Abstract

We observed that the transient induction of mtDNA double strand breaks (DSBs) in cultured cells led to activation of cell cycle arrest proteins (p21/p53 pathway) and decreased cell growth, mediated through reactive oxygen species (ROS). To investigate this process in vivo we developed a mouse model where we could transiently induce mtDNA DSBs ubiquitously. This transient mtDNA damage in mice caused an accelerated aging phenotype, preferentially affecting proliferating tissues. One of the earliest phenotypes was accelerated thymus shrinkage by apoptosis and differentiation into adipose tissue, mimicking age-related thymic involution. This phenotype was accompanied by increased ROS and activation of cell cycle arrest proteins. Treatment with antioxidants improved the phenotype but the knocking out of p21 or p53 did not. Our results demonstrate that transient mtDNA DSBs can accelerate aging of certain tissues by increasing ROS. Surprisingly, this mtDNA DSB-associated senescence phenotype does not require p21/p53, even if this pathway is activated in the process.

Aging is a highly complex, yet poorly understood, orchestration of cell signaling events resulting in metabolic and regenerative declines that lead to cell death, cell cycle arrest, senescence, or terminal differentiation.1 Nuclear DNA damage is considered a primary causal factor in aging.2 Premature aging phenotypes have been widely observed in mouse models lacking nDNA repair enzymes.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 p53 is one of the most extensively studied proteins in modern biology, playing a central role in responding to diverse types of nDNA damage by coordinating cell fate, often in the context of either promoting aging or suppressing cancerous processes.8 Genes that are transcriptionally activated by p53 have been implicated in multiple models of aging.9, 10, 11

Mitochondria are tied to the aging process, through their involvement in apoptosis, energy production or the generation of signaling molecules such as reactive oxygen species (ROS).12, 13, 14, 15 Mitochondria have multiple copies of their own genome, which encodes subunits for the different complexes of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system.16 It is suggested that decline in mitochondrial function caused by mtDNA damage contributes to cellular aging.17, 18 However, often times in aged tissues, mtDNA mutational levels do not exceed the threshold sufficient to cause mitochondrial dysfunction.19, 20 Moreover, low levels of ROS have been shown to signal extension of life span in different organisms.21, 22 Presently, it is unclear how and to what extent mtDNA damage contributes to cellular senescence or aging phenotypes. In the present study, we used mitochondria-targeted restriction endonucleases to induce mtDNA damage in different systems. After observing decreased cell growth in vitro and a progeroid-like phenotype in vivo, we analyzed potential molecular mediators of these phenotypes.

Results

MtDNA double-stranded breaks cause defects in cellular growth and is associated with an upregulation of nuclear cell cycle checkpoint signaling

To determine how mtDNA damage contributes to cell growth, we utilized a hepatocyte-derived cell line stably expressing a mifepristone-inducible mitochondrial-targeted endonuclease mito-ScaI23 (Figure 3b). Mito-ScaI co-localized with the mitochondrial marker MitoTracker Red red (Figure 1a) and was detected shortly after the addition of mifepristone, with a peak at 24–48 h of induction (Figure 1b). Its expression after 30-min induction led to a rapid reduction of mtDNA levels (Figure 1d) and to a decrease in cell proliferation in the following days (Figure 1c).

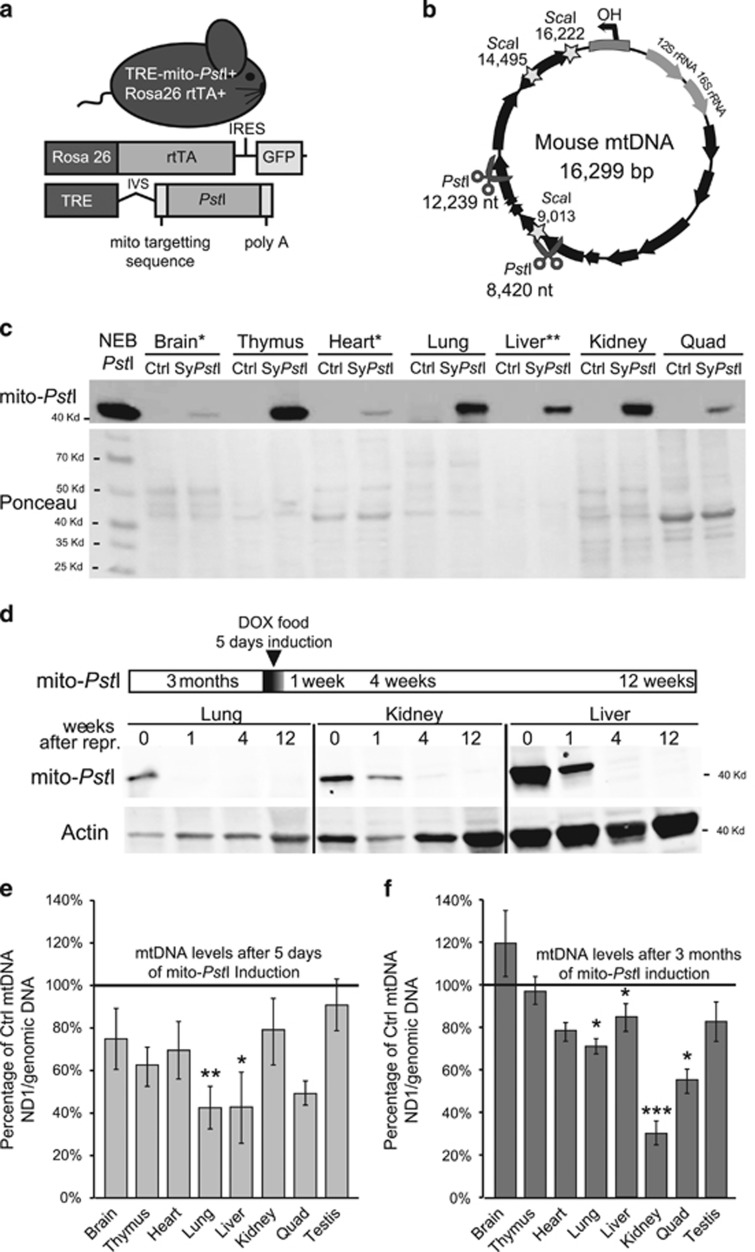

Figure 3.

Characterization of transient and systemic expression of mito-PstI in transgenic mice. (a) Schematic representation of the SystemicIndmito-PstI mouse and the transgenic constructs it harbors. (b) mtDNA map showing the targeted sites of PstI (scissors) and ScaI (stars). Black arrows denote protein-coding genes. (c) Western blotting using anti-PstI antibody to detect mito-PstI expression in SystemicIndmito-PstI (SyPstI) mice tissues at 3 months of age after a 5-day induction (brain, thymus, heart, lung, liver, kidney, quadriceps). NEB (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) PstI restriction enzyme was used as a positive control. (d) Cartoon of mito-PstI induction paradigm (5-days induction at 3 months of age). The lower part of the panel shows a western blot for PstI in SystemicIndmito-PstI animal tissues immediately, 1 week, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks after induction in lung, kidney and liver, tissues with the highest mito-PstI expression. (e) Quantitative-PCR quantification of mtDNA/nuclear DNA ratios of tissues from the SystemicIndmito-PstI mice, and age-matched controls immediately after the 5-days induction (left panel) or after 3 months, when animals were 6 months old (right panel) (n=4-5/group). All mice in these analyses were males. Values are presented as mean±S.E.M. (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001)

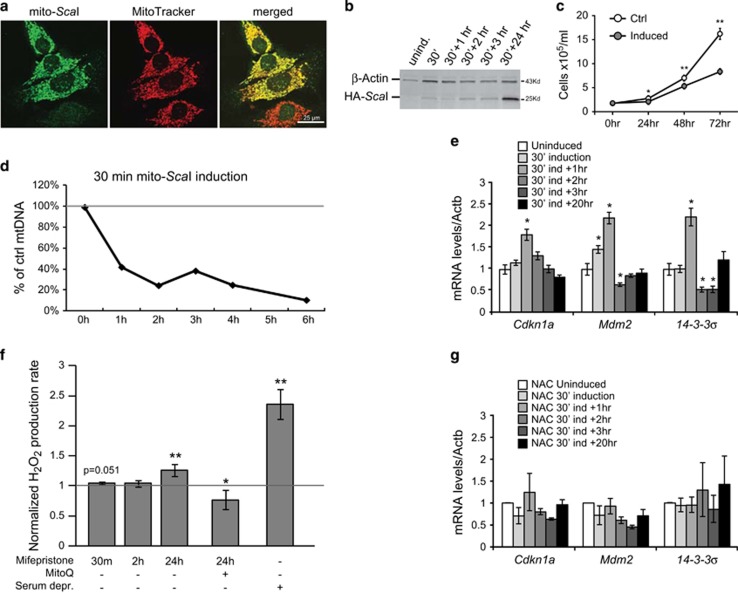

Figure 1.

MtDNA DSBs lead to a ROS-dependent activation of p53 pathway in cultured cells. (a) Immunocytochemistry of mito-ScaI cells using antibody against HA (green) and MitoTracker Red (red) after 10 nM mifepristone induction for 2 h. Images were captured at × 20. (b) Representative western blotting showing mito-ScaI (with HA tag) is induced by administrating 10 nM mifepristone for different lengths of time. (c) Quantification of Southern blot for mtDNA and nuclear rDNA levels in mito-ScaI cells at different time points after 10 nM mifepristone induction for 30 min showing mito-ScaI depletes mtDNA. (d) Growth curve over 3 days after 30 min mifepristone induction of mito-ScaI cells and non-induced controls (n=3). (e, g) Real-time RT-PCR of 14-3-3σ, Mdm2, and p21 (Cdkn1a) in mito-ScaI cells after 30 min of mifepristone induction and 1–3, and 20 h recovery without (e) or with (g) 24 h pre-treatment with NAC (n=3). (f) Rate of hydrogen peroxide production detected by Amplex Red assay in mito-ScaI cells. Serum deprivation for 24 h was used as a positive control, and MitoQ was used as a negative control. Values are presented as mean±STDEV. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

After mtDNA double strand breaks (DSBs) we observed an upregulation of the cell cycle arrest protein, p21 (Cdkn1a) transcript (Figure 1e). We also observed an increase in transcript levels of two other genes activated by p53: Mdm2, negative regulator of p53, and 14-3-3σ, a cell cycle checkpoint controller (Figure 1e). These transcriptional responses decreased 2 h after the mito-ScaI stimulus (Figure 1e). These data suggested that acute mtDNA damage triggered the activation of nuclear signaling pathways that control the progression of cell cycle, possibly prior to mitochondrial dysfunction: COX I protein level (Supplementary Figures S1A–B), and cytochrome c oxidase enzymatic activity (ref. 23) decreased 24 h after the induction. P38 and JNK, which also participate in a signaling cascade controlling cellular responses to stress, were not altered24, 25 (Supplementary Figures S1A, C).

Antioxidants abolish the transcriptional response present after mtDNA damage

To determine the mechanism regarding how the mtDNA damage triggered a p53/p21 response, we investigated whether ROS was involved in the signaling in the mito-ScaI inducible cell line. We measured hydrogen peroxide production after mtDNA damage, using serum deprivation as a positive control,26 and we detected a small increase in H2O2 after 30 min of mito-ScaI induction, but it fell short of significance (p=0.051). We did observe a larger increase in H2O2 after 24 h whereas in the presence of MitoQ, a mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant, there was a significant decline in ROS production after mtDNA damage (Figure 1f). We also tested whether antioxidant treatment could abolish the mtDNA damage signaling. Indeed, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) treatment neutralized changes in cell cycle arrest gene expression in cells with mito-ScaI induction (Figures 1e and g). These data suggested that increased ROS mediates the signal between mtDNA DSBs, p53 signaling and cell growth changes.

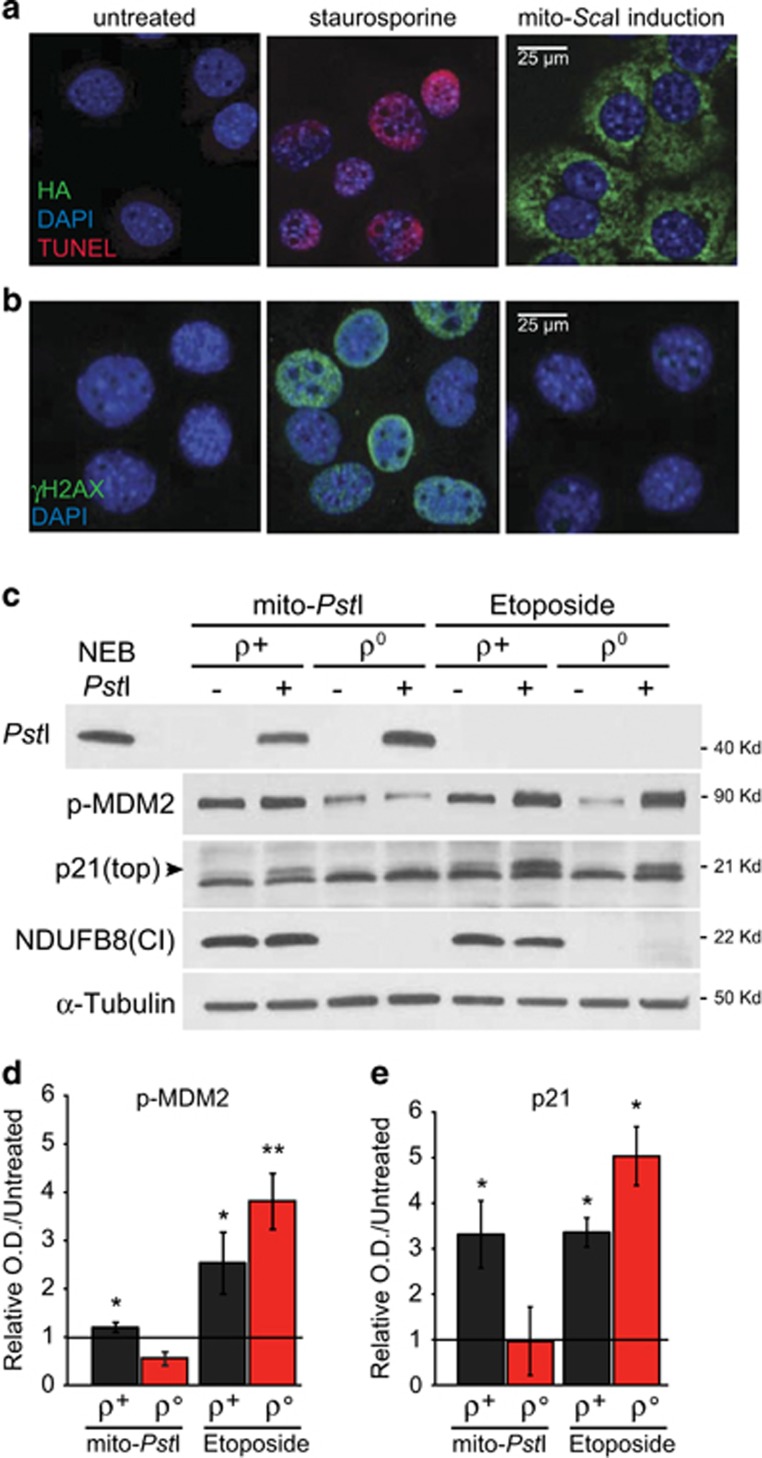

The upregulation in nuclear transcriptional response is not due to nuclear DNA damage

To ensure that the cell growth inhibitory effects observed were not due to leakage of mito-ScaI into the nucleus, we performed TUNEL and γ-H2AX assays. Mito-ScaI cells were either induced with mifepristone or treated with staurosporine, an inducer of nDNA fragmentation. We observed TUNEL (Figure 2a) and γ-H2AX (Figure 2b) positive nuclei in cells treated with staurosporine but not in cells expressing mito-ScaI for 24 h.

Figure 2.

MtDNA DSBs trigger a p53-dependent response without nuclear DNA damage. (a) Representative TUNEL staining detecting DNA fragmentation (red) after inducing apoptosis with staurosporine or mito-ScaI expression for 24 h. Cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue) to show the nucleus and anti-HA (green) to show ScaI expression (n=3). (b) Representative γH2AX staining (green) after staurosporine or mito-ScaI expression for 24 h. Cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue) (n=3). (c) Western blotting of phosphorylated MDM2, p21 in gorilla ρ+ and ρ° cells either treated with 10 μM Etoposide (ETP, DMSO vehicle) or transfected with mito-PstI (mito-GFP as ctrl) for 24 h. (d-e) Quantification of phospho-MDM2 (d) and p21 (e) protein levels after ETP treatment or mito-PstI transfection normalized to β-actin, in relation to the not-stressed cells (n=3). The marked line indicates the control level in untreated cells. Values are presented as mean±STDEV. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

To further ensure that our restriction endonucleases were specifically targeted to mitochondria, we added the same COX8 mitochondrial-targeting sequence to a different endonuclease (PstI) and expressed it in ρ° and ρ+ cells. Mito-PstI promoted significant increase in phosphorylated MDM2 and p21 protein levels in ρ+ cells but not in ρ° cells (Figures 2c and e). Etoposide (nDNA damaging agent) was used as positive control and induced an increase in phosphorylated MDM2 and p21 levels in both ρ° and ρ+ cells (Figure 2c–e).

These results support that the decline in proliferation and the upregulation in nuclear transcriptional response controlling cell cycle were due to damage to mtDNA and not to an unspecific cleavage of nDNA.

Systemic and inducible expression of mito-PstI in a transgenic mouse model

To investigate the response to mtDNA DSBs in vivo, we developed a mouse model with inducible mito-PstI expression. This mouse model ubiquitously expresses two transgenes: a tetracycline-inducible, mitochondrial-targeted PstI endonuclease (mito-PstI) and a reverse tetracycline transactivator protein (rtTA) under the control of the ubiquitous Rosa26 promoter27 (Figure 3a). We will refer to this double-transgenic as ‘SystemicIndmito-PstI' mouse. To avoid developmental defects that may occur with early mito-PstI exposure, mito-PstI expression was induced at 3 months of age for only 5 days (Figure 3d). DOX food was given to both SystemicIndmito-PstI and control mice.

Mito-PstI expression was relatively low in brain, heart and skeletal muscle, whereas levels were higher in liver, thymus, lung and kidney (Figure 3c). Mito-PstI expression was transient and detectable by western blot only during the first week after the 5-day induction period even in tissues with the highest expression (Figure 3d).

To test whether mito-PstI was functional and whether it cleaved mtDNA in vivo, we measured mtDNA levels. MtDNA was reduced in the lung and liver, immediately following a 5-day induction (Figure 3e), but less so after 3 months (Figure 3f). Kidney and muscle showed a mild, not significant mtDNA depletion after 5 days of induction, but curiously, there was depletion after 3 months. MtDNA depletion was not observed in the brain, thymus, heart and testis. Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that mtDNA DSBs lead mostly to mtDNA depletion, but also to the formation of mtDNA deletions in post mitotic tissues, albeit at low levels.28 Although we were able to detect the presence of two types of mtDNA deletions in heart and brain (Supplementary Figure S2A), the levels were low (<1%) and therefore unlikely to have functional consequences.

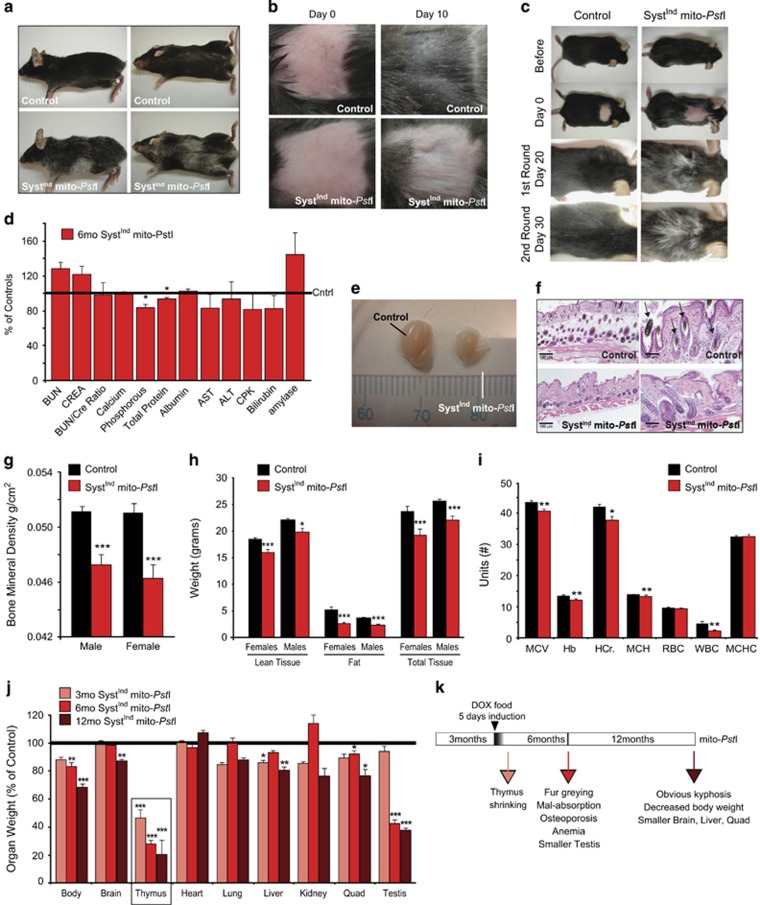

SystemicIndmito-PstI mice develop signs resembling premature aging

SystemicIndmito-PstI mice appeared normal in the first 10–12 weeks following 5-day induction; however, 6 months after DOX exposure, the animals began to present phenotypes resembling aged mice (Figure 4k). One of the first noticeable phenotypes was kyphosis and fur graying (Figure 4a). The fur graying, which has been linked to an inability to maintain melanocyte stem cell pools,5 spread from ventral toward dorsal side. To test whether there was a defect in hair follicle regenerative cell pools in our model, we induced the anagen hair phase by depilating the mice. We observed that SystemicIndmito-PstI mice had markedly delayed fur re-growth (Figure 4b). After a second round of depilation, we observed additional fur loss and graying (Figure 4c). Histologically, hair follicles were defective and less in number (Figure 4f).

Figure 4.

SystemicIndmito-PstI mice show age-related phenotypes in mitotic tissues. (a) Representative images of 6-month-old mice show the ventral graying of the fur of SystemicIndmito-PstI mice compared to age-matched controls. (b) Representative images of the 2 × 2 cm2 patch depilated to induce anagen hair follicle cycle in controls and SystemicIndmito-PstI mice (n=5/group). (c) Representative images of the graying of the fur in SystemicIndmito-PstI mice that sustained two rounds of depilation. (d) Basic serum chemistry panel on 6-month-old control and SystemicIndmito-PstI female mice (n=11 controls, n=9 SystemicIndmito-PstI). Values are presented as mean±S.E.M. (*P<0.05). (e) Representative picture of the difference in size of testes from a control and a SystemicIndmito-PstI male at 6 months of age. (f) Hematoxylin and eosin stained samples of skin from the depilated region after 10 days. SystemicIndmito-PstI mice have abnormal dermal and epidermal layers with decreased fat content (white, unstained layer) and cycling hair follicles (arrows) as compared to controls (n=3/group). (g) Bone mineral density of 6-month-old control and SystemicIndmito-PstI mice. (h) DEXA scan quantification of lean tissue, fat, and the total amount of tissue in the whole body of 6-month-old controls and SystemicIndmito-PstI males and females. (n=7–11/group). (i) Blood panel on 6-month-old control and SystemicIndmito-PstI females (n=16 controls, n=11 SystemicIndmito-PstI). # Units (MCV=fL, Hemoglobin=g/dL, Hematocrit (HCr.)=%, MCH=pg, RBC= × 106/μl, WBC= × 103/μl, MCHC= %). (j) Organ weight as percentage of the controls for SystemicIndmito-PstI mice induced and killed immediately (3 months old, light red columns), after 3 months (6 months old, red columns) or after 6 months (12 months old, brown columns) (n=5–8/group; males). Values are presented as mean±S.E.M. (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). (k) Graphical representation for the induction schedule of SystemicIndmito-PstI and color-code for the time points analyzed with relative phenotypes observed

Because hair follicles are highly mitotic, we also analyzed other mitotic tissues of the SystemicIndmito-PstI mice to determine their vulnerability. Blood chemistry panels showed decreases in phosphorus and total proteins in the serum, an effect commonly associated with mal-absorption related to abnormalities of the small intestine (Figure 4d). In addition, we also found significant shrinkage of the testes at 6 months of age (Figures 4e and j). Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans revealed decreases in bone mineral density, indicative of osteoporosis (Figure 4g), accompanied by significant decreases in total fat, percentage of body fat and lean tissue mass (Figure 4h). A decrease in fat was also evident in the dermal layers of the skin (Figure 4f). Moreover, SystemicIndmito-PstI mice also had significant declines in white blood cell populations and signs of anemia (Figure 4i).

Brain, thymus, liver, quadriceps and testis weight, as well as total body weight, were significantly lower in 1-year-old SystemicIndmito-PstI mice (Figure 4j). Mito-PstI induction did not result in premature death in any of the females monitored (up to 2 years of age); however, males often died before 18 months of age.

Accelerated thymus involution in response to mito-PstI

Immediately after 5-day induction, SystemicIndmito-PstI mice had an acute and severe decrease in both thymic weight and thymocyte count (Figures 5a and b). Small populations of lymphoid progenitor cells in the thymus differentiate and give rise to mature T cells29 (Figure 5g). We analyzed the total thymocyte population for maturity stages after the 5-day induction. Double positive cells (CD4+/CD8+) (DP) were significantly decreased, whereas mature T cells (CD4+/CD8- or CD4-/CD8+) were significantly increased in the SystemicIndmito-PstI mice (Figures 5c and d). These findings suggest that mtDNA damage impairs thymocyte development.

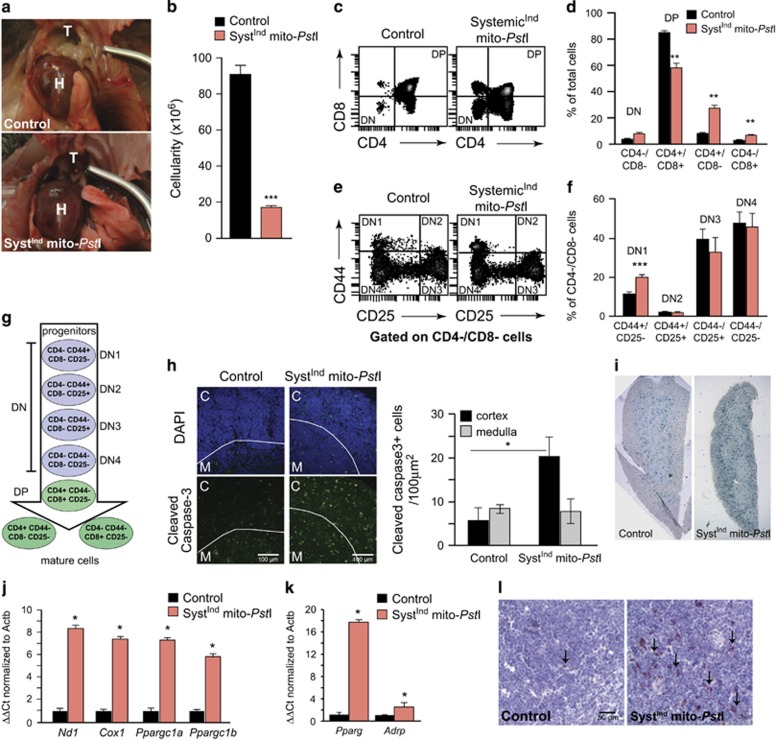

Figure 5.

mtDNA damage in SystemicIndmito-PstI mice causes a block in thymic progenitor progression leading to loss of thymocytes. (a) Picture of 12-month-old SystemicIndmito-PstI mice compared to controls showing the complete absence of the thymus in transgenic animals. (b) Thymocyte counts from control and induced SystemicIndmito-PstI mice at 3 months of age (n=3-4/group). (c-d) FACS analysis and quantification of CD4+ and CD8+ surface antigens on thymocyte population from control and SystemicIndmito-PstI mice (DN: double negative, DP: double positive). (e-f) FACS analysis and quantification of CD44+ and CD25+ surface antigens on the double negative thymocyte population from control and SystemicIndmito-PstI mice at 3 months of age. (g) Schematic drawing of thymocyte stages of maturation with relative surface antigens expression. (h) Representative immunohistochemical images of cleaved caspase-3 staining (green) with DAPI nuclear counter stain (blue) in the thymus. M, medulla; C, cortex and quantification of caspase-3 positive cells in cortex and medulla of control and SystemicIndmito-PstI mice. (i) β− galactosidase activity in frozen thymic sections of control and SystemicIndmito-PstI mice (n=2/group). (j-l) Accelerated thymus senescence and adipose tissue differentiation in response to mtDNA damage in 3-month-old animals: (j) Fold expression of mtDNA-encoded transcripts (ND1 and COX1) and PGC-1α/β mRNA levels in SystemicIndmito-PstI thymus compared to control mice (n=5/group). (k) Fold expression of mRNA transcripts PPARγ and ADRP in SystemicIndmito-PstI thymus compared to control mice (n=5/group). (l) Oil Red O staining (red) with a hematoxylin counter stain (blue) of control and induced SystemicIndmito-PstI thymus sections at × 20 magnification (n=3/group). Values are presented as mean±S.E.M. (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001)

Further examination of the DN thymocyte population revealed increase in CD44+/CD25− (DN1) cell population (Figures 5e and f); this marks the first stage in thymocyte development (Figure 5g). The accumulation of DN1 cells indicates delayed or impaired transition to DN2 (CD44+/CD25+) that may explain the decreased numbers of DP thymocytes in these mice. We also observed that, at 3 months, thymus underwent apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3 reactivity) (Figure 5h) and senescence (marked by non-acidic β-galactosidase activity) (Figure 5i), mostly in the thymic cortex, a region enriched for progenitor and developing cells (Figures 5h–i).

The thymus of SystemicIndmito-PstI mice could degenerate due to an OXPHOS defect, related to mtDNA depletion. We detected a trend, even if not significant, towards mtDNA depletion (Figure 3e) and COXI protein level decreased after 5 days of induction (Supplementary Figures S1D, E). Paradoxically, we observed a significant, 7-8-fold increase in mitochondrial encoded COXI and ND1 mRNA levels in these mice (Figure 5j). Transcript levels of PGC-1α and PGC-1β, the master regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis, were also increased by 6–8 fold in this group (Figures 5j and k). Normal age-related thymic involution is associated with differentiation of thymocytes into adipose tissue, with adipocytes having increased mitochondrial markers.30 Therefore, we analyzed the expression of PPARγ, a factor involved in pre-adipose tissue differentiation,31, 32, 33 and found a ~17-fold increase in its mRNA levels (Figure 5k). Accordingly, ADRP expression level (another marker of early adipocyte differentiation) was also elevated (Figure 5k). To determine whether these transcriptional regulations had a functional consequence in thymic cellular composition, we performed Oil Red O staining to detect triglycerides and lipids. We observed a dramatic increase in lipid deposits in SystemicIndmito-PstI mice thymus (Figure 5l). In conclusion, our data suggest that an accelerated aging-like response in the thymus was triggered by acute mtDNA damage, and resulted in a cascade of events that mimic natural mammalian thymic involution.30

MtDNA damage is associated with an upregulation of cell cycle arrest proteins in vivo

Mitotic tissues, such as hair follicles, thymus and reproductive organs, were preferentially affected (Figures 4 and 5) and these organs are known to have high p53 levels.34 Because mice harboring constitutively activated mutant p53 have progeroid phenotypes35, 36 and we detected increased expression of p53 target genes in cultured cells after mtDNA DSBs (Figures 1 and 2), we tested whether p53 downstream markers were activated in the thymus of our SystemicIndmito-PstI mice. Cdkn1a, Mdm2 and 14-3-3σ transcripts and p-MDM2 protein levels did not change after 5 days of mito-PstI induction (Figure 6a). However, since changes in the levels of these transcripts are commonly an early response to damage, we analyzed their levels at an earlier time point (2 days after induction). Cdkn1a and 14-3-3σ transcripts levels were indeed upregulated (Figure 6c) and so was p-MDM2 (Figure 6d), indicating stabilization of p53.37 These data indicated that cell cycle arrest signaling occurred before the accelerated thymic aging phenotype. We also analyzed p-p38/p38 and p-JNK1/JNK1 in thymus of 2 and 5 days induced mice but, similarly to the in vitro model, we did not detect activation of these pathways (Supplementary Figures S1D, E).

Figure 6.

p53 transcriptional response is triggered by mtDNA damage in SystemicIndmito-PstI thymus tissue but is not responsible for the aging phenotype. (a) Real-time RT-PCR of p21 (Cdkn1a), 14-3-3σ, Mdm2, and Bax transcripts in the thymus of 2-day and 5-day induced control or SystemicIndmito-PstI mice (n=4–5/group). (b) Thymus weight and cellularity after 2 days of induction of SystemicIndmito-PstI mice. (d) Quantification of phosphorylated MDM2 protein levels in the thymus of 3-month-old SystemicIndmito-PstI mice induced for 2 days over controls (n=4/group). Values are presented as mean±S.E.M. (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). (e) Weight of thymus in control and SystemicIndmito-PstI mice pre-treated with NAC (dashed columns): NAC alleviated the shrinkage of thymus in SystemicIndmito-PstI mice. (f) Thymus weight in 3-month-old control, p21KO, p53KO, SystemicIndmito-PstI, p21KO/SystemicIndmito-PstI, p53KO/SystemicIndmito-PstI: knocking out of p21 and p53 did not reverse or alleviate the shrinkage of the thymus in SystemicIndmito-PstI mice

Using cultured cells, we showed that increased ROS mediated mtDNA DSB signaling pathways. Moreover, a previous report showed that NAC treatment ameliorated some of the aging phenotypes present in the Mutator mouse.38 To analyze if oxidative stress was involved in the aging-like phenotype in the thymus of SystemicIndmito-PstI mice, we treated 3-month-old animals with NAC. This prevented the thymic involution caused by mtDNA DSBs (Figure 6e), suggesting the involvement of oxidative stress in this aging-like phenotype.

p53/p21 pathway are not required for the mtDNA-induced progeroid phenotype

Our data showed that mtDNA DSBs caused defects in cellular growth, which were associated with an upregulation of nuclear cell cycle checkpoint signaling in vitro (Figures 1e and 2c and e). We also showed how mtDNA DSBs cause a premature aging-like phenotype in vivo, particularly evident in proliferating cells, also associated with an activation of p53/p21 pathway in thymic homogenates. In order to determine whether the p53/p21 pathway is required for the progeroid phenotype observed in vivo, we knocked out p21 or p53 in the SystemicIndmito-PstI mice by breeding the latter with p21KO39 and p53KO40 animals.

We induced p21KO/SystemicIndmito-PstI and p53KO/SystemicIndmito-PstI mice and analyzed the involution of the thymus in 3-month-old animals. We still detected similar aging-like phenotypes (Figure 6f), indicating that p21 and p53 are not required for the acute phenotype caused by mtDNA damage.

To further assess whether p21 and p53 were required for the other progeroid-like phenotypes induced by mtDNA DSBs, we analyzed 6-month-old p21KO/ and p53KO/SystemicIndmito-PstI. These mouse lines develop multiple tumors at this age, particularly the p53KO animals.40 In our analysis we included only mice (~40% of the total) that did not show evident signs of tumor formations. The graying of the fur observed in 6-month-old mito-PstI was still present in the absence of p21 or p53 (Supplementary Figure S3A) as well as the delay in fur re-growth after depilation (Supplementary Figure S3B).

We measured the organ weight in 6-month-old animals and, apart from lung and liver that were smaller respectively in p21KO/SystemicIndmito-PstI and p53KO/SystemicIndmito-PstI, we did not find any difference between the three groups of mice. The absence of p21 or of p53 did not alter these phenotypes (Supplementary Figure S3C), nor blood chemistry panels (Supplementary Figure S3D). We also analyzed the gross anatomy of intestine, testis and bone marrow by staining with H&E and detected no significant differences (Supplementary Figure S3E).

Discussion

Different studies show an accumulation of mtDNA mutations in aged tissues but, often, mtDNA mutational levels do not exceed the threshold sufficient to cause mitochondrial dysfunction.19, 20 Presently, it is unclear how and to what extent mtDNA damage contributes to cellular senescence or aging phenotypes. Although large rearrangements of mtDNA are known to accumulate in aging tissues of mammals, the causative role of these mtDNA species in aging is still speculative.

In this study, we showed that a short induction of DSBs in mtDNA resulted in a premature aging-like phenotype in proliferating mouse tissues. MtDNA DSBs caused a p53 transcriptional response in vitro and, in some tissues, also in vivo but neither p53 nor p21 was required for the aging phenotype observed in vivo. We also showed that ROS play a role in the development of the phenotype and in the signaling process, as antioxidants blunted these responses.

MtDNA DSB damage response

Previous studies have suggested that there are shared nuclear proteins and responses after mtDNA damage: (1) Nuclear Ku proteins, involved in nuclear DSB repair, are associated with mtDNA DSB repair;41 (2) DNA Ligase III also has an alternatively spliced form that locates to the mitochondria with its function independent of its role in the base excision repair;42, 43 (3) Besides its role in nuclear DSB repair, ATM kinase is involved in maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis;44, 45 (4) Rad51 has been found to play critical roles in the maintenance of mitochondrial genome.46 The fact that several studies showed that DNA repair proteins are shared between the nuclear and mitochondrial compartments, suggests that damage to mtDNA, independent of nDNA damage, regulates classical signaling pathways as shown in this study. However, at this point, it is not clear if any of these nuclear DNA damage response sensors play a role in the response to mtDNA DSBs.

MtDNA DSBs affect cells with proliferative potential

MtDNA DSBs can signal the nucleus either by a sensor mechanism detecting the damage, or indirectly, by a defect in OXPHOS function. In our experience, mtDSBs lead to an mtDNA depletion as linearized molecules are rapidly degraded.47 However, other types of mtDNA mutations can also result from DSBs. Mito-PstI expression was low in the brain and heart (Figure 3c), but when we measured mtDNA deletions in different tissues of 6-month-old animals, these tissues showed the highest levels of mtDNA deletions (Supplementary Figure S2B). We suspect that these deleted molecules were expanded due to the post-mitotic nature of brain and heart, since we detected no accumulation of mtDNA deletions in liver, the tissue with the highest mito-PstI expression (Supplementary Figure S2B). However, at 6 months, we observed no biochemical (assessed by measuring OXPHOS proteins levels in brain homogenates) or behavioral deficits (assessed by Morris water maze test) in the CNS (data not shown). We did observe a significant muscle wasting phenotype in SystemicIndmito-PstI mice, which was attributed to the sensitivity and preferential loss of satellite cells (the stem cells in skeletal muscle).48 These observations suggested that the generation of mtDNA deletions themselves, which accumulate at low levels, did not drive the perceived premature aging-like phenotypes. Moreover, the majority of the aging-like phenotypes described affected tissues with proliferative potential (skin, bone marrow, testis) and progenitor cells. Similarly, we could not detect a marked depletion of mtDNA in the affected tissues coinciding with the appearance of the aging-like phenotypes, suggesting that these phenotypes are due to an earlier signaling event, not necessarily mtDNA depletion (or deletion) induced energy defects.

These results support the previous suggestion that progenitor cell pools are highly vulnerable to mitochondrial-related ROS alterations.38, 48 Ahlqvist et al. showed that the progeroid phenotype of the mutator mouse was blunted by NAC, which protected stem and progenitor cells. We also found that muscle satellite cells were decreased in the SystemicIndmito-PstI mouse.48 Therefore, there is a growing body of evidence that mtDNA damage has a severe phenotypic effect in cells with high proliferative potential.

ROS effect: direct or indirect?

The ROS-associated p53 signaling observed appeared soon after mtDNA DSBs. We could not determine the source of this early ROS, although OXPHOS impairment would be the obvious candidate. It is difficult to explain the ROS generation without an OXPHOS dysfunction, but one could speculate that there are unidentified factors that recognize mtDNA DSBs and modify OXPHOS enzymes, leading to fast ROS production after mtDNA DSBs. Therefore, although we have found that ROS were the mediator of p53 signaling after mtDNA damage (in vitro), and that they were involved in the thymus shrinkage in SystemicIndmito-PstI, the exact mechanism by which ROS is generated or signals is still unclear. Previous reports showed that ROS have the ability to activate p53 and inhibit ATM (upstream repressor of p53), without the presence of nuclear DNA damage.49 Even though we did not detect nuclear DNA damage in our in vitro system, it is still possible that the ROS from mtDNA insults could diffuse to the nucleus and damage nuclear DNA in the SystemicIndmito-PstI mice.50, 51 In any case, the phenotypic alterations do not appear to depend on the p53 pathway (even if it is activated in the process), and may directly induce death of progenitor cells by a different mechanism. ROS signaling appears to be both activating the p53 pathway and another undefined pathway that leads to the p53-independent aging-like phenotypes observed.52

Other than ROS, different pathways are likely to be involved in the aging phenotype caused by mtDNA damage. One possibility is the activation of mtUPR system. Even though we did not explore this pathway in detail, we did not detect significant changes in the levels of mitochondrial chaperones (Hsp60, Hsp70) or of UPR markers (CHOP, BiP) in our in vitro mito-ScaI system and in thymus of 2- and 5-day induced SystemicIndmito-PstI mice (Supplementary Figures S1F-H). Previously,48 we analyzed skeletal muscle after mito-PstI induction, and we detected a decrease in chaperones Hsp60, Hsp70, mtHsp70 and ER stress markers BiP/Grp78, CHOP, in 6-month-old systemic mito-PstI mice muscles respect to controls. Although we cannot exclude that other components of this pathway may be activated, in different tissues and at different time points, we do not have evidence supporting this model.

Conclusions

MtDNA DSBs triggered differentiation, apoptosis, senescence and arrest of proliferative tissues: some stem and progenitor cells were markedly affected by this mechanism, possibly explaining the premature aging-like phenotypes observed in the SystemicIndmito-PstI mouse. The aging phenotype, particularly in the thymus, was reverted by antioxidants, but not by knocking out p21 or p53, suggesting the involvement of other pathways associated with ROS signaling. This study demonstrates that mtDNA DSBs can have a major impact in tissue aging in a mechanism involving ROS, which can utilize, but does not require, p53 nor p21.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The work with mouse models was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). As required by the IACUC, all efforts were done to minimize suffering of the animals.

Animals

The generation of mito-PstI transgenic mice was previously described.28 Mito-PstI male and female animals were pure C57BL/6J mito-PstI (F10). Animals were crossed with Rosa26-rtTA animal of the same background (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA).27 SystemicIndmito-PstI mice were bred with p21KO and p53KO mice of the same background (Jackson Laboratories).39, 40

All mice procedures were performed according to a protocol approved by the University of MiamiI ACUC. When mito-PstI was induced at 3 months of age, we supplied both control and SystemicIndmito-PstI animals with 10 g/kg doxycycline diet (Bioserv, Flemington, NJ, USA) for 5 days and afterwards replaced with standard rodent diet.

For the NAC treatment, mice were given free access to drinking water starting 2 days before the DOX induction and during the 5 days of induction. Water was supplemented with 20 mM NAC, which was calculated to yield an average dose of 2 g NAC/kg body weight/day.

All experiments and comparisons described were performed on age- and gender-matched animals. Analyses were performed on both males and females separately and, unless noted, there were no significant changes between the genders.

Cell culture

The generation and maintenance of gorilla ρ+ and ρ° cell lines, and mito-ScaI cell line were previously described.53 Mito-ScaI cell line were treated with 10 μM Etoposide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24 h. Mito-PstI transfection was performed using GenJet In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol and proteins were extracted after 24 h of transfection. NAC was added fresh and adjusted the pH to 7.4.

Growth curves

Cells were counted and re-plated in 24-well plates at 5 × 10^3~10^4 cells/well. For growth curve cells were treated with 10 μM mifepristone for 30 min or left untreated. Cells were counted in triplicate every 24 h using a TC10 Cell Counter (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) for up to 72 h.

Western blotting

Western blotting procedures were previously described.54 Membranes were blocked in 1:1 Odyssey blocking solution (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) or 5% milk for 1 h at room temperature.

Primary antibody was incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: HA 1 : 1000 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), α-tubulin and β-actin 1 : 5000 (Sigma), PstI 1:100055), p21 1:1000 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), NDUFB8 1:1000 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), SOD-2 1:2000 (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). From Cell Signaling (Boston, MA, USA): phosphorylated MDM2 1:1000, p38 MAPK 1:2000, phospho-p38 MAPK 1:1000, JNK1 1:1000, phospho-SAPK/JNK 1:1000, CHOP 1:500, Hsp60 1:1000, Hsp70 1:1000, Grp78/BiP 1:1000.

Secondary antibodies used were either infrared conjugated antibodies anti-rabbit-700/anti-mouse-800/anti-rat-800 (Rockland, Limerick, PA, USA) or HRP conjugated (Cell Signaling) at 1:3000-1 : 5000 concentrations. Secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Blots with infrared secondary antibodies were visualized with Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). Blots with HRP secondary antibodies were visualized with Pico or Femto Supersignal West Chemiluminescent substrates (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Optical density measurements were taken by default software supplied by LI-COR or quantified using ImageJ.

RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase PCR

Dissected tissues or cells were submerged in TRIzol or TRI reagent (Sigma/Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), and RNA was extracted. The iScript cDNA synthesis kit was used for reverse transcription reaction according to the manufacturer's protocol (BioRad).

Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR master mix (Fermentas, Waltham, MA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer's directions to perform real-time PCR. Primers and sequences used for the cDNA quantification are available under request.

ND1 and β-actin (internal genomic DNA control) were used for the quantification of mtDNA copy number in total DNA. 8378F, 12821 B (small deletion ~3.8 Kb); 5549F, 15501 B (large deletion ~10.6 Kb) were used for the quantification of the small and large deletion in total DNA.28 Comparative Ct method was used to determine the relative abundance of mtDNA or genes of interest.56

Thymocyte isolation and characterization

Single cell suspension of thymocytes was prepared and cell surface staining was performed as previously described.57 Conjugated antibodies PE-Cy7-CD4 and PE-CD25 were purchased from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). FITC-CD44 and Alexa700-CD8 were prepared in T.R. Malek's laboratory (Miami, FL, USA). FACS analyses were performed on an LSR-Fortessa-HTS flow cytometer with FACS Diva software (Becton Dickenson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). 500 000 events were obtained per sample.

Immunocytochemistry/immunohistochemistry

Cells were grown on top of glass coverslips. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. Cells were then treated with 0.1 M glycine and permeabilized with 0.1% triton X-100. Cells were blocked in PBS containing 2% BSA and 2% normal goat serum. Primary antibody anti-HA 1 : 100 (Roche), H2AX 1 : 500 (Millipore) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. AlexaFluor488 or 594 goat anti-mouse/anti-rabbit/anti-rat (Invitrogen) antibodies were incubated for 45 min at room temperature. In experiments where mitochondria were visualized, MitoTracker Red (200 nM, Invitrogen) was added to the cells prior to fixation. Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield fluorescent mounting media with or without DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Images were taken with either an LSM510 or LSM710 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA).

TUNEL staining

Cells were treated as indicated and TUNEL assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche). Images were taken with an LSM710 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

β-Galactosidase staining

Thymus sections were processed as mentioned previously and cut at 10 μm. β-galactosidase staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Cell Signaling). Images were taken with an Olympus BX50.

Histology

After perfusing the mice with PBS, organs were extracted and submerged in formalin O.N. We analyzed intestine, testis and bone marrow. Bones were then treated in decalcifying solution (Sigma) for 8 h and then submerged again in formalin. Tissues were then embedded in paraffin and cut with a microtome. Twenty-micrometer sections were subjected to H&E staining (Sigma). Images were taken with an Olympus BX50.

DEXA scanning

DEXA scans were performed using a Lunar PIXImus DEXA scan according to the manufacturer's instructions. Default software was used to quantify total/lean/fat mass, and bone mineral density.

Amplex Red assay

Hydrogen peroxide concentrations were measured by Amplex Red Peroxide/Peroxidase activity (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's directions. Fluorescence was read at excitation 570/emission 585 using a Synergy H1 hybrid plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Fluorescence intensity was also normalized by cell number after the ending of the experiment.

Blood analysis and histological examination

Animals were anesthetized with a DVR-recommended ketamine cocktail, and blood was drawn from the right ventricle. Blood was placed in a plasma separation tube with heparin additives for analysis at the University of Miami Comparative Pathology Laboratory.

Oil Red O staining

Thymus was removed from animals and fixed overnight in 4% PFA. They were subsequently placed in a sucrose gradient (10–30%) and frozen in Tissue Tek O.C.T (Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA) solution. Ten-micrometer sections were cut and stained 10 min in Oil Red O solution prepared according to the manufacturer's directions (EMS, Hatfield, PA, USA). Sections were counterstained for 2 min with Harris' hematoxylin stain (Sigma). Slides were rinsed and mounted in permanent aqueous mounting media (Covance, Hollywood, FL, USA). Images were taken on an Olympus BX50.

Statistics

Two-tailed, unpaired Student t-test was used to determine the statistical significance between the different groups. If more than two groups were analyzed, significance of the differences was evaluated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test. Data are expressed as mean±S.E.M., or S.D. and the numbers of observations/animals used in each experimental series were included in the figure legends. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Wayne E. Balkan from the University of Miami for the access to and the use of the DEXA scan; Dr. Norman H. Altman VMD for consultation on thymus pathology, Dr. Ying Wang, and Dr. Ge Tao from the University of Miami for antibodies and technical assistance. We also thank the University of Miami Comparative Pathology Laboratory for the blood work analysis. This work was supported primarily by the US National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01AG036871. The following grants also helped support this work: NIH 1R01NS079965, 5R01EY010804; the Muscular Dystrophy Association and the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation. We acknowledge support from the NEI center grant P30-EY014801 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Glossary

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- DSBs

double strand breaks

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- COX8

cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIII

- Cdkn1a

cyclin-dependent kinase Inhibitor 1 A (p21/Cip1)

- MDM2

Mouse double minute 2

- NAC

N-acetyl-cysteine

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- DOX

doxycycline

- DEXA

dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- DN

double negative, CD4−/CD8−

- DP

double positive CD4+/CD8+

- PGC

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivators

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma

- ADRP

adipose differentiation related protein

- SystemicIndmito-PstI

systemic-inducible mitochondrial-targeted PstI

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by N Chandel

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Johnson FB, Sinclair DA, Guarente L. Molecular biology of aging. Cell 1999; 96: 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelnikova OA, Horikawa I, Zimonjic DB, Popescu NC, Bonner WM, Barrett JC. Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol 2004; 6: 168–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel H, Lim DS, Karsenty G, Finegold M, Hasty P. Deletion of Ku86 causes early onset of senescence in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 10770–10775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga M, Bunting S, Montana MF, Soria R, Mulero F, Canamero M et al. A mouse model of ATR-Seckel shows embryonic replicative stress and accelerated aging. Nat Genet 2009; 41: 891–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata K, Aoto T, Binh NT, Okamoto N, Tanimura S, Wakayama T et al. Genotoxic stress abrogates renewal of melanocyte stem cells by triggering their differentiation. Cell 2009; 137: 1088–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzankina Y, Schoppy DW, Asare A, Clark CE, Vonderheide RH, Brown EJ. Tissue regenerative delays and synthetic lethality in adult mice after combined deletion of Atr and Trp53. Nat Genet 2009; 41: 1144–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzankina Y, Pinzon-Guzman C, Asare A, Ong T, Pontano L, Cotsarelis G et al. Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell 2007; 1: 113–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier F, Campisi J, Bhaumik D. Two faces of p53: aging and tumor suppression. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35: 7475–7484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renault VM, Thekkat PU, Hoang KL, White JL, Brady CA, Kenzelmann Broz D et al. The pro-longevity gene FoxO3 is a direct target of the p53 tumor suppressor. Oncogene 2011; 30: 3207–3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudkov AV, Gurova KV, Komarova EA. Inflammation and p53: a tale of two stresses. Genes Cancer 2011; 2: 503–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Lin M, Wu R. The regulation of aging and longevity: a new and complex role of p53. Genes Cancer 2011; 2: 443–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 2005; 120: 483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher B, van der Pluijm I, Moorhouse MJ, Kosteas T, Robinson AR, Suh Y et al. Delayed and accelerated aging share common longevity assurance mechanisms. PLoS Genet 2008; 4: e1000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarroll SA, Murphy CT, Zou S, Pletcher SD, Chin CS, Jan YN et al. Comparing genomic expression patterns across species identifies shared transcriptional profile in aging. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn JM, Sonu R, Vogel H, Crane E, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Rabkin R et al. Transcriptional profiling of aging in human muscle reveals a common aging signature. PLoS Genet 2006; 2: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, de Bruijn MH, Coulson AR, Drouin J et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 1981; 290: 457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J gerontol 1956; 11: 298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. Environ mol mutagen 2010; 51: 440–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermulst M, Bielas JH, Kujoth GC, Ladiges WC, Rabinovitch PS, Prolla TA et al. Mitochondrial point mutations do not limit the natural lifespan of mice. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 540–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermulst M, Wanagat J, Kujoth GC, Bielas JH, Rabinovitch PS, Prolla TA et al. DNA deletions and clonal mutations drive premature aging in mitochondrial mutator mice. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 392–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar CE, Dues DJ, Spielbauer KK, Machiela E, Cooper JF, Senchuk M et al. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS have opposing effects on lifespan. PLoS genet 2015; 11: e1004972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk JM, Hekimi S. Deletion of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase sod-2 extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS genet 2009; 5: e1000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacman SR, Williams SL, Moraes CT. Intra- and inter-molecular recombination of mitochondrial DNA after in vivo induction of multiple double-strand breaks. Nucleic acids res 2009; 37: 4218–4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeke A, Misheva M, Remenyi A, Bogoyevitch MA. JNK signaling: regulation and functions based on complex protein-protein partnerships. Microbiol mol biol rev 2016; 80: 793–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi A, Ramesh R. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and their role in radiation response. Genes cancer 2013; 4: 401–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SB, Bae IH, Bae YS, Um HD. Link between mitochondria and NADPH oxidase 1 isozyme for the sustained production of reactive oxygen species and cell death. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 36228–36235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belteki G, Haigh J, Kabacs N, Haigh K, Sison K, Costantini F et al. Conditional and inducible transgene expression in mice through the combinatorial use of Cre-mediated recombination and tetracycline induction. Nucleic Acids Res 2005; 33: e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui H, Moraes CT. Mechanisms of formation and accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletions in aging neurons. Hum mol genet 2009; 18: 1028–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awong G, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Thymus-bound: the many features of T cell progenitors. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011; 3: 961–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinova TT. Epithelial framework reorganization during human thymus involution. Gerontology 2005; 51: 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P, Wu ZD, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 1998; 92: 829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, Bradwin G, Moore K, Milstone DS et al. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell 1999; 4: 611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun RP, Tontonoz P, Forman BM, Ellis R, Chen J, Evans RM et al. Differential activation of adipogenesis by multiple PPAR isoforms. Gene Dev 1996; 10: 974–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano G, Levine AJ. Tissue-specific expression of P53 in transgenic mice is regulated by intron sequences. Mol Carcinogen 1991; 4: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H et al. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature 2002; 415: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DP, Ou LD, Clemenson GD, Chao C, Lutske ME, Zambetti GP et al. Puma is required for p53-induced depletion of adult stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12: 993–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin MF, Gueven N. The complexity of p53 stabilization and activation. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlqvist KJ, Hamalainen RH, Yatsuga S, Uutela M, Terzioglu M, Gotz A et al. Somatic progenitor cell vulnerability to mitochondrial dna mutagenesis underlies progeroid phenotypes in polg mutator mice. Cell Metab 2012; 15: 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Leder P. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell 1995; 82: 675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT et al. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr biol 1994; 4: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey G, Campbell C. An alternate form of Ku80 is required for DNA end-binding activity in mammalian mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res 2000; 28: 3793–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmipathy U, Campbell C. Mitochondrial DNA ligase III function is independent of xrcc1. Nucleic Acids Res 2000; 28: 3880–3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmipathy U, Campbell C. The human DNA ligase III gene encodes nuclear and mitochondrial proteins. Mol Cell Biol 1999; 19: 3869–3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JS, Lin ZP, Sartorelli AC, Bonawitz ND, Shadel GS. Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase regulates ribonucleotide reductase and mitochondrial homeostasis. J Clin Invest 2007; 117: 2723–2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin-Vega YA, MacLean KH, Tait-Mulder J, Milasta S, Steeves M, Dorsey FC et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in ataxia-telangiectasia. Blood 2012; 119: 1490–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage JM, Gildemeister OS, Knight KL. Discovery of a novel function for human Rad51 maintenance of the mitochondrial genome. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 18984–18990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayona-Bafaluy MP, Blits B, Battersby BJ, Shoubridge EA, Moraes CT. Rapid directional shift of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy in animal tissues by a mitochondrially targeted restriction endonuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 14392–14397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Pickrell AM, Rossi SG, Pinto M, Dillon LM, Hida A et al. Transient systemic mtDNA damage leads to muscle wasting by reducing the satellite cells pool. Hum mol genet 2013; 22: 3976–3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Kozlov S, Lavin MF, Person MD, Paull TT. ATM activation by oxidative stress. Science 2010; 330: 517–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman P, Ponder R, Lo HH, Ishii N. Mitochondrial oxidative stress can lead to nuclear hypermutability. Mech Ageing Dev 2004; 125: 417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen KH, Cheng C, Wiksen H, Bergersen LH, Klungland A. Mitochondrial DNA toxicity compromises mitochondrial dynamics and induces hippocampal antioxidant defenses. DNA Repair 2011; 10: 639–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjoismaki JL, Williams SL, Boettger T, Goffart S, Kim J, Suomalainen A et al. Overexpression of Twinkle-helicase protects cardiomyocytes from genotoxic stress caused by reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 19408–19413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacman SR, Williams SL, Moraes CT. Intra- and inter-molecular recombination of mitochondrial DNA after in vivo induction of multiple double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37: 4218–4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell AM, Fukui H, Wang X, Pinto M, Moraes CT. The striatum is highly susceptible to mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation dysfunctions. J neurosci 2011; 31: 9895–9904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Moraes CT. Manipulating mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy by a mitochondrially targeted restriction endonuclease. Hum mol genet 2001; 10: 3093–3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C-T method. Nat Protoc 2008; 3: 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer AL, Yu AX, Malek TR. Function of the IL-2R for thymic and peripheral CD4(+)CD25(+) Foxp3(+) T regulatory cells. J Immunol 2007; 178: 4062–4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.