Abstract

Drosophila have been used as model organisms to explore both the biophysical mechanisms of animal magnetoreception and the possibility that weak, low-frequency anthropogenic electromagnetic fields may have biological consequences. In both cases, the presumed receptor is cryptochrome, a protein thought to be responsible for magnetic compass sensing in migratory birds and a variety of magnetic behavioural responses in insects. Here, we demonstrate that photo-induced electron transfer reactions in Drosophila melanogaster cryptochrome are indeed influenced by magnetic fields of a few millitesla. The form of the protein containing flavin and tryptophan radicals shows kinetics that differ markedly from those of closely related members of the cryptochrome–photolyase family. These differences and the magnetic sensitivity of Drosophila cryptochrome are interpreted in terms of the radical pair mechanism and a photocycle involving the recently discovered fourth tryptophan electron donor.

Cryptochromes are flavoproteins with a variety of functions1 including, it has been suggested, acting as the primary receptors in the light-dependent magnetic compass sense of migratory birds2,3. That this hypothesis has yet to be critically tested is testament, in part, to the challenges posed by genetic manipulation of wild songbirds. However, there is compelling evidence that cryptochromes mediate a range of magnetic field-dependent phenotypes in fruit flies: binary choices in mazes4,5,6, circadian timing7,8, locomotor activity8, geotaxis and gravitaxis9,10, seizure response11 and courtship activity12. Although these experiments, using transgenic flies, show that cryptochrome is essential for the magnetic responses, they do not rule out an essential but non-magnetic role upstream or downstream of the actual receptor. Here, we show that photo-induced electron transfer reactions in the purified cryptochrome from Drosophila melanogaster (DmCry) are sensitive to weak applied magnetic fields. This strengthens the case significantly for cryptochromes having a magnetic function in insect behaviour, and has a bearing on the search for reproducible effects of 50/60 Hz electromagnetic fields on human biology, in which cryptochromes have been implicated as possible targets13,14.

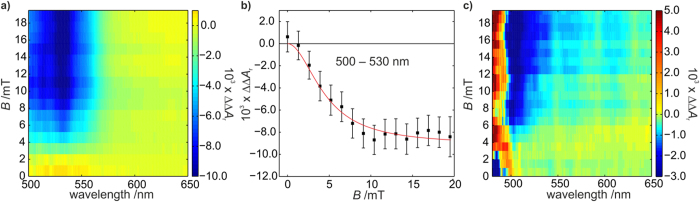

Light-dependent magnetic field effects in vitro have been reported for cryptochrome-1 from the plant Arabidopsis thaliana (AtCry1) and the closely related DNA photolyase from E. coli (EcPL)15,16. The magnetic responses of both molecules are explained by the radical pair mechanism3,17 and the photocycle in Fig. 1 which also provides a framework for the discussion of DmCry15. Photoexcitation of the fully oxidized form of the non-covalently bound flavin adenine dinucleotide cofactor (FADox) produces an excited singlet state (1FAD*) which is rapidly reduced by the transfer of an electron along a chain of three tryptophan residues (the “Trp-triad”) within the protein18. The net result is the radical pair 1[FAD•− TrpH•+] in which TrpH•+ is the radical form of the terminal, solvent-exposed, Trp residue and FAD•− is the flavosemiquinone radical. The superscript “1” indicates that the two unpaired electron spins, one on each radical, are initially in a spin-correlated singlet state. 1[FAD•− TrpH•+] either undergoes spin-allowed reverse electron transfer to regenerate the ground state (FADox + TrpH) or coherently interconverts with the corresponding triplet state, 3[FAD•− TrpH•+]15. Both singlet and triplet forms of this radical pair (denoted RP1) may additionally be converted into a secondary radical pair (RP2) in which, in the case of EcPL, the TrpH•+ radical has deprotonated to form the neutral radical, Trp•. The RP2 state of the protein is long-lived in vitro (typically milliseconds) and returns to the resting state by independent redox reactions of the two radicals19,20.

Figure 1. EcPL photocycle.

Photochemical reaction scheme for EcPL which provides a framework for discussing the photocycle of DmCry. The curly green arrows represent the magnetically-sensitive coherent interconversion of the singlet and triplet states of RP1. The photocycle of AtCry1 differs only in that RP2 is believed to contain the protonated radical FADH• rather than FAD•−.

Experiments on AtCry1 and EcPL revealed a field-dependent change in the quantum yield of RP2 that can be understood as follows15,21. Coherent interconversion of the singlet and triplet states of RP1 is driven by the hyperfine interactions of the electron spins with nearby 1H and 14N nuclear spins. The effect of an external magnetic field stronger than about 1 mT is to reduce the efficiency of singlet → triplet conversion, so favouring reverse electron transfer over the formation of RP215,21. In the context of magnetic sensing, it is assumed that the RP2 form of the protein is stabilised by independent reduction of the Trp• radical leading to a long-lived signalling state containing FAD•− which inherits the magnetic field effect3.

Here we report spectroscopic measurements of photo-induced FAD and Trp radicals in recombinantly expressed, purified DmCry. In brief, a combination of transient absorption and broadband cavity–enhanced absorption spectroscopy has been employed to explore the effects of external magnetic fields (of up to 22 mT) on the key species involved in the photocycle of DmCry. Details of these techniques can be found in refs 15 and 22. The protein concentration (ca. 50 μM), temperature (267–278 K) and glycerol content (ca. 50% for transient absorption measurements and 20% for the cavity-enhanced absorbance experiments) of the solutions were chosen to optimise the magnetic responses.

Results

Transient absorption measurements

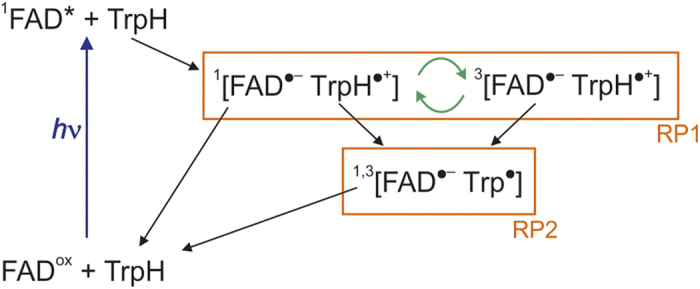

Figure 2a shows the time evolution of the transient absorption (ΔA) spectrum of DmCry following 10 ns pulsed photoexcitation at 450 nm. The instrumental response in the first 0.7 μs after the excitation pulse is unreliable due to scatter from the pump pulse and sample fluorescence. Immediately following this, the ΔA(λ) spectrum exhibits the characteristic signals of FAD•− (most clearly at λ < 420 nm, but also 500–560 nm) and TrpH•+ radicals (λ > 500 nm)23,24. The latter, in particular, is more pronounced for DmCry than in the case of AtCry1 and EcPL15. The corresponding depletion of the ground state FADox concentration is observed in the range 420–490 nm.

Figure 2. Transient absorption measurements.

(a) Transient absorption difference spectra [ΔA(λ)] of DmCry at different delay times after the photo-excitation laser pulse, showing ground-state bleaching (420 < λ < 480 nm) and radical production (λ > 500 nm). (b) Decay of the ΔA(λ) signal averaged over the spectral region 560–620 nm in the absence (black) and presence (red) of a 22 mT magnetic field. (c) Shows the corresponding magnetic field action response (red minus black, ΔΔA) displaying a rapid rise followed by a slow (τ = 36 ± 2 μs) decay. (d) Time response of the ΔA signal at 510 nm (recorded separately, with additional averaging) in the absence (black) and presence (red) of a 22 mT magnetic field. (e) The corresponding action signal shows a rapid rise in the magnetic field effect (complete within 10 μs) which is then long-lived. All transient absorption experiments were performed at 267 K in 50% v/v glycerol solution.

In the first 100 μs following excitation, the major change in the ΔA(λ) spectrum occurs in the wavelength range 520−650 nm and is assigned to the TrpH•+ → Trp• + H+ deprotonation reaction15,16,23. The kinetics of this change are bi-phasic (see Fig. 2b) with exponential time constants (fitted 560 < λ < 620 nm, 1–80 μs) of τ = 2.83 ± 0.16 μs (minor component) and τ = 35.9 ± 0.9 μs (major component ~90%). These decay rates are strongly dependent on the experimental conditions employed, especially the glycerol concentration. In the 10% glycerol solutions employed by Paulus et al.23, the decay in the absorbance in this spectral region is essentially complete within 10 μs (see Supporting Information, Fig. S3). Figure 2c shows the effect on the ΔA(λ) signal of a 22 mT magnetic field. The ΔΔA(λ) response to the magnetic field grows in rapidly (peaking at about −4% after a few microseconds) and then decays with a lifetime of 36 ± 2 μs consistent with the loss of TrpH•+.

Figure 2d shows the corresponding time-dependence of the ΔA(λ) signal measured at 510 nm where FAD•−, TrpH•+ and Trp• radicals all absorb. Here, a minor (ca. 10%) fraction of the ΔA(λ) signal decays within the first 10 μs leaving a substantial long-lived component. The effect of the magnetic field, as expected, is to suppress the formation of long-lived radicals, consistent with the formation of RP1 in a singlet state15,16. The ΔA(510 nm) response is qualitatively similar to that exhibited by AtCry1 and EcPL (Fig. 3 in ref. 15) but the short-lived component is significantly smaller for DmCry than for AtCry1. As shown in Fig. 2e, the −2% magnetic field effect at 510 nm grows in rapidly with complex kinetics but then persists without apparent decay for an extended period (≫100 μs) consistent with the long–lived radicals of RP2.

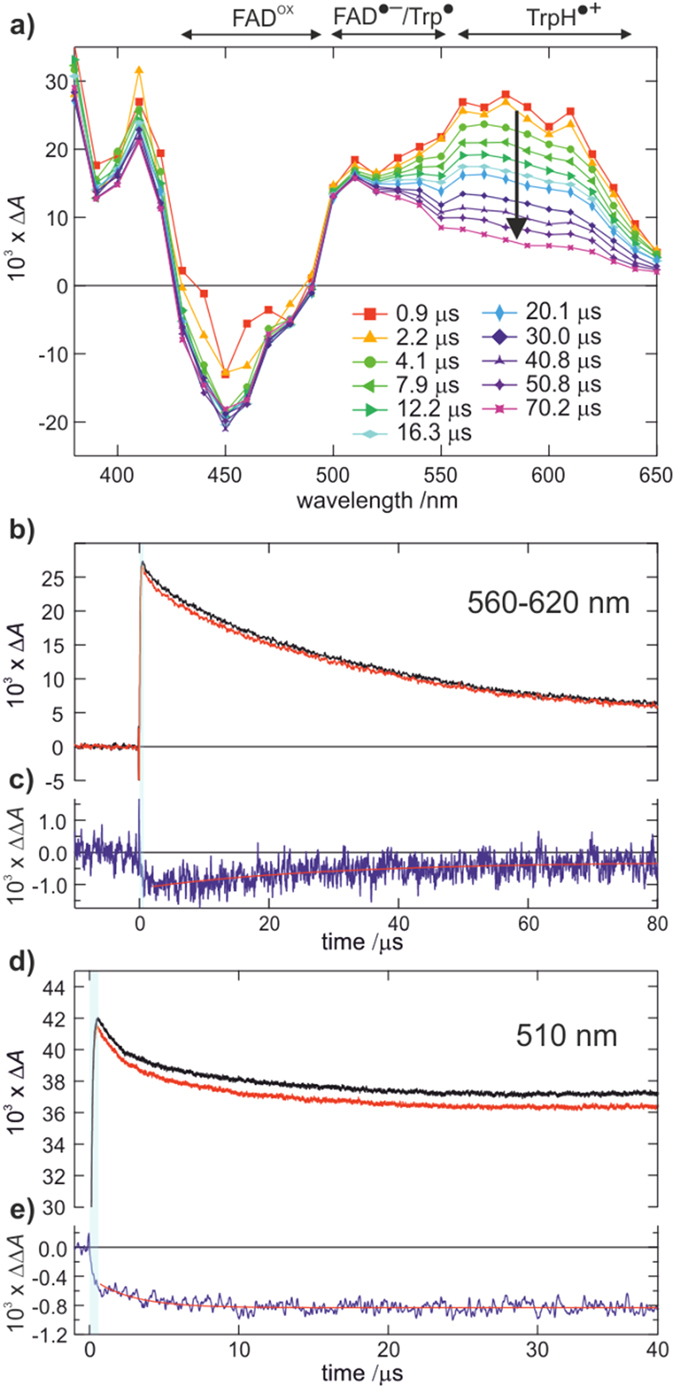

Figure 3. Broadband cavity-enhanced absorption spectra.

(a) BBCEAS response (ΔΔAr) of DmCry (60 μM in 20% v/v glycerol) as a function of the probe wavelength and the strength of the applied magnetic field. These effects correspond to changes in absorbance on the order of 10−6 (the subscript r indicates that the BBCEAS response has not been corrected for the cavity enhancement factor, see ref. 22). (b) Magnetic response profile determined by averaging over the wavelength region (500–530 nm) in which the long lived radicals absorb. The error bars represent one standard error of the mean. A B1/2 value of 4.5 ± 0.9 mT was determined from a Lorentzian fit to the data (red). (c) BBCEAS response of a 30 μM DmCry solution illustrating the commensurate (positive) magnetic field effect in the ground-state bleaching region (λ < 500 nm). All BBCEAS experiments were performed at 278 K.

Finally, in the region 440–450 nm, where the spectrum is dominated by the FADox ground-state bleach, the signal initially grows after excitation with a time constant τ = 1.9 ± 0.8 μs and then remains steady with no sign of appreciable recovery of FADox in the first 70 μs (see also Supporting Information).

Cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy

We have further explored the magnetic field effects in DmCry using a broadband (BB) version22 of cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy (CEAS). This method provides increased sensitivity by virtue of multiple passes of the probe light through the sample, albeit at the expense of temporal resolution. Figure 3a shows the change in the light-induced ΔΔA(λ) signal as a function of both detection wavelength and the field strength for a sample continuously excited at 450 nm. In this continuous–wave variant of BBCEAS, data were recorded with 50 ms integration times. The technique is thus relatively insensitive to the short-lived TrpH•+ radicals whose steady–state concentration is low and the observed signal is dominated by the long-lived RP2 radicals in the range 500–550 nm. As in Fig. 2, the magnetic field effect on Trp•, inherited from TrpH•+, has negative sign.

Despite the weak magnetic field effect exhibited by this system, BBCEAS provides sufficient sensitivity to record a magnetic response profile even at glycerol concentrations lower than used for the transient absorbance measurements (Fig. 3b). This represents a cross section through the data in Fig. 3a, averaged over the wavelength range 500–530 nm. As the field strength increases, so the response grows in magnitude, levelling out at around 15 mT. ΔΔA reaches 50% of its limiting value at a field, B1/2 = 4.5 ± 0.9 mT, markedly smaller than the 10–12 mT values observed for EcPL and AtCry1. No clear evidence for a low field effect15,25 (a phase inversion around 1 mT) is observed, but nor can a weak effect be ruled out.

The field-induced reduction in the yield of Trp radicals should be mirrored by a corresponding increase in the recovery of the ground state, FADox. This is indeed observed by BBCEAS as an increase in the absorbance below 500 nm when the protein concentration is reduced so as to increase the transmission of green/blue light (Fig. 3c).

Discussion

Our DmCry results show some striking similarities and differences when compared to AtCry1 and EcPL. The similarities are: (a) a [FAD•− TrpH•+] radical pair is initially formed in a singlet state; (b) the yields of long–lived FAD and Trp radicals show clear magnetic field effects consistent with the radical pair mechanism; (c) a change in the protonation state of one or more of the initial radicals (deprotonation of TrpH•+ in all three proteins, protonation of FAD•− in AtCry1)15 ensures a measurable magnetic field effect.

The differences (under comparable experimental conditions for the three proteins) are: (a) the magnetic field effect is markedly smaller for DmCry (ca. −2% at 510 nm and 22 mT) than for AtCry1 (ca. −20% at 270 K, 60% glycerol) and EcPL (ca. −7% at 265 K, 50% glycerol) at the same field15; (b) in 50% glycerol, the TrpH•+ → Trp• reaction is slower in DmCry (ca. 36 μs) than in EcPL (ca. 2 μs)15; (c) during the first 70 μs, there is no measurable recovery of FADox in DmCry compared to more than 50% recovery in both AtCry1 and EcPL15; (d) an additional fast (τ ≈ 3 μs) kinetic component is observed for DmCry.

These differences can be interpreted in the light of recently published work by Nohr et al. reporting the existence of a fourth tryptophan residue in DmCry that serves as the terminal electron donor26. Müller, Brettel, de la Lande and colleagues also find evidence for a “Trp-tetrad” in an animal (6–4) photolyase27,28. In contrast to AtCry1 and EcPL, where electron hopping stops at the third tryptophan (denoted TrpCH), TrpCH•+ in DmCry (W342) is reduced by a further electron transfer from a more distant residue, TrpD (W394), to give the radical pair [FAD•− TrpDH•+]. Under the experimental conditions of Nohr et al. (at the lower glycerol content of 10%), the fourth electron transfer is too fast to be resolved on a 0.1 μs timescale and the deprotonation of TrpDH•+ occurs with τ = 2.56 ± 0.06 μs26.

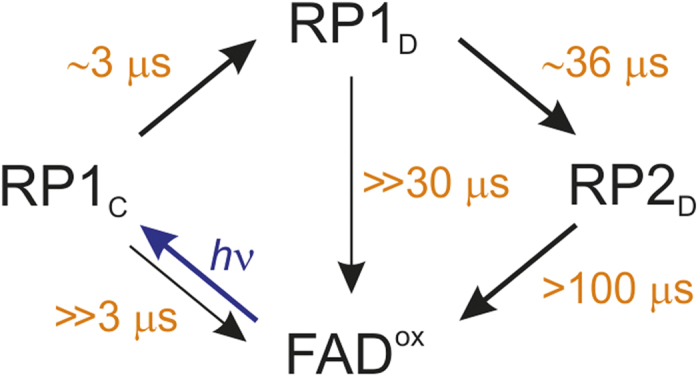

Our findings for DmCry can be understood in terms of the mechanism shown schematically in Fig. 4 if the following assumptions are made:

The observed TrpH•+ radical deprotonation (τ ≈ 36 μs) is that of TrpDH•+ (i.e. RP1D → RP2D), which is slower than that measured by Nohr et al. due to the differing experimental conditions (50% glycerol compared to 10% and 277 K rather than 267 K, see Supporting Information);

The electron transfer from TrpDH to TrpCH•+ (i.e. RP1C → RP1D) occurs with τ ≈ 3 μs;

Reverse electron transfer in both RP1C and RP1D is much slower than RP1C → RP1D and RP1D → RP2D, respectively;

TrpCH•+ and TrpDH•+ have slightly different optical absorption spectra and/or extinction coefficients as a result of differences in the solvent accessibilities of the two radical ions and/or the local distributions of charged and polar residues27,29;

As in AtCry1 and EcPL15, the only radical pair that produces magnetic field effects is RP1C. RP1D and RP2D are both too long-lived for spin-selective recombination to compete effectively with spin relaxation23,27,30.

Figure 4. Reaction scheme.

A simplified framework for interpreting the key kinetic and magnetic field effect data for DmCry assuming a tetrad of tryptophan residues. RP1C, RP1D, and RP2D represent radical pairs comprising FAD•− with TrpCH•+, TrpDH•+, and TrpD•, respectively. The bold arrows represent major pathways.

The lack of recovery of FADox in the transient absorption spectra is explained by assumption (c) which also accounts for the small magnetic field effect. The largest effects are expected when reverse electron transfer and radical (de)protonation occur with similar rate constants, as in AtCry1 and EcPL15.

Assumptions (b) and (d) account for the faster (τ ≈ 3 μs) of the two components observed at longer wavelengths (Fig. 2a) and may explain the short timescale behaviour below 500 nm.

Müller et al. have argued that the involvement of a fourth electron-donating Trp residue in animal cryptochromes casts doubt on whether a FAD–Trp radical pair could be the magnetoreceptor in animals27. Based on their measurements on Xenopus laevis (6–4) photolyase [Xl(6–4)PL], they contend (and we broadly agree) that reverse electron transfer in both RP1D and RP2D is too slow compared to the likely rate of electron spin relaxation to allow a significant magnetic field effect to be generated. However, if both the fourth electron transfer (RP1C → RP1D) and the reverse electron transfer in RP1C in DmCry were much slower than in Xl(6–4)PL, then magnetic field effects from RP1C would still be possible.

The magnetic field effect we have observed for DmCry amounts to only 2–4% in a magnetic field (22 mT) that is considerably stronger than used in many of the Drosophila magnetic behavioural assays4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. However, it is not unreasonable to think that the magnetic sensitivity of DmCry in vivo could be very different from that of the isolated protein in vitro. We have seen that the rate of TrpH•+ deprotonation is sensitive to the glycerol concentration and argue that the RP1C → RP1D electron transfer is similarly affected. Within a cellular environment, the protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions of DmCry could play a similar role, leading to larger effects at weaker magnetic fields than reported here.

In summary, an unambiguous magnetic field effect has been observed in the animal cryptochrome, DmCry, using transient absorption and broadband cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy. The field effect, which is observed in both the radical and the ground-state bleaching region, is considerably smaller than previously observed in the related AtCry1 and EcPL proteins. The complex observed kinetics have been characterised and the key features interpreted in the framework of the tryptophan tetrad for which independent evidence has recently emerged.

Methods

Protein preparation

Full-length DmCry was expressed and purified using procedures described in ref. 26. The protein samples were pre-treated with potassium ferricyanide as described previously21, to ensure that the FAD cofactor was in its fully oxidized state. Excess ferricyanide was removed by three consecutive ultrafiltration steps using 30-kDa membranes. Protein samples in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol were centrifuged for one hour before use to remove precipitates and aggregates. This is essential for the optical cavity experiments which are sensitive to scattering losses. Following purification, 60 μM protein solutions were made up to 20% v/v glycerol (BBCEAS) or 50% v/v glycerol (transient absorption) for the optical experiments.

In common with previous findings in studies of related protein systems15, the observed magnetic field effect in DmCry increases as the temperature is lowered from room temperature. In the transient absorbance experiments no field effect was observed at 282 K (see Supporting Information, Fig. S3) and it was necessary to work at 267 K. Glycerol prevents the solution from freezing and the increased light-scattering that would result. Higher glycerol concentrations, however, also lead to more viscous solutions slowing the diffusion process. Figure S3 in the Supporting Information illustrates the effect a reduction in the glycerol concentration has on the deprotonation of TrpDH•+. Cavity-enhanced absorption methods offer higher sensitivity and measureable magnetic field effects are observed at 278 K without the need for high glycerol concentrations.

Transient absorption spectroscopy

The transient absorption spectrometer is described in ref. 15. Protein solutions were excited at 450 nm using a Nd:YAG-pumped dye laser (Sirah Cobra, 5–9 mJ per 10 ns pulse). A repetition rate of 1/120 Hz was chosen to minimise sample photodegradation and allow time for the protein to return completely to the ground state between laser flashes. Extensive signal averaging was performed to achieve acceptable signal-to-noise in the spectra.

Unless otherwise stated, for transient absorption experiments, all cryptochrome solutions were prepared as 60 μM concentrations in 50 mM HEPES buffer, 100 mM KCl, 50% v/v glycerol and experiments performed at 267 K.

Broadband cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy

The use of cavity-enhanced spectroscopic techniques to study magnetic field effects has been described previously22,31,32. Protein solutions were prepared as 60 μM concentrations in 50 mM HEPES buffer, 100 mM KCl, 20% v/v glycerol and experiments were performed at 278 K. Condensation of water vapour onto the sample cell was prevented by blowing dry compressed air or nitrogen onto the faces of the cooled cell. The high sensitivity of the instrument allowed low photoexcitation powers to be used (500 μW at 450 nm), minimising protein photodegradation. All spectra were acquired at a repetition rate of 10 Hz with integration times of 50 ms.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Sheppard, D. M. W. et al. Millitesla magnetic field effects on the photocycle of an animal cryptochrome. Sci. Rep. 7, 42228; doi: 10.1038/srep42228 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Electromagnetic Fields Biological Research Trust, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (QuBE: N66001-10-1-4061), the European Research Council (under the European Union’s 7th Framework Programme, FP7/2007–2013/ERC Grant 340451), the US Air Force (USAF) Office of Scientific Research (Air Force Materiel Command, USAF Award FA9550-14-1-0095), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft RTG-1976 (project 13).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions D.M.W.S., J.L. and S.R.T.N. performed and analysed the CEAS measurements in Oxford. K.H.B. and K.M. performed and analysed the transient absorption experiments in Oxford. J.S. was involved in writing the data acquisition software for the experiments. The protein samples were expressed and purified in Freiburg by R.R., E.S., T.B. and S.W. P.J.H., C.R.T. and S.R.M. coordinated the research programme and prepared the manuscript following a first draft by DMWS.

References

- Chaves I. et al. The cryptochromes: blue light photoreceptors in plants and animals. Annu Rev Plant Biol 62, 335–364 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz T., Adem S. & Schulten K. A model for photoreceptor-based magnetoreception in birds. Biophys J 78, 707–718 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hore P. J. & Mouritsen H. The radical pair mechanism of magnetoreception. Ann Rev Biophys 45, 299–344 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegear R. J., Casselman A., Waddell S. & Reppert S. M. Cryptochrome mediates light-dependent magnetosensitivity in Drosophila. Nature 454, 1014–1018 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegear R. J., Foley L. E., Casselman A. & Reppert S. M. Animal cryptochromes mediate magnetoreception by an unconventional photochemical mechanism. Nature 463, 804–807 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley L. E., Gegear R. J. & Reppert S. M. Human cryptochrome exhibits light-dependent magnetosensitivity. Nat Commun 2, 356 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii T., Ahmad M. & Helfrich-Forster C. Cryptochrome mediates light-dependent magnetosensitivity of Drosophila’s circadian clock. PLoS Biol 7, 813–819 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele G. et al. Genetic analysis of circadian responses to low frequency electromagnetic fields in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genetics 10, e1004804 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J.-E. et al. Positive geotactic behaviors induced by geomagnetic field in Drosophila. Molec Brain 9, 55 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele G., Green E. W., Rosato E. & Kyriacou C. P. An electromagnetic field disrupts negative geotaxis in Drosophila via a CRY-dependent pathway. Nat Commun 5, 4391 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marley R., Giachello C. N. G., Scrutton N. S., Baines R. A. & Jones A. R. Cryptochrome-dependent magnetic field effect on seizure response in Drosophila larvae. Sci Rep 4, 5799 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-L., Fu T.-F., Chiang M.-H., Chang Y.-W., Her J.-L. & Wu T. Magnetoreception regulates male courtship activity in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 11, e0155942 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagroye I., Percherancier Y., Juutilainen J., Poulletier De Gannes F. & Veyret B. ELF magnetic fields: Animal studies, mechanisms of action. Prog Biophys Molec Biol 107, 369–373 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounds P. L. & Kuster N. Is cryptochrome a primary sensor of extremely low frequency magnetic fields in childhood leukemia? Biophys J 108, 562a (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K. et al. Magnetically sensitive light-induced reactions in cryptochrome are consistent with its proposed role as a magnetoreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 4774–4779 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goez M., Henbest K. B., Windham E. G., Maeda K. & Timmel C. R. Quenching Mechanisms and Diffusional Pathways in Micellar Systems Unravelled by Time-Resolved Magnetic-Field Effects. Chem Eur J 15, 6058–6064 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers C. T. & Hore P. J. Chemical magnetoreception in birds: a radical pair mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 353–360 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao Y. T. et al. Ultrafast dynamics and anionic active states of the flavin cofactor in cryptochrome and photolyase. J Am Chem Soc 130, 7695–7701 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattnig D. R. et al. Chemical amplification of magnetic field effects relevant to avian magnetoreception. Nat Chem 8, 384–391 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovani B., Byrdin M., Ahmad M. & Brettel K. Light-induced electron transfer in a cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptor. Nat Struct Biol 10, 489–490 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henbest K. B. et al. Magnetic-field effect on the photoactivation reaction of Escherichia coli DNA photolyase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 14395–14399 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil S. R. T. et al. Broadband cavity-enhanced detection of magnetic field effects in chemical models of a cryptochrome magnetoreceptor. J Phys Chem B 118, 4177–4184 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus B. et al. Spectroscopic characterization of radicals and radical pairs in fruit fly cryptochrome–protonated and nonprotonated flavin radical‐states. FEBS J 282, 3175–3189 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbacher T., Immeln D., Dick B. & Kottke T. Microsecond light-induced proton transfer to flavin in the blue light sensor plant cryptochrome. J Am Chem Soc 131, 14274–14280 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmel C. R., Till U., Brocklehurst B., McLauchlan K. A. & Hore P. J. Effects of weak magnetic fields on free radical recombination reactions. Mol Phys 95, 71–89 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohr D. et al. Extended electron-transfer in animal cryptochromes mediated by a tetrad of aromatic amino acids. Biophys J 111, 301–311 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P., Yamamoto J., Martin R., Iwai S. & Brettel K. Discovery and functional analysis of a 4th electron-transferring tryptophan conserved exclusively in animal cryptochromes and (6–4) photolyases. Chem Commun 51, 15502–15505 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cailliez F., Müller P., Firmino T., Pernot P. & de la Lande A. Energetics of photoinduced charge migration within the tryptophan tetrad of an animal (6–4) photolyase. J Am Chem Soc 138, 1904–1915 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernini C., Andruniów T., Olivucci M., Pogni R., Basosi R. & Sinicropi A. Effects of the protein environment on the spectral properties of tryptophan radicals in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Azurin. J Am Chem Soc 135, 4822–4833 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattnig D. R., Solov’yov I. A. & Hore P. J. Electron spin relaxation in cryptochrome-based magnetoreception. Phys Chem Chem Phys 18, 12443–12456 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil S. R. T. et al. Cavity enhanced detection methods for probing the dynamics of spin correlated radical pairs in solution. Mol Phys 108, 993–1003 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K. et al. Following radical pair reactions in solution: a step change in sensitivity using cavity ring-down detection. J Am Chem Soc 133, 17807–17815 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.