Abstract

All methanogenic Archaea examined to date rely on methanogenesis as their sole means of energy conservation. Among these are ones that use carbon monoxide as a growth substrate, producing methane via a pathway that involves hydrogen as an intermediate. To further examine the role of hydrogen in this process, we tested the ability of Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A, a metabolically versatile methanogen devoid of significant hydrogen metabolism, to use CO as a growth substrate. M. acetivorans grew on CO to high cell densities (≈1 × 108 per ml) with a doubling time of ≈24 h. Surprisingly, acetate and formate, rather than methane, were the major metabolic end products as shown by 13C NMR studies and enzymatic analysis of culture supernatants. Methane formation surpassed acetate/formate formation only when the cultures entered stationary growth phase, strongly suggesting that M. acetivorans conserves energy by means of this acetogenic and formigenic process. Resting cell experiments showed that methane production decreased linearly with increasing CO partial pressures, consistent with inhibition of methanogenesis by CO. Transposon-induced M. acetivorans mutants with lesions in the operon encoding phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase failed to use either acetate or CO as growth substrates, indicating that these enzymes are required for both aceticlastic methanogenesis and carboxidotrophic acetogenesis. These findings greatly extend our concept of energy conservation and metabolic versatility in the methanogenic Archaea.

Keywords: acetogenesis, methanogenesis

The only known pathway for energy conservation in methanogenic Archaea is methanogenesis. In these organisms, methane is produced either by the stepwise reduction of CO2 via cofactor-bound intermediates or by transfer of methyl groups from methylated compounds to a coenzyme and subsequent reduction to methane (reviewed in refs. 1–3). Although most methanogens are able to reduce CO2 by using H2 as a reductant, only members of the Methanosarcinales use acetate and methylated compounds, such as methanol or methylamines, for growth as well. These compounds serve as both electron donors and acceptors for the methanogenic process. Also, two methanogenic species have been shown to use carbon monoxide (CO) as a methanogenic growth substrate, whereas Methanosphaera species are able to grow on the combination of methanol and H2. Regardless of the substrate, methane and CO2 are the only major products of all methanogenic bioconversions; although some other products occasionally have been detected, these are generated only in minor amounts (4–8). Thus, all methanogens examined to date are obligate methanogens.

Microbial CO consumption is an environmentally important process that fuels the reentry of CO into the global carbon cycle and helps maintain atmospheric CO below toxic levels (9). CO oxidation is a property of numerous bacterial genera, both aerobic and anaerobic. Phototrophic anaerobes such as Rhodocyclus gelatinosus and Rhodospirillum rubrum couple CO oxidation, which is catalyzed by the monofunctional carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH), to H2 evolution in an energy-conserving process (10, 11). Acetogenic anaerobes metabolize CO to acetyl-CoA (12, 13), which is subsequently converted to acetate by phosphotransacetylase (Pta) and acetate kinase (Ack) (14, 15). CO is not, however, a common methanogenic growth substrate. Only Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus and Methanosarcina barkeri have been shown to use CO (5, 16, 17). In these organisms, 4 mol of CO is oxidized to CO2 for every 1 mol of CO2 reduced to methane. During carboxidotrophic growth, both organisms produce substantial amounts of hydrogen gas, which is later remetabolized, presumably serving as the source of electrons for reduction of CO2 to CH4. It has been argued that CO-dependent H2 production might be a prerequisite for ATP synthesis during growth of methanogens on CO (16).

Whereas the CO-oxidizing organism M. barkeri is also capable of robust growth on H2/CO2, its close relative Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A is unable to use this substrate (18) and has very low levels of hydrogenase activity (19). We were therefore interested in testing whether this organism could metabolize CO. Examination of the complete genome sequence of M. acetivorans revealed the presence of multiple CODHs, the central enzymes in microbial CO metabolism, indicating the potential capacity of this organism to use CO. Two ORFs identified in M. acetivorans appear to encode monofunctional CODHs, similar to those found in Rhodospirillum; two additional operons appear to encode the bifunctional CODH/acetyl-CoA synthases, more typical of those found in methanogenic archaea (20). In this report, we show that M. acetivorans is, indeed, able to grow on CO. Surprisingly, the major products of growth are not methane, but acetic and formic acids.

Materials and Methods

Media and Growth Conditions. M. acetivorans C2A (DSM 2834; ref. 18) was cultivated in single-cell morphology (21) under strictly anaerobic conditions at 37°C in high-salt medium as described in ref. 22. Methanol (125 mM), sodium acetate (120 mM), or CO (see below) served as growth substrate. Growth was monitored by following the OD at 600 nm (OD600) or 420 nm (OD420). Cell titer was determined microscopically with a Petroff–Hausser cell-counting chamber (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA). Two mutant strains, M. acetivorans WWM56 (pta1::miniMAR366) and M. acetivorans WWM57 (pta2::miniMAR366) (23), were cultivated in the presence of puromycin (2 μg/ml). 2-Bromoethanesulfonic acid (BES) was supplemented from sterile anaerobic stock solutions to a final concentration of 5 mM as indicated.

For adaptation to CO as the sole energy source, cultures exponentially growing on methanol (OD600 ≈ 0.5) were diluted 1:10 into fresh high-salt medium and supplemented daily with 5% (vol/vol) of the gas phase with CO (Matheson). The cultures were incubated with gentle agitation until the OD600 had doubled twice, and then the cultures were diluted again as above. This process was repeated several times, successively increasing the amount of CO supplemented, up to 105 Pa. CO-adapted cultures were maintained by dilution up to 108-fold into fresh medium and incubation at 105 Pa CO.

Cell yield was determined by filtration of triplicate cultures through nylon membranes (0.22-μm pore size; Millipore) and drying of the membranes under vacuum at 40°C to weight constancy. Controls employing plain medium were used to correct the values for salt content.

Determination of Metabolites. CO, CO2, CH4, and H2 concentrations were measured by GC at 130°C on a Hewlett–Packard gas chromatograph (5890 Series II) with thermal conductivity detection. A stainless steel 60/80 Carboxen-1000 column (Supelco) with either He or Ar as the carrier gas (Ar when H2 concentration was to be ascertained) was used for these determinations. Acetate concentrations were determined by using the Acetic Acid UniFlex Reagent kit (Unitech Scientific, Lakewood, CA). Formate dehydrogenase (FDH) from yeast (Sigma) was used to quantify formate by following reduction of NAD+ to NADH as described in ref. 24. To identify unknown CO-derived metabolites, cell suspensions were incubated with 13CO (Sigma). The gas phase subsequently was analyzed by coupled GC–MS by using an HP6890 GC system equipped with an HP5973 mass selective detector (both from Hewlett–Packard). A Carbon-Plot capillary column (30 m, 0.32-mm inner diameter; Agilent Technologies, Colorado Springs, CO) was used at a 1.3 ml/min He flow rate at 50°C. The supernatant of these suspensions was analyzed by 13C NMR conducted on a Varian Unity 500 NMR spectrometer (125-MHz 13C) equipped with a 5-mm QUAD-probe (Nalorec Cryogenics, Martinez, CA). Spectra were recorded in proton-decoupling mode for 233 acquisitions at acquisition times of 1.086 s. D2O was added at 15% final concentration, and an external reference of 10 mM sodium [2-13C]acetate set at 24.6 ppm was used. [13C]formic acid and [13C2]acetic acid were from Aldrich.

Cell-Suspension Assays. For quantification of metabolic products, cells were harvested in the late-logarithmic growth phase by centrifugation and washed with assay buffer [50 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)/400 mM NaCl/13 mM KCl/54 mM MgCl2/2 mM CaCl2/2.8 mM cysteine·HCl/0.4 mM Na2S]. The cell pellet was resuspended in the same buffer containing 20 μg of puromycin per ml to a concentration of 1 × 109 cells per ml. A 2-ml quantity of the cell suspension was transferred to Balch tubes (Bellco Glass) and supplemented with the desired substrate after exchanging the atmosphere with He. The tubes were incubated on a roller drum (New Brunswick Scientific) at 37°C for 48 h. Analysis of metabolites was conducted as described above.

Enzymatic Assays. All steps were carried out under anaerobic conditions. Crude extract of M. acetivorans was prepared from cultures at late-logarithmic growth phase. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed in substrate-free high-salt medium, and lysed in assay buffer containing RNase A and DNase I (0.1 μg/ml). The assay buffer consisted of 40 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 2 mM DTT. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 × g, and the supernatant was used for enzymatic assays. CODH activity was determined by following CO-dependent methylviologen (MV) reduction at 603 nm (ε603 = 11.3 mM-1·cm-1) as described in ref. 25. FDH activity was measured essentially as reported in ref. 26 by formate-dependent MV reduction under the same conditions as for CODH. Nonspecific MV-reduction activity was measured independently by omitting an electron donor and was used for correction of the specific CODH and FDH activities. Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (27) by using BSA as standard.

Results

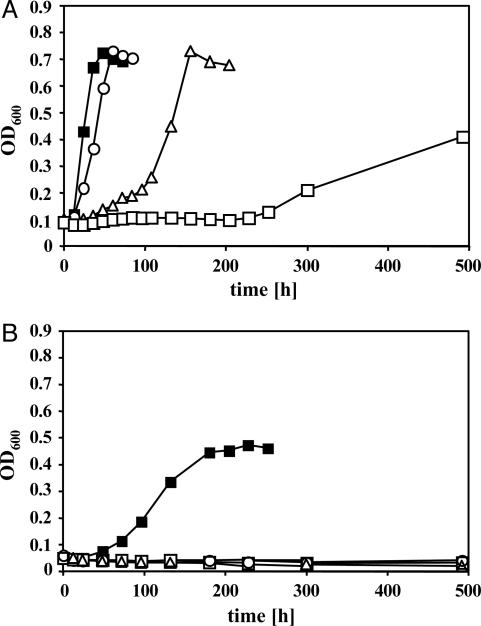

Effect of CO on Growth of M. acetivorans. Cultures that had been propagated on methanol or acetate were diluted into the same medium and concomitantly challenged with various amounts of CO (Fig. 1). When methanol served as the growth substrate, increasing partial pressures of CO in the headspace of the culture led to increased lag times before growth started (Fig. 1A). However, generation time and final cell yield were only marginally affected in the presence of 5 × 103 Pa and 2 × 104 Pa of CO, respectively. It was found that 5 × 104 Pa of CO was somewhat inhibitory for growth on methanol. In contrast, even small amounts of CO (5 × 103 Pa) completely inhibited growth on acetate, indicating that aceticlastic methanogenesis is more prone to inhibition by CO than is methylotrophic methanogenesis (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effect of CO on methylotrophic and aceticlastic growth of M. acetivorans. Cells pregrown on methanol (A) or acetate (B) were diluted into the same respective medium containing 2 × 102 Pa of N2/CO2 (80:20) in the gas phase and supplemented with various amounts of CO. Growth was monitored at 600 nm. CO levels: ○, 5 × 103 Pa; ▵, 2 × 104 Pa; □, 5 × 104 Pa; ▪, control with no CO. Growth curves were obtained by averaging three independent experiments.

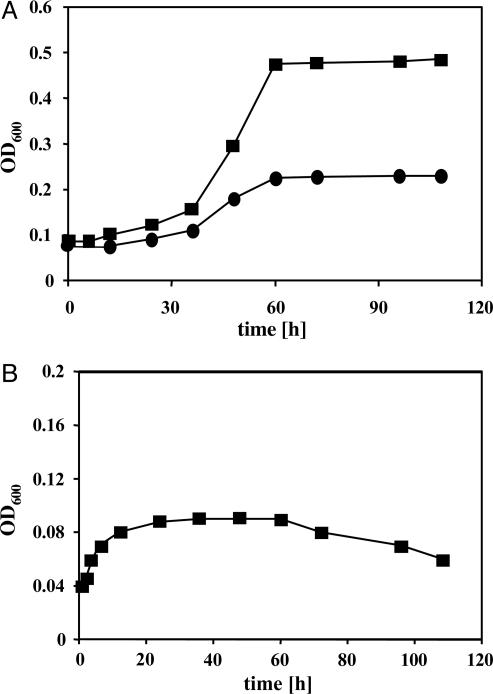

In light of these findings, cells pregrown on methanol, rather than on acetate, were used for adapting M. acetivorans to CO as the sole energy source. Over the course of several transfers, the amount of CO supplemented was successively increased to 105 Pa. Under these conditions, the CO-adapted strain had a minimal generation time of ≈24 h and reached cell densities of 0.5 at 600 nm (Fig. 2A). When CO was supplemented to 5 × 104 Pa, M. acetivorans grew more slowly, and the culture reached only about half the optical density compared with 105 Pa (Fig. 2A), indicating that CO was the limiting nutrient in these cultures. The apparent cell yield was determined as 2.5 ± 0.2 g/mol of CO, which is in the same range as for carboxidotrophic acetogenesis of Butyribacterium methylotrophicum (3 g/mol) (28).

Fig. 2.

CO-dependent growth of M. acetivorans. Cells were adapted to CO (see Materials and Methods) and diluted into fresh medium in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 5 mM BES. Growth was monitored at 600 nm. CO levels: •, 5 × 104 Pa; ▪, 105 Pa.

Stationary-phase CO-grown cells had little tendency to lyse and could be diluted and grown with only a short lag phase after storage at room temperature for several months. We conclude that growth on CO requires adaptation, rather than mutation, because CO-grown cultures require readaptation after growth on other substrates.

Methanogenesis Is Required for Growth of M. acetivorans on CO. When cultures were supplemented with BES, a potent inhibitor of methanogenesis that effectively inhibits growth of M. acetivorans on methanol (data not shown), an initial increase in cell density (corresponding to approximately one cell-doubling) was observed within the first 24 h; however, no further growth was observed (Fig. 2B).

M. acetivorans Produces Acetate and Formate from CO. Initial experiments to correlate the amounts of CO consumed and CH4 generated showed that in M. acetivorans the ratio of CO to CH4 deviated far from the expected 4 mol of CO consumed per 1 mol of methane (Eq. 1; data not shown), indicating the formation of other metabolic products from CO.

|

[1] |

To rigorously identify the products of CO metabolism, resting cells of CO-grown cultures were incubated with 13C-labeled CO. The gas phase was subsequently analyzed by coupled GC–MS that revealed only labeled CH4, CO2, and CO (data not shown). This result suggests that conversion of CO to CH4 proceeds via initial oxidation of CO to CO2, followed by reduction of CO2 to CH4. When the aqueous products from this reaction were analyzed by 13C NMR, two doublets at ≈24 and ≈179 ppm and one singlet at 172 ppm were detected (Fig. 3D). Comparison with spectra from authentic compounds indicated that the two doublets (24 and 179 ppm) correspond to the methyl and carboxyl groups of acetic acid, respectively (Fig. 3C). The observation of doublets (caused by coupling of the 13C signals by means of 13C–13C bonds), rather than singlets, indicates that both the methyl and the carboxyl group of acetate derive from 13CO. The signal at 172 ppm displayed a chemical shift identical to that of formic acid and was not split into a doublet because formate contains no C–C bonds (Fig. 3B). The identity of both acetate and formate was confirmed by enzymatic assay; acetate concentration was determined by a coupled enzymatic assay employing acetyl-CoA synthase; formate was quantified by using FDH.

Fig. 3.

13C NMR analysis of soluble products from carboxidotrophic metabolism of M. acetivorans. Spectrum A, cell-suspension assay buffer. Spectrum B, 10 mM [13C]formic acid in cell-suspension assay buffer. Spectrum C, 10 mM [13C2]acetic acid in cell-suspension assay buffer. Spectrum D, cell-suspension supernatant of nongrowing, CO-adapted M. acetivorans incubated in the presence of 13CO under a He atmosphere for 48 h. All spectra are offset by 5 ppm.

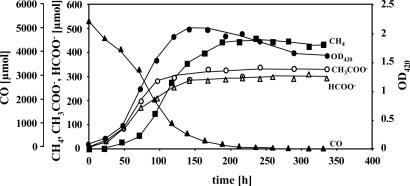

The consumption of CO and the production of methane, acetate, and formate by M. acetivorans were subsequently quantified during growth (Fig. 4). Acetate and formate were the major metabolites during logarithmic-phase growth. About 10 mM acetate and 8 mM formate accumulated in the culture supernatant under the growth conditions used. Notably, less then 10% of the CO consumed was used for CH4 production during the first 73 h of growth, when the CO level was still high. At this time point the growth yield was calculated to be 295 ± 26 g/mol of methane produced. This yield is in vast excess of the levels seen during growth of Methanosarcina species on H2/CO2 (5.4–6.4 g/mol of methane produced) (29) or methanol (5.1 g/mol of methane produced) (30). Thus, it is clear that under these conditions M. acetivorans predominantly generates energy for growth by processes other than methanogenesis. H2 was detected in trace amounts only, suggesting that it is not a metabolic intermediate (data not shown). Methane production surpassed acetate/formate production only when the majority of the CO had been used. As the culture reached stationary phase, synthesis of acetate and formate ceased, and methane was the main metabolic end product. Neither acetate nor formate was remetabolized within 12 days after growth had stopped. It should be noted that in this experiment, only about two-thirds of the CO used was converted to methane, acetate, and formate. We assume that the remainder was oxidized to CO2 (not measured here) to provide the reducing equivalents needed for biomass production and to provide the maintenance energy that would be needed over this prolonged experiment.

Fig. 4.

Metabolic conversions of CO during growth of M. acetivorans. Cells were grown in bicarbonate-buffered high-salt medium under a N2/CO2 (80:20) headspace with continuous agitation. Metabolites were determined as stated in Materials and Methods.AnOD420 of 1.0 corresponds to a dry weight of 0.41 ± 0.07 mg/ml of culture, under the culture conditions used here.

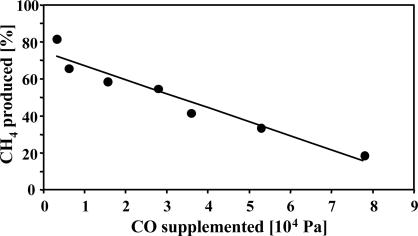

CO Inhibits Methanogenesis of M. acetivorans. To eliminate the variables associated with growth experiments, we also quantified substrate consumption and product formation in nongrowing cells in the presence of a protein-synthesis inhibitor. The substrate and products were balanced under all conditions; however, different CO partial pressures resulted in different stoichiometries of CH4, CO2, acetate, and formate (see Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Accordingly, increasing partial pressures of CO resulted in increased acetate and formate production and decreased CH4 production (Fig. 5). At ≈105 Pa of CO, only 5% of the CO was converted to CH4, which is 20% of the maximal theoretical value (assuming CH4 as the sole product). These data suggest that CO inhibits methanogenesis in M. acetivorans. Notably, the turnover of CO also decreased with increasing CO partial pressures. When methanogenesis was completely inhibited by BES, acetate and formate were still produced, albeit at low levels (data not shown), possibly because the cells reached the capacity for formation of acetate and formate under these conditions.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of methane production from CO by CO. Cell-suspension assays were conducted as described in Materials and Methods. Values are given in Table 1. The ratio of the observed amount of methane produced and the maximal theoretical amount of methane produced (based on a 4:1 ratio of CO to CH4; Eq. 1) expressed in percent were plotted against the partial pressures of CO.

Pta and Ack Are Required for CO Metabolism of M. acetivorans. Previously, mutants of M. acetivorans were isolated in which the operon encoding Pta and Ack had been disrupted by insertion of a transposon (23). These strains grow well in medium containing methanol but are incapable of growth on acetate, which is metabolized via the Ack/Pta pathway in Methanosarcina species (31). Further, as described above, acetogenic bacteria produce acetate via the Ack/Pta pathway. With these facts in mind, we examined the ability of the M. acetivorans pta-ack mutants to grow on CO. Neither of the pta-ack mutants grew on CO, indicating that acetogenesis from CO and methanogenesis from acetate both require the Ack/Pta pathway. Furthermore, acetogenesis via this pathway appears to be essential for growth of M. acetivorans on CO.

CODH Activity Is Up-Regulated During Growth on CO. To gain more insight into the mechanisms underlying CO utilization in M. acetivorans, crude extracts of methanol-grown and CO-grown cells were tested for CODH and FDH activity, respectively. The apparent CODH activity was ≈3-fold higher in CO-grown cells (4.0 ± 0.27 units; 1 unit = 1 μmol per min per mg of protein) than in methanol-grown cells (1.3 ± 0.10 units), indicating a role for CODH in the CO metabolism of M. acetivorans. On the other hand, FDH activity could not be detected in extracts derived from cells grown on either substrate. Although this negative result should be interpreted with caution, it suggests that formate production is not catalyzed by a known class of FDH.

Discussion

All methanogens examined to date employ methanogenesis for energy conservation; nevertheless, the evidence presented here indicates that M. acetivorans is able to employ the acetyl-CoA pathway as an alternative to the methanogenic pathway to conserve energy for growth: (i) M. acetivorans grows comparably fast (doubling time ≈24 h) in the presence of high partial pressures of CO. Both Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus and M. barkeri grow much more slowly on this substrate (doubling time > 200 h and 65 h, respectively) (16, 17). Furthermore, increased partial pressure of CO inhibits their growth, whereas the growth rate of M. acetivorans increased with the amount of CO supplemented. (ii) High partial pressures of CO inhibit methanogenesis in M. acetivorans, which argues for alternative methods of energy conservation to sustain growth. (iii) Substantial amounts of acetate and formate were accumulated during carboxidotrophic growth. These metabolites are not known to be produced in large quantities by other methanogens. They are, however, rather common metabolites for homoacetogens and other anaerobes (12, 32, 33). Homoacetogenic bacteria convert CO to acetate through the acetyl-CoA pathway (12), which involves reduction of CO2 to methyltetrahydrofolate (CH3-H4F), an enzyme-bound carbonyl moiety ([CO]), and CoA. Acetyl-CoA formation is catalyzed by the CODH/acetyl-CoA synthase complex (34, 35). Acetyl-CoA subsequently is converted to acetate by Pta and Ack, generating ATP by substrate-level phosphorylation (14, 15). (iv) Pta and Ack are essential for growth on CO in M. acetivorans, strongly suggesting that acetate is generated via acetyl-CoA. Presumably, the conversion of acetyl phosphate to acetate is coupled to ATP synthesis by substrate-level phosphorylation in this organism, as well.

The ΔG°′ for the formation of acetate from CO is only somewhat less than ΔG°′ for the formation of methane from CO (Eqs. 1 and 2; all values calculated from ref. 36). Because CO apparently inhibits methanogenesis in M. acetivorans, it seems likely that the organism has evolved the ability to take the alternative metabolic route of acetogenesis under conditions in which methanogenesis cannot proceed at its maximal rate, thus enabling the cells to reduce the level of CO and conserve energy at the same time. This capacity for acetogenesis greatly extends our knowledge of the metabolic versatility of methanogens. Previously, the acetyl-CoA pathway was thought to be used by these organisms only for anabolic CO2 reduction (37).

|

[2] |

|

[3] |

It is striking that M. acetivorans can grow both acetogenically and acetotrophically. Interestingly, this capability is similar to that of the syntrophic, acetate-oxidizing bacterium described by Zinder and Lee (38) that grows, depending on culture conditions, either acetogenically or acetotrophically. The finding that Ack and Pta are essential in M. acetivorans under both growth conditions indicates common enzymatic steps. However, growth on acetate is completely inhibited by even small amounts of CO. The reason aceticlastic growth is inhibited at much lower CO concentrations than is methylotrophic growth could be that formation of CH3-tetrahydrosarcinapterin (H4SPT), [CO], and CoA from acetyl-CoA is a reaction operating close to the thermodynamic equilibrium under physiological conditions (39). Alternatively, utilization of CO could depend on additional factors not present in the cells during growth on acetate.

To date, all methanogens capable of growing with CO have been shown to produce, at least transiently, hydrogen gas in addition to methane (5, 16, 17). In these organisms, the oxidation of CO to CO2 by CODH is coupled to the reduction of ferredoxin (40), which serves as the electron donor to reduce protons to H2 (41). The H2 generated subsequently serves as an electron donor to reduce CO2 to methane (42). M. acetivorans is unable to grow with hydrogen gas as the electron donor (18). Our data indicate that the inability of M. acetivorans to use H2/CO2 as a growth substrate is not caused by its inability to reduce CO2 to CH4, because CO2 reduction can proceed when CO serves as the electron donor. Rather, the absence of a functioning hydrogenase system in this organism is likely responsible for its inability to use H2 for growth (18); this hypothesis is supported by the very low levels of hydrogenase activity found in this organism (19). Furthermore, the deficiency in H2 metabolism may enable M. acetivorans to use CO more efficiently than with concomitant production of H2, which would escape from this organism that does not grow as multicellular aggregates (18).

Despite the generation of acetate and formate, methanogenesis is still required for growth on CO, because the potent methyl-coenzyme M (CoM) reductase inhibitor BES abolished growth on CO. Interestingly, BES-inhibited cells were able to continue to grow for about one generation. This observation is reminiscent of a report by Schönheit and Bock (43) demonstrating that a mutant strain of M. barkeri could grow by fermentation of pyruvate to acetate and H2 in BES-supplemented medium. However, this nonmethanogenic growth ceased after six to eight generations and could not be maintained indefinitely (43). In both M. barkeri and M. acetivorans, the reason for growth cessation under nonmethanogenic conditions is unclear; however, in both cases it may be explained by deprivation of a compound (or compounds) derived from the methanogenic pathway that would also be required for some other metabolic process. For example, a CoM/coenzyme B-dependent fumarate reductase has been isolated from Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus (44, 45). Both coenzymes are regenerated from the heterodisulfide in the last step the methanogenic pathway (1). We have not yet identified which step in the methanogenic pathway is inhibited by CO, although it cannot be any step involved in the reduction of CO2 to methyltetrahydrosarcinapterin, because these steps also are required for acetogenesis. Further investigations clearly are needed to clarify both the inhibited step and the reasons behind the inability to grow nonmethanogenically.

The role of the formate in CO metabolism, as well as the mechanism by which it is produced, is also unclear at present. M. acetivorans previously was shown to be incapable of growth on this energy-rich substrate (18). However, it is conceivable that formate production could be coupled to energy conservation. The standard free energy of formate formation from CO (Eq. 3) is sufficient for ATP synthesis by a chemiosmotic mechanism. Alternatively, formate production also could serve as a means for detoxification of CO, i.e., to lower the CO concentrations to levels at which methanogenesis again becomes favorable. Whether formate formation is thus a mere “electron sink” to regenerate oxidized ferredoxin produced by CODH or is the product of an energy-conserving process demands detailed investigations in the future.

The mechanism of formate production also remains elusive. Our biochemical data suggest that the presence of a clostridial-type ferredoxin-dependent FDH (46) in M. acetivorans is unlikely because formate-dependent methylviologen reduction could not be detected in extracts of either CO-grown cells (this study) or acetate-grown cells (47). Furthermore, no homologs of FDH are encoded in the genome of M. acetivorans (20). Instead, formate could be generated by hydrolysis of formyl methanofuran, an intermediate in the methanogenic pathway. Precedence for this reaction is found in the methylotrophic bacterium Methylobacterium extorquens (48). Alternatively, the molybdenum-containing formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase (FMD) from M. barkeri Fusaro was shown to slowly oxidize formate (49). Both a molybdenum- and a tungsten-containing FMD are encoded in the M. acetivorans chromosome (20). Thus, given the oxidation of formate by homologous enzymes, it may be that one or both of these FMDs could be responsible for the generation of formate from CO.

Finally, it is important to note that the ability to employ alternative metabolic routes under conditions unfavorable for methanogenesis may be a selective advantage for M. acetivorans in its natural habitat. This organism was isolated from a bed of decaying kelp in Monterey Bay, CA. These giant algae are known to accumulate up to 10% CO in their float cells (18, 50, 51). Therefore, CO can be considered as both a natural substrate for this organism and a compound that might be present during the metabolism of other methanogenic substrates. The ability to metabolize CO nonmethanogenically could reflect adaptation to environments with elevated CO concentrations where methane production is inhibited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to K. S. Suslick (University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign) for providing the GC–MS equipment. We thank A. Eliot and V. Mainz for help with the NMR studies. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant RO 2445/1-1 (to M.R.) and Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-02ER15296 (to W.W.M.).

Author contributions: M.R. and W.W.M. designed research; M.R. performed research; M.R. and W.W.M. analyzed data; and M.R. and W.W.M. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: Ack, acetate kinase; BES, 2-bromoethanesulfonic acid; CODH, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase; FDH, formate dehydrogenase; Pta, phosphotransacetylase.

References

- 1.Thauer, R. K., Hedderich, R. & Fischer, R. (1993) in Methanogenesis, ed. Ferry, J. G. (Chapman & Hall, New York), pp. 209-252.

- 2.Keltjens, J. T. & Vogels, G. D. (1993) in Methanogenesis, ed. Ferry, J. G. (Chapman & Hall, New York), pp. 253-303.

- 3.Ferry, J. G. (1993) in Methanogenesis, ed. Ferry, J. G. (Chapman & Hall, New York), pp. 304-334.

- 4.Hippe, H., Caspari, D., Fiebig, K. & Gottschalk, G. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 494-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krzycki, J. A., Wolkin, R. H. & Zeikus, J. G. (1982) J. Bacteriol. 149, 247-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker, H. A. (1956) Bacterial Fermentations (Wiley, New York).

- 7.Wolfe, R. S. (1993) in Methanogenesis, ed. Ferry, J. G. (Chapman & Hall, New York), pp. 1-32.

- 8.Belay, N. & Daniels, L. (1988) Antonie Leeuwenhoek 54, 113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liebl, K. H. & Seiler, W. (1976) in Proceedings of the Symposium on Microbial Production and Utilization of Gases, eds. Schlegel, H. G., Gottschalk, G. & Pfennig, N. (Goltze, Göttingen, Germany), pp. 215-229.

- 10.Uffen, R. L. (1976) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73, 3298-3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonam, D., Lehman, L., Roberts, G. P. & Ludden, P. W. (1989) J. Bacteriol. 171, 3102-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ljungdahl, L. G. (1994) in Acetogenesis, ed. Drake, H. L. (Chapman & Hall, New York), pp. 63-87.

- 13.Müller, V. & Gottschalk, G. (1994) in Acetogenesis, ed. Drake, H. L. (Chapman & Hall, New York), pp. 127-156.

- 14.Drake, H. L., Hu, S. I. & Wood, H. G. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 11137-11144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaupp, A. & Ljungdahl, L. G. (1974) Arch. Microbiol. 100, 121-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Brien, J. M., Wolkin, R. H., Moench, T. T., Morgan, J. B. & Zeikus, J. G. (1984) J. Bacteriol. 158, 373-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniels, L., Fuchs, G., Thauer, R. K. & Zeikus, J. G. (1977) J. Bacteriol. 132, 118-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sowers, K. R., Baron, S. F. & Ferry, J. G. (1984) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47, 971-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovely, D. R. & Ferry, J. G. (1985) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49, 247-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galagan, J. E., Nusbaum, C., Roy, A., Endrizzi, M. G., Macdonald, P., FitzHugh, W., Calvo, S., Engels, R., Smirnov, S., Atnoor, D., et al. (2002) Genome Res. 12, 532-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sowers, K. R., Boone, J. E. & Gunsalus, R. P. (1993) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 3832-3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metcalf, W. W., Zhang, J. K., Shi, X. & Wolfe, R. S. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 5797-5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang, J. K., Pritchett, M. A., Lampe, D. J., Robertson, H. M. & Metcalf, W. W. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9665-9670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Höpner, T. & Knappe, J. (1974) in Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, ed. Bergmeyer, H. U. (Verlag Chemie, Weinheim, Germany), Vol. 3, pp. 1551-1555. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasche, M. E., Terlesky, K. C., Abbanat, D. R. & Ferry, J. G. (1995) in Archaea: A Laboratory Manual, eds. Robb, F. T., Place, E. R., Sowers, K. R. & Schreier, H. J. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), Vol. 3, pp. 231-235. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schauer, N. L. & Ferry, J. G. (1995) in Archaea: A Laboratory Manual, eds. Robb, F. T., Place, E. R., Sowers, K. R. & Schreier, H. J. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), Vol. 3, pp. 221-224. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradford, M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72, 248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynd, L., Kerby, R. & Zeikus, J. G. (1982) J. Bacteriol. 149, 255-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson, T. J. & Mah, R. A. (1983) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 46, 348-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith, M. R. & Mah, R. A. (1978) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 36, 870-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundie, L. L., Jr., & Ferry, J. G. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 18392-18396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bott, M. (1997) Arch. Microbiol. 167, 78-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart, C. S., Duncan, S. H. & Cave, D. R. (2004) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230, 1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ragsdale, S. W. & Kumar, M. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2515-2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindahl, P. A. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 2097-2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thauer, R. K., Jungermann, K. & Decker, K. (1977) Bacteriol. Rev. 41, 100-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ladapo, J. & Whitman, W. B. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 5598-5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, M. J. & Zinder, S. H. (1988) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54, 124-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thauer, R. K. (1998) Microbiology 144, 2377-2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terlesky, K. C. & Ferry, J. G. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 4075-4079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meuer, J., Bartoschek, S., Koch, J., Kunkel, A. & Hedderich, R. (1999) Eur. J. Biochem. 265, 325-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajagopal, B. S., Lespinat, P. A., Fauque, G., LeGall, J. & Berlier, Y. M. (1989) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55, 2123-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bock, A. K. & Schönheit, P. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177, 2002-2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bobik, T. A. & Wolfe, R. S. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 18714-18718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heim, S., Künkel, A., Thauer, R. K. & Hedderich, R. (1998) Eur. J. Biochem. 253, 292-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jungermann, K., Kirchniawy, H. & Thauer, R. K. (1970) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 41, 682-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelson, M. J. & Ferry, J. G. (1984) J. Bacteriol. 160, 526-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pomper, B. K., Saurel, O., Milon, A. & Vorholt, J. A. (2002) FEBS Lett. 523, 133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bertram, P. A., Karrasch, M., Schmitz, R. A., Bocher, R., Albracht, S. P. J. & Thauer, R. K. (1994) Eur. J. Biochem. 220, 477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chapman, D. J. & Tocher, R. D. (1966) Can. J. Bot. 44, 1438-1442. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abbott, I. A. & Hollenberg, G. J. (1976) Marine Algae of California (Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford, CA).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.