Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) acquired during hospitalization is common, yet preventable by the proper implementation of thromboprophylaxis which remains to be underutilized worldwide. As a result of an initiative by the Saudi Ministry of Health to improve medical practices in the country, an expert panel led by the Saudi Association for Venous Thrombo Embolism (SAVTE; a subsidiary of the Saudi Thoracic Society) with the methodological guidance of the McMaster University Guideline working group, produced this clinical practice guideline to assist healthcare providers in VTE prevention. The expert part panel issued ten recommendations addressing 10 prioritized questions in the following areas: thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients (Recommendations 1-5), thromboprophylaxis in critically ill medical patients (Recommendations 6-9), and thromboprophylaxis in chronically ill patients (Recommendation 10). The corresponding recommendations were generated following the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common complication of acute medical illness.1,2 Despite being a largely preventable condition, it remains a leading cause of mortality, morbidity, and increased healthcare cost.1,3,4 Acutely and critically ill medical patients as well as chronically ill patients are especially at risk of developing VTE.2,5 Risk factors include but not limited to severe illness, sedating medications, and invasive procedures.2,6 Heparin administration for at risk patients has been shown to reduce VTE incidence, but also to increase the risk of bleeding.7,8 Hence, the benefits of anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis may be outweighed by its potential complications. Mechanical prophylaxis with either graduated compression stockings (GCS), or intermittent pneumatic compression devices (IPC; also known as sequential compression devices [SCDs]) might be an appropriate alternative in patients with contra-indications for anticoagulants.9 However, its effectiveness in VTE prevention is less clear.

Thromboprophylaxis is underutilized in hospitalized patients worldwide. In the Epidemiologic International Day for the “Evaluation of Patients at Risk for Venous Thromboembolism in the Acute Hospital Care Setting” (ENDORSE) study, a multi-national survey, only 39.5% of hospitalized medical patients at VTE risk received evidence-based thromboprophylaxis.10 There is a similar evidence for suboptimal use of thromboprophylaxis in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).11 One study assessed VTE-related morbidity and mortality in King Fahad General Hospital in Jeddah and found a period prevalence of 500 hospital-acquired clinically-diagnosed VTE cases between July 2008 and June 2009.11 Only 36.5% of these patients had received thromboprophylaxis with the case fatality rate of 31% for patients who did not receive thromboprophylaxis and 3.1% for those who received it.11 Multiple guidelines on thromboprophylaxis in medical patients exist;12,13 however, none is specific to KSA, or to the region.

In view of the importance of this topic and due to thromboprophylaxis underutilization, the Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH), the Saudi Association for Venous Thromboembolism (SAVTE) with the methodological guidance of the McMaster University guidelines group produced this clinical practice guideline on VTE prevention in medical and critically ill patients. The full guideline is available at: http://www.moh.gov.sa/depts/Proofs/Pages/Guidelines.aspx.14

Methods

In 2013, the Saudi MOH established a program for the development of guidelines for the management of prevalent medical conditions. The aim was to provide guidance for clinicians, other healthcare providers and decision makers and to reduce clinical practice variability across KSA. Therefore, the Saudi MOH, through the Saudi Center for Evidence Based Healthcare (EBHC), contracted the McMaster University working group to provide methodological guidance for this guideline development. It also contacted the Saudi Association for SAVTE, which nominated a group of clinicians from various specialties to serve as the expert panel for generating VTE prophylaxis guidelines. Using a formal prioritization process, the expert panel selected the topic of this guideline and all clinical questions addressed herein. The panel followed the Guidelines International Network (GIN)-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist and the Saudi Handbook for Guideline Development.15,16

For all selected questions, the McMaster group updated the existing systematic reviews on the health effects of thromboprophylaxis in medical and critically ill patients.1,2 Also, the group conducted systematic searches for information relating to patients’ values and preferences, costs, and resource use that were specific to the Saudi context. Based on these reviews, the McMaster group prepared summaries of the available evidence supporting each recommendation using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.17 Quality of evidence (confidence in the effect estimates) was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low, taking into consideration factors that may downgrade (risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision and publication bias) and upgrade evidence quality.18 High-quality evidence indicates that we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality evidence indicates moderate confidence, and that the true effect is likely close to the estimate of the effect. Low-quality evidence indicates that our confidence in the effect estimate is limited, and that the true effect may be substantially different. Finally, very low-quality evidence indicates that the estimate of effect of interventions is very uncertain, the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the effect estimate and further research is likely to reduce this uncertainty.

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation evidence-to-decision frameworks drafted by the McMaster group served the guideline panel to follow a structured consensus process.19-21 Potential conflicts of interests of all panel members were managed according to the World Health Organization rules.22 The guideline panel met in Riyadh on March 15 & 16, 2015 and issued all recommendations. All decisions were transparently documented in the evidence-to-decision frameworks.

The selected questions

The 10 clinical questions addressed thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients, critically ill medical patients, and chronically ill patients. For details on the process by which the questions were selected, please refer to the separate publication on this project methodology.23 In this document, acutely ill medical patients were defined as patients suffering from an acute illness and ill enough to be hospitalized, but not be admitted to a critical care unit. Critically ill medical patients were defined as patients suffering from acute illness that were ill enough to be admitted to a critical care unit. Chronically ill medical patients were defined as patients suffering from a chronic illness and were typically bedridden.

Grading the strength of recommendations

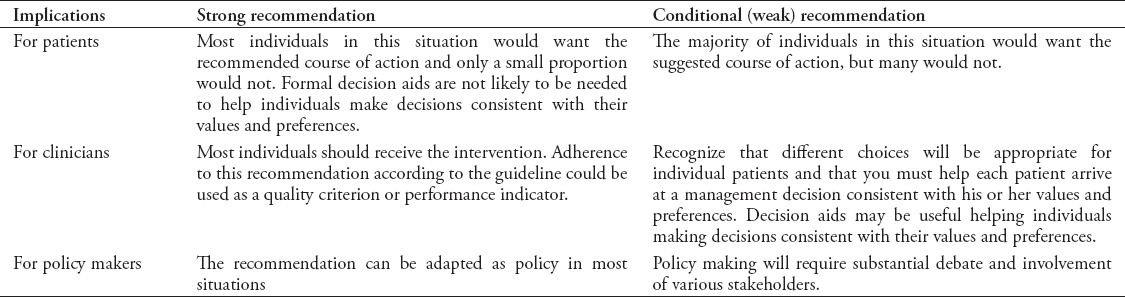

The GRADE Working Group defined the strength of recommendation as the degree that we can be confident that the desirable effects of an intervention outweigh its undesirable effects. According to the GRADE approach, the strength of a recommendation can be either strong (worded as ‘guideline panel recommends…’) or conditional/weak (worded as ‘guideline panel suggests…’). Table 1 provides the implications of the recommendation strength.24 Understanding these implications is essential for their appropriate use.

Table 1.

Interpretation of strong and conditional (weak) recommendations according to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach

Results

The panel provided recommendations addressing thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients (Recommendations 1-5), in critically ill medical patients (Recommendations 6-9), and in chronically ill patients (Recommendations 10). The recommendations were made taking into account the available evidence, resource use, patient preference, and the Saudi context.

Thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients.

Question 1: Should heparin versus no heparin be used for VTE prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients?

Summary of findings

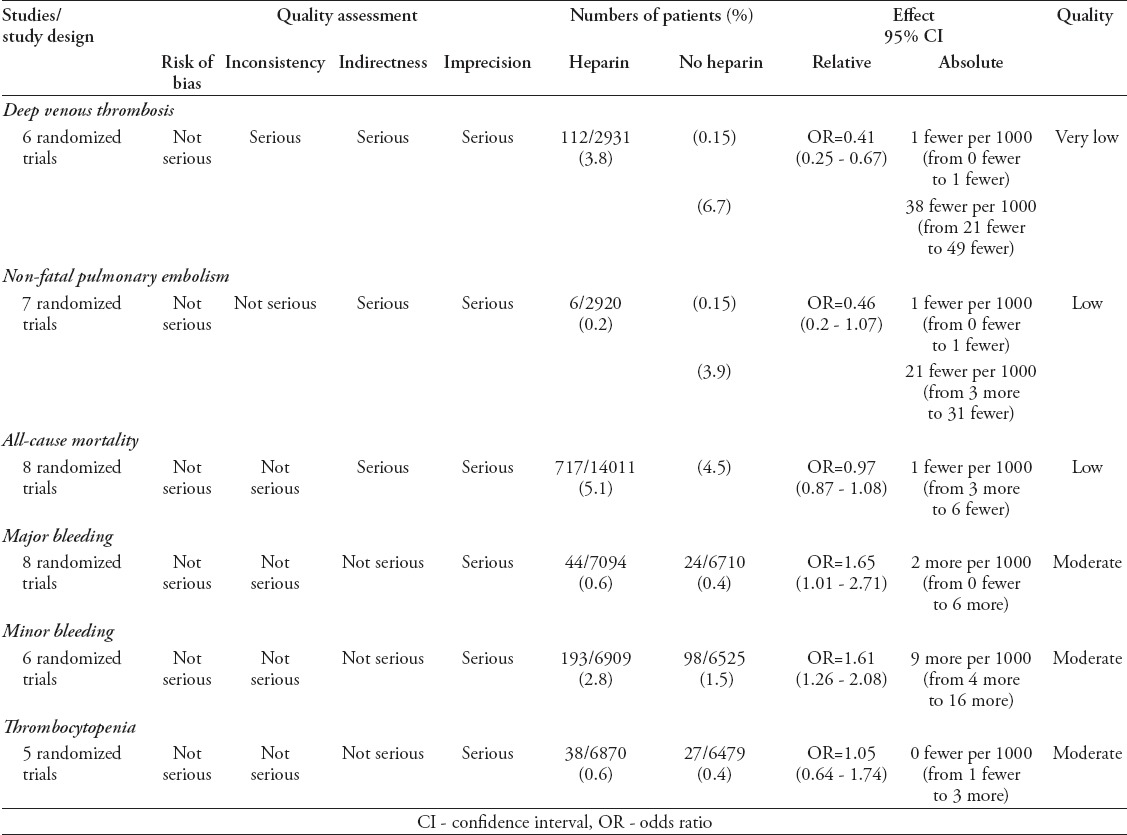

We updated the 2014 systematic review by Alikhan et al,1 but did not identify new studies. The overall quality of evidence was judged to be low. The studies included in the systematic review typically defined acutely ill patients as patients hospitalized for acute medical illness (for example, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), with a decrease in mobility. The summary of findings are shown in Table 2.1 The baseline risks for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) outcomes for the low-risk and high-risk subgroups are based on a risk assessment model by Barbar et al.25 The baseline risk for mortality is based on the findings of a systematic review by Dentali et al.26

Table 2.

Heparin compared to no heparin for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis of in acutely ill medical patients.

Benefits and harms of the option

The meta-analysis of 6 trials (5,944 participants) found very low-quality evidence of a reduction in DVT with heparin use compared to no heparin for thromboprophylaxis. The meta-analysis of 7 trials (5939 participants) found low-quality evidence of a reduction in non-fatal PE with heparin use compared to no heparin for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 8 trials (27,980 participants) found low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in all-cause mortality with heparin compared to no heparin for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 8 trials (13804 participants) found moderate quality evidence of an increase in major bleeding with heparin compared to no heparin for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 6 trials (13434 participants) found moderate quality evidence of an increase in minor bleeding with the use of heparin compared to no heparin for prophylaxis of DVT in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 5 trials (13349 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in thrombocytopenia with heparin compared to no heparin for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients.

Resource use

The panel judged heparin cost to be low but to only be cost-effective in high-risk patients.

Feasibility, acceptability and equity considerations

The panel judged heparin use for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients to be both feasible and acceptable by all relevant stakeholders because of patient safety. Additionally, the panel judged heparin use in this population to unlikely impact health inequity.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel judged heparin benefits to clearly outweigh its harms in high-risk patients, but less clearly in low-risk patients. Evidence certainty was considered moderate in high-risk patients and low in low-risk patients. The panel deemed the intervention to be of low-cost, cost-effective (in high-risk patients), feasible, and acceptable.

Recommendation 1.

1a) In acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at high risk of VTE the panel recommends heparin unfractionated heparin (UFH)/low molecular weight heparin over no heparin for VTE prophylaxis (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence).

1b) In acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at low risk of VTE, the panel suggests against heparin for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, low quality evidence).

Remarks

Risk stratification should be based on a validated risk stratification tool (for example, Padua Prediction Score).27

Decision to provide thromboprophylaxis should consider the patients’ risk of bleeding.

Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring the frequency of risk stratification and the compliance with heparin thromboprophylaxis is recommended.

Research priorities

The panel highlighted the need for studies addressing the following research priorities in KSA: impact of guideline implementation on clinical practice, VTE incidence and major bleeding in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients, values and preferences for giving heparin in different subgroups of acutely ill medical patients, and economic evaluation, including cost effectiveness.

Question 2: Should low molecular weight heparin versus UFH be used for VTE prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients?

Summary of findings

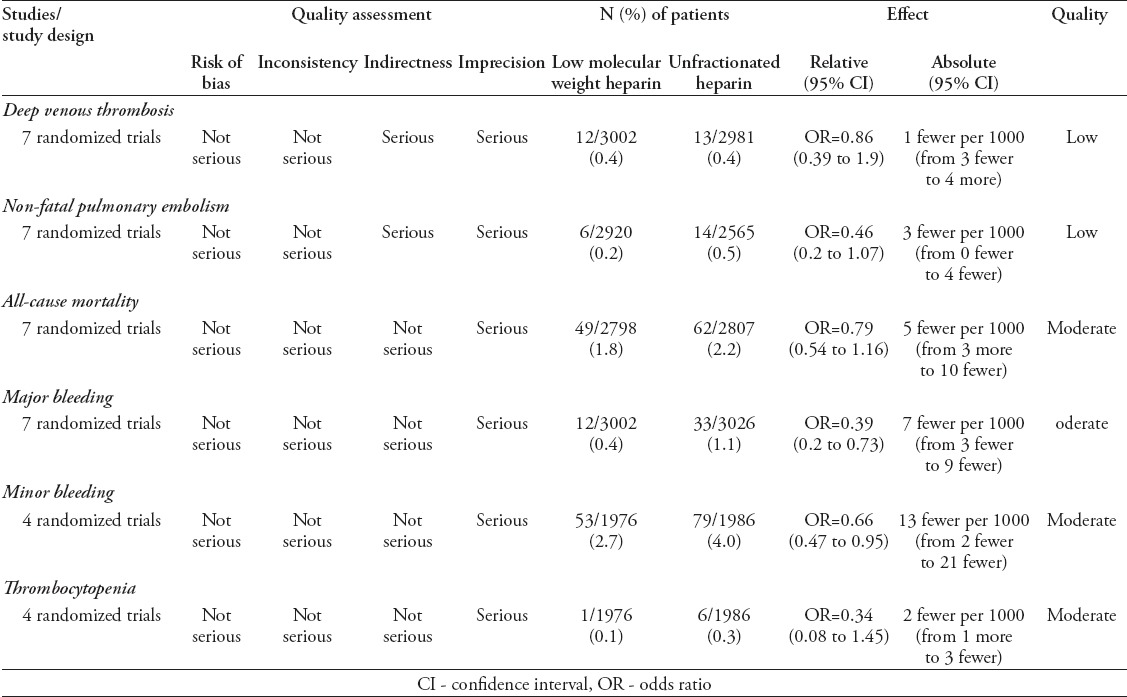

The findings are primarily derived from a 2014 systematic review by Alikhan et al,1 The updated literature search identified a 2013 randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Ishi et al.28 The overall quality of evidence was deemed to be moderate. The summary of evidence is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Low molecular weight heparin compared to unfractionated heparin for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients.

Benefits and harms of the option

The meta-analysis of 7 trials (5983 participants) found low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in DVT with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH)compared to UFH for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 7 trials (5485 participants) found low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in non-fatal PE with LMWH compared to UFH for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 7 trials (5605 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in all-cause mortality with LMWH compared to UFH for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients.

The meta-analysis of 7 trials (6028 participants) found moderate quality evidence of a reduction in major bleeding with the use of LMWH compared to UFH for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 4 trials (3962 participants) found moderate quality evidence of a reduction in minor bleeding with the use of LMWH compared to UFH for Thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 4 trials (3962 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in thrombocytopenia with the use of LMWH compared to UFH for Thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients.

Resource use

The panel thought that there would be a variation in the cost across different hospital settings and deemed the nursing costs to be higher with UFH because it is given 3 times daily. The panel judged LMWH to be cost-effective.

Feasibility, acceptability and equity considerations

The panel judged LMWH use for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients to be both feasible and acceptable by patients and nurses. The panel also considered LMWH in this population to unlikely impact health inequity.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel considered LMWH benefits to probably outweigh its harms in acutely ill medical patients.

Recommendation 2:

In acutely ill hospitalized medical patients the panel suggests using low molecular weight heparin over UFH for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, low quality evidence)

Remark

In case of renal failure, UFH use is preferred.

Implementation considerations

Consider having anti-factor Xa assay made available for LMWH monitoring in pregnant and renal impairment subpopulations.

Research priorities

Studies on cost effectiveness are needed.

Question 3: Should extended duration (that is up to 30 or 40 days) versus a regular duration (up to 10 days) be used for the thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients?

Summary of findings

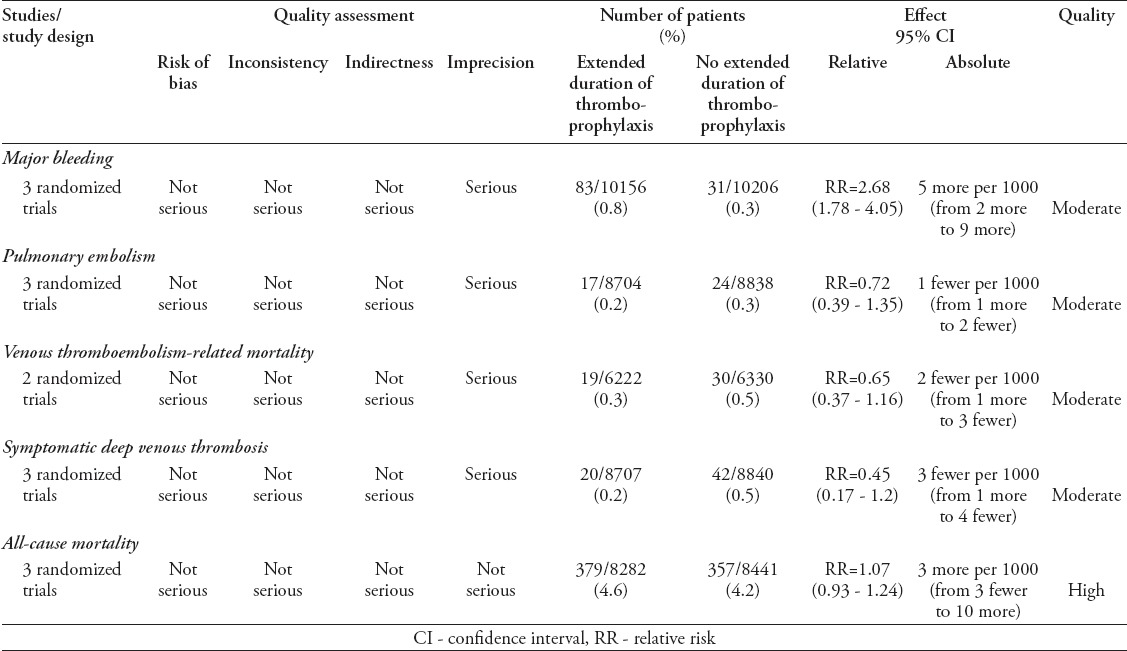

The definition of extended duration thromboprophylaxis is prophylaxis that is extends beyond the regular course of 10 days, and up to 30-40 days in total. We updated the systematic review by Sharma et al,29 but did not identify new studies. The overall evidence quality was moderate. The summary of evidence is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Extended duration compared to regular duration for the thromboprophylaxis of VTE in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients

Benefits and harms of the option

The meta-analysis of 3 trials (20362 participants) found moderate quality evidence of an increase in major bleeding with the use of extended thromboprophylaxis duration compared to no extended thromboprophylaxis duration for acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 3 trials (17542 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in PE with the use of extended thromboprophylaxis duration compared to no extended thromboprophylaxis duration for acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 2 trials (12552 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in VTE- related mortality with the use of extended thromboprophylaxis duration compared to no extended thromboprophylaxis duration for acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 3 trials (17547 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in symptomatic DVT with the use of extended thromboprophylaxis duration compared to no extended thromboprophylaxis duration for acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 3 trials (16723 participants) found high-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in all-cause mortality with the use of extended thromboprophylaxis duration compared to no extended thromboprophylaxis duration for acutely ill hospitalized medical patients.

Resource use

The panel judged the cost of heparin to be probably high because of the cost required to educate patients and the cost of the medication itself. The panel judged the intervention to probably not be cost-effective.

Feasibility, acceptability, and equity considerations

The panel judged the use of extended thromboprophylaxis duration to be probably not acceptable or feasible as health educators are needed.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel judged the harms of extended thromboprophylaxis duration to clearly outweigh its benefits in acutely ill hospitalized patients. Evidence certainty was considered to be moderate. The panel judged the intervention to be probably of high cost, not cost-effective, not feasible and not acceptable.

Recommendation 3:

In acutely ill hospitalized medical patients the panel recommends a regular duration (that is, up to 10 days) over an extended duration (that is, up to 30 or 40 days) for the thromboprophylaxis. (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence)

Research priorities

Studies that identify the subpopulations that would benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis and determine a risk stratification tool are needed.

Question 4: Should GCS versus no GCS be used for hospitalized medical patients?

Summary of findings

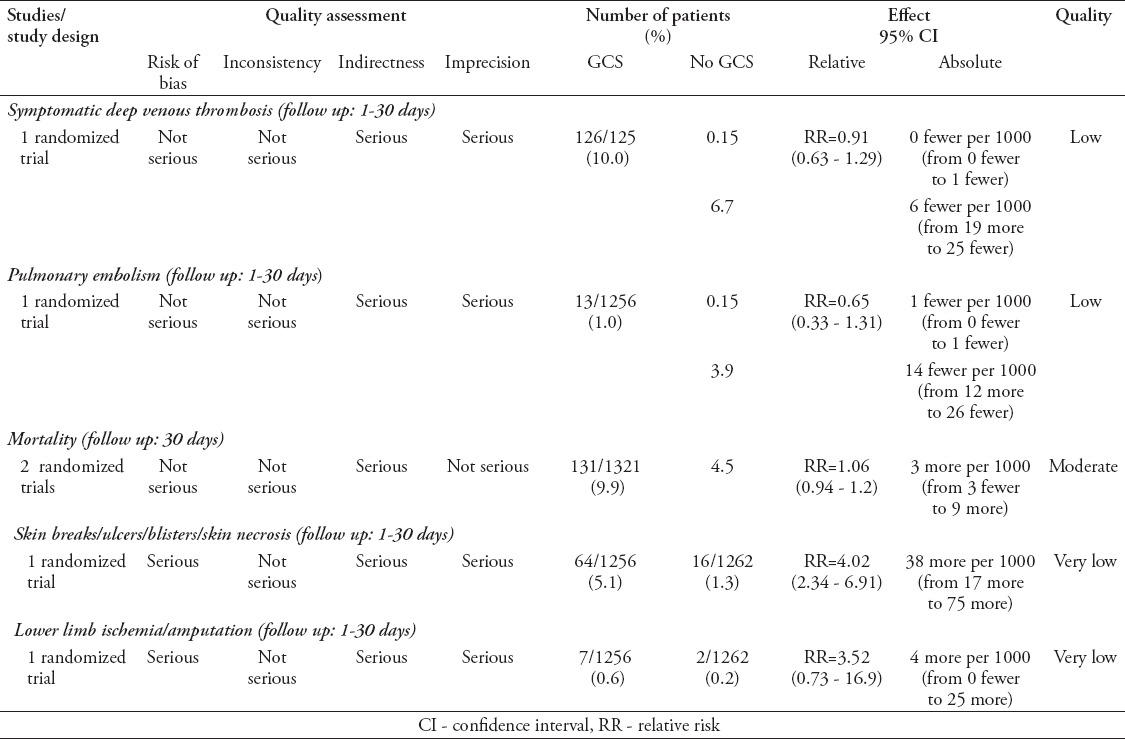

Our systematic search of the literature did not identify studies other than a RCT by Muir et al30 and a 2009 RCT by Dennis et al.9 The summary of findings is shown in Table 5.

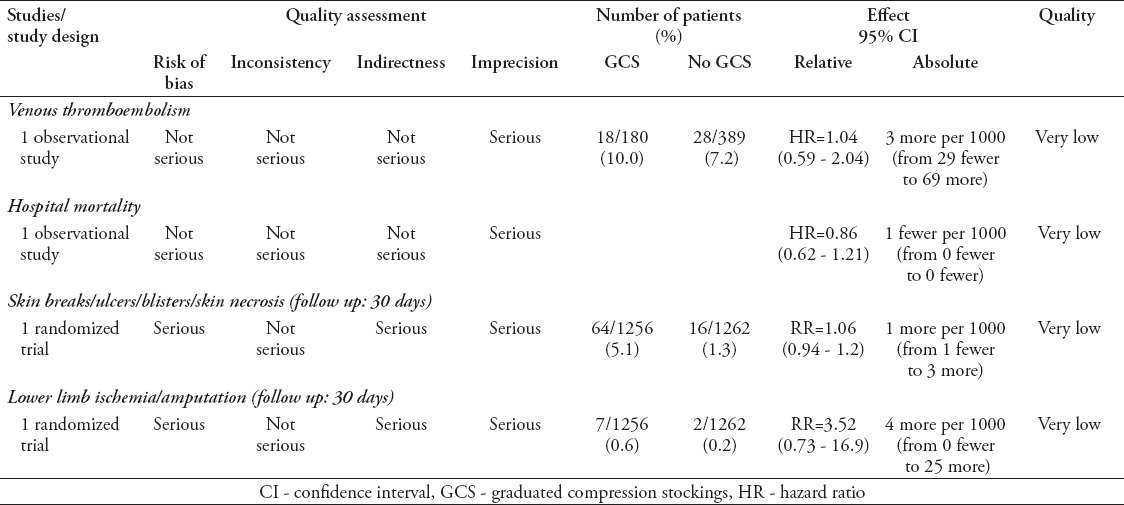

Table 5.

Graduated compression stockings versus no graduated compression stockings in hospitalized medical patients.

Benefits and harms of the option

One trial9 (2518 participants) provided low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in symptomatic DVT (follow up: 1-30 days) with GCS use compared to no GCS in hospitalized medical patients. One trial9 (2518 participants) provided low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in PE (follow up: 1-30 days) with GCS use compared to no GCS in hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 2 trials9,30 (2615 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in mortality (follow up: 1-30 days) with GCS use compared to no GCS in hospitalized medical patients.

One trial9 (2518 participants) provided very low-quality evidence of an increase in skin breaks/ulcers/blisters/skin necrosis (follow up: 1-30 days) with GCS use compared to no GCS in hospitalized medical patients. One trial9 (2518 participants) provided very low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in Lower limb ischemia/amputation (follow up: 1-30 days) with GCS use compared to no GCS in hospitalized medical patients.

Resource use

The panel judged the cost of GCS to be low. But there was no evidence on whether GCS was cost-effective.

Feasibility, acceptability, and equity considerations

The panel judged GCS use to be probably feasible or acceptable. The panel was uncertain about the impact of GCS use on health inequity.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel judged the harms of GCS to outweigh the benefits in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at low-risk of VTE. They judged this balance to be uncertain in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at high-risk of VTE. Evidence certainty was considered to be low. The panel was uncertain about cost effectiveness, and judged the intervention to be probably feasible and acceptable.

Recommendation 4:

4a) In acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at low risk of VTE the panel recommends against using GCS for VTE prophylaxis (strong recommendation, low quality evidence).

4b) In acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at high risk of VTE and bleeding (who cannot receive pharmacological prophylaxis), the panel suggests using GCS for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, low quality evidence).

Remarks

Consider monitoring for skin lesions and ischemia

Physician must ensure proper fitting

Monitoring and evaluations

Monitoring GCS use in acutely ill low- and high-risk medical patients is advocated.

Research priorities

More trials in non-stroke medical patients are needed.

Question 5: Should IPC versus no IPC be used for hospitalized medical patients?

Summary of findings

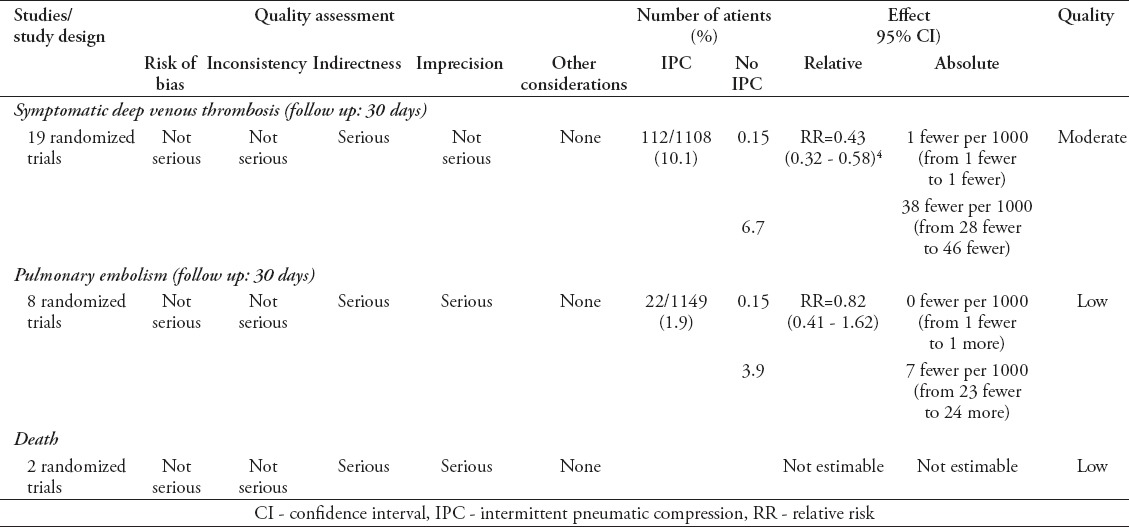

We updated a systematic review by Roderick et al,31 which was on surgical patients and thus was considered as indirect evidence,31 but we did not identify new studies. The overall quality of evidence was judged to be low. The summary of evidence is shown in Table 6.

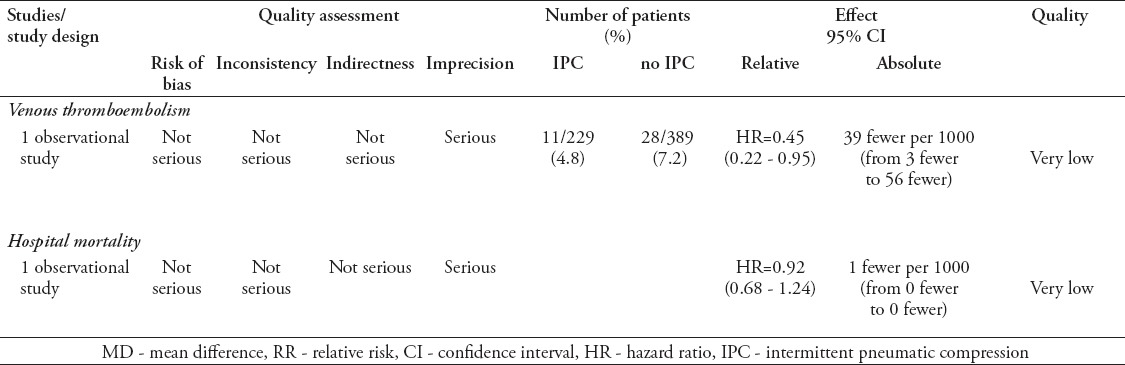

Table 6.

Intermittent pneumatic compression devices versus no intermittent pneumatic compression devices in hospitalized medical patients

Benefits and harms of the option

The meta-analysis of 19 trials found moderate quality evidence of a reduction in symptomatic DVT (follow up of 30 days) with the use of IPC compared to no IPC in hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 8 trials found low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in PE (follow-up of 30 days) with IPC use compared to no IPC in hospitalized medical patients. The meta-analysis of 2 trials (2518 participants) found low-quality evidence that could not estimate the absolute effect of IPC use compared to no IPC use in hospitalized medical patients.

There were no studies that reported skin breaks/ulcers/blisters/skin necrosis as an outcome and therefore we could not estimate the absolute effect of IPC use compared to no IPC use in hospitalized medical patients related to this outcome.

Resource use

The panel judged IPC cost to probably not be low and was uncertain whether IPC use is cost-effective because of lacking evidence.

Feasibility, acceptability, and equity considerations

The panel judged IPC use to be probably feasible, but feasibility may vary between hospitals and that IPC use is less acceptable by patients. The panel judged IPC use to impact health inequity and noted that its cost and availability need to be considered.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel judged the harms of IPC/sequential compression device (SCD) to probably outweigh the benefits in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at low-risk of VTE. The balance was uncertain in patients at high-risk of VTE. Evidence certainty was considered to be low. The panel was uncertain about the intervention cost effectiveness and acceptability. It judged the intervention to probably increase inequity and to be probably feasible.

Recommendation 5:

5a) In acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at low risk of VTE, the panel recommends against using intermittent IPC for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, low quality evidence).

5b) In acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at high risk of VTE and bleeding (who should not receive pharmacological prophylaxis), the panel suggests using intermittent IPC for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, low quality evidence).

Remarks

The choice between mechanical prophylaxis options (GCS over intermittent pneumatic compression/sequential compression device) will depend on the local availability and patient preference.

Implementation considerations

Administrators considering the use of SCD, need to take into account for both its capital and operational costs.

Monitoring and evaluation

The panel advocated that hospitals monitor adherence of IPC use and that compressive lower extremity ultrasound should be considered in patients who have been hospitalized for >72 hours without any thromboprophylaxis.

Research priorities

Additional studies on IPC effectiveness are needed.

Thromboprophylaxis in critically ill medical patients

Question 6: Should heparin versus placebo be used for critically ill patients?

Summary of findings

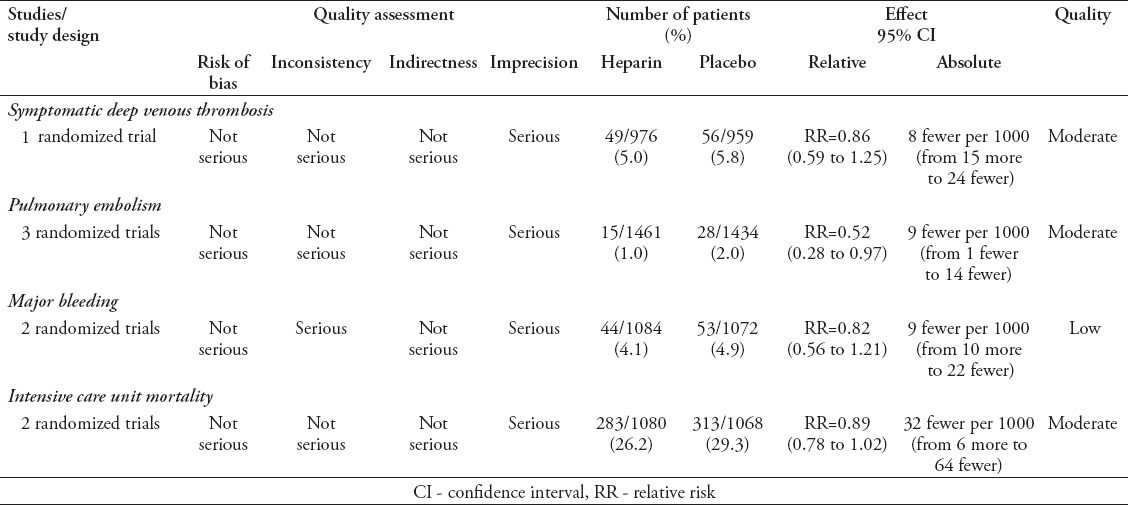

We updated a systematic review by Alhazzani et al,2 but did not identify new studies. The overall quality of evidence was judged to be low. In the systematic review, critically ill patients were defined as those being cared for in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting. The summary of evidence is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Heparin compared to placebo for critically ill patients.

Benefits and harms of the option

One trial (1935 participants) provided moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in symptomatic DVT with the use of heparin compared to placebo in critically ill patients. The meta-analysis of 2 trials (2895 participants) found moderate quality evidence of a reduction in PE with the use of heparin compared to placebo in critically ill patients. The meta-analysis of 2 trials (2156 participants) found low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in major bleeding with the use of heparin compared to placebo in critically ill patients. The meta-analysis of 2 trials (2148 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in ICU mortality with heparin use compared to placebo in critically ill patients.

Resource use

The panel judged heparin cost to be small and to probably be cost-effective, as appropriate prophylaxis provides better value in terms of costs and health gains than routine DVT screening.

Feasibility, acceptability and equity considerations

The panel judged heparin use to be both feasible and acceptable. The panel were uncertain about the impact of heparin use on health inequity in critically ill patients.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences: The panel judged heparin benefits to probably outweigh its harms in critically ill medical patients. Evidence certainty was considered to be low. The panel judged the intervention to be low-cost, probably cost-effective, feasible and acceptable.

Recommendation 6:

In critically ill medical patients the panel recommends heparin over no heparin for VTE prophylaxis (strong recommendation, low quality evidence).

Remark

Decision to provide thromboprophylaxis should consider the patients’ risk of bleeding

Implementation considerations and monitoring

Monitoring percentage of critically ill medical patients receiving heparin should be considered

Research priorities

Additional research on this topic in critically ill patient population is needed.

Question 7: Should LMWH versus UFH be used for critically ill patients?

Summary of findings

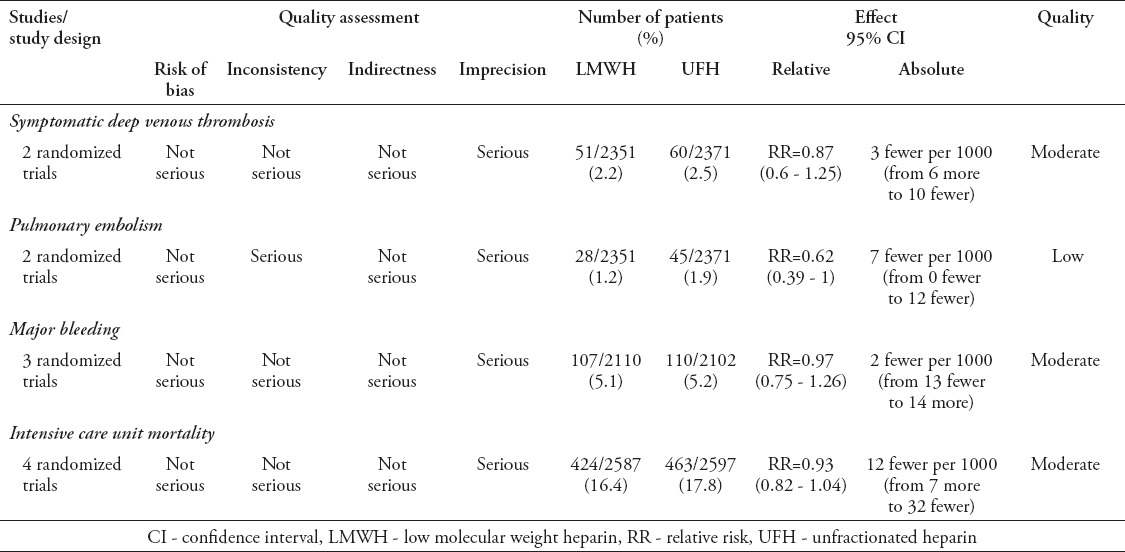

We updated a systematic review by Alhazzani et al,2 but did not identify new studies. The overall quality of evidence was judged to be moderate. The summary of evidence is shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Low molecular weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin for critically ill patients

Benefits and harms of the option

The meta-analysis of 2 trials (4722 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in symptomatic DVT with LMWH compared to UFH in critically ill patients. The meta-analysis of 2 trials (4722 participants) found low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in PE with the use of LMWH compared to UFH in critically ill patients. The meta-analysis of 3 trials (4212 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in major bleeding with the use of LMWH compared to UFH in critically ill patients. The meta-analysis of 4 trials (5184 participants) found moderate quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in ICU mortality with the use of LMWH compared to UFH in critically ill patients.

Resource use

The panel judged LMWH cost to be small and to probably be cost-effective, as appropriate prophylaxis provides better value in terms of costs and health gains than routine DVT screening.32

Feasibility, acceptability, and equity considerations

The panel judged LMWH use to be both feasible and acceptable. The panel were uncertain about the impact of LMWH on health inequity in critically ill patients.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel judged the LMWH benefits to probably outweigh its harms in critically ill medical patients. Evidence certainty was considered to be low. The panel judged the intervention to be low-cost, probably cost-effective, feasible, and acceptable.

Recommendation 7:

In critically ill medical patients, the panel suggests low molecular weight heparin over UFH for the VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, low quality evidence).

Remark

In case of renal failure, use of UFH is preferred.

Implementation considerations and monitoring

Consider having anti-factor Xa for LMWH monitoring made available for pregnant and renal impairment subpopulations.

Research priorities

Conducting cost effectiveness studies should be considered.

Question 8: Should GCS versus no GCS be used for critically ill patients?

Summary of findings

We identified a prospective cohort study by Arabi et al,4 and did not identify any other new studies. The overall quality of evidence was considered very low. Summary of evidence is shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Graduated compression stockings compared to no graduated compression stockings for critically ill patients

Benefits and harms of the option

One observational study (569 participants) provided very low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in VTE with GCS use compared to no GCS in critically ill patients. One observational study (569 participants) provided very low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in hospital mortality with GCS use compared to no GCS in critically ill patients.

One trial (2518 participants) provided very low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in skin breaks/ulcers/blisters/skin necrosis (follow up: 30 days) with GCS use compared to no GCS in critically ill patients. One trial (2518 participants) provided very low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in lower limb ischemia/amputation (follow up: 30 days) with GCS use compared to no GCS in critically ill patients.

Resource use

The panel judged the cost of GCS to be small and to probably not be cost-effective, as appropriate prophylaxis provides better value in terms of costs and health gains than routine screening for DVT.32

Feasibility, acceptability, and equity considerations

The panel judged GCS use to probably be both feasible and acceptable. The panel were uncertain about the impact of LMWH on health inequity in critically ill patients.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel judged the harms of GCS for thromboprophylaxis to probably outweigh the benefits in critically ill medical patients. Evidence certainty was considered to be low. The panel judged the intervention to be low-cost and probably feasible, and acceptable.

Recommendation 8:

8a) In critically ill medical patients, the panel suggests against GCS for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, very low quality evidence).

8b) In critically ill medical patients at high risk of bleeding and in whom pharmacological prophylaxis is not feasible and in settings where intermittent, IPC is not available the panel suggests using GCS for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, very low quality evidence).

Remarks

Consider monitoring for skin lesions and ischemia

Physician must ensure proper fitting

Ensure appropriate use of GCS (thigh length versus knee length)

Implementation considerations

The hospital should acquire different sizes of high-quality GCS.

Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring GCS use should be considered.

Research priorities

Studies on the benefits, harms and cost effectiveness of GCS use in ICU populations are needed.

Question 9: Should IPC versus no IPC be used for critically ill patients?

Summary of findings

We identified a prospective cohort study by Arabi et al,4 and did not identify any other new studies. The overall evidence quality was deemed very low. The summary of evidence is shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Intermittent pneumatic compression compared to no intermittent pneumatic compression for critically ill patients.

Benefits and harms of the option

One study (618 participants) provided very low-quality evidence that showed a reduction in VTE with IPC use compared to no IPC use in critically ill patients. One study found very low-quality evidence that did not rule out a reduction or an increase in hospital mortality with IPC compared to no IPC in critically ill patients.

There were no studies that reported skin breaks/ulcers/blisters/skin necrosis as an outcome. Hence, we could not estimate the related IPC effect in hospitalized medical patients.

Resource use

The panel judged the cost of IPC to be small and to probably be cost effective, as appropriate prophylaxis provides better value in terms of costs and health gains than routine DVT screening.32

Feasibility, acceptability, and equity considerations

The panel judged the feasibility of the use of IPC may vary among hospitals across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and judged that the intervention is probably acceptable. The panel judged IPC impact on health inequity is probably increased due to cost and availability.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel judged the benefits of IPC/SCD for the thromboprophylaxis to probably outweigh the harms in critically ill medical patients who are bleeding or at high risk of bleeding. Evidence certainty was considered to be very low. The panel judged the intervention to be low-cost, probably cost-effective, and probably acceptable.

Recommendation 9:

9a) In critically ill medical patients who are bleeding, or at high risk of bleeding, the panel suggests using intermittent IPC for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, very low quality evidence).

9b) In critically ill medical patients at high risk of VTE receiving pharmacological prophylaxis, the panel suggests adding intermittent IPC for VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, very low quality evidence).

Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring IPC use adherence should be considered.

Research priorities

Additional studies on IPC in ICU populations are needed.

Thromboprophylaxis in chronically ill patients

Question 10: Should thromboprophylaxis be used in chronically ill medical patients?

Summary of findings

Our literature search did not identify any eligible trial.

Benefits and harms of the option

There were no studies that reported DVT, PE, major bleeding, minor bleeding, thrombocytopenia, and all-cause mortality as outcomes. Therefore, we could not estimate thromboprophylaxis effect compared to no thromboprophylaxis in chronically ill medical patients.

Resource use

The panel were uncertain about the cost, or cost-effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis in chronically ill medical patients.

Feasibility, acceptability, and equity considerations

The panel deemed thromboprophylaxis to probably not be feasible, or acceptable in chronically ill medical patients. The panel were uncertain about thromboprophylaxis impact on health inequity in chronically ill patients.

Balance between desirable and undesirable consequences

The panel judged thromboprophylaxis harms to probably outweigh its benefits in chronically ill medical patients. Evidence certainty was considered very low. The panel members were uncertain regarding the intervention cost and cost-effectiveness and judged it to probably be neither feasible nor acceptable.

Recommendation 10:

In chronically ill medical patients the panel suggests not using over using prophylaxis for VTE (conditional recommendation, very low quality evidence).

Research priorities

Trials testing thromboprophylaxis efficacy and safety in chronically ill patients are needed.

Discussion

This clinical practice guideline provides guidance on thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical and critically ill patients in KSA. Although other thromboprophylaxis guidelines exist,12,13 it takes into consideration more recent evidence (up to December 2014), and is tailored for the Saudi context. Moreover, the Saudi recommendations are more elaborate than those of the American College of Physicians,13 but more concise than those of American College of Chest Physicians.12 Certain recommendations in this guideline are similar to those in other guidelines, but others are different. For instance, the 2011 American College of Physicians’,13 the 2012 American College of Chest Physicians’12 and the Saudi guidelines recommended pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis using a heparin for hospitalized medical patients. Additionally, the 3 guidelines recommended against GCS use in these patients. On the other hand, the Saudi guideline recommended pharmacologic prophylaxis in critically ill patients and favored LMWH over UFH, whereas the 2012 American College of Chest Physicians’ guideline only suggested LMWH or UFH thromboprophylaxis.12

The target audience of this guideline includes internists of various subspecialties and intensivists working in KSA. The guideline may benefit other healthcare professionals like public health officers and policy makers. However, clinicians, patients, third-party payers, institutional review committees, other stakeholders and courts should not view the guideline recommendations as dictating binding standards. Indeed, the recommendations do not take into consideration the specific features of individual clinical cases. The remarks following each recommendation are intended to facilitate its interpretation and be given due attention. The Saudi Expert Panel suggested local research on the values and preferences of the Saudi population regarding VTE in general, and studies on the effectiveness of the various modalities of VTE treatment and their potential side effects.

The dissemination of this guideline to healthcare providers in KSA is crucial, and the MOH has a particularly important role to achieve this goal. More crucial is the implementation of the guideline recommendations. Several interventions have been suggested and include order sets that incorporated thromboprophylaxis orders, computer alerts, and continuing medical education with or without quality assurance.33,34 Multifaceted strategies seem to be more effective than any single approach in improving VTE prophylaxis in hospitals.35-39

In conclusions, the appropriate choice of thromboprophylaxis modality should be a cornerstone in the management of hospitalized medical and critically ill patients. This evidence-based guideline provides assistance for healthcare providers working in KSA. Healthcare authorities should take the extra step of ensuring its implementation.

References

- 1.Alikhan R, Cohen AT. Heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in general medical patients (excluding stroke and myocardial infarction) [Cited 2009 July 8]. Available from URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003747.pub2/abstract;jsessionid=9E9D8115F7F5A8F8A9B34D5AB9C5511A.f01t03 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Alhazzani W, Lim W, Jaeschke RZ, Murad MH, Cade J, Cook DJ. Heparin thromboprophylaxis in medical-surgical critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2088–2098. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828cf104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amin AN, Girard F, Samama MM. Does ambulation modify venous thromboembolism risk in acutely ill medical patients? Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:955–961. doi: 10.1160/TH10-04-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arabi YM, Khedr M, Dara SI, Dhar GS, Bhat SA, Tamim HM, et al. Use of intermittent pneumatic compression and not graduated compression stockings is associated with lower incident VTE in critically ill patients: a multiple propensity scores adjusted analysis. Chest. 2013;144:152–159. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Buller HR, Haskell L, Hu D, Hull R, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:513–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch DR, Ingenito EP, Goldhaber SZ. Prevalence of deep venous thrombosis among patients in medical intensive care. JAMA. 1995;274:335–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanaan AO, Silva MA, Donovan JL, Roy T, Al-Homsi AS. Meta-analysis of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medically Ill patients. Clin Ther. 2007;29:2395–2405. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mismetti P, Laporte S, Darmon JY, Buchmuller A, Decousus H. Meta-analysis of low molecular weight heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in general surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:913–930. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collaboration CT. Effectiveness of thigh-length graduated compression stockings to reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis after stroke (CLOTS trial 1): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1958–1965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60941-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF, Goldhaber SZ, Kakkar AK, Deslandes B, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371:387–394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abo-El-Nazar Essam GS, Al-Hameed F. Venous thromboembolism-related mortality and morbidity in King Fahd General Hospital, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Ann Thorac Med. 2011;6:193–198. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.84772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, Cushman M, Dentali F, Akl EA, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e195S–e226S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qaseem A, Chou R, Humphrey LL, Starkey M, Shekelle P. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:625–632. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Hameed FM, Al-Dorzi HM, Abdelaal MA, Alaklabi A, Bakhsh E, Alomi YA, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline on Prophylaxis of VTE in Medical Patients and Long Distance Travelers. [Update 2015; Accessed 2016 July 30]. Available from URL: http://www.moh.gov.sa/endepts/Proofs/Pages/Guidelines.aspx .

- 15.Schunemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, Falavigna M, Santesso N, Mustafa R, et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ. 2014;186:E123–E142. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Saudi Center for Evidence Based Healthcare (EBHC): Clinical Practice Guidelines. [Cited 2015]. Available from URL: http://www.moh.gov.sa/endepts/Proofs/Pages/Guidelines.aspx .

- 17.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines - best practices using the GRADE framework. [Cited 2011]. Available from URL: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/publications/JCE_series.htm .

- 19.Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann H, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl E, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa R, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl E, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa R, Vandvik P, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schunemann H. GRADE Evidence to Decision frameworks: 2. Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuenemann HJ, Mustafa R, Brozek J, Santesso N, alonso-Coello P, Guyatt G, et al. Development of the GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for tests in clinical practice and public health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Feb 27; doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.032. pii: S0895-4356(16)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Guideline Development: World Health Organization. [Cited 2012]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75146/1/9789241548441_eng.pdf .

- 23.Schunemann H, Mustafa R, Brozek J, Carrasco-Labra A, Brignardello-Peterson R, Wiercioch W. Saudi Arabian Handbook for Healthcare Guideline Development. [Cited 2014]. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.sa/endepts/Proofs/Pages/GuidelineAdaptation.aspx .

- 24.Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, Ferrari A, Brandolin B, Perlati M, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2450–2457. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dentali F, Douketis JD, Gianni M, Lim W, Crowther MA. Meta-analysis: anticoagulant prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:278–288. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, Ferrari A, Brandolin B, Perlati M, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2450–2457. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishi SV, Lakshmi M, Kakde ST, Sabnis KC, Jagannati M, Girish T, et al. Randomised controlled trial for efficacy of unfractionated heparin (UFH) versus low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in thrombo-prophylaxis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61:882–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma A, Chatterjee S, Lichstein E, Mukherjee D. Extended thromboprophylaxis for medically ill patients with decreased mobility: does it improve outcomes? Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:2053–2060. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muir K, Watt A, Baxter G, Grosset D, Lees K. Randomized trial of graded compression stockings for prevention of deep vein thrombosis after acute stroke. QJM. 2000;93:359–364. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.6.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roderick P, Ferris G, Wilson K, Halls H, Jackson D, Collins R, et al. Towards evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of venous thromboembolism: systematic reviews of mechanical methods, oral anticoagulation, dextran and regional anaesthesia as thromboprophylaxis. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9:1–78. doi: 10.3310/hta9490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sud S, Mittmann N, Cook DJ, Geerts W, Chan B, Dodek P, et al. Screening and prevention of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients: a decision analysis and economic evaluation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1289–1298. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201106-1059OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson FA, Jr, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Forcier A, Patwardhan NA. Changing clinical practice. Prospective study of the impact of continuing medical education and quality assurance programs on use of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:669–677. doi: 10.1001/archinte.154.6.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Hameed F, Al-Dorzi HM, Aboelnazer E. The effect of a continuing medical education program on Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis utilization and mortality in a tertiary-care hospital. Thromb J. 2014;12:9. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scaglione L, Piobbici M, Pagano E, Ballini L, Tamponi G, Ciccone G. Implementing guidelines for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a large Italian teaching hospital: lights and shadows. Haematologica. 2005;90:678–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohn SL, Adekile A, Mahabir V. Improved use of thromboprophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis following an educational intervention. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:331–338. doi: 10.1002/jhm.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallagher M, Oliver K, Hurwitz M. Improving the use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in an Australian teaching hospital. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:408–412. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.024778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Tawfiq JA, Saadeh BM. Improving adherence to venous thromoembolism prophylaxis using multiple interventions. Ann Thorac Med. 2011;6:82–84. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.78425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tooher R, Middleton P, Pham C, Fitridge R, Rowe S, Babidge W, et al. A systematic review of strategies to improve prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospitals. Ann Surg. 2005;241:397–415. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154120.96169.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]