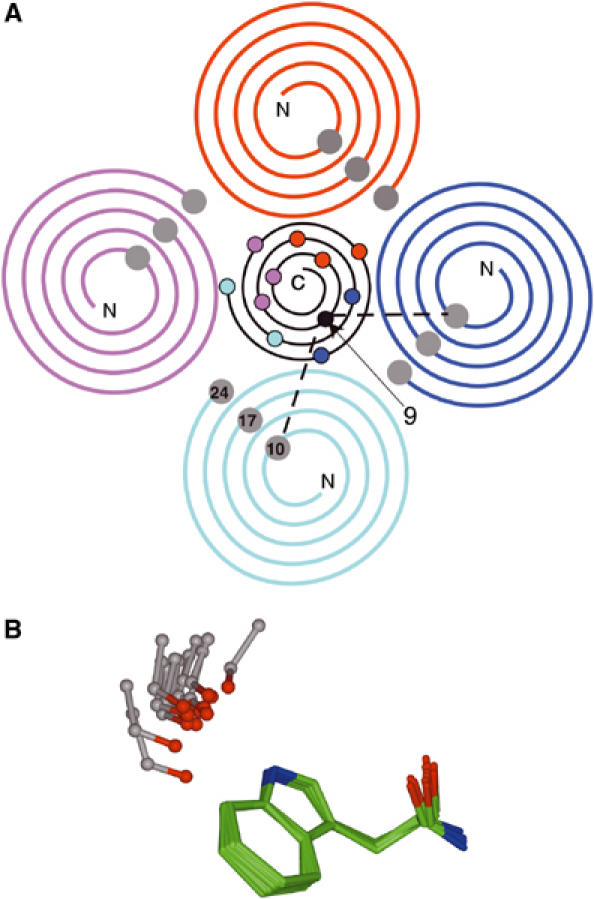

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) terminates signal transmission at cholinergic synapses by rapid hydrolysis of acetylcholine. AChE is expressed as a repertoire of molecular forms differing in quaternary structure and mode of anchoring, whose pattern varies from tissue to tissue, and may reflect the spatial and temporal demands of individual synapses (Silman and Futerman, 1987; Massoulié et al, 1993). This structural polymorphism arises from alternative splicing at the C-terminus and association with structural proteins (Massoulié, 2002). The AChET variant is the only form expressed in the brain and muscles of normal adult mammals (Legay et al, 1995), generating monomers, dimers and tetramers, as well as collagen-tailed (Dudai et al, 1973; Rieger et al, 1973) and hydrophobic-tailed (Gennari et al, 1987; Inestrosa et al, 1987) hetero-oligomers. These are the functional AChE species at vertebrate cholinergic synapses, in which four T-splice variants (AChET) are associated with either a collagenous (ColQ) or a transmembrane (proline-rich membrane anchor (PRiMA)) anchoring protein (Figure 1A). These hetero-oligomeric forms of AChE, and homologous butyrylcholinesterase species (Vigny et al, 1978; Silman et al, 1979), are unique structures. In the collagen-tailed species, one to three AChET tetramers are attached to the collagen strands. In each tetramer, two subunits form disulfide bridges with sulfhydryl groups of the collagen strand through a cysteine near the C-terminus, and the other two are disulfide-linked to each other via the same sulfhydryls (Figure 1B) (McCann and Rosenberry, 1977; Anglister and Silman, 1978). The quaternary structure is maintained even when all interchain disulfides are reduced (Bon and Massoulié, 1976; Anglister et al, 1980), and catalytic and structural subunits still associate when the appropriate cysteines in AChE or ColQ are mutated (Bon and Massoulié, 1997; Kronman et al, 2000; Bon et al, 2003); thus, these disulfides are not required to maintain the quaternary structure.

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of AChE tetramers. (A) Modes of assembly of AChE subunits into tetramers. (B) Orientations of the polypeptide chains and arrangement of disulfide bonds in the [AChET]4ColQ complex deduced by site-directed mutagenesis.

When ColQ was cloned, first from Torpedo (Krejci et al, 1991), and then from rat (Krejci et al, 1997) and humans (Ohno et al, 1998), a proline-rich sequence, close to its N-terminus, was shown to be responsible for attachment of the AChET subunits, and two adjacent conserved cysteines were identified as appropriate candidates for formation of disulfide bridges, with the cysteine near the C-terminus of AChET (Bon and Massoulié, 1997). This sequence was thus named the proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD). Recently, the 20 kDa hydrophobic polypeptide from brain was cloned (Perrier et al, 2002), and named PRiMA, since it, too, contains a functional PRAD which organizes AChET subunits into tetramers, and anchors them via its transmembrane domain.

AChET monomers assemble into stable tetramers in the presence of either synthetic polyproline (Bon and Massoulié, 1997) or PRAD (Giles et al, 1998; Kronman et al, 2000), with no requirement for disulfide bond formation. This interaction requires the highly conserved C-terminal t peptide of AChET, which forms an amphipathic helix (Bon et al, 2003), and was named the WAT (tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization) domain, due to the presence of three highly conserved and equally spaced Trp residues (Trps). WAT, whether alone, or fused to the C-terminus of heterologous proteins, is sufficient to form tetramers with QN, an N-terminal fragment of ColQ containing PRAD (Simon et al, 1998). Thus, assembly of four AChET subunits with one ColQ chain relies on the interactions between the WAT and PRAD sequences. Mutation of the cysteines involved in interchain disulfide bond formation provided evidence that the WAT chains are oriented antiparallel to the PRAD (Bon et al, 2004) (Figure 1B).

Here, we show that the synthetic WAT and PRAD peptides, without cysteines, form a [WAT]4PRAD complex, which can be crystallized. The novel supercoil revealed by its crystal structure is described, and permits proposal of a plausible model for the structure of the collagen-linked AChET tetramer.

Results

Association of the synthetic WAT and PRAD polypeptides

Figure 2 shows the sequences of synthetic human PRAD and WAT. PRAD contains 15 amino acids, corresponding to residues 72–86 in human ColQ, including eight prolines that are highly conserved in higher vertebrates. Synthetic human WAT corresponds to the 40 C-terminal residues of the AChET transcript (544–583 for human, 536–575 for Torpedo), and is here numbered 1–40. Cys37 was replaced by serine in the synthetic WAT, to prevent uncontrolled disulfide bonding, and Met21 by SeMet to permit collection of multiple anomalous diffraction (MAD) X-ray data (Hendrickson, 1991).

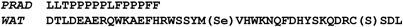

Figure 2.

Amino-acid sequences of synthetic PRAD and WAT. The human AChE WAT sequence was modified at two positions, 21 and 37, to replace Met and Cys by SeMet and Ser, respectively.

To establish whether synthetic WAT and PRAD would associate spontaneously, synthetic PRAD was immobilized on CNBr-activated Sepharose beads, which were incubated with WAT. Bound WAT was then eluted, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE. WAT was retained on PRAD–Sepharose beads, but not on control PRAD-free beads (Figure 3). The same results were obtained with the PRAD used for crystallization and with a PRAD containing cysteines (PRAD2 in Figure 3) as in ColQ (CCLLTPPPPLFPPPFF).

Figure 3.

Binding of WAT to PRAD–Sepharose. WAT aliquots were incubated with PRAD–Sepharose beads. The WAT was eluted and subjected to SDS–PAGE, followed by Coomassie blue staining. The control employed PRAD-free beads. WAT binds to PRAD–Sepharose, but not to control beads.

Overall 3D structure of the [WAT]4PRAD complex

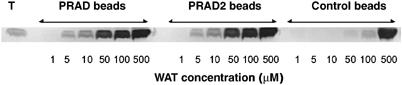

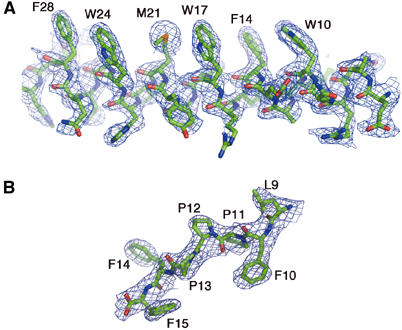

The refined MAD X-ray structure contains two [WAT]4PRAD complexes in the asymmetric unit and 39 water molecules (Figure 4). All 15 residues of both PRADs are seen in the electron density. However, electron density is lacking, primarily at the C-termini, in all eight WAT strands. Although identical in sequence, the four WAT chains are not identical in 3D structure due to the intrinsic nature of the complex. In one complex, chains A, B, C and D interact with chain I of PRAD, while in the other, chains E, F, G and H interact with chain J of PRAD. The complexes are virtually identical (r.m.s.d.=0.42 Å), but can only be superimposed if chain A is overlaid on chain E, B on chain F, etc. If one tries to overlay chain A onto F, G or H, unacceptable fits are obtained in all the three cases.

Figure 4.

Representative electron-density maps of WAT and PRAD in the [WAT]4PRAD structure. (A) Bias-removal map (Reddy et al, 2003), at 2.35 Å resolution, of residues 5–30 of the WATD chain contoured at 1.0σ. The heptad repeat of the Trps is clearly seen. If the seven positions are depicted schematically as a–g, positions a and d are occupied by ‘core' residues; these are usually hydrophobic, and are the key participating residues in interactions between the individual coiled coils of the superhelix. Positions d, corresponding to the three equally spaced Trps, and a (Phe and Met residues) are seen to be on the same side of the amphipathic WAT helix. (B) Bias-removal map of seven C-terminal residues of PRAD contoured at 1.5σ. The excellent fit to the map unequivocally establishes the polarity of the PRAD chain.

In [WAT]4PRAD, four parallel α-helical WATs wrap round a single antiparallel PRAD helix (Figure 5), whose conformation resembles a left-handed polyproline II (PPII) helix (Cowan and McGavin, 1955). It is, however, more tightly wound, having 3.4 versus 3.0 residues per turn, and a pitch of ∼9.7 versus 9.3 Å for PPII (Table I). Each WAT chain assumes a coiled-coil conformation, together forming a supercoil around the PRAD. Thus, the global structure can be described as a left-handed screw (PRAD) within a left-handed threaded hollow tube, which is the superhelix formed by the four WATs.

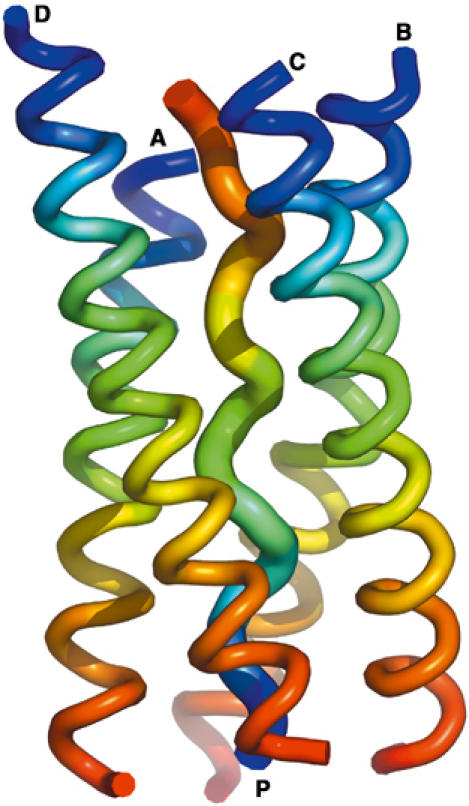

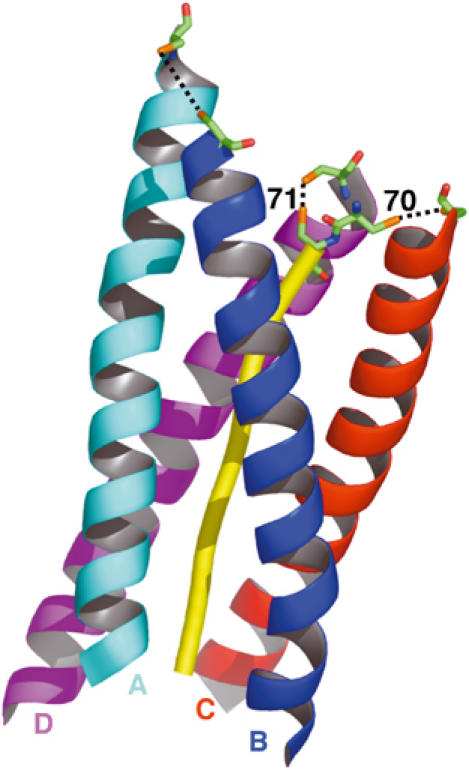

Figure 5.

Ribbon diagram of the overall [WAT]4PRAD crystal structure. View of the four WAT helices wrapped around a single PRAD helix. Color coding is from blue at the N- to red at the C-termini for each chain, showing that the four WATs are parallel, and that PRAD runs antiparallel, with labels at N-termini.

Table 1.

Structural parameters of protein helices

| SS element | N | r (Å) | P (Å/turn) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-helix | +3.6 | 1.5 | 5.5 | |

| WAT | +3.6a | 1.5 | 5.5 | Measured using TWISTER (Strelkov and Burkhard, 2002) |

| PPI | +3.3 | 1.7 | 5.6 | Found in PP peptides dissolved in apolar solvents |

| PPII | −3.0 | 3.1 | 9.3 | Found in many proteins, including collagens |

| PRAD | −3.4 | 2.9 | 9.7 | Measured using Helanal6 (Bansal et al, 2000) |

| N is the number of residues per helical turn, r the helical rise per residue, and P the helical pitch (Bansal et al, 2000; Fleishman and Ben-Tal, 2002). | ||||

| aWith respect to the supercoil axis, it is in fact 3.5. | ||||

Remarkably, even before the first high-resolution crystal structure of an α-helix was observed, coiled coils were accurately described by Crick (1953), consisting of several α-helices twisted around one another to form a supercoil. His model for packing of amino-acid residues at the helix–helix interfaces (‘core'), called ‘knobs-into-holes', holds, in principle, for all known coiled coils (Gruber and Lupas, 2003). This interlocking of side chains requires sequence periodicity of polar and nonpolar residues, the latter usually forming the ‘core'. Coiled coils fulfill a broad repertoire of biological roles, most importantly serving as oligomerization devices (Burkhard et al, 2001).

The [WAT]4PRAD complex is unique inasmuch as its ‘core' residues (Figure 5) interact not with each other, as in all previously known coiled-coil structures, but with the PRAD. Consequently, the superhelical axis coincides with the PRAD helical axis (Figure 6), resulting in an unusually large superhelical radius of 10 Å, and superhelical pitch 157 Å, calculated using TWISTER (Strelkov and Burkhard, 2002).

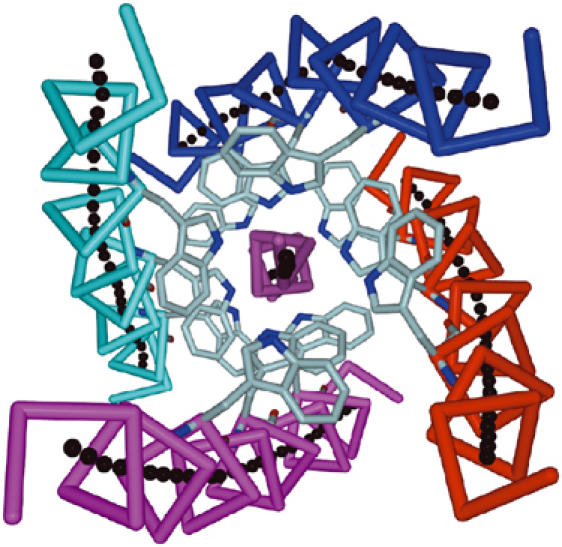

Figure 6.

View of the [WAT]4PRAD structure looking down the superhelical axis. Each of the four WATs (magenta, red, blue and cyan Cα traces) assumes a coiled-coil conformation, together forming a left-handed superhelical structure. The black dots, generated using TWISTER (Strelkov and Burkhard, 2002), trace their axes. The axis of the resultant superhelix coincides with the axis of the PRAD helix (purple), not itself part of the superhelix. The WAT chains are related by ∼4-fold symmetry (around the PRAD), which also extends to the side chains, as illustrated by the conserved Trps (pale blue). Color coding of individual WAT chains is maintained in subsequent figures.

WAT–PRAD interactions: the WWW motif

The precise fit of the side chains of the WAT polypeptides in the interior of the complex is achieved by twisting the right-handed α-helices into coiled coils to form a left-handed supercoil. This effectively reduces their periodicity from 3.6 to 3.5 residues per turn relative to the superhelix axis. Thus, in just two turns, viz. seven residues of the helix, each WAT chain displays heptad repeat, with its three equally spaced Trps (W10, W17 and W24, assigned to positions d of the coiled coil) projecting on the same side of the WAT helix towards the PRAD (Figure 4A).

The key interactions between the WAT and PRAD chains involve residues 10–28 of WAT. In addition to the three conserved Trps, W10, W17 and W24, this stretch also contains F14, M21 and F28, which are assigned to positions a of the coiled coil. The three conserved Trps and M21 interact with the PRAD, whereas F14 and F28 are involved mainly in interactions between adjacent WATs. WAT–PRAD interactions are both hydrophobic and polar. The hydrophobic contacts consist of a series of stacking interactions, mostly between indole rings of the Trps of WAT and the Pro rings on PRAD (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure 1). The Cδ atoms of each WAT-M21 also interact intimately with the PRAD. The polar interactions involve H-bonds (<3 Å) between TrpNɛ1 atoms and the main-chain carbonyls of all the PRAD residues, from position 1 to 11 (Figure 8). From the top down, in Figure 8, successive carbonyls interact with Trps from adjacent WAT chains as follows: the first interacts with W24 of WAT chain A (cyan), the second with W24 of chain B (blue), the third with W24 of chain C (red), the fourth with W24 of chain D (magenta), the fifth reverting to interaction with W17 of chain A, etc. The Trps at corresponding positions on different WAT chains are thus related by a four-fold screw axis, generated by the helical axis of the PRAD, forming a left-handed spiral staircase around it (Supplementary Figure 2). This arrangement is repeated three times, corresponding to the three equally spaced Trps of each WAT, and we thus call it the WWW motif. To the best of our knowledge, this structural motif, of a coiled coil with Trps in its ‘core' positions making both polar and hydrophobic interactions, has not been reported before.

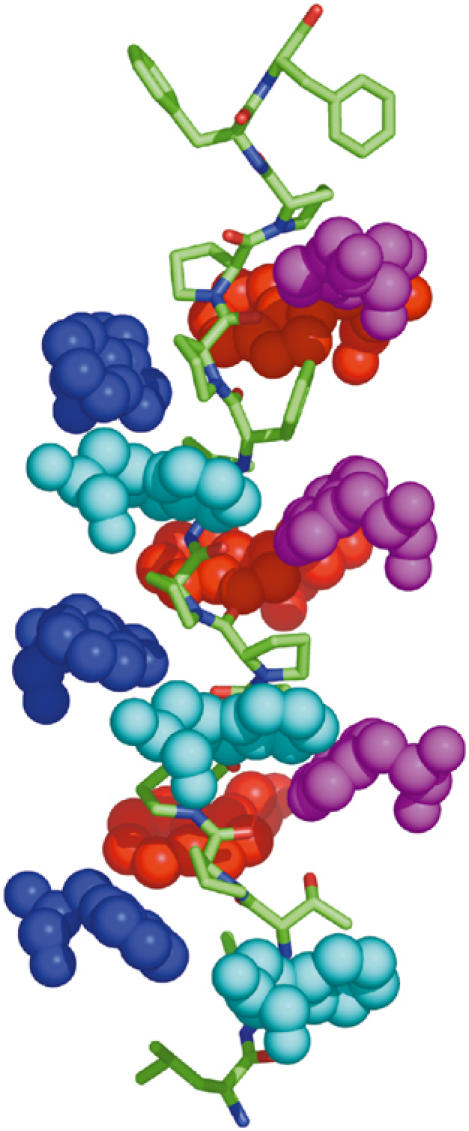

Figure 7.

Stacking interactions between the WAT and PRAD helices. Side view of the complex, with the superhelical axis running vertically, and PRAD depicted as a stick model. Only the Trps of WAT are shown, in space-filling format, with those of each WAT chain colored individually. The Trp side chains form a spiral staircase around the PRAD, fitting into grooves formed by the extended left-handed PRAD helix.

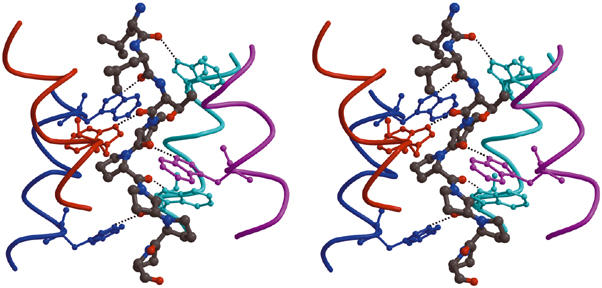

Figure 8.

The WAT–PRAD staircase interactions. Stereo view of part of the structure, showing the hydrogen-bond network. The PRAD (gray ball-and-stick format) is surrounded by the WAT helices (depicted as individually color-coded chains). The distal C-terminal Trps (in ball-and-stick format) of each WAT interact with the main-chain carbonyls at the N-terminus of PRAD (top of the figure). For simplicity, only the first six PRAD residues are shown; however, all the main-chain carbonyls of PRAD (1–11) are within H-bonding distance of the Nɛ1 atoms of the Trp indole rings on the WATs.

WAT–WAT interactions

In addition to strong interactions between the WAT and PRAD helices, there are numerous interactions, mainly hydrophobic and aromatic–aromatic, between neighboring WAT chains in [WAT]4PRAD. Although these do not directly involve the PRAD, the aromatic groups are not fully exposed to the solvent. Perhaps this isolation of the core enhances stability, as might be expected for a complex which holds in place four 65 kDa subunits.

Symmetry and asymmetry of the complex

Although the PRAD helix has only 3.4 residues per turn, and its carbonyls point outwards, with an average residue rotation of 106° (360°/3.4), they can still H-bond to the Trps, which display ca. 90° rotation on successive WAT chains (Figure 6). To overcome this difference in periodicity, the WAT helices, as noted, form a left-handed superhelix as they wrap around the PRAD, positioning their Trps to cover virtually its entire accessible surface. This is achieved by the relatively large Crick angle (Crick, 1952) between the PRAD axis and those of each of the WAT helical axes, that is, an average value of 34°, calculated using TWISTER (Strelkov and Burkhard, 2002), compared to 23° for a leucine zipper supercoil. Consequently, the PRAD carbonyls assume orientations suitable for H-bond interactions with the Trps, with a range of similar, but not identical, geometries (Figure 9). Since there is a phase difference (due to the above-mentioned difference in periodicity), the ninth carbonyl makes a bifurcated H-bond with Trps from two different WATs, so as to ‘reset' the phase. As a result, only 11 PRAD carbonyls interact with the 12 Trps of WAT.

Figure 9.

Reconciliation of the four-fold symmetry of the WAT α-helices and the 3.4-fold symmetry of the PPII of PRAD. (A) Helical wheel representation of [WAT]4PRAD. Four parallel WAT helices (color-coded as in Figure 6) surround the antiparallel PRAD helix (black). Since the WAT helices have ∼3.5 residues per turn, and the conserved Trps (shown as grey balls) are spaced seven residues apart, they are separated by two turns in this representation. n.b. the carbonyl of PRAD residue 9 makes bifurcated H-bonds with Trps of two adjacent WAT chains, TrpA10 and TrpB10. (B) Superposition of the Trp–carbonyl interactions. The coordinates of the 12 sets of interactions between the indole nitrogens of the WAT Trps and the corresponding PRAD main-chain carbonyls were superimposed based solely on the Trp coordinates. The resultant positions of the three atoms of the main-chain carbonyls are shown in ball-and-stick format. The geometries are similar, since all the carbonyls cluster tightly, except for the two interactions made by the ninth PRAD carbonyl, which are at the two extremities of this distribution.

Since the Trps at corresponding positions on neighboring WATs are related by ca. four-fold screw symmetry (Figures 6 and 9), the WAT chains are displaced relative to each other, viewed along the helical axis of the PRAD (Figure 10). Each WAT is displaced ∼2.9 Å relative to its predecessor, corresponding to the rise per residue of the PRAD helix (Table I).

Figure 10.

Asymmetric arrangement of disulfide bridges within the AChET tetramer. The WAT and PRAD peptides utilized in our crystallographic studies lack the cysteines known to make the disulfide bridges shown in Figure 1B. These cysteines (stick format) were, therefore, structurally modeled according to their sequence positions as seen for the corresponding human gene products; two at positions −1 and −2 of PRAD (corresponding to ColQ residues 70 and 71), and one at position 37 of each WAT. The PRAD is rendered as a yellow tube, and the four WAT helices are rendered as ribbons. As inferred from the ∼4-fold screw symmetry, the WAT chains are staggered relative to the PRAD. In this view, in which the N-terminus of the PRAD is at the top, the cyan WAT chain (A) appears the highest, the blue chain (B) below it, then the red (C), with the magenta (D) being the lowest. This staggering imposes strong distance constraints on disulfide bond formation, rendering the two ‘lowest' WATs most likely to interact with the successive cysteines of the PRAD. Consequently, the two highest chains are more likely to interact with one another.

Disulfide bonds

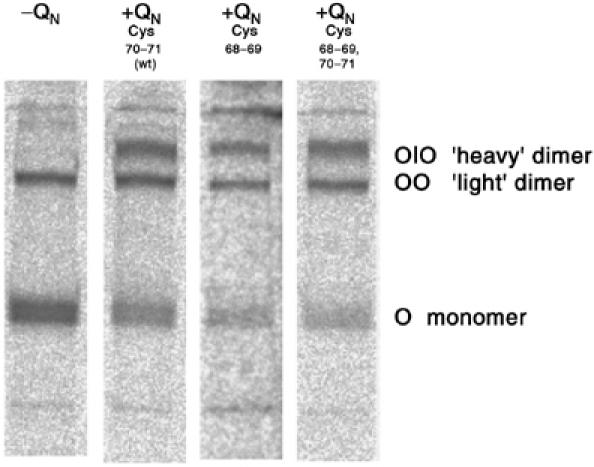

The N-terminal region of ColQ contains adjacent cysteines, Cys70 and Cys71, immediately upstream of the PRAD, which disulfide bond to the Cys37 residues on the WATs from two AChET monomers in the [AChET]4ColQ complex. To determine the importance of their positions, two QN constructs were prepared, containing either two cysteines at positions 68–69 instead of 70–71, or four cysteines at positions 68–71. Surprisingly, like wild-type (wt) QN, both constructs associated with AChET subunits to form [AChET]4QN complexes (Figure 11). In both cases, formation was observed of equal proportions of ‘light' dimers, consisting of two disulfide-linked AChET subunits, and ‘heavy' dimers, consisting of two AChET subunits linked to QN. Thus, cysteines 68–69 of QN can associate with WAT cysteines, even though they are ‘displaced' upstream in the PRAD relative to the wt cysteines, suggesting some flexibility in the region of QN preceding the PRAD. However, the four contiguous cysteines at positions 68–71 did not form disulfide bonds simultaneously with all the four WATs.

Figure 11.

Disulfide bonds between subunits of the [WAT]4QN complex. Nonreducing SDS–PAGE analysis of AChET from cells expressing either no QN (left lane), wt QN or two modified QN polypeptides.

Discussion

The WAT/PRAD interaction is very tight

Although the strength of the WAT–PRAD interaction has not been determined, it is obviously very tight, since no signs of dissociation are detected in very dilute solutions of AChE, in the range of 10−10–10−12 M, employed in analysis of molecular forms by sucrose gradient centrifugation (Jedrzejczyk et al, 1981; Bon et al, 1997; Giles et al, 1998).

Aromatic–PPII interactions

As already mentioned, the PRAD helix resembles PPII, which occurs as three coiled coils in the collagen triple helix (Ramachandran and Kartha, 1954; Rich and Crick, 1955). It is now known, however, that the PPII conformation is not uncommon, occurring also in globular proteins (Adzhubei and Sternberg, 1993).

Interest in PPII helices has increased since some of the most common modular protein recognition domains in eukaryotic signal transduction pathways, for example, the SH3 and WW domains, recognize Pro-rich motifs (Kay et al, 2000; Zarrinpar and Lim, 2000). Indeed, the most frequent motifs in both the Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster genomes are Pro-rich domains (Rubin et al, 2000). Structures of complexes of SH3 domains with a repertoire of Pro-rich motifs (Goudreau et al, 1994; Lim et al, 1994; Musacchio et al, 1994) confirmed the prediction that aromatic residues of SH3 interlock with Pro rings on one face of the PPII helix (Lim and Richards, 1994). A set of nearly parallel aromatic residues form a series of ridges and grooves on the domain surface, against which the PPII helix packs (Zarrinpar and Lim, 2000). Not only do the indole rings fit well within the grooves of the PPII helix, but also their Nɛ1 atoms H-bond to the main-chain carbonyl oxygens of PPII (Musacchio et al, 1994; Jardetzky et al, 1996).

The structure of the [WAT]4PRAD complex, with four identical WWW motifs wrapped around the PRAD, displays these aromatic–PPII stacking and H-bond interactions in their fullest form (Supplementary Figure 3). Each Pro residue in PRAD has a Trp stacked against it. Furthermore, as mentioned, all the PRAD carbonyls H-bond to the Nɛ1 of Trps. Due to the opposite polarities of the WAT and PRAD helices, if the indole of a given WAT Trp stacks against a Pro ring at position i on PRAD, it also H-bonds to the PRAD carbonyl at position i−2. These multiple interactions, of four WAT helices with the PRAD, can serve to associate not only the AChE subunits but also chimeras obtained by attaching a WAT domain at the C-termini of other proteins (Simon et al, 1998).

Organization of interchain disulfide bonds

Mutagenesis, in conjunction with SDS–PAGE (Bon et al, 2004), revealed that one cysteine on each t peptide (corresponding to position 37 in the synthetic WAT) and the two Cys residues of PRAD (corresponding to positions −1 and −2 in our synthetic PRAD) are responsible for the interchain disulfides of [AChET]4ColQ (Figure 2). The t peptides are elongated, parallel to each other, and antiparallel to the PRAD (Bon et al, 2004), as confirmed by the [WAT]4PRAD crystal structure. We have, therefore, generated a model of the extensions of PRAD and WAT, upstream and downstream, respectively (Figure 10). This model defines an arrangement of disulfide bridges, one directly between two subunits and the other two with PRAD (Figure 11). Since the four WAT chains form a four-fold screw around the PRAD, their Cys37 residues are spaced at intervals of 2.9 Å along the PRAD axis, and only the two ‘lowest' chains (color-coded magenta and red in Figure 10) are near the two PRAD cysteines, similarly spaced 2.9 Å apart. The cysteines on the other two WAT chains (blue and cyan in Figure 10) are displaced relative to the lowest chain by two and three rises per residue, respectively, along the PRAD axis, thus being too distant to contact the PRAD cysteines. However, with a minimal change in conformation, they could disulfide bond directly to each other. In both copies of the [WAT]4PRAD complex, chains A and E (corresponding to the ‘highest' chains of the two complexes in Figure 10) are the least well defined in the electron density map, and show the highest B-factors of all eight chains. This flexibility may facilitate disulfide bond formation between two adjacent WAT chains, which are also displaced, relative to each other, by ∼2.9 Å. The model is thus consistent with the biochemical data, supporting the notion that the [WAT]4PRAD structure provides a reasonable representation of the [AChET]4ColQ interaction under physiological conditions. To gain further insight, we utilized site-directed mutagenesis to vary the positions of the Cys residues in QN. When the two cysteines were at positions 68–69, instead of at 70–71 as in wt QN, SDS–PAGE revealed the presence of ‘light' and ‘heavy' dimers, as for wt QN. This suggests that the modified QN forms disulfide bonds with the two ‘lower' WAT chains (C and D), rather than with the two ‘higher' ones (A and B) as seen for PRAD.

We attempted to obtain ‘heavy' tetramers of AChET, in which all four subunits would be disulfide-linked to the PRAD, by constructing a PRAD containing four cysteines at positions 68–71 (PRAD*). However, we found no disulfide-linked tetramers, but, again, the same distribution of ‘light' and ‘heavy' dimers as for wt PRAD. Two explanations may be offered: (a) assuming that assembly of PRAD* is similar to that for PRAD, the orientations of Cys68 and Cys69 may preclude disulfide bond formation with the ‘higher' chains; (b) alternatively, if the WAT chains wrap similarly around PRAD*, but with a shift of one residue relative to PRAD, Cys68 and Cys69 could interact with the ‘lower' chains, and Cys70 and Cys71 would be even more distant from the ‘higher' chains.

Homomeric AChET tetramers

AChET subunits, viz. subunits with a WAT sequence at their C-terminus, also form homomeric nonamphiphilic tetramers in the absence of PRAD (Bon et al, 1997), as do human BChE subunits (Blong et al, 1997). Mutations of aromatic residues, compromise the formation both of homomeric tetramers and QN-linked tetramers similarly, suggesting that the arrangement of WAT peptides in homomeric tetramers resembles that in [WAT]4PRAD (Morel et al, 2001; Belbeoc'h et al, 2003, 2004). Our crystal structure shows that PRAD imposes different constraints on each of the four WAT chains in the complex. However, the staggered arrangement of WAT chains observed in the [WAT]4PRAD structure need not exist for the homotetramer in the absence of QN. Although we have not yet been able to crystallize WAT alone, it is plausible that in the homomeric tetramers the WAT chains also assemble into a superhelix of four parallel WAT coiled coils. They may, however, be in register, rather than staggered, interacting with one another primarily via their hydrophobic faces, possibly adopting the same ‘knobs-into-holes' motif observed in other coiled coils (Burkhard et al, 2001).

AChET also forms amphiphilic tetramers in the absence of PRAD (Bon and Massoulié, 1997; Belbeoc'h et al, 2004). At least some of the WAT aromatic side chains must be exposed to solvent in such tetramers, indicating that they are organized differently from nonamphiphilic homomeric or PRAD-linked tetramers.

Relationship between the [WAT]4PRAD structure and the [AChET]4ColQ complex

The [WAT]4PRAD structure is in excellent agreement with biochemical studies, showing that its formation is compromised to varying degrees by mutating the aromatic residues of WAT (Belbeoc'h et al, 2004). Apart from W10, W17 and W24, WAT contains additional aromatic residues, viz. F14 and F28, which project on the same side of the helix. Assembly of the heteromeric [AChET]4QN complex depends primarily on a four-residue core (F14, W17, Y20 and W24), and to a lesser extent on residues W10 and F28. These data agree well with the structural data, which show that key interactions involve WAT residues 10–28.

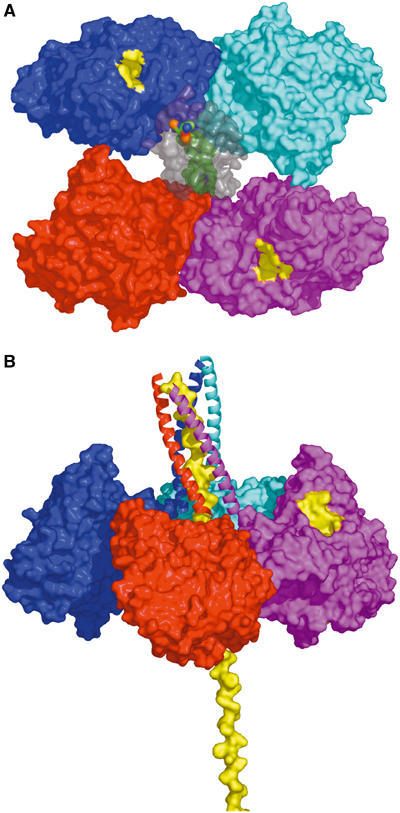

Modeling of [AChET]4ColQ

If the arrangement of the t polypeptides in ColQ-linked AChET tetramers is similar to that in [WAT]4PRAD, strong constraints are imposed on the orientations of the C-terminal residues of the catalytic domains, since they must be accessible for connection to the N-termini of the WAT helices. Moreover, site-directed mutagenesis of AChET subunits (Morel et al, 2001), and low-resolution X-ray studies of EeAChE tetramers, suggests that they assemble with the same dimeric contacts as in the disulfide-linked GPI-anchored TcAChE dimer (Sussman et al, 1991), and in the crystal structures of recombinant monomeric mammalian AChEs (Bourne et al, 1995; Kryger et al, 2000). It is thus plausible that two pairs of catalytic domains, associated as dimers through their four-helix bundles, are arranged such that their C-termini are connected to the N-termini of the four t polypeptides, organized in a [WAT]4PRAD complex similar to that observed here.

The only experimental tetramer structures available are three low-resolution EeAChE structures obtained by trypsinolysis of the collagen-tailed enzyme (Raves et al, 1998; Bourne et al, 1999). They all lack electron density corresponding to the WAT sequence or a fragment of ColQ containing the PRAD sequence, which should be retained after tryptic digestion. However, in the noncompact EeAChE model (PDB 1c2o) (Bourne et al, 1999), which is roughly planar, the C-termini of all four subunits project in about the same direction out of the body of the tetramer, as would be expected for a reasonable connection with the [WAT]4PRAD structure. Manual docking of [WAT]4PRAD onto 1c2o yielded a plausible model of the overall tetramer, except that the distances between its C-termini and the N-termini of the four WAT helices are too large. The model was improved by idealization using CORELS (Sussman et al, 1977; Herzberg and Sussman, 1983). This involved: (a) allowing rigid-body rotation and translation between the two independent structures, that is, [WAT]4PRAD and the EeAChE tetramer; (b) allowing slight rigid-body rotation between the two AChE dimmers; (c) allowing small changes in the conformations of both the N-terminal residues of each WAT and both the C-terminal residues of the catalytic domains. Since the four WAT chains are staggered in the [WAT]4PRAD structure, it is impossible, without substantial distortion of the [WAT]4PRAD and/or the AChE tetramer structures, to dock [WAT]4PRAD along the two-fold axis between the pairs of AChE dimers. In fact, the superhelical axis of the [WAT]4PRAD structure is at an angle of ca. 30° to this two-fold axis.

Figure 12 displays the tetramer model thus obtained. Since PRAD runs antiparallel to the WATs, the continuation of the ColQ polypeptide downstream from the PRAD must traverse the AChE tetramer. In the 1c2o structure, the intradimer space is relatively open. Indeed, extension of the PRAD helix, by simple replication, showed that it could pass through it with very few clashes. Comparison of the 1c2o structure with the model showed that only minimal changes occurred upon fitting [WAT]4PRAD to the 1c2o tetramer (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 12.

Model of the physiological ColQ-linked AChET tetramer. (A) View looking down an approximate two-fold symmetry axis relating one dimer (cyan/blue) to the other (red/magenta). Two active-site gorge entrances (yellow patches) are apparent in this view, one for each dimer, the others being on the other side of the tetramer plane. The attached WAT domains (colored gray) are transparent surfaces, revealing the PRAD (green surface) threading its way between them. (B) View in which the entire structure has been rotated such that the ColQ polypeptide is vertical. The WAT polypeptides are displayed as ribbons, and the PRAD as a yellow surface model. Subunit color coding is the same as used for WAT chains (see Figure 6).

Our idealization procedure yielded a model with two similar but nonequivalent dimers, especially at their C-termini (Figure 12). In one dimer (cyan-blue), the monomers are directly linked via a disulfide bond; in the other each is disulfide-linked to the PRAD. Furthermore, the limited contact between the two dimers (Figure 12A and Supplementary Figure 4B) supports a model in which their interaction with the PRAD predominates over their interaction with each other. This is in line with the observation that if two proteins, for example, AChE and alkaline phosphatase, both with WAT sequences at their C-termini, are mixed with PRAD at various ratios, tetramers containing three subunits of one protein and one of the other are underrepresented (Simon et al, 1998).

A point mutation in the PRAD prevents assembly of the asymmetric form of AChE

A variety of mutations in the ColQ gene result in the neuromuscular disease congenital endplate AChE deficiency, due to defective assembly or anchoring of the asymmetric forms of AChE (Engel et al, 2003). The P59Q mutation in human ColQ (Ohno et al, 1998) corresponds to P7 in our synthetic PRAD (Supplementary Figure 5A). The ring of P59 makes specific interactions with W17 in WAT chain A and M21 in WAT chain D. In proximity to P59, there is an edge-on π–π interaction of ‘core' residue F14 in chain A with Y20 in chain D. Modeling of a Gln residue replacing P59 (Supplementary Figure 5B) shows not only that the interactions of PRAD with W17 and M21 are lost, but also that the Gln residue clashes with Y20 of chain D, thus disrupting its π–π interaction with F14 and, consequently, destabilizing interaction between WAT chains A and D. In our [AChET]4ColQ model, which consists of a dimer of dimers, these two chains belong to different dimers within the tetramer. It is thus likely that the P59Q mutation not only affects attachment of each AChET dimer to ColQ, but also weakens the dimer–dimer interaction. This provides a plausible structural explanation for the failure to detect asymmetric forms of AChE in COS cells cotransfected with wt AChET and the ColQ P59Q mutant (Engel et al, 2003).

Concluding remarks

The structure of the [WAT]4PRAD complex reveals a novel structural fold, the first superhelical structure in which the coiled coils are wound around a central polypeptide. This structure plays a crucial biological role in both the central and peripheral nervous systems: it provides the attachment module for the synaptic enzyme, AChE, by tightly associating four catalytic subunits possessing the C-terminal t peptide with the ColQ or PRiMA proteins which anchor them at cholinergic synapse.

Complexation with PRAD, resulting in tetramerization, greatly prolongs the circulatory lifetime of recombinant bovine AChE (Kronman et al, 2000), and coexpression of human BChE with a PRAD-containing ColQ fragment produces tetramers with an increased residence time (Duysen et al, 2002). Since heterologous proteins can replace the AChET subunits in PRAD-linked tetramers (Simon et al, 1998), the [WAT]4PRAD module may have broad application in stabilizing proteins in biotechnological and clinical contexts.

ColQ is expressed at substantial levels in various non-neuronal tissues (Krejci et al, 1997). Its role as an anchoring protein in these tissues, and the proteins with which it may be associated, remain to be established, as does participation of the novel superhelical motif in other macromolecular assemblies.

Materials and methods

Peptide synthesis

Synthesis of PRAD and WAT (Figure 2) utilized the Merrifield solid-phase method on an Applied Biosystems (ABI) 431A automated peptide synthesizer with small-scale 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry (Fields and Noble, 1990). Protected amino acids were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), except for selenomethionine, obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO), and protected by reaction with Fmoc-Osu (Sigler et al, 1983). Crude peptides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC on a Vydac C18 column (5 μm, 250 × 10 mm2), using appropriate acetonitrile gradients containing 0.1% TFA. Molecular weights were verified by ion electrospray mass spectrometry.

Immobilization of the PRAD peptide on Sepharose beads

CNBr-activated Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) were swollen in NaHCO3 buffer (2 ml in 20 ml of 1 M NaCl/1 mM NaHCO3, pH 8.3), stirring at 4°C for 1 h, and centrifuged for 3 min at 1500 r.p.m. The beads (4.5 ml) were divided into 1 ml aliquots, which were incubated overnight at 4°C in a rotatory agitator with 1 ml buffer, with or without 100 mM PRAD. They were then pelleted at 1500 r.p.m. and, after removal of supernatant, washed three times with agitation for 20 min in blocking buffer (Tris–HCl, pH 8.0). Samples of beads (80 μl) were incubated overnight, at 4°C with agitation, with 300 μl of Tris buffer containing 1–500 μM WAT. The beads were then rinsed three times in TBS (Tris-buffered saline, viz. 140 mM NaCl/5 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4) containing 0.01% Tween, after which the liquid was removed under vacuum. The retained WAT was eluted in 40 μl Laemmli buffer (Cussac et al, 1999) for 5 min at 95°C. After centrifugation at 13 000 r.p.m. for 3 min, the supernatant was analyzed by SDS–PAGE in a 20% polyacrylamide gel, which was stained with Coomassie blue.

Crystallization and structure determination

WAT and PRAD, at a stoichiometric ratio of 4:1, were dissolved in water (final polypeptide concentration 26.7 mg/ml). Crystals (0.2 × 0.05 × 0.05 mm3) grew within 10 days at room temperature, using the hanging drop method with a reservoir containing 10% isopropanol/10% polyethylene glycol 4000/0.05 M trisodium citrate, pH 5.6. Four complete X-ray data sets were collected at 100 K, one collected ‘in house' at the Weizmann Institute, using a rotating anode, and three MAD data sets at peak, inflection point and remote wavelengths for Se at the NSLS beamline X4A at Brookhaven National Laboratory. For data collection and processing, see Table II. Data were processed using DENZO (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). The eight Se atoms were located via direct methods in SnB (Weeks and Miller, 1999). The structure was solved using SOLVE/RESOLVE (Terwilliger et al, 1987) at 2.8 Å resolution, using the Se sites, and clear α-helical density for the WAT chains was fitted using O (Jones, 1978). Refinement was done via a combination of REFMAC (Murshudov et al, 1997), ARP/wARP (Lamzin and Wilson, 1993) and completed with CNS (Brünger et al, 1998), starting at 3.0 Å resolution, with strict noncrystallographic two-fold symmetry, and iteratively building more residues and refining with increasing resolution, until noncrystallographic symmetry was abandoned, and the data were refined to 2.35 Å resolution. Table II shows final refinement parameters.

Table 2.

Crystallographic statistics

| R-axis | Se peak | Se inflection | Se remote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection and phasing | ||||

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a=53.73 | a=54.10 | a=54.16 | a=54.13 |

| β angle (deg) | b=58.79 | b=59.18 | b=59.16 | b=59.19 |

| c=58.8 | c=59.80 | c=60.02 | c=59.90 | |

| β=111.38 | β=112.49 | β=112.50 | β=112.49 | |

| Matthews coefficient, Vm (Å3/Da) | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5415 | 0.97895 | 0.97927 | 0.96672 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 28.85–2.35 | 50–2.3 | 50–2.5 | 50–2.5 |

| Unique reflections | 12 889 | 14 862 | 12 178 | 11 703 |

| Completeness (%) | 89.4 (58.5)a | 94.6 (98.9) | 94.2 (90.1) | 94.6 (99.9) |

| Wilson plot β-factor | 55.2 | 55.8 | 72.5 | 62.4 |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 11.1 (1.5)a | 21.0 (2.4) | 18.3 (1.7) | 23.5 (3.2) |

| Rsym(I) (%) | 5.4 (34.9)a | 10.5 (25.3) | 7.0 (43.5) | 8.4 (31.0) |

| Phasing power (iso/ano)b | — | 0.7/1.9 | 0.1/1.2 | 0.5/1.3 |

| Mean FOMc up to 2.3 Å (solve/resolve) | 0.47/0.48 | |||

| Refinement and model statistics | ||||

| No. of protein atoms | 2615 | |||

| No. of solvent atoms | 38 | |||

| Rworkd, Rfreee (F>0σ) | 24.7%, 25.9% | |||

| Mean B-factor (Å2) | 60.0 | |||

| R.m.s. from idealityf | ||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.009 | |||

| Bond angle (deg) | 1.2 | |||

| Ramachandran plotg | ||||

| Favored | 91.7% | |||

| Allowed | 8.3% | |||

| Generously allowed | 0.0% | |||

| Disallowed | 0.0% | |||

| aStatistics for outer shell 2.38–2.35 Å (data in parentheses). | ||||

| bPhasing power=〈[∣FH(calc)∣/E]〉, where FH is the calculated heavy atom structure factor and E is the integrated lack of closure, that is, E=FH+FP−FPH. | ||||

| cMean FOM=mean cosine(phase error). | ||||

| dRwork=∑∣∣Fo∣–∣Fc∣∣/∑∣Fo∣, where Fo and Fc denote the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively. | ||||

| eRfree is as for Rwork, but calculated for only 5% of randomly chosen reflections omitted from the refinement. | ||||

| fCalculated in CNS (Brünger et al, 1998). | ||||

| gCalculated with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al, 1993). | ||||

Modeling of the AChET tetramer using CORELS

The 3D structure of [WAT]4PRAD was fitted to the C-terminus of one of the EeAChE tetramer structures [PDB ID code 1c2o] (Bourne et al, 1999), using CORELS (Sussman et al, 1977).

Production and analysis of [AChET]4QN complexes

Complexes were formed between rat AChET and the QN fragment of Torpedo ColQ, metabolically labeled and analyzed as described (Bon et al, 2003). Mutagenesis of QN introduced two cysteines at positions 68–69 (N68C/K69C), either together with the original cysteines (C70–C71), or after replacing them by serines. At 2 days after cotransfection (Duval et al, 1992) of AChET subunits with QN, COS cells were preincubated for 45 min in DMEM lacking both cysteine and methionine, and labeled with 35S-methionine–cysteine (Amersham) for 30 min. The cells were then rinsed with PBS, and chased overnight in a medium containing Nu-serum.

AChE secreted overnight was immunoprecipitated with 1/500 A63 antiserum raised against rat AChE (Marsh et al, 1984), immunoadsorbed on protein G immobilized on Sepharose 4B Fast Flow beads (Sigma), and analyzed by SDS–PAGE under nonreducing conditions; bands were revealed with a Fuji Image Analyzer.

PDB codes

The PDB IDcode for [WAT]4PRAD is 1VZJ.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Figure 4

Supplementary Figure 5

Acknowledgments

We thank the Rapid Data Course staff of the NSLS at BNL for help in data collection and analysis, Sarel Fleishman (Tel Aviv University) for advice concerning superhelical parameters, and Kurt Giles (University of California, San Francisco) for valuable discussions. This study was supported by EC Vth Framework Contracts QLK3-2000-00650 and QLG2-CT-2002-00988 (SPINE), the Kimmelman Center for Biomolecular Structure and Assembly, the Benoziyo Center for Neurosciences, le Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, l'Association Française contre les Myopathies and le Direction des Forces et de la Prospective. JLS is Morton and Gladys Pickman Professor of Structural Biology.

Dedicated to the memory of Francis Crick.

References

- Adzhubei AA, Sternberg MJ (1993) Left-handed polyproline II helices commonly occur in globular proteins. J Mol Biol 229: 472–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglister L, Roth E, Silman I (1980) Quaternary structure of electric eel acetylcholinesterase. In Synaptic Constituents in Health and Disease, Brzin M, Sket D, Bachelard H (eds), pp 533–540. New York: Pergamon [Google Scholar]

- Anglister L, Silman I (1978) Molecular structure of elongated forms of electric eel acetylcholinesterase. J Mol Biol 125: 293–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal M, Kumar S, Velavan R (2000) HELANAL: a program to characterize helix geometry in proteins. J Biomol Struct Dyn 17: 811–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbeoc'h S, Falasca C, Leroy J, Ayon A, Massoulié J, Bon S (2004) Elements of the C-terminal t peptide of acetylcholinesterase that determine amphiphilicity, homomeric and heteromeric associations, secretion and degradation. Eur J Biochem 271: 1476–1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbeoc'h S, Massoulié J, Bon S (2003) The C-terminal T peptide of acetylcholinesterase enhances degradation of unassembled active subunits through the ERAD pathway. EMBO J 22: 3536–3545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blong RM, Bedows E, Lockridge O (1997) Tetramerization domain of human butyrylcholinesterase is at the C-terminus. Biochem J 327: 747–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon S, Ayon A, Leroy J, Massoulié J (2003) Trimerization domain of the collagen tail of acetylcholinesterase. Neurochem Res 28: 523–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon S, Coussen F, Massoulié J (1997) Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. II. The polyproline attachment domain of the collagen tail. J Biol Chem 272: 3016–3021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon S, Dufourcq J, Leroy J, Cornut I, Massoulié J (2004) The C-terminal t peptide of acetylcholinesterase forms an alpha helix that supports homomeric and heteromeric interactions. Eur J Biochem 271: 33–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon S, Massoulié J (1976) Molecular forms of Electrophorus acetylcholinesterase the catalytic subunits: fragmentation, intra- and inter-subunit disulfide bonds. FEBS Lett 71: 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon S, Massoulié J (1997) Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. I. Oligomeric associations of T subunits with and without the amino-terminal domain of the collagen tail. J Biol Chem 272: 3007–3015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne Y, Grassi J, Bougis PE, Marchot P (1999) Conformational flexibility of the acetylcholinesterase tetramer suggested by X-ray crystallography. J Biol Chem 274: 30370–30376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne Y, Taylor P, Marchot P (1995) Acetylcholinesterase inhibition by fasciculin: crystal structure of the complex. Cell 83: 503–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 54: 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard P, Stetefeld J, Strelkov SV (2001) Coiled coils: a highly versatile protein folding motif. Trends Cell Biol 11: 82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PM, McGavin S (1955) Structure of poly-L-proline. Nature 176: 501–503 [Google Scholar]

- Crick FH (1952) Is alpha-keratin a coiled coil? Nature 170: 882–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick FHC (1953) The packing of α-helices: simple coiled coils. Acta Crystallogr 6: 689–697 [Google Scholar]

- Cussac D, Vidal M, Leprince C, Liu WQ, Cornille F, Tiraboschi G, Roques BP, Garbay C (1999) A Sos-derived peptidimer blocks the Ras signaling pathway by binding both Grb2 SH3 domains and displays antiproliferative activity. FASEB J 13: 31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y, Herzberg M, Silman I (1973) Molecular structures of acetylcholinesterase from electric organ tissue of the electric eel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70: 2473–2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval N, Massoulié J, Bon S (1992) H and T subunits of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo, expressed in COS cells, generate all types of globular forms. J Cell Biol 118: 641–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duysen EG, Bartels CF, Lockridge O (2002) Wild-type and A328W mutant human butyrylcholinesterase tetramers expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells have a 16-h half-life in the circulation and protect mice from cocaine toxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 302: 751–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AG, Ohno K, Shen XM, Sine SM (2003) Congenital myasthenic syndromes: multiple molecular targets at the neuromuscular junction. Ann NY Acad Sci 998: 138–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields GB, Noble RL (1990) Solid phase peptide synthesis utilizing 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl amino acids. Int J Pept Protein Res 35: 161–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman SJ, Ben-Tal N (2002) A novel scoring function for predicting the conformations of tightly packed pairs of transmembrane alpha-helices. J Mol Biol 321: 363–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennari K, Brunner J, Brodbeck U (1987) Tetrameric detergent-soluble acetylcholinesterase from human caudate nucleus: subunit composition and number of active sites. J Neurochem 49: 12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles K, Ben-Yohanan R, Velan B, Shafferman A, Sussman JL, Silman I (1998) Assembly of acetylcholinesterase subunits in vitro. In Structure and Function of Cholinesterases and Related Proteins, Doctor BP, Quinn DM, Rotundo RL, Taylor P (eds), pp 442–443. New York: Plenum [Google Scholar]

- Goudreau N, Cornille F, Duchesne M, Parker F, Tocque B, Garbay C, Roques BP (1994) NMR structure of the N-terminal SH3 domain of GRB2 and its complex with a proline-rich peptide from Sos. Nat Struct Biol 1: 898–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber M, Lupas AN (2003) Historical review: another 50th anniversary—new periodicities in coiled coils. TIBS 28: 679–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson WA (1991) Determination of macromolecular structures from anomalous diffraction of synchrotron radiation. Science 254: 51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg O, Sussman JL (1983) Protein model building by the use of a constrained–restrained least-squares procedure. J Appl Crystallogr 16: 144–150 [Google Scholar]

- Inestrosa NC, Roberts WL, Marshall TL, Rosenberry TL (1987) Acetylcholinesterase from bovine caudate nucleus is attached to membranes by a novel subunit distinct from those of acetylcholinesterases in other tissues. J Biol Chem 262: 4441–4444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardetzky TS, Brown JH, Gorga JC, Stern LJ, Urban RG, Strominger JL, Wiley DC (1996) Crystallographic analysis of endogenous peptides associated with HLA-DR1 suggests a common, polyproline II-like conformation for bound peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 734–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedrzejczyk J, Silman I, Lyles JM, Barnard EA (1981) Molecular forms of the cholinesterases inside and outside muscle endplates. Biosci Rep 1: 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA (1978) A graphics model building and refinement system for macromolecules. J Appl Crystallogr 11: 268–272 [Google Scholar]

- Kay BK, Williamson MP, Sudol M (2000) The importance of being proline: the interaction of proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins with their cognate domains. FASEB J 14: 231–241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci E, Coussen F, Duval N, Chatel JM, Legay C, Puype M, Vandekerckhove J, Cartaud J, Bon S, Massoulié J (1991) Primary structure of a collagenic tail peptide of Torpedo acetylcholinesterase: co-expression with catalytic subunit induces the production of collagen-tailed forms in transfected cells. EMBO J 10: 1285–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci E, Thomine S, Boschetti N, Legay C, Sketelj J, Massoulié J (1997) The mammalian gene of acetylcholinesterase-associated collagen. J Biol Chem 272: 22840–22847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronman C, Chitlaru T, Elhanany E, Velan B, Shafferman A (2000) Hierarchy of post-translational modifications involved in the circulatory longevity of glycoproteins. Demonstration of concerted contributions of glycan sialylation and subunit assembly to the pharmacokinetic behavior of bovine acetylcholinesterase. J Biol Chem 275: 29488–29502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryger G, Harel M, Giles K, Toker L, Velan B, Lazar A, Kronman C, Barak D, Ariel N, Shafferman A, Silman I, Sussman JL (2000) Structures of recombinant native and E202Q mutant human acetylcholinesterase complexed with the snake-venom toxin fasciculin-II. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 56: 1385–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamzin VS, Wilson KS (1993) Automated refinement of protein models. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 49: 129–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legay C, Huchet M, Massoulié J, Changeux JP (1995) Developmental regulation of acetylcholinesterase transcripts in the mouse diaphragm: alternative splicing and focalization. Eur J Neurosci 7: 1803–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WA, Richards FM (1994) Critical residues in an SH3 domain from Sem-5 suggest a mechanism for proline-rich peptide recognition. Nat Struct Biol 1: 221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WA, Richards FM, Fox RO (1994) Structural determinants of peptide-binding orientation and of sequence specificity in SH3 domains. Nature 372: 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D, Grassi J, Vigny M, Massoulié J (1984) An immunological study of rat acetylcholinesterase: comparison with acetylcholinesterases from other vertebrates. J Neurochem 43: 204–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoulié J (2002) The origin of the molecular diversity and functional anchoring of cholinesterases. Neurosignals 11: 130–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoulié J, Pezzementi L, Bon S, Krejci E, Vallette F-M (1993) Molecular and cellular biology of cholinesterases. Prog Neurobiol 14: 31–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann WF, Rosenberry TL (1977) Identification of discrete disulfide-linked oligomers which distinguish 18 S from 14 S acetylcholinesterase. Arch Biochem Biophys 183: 347–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel N, Leroy J, Ayon A, Massoulié J, Bon S (2001) Acetylcholinesterase H and T dimers are associated through the same contact. Mutations at this interface interfere with the C-terminal T peptide, inducing degradation rather than secretion. J Biol Chem 276: 37379–37389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G, Vagin A, Dodson E (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53: 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A, Saraste M, Wilmanns M (1994) High-resolution crystal structures of tyrosine kinase SH3 domains complexed with proline-rich peptides. Nat Struct Biol 1: 546–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Brengman J, Tsujino A, Engel AG (1998) Human endplate acetylcholinesterase deficiency caused by mutations in the collagen-like tail subunit (ColQ) of the asymmetric enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9654–9659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276: 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier AL, Massoulié J, Krejci E (2002) PRiMA: the membrane anchor of acetylcholinesterase in the brain. Neuron 33: 275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran GN, Kartha A (1954) Structure of collagen. Nature 174: 269–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raves M, Giles K, Schrag JD, Schmid MF, Phillips GN, Chiu W, Howard AJ, Silman I, Sussman JL (1998) Quaternary structure of tetrameric acetylcholinesterase. In Structure and Function of Cholinesterases and Related Proteins, Doctor BP, Quinn DM, Rotundo RL, Taylor P (eds), pp 351–356. New York: Plenum [Google Scholar]

- Reddy V, Swanson SM, Segelke B, Kantardjieff KA, Sacchettini JC, Rupp B (2003) Effective electron-density map improvement and structure validation on a Linux multi-CPU web cluster: The TB Structural Genomics Consortium Bias Removal Web Service. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 59: 2200–2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich A, Crick FH (1955) The structure of collagen. Nature 176: 915–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger F, Bon S, Massoulié J (1973) Observation par microscopie électronique des formes allongées et globulaires de l'acétylcholinestérase de gymnote (Electrophorus electricus). Eur J Biochem 34: 539–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Yandell MD, Wortman JR, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson CR, Hariharan IK, Fortini ME, Li PW, Apweiler R, Fleischmann W, Cherry JM, Henikoff S, Skupski MP, Misra S, Ashburner M, Birney E, Boguski MS, Brody T, Brokstein P, Celniker SE, Chervitz SA, Coates D, Cravchik A, Gabrielian A, Galle RF, Gelbart WM, George RA, Goldstein LS, Gong F, Guan P, Harris NL, Hay BA, Hoskins RA, Li J, Li Z, Hynes RO, Jones SJ, Kuehl PM, Lemaitre B, Littleton JT, Morrison DK, Mungall C, O'Farrell PH, Pickeral OK, Shue C, Vosshall LB, Zhang J, Zhao Q, Zheng XH, Lewis S (2000) Comparative genomics of the eukaryotes. Science 287: 2204–2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigler GF, Fuller WD, Chaturvedi NC, Goodman M, Verlander M (1983) Formation of oligopeptides during the synthesis of 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl amino acid derivatives. Biopolymers 22: 2157–2162 [Google Scholar]

- Silman I, di Giamberardino L, Lyles LJM, Couraud JY, Barnard EA (1979) Parallel regulation of acetylcholinesterase and pseudocholinesterase in normal, denervated and dystrophic chicken skeletal muscle. Nature 280: 160–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silman I, Futerman AH (1987) Modes of attachment of acetylcholinesterase to the surface membrane. Eur J Biochem 170: 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon S, Krejci E, Massoulié J (1998) A four-to-one association between peptide motifs: four C-terminal domains from cholinesterase assemble with one proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD) in the secretory pathway. EMBO J 17: 6178–6187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strelkov SV, Burkhard P (2002) Analysis of alpha-helical coiled coils with the program TWISTER reveals a structural mechanism for stutter compensation. J Struct Biol 137: 54–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman JL, Harel M, Frolow F, Oefner C, Goldman A, Toker L, Silman I (1991) Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: a prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science 253: 872–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman JL, Holbrook SR, Church GM, Kim S-H (1977) A structure-factor least squares refinement procedure for macromolecular structures using constrained and restrained parameters. Acta Crystallogr A 33: 800–804 [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC, Kim S-H, Eisenberg D (1987) Generalized method of determining heavy-atom positions using the difference Patterson function. Acta Crystallogr A 43: 1–5 [Google Scholar]

- Vigny M, Gisiger V, Massoulié J (1978) ‘Nonspecific' cholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase in rat tissues: molecular forms, structural and catalytic properties, and significance of the two enzyme systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 75: 2588–2592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks CM, Miller R (1999) The design and implementation of SnB v2.0. J Appl Crystallogr 32: 120–124 [Google Scholar]

- Zarrinpar A, Lim WA (2000) Converging on proline: the mechanism of WW domain peptide recognition. Nat Struct Biol 7: 611–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Figure 4

Supplementary Figure 5