Abstract

Background

Serine protease inhibitors (SPIs) have been found in all living organisms and play significant roles in digestion, development and innate immunity. In this study, we present a genome-wide identification and expression profiling of SPI genes in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.), a major pest of cruciferous crops with global distribution and broad resistance to different types of insecticides.

Results

A total of 61 potential SPI genes were identified in the P. xylostella genome, and these SPIs were classified into serpins, canonical inhibitors, and alpha-2-macroglobulins based on their modes of action. Sequence alignments showed that amino acid residues in the hinge region of known inhibitory serpins from other insect species were conserved in most P. xylostella serpins, suggesting that these P. xylostella serpins may be functionally active. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that P. xylostella inhibitory serpins were clustered with known inhibitory serpins from six other insect species. More interestingly, nine serpins were highly similar to the orthologues in Manduca sexta which have been demonstrated to participate in regulating the prophenoloxidase activation cascade, an important innate immune response in insects. Of the 61 P.xylostella SPI genes, 33 were canonical SPIs containing seven types of inhibitor domains, including Kunitz, Kazal, TIL, amfpi, Antistasin, WAP and Pacifastin. Moreover, some SPIs contained additional non-inhibitor domains, including spondin_N, reeler, and other modules, which may be involved in protein-protein interactions. Gene expression profiling showed gene-differential, stage- and sex-specific expression patterns of SPIs, suggesting that SPIs may be involved in multiple physiological processes in P. xylostella.

Conclusions

This is the most comprehensive investigation so far on SPI genes in P. xylostella. The characterized features and expression patterns of P. xylostella SPIs indicate that the SPI family genes may be involved in innate immunity of this species. Our findings provide valuable information for uncovering further biological roles of SPI genes in P. xylostella.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3583-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Serpin, Canonical inhibitor, Expression pattern, Phylogenetic analysis, Lepidoptera

Background

Serine proteases are ubiquitous enzymes in almost all organisms, from bacteria to mammals [1], and they are known to play significant roles in a wide range of biological processes [2–5]. Besides their crucial physiological roles, proteases carry out an unlimited number of hydrolytic reactions to break down proteins [6], and such proteolytic activity can be potentially hazardous in living systems. Consequently, protease activity must be strictly and precisely controlled [7–9]. There are several distinct mechanisms for the regulation of excessive activity of proteases. The most effective and direct mechanism is to inactivate proteases by protease inhibitors [7, 8]. Serine protease inhibitors (SPIs) have been widely studied with documented roles in digestion, metamorphosis and development, as well as in immune responses [10–16]. SPIs can be divided into three distinct types: serpins, canonical inhibitors, and non-canonical inhibitors, based on their mechanisms of action [7, 9]. Interaction between a serpin and its target protease is similar to substrate binding, and cleavage of a single peptide bond in the binding loop results in conformational change of serpin [17–19]. The canonical inhibitors bind to the enzymes by an exposed convex binding loop, docking to the active site of the proteases that leads to inactivation of proteases [7, 9]. The non-canonical inhibitors interact with target proteases through their N-terminal segments, which are secondary interactions outside the active site to significantly enhance the affinity, velocity and specificity of recognition [7, 9].

Serpins are found in nearly all organisms, and are a superfamily of proteins with three β-sheets and seven to nine α-helices folding into a conserved tertiary structure with a reactive center loop (RCL) [19]. The RCL is located in the carboxyl terminus, and exposed at the surface of a serpin, acting as a ‘bait’ for target proteases [20, 21]. After proteases cleave the RCL at the scissile bond, serpins undergo conformational change, resulting in inactivation of target proteases [15]. Previous studies have illustrated that most serpins are inhibitors of serine proteases [15, 20, 21], while some serpins become inhibitors of caspases [22] and papain-like cysteine proteases [23, 24]. Meanwhile, some other serpins are non-inhibitors, achieving a number of other biological tasks, such as tumor suppressors, hormone transporters and molecular chaperones [25–27].

In contrast to serpins, canonical inhibitors are the largest group of protein inhibitors and they are usually small proteins with 14 ~ 200 amino acids (aa) [7]. Canonical inhibitors can be classified into different families based on sequence homology, position of active center and disulfide bond, including Kazal, Kunitz and Antistasin families [7, 9]. Alpha-2-macroglobulin (α2M) is a large protein belonging to the thiol ester superfamily [28], which is known for its ability to inhibit a broad spectrum of proteases, including serine proteases, papain, aspartic proteases and metalloproteases [29, 30]. The inhibitory mechanism of α2M is to physically enfold target proteases by a macromolecular cage, forming a complex of α2M-protease to prevent protease from accessing protein substrates [31, 32].

Whole-genome investigations on the serpin family have been carried out in a number of insect species, including Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) [20, 33], 12 Drosophila species (Diptera: Drosophilidae) [34], Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) [3], Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) [35], and Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) [36]. Seven Manduca sexta (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) serpins have been characterized through biochemical studies [13, 37–42]. Previous studies reveal that most serpins function as serine protease inhibitors and play significant roles in regulation of innate immunity by controlling proteolytic pathways. The genome-wide analysis of canonical inhibitors has been performed in B. mori [43], and some individual canonical inhibitors have been characterized in other insect species. For example, two Kunitz-type inhibitors from the hemolymph of M. sexta functioned as inhibitors of serine proteases, including trypsin, chymotrypsin and plasmin [44]. A Kazal-type inhibitor in the midgut of Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) may be involved in the interaction between microbiota and Trypanosoma cruzi [45]; two non-classical Kazal-type serine proteinase inhibitors (PpKzl1 and PpKzl2) were identified in Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae), and PpKzl2 has been described as an active serine proteinase inhibitor that is possibly involved in regulating digestive enzymes in the midgut [10]. However, only three P. xylostella SPIs (serpins 2, 4 and 5) have been reported. By proteomic profiling and cloning, it has been shown that the expression of P. xylostella serpin 2 gene was reduced to 50% of the control during early parasitism (Cotesia plutellae) [46]; and its expression was also significantly affected by destruxin A (the mycotoxin produced by Metarhizium anisopliae) [47]. Knockdown of serpins 2, 4 and 5 by RNAi can induce expression of cecropins, increase phenoloxidase (PO) activity and body melanization in larvae, as well as mortality of P. xylostella larvae [48].

In this study, P. xylostella SPIs were identified and characterized based on the P. xylostella genome [49]. Our findings provide a foundation for further studies on the biological functions of SPIs in P. xylostella, which may be used in the development of genomic strategies for pest management.

Results

Identification of P. xylostella SPIs

Amino acid sequences of SPIs from B. mori, M. sexta (Lepidoptera), D . melanogaster, A. gambiae (Diptera), T. castaneum (Coleoptera) and A. mellifera (Hymenoptea) were used to search P. xylostella genomic sequences. A total of 61 putative SPI genes were identified in P. xylostella (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1), and the deduced amino acid sequences were provided in Additional file 1: Table S2. The 61 putative SPI genes were classified into three types: serpins, canonical SPIs, and α2Ms (Table 1) based on their mechanisms of action.

Table 1.

Serine protease inhibitor (SPI) domains in Plutella xylostella

| Name | SPI domain | Number of the SPI domains | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| PxSPI1 ~ PxSPI25 | Serpin | 1 | serpin |

| PxSPI26 | TIL | 13 | canonical SPIs |

| PxSPI27 | TIL | 6 | |

| PxSPI28 | TIL | 17 | |

| PxSPI29 | TIL | 3 | |

| PxSPI30 | TIL | 4 | |

| PxSPI31 ~ PxSPI33 | TIL | 3 | |

| PxSPI34 | TIL | 1 | |

| PxSPI35 | Kunitz | 1 | |

| PxSPI36 ~ PxSPI37 | Kunitz | 2 | |

| PxSPI38 | Kunitz | 3 | |

| PxSPI39 | Kunitz | 2 | |

| PxSPI40 ~ PxSPI41 | Kunitz | 1 | |

| PxSPI42 | Kunitz/WAP | 10/1 | |

| PxSPI43 | WAP | 1 | |

| PxSPI44 | WAP/Antistasin/Kunizt | 3/2/1 | |

| PxSPI45 | Kazal | 4 | |

| PxSPI46 | Kazal | 6 | |

| PxSPI47 | Kazal | 1 | |

| PxSPI48 | Kazal | 4 | |

| PxSPI49 ~ PxSPI50 | Kazal | 1 | |

| PxSPI51 | Kazal | 3 | |

| PxSPI52 | Kazal | 5 | |

| PxSPI53 | Kazal | 1 | |

| PxSPI54 | Kazal | 3 | |

| PxSPI55 | Kazal | 2 | |

| PxSPI56 | Kazal | 1 | |

| PxSPI57 | amfpi | 1 | |

| PxSPI58 | Pacifastin | 4 | |

| PxSPI59 ~ PxSPI61 | α2-macroglobulin | 1 | α2-macroglobulin |

Serpins

In this study, 25 serpins were identified in P. xylostella and named PxSPI1-PxSPI25. This number is fewer than 34 serpins in B. mori [21], 31 in T. castaneum [35] and 29 in D. melanogaster [15], but greater than 18 serpins in A. gambiae [20] and seven in A. mellifera [3]. The 25 serpin genes were spread across 16 different scaffolds (Additional file 1: Table S1). Of the 25 serpins, 14 were grouped in five clusters, forming three 2-gene clusters on scaffold 17, 160 and 879 and two 4-gene clusters on scaffold 69 and 258 (Fig. 1). Eleven of the 25 serpins were predicted to be secreted proteins based on the putative secretion signal peptides; 11 lacked putative signal peptides and were predicted to be intracellular proteins; whereas two (PxSPI10 and PxSPI20) were incomplete at the amino-terminus, one (PxSPI25) was incomplete at the carboxyl terminus (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Scaffold localization of the serpin genes in P. xylostella. Gene names and the distance of two adjacent genes (kilobases, kb) are shown on the right and left of the bar, respectively. Scaffold numbers are indicated on the top of each bar

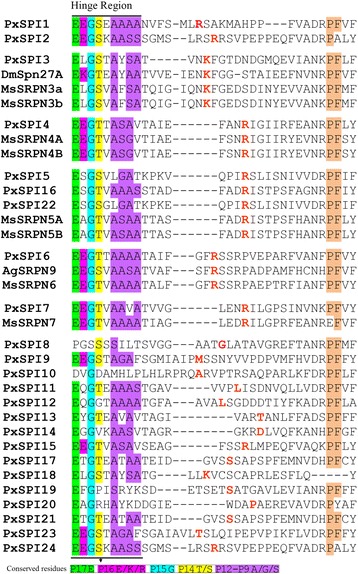

Serpins are metastable proteins that experience conformational changes as they inhibit proteases [19]. Several structural regions (the hinge, breach, shutter and gate regions) are necessary for conformational changes of serpins. The hinge is an essential region where the peptide chain bends to permit RCL insertion, and the breach and shutter regions must open to allow RCL insertion [50, 51]. A region known as the gate, which participates in a structural transition (latency) during RCL insertion, occurs in the absence of RCL cleavage [52]. To investigate the important structural regions of P. xylostella serpins, we aligned P. xylostella serpins with known inhibitory serpins from M. sexta (MsSRPN3-7), D. melanogaster (DmSpn27A) and A. gambiae (AgSRPN9). The result revealed that most residues in these structural regions (the breach, shutter and gate) in known inhibitory serpins, were conserved in most P. xylostella serpins (Additional file 2: Figure S1). The alignment also showed that most residues in the hinge region in the known inhibitory serpins were conserved in most P. xylostella serpins, except for PxSPI8, PxSPI10, PxSPI19, PxSPI20 and PxSPI25 (PxSPI25 was incomplete at the carboxyl terminus) (Fig. 2). It has been documented that serpins may inhibit trypsin-like enzymes with either an Arg (R) or Lys (K) residue at the P1 position, inhibit chymotrypsin-like enzymes with P1 residue of Phe (F), Tyr (Y), Leu (L) or Ile (I), and inhibit elastase-like enzymes with P1 residue of Ala (A) or Val (V) [21, 53]. Meanwhile, prediction of the proteolytic cleavage site of serpins showed that PxSPI1-7, 15, 16, 18, 22 and 24 had an R or K residue at the P1 position, indicating that they may inhibit trypsin-like enzymes, whereas PxSPI11 and PxSPI12 containing Leu (L) at the P1 position may inhibit chymotrypsin-like enzymes, and PxSPI10 with Ala at the P1 position may inhibit elastase-like enzymes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of the hinge and reactive center loop regions of P. xylostella serpins. The hinge and RCL regions of P. xylostella serpins were aligned with those of serpins with known functions from D. melanogaster (Dm), M. sexta (Ms) and A. gambiae (Ag) by ClustalX 2.0 program with default parameters. Predicted P1 residues are highlighted in red. P. xylostella serpins are presented in numerical order and grouped with homologous serpins from other species as determined by phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3)

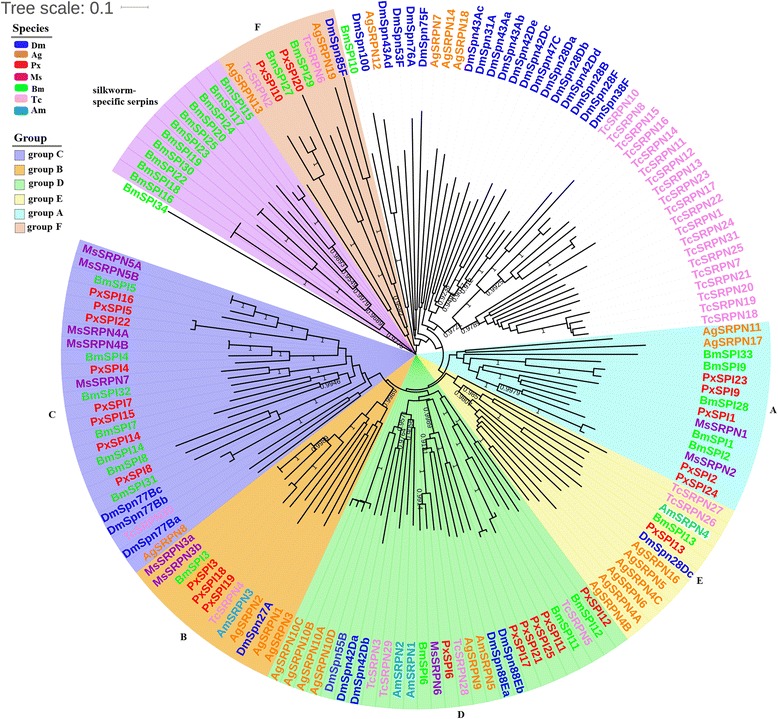

Phylogenetic analysis of P. xylostella serpins with those from two other Lepidoptera species (B. mori and M. sexta), two Diptera species (D. melanogaster and A. gambiae), a Coleopteran species (T. castaneum) and a Hymenoptera species (A. mellifera) showed that P. xylostella serpins were divided into six distinct phylogenetic groups (groups A-F). Although distributed to different branches, P. xylostella serpins clustered with those of two Lepidoptera species (Fig. 3), indicating that the serpin family is highly conserved in Lepidoptera. However, P. xylostella serpins were not grouped with silkworm-specific serpins originally defined as group F that are arisen from recent gene duplications [21]. Except for silkworm-specific serpins, P. xylostella serpins were clustered with M. sexta serpins and the remaining B. mori serpins. For example, five P. xylostella serpins were clustered with two M. sexta and three B. mori serpins in group A. PxSPI1 was clustered with MsSRPN1J and BmSPI1, PxSPI2 and PxSPI24 were clustered with BmSPI2 and MsSRPN2, and so were PxSPI9 and PxSPI23 with BmSPI9. It has been shown that MsSRPN1J (MsSRPN1 splicing isoform J) is an inhibitor of prophenoloxidase (proPO) activating protease 3 (PAP3) in M. sexta [54]. Multiple sequence alignments of PxSPI1, MsSRPN1J and BmSPI1 showed that the three serpins had a high level of sequence identity (65.7%) and shared the identical amino acid residues at P1 position and hinge region (Additional file 2: Figure S2A), suggesting that PxSPI1 may function as an inhibitor of PAP in P. xylostella proPO activation system. In M. sexta, MsSRPN2 has been reported as an intracellular serpin, and its expression increases dramatically after larvae are injected with bacteria [38]. PxSPI2 lacked putative secretion signal peptide and was predicted to be an intracellular protein.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship of serpins from P. xylostella and six other insect species. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 6.06 with neighbor joining approach on the basis of Poisson model and pairwise deletion of gaps. The bootstrap scores higher than 0.9 are indicated on the nodes. P. xylostella serpins clustered to six distinct phylogenetic groups (A through F). The first two letters in each of the serpins represent the acronym of scientific name for a given species (Dm: D. melanogaster; Bm: B. mori; Ms: M. sexta; Ag: A. gambiae, Px: P. xylostella; Am: A. mellifera; Tc: T. castaneum)

Group B consisted of M. sexta, B. mori and A. mellifera serpin3, TcSRPN4, DmSpn27A, A. gambiae serpin1-3. Previous studies indicated that MsSRPN3 and Dmspn27A play major roles in regulation of proPO and spätzle activation [39, 55], and recombinant AgSRPN1 and AgSRPN2 can function as inhibitors of PAP3 [56]. Sequence alignment showed that PxSPI3, 18 and 19, BmSPI3, MsSRPN3a, MsSRPN3b, DmSpn27A, along with AgSRPN1, 2 and 3 shared 50.5% sequence identity and the conserved hinge regions as well as Lys (K) at their P1 positions (Additional file 2: Figure S2B) except for PxSPI19 and AgSRPN3. Therefore, we assume that PxSPI3 and 18 might have similar regulatory functions in proPO and spätzle activation in P. xylostella. In Group C, eight P. xylostella serpins clustered with M. sexta and B. mori serpins that were originally defined as group C [21]. The alignment showed that residues at the P1 and P1’ positions (Arg and Ile) and hinge region in PxSPI4, BmSPI4, MsSRPN4A and MsSRPN4B were identical (Additional file 2: Figure S2C) and sequence identity among the four serpins is 77.5%. PxSPI5, 16 and 22, BmSPI5, MsSRPN5A and MsSRPN5B also shared a high sequence identity (67.6%) with the predicted P1-P1’ (Arg-Ile/Ser) residues (Additional file 2: Figure S2D). In M. sexta, MsSRPN4 and MsSRPN5 can regulate proPO activation by inhibiting the target proteases upstream of PAPs [40, 57]. In B. mori, BmSPI5 functions as an inhibitor to form covalent complexes with either BmSP21 or BmHP6 in both the proPO activation and AMP-producing pathways [58]. Therefore, we suggest that PxSPI4, 5, 16 and 22 may be involved in regulating proPO activation by inhibiting the target proteases upstream of PAPs. Additionally, PxSPI15 was clustered with BmSPI7, PxSPI14 was clustered with BmSPI14, and PxSPI8 was clustered with BmSPI8 and BmSPI31. However, the functions of these serpins are unclear. PxSPI7, MsSRPN7 and BmSPI32 shared 51.7% sequence identity and relatively conserved hinge region, and the residues at the P1 and P1’ positions in PxSPI7 were Arg and Ile, identical to those in MsSRPN7 (Additional file 2: Figure S2E).

Group D was composed of 27 serpins from P. xylostella, B. mori, M. sexta, D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, T. castaneum and A. mellifera. PxSPI6 was homologue to BmSPI6, MsSRPN6, AgSRPN9, DmSpn88Ea and DmSpn88Eb, and they shared 67.8% sequence identity and the strictly conserved hinge region with identical Arg and Ser residues at P1 and P1’ positions (Additional file 2: Figure S2F). Previous studies suggest that MsSRPN6 and MsSRPN7 with Arg (R) at the P1 position are likely involved in regulation of proPO activation in plasma by inhibiting PAPs [13, 42]. Therefore, we assume that PxSPI6 and PxSPI7 may also function as inhibitors of the melanization cascade. Group E contained PxSRPN13, DmSpn28Dc, BmSPI13, AmSRPN4, TcSRPN26, TcSRPN27 and A. gambiae serpin 4–6 and 16. A. gambiae serpin 4–6 and 16 have been reported as mosquito-specific expansions [20, 59], and biochemical analysis indicated that AgSRPN6 is an inhibitor of trypsin-like serine proteases [60]. In group F, PxSPI10 was grouped with BmSPI27, TcSRPN2 and AgSRPN13, PxSPI20 was clustered with BmSPI29, AgSRPN19, TcSRPN6 and DmSpn85F. In D. melanogaster, DmSPN85F functions as a non-inhibitory serpin, and it is highly conserved in all the 12 sequenced Drosophilid genomes [15, 34]. A. gambiae SRPN13 and SRPN19 also have been predicted as non-inhibitor serpins [20]. Furthermore, PxSPI10 and PxSPI20 had the least conserved residues in the hinge region (Fig. 2), supporting a prediction that they may not function as inhibitors.

Canonical SPIs

A total of 33 SPIs genes were identified as canonical SPIs and were divided into seven different families (Trypsin Inhibitor like cysteine rich domain (TIL), Kunitz, Kazal, amfpi, Pacifastin, Antistasin and whey acidic protein (WAP); Additional file 1: Table S1). Seven of the eight SPI families found in B. mori [43] were identified in P. xylostella, except for Bowman-Birk family. Sequence alignments showed that the numbers and positions of Cys residues in the same family were highly conserved in P. xylostella canonical SPIs (Additional file 2: Figure S3). For instance, three pairs of disulfide bonds were identified in the Kunitz, Kazal, Pacifastin and Antistasin families, followed by four pairs in WAP, five pairs in TIL, and six pairs in amfpi (Additional file 2: Figure S3).

Domain architecture analysis suggests that 11 out of the 33 canonical inhibitors were single-domain proteins, while the remaining 22 SPIs encompassed multiple domains (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Proteolytic cleavage sites of P. xylostella canonical SPIs were investigated using sequence alignment with known SPIs. The P1 residue in the cleavage site determines the specific inhibitory activity of SPIs, with Arg or Lys in the P1 site indicating the inhibitory activity to trypsin-like enzymes, Ala, Val or Gly showing the inhibitory activity to elastase-like enzymes, and Phe, Tyr or Leu suggesting the inhibitory activity to chymotrypsin-like enzymes [43]. Furthermore, it has also been reported that a Thr residue at the P1 position of the FPI-F scissile bond has inhibitory activity to subtilisin and some fungal serine proteases [61]. The alignments indicated that PxSPI34 (TIL family) had a Leu residue at the P1 position, suggesting that it may be involved in inhibiting chymotrypsin-like enzymes; PxSPI43 (WAP family) had a Val residue at the P1 site with predicted inhibitory activity against elastase-like enzymes; PxSPI40 (Kunitz family) and PxSPI57 (amfpi family) had an Arg/Lys (R/K) at the predicted P1 position, suggesting they may interact with trypsin-like enzymes (Additional file 2: Figure S3).

In addition to single-domain inhibitors, 22 canonical PxSPIs contained two or more inhibitor domains (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Other than PxSPI28 (containing 17 tandemly arranged TIL domains), the other 21 PxSPIs contained 15 or fewer inhibitor domains (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Previous studies show that SPIs containing multiple inhibitor domains have various residues at the P1 positions, suggesting that they are likely to have different inhibitory activities [43, 62]. We found that PxSPI32 consisted of two TIL domains, with Ala and Lys residues at the P1 site of the first and second domains, respectively. PxSPI39 comprised two Kunitz domains, with Arg and Phe residues at the P1 site of the first and second domains, respectively. PxSPI48 contained four Kazal domians, with Ala residue at the P1 site of the first domain, and Arg residues at the P1 sites of the second, third and four domains. PxSPI51 and PxSPI54 contained three Kazal domains, with Phe, Arg and Lys residues at the P1 site of the first, second and third domains, respectively. PxSPI55 contained two Kazal domains, with Lys and Arg residues at the P1 site of the first and second domains, respectively. PxSPI58 consisted of four Pacifastin domains, with Arg residue at the P1 site of the first and second domains, and Leu residue at the P1 site of the third and fourth domains. Thus, PxSPI55 may have inhibitory activity to trypsin-like enzymes, PxSPI32 and PxSPI48 may have inhibitory activity against elastase-like and trypsin-like enzymes, PxSPI39, PxSPI51, PxSPI54 and PxSPI58 may have inhibitory activity to both trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like enzymes.

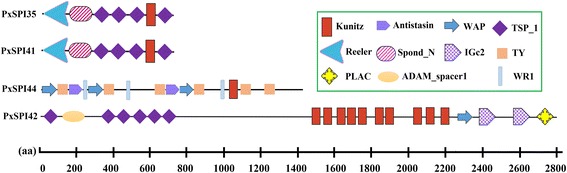

In addition, four SPIs, PxSPI35, PxSPI41, PxSPI42 and PxSPI44, comprised both inhibitor and non-inhibitor domains (Fig. 4). For instance, PxSPI35 and PxSPI41 were composed of one Kunitz domain, one reeling domain, one spond_N domain and four thrombospondin type 1 (TSP_1) domains, similar to the structure of B. mori BmSPI55 [43]. PxSPI42 had various types of domains, including Kunitz, WAP, TSP_1, immunoglobulin C-2 type (IGc2), ADAM_spacer1 and PLAC (protease and lacunin) domains. Moreover, PxSPI44 contained three inhibitor domains (Kunitz, WAP and Antisasin) and two non-inhibitor domains (thyroglobulin type I repeat (TY) and worm-specific repeat type 1 (WR1)).

Fig. 4.

Domain organization of four P. xylostella SPIs in the Kunitz family. The sizes of domains are indicated by the scale

Alpha-2-macroglobulins

In our study, three α2M genes were identified in the P. xylostella genome (Additional file 1: Table S1). To clarify the conserved and diverged residues of P. xylostella α2Ms, amino acid sequences of α2Ms were aligned and compared with other known α2M sequences using Clustal X and GeneDoc (Additional file 2: Figure S4). The results showed that PxSPI60 and PxSPI61 were composed of three functional domains required for the α2M mechanism, including a bait region, a thiol ester domain, and a receptor-binding domain, whereas PxSPI59 lacked the receptor-binding domain. The amino acid residues in the thiol ester domain in P. xylostella α2Ms were GCGEQNM, which are identical to those of α2Ms in other species. The region around the thiol ester domain of P. xylostella α2Ms showed similarity to the corresponding region in other α2Ms. Nevertheless, the similarity of the bait region between α2Ms of P. xylostella and other species was low as previously reported [63–66]. A completely conserved sequence of FPETW in the bait region of α2Ms in other species was replaced with FQEAW in PxSPI59 and PxSPI61, and with FPEAW in PxSPI60. The alignment also showed that the receptor binding regions of PxSPI60 and PxSPI61 shared high similarity with those of other α2Ms, and a consensus sequence of GGxxxTQDT was found in all the aligned sequences with GGMTNTQDT sequence in PxSPI60 and PxSPI61. Additionally, two amino acid blocks (Box1 and Box 2) (Additional file 2: Figure S4) in the N-terminus were conserved in all the aligned sequences, suggesting that these blocks may have an important functional or structural role. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed with the amino acid sequences of α2Ms, complement proteins and thioester-containing proteins (TEPs) using MEGA software (version 6.06) (Additional file 2: Figure S5), and the tree contained three main distinct branches, including α2Ms, TEPs and complement proteins. P. xylostella α2Ms were clustered with insect α2Ms, and they apparently are a monophyletic group.

Expression profiling of P. xylostella SPIs

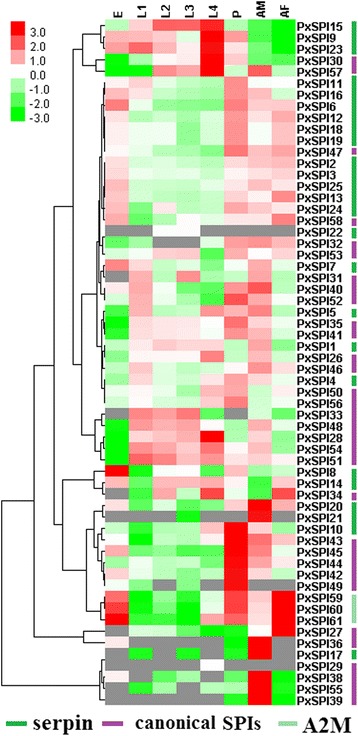

Stage-specific expression pattern

Using RNA-seq data, expression patterns of PxSPIs at different developmental stages of the insecticide-susceptible strain (Fuzhou-S), including egg, larva, pupa and adult, were characterized (Fig. 5 and Additional file 1: Table S3). The results showed that PxSPIs exhibited gene-differential, stage- and sex-specific patterns. For example, PxSPI15 and PxSPI33 were expressed at high levels exclusively in the larval stage. Sixteen PxSPIs (PxSPI2-3, 6, 12–13, 16, 20 and 24–25 from the serpin family, PxSPI42-43 from the WAP family, PxSPI58 from the Pacifastin family, and PxSPI59-61 from the α2M family) were expressed at moderate or high levels in eggs, pupae and adults, but were undetectable or at very low levels in the larval stage. Seven PxSPIs (PxSPI17 and PxSPI21 from the serpin family, PxSPI27 from the TIL family, PxSPI36 and 38–39 from the Kunitz family, and PxSPI55 from the Kazal family) displayed sex-specific patterns and were exclusively expressed at high levels in adults, with PxSPI27 highly expressed in females and the other six genes highly expressed in males. PxSPI9 and PxSPI23 were expressed predominantly in egg, larval and pupal stages, rather than in the adult stage. Five SPIs (PxSPI28 and 33 from the TIL family, and PxSPI48, 51 and 54 from the Kazal family) showed moderate transcript levels in larvae and adult males, and no expression was detected in eggs, pupae and adult females. The stage-specific expression patterns of 12 genes (Additional file 2: Figure S6) was confirmed by qPCR and the results were consistent with the RNA-seq data.

Fig. 5.

Expression profiling of PxSPIs at different developmental stages. The log2 RPKM values are colored, where red represents higher expression, green represents lower expression, and gray represents the RPKM values missed. E, eggs; L1-L4, 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th-instar larvae; P, pupae; AM, adult males; AF, adult females

Tissue-specific expression pattern

RNA-seq analysis showed that 56 of the 61 PxSPI genes exhibited expression in at least one tissue (Additional file 1: Table S4 and Additional file 2: Figure S7). The midgut of 4th-instar larvae had fewer number (5) of genes expressed among the four tissues, while the numbers of genes expressed in the heads of 4th-instar larvae, adult males and females were 32, 28 and 34, respectively. PxSPIs had inverse tissue distribution tendency when compared with PxSPs and PxSPHs (the highest numbers of SPs and SPHs were distributed in the midgut) [67]. Such a tendency was also documented in B. mori [43]. Five PxSPIs, including 2 serpins (PxSPI1 and PxSPI14) and three Kazals (PxSPI51, 54 and 55), were expressed in the 4th-instar larval midguts and heads, while 15 PxSPIs were all highly expressed in the heads of adult males and females. Thirteen PxSPIs (PxSPI2-6, 10–12 and 16 from the serpin family, PxSPI26 and PxSPI28 from the TIL family, and PxSPI45 and PxSPI48 from the Kazal family) were expressed at a higher level in the heads of both larvae and adults than in the midgut of the 4th-instar larvae.

Discussion

In the current study, we performed an overall analysis of SPI genes in P. xylostella, including analysis of their sequences, scaffold location, phylogeny, and expression profiles. A total of 61 SPI genes were identified in the P. xylostella genome, which were divided into nine different families based on the sequence similarity in amino acids. The number of SPI genes in P. xylostella is less than that in B. mori (80) [43]. This may result from fewer serpin (25) and TIL genes (9) identified in P. xylostella, compared to 34 annotated serpin and 15 TIL genes in the B. mori genome. In B. mori, eight silkworm-specific serpins and 9 genes of the TIL family have been found to come from tandem repeat evolution, and they may play important roles in protecting silk or protecting the cocoon from complicated environment conditions [21, 43].

Serpins are a superfamily of proteins with a number of functions, such as regulation of innate immunity, acting as tumor suppressors, hormone transports and molecular chaperones [15, 20, 21, 25–27]. A total of 25 P. xylostella serpins were identified, with each containing three β sheets and seven to nine α helices (Additional file 2: Figure S1), suggesting the overall folding of serpins remain largely unchanged in the long history of evolution [19, 68]. Mature P. xylostella serpin proteins were found to contain 379 ~ 503 aa with theoretical molecular masses of 41–55 kDa (Additional file 1: Table S1), consistent with previously documented sizes of serpins (350–500 aa) with molecular masses of 40–60 kDa [19, 69]. Moreover, we predict that the 20 P. xylostella serpins (PxSPI 1–7, 9, 11–18, 21–24) might be inhibitory serpins based on the conserved residues in the hinge region that can serve as a theoretical guideline to identify inhibitory serpins [20, 50]. Based on the results of sequence alignments and predicted proteolytic cleavage sites, we would suggest that 14 of the 25 P. xylostella serpins (PxSPI1-7, 11–12, 15–16, 18, 22 and 24) function as protease inhibitors. Phylogenetic analysis further confirmed that 14 putative P. xylostella inhibitory serpins were clustered with the known inhibitory serpins in other insect species (Fig. 3). Nine of 14 putative P. xylostella inhibitory serpins (PxSPI1, 3–7, 16, 18 and 22) were clustered with the orthologues in M. sexta (MsSRPN1 and 3–7) with a high sequence identity. These M. sexta serpins have been demonstrated to participate in regulating the prophenoloxidase activation cascade [13, 39, 40, 42, 54, 57]. Therefore, we propose that nine P. xylostella serpins may play vital roles in regulation of innate immunity in P. xylostella. PxSPI10 and PxSPI20 lack the characteristic features of inhibitory serpins, however, they were found to be highly expressed in pupae and adult males, respectively. Some serpins do not function as inhibitors, and others do inhibit proteases even though the conserved features are missing [70, 71]. It is worth testing the biological roles of PxSPI10 and PxSPI20 by genetic and biochemical studies.

Apart from the serpin family, the current work identified 33 SPIs belonging to canonical SPIs that contained rich cysteine residues to form disulfide bonds to keep their rigid structure. The rigid structure are necessary for keeping right conformation to interact with the active site of serine proteases [72]. And 11 of the 33 canonical inhibitors were single-domain proteins with low molecular weights, exemplified by PxSPI57 that contained an amfpi domain with a low molecular weight (8.97 kDa). A BLAST search of GenBank™ revealed that PxSPI57 was similar in amino acid sequence to the small cationic peptide (MsCP8) in the hemolymph of M. sexta larvae, BmSPI69 (B. mori), and a fungal protease inhibitor-1 of Antheraes mylitta (AmFPI-1). MsCP8 has a Lys residue at the P1 position, however, it shows no inhibitory activity against serine proteases [73]. AmFPI-1 shows inhibitory activity against some fungal serine proteases and trypsin [74], while BmSPI69 has a predicted P1 residue of Lys and may have inhibitory activity to trypsin-like enzymes [43]. Therefore, the exact function of PxSPI57 needs to be further studied. The remaining canonical PxSPIs contained two or more inhibitor domains, forming multi-domain compound inhibitors. The results were fully in consistent with those of previous work, in which the single inhibitor domain can be repeated 2–15 times to form multi-domain compound inhibitors in some SPI families [7, 8]. For instance, PxSPI26, PxSPI46 and PxSPI58 have 13 TIL, 6 Kazal, and 4 Pacifastin domains, respectively. In addition, some compound inhibitors contained inhibitor domains (from more than one family) and non-inhibitor domains, which are defined as mixed-type inhibitors, exemplified by PxSPI35, PxSPI41 and PxSPI42. PxSPI35 and PxSPI41 were homologous to BmSPI55 and F-spondin. F-spondin is an extracellular matrix protein that inhibits the outgrowth of embryonic motor axons in a contact-repulsion fashion [75]. BmSPI55 might play an important role in the innate immune system of B. mori [43]. BLAST search revealed that PxSPI42 was similar to BmSPI58 and papilin, which has a broad expression spectrum in different pericellular matrices in Drosophila embryos and is indispensable for embryonic development [76].

Gene expression profiles showed that PxSPI15 and PxSPI33 were expressed at high levels exclusively in the larval stage. Their expression patterns are extremely parallel to those of 50 serine protease genes previously found in P. xylostella [67]. Additionally, expression patters of seven PxSPIs (PxSPI17, 21, 27, 36, 38–39 and 55) are consistent with those of 16 serine protease genes highly and exclusively expressed in adult males and one highly expressed in adult females of P. xylostella [67], indicating that these PxSPIs may participate in regulation of the activity of serine proteases in adults. Their functions still need to be validated by molecular studies.

Conclusions

It is by far the most comprehensive research on whole-genome identification and expression profiling of SPIs in P. xylostella. We explored the sequences and possible physiological functions of P. xylostella serpins and canonical SPIs, revealing that nine P. xylostella serpins may have inhibitory activity and be involved in regulation of the immune system of an important agricultural pest, and some canonical SPIs may have inhibitory activity to trypsin/chymotrypsin/elastase-like enzymes. However, additional biochemical and biological studies are required to determine and validate their functions. Analyses of sequences, substrate specificity and domain architecture of alpha-2-macroglobulins will also be useful for further molecular genetic studies in P. xylostella. This article provides an overview of the P. xylostella SPIs, and will facilitate future functional investigation.

Methods

Identification of SPI genes in P. xylostella

SPI protein sequences of D. melanogaster, A. mellifera, T. castaneum, A. gambiae, B. mori and M. sexta were downloaded from their genome databases [77–81] and/or the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and then used as queries against the DBM database [49, 82] using local TBLASTN program (E-value < 10−7). We preformed online FGENESH+ programs (http://www.softberry.com/) to find complete open reading frames (ORFs) of SPI genes with the method used by Yu et al. and You et al. [83, 84]. These putative protein sequences were manually confirmed using NCBI online BLASTP.

Characterization of PxSPIs

Domain architectures of PxSPI genes were predicted by NCBI CDD database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/docs/cdd_search.html) and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). Theoretical molecular weight and isoelectric point of proteins were calculated based on the predicted sequences using Compute pI/Mw tool (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/). The signal peptides and their cleavage sites of SPIs were analyzed by online SignalP 4.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). Multiple sequence alignments of SPI protein sequences were performed by ClustalX 2.0 program with default parameters [85], and alignments were manually modified using GeneDoc (http:www.nrbsc.org/gfx/genedoc/index.html). The identical amino acids and blocks of conserved amino acid residues are shaded in black and gray, respectively. The reactive sites of SPIs were marked with asterisks.

Phylogenetic analyses

The phylogenetic relationships of SPI genes were compared among seven insect species: A. gambiae, D. melanogaster, M. sexta, B. mori, T. castaneum, A. mellifera and P. xylostella. Putative amino acid sequences of SPIs were aligned using ClustalX 2.0 [86]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA 6.06 using the neighbor-joining method by Poisson model with bootstrap test (1000 replicates) [87].

Expression profiling and qPCR analysis

Based on the RNA-seq data from different developmental stages and tissues previously completed in our laboratory, expression profiling of the 61 SPI genes were analyzed and clustered by Cluster 3.0 and visualized by Java TreeView [88]. The developmental stages (E: eggs; L1-L4: 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th instar larvae; P: pupae; AM: adult males; AF: adult females) and tissues (L4M & L4H: midguts and heads of 4th-instar larvae; and AMH & AFH: heads of adult males and adult females) were used in this study. The RPKM values were log2 transformed, and the clustered genes were illustrated in terms of their expression patterns using the similarity metric of Euclidean distance and clustering method of complete linkage [67, 83].

A susceptible strain of P. xylostella (originally collected from a vegetable field in Fuzhou) was reared on radish seedlings at 25 ± 2 °C, 70 ~ 80% RH, 16 : 8 h = light : dark cycle and used for genome sequencing [49]. Stage-specific diamondback moth samples (newly laid eggs, 1st-4th-instar larvae, pupae and unmated or mated adult males and females) were collected and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. The total RNA of each sample was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and digested with 1 μL gDNA Eraser (Takara Biotechnology (Japan) Co., Ltd.) for 2 min at 42 °C to remove contaminating genomic DNA. The template (cDNA) for qPCR was synthesized with total RNA (1 μg) using PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was carried out using a CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA). The 20 μL mixture included 10 μL 2× real-time PCR Mix (containing SYBR Green I), 2 μL cDNA template from the relative sample (100 ng/μL), 0.4 μL of each primer (10 mmol/L), and 7.2 μL nuclease-free water in each well of a 96-well plate. PCR was conducted with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s, and a final melting curve starting at 63 °C for 5 s up to 95 °C with 0.5 °C increments. Twelve SPI genes were selected for further validation of expression by qPCR and the primers were designed for qPCR performance (Additional file 1: Table S5). The P. xylostella ribosomal protein gene L32 was used as the housekeeping reference (forward primer: 5′-AAT CAG GCC AAT TTA CCG C-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CTG GGT TTA CGC CAG TTA CG-3′). Relative gene expression data were normalized against Ct values for the housekeeping gene.

The qPCR data were statistically analyzed using the R statistical program version 3.0.2, with the supplemented package ‘agricolae’ [89]. If the data satisfied normality assumption, one-way ANOVA was performed, otherwise the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test was used.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. David Perović for his kind help with English editing and polishing on the final version of our manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31320103922 and No. 31230061) and National Key Project of Fundamental Scientific Research (“973” Programs, No. 2011CB100404) in China, and the Fellowship of Outstanding PhD Students at Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (324-1122yb023). XY is supported by the Minjiang Scholar Program in Fujian Province (PRC) and the Advanced Talents of SAFEA.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the results of this article are available as supporting material.

Authors’ contributions

HL participated in the design of the study, carried out the bioinformatics analysis and drafted the manuscript. XL, JZ and HL carried out the biological experiments. YF carried out the statistical analysis. XY, XX, GY and MY contributed to the study design or manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

P. xylostella is not protected under any legislation in China, as a protected or endangered species regulating or restricting its collection. Neither specific permits were required for collecting the larvae from the field nor was animal ethics approval required for work with this invertebrate.

Abbreviations

- α2M

Alpha-2-macroglobulin

- aa

Amino acid

- ADAM_spacer1

Spacer-1 domain from the ADAM-TS family of metalloproteinase

- AgSRPN9

A. gambiae serpin9

- Am

Apis mellifera

- AmFPI-1

A fungal protease inhibitor-1 of Antheraes mylitta

- Bm

Bombyx mori

- Dm

Drosophila melanogaster

- DmSpn27A

D. melanogaster serpin27A

- IGc2

Immunoglobulin C-2 type

- Ms

Manduca sexta

- MsCP8

A small cationic peptide in the hemolymph of M. sexta

- MsSRPN 3–7

M. sexta serpin 3–7

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- PAPs

Prophenoloxidase activating proteases

- PLAC

Protease and lacunin

- PO

Phenoloxidase

- proPO

prophenoloxidase

- Px

Plutella xylostella

- RCL

Reactive center loop

- SPIs

Serine protease inhibitors

- Tc

Tribolium castaneum

- TEPs

Thioester-containing proteins

- TIL

Trypsin inhibitor-like cysteine-rich domain

- TSP_1

Thrombospondin type 1 repeat

- TY

Thyroglobulin type I repeat

- WAP

Whey acidic protein

- WR1

Worm-specific repeat type 1

Additional files

Description of serine protease inhibitor (SPI) genes in P. xylostella. Table S2. The predicted amino acid sequences of 61 SPIs. Table S3. RPKM values of the PxSPI genes at different developmental stages obtained from the RNA-seq data. Table S4. RPKM values of the PxSPI genes at different tissues obtained from the RNA-seq data. Table S5. Primers used for qPCR study on gene expression. (DOCX 52 kb)

Multiple sequence alignment of 25 P. xylostella serpins with known serpins from M. sexta (MsSRPN3-7), D. melanogaster (DmSpn27A) and A. gambiae (AgSRPN9) using Clustal X. Figure S2. Alignment of P. xylostella serpins with some known serpins from other insect species by Clustal X2. A, Alignment of PxSPI1 with MsSRPN1J and BmSPI1; B, Alignment of PxSPI3, 18 and 19 with MsSRPN3a, 3b, BmSPI3 and AgSRPN1, 2, 3; C, Alignment of PxSPI4 with MsSRPN4a, MsSRPN4b and BmSPI4; D, Alignment of PxSPIs 5, 16 and 22 with MsSRPN5A, 5B and BmSPI5. E, Alignment of PxSPI7 with MsSRPN7 and BmSPI7. F, Alignment of PxSPI6 with MsSRPN6, BmSPI6, AgSRPN9, DmSpn88Ea and DmSpn88Eb. Figure S3. Alignment of serine protease inhibitor domains using Clustal X2 with default parameters and shading was done using GeneDoc. (A) TIL family, (B) Kunitz family, (C) WAP family, (D) Kazal family, (E) amfpi family, (F) Antistasin family, (G) Pacifastin family. Figure S4. Multiple sequence alignment of P. xylostella α2Ms with other α2Ms using Clustal X2. Figure S5. Phylogenetic tree of α2Ms, complement proteins and thioester-containing proteins constructed using the neighbor joining method. Figure S6. qPCR-based expression profiling of PxSPI genes across different developmental stages. Figure S7. Expression profiling of the P. xylostella SPI genes in different tissues. (DOCX 8635 kb)

References

- 1.Tripathi LP, Sowdhamini R. Genome-wide survey of prokaryotic serine proteases: analysis of distribution and domain architectures of five serine protease families in prokaryotes. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:549. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross J, Jiang H, Kanost MR, Wang Y. Serine proteases and their homologs in the Drosophila melanogaster genome: an initial analysis of sequence conservation and phylogenetic relationships. Gene. 2003;304:117–31. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou Z, Lopez DL, Kanost MR, Evans JD, Jiang H. Comparative analysis of serine protease-related genes in the honey bee genome: possible involvement in embryonic development and innate immunity. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15(5):603–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao P, Wang GH, Dong ZM, Duan J, Xu PZ, Cheng TC, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of serine proteases and homologs in the silkworm Bombyx mori. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou Z, Shin SW, Alvarez KS, Kokoza V, Raikhel AS. Distinct melanization pathways in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Immunity. 2010;32(1):41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neurath H. Proteolytic processing and physiological regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1989;14(7):268–71. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krowarsch D, Cierpicki T, Jelen F, Otlewski J. Canonical protein inhibitors of serine proteases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60(11):2427–44. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3120-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawlings ND, Tolle DP, Barrett AJ. Evolutionary families of peptidase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2004;378(Pt 3):705–16. doi: 10.1042/bj20031825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otlewski J, Krowarsch D, Apostoluk W. Protein inhibitors of serine proteinases. Acta Biochim Pol. 1999;46(3):531–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigle LT, Ramalho-Ortigão M. Kazal-type serine proteinase inhibitors in the midgut of Phlebotomus papatasi. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108(6):671–8. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276108062013001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ligoxygakis P, Roth S, Reichhart JM. A serpin regulates dorsal-ventral axis formation in the Drosophila embryo. Curr Biol. 2003;13(23):2097–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham EG, Pinto SB, Ghosh A, Vanlandingham DL, Budd A, Higgs S, et al. An immune-responsive serpin, SRPN6, mediates mosquito defense against malaria parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(45):16327–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508335102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou Z, Jiang H. Manduca sexta serpin-6 regulates immune serine proteinases PAP-3 and HP8. cDNA cloning, protein expression, inhibition kinetics, and function elucidation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(14):14341–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500570200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An C, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta serpin-5 regulates prophenoloxidase activation and the Toll signaling pathway by inhibiting hemolymph proteinase HP6. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;40(9):683–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichhart JM. Tip of another iceberg: Drosophila serpins. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(12):659–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanost MR. Serine proteinase inhibitors in arthropod immunity. Dev Comp Immunol. 1999;23(4–5):291–301. doi: 10.1016/S0145-305X(99)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huntington JA. Serpin structure, function and dysfunction. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(Suppl 1):26–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gatto M, Iaccarino L, Ghirardello A, Bassi N, Pontisso P, Punzi L, et al. Serpins, immunity and autoimmunity: old molecules, new functions. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45(2):267–80. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gettins PG. Serpin structure, mechanism, and function. Chem Rev. 2002;102(12):4751–804. doi: 10.1021/cr010170+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suwanchaichinda C, Kanost MR. The serpin gene family in Anopheles gambiae. Gene. 2009;442(1–2):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou Z, Picheng Z, Weng H, Mita K, Jiang H. A comparative analysis of serpin genes in the silkworm genome. Genomics. 2009;93(4):367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray CA, Black RA, Kronheim SR, Greenstreet TA, Sleath PR, Salvesen GS, et al. Viral inhibition of inflammation: cowpox virus encodes an inhibitor of the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Cell. 1992;69(4):597–604. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90223-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irving JA, Pike RN, Dai W, Brömme D, Worrall DM, Silverman GA, et al. Evidence that serpin architecture intrinsically supports papain-like cysteine protease inhibition: engineering alpha(1)-antitrypsin to inhibit cathepsin proteases. Biochemistry. 2002;41(15):4998–5004. doi: 10.1021/bi0159985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schick C, Pemberton PA, Shi GP, Kamachi Y, Cataltepe S, Bartuski AJ, et al. Cross-class inhibition of the cysteine proteinases cathepsins K, L, and S by the serpin squamous cell carcinoma antigen 1: a kinetic analysis. Biochemistry. 1998;37(15):5258–66. doi: 10.1021/bi972521d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou Z, Anisowicz A, Hendrix MJ, Thor A, Neveu M, Sheng S, et al. Maspin, a serpin with tumor-suppressing activity in human mammary epithelial cells. Science. 1994;263(5146):526–9. doi: 10.1126/science.8290962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pemberton PA, Stein PE, Pepys MB, Potter JM, Carrell RW. Hormone binding globulins undergo serpin conformational change in inflammation. Nature. 1988;336(6196):257–8. doi: 10.1038/336257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagata K. Hsp47: a collagen-specific molecular chaperone. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21(1):22–6. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(06)80023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu CT, Pizzo SV. Alpha 2-macroglobulin, complement, and biologic defense: antigens, growth factors, microbial proteases, and receptor ligation. Lab Invest. 1994;71(6):792–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwaki D, Kawabata S, Miura Y, Kato A, Armstrong PB, Quigley JP, et al. Molecular cloning of Limulus alpha 2-macroglobulin. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242(3):822–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0822r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gollas-Galván T, Sotelo-Mundo RR, Yepiz-Plascencia G, Vargas-Requena C, Vargas-Albores F. Purification and characterization of alpha 2-macroglobulin from the white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2003;134(4):431–8. doi: 10.1016/S1532-0456(03)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sottrup-Jensen L, Hansen HF, Pedersen HS, Kristensen L. Localization of epsilon-lysylg-gamma-glutamyl cross-links in five human a2-macroglobuline-proteinase complexes. Nature of the high molecular weight cross-linked products. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17727–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laskowski M, Kato I. Protein inhibitors of proteinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:593–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waterhouse RM, Kriventseva EV, Meister S, Xi Z, Alvarez KS, Bartholomay LC, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of immune-related genes and pathways in disease-vector mosquitoes. Science. 2007;316(5832):1738–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1139862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrett M, Fullaondo A, Troxler L, Micklem G, Gubb D. Identification and analysis of serpin-family genes by homology and synteny across the 12 sequenced Drosophilid genomes. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:489. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou Z, Evans JD, Lu Z, Zhao P, Williams M, Sumathipala N, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the Tribolium immune system. Genome Biol. 2007;8(8):R177. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka H, Ishibashi J, Fujita K, Nakajima Y, Sagisaka A, Tomimoto K, et al. A genome-wide analysis of genes and gene families involved in innate immunity of Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38(12):1087–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang H, Kanost MR. Characterization and functional analysis of 12 naturally occurring reactive site variants of serpin-1 from Manduca sexta. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(2):1082–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gan H, Wang Y, Jiang H, Mita K, Kanost MR. A bacteria-induced, intracellular serpin in granular hemocytes of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;31(9):887–98. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(01)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu Y, Wang Y, Gorman MJ, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta serpin-3 regulates prophenoloxidase activation in response to infection by inhibiting prophenoloxidase-activating proteinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(47):46556–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR. Identification of plasma proteases inhibited by Manduca sexta serpin-4 and serpin − 5 and their association with components of the prophenoloxi-dase activation pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14932–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500532200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Jiang HB. Purification and characterization of Manduca sexta serpin-6: a serine proteinase inhibitor that selectively inhibits prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-3. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34(4):387–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suwanchaichinda C, Ochieng R, Zhuang S, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta serpin-7, a putative regulator of hemolymph prophenoloxidase activation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;43(7):555–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao P, Dong Z, Duan J, Wang G, Wang L, Li Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and immune response analysis of serine protease inhibitor genes in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramesh N, Sugumaran M, Mole JE. Purification and characterization of two trypsin inhibitors from the hemolymph of Manduca sexta larvae. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(23):11523–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soares TS, Buarque DS, Queiroz BR, Gomes CM, Braz GR, Araujo RN, et al. A Kazal-type inhibitor is modulated by Trypanosoma cruzi to control microbiota inside the anterior midgut of Rhodnius prolixus. Biochimie. 2015;112:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song KH, Jung MK, Eum JH, Hwang IC, Han SS. Proteomic analysis of parasitized Plutella xylostella larvae plasma. J Insect Physiol. 2008;54(8):1270–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han P, Jin F, Dong X, Fan J, Qiu B, Ren S. Transcript and protein profiling analysis of the Destruxin A-induced response in larvae of Plutella xylostella. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han P, Fan J, Liu Y, Cuthbertson AG, Yan S, Qiu BL, et al. RNAi-mediated knockdown of serine protease inhibitor genes increases the mortality of Plutella xylostella challenged by destruxin A. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.You M, Yue Z, He W, Yang X, Yang G, Xie M, et al. A heterozygous moth genome provides insights into herbivory and detoxification. Nat Genet. 2013;45(2):220–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Irving JA, Pike RN, Lesk AM, Whisstock JC. Phylogeny of the serpin superfamily: implications of patterns of amino acid conservation for structure and function. Genome Res. 2000;10(12):1845–64. doi: 10.1101/gr.GR-1478R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whisstock JC, Skinner R, Carrell RW, Lesk AM. Conformational changes in serpins: I. The native and cleaved conformations of alpha(1)-antitrypsin. J Mol Biol. 2000;296(2):685–99. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stein PE, Carrell RW. What do dysfunctional serpins tell us about molecular mobility and disease? Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2(2):96–113. doi: 10.1038/nsb0295-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gulley MM, Zhang X, Michel K. The roles of serpins in mosquito immunology and physiology. J Insect Physiol. 2013;59(2):138–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang H, Wang Y, Yu XQ, Zhu Y, Kanost M. Prophenoloxidase-activating proteinase-3 (PAP-3) from Manduca sexta hemolymph: a clip-domain serine proteinase regulated by serpin-1 J and serine proteinase homologs. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33(10):1049–60. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Gregorio E, Han SJ, Lee WJ, Baek MJ, Osaki T, Kawabata S, et al. An immune-responsive serpin regulates the melanization cascade in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2002;3(4):581–92. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michel K, Suwanchaichinda C, Morlais I, Lambrechts L, Cohuet A, Awono-Ambene PH, et al. Increased melanizing activity in Anopheles gambiae does not affect development of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(45):16858–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608033103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tong Y, Kanost MR. Manduca sexta serpin-4 and serpin-5 inhibit the prophenol oxidase activation pathway: cDNA cloning, protein expression, and characterization. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(15):14923–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li J, Ma L, Lin Z, Zou Z, Lu Z. Serpin-5 regulates prophenoloxidase activation and antimicrobial peptide pathways in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;73:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michel K, Budd A, Pinto S, Gibson TJ, Kafatos FC. Anopheles gambiae SRPN2 facilitates midgut invasion by the malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. EMBO reports. 2005;6(9):891–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.An C, Hiromasa Y, Zhang X, Lovell S, Zolkiewski M, Tomich JM, et al. Biochemical characterization of Anopheles gambiae SRPN6, a malaria parasite invasion marker in mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eguchi M, Itoh M, Chou LY, Nishino K. Purification and characterization of a fungal protease specific protein inhibitor (FPI-F) in the silkworm haemolymph. Comp Biochem Physiol B Comp biochemistry. 1993;104(3):537–43. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(93)90279-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Breugelmans B, Simonet G, van Hoef V, Van Soest S, Smagghe G, Vanden BJ. A lepidopteran pacifastin member: cloning, gene structure, recombinant production, transcript profiling and in vitro activity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39(7):430–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qin C, Chen L, Qin JG, Zhao D, Zhang H, Wu P, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of alpha 2-macroglobulin (alpha2-M) from the haemocytes of Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010;29(2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaseeharan B, Lin YC, Ko CF, Chiou TT, Chen JC. Molecular cloning and characterisation of a thioester-containing alpha2-macroglobulin (alpha2-M) from the haemocytes of mud crab Scylla serrata. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2007;22(1–2):115–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rattanachai A, Hirono I, Ohira T, Takahashi Y, Aoki T. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of alpha 2-macroglobulin in the kuruma shrimp, Marsupenaeus japonicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2004;16(5):599–611. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosa RD, Perazzolo LM, Barracco MA. Comparison of the thioester domain and adjacent regions of the alpha2-macroglobulin from different South Atlantic crustaceans. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008;24(2):257–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin H, Xia X, Yu L, Vasseur L, Gurr GM, Yao F, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of serine proteases and homologs in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.) BMC genomics. 2015;16:1054. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Law RH, Zhang Q, McGowan S, Buckle AM, Silverman GA, Wong W, et al. An overview of the serpin superfamily. Genome Biol. 2006;7(5):216. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-5-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Silverman GA, Bird PI, Carrell RW, Church FC, Coughlin PB, Gettins PG, et al. The serpins are an expanding superfamily of structurally similar but functionally diverse proteins. Evolution, mechanism of inhibition, novel functions, and a revised nomenclature. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(36):33293–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stark KR, James AA. Isolation and characterization of the gene encoding a novel factor Xa-directed anticoagulant from the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(33):20802–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van Gent D, Sharp P, Morgan K, Kalsheker N. Serpins: structure, function and molecular evolution. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35(11):1536–47. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Simonet G, Claeys I, Broeck JV. Structural and functional properties of a novel serine protease inhibiting peptide family in arthropods. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;132(1):247–55. doi: 10.1016/S1096-4959(01)00530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ling E, Rao XJ, Ao JQ, Yu XQ. Purification and characterization of a small cationic protein from the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39(4):263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shrivastava B, Ghosh AK. Protein purification, cDNA cloning and characterization of a protease inhibitor from the Indian tasar silkworm, Antheraea mylitta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33(10):1025–33. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tzarfati-Majar V, Burstyn-Cohen T, Klar A. F-spondin is a contact-repellent molecule for embryonic motor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4722–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081062398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kramerova IA, Kramerov AA, Fessler JH. Alternative splicing of papilin and the diversity of Drosophila extracellular matrix during embryonic morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2003;226(4):634–42. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marygold SJ, Leyland PC, Seal RL, Goodman JL, Thurmond J, Strelets VB, et al. FlyBase: improvements to the bibliography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D751–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Munoz-Torres MC, Reese JT, Childers CP, Bennett AK, Sundaram JP, Childs KL, et al. Hymenoptera Genome Database: integrated community resources for insect species of the order Hymenoptera. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D658–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim HS, Murphy T, Xia J, Caragea D, Park Y, Beeman RW, et al. BeetleBase in 2010: revisions to provide comprehensive genomic information for Tribolium castaneum. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D437–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Megy K, Emrich SJ, Lawson D, Campbell D, Dialynas E, Hughes DS, et al. VectorBase: improvements to a bioinformatics resource for invertebrate vector genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D729–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang J, Xia Q, He X, Dai M, Ruan J, Chen J, et al. SilkDB: a knowledgebase for silkworm biology and genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue):D399–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tang W, Yu L, He W, Yang G, Ke F, Baxter SW, et al. DBM-DB: the diamondback moth genome database. Database (Oxford) 2014;2014:bat087. doi: 10.1093/database/bat087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu L, Tang W, He W, Ma X, Vasseur L, Baxter SW, et al. Characterization and expression of the cytochrome P450 gene family in diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.) Sci Rep. 2015;5:8952. doi: 10.1038/srep08952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.You Y, Xie M, Ren N, Cheng X, Li J, Ma X, et al. Characterization and expression profiling of glutathione S-transferases in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.) BMC Genomics. 2015;16:152. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1343-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Georgieva D, Greunke K, Arni RK, Betzel C. Three-dimensional modelling of honeybee venom allergenic proteases: relation to allergenicity. Z Naturforsch C. 2011;66(5–6):305–12. doi: 10.5560/ZNC.2011.66c0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1453–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saldanha AJ. Java Treeview--extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):3246–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mendiburu FD. Agricolae: statistical procedures for agricultural research. R package version. 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets supporting the results of this article are available as supporting material.