Abstract

Objectives

To investigate practicing physicians' preferences, perceived usefulness and understanding of a new multilayered guideline presentation format—compared to a standard format—as well as conceptual understanding of trustworthy guideline concepts.

Design

Participants attended a standardised lecture in which they were presented with a clinical scenario and randomised to view a guideline recommendation in a multilayered format or standard format after which they answered multiple-choice questions using clickers. Both groups were also presented and asked about guideline concepts.

Setting

Mandatory educational lectures in 7 non-academic and academic hospitals, and 2 settings involving primary care in Lebanon, Norway, Spain and the UK.

Participants

181 practicing physicians in internal medicine (156) and general practice (25).

Interventions

A new digitally structured, multilayered guideline presentation format and a standard narrative presentation format currently in widespread use.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Our primary outcome was preference for presentation format. Understanding, perceived usefulness and perception of absolute effects were secondary outcomes.

Results

72% (95% CI 65 to 79) of participants preferred the multilayered format and 16% (95% CI 10 to 22) preferred the standard format. A majority agreed that recommendations (multilayered 86% vs standard 91%, p value=0.31) and evidence summaries (79% vs 77%, p value=0.76) were useful in the context of the clinical scenario. 72% of participants randomised to the multilayered format vs 58% for standard formats reported correct understanding of the recommendations (p value=0.06). Most participants elected an appropriate clinical action after viewing the recommendations (98% vs 92%, p value=0.10). 82% of the participants considered absolute effect estimates in evidence summaries helpful or crucial.

Conclusions

Clinicians clearly preferred a novel multilayered presentation format to the standard format. Whether the preferred format improves decision-making and has an impact on patient important outcomes merits further investigation.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a multicentre trial targeting regular educational sessions.

Both formats were taken from published guidelines, and we used a comparator format that most participants were familiar with.

To avoid peer pressure, we ensured participants anonymity through use of clickers (audience response technology).

A weakness of the study is having researchers involved in development of the new presentation format perform most of the educational sessions.

We did not measure impact of alternative formats on clinical decisions or patient important outcomes.

Background

Clinical practice guidelines that provide recommendations addressing diagnosis and treatment can help clinicians optimise their evidence-based practice (EBP) at the point of care.1 An abundance of guidelines are available, but many have shortcomings with their trustworthiness and dissemination strategies.2 3 New standards for trustworthy guidelines developed by the Institute of Medicine and the Guideline International Network highlight the need for more rigorous development processes.4–6

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system (http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org) represents a systematic, explicit and transparent process for evaluating and reporting quality of research evidence and for moving from evidence to recommendations.7 8 GRADE facilitates the creation of trustworthy guidelines and has been adopted by more than 100 organisations worldwide.

Implementation of guidelines requires effective dissemination of recommendations.9 Guidelines should generally answer clinicians' informational needs within 2 min, which implies that recommendations need to be easy to find, understand, apply and share.10 Traditionally, guidelines have often been distributed as comprehensive PDFs, impeding efficient use at the point of care. With these challenges in mind, the GRADE working group initiated the Developing and Evaluating Communication Strategies to Support Informed Decisions and Practice Based on Evidence (DECIDE) project.11 DECIDE aimed to improve dissemination of evidence-based recommendations for a range of stakeholders, including healthcare professionals, policymakers and patients, as well as to ensure and facilitate adherence to trustworthy guideline standards.4–6

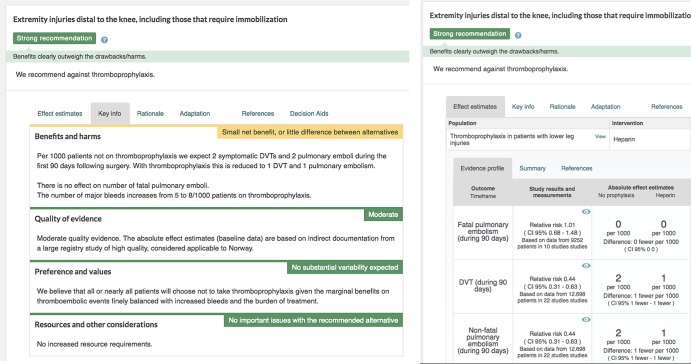

As detailed in articles by Treweek et al11 and Kristiansen et al,12 a multidisciplinary group of clinicians, guideline developers, methodologists and graphical designers developed a multilayered guideline presentation format (figure 1A, B) targeted at healthcare professionals. We hypothesised that clinicians' apparent discomfort with more complex methodological concepts could be alleviated with proper education and an optimal user interface. Based on the groups’ extensive experience from clinical practice and guideline development and informed by a narrative review of guideline formats, we designed a prototype presentation format through brainstorming sessions. This prototype format was iteratively improved based on results from stakeholder feedback and usability testing with clinicians.12

Figure 1.

(A and B) Current version of the multilayered guideline presentation formats. Thromboprophylaxis.

During usability testing we confirmed previous research demonstrating limitations in clinicians' conceptual understanding of key standards for trustworthy guidelines. We have since deployed the multilayered format in real-life guidelines.13 Uncertain of the relative merits of our novel versus existing formats we conducted a combined survey and randomised controlled trial to determine clinicians' preferences for the new multilayered presentation format versus a traditional format for guidelines, the perceived usefulness of guideline recommendations and understanding of key concepts of trustworthy guidelines.

Materials and methods

This study is the result of a collaboration of DECIDE and MAGIC (making GRADE the irresistible choice), a non-profit innovation and research programme (http://www.magicproject.org), which aims at facilitating the efficient creation, dissemination and dynamic updating of trustworthy guidelines and evidence summaries. As previously reported, MAGIC has created a web-based guideline authoring and publication platform (http://www.magicapp.org), incorporating the digitally structured multilayered presentation format used in this study.14 Through DECIDE these novel formats have also been incorporated in GRADEpro (http://gradepro.org/). Organisations can use these platforms or freely adopt research outputs from the DECIDE project, including but not limited to the multilayered presentation format, into their own workflow, tools or platforms.

Study design, setting and participants

We applied a combined survey and randomised controlled trial. We included practicing physicians in internal or family medicine. In order to recruit representative samples of internal medicine physicians, investigators targeted compulsory educational sessions at teaching hospitals. Two facilities recruited general practitioners in family medicine. One by targeting a compulsory educational session at a larger family practice centre (Spain), the other by inviting individual physicians, including general practitioners, to a specific CLICK-IT study session (NICE, UK). All participants attended a standardised educational session on key guideline standards performed within the context of this study. We performed four pilot sessions and made revisions to the survey questions based on experiences in these sessions. The revisions were minor and concerned mainly phrasing of the questions asked. Our reported primary and secondary outcomes are in accordance with the original study protocol.

Participants were considered to provide consent by accepting to answer the survey questions.

Standardised lecture and study procedure

At each site, a member of the research team delivered a standardised lecture according to a predefined protocol. The lecture was titled ‘New standards for trustworthy guidelines’ (see online supplementary appendix 1) and was given in power point on a standard projector screen. Participants provided anonymous answers to questions with predefined response categories using clickers. The questions (both for the survey and the randomised part of the trial)—as well as screenshots of presentation formats—were embedded in the lecture slides using an audience response software, TurningPoint, and read out loud by the presenter. For the Norwegian and Spanish sites we translated the presentation to their native language; while in Lebanon and the UK the questions were presented in English, which is commonly used in medical education.

bmjopen-2016-011569supp_appendix.pdf (4.2MB, pdf)

The lecture and study procedure were developed by the investigators and included the following components:

Collection of the demographics of the participants, their current preference for information resources and understanding of the GRADE system.

Presentation of a clinical scenario concerning choice of oral anticoagulation in a patient with atrial fibrillation and high risk of stroke (CHA2DS2-VASc score 2).

Presentation of guideline recommendations and evidence summaries relevant to the clinical scenario, sequentially presented in the two alternative guideline presentation formats through randomisation and blinding as outlined below. Both formats were shown side by side to both groups at the end.

Short presentation of key conceptual definitions of trustworthy guidelines, specifically explanation of the strength of recommendations and quality of the evidence using the GRADE methodology.

Guideline presentation formats

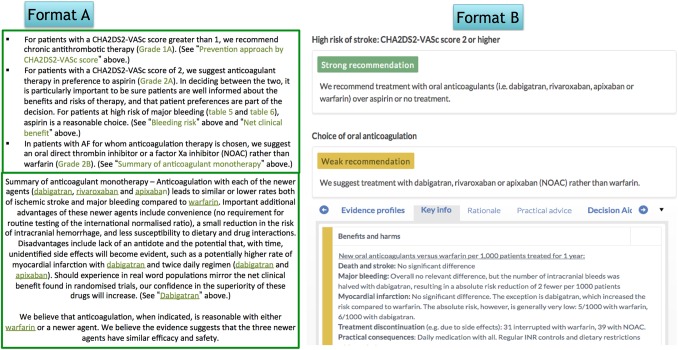

Figure 2 shows the standard narrative guideline presentation format (format A) and the new multilayered guideline presentation format (format B). We extracted both formats from existing guidelines, but masked the publishers' identity to avoid potentially biasing participants' responses. Both formats were displayed as screenshots in the presentation slides.

Figure 2.

Standard and multilayered guideline presentation formats. NOAC, novel oral anticoagulant.

Multilayered format: The experimental multilayered format displays recommendations upfront with supporting information as collapsible boxes provided by clicking on the recommendation itself. The strength of the recommendation is communicated by use of text and colour coding, and a header describes the population for which the recommendation applies. The example was taken from a Norwegian guideline for antithrombotic therapy applying the multilayered presentation formats published in MAGICapp and translated to English for the purpose of this study.13 15

Standard format: The control standard format displays recommendations and an abridged evidence summary from UpToDate.16 We considered UpToDate's presentations a suitable reference standard for current presentation formats due to its widespread use, commonality with other guidelines, evidence-based approach and use of GRADE.17 18 UpToDate provides a textual summary of its recommendations in bullet points with links to the supporting information in the main text or in other articles. The recommendations are labelled with numbers (1 & 2) and letters (A–C), depicting the strength of the recommendation and quality of evidence respectively.

Randomisation and blinding

A research member colour marked the base of half the clickers and haphazardly rearranged them in their container. The presenter handed out the clickers to the participants, randomly and with the front-side up, thus concealing the allocation marking for both presenter and participant. The participants were not informed that the marking was part of the group allocation until the survey part of the lecture was completed, and they had no opportunity to swap clickers during the lecture. Participants with marked clickers were randomised to group B, being presented the multilayered format. We asked participants in either group to put on blindfolds while participants in the other group were shown their allocated presentation format and answered questions. Questions during randomisation were not read out loud, only the group not wearing blindfolds at the time answered the questions. The presenters watched while the participants put on blindfolds, making sure they adhered to their allocated group.

Outcome measures

Our primary outcome was preference for either presentation format. We provided three response options: preference for the standard format, no preference and preference for the multilayered format.

Secondary outcomes included:

Correct understanding/interpretation of (1) the evidence summaries and (2) the recommendation with four potential answers, one alternative being correct.

Anticipated course of action to the clinical scenario with four potential answers, two alternatives being correct.

Participants' perceived usefulness of (1) evidence summaries and (2) recommendations. Participants provided answers to the statement ‘This information/recommendation would help me manage my patient’ on a six-point Likert scale: 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=somewhat disagree, 4=somewhat agree, 5=agree and 6=strongly agree.

Correct understanding of the strength of the following example recommendation and the confidence in effect estimates: ‘We suggest that older patients receive supplementation with vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) GRADE 2B’. We provided participants with four potential answers, one alternative being correct.

Perceived understanding of the strength of the recommendation. We asked the participants the following question twice, before and after being provided with a short written explanation: ‘I fully understand the difference between strong and weak recommendations and the implications for clinical decision-making’. They provided answers on a six-point Likert scale with two anchors: 1=strongly disagree and 6=strongly agree.

Participants' perception of presenting absolute effect estimates. We asked participants ‘What is your first reaction to being presented with absolute effects?’ The answers were collected using a five-point scale: 1=confusing distraction, leave it out, 2=a little confusing, but not a big problem, 3=does not help, but does not hurt, 4=not crucial, but helpful and 5=crucial information, should always be included.

Statistical analysis

We dichotomised all outcomes to either correct/incorrect or agree/disagree, and analysed them by using Pearson's χ2 test. We included all randomised participants who answered more than one question in the final analysis (intention to treat). No subgroup analyses were specified in the protocol. The accompanying data set (Excel and original TurningPoint data files from each centre) provides results subdivided per type of physician and centre. We used SPSS (V.23) for all analyses.

Results

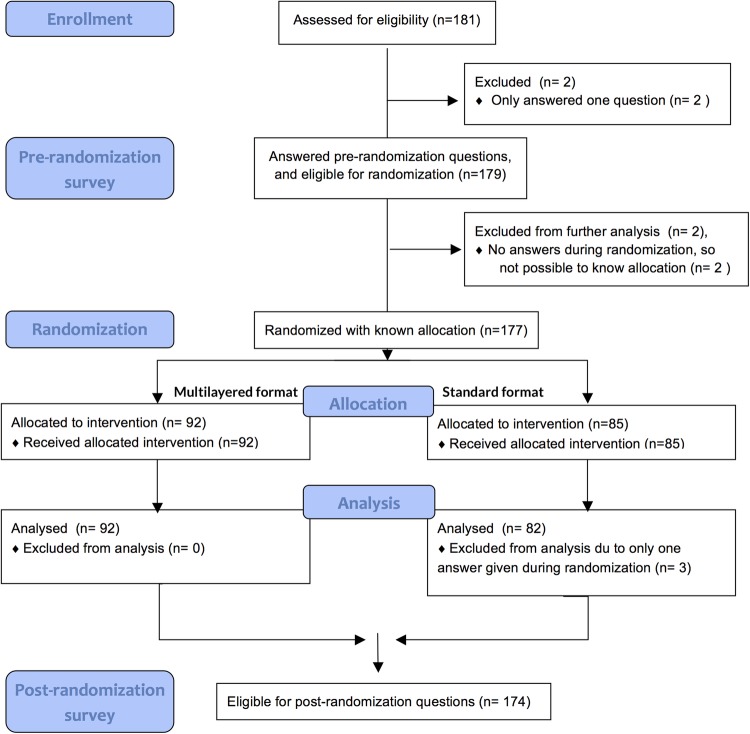

We performed the study from June 2013 to January 2015. We included 181 practicing physicians across four countries and nine centres (Lebanon 1, Norway 6, Spain 1 and UK 1), 177 were randomised and 174 (96%) answered >1 question and are included in the final analysis (figure 3). Their demographics and information resource preferences are provided in table 1. The two groups were fairly similar. One centre (27 participants) in Norway did not include demographic questions, so the demographic presentation includes the remaining eight centres.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of design and enrolment of participants to the multilayered format (n=92) and standard format (n=85).

Table 1.

Demographics of the groups randomised to different formats

| Number of participants randomised | Multilayered format 92 |

Standard format 85 |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| (number of participants eligible for analysis) | (92) | (83) |

| Norway (%) | 61 (66.3%) | 57 (68.7%) |

| UK (%) | 10 (10.9%) | 10 (12%) |

| Lebanon (%) | 11 (12.0%) | 10 (13.3%) |

| Spain (%) | 10 (10.9%) | 5 (6%) |

| Professional status or specialty | ||

| (number of participants eligible for analysis) | (76) | (72) |

| Medical student or intern (%) | 13 (17.1%) | 8 (11.1%) |

| Internist resident (%) | 21 (27.6%) | 27 (37.5%) |

| Internist attending/consultant (%) | 23 (30.3%) | 21 (29.2) |

| General practitioner (%) | 13 (17.1%) | 12 (16.7%) |

| Unknown (% did not answer that question) | 6 (7.9%) | 4 (5.6%) |

| Training in health research methodology | ||

| (number of participants eligible for analysis) | (72) | (68) |

| No training in HRM (%) | 34 (47.2%) | 35 (51.2%) |

| ≥1 HRM course (%) | 26 (36.1%) | 21 (30.9%) |

| Degree in HRM (%) | 12 (16.7%) | 12 (17.6) |

| Preferred knowledge source | ||

| (number of participants eligible for analysis) | (89) | (82) |

| Local guideline (%) | 22 (24.7%) | 14 (17.1%) |

| Systematic review (%) | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (2.4%) |

| EBM textbook (%) | 17 (19.1%) | 13 (15.9%) |

| National or international guideline (%) | 34 (38.2%) | 36 (43.9%) |

| Colleague (%) | 14 (15.7%) | 17 (20.7%) |

| Primary study (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

EBM, evidence-based medicine; HRM, health research methodology.

Preference for alternative presentation formats

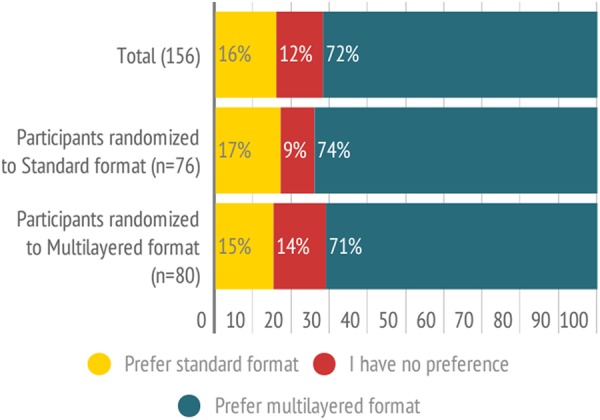

When exposed to both formats after completing the randomised part of the study 113 of 156 (72%, 95% CI 65 to 79) participants preferred the new multilayered format, 25 (16%, 95% CI 10 to 22) preferred the standard format, and 18 (12%, 95% CI 7 to 17) reported no preference. Results were similar in those randomised to the standard versus the multilayered format (p=0.66, figure 4).

Figure 4.

Preferences for standard format versus multilayered presentation format.

Understanding and anticipated clinical action

Sixty-nine of 78 participants (88%, 95% CI 81 to 96) randomised to the standard format, and 57 of 64 participants (89%, 95% CI 82 to 97) randomised to the multilayered format correctly understood the evidence summaries, with no difference between groups (p value=0.91). A majority correctly understood the recommendations, with no statistically significant difference between the standard format (44/ 76, 58%) and the multilayered format (55/ 76, 72%) (p value=0.06).

Most participants correctly stated they would consider an oral anticoagulant as an appropriate course of treatment, with a majority preferring direct acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) rather than warfarin. We observed no statistically significant difference between the presentation formats (standard format 66/72 (92%, 95% CI 85 to 98) versus the multilayered format 79/81 (98%, 95% CI 94 to 100), p value=0.10).

Perceived usefulness of evidence summaries and recommendations

Of the 69 participants in the standard format group, 53 (77%, 95% CI 67 to 87) agreed (somewhat agree, agree or strongly agree) that the background evidence summaries were helpful in the context of the clinical scenario, as did 60 of 76 participants in the multilayered format group (79%, 95% CI 70 to 88), with no difference between the randomised groups (p value=0.76). Seventy-two of 79 participants (91%, 95% CI 85 to 97) randomised to the standard format and 74 of 86 participants (86%, 95% CI 79 to 93) to the multilayered format agreed that the recommendations were helpful in the context of the clinical scenario (p value=0.31). When specifically asked, 84 of 102 (82%, 95% CI 75 to 90) participants considered absolute effect estimates provided in the multilayered format evidence summaries helpful or crucial.

Survey on conceptual understanding

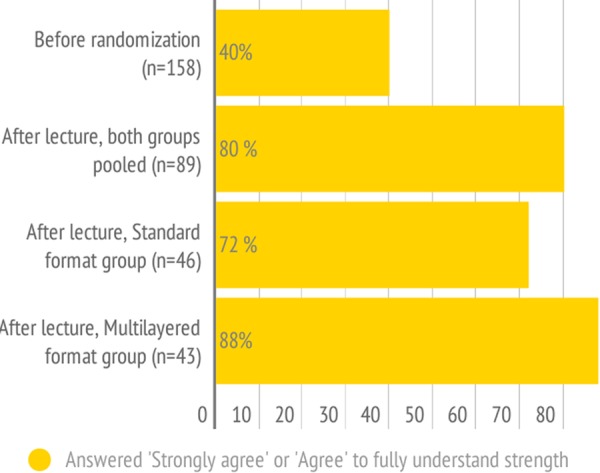

Prior to randomisation, we provided the participants with a recommendation labelled ‘2B’ and asked them what the number 2 and the letter B meant. Few participants answered correctly that this represented a weak (2) recommendation based on moderate (B) quality evidence (20/154 (13%, 95% CI 8 to 18) stated weak, while 61/144 (42%, 95% CI 34 to 50) stated moderate). We furthermore asked twice to what extent they agreed to the following statement: ‘I fully understand the difference between strong and weak recommendations and the implications for clinical decision making’. Prior to randomisation 63 of 158 participants (40%, 95% CI 32 to 48, figure 5) stated that they agreed (or strongly agreed) to this statement. After randomisation, we provided the participants with a one slide explanation of the strength of the recommendation according to the GRADE system, defining the difference between strong and weak recommendations and posed the same question again. Seventy-one of 89 participants (80%, 95% CI 70 to 88, figure 5) agreed with the statement. There was a borderline significant difference between participants according to randomised format (standard format 72% vs multilayered format 88%, p=0.051, figure 5).

Figure 5.

Reported answers to the statement: ‘I fully understand the difference between strong and weak recommendations and the implications for clinical decision-making’.

Discussion

In this study of practicing physicians, we demonstrated a clear preference for the new guideline multilayered presentation format rather than a traditional narrative format, with a majority agreeing that recommendations and underlying evidence summaries—regardless of presentation format—were useful in the context of the clinical scenario. A majority of the physicians (82%) also reported absolute effect estimates provided in the multilayered format evidence summaries to be helpful or crucial for decision-making. Conceptual understanding of the strength of recommendations and quality of evidence was limited when expressed through numbers and letters—as carried out in the standard format example from UpToDate. A short explanation of these concepts according to the GRADE system substantially increased reported understanding.

Strengths and weaknesses

We enlisted a substantial and diverse set of practising physicians across six different countries, targeting mandatory educational sessions, making our participant sample representative of the everyday clinician and our results generalisable. We mapped understanding of both key methodological concepts and preference for entire guideline formats, as opposed to single elements. We devised a clinical scenario with a highly prevalent disease (atrial fibrillation), in which there have been recent treatment innovations (DOACs), possibly not commonly known to all physicians when this study was conducted. Through this manoeuvre, we limited the possible bias of previous knowledge on the participants' performance. We targeted internists and family physicians as participants given their familiarity with atrial fibrillation.

There are limitations to the chosen study design. First, devising multiple-choice questions that accurately test key outcomes such as understanding is challenging. Our approaches, including subjectively perceived understanding and anticipated clinical action are less satisfactory than detailed testing of understanding. Actual understanding may be less than what our results suggest, and the correct clinical choice of action may have been highly influenced by previous knowledge on the subject. A substantial proportion of physicians reported to ‘somewhat agree’ rather than agree or strongly agree with statements concerning usefulness of recommendations and evidence summaries in clinical practice guidelines. This finding highlights some limitations of our study related to using a hypothetical scenario—rather than assessing real life decision-making—and the challenge of phrasing questions and devising appropriate response categories within this field of research. Finally, as we have only tested one specific clinical scenario on a limited representation of healthcare professionals, the transferability of our findings to other settings and professional groups needs further validation.

Implications for practice and research

The finding that the majority of clinicians preferred to be informed about the absolute effects on patient-important outcomes in evidence summaries is encouraging, as numeracy among healthcare professionals is highly variable and many guidelines omit contextualised effect estimates necessary for shared decision-making.19–21 GRADE Summary of findings tables—as displayed in the multilayered guideline formats—have emerged as user-friendly and well accepted formats in the context of systematic reviews, with recent advances in formatting resulting in further increasing understanding.22 23

About 40% of the participants stated that they fully understood the difference between strong and weak recommendations, but only 13% could correctly recognise a weak recommendation applying the commonly used numbered labelling (1=strong, 2=weak). However, when given recommendation and evidence summary linked to a clinical scenario 95% of participants would treat according to current guidelines. There are thus two reasons for optimism: Most participants correctly interpreted the intent and meaning of the recommendations when communicated within a larger context. Furthermore, perceived understanding improved after being presented a one slide explanation on the meaning of key concepts.

We did not explore in detail why participants preferred the new DECIDE multilayered format. However, informed by feedback throughout the design process from stakeholders as well as informal discussions following the survey, clinicians seem to appreciate short and clear advice, provision of strength that is easy to interpret and details on the key factors that drove the recommendations, which is provided within the multilayered format.

Optimised guideline presentation formats and sufficient conceptual understanding can potentially facilitate the uptake of trustworthy guidelines and application of research evidence in practice.24 25 The multilayered format serves several purposes: It is devised around the GRADE framework and thus directs guideline authors through the appropriate methodological steps. It provides end-user clinicians with actionable, graded recommendations, as advocated by the Institute of Medicine.26 Finally, having the guideline digitally structured facilitates easy translation into several outputs; such as decision aids, clinical decision support systems within the electronic medical record, tablets, smartphones, online and as PDFs. It also facilitates continuous updating and adaptation to local settings,14 thereby minimising the workload for guideline developers and policymakers.

Further research into different ways of communicating key guideline concepts to healthcare professionals to improve understanding and adoption is still necessary. The multilayered guideline presentation formats are currently implemented in a handful of published guidelines from a variety of organisations, and more are under development. We are continuously performing usability testing, both with authors and end-users, informing further improvements.

Conclusion

Clinicians prefer a novel multilayered presentation format to the standard format. Optimised guideline presentation formats and sufficient conceptual understanding can potentially facilitate the uptake of trustworthy guidelines and application of research evidence in practice. Whether the preferred format improves decision-making and has an impact on patient-important outcomes merits further investigation.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Rob Fracisco, Frankie Achille and Sarah Rosenbaum.

Contributors: LB, POV, EAA, DR, KA and POC collected the data. LB, POV and AK had access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. LB was principal investigator on the study. LB, AK, POV, PA-C and AE contributed to the conception, design, and ethical approval of the study. LB, POV and AK contributed to writing the first draft of the article; and LB, POV, PA-C, EA, JT, DR, KA, POC, GG and AK contributed to editing and approval of the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Sykehuset Innlandet Hospital Trust under grant number 150194 (PLUGGED IN), The Research Council of Norway (VERDIKT) under grant 193022 (EVICARE) and European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement number 258583 (DECIDE project).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form. LB, AK, GG and POV are members of a non-profit research and innovation project MAGIC: http://www.magicproject.org, which has an open technical platform where the new DECIDE multilayered formats were prototyped. All authors were either co-investigators or collaborators of the DECIDE project. LB, AK, GG, POV, PA-C, EA, JT and DR are members of the Grade Working group. The strategy evaluated in the study is based on the GRADE approach. No other competing interests were declared.

Ethics approval: Research ethics boards in each participating country: Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the American University of Beirut (Lebanon), Ethics committee and R&D at NICE (UK), Ethics committee of the Hospital Sant Pau (Spain), Regional Ethical Committee South East (Norway).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.2qv30.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Rob Fracisco, Frankie Achille, and Sarah Rosenbaum

References

- 1.Bahtsevani C, Udén G, Willman A. Outcomes of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Healthcare 2004;20:427–33. 10.1017/S026646230400131X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kung J, Miller RR, Mackowiak PA. Failure of clinical practice guidelines to meet institute of medicine standards: two more decades of little, if any, progress. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1628–33. 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I et al. . The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Healthcare 2010;19:e58 10.1136/qshc.2010.042077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM. Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F et al. . Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:525–31. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laine C, Taichman DB, Mulrow C. Trustworthy clinical guidelines. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:774–5. 10.7326/0003-4819-154-11-201106070-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldet G, Howick J. Understanding GRADE: an introduction. J Evid Based Med 2013;6:50–4. 10.1111/jebm.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB et al. . Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006;26:13–24. 10.1002/chp.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence Based Medicine Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ 2014;348:g3725 10.1136/bmj.g3725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treweek S, Oxman AD, Alderson P et al. . Developing and Evaluating Communication Strategies to Support Informed Decisions and Practice Based on Evidence (DECIDE): protocol and preliminary results. Implement Sci 2013;8:6 10.1186/1748-5908-8-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristiansen A, Brandt L, Alonso-Coello P et al. . Development of a novel, multilayered presentation format for clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2015;147:754–63. 10.1378/chest.14-1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristiansen A, Brandt L, Agoritsas T et al. . Applying new strategies for the national adaptation, updating and dissemination of trustworthy guidelines: results from the Norwegian adaptation of the American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-based Guidelines. Chest 2014;146:735–61. 10.1378/chest.13-2993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandvik PO, Brandt L, Alonso-Coello P et al. . Creating clinical practice guidelines we can trust, use, and share: a new era is imminent. Chest 2013;144:381–9. 10.1378/chest.13-0746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.http://www.nsth.no. (accessed Feb 2016).

- 16. 2013 AJ. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/atrial-fibrillation-anticoagulant-therapy-to-prevent-embolization?source=machineLearning&search=atrial+fibrillation+anticoagulation&selectedTitle=1~150§ionRank=1&anchor=H31#H31.

- 17.Isaac T, Zheng J, Jha A. Use of UpToDate and outcomes in US hospitals. J Hosp Med 2012;7:85–90. 10.1002/jhm.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwag KH, González-Lorenzo M, Banzi R et al. . Providing doctors with high-quality information: an updated evaluation of web-based point-of-care information summaries. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e15 10.2196/jmir.5234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manrai AK, Bhatia G, Strymish J et al. . Medicine's uncomfortable relationship with math: calculating positive predictive value. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:991–3. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston B, Alonso-Coello P, Friedrich JO et al. . Do clinicians understand the size of treatment effects? A randomized survey across 8 countries. CMAJ 2016;188:25–32. 10.1503/cmaj.150430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agoritsas T, Heen AF, Brandt L et al. . Decision aids that really promote shared decision-making: the pace quickens. BMJ 2015;350:g7624 10.1136/bmj.g7624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum SE, Glenton C, Oxman AD. Summary-of-findings tables in Cochrane reviews improved understanding and rapid retrieval of key information. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:620–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrasco-Labra A, Brignardello-Petersen R, Santesso N et al. . Improving GRADE evidence tables part 1: a randomized trial shows improved understanding of content in Summary-of-Findings Tables with a new format. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;74: 7–18. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Hsiao J, Chen R. Critical factors influencing physicians intention to use computerized clinical practice guidelines: an integrative model of activity theory and the technology acceptance model. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuello García CA, Pacheco Alvarado KP, Pérez Gaxiola G. Grading recommendations in clinical practice guidelines: randomised experimental evaluation of four different systems. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:723–8. 10.1136/adc.2010.199307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA et al. . A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;72:45–55. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011569supp_appendix.pdf (4.2MB, pdf)