Abstract

Background and Aim

The infection of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is acquired in childhood and the prevalence vary greatly in different countries and regions. The study aimed to investigate the characteristics of H. pylori infection among children with gastrointestinal symptoms in Hangzhou, a representative city of eastern China.

Methods

A systematic surveillance of H. pylori infection according to the 13C-urea breath test was conducted from January 2007 to December 2014 in the Children’s hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. The demographic information and main symptoms of every subject were recorded.

Results

A total of 12,796 subjects were recruited and 18.6% children evaluated as H. pylori positive. The annual positive rates decreased from 2007 to 2014 (χ2 = 20.461, p < 0.01). The positive rates were 14.8%, 20.2% and 25.8% in 3–6, 7–11 and 12–17 years age group respectively, which increased with age (χ2 = 116.002, p < 0.01). And it was significantly higher in boys than girls (χ2 = 15.090, p < 0.01). Multivariate logistic regression identified possible risk factors for H. pylori infection. Age, gender, gastrointestinal symptoms and history of H. pylori infected family member were all significantly associated with H. pylori infection (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

H. pylori infection rates in children with gastrointestinal symptoms were lower than most of those reported in mainland China. Further studies are required to determine the prevalence in the general population. Comprehensively understanding of the characteristics and the possible risk factors of H. pylori infection will be helpful to its management strategies in children in China.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT), Age, Gender, Gastrointestinal symptoms, Children

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium which selectively colonizes in the human stomach mucosa. The prevalence of H. pylori infection is about 50% of the world’s population and gastric cancer related to H. pylori infection is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide (Atherton & Blaser, 2009). In general, the prevalence in less developed or developing countries is higher than that in developed countries (Fock & Ang, 2010). The infection rates are reported varying from 15.5% to 93.6% in developed and developing countries, respectively (Eusebi, Zagari & Bazzoli, 2014; Mentis, Lehours & Mégraud, 2015; Tonkic et al., 2012).

It is now accepted that H. pylori infection is acquired in childhood (Rowland et al., 2006), and H. pylori generally persists for the life of the host in the absence of antibiotic therapy (Pacifico et al., 2010). The incidence and prevalence rates of childhood infection with H. pylori also vary greatly worldwide. Within developed nations, prevalence rates of H. pylori infection among children have been shown to range from 6.5% to 65% (Roma & Miele, 2015; Tonkic et al., 2012). Now in European and North America, the epidemiology of H. pylori infection in children has changed in recent decades with low incidence rates, which resulting in prevalence lower than 10% in children and adolescents (Kindermann & Lopes, 2009). However, there were few reports in developing counties. There has been a decrease in the H. pylori infection rate in the general Chinese population in recent years but it also remained high in some areas among both children and adults after fifteen years (Ding et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2009a).

China is regarded as one of the largest developing country inhabited by more than one-fifth of the world’s population although there has been rapid growth in economy in the past decade. The very limited data showed that the prevalence rate of H. pylori infection in Chinese children ranged from 6.8% in three cities of China to 72.3% in northwest China with large regional variations (Ding et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2009b). Hangzhou, the capital city of Zhejiang Province, which had made quick improvements in industrialization and socioeconomic conditions since the 1980s, is a representative city of eastern China. But few studies have assessed the prevalence of H. pylori infection in this area. The lack of these data in our pediatric population has hampered the better understanding of the disease burden in our society and the healthcare planning for resources allocation to tackle H. pylori-associated diseases which are usually encountered in adulthood. The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of H. pylori infection among children in Hangzhou, China from 2007 to 2014 and evaluate the characteristics of H. pylori infection in children.

Methods

Study population

Subjects aged from three to 18 years old who were referred for the detection of H. pylori infection using 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) were recruited at the Children’s hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine from January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2014. The main symptoms of every subject, besides a history of H. pylori infected family member were recorded, including abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea/vomiting, abdominal distension, hiccup, constipation, halitosis, diarrhea and failure to thrive/weight loss. All children should have been fasting more than 6 h, and had not used bismuth salts, proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), or any antibiotics (amoxicillin, tetracycline, metronidazole, clarithromycin, azithromycin, or other) within one month before the 13C-UBT (Koletzko et al., 2011). The major exclusion criteria included: age younger than three or older than 18, children with incomplete patient data, patients who previously diagnosed as H. pylori infection and received treatment for H. pylori infection even with drug withdrawal 4 weeks prior to the 13C-UBT.

Detection of H. pylori infection

H. pylori infection was established by the 13C-UBT kit, Helikit (Isodiagnostika Inc., Edmonton, AB, Canada) according to standard protocols. Briefly, after a minimum fasting period of 6 h, a baseline exhaled breath sample was obtained using a collection bag. The children then drank 75 ml of a citrus-flavoured liquid preparation (75 mg of 13C-labelled urea). Thirty minutes later, another breath exhaled sample was stored in collection bag. Breath samples were stored at room temperature and then analyzed by an isotope selective nondispersive infrared spectrometer, namely by ISOMAX 2000 (Isodiagnostika Inc., Edmonton, AB, Canada). The test was defined as positive when delta over baseline (DOB) value calculated after thirty minutes was 3.5 δ‰ or more (Mauro et al., 2006).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics such as median and interquartile range of age, percentages were calculated for demographic data and results were analyzed by chi-squaretest. The distribution of H. pylori infection rate by year was analyzed by Linear-by-Linear association. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to control for the potential confounding variables associated with H. pylori infection. Results of logistic regression were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc, USA) and P value was calculated. Two tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board and Institutional Ethics Committees of the Children’s hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2016-IRBAL-078).

Results

Demographic data

A total of 12,796 subjects were enrolled in this study and there were 6,880 boys and 5,916 girls, yielding a male-to-female ratio of 1.16:1. All children were divided into three age groups, including 3–6 (pre-school age), 7–11 (school age) and 12–17 (adolescent) years age group. The gender distribution was consistent in different age groups. The median and interquartile range of age of all children were 7.50 (5.75–10.08) years, while boys were 7.50 (5.67–10.08) years and girls were 7.58 (5.83–10.08) years.

H. pylori infection rate

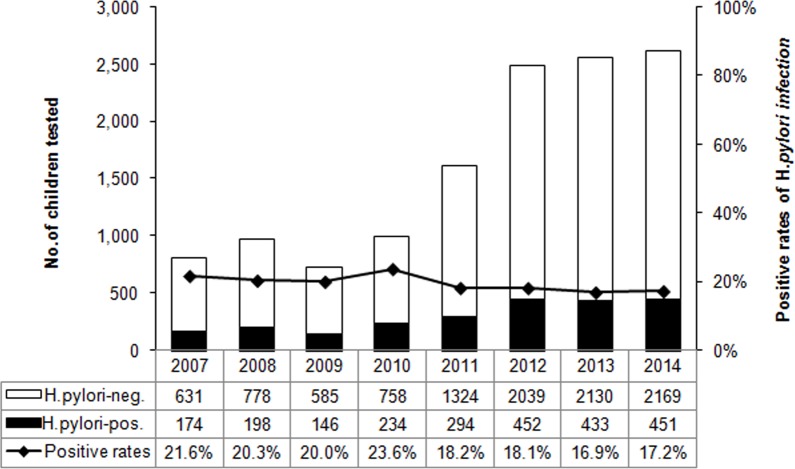

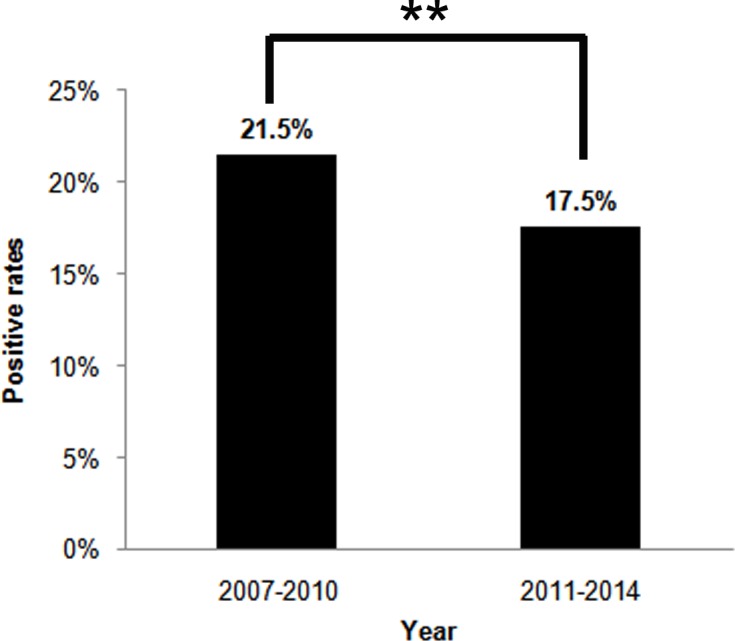

Overall, 18.6% (2,382/12,796) children were H. pylori positive according to the DOB value of 13C-UBT (Table 1). The annual positive rates decreased from 2007 to 2014 (χ2 = 20.461, p < 0.01) (Fig. 1). And the infection rate decreased in the latest four-year period 2011–2014, compared to the former four-year period 2007–2010 (χ2 = 25.798, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2). The positive rates of H. pylori was 14.8% (800/5,408) in 3–6 years age group, 20.2% (1,179/5,829) in 7–11 years age group, and 25.8% (403/1,559) in 12–17 years age group, which increased with age and were statistically significant (χ2 = 116.002, p < 0.001) (Table 1). Furthermore, the positive rates were higher in boys (19.9%, 1,366/6,880) than girls (17.2%, 1,016/5,916), and the difference was also statistically significant (χ2 = 15.090, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the 12,796 subjects.

| H. pylori-positive | H. pylori-negative | Total | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | ||||

| 3–6 | 800 (14.8) | 4,608 (85.2) | 5,408 | <0.001 |

| 7–11 | 1,179 (20.2) | 4,650 (79.8) | 5,829 | |

| 12–17 | 403 (25.8) | 1,156 (74.2) | 1,559 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1,016 (17.2) | 4,900 (82.8) | 5,916 | <0.001 |

| Male | 1,366 (19.9) | 5,514 (80.1) | 6,880 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | ||||

| No | 432 (17.5) | 2,034 (82.5) | 2,466 | 0.119 |

| Yes | 1,950 (18.9) | 8,380 (81.1) | 10,330 | |

| History of H. pylori infected family member | ||||

| No | 2,139 (18.4) | 9,488 (81.6) | 11,627 | 0.045 |

| Yes | 243 (20.8) | 926 (79.2) | 1,169 | |

| Total | 2,382 (18.6) | 10,414 (81.4) | 12,796 | – |

Notes.

Data expressed as number (%).

Figure 1. The distribution of H. pylori infection rate by year from 2007 to 2014.

The bars represent the number of enrolled subjects each year. H. pylori negative and positive subjects are white and black respectively. The line chart represent the positive rates of H. pylori infection each year.

Figure 2. The H. pylori infection rates between two four-year period, 2007–2010 and 2011–2014.

The percentages on top of the bars represent the total H. pylori infection rates in four-year periods. **p < 0.01.

The main gastrointestinal symptoms of children undergoing 13C-UBT are abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea/vomiting, abdominal distension, hiccup, constipation, halitosis, diarrhea and failure to thrive/weight loss. There were 80.7% children (10,330/12,796) with at least one gastrointestinal symptom in the prior months. The positive rate of H. pylori infection in children with these symptoms was 18.9% (1,950/10,330), demonstrating no significant difference compared to 19.3% (2,466/12,796) children without gastrointestinal symptoms (17.5%, 432/2,466) (χ2 = 2.426, p = 0.119) (Table 1).

There were 1,169 children had a history of H. pylori infected family member, and the H. pylori infection rate was higher than those without a familial history (20.8% versus 18.4%, χ2 = 4.005, p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Possible risk factors associated with H. pylori infection

Table 2 shows the results from the multivariate logistic regression performed to assess risk factors for H. pylori infection. Age, gender, gastrointestinal symptoms and history of H. pylori infected family member were found together to be significantly associated with H. pylori infection (all p < 0.05). Specifically, children in 7–11 years age group and in 12–17 years age group were 1.474 and 2.031 times as likely to be H. pylori infected as children in 3–6 years age group (95% CI [1.335–1.627] and 95% CI [1.772–2.328] respectively, all p < 0.001). Boys were 1.209 times as likely to be H. pylori infected as girls (95% CI [1.104–1.323], p < 0.001) and children with a history of H. pylori infected family member were 1.289 times compared to those without the familial history. Furthermore, gastrointestinal symptom was also one of risk factors for H. pylori infection, as it was 1.141 times in children with gastrointestinal symptoms compared to children without them (95% CI [1.009–1.289], p < 0.05).

Table 2. Logistic regression analysis for possible risk factors associated with H. pylori infection.

| Variables | OR (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | ||

| 3–6 | – | |

| 7–11 | 1.474 (1.335–1.627) | <0.001 |

| 12–17 | 2.031 (1.772–2.328) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | – | |

| Male | 1.209 (1.104–1.323) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | ||

| No | – | |

| Yes | 1.141 (1.009–1.289) | 0.035 |

| History of H. pylori infected family member | ||

| No | – | |

| Yes | 1.289 (1.100–1.511) | 0.002 |

Notes.

- OR

- odds ratio

- CI

- confidence interval

Discussions

The present study assessed the 13C-UBT in the pre-treatment phase to evaluate current H. pylori infection in children with gastrointestinal symptoms. The prevalence was higher than in developed countries but lower than in some developing countries (Tonkic et al., 2012). It was higher than it reported in three cities (Beijing, Guangzhou and Chengdu) of mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan among asymptomatic children or school children, but lower than most of mainland China (Table 3). These could be due to cohort selection, detection method and the geographic area difference which may also reflect the personal and environmental hygiene. Subjects in our study enrolled from patients most of that had gastrointestinal symptoms and were suggested to detect the H. pylori infection, so the incidence rate would be more or less higher than asymptomatic or general population. Currently, there are many diagnostic tools to detect H. pylori infection, with non-invasive methods being considered as the most desirable for use especially in children. The 13C-UBT has been reported to have excellent sensitivity and specificity for the noninvasive identification of H. pylori infection in children and it is recommended for situations when endoscopy is not available or necessary (Guarner et al., 2010; Redéen et al., 2011). 13C-UBT has superiority over serologic methods by its high reliability and the ability to differentiate present from past infection (Bourke et al., 2005). The geographic distribution of H. pylori infection is correlated with the geographic distribution of gastric cancer. Muping County in Shandong Province, Wuwei County in Gansu Province and Jiangsu Province are all the area with high risk of gastric cancer (Shi et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009a; Zhang et al., 2009b). That may be associated with the high prevalence of H. pylori infection in this area.

Table 3. Comparison of prevalence of H. pylori infection among children in China.

| Authors | Recruitment | Area | Year | Age (year) | Method | No. | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ding et al. (2015) | Asymptomatic children | Beijing | 2009–2011 | Newborn | HpSA | 330 | 0.6 |

| Guangzhou | 1–12m | 319 | 2.5 | ||||

| Chengdu | 1–3 | 289 | 2.1 | ||||

| 4–6 | 624 | 7.2 | |||||

| 7–9 | 528 | 6.1 | |||||

| 10–12 | 308 | 11.0 | |||||

| 13–15 | 685 | 8.0 | |||||

| 16–18 | 408 | 13.5 | |||||

| Tam et al. (2008) | School children | Hong Kong | 2007 | 6–8 | UBT | 300 | 9.3 |

| 9–10 | 301 | 11.0 | |||||

| 11–12 | 472 | 14.8 | |||||

| 13–14 | 779 | 13.0 | |||||

| 15–16 | 289 | 12.5 | |||||

| 17–19 | 339 | 16.5 | |||||

| Lin et al. (2007) | School children | Taiwan | 2004 | 9–12 | Serology | 1,625 | 11.0 |

| 13–15 | 325 | 12.3 | |||||

| Zhang et al. (2009a) | School children | Muping, | 2006 | 8–9 | HpSA | 122 | 26.2 |

| Shandong | 10–11 | 125 | 40.0 | ||||

| 12–13 | 142 | 41.6 | |||||

| 14–15 | 131 | 42.0 | |||||

| Yanqing, | 2006 | 8–9 | HpSA | 130 | 15.4 | ||

| Beijing | 10–11 | 136 | 27.9 | ||||

| 12–13 | 125 | 29.6 | |||||

| 14–15 | 125 | 29.6 | |||||

| Chen et al. (2007) | Population-based cohort | Guangzhou | 2003 | 3–5 | Serology | 180 | 19.4 |

| Guangdong | 5–10 | 105 | 22.9 | ||||

| 10–20 | 185 | 36.8 | |||||

| Cheng et al. (2009) | Population-based cohort | Beijing | 2003 | 2–10 | UBT | 19 | 57.8 |

| 11–20 | 52 | 46.2 | |||||

| Shi et al. (2008) | Population-based cohort | Jiangsu | 2004–2005 | <20 | UBT/Serology | 48 | 60.4 |

| Zhang et al. (2009b) | Population-based cohort | Wuwei, | 2007–2008 | 3–5 | HpSA | 99 | 68.7 |

| Gansu | 6–9 | 240 | 70.4 | ||||

| 10–14 | 440 | 73.0 | |||||

| 15–18 | 159 | 75.5 | |||||

| Zhang & Li (2012) | Gastrointestinal symptoms | Dongguan, | 2010–2011 | 3–7 | Histology/ | 119 | 39.5 |

| Guangdong | 8–12 | RUT/ | 134 | 41.0 | |||

| 13–16 | UBT | 123 | 54.5 | ||||

| Wu et al. (2008) | Gastrointestinal symptoms | Zunyi | 2000–2006 | 10–20 | UBT | 2,645 | 40.0 |

| Our study | Gastrointestinal symptoms | Hangzhou, | 2007–2014 | 3–6 | UBT | 5,408 | 14.8 |

| Zhejiang | 7–11 | 5,829 | 20.2 | ||||

| 12–17 | 1,559 | 25.8 |

Notes.

- HpSA

- H. pylori stool antigen test

- UBT

- urea breath test

- RUT

- rapid urease test

- m

- months

Although there is apparent variation in the prevalence of H. pylori infection between developing and developed countries in children, it is reported all around the world that the prevalence was associated with age (Tkachenko et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009a). In our study, the prevalence of H. pylori infection was also shown to increase with age. Pre-school age children had a lower significant prevalence than school age and adolescent. The increase in H. pylori prevalence with age is thought to represent the improvements in socioeconomic conditions and sanitary standards through the generations. In Russia, the prevalence of H. pylori infection reduced markedly within a 10-year period (from 1995 to 2005) due to the improvements in standards of living (Tkachenko et al., 2007). With the development of economic growth in China within decades, the environmental and hygienic conditions were dramatically improved, due to which the prevalence of H. pylori infection is decreasing in China (Nagy, Johansson & Molloy-Bland, 2016). In consistent with it, the annual positive rates decreased during eight-year period (from 2007 to 2014) in our study (Fig. 1). The age-dependent manner of H. pylori positive rate in children may also reflect the inverse relation to the socioeconomic status, sanitation and living conditions in China (Zhang et al., 2009a). The increase of prevalence might be the effect of accumulation because that the acquisition rates were higher than the loss rates (Ozen, Ertem & Pehlivanoglu, 2006). With the growing of age, expanding range of activity, collective living and meal in high school lead to the increase of exposure to H. pylori infection and opportunities to cross infection (Zhang & Li, 2012). But it needs to be further investigated.

It was reported that the male predominance of H. pylori infection in adults was a global and homogeneous phenomenon, but such predominance was not apparent in children (De Martel & Parsonnet, 2006; Tkachenko et al., 2007). But our data showed a higher prevalence in boys than girls and in different years age group (Table 2). It is consistent with the study in Brazil that male gender was one of the risk factors for the acquisition and maintenance of the H. pylori infection (Queiroz et al., 2012). The prevalence of H. pylori infection in a community is related to three factors: the incidence rate of infection, the rate of infection loss (either spontaneous eradication or curative treatment) and the relative survival of those with and without infection. Differential incidence, differential antibiotic exposure or differential protective immunity between genders, which lead to greater loss of infection (or seroreversion) in girls or adults women than in men, may explain the different results observed between children and adult studies (De Martel & Parsonnet, 2006). On the other hand,it may be explained that boys are naturally more active and have poor personal hygiene than girls as the prevalence of H. pylori infection is inversely related to sanitation condition. But the role of gender as a risk factor for H. pylori infection is still debated.

Abdominal complaints such as pain, anorexia, nausea/vomiting, or other dyspeptic symptoms are nonspecific and can be caused by different organic disease within and outside the digestive tract. The European Pediatric Task Force concluded in their guidelines on management of H. pylori infection that, in children, H. pylori infection is not related to gastrointestinal symptoms (Drumm, Koletzko & Oderda, 2000). Studies comparing the prevalence among symptomatic and asymptomatic children show different results on the relationship between gastrointestinal symptoms and the prevalence of H. pylori infection (Daugule et al., 2007; Dore et al., 2012). A meta-analysis reported recently that children with upper abdominal pain or epigastric pain were at two- to three fold higher risk for H. pylori infection than children without these symptoms but it could not been confirmed in children seen in primary care (Spee et al., 2010). According to multivariate logistic regression analysis, our study showed that gastrointestinal symptom and a history of H. pylori infected family member were also the significant risk factors for H. pylori infection. Similarly, other studies showed that upper GIT symptoms (RAP, anorexia, nausea), family history of peptic disease, and nausea/vomiting were significantly associated with H. pylori infection (Dore et al., 2012; Habib et al., 2014). However, there are many other possible risk factors associated with H. pylori infection identified in most of the published studies, including socioeconomic indicators, family income, household crowding, number of children sharing the same room, parents’ education and sharing a bed with children (Ertem, 2013). Our results were limited because of cohort selection and the lack of data in these matters, and the determinants of H. pylori infection should be investigated by further studies.

In conclusion, the strength of our study was that it evaluated a large number of children in a long period in Hangzhou, a representative city of eastern China. The prevalence of H. pylori infection using 13C-UBT increased with age in children and boys were apt to be H. pylori positive compared with girls. The founding suggests that primary infection in childhood is usual and the effect of accumulation might be responsible for the increase of prevalence with age. Besides age and male predominance, gastrointestinal symptom and a history of H. pylori infected family member were also the possible risk factors for H. pylori infection. In children with history of H. pylori infected family member, testing for H. pylori may be considered especially when they are symptomatic. These observations could substantially change H. pylori management strategies in children in China.

Supplemental Information

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the children and their parents for providing the information to take part in this study. We also thank Lejing Yang and Qian Shu for typewriting the data and thank Kewen Jiang, Weifen Zhu and Xi Chen for suggestions on article editing.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81100268). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Xiaoli Shu performed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables.

Mingfang Ping and Guofeng Yin contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools.

Mizu Jiang conceived and designed the experiments, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Human Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

The study was approved by the parents and the ethics committees of the Children’s hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2016-IRBAL-078).

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as a Supplemental File.

References

- Atherton & Blaser (2009).Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: ancient history, modern implications. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119:2475–2487. doi: 10.1172/JCI38605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke et al. (2005).Bourke B, Ceponis P, Chiba N, Czinn S, Ferraro R, Fischbach L, Gold B, Hyunh H, Jacobson K, Jones NL, Koletzko S, Lebel S, Moayyedi P, Ridell R, Sherman P, Van Zanten S, Beck I, Best L, Boland M, Bursey F, Chaun H, Cooper G, Craig B, Creuzenet C, Critch J, Govender K, Hassall E, Kaplan A, Keelan M, Noad G, Robertson M, Smith L, Stein M, Taylor D, Walters T, Persaud R, Whitaker S, Woodland R. Canadian Helicobacter Study Group Consensus Conference: update on the approach to Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents–an evidence-based evaluation. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;19:399–408. doi: 10.1155/2005/390932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al. (2007).Chen J, Bu XL, Wang QY, Hu PJ, Chen MH. Decreasing seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection during 1993–2003 in Guangzhou, southern China. Helicobacter. 2007;12:164–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng et al. (2009).Cheng H, Hu F, Zhang L, Yang G, Ma J, Hu J, Wang W, Gao W, Dong X. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and identification of risk factors in rural and urban Beijing, China. Helicobacter. 2009;14:128–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugule et al. (2007).Daugule I, Rumba I, Alksnis J, Ejderhamn J. Helicobacter pylori infection among children with gastrointestinal symptoms: a high prevalence of infection among patients with reflux oesophagitis. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96:1047–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Martel & Parsonnet (2006).De Martel C, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori infection and gender: a meta-analysis of population-based prevalence surveys. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2006;51:2292–2301. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding et al. (2015).Ding Z, Zhao S, Gong S, Li Z, Mao M, Xu X, Zhou L. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic Chinese children: a prospective, cross-sectional, population-based study. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2015;42:1019–1026. doi: 10.1111/apt.13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore et al. (2012).Dore MP, Fanciulli G, Tomasi PA, Realdi G, Delitala G, Graham DY, Malaty HM. Gastrointestinal symptoms and Helicobacter pylori infection in school-age children residing in Porto Torres, Sardinia, Italy. Helicobacter. 2012;17:369–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumm, Koletzko & Oderda (2000).Drumm B, Koletzko S, Oderda G. Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a consensus statement. European Paediatric Task Force on Helicobacter pylori. Journal of Pediatrics Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2000;30:207–213. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200002000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertem (2013).Ertem D. Clinical practice: Helicobacter pylori infection in childhood. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;172:1427–1434. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eusebi, Zagari & Bazzoli (2014).Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2014;19(Suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/hel.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fock & Ang (2010).Fock KM, Ang TL. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer in Asia. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;25:479–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarner et al. (2010).Guarner J, Kalach N, Elitsur Y, Koletzko S. Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests in children: review of the literature from 1999 to 2009. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;169:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib et al. (2014).Habib HS, Hegazi MA, Murad HA, Amir EM, Halawa TF, El-Deek BS. Unique features and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection at the main children’s intermediate school in Rabigh, Saudi Arabia. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;33:375–382. doi: 10.1007/s12664-014-0463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindermann & Lopes (2009).Kindermann A, Lopes AI. Helicobacter pylori infection in pediatrics. Helicobacter. 2009;14(Suppl 1):52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koletzko et al. (2011).Koletzko S, Jones NL, Goodman KJ, Gold B, Rowland M, Cadranel S, Chong S, Colletti RB, Casswall T, Elitsur Y, Guarner J, Kalach N, Madrazo A, Megraud F, Oderda G. Evidence-based guidelines from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN for Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Journal of Pediatrics Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2011;53:230–243. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182227e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin et al. (2007).Lin DB, Lin JB, Chen CY, Chen SC, Chen WK. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among schoolchildren and teachers in Taiwan. Helicobacter. 2007;12:258–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro et al. (2006).Mauro M, Radovic V, Zhou P, Wolfe M, Kamath M, Bercik P, Croitoru K, Armstrong D. 13C urea breath test for (Helicobacter pylori): determination of the optimal cut-off point in a Canadian community population. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;20:770–774. doi: 10.1155/2006/472837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentis, Lehours & Mégraud (2015).Mentis A, Lehours P, Mégraud F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2015;20(Suppl 1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/hel.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, Johansson & Molloy-Bland (2016).Nagy P, Johansson S, Molloy-Bland M. Systematic review of time trends in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China and the USA. Gut Pathogens. 2016;8:8. doi: 10.1186/s13099-016-0091-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozen, Ertem & Pehlivanoglu (2006).Ozen A, Ertem D, Pehlivanoglu E. Natural history and symptomatology of Helicobacter pylori in childhood and factors determining the epidemiology of infection. Journal of Pediatrics Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2006;42:398–404. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000215307.48169.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifico et al. (2010).Pacifico L, Anania C, Osborn JF, Ferraro F, Chiesa C. Consequences of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16:5181–5194. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i41.5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz et al. (2012).Queiroz DM, Carneiro JG, Braga-Neto MB, Fialho AB, Fialho AM, Goncalves MH, Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Braga LL. Natural history of Helicobacter pylori infection in childhood: eight-year follow-up cohort study in an urban community in northeast of Brazil. Helicobacter. 2012;17:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redéen et al. (2011).Redéen S, Petersson F, Törnkrantz E, Levander H, Mårdh E, Borch K. Reliability of diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2011;2011:940650. doi: 10.1155/2011/940650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roma & Miele (2015).Roma E, Miele E. Helicobacter pylori infection in pediatrics. Helicobacter. 2015;20(Suppl 1):47–53. doi: 10.1111/hel.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland et al. (2006).Rowland M, Daly L, Vaughan M, Higgins A, Bourke B, Drumm B. Age-specific incidence of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:65–72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi et al. (2008).Shi R, Xu S, Zhang H, Ding Y, Sun G, Huang X, Chen X, Li X, Yan Z, Zhang G. Prevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese populations. Helicobacter. 2008;13:157–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spee et al. (2010).Spee LA, Madderom MB, Pijpers M, Van Leeuwen Y, Berger MY. Association between helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal symptoms in children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e651–e669. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam et al. (2008).Tam YH, Yeung CK, Lee KH, Sihoe JD, Chan KW, Cheung ST, Mou JW. A population-based study of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese children resident in Hong Kong: prevalence and potential risk factors. Helicobacter. 2008;13:219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko et al. (2007).Tkachenko MA, Zhannat NZ, Erman LV, Blashenkova EL, Isachenko SV, Isachenko OB, Graham DY, Malaty HM. Dramatic changes in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection during childhood: a 10-year follow-up study in Russia. Journal of Pediatrics Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2007;45:428–432. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318064589f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkic et al. (2012).Tonkic A, Tonkic M, Lehours P, Mégraud F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2012;17(Suppl 1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al. (2008).Wu HC, Tuo BG, Wu WM, Gao Y, Xu QQ, Zhao K. Prevalence of peptic ulcer in dyspeptic patients and the influence of age, sex, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2008;53:2650–2656. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang & Li (2012).Zhang Y, Li JX. Investigation of current infection with Helicobacter pylori in children with gastrointestinal symptoms. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2012;14:675–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2009a).Zhang DH, Zhou LY, Lin SR, Ding SG, Huang YH, Gu F, Zhang L, Li Y, Cui RL, Meng LM, Yan XE, Zhang J. Recent changes in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among children and adults in high- or low-incidence regions of gastric cancer in China. Chinese Medical Journal. 2009a;122:1759–1763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2009b).Zhang LH, Zhou YN, Zhang ZY, Zhang FH, Li GZ, Li Q, Wu ZQ, Ren BL, Zou SJ, Wang JX. Epidemiological study on status of Helicobacter pylori in children and teenagers in Wuwei city, Gansu province. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009b;89:2682–2685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as a Supplemental File.