ABSTRACT

In chronic inflammatory airway diseases, mucins display disease-related alterations in quantity, composition and glycosylation. This opens the possibility to diagnose and monitor inflammatory airway disorders and their exacerbation based on mucin properties. For such an approach to be reasonably versatile and diagnostically meaningful, the mucin of interest must be captured in a reliable, patient-independent way. To identify appropriate mucin-specific reagents, we tested anti-mucin antibodies on mucin-content-standardized, human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples in immunoblot assays. All commercially available monoclonal antibodies against the major airway mucin MUC5AC were screened, except for those with known specificity for carbohydrates, as glycosylation patterns are not mucin-specific. Our results indicated considerable inter-patient and inter-antibody variability in mucin recognition for all antibodies and samples tested. The best results in terms of signal strength and reproducibility were obtained with antibodies Mg-31, O.N.457 and 45M1. Additional epitope mapping experiments revealed that only one of the antibodies with superior binding to MUC5AC recognized linear peptide epitopes on the protein backbone.

KEYWORDS: Asthma, chronic inflammatory airway diseases, COPD, MUC5AC, mucin capturing, mucin quantification, mucus

Abbreviations

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Introduction

The epithelial lining of the mucosae, among them the conducting airways of the respiratory tract, is covered with a complex aqueous, viscoelastic mucus that is highly variable in composition, properties and functions.1,2 In addition to physically protecting the epithelial cell barrier, mucus serves as a platform for the first, innate defense reaction against invaders,3,4 and in the airways it helps to remove trapped foreign matter by a process called mucociliary clearance.5,6

However, aberrant synthesis and overexpression/-secretion of mucus in chronic inflammatory airway diseases like asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cystic fibrosis (CF) may convert the protective role of mucus into a detrimental one. In asthma, a major cause of chronic illness worldwide with >80% increase in prevalence in all age and ethnic groups over the past two decades, airway remodeling with submucosal gland hypertrophy and goblet cell hyperplasia are major pathophysiological features.1 Hyperplasias with an up to 30-fold increase in percentage of goblet cells causing massive mucus overproduction and secretion have been reported for patients who died of status asthmaticus.7 In combination with bronchoconstriction and impaired ciliary function, which derogate mucus clearance, this results in chronic airway hyperresponsiveness and obstruction thereby provoking frequent hypoxemic and dyspneic episodes.5,7,8 Goblet cell hyperplasia, mucus overproduction and airway obstruction can also be detected in CF and COPD.1 While CF is a rare inherited disease with a prevalence of less than 0.1% in the European Union,9 COPD is an acquired inflammation mostly caused by aerogenic noxae such as fine dust and smoke, and it affects almost 8% of the adult European population.10 Proteases released by recruited neutrophils and macrophages usually augment inflammation,11 damage the airway epithelium and lead to airway remodeling again accompanied by mucus overproduction, changes in its rheological properties and, subsequently, airway obstruction.12,13 Yet, aberrant mucus tethered to epithelium and not properly removed by the mucociliary escalator not only constitutes a physical barrier constraining the airflow, it also provides a perfect habitat for microbial growth and may act as a reservoir for bacteria and viruses, thereby fostering prolonged or even chronic infections. Such infections are feared by asthmatic, CF and COPD patients because they frequently lead to acute worsening of the chronic stage, a status termed exacerbation.1,2,14,15 Exacerbations are not only life-threatening events, they also promote disease progression and thus ought to be prevented in diseased individuals by all means.

On the way to understanding and counteracting disease progression and exacerbations, a profound knowledge and thorough monitoring of mucus aberration may be a key requirement. Major constitutive components of the mucus are the mucins, a family of large glycoproteins. At least 18 different human mucins, which are characterized by typical tandem repeat sequences and multiple O-glycosylation sites in the central domain of the molecule, have been identified so far. Posttranscriptional glycosylation results in a huge, highly variable carbohydrate proportion (up to 90% of weight) and highly negative charge of the mucins. Mucin monomers have a long, thread-like structure and can be as large as 2,000 kDalton. While the central part primarily functions as scaffold for the carbohydrate structures, the amino- and carboxy-terminal parts play important roles in mucin localization (secreted vs. membrane-tethered) and multimerization. Cysteine residues in the terminal domains of secreted mucins allow the formation of disulfide bonds between monomers, resulting in the generation of interwoven networks up to 50 mega Dalton in size and 10 µm in length.1,2

In chronic inflammatory airway diseases, elevated levels of, as well as structural changes in, the mucins can be observed and may be indicative for the disease status or an upcoming exacerbation. The core structures of mucin O-glycans4 as well as terminal O-glycosylation16,17 can be modified, and hence could influence physical (e.g., viscosity) and biological (e.g., binding to pathogens) properties of mucins.1,2 For CF, a correlation between severity of airway infections and changes in glycosylation pattern has been described,18 and, in an asthma mouse model, an altered glycosylation is detectable after the induction of experimental asthma.19 The two major secreted, gel-forming human airway mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B were reported to be elevated in chronic inflammatory airway diseases compared with healthy individuals,8,20–24 usually in an increased MUC5B/MUC5AC ratio.1,21,25,26

In spite of the high diagnostic potential of the mucins, studies performed so far mainly focused on the general expression and localization of mucins, and did not provide specific data regarding whether the alterations observed were based on overproduction, modified distribution/composition or biochemical variations of one or more specific mucins.1 Additionally, examination of quantitative and structural changes in different phases of chronic inflammatory airway diseases, especially during exacerbation, is scarce. To close this gap, a patient- and disease status-independent analysis of specific mucins would be necessary. A reliable definition of alterations in the mucins between healthy, (mildly) diseased and (impending) exacerbatic status may provide valuable correlations, and the detection of such changes as early as possible can allow prevention or alleviation of exacerbations in chronic inflammatory airway diseases. Such an approach requires that mucins be captured quantitatively from a patient sample and be comprehensively characterized in terms of amount and structure. Regrettably, reliable tools to do so are currently limited. In this study, we therefore endeavored to characterize all commercially available antibodies to the major human airway mucin MUC5AC in terms of reliable, patient-independent performance and epitope recognition.

Results

MUC5AC content of bronchoalveolar lavage fluids of different individuals

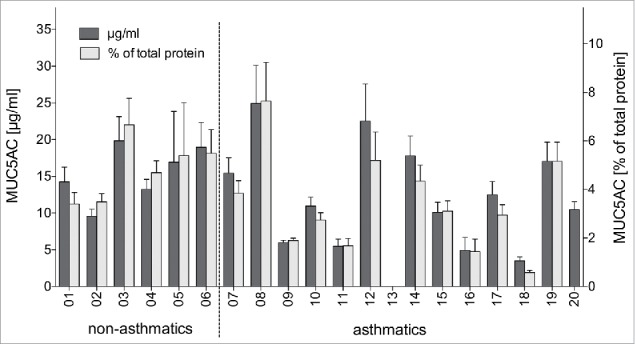

The characterization of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against MUC5AC was done in an immunoblot setup with human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples from six healthy and 14 asthmatic individuals. To compare the antibodies for their binding to the MUC5AC of the different donors, the human BALF samples used for the investigations first had to be standardized. The total protein content of the raw BALF samples varied substantially (range 143 mg/ml to 604 mg/ml, median 330 mg/ml) (Table 1), which indicated that differences in the MUC5AC content can also be expected. To exclude any potential influence of such fluctuations in mucin concentration on our antibody binding results, we pre-quantified the MUC5AC content in all BALF samples by a commercially available MUC5AC assay with internal MUC5AC standard. The MUC5AC concentration in the samples ranged between 5 and 25 µg/ml (Fig. 1), accounting for up to 8% of the total protein amount, but did not differ significantly between non-asthmatics and asthmatics (p > 0.05; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test for MUC5AC concentrations and percentage of total protein). The BALF #13 with no detectable MUC5AC was excluded from calculations, as well as from subsequent analyses of antibody binding.

Table 1.

Features of the BALF samples from asthmatic and non-asthmatic patients.

| Sample # | Age | Diagnosis | Comment | Steroid usage | Total protein (mg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 58 | non-asthmatic | – | 420 | |

| 02 | 57 | non-asthmatic | – | 274 | |

| 03 | 80 | non-asthmatic | – | 298 | |

| 04 | 51 | non-asthmatic | – | 282 | |

| 05 | 68 | non-asthmatic | – | 314 | |

| 06 | 77 | non-asthmatic | + | 345 | |

| 07 | 65 | bronchial asthma | – | 402 | |

| 08 | 43 | bronchial asthma | not controlled | + | 326 |

| 09 | 55 | bronchial asthma | – | 314 | |

| 10 | 53 | bronchial asthma | – | 400 | |

| 11 | 43 | bronchial asthma | allergic background | + | 328 |

| 12 | 72 | bronchial asthma | exacerbation | – | 433 |

| 13 | 70 | bronchial asthma | + | 143 | |

| 14 | 40 | bronchial asthma | – | 410 | |

| 15 | 62 | bronchial asthma | exacerbation | – | 326 |

| 16 | 49 | bronchial asthma | – | 342 | |

| 17 | 72 | bronchial asthma | severe | + | 424 |

| 18 | 45 | bronchial asthma | allergic, exacerbation | + | 604 |

| 19 | 70 | bronchial asthma | – | 330 | |

| 20 | 55 | bronchial asthma | allergic | – | n.d. |

Figure 1.

Quantification of MUC5AC in human BALF samples. MUC5AC content (dark bars) and relative MUC5AC amount in relation to total protein content (light bars) as determined by commercial MUC5AC quantitation kit (mean + SD from two independent experiments).

Reactivity of different anti-MUC5AC antibodies against MUC5AC in different BALF samples

The ability of the commercially available monoclonal anti-MUC5AC antibodies (Table 2) to recognize airway MUC5AC was investigated using immunoblots. MUC5AC-equalized amounts of BALF samples from asthmatic and non-asthmatic individuals were directly applied to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with the respective antibodies. Each membrane carried the identical quantity of BALF samples with the same amounts of mucin in an identical pattern, allowing a direct comparison of antibody performances. The results of the immunoblots are depicted in Fig. 2. The BALF sample #18 was excluded from this first set of experiments due to the low amount of MUC5AC in this sample.

Table 2.

Summary of monoclonal antibodies against MUC5AC.

| Clone | Immunogen | Order number | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLH2 | Synthetic peptide (Tandem repeat) | MONX10516 | Monosan |

| 2A4 | Recombinant MUC5AC protein fragment | H00004586-M04 | Abnova |

| 2H7 | Recombinant MUC5AC protein fragment | H00004586-M07 | Abnova |

| 1–13M1 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | MON 6055 | Monosan |

| 2–11M1 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | MON 6056 | Monosan |

| 2–12M1 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | MON 6057 | Monosan |

| 9–13M1 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | MON 6060 | Monosan |

| 45M1 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | MON 6058 | Monosan |

| 58M1 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | MON 6059 | Monosan |

| MRQ-19 | Not stated | MON 3316 | Monosan |

| Mg-31 | Native purified human MUC5AC | MAB1466 | Abnova |

| 2×123 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | sc-71620 | Santa Cruz Bio |

| 2Q445 | Synthetic peptide (Tandem repeat) | sc-71621 | Santa Cruz Bio |

| O.N.457 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | M4701–05X | US Biologicals |

| O.N.458 | Mucin preparation isolated from ovarian cyst fluid | M4701–06X | US Biologicals |

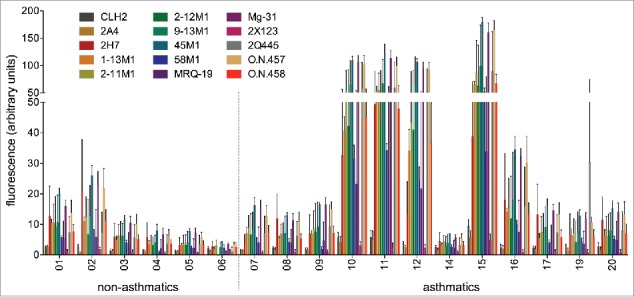

Figure 2.

Performance of 15 monoclonal anti-MUC5AC antibodies on MUC5AC-content-matched human BALF samples. 150 ng MUC5AC-containing BALF samples from six non-asthmatics and twelve asthmatics were dotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Each immunoblot was incubated with a different primary anti-MUC5AC antibody and the same fluorophore-labeled secondary antibody. Fluorescence signals were quantified with the LI-COR Odyssey Classic system. Background fluorescence of the membrane was measured and subtracted from the values of the BALF sample dots. Depicted are the mean values of three independent experiments with standard deviation.

The values of the negative controls (no or irrelevant primary antibody) were reproducibly near zero, indicating no background due to nonspecific binding of the fluorophore-labeled secondary antibody. When analyzing the MUC5AC data sets, we found that some, but not all of the samples from asthmatics are recognized better than samples of non-asthmatics by most of the antibodies. Vice versa, some of the antibodies are capable of detecting most, but not all of the BALF samples better than other antibodies. Overall, a comparatively high inter-antibody and inter-patient variability was observed, and none of the antibodies is able to detect the adjusted mucin amounts in all BALF samples with equal performance. Moreover, the standard deviation obtained in three independent experiments is quite high for some antibodies (Fig. 2). We attribute these variations at least in part to a loss of activity of the antibodies over time due to sub-optimal storage conditions.

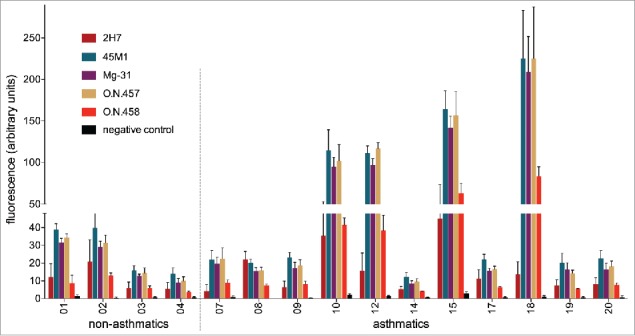

To identify potentially diagnostically valuable anti-MUC5AC antibodies, the five most promising candidates of the first immunoblot experiments were re-evaluated with new batches of antibody, avoiding extended storage time to minimize the stability problem of the antibodies. Besides the three antibodies with the highest overall signal in the first round of immuno-detection (45M1, Mg-31 and O.N.457), the antibody O.N.458 was selected for re-testing on the basis of its good balance between signal strength and reproducibility, i.e., it exhibited a rather uniform detection of the BALF MUC5AC in repetitive experiments. Antibody 2H7 was chosen because of its good performance in the first immunoblot prior to the loss of activity in the subsequent assays (data not shown).

Due to the limited availability of the human BALF material, only four samples of non-asthmatics and eleven samples of asthmatics could be used for the second round of analysis, which now also included sample #18, which had previously been excluded due to its low MUC5AC content. The experimental design was identical to before, and negative controls with irrelevant or no primary antibody again did not display values above background. Substantiating our results from the first analysis round, four of the samples from asthmatics exhibit a visibly higher reactivity with the mAbs than the other samples (Fig. 3). Indeed, for all five antibodies tested, the signal intensity of the four “highly reactive” BALF samples #10, 12, 15 and 18 of asthmatics differs significantly from the seven “low signal” samples of the other asthmatics or from all eleven “low signal” samples (including the ones from non-asthmatic individuals) (p < 0.05 for 2H7 and p < 0.01 for the other antibodies; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the “low signal” samples of non-asthmatics and asthmatics (always p > 0.05; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test).

Figure 3.

Performance of the five most promising monoclonal anti-MUC5AC antibodies on human BALF samples. 150 ng MUC5AC-containing BALF samples from four non-asthmatics and eleven asthmatics were dotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Each immunoblot was incubated with one of five anti-MUC5AC antibodies or one irrelevant antibody. Binding of the primary antibodies was detected with a fluorophore-labeled secondary antibody. Fluorescence signals were quantified with the LI-COR Odyssey Classic system. Background fluorescence of the membrane was measured and subtracted from the values of the BALF sample dots. Mean values of three independent experiments with standard deviation are shown.

An unwanted “matrix” effect of varying amounts and composition of other proteinaceous components in the BALFs on the detectability of MUC5AC in the different samples was ruled out by performing an analogous determination of control protein. The 15 BALF samples used before were supplemented with equal amounts of ovalbumin (OVA) and analyzed in an identical immunoblot procedure as before with an anti-OVA antibody. Although some variation in the amount of OVA detected was obtained, there was no correlation between the signal intensities obtained for OVA and for MUC5AC, and no significant difference in OVA detection between BALF samples with high and with low MUC5AC content (p > 0.05; two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test) (data not shown).

Peptide epitope mapping of anti-MUC5AC antibodies

Set-up of a practicable diagnostic mucin test requires reagents that can react with the mucin of interest in a reliable way, with little or no inter-patient and inter-sample variability. This argues against antibodies directed toward carbohydrate structures, as the mucin glycosylation pattern is prone to variation, or toward conformational epitopes in the protein, as those are likely to be disrupted under denaturing and reducing conditions, procedures often required for the recovery of mucins from patient material such as sputum. For that reason, we concluded that linear peptide epitopes within the mucin protein backbone would be more suitable candidates for a patient-independent, antibody-based capturing or detection of MUC5AC.

We therefore investigated whether linear peptide epitopes present in the MUC5AC protein sequence are recognized by any of the five anti-MUC5AC antibodies that were most promising in the immunoblot system.

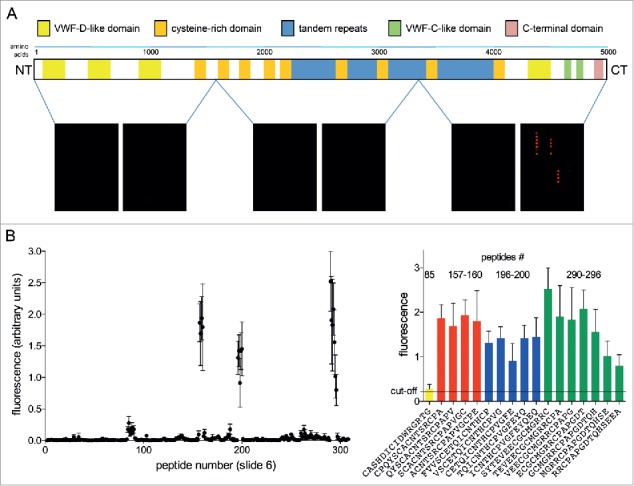

Of the five antibodies subjected to epitope mapping analysis, only antibody 2H7 was able to bind to linear peptides of the library. We could identify three regions, all located within the C-terminal part of MUC5AC, which are recognized by this antibody (Fig. 4). However, these sequence fragments disclose no clearly definable linear consensus motif, suggesting that the segments may be part of a larger, non-linear epitope. The other four mAbs tested do not reveal any binding to linear peptide motifs of the protein backbone of MUC5AC (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Epitope mapping of anti-MUC5AC antibody 2H7. 15mer peptides spanning the MUC5AC protein backbone were synthesized and spotted onto cellulose-coated glass slides. Slides were incubated with monoclonal anti-MUC5AC antibody 2H7 and binding to individual peptides was detected by incubation with fluorescent secondary antibody and quantitation of fluorescence signal with the LI-COR Odyssey Classic system. (A) Regions of the MUC5AC protein backbone covered by the slides 1 – 6 and read-outs for one representative experiment. (B) Detailed analysis of the fluorescence signals from slide #6, containing the sequence regions of MUC5AC recognized by the 2H7 antibody (Nexperiments = 6). Peptide sequences of all spots displaying signals above the cut-off value (defined as the mean value of all spot signals on a slide plus three standard deviations; here: 0.22) are given.

Discussion

Aberrant mucin, be it in amount, composition or glycosylation, has been linked to a variety of mucosal inflammatory disorders, including airway inflammation and infection.1,2,5,18,27 Whether or not those links are strong enough to qualify mucin as a biomarker for mucosal inflammation remains to be investigated in more detail. In order to do so, simple and rapid methods for mucin enrichment and capturing must be available. MAbs specific for certain mucins are natural candidates for such a task. Yet, an ideal mAb must perform reliably in a patient-, sample (pretreatment)- and disease-independent manner. In this respect, mAbs whose paratope recognition varies among patients or becomes affected by different mucin compositions or glycosylation patterns are useless. To identify the most robust candidates among the multitude of mucin-reactive antibodies available, we tested all commercially available mAbs against MUC5AC, a major mucin in human airways, for their ability to bind MUC5AC from BALF samples of asthmatic and non-asthmatic individuals in immunoblot assays. Antibodies known to be directed against carbohydrate structures of MUC5AC were omitted from the study because the glycosylation pattern of mucins displays extremely high variability, and specific carbohydrate structures are not exclusive for mucins. These facts render such antibodies per se unsuitable for unbiased detection or capturing of MUC5AC in donor samples.

In our test system, we found that the remaining 15 different anti-MUC5AC antibodies displayed varying reactivities against the 19 BALF samples. Although all samples on each immunoblot had been normalized for identical MUC5AC content via a preceding “standardizing” MUC5AC quantification assay, every antibody analyzed showed considerable inter-patient signal variability over all samples, with coefficients of variation (CV) ranging from 57 to 138%. Five of the BALF samples of asthmatics (including BALF #11 which had been omitted from the second analysis round due to quantity constraints) gave a conspicuously higher immunoblot signal with most of the anti-MUC5AC antibodies. As the five samples in question had displayed a wide concentration range in their original MUC5AC content in the standardizing polyclonal ELISA, ranging from lowest MUC5AC content to well above mean, a general bias of the immunoblot due to a skewed MUC5AC measurement by the standardizing quantitation assay can be ruled out.

On the contrary, it stood to reason that the health status of the donors was causative for the above variation, especially since the five samples yielding the highest immunoblot signals include the only three patients with a documented recent asthma exacerbation (one of them with allergic asthma). This lead us to speculate that, in the asthma exacerbation, the MUC5AC structure may in some way be modified, which resulted in better detection by the majority of MUC5AC-specific antibodies in our immunoblot experiments. On the other hand, the donors of the other specimens with superior recognition by the antibodies have no recorded history of exacerbation, leaving the question whether similar changes were also present but undocumented in these patients or whether other factors than the health status were responsible for the different signal strengths observed with the MUC5AC-content-standardized samples. Investigation of more human (BALF) samples of comprehensively monitored patients with airway diseases will be necessary to clarify this point.

The goal of our study had been to identify antibodies for diagnostic and capturing purposes that could recognize MUC5AC with little or no inter-patient variability. Yet, we found that none of the antibodies tested was able to recognize the nitrocellulose-membrane-bound MUC5AC with the same performance independently of the patient material used. And even antibodies generated against similar antigenic compounds derived from the conserved protein backbone – such as synthetic peptides or recombinant mucin fragments, all lacking the glycosylation present on the MUC5AC glycoprotein – showed a clear disparity in binding to the native MUC5AC among the BALF samples. Possibly, binding of some of those antibodies to native mucin becomes severely hampered because the target epitope accessible on the immunization antigen was masked by carbohydrates present on the sampled protein, as may be the case, for example, with monoclonal anti-MUC5AC-peptide antibody 2A4, which is obviously barely able to react with the native MUC5AC in BALF samples.

On the other hand, mAbs generated against whole mucin preparations may preferentially target glycostructures or conformational epitopes. For example, the broadly used antibody 45M1 was reported to bind the C-terminal, cysteine-rich part of a recombinantly produced MUC5AC fragment only under non-reducing conditions.28 This suggests a disulfide bond-dependent, conformational epitope within the MUC5AC protein backbone as the target of the 45M1 antibody, which would lower its applicability for mucin preparations subjected to reducing agents.

If an antibody is to work patient- and preparation-independently, the best option might be that it both binds within an always accessible region of the native mucin and recognizes a linear protein backbone epitope. We therefore checked the five antibodies with superior binding of the native, glycosylated MUC5AC in BALF samples for their ability to recognize peptides derived from the mucin protein backbone. Only antibodies produced by the clone 2H7 directed against the barely glycosylated, C-terminal cysteine knot-like domain of MUC5AC are capable of accomplishing this task. However, 2H7 seems to recognize different linear segments within a larger conformational epitope. This can be explained by the fact that all three sequence regions detected by the antibody belong to a part of the protein that displays a rather complex spacial organization held together by intra- and intermolecular disulfide bounds and resulting in densely-packed and potentially also branched three-dimensional structures.2,29 Moreover, although a rather good antibody concerning patient-independent MUC5AC detection in the first round of antibody testing, 2H7 displays the most dramatic loss of activity within a short time frame, exhibiting a massive decline of target binding during experimental repetition, as indicated by the high standard deviation shown in Fig. 2. Additionally, this antibody showed high batch-to-batch variability demonstrated by the low activity of an additional antibody preparation analyzed, rendering it less useful for broad application in mucin diagnostics. Nevertheless, the sequence motifs detected by 2H7 may represent potential epitopes that can be used for the generation of a serviceable anti-MUC5AC antibody with sufficient stability.

Overall, none of the antibodies analyzed by us fulfilled our requirement to bind strongly and sample-independently to MUC5AC in BALF from various patients, but some candidates appeared to be better suited than others. At least in our experimental set-up, the mAbs Mg-31, O.N.457 and especially the broadly used antibody 45M1 were superior to the other anti-MUC5AC antibodies currently commercially available for MUC5AC detection. These three antibodies consistently give signals above the calculated mean value from all antibodies tested for each individual sample, and they exhibit a comparatively low signal variation within repetitive experiments.

Nevertheless, from this study we must conclude that all currently commercially available mAbs suffer severe shortcomings in the diagnostically relevant, quantitative detection of MUC5AC. To remedy the shortage of reliable mucin detection reagents, we are now in the process of locating antibody-accessible amino acid sequence motifs within the native glycoprotein. Once appropriate motifs have been identified, mAbs can be generated against the respective peptides, which will hopefully then allow an unambiguous identification, quantification and characterization of mucins from different sources. This comprehensive analysis of mucins would open opportunities for the exploration of mucus gel composition, mucus properties, mucin properties (e.g., glycosylation pattern of specific mucins) and their importance in chronic inflammatory airway diseases/disease exacerbation, hopefully resulting in earlier detection, as well as medical intervention.

Materials and methods

Sample acquisition and preparation

Pseudonymized BALF samples were provided by the BioMaterialBank (BMB) North in accordance with the ethical review committee of the University Lübeck, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany (reference number 15–069). Of the 20 samples obtained, 14 had an asthma background whereas six of the samples were from non-asthmatic individuals (Table 1).

Directly after lavage, the BALF was separated from cellular and insoluble components by centrifugation. Of each BALF solution, one representative aliquot was taken and used to measure the total protein content with the Pierce™ BCA protein assay kit (23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The remaining BALF was frozen and stored at −80 °C. Immediately prior to use, samples were thawed and supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (final concentration in sample: 1 x Sigma Fast™ Protease Inhibitor (S8820, Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µM Epoxomicin30 (BML-PI127–100, Enzo)).

MUC5AC quantification

Standardization of mucin content in all samples was performed with a commercially available MUC5AC quantification kit (E0756h, EIAab Science Co.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, BALF sample stocks were diluted 1:100 in the kit's sample diluent buffer. Of these diluted samples, 2–3fold serial dilutions were analyzed at least in duplicate with the MUC5AC quantification kit. Sample diluent buffer without MUC5AC served as negative control, a serial dilution of a standard with known amount of MUC5AC (included in the kit) was analyzed in duplicate in parallel to the BALF samples. OD450nm values of BALF sample dilutions within the linear range of the standard calibration curve were used for calculation of mucin concentrations.

Antibodies

A web-based search in the databases of multiple vendors revealed 32 apparently different mAbs against MUC5AC. Of those, eight were described as being directed against carbohydrate structures and thus were excluded from the study. A total of nine antibodies were no longer commercially available or turned out to be specific for other targets than human MUC5AC. Finally 15 different mouse mAbs against MUC5AC remained, and these 15 were included in this study (Table 2).

Two mouse mAbs (anti-OVA IgG (clone OVA-14, A6075, Sigma-Aldrich) and anti-2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) IgG (clone F6/C10, kindly provided by M. Fránek, Veterinary Research Institute, Brno, CZ)) were used as controls. Alexa Fluor® 680-fluorophore-labeled goat-anti-mouse IgG (A-21058, Life Technologies) served as secondary antibody.

Immunoblot experiments

Based on the results of the MUC5AC quantification, each BALF sample was diluted with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS) to a MUC5AC content of 1,500 ng per ml. Using a 96-well Minifold I Dot-Blot system (10447900, Schleicher & Schuell), 100 µl of each of the diluted BALF samples (corresponding to 150 ng MUC5AC) were applied onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Protran 0.2 NC, 10600001, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to generate a set of membranes with identical BALF sample patterns.

These membranes were washed three times for 5 minutes with D-PBS and two times with D-PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (93773, Sigma-Aldrich), and then blocked for 90 minutes with blocking buffer (D-PBS containing 5% (w/v) milk powder (Lactoland)). Afterwards, each blot was incubated overnight at 4°C with 300 ng/ml monoclonal anti-MUC5AC antibody in blocking buffer. The anti-2,4-D antibody, not capable of binding MUC5AC, used in the same concentration, as well as blocking buffer without antibody served as negative controls.

After washing six times for 5 minutes with D-PBS / 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, the membranes were incubated in secondary antibody-Alexa Fluor® 680 conjugate (1:5,000 dilution in blocking buffer with 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20) for 90 minutes at room temperature (RT) in the dark. Hereafter, the membranes were washed under exclusion of light four times with D-PBS / 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 and two times with D-PBS. Fluorescence signals were detected and quantified with an Odyssey Classic Imager (CE9120, LI-COR Biosciences) at a wavelength of 700 nm with an intensity below saturation of the fluorescence signals using the Odyssey 2.1. software for conversion into numerical values. Background was measured in a region of the membrane without BALF sample and subtracted from the values of the BALF samples. Data analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 5.02 software package (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Retrieval of spiked antigen in BALF samples

To exclude overloading of the nitrocellulose membranes with irrelevant BALF sample proteins, which might result in blocking of antibody epitopes and hence differences in antibody binding, BALF samples were spiked with defined amounts of OVA (152060, Galab) and the quality of OVA-signal retrieval was determined. In immunoblot pre-tests, 750 ng OVA per dot were shown to produce a signal in the linear range of the fluorescence intensity. 750 ng OVA alone or a mixture of 750 ng OVA and BALF equal to 150 ng MUC5AC were adjusted to 100 µl with D-PBS and dotted in duplicate onto nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblots were performed as described above, using monoclonal mouse anti-OVA IgG (1 µg in 3 ml blocking buffer) as primary antibody.

Generation of MUC5AC-peptide libraries

The binding of anti-MUC5AC antibodies to the MUC5AC protein backbone was analyzed by screening a library of peptides spanning the complete MUC5AC protein sequence (P98088, UniProtKB). The MUC5AC sequence (5030 amino acids) was converted into 15meric peptides with 13 amino acids overlap, thereby generating 2509 15mers. After removal of 281 duplicate sequences, a library of 2228 different peptide sequences remained.

These peptides were synthesized by CelluSpot Fmoc solid phase synthesis technique on amine-derivatized cellulose disks (32.121, Intavis Bioanalytical Instruments AG) using an automated multiple peptide synthesizer (MultiPep RS, Intavis Bioanalytical Instruments AG) as described previously.31 After completion of the peptide synthesis and side chain deprotection, cellulose disks were transferred into fresh 96-well plates (MegaBlock 96 well 2.2 ml, 821972.002, Sarstedt). 250 µl/well of cellulose lysis-solution containing 88.5% (v/v) of trifluoroacetic acid (P088.2, Roth), 4% (v/v) of trifluoromethane sulfonic acid (347817, Sigma Aldrich), 5% (v/v) of water and 2.5% (v/v) of triisobutylsilane (278785, Sigma-Aldrich) were added, and the cellulose was disintegrated by 10 min ultrasound treatment and additional 16 h shaking at RT. 750 µl of cold tert-butyl methyl ether (TBME, 34875, Sigma-Aldrich) were added, and mixtures were kept at −20 °C for 90 minutes during which time the peptides precipitated as peptide-modified cellulose fibers. Liquids were carefully removed after centrifugation, and residues were washed twice with TBME. The gel-like precipitates were dissolved in 500 µl/well of dimethyl sulfoxide (10 min ultrasound treatment and additional 16 h shaking at RT). These peptide/cellulose stock solutions were stored in the plates at −20 °C.

To prepare multiple identical peptide-libraries for antibody analysis, 40 µl of each peptide/cellulose stock solution were placed into individual wells of a 384-well microtiter plate (G384–12, Kisker Biotech), 40 µl of SSC buffer (150 mM NaCl, 15 mM Na-citrate, pH 7.0) were added to each well, the plates were sealed with an adhesive lid and treated on an ultrasound bath for 5 minutes. Peptide/cellulose dilutions prepared this way were transferred to cellulose-coated glass slides (54.112, Intavis) using an automatic spotter (AutoSpot ASP222, Abimed Analysentechnik). Each peptide (0.06 µl/sample) was spotted in duplicate onto the slides in two arrays with 384 positions (16×24 spots, 1.2×1.2 mm grid) each. Slides were air-dried and stored under dry conditions at −20 °C before use.

Analysis of anti-MUC5AC antibody binding to MUC5AC-derived peptides

The MUC5AC-peptide library on the slides was rehydrated by incubation with 5 ml of ethanol for 10 minutes, followed by washing three times for 10 minutes with 5 ml of TBST buffer (100 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM NaN3, 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20) and three times for 10 minutes with TBS (100 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM NaN3). Afterwards, the slides were blocked by incubation in 5 ml of blocking buffer (1% (w/v) Casein (Hammarsten grade, BDH via VWR International), 100 mM maleic acid, 150 mM NaCl, 100 µM NaN3, pH 7.5) for 5 h at RT. Slides were washed for 5 minutes with 3 ml of TBST. Afterwards, 3 ml of anti-MUC5AC antibody (625 ng/ml) in blocking buffer were added to the slides and incubated 14 h at 4 °C with rocking. Slides were washed six times with 3 ml of TBST and subsequently incubated with 3 ml of Alexa Fluor® 680-labeled goat-anti-mouse IgG (133 ng/ml) in blocking buffer for 2 h. Slides were washed four times for 10 minutes with 5 ml of TBST and air-dried. Fluorescence data acquisition and analysis was performed as described above. The cut-off value for a positive signal on a slide was defined as the mean value of all spot signals on this slide plus three standard deviations.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate the professional technical assistance that Geraldine Wiese contributed to this work.

Funding

This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the context of the German Center for Lung Research (DZL) (grant 82DZL00101) and via the BMB North membership in the PopGen 2.0 network (P2N) (grant 01EY1103).

References

- 1.Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2006; 86:245-78; PMID:16371599; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00010.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu Rev Physiol 2008; 70:459-86; PMID:17850213; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogan MP, Geraghty P, Greene CM, O'Neill SJ, Taggart CC, McElvaney NG. Antimicrobial proteins and polypeptides in pulmonary innate defence. Respir Res 2006; 7:29; PMID:16503962; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1465-9921-7-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose MC. Mucins: structure, function, and role in pulmonary diseases. Am J Physiol 1992; 263:L413-29; PMID:1415719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers DF. Airway mucus hypersecretion in asthma: an undervalued pathology? Curr Opin Pharmacol 2004; 4:241-50; PMID:15140415; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coph.2004.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knowles MR, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J Clin Invest 2002; 109:571-7; PMID:11877463; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI0215217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aikawa T, Shimura S, Sasaki H, Ebina M, Takishima T. Marked goblet cell hyperplasia with mucus accumulation in the airways of patients who died of severe acute asthma attack. Chest 1992; 101:916-21; PMID:1555462; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1378/chest.101.4.916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ordonez CL, Khashayar R, Wong HH, Ferrando R, Wu R, Hyde DM, Hotchkiss JA, Zhang Y, Novikov A, Dolganov G, et al.. Mild and moderate asthma is associated with airway goblet cell hyperplasia and abnormalities in mucin gene expression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163:517-23; PMID:11179133; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2004039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrell PM. The prevalence of cystic fibrosis in the European Union. J Cyst Fibros 2008; 7:450-3; PMID:18442953; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raherison C, Girodet PO. Epidemiology of COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2009; 18:213-21; PMID:20956146; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1183/09059180.00003609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu Y, Zhu J, Bandi V, Atmar RL, Hattotuwa K, Guntupalli KK, Jeffery PK. Biopsy neutrophilia, neutrophil chemokine and receptor gene expression in severe exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168:968-75; PMID:12857718; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1164/rccm.200208-794OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose MC, Nickola TJ, Voynow JA. Airway mucus obstruction: mucin glycoproteins, MUC gene regulation and goblet cell hyperplasia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001; 25:533-7; PMID:11713093; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.f218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P. Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 153:1530-5; PMID:8630597; http://dx.doi.org/22133317 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson DJ, Sykes A, Mallia P, Johnston SL. Asthma exacerbations: origin, effect, and prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128:1165-74; PMID:22133317; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavord ID, Jones PW, Burgel PR, Rabe KF. Exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11:21-30; PMID:26937187; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2147/COPD.S85978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamblin G, Degroote S, Perini JM, Delmotte P, Scharfman A, Davril M, Lo-Guidice JM, Houdret N, Dumur V, Klein A, et al.. Human airway mucin glycosylation: a combinatory of carbohydrate determinants which vary in cystic fibrosis. Glycoconj J 2001; 18:661-84; PMID:12386453; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1020867221861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davril M, Degroote S, Humbert P, Galabert C, Dumur V, Lafitte JJ, Lamblin G, Roussel P. The sialylation of bronchial mucins secreted by patients suffering from cystic fibrosis or from chronic bronchitis is related to the severity of airway infection. Glycobiology 1999; 9:311-21; PMID:10024669; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/glycob/9.3.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulz BL, Sloane AJ, Robinson LJ, Prasad SS, Lindner RA, Robinson M, Bye PT, Nielson DW, Harry JL, Packer NH, et al.. Glycosylation of sputum mucins is altered in cystic fibrosis patients. Glycobiology 2007; 17:698-712; PMID:17392389; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/glycob/cwm036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkeby S, Jensen NE, Mandel U, Poulsen SS. Asthma induction in mice leads to appearance of alpha2-3- and alpha2-6-linked sialic acid residues in respiratory goblet-like cells. Virchows Archiv 2008; 453:283-90; PMID:18682981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00428-008-0645-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caramori G, Di Gregorio C, Carlstedt I, Casolari P, Guzzinati I, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ, Ciaccia A, Cavallesco G, Chung KF, et al.. Mucin expression in peripheral airways of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Histopathology 2004; 45:477-84; PMID:15500651; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkham S, Sheehan JK, Knight D, Richardson PS, Thornton DJ. Heterogeneity of airways mucus: variations in the amounts and glycoforms of the major oligomeric mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B. Biochem J 2002; 361:537-46; PMID:11802783; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/bj3610537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies JR, Svitacheva N, Lannefors L, Kornfalt R, Carlstedt I. Identification of MUC5B, MUC5AC and small amounts of MUC2 mucins in cystic fibrosis airway secretions. Biochem J 1999; 344(Pt 2):321-30; PMID:10567212; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/bj3440321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groneberg DA, Eynott PR, Oates T, Lim S, Wu R, Carlstedt I, Nicholson AG, Chung KF. Expression of MUC5AC and MUC5B mucins in normal and cystic fibrosis lung. Respir Med 2002; 96:81-6; PMID:11860173; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/rmed.2001.1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groneberg DA, Eynott PR, Lim S, Oates T, Wu R, Carlstedt I, Roberts P, McCann B, Nicholson AG, Harrison BD, et al.. Expression of respiratory mucins in fatal status asthmaticus and mild asthma. Histopathology 2002; 40:367-73; PMID:11943022; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hovenberg HW, Davies JR, Herrmann A, Linden CJ, Carlstedt I. MUC5AC, but not MUC2, is a prominent mucin in respiratory secretions. Glycoconj J 1996; 13:839-47; PMID:8910011; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00702348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wickstrom C, Davies JR, Eriksen GV, Veerman EC, Carlstedt I. MUC5B is a major gel-forming, oligomeric mucin from human salivary gland, respiratory tract and endocervix: identification of glycoforms and C-terminal cleavage. Biochem J 1998; 334(Pt 3):685-93; PMID:9729478; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/bj3340685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linden SK, Sutton P, Karlsson NG, Korolik V, McGuckin MA. Mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. Mucosal Immunol 2008; 1:183-97; PMID:19079178; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/mi.2008.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lidell ME, Bara J, Hansson GC. Mapping of the 45M1 epitope to the C-terminal cysteine-rich part of the human MUC5AC mucin. FEBS J 2008; 275:481-9; PMID:18167142; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan JK, Howard M, Richardson PS, Longwill T, Thornton DJ. Physical characterization of a low-charge glycoform of the MUC5B mucin comprising the gel-phase of an asthmatic respiratory mucous plug. Biochem J 1999; 338(Pt 2):507-13; PMID:10024529; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/bj3380507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sixt SU, Beiderlinden M, Jennissen HP, Peters J. Extracellular proteasome in the human alveolar space: a new housekeeping enzyme? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007; 292:L1280-8; PMID:17220374; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajplung.00140.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Homann A, Rockendorf N, Kromminga A, Frey A, Jappe U. B cell epitopes on infliximab identified by oligopeptide microarray with unprocessed patient sera. J Transl Med 2015; 13:339; PMID:26511203; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/s12967-015-0706-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]