Abstract

Skeletal muscle plays important roles in whole-body energy homeostasis. Excessive skeletal muscle lipid accumulation is associated with some metabolic diseases such as obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. The energy sensor AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) is a key regulator of skeletal muscle lipid metabolism, but the precise regulatory mechanism remains to be elucidated. Here, we provide a novel mechanism by which AMPK regulates skeletal muscle lipid accumulation through fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO)-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine (m6A). We confirmed an inverse correlation between AMPK and skeletal muscle lipid content. Moreover, inhibition of AMPK enhanced lipid accumulation, while activation of AMPK reduced lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells. Notably, we found that mRNA m6A methylation levels were inversely correlated with lipid content in skeletal muscle. Furthermore, AMPK positively regulated the m6A methylation levels of mRNA, which could negatively regulate lipid accumulation in C2C12. At the molecular level, we demonstrated that AMPK regulated lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells by regulating FTO expression and FTO-dependent demethylation of m6A. Together, these results provide a novel regulatory mechanism of AMPK on lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle cells and suggest the possibility of controlling skeletal muscle lipid deposition by targeting AMPK or using m6A related drugs.

The incidence of obesity and Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is increasing worldwide1,2, so a better understanding of how ectopic fat deposition occurs remains urgent. Skeletal muscle plays essential roles in whole body energy homeostasis3 and insulin action4. Notably, excessive lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle is associated with the development of obesity and T2D5,6. Therefore, studying the underlying mechanism of skeletal muscle lipid metabolism may provide useful information for the treatment of obesity and T2D.

Lipid accumulation and energy metabolism in skeletal muscle are regulated by multiple factors. Genetically, obese mice (known as ob/ob and db/db mice) are observed to have greater skeletal muscle lipid7. High-fat diet feeding results in greater lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle8. In addition, slow myofibres have more intramuscular triglycerides (abbreviated as IMTG) than fast myofibres9, indicating that myofibre type is associated with IMTG accumulation. At the molecular level, substantial studies have revealed that several genes have considerable impacts on skeletal muscle lipid metabolism, including ATGL (adipose triglyceride lipase)10,11,12, HSL (hormone-sensitive lipase)13 and AMPK14,15,16,17,18,19. AMPK is recognized as a key energy sensor that can regulate energy status20. Activation of AMPK increases the level of glucose uptake in skeletal muscle16,17, enhances lipid oxidation and reduces fatty acid incorporation into triacylglycerol through phosphorylation of ACC2 (acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2) in skeletal muscle14,18. By contrast, ablation of AMPK reduces fatty acid oxidation and enhances skeletal muscle lipid accumulation and leads to elevated triglyceride content15. Furthermore, AMPK is able to facilitate skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and thus regulates the energy status of skeletal muscle cells19. However, more studies are needed to understand the regulatory mechanism of AMPK on skeletal muscle lipid accumulation.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), the most prevalent mRNA modification21, is involved in diverse biological processes including lipid accumulation and energy metabolism22,23. The m6A modification can be dynamically modulated by several genes, including the methyltransferases (METTL3, METTL14 and WTAP)24,25 and the demethylases (ALKBH5 and FTO)26,27. Depletion of FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated protein) results in an increased mRNA m6A level, while overexpression of FTO leads to a decreased m6A level. A subsequent study shows that FTO partially co-localizes with nuclear speckles (one organelles that are enriched in pre-mRNA splicing factors and located in the interchromatin nuclear space)28, implicating m6A in nuclear RNA as a physiological substrate of FTO26. Moreover, FTO dynamically regulates m6A level and plays a critical role in determining splicing and gene expression patterns23. It has been demonstrated that FTO is strongly associated with body mass and obesity29. Overexpression of FTO in mice increases fat mass and obesity, while loss of FTO protects mice from obesity30,31, suggesting a prominent role of FTO in body fat metabolism. A recent study provides evidence that FTO regulates 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation by demethylating m6A. In addition, knockdown of METTL3 (methyltransferase like 3) promotes 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation, which together links m6A methylation to adipogenesis23. More recently, we found that inhibition of mRNA m6A methylation enhanced adipogenesis, while increasing the mRNA m6A methylation level suppressed adipogenesis in porcine adipocytes22. Furthermore, we also observed that m6A is involved in the metabolic effects of betaine on adipose tissue and liver32,33. However, the effects of mRNA m6A methylation on lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle remain unclear. Furthermore, whether the AMPK pathway could affect FTO and m6A methylation is unknown.

Here, we provide a novel mechanism for AMPK in the regulation of skeletal muscle lipid accumulation through FTO-dependent demethylation of mRNA m6A. These results provide new insight into the role of AMPK and FTO in skeletal muscle lipid accumulation and implicate the possibility of controlling skeletal muscle lipid deposition using AMPK or m6A related drugs.

Results

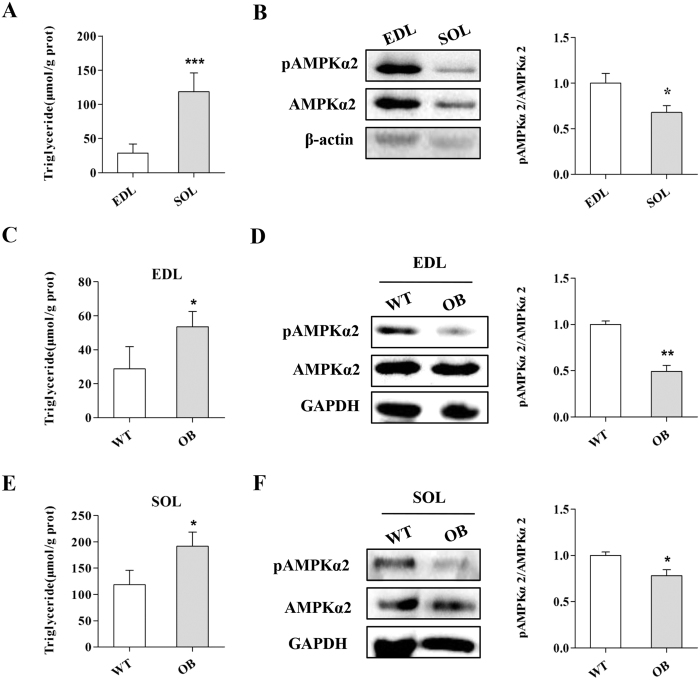

The phosphorylation of AMPKα is inversely correlated with lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle

Slow myofibres contain more IMTG than fast myofibres9. To confirm whether AMPK is associated with skeletal muscle lipid accumulation, we first measured the phosphorylation levels of AMPKα2 (p-AMPKα2), the predominant subunit of AMPK in skeletal muscle34, in the SOL (soleus; mostly slow myofibres) and EDL (extensor digitorum longus; mostly fast myofibres) of WT mice. Consistent with previous reports9, more TG content in SOL was found compared to EDL (Fig. 1A). Conversely, the p-AMPKα2 levels in SOL were lower than EDL (Fig. 1B), indicating that p-AMPK levels inversely correlate with skeletal muscle lipid content. The correlational analysis confirmed the inverse correlation between p-AMPK levels and lipid content in skeletal muscle (Fig. S1A).

Figure 1. The AMPK activity in skeletal muscle is inversely correlated with lipid content.

(A,B) The triglyceride content in SOL was much higher than EDL (A) while the p-AMPKα2 level in SOL was lower than EDL (B). (C,D) The EDL of OB mice contained more triglyceride (C) but a lower p-AMPKα2 level compared to WT mice (D). (E,F) The triglyceride content (E) and the p-AMPKα2 levels (F) in SOL of OB mice (F). The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. n = 4–6. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

OB mice or HFD fed mice have more lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle tissue7,8. To further confirm the correlation between AMPK and skeletal muscle lipid accumulation, we detected the p-AMPKα2 levels and TG content in OB mice. Notably, we found higher TG content but lower p-AMPKα2 levels in the skeletal muscle tissues of OB mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 1C–F). In addition, inverse correlations between the p-AMPKα2 levels and TG content were found in the EDL and SOL from OB mice (Fig. S1B and C) and HFD fed mice (Figs S2; S3).These results confirmed that the p-AMPKα level was inversely correlated with lipid content in skeletal muscle, suggesting that AMPK may negatively regulate lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle.

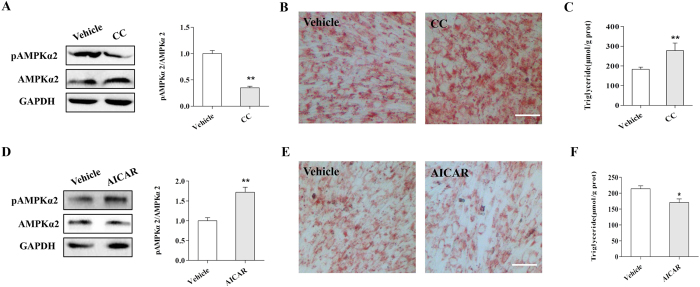

AMPK negatively regulates lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells

To directly address the effects of AMPK on lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle cells, we treated adipogenic-differentiated C2C12 cells with an AMPK inhibitor (Compound C) or activator (AICAR). We found that inhibition of AMPK with Compound C significantly decreased the level of p-AMPKα2 (Fig. 2A). In addition, ORO staining and TG measurement results showed that Compound C treatment dramatically elevated lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells (Fig. 2B,C). In contrast, activation of AMPK by AICAR upregulated the p-AMPKα2 level (Fig. 2D) but decreased lipid accumulation and TG content in C2C12 cells (Fig. 2E,F). Furthermore, inverse correlations were observed between the p-AMPKα2 levels and triglycerides in the CC and AICAR treatments (Fig. S4). Together, our results demonstrated that AMPK negatively regulated lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells.

Figure 2. AMPK negatively regulates lipid accumulation in C2C12 cells.

(A) The p-AMPKα2 level was significantly inhibited by Compound C. (B,C) ORO staining (B) and triglyceride content (C) in C2C12 cells treated withor without Compound C. (D) AICAR upregulates p-AMPKα2 expression in C2C12 cells. (E,F) ORO staining (E) and triglyceride content (F) in C2C12 cells treated withor without AICAR. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. n = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

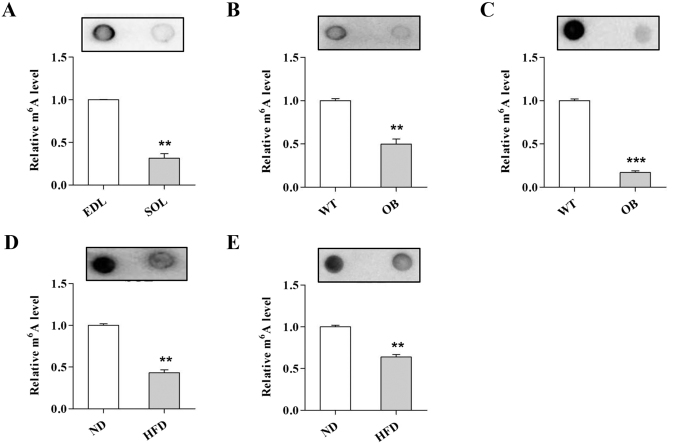

mRNA m6A methylation inversely affects skeletal muscle lipid accumulation

Recent studies provide evidence that mRNA m6A methylation regulates adipogenesis in adipocytes22,23. To examine whether m6A methylation affects skeletal muscle lipid accumulation, we first assessed m6A levels in slow SOL and fast EDL muscles. Notably, we found that the m6A levels in the SOL were much lower compared to the EDL of WT mice (Fig. 3A). Reduced m6A levels in the SOL (Fig. 3B) and EDL (Fig. 3C) of OB mice were observed. In addition, compared to the ND group, the SOL (Fig. 3D) and EDL (Fig. 3E) of the HFD group had lower m6A levels. These results indicated that mRNA m6A methylation might inversely regulate lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells.

Figure 3. The m6A methylation level is inversely correlated with skeletal muscle lipid content.

(A) The m6A level in the EDL and SOL. (B,C) The m6A level in the EDL (B) and SOL (C) of WT and OB mice. (D,E) The m6A level in the EDL (D) and SOL (E) of the ND and HFD group. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. n = 4–6. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

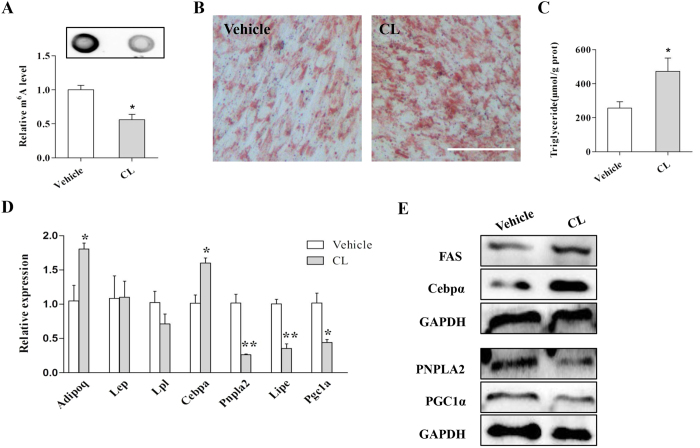

To address whether mRNA m6A methylation modulates lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle cells, we treated C2C12 cells with the methylation inhibitor cycloleucine. The mRNA m6A level was significantly decreased by cycloleucine treatment (Fig. 4A). The ORO staining and TG detection results showed much greater TG accumulation following cycloleucine treatment (Fig. 4B,C). Furthermore, real-time PCR analysis revealed that cycloleucine treatment upregulated the expression of the adipogenic gene Cebpα (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha) and decreased the expression of both lipolysis (Pnpla2 and Lipe) and mitochondrial genes (Pgc1α) (Fig. 4D). Western blot results further confirmed that inhibition of m6A methylation dramatically increased the protein levels of FAS (fatty acid synthase) and C/EBPα but decreased the protein levels of PNPLA2 and PGC1α (peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha) (Fig. 4E). These results indicated that mRNA m6A methylation increased lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells by affecting the expression of lipid metabolism related genes.

Figure 4. Inhibition of m6A methylationin C2C12 cells reduces cellular lipid accumulation.

(A) Cycloleucine treatment decreased the m6A level in C2C12 cells. (B) ORO staining of C2C12 cells treated with vehicle or cycloleucine. (C) Cycloleucine treatment increased cellular triglyceride content. (D,E) Cycloleucine treatment increased the mRNA levels of Cebpα but decreased the expression of pnpla2, Lipe, and Pgc1α (D), as well as the protein levels (E). CL, cycloleucine. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. n = 3. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. Scale bars: 100 μm.

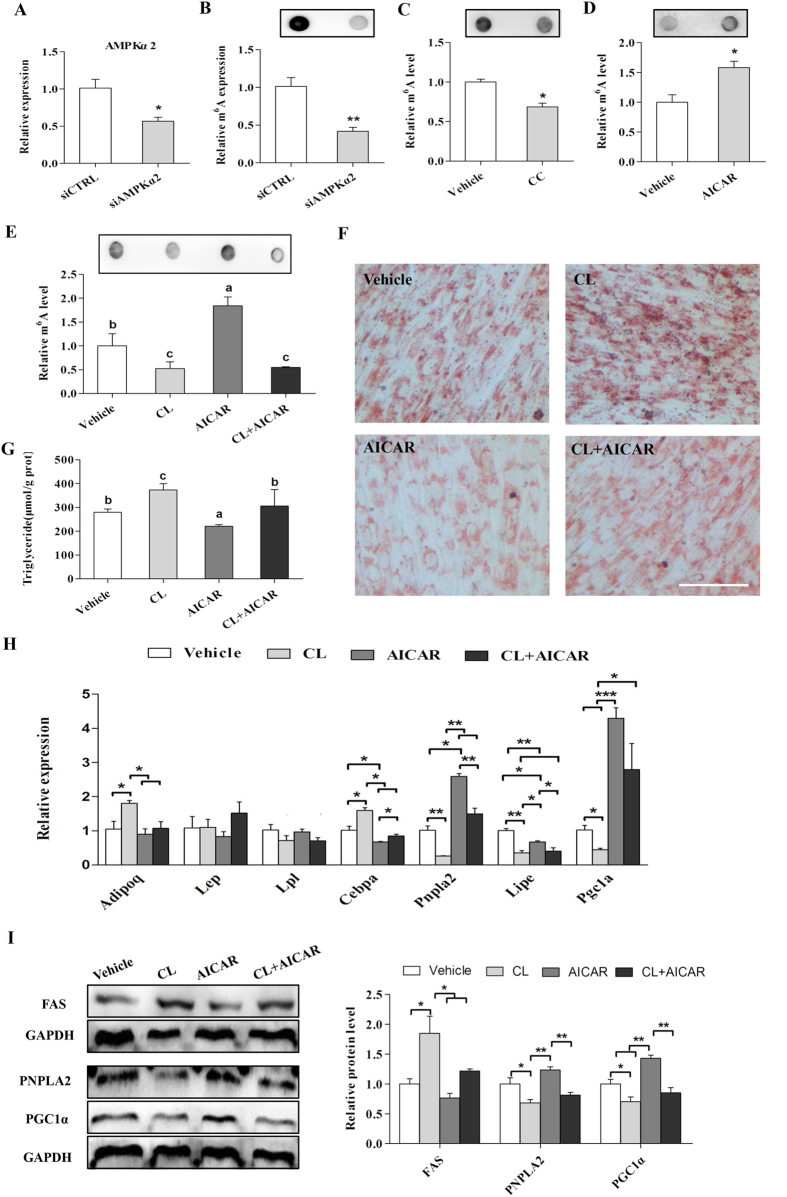

AMPK decreases lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells through upregulation of mRNA m6A methylation

Next, we determined the effects of AMPK on mRNA m6A methylation in skeletal muscle, as our previous study revealed the involvement of AMPK in the m6A methylation process in adipocytes33. Interestingly, we found that knockdown of AMPKα2 reduced the mRNA m6A level in C2C12 cells (Fig. 5A and B). A similar result was observed following Compound C treatment (Fig. 5C).By contrast, AICAR (an AMPK activator) treatment increased the mRNA m6A methylation level in C2C12 cells (Fig. 5D). These results combined with our previous reports suggest that AMPK upregulates m6A methylation in skeletal muscle cells.

Figure 5. AMPK affects cellular lipid accumulation by regulating m6A methylation in C2C12.

(A) The mRNA levels of AMPKα2 in C2C12 cells treated with AMPKα2 siRNA (siAMPKα2). (B–D) m6A methylation in C2C12 cells treated with siAMPKα2 (B), CC (C) or AICAR (D). (E) The m6A levelsin C2C12 cells treated with CL, AICAR or their combination. (F,G) ORO staining (F) and TG content (G) in C2C12 cells treated with CL, AICAR or their combination. (H,I) The mRNA and protein levels of the adipogenic and fatty acid lipolysis related genesin C2C12 cells treated with CL, AICAR or their combination. CC, Compound C; CL, cycloleucine. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. n = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Scale bars: 100 μm.

To further examine whether inhibition of mRNA m6A methylation can rescue the effect of AMPK activation on reducing lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells, we treated adipogenic differentiated C2C12 cells with cycloleucine in combination with AICAR. We found that cycloleucine reduced the m6A methylation level while AICAR increased the m6A level, but the combined treatment of cycloleucine and AICAR led to a compromised mRNA m6A level similar to the cycloleucine group (Fig. 5E). Notably, cycloleucine rescued the lipid accumulation that was downregulated by AICAR (Fig. 5F and G). Additionally, cycloleucine treatment upregulated the Cebpα expression that was decreased by AICAR (Fig. 5H). The expression of Pnpla2 and Pgc1α was much higher in the AICAR groups but was decreased by cycloleucine treatment (Fig. 5H). Consistently, Western blot results further confirmed that inhibition of mRNA m6A methylation with cycloleucine alleviated the effects of AICAR on the protein levels of FAS, PNPLA2 and PGC1α in C2C12 cells (Fig. 5I). These results showed that AMPK decreased lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells by upregulating mRNA m6A methylation.

FTO is essential for reduced m6A methylation and increased lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells

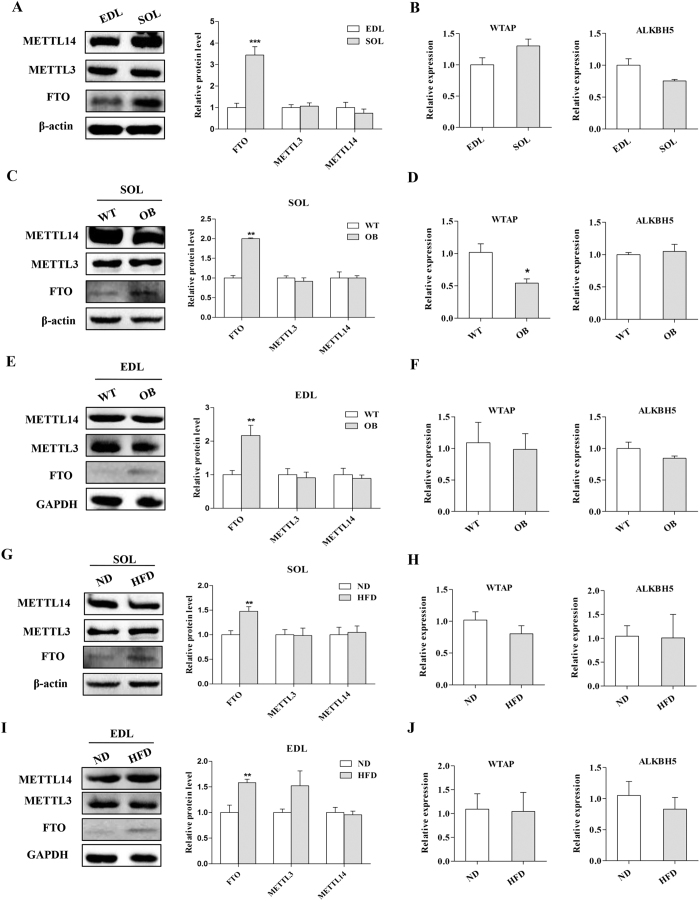

To understand the molecular mechanism by which AMPK regulates m6A methylation and lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells, we investigated the expression of m6A methylation related methyltransferases (METTL3, METTL14 and WTAP)24,25 and demethylases (FTO and ALKBH5)26,27. We found that the protein expression levels of METTL3 and METTL14 (methyltransferase like 14) as well as the relative gene expression levels of WTAP (Wilms tumor 1 associated protein) and ALKBH5 (alkB homolog 5) were similar between SOL and EDL (Fig. 6A and B). However, the protein levels of FTO were significantly higher in the SOL compared to EDL (Fig. 6A). Moreover, we found that the expression of FTO in the SOL of OB mice was upregulated, but the expression of the other m6A methylation and demethylation related genes was not obviously changed or was even reduced (Fig. 6C and D). Likewise, FTO expression was upregulated in the EDL of OB mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 6E and F). Consistently, a higher expression of FTO was found in the skeletal muscles of the HFD group compared to the ND group (Fig. 6G and H). However, the expression of the other m6A methyltransferases and demethylation genes in skeletal muscle tissues was similar between the HFD group and ND group (Fig. 6I and J). Taken together, our data demonstrated that the mRNA m6A methylation levels in skeletal muscle might be negatively regulated by FTO.

Figure 6. The expression of FTO is upregulated in the skeletal muscle of OB mice and HFD group mice.

(A,B) The protein levels of FTO, METTL3 and METTL14 (A) and the relative mRNA levels of WTAP and ALKBH5 (B) in the EDL and SOL of WT mice. (C,D) The protein expression of FTO, METTL3 and METTL14 (C) and the mRNA levels of WTAP and ALKBH5 (D) in the SOL of WT and OB mice. (E,F) The protein levels of FTO, METTL3 and METTL14 (E) and the mRNA levels of WTAP and ALKBH5 (F) in the EDL of WT and OB mice. (G,H) The protein expression levels of FTO, METTL3 and METTL14 (G) and the relative expression of WTAP and ALKBH5 (H) in the SOL of the ND and HFD group. (I,J) The protein expression of FTO, METTL3 and METTL14 (I) and the relative expression of WTAP and ALKBH5 (J) in the EDL of the ND and HFD groups. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. n = 4–6. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

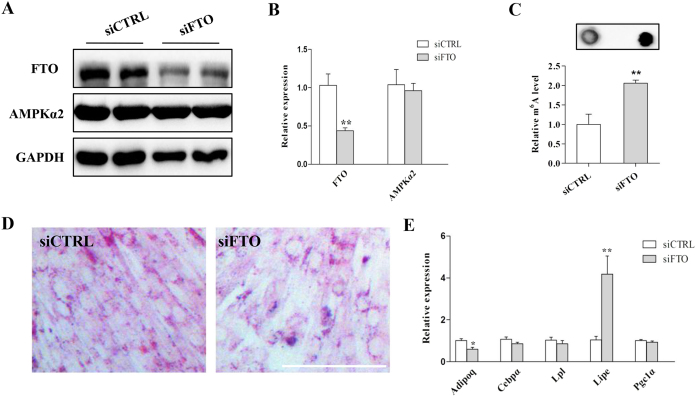

We next examined the effect of FTO on adipogenic-differentiation in C2C12 cells. The mRNA and protein expression of FTO were significantly reduced by siRNA (Fig. 7A and B). The mRNA m6A methylation level was increased by knockdown of FTO with siRNA (Fig. 7C). ORO staining results indicated that the cellular lipid content was decreased in the FTO knockdown group compared to the control group (Fig. 7D). Real-time PCR analysis showed that Adipoq expression was inhibited while Lipe expression was upregulated when FTO was knocked down (Fig. 7E). Notably, we found that knockdown of FTO did not affect the expression of AMPKα2 (Fig. 7A and B). These results revealed that FTO was essential for maintaining a normal m6A methylation level and lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells.

Figure 7. FTO is essential for m6A methylation and lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells.

(A,B) The protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels of FTO in C2C12 cells after knockdown of FTO with siRNA (siFTO). (C) The level of mRNA m6A methylation was increased after FTO knockdown. (D) ORO staining of C2C12 cells after knockdown of FTO. (E) The expression of lipid metabolism related genes after FTO knockdown. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM. n = 3–5. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. Scale bars: 100 μm.

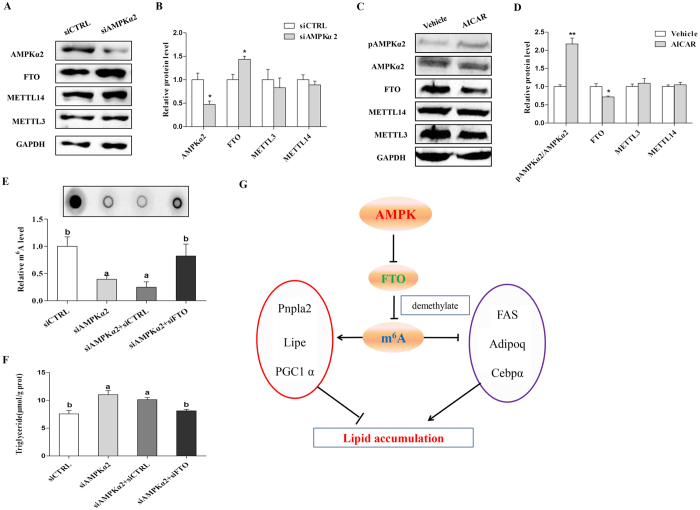

AMPK negatively regulates mRNA m6A methylation through FTO-dependent demethylation

To directly determine whether AMPK negatively regulates skeletal muscle mRNA m6A methylation and lipid metabolism through FTO, we treated C2C12 cells with Compound C. Western blot analysis revealed that the p-AMPKα2 level was reduced while the expression of FTO was increased after Compound C treatment (Fig. S5A and B). Furthermore, when AMPKα2 was knocked down by siRNA, FTO expression was enhanced in C2C12 cells (Fig. 8A and B). By contrast, activation of AMPK by AICAR suppressed FTO protein expression (Fig. 8C and D). We next performed co-transfection of AMPKα2 and FTO in C2C12 cells. When AMPKα2 was knocked down, the m6A methylation level was reduced. However, the m6A methylation level was restored when C2C12 cells were transfected with both siAMPKα2 and siFTO (Fig. 8E). Moreover, the triglyceride content was also restored when both siAMPKα2 and siFTO were transfected into C2C12 cells (Fig. 8F). Similar results were also observed when C2C12 cells were treated with Compound C and siFTO (Fig. S5C and D). Based on our above findings, we conclude that AMPK inversely regulates FTO expression and subsequently affected m6A methylation and cellular lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells (Fig. 8G).

Figure 8. AMPK regulates lipid accumulation and m6A methylation through FTO-dependent demethylation in C2C12 cells.

(A,B) The protein levels of AMPKα2, FTO, METTL3 and METTL14 in C2C12 cells after knockdown of AMPKα2. The relative expression levels of AMPKα2, METTL3, METTL14 and FTO were normalized to GAPDH. (C,D) The protein levels of AMPKα2, p-AMPKα2, FTO, METTL3 and METTL14 in C2C12 cells after AICAR treatment. The relative protein levels of p-AMPKα2, METTL3, METTL14 and FTO were normalized to GAPDH in C2C12 cells after AICAR treatment. (E) The m6A methylation levels after treatment with siAMPKα2, siFTO or their combination. (F) The triglyceride content after treatment with siAMPKα2, siFTO or their combination. (G) A model depicting the role of AMPK in the regulation of lipid accumulation and m6A methylation through FTO-dependent demethylation in skeletal muscle cells. CC, Compound C. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. n = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we provide a novel mechanism for AMPK in the regulation of skeletal muscle lipid accumulation through FTO-dependent demethylation of m6A. We first confirmed the inverse correlation between AMPK and skeletal muscle lipid content and subsequently revealed the downregulation of AMPK on lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells. Interestingly, we found that the m6A methylation levels of mRNA were inversely correlated with lipid content in skeletal muscle cells. Furthermore, AMPK decreases lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells by regulating mRNA m6A methylation. At the molecular level, we demonstrated that AMPK decreases mRNA m6A methylation and lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells through FTO-dependent demethylation. Our study provides new insight into the controlling of lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells and the treatment of obesity or T2D by downregulating AMPK or mRNA m6A methylation.

Intracellular triglycerides are functionally important in health and disease35. Intramuscular triglycerides have long been shown to be associated with metabolic dysfunction, including insulin resistance, obesity and T2D4,5,6. However, recent studies have increasingly challenged this accepted paradigm36. For instance, although IMTG content and insulin sensitivity have a strong negative correlation37, emerging evidence argues that the development of obesity and insulin resistance is due to increased fat oxidation36. Based on these findings, accretion of TG is an association with skeletal muscle insulin resistance and T2D, but is not known to be causative. Furthermore, studies have found that MCK-PGC1α mice have increased mitochondrial content accompanied with increased IMTG accumulation, which indicates that mitochondrial function may not be related to IMTG accumulation38. Moreover, elevated IMTG content is observed when the transcriptional regulator of skeletal muscle glucose utilization genes, Nur7739, is ablated, suggesting that glucose utilization may not be involved in the IMTG accumulation process. Because of this, it is urgent to better understand the underlying mechanism of IMTG metabolism, and our study contributes to understanding the accumulation pattern of IMTG.

AMPK is the major cellular energy sensor20 and acts as a critical mediator in skeletal muscle lipid metabolism14,15,16,17,18,19. Here, we confirmed the inverse correlation between AMPK and skeletal muscle lipid content. Higher expressions of adipogenic genes but lower expressions of AMPKα2 were observed in SOL muscle compared to EDL muscle40. Furthermore, enhanced lipid content was observed in the skeletal muscle from obese subjects9. Previous studies found that AMPK activity is downregulated in obese mice skeletal muscle41 and that low AMPK activity may be related to the abnormal status of muscle fatty acid metabolism in obesity42. Likewise, HFD feeding increases lipid content but decreases the p-AMPK level in skeletal muscle43,44. Our results from the skeletal muscles of OB mice and HFD fed mice were in accordance with these reports. In addition, we also found that AMPK inhibition enhanced cellular lipid content while AMPK activation reduced lipid content in C2C12 cells. Our results are consistent with previous reports45,46 and demonstrate that AMPK acts as a negative regulator of lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells.

Previous reports have shown that AMPK regulates lipid accumulation by activating ATGL to increase lipolysis47 and decreases C/EBPα and FAS expression to inhibit fat synthases40. Here, we found that AMPK negatively regulated lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells by regulating mRNA m6A methylation. It has been reported that mRNA m6A methylation is involved in lipid metabolism and fat synthesis in different tissues including the liver48 and adipose tissue33. In 3T3-L1 cells, increasing the mRNA m6A methylation level inhibits differentiation while decreasing the mRNA m6A methylation level promotes 3T3-L1 differentiation, indicating that mRNA m6A modification plays a crucial role during adipogenesis23. Recently, our previous study showed that inhibition of mRNA m6A methylation by cycloleucine enhanced adipogenesis while increasing mRNA m6A methylation level via the methyl donor betaine suppressed adipogenesis in porcine adipocytes22. We found that mRNA m6A methylation inversely modulated lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells. Inhibition of m6A methylation decreased the expression of ATGL, HSL and PGC1α while increasing the expression of C/EBPα in C2C12 cells. ATGL and HSL are the two key enzymes in lipolysis11,13. PGC1α promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and thus facilitates fat oxidation in skeletal muscle49. C/EBPα belongs to the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family and is essential for lipid accumulation50. mRNA m6A methylation upregulates skeletal muscle lipid accumulation, likely through upregulation of lipid synthase related genes (C/EBPα and FAS) and downregulation of lipolysis and oxidation related genes (ATGL, HSL, PGC1α). mRNA m6A methylation is involved in adipogenesis23 and may be regulated by AMPK33. We found that AMPK positively regulated the m6A level in C2C12 cells. Inhibition of mRNA m6A methylation could alleviate the effect of AMPK on lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells. Together, we demonstrated that AMPK negatively affects lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells, at least partially, by mediating m6A methylation.

mRNA m6A methylation is controlled by methyltransferases (METTL3, METTL14 and WTAP)24,25 and demethylases (FTO and ALKBH5)26,27. We demonstrate that AMPK regulates lipid accumulation and mRNA m6A methylation through FTO dependent demethylation. The FTO gene is widely expressed in peripheral regions related to energy homeostasis, including the liver, adipose tissue and skeletal muscle51. FTO plays an important role in demethylation. A recent study revealed that FTO could efficiently demethylate m6A in nuclear RNA by co-localizing with nuclear speckles26. Previous studies demonstrated that FTO may be crucial for normal skeletal muscle lipid accumulation and function52,53,54. The effect of FTO on adipocyte proliferation and differentiation requires its demethylase activity23,55. Our data showed that the expression of FTO was upregulated in the skeletal muscle of HFD and OB mice and therefore demethylated their methylated mRNA m6A. Moreover, our data revealed that inhibition of AMPK upregulated FTO expression while activation of AMPK downregulated FTO expression, which, to our knowledge, is the first instance that the relationship between AMPK and FTO in C2C12 cells has been elucidated. Consistently, our previous study showed that AMPK inversely regulates FTO in adipose tissues33. Other studies also showed that AMPK may inversely regulate FTO expression56,57. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanism by which AMPK regulates FTO and m6A methylation in skeletal muscle cells.

In summary, we demonstrate that AMPK plays a critical role in regulating m6A levels and lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells. Our study revealed that FTO-dependent demethylation of mRNA m6A methylation was involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle lipid accumulation by the AMPK signalling pathway. These results enhance our understanding of the role of AMPK in the regulation of lipid accumulation and mRNA m6A methylation in skeletal muscle cells and provide new insights into the molecular regulation of lipid metabolism and metabolic diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animals and experimental protocol

All of the animal procedures were approved by the Committee of Experimental Animal Care of Zhejiang University (Hangzhou, China). All of the experimental methods were performed in accordance with approved guidelines.

Sixteen 10-wk-old male C57BL/6 J mice [wild-type (WT) mice] and six 10-wk-old male obese C57BL/6Job/ob (OB) mice were purchased from Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University. WT mice were randomly divided into 2 groups (8 mice/group): normal chow diet (ND) and high-fat diet (HFD) groups. The ND group was fed with a normal chow diet containing10% fat, 20% protein and 70% carbohydrate. The HFD group was fed a HFD containing 45% fat, 20% protein and 35% carbohydrate. OB mice were fed with ND. All mice were housed at 22 ± 1 °C under a 12-h light cycle with free access to water and diet during the experiment. After 8 weeks, the extensor digitorumlongus (EDL) and soleus (SOL) muscles were collected for triglyceride detection or were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for total RNA and protein extraction.

Cell culture and adipogenic differentiation

The mouse myoblast cell line C2C12 was maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For adipogenic differentiation, the cells were induced with adipogenic induction medium containing 0.5 μM 3-isobuty-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 1 μM dexamethasone (DEXA) and 167 nM insulin for 2 days and then induced in differentiation medium containing 167 nM insulin for 2 days, followed by culturing with 10% FBS/DMEM medium until analysis.

Cell treatment

Cell treatment was performed after adipogenic differentiation. To activate AMPK, the cells were treated with 1 mM AICAR (Selleckchem, Houston, USA) for 24 hours. To inhibit AMPK, the cells were treated with 10 μM Compound C (Selleckchem, Houston, USA) for 24 hours. To inhibit m6A methylation, the cells were treated with 10 μM cycloleucine (Sigma, USA) for 24 hours.

siRNA transfection

siRNA against FTO or AMPKα2 and a negative control (siCTRL) were designed and produced by RiboBio Company (Guangzhou, China). Twenty-four hours before transfection, cells were plated without any antibiotics. Then, 100 nM specific siRNA or siCTRL was transfected into C2C12 myoblasts using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Oil Red O (ORO) staining and triglyceride detection

Cultured cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature. Then, all formaldehyde was removed and ORO working solutions were added containing 6 ml ORO stock solution (5 mg/ml in isopropanol) and 4 ml dH2O for 10 min. After staining, cells were washed with dH2O and then imaged. The triglyceride (TG) levels in skeletal muscle and cultured C2C12 cells were determined using a triglyceride determination kit (Applygen, China).

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

The total RNA from all skeletal muscle and cells was extracted using the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer′s instructions. RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas) was used to synthesize cDNA. Real-time PCR was performed with the StepOnePlusTM Real Time System (Applied Biosystems); the reaction contained 4 steps: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, and then 60 °C for 30 s. All primers used in this study were listed in Table 1. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to quantify mRNA expression relative to 18s rRNA.

Table 1. Primers used for real-time PCR.

| Genes | Primers | Sequences |

|---|---|---|

| 18S | Forward | TAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT |

| Reverse | CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG | |

| Adipoq | Forward | CCGGGACTCTACTACTTCTCTT |

| Reverse | TTCCTGATACTGGTCGTAGGT | |

| Alkbh5 | Forward | GGTGTTTCTCCTCCCTTTAGTC |

| Reverse | CAGAGCAGGCACATCTTCTTA | |

| AMPKα2 | Forward | AGACTTAACAGCCTGGAACATAC |

| Reverse | CTACGGGCAGTCTCACATTTAG | |

| C/EBPα | Forward | GTAACCTTGTGCCTTGGATACT |

| Reverse | GGAAGCAGGAATCCTCCAAATA | |

| FTO | Forward | CAGTTCTGGTTTCAAGGCAATC |

| Reverse | TGTCATGCTCTCCATCTTCTTC | |

| Leptin | Forward | GGTTGATCTCACAATGCGTTTC |

| Reverse | TGGGAGACAGGGTTCTACTT | |

| Lipe | Forward | CATCAACCACTGTGAGGGTAAG |

| Reverse | AAGGGAGGTGAGATGGTAACT | |

| Lpl | Forward | GCCCGAGGTTTCCACAAATA |

| Reverse | GCTGAAGTAGGAGTCGCTTATC | |

| Pgc1α | Forward | GGATTGAAGTGGTGTAGCGAC |

| Reverse | GCTCATTGTTGTACTGGTTGGA | |

| Pnpla2 | Forward | TAGCTAACAGTTGGGCTTCAC |

| Reverse | CAGAGAGAACAGAGCAGCTTAC | |

| WTAP | Forward | GTACCAGCAGGACTACATCTTC |

| Reverse | CTGCCATTACTTGGTCCATTTG |

Western blotting analysis

Proteins from all the skeletal muscles and cells were extracted using the Protein Extraction Reagent (KeyGENBioTECH, Nanjing, China), and the concentrations were determined with the BCA Assay Kit (KeyGENBioTECH, Nanjing, China). Next, equal amounts of protein were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels followed by electrotransfer to polyvinylidenedifluoride membranes (PVDF). After blocking with 5% skim milk powder in 0.05% TBST, the membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies: FTO, phospho-AMPKα2 (Abcam), AMPKα2 (GeneTex), METTL3 (Proteintech), METTL14 (Sigma), FAS, C/ebpα, ATGL, PGC1α (Santa Cruz), GAPDH (Boster) and β-actin (Hua An, Hangzhou, China). The secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbitIgG (Hua An, Hangzhou, China). Finally, the immunocomplexes were detected using the ECL Western Blotting Detection System (Amersham, Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Dot-blot assay

To analyse the level of mRNA m6A methylation, a dot blot assay was performed according to a previously reported method26. Briefly, isolated RNA was first denatured at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by immediate chilling on ice. The denatured RNA was then spotted on an NC membrane optimized for nucleic acid transfer. After UV cross-linking in a StratageneStratalinker 2400 UV Crosslinker, the membrane was washed with 1× TBST, blocked with 5% of non-fat milk in TBST, and incubated with anti-m6A antibody (1:2000, Synaptic Systems) overnight at 4 °C. After incubating with a corresponding peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, the membrane was detected using the ECL Western Blotting Detection System (Amersham, Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). To ensure an equal amount of RNA was spotted on the membrane, the same blot was stained with 0.02% methylene blue in 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Each cell culture experiment was performed in triplicate and that results presented represent the findings from 2–3 individual experiments. We used Pearson correlation analysis to determine correlations. The statistical significance of differences in the mean values between groups was assessed by Student’s t-test, and a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wu, W. et al. AMPK regulates lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells through FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine. Sci. Rep. 7, 41606; doi: 10.1038/srep41606 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2012CB124705) and the Special Fund for Cultivation and Breeding of New Transgenic Organism (Grant No. 2014ZX0800949B).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions T.S., Y.W., X.W. designed this project; W.W., D.J., X.Z., Q.J., M.C. performed the experiment; W.W. and J.F. analysed the data; W.W. and T.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Whiting D. R., Guariguata L., Weil C. & Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes research and clinical practice 94, 311–321 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane M. M. et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants. The Lancet 377, 557–567 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defronzo R. A., Ferrannini E., Sato Y. & Felig P. Synergistic Interaction between Exercise and Insulin on Peripheral Glucose-Uptake. J Clin Invest 68, 1468–1474 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D. A. et al. Skeletal muscle triglyceride levels are inversely related to insulin action. Diabetes 46, 983–988 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodpaster B. H., Theriault R., Watkins S. C. & Kelley D. E. Intramuscular lipid content is increased in obesity and decreased by weight loss. Metabolism 49, 467–472 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo R. A. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Clin N Am 88, 787-+ (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmedov D. & Berdeaux R. The effects of obesity on skeletal muscle regeneration. Frontiers in physiology 4, 371 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty B. D., Cooney G. J., Kraegen E. W. & Furler S. M. Increased efficiency of fatty acid uptake contributes to lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle of high fat-fed insulin-resistant rats. Diabetes 51, 1477–1484 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Watkins S. & Kelley D. E. Skeletal muscle lipid content and oxidative enzyme activity in relation to muscle fiber type in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Diabetes 50, 817–823 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badin P. M. et al. Altered skeletal muscle lipase expression and activity contribute to insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes 60, 1734–1742 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haemmerle G. et al. Defective lipolysis and altered energy metabolism in mice lacking adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 312, 734–737 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes P. M. et al. Increased intramyocellular lipids but unaltered in vivo mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of adipose triglyceride lipase-deficient mice. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism 303, E71–81 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haemmerle G. et al. Hormone-sensitive lipase deficiency in mice causes diglyceride accumulation in adipose tissue, muscle, and testis. J Biol Chem 277, 4806–4815 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier C. A., Bruce C. R., Smith A. C., Lopaschuk G. & Dyck D. J. Metformin counters the insulin-induced suppression of fatty acid oxidation and stimulation of triacylglycerol storage in rodent skeletal muscle. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism 291, E182–189 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N. et al. Ablation of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha2 activity exacerbates insulin resistance induced by high-fat feeding of mice. Diabetes 57, 2958–2966 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth-Kraczek E. J., Hirshman M. F., Goodyear L. J. & Winder W. W. 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase activation causes GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 48, 1667–1671 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill G. F., Kurth E. J., Hardie D. G. & Winder W. W. AICA riboside increases AMP-activated protein kinase, fatty acid oxidation, and glucose uptake in rat muscle. The American journal of physiology 273, E1107–1112 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill H. M. et al. AMPK phosphorylation of ACC2 is required for skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation and insulin sensitivity in mice. Diabetologia 57, 1693–1702 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong H. H. et al. AMP kinase is required for mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle in response to chronic energy deprivation. P Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 15983–15987 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie D. G., Ross F. A. & Hawley S. A. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 13, 251–262 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Dominissini D., Rechavi G. & He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m(6)A RNA methylation. Nature reviews. Genetics 15, 293–306 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhu L., Chen J. & Wang Y. mRNA m(6)A methylation downregulates adipogenesis in porcine adipocytes. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 459, 201–207 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res 24, 1403–1419 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol 10, 93–95 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping X. L. et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res 24, 177–189 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G. F. et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO (vol 7, pg 885, 2011). Nat Chem Biol 8, 1008–1008 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G. Q. et al. ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol Cell 49, 18–29 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector D. L. & Lamond A. I. Nuclear speckles. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 3 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayling T. M. et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science 316, 889–894 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church C. et al. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nature genetics 42, 1086–1092 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J. et al. Inactivation of the Fto gene protects from obesity. Nature 458, 894–898 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Zhou X., Wu W., Wang X. & Wang Y. FTO-dependent function of N6-methyladenosine is involved in the hepatoprotective effects of betaine on adolescent mice. Journal of physiology and biochemistry 71, 405–413 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. et al. The beneficial effects of betaine on dysfunctional adipose tissue and N6-methyladenosine mRNA methylation requires the AMP-activated protein kinase alpha1 subunit. J Nutr Biochem 26, 1678–1684 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birk J. B. & Wojtaszewski J. F. Predominant alpha2/beta2/gamma3 AMPK activation during exercise in human skeletal muscle. The Journal of physiology 577, 1021–1032 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meex R. C. R., Schrauwen P. & Hesselink M. K. C. Modulation of myocellular fat stores: lipid droplet dynamics in health and disease. Am J Physiol-Reg I 297, R913–R924 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muoio D. M. Intramuscular triacylglycerol and insulin resistance: Guilty as charged or wrongly accused? Bba-Mol Cell Biol L 1801, 281–288 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodpaster B. H. & Kelley D. E. Skeletal muscle triglyceride: marker or mediator of obesity-induced insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus? Current diabetes reports 2, 216–222 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. S. et al. Paradoxical effects of increased expression of PGC-1alpha on muscle mitochondrial function and insulin-stimulated muscle glucose metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 19926–19931 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L. C. et al. Insulin Resistance and Altered Systemic Glucose Metabolism in Mice Lacking Nur77. Diabetes 58, 2788–2796 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan T. Z., Zhang P. P., Bi P. P. & Kuang S. H. Lkb1 Deletion Promotes Ectopic Lipid Accumulation in Muscle Progenitor Cells and Mature Muscles. J Cell Physiol 230, 1033–1041 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg G. R. et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced skeletal muscle insulin resistance involves suppression of AMP-kinase signaling. Cell metabolism 4, 465–474 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay G. K., Yu J. G., Ofrecio J. & Olefsky J. M. Increased malonyl-CoA levels in muscle from obese and type 2 diabetic subjects lead to decreased fatty acid oxidation and increased lipogenesis; thiazolidinedione treatment reverses these defects. Diabetes 55, 2277–2285 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg G. R. et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor stimulates muscle glucose uptake by a PI3-kinase-dependent pathway that is impaired with obesity. Diabetes 58, 829–839 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes J. J., Nguyen M. T., Bandyopadhyay G. K., Nelson E. & Olefsky J. M. Topiramate treatment causes skeletal muscle insulin sensitization and increased Acrp30 secretion in high-fat-fed male Wistar rats. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism 289, E1015–1022 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. L., Chen Y. L., Chiang Y. M., Wang S. G. & Lee H. M. Fenofibrate lowers lipid accumulation in myotubes by modulating the PPARalpha/AMPK/FoxO1/ATGL pathway. Biochem Pharmacol 84, 522–531 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Yuan H., Niu Y., Niu W. & Fu L. The role of AMPK/mTOR/S6K1 signaling axis in mediating the physiological process of exercise-induced insulin sensitization in skeletal muscle of C57BL/6 mice. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1822, 1716–1726 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadian M. et al. Desnutrin/ATGL Is Regulated by AMPK and Is Required for a Brown Adipose Phenotype. Cell metabolism 13, 739–748 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. P., Zhou X. H., Wu W. C., Wang X. X. & Wang Y. Z. FTO-dependent function of N6-methyladenosine is involved in the hepatoprotective effects of betaine on adolescent mice. J Physiol Biochem 71, 405–413 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Gomez G., Gray S. & Vidal-Puig A. Adipogenesis and lipotoxicity: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) and PPARgammacoactivator-1 (PGC1). Public health nutrition 10, 1132–1137 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. D. et al. Cross-regulation of C/EBP alpha and PPAR gamma controls the transcriptional pathway of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. Mol Cell 3, 151–158 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken T. et al. The obesity-associated FTO gene encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent nucleic acid demethylase. Science 318, 1469–1472 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravard A. et al. FTO is increased in muscle during type 2 diabetes, and its overexpression in myotubes alters insulin signaling, enhances lipogenesis and ROS production, and induces mitochondrial dysfunction. Diabetes 60, 258–268 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church C. et al. A mouse model for the metabolic effects of the human fat mass and obesity associated FTO gene. PLoS genetics 5, e1000599 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larder R., Cheung M. K., Tung Y. C., Yeo G. S. & Coll A. P. Where to go with FTO? Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM 22, 53–59 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkestein M. et al. FTO influences adipogenesis by regulating mitotic clonal expansion. Nat Commun 6, 6792 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray F. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of FTO. Plos One 10, e0121829 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. L. et al. Expression and significance of fat mass and obesity associated gene and forkhead transcription factor O1 in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Chinese Med J-Peking 127, 3771–3776 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.