ABSTRACT

Bispecific IgG production in single host cells has been a much sought-after goal to support the clinical development of these complex molecules. Current routes to single cell production of bispecific IgG include engineering heavy chains for heterodimerization and redesign of Fab arms for selective pairing of cognate heavy and light chains. Here, we describe novel designs to facilitate selective Fab arm assembly in conjunction with previously described knobs-into-holes mutations for preferential heavy chain heterodimerization. The top Fab designs for selective pairing, namely variants v10 and v11, support near quantitative assembly of bispecific IgG in single cells for multiple different antibody pairs as judged by high-resolution mass spectrometry. Single-cell and in vitro-assembled bispecific IgG have comparable physical, in vitro biological and in vivo pharmacokinetics properties. Efficient single-cell production of bispecific IgG was demonstrated for human IgG1, IgG2 and IgG4 thereby allowing the heavy chain isotype to be tailored for specific therapeutic applications. Additionally, a reverse chimeric bispecific IgG2a with humanized variable domains and mouse constant domains was generated for preclinical proof-of-concept studies in mice. Efficient production of a bispecific IgG in stably transfected mammalian (CHO) cells was shown. Individual clones with stable titer and bispecific IgG composition for >120 days were readily identified. Such long-term cell line stability is needed for commercial manufacture of bispecific IgG. The single-cell bispecific IgG designs developed here may be broadly applicable to biotechnology research, including screening bispecific IgG panels, and to support clinical development.

KEYWORDS: Bispecific antibody, bispecific IgG, orthogonal Fab engineering, single-cell production, stable CHO cell lines

Abbreviations

- BiP

binding immunoglobulin protein

- BsIgG

bispecific IgG

- CDR

complementarity-determining region

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- ECD

extracellular domain

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMR

extended mass range

- Fab

antigen-binding fragment

- HC

heavy chain

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- LC

light chain

- MS

mass spectrometry

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- REU

Rosetta energy units

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Bispecific antibodies are of growing interest as therapeutics, with more than 50 such molecules in clinical development for various indications.1,2 Bispecific antibodies can expand the functionality of traditional monospecific antibodies such as targeting effector cells to kill tumor cells, enhancing tissue specificity,3 or combining the antigen binding of two monoclonal antibodies in a single molecule to simultaneously silence two cellular signaling pathways.

The bispecific IgG (BsIgG) format is one of the more attractive of the >60 different bispecific antibody formats described to date2 as it provides the option for long serum half-life and effector functions. However, BsIgG are challenging to produce given their complex hetero-tetrameric composition. Indeed, coexpression of two different light chain (LC) and heavy chains (HC) can result in up to nine unwanted chain pairings in addition to the desired BsIgG, as first demonstrated with hybrid hybridomas.4 For efficient production of BsIgG in single host cells, it is desirable to achieve selective pairing of cognate LC and HC and heterodimerization of the two different HC.

The first efficient method for recombinant BsIgG production was developed in the 1990s using knobs-into-holes mutations to promote selective HC heterodimerization and a common LC to avoid mispairing of LC with non-cognate HC.5-7 Briefly, a steric clash or knob at the CH3/CH3 interface was created by replacing a small amino acid with a larger and bulkier residue. Amino acid residues surrounding the knob mutation on the opposing side of the dimer interface were optimized using phage display to form a compatible indented surface or hole.5 The knobs-into-holes mutations favor HC heterodimerization over competing homodimerization. The common LC antibodies were identified from a human scFv phage display library with limited LC diversity.6,8 A limitation of this original method is that it constrains the choice of antibodies that can be used for making BsIgG. This limitation has been partially overcome by novel transgenic animal platforms9 and also new combinatorial libraries with a common LC to facilitate the discovery of suitable antibodies.

In recent years, a plethora of creative solutions for recombinant production of BsIgG and related antibody molecules have been developed that overcome or avoid the HC and LC pairing problems.2 For example, several dual-cell BsIgG technologies have been developed in which each IgG arm of the BsIgG is separately expressed and purified followed by in vitro assembly into BsIgG.10-14 The separate production of each component IgG avoids LC mispairing, whereas selective HC heterodimerization is achieved through a variety of different HC engineering strategies.10-14 These dual-cell BsIgG technologies are now well established and have been used to produce several BsIgG for clinical development. In generating related BsIgG that share one antibody arm these dual-cell BsIgG technologies provide the flexibility to repurpose a stable cell line or one of the purified components. In addition, the analytical characterization of the final BsIgG is relatively simple as only two IgG chain-mispairing contaminants are expected, i.e., the two homodimeric parent IgG. Drawbacks of dual-cell IgG technologies include the relatively high cost and complexity of manufacturing. Also, these dual-cell technologies are not well-suited to generating large BsIgG panels for screening for optimal antibody pairs.

Multiple engineering strategies have been established to express BsIgG and related bispecific antibodies in single host cells. Some of these single-cell technologies utilize peptide linkers tethering antibody variable domains, as in DVD-Ig,15 or domain swaps such as CrossMabs16 to achieve correct HC/LC pairing. It remains to be seen whether the linkers or non-natural junctional sequences used pose a significant immunogenicity risk.

More recently, several antigen-binding fragment (Fab) engineering technologies devoid of linkers or non-natural junctions have been successfully developed for single-cell production of BsIgG.3,17,18 These single-cell BsIgG technologies utilize Fab engineering for selective pairing of cognate LC and HC, in conjunction with HC engineering for preferential HC heterodimerization. Strategies used for Fab engineering by others include either computational design17 or electrostatic steering using pairs of charge residues18 at both VH/VL and CH1/CL interfaces. An additional approach has been to engineer an alternative inter-chain disulfide bond at the CH1/CL interface.3 As these Fab engineering approaches typically utilize non-solvent exposed residues, they may provide the advantage of a lower immunogenicity risk than approaches that use linker sequences.

One advantage of single-cell over dual-cell BsIgG is the potential for simpler and more cost efficient manufacturing. In contrast, analytical characterization of BsIgG is more challenging when derived from single-cell than dual-cell technologies. This reflects the potential for up to nine mispaired IgG species with single-cell BsIgG, compared with only two mispaired IgG for dual-cell BsIgG. As single-cell technologies now approach quantitative formation of BsIgG, monitoring for very low levels of potential IgG contaminants becomes increasingly difficult. Previous studies establishing single-cell BsIgG technologies based on Fab engineering mainly utilized quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MS).3,17,18 In anticipation of this difficult analytical challenge for single-cell BsIgG, we developed a high throughput analytical method utilizing online liquid chromatography in conjunction with EMR-Orbitrap mass spectrometer providing higher mass resolution.19 Additional precision of the BsIgG content was achieved by statistical estimation of the distribution of the isobaric species, namely the desired BsIgG and the LC-scrambled IgG.19 These improved analytical liquid chromatography-MS approaches gave limits of detection and quantitation of 0.3% and 1%, respectively.19

Here, we have developed novel orthogonal Fab designs that facilitate selective pairing of cognate HC and LC. These designs were combined with HC knobs-into-holes mutations5,7 for efficient production of BsIgG in single host cells. Minimal contamination from unwanted chain pairings was observed for multiple different antibody pairs. Elegant orthogonal Fab designs from other investigators have been used for efficient production of BsIgG of human IgG1 isotype.3,16-18 Our designs were evaluated and shown to support efficient production of bispecific IgG of multiple human isotypes namely, IgG1, IgG2 and IgG4. This allows the isotype to be selected for the desired effector functions in research and therapeutic applications. We also extended our technology to the efficient production of a reverse chimeric BsIgG2a with humanized variable domains and mouse constant domains to support critical preclinical proof-of-concept studies in mice. The single-cell technology described here may provide benefits throughout BsIgG drug discovery and development. For example, our single-cell BsIgG technology is anticipated to allow the facile construction of large panel of BsIgG for lead identification through in vitro assays and in vivo studies in mice. Additionally, this single-cell BsIgG technology has the potential to simplify the production of clinical material as evidenced by robust translation to stable cell line development.

Results

Selection of anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG as a test case for orthogonal Fab designs

Several criteria were applied to select an anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)2/CD3 BsIgG for the initial evaluation of orthogonal Fab designs for selective pairing of cognate HC and LC. Firstly, well-characterized antibodies were available for the anti-HER2 (humAb4D5–8)20 and anti-CD3 (humAbUCHT1-v9)21 arms that have favorable expression and physicochemical properties. Secondly, the pairing of anti-HER2 and anti-CD3 LC with HC is random with no detectable preference for cognate chain pairing as judged by coexpression studies (Table 1). Thus, this allows analysis of the success of the designs independent from any contribution from intrinsic pairing preference for cognate HC and LC. This may provide a more stringent test case for orthogonal Fab designs than for other antibody pairs in this study where there is a strong intrinsic preference for cognate chain pairing (Table 2). Thirdly, we have previously demonstrated targeting of T cells to tumor cells overexpressing HER2 with an anti-HER2/CD3 bispecific antibody,22 and there has been renewed interest in this approach in recent years.23

Table 1.

HC and LC variants to direct the assembly of anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 in a single host cell. The anti-HER2 and anti-CD3 HC and κ-LC variants were co-transfected into Expi293F cells. The resultant BsIgG1-containing mixture was purified from the cell culture harvest fluid by protein A chromatography and then analyzed by liquid chromatography-EMR Orbitrap mass spectrometry. The percentage of BsIgG1 was calculated by quantifying all IgG1 species present (excluding very small amounts of half antibodies and HC homodimers). Statistical estimation of the isobaric mixture containing BsIgG and double LC scrambled IgG1 was performed as previously described.19 The anti-HER2 HC variants additionally contains the knob mutation (T366W) whereas the anti-CD3 HC variants contains the hole mutations (T366S:S368A:Y407V) as previously described.5 yt65H refers to the CH1 mutations A141I:F170S:S181M:S183A:V185A and yt65L refers to the CL mutations F116A:L135V:S174A:S176F:T178V. Data shown are for optimized LC ratios. The top designs, v10 and v11, are highlighted in bold.

| Orthogonal pairing | Anti-HER2 HC |

Anti-HER2 LC |

Anti-CD3 HC |

Anti-CD3 LC |

BsIgG1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| variant | VH | CH1 | VL | CL | VH | CH1 | VL | CL | (%) |

| Parent | 24.6 | ||||||||

| v1 | Q39E | Q38K | Q39K | Q38E | 55.7 | ||||

| v2 | S183E | V133K | 46.5 | ||||||

| v3 | S183K | V133E | 24.9 | ||||||

| v4 | yt65H | yt65L | 59.5 | ||||||

| v5 | S183K | V133E | S183E | V133K | 46.4 | ||||

| v6 | yt65H | yt65L | S183E | V133K | 87.0 | ||||

| v7 | Q39E | Q38K | Q39K | S183E | Q38E | V133K | 81.2 | ||

| v8 | Q39E | S183K | Q38K | V133E | Q39K | Q38E | 63.0 | ||

| v9 | Q39E | yt65H | Q38K | yt65L | Q39K | Q38E | 84.4 | ||

| v10 | Q39E | S183K | Q38K | V133E | Q39K | S183E | Q38E | V133K | 91.7 |

| v11 | Q39E | yt65H | Q38K | yt65L | Q39K | S183E | Q38E | V133K | 100.0 |

| v12 | yt65H | yt65L | Q39K | S183E | Q38E | V133K | 98.2 | ||

Table 2.

HC and LC variants to direct the assembly of different antibody pairs as BsIgG1. Antibody HC and κ-LC variants were co-transfected into Expi293F cells. The resultant BsIgG1-containing mixture was purified from the cell culture harvest fluid by protein A chromatography and then analyzed by liquid chromatography-EMR Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Data shown are for optimized LC ratios. All antibodies have LC of the κ-isotype. Anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 data are included from Table 1 for comparison. See Table 1 legend for additional details.

| BsIgG1 (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Pairing variant | Anti-HER2 / CD3 | Anti-IL-4 / IL-13 | Anti-EGFR / MET | Anti-VEGFA/ ANG2 | Anti-VEGFA/ VEGFC |

| Parent | 24.6 | 70.8 | 73.4 | 24.0 | 34.5 |

| v10 | 91.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 98.9 | 100.0 |

| v11 | 100.0 | 95.6 | 100.0 | 94.9 | 100.0 |

Computational design of CH1/CL variants for orthogonal Fab arm pairing

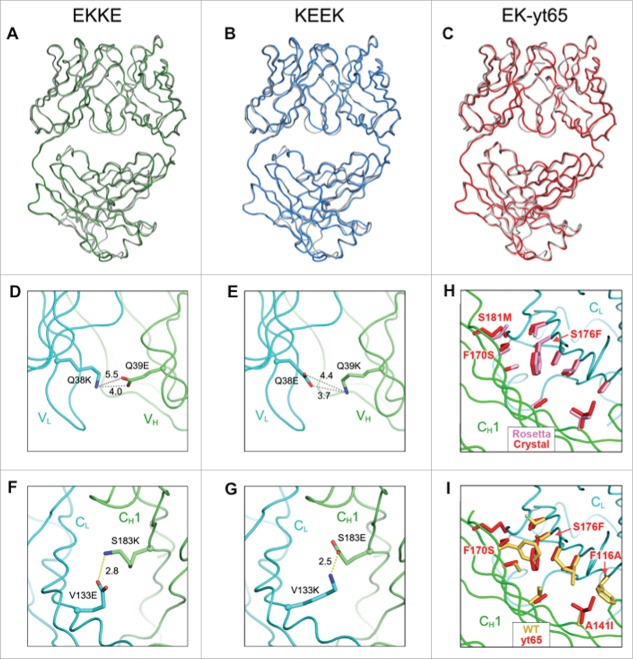

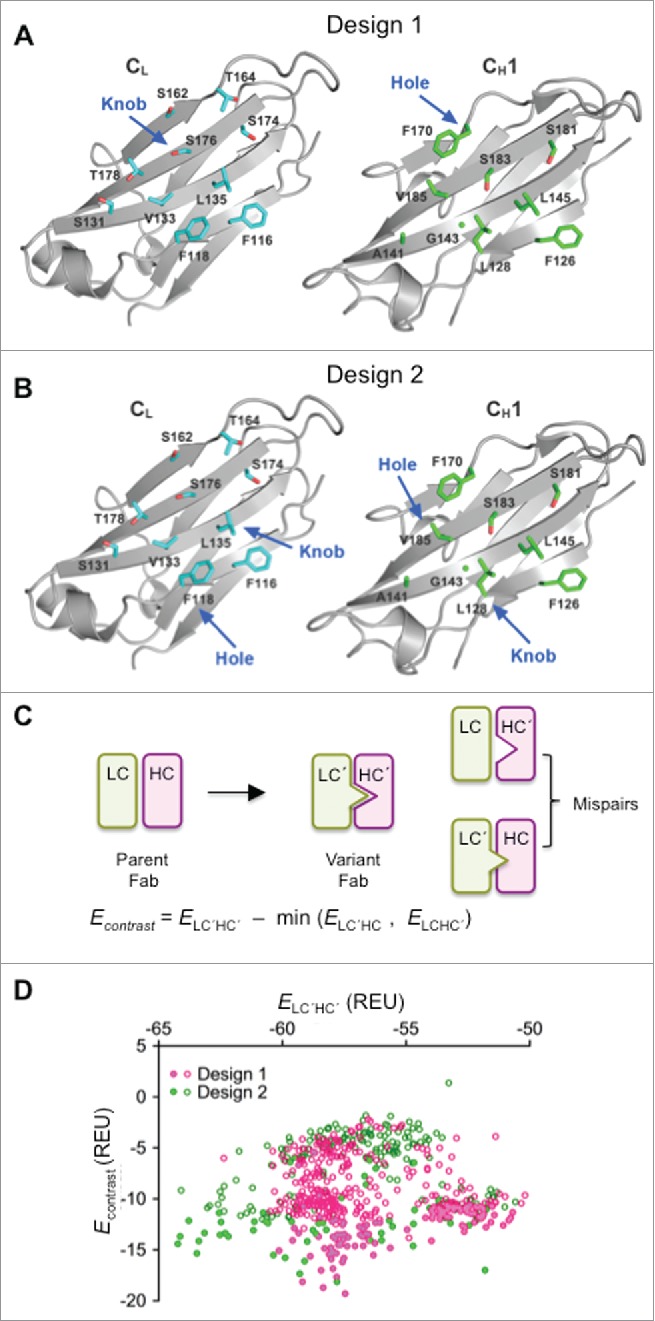

Our initial Fab orthogonal pairing designs focused on the CH1/CL interface using a knobs-into-holes strategy as previously developed for antibody CH3 domains.5-7 The goal was to create a stably paired and redesigned CH1/CL interface with mutations that would create incompatibility toward binding to the wild-type CH1 or CL domains. First, a computational alanine scan was performed using the Rosetta suite to identify the positions that could potentially destabilize the CH1/CL pairing.24,25 Residues CH1 F170 and CL F118 displayed the largest binding energy loss upon replacement by alanine (Fig. S1) and were selected for the hole designs. The knob designs were then selected by looking for positions located opposite to the hole mutations in the CH1/CL interface. All the knobs-into-holes mutations as well as other selected interface residues were subsequently optimized by computational design.

Two main computational design strategies were implemented together with flexible backbone modeling in Rosetta (see Supplementary Materials).26 Design 1 (Fig. 1A) included one hole mutation by allowing residue CH1 F170 to be replaced with smaller nonpolar amino acids, and one knob mutation created by replacing CL S176 with large aromatic amino acids, namely, Phe, Tyr and Trp. Other surrounding interface residues were redesigned with more freedom in order to optimize the modified interface for favorable stability. For design 2 (Fig. 1B), the CH1/CL interface was redesigned more extensively with multiple sets of knob-into-hole modifications. One set has CL F118 mutated to a hole, and CH1 L128 mutated to a knob. A second set has CL L135 as a knob, and CH1 V185 kept as a small nonpolar residue.

Figure 1.

Computational design and selection of HC and LC variants. (A) Open book view of human IgG1 CH1/CL domains (PDB 1N8Z)57 showing side-chains of domain interface residues selected for Design 1. Residues CL S176 and CH1 F170 were selected for design of knob and hole mutations, respectively. (B) Open book view of human IgG1 CH1/CL domains (PDB 1N8Z) showing side-chains of domain interface residues selected for Design 2. Residues CH1 L128 and CL F118 were selected for design of the first knob and hole pair, respectively, and residues CL L135 and CH1 V185 for the second knob and hole pair, respectively (C) Energy contrast filter for computational designs. (D) Contrast vs. stability plot for the unique sequence outputs from Rosetta. Filled and unfilled symbols correspond to variants that were or were not evaluated in experiments, respectively.

The two design strategies were independently performed using Rosetta. Stepwise, a design candidate was first evaluated by a stability filter, which calculates the binding energy of the redesigned CH1 and CL mutants. Next, a contrast filter was run to evaluate the orthogonality of the mutated candidate chains over undesired pairing with the parent chains. The contrast filter calculates the binding energies of the two mispairs, the mutant CH1 pairing to the parent CL and the mutant CL pairing to the parent CH1, and then calculates the energy difference between the CH1/CL mutant and the more stable one of the two mispairs (Fig. 1C). All candidate sequences that passed both filters were output for further analysis.

A total of 616 unique sequences were obtained from both designs after removing the duplicate sequences (Table S1). The distributions of the binding energy and contrast scores for the two design strategies were similar (Fig. 1D). A total of 182 designs were picked for experimental characterization: 162 based upon their favorable contrast scores, and a further 20 based on their sampling of distinct sequence space.

Computationally-designed variants promote orthogonal pairing and increase BsIgG content in single cell production

To assess protein expression and orthogonal pairing of these computationally-designed CH1/CL variants, genes encoding the 182 designs were synthesized and sub-cloned into the anti-HER2 antibody. Four plasmids encoding the component HC and LC of an anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG were then co-transfected into Expi293F cells. The resultant IgG mixture containing BsIgG was purified by protein A affinity chromatography. IgG yields from transient expression of these variants in 293T cells were high (95% variants gave yields of 63–95 μg/mL) and comparable to the parent sequence with no Fab mutations (87 μg/mL) (Fig. S2). An anti-HER2/CD3 sandwich ELISA with purified IgG revealed that most computationally designed variants have an increased proportion of BsIgG compared with the parent (Fig. S3A), consistent with enhanced orthogonal pairing. Five variants were selected based upon their performance in the initial screen and were further screened by a titration sandwich ELISA (Fig. S3B). The performance of the variants was similar and approximately mid-way between the in vitro-assembled BsIgG (∼100% BsIgG) and the parent BsIgG (∼25% BsIgG, Table 1) with no mutations in the Fab arms (Fig. S3B). Variant, yt65, was selected as the lead candidate from the computational design because it performed similarly to other variants but had fewer mutations at the CH1/CL interface with five mutations each in CH1 (A141I:F170S:S181M:S183A:V185A) and CL (F116A:L135V:S174A:S176F:T178V).

Identification of charge-pairs in the antibody variable and constant domains promoting orthogonal pairing

Computational design often performs well in packing and hydrogen-bonding, but can have difficulties predicting the effects of charge mutations.27 Therefore, in parallel to the computational approach, we also pursued a manual structure-guided screening approach with a focus on charge pairs at the CH1/CL interface. The concept of our approach was to identify interface mutations that disrupt pairing first, and then identify compensatory mutations that restore pairing.

Based on visual analysis of an available Fab structure (Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 1CZ8, humanized anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) IgG1, κ),28 residues were identified in the CL domain, which contribute to the CH1/CL interface and have low accessibility to solvent. The CL residues F118, S131, V133, L135, S176 and T178 were mutated to Glu, Trp, Arg, or Ile to disrupt the CH1/CL interface. In these experiments, half-antibodies were expressed in E. coli and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-Fc and anti-κ LC (Fig. S4). An E. coli system was chosen for these initial expression experiments because it allowed the concurrent study of the effect of the variants on CH1/CL antibody assembly and the solubility of the unpaired LC. In this analysis, the charge variants Arg and Glu were the most effective mutations, impacting correct half-antibody assembly while enabling an increased amount of free, soluble LC (Fig. S4). Encouraged by the effects of the Arg variant, some positions, e.g., CL F118 and CL L135, were also substituted with Lys. A similar effect was observed on antibody assembly (Fig. S4 and data not shown). In addition, the effect of changes on antibody assembly appeared to be additive.

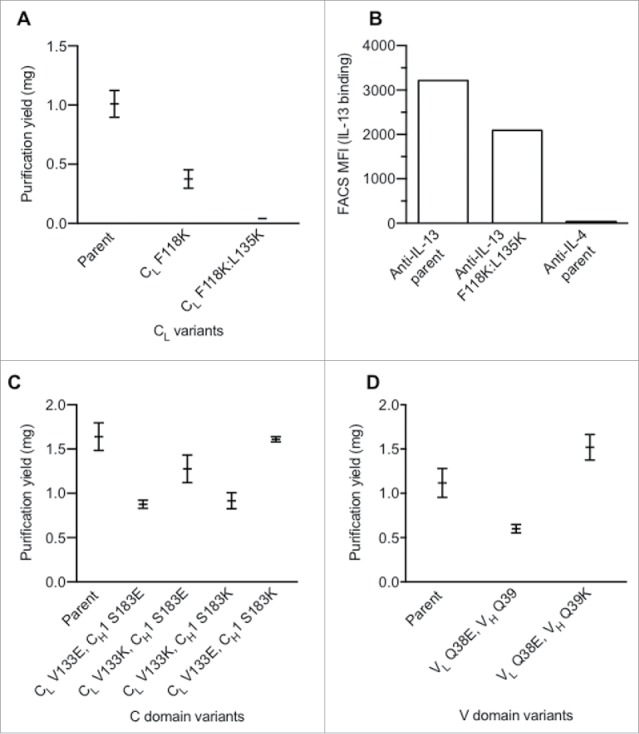

Mutations identified as disrupting antibody assembly in E. coli were next evaluated for their ability to do so in eukaryotic (HEK293T) cells. CL single (F118K) and double (F118K:L135K) variants greatly affected the secretion yield in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2A). As a next step, we needed to identify mutations in the CH1 domain to repair the disrupted interaction. To enable screening of a large CH1 mutant library, we wanted to take advantage of the antigen binding loss that should concur with the assembly defect of the CL variants. We decided to screen a potential CH1 library in a bacterial display system based on binding of fluorescently labeled antigen.29 However, further characterization of the CL changes by themselves revealed that the major effect (85%) on assembly observed by PAGE-analysis (Fig. 2A) correlates to only a small reduction (∼35%) in antigen binding by the CL F118K:L135K change in the bacterial display system (Fig. 2B).29 These data suggest independently driven pairing of constant and variable domains, which results in the charge variants in the CL domain providing only a small effect on the assembly of the variable domains. This finding is consistent with results from the CH1/CL orthogonal designs reported by Lewis et al.17

Figure 2.

Identification of charge pairs in IgG1 constant and variable domains. (A) Effect of single and double CL domain charge variants upon expression. (B) Effect on CL mutations on antigen binding as assessed by bacterial display.29 (C) Purification yield of constant domain charge pair variants. (D) Purification yield of variable domain charge pair variants. Data shown (A, C, D) are mean values ± SD.

This independent pairing of domains suggested that it may be necessary to uncouple the variable and constant domain interaction in order to identify changes in the CH1 domain able to compensate the assembly defect of a positive charge variant in the CL domain. This was achieved by tethering the VL domain to the HC with a peptide linker, (G4S4)4, and expression of the CL in trans (Fig. S5). No significant antibody expression was observed without coexpression of CL (data not shown). Guided by a Fab crystal structure (PDB 1CZ8),28 residues L128, G143, L145, S183 and V185 in CH1 were identified as being spatially near residues F118, V133 and L135 in CL and candidate positions for replacements to repair the CH1/CL pairing. Additionally, residues were chosen that do not overlap with the proposed binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) binding sites to minimize the effect on antibody folding and quality control machinery inside cells.30,31 A single positive charge at any of the tested positions (F118, V133, L135) in CL efficiently disrupted assembly (Fig. S5). Repair of the assembly defect was attempted by installing a negative charge in the CH1 domain. Only a single position, CH1 S183, efficiently rescued the assembly defect of CL V133K. However, variants CL S183E and CL S183D paired effectively with wild-type CL in addition to CL V133K.

Charge repulsion in the constant domains was evaluated to further reduce unwanted chain pairing. Variants with opposite charge, such as CL V133K / CH1 S183E and CL V133E / CH1 S183K, expressed significantly better than placing identical charge into CL and CH1 (e.g., CL V133E / CH1 S183E and CL V133K / CH1 S183K) (Fig. 2C). The charge pair variants, CL V133K / CH1 S183E and CL V133E / CH1 S183K, were selected to steer orthogonal HC/LC pairing to facilitate single-cell expression of BsIgG.

The results from bacterial display experiments indicated that, for efficient orthogonal Fab pairing changes, it can be advantageous to combine variable and constant domain mutations, consistent with reports from others.17 A conserved hydrogen bond between the variable domains involving VH Q39 and VL Q38 was identified. As these residues are distal to the complementary-determining regions (CDRs), little effect upon antigen binding was expected. Indeed, these positions have been previously explored by others to minimize LC homodimer and improve single-chain Fv32 and diabody33 production as well as in orthogonal Fab designs for single-cell BsIgG.17,18 The variant, VL Q38E, negatively affected antibody assembly (Fig. 2D). This assembly defect was rescued with the VH Q39K variant.

Combining variable and constant domain variants promotes efficient production of BsIgG1 in a single cell

Charge pairs in the Fab variable and constant regions and the yt65 CH1/CL design were evaluated separately and in combination for facilitating the efficient assembly of the anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1. Expi293F cells were co-transfected with corresponding HC and LC pairs as for screening of the computationally designed variants (see above). Based on our previous observation that the DNA co-transfection ratio can influence the yield of BsIgG, all variants were screened with LC plasmid ratios from 3:1 to 1:3 to identify the most efficient BsIgG assembly.19 For these experiments, the ratio of HC plasmid was fixed at 1:1. The resultant IgG1 mixture containing BsIgG1 was purified by protein A affinity chromatography and its composition determined by high-resolution liquid chromatography MS analysis with an EMR Orbitrap instrument.19 The MS method was selected over the sandwich ELISA used in screening of computationally designed variants because it allows all IgG1 species present to be identified and quantified.

For the parent anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 with knobs-into-holes mutations in CH3 to direct HC heterodimerization and no engineering of the Fab interfaces, 24.6% BsIgG1 was observed in the mixture of IgG1 species (Table 1). This is consistent with similar expression of the antibody LC and random pairing to HC. The yt65 computational design in the anti-HER2 antibody alone (variant v4) increased BsIgG1 content to ∼60%. Variant v1, with charge-pairs installed at both anti-HER2 and anti-CD3 variable domain interfaces, increased the BsIgG1 content of the parent to ∼56%. For the charge pair design in the constant domains, different results were observed depending on the orientation and the antibody selected. Specifically, variant v2 (anti-CD3 CH1 S183E/CL V133K) improved BsIgG1 content from the parent to ∼47%, whereas variant v3 (anti-HER2 CH1 S183K/CL V133E) did not contribute to correct pairing.

Thus, the variable and constant regions can contribute independently to orthogonal pairing of the anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1. Based on this observation, the variable and constant domain designs were combined to explore further improvement in orthogonal pairing. Initially, the variable domain design was combined with an engineered constant domain interface on a single Fab arm (variants v7, v8 and v9). BsIgG1 assembly was increased to 63–84%. Next, variants with mutations in both variable and both constant domain pairs were evaluated. Both yt65 (variant v11) and charge-pair (variant v10) design benefited from this approach, with BsIgG1 assembly approaching 100%.

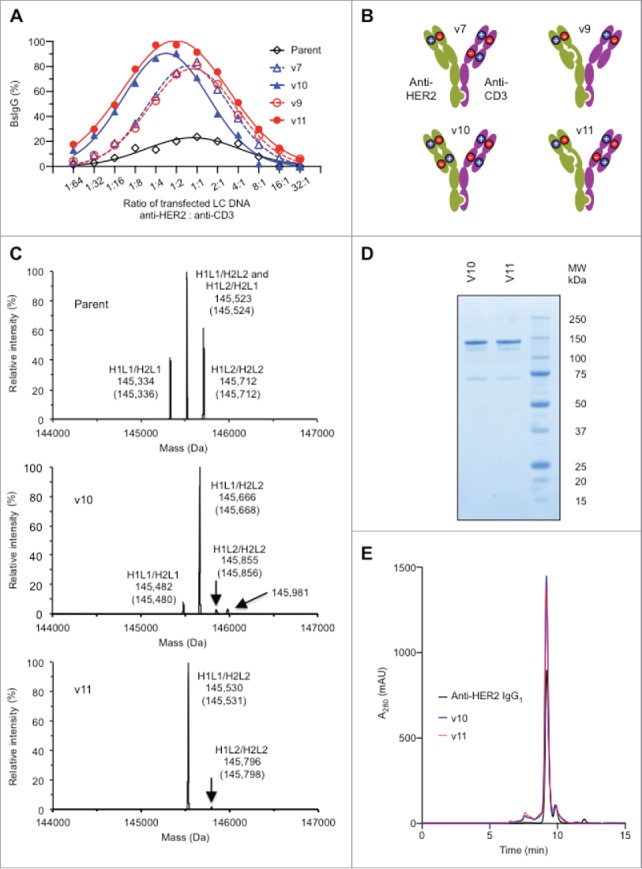

Optimization of BsIgG production and characterization of lead designs

To further optimize the performance of the designs, a broader range of LC DNA ratios was evaluated in the transfection (Fig. 3A). The designs engineered at all four of the domain interfaces in the Fab arms (variants v10 and v11) performed better than related designs engineered at three domain interfaces (variants v7 and v9, respectively) (Fig. 3A and 3B). For example, variant v11 showed a greater percentage BsIgG1 yield than v9 over the entire range of LC ratios. The mass spectra of the variants v10 and v11 with optimized DNA LC ratio in comparison to the parental without Fab engineering highlights the improvement in BsIgG assembly achieved through the designs (Fig. 3C). Further characterization of variants v10 and v11 by SDS-PAGE and size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 3D and 3E) confirmed the high quality of the BsIgG after protein A chromatography. In addition, both variants v10 and v11 displayed expression levels comparable to the parental antibodies (data not shown). Hence, all subsequent experiments were performed only with the v10 and v11 designs (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Optimization of BsIgG production and characterization of lead designs (A) Optimization of BsIgG yield from orthogonal Fab designs by varying the ratio of LC DNA (by weight). The ratio of HC DNAs was fixed at 1:1. (B) Representation of the two most successful orthogonal Fab designs, variants v10 and v11, together with their precursors, variants v7 and v9, respectively (see Table 1). (C) Analysis of BsIgG variants purified by protein A chromatography by liquid chromatography-MS highlighting the increased BsIgG content v10 and v11 compared with the parent with no Fab arm mutations. H1 and L1 represent the HC and LC of anti-HER2, whereas H2 and L2 represent the HC and LC of anti-CD3. The experimentally determined masses and theoretical masses (in parentheses) of each IgG species are indicated. The identity of the minor peak of 145,981 Da in the v10 sample is not yet known. Data shown are for optimized LC ratios. (D) Non-reducing SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed the high purity and efficient formation of the inter-chain disulfide bonds of protein A purified variants v10 and v11. (E) Size exclusion chromatography of protein A purified variants v10 and v11 confirmed the presence of the intact 150 kDa species as well as overall low levels of high and low molecular weight species similar to the bivalent parental anti-HER2 IgG1.

Extension of the orthogonal Fab designs to other human isotypes and mouse

The assembly of anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG for our most successful variants, v10 and v11, were evaluated across different human IgG isotypes to broaden the range of potential therapeutic applications of the designs. Single-cell expression of anti-HER2/CD3 of human IgG2 and IgG4 isotypes without Fab engineering resulted in ∼25% BsIgG (Table 3). This is similar to human IgG1 and consistent with random pairing of HC and LC. Both orthogonal designs (variants v10 and v11) significantly improved the selectivity of chain pairing, approaching 100% anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG for human IgG2 and IgG4. Similarly, variants v10 and v11 both directed the efficient assembly of an anti-HER2/CD3 reverse chimeric BsIgG2a with humanized variable domains and mouse constant domains. In some cases, such as human IgG1 and IgG4, v11 performed slightly better than v10 in facilitating BsIgG assembly, whereas v10 gave slightly higher yield of the reverse chimeric BsIgG2a. Thus, variants v10 and v11 are complementary in their utility.

Table 3.

HC and LC variants to direct the assembly of anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG of different heavy chain isotypes and species. Anti-HER2 and anti-CD3 HC and κ-LC variants were co-transfected into Expi293F cells. The resultant BsIgG-containing mixture was purified from the cell culture harvest fluid by protein A chromatography and then analyzed by liquid chromatography-EMR Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Data shown are for optimized LC ratios. Human IgG1 data are included from Table 1 for comparison. The reverse chimeric BsIgG2a includes humanized variable domains and mouse κ-LC and mouse IgG2a HC. See Table 1 legend for additional details.

| BsIgG (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal pairing variant | Human IgG1 | Human IgG2 | Human IgG4 | Reverse chimeric IgG2a |

| Parent | 24.6 | 24.4 | 22.2 | 21.8 |

| v10 | 91.7 | 97.8 | 90.1 | 100.0 |

| v11 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 97.6 | 91.6 |

Engineered orthogonal Fab designs are broadly applicable across different antibody pairs

The initial evaluation of antibody design was conducted using a single BsIgG1, namely, anti-HER2/CD3. Next, the most successful orthogonal Fab designs (variants v10 and v11) were evaluated across four additional antibody pairs to evaluate if they are broadly applicable. The selected antibody pairs, all with κ-LC, included humanized antibodies (anti-IL-4, anti-IL-13, anti-MET, anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)) as well as human antibodies from phage display libraries (anti-VEGFC, anti-VEGFA, anti-Ang2). Both variants v10 and v11 support the quantitative or near quantitative assembly of BsIgG1 for all antibody pairs (92–100% BsIgG) evaluated following transient coexpression in Expi293F cells (Table 2).

Some antibody pairs without orthogonal mutations in the Fab domains (i.e., parent sequences) displayed random pairing of LC and HC. In contrast, significant preference for cognate HC/LC pairing was observed for two antibody pairs, namely anti-IL-4/IL-13 and anti-EGFR/MET (Table 2). In these cases the parental cognate HC/LC pairing preference was further enhance by installing either the v10 or v11 variants (Table 2).

Structural analysis of engineered Fab fragments

To obtain a detailed molecular understanding of the redesigned Fab interface, X-ray crystallographic structures were determined for three Fab molecules that included the variants incorporated into both arms of the v10 and v11 designs. As the mutations were anticipated to be broadly applicable, anti-HER2 Fab was used as the structural template for all the variants. The first two crystal structures represent the two charge pair-containing Fab arms of the v10 variant, respectively. The EKKE structure (PDB 5TDN, 1.63 Å) contains the VH Q39E CH1 S183K / VL Q38K CL V133E mutations, and the KEEK structure (PDB 5TDO, 1.61 Å) contains the VH Q39K CH1 S183E / VL Q38E CL V133K mutations. Overall, the mutant Fab structures align very closely with the parent Fab structure (PDB 1FVE),34 with a backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.49 Å for the EKKE Fab and 0.47 Å for the KEEK Fab. Thus, the charge-pair modifications did not significantly perturb the structure of the Fab molecule (Fig. 4A and 4B). The X-ray crystallographic structures containing the variable domain modifications do not suggest a clear mechanism for the observed selectivity. The mutated charge residues in the variable domains do not form salt bridges (Fig. 4D and 4E).

Figure 4.

X-ray crystallographic analysis of engineered anti-HER2 Fab fragments (Table S2). (A-C) Crystal structures of engineered variants demonstrating close superposition with the parent anti-HER2 Fab (PDB 1FVE,34 gray). (A) Fab structure of EKKE variant (PDB 5TDN, green) containing the mutations, VH Q39E, CH1 S183K, VLQ38K and CL V133E. (B) Fab structure of KEEK variant (PDB 5TDO, blue) containing the mutations, VH Q39K, CH1 S183E, VLQ38E and CL V133K. (C) Fab structure of EK-yt65 (PDB 5TDP, red) containing the mutations, VH Q39E, CH1 yt65H, VLQ38K and CL yt65L. (D-G) X-ray crystallographic analysis of engineered anti-HER2 Fab fragments highlighting the engineered charge pairs. (D) VH Q39E interactions with VL Q38K in the EKKE variant. (E) VH Q39K interactions with VL Q38E in the KEEK variant. (F) CH1 S183K interactions with CL V133E in the EKKE variant. (G) CH1 S183E interactions with CL V133K in the KEEK variant. (H, I) X-ray crystallographic structure of the CH1/CL interface highlighting the yt65 mutations. (H) The side chains of the mutated residues in the crystal structure of yt65 (red) were superimposed with the structure modeled with Rosetta (pink). (I) The side chains of the mutated residues in the crystal structure of yt65 (red) were superimposed on the corresponding positions in the parent structure (yellow).

Unlike the variable domains, the mutated charge pairs in the constant domains of both structures form salt bridges as expected (Fig. 4F and 4G). The modified residues are located at the center of the CH1/CL interface and have limited solvent exposure. By calculation, the side-chain solvent-accessible surface area is 11.2% for CH1 S183K / CL V133E, and 9.1% for CH1 S183E / CL V133K. We hypothesize that the salt bridges formed in this buried environment compensate for the energetic penalty from desolvation of these charge residues and confer selectivity over the mispaired species, where unsatisfied hydrogen bond donors and acceptors may arise.35,36

The EK-yt65 Fab crystal structure containing the VH Q39E / VL Q38K charge mutations in the variable domains and the computationally designed yt65 mutations in the constant domains was determined to a resolution of 1.72 Å (PDB 5TDP). The overall structure aligns closely with the parent Fab, with an RMSD of 0.46 Å for all Cα atoms (Fig. 4C). The variable domain structure remains the same as in the EKKE structure. When compared with the structural model from the Rosetta program, the constant domains of the yt65 crystal structure displayed almost identical side chain conformations for the mutated residues, except for CH1 S181M (Fig. 4H), which is likely to be more flexible as a consequence of being located at the edge of the interface. Thus, the experimentally determined structure closely matches the design prediction of yt65.

In the constant domains, the side chains of the designed knobs-into-holes modifications, CH1 F170S and CL S176F, are almost completely buried at the interface, with only 5.2% solvent-accessible surface area for CH1 F170S and 3.3% for CL S176F. When the yt65 residues are overlaid with the parent Fab (Fig. 4I), the knob mutation, CL S176F encounters a clash with the CH1 F170 residue in the parent, which indicated the steric hindrance when forming the HCyt65 / LCparent mispair. The other HCparent / LCyt65 mispair, CH1 F170S / CL S176, would suffer instability due to the energetic cost for burying a large cavity at the interface. Besides the designed knobs-into-holes replacements CL S176F and CH1 F170S, Rosetta modeling provided potentially an extra knobs-into-holes solution, CH1 A141I and CL F116A (Fig. 4I). This new knobs-into-holes pair has a size orientation opposite to the former knobs-into-holes, which may further improve the selectivity over the mispaired species.

Single-cell and in vitro-assembled BsIgG1 have comparable physical properties

High thermal stability is desirable for therapeutic proteins because it can contribute to longer pharmaceutical storage stability.37-39 Therefore, any design to produce BsIgG in a single-cell should not compromise the physicochemical stability of the antibody Fab region. Similar to the X-ray crystallographic structures, the thermal stability of the orthogonal designs was also studied using anti-HER2 Fab as the template. The melting temperature (Tm) of each variant as well as the parent Fab was measured using differential scanning calorimetry. The parent anti-HER2 Fab displayed high thermal stability, with a temperature-induced unfolding characterized by a single transition and a Tm of 81.9°C (Fig. S6 and Table 4). The variant EK-yt65 that includes the charge pairs in the variable domains and the computational design in the constant domains has a Tm of 81.4°C, comparable to the parent Fab. Thus, computational redesign of the CH1/CL interface using Rosetta resulted in highly stable Fab interfaces, similar to the parent molecule. Both charge-pair approaches, EKKE and KEEK, have thermal stability that is reduced by ∼4°C. However, the ∼78°C Tm of these Fab fragments is still significantly higher than for some other IgG domains, e.g., the Tm observed for the CH2 domain in a glycosylated IgG1 is ∼70°C.40

Table 4.

Thermal stability and antigen-binding affinity of anti-HER2 variants are comparable to the parent molecules. The Tm values for anti-HER2 variants as Fab fragments were estimated by differential scanning calorimetry at pH 7.4 (Fig. S6). The KD values for the anti-HER2 variants as IgG1 were estimated by surface plasmon resonance at pH 7.4.

| Anti-HER2 variant |

Tm | HER2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VH | CH1 | VL | CL | (˚C) | KD (nM) |

| Parent | Parent | Parent | Parent | 81.9 | 0.63 |

| Q39E | S183K | Q38K | V133E | 77.9 | 0.75 |

| Q39K | S183E | Q38E | V133K | 78.2 | 0.46 |

| Q39E | yt65 | Q38K | yt65 | 81.4 | 0.72 |

Residues VL Q38 and VH Q39 are located distal from the antibody CDR regions, minimizing any potential impact on structural changes to the paratope and antigen binding. The antigen-binding affinities of the three anti-HER2 antibody variants with variable and constant domain mutations are very similar to the parent antibody, as judged by surface plasmon resonance measurements (Table 4). Thus, the mutations do not affect antigen binding. Similar results were obtained with several other BsIgG that include the VL Q38E / VH Q39K and VL Q38K / VH Q39E charge pairs (data not shown).

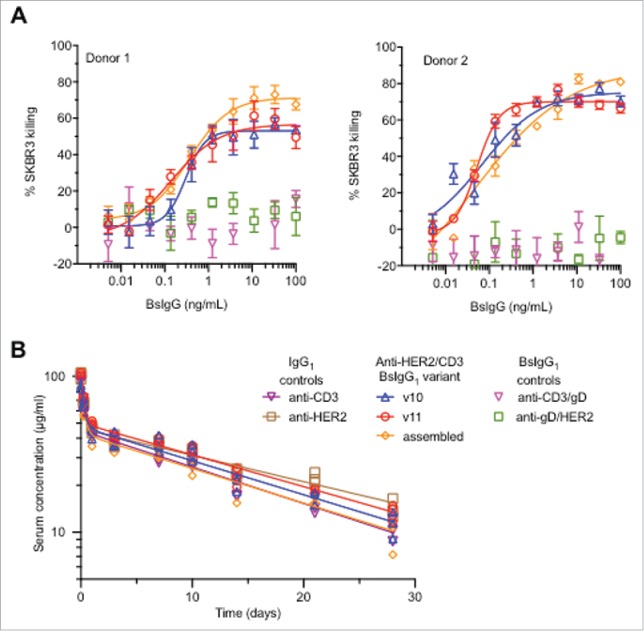

Single-cell and in vitro-assembled BsIgG1 have comparable in vitro biologic activity

Encouraged by the favorable in vitro stability and similar target affinity, we compared the biological activity of the single-cell BsIgG1 with in vitro-assembled anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1. The in vitro-assembled BsIgG has previously been demonstrated to have potent cytotoxic activity with SKBR3 cells that overexpress HER2.23 Variant v10 and v11 single-cell BsIgG1 designs display cytotoxic activity comparable to the in vitro-assembled anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 (Fig. 5A). Both maximum killing activity and EC50 remain unaltered, further confirming that the mutations in the Fab arms do perturb target engagement and biological activity.

Figure 5.

Anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 produced in single cells (variants v10 and v11, see Table 1) have similar in vitro and in vivo properties to BsIgG assembled in vitro following separate expression of half antibodies in two different host cells.12 (A) Cytotoxicity data for anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG-mediated killing of SKBR3 cells in the presence of primary human T cells from two different human donors. Minimal killing was observed for negative control BsIgG1 in which one arm (anti-HER2 or anti-CD3) was replaced by a non-binding arm (anti-gD). (B) Comparable pharmacokinetics of anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG variants following single dose (5 mg/kg) intravenous administration to C.B-17 SCID mice. Controls included were the parent monospecific anti-HER2 and anti-CD3 IgG1. Individual data points (symbols) are shown together with biexponential fits from a two-compartmental model (solid lines).

Single-cell and in vitro-assembled BsIgG1 have comparable pharmacokinetic properties

The single-dose pharmacokinetics of the single-cell anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 variants v10 and v11 were compared with the in vitro-assembled BsIgG1 and the parent monospecific anti-HER2 and anti-CD3 IgG1 in CB-17.SCID mice (Fig. 5B). The mice were dosed intravenously at 5 mg/kg and the pharmacokinetics of the antibodies was studied over 28 days. As the anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 does not cross-react with mouse HER2 or CD3, this provided an opportunity to study and compare the pharmacokinetics of the different molecules in a target-independent fashion. The pharmacokinetic data for each antibody was successfully characterized with both two-compartment and non-compartmental models (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparable single-dose pharmacokinetic parameters of anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 and parental anti-CD3 and anti-HER2 IgG1 in CB-17.SCID mice. Data were subjected to compartmental and non-compartmental analysis (see Materials and Methods). Mean values of pharmacokinetic parameters are shown ( ± standard error of mean). VC, volume of central compartment; Vp, volume of peripheral compartment; CL, weight-normalized clearance from serum, CLD, distribution rate between compartments; t1/2, terminal half-life; and AUC0–28, area-under-the-curve from day 0 to day 28.

| Pharmacokinetic | Anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 |

Parent IgG1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parameter | Single-cell v10 | Single-cell v11 | In vitro-assembled | Anti-CD3 | Anti-HER2 |

| Compartmental analysis | |||||

| VC (mL/kg) | 51.4 ± 3.9 | 47.3 ± 0.94 | 44.9 ± 3.5 | 47.5 ± 2.7 | 48.3 ± 1.1 |

| VP (mL/kg) | 51.1 ± 6.2 | 49.7 ± 2.8 | 67.0 ± 6.5 | 59.9 ± 4.8 | 57.7 ± 3.3 |

| CL (mL/day/kg) | 5.21 ± 0.24 | 4.61 ± 0.22 | 5.85 ± 0.26 | 5.89 ± 0.21 | 4.17 ± 0.22 |

| CLD (mL/day/kg) | 96.6 ± 31.0 | 83.5 ± 8.1 | 133 ± 30 | 123 ± 23 | 99.5 ± 0.5 |

| Non-compartmental analysis | |||||

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 94.5 ± 9.4 | 104 ± 1.9 | 108 ± 12 | 103 ± 7.4 | 101 ± 2.9 |

| t1/2 (days) | 13.3 | 14.7 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 17.3 |

| AUC0–28 (day*μg/mL) | 735 ± 27 | 797 ± 14 | 666 ± 25 | 668 ± 23 | 808 ± 15 |

The pharmacokinetic parameters are broadly similar for the single-cell BsIgG1 (variants v10 and v11) and the in vitro-assembled BsIgG1 with minimal differences (Table 5). Clearance values for single-cell BsIgG1 v11 and v10 and for the in vitro-assembled BsIgG1 are 4.61, 5.21 and 5.85 mL/day/kg, respectively, and similar to the parent anti-HER2 IgG1 (4.17 ml/day/kg) and anti-CD3 IgG1 (5.89 ml/day/kg). Overall, the pharmacokinetic properties of the antibodies tested are comparable.

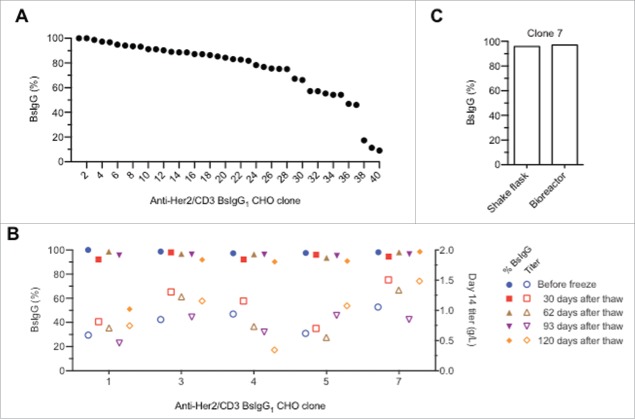

High BsIgG content translates to stable CHO cell line development

We next evaluated if the results of our final design translate from transiently transfected mammalian (Expi293F) cells to stable Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cell lines. This is one of the key requirements for extension of our single-cell BsIgG technology to clinical applications. Cell line development work with variant v10 is presented below. Similar results were obtained with variant v11 (data not shown).

Stable cell line clones that produce BsIgG1 were generated by co-transfecting CHO cells with two plasmids encoding for the HC and LC of either anti-CD3 or anti-HER2. Transfected cells were seeded into glutamine-free medium containing methionine sulfoximine for selection of plasmid transfection. After three weeks, three thousand clones were picked into 96-well plates and assayed for total antibody and bispecific titers. Forty individual clones with high IgG expression levels were selected for fed-batch production assay. After 14 days, the IgG titers were measured and the BsIgG yields were analyzed by MS (Fig. 6A). The cell line development work yielded multiple clones with high bispecific content. About 10% of the clones had quantitative or near quantitative assembly of the bispecific IgG, and >25% of all clones had >90% BsIgG content. The unoptimized shake-flask titers for the top five clones after 14 days culturing ranged from 0.6 to 1.1 g/L. For our experiments with transiently transfected cells, the ratio of the two LC plasmids had to be balanced for optimal results. It appears that the random integration-based cell line development process enables selection of sites that allow balancing of the expression of the four component chains of the BsIgG.

Figure 6.

Efficient production of anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 v10 in stable CHO cell lines. (A) Waterfall plot of individual CHO clones showing the percentage of BsIgG present in the protein A-purified IgG pool as estimated by high-resolution liquid chromatography-MS.19 (B) Shake flask production of BsIgG anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 v10 clones 3, 5 and 7 is stable over time. (C) Similar percentage of BsIgG1 for clone 7 cultured in either a shake flask or bioreactor.

To test the stability of the highest performing clones, the production quality of the top five clones was analyzed periodically over 120 days (Fig. 6B). For at least three of the five clones evaluated (clones 3, 5 and 7), there were no significant changes in BsIgG content or expression titer observed during this time, consistent with clone stability comparable to a regular monospecific IgG. While these experiments were performed with CHO cells grown in shake-flask, a comparative study of clone 7 was done in a bioreactor (Fig. 6C). Comparable BsIgG yields of 96% and 97%, respectively, were observed between shake-flask and bioreactor conditions. These data suggest that suitable clones can be identified for further clinical development.

Discussion

The efficient production of BsIgG in single host cells is highly desirable to support the clinical development of these complex molecules. Here, we describe novel designs to facilitate selective Fab arm assembly in conjunction with previously described knobs-into-holes mutations5,7 for preferential HC heterodimerization. The most successful orthogonal Fab designs, variants v10 and v11, include mutations at the VH/VL and CH1/CL interfaces for both antibodies. These orthogonal Fab designs, in conjunction with CH3 knobs-into-holes mutations, support the efficient production of BsIgG1 (92–100%) in single cells for all antibody pairs with κ-LC tested to date, including the five examples reported here. Importantly for application of the orthogonal Fab designs, they did not significantly perturb the antigen-binding affinity or thermal stability for the antibody tested. Additionally, the single-cell anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 had comparable in vitro biologic properties and in vivo pharmacokinetics as the corresponding in vitro-assembled BsIgG1. The vast majority of antibodies available to us have LC of the κ isotype. For this reason, our top designs (variants v10 and v11) have yet to be tested with antibody pairs that include LC of the λ isotype.

BsIgG of human IgG1 isotype are currently the predominant isotype in clinical applications.41,42 However, other human IgG isotypes, such as IgG2 and IgG4, are also being used for antibody therapeutics to tailor the effector functions for specific clinical applications.41,42 While some approaches for producing BsIgG via in vitro-assembly have been extended to human IgG213 and IgG4,43 the production of isotypes beyond human IgG1 has not yet been reported for other single-cell BsIgG technologies with orthogonal Fab arms. Our designs were evaluated and shown to support efficient production of bispecific IgG of multiple human isotypes namely, IgG1, IgG2 and IgG4. This was expected as a result of the sequence identity of the CH1/CL interface residues between these different human IgG isotypes. However, we also demonstrated that our designs could be used for efficient single-cell production of a reverse chimeric BsIgG2a which shares only 66% and 80% interface sequence identity to human IgG1 CH1 and human κ-LC CL domains, respectively. The significance of this finding is that reverse chimeric (and mouse) IgG2a antibodies are often utilized for preclinical proof-of-concept studies in mice.

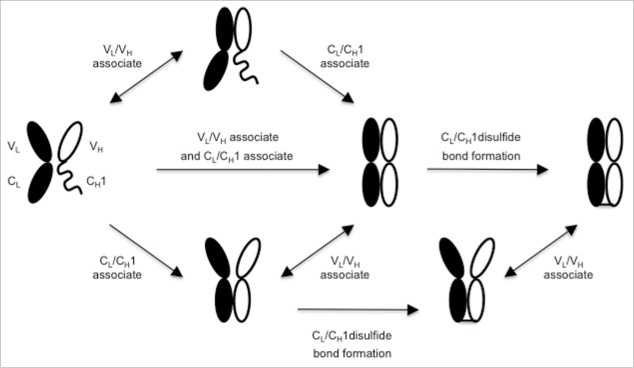

Our observation that mutations at the VH/VL or CH1/CL interfaces can contribute independently to orthogonal pairing provides clues into the assembly sequence of the domains into the intact Fab. Consistent with previous observations using different orthogonal Fab designs, VH/VL mutations in addition to CH1/CL mutations further increase assembly efficiency.17,18 Indeed, for all tested BsIgG, efficient assembly of BsIgG could be accomplished using mutations at both VH/VL and CH1/CL interfaces in both component antibodies. For some BsIgG, it is possible to reduce the number of domain interfaces engineered from four (as for v10 and v11) and still achieve efficient single-cell assembly of BsIgG. For example, anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 variant v12 has mutations at three of the four domain interfaces and demonstrates near quantitative assembly (∼98%) of BsIgG (Table 1).

A priori, assembly of HC and LC of IgG might proceed through one or more of several different alternative pathways (Fig. 7). The VL, VH and CL domains are believed to fold prior to chain assembly, whereas CH1 is unfolded until it dissociates from a chaperone, BiP, and associates with CL.31,44 The first chain assembly step may involve association of VL with VH or CL with CH1, or alternatively simultaneous association of VL with VH and CL with CH1 (Fig. 7). Our observation that mutations at the VH/VL interface can facilitate improved efficiency of BsIgG assembly independent of the constant domain interface suggests that association of the Fab variable and constant domains can occur independently. The contribution of the VH/VL interface mutations appears greater for antibodies that do not display a pre-existing HC/LC pairing preference (data not shown). In addition, the relative folding rates for VH, VL and CL may dictate which interaction occurs first, and is likely influenced by the Fab specific VH and VL sequences.

Figure 7.

Alternative potential assembly pathways for IgG HC and LC. Key steps in the assembly include association of VH and VL, association of CL and CH1 and formation of the disulfide bond between LC and HC. Folding of CH1 requires association with CL.31 Potentially reversible steps are indicated by double-headed arrows.

The concept of independent domain assembly is further supported by our observations in E. coli. Briefly, antibodies with two CL mutations can still associate via their variable domains and bind antigen as suggested by bacterial display. At the same time, CH1/CL interaction and disulfide bond formation apparently did not occur, as evidenced by Western blot data. Once the CL and CH1 domains are associated, then the inter-chain disulfide bond may form. We hypothesize that disulfide bond formation between HC and LC represents a kinetic trap that prevents HC/LC pairs from exchanging partners. If this is the case, then the expression levels of the component chains, as well as the relative association rates of cognate versus non-cognate chains, will impact HC/LC pairings and thus the efficiency of BsIgG assembly. Consistent with this notion, the ratio of input DNAs for the component chains and the resulting altered LC expression levels influenced the efficiency of BsIgG assembly. It is possible that the CH1/CL association is sufficient to allow formation of the disulfide bond between HC and LC, thereby kinetically trapping non-cognate variable domains and precluding them from further productive rearrangements.

A key step in the development of single-cell BsIgG technology is the application to stable cell line development to facilitate the production of large quantities of BsIgG. In particular, the challenge of balancing the expression of the individual chains was reported previously. Others have previously reported preliminary steps toward single-cell production of BsIgG in stable CHO cell lines.3,18 Here, we demonstrate that an orthogonal Fab design (variant v10) in conjunction with CH3 knobs-into-holes mutations can be used for efficient production of a BsIgG1 in a stable CHO cell line. Moreover, we demonstrate that it is readily possible to identify CHO clones with stable IgG titer and percentage BsIgG for at least 120 days post thaw. Such stability studies are a key step in validating single-cell BsIgG platforms for translation to clinical applications. Additionally, both variants v10 and v11 have been successfully used for generating stable CHO cell lines for a second BsIgG1 (anti-tumor antigen/CD3, data not shown). For multiple BsIgG1 studied to date, it has been possible to efficiently purify the BsIgG1 away from small quantities of mispaired IgG1 species by a purification workflow that closely resembles the in-vitro assembled combination of ion exchange and hydrophobic interaction chromatography (data not shown).

For two of five BsIgG1 in this study, a strong preference for cognate HC/LC pairing was observed in the absence of any Fab arm engineering (∼71% BsIgG1 for anti-IL-4/IL-13 and ∼73% BsIgG1 for anti-EGFR/MET), whereas the other three BsIgG1 showed limited or no preference for cognate HC/LC pairing. This cognate HC/LC pairing preference seems to be independent of the framework region because it can occur with BsIgG of identical (anti-EGFR/MET; κ-I, VHIII subgroups) and different framework subgroups (anti-IL-4: κ-1, VH-III; anti-IL-13: κ-4, VH-II). Thus, the CDRs can have a profound effect on the HC/LC pairing preference.

We have identified no antibody pair to date where there is a preference for non-cognate HC/LC pairing. Our data seem broadly consistent with previous studies in which a preference for cognate HC/LC pairing has been observed for some co-expressed IgG pairs17 and no preference in other cases. 45 The frequency and underlying causes of cognate HC/LC pairing preference for BsIgG remains to be investigated. The high resolution liquid chromatography-MS method that we developed previously19 and used in this study seem well-suited to address this question. We selected a BsIgG (anti-HER2/CD3) with random HC/LC pairing for initial evaluation of our orthogonal Fab designs to evaluate the effect of our designs independent of any contribution from intrinsic pairing preference for cognate HC and LC.

Crystallographic analysis of our orthogonal Fab designs revealed structures that overlaid closely (≤ 0.5 Å RMSD for Cα backbone) with the parent anti-HER2 Fab structure. Thus, the designs did not significantly perturb the structure of the parent Fab. Moreover the structures confirmed that engineered mutations were almost completely buried. Clinical investigation is required to test the hypothesis that such mutations with very limited solvent accessibility may pose a low risk for immunogenicity. The one-armed antibody, onartuzumab, containing buried knobs-into-holes HC mutations,46 provides precedence for this concept. In a Phase 1 clinical trial with onartuzumab, the low titer of anti-therapeutic antibodies found in a few (6 of 42) patients were directed against the non-engineered framework region of onartuzumab rather than the knobs-into-holes mutations.47

Strategies successfully used for Fab engineering for single cell BsIgG previously reported by others include either computational design17 or electrostatic steering using pairs of charge residues18 at both VH/VL and CH1/CL interfaces. An additional approach has been to engineer an alternative inter-chain disulfide bond at the CH1/CL interface.3 Our study expands the range of solutions for orthogonal pairing of antibody HC and LC to include minimalistic changes (one pair of mutations per domain/domain interface) through major remodeling of the CH1/CL interface. As compared with the charge pair designs of Liu et al.,18 we present an alternative and simpler solution (variant v10) with fewer (four vs. six) and all different charge pairs using three common residues (VH Q38, VL 38 and CH1 S183) and one different one (CL V133). The CH1/CL computational designs of Lewis et al. facilitated efficient BsIgG assembly when combined with VH/VL mutations but not when used alone.17 In contrast, our computational design in CH1/CL (yt65) increased the percentage of BsIgG from 25% to 59% when used alone (Table 1) with ∼100% BsIgG assembly when combined with VH/VL mutations and mutations at the second CH1/CL interface. However, some caution is needed in comparing orthogonal Fab designs across different studies as different antibodies and analytical tools were used.

In summary, we have developed novel orthogonal Fab designs and demonstrated that they can be used together with knobs-into-holes mutations for efficient single-cell production of BsIgG of different isotypes and species (human IgG1, IgG2 and IgG4; reverse chimeric IgG2a). Additionally, we demonstrated that our designs can be used for efficient single-cell production of BsIgG in stable CHO cell lines. The single-cell bispecific IgG designs developed here may be broadly applicable for applications in biotechnology, including for drug development.

Materials and methods

Antibody constructs

The Kabat48 and EU49 numbering schemes were used for antibody variable and constant domain residues, respectively. For expression in HEK293T, Expi293F or CHO cells, the antibody HC in this study included a mutation, N297G, to preclude N-linked glycosylation and a deletion of the C-terminal lysine (ΔK447) to reduce product heterogeneity for reliable MS-based quantification as previously described.19 Additionally, Fc aglycosylation will attenuate Fc-mediated effector functions.50 Selective HC heterodimerization was achieved by installing knob (T366W), and hole (T366S:L368A:Y407V) mutations.5 Antibody genes were cloned into E. coli or mammalian expression vectors that have been previously described.29

Antibody expression in E. coli and purification

Expression of antibodies in E. coli and subsequent analysis by bacterial display or Western blotting was performed as previously described.29 For mammalian expression, plasmids coding LC and HC were mixed according to the described weight ratios and co-transfected into Expi293F cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Antibody expression was performed at the 30 mL scale followed by protein A affinity chromatography using MabSelect SuRe (GE Healthcare) purification as reported previously.51 Purification yields were calculated based on an extinction coefficient of 1.4 at a wavelength of 280 nm.

Gene synthesis, expression and purification of computationally-designed variants

Genes encoding selected computational designs of the anti-HER2 CH1/CL variants were obtained by gene-synthesis (GeneWiz). LC variants were cloned as KpnI/HindIII fragments into expression vector pRK5 humAb4D5–820 LC and HC variants were cloned as ApaI/NdeI fragments into expression vector pRK5 humAb4D5–8 HC.20 Single-cell production of BsIgG for the variants with partner anti-CD3 antibody, humAbUCHT1v9,21 was performed by co-transfecting 4 plasmids, each carrying a LC or a HC gene of the test pair, into HEK239T cell (1 mL culture, 96-well deep well plate). Antibody expression was performed for 7 days at 37 °C with vigorous shaking. The culture supernatants were collected and incubated with 300 μL MabSelect SuRe resin with vigorous shaking overnight. The resin was then transferred to filter plates and washed with 20 times the resin bed volume. The bound IgG was then eluted with 50 mM phosphoric acid pH 3.0 and neutralized (1:20) with 20x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 11.0. The IgG protein was then sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter.

Sandwich ELISA assay to determine bispecific IgG content from single cell co-expression

The BsIgG standard used in the sandwich ELISA as benchmark for the computationally designed variants comprised a humanized anti-HER2 antibody (humAb4D5–8)20 as the knob arm and a humanized anti-CD3 antibody (humAbUCHT1v9)21 as the hole arm. The BsIgG standard was generated by expressing each arm in HEK293T cell separately and then annealing them in vitro.52 The BsIgG content from single host cell co-expression were determined by sandwich ELISA. Antibody binding to both HER2 and CD3 antigens is required to generate a signal in the sandwich ELISA (data not shown). The ELISA signal strength of a fixed amount of total IgG from the single cell coexpression was then benchmarked against that of the BsIgG standard to determine the BsIgG content in the mixture. Briefly, ELISA plates (MaxiSorp, Nunc) were coated with HER2 extracellular domain (ECD) antigen at 1 µg/mL in PBS and incubated at 4°C overnight. The antigen-coated plate was then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBST (1x PBS plus 0.05% Tween-20) for 1 h. Test samples were diluted in the same blocking buffer in a separate 96-well plate and kept at room temperature for 1 h. The blocked samples were transferred (100 µL/well) to the HER2-coated (blocked) plate and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The plate was washed 15 times with PBST. The second antigen, CD3-biotin, was then added to plate at 100 µL/well (0.5 µg/mL CD3-Biotin in blocking buffer) and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The plate was washed 15 times with PBST. Streptavidin-HRP (Thermo Fisher) was added at 100 µL/well (0.1 µg/mL) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The plate was washed 15 times with PBST. Horseradish peroxidase substrate, Sureblue Reserve TMB solution (KPL), was added at 100 µL/well. Color development was stopped by addition of an equal volume of 1.0 M phosphoric acid (H3PO4). The absorbance of the samples on the plate was then read at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Quantification of bispecific IgG by high resolution mass spectrometry

An Exactive Plus Extended Mass Range Orbitrap high resolution Mass Spectrometer (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) was used for all mass measurements under conditions previously described.19 The samples were directly infused via nanospray ionization using a Triversa Nanomate® (Advion, Inc.) after off-line buffer-exchange using Micro Bio-Spin™ 6 columns,58 or were subjected to online reversed phase chromatography (RPLC) via an UltiMate 3000 RSLC liquid chromatography system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a MabPac RP column (2.1 mm × 50 mm).19 Spectra were visualized and manually interpreted using Xcalibur Qual Browser (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and mass spectrum deconvolution was performed with Thermo Protein Deconvolution 4.0. The relative quantification was based on the intensity value calculated by Protein Deconvolution 4.0 of each individual peak vs. total summed intensities.19 For calculation of BsIgG with correctly paired LC, masses corresponding to half antibodies and HC homodimers were excluded. The isobaric mixture containing BsIgG and double LC scrambled IgG was differentiated by using statistical estimation of the abundance of the double mispaired LC species as described previously.19

Protein production of anti-HER2 Fab variants

The anti-HER2 LC and HC were separately inserted into the pRK5 mammalian expression vector. Amino acid sequences and structure were deposited into the PDB with accession codes 5TDN, 5TDO and 5TDP. To express the Fab, equal weight amounts of LC and HC DNA were mixed and transfected into Expi293F cells according to the manufacturer's protocol (Thermo Fisher). Anti-HER2 Fab was recovered from the conditioned media using Capto L resin (GE Healthcare) and further purified by cation exchange chromatography using a MonoS column (GE Healthcare).

Crystallization of anti-HER2 Fab variants and structure determination

Purified anti-HER2 Fab proteins were concentrated to 10 mg/mL for crystallization in 10 mM Tris pH 7.0, 5 mM NaCl. Crystals of all variants were grown at 20% (w/v) PEG 3350, 0.04 M citrate acid, 0.06 M BIS-TRIS propane using the vapor diffusion method. For data collection, crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant solution containing the mother liquor plus 20% (v/v) glycerol before flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K with a beam wavelength of 1 Å at the Advanced Light Source of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Data reduction was performed with HKL2000 and Scalepack.53 All crystals of anti-HER2 Fabs belong to the space group of P1 and contain two Fab molecules per asymmetric unit cell. Structures were solved by molecular replacement using PDB 1FVE34 as the search model. Manual model building was performed with Coot, and refinement was done using PHENIX. The structure factors and final models of anti-HER2 Fab variants, EKKE, KEEK and EK-yt65, were deposited into the PDB with the accession codes, 5TDN, 5TDO and 5TDP, respectively.

Surface plasmon resonance

The binding affinities of anti-HER2 variants for HER2 extracellular domain were determined at 25°C using a Biacore T200 (GE Healthcare). A saturated amount of anti-human Fc monoclonal antibody was immobilized onto a CM5 biosensor chip by following the product instructions. Anti-HER2 variants were expressed as human IgG1 and purified by protein A affinity chromatography. About 300 resonance units of different anti-HER2 IgG1 variants were captured in each flow cell. HER2 antigens of various concentrations (2.4 nM, 5.3 nM, 7.1 nM, 16 nM, 21.3 nM, 32 nM and 64 nM) in the HBSP buffer (Biacore, GE Healthcare) were injected at a flow rate 30 μL/min. After each binding cycle, flow cells were regenerated using 3 M MgCl2. Kinetic analyses were performed using the T200 evaluation software using the 1:1 binding model to obtain the kinetic and affinity constants.

Thermostability of Fab fragments by differential scanning calorimetry

Purified anti-HER2 Fab were adjusted to a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL, and dialyzed extensively against PBS (pH 7.4). Buffer from the last dialysis was used as the reference buffer for the measurements. Differential scanning calorimetry experiments were performed on a MicroCal VP-DSC microcalorimeter (Malvern Instruments). Thermal scanning was performed from 20–95°C at a rate of 1°C/min. Data were analyzed using the Origin 7 software (OriginLab).

In vitro cytotoxicity assays

Anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 were evaluated for in vitro cytotoxicity with SKBR3 cells that overexpress HER2 in the presence of primary human T cells as described previously.23 Briefly, CD8 positive cells were purified from healthy donor blood by column purification on Automax. Cells were plated in effector to target ratio (E:T) of 5:1 in and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. CD8 positive cells were washed twice with 150 μL PBS. Then 150 μL of Cell Titer-Glo reagent (Promega) was added and plates were read on an EnVision plate reader (Perkin Elmer).

Pharmacokinetics of BsIgG in SCID mice

This study was designed to evaluate and compare the pharmacokinetics of single-cell anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 (variants v10 and v11) with corresponding in vitro-assembled anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 and parental bivalent (anti-CD3 and anti-HER2) IgG1 in CB-17.SCID mice. These antibodies are non-reactive toward mouse CD3 and HER2 receptors, so mice may be used to evaluate non-specific clearance of these antibodies. Five groups of female CB-17.SCID mice (n = 9; Charles River Laboratories) were given a single intravenous dose of BsIgG1 (v10 and v11) or parental (anti-CD3 and anti-HER2) IgG1 each at a dose level of 5 mg/kg. The animals were from 6 to 8 weeks old and weighed ∼18.3–21.6 g at the initiation of the study. Blood samples were collected via the femoral vein at various time points (three replicates for each time point) for up to 28 days. Total antibody concentrations in serum were determined by a GRIP ELISA (plate coated with anti-human IgG and detected with anti-human IgG) with the limit of detection of 15.6 ng/mL and used for pharmacokinetic evaluations. Non-compartmental analysis parameters were estimated using a non-compartmental model with intravenous bolus input model and sparse sampling [Model Type Plasma (200–202)] (Phoenix™ WinNonlin®, Version 6.4; Pharsight Corporation). Two-compartmental model parameters were estimated using Simbiology®, in MATLAB® 2016a with the combined error model described in the software. Nominal sample collection time and nominal dose concentrations were used in the data analysis. All pharmacokinetic analysis was based on the naïve pool of individual animal data. All procedures were approved by and conformed to the guidelines and principles set by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Genentech and were performed in a facility accredited by AAALAC.

Stable cell line development

Two separate expression plasmids were constructed to generate stable cell lines expressing the bispecific anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG1 in a single-cell. Each plasmid contains the DNA for the HC and LC pair of either the knob or hole half-antibody under the control of cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene promoter and enhancer. Each cytomegalovirus transcriptional start site is followed by splice donor and acceptor sequences, which define introns that are removed from the final transcripts.54 The glutamine synthetase gene is present in each expression plasmid under the control of SV40 early promoter and enhancer, and is used as the selection marker for stable cell line development.55 CHO K1 cells were cultured in a proprietary DMEM/F12-based medium in shake flask vessels at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were passaged with a seeding density of 3 × 105/mL, every 3 to 4 days. CHO cells were transfected with the two plasmids using electroporation according to the manufacturer's recommendation (MaxCyte). Transfected cells were centrifuged and seeded into DMEM/F-12-based selective (glutamine-free) medium with various concentrations of methionine sulfoximine. About three weeks after seeding, individual colonies were picked into 96-well plates.56 The supernatant of picked colonies was evaluated for total IgG production and BsIgG1 content based on ELISA analysis. Top clones were scaled-up to produce antibody for bispecific level analysis using a 14 day fed-batch culture process with a temperature shift to 35°C on day 3.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All authors are current or former employees of Genentech, Inc., which develops and commercializes therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Research Materials Group in the Early Stage Cell Culture Department at Genentech for mammalian antibody expressions and the Antibody Production Group in the Antibody Engineering Department for antibody purification. We thank Pamela Chan for assistance with the anti-HER2/CD3 BsIgG sandwich ELISAs and Hok Seon Kim for the design of the decoupled CL format that was used in Fig. S5. We thank Jian Payandeh and Weiru Wang for X-ray crystallographic data collection. The Advanced Light Source at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is acknowledged for providing a synchrotron X-ray source for collecting crystallographic data. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the US. Department of Energy under contract number. DE-AC02–05CH11231.

Funding

This work was funded by Genentech, Inc.

References

- 1.Brinkmann U, Kontermann RE. The making of bispecific antibodies. MAbs 2017; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiess C, Zhai Q, Carter PJ. Alternative molecular formats and therapeutic applications for bispecific antibodies. Mol Immunol 2015; 67:95-106; PMID:25637431; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazor Y, Oganesyan V, Yang C, Hansen A, Wang J, Liu H, Sachsenmeier K, Carlson M, Gadre DV, Borrok MJ, et al.. Improving target cell specificity using a novel monovalent bispecific IgG design. MAbs 2015; 7:377-89; PMID:25621507; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/19420862.2015.1007816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suresh MR, Cuello AC, Milstein C. Bispecific monoclonal antibodies from hybrid hybridomas. Methods Enzymol 1986; 121:210-28; PMID:3724461; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0076-6879(86)21019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwell S, Ridgway JB, Wells JA, Carter P. Stable heterodimers from remodeling the domain interface of a homodimer using a phage display library. J Mol Biol 1997; 270:26-35; PMID:9231898; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merchant AM, Zhu Z, Yuan JQ, Goddard A, Adams CW, Presta LG, Carter P. An efficient route to human bispecific IgG. Nat Biotechnol 1998; 16:677-81; PMID:9661204; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt0798-677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridgway JB, Presta LG, Carter P. 'Knobs-into-holes' engineering of antibody CH3 domains for heavy chain heterodimerization. Protein Eng 1996; 9:617-21; PMID:8844834; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/protein/9.7.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaughan TJ, Williams AJ, Pritchard K, Osbourn JK, Pope AR, Earnshaw JC, McCafferty J, Hodits RA, Wilton J, Johnson KS. Human antibodies with sub-nanomolar affinities isolated from a large non-immunized phage display library. Nat Biotechnol 1996; 14:309-14; PMID:9630891; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt0396-309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruggemann M, Osborn MJ, Ma B, Hayre J, Avis S, Lundstrom B, Buelow R. Human antibody production in transgenic animals. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2015; 63:101-8; PMID:25467949; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00005-014-0322-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunasekaran K, Pentony M, Shen M, Garrett L, Forte C, Woodward A, Ng SB, Born T, Retter M, Manchulenko K, et al.. Enhancing antibody Fc heterodimer formation through electrostatic steering effects: applications to bispecific molecules and monovalent IgG. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:19637-46; PMID:20400508; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.117382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labrijn AF, Meesters JI, de Goeij BE, van den Bremer ET, Neijssen J, van Kampen MD, Strumane K, Verploegen S, Kundu A, Gramer MJ, et al.. Efficient generation of stable bispecific IgG1 by controlled Fab-arm exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:5145-50; PMID:23479652; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1220145110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiess C, Merchant M, Huang A, Zheng Z, Yang NY, Peng J, Ellerman D, Shatz W, Reilly D, Yansura DG, et al.. Bispecific antibodies with natural architecture produced by co-culture of bacteria expressing two distinct half-antibodies. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31:753-8; PMID:23831709; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt.2621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strop P, Ho WH, Boustany LM, Abdiche YN, Lindquist KC, Farias SE, Rickert M, Appah CT, Pascua E, Radcliffe T, et al.. Generating bispecific human IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies from any antibody pair. J Mol Biol 2012; 420:204-19; PMID:22543237; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Kreudenstein TS, Escobar-Carbrera E, Lario PI, D'Angelo I, Brault K, Kelly J, Durocher Y, Baardsnes J, Woods RJ, Xie MH, et al.. Improving biophysical properties of a bispecific antibody scaffold to aid developability: quality by molecular design. MAbs 2013; 5:646-54; PMID:23924797; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/mabs.25632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu C, Ying H, Grinnell C, Bryant S, Miller R, Clabbers A, Bose S, McCarthy D, Zhu RR, Santora L, et al.. Simultaneous targeting of multiple disease mediators by a dual-variable-domain immunoglobulin. Nat Biotechnol 2007; 25:1290-7; PMID:17934452; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]