Abstract

Feeding conditions can impact sensitivity to drugs acting on dopamine receptors; less is known about the impact of feeding conditions on the effects of drugs acting on serotonin (5-HT) receptors. This study examined the effects of feeding condition on sensitivity to the direct-acting 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylphenyl)-2-aminopropane (DOM; 0.1–3.2 mg/kg) and the direct-acting dopamineD3/D2 receptor agonist quinpirole (0.0032–0.32 mg/kg). Male Sprague-Dawley rats had free access (11 weeks) followed by restricted access (6 weeks) to high (34.3%, n = 8) fat or standard (5.7% fat; n = 7) chow. Rats eating high fat chow became insulin resistant and gained more weight than rats eating standard chow. Free access to high fat chow did not alter sensitivity to DOM-induced head twitch but increased sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning. Restricting access to high fat or standard chow shifted the DOM-induced head twitch dose-response curve to the right and shifted the quinpirole-induced yawning dose-response curve downward in both groups of rats. Some drugs of abuse and many therapeutic drugs act on 5-HT and dopamine systems; these results demonstrate that feeding condition impacts sensitivity to drugs acting on these systems, thereby possibly impacting vulnerability to abuse as well as therapeutic effectiveness of drugs.

Keywords: serotonin receptor, dopamine receptor, head twitch, yawning, high-fat food, food restriction, DOM, quinpirole

Introduction

A number of factors can impact sensitivity to the effects of drugs acting on monoamine systems, including age (Kostrzewa et al., 1992), sex (Baladi et al., 2011a; Baladi et al., 2012), drug history (Collins and Woods 2007; Nader and Mach 1996), and feeding condition (Baladi et al., 2012; Li et al., 2009). Drugs acting directly (e.g. antipsychotics) or indirectly (e.g. stimulants for attention deficit disorders) on dopamine receptors are used therapeutically (Abi-Dargham and Laruelle 2005) and dopamine systems are an important site of action for several drugs of abuse (e.g. cocaine). Both the type and the quantity of food can significantly impact sensitivity to the behavioral effects of drugs acting on dopamine systems (see Baladi et al., 2012 for a review). For example, food restriction eliminates yawning produced by the direct-acting dopamine receptor agonist quinpirole (Baladi and France 2009; Collins et al., 2008). In contrast, eating high fat chow or drinking sucrose enhances quinpirole-induced yawning, shifting the inverted U-shaped yawning dose-response curve upward and leftward (Baladi et al.. 2010; Baladi et al. 2011b). Feeding conditions can also affect the actions of indirect-acting dopamine receptor agonists, including cocaine and methamphetamine (Baladi et al.. 2011a; McGuire et al., 2011; see Baladi et al.. 2012 for a review).

It is well established that serotonin (5-HT) systems regulate food intake (De Vry and Schreiber 2000); conversely, it appears as though feeding conditions can impact sensitivity to the effects of drugs acting on 5-HT systems (Li and France 2008; Li et al.. 2009; Slaiman 1989). However, much less is known about the impact of feeding condition on the effects of drugs acting on 5-HT systems, compared with drugs acting on dopamine systems. For example, direct-acting 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonists induce a characteristic head twitch response (irregularly occurring horizontal head movement, resembling a strong pinna reflex; Corne et al.. 1963; Li and France 2008) in mice and rats (Berendsen and Broekkamp, 1990; Darmani et al.. 1990; Fantegrossi et al.. 2008; Li and France 2008). Restricting food intake in rats (10 g/day; Li and France 2008) significantly decreases head twitching induced by the direct-acting 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist (±)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine hydrochloride (DOI). Food restriction also decreases the effectiveness of the indirect-acting 5-HT receptor agonist escitalopram (selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitor [SSRI]) to reduce immobility in a forced swimming test in rats (France et al. 2009), perhaps related to the decreased effectiveness of SSRIs among depressed individuals with eating disorders (Barbarich et al.. 2004; Kaye et al.. 1998). Eating high fat chow increases sensitivity of rats to 5-HT1A receptor agonist [(+)-8-hydroxy-2-(dipropylamino)tetralin hydrobromide (8-OH-DPAT)]-induced lower lip retraction (Li et al.. 2011), although it is not known whether eating high fat chow impacts sensitivity to drugs acting directly at other 5-HT receptors. Eating high fat chow increased 5-HT2A/2C binding density in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus and anterior olfactory nucleus of mice (Huang et al., 2004), although it is not clear whether eating high fat chow alters sensitivity to drugs acting directly on 5-HT2A/2C receptors. Among the many 5-HT receptor subtypes, 5-HT2A receptors are of particular interest because they are implicated in a several psychological disorders (e.g., depression; Celada et al., 2004; schizophrenia; Shimizu et al., 2013) and in drug abuse (do Prado-Lima et al., 2004; Wrzosek et al., 2012).

The mechanism(s) that mediates changes in sensitivity to the effects of drugs acting on monoamine systems under different feeding conditions is not well established, although it appears as though insulin and insulin-signaling pathways might be involved. Insulin deficiency (e.g., streptozotocin) alters sensitivity to 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylphenyl)-2-aminopropane- (DOM)-induced hypothermia (Li et al.. 2009) and the effects of 8-OH-DPAT in the tail-suspension test (Miyata et al., 2004) without affecting sensitivity to DOI-induced wet-dog shakes (Amano et al.. 2007). Some psychiatric disorders that are thought to be associated with abnormalities in 5-HT functioning (e.g. depression) are significantly more prevalent among diabetic individuals (Anderson et al.. 2011; Barnard et al.. 2006; De Groot et al., 2001). Thus, insulin status covaries with and might be causally related to psychopathology and to diet-induced changes in sensitivity to drugs. One feeding condition that significantly alters insulin status is consumption of foods high in fat or sugar. For example, rats become insulin resistant after as little as 2 weeks of eating high fat chow and that change in insulin status is accompanied by significant changes in the sensitivity to drug acting on dopamine systems (Baladi et al.. 2011a). It is not known whether eating high fat chow alters sensitivity to the behavioral effects of drugs acting directly on 5-HT2A/2C receptors.

To further characterize the relationship among feeding conditions, insulin sensitivity, and drugs acting directly at 5-HT2A/2C receptors, this study examined whether eating high fat chow or food restriction alters the sensitivity of rats to effects of the direct-acting 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist DOM. Because it is well established that food restriction or eating high fat chow alters sensitivity to drugs acting directly at dopamine receptors, the direct-acting dopamine receptor agonist quinpirole was also examined in order to confirm that feeding conditions had an effect on monoamine systems.

Methods

Subjects

Fifteen male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA), weighing 250–300 g upon arrival, were housed individually in an environmentally controlled room (24±1°C, 50±10% relative humidity) under a 12:12 hr light/dark cycle (light period 0700–1900 hr). The study was conducted in two different cohorts of rats. In one cohort, 3 rats ate standard chow and 4 ate high fat chow; in a second cohort, 4 ate standard chow and 4 ate high fat chow. All rats had free access to food and water in the home cage except as indicated below. Animals were maintained and experiments were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and with the 2011 Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, the National Research Council, and the National Academy of Sciences).

Feeding conditions

Testing (DOM or quinpirole) occurred once every other week at 0900 hr throughout the experiment (see Fig 1). One or two individually housed rats (in separate test chambers) were assessed each day, 4 days per week (7 rats were observed one week and 8 the following week). During the first 6 weeks of the experiment, all subjects had free access to standard laboratory chow (Harlan Teklad 7912); two dose-response curves were determined for DOM-induced head twitch (weeks 3 and 5 for cohort 1 and weeks 1 and 5 for cohort 2) and one dose-response curve was determined for quinpirole-induced yawning (week 1 for cohort 1 and week 3 for cohort 2). Quinpirole and DOM were tested in different order between cohorts to monitor whether testing with one drug impacted results obtained with a second drug. Because there were no order effects, data are collapsed across the two cohorts. After 6 weeks, subjects were ranked based on the total number of DOM-induced head twitches and, subsequently, assigned to different feeding conditions (groups) such that the average number of DOM-induced head twitches was not different between groups. From week 7 through week 17, rats had free access to either standard laboratory chow (n = 7) or high fat chow (n = 8) during which time three dose-response curves were determined for DOM (weeks 8, 10, and 14) and two for quinpirole (weeks 12 and 16). From week 18 through week 23, rats ate the same type of chow they ate during weeks 7–17; however, the amount of chow provided was restricted (initially to 10 g/day for rats eating standard chow and 6 g/day for rats eating high fat chow) until body weight decreased by 20% of their individual body weights at week 17. Thereafter, the amount of food provided was adjusted daily so that body weight was maintained at the 20% reduced value. During food restriction, two dose-response curves were determined for DOM (weeks 19 and 21) and one for quinpirole (week 23). All subjects were fed daily at 1400 hours. The nutritional content of the standard chow (Harlan Teklad 7912) was 5.7% fat, 44.3% carbohydrate, and 19.9% protein (by weight) with a calculated gross energy content of 4.1 kcal/g. The high-fat chow (Harlan Teklad 06414) contained 34.3% fat, 27.3% carbohydrate, and 23.5% protein (by weight), with a calculated energy content of 5.1 kcal/g.

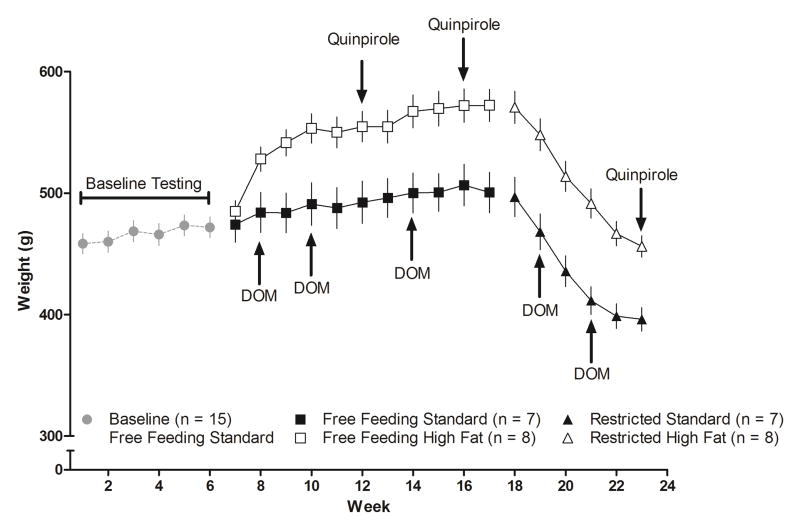

Fig 1.

Body weight of rats plotted as a function of week in the study: during weeks 1–6 all 15 rats had free access to standard chow; during weeks 7–17 rats had free access to either standard (n = 7) or high fat (n = 8) chow; and during weeks 18–23 rats had restricted access to either standard or high fat chow such that body weight decreased by 20% of the respective body weights of individuals at week 17. Tests with DOM and quinpirole are indicated on weeks during which they occurred. Ordinate: body weight in g. Abscissa: week in study.

Head Twitch

Head twitch was defined as an irregularly occurring horizontal head movement, resembling a strong pinna reflex (Corne et al.. 1963; Li and France 2008). On the day of testing, rats were transferred from a clear plastic home cage to a test cage (the home and test cages were identical with the exception that no food, water or bedding was present in the test cage) and allowed to habituate for 15 min. Head twitch experiments were conducted at the same time each test day (0900 hr) by an independent observer blind to the treatment. Head twitch was assessed after injection of vehicle followed by injection of increasing doses of DOM (0.1–3.2 mg/kg, i.p.) administered every 25 min using a cumulative dosing procedure. Beginning 5 min after each injection, the total number of head twitches observed for 20 min was recorded. A total of 7 dose-response curves were determined for DOM-induced head twitch.

Yawning

Yawning was defined as an opening and closing of the mouth (~1 s) such that the lower incisors were completely visible (Baladi and France 2009; Sevak et al.. 2008). On the day of testing, rats were transferred to test cages and allowed to habituate for 15 min. Yawning experiments were also conducted at the same time each day (0900 hr). Yawning was assessed after injection of vehicle followed by injection of increasing doses of quinpirole (0.0032–0.32 mg/kg, i.p.) administered every 30 min using a cumulative dosing procedure. Beginning 20 min after each injection, the total number of yawns observed for 10 min was recorded. A total of 4 dose–response curves were determined for quinpirole-induced yawning.

Body temperature

Rectal body temperature was measured in a temperature controlled room (24 ± 1°C and 50 ± 10% relative humidity) by inserting a lubricated thermal probe attached to a thermometer 3 cm into the rectum. Animals were adapted to the procedure by measuring body temperature on multiple occasions before assignment to a feeding condition. During head twitch experiments, body temperature was measured after completion of each 20-min observation period and prior to the next injection. During yawning experiments, body temperature was measured upon completion of each 10-min observation period for yawning and prior to the next injection.

Insulin Sensitivity

Beginning in week 7 (i.e. when animals had free access to either standard or high fat chow), insulin sensitivity was assessed every other week for 6 weeks (the same day of the week and the same time [0900 hr]) on days when rats did not receive drug. A small sample of blood was collected from the tip of the tail following a small incision (using a sterile scalpel blade) then expressed on a blood-glucose test trip. Glucose values were measured with a commercially available glucose meter (Accu-Chek Aviva; CVS). Glucose was measured prior to as well as 15, 30, 45, and 75 min after an i.p. injection of 0.75 U/kg insulin.

Data analyses

Results are expressed as the average (± SEM) body weight in g, number of head twitches during a 20-min observation period, number of yawns during a 10-min observation period, and body temperature in °C, plotted as a function of week (body weight) or dose. A two-way (dose and feeding condition) repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests, was used to evaluate maximum effect and area under the curve (AUC) for head twitches and yawning (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The dose producing the maximum number of head twitches or maximum number of yawns was determined for each rat, and for each dose-response curve. These doses were log transformed for individual subjects and evaluated using a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc analyses. Body temperature was analyzed using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with feeding condition and dose as factors. For each group of rats (standard chow and high fat chow) a paired t-test was used to examine changes in blood glucose concentration after administration of insulin (Durham and Truett 2006; see Baladi et al., 2011a for a discussion). For all tests, P<0.05.

Drugs

Quinpirole dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and (±) DOM hydrochloride (NIDA Research Technology Branch, Rockville, MD, USA) were dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline and administered i.p. Insulin (protamine zinc recombinant human insulin; Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc., St. Joseph, MO) was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline and injected i.p. All injection volumes were 1 ml/kg body weight.

Results

Body Weight

At the beginning of the experiment rats (n = 15) weighed (mean ± SEM) 451.2 ± 8.3 g (Fig 1); after 6 weeks of free access to standard chow the average body weight increased to 473.0 ± 8.8 g. During weeks 7–17, rats (n = 7) eating standard chow continued to gain weight (500.0 ± 16.1 g in week 17). The remaining 8 rats ate high fat chow beginning in week 7 and they also continued to gain weight (577.8 ± 14.3 g in week 17). Beginning in week 18 access to chow (standard or high fat) was restricted for all rats resulting in a 20% loss in body weight for both groups in week 23: to 397.9 ± 10.1 g for rats with restricted access to standard chow and to 459.9 ± 8.3 g for rats with restricted access to high fat chow (Fig 1).

DOM: Head Twitch and Body Temperature

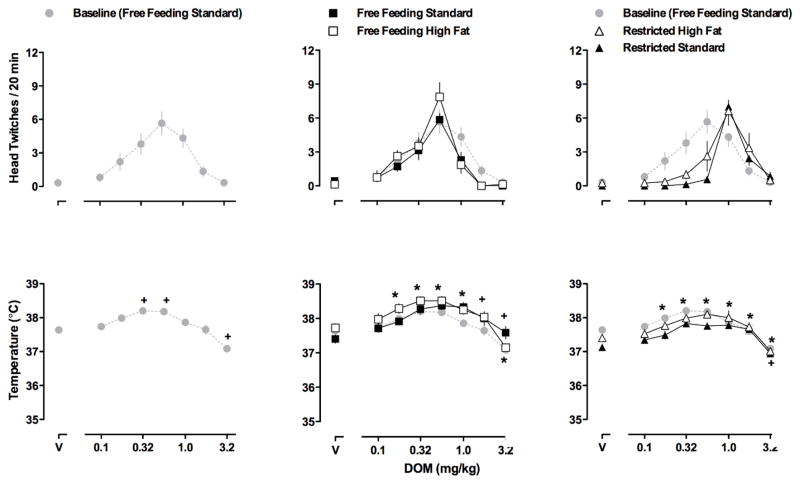

With increasing doses of DOM, head twitching increased then decreased, generating an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve in rats with free access to standard chow (upper left and middle panels, Fig 2). The maximum number of head twitches produced by DOM was not significantly different between rats eating standard chow and those eating high fat chow (e.g., week 14; upper middle panel, Fig 2). Moreover, food restriction did not significantly affect the maximum number of DOM-induced head twitches (upper right panel, Fig 2). AUC for DOM-induced head twitches was not different between groups for any test (Table 1). Although the maximum number of head twitches produced by DOM was not significantly different between rats eating standard chow and those eating high fat chow, one-way repeated-measures ANOVAs revealed that the dose producing the maximum number of head twitches was significantly larger for rats eating standard chow [F (6,48) = 14.75, p<0.01] and for rats eating high fat chow [F (6,55) = 5.945, p<0.01] when access to food was restricted (upper right panel, Fig 2). Under control conditions (upper left panel, Fig 2) and when rats had free access to either standard or high fat chow (upper middle panel, Fig 2), the dose of DOM that produced the most head twitches in individual rats was either 0.32 or 0.56 mg/kg. In contrast, when rats had restricted access to either standard or high fat chow (upper right panel, Fig 2) the dose of DOM that produced the most head twitches in individual rats was either 1.0 or 1.78 mg/kg and a dose of 0.32 mg/kg of DOM produced very few head twitches.

Fig 2.

Dose-response curves for DOM-induced head twitch (upper panels) and DOM-induced changes in body temperature (lower panels) during week 5 (left panels) when all 15 rats had free access to standard chow, during week 14 (middle panels) when rats continued to have free access to standard chow (n = 7, closed squares) or had free access to high fat chow (n = 8, open squares), and during week 21 (right panels) when rats had restricted access to either standard (n = 7, closed triangles) or high fat (n = 8, open triangles) chow. The same (control/baseline) data indicated by gray circles are repeated in all three panels. Ordinates: upper panels, mean (± SEM) head twitches per 20 min; lower panels, body temperature in °C. Abscissae: dose of DOM in mg/kg body weight (V = vehicle). Significance symbols refer to differences in body temperature only. + = Significantly different from the respective vehicle (control) value for rats eating standard chow. * = Significantly different from the respective vehicle (control) value for rats eating high fat chow.

Table 1.

Area under the curve (AUC) ± SEM values for DOM-induced head twitches in rats eating high fat or standard chow during baseline tests (1 and 2) and throughout the 21-week study (see Fig 1 for details).

| Test | High Fat Chow | Standard Chow |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline 1 | 5.05 (0.45) | 3.82 (0.75) |

| Baseline 2 | 4.84 (0.29) | 4.39 (0.75) |

| Week | ||

| 8 | 2.45 (0.13) | 2.61 (0.20) |

| 10 | 1.66 (0.07) | 2.32 (0.34) |

| 14 | 4.08 (0.14) | 3.34 (0.44) |

| 19 | 3.30 (0.17) | 3.20 (0.31) |

| 21 | 3.59 (0.18) | 2.64 (0.21) |

DOM dose-dependently increased then decreased body temperature and did so in a similar manner throughout the study in rats eating standard chow and in rats eating high fat chow. Moreover, food restriction did not alter these effects of DOM on body temperature in either group of rats (lower right panel, Fig 2).

Quinpirole: Yawning and Body Temperature

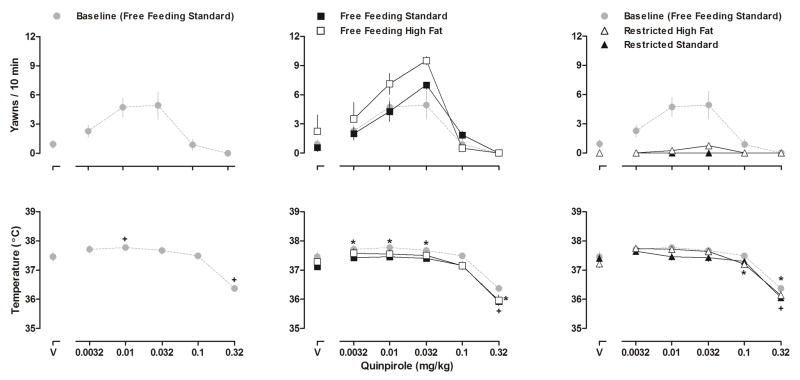

With increasing doses of quinpirole, yawning increased then decreased, generating an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve in rats with free access to standard chow (upper left and middle panels, Fig 3). Quinpirole-induced yawning did not change significantly in rats with free access to standard chow; however, quinpirole-induced yawning increased significantly in rats eating high fat chow (e.g., week 16; upper middle panel, Fig 3) as indicated by both an increase in the maximum number of yawns elicited by quinpirole and a significant increase in AUC of the quinpirole dose-response curve compared to baseline conditions using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA (data not shown [F (3,21) = 36.49, p<0.01). A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that restricting access to chow (standard or high fat) significantly attenuated quinpirole-induced yawning in all rats with few or no yawns observed after administration of quinpirole up to a dose of 0.32 mg/kg (i.e., week 23; upper right panel, Fig 3 [F (3,39) = 47.89, p<0.01]).

Fig 3.

Dose-response curves for quinpirole-induced yawning (upper panels) and quinpirole-induced changes in body temperature (lower panels) in week 1 (cohort 1) or week 3 (cohort 2) when all 15 rats had free access to standard chow (left panels), during week 16 (middle panels) when rats continued to have free access to standard chow (n = 7, closed squares) or had free access to high fat chow (n = 8, open squares), and during week 23 (right panels) when rats had restricted access to either standard (n = 7, closed triangles) or high fat (n = 8, open triangles) chow. The same (control/baseline) data indicated by gray circles are repeated in all three panels. Ordinates: upper panels, mean (±SEM) yawns per 10 min; lower panels, body temperature in °C. Abscissae: dose of quinpirole in mg/kg body weight (V = vehicle). Significance symbols refer to differences in body temperature only. + = Significantly different from the respective vehicle (control) value for rats eating standard chow. * = Significantly different from the respective vehicle (control) value for rats eating high fat chow.

Quinpirole dose-dependently decreased body temperature in all rats and this effect was not significantly different between rats eating standard chow and rats eating high fat chow (lower left and center panels, Fig 3). Although food restriction nearly eliminated the effect of quinpirole in producing yawning, food restriction did not significantly alter the hypothermic effects of quinpirole (compare upper and lower right panels, Fig 3).

Insulin Sensitivity

After two weeks of eating high fat chow, baseline glucose concentration was slightly, although significantly [t(13) = 3.126, p<0.01], higher in rats eating high fat chow (116.0 ± 2.6 mg/dL) as compared with rats eating standard chow (104.3 ± 2.4 mg/dL). Administration of 0.75 U/kg of insulin significantly decreased blood glucose concentration in rats eating standard chow (93.6 ± 3.7 mg/dL, [t (6) = 2.952, p <0.05]) but not in rats eating high fat chow (119.5 ± 4.0 mg/dL, [t (7) = 0.8225]). Maximal decreases in blood glucose concentration occurred 30 min after administration on insulin in rats eating standard chow.

Discussion

It is well established that feeding conditions (amount and type of food) can modify, both quantitatively (Baladi et al., 2012b) and qualitatively (e.g., Baladi and France, 2010), the effects of drugs acting on monoaminergic systems. The impact of feeding conditions on the effects of drugs acting on dopamine systems has been studied most extensively, although several studies examined the impact of feeding conditions on the effects of drugs acting on 5-HT systems. For example, food restriction decreases sensitivity to the effects of direct-acting 5-HT1A receptor agonists and 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonists whereas eating high fat chow increases sensitivity to the effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists (Li and France, 2008; Li et al., 2009; Slaiman, 1989).

Some 5-HT receptor agonists cause head twitching in rodents; the dose-response curve for head twitching is an inverted U-shape with the ascending limb of the curve mediated by 5-HT2A receptors and the descending limb mediated by 5-HT2C receptors (Fantegrossi et al.. 2010; Vickers et al.. 2001; see Canal and Morgan, 2012 for a review). The current study examined the impact of eating high fat chow on the sensitivity of rats to the effects of the direct-acting 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist DOM. With increasing doses of DOM, head twitching increased then decreased, generating an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve. At doses slightly larger than those maximally increasing head twitching, DOM also significantly decreased body temperature. Neither DOM-induced head twitching nor DOM-induced changes in body temperature was significantly different between rats eating standard chow and rats eating high fat chow, despite the fact that rats eating high fat chow gained significantly more body weight, as compared with rats eating standard chow, and they were insulin resistant. That neither limb of the head twitch dose response curve was impacted by eating high fat chow suggests that no change in sensitivity to drugs acting at 5-HT2A nor at 5-HT2C receptors occurs after eating high fat chow. Together with other studies, these results demonstrate that eating high fat chow changes sensitivity to drugs acting at certain subtypes of 5-HT receptors without affecting sensitivity to drugs acting at other subtypes of 5-HT receptors. Whereas DOM (5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist)-induced head twitching was not affected by eating high fat chow, in a previous study 8-OH-DPAT (5-HT1A receptor agonist)-induced lower lip retraction was significantly enhanced in rats eating high fat chow (Li et al.. 2011). A number of drugs that are used in the clinic (e.g., antidepressants; antipsychotics) vary in their selectivity for different 5-HT receptors (Stahl, 2011) and results of preclinical studies suggest that feeding conditions might alter the therapeutic effectiveness of some, and not other, drugs acting on those receptors. For example, some antipsychotic drugs (including clozapine) are antagonists at 5-HT2A receptors (Meltzer and Massey, 2011). Results of the current study suggest that the clinical effectiveness of drugs acting at 5-HT2A receptors might be reduced under some nutritional conditions (e.g., food restriction and dieting). Insofar as eating high fat chow changes sensitivity to drugs acting at some 5-HT receptor subtypes, it is possible that the actions of indirect-acting 5-HT receptor agonists (e.g., SSRIs) might also be affected by restricting food intake or by eating high fat chow.

Limiting the amount of food that rats eat can also significantly affect the actions of drugs acting on monoamine systems, including both direct- and indirect-acting agonists, For example, food restriction significantly attenuates the effects of the SSRI escitalopram (indirect-acting agonist) in the forced swimming test in rats (France et al., 2009). Although eating high fat chow (free access) did not impact the sensitivity of rats to DOM-induced head twitching, restricting access to food (standard or high fat) decreased sensitivity of all rats to DOM-induced head twitching. The shift rightward in the inverted U-shaped dose-response curve might indicate a decreased sensitivity at both 5-HT2A (ascending limb) and 5-HT2C (descending limb) receptors. These results extend to rats eating high fat food and to head twitching the observation that food restriction decreases sensitivity to effects of both direct- (Li and France, 2008; Li et al., 2009) and indirect- (France et al., 2009) acting 5-HT receptor agonists. That the effects of DOM on body temperature were not significantly affected by food restriction in either group suggests that changes in sensitivity to head twitching are not due to pharmacokinetic factors,

More is known about the impact of different feeding conditions on the actions of drugs acting on dopamine systems, compared with drugs acting on 5-HT systems. Some drugs that act directly at dopamine receptors induce yawning; the dose-response curve for yawning is an inverted U-shape with the ascending limb of the curve mediated by dopamine D3 receptors and the descending limb mediated by D2 receptors (Collins et al., 2005). In the current study, with increasing doses of quinpirole yawning increased then decreased, generating an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve. Consistent with previous studies (Baladi and France 2009; Baladi et al., 2011a), sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning was increased in rats eating high fat chow (compared with rats eating standard chow) as indicated by a shift upward and leftward in the ascending (dopamine D3 receptor mediated) limb of the dose-response curve and by an increase in the maximum number of yawns observed (from 5.5 ± 2.0 yawns during free access to standard chow to 9.8 ± 1.2 yawns during free access to high fat chow). Enhanced sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning is correlated with the development of insulin resistance (Baladi et al., 2011a) suggesting a relationship between insulin signaling and sensitivity of dopamine systems. Insulin and other hormones (i.e., leptin and ghrelin) that are impacted by feeding condition can modulate dopamine signaling (Figlewicz et al., 1998; Palmiter, 2007; Patterson et al., 1998), although the mechanism underlying the enhancement of sensitivity to quinpirole in insulin-resistant rats eating high fat chow is not known (Baladi et al., 2011a; Davis et al., 2010). Also consistent with previous studies (e.g., Baladi and France, 2009) is the finding that food restriction, both in rats eating standard chow and in rats eating high fat chow, nearly eliminated quinpirole-induced yawning. This decrease in quinpirole-induced yawning in food-restricted rats is thought to result from a selective increase in sensitivity at dopamine D2 receptors since agonist-induced yawning is restored in food-restricted rats by administration of a dopamine D2 receptor selective antagonist (Collins et al., 2008). Finally, consistent with other studies (Baladi and France, 2009; Baladi et al., 2011) the hypothermic effects of quinpirole are not different under feeding conditions (eating high fat chow and food restriction) that significantly alter quinpirole-induced yawning, suggesting that differences in sensitivity to quinpirole-induced yawning are not dues to pharmacokinetic factors.

That the sensitivity of rats to DOM and quinpirole was differentially impacted by eating high fat chow shows that some monoamine systems are more sensitive than others to certain manipulations in feeding conditions. There are striking age- and sex-related differences in the extent to which feeding conditions modify the actions of drugs acting on dopamine systems (e.g., Baladi et al., 2012b). For example, adolescent rats are more sensitive than adult rats to the effects of eating high fat chow on the behavioral actions of cocaine (Baladi et al., 2012b), with adolescent females being most sensitive. It is not known whether there are age- and sex-related differences in how different feeding conditions alter sensitivity to the effects of drugs acting on 5-HT systems; however, based on data obtained with drugs acting on dopamine systems, in might be expected that adolescent female rats would be more affected than adult male rats (current study) to the impact of different feeding conditions on sensitivity to drug effects. Given that depression (and prescription of indirect-acting 5-HT receptor agonists [SSRIs]) occurs more in females than in males (Molina et al.. 2013), future studies on the sex-dependence of diet-induced changes in drug effects could provide important information relevant to substance abuse and to variations in therapeutic effectiveness of drugs acting on monoamine, and in particular 5-HT, systems. These data contribute to the growing body of literature demonstrating that feeding conditions can dramatically alter sensitivity to drugs acting on monoamine systems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grant K05DA17918 (CPF) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure/conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. Mechanisms of action of second generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: insights from brain imaging studies. Eur Psychiat. 2005;20:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M, Suemaru K, Cui R, Umeda Y, Li B, Gomita Y, Kawasaki H, Araki H. Effects of physical and psychological stress on 5-HT2A receptor-mediated wet-dog shake responses in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Acta Medica Okayama. 2007;61:205–12. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BJ, Edelstein S, Abramson NW, Katz LE, Yasuda PM, Lavietes SJ, Trief PM, Tollefsen SE, McKay SV, Kringas P, Casey TL, Marcus MD. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in adolescents with type 2 diabetes: baseline data from the TODAY study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2205–7. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, Daws LC, France CP. You are what you eat: influence of type and amount of food consumed on central dopamine systems and the behavioral effects of direct- and indirect-acting dopamine receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 2012a;63:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, France CP. High fat diet and food restriction differentially modify the behavioral effects of quinpirole and raclopride in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;610:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, France CP. Eating high-fat chow increases the sensitivity of rats to quinpirole-induced discriminative stimulus effects and yawning. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21:615–20. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833e7e5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, Koek W, Aumann M, Velasco F, France CP. Eating high fat chow enhances the locomotor-stimulating effects of cocaine in adolescent and adult female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2012b;222:447–57. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baladi MG, Newman AH, France CP. Influence of body weight and type of chow on the sensitivity of rats to the behavioral effects of the direct-acting dopamine-receptor agonist quinpirole. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217:573–85. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarich NC, McConaha CW, Halmi KA, Gendall K, Sunday SR, Gaskill J, La Via M, Frank GK, Brooks S, Plotnicov KH, Kaye WH. Use of nutritional supplements to increase the efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disorder. 2004;35:10–5. doi: 10.1002/eat.10235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard KD, Skinner TC, Peveler R. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with Type 1 diabetes: systematic literature review. Diabetic Med. 2006;23:445–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen HH, Broekkamp CL. Behavioural evidence for functional interactions between 5-HT-receptor subtypes in rats and mice. Brit J Pharmacol. 1990;101:667–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canal CE, Morgan D. Head-twitch response in rodents induced by the hallucinogen 2,5-dimethyoxy-4-iodoamphetamine: a comprehensive history, a re-evaluation of mechanisms, and its utility as a model. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4:556–576. doi: 10.1002/dta.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celada P, Puig M, Amargos-Bosch M, Adell A, Artigas F. The therapeutic role of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in depression. J Psychiatr Neurosci. 2004;29:252–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Calinski DM, Newman AH, Grundt P, Woods JH. Food restriction alters N′-propyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzothiazole-2,6-diamine dihydrochloride (pramipexole)-induced yawning, hypothermia, and locomotor activity in rats: evidence for sensitization of dopamine D2 receptor-mediated effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:691–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Witkin JM, Newman AH, Svensson KA, Grundt P, Cao J, Woods JH. Dopamine agonist-induced yawning in rats: a dopamine D3 receptor-mediated behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:310–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Woods JH. Drug and reinforcement history as determinants of the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:599–605. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.123042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corne SJ, Pickering RW, Warner BT. A method for assessing the effects of drugs on the central actions of 5-hydroxytryptamine. Brit J Pharmacol. 1963;20:106–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1963.tb01302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Martin BR, Glennon RA. Withdrawal from chronic treatment with (+/-)-DOI causes super-sensitivity to 5-HT2 receptor-induced head-twitch behaviour in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;186:115–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JF, Choi DL, Benoit SC. Insulin, leptin and reward. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:619–30. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vry J, Schreiber R. Effects of selected serotonin 5-HT(1) and 5-HT(2) receptor agonists on feeding behavior: possible mechanisms of action. Neurosci Behav R. 2000;24:341–53. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Prado-Lima PA, Chatkin JM, Taufer M, Oliveira G, Silveira E, Neto CA, Haggstram F, Bodanese LC, da Cruz IB. Polymorphism of 5HT2A serotonin receptor gene is implicated in smoking addiction. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;128B:90–3. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham HA, Truett GE. Development of insulin resistance and hyperphagia in Zucker fatty rats. Am J Physiol REgul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R652–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00428.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Reissig CJ, Katz EB, Yarosh HL, Rice KC, Winter JC. Hallucinogen-like effects of N,N-dipropyltryptamine (DPT): possible mediation by serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in rodents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;88:358–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Simoneau J, Cohen MS, Zimmerman SM, Henson CM, Rice KC, Woods JH. Interaction of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in R(−)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine-elicited head twitch behavior in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:728–34. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.172247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlewicz DP, Patterson TA, Johnson LB, Zavosh A, Israel PA, Szot P. Dopamine transporter mRNA is increased in the CNS of Zucker fatty (fa/fa) rats. Brain Res Bull. 1998;46:199–202. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France CP, Li JX, Owens WA, Koek W, Toney GM, Daws LC. Reduced effectiveness of escitalopram in the forced swimming test is associated with increased serotonin clearance rate in food-restricted rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:731–6. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XF, Huang X, Han M, Chen F, Storlien L, Lawrence A. 5-HT2A/2C receptor and 5-HT transporter densities in mice prone or resistant to chronic high-fat diet-induced obesity: a quantitative autoradiography study. Brain Res. 2004;1018:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenck F, Bos M, Wichmann J, Stadler H, Martin JR, Moreau JL. The role of 5-HT2C receptors in affective disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 1998;10:1587–1599. doi: 10.1517/13543784.7.10.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye W, Gendall K, Strober M. Serotonin neuronal function and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:825–38. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzewa RM, Brus R, Rykaczewska M, Plech A. Low-dose quinpirole ontogenically sensitizes to quinpirole-induced yawning in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;44:487–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90496-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JX, France CP. Food restriction and streptozotocin treatment decrease 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptor-mediated behavioral effects in rats. Behav Pharm. 2008;19:292–7. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328308f1d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JX, Ju S, Baladi MG, Koek W, France CP. Eating high fat chow increases the sensitivity of rats to 8-OH-DPAT-induced lower lip retraction. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:751–7. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32834d0eeb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JX, Koek W, France CP. Food restriction and streptozotocin differentially modify sensitivity to the hypothermic effects of direct- and indirect-acting serotonin receptor agonists in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;613:60–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire BA, Baladi MG, France CP. Eating high-fat chow enhances sensitization to the effects of methamphetamine on locomotion in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;658:156–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Massey BW. The role of serotonin receptors in the action of atypical antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata S, Hirano S, Kamei J. Diabetes attenuates the antidepressant-like effect mediated by the activation of 5-HT1A receptor in the mouse tail suspension test. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;29:461–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina MA, Jansen K, Drews C, Pinheiro R, Silva R, Souza L. Major depressive disorder symptoms in male and female young adults. Psychol Health Med. 2013 doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.793369. (Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Mach RH. Self-administration of the dopamine D3 agonist 7-OH-DPAT in rhesus monkeys is modified by prior cocaine exposure. Psychopharmacol. 1996;125:13–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02247388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmiter RD. Is dopamine a physiologically relevant mediator of feeding behavior? Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TA, Brot MD, Zavosh A, Schenk JO, Szot P, Figlewicz DP. Food deprivation decreases mRNA and activity of the rat dopamine transporter. Neuroendocrinology. 1998;68:11–20. doi: 10.1159/000054345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Mizuguchi Y, Ohno Y. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: role of 5-HT receptors in modulating cognitive and extrapyramidal motor functions. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013 doi: 10.2174/18715273113129990088. [Eup ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaiman S. Restricted diets restrict antidepressant efficacy. Practitioner. 1989;233:972, 975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers SP, Easton N, Malcolm CS, Allen NH, Porter RH, Bickerdike MJ, Kennett GA. Modulation of 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated head-twitch behaviour in the rat by 5-HT(2C) receptor agonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;69:643–52. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrzosek M, Jakubczyk A, Wrzosek M, Matsumoto H, Lukaszkiewicz J, Brower KJ, Wojnar M. Serotonin 2A receptor gene (HTR2A) polymorphism in alcohol-dependent patients. Pharmacol Rep. 2012;64:449–53. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70787-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]