Abstract

Introduction

The vast majority of men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer die of other causes, highlighting the importance of determining which patient has a risk of death from prostate cancer. Precision management of prostate cancer patients includes distinguishing which men have potentially lethal disease and employing strategies for determining which treatment modality appropriately balances the desire to achieve a durable response while preventing unnecessary overtreatment.

Areas covered

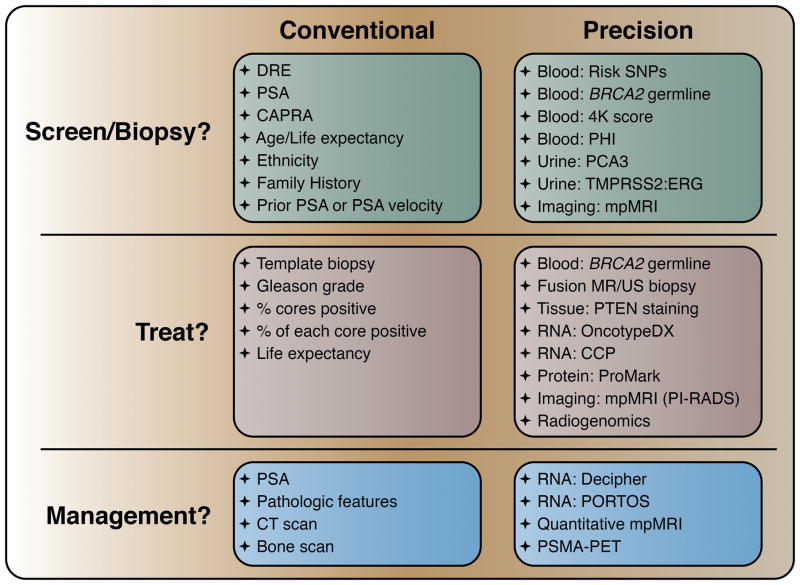

In this review, we highlight precision approaches to risk assessment and a context for the precision-guided application of definitive therapy. We focus on three dilemmas relevant to the diagnosis of localized prostate cancer: screening, the decision to treat, and postoperative management.

Expert commentary

In the last five years, numerous precision tools have emerged with potential benefit to the patient. However, to achieve optimal outcome, the decision to employ one or more of these tests must be considered in the context of prevailing conventional factors. Moreover, performance and interpretation of a molecular or imaging precision test remains practitioner-dependent. The next five years will witness increased marriage of molecular and imaging biomarkers for improved multi-modal diagnosis and discrimination of disease that is aggressive versus truly indolent.

Keywords: prostate cancer, mpMRI, risk stratification, clinical management, high-risk, molecular biomarkers, imaging biomarkers

1. INTRODUCTION

When prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing was introduced in the late 1980s, the number of patients diagnosed with prostate cancer increased dramatically [1]. It became clear that while PSA screening was associated with decreasing prostate cancer-specific mortality, the vast majority of men diagnosed with prostate cancer died of other causes. Despite this, there remained a large number of patients dying of prostate cancer. Thus a major question arose in the field: How does one prevent symptomatic and lethal prostate cancer while minimizing toxicity? This review addresses this question by highlighting precision approaches to risk assessment and a context for the precision-guided application of definitive therapy (see Figure).

Figure.

It is estimated that there will be 180,000 new cases of prostate cancer in the United States in 2016, and 26,000 deaths [2]. Most of those diagnosed with prostate cancer have intermediate risk disease, followed by low risk and high risk disease [3]. Suggesting a benefit from PSA screening, the rate of diagnosis for metastatic disease declined rapidly in the 1990s, and both the incidence and mortality of prostate cancer are decreasing in most of the world [4, 5]. Since so few patients are diagnosed with metastatic disease in the current era, most deaths from prostate cancer are rather due to harboring high risk localized disease at the time of diagnosis, followed by a subsequent relapse, suggesting that management of these patients could be improved. Meanwhile, the vast majority of men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer die of other causes, highlighting the importance of determining whether the patient needs treatment at all.

Two large randomized trials were conducted to evaluate PSA screening, with modest if any benefit seen, at least initially [6, 7, 8, 9]. Because of this, PSA screening has become more controversial, and in 2012 the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against PSA screening [10]. This was largely based on the large number of patients undergoing definitive treatment for disease that would not otherwise affect their life expectancy, and subsequently suffering the adverse effects of overtreatment. It appears that metastatic disease incidence has increased since the trial results were first available and USPSTF recommendations discussed [3], suggesting a blanket recommendation against PSA screening is not the best answer. Instead, a precision approach to screening is needed to identify which patients are at greatest risk of being diagnosed with aggressive prostate cancer.

Since the primary criticism of unselected PSA screening is the overtreatment of non-lethal disease, one way to improve the performance of PSA screening is through active surveillance for indolent disease [11]. Greater use of an effective active surveillance program reduces the number treated without reducing the number of deaths prevented by screening. More precise risk assessment would lead to higher confidence, and increased participation, in active surveillance, through better selection of patients appropriate for active surveillance versus immediate treatment. Current risk stratification strategies rely on the cancer grade (Gleason score), clinical stage, PSA level, and age, following one of multiple nomograms for weighing these factors, depending upon institution and practitioner. The “Epstein criteria” are amongst the most stringent and well-accepted for enrolling patients into active surveillance, requiring a PSA density of <0.15 ng/ml2, clinical stage T1c, and 2 or fewer biopsy cores of Gleason score 6 involving less than 50% of any core [12]. However, prostate cancer practitioners are seeking to further decrease overtreatment and its related comorbidities by expanding the criteria for active surveillance and investigating its safety and efficacy [12, 13]. The “D’Amico” criteria are broader, in which active surveillance is recommended for those men who have PSA <10 ng/ml, clinical stage T2a or lower, and Gleason score of 6 [14]. Finally, the CAPRA sum score considers age at diagnosis, percent of cores positive for cancer and clinical T-stage, with higher weights given to PSA at diagnosis and Gleason score, such that a low risk score (0–2) patient is the best candidate for active surveillance [15].

Epidemiologic studies have identified family history of lethal prostate cancer as another risk factor [16]. In addition, there are now multiple molecular tests to assist in risk assessment, testing either the tissue or the patient. An equally important assessment tool, however, is imaging, to better understand the location and extent of disease. The implementation of new technology is limited to centers of excellence but would be improved with more widely spread adoption of this technology. A major opportunity for advancement is combining imaging and molecular approaches to assess the potential for metastatic or lethal disease.

Once the decision is made to treat localized prostate cancer, one must decide the management approach. For management by radical prostatectomy, this means planning the surgery, which may vary depending on accurate staging. For management by radiation therapy, androgen deprivation therapy can sensitize prostate cancer to radiation therapy, and concurrent hormone therapy has a survival benefit for those with high risk prostate cancer [17, 18]. While radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, and brachytherapy cure most patients with localized disease, 20–40% of those undergoing radical prostatectomy [19, 20] and 30–50% of patients receiving radiation therapy [21] experience biochemical recurrence within 10 years. For those treated with radical prostatectomy, salvage radiation therapy is an additional potentially curative modality, but it comes with significant toxicity. At the time of biochemical recurrence, the prostate cancer-specific survival is greater than 16 years, suggesting many of these patients continue to have indolent disease and will not benefit from additional therapy [22]. In contrast, other patients already have metastatic disease and would have progression uninterrupted by salvage radiation. Thus more precise assessment of benefit from salvage radiation is needed.

2. SCREEN VS. NOT SCREEN: PRECISION BIOMARKERS FOR RISK ASSESSMENT

The 2012 recommendation of the USPSTF against routine PSA screening for prostate cancer was based largely on the concern that PSA testing led to a greater incidence of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of otherwise indolent prostate cancer without any significant reduction in deaths due to prostate cancer [10]. While the validity and implementation of this recommendation is controversial, concerns that elevated PSA for reasons other than lethal prostate cancer leads to the discovery of indolent disease lends weight to the argument that precision risk assessments may better identify those patients in whom an elevated PSA is likely to indicate clinically significant disease [23]. A precision approach for risk assessment must consider factors such as age, race and family history [24], but may also employ molecular diagnostic tools that couple PSA with assays that more precisely detect prostate cancer, and whether that cancer would be likely to lead to lethal disease if untreated. Upon determination of sufficient risk, a prostate biopsy would be warranted.

2.1. Germline tests for heritable risk

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) over the last decade have identified over 100 germline single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that show significant association with relevant prostate cancer diagnosis measures, including elevated PSA, family history, and probability of future prostate cancer development [25]. In considering the predictive value of risk SNPs for evaluating men who might benefit from PSA testing, the International Consortium for Prostate Cancer Genetics (ICPCG) evaluated over 12,500 samples and established a significant relationship for 8 risk SNPs and prostate cancer [26]. SNPs identified by ICPCG confirmed that irrespective of a SNP’s (potential) functional effect, the overlap between these SNPs and those from other population-based case-control studies draw a clear link between family history and the incidence of prostate cancer. Importantly, with the exception of those SNPs that show significant disequilibrium in men of African American ancestry, risk SNPs were unable to distinguish between aggressive and indolent prostate cancer [26].

In contrast, for identification of germline features that accumulate in those men who do progress to advanced disease, the East Coast Prostate Cancer Foundation-Stand Up to Cancer (PCF-SU2C) study examining biopsies from metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients revealed significant enrichment for mutations to DNA damage repair (DDR) genes, including BRCA2, ATM, and BRCA1 [27]. While most of these alterations occurred somatically in the metastatic CRPC biopsies (and were not as frequently observed in primary prostate cancer [28]), 5.3% of the cohort harbored a germline BRCA2 mutation (frameshift or nonsense) which cooperated with a somatic biallelic event to deplete all BRCA2 function [27]. Similarly, two cases with germline ATM mutations and one case with a germline BRCA1 mutation suggest that carriers of these pathogenic alleles might be at greater risk for developing prostate cancer with potential to progress to metastatic CPRC [27]. In a follow-up study, the multi-institutional PCF-SU2C consortium assessed the rate of deleterious germline mutations in a panel of 20 DDR genes amongst 682 men with metastatic prostate cancer without regard to family history [29]. Retrospectively assessing family history, however, the finding that most of the 11.8% of men in this study with advanced prostate cancer who harbored germline aberrations to DDR genes also had family histories of breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancers [29] strengthens the argument that there is a genuine hereditable risk for prostate cancer. The IMPACT study [30] found that amongst 2481 men with known BRCA2 status, prostate biopsies performed on the basis of rising PSA were twice as likely to detect intermediate or high risk disease in BRCA2 carriers versus those with wild-type alleles. Therefore, men who carry such alleles would be likely to benefit from PSA screening measures, as they are at greater likelihood to identify high risk localized prostate cancer for which definitive treatment would carry a survival benefit.

2.2. Blood tests for prostate cancer: alternatives to PSA

The increase in new prostate cancer diagnoses since the introduction of PSA screening in the late 1980s demonstrates an obvious relationship between the presence of PSA in the bloodstream and the likelihood that it is being produced by prostate cancer cells [1]. However, measurements of serum PSA often cannot distinguish between aggressive, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma versus potentially-indolent, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma [31]. Coupling PSA with additional blood-based markers for androgen receptor (AR) activity has the potential to increase specificity for prostate cancer for proceeding to a prostate biopsy.

Decision making based on measurements of the quantity of free PSA (i.e. PSA not complexed to serum) in the blood has been shown to decrease the false positive rate for misclassifying benign disease [32]. The Prostate Health Index (PHI) score considers total and free PSA, as well as the [−2]proPSA isoform which is differentially expressed in the prostate peripheral zone and increases specificity for peripheral zone disease, the most common type of prostate cancer and the form most frequently detected by digital rectal examination [33]. Indeed, the National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) guidelines for prostate cancer were revised in 2014 to include PHI score as a metric for earlier and precise detection of prostate cancer in men with PSA between 2 and 10 ng/ml. PHI is approximately 3 times more specific than PSA alone to detect prostate cancer and decrease the likelihood of an unnecessary biopsy [34].

Further decreasing the likelihood that a high PSA could lead to an unnecessary biopsy, the 4-Kallikrein (4K) Score considers not only total and free PSA, but also intact (uncleaved) PSA and the protein product of KLK2, which is just distal to the PSA/KLK3 locus and is similarly up-regulated by AR activity [35]. The 4K score directly reports a risk between 1% and 95% for Gleason score ≥ 7 cancer being present on biopsy [35]. Unlike PHI, the increased reliance on AR activity in the 4K score is therefore responsible, at least in part, for its ability to better discriminate lethal cancer [36], allowing for more precise determination of risk in calculating the potential benefits of undergoing a prostate biopsy.

2.3. Urine tests for prostate cancer

Over the last twenty years, molecular analyses comparing malignant and nonmalignant prostate tissue have identified several genes whose up-regulation are cancer specific. Considering that the urethra passes through the prostate gland, urine has the potential to be more representative of localized disease than blood, especially when measuring analytes that would likely be in lower abundance systemically. Precise design of assays targeting up-regulated mRNA species offers superior sensitivity in urine versus blood, and this sensitivity is further enriched when collecting prostate cells from urine immediately following a prostate massage.

The noncoding RNA PCA3 (DD3) was initially identified as a differentially expressed transcript in prostate cancer tissue and is sufficiently overexpressed in prostate cancer such that it can be readily detected and enumerated in post-DRE urine [37]. In conjunction with measuring the mRNA levels of PSA, the FDA-approved test for PCA3 imputes a score based on the ratio of PCA3 to PSA transcript abundance such that higher scores are more likely to be associated with the finding of prostate cancer on biopsy, especially when considered together with serum PSA levels [38]. More importantly, PCA3 scores are associated with higher Gleason grades more so than prostate volume, suggesting that a biopsy following an elevated PCA3 score will more likely be informative to identify aggressive prostate cancer [39].

Further transcriptomic studies of prostate cancer identified the up-regulation of a fusion between the AR-regulated gene TMPRSS2 and the transcription factor ERG, resulting in a recurrent mRNA species distinctly expressed by approximately 50% of prostate neoplasms and not benign tissue [40]. While the resulting TMPRSS2:ERG fusion protein is not secreted, as with PCA3 the coding mRNA for TMPRSS2-ERG is abundant and detectable in urine [40]. The limitations of a clinical-grade urine biomarker assay solely measuring TMPRSS2-ERG include the fact the false-negative rate would be quite high in failing to detect fusion-negative tumors, and that TMPRSS2-ERG expressed by prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia could result in a false positive [40]. However, adding to urine TMPRSS2-ERG, the urine PCA3 biomarker in conjunction with serum PSA to generate a combined multiplex assay outperformed all three biomarkers alone in predicting cancer upon biopsy with an AUC of 0.751 [41]. The resulting “Mi-Prostate Score (MiPS)” regression model combining TMPRSS2-ERG, PCA3 and PSA shows tremendous promise as an alternative for predicting prostate cancer or high grade disease upon biopsy and providing a metric for precision risk calculation [41].

3. TREAT VS. NOT TREAT: PRECISION BIOMARKERS FOR PROGNOSTICATION

If there is sufficient evidence to warrant biopsy and cancer is identified, the decision of whether to undergo immediate definitive treatment or to pursue active surveillance depends on the assessment of risk of developing metastatic or lethal prostate cancer. To date, there is no better single predictive measurement than Gleason grade of the biopsy sample for reducing prostate cancer-specific mortality by radical prostatectomy [42]. Nonetheless, templated or systematic biopsies of the prostate have risk of significant sampling errors intrinsic to the probability of finding disease. In addition, and despite the prognostic power of Gleason grade, morphologically identical glands (such as Gleason pattern 3) may represent a small component of a larger, more aggressive (yet unsampled) tumor system in some individuals, which would warrant further biopsies prior to definitive treatment, while in other men it may represent an indolent cancer for which surveillance is a better option. In either case, precision tests including imaging and molecular diagnostics have the power to improve upon the predictive power of Gleason pattern. Though the goal of screening is to identify men with potentially lethal disease, many patients are diagnosed with apparently indolent disease which is best managed with active surveillance. Indeed, an active surveillance approach was shown in the ProtecT trial to generally be safe, with 10-year cancer-specific survival rate of 98.8%, similar to that of prostatectomy or radiation therapy [43]. Despite increases over time, still only 20% of patients actually undergo active surveillance [44, 45].

It is not known definitively why preference for active surveillance is not higher, but it is likely due to a concern from both clinicians and patients for undiagnosed higher risk disease or disease progression while on active surveillance [46]. Indeed, selection of patients for active surveillance can be imprecise, based on risk assessment from biopsy results, and thus limited to the tissue that has been sampled. This has major limitations, as the rate of undersampling is estimated to be 23–35% [47, 48, 49, 50]. Since the rate of upgrade is as high on early repeat biopsy versus later biopsies, it is generally concluded that undersampling, rather than de novo disease or subclonal progression over time, is the primary driver of pathologic upgrade in a majority of cases [49, 51, 52, 53]. Nonetheless, due to upgrade or other triggers, approximately 50% of patients eventually undergo primary intervention [43].

3.1. Precision imaging modalities for detecting aggressive prostate cancer

Amongst the promising approaches for improved sampling of clinically meaningful disease is using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which has superior in-plane resolution enabling better lesion detection in comparison with other available imaging modalities. Although MRI has been used to localize prostate cancer for nearly two decades, its initial use was for staging of prostate cancer in patients with documented diagnoses. In contrast, the last half decade has seen its primary use shift to lesion localization prior to biopsies and ultimately as a guide for these biopsies [54]. MRI can be utilized in several ways to guide prostate biopsies including cognitive, direct in-bore, and transrectal ultrasound/MRI (TRUS/MRI) fusion approaches.

3.1.1 Fusion-guided biopsy as a precision approach driven by imaging

Regardless of the utilization technique, incorporation of MRI for biopsies has been reported to improve diagnostic precision and yield. A large series of 1003 cases from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) demonstrated increased diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer by MRI guided biopsy, and decreased diagnosis of indolent cancers, compared to the standard-of-care 12-core systematic approach [55]. Similar results have been reported by many centers, and if practiced widely could improve precision for better diagnosis, enriching for tumor and better sampling the extent of disease.

The Achilles heel of this novel technique is a limited number of prospective and randomized clinical trials. To date there is only one such study, which included 1140 patients randomized into two groups (systematic biopsy versus systematic and targeted biopsy) and reported 97% accuracy in patients who were managed by MRI guidance [56]. While provocative, it should be noted that MRI and guided biopsies can still be inconclusive to diagnose clinically significant prostate cancer. In a series from the NCI, the reported rate of disease upgrade based on systematic biopsy over MRI guided biopsy was 13.5% of patients, including 5.1% to intermediate (Gleason score 7) and 1.1% to high risk (Gleason score 8 or greater) disease [57]. The major predictors of upgrading on systematic biopsy included lower PSA (p < 0.001), higher MRI prostate volume (p < 0.001), and fewer positive cores (p = 0.001). In contrast, risk factors for upgrading from MRI-guided biopsy to pathologic diagnosis by whole mount pathology included the presence of cancers invisible to MRI and tumor heterogeneity, as well as confounding procedural issues of interpretation by the MRI reader and technique complications in performing the biopsy [57]. Thus, despite its promise, further studies are needed to investigate its limitations, as well as challenges and potential solutions which otherwise preclude widespread adoption and interpretation.

3.1.2 Precision staging using multiparametric MRI

Multiparametric MRI can provide not only high anatomic resolution but also important functional data which can inform clinical practice through inferred signatures of biological processes. For example, diffusion weighted MRI (DW-MRI) visualizes free water molecule diffusivity between cells, which can provide data on tissue cellularity, and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) can noninvasively image tumor angiogenesis processes. Combination of these multiparametric imaging data has been extensively reported to provide accurate prostate cancer localization and staging [58].

Beyond its cancer detection capability, prostate MRI has also been reported to improve treatment decisions as a standalone biomarker. In a study of 133 patients, MRI was compared against the D’Amico, Epstein, and CAPRA scoring systems [59]. Whereas MRI had a sensitivity of 93% and accuracy of 92%, the sensitivity and accuracy rates for the D’Amico, Epstein, and CAPRA criteria were 93% and 70%, 64% and 88%, 93% and 59%, respectively [59]. These data suggest that MRI alone can improve specificity and sensitivity in distinguishing active surveillance and treatment candidates. [59].

Functional modalities of prostate MRI can be potentially quantified, and they also can serve as precision imaging biomarkers for describing the extent of disease. The most commonly studied quantitative MRI feature for prostate cancer is the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values extracted from DW-MRI, which were reported to have a negative correlation with tumor Gleason scores. Although some overlap exists between the ADC values of intermediate and low Gleason score prostate cancer, it is widely accepted that aggressive cancers have lower ADC values [60, 61, 62, 63]. Currently, there are limited ongoing efforts by groups to utilize ADC values to distinguish aggressive prostate cancers from non-lethal disease using relatively novel approaches such as histogram analysis or other diffusion decay models. While these approaches are still experimental, such attempts will ensure more standardized approaches in utilizing MRI data [64, 65].

Although at experienced centers, imaging modalities can provide highly accurate information regarding a prostate cancer’s location and aggressiveness, it still can suffer from reproducibility and variation when implemented more widely, which may result in less acceptance by the community for guiding patient care. In order to overcome this, experts in cancer imaging established the Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) recommendations in 2012 [66]. This recommendation has since been revised in early 2015 to standardize prostate MRI acquisition, readout and communication steps [67]. PI-RADS version 2 has been tested in multi-reader or prospectively designed studies, and its reproducibility and utility were recently published [68, 69, 70, 71]. This standardization attempt and its further validation will enable prostate MRI to be widely adopted as a potential precision biomarker in prostate cancer management.

Another important challenge in further implementation of prostate MRI in patient care is its limitation in estimation of disease burden. As described above, prostate MRI can accurately localize cancer lesions, but due to partial volume effects prostate MRI frequently underestimates tumor burden compared to whole mount histopathology [72, 73]. Considering this limitation, a reasonable peritumoral margin should be included when prostate MRI is used in planning for focal therapy as an alternative to definitive approaches such as surgery and radiotherapy. Novel image processing-based methods such as computer aided diagnosis systems, which can enable more accurate tumor burden estimation and disease aggressiveness, are being developed as potential problem solving tools [74, 75].

3.2. Tissue-based assays for aggressive prostate cancer

3.2.1. Molecular diagnostic tests

Potentially improving upon predictive capacity of the Gleason grade would be assessing the molecular alterations corresponding to each respective pattern. Given that prostate tumor morphology is a function of its molecular phenotype, by extension the gene expression correlates of the histology may similarly predict outcome [76]. Considering that prostate cancer development may represent unchecked proliferation, the RNA-based Cell Cycle Progression (CCP) score was developed as a molecular assay requiring a modest amount of biopsy material [77]. Computed using over 10 years of follow-up data and the quantified (RT-PCR) expression for 31 CCP genes plus 15 housekeeping genes, a biopsy CCP score increase of one unit was associated with a 2.02-fold increase in prostate cancer-specific mortality, and consequently a benefit by receiving definitive treatment [77]. Myriad Genetics markets this diagnostic assay as the 46-gene Prolaris test, which has withstood extensive prospective validation, and in conjunction with other clinical data including the CAPRA nomogram score [15] further identifies those patients who despite harboring an indolent histology on biopsy are unlikely to be suitable for further active surveillance [78].

The finding that most patients who upgrade after a first biopsy do so generally on the second (and not subsequent) biopsy may describe a tumor system that initially evolves rapidly and remains relatively stable over time with respect to the development of aggressive versus indolent disease [51]. Since the appearance of Gleason pattern 4 on biopsy is given considerable weight in deciding whether surgery is an optimal intervention, predicting whether Gleason pattern 4 may have been missed in an initial biopsy would be highly desired. Genomic Health’s Oncotype DX for prostate cancer harnesses a 17-gene test which computes a score based on the weighted differential expression by RT-PCR [79]. The resulting Genomic Prostate Score, out of 100, estimates the probability that an adverse pathological feature (such as higher Gleason grade tissue and seminal vesicle invasion) would be discovered after radical prostatectomy, and thus may help guide decision-making in whether an additional biopsy might reveal higher grade disease.

3.2.2. In situ histology assays

Both the Prolaris and Oncotype DX assays attempt to better classify those patients whose clinical management decisions might be uncertain when relying only on histology of the prostate cancer biopsy. A challenge to molecular assays such as these is that while a modest amount of starting material is necessary, after local pathology review there may be insufficient quantity or quality of the tissue sample for follow-up molecular tests. In contrast, assays that accommodate a limiting amount of tissue available have an advantage of applying to more specimens. Addressing the specific question of whether the indolent-appearing Gleason 3 + 3 = 6 biopsy might be predictive of 3 + 4 = 7 tumor that would benefit from surgery, the ProMark assay from Metamark Genetics estimates a patient’s individual risk using a multiplex fluorescent 8-gene panel, requiring only 5 FFPE sections, versus 7 and 8 for Prolaris and Oncotype DX, respectively [80]. The risk score, which is reported on a continuous scale from 0 to 1, increases the odds ratio for unfavorable pathology by 3.1 for each 0.25 unit increase in risk score [80].

Amongst a myriad of commercially-available prognostic tools, perhaps the most straightforward and least expensive of tissue-based assays for prostate cancer is immunohistochemistry against PTEN, which many centers have available as a validated stain in their pathology laboratories [81]. PTEN (10q) loss is amongst the most common genomic event in all prostate cancers and is significantly enriched in Gleason score >7 cancers versus Gleason score 6 [28]. As a predictive tool, staining for PTEN protein as a surrogate of copy number predicts the likelihood of adverse pathological features upon RP when applied to biopsy specimens, such that Gleason score 6 prostate cancers that failed to stain positively for PTEN were nearly three times more likely to upgrade [82]. When considered in conjunction with FISH against MYC (8q) and LPL (8p), PTEN immunostaining of a Gleason score 6 biopsy had a 4–5-fold increase in odds that the prostate also harbored at least one focus of unsampled higher grade tumor [83].

3.3. Radiogenomics as a precision tool to detect alterations associated with aggressive disease

Radiogenomics is an emerging concept in imaging sciences which aims to provide deep information and correlation between imaging biomarkers and genomic data. The current experience is quite limited for this new approach when applied to prostate imaging. In a study of 30 patients with a total of 45 prostate cancer lesions, McCann et al. aimed to investigate associations between quantitative image features of prostate MRI and PTEN expression of peripheral zone prostate cancer [84]. They identified that 21 lesions (47%) were PTEN-positive, 12 (27%) were PTEN-negative, and 12 (27%) were mixed. They observed a weak but significant negative correlation between lesion Gleason score and PTEN expression (r = −0.30, p = 0.04) and between Kep (flux rate in DCE-MRI) and PTEN expression (r = −0.35, p = 0.02). However, they did not identify a significant correlation between apparent diffusion coefficient values, T2 signal histograms, Ktrans (contrast permeability in rate in DCE-MRI), MRI features and PTEN expression [84].

Recently, Stoyanova et al. investigated the association of MRI quantitative features with prostate cancer risk gene expression profiles in MRI guided biopsy derived tissues. With global gene expression profiles from 17 MRI guided biopsy samples of 6 patients, correlations were observed between 49 radiomic features and the Decipher score, the Genomic Prostate Score, and the Cell Cycle Progression score. There were significant correlations between these genes and quantitative imaging features, suggesting the presence of a prostate cancer prognostic signal in the radiomic features and potential utility in harnessing both approaches [85].

3.4 Tissue-imaging correlates as a precision approach to predict pathologic features

DCE-MRI has been less commonly utilized as a component of prostate MRI since its benefit is thought to be minimal compared to T2-weighted (T2W) and DW-MRI. However, DCE-MRI can aid to detect tumor angiogenesis at early stages of prostate cancer [86]. Despite it being the oldest quantitative technique of prostate MRI, it is generally used qualitatively because its parameters such as Ktrans, and kep were shown not to correlate with tumor aggressiveness [61]. Therefore, recent studies have aimed to correlate prostate MRI signal characteristics with digital pathology in clinical samples. In particular, Kwak et al. reported a systematic approach to correlate in vivo MRI with hematoxylin and eosin stained digital pathology images segmented by a machine learning approach [87]. Within each scanned slide, software independently assessed the density of cellular (nucleus) and tissue components (lumen, epithelium, and stroma). This information was used to generate a density map for the entire prostate to overlay on the MRI imaging, and then were compared across patients to distinguish significant differences between cancer, benign peripheral zone, and benign prostatic hyperplasia [87]. Such novel correlation attempts will help us better understand the strength of prostate MRI and its utility to complement tissue based approaches to provide a thorough, customized, and precise paradigm to identify those patients likely to benefit from definitive treatment.

4. TREAT MORE VERSUS OBSERVE: PRECISION BIOMARKERS FOR MANAGEMENT

If the patient undergoes a radical prostatectomy and PSA levels decline to undetectable, then he is considered to be in remission until such time that PSA levels rise and/or the tumor becomes visible on one or more imaging modalities. Following pathology review of the RP specimen, many practitioners will make the decision to recommend external adjuvant radiation therapy (ART) based on pathological features alone (even with an undetectable PSA) such as Gleason pattern 5, extraprostatic extension, the number of lymph nodes involved [88], or positive surgical margins. Due to risks associated with ART many high risk patients wait until BCR and then receive salvage radiation therapy (SRT), as there are currently no other blood-based indicators other than a rising PSA following RP that warrant the use of SRT [89]. Importantly, patients who receive SRT will generally have a better outcome if SRT is administered when PSA is lower, which is when the tumor cells are likely still localized to the pelvis [90]. However, due to significant complications of RT, and since some patients with adverse features may not have recurrence, many urologists and oncologists wait for repeated rises in PSA before referral for SRT. For some patients, this may be past the window at which SRT would have been curative [90]. Precision tools that harness distinct imaging and molecular features of the tumor at the time of RP may predict the risk of recurrence or death and potential benefit from earlier radiation therapy.

4.1. Molecular tests

As recurrence is driven by metastasis, GenomeDX Biosciences offers the Decipher genomic test in which FFPE tissue is processed by Affymetrix Exon 1.0 microarray and the probe intensities of 22 genes are imputed into a genomic classifier score ranging from 0 to 1 and classifies patients based on their risk of metastasis [91]. Originally designed for guiding the treatment of men following radical prostatectomy, the genomic classifier was validated to define a 22% risk of metastasis at 5 years in the high risk category, and 47% risk 10 years after RP, with a hazard ratio of 1.85 for every 0.1-unit increase in score [92] when used in conjunction with NCCN guidelines. Decipher was further shown to have the greatest power to predict metastasis on tissue acquired from needle biopsy specimens prior to radical prostatectomy, in men whose disease metastasized 10 years post-RP [93]. When used as the basis for patients receiving earlier radiation therapy, 5% of patients with higher genomic classifier scores who received adjuvant radiation therapy experienced metastases within five years, versus the 23% of patients with similar scores but received salvage radiation therapy instead [94]. Similarly, the 24-gene Post-Operative Radiation Therapy Outcomes Score (PORTOS) was developed to predict response to radiation therapy, such that men with a high PORTOS score who received adjuvant radiation therapy did not experience metastases within 10 years (35% of cohort) versus those who did not receive ART (4%) [95]. These findings argue strongly towards potential benefit in using precision tissue assays such as Decipher and PORTOS amongst high risk patients, and warrants further trials testing whether aggressive disease treated earlier with radiation therapy provides an overall or progression-free survival benefit.

4.2. PSMA positron emission tomography

Salvage radiation therapy for early biochemical recurrence is used when it is predicted the recurrence is local. Imaging technology enabling specific localization of a PSA-producing disease focus could enable more precise intervention for a more durable response. Unfortunately, current imaging techniques are not adequate to localize the physical location of biochemical recurrence (BCR) to initiate potentially curative radiotherapy. While Prostate MRI has promising results in patients experiencing BCR, it has a limited sensitivity at low PSA values and limited specificity since treatment related changes can easily overlap with those of cancer [96, 97].

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has the capacity to target specific metabolic processes and proteins, using radiolabeled small molecules. Advancing the utility of PET in the early BCR setting has been the recent interest in imaging prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) by using 18F or 68Ga labelled PSMA targeting tracers. In a large cohort of 391 patients, Afshar-Oromieh et al. reported lesion-based sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) of 76.6%, 100%, 91.4% and 100%, respectively with 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT. As a potential precision tool, patient-based sensitivity was 88.1% [98].

Eiber et al. retrospectively compared the cancer detection rate of 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT versus serum PSA in 248 patients experiencing biochemical recurrence. Lesions were detected in 89.5% of participants, and in comparison to PSA, the cancer detection rates were 96.8%, 93.0%, 72.7%, and 57.9% for PSA levels of ≥ 2, 1 to < 2, 0.5 to < 1, and 0.2 to < 0.5 ng/mL, respectively. Importantly, detection rates increased with a higher PSA velocity (81.8%, 82.4%, 92.1%, and 100% in < 1, 1 to < 2, 2 to < 5, and ≥ 5 ng/mL/y, respectively.

While these studies provide encouraging data localizing sites of biochemical recurrence in the context of lower PSA values, they still suffer from a lack of histopathological validation [99]. Therefore, although promising results are reported with PSMA-targeting PET agents, the findings in these and future studies should be validated with histopathology or clinical follow up for them, prior to their widespread adoption and use as a precision tool for clinical practice.

5. CONCLUSION

For patients with localized prostate cancer, the application of precision biomarkers currently extends beyond drug sensitivity and instead reflects the management of risk. The precision tools for predicting risk can offer distinct advantages for determining when a patient should be screened or treated for localized prostate cancer, and how best to manage the patient to decrease the risk of recurrence. Fundamentally, precision tools reflect a rational design through which the assay is capable of accurately identifying those patients with greater risk; predictive measures built by comparing aggressive versus indolent outcomes capture and recapitulate the disease’s aggressiveness as a surrogate of the tumor’s biology.

6. EXPERT COMMENTARY

A mandate for using precision tools to guide diagnosis and management of patients with locally-advanced and hig risk prostate cancer is not a suggestion to order a battery of molecular and imaging tests irrespective of prevailing conventional data. In many cases, precision prostate cancer biomarkers hold high value when conventional indicators such as PSA, Gleason grade and CT and bone scan fail to classify a patient’s risk with acceptable confidence. Certainly, the initial internal and external validation studies for many of these tests lend considerable promise towards their widespread adoption in the clinic. Moving forward, long-term outcome studies will be needed to assess whether treatment decisions guided by these precision assays improve overall survival or limit toxicity without reducing survival.

As imaging modalities including TRUS/MRI fusion for biopsies and mpMRI are adopted more widely for staging and management of prostate cancer, their utility to guide management is not surprisingly linked to the skill and experience of the operator and reader. These new technologies are neither standardized in their acquisition nor the interpretation of the data they generate, with substantial risk of intraobserver variability, given the qualitative nature for many imaging readouts. Greater access to expertise via workshops and training may partially remedy this issue. Current efforts at the NCI include developing machine learning systems for computer-assisted and quantitative reporting of imaging results. Standardization must be achieved before these advanced imaging modalities are integrated into precision management paradigms.

As every biomarker and precision assay is intended to reflect biological surrogates for the aggressiveness of the tumor, it is surprising how few studies have correlated changes to the genomic landscapes and the molecular alterations of aggressive prostate cancers with distinguishing features on mpMRI. Given the rising popularity of targeted treatments and predicted outcomes based on genomic alterations, there is tremendous potential opportunity in the development of machine learning imaging analyses which could predict one or more genetic or genomic alterations with predictive or prognostic capacity. Similarly, given how both imaging and tissue biomarkers are designed to predict response to treatment, increased reliance on the results of an imaging modality could be enhanced if consistency is demonstrated by applying a tissue-based assay to the same case and observing concordance, and vice versa.

Finally, a concern for many men given the availability of intense androgen deprivation therapies is the pressure for the tumor to evolve towards a neuroendocrine differentiation pathway, either partially sharing or eliminating in total the adenocarcinoma and androgen responsive phenotypes of the cancer, which occurs in approximately 20–40% of advanced prostate cancer patients [100]. As the ancestral clone for neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC) likely exists as a minor subclone that evolves early in the development of the tumor, strategies to identify and target this variant early may lend itself towards a more durable response with taxanes and platinum chemotherapies before antiandrogen treatment would normally be exhausted. Given the limited follow-up on this patient population, it is not surprising that there are no precision tests that have been designed to predict future NEPC differentiation in the localized prostate cancer setting.

FIVE-YEAR REVIEW

While PSA testing has led to a reduction in prostate cancer mortality, it came at the cost of overtreatment, exposing many who would not have died from prostate cancer to the morbidity associated with its treatment. Avoiding overtreatment but maintaining reductions of cancer-specific mortality remains a major challenge for the field, as evidenced by the recent advances in molecular and imaging precision tools to guide screening, treating, and subsequent management decisions that this conundrum has spurred.

While the emergence of multiple precision tools might predict widespread adoption in the coming years, key barriers must first be overcome. Early data are promising for the use of molecular tests to improve predictions of adverse pathology or recurrence, but there is still a lack of data demonstrating improvements in survival or reduced morbidity when these assays are implemented. We anticipate that in the next five years, additional studies will reveal which screening methods and tissue-based assays accurately identify those patients who both receive treatment and experience an overall survival benefit. We further expect such studies will better identify which patient population would benefit best from a given precision assay, taking into context one or more conventional risk factors rather than competing with them.

Given the shortcomings of systematic biopsies and conventional imaging to accurately represent the nature and extent of disease, we expect there will be a rapid increase in the reliance on mpMRI and PMSA-based imaging for guiding management decisions. The long natural history of localized prostate cancer, making correlations with overall survival difficult, and the continued molecular characterization of high risk disease likely mean there will be increased correlation of MRI features and molecular features that are themselves correlated with survival. While PMSA-based imaging appears to be extremely specific and have high sensitivity, the clinical implication of a positive or negative scan is yet to be determined. Perhaps even more important than the continued development of new imaging techniques will be efforts to use machine-learning and other approaches to more easily disseminate imaging expertise. Consequently, widespread adoption of new imaging modalities will require standardized administration and reliable reporting and interpretation.

KEY ISSUES.

Evaluating risk SNPs and additional bloodborne and urine-based tests identify patients at higher risk of having prostate cancer.

Germline BRCA2 alterations, the 4K score, and PCA3 are promising in predicting risk of clinically significant disease.

Decipher and Oncotype DX expression-based assays inform prognosis of sampled disease, and TRUS/MRI fusion biopsies reduce the risk of undersampling, although operator expertise may affect the precision of this approach.

Prolaris and PORTOS tissue-based tests and PSMA-based staging offer predictive benefit for determining whether adjuvant or salvage radiation therapy may be appropriate.

Future studies will include integrating imaging and molecular assays and standardizing implementation and interpretation of imaging modalities.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

* of interest

** of considerable interest

- 1.Robinson JG, Hodges EA, Davison J. Prostate-specific antigen screening: a critical review of current research and guidelines. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014;26:574–81. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safdieh JJ, Schwartz D, Weiner JP, Nwokedi E, Schreiber D. The need for more aggressive therapy for men with Gleason 9–10 disease compared to Gleason </=8 high-risk prostate cancer. Tumori. 2016;102:168–73. doi: 10.5301/tj.5000475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong MC, Goggins WB, Wang HH, Fung FD, Leung C, Wong SY, Ng CF, Sung JJ. Global Incidence and Mortality for Prostate Cancer: Analysis of Temporal Patterns and Trends in 36 Countries. European urology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welch HG, Gorski DH, Albertsen PC. Trends in Metastatic Breast and Prostate Cancer--Lessons in Cancer Dynamics. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1685–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1510443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, 3rd, Buys SS, Chia D, Church TR, Fouad MN, Gelmann EP, Kvale PA, Reding DJ, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi LA, O’Brien B, Clapp JD, Rathmell JM, Riley TL, Hayes RB, Kramer BS, Izmirlian G, Miller AB, Pinsky PF, Prorok PC, Gohagan JK, Berg CD, Team PP. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1310–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, Kwiatkowski M, Lujan M, Lilja H, Zappa M, Denis LJ, Recker F, Berenguer A, Maattanen L, Bangma CH, Aus G, Villers A, Rebillard X, van der Kwast T, Blijenberg BG, Moss SM, de Koning HJ, Auvinen A, Investigators E. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, 3rd, Buys SS, Chia D, Church TR, Fouad MN, Isaacs C, Kvale PA, Reding DJ, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi LA, O’Brien B, Ragard LR, Clapp JD, Rathmell JM, Riley TL, Hsing AW, Izmirlian G, Pinsky PF, Kramer BS, Miller AB, Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Team PP. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104:125–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Zappa M, Nelen V, Kwiatkowski M, Lujan M, Maattanen L, Lilja H, Denis LJ, Recker F, Paez A, Bangma CH, Carlsson S, Puliti D, Villers A, Rebillard X, Hakama M, Stenman UH, Kujala P, Taari K, Aus G, Huber A, van der Kwast TH, van Schaik RH, de Koning HJ, Moss SM, Auvinen A, Investigators E. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. This report of the European Randomized study of Screening for Prostate Cancer describes a substantial reduction in prostate cancer-specific mortality attributable to PSA screening. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moyer VA Force USPST. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:120–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ploussard G, Mongiat-Artus P. Words of wisdom: Re: Active surveillance program for prostate cancer: an update of the Johns Hopkins experience. European urology. 2011;60:597. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.012. Epub 2011/08/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reese AC, Landis P, Han M, Epstein JI, Carter HB. Expanded criteria to identify men eligible for active surveillance of low risk prostate cancer at Johns Hopkins: a preliminary analysis. J Urol. 2013;190:2033–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooperberg MR, Cowan JE, Hilton JF, Reese AC, Zaid HB, Porten SP, Shinohara K, Meng MV, Greene KL, Carroll PR. Outcomes of active surveillance for men with intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:228–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Schultz D, Blank K, Broderick GA, Tomaszewski JE, Renshaw AA, Kaplan I, Beard CJ, Wein A. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooperberg MR, Pasta DJ, Elkin EP, Litwin MS, Latini DM, Du Chane J, Carroll PR. The University of California, San Francisco Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score: a straightforward and reliable preoperative predictor of disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173:1938–42. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158155.33890.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albright F, Stephenson RA, Agarwal N, Teerlink CC, Lowrance WT, Farnham JM, Albright LA. Prostate cancer risk prediction based on complete prostate cancer family history. The Prostate. 2015;75:390–8. doi: 10.1002/pros.22925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolla M, Van Tienhoven G, Warde P, Dubois JB, Mirimanoff RO, Storme G, Bernier J, Kuten A, Sternberg C, Billiet I, Torecilla JL, Pfeffer R, Cutajar CL, Van der Kwast T, Collette L. External irradiation with or without long-term androgen suppression for prostate cancer with high metastatic risk: 10-year results of an EORTC randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1066–73. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roach M, 3rd, Bae K, Speight J, Wolkov HB, Rubin P, Lee RJ, Lawton C, Valicenti R, Grignon D, Pilepich MV. Short-term neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy and external-beam radiotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: long-term results of RTOG 8610. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:585–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roehl KA, Han M, Ramos CG, Antenor JA, Catalona WJ. Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3,478 consecutive patients: long-term results. J Urol. 2004;172:910–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000134888.22332.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paller CJ, Antonarakis ES. Management of biochemically recurrent prostate cancer after local therapy: evolving standards of care and new directions. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2013;11:14–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kupelian PA, Mahadevan A, Reddy CA, Reuther AM, Klein EA. Use of different definitions of biochemical failure after external beam radiotherapy changes conclusions about relative treatment efficacy for localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2006;68:593–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, Eisenberger M, Dorey FJ, Walsh PC, Partin AW. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2005;294:433–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlsson S, Vickers AJ, Roobol M, Eastham J, Scardino P, Lilja H, Hugosson J. Prostate cancer screening: facts, statistics, and interpretation in response to the US Preventive Services Task Force Review. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:2581–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eeles R, Goh C, Castro E, Bancroft E, Guy M, Al Olama AA, Easton D, Kote-Jarai Z. The genetic epidemiology of prostate cancer and its clinical implications. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:18–31. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro E, Mikropoulos C, Bancroft EK, Dadaev T, Goh C, Taylor N, Saunders E, Borley N, Keating D, Page EC, Saya S, Hazell S, Livni N, deSouza N, Neal D, Hamdy FC, Kumar P, Antoniou AC, Kote-Jarai Z, Committee PSS, Eeles RA. The PROFILE Feasibility Study: Targeted Screening of Men With a Family History of Prostate Cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21:716–22. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teerlink CC, Thibodeau SN, McDonnell SK, Schaid DJ, Rinckleb A, Maier C, Vogel W, Cancel-Tassin G, Egrot C, Cussenot O, Foulkes WD, Giles GG, Hopper JL, Severi G, Eeles R, Easton D, Kote-Jarai Z, Guy M, Cooney KA, Ray AM, Zuhlke KA, Lange EM, Fitzgerald LM, Stanford JL, Ostrander EA, Wiley KE, Isaacs SD, Walsh PC, Isaacs WB, Wahlfors T, Tammela T, Schleutker J, Wiklund F, Gronberg H, Emanuelsson M, Carpten J, Bailey-Wilson J, Whittemore AS, Oakley-Girvan I, Hsieh CL, Catalona WJ, Zheng SL, Jin G, Lu L, Xu J, Camp NJ, Cannon-Albright LA International Consortium for Prostate Cancer G. Association analysis of 9,560 prostate cancer cases from the International Consortium of Prostate Cancer Genetics confirms the role of reported prostate cancer associated SNPs for familial disease. Hum Genet. 2014;133:347–56. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1384-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson D, Van Allen Eliezer M, Wu Y-M, Schultz N, Lonigro Robert J, Mosquera J-M, Montgomery B, Taplin M-E, Pritchard Colin C, Attard G, Beltran H, Abida W, Bradley Robert K, Vinson J, Cao X, Vats P, Kunju Lakshmi P, Hussain M, Feng Felix Y, Tomlins Scott A, Cooney Kathleen A, Smith David C, Brennan C, Siddiqui J, Mehra R, Chen Y, Rathkopf Dana E, Morris Michael J, Solomon Stephen B, Durack Jeremy C, Reuter Victor E, Gopalan A, Gao J, Loda M, Lis Rosina T, Bowden M, Balk Stephen P, Gaviola G, Sougnez C, Gupta M, Yu Evan Y, Mostaghel Elahe A, Cheng Heather H, Mulcahy H, True Lawrence D, Plymate Stephen R, Dvinge H, Ferraldeschi R, Flohr P, Miranda S, Zafeiriou Z, Tunariu N, Mateo J, Perez-Lopez R, Demichelis F, Robinson Brian D, Schiffman M, Nanus David M, Tagawa Scott T, Sigaras A, Eng Kenneth W, Elemento O, Sboner A, Heath Elisabeth I, Scher Howard I, Pienta Kenneth J, Kantoff P, de Bono Johann S, Rubin Mark A, Nelson Peter S, Garraway Levi A, Sawyers Charles L, Chinnaiyan Arul M. Integrative Clinical Genomics of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Network CGAR. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell. 2015;163:1011–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, De Sarkar N, Abida W, Beltran H, Garofalo A, Gulati R, Carreira S, Eeles R, Elemento O, Rubin MA, Robinson D, Lonigro R, Hussain M, Chinnaiyan A, Vinson J, Filipenko J, Garraway L, Taplin ME, AlDubayan S, Han GC, Beightol M, Morrissey C, Nghiem B, Cheng HH, Montgomery B, Walsh T, Casadei S, Berger M, Zhang L, Zehir A, Vijai J, Scher HI, Sawyers C, Schultz N, Kantoff PW, Solit D, Robson M, Van Allen EM, Offit K, de Bono J, Nelson PS. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30**.Bancroft EK, Page EC, Castro E, Lilja H, Vickers A, Sjoberg D, Assel M, Foster CS, Mitchell G, Drew K, Maehle L, Axcrona K, Evans DG, Bulman B, Eccles D, McBride D, van Asperen C, Vasen H, Kiemeney LA, Ringelberg J, Cybulski C, Wokolorczyk D, Selkirk C, Hulick PJ, Bojesen A, Skytte AB, Lam J, Taylor L, Oldenburg R, Cremers R, Verhaegh G, van Zelst-Stams WA, Oosterwijk JC, Blanco I, Salinas M, Cook J, Rosario DJ, Buys S, Conner T, Ausems MG, Ong KR, Hoffman J, Domchek S, Powers J, Teixeira MR, Maia S, Foulkes WD, Taherian N, Ruijs M, Helderman-van den Enden AT, Izatt L, Davidson R, Adank MA, Walker L, Schmutzler R, Tucker K, Kirk J, Hodgson S, Harris M, Douglas F, Lindeman GJ, Zgajnar J, Tischkowitz M, Clowes VE, Susman R, Ramon y Cajal T, Patcher N, Gadea N, Spigelman A, van Os T, Liljegren A, Side L, Brewer C, Brady AF, Donaldson A, Stefansdottir V, Friedman E, Chen-Shtoyerman R, Amor DJ, Copakova L, Barwell J, Giri VN, Murthy V, Nicolai N, Teo SH, Greenhalgh L, Strom S, Henderson A, McGrath J, Gallagher D, Aaronson N, Ardern-Jones A, Bangma C, Dearnaley D, Costello P, Eyfjord J, Rothwell J, Falconer A, Gronberg H, Hamdy FC, Johannsson O, Khoo V, Kote-Jarai Z, Lubinski J, Axcrona U, Melia J, McKinley J, Mitra AV, Moynihan C, Rennert G, Suri M, Wilson P, Killick E, Collaborators I, Moss S, Eeles RA. Targeted prostate cancer screening in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the initial screening round of the IMPACT study. European urology. 2014;66:489–99. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.003. This report from the IMPACT study describes an enrichment for aggressive disease when PSA screening is targeted to BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvalhal GF, Daudi SN, Kan D, Mondo D, Roehl KA, Loeb S, Catalona WJ. Correlation between serum prostate-specific antigen and cancer volume in prostate glands of different sizes. Urology. 2010;76:1072–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Partin AW, Catalona WJ, Southwick PC, Subong EN, Gasior GH, Chan DW. Analysis of percent free prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer detection: influence of total PSA, prostate volume, and age. Urology. 1996;48:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang YQ, Sun T, Zhong WD, Wu CL. Clinical performance of serum [−2]proPSA derivatives, %p2PSA and PHI, in the detection and management of prostate cancer. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2014;2:343–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lazzeri M, Haese A, de la Taille A, Palou Redorta J, McNicholas T, Lughezzani G, Scattoni V, Bini V, Freschi M, Sussman A, Ghaleh B, Le Corvoisier P, Alberola Bou J, Esquena Fernandez S, Graefen M, Guazzoni G. Serum isoform [−2]proPSA derivatives significantly improve prediction of prostate cancer at initial biopsy in a total PSA range of 2–10 ng/ml: a multicentric European study. European urology. 2013;63:986–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Punnen S, Pavan N, Parekh DJ. Finding the Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: The 4Kscore Is a Novel Blood Test That Can Accurately Identify the Risk of Aggressive Prostate Cancer. Rev Urol. 2015;17:3–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stattin P, Vickers AJ, Sjoberg DD, Johansson R, Granfors T, Johansson M, Pettersson K, Scardino PT, Hallmans G, Lilja H. Improving the Specificity of Screening for Lethal Prostate Cancer Using Prostate-specific Antigen and a Panel of Kallikrein Markers: A Nested Case-Control Study. European urology. 2015;68:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groskopf J, Aubin SM, Deras IL, Blase A, Bodrug S, Clark C, Brentano S, Mathis J, Pham J, Meyer T, Cass M, Hodge P, Macairan ML, Marks LS, Rittenhouse H. APTIMA PCA3 molecular urine test: development of a method to aid in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1089–95. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.063289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pellegrini KL, Sanda MG, Moreno CS. RNA biomarkers to facilitate the identification of aggressive prostate cancer. Mol Aspects Med. 2015;45:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loeb S, Partin AW. Review of the literature: PCA3 for prostate cancer risk assessment and prognostication. Rev Urol. 2011;13:e191–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomlins SA, Aubin SM, Siddiqui J, Lonigro RJ, Sefton-Miller L, Miick S, Williamsen S, Hodge P, Meinke J, Blase A, Penabella Y, Day JR, Varambally R, Han B, Wood D, Wang L, Sanda MG, Rubin MA, Rhodes DR, Hollenbeck B, Sakamoto K, Silberstein JL, Fradet Y, Amberson JB, Meyers S, Palanisamy N, Rittenhouse H, Wei JT, Groskopf J, Chinnaiyan AM. Urine TMPRSS2:ERG fusion transcript stratifies prostate cancer risk in men with elevated serum PSA. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:94ra72. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomlins SA, Day JR, Lonigro RJ, Hovelson DH, Siddiqui J, Kunju LP, Dunn RL, Meyer S, Hodge P, Groskopf J, Wei JT, Chinnaiyan AM. Urine TMPRSS2:ERG Plus PCA3 for Individualized Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment. European urology. 2016;70:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epstein JI. An update of the Gleason grading system. J Urol. 2010;183:433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, Mason M, Metcalfe C, Holding P, Davis M, Peters TJ, Turner EL, Martin RM, Oxley J, Robinson M, Staffurth J, Walsh E, Bollina P, Catto J, Doble A, Doherty A, Gillatt D, Kockelbergh R, Kynaston H, Paul A, Powell P, Prescott S, Rosario DJ, Rowe E, Neal DE, Protec TSG. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1415–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. This report from the ProtecT study describing that active surveillance offered the same benefit as radiation therapy and surgery in a low risk population over the course of 10 years. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barocas DA, Cowan JE, Smith JA, Jr, Carroll PR, Ca PI. What percentage of patients with newly diagnosed carcinoma of the prostate are candidates for surveillance? An analysis of the CaPSURE database. J Urol. 2008;180:1330–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.019. discussion 4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiner AB, Patel SG, Etzioni R, Eggener SE. National trends in the management of low and intermediate risk prostate cancer in the United States. J Urol. 2015;193:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sowalsky AG, Ye H, Bubley GJ, Balk SP. Clonal Progression of Prostate Cancers from Gleason Grade 3 to Grade 4. Cancer Research. 2013;73:1050–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conti SL, Dall’era M, Fradet V, Cowan JE, Simko J, Carroll PR. Pathological outcomes of candidates for active surveillance of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2009;181:1628–33. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.107. discussion 33–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berglund RK, Masterson TA, Vora KC, Eggener SE, Eastham JA, Guillonneau BD. Pathological upgrading and up staging with immediate repeat biopsy in patients eligible for active surveillance. J Urol. 2008;180:1964–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.051. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Porten SP, Whitson JM, Cowan JE, Cooperberg MR, Shinohara K, Perez N, Greene KL, Meng MV, Carroll PR. Changes in prostate cancer grade on serial biopsy in men undergoing active surveillance. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2795–800. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jain S, Loblaw A, Vesprini D, Zhang L, Kattan MW, Mamedov A, Jethava V, Sethukavalan P, Yu C, Klotz L. Gleason Upgrading with Time in a Large Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance Cohort. J Urol. 2015;194:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Penney KL, Stampfer MJ, Jahn JL, Sinnott JA, Flavin R, Rider JR, Finn S, Giovannucci E, Sesso HD, Loda M, Mucci LA, Fiorentino M. Gleason grade progression is uncommon. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5163–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tosoian JJ, Mamawala M, Epstein JI, Landis P, Wolf S, Trock BJ, Carter HB. Intermediate and Longer-Term Outcomes From a Prospective Active-Surveillance Program for Favorable-Risk Prostate Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:3379–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.VanderWeele DJ, Brown CD, Taxy JB, Gillard M, Hatcher DM, Tom WR, Stadler WM, White KP. Low-grade prostate cancer diverges early from high grade and metastatic disease. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1079–85. doi: 10.1111/cas.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown AM, Elbuluk O, Mertan F, Sankineni S, Margolis DJ, Wood BJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL, Turkbey B. Recent advances in image-guided targeted prostate biopsy. Abdominal imaging. 2015;40:1788–99. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0353-8. Epub 2015/01/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siddiqui MM, Rais-Bahrami S, Turkbey B, George AK, Rothwax J, Shakir N, Okoro C, Raskolnikov D, Parnes HL, Linehan WM, Merino MJ, Simon RM, Choyke PL, Wood BJ, Pinto PA. Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Jama. 2015;313:390–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17942. Epub 2015/01/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Panebianco V, Barchetti F, Sciarra A, Ciardi A, Indino EL, Papalia R, Gallucci M, Tombolini V, Gentile V, Catalano C. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging vs. standard care in men being evaluated for prostate cancer: a randomized study. Urologic oncology. 2015;33:17.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.09.013. Epub 2014/12/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57*.Muthigi A, George AK, Sidana A, Kongnyuy M, Simon R, Moreno V, Merino MJ, Choyke PL, Turkbey B, Wood BJ, Pinto PA. Missing the Mark: Prostate Cancer Upgrading by Systematic Biopsy over Magnetic Resonance Imaging/Transrectal Ultrasound Fusion Biopsy. The Journal of urology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.08.097. Epub 2016/10/22. TRUS/MRI fusion targeted biopsies decrease the upgrade rate following radical prostatectomy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turkbey B, Mani H, Shah V, Rastinehad AR, Bernardo M, Pohida T, Pang Y, Daar D, Benjamin C, McKinney YL, Trivedi H, Chua C, Bratslavsky G, Shih JH, Linehan WM, Merino MJ, Choyke PL, Pinto PA. Multiparametric 3T prostate magnetic resonance imaging to detect cancer: histopathological correlation using prostatectomy specimens processed in customized magnetic resonance imaging based molds. The Journal of urology. 2011;186:1818–24. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.013. Epub 2011/09/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turkbey B, Mani H, Aras O, Ho J, Hoang A, Rastinehad AR, Agarwal H, Shah V, Bernardo M, Pang Y, Daar D, McKinney YL, Linehan WM, Kaushal A, Merino MJ, Wood BJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL. Prostate cancer: can multiparametric MR imaging help identify patients who are candidates for active surveillance? Radiology. 2013;268:144–52. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121325. Epub 2013/03/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hambrock T, Hoeks C, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa C, Scheenen T, Futterer J, Bouwense S, van Oort I, Schroder F, Huisman H, Barentsz J. Prospective assessment of prostate cancer aggressiveness using 3-T diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging-guided biopsies versus a systematic 10-core transrectal ultrasound prostate biopsy cohort. European urology. 2012;61:177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.08.042. Epub 2011/09/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oto A, Yang C, Kayhan A, Tretiakova M, Antic T, Schmid-Tannwald C, Eggener S, Karczmar GS, Stadler WM. Diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of prostate cancer: correlation of quantitative MR parameters with Gleason score and tumor angiogenesis. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2011;197:1382–90. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6861. Epub 2011/11/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Renard Penna R, Cancel-Tassin G, Comperat E, Mozer P, Leon P, Varinot J, Roupret M, Bitker MO, Lucidarme O, Cussenot O. Apparent diffusion coefficient value is a strong predictor of unsuspected aggressiveness of prostate cancer before radical prostatectomy. World journal of urology. 2016;34:1389–95. doi: 10.1007/s00345-016-1789-3. Epub 2016/02/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turkbey B, Shah VP, Pang Y, Bernardo M, Xu S, Kruecker J, Locklin J, Baccala AA, Jr, Rastinehad AR, Merino MJ, Shih JH, Wood BJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL. Is apparent diffusion coefficient associated with clinical risk scores for prostate cancers that are visible on 3-T MR images? Radiology. 2011;258:488–95. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100667. Epub 2010/12/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donati OF, Mazaheri Y, Afaq A, Vargas HA, Zheng J, Moskowitz CS, Hricak H, Akin O. Prostate cancer aggressiveness: assessment with whole-lesion histogram analysis of the apparent diffusion coefficient. Radiology. 2014;271:143–52. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130973. Epub 2014/01/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pang Y, Turkbey B, Bernardo M, Kruecker J, Kadoury S, Merino MJ, Wood BJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL. Intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging for prostate cancer: an evaluation of perfusion fraction and diffusion coefficient derived from different b-value combinations. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2013;69:553–62. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24277. Epub 2012/04/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, Choyke P, Verma S, Villeirs G, Rouviere O, Logager V, Futterer JJ. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. European radiology. 2012;22:746–57. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y. Epub 2012/02/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barentsz JO, Weinreb JC, Verma S, Thoeny HC, Tempany CM, Shtern F, Padhani AR, Margolis D, Macura KJ, Haider MA, Cornud F, Choyke PL. Synopsis of the PI-RADS v2 Guidelines for Multiparametric Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Recommendations for Use. European urology. 2016;69:41–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.08.038. Epub 2015/09/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Greer MD, Brown AM, Shih JH, Summers RM, Marko J, Law YM, Sankineni S, George AK, Merino MJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL, Turkbey B. Accuracy and agreement of PIRADSv2 for prostate cancer mpMRI: A multireader study. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jmri.25372. Epub 2016/07/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mertan FV, Greer MD, Shih JH, George AK, Kongnyuy M, Muthigi A, Merino MJ, Wood BJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL, Turkbey B. Prospective Evaluation of the Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2 for Prostate Cancer Detection. The Journal of urology. 2016;196:690–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.04.057. Epub 2016/04/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Muller BG, Shih JH, Sankineni S, Marko J, Rais-Bahrami S, George AK, de la Rosette JJ, Merino MJ, Wood BJ, Pinto P, Choyke PL, Turkbey B. Prostate Cancer: Interobserver Agreement and Accuracy with the Revised Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System at Multiparametric MR Imaging. Radiology. 2015;277:741–50. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142818. Epub 2015/06/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rosenkrantz AB, Ginocchio LA, Cornfeld D, Froemming AT, Gupta RT, Turkbey B, Westphalen AC, Babb JS, Margolis DJ. Interobserver Reproducibility of the PI-RADS Version 2 Lexicon: A Multicenter Study of Six Experienced Prostate Radiologists. Radiology. 2016;280:793–804. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152542. Epub 2016/04/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le Nobin J, Orczyk C, Deng FM, Melamed J, Rusinek H, Taneja SS, Rosenkrantz AB. Prostate tumour volumes: evaluation of the agreement between magnetic resonance imaging and histology using novel co-registration software. BJU international. 2014;114:E105–12. doi: 10.1111/bju.12750. Epub 2014/03/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Turkbey B, Mani H, Aras O, Rastinehad AR, Shah V, Bernardo M, Pohida T, Daar D, Benjamin C, McKinney YL, Linehan WM, Wood BJ, Merino MJ, Choyke PL, Pinto PA. Correlation of magnetic resonance imaging tumor volume with histopathology. The Journal of urology. 2012;188:1157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.011. Epub 2012/08/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Litjens GJ, Elliott R, Shih NN, Feldman MD, Kobus T, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa C, Barentsz JO, Huisman HJ, Madabhushi A. Computer-extracted Features Can Distinguish Noncancerous Confounding Disease from Prostatic Adenocarcinoma at Multiparametric MR Imaging. Radiology. 2016;278:135–45. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142856. Epub 2015/07/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang S, Burtt K, Turkbey B, Choyke P, Summers RM. Computer aided-diagnosis of prostate cancer on multiparametric MRI: a technical review of current research. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:789561. doi: 10.1155/2014/789561. Epub 2014/12/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.True L, Coleman I, Hawley S, Huang CY, Gifford D, Coleman R, Beer TM, Gelmann E, Datta M, Mostaghel E, Knudsen B, Lange P, Vessella R, Lin D, Hood L, Nelson PS. A molecular correlate to the Gleason grading system for prostate adenocarcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:10991–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603678103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cuzick J, Berney DM, Fisher G, Mesher D, Moller H, Reid JE, Perry M, Park J, Younus A, Gutin A, Foster CS, Scardino P, Lanchbury JS, Stone S, Transatlantic Prostate G. Prognostic value of a cell cycle progression signature for prostate cancer death in a conservatively managed needle biopsy cohort. British journal of cancer. 2012;106:1095–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cuzick J, Stone S, Fisher G, Yang ZH, North BV, Berney DM, Beltran L, Greenberg D, Moller H, Reid JE, Gutin A, Lanchbury JS, Brawer M, Scardino P. Validation of an RNA cell cycle progression score for predicting death from prostate cancer in a conservatively managed needle biopsy cohort. British journal of cancer. 2015;113:382–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knezevic D, Goddard AD, Natraj N, Cherbavaz DB, Clark-Langone KM, Snable J, Watson D, Falzarano SM, Magi-Galluzzi C, Klein EA, Quale C. Analytical validation of the Oncotype DX prostate cancer assay - a clinical RT-PCR assay optimized for prostate needle biopsies. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:690. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]