Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a progressive disease that affects both pediatric and adult populations. The cellular basis for RA has been investigated extensively using animal models, human tissues and isolated cells in culture. However, many aspects of its aetiology and molecular mechanisms remain unknown. Some of the electrophysiological principles that regulate secretion of essential lubricants (hyaluronan and lubricin) and cytokines from synovial fibroblasts have been identified. Data sets describing the main types of ion channels that are expressed in human synovial fibroblast preparations have begun to provide important new insights into the interplay among: (i) ion fluxes, (ii) Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum, (iii) intercellular coupling, and (iv) both transient and longer duration changes in synovial fibroblast membrane potential. A combination of this information, knowledge of similar patterns of responses in cells that regulate the immune system, and the availability of adult human synovial fibroblasts are likely to provide new pathophysiological insights.

Keywords: Ca2+‐activated K+ current, depolarization ‐ secretion coupling, IK‐Ca, Intracellular calcium, [Ca2+]i, inward rectifier K+ currents, ion channels, patch clamp, resting potential, synovial fibroblasts, Em

Background

It is well known that effective physiological function of human articular joints requires secretion of key lubricant substances. When this process fails, the likelihood of progressive osteoarthritis and/or rheumatoid arthritis increases. In human articular joints, the synovial fibroblast cell population (often denoted FLS, from ‘fibroblast‐like synovial cells’) plays a key role in this secretion. For example, both hyaluronan and lubricin are synthesized and secreted from FLS cells (Hui et al. 2012). Accordingly within the last decade, FLS preparations (in vitro and in vivo) have been used in multidisciplinary investigations of the fundamental mechanisms for the initiation and progression of rheumatoid arthritis (Huber et al. 2006; Lefèvre et al. 2009; McInnes & Schett, 2011; Bottini & Firestein, 2012; Juarez et al. 2012).

A comprehensive understanding of depolarization‐induced secretion requires detailed insight(s) into the membrane‐delimited electrophysiological processes that serve as ‘triggers’, as well as knowledge of intracellular signalling cascades in FLS preparations. In the case of the human synovial fibroblasts (sometimes also referred to as synoviocytes), a number of key underlying electrophysiological events have been identified (Bartok & Firestein, 2010). In addition, consistent patterns of responses of these cells to ligands and paracrine substances that are released into the synovial fluid during injury/inflammation and, or in the setting of progressive rheumatoid arthritis have been described (McInnes & Schett, 2011; Bottini & Firestein, 2012; Fleischmann, 2012; Hui et al. 2012).

The main purpose of this Topical Review is to summarize and integrate the electrophysiological data that are now available for mammalian synovial fibroblasts based mainly on results obtained from human FLS preparations maintained in short term culture. These findings provide some important new mechanistic information concerning electrophysiologically mediated secretion in FLS and related insights into disease aetiology and progression. Some of the important knowledge gaps that remain are also presented.

Baseline electrophysiology

Both conventional microelectrode techniques and patch clamp methods have been used in previous studies of the baseline electrophysiological characteristics and biophysical parameters of a number of different mammalian FLS preparations, including those from mouse, rabbit, bovine and human sources (Kolomytkin et al. 1997; Zimmermann et al. 2001; Large et al. 2010; Friebel et al. 2014). The published data, obtained predominantly from short term (1–3 days after enzymatic isolation) studies of low density cell cultures, yield single cell capacitance measurements in the range of 20–30 pF and corresponding input resistances between 0.5 and 2.0 GΩ (see Fig. 1). Measurements of the resting membrane potential of these types of isolated fibroblasts are surprisingly variable, ranging from −30 to −60 mV, with approx. −40 mV being most common (cf. Chilton et al. 2005 and Fig. 1).

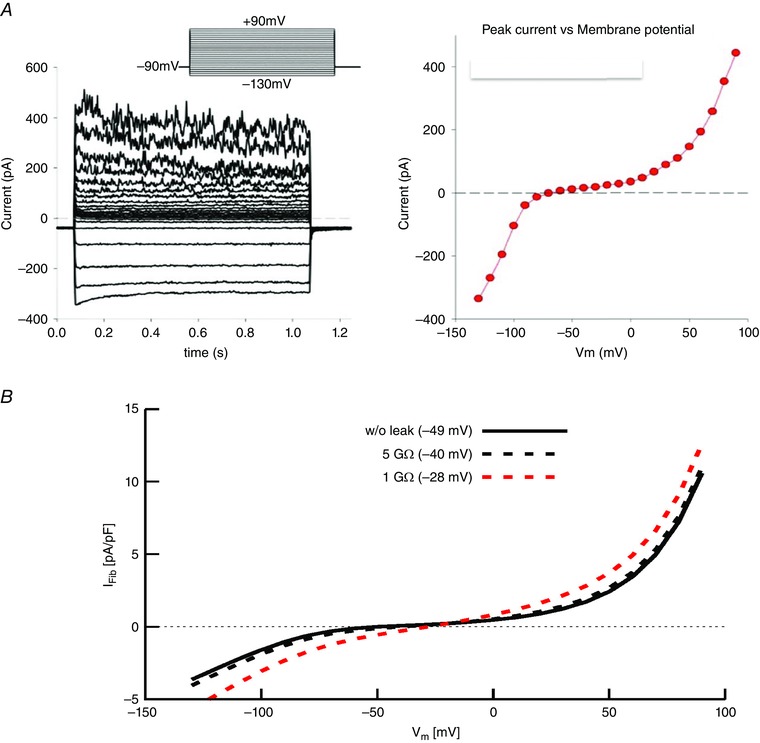

Figure 1. Current–voltage relations of a patch‐clamped human synovial fibroblast.

A, representative patch clamp recordings from a single human synovial fibroblast that had been in conventional 2‐D cell culture for approximately 3 days. From an apparent resting membrane potential of approx. −40 mV, this cell was clamped to a holding potential of −90 mV and then 1 s rectangular voltage command steps were applied in 10 mV increments in the range of −140 to +100 mV. Distinct inward K+ currents are activated by hyperpolarization; in addition, at least two different K+ currents are activated positive to approx. 0 mV. The isochronal I–V relation on the right summarizes this information (W. R. Giles & R. B. Clark, unpublished observations). B, analyses of the effects of changes in patch microelectrode seal resistance on the apparent resting potential of a single enzymatically isolated human synovial fibroblast. Three simulated N‐shaped I–V relationships are superimposed. The I–V relationship denoted by the black continuous line has been fitted to the experimental isochronal I–V data from 6 fibroblasts. Assuming that the patch electrode can form a ‘perfect’ seal, an apparent resting membrane potential of −49 mV is obtained. The data represented by dashed lines illustrate the changes in I–V curve shape and resting potentials when a linear leakage current (seal leakage) is added, assuming either a 1 GΩ (dashed red line) or 5 GΩ seal resistance (dashed black line) is introduced. As shown in the inset, the ‘seal leak’ depolarizes the ‘zero current membrane potential’ or apparent resting potential to approx. −40 mV (5 GΩ) or −28 mV (1 GΩ) from the value obtained with an infinite seal resistance –49 mV.

There appear to be two main interrelated factors that contribute to this ‘scatter’ in the reported values of resting membrane potential. First, in relatively small cells, such as mammalian synovial fibroblasts, leakage of the filling solution from the conventional microelectrode or patch clamp pipette can significantly change the intracellular milieu (Blatt & Slayman, 1983), and/or give rise to an appreciable electrochemical junction potential (Neher et al. 1992). Second, and perhaps more importantly, as shown in Fig. 1, patch clamp recordings from human synovial fibroblasts yield an N‐shaped current–voltage relationship (I–V) when either rectangular or ramp ‘command voltages’ are applied to generate these biophysical descriptors. As a consequence, in the voltage range that is close to the apparent resting membrane potential, the synovial fibroblast input resistance is very large (5–15 GΩ). This results in a requirement for exceptionally high patch pipette to FLS surface membrane seal resistances, before the ‘full’ resting membrane potential value can be recorded consistently (Wilson et al. 2011). This consideration is particularly relevant when inwardly rectifying background K+ currents are expressed. The effects of even very small changes in patch electrode‐to‐FLS ‘seal resistance’ are illustrated in Fig. 2. Note that when typical values for experimentally achieved seal resistance (for more detail see Wilson et al. 2011) are introduced into a mathematical model of a FLS cell, the apparent resting membrane potential changes because it is significantly shunted by the seal resistance, e.g. from −40 to 28 mV (cf. Bae et al. 2011). The curve fitting routines used to analyse these experimental data from individual human synovial fibroblasts and other mathematical modelling procedures are described briefly below.

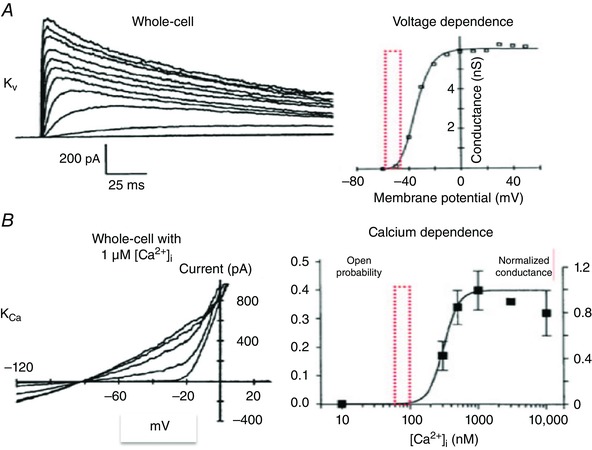

Figure 2. An illustration of plausible functional interactions of the K+ currents expressed by synovial fibroblasts based on published biophysical data from T lymphocytes.

A (left) shows a family of superimposed whole‐cell K+ currents generated in response to rectangular voltage clamp depolarizations. A (right) illustrates the voltage dependence of the activation of this ‘delayed rectifier’ K+ current. The red box is included to highlight that the normal range of the ‘resting potential’ is near the foot of the activation curve in this preparation. B (left) consists of 5 superimposed I–V curves for the predominant Ca2+‐activated K+ current in these T lymphocytes. B (right) illustrates Ca2+ dependence of channel opening for this Ca2+‐activated K+ current. Here the red box shows the normal range of resting [Ca2+]i values. These intermediate Ca2+‐dependent K+ currents can increase significantly as [Ca2+]i rises due to: (i) Ca2+ influx, (ii) Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum, or (iii) both (adapted from Cahalan & Chandy, 2009, with permission).

Mathematical model

The current through the membrane of a synovial fibroblast, I Fib, was defined as the sum of an inwardly rectifying current I Kir, a large conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ current I BK, and an unspecific background current I b:

| (1) |

Each current was assumed to be instantaneous and dependent on membrane voltage, V m. Parameters are listed in Table 1. A model to simulate the I–V relationship for I Kir was developed previously by Iyer et al. (2004):

| (2) |

with conductance G Kir, the K+ reversal voltage E K, and parameters a Kir and b Kir. E K was determined by the Nernst equation. The formulation of the large conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ current I BK was based on Horrigan & Aldrich (2002):

| (3) |

Table 1.

Constants and parameters of fibroblast model

| Name | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature (K) | T | 294 |

| Faraday's constant (C mol−1) | F | 9.65 × 104 |

| Gas constant (J K−1 mol−1) | R | 8.31 |

| Boltzmann constant (J K−1) | k | 1.38 × 10−23 |

| Elementary charge (C) | e | 1.60 × 10−19 |

| Intracellular K+ concentration (mm) | [K+]i | 120 |

| Extracellular K+ concentration (mm) | [K+]o | 5 |

| Intracellular Ca2+ concentration (nm) | [Ca+]i | 129.92 |

| Conductance for I Kir (pA pF−1) | G Kir | 23.15 |

| I Kir parameter | a Kir | 0.94 |

| I Kir parameter | b Kir | 1.26 |

| Conductance for I BK (pA pF−1) | G BK | 1784.19 |

| I BK parameter | L 0 | 2.63 × 10−9 |

| I BK parameter | zL | 0.95 |

| I BK parameter | J 0 | 4237.36 |

| I BK parameter | zJ | 1.05 |

| I BK parameter (μm) | K D | 11 |

| I BK parameter | C | 8 |

| I BK parameter | D | 25 |

| Conductance for I b (pA pF−1) | G b | 10.56 |

| Reversal voltage for I b (mV) | E b | −21.51 |

with the conductance G BK and the open probability P o. Under steady‐state conditions P o can be determined by:

| (4) |

using the parameters C, D, L 0, zL, J 0, zJ and K D. We also included a simple non‐selective and time‐independent background current I b:

| (5) |

having a conductance G b and reversal potential E b.

Several parameters in this model, i.e. G Kir, G BK, L 0, zL, J 0, G b and E b, were identified using a stochastic optimization process developed previously by us (Abbruzzese et al. 2010). In short, we calculated a fit error between experimental and simulation data using random perturbations of these parameters. In an iterative procedure, parameter sets with small fitting error were used to generate additional parameter sets, which were then evaluated again using the fitting error.

For simulations of the effect of seal leak currents we added a linear current:

| (6) |

having a conductance G Leak and a reversal potential E Leak.

Very few studies aimed at determining the ionic basis for the resting potential of FLS preparations have been published. The available data suggest that in most of these isolated single cell preparations, time‐independent or background Cl− and K+ currents both can contribute to the resting potential. Since it is now known (Ingram et al. 2008) that key physiological responses to environmental stimuli (including stretch) involve transmembrane influxes of Ca2+ and Na+, it is likely that a conventional Na+/K+ ATPase also contributes to the resting potential. Consideration of contributions from the Na+/K+ is important. This is because since even a small outward electrogenic current generated by any of the known Na+/K+ pump isoforms would be expected to contribute outward currents that could hyperpolarize the cell some 2–10 mV. Since most published electrophysiological recordings have been made at room temperature (23°C), the contribution of small but significant electrogenic currents due to Na+/K+ pump turnover will be underestimated (Ingram et al. 2008; Wann et al. 2009; Large et al. 2010).

Both in situ and in some cell culture conditions, synovial fibroblasts are arranged in very close apposition with one another. In preparations isolated from the rabbit synovium, electrophysiological recordings (Kolomytkin et al. 1999) have identified significant cell‐to‐cell communication. This electrotonic current flow occurs through conventional mechanisms, i.e. connexin‐based intercellular junctions. Interestingly, this group has also reported that one of the significant inflammatory mediators involved in rheumatoid arthritis, IL‐7, can selectively modulate this intercellular communication. Specifically, application of IL‐7 can result in reduction of this electrotonic communication, presumably as a result of inhibition of connexin‐mediated intercellular current flow (Kolomytkin et al. 1997). We note also that a different cytokine, interleukin‐1β, has been shown to increase connexin‐mediated cell‐to‐cell communication in a rabbit synovial fibroblast cell line that was maintained in tissue culture (Niger et al. 2010).

Primary cilia have been identified in mammalian FLS preparations (Rattner et al. 2010). By analogy with other articular joint preparations (chondrocytes) these cilia are likely to be sensors for shear forces. They also appear to be preferential sites for initiating intracellular Ca2+ transients (Knight et al. 2009).

Triggers for depolarization–secretion coupling

The most comprehensive work concerning physiological ‘triggers’ and related intracellular signalling cascades that are essential for depolarization–secretion coupling from the synovial fibroblast has been published from the Levick and McHale laboratories (Momberger et al. 2006; Ingram et al. 2008; Wann et al. 2009; Large et al. 2010). Fundamental new insights were gained after this group developed an instrumented rabbit knee joint preparation. It provided the possibility of controlled repetitive displacements of this joint in conjunction with: (i) synovial fluid extraction and analysis, and (ii) selective changes in both the extra‐ and intracellular milieu of these synovial fibroblasts. Levick and colleagues demonstrated that the secretion of hyaluronan from rabbit synovial fibroblasts is strongly modulated by ‘joint activity’ (measured as the number of controlled displacements of the immobilized knee). This group (Momberger et al. 2006) also showed that this activity‐dependent secretion was markedly reduced (perhaps even completely abolished) when [Ca2+]o was removed from the superfusing medium/synovial fluid. In addition, when compounds that quite selectively block protein kinase C isoforms were added to the superfusate, much reduced secretion of hyaluronan was observed. Levick and his colleagues have also reported that mitogen‐activated protein kinase activation is essential for this Ca2+‐mediated ‘activity‐dependent’ hyaluronan secretion and that this mechanosensitive hyaluronan secretion results from a Ca2+‐dependent transcription/translation process (Wann et al. 2009). Patch clamp experiments done on a subset of synovial fibroblasts isolated from this rabbit knee joint preparation showed that a number of different K+ channels and L‐type Ca2+ channels were expressed. Importantly K+ channel blockers depolarized the resting membrane potential, and a large increase (to 60 mm) in extracellular [K+] produced a significant rise in [Ca2+]i (Large et al. 2010).

Environmental sensors in synovial fibroblasts

Ion channels that are expressed in the surface membrane of synovial fibroblasts react to a wide variety of ligands that are present in synovial fluid. One of the earliest reports of this (Christensen et al. 2005) showed that a decrease in extracellular pH (pHo) resulted in a substantial increase in intracellular Ca2+, [Ca2+]i, in cultured synovial fibroblasts. This group also showed that this response to an acidic pHo is G‐protein mediated, and requires a transmembrane Ca2+ influx as a ‘trigger’. Additional work has established that this increase in [Ca2+]i is initiated by heat‐sensitive transient receptor potential (TRP) channel activation (cf. Vriens et al. 2004; Kochukov et al. 2006; Beech, 2013).

Subsequent papers have characterized this response to reduced pHo in more detail. In human synovial fibroblasts (Kolker et al. 2010) a large reduction in pHo (to approx. 5.5) consistently produced a substantial increase in [Ca2+]i as well as an associated stimulation of hyaluronan secretion. Additional experiments directed toward identifying the primary pH sensor revealed the acid‐sensitive Na+ channel ASIC III (Immke et al. 2001) as one of the essential elements in this signal transduction pathway. Small interfering (si)RNA‐mediated ASIC III knock‐down manoeuvres (Kolker et al. 2010) eliminated the significant increase in [Ca2+]i in response to pHo reduction to 5.5. However, since ASIC III channels are permeable to both Na+ and Ca2+, it is not known whether the ‘trigger cation influx’ (Vriens et al. 2004; Itoh et al. 2009; Bartok & Firestein, 2010) is mainly Na+, Ca2+ or both under these conditions.

Somewhat similar studies by the Muraki group (Itoh et al. 2009) addressed the possibility that the initial cation influx that initiates this depolarization–secretion coupling cascade was mediated by activation of TRP channels. In their preparation, human synovial fibroblasts, TRPV4 channel activation by an acidic pHo resulted in a marked increase in [Ca2+]i. Results from their TRP channel‐specific knockdown experiments established that this response to pHo had an obligatory dependence on TRPV4 expression. They also showed that depletion of the Ca2+ from the intracellular stores (the endoplasmic reticulum) markedly reduced the ability of pHo to increase [Ca2+]i.

One of the most robust and translationally relevant data sets describing TRP channel activation in FLS preparations (Beech & Sukumar, 2007; Xu et al. 2008) showed that the endogenous redox agent thioredoxin (Holmgren, 1985; Yoshida et al. 1999; Jikimoto et al. 2001; Lemarechal et al. 2006, 2007; Huili & Wan, 2013) could potently activate a TRP channel‐mediated current. This pattern of responses was recorded using both heterologous expression systems and synoviocytes isolated from patients that had been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. In this study, results from point mutation protocols revealed that specific cysteine residues in both TRPC5 and TRPC3 were the thioredoxin target(s).

Ligand‐induced increases in [Ca2+]i can represent an important first step in both evoked and constitutive cellular secretion cascades. In many types of endocrine cells, this increase in [Ca2+]i can then activate distinct classes of Cl− or K+ channels and thereby cause significant and long‐lasting changes in the membrane potential of the target cells. For example, a recent paper by Friebel et al. (2014) demonstrated a functional role for one specific type of Ca2+‐activated K+ channel in human synovial fibroblasts. This work, using primary cell cultures, identified the expression of the intermediate Ca2+‐activated K+ conductance KCa3.1 or KCNN4 (Berkefeld et al. 2010; Hu et al. 2012; Bi et al. 2013) in these FLS preparations. It also showed that modulation of the expression level of KCa3.1, as judged by both patch clamp recordings and antibody experiments, significantly altered the proliferation rates of these cells. In addition, Friebel et al. (2014) reported that a well‐known synovial fibroblast stimulant, transforming growth factor β1 (TGF‐β1) (cf. Pohlers et al. 2007), can significantly increase transcription, translation and expression of this particular K+ channel. In contrast, inhibition of this Ca2+‐activated K+ current resulted in reduced (i) proliferation and (ii) secretion of synovial fibroblast‐derived pro‐inflammatory mediators IL‐6, IL‐8 and MCP‐1. Since these synovial fibroblasts were obtained from donors that had a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) diagnosis, this K+ current, KCa3.1, could be a target for discovery of anti‐RA agents. This ion channel in T‐cells has been selected as a primary target for drug development to alleviate immune and autoimmune disorders (Cahalan & Chandy, 2009).

Integration of ion channel data

It is known that mechanical perturbations or ligand‐based stimulation of isolated synovial fibroblasts, either in situ or in cell culture settings, can consistently give rise to significant and relatively long lasting changes in [Ca2+]i. There is also evidence that these changes in [Ca2+]i can function as one of the second messengers for activation for a number of linked signalling cascades that modulate both evoked and constitutive release of hyaluronan, cytokines and growth factors. These substances strongly modulate for synovial fibroblast (RA) and articular joint function, both under baseline conditions and in disease states. However, more detailed information is needed regarding important aspects of these [Ca2+]i‐mediated signalling pathways. The trigger or initial source of the Ca2+ that is the electrophysiological signal for endoplasmic reticulum‐mediated intracellular Ca2+ release needs to be identified. Data obtained from mouse and human FLS preparations maintained in culture suggest that this initial Ca2+ influx arises from activation of TRP channels (Itoh et al. 2009) with the TRPV4/V1 and TRPC3/5 family being the strongest candidates (Kochukov et al. 2006; Engler et al. 2007). However, information is lacking concerning the voltage dependence of the Ca2+ entry pathway(s), and further insights into the cation selectivity, ligand sensitivity and pharmacological profile are needed. Moreover, in the well‐studied rabbit synoviocyte preparation (Large et al. 2010) L‐type Ca2+ channel expression and transmembrane Ca2+ currents have been identified.

By analogy with the known sequence of events in mammalian endothelial cells, even a very small Ca2+ or Na+ influx through e.g. TRPV4 channels (particularly if it is spatially localized to an immediate subplasma membrane space) can trigger a much larger Ca2+‐induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, the endoplasmic reticulum (Stathopulos et al. 2012; Sonkusare et al. 2012; Dunn et al. 2013). The resulting changes in Ca2+ can serve both the ‘AM and FM signalling modalities’ for Ca2+ in these FLS preparations as happens in many other cell types (Berridge et al. 2000; Farley & Sampath, 2011). Importantly, some aspects of the maintained or plastic signalling that is initiated by an increase in [Ca2+]i may not require maintained increases in [Ca2+]i.

Many important aspects of the Ca2+ signalling ‘tool kit’ in synovial fibroblasts remain to be elucidated or further defined (cf. Berridge et al. 2000). It is clear, however, that the initial transmembrane trigger signal (Ca2+ influx) is very small. However, it gives rise to a much larger Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum. As in other non‐excitable cells, the spatial localization of the Ca2+ entry ‘pathways’ on the plasma membrane offer possibilities for signal integration and amplification. Much of the Ca2+ that enters FLS cells is rapidly bound to intracellular buffers. This process can ‘shape’ the Ca2+ transient and also regulate (limit) its spatial profile. Calmodulin functions both as a rapid Ca2+ buffer and as a Ca2+ sensor. It can strongly activate downstream effectors and thus can result in changes in, e.g., ion channel function, metabolism or gene transcription. Some of these integrative processes are mediated by Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II and/or protein kinase C isoforms. Often the end result of a brief Ca2+ transient is a maintained cellular response. A well‐documented example of this is the Ca2+ influx plasticity in the mammalian brain (Ma et al. 2015). In the hippocampus (and elsewhere) details of the frequency dependence or repetitive nature of the changes in [Ca2+]i signalling are known to have differential effects on distinct pools of transcription factors, e.g. nuclear factor of activated T‐cells (NFAT) or intercellular latent gene regulatory proteins (NFκB) (Berridge et al. 2000).

In the case of FLS preparations, plausible candidates for the initial repetitive stimulus include: (i) cyclic changes in surface forces that are transduced by stretch‐activated channels, (ii) shear forces, and/or (iii) pulsatile release of ATP from other FLS cells, nerve endings, or emigrated neutrophils as a consequence of inflammation.

Increases in [Ca2+]i can also activate one or more Ca2+‐sensitive ion channels that are localized in the plasma membrane. A prominent feature of most recordings from the synovial fibroblast is the activation of BK or large conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ channels. As shown in Fig. 1, I KCa can give rise to a characteristic very ‘noisy’ outward current. It is activated at very positive (depolarized) membrane potentials and therefore is not of physiological significance. However, the hallmark feature of activation of these BK channels is a shift of their activation to more hyperpolarized membrane potentials as [Ca2+]i increases (Berkefeld et al. 2010; Hill et al. 2010). Moreover, this subset of Ca2+‐activated K+ channels has been shown to be sensitive to carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and a number of other physiological substances of interest within the framework of articular joint physiology (cf. Orio et al. 2002).

It is also apparent that a second and distinct Ca2+‐dependent K+ channel subset, KCa3.1, can be activated by the large increases in [Ca2+]i that are generated by, e.g., increases in ATP and/or acidification of pHo. Both of these take place in the setting of rheumatoid arthritis. This so‐called intermediate Ca2+‐activated K+ current exhibits completely different biophysical properties, pharmacology characteristics and cellular electrophysiological features from those for BK current (Gao et al. 2010; Bi et al. 2013; Friebel et al. 2014). Perhaps the most important difference is that these KCa3.1 channels can be strongly activated in the physiological range of membrane potentials. In the synovial fibroblast, and in immune cells (Cahalan & Chandy, 2009), these KCa3.1 channels can be blocked on their distinct pharmalogical profile. In T lymphocytes this KCa3.1 current is a primary target for intrinsic substances and new synthetic agents (pro‐drugs), some of which continue to be evaluated with promising results in preclinical or clinical settings (Wulff et al. 2000).

Some important information regarding the relationships among: (i) cellular electrophysiology, (ii) some aspects of [Ca2+]i‐mediated second messenger signalling pathways, and (iii) hyaluronan secretion in mammalian synovial fibroblasts is now available (Wann et al. 2009). However, additional work is needed before feasible drug‐sensitive targets that can be used for manipulating the function of synovial fibroblasts can be identified. Similarly, although some overall processes that regulate depolarization–secretion coupling are known, very important aspects of physiological and pharmacological regulation remain to be identified. One example is the requirement to understand more completely the interrelated effects of selective or collective (double hit) activation of the populations of distinct K+ channels that are expressed in these synovial fibroblasts. As has been shown in the T lymphocyte, and is illustrated in Fig. 2 B, when the intermediate conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ (I KCa3.1) is turned on, the target cell (T lymphocyte or FLS cell) hyperpolarizes markedly. This hyperpolarization can markedly augment Ca2+ entry through TRP channels or through other Ca2+‐selective pathways (cf. Cahalan & Chandy, 2009; cf. Funabashi et al. 2010).

Summary

Cell physiology/biophysics principles

Preliminary electrophysiological results from our laboratories (T.A.S., W.R.G.) indicate that at baseline (in the absence of paracrine, mechanical or autonomic nervous system stimulation), the synovial fibroblast typically exhibits an N‐shaped resting or background I–V relationship. The two most prominent transmembrane ionic currents that are responsible for this are: a time‐independent inwardly rectifying background K+ current that is activated at hyperpolarized membrane potentials (i.e. negative to approx. −40 mV), and a Ca2+‐activated K+ current (the large conductance, BKCa) that is activated at membrane potentials positive to approx. −10 mV. This N‐shaped background I–V has a number of functional consequences, including:

The prominent ‘flat region’ of this type of I–V curve results in significant technical challenges that limit accurate and/or reproducible measurement of membrane resting potential, E m (Wilson et al. 2011).

Since the levels of expression of both of these K+ currents are quite variable, these FLS cells (when studied individually), would be expected to show considerable ‘scatter’ in their E m values (see Large et al. 2010, Fig. 3).

Agonists or paracrine factors that ‘activate’ ligand‐gated currents when E m is in the high resistance (flat) region of the I–V curve, will have very significant effects on E m. This is because even quite small changes in E m can strongly modulate other essential cellular functions, such as resting [Ca2+]i levels and/or intercellular coupling.

The expression of inwardly rectifying K+ current not only regulates E m but can also modulate intercellular coupling. Accordingly, cell‐to‐cell communication in the FLS syncytium may be sensitive to very small changes in [K+]o (cf. Jantzi et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008; Anumonwo & Lopatin, 2010).

The effectiveness of compounds that activate most TRP channel isoforms would be expected to show a strong dependence on E m. The combination of the effects of shape of this N‐shaped ‘background’ I–V relationship and the fact that the reversal potential for many TRP channels is approximately −20 mV (i.e. within the flat region of the baseline I–V) combine to result in this sensitivity.

Finally, this N‐shaped I–V curve makes it likely that even very small intrinsic current sources, e.g. the electrogenic current due to the Na+/K+ pump, can alter E m. Accordingly, cell metabolism may be linked to the electrophysiological phenotype (cf. Jacquemet & Henriquez, 2008; Clark et al. 2010, 2011; Wilson et al. 2011) of FLS preparations.

Translational significance

Knowledge of the most significant electrophysiological principles that regulate the synovial fibroblast may provide novel insights into progressive rheumatoid arthritis (Imamura et al. 1998; cf. McInnes & Schett, 2011). It may also assist in identification of primary or ‘double hit’ drug development efforts (Oshima et al. 2000; Kunisch et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2008; Petroff et al. 2012) and contribute to rational decisions for pain management either following acute injury or in settings involving progressive deterioration of the articular joint.

By analogy with the work of Cahalan & Chandy (2009) on human T‐cells, the intermediate conductance Ca2+‐sensitive K+ channel KCa3.1 may be a viable drug target in the synovial fibroblast (cf. Friebel et al. 2014). It is also worth recalling that ion channel trafficking to the surface membrane may be altered in disease settings. In addition, it is now well known that a number of different ion channel α subunits, including those for KCa3.1, can strongly influence their parent cell phenotype and function (Friebel et al. 2014). Importantly, these effects can be significant even when these channel subunits are in their silent or non‐conducting states (Kazcmarek et al. 2006).

It is also worth noting that regulated secretion of other articular joint lubricants such as PGR4 or lubricin (Nugent‐Derfus et al. 2007) may be able to be enhanced by using electrophysiological insights/approaches. Hyperpolarizing FLS cells prior to their activation with, e.g., natural substances (ATP) (cf. Millward‐Sadler et al. 2004; Romanov et al. 2008), synthetic steroids (Ciurtin et al. 2010), or mechanical ‘oscillation’ may activate or enhance secretion of essential lubricant molecules, cytokines and/or ATP (Hu et al. 2012).

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

Financial support in the form of operating grants and salary awards for the authors is gratefully acknowledged: for W.R.G. an AHFMR Medical Scientist Award and CIHR Operating Grants; for T.A.S. a Canadian Arthritis Investigator Award, a Tier II Canadian Research Consulting Award and operating grants from the Canadian Arthritis Foundation and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). W.R.G. and T.A.S. received funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation for purchase of major equipment. F.B.S. received funding from the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Southern Alberta Transplant Program (specifically Dr R. Krawetz) for the supply of human synovial fibroblasts. Excellent technical support from Ms Colleen Kondo and administrative assistance from Ms Laura Styler are gratefully acknowledged.

Biographies

Robert B. Clark is a Research Professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology at the University of Calgary. His research interests are in cellular and membrane electrophysiology and biophysics of ion channels. Recently, he has studied the roles of ion channels in the regulation of the membrane potential of synovial fibroblasts, and its response to cytokines and other modulators.

Tannin A. Schmidt is an Associate Professor and Tier II Canada Research Chair in Biomaterials in the Faculty of Kinesiology, the Schulich School of Engineering at the University of Calgary. His research interests include biotribology, biomaterials, biomechanics, and biointerface science. He focuses on articular cartilage and ocular surface lubrication, orthopaedic and ophthalmic biomaterial development and characterization for treatment of diseases.

Frank B. Sachse is currently an Associate Professor in the Bioengineering Department, and an investigator at the Nora Eccles Cardiovascular Research and Training Institute of the University of Utah. His focus is on microscopic imaging and computational approaches to gain insights into the structure and function of heart.

Wayne Giles is currently Professor in the Faculties of Kinesiology and Medicine at the University of Calgary. He is an internationally recognised cardiac electrophysiologist.

References

- Abbruzzese J, Sachse FB, Tristani‐Firouzi M & Sanguinetti MC (2010). Modification of hERG1 channel gating by Cd2+ . J Gen Physiol 136, 203–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anumonwo JMB & Lopatin AN (2010). Cardiac strong inward rectifier potassium channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48, 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae C, Markin V, Suchyna T & Sachs F (2011). Modeling ion channels in the gigaseal. Biophys J 101, 2645–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartok B & Firestein GS (2010). Fibroblast‐like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev 233, 233–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ (2013). Characteristics of transient receptor potential canonical calcium‐permeable channels and their relevance to vascular physiology and disease. Circ J 77, 570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ & Sukumar P (2007). Channel regulation by extracellular redox protein. Channels 6, 400–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkefeld H, Fakler B & Schulte U (2010). Ca2+‐activated K+ channels: from protein complexes to function. Physiol Rev 90, 1437–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P & Bootman MD (2000). The versatility and universality of calcium signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 1, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi D, Toyama K, Lemaitre V, Takai J, Fan F, Jenkins DP, Wulff H, Gutterman DD, Park F & Miura H (2013). The intermediate conductance calcium‐activated potassium channel KCa3.1 regulates vascular smooth cell proliferation via controlling calcium‐dependent signaling. J Biol Chem 288, 15843–15853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR & Slayman CL (1983). KCl leakage from microelectrodes and its impact on the membrane parameters of a nonexcitable cell. J Membr Biol 72, 223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottini N & Firestein GS (2012). Duality of fibroblast‐like synoviocytes in RA: passive responders and imprinted aggressors. Nat Rev Rheumatol 9, 24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan MD & Chandy GK (2009). The functional network of ion channels in T lymphocytes. Immunol Rev 231, 59–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton L, Ohya S, Freed D, George E, Drobic V, Shibukawa Y, MacCannell KA, Imaizumi Y, Clark RB, Dixon IM & Giles WR (2005). K+ currents regulate the resting membrane potential, proliferation, and contractile responses in ventricular fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288, H2931–H2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen BN, Kochukov M, McNearney A, Taglialatela G & Westlund KN (2005). Proton‐sensing G protein‐coupled receptor mobilizes calcium in human synovial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289, C601–C608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciurtin C, Majeed Y, Naylor J, Sukumar P, English AA, Emery P & Beech DJ (2010). TRPM3 channel stimulated by pregnenolone sulphate in synovial fibroblasts and negatively coupled to hyaluronan. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11, 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RB, Hatano N, Kondo C, Belke DD, Brown BS, Kumar S, Votta BJ & Giles WR (2010). Voltage‐gated K+ currents in mouse articular chondrocytes regulate membrane potential. Channels 4, 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RB, Kondo C & Giles WR (2011). Two‐pore K+ channels contribute to membrane potential of isolated human articular chondrocytes. J Physiol 589, 5071–5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KM, Hill‐Eubanks DC, Liedtke WB & Nelson MT (2013). TRPV4 channels stimulate Ca2+‐induced Ca2+ release in astrocytic endfeet and amplify neurovascular coupling responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 6157–6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler A, Aeschlimann A, Simmen BR, Michael BA, Gay RE, Gay S & Sprott H (2007). Expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) in synovial fibroblasts from patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 359, 884–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley RA & Sampath AP (2011). Perspectives on information coding in mammalian sensory physiology. J Gen Physiol 138, 281–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann R (2012). Novel small‐molecular therapeutics for rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 24, 335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friebel K, Schönherr R, Kinne RW & Kunisch E (2014). Functional role of the KCa3.1 potassium channel in synovial fibroblasts from rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Cell Physiol 230, 1677–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabashi K, Ohya S, Yamamura H, Hatano N, Muraki K, Giles W & Imaizumi Y (2010). Accelerated Ca2+ entry by membrane hyperpolarization due to Ca2+‐activated K+ channel activation in response to histamine in chondrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298, C786–C797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Hanley PJ, Rinné S, Zuzarte M & Daut J (2010). Calcium‐activated K+ channel (KCa3.1) activity during Ca2+ store depletion and store‐operated Ca2+ entry in human macrophages. Cell Calcium 48, 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MA, Yang Y, Ella SR, Davis MJ & Braun AP (2010). Large conductance, Ca2+‐activated K+ channels (BKCa) and arteriolar myogenic signaling. FEBS Lett 584, 2033–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A (1985). Thioredoxin. Annu Rev Biochem 54, 231–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan FT & Aldrich RW (2002). Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel operating in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J Gen Physiol 120, 267–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Laragione T, Sun L, Koshy S, Jones KR, Ismailov II, Yotnda P, Horrigan FT, Gulko PS & Beeton C (2012). KCa1.1 potassium channels regulate key proinflammatory and invasive properties of fibroblast‐like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. J Biol Chem 287, 4014–4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber LC, Distler O, Tarner I, Gay RE & Pap T (2006). Synovial fibroblasts: key players in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45, 669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui AY, McCarty WJ, Masuda K, Firestein GS & Sah RL (2012). A systems biology approach to synovial joint lubrication in health, injury, and disease. Rev Syst Biol Med 4, 15–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huili L & Wan A (2013). Apoptosis of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast‐like synoviocytes: possible roles of nitiric oxide and the thioredoxin 1. Mediators of Inflammation https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/953462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura F, Anon H, Hasunuma T, Sumida T, Tateishi H, Maruo S & Nishioka K (1998). Monoclonal expansion of synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 41, 1979–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immke DC & McCleskey EW (2001). Lactate enhances the acid‐sensing Na+ channel on ischemia‐sensing neurons. Nat Neurosci 4, 869–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram KR, Wann AKT, Angel K, Coleman PJ & Levick JR (2008). Cyclic movement stimulates hyaluronan secretion into the synovial cavity of rabbit joints. J Physiol 586, 1715–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Hatano N, Hayashi H, Onozaki K, Miyazawa K & Muraki K (2009). An environmental sensor, TRPV4 is a novel regulator of intracellular Ca2+ in human synoviocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297, C1082–C1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer V, Maxhari R & Winslow RL (2004). A computational model of the human left‐ventricular epicardial myocyte. Biophys J 87, 1507–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemet V & Henriquez CS (2008). Loading effect of fibroblast‐myocyte coupling on resting potential, impulse propagation and repolarization: insights from a microstructure model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294, H2040–H2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzi MC, Brett SE, Jackson WF, Corteling R, Vigmond EJ & Welsh DG (2006). Inward rectifying potassium channels facilitate cell‐to‐cell communication in hamster retractor muscle feed arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291, H1319–H1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jikimoto T, Nishikubo Y, Koshiba M, Kanagawa S, Morinobu S, Morinobu A, Saura R, Mizuno K, Kondo S, Toyokuni S, Nakamura H, Yodoi J & Kumugai S (2001). Thioredoxin as a biomarker for oxidative stress in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Immunol 38, 765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez M, Filer A & Buckley CD (2012). Fibroblasts as therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis and cancer. Swiss Med Wkly 142, w13529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek LK (2006). Non‐conducting functions of voltage‐gated ion channels. Nature 7, 761–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MM, McGlashan SR, Garcia M, Jensen CG & Poole CA (2009). Articular chondrocytes express connexin 43 hemichannels and P2 receptors – a putative mechanoreceptor complex involving the primary cilium? J Anat 214, 275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochukov MY, McNearney TA, Fu Y & Westlund KN (2006). Thermosensitive TRP ion channels mediate cytosolic calcium response in human synoviocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292, C424–C432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolker SJ, Walder RY, Usachev Y, Hillman J, Boyle DL, Firestein GS & Sluka KA (2010). Acid‐sensing ion channel 3 expressed in type B synoviocytes and chondrocytes modulates hyaluronan expression and release. Ann Rheum Dis 69, 903–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolomytkin OV, Marino AA, Sadasivan KK, Wolf RE & Albright JA (1997). Interleukin‐1β switches electrophysiological states of synovial fibroblasts. Am J Physiol 273, R1822–R1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolomytkin OV, Marino AA, Sadasivan KK, Wolf RE & Albright JA (1999). Intracellular signaling mechanisms of interleukin‐1β in synovial fibroblasts. Am J Physiol 276, C9–C15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisch E, Gandesiri M, Fuhrmann R, Roth A, Winter R & Kinne RW (2007). Predominant activation of MAP kinases and pro‐destructive/pro‐inflammatory features by TNF α in early‐passage synovial fibroblasts via TNF receptor‐1: failure of p38 inhibition to suppress matrix metalloproteinase‐1 in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 66, 1043–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large RJ, Hollywood MA, Sergeant GP, Thornbury KD, Bourke S, Levick JR & McHale NG (2010). Ionic currents in intimal cultured synoviocytes from the rabbit. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299, C1180–C1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefèvre S, Knedla A, Tennie C, Kampann A, Wunrau C, Dinser R, Korb A, Schnäker EM, Tarner IH, Robbins PD, Evans CH, Stürz H, Steinmeyer J, Gay S, Schölmerich J, Pap T, Müller‐Ladner U & Neumann E (2009). Synovial fibroblasts spread rheumatoid arthritis to unaffected joints. Nat Med 15, 1414–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemarechal H, Allanore Y, Chenevier‐Gobeaux C, Ekindjian OG, Kahan A & Borderie D (2006). High redox thioredoxin but low thioredoxin reductase activities in the serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chim Acta 367, 156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemarechal H, Anract P, Beaudeux JL, Bonnefont‐Rousselot D, Ekindijan OG & Borderie D (2007). Impairment of thioredoxin reductase activity by oxidative stress in human rheumatoid synoviocytes. Free Radic Res 41, 688–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Li B & Tsien RW (2015). Distinct roles of multiple isoforms of CaMKII in signaling to the nucleus. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853, 1953–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, IB & Schett, G (2011). The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 365, 2205–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millward‐Sadler SJ, Wright MO, Flatman PW & Salter DM (2004). ATP in the mechanotransduction pathway of normal human chondrocytes. Biorheology 41, 567–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momberger TS, Levick JR & Mason RM (2006). Mechanosensitive synoviocytes: a Ca2+–PKCα–MAP kinase pathway contributes to stretch‐induced hyaluronan synthesis in vitro. Matrix Biol 25, 306–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E (1992). Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. Methods Enzymol 207, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niger C, Howell FD & Stains JP (2010). Interleukin‐1β increases gap junctional communication among synovial fibroblasts via the extracellular signal regulated kinase pathway. Biol Cell 102, 37–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent‐Derfus GE, Takara T, O'Neill JK, Cahill SB, Görtz S, Pont T, Inoue H, Aneloski NM, Wang WW, Vega KI, Klein TJ, Hsieh‐Bonassera ND, Bae WC, Burke JD, Bugbee WD & Sah RL (2007). Continuous passive motion applied to whole joint stimulates chondrocyte biosynthesis of PRG4. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15, 566–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio P, Rojas P, Ferreira G & Latorre R (2002). New disguises for an old channel: MaxiK channel β‐subunits. News Physiol Sci 17, 156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima S, Mima T, Sasai M, Nishioka K, Shimizu M, Murata N, Yoshikawa H, Nakanishi K, Suemura M, McCloskey RV, Kishimoto T & Saeki Y (2000). Tumour necrosis factor α (TNF‐α) interferes with Fas‐mediated apoptotic cell death on rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synovial cells: a possible mechanism of rheumatoid synovial hyperplasia and a clinical benefit of ANTI‐TNF‐α therapy for RA. Cytokine 3, 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroff E, Snitsarev V, Gong H & Abboud FM (2012). Acid sensing ion channels regulate neuronal excitability by inhibiting BK potassium channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 426, 511–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlers D, Beyer A, Koczan D, Wilhelm T, Thiesen HJ & Kinne RW (2007). Constitutive upregulation of the transforming growth factor‐β pathway in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Res Ther 9, R59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattner BJ, Sciore P, Ou Y, Van der Hoorn FA & Lo IKY (2010). Primary cilia in fibroblast‐like type B synoviocytes lie within a cilium pit: a site of endocytosis. Histol Histopathol 25, 865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Rogachevskaja OA, Khokhlov AA & Kolesnikov SS (2008). Voltage dependence of ATP secretion in mammalian taste cells. J Gen Physiol 132, 731–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PD, Brett SE, Luykenaar KD, Sandow SL, Marrelli SP, Vigmond EJ & Welsh DG (2008). Kir channels function as electrical amplifiers in rat ventricular smooth muscle. J Physiol 586, 1147–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkusare SK, Bonev AD, Ledoux J, Liedtke W, Kotlikoff MI, Heppner TJ, Hill‐Eubanks DC & Nelson MT (2012). Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science 336, 597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopulos PB, Seo M, Enomoto M, Amador FJ, Ishiyama N & Ikura M (2012). Themes and variations in ER/SR calcium release channels: structure and function. Physiology (Bethesda) 27, 331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriens J, Watanabe H, Janssens A, Droogmans G, Voets T & Nilius B (2004). Cell swelling, heat, and chemical agonists use distinct pathways for the activation of the cation channel TRPV4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wann AKT, Ingram KR, Coleman PJ, McHale N & Levick JR (2009). Mechanosensitive hyaluronan secretion: stimulus–response curves and role of transcription–translation–translocation in rabbit joints. Exp Physiol 94, 350–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Clark RB, Banderali U & Giles WR (2011). Measurement of the membrane potential in small cells using patch clamp methods. Channels (Austin) 5, 530–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff H, Miller MJ, Hansel W, Grissmer S, Cahalan MD & Chandy KG (2000). Design of a potent and selective inhibitor of the intermediate‐conductance Ca2+‐activated K+ channel, I KCa1: a potential immunosuppresant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97, 8151–8156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SZ, Sukumar P, Zeng F, Li J, Jairman A, English A, Naylor J, Ciurtin C, Majeed Y, Milligan CJ, Bahnasi YM, Al‐Shawaf E, Porter KE, Jiang L, Emery P, Sivaprasadarao A & Beech DJ (2008). TRPC channel activation by extracelullar thioredoxin. Nature 451, 69–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Katoh T, Tetsuka T, Uno K, Matsui N & Okamoto T (1999). Involvement of thioredoxin in rheumatoid arthritis: its costimulatory roles in the TNF‐α‐induced production of IL‐6 and IL‐8 from cultured synovial fibroblasts. J Immunol 163, 351–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Fernandes MJ, Turgeon M, Tancrède S, Battista JD, Poubelle PE & Bourgoin SG (2008). Specific and overlapping sphingosine‐1‐phosphate receptor functions in human synoviocytes: impact of TNF‐α. J Lipid Res 49, 2323–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann T, Kunisch E, Pfeiffer R, Hirth A, Stahl HD, Sack U, Laube A, Liesaus E, Roth A, Palombo‐Kinne E, Emmrich F & Kinne RW (2001). Isolation and characterization of rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts from primary culture – primary culture cells markedly differ from fourth‐passage cells. Arthritis Res 3, 72–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]