Abstract

Ketone body metabolism is a central node in physiological homeostasis. In this review, we discuss how ketones serve discrete fine-tuning metabolic roles that optimize organ and organism performance in varying nutrient states, and protect from inflammation and injury in multiple organ systems. Traditionally viewed as metabolic substrates enlisted only in carbohydrate restriction, recent observations underscore the importance of ketone bodies as vital metabolic and signaling mediators when carbohydrates are abundant. Complementing a repertoire of known therapeutic options for diseases of the nervous system, prospective roles for ketone bodies in cancer have arisen, as have intriguing protective roles in heart and liver, opening therapeutic options in obesity-related and cardiovascular disease. Controversies in ketone metabolism and signaling are discussed to reconcile classical dogma with contemporary observations.

Introduction

Ketone bodies are a vital alternative metabolic fuel source for all the domains of life, eukarya, bacteria, and archaea (Aneja et al., 2002; Cahill GF Jr, 2006; Krishnakumar et al., 2008). Ketone body metabolism in humans has been leveraged to fuel the brain during episodic periods of nutrient deprivation. Ketone bodies are interwoven with crucial mammalian metabolic pathways such as β-oxidation (FAO), the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), gluconeogenesis, de novo lipogenesis (DNL), and biosynthesis of sterols. In mammals, ketone bodies are produced predominantly in the liver from FAO-derived acetyl-CoA, and they are transported to extrahepatic tissues for terminal oxidation. This physiology provides an alternative fuel that is augmented by relatively brief periods of fasting, which increases fatty acid availability and diminishes carbohydrate availability (Cahill GF Jr, 2006; McGarry and Foster, 1980; Robinson and Williamson, 1980). Ketone body oxidation becomes a significant contributor to overall energy mammalian metabolism within extrahepatic tissues in a myriad of physiological states, including fasting, starvation, the neonatal period, post-exercise, pregnancy, and adherence to low carbohydrate diets. Circulating total ketone body concentrations in healthy adult humans normally exhibit circadian oscillations between approximately 100–250 µM, rise to ~1 mM after prolonged exercise or 24h of fasting, and can accumulate to as high as 20 mM in pathological states like diabetic ketoacidosis (Cahill GF Jr, 2006; Johnson et al., 1969b; Koeslag et al., 1980; Robinson and Williamson, 1980; Wildenhoff et al., 1974). The human liver produces up to 300 g of ketone bodies per day (Balasse and Fery, 1989), which contribute between 5–20% of total energy expenditure in fed, fasted, and starved states (Balasse et al., 1978; Cox et al., 2016).

Recent studies now highlight imperative roles for ketone bodies in mammalian cell metabolism, homeostasis, and signaling under a wide variety of physiological and pathological states. Apart from serving as energy fuels for extrahepatic tissues like brain, heart, or skeletal muscle, ketone bodies play pivotal roles as signaling mediators, drivers of protein post-translational modification (PTM), and modulators of inflammation and oxidative stress. In this review, we provide both classical and modern views of the pleiotropic roles of ketone bodies and their metabolism.

Overview of ketone body metabolism

The rate of hepatic ketogenesis is governed by an orchestrated series of physiological and biochemical transformations of fat. Primary regulators include lipolysis of fatty acids from triacylglycerols, transport to and across the hepatocyte plasma membrane, transport into mitochondria via carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), the β-oxidation spiral, TCA cycle activity and intermediate concentrations, redox potential, and the hormonal regulators of these processes, predominantly glucagon and insulin [reviewed in (Arias et al., 1995; Ayte et al., 1993; Ehara et al., 2015; Ferre et al., 1983; Kahn et al., 2005; McGarry and Foster, 1980; Williamson et al., 1969)]. Classically ketogenesis is viewed as a spillover pathway, in which β-oxidation-derived acetyl-CoA exceeds citrate synthase activity and/or oxaloacetate availability for condensation to form citrate. Three-carbon intermediates exhibit anti-ketogenic activity, presumably due to their ability to expand the oxaloacetate pool for acetyl-CoA consumption, but hepatic acetyl-CoA concentration alone does not determine ketogenic rate (Foster, 1967; Rawat and Menahan, 1975; Williamson et al., 1969). The regulation of ketogenesis by hormonal, transcriptional, and post-translational events together support the notion that the molecular mechanisms that fine tune ketogenic rate remain incompletely understood (see Regulation of HMGCS2 and SCOT/OXCT1).

Ketogenesis occurs primarily in hepatic mitochondrial matrix at rates proportional to total fat oxidation. After transport of acyl chains across the mitochondrial membranes and β-oxidation, the mitochondrial isoform of 3-hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMGCS2) catalyzes the fate committing condensation of acetoacetyl-CoA (AcAc-CoA) and acetyl-CoA to generate HMG-CoA (Fig. 1A). HMG-CoA lyase (HMGCL) cleaves HMG-CoA to liberate acetyl-CoA and acetoacetate (AcAc), and the latter is reduced to d-β-hydroxybutyrate (d-βOHB) by phosphatidylcholine-dependent mitochondrial d-βOHB dehydrogenase (BDH1) in a NAD+/NADH-coupled near-equilibrium reaction (Bock and Fleischer, 1975; LEHNINGER et al., 1960). The BDH1 equilibrium constant favors d-βOHB production, but the ratio of AcAc/d-βOHB ketone bodies is directly proportional to mitochondrial NAD+/NADH ratio, and thus BDH1 oxidoreductase activity modulates mitochondrial redox potential (Krebs et al., 1969; Williamson et al., 1967). AcAc can also spontaneously decarboxylate to acetone (Pedersen, 1929), the source of sweet odor in humans suffering ketoacidosis (i.e., total serum ketone bodies > ~7 mM; AcAc pKa 3.6, βOHB pKa 4.7). The mechanisms through which ketone bodies are transported across the mitochondrial inner membrane are not known, but AcAc/d-βOHB are released from cells via monocarboxylate transporters (in mammals, MCT 1 and 2, also known as solute carrier 16A family members 1 and 7) and transported in the circulation to extrahepatic tissues for terminal oxidation (Cotter et al., 2011; Halestrap and Wilson, 2012; Halestrap, 2012; Hugo et al., 2012). Concentrations of circulating ketone bodies are higher than those in the extrahepatic tissues (Harrison and Long, 1940) indicating ketone bodies are transported down a concentration gradient. Loss-of-function mutations in MCT1 are associated with spontaneous bouts of ketoacidosis, suggesting a critical role in ketone body import.

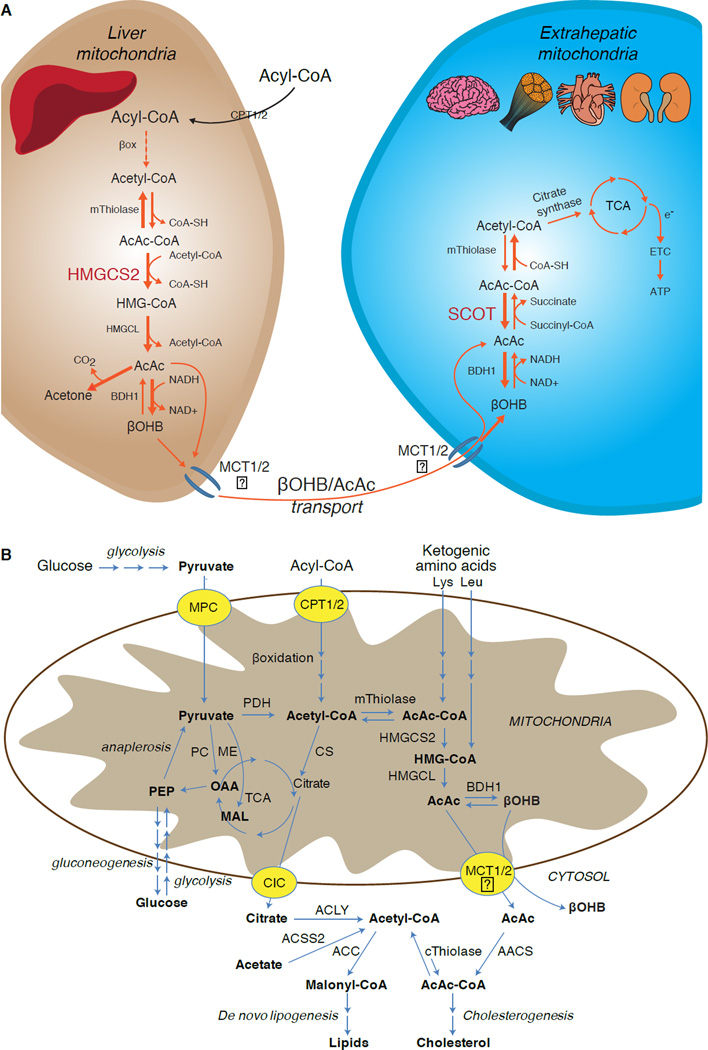

Fig. 1. Metabolism of ketone bodies.

(A) Ketogenesis within hepatic mitochondria is the primary source of circulating ketone bodies, requiring the fate-committing enzyme HMGCS2. Ketone bodies are secreted, and their primary metabolic fate is terminal oxidation within mitochondria of extrahepatic tissues through reactions that require the enzyme SCOT. mThiolase (mitochondrial thiolase); e−, electrons emanating from TCA cycle as NADH and FADH2; ETC, electron transport chain. Question marks reflect uncertainty of the mechanism responsible for transporting ketones across the inner mitochondrial membrane. (B) Ketone body metabolism is integrated through mitochondrial and cytoplasmic metabolic pathways. Cytoplasmic lipogenesis and cholesterol synthesis are nonoxidative metabolic fates of ketone bodies. mThiolase or cThiolase activity is encoded by at least 6 genes: ACAA1, ACAA2 (encoding an enzyme known as T1 or CT), ACAT1 (encoding T2), ACAT2, HADHA, and HADHB. ACSS2, acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (cytoplasmic).

With the exception of potential diversion of ketone bodies into non-oxidative fates (see Non-oxidative metabolic fates of ketone bodies), hepatocytes lack the ability to metabolize the ketone bodies they produce. Ketone bodies synthesized de novo by liver are (i) catabolized in mitochondria of extrahepatic tissues to acetyl-CoA, which is available to the TCA cycle for terminal oxidation (Fig. 1A), (ii) diverted to the lipogenesis or sterol synthesis pathways (Fig. 1B), or (iii) excreted in the urine. As an alternative energetic fuel, ketone bodies are avidly oxidized in heart, skeletal muscle, and brain (Balasse and Fery, 1989; Bentourkia et al., 2009; Owen et al., 1967; Reichard et al., 1974; Sultan, 1988). Extrahepatic mitochondrial BDH1 catalyzes the first reaction of βOHB oxidation, converting it to back AcAc (LEHNINGER et al., 1960; Sandermann et al., 1986). A cytoplasmic d-βOHB-dehydrogenase (BDH2) with only 20% sequence identity to BDH1 has a high Km for ketone bodies, and also plays a role in iron homeostasis (Davuluri et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2006). In extrahepatic mitochondrial matrix, AcAc is activated to AcAc-CoA through exchange of a CoA-moiety from succinyl-CoA in a reaction catalyzed by a unique mammalian CoA transferase, succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid-CoA transferase (SCOT, CoA transferase; encoded by OXCT1), through a near equilibrium reaction. The free energy released by hydrolysis of AcAc-CoA is greater than that of succinyl-CoA, favoring AcAc formation. Thus ketone body oxidative flux occurs due to mass action: an abundant supply of AcAc and rapid consumption of acetyl-CoA through citrate synthase favors AcAc-CoA (+ succinate) formation by SCOT. Notably, in contrast to glucose (hexokinase) and fatty acids (acyl-CoA synthetases), the activation of ketone bodies (SCOT) into an oxidizable form does not require the investment of ATP. A reversible AcAc-CoA thiolase reaction [catalyzed by any of the four mitochondrial thiolases encoded by either ACAA2 (encoding an enzyme known as T1 or CT), ACAT1 (encoding T2), HADHA, or HADHB] yields two molecules of acetyl-CoA, which enter the TCA cycle (Hersh and Jencks, 1967; Stern et al., 1956; Williamson et al., 1971). During ketotic states (i.e., total serum ketones > 500 µM), ketone bodies become significant contributors to energy expenditure, and are utilized in tissues rapidly until uptake or saturation of oxidation occurs (Balasse et al., 1978; Balasse and Fery, 1989; Edmond et al., 1987). A very small fraction of liver-derived ketone bodies can be readily measured in the urine, and utilization and reabsorption rates by the kidney are proportionate to circulating concentration (Goldstein, 1987; Robinson and Williamson, 1980). During highly ketotic states (> 1 mM in plasma), ketonuria serves as a semi-quantitative reporter of ketosis, although most clinical assays of urine ketone bodies detect AcAc but not βOHB (Klocker et al., 2013).

Ketogenic substrates and their impact on hepatocyte metabolism

Ketogenic substrates include fatty acids and amino acids (Fig. 1B). The catabolism of amino acids, especially leucine, generates about 4% of ketone bodies in post-absorptive state (Thomas et al., 1982). Thus the acetyl-CoA substrate pool to generate ketone bodies mainly derives from fatty acids, because during states of diminished carbohydrate supply, pyruvate enters the hepatic TCA cycle primarily via anaplerosis, i.e., ATP-dependent carboxylation to oxaloacetate (OAA), or to malate (MAL), and not oxidative decarboxylation to acetyl-CoA (Jeoung et al., 2012; Magnusson et al., 1991; Merritt et al., 2011). In liver, glucose and pyruvate contribute negligibly to ketogenesis, even when pyruvate decarboxylation to acetyl-CoA is maximal (Jeoung et al., 2012).

Acetyl-CoA subsumes several roles integral to hepatic intermediary metabolism beyond ATP generation via terminal oxidation (also see The integration of ketone body metabolism, post-translational modification, and cell physiology). Acetyl-CoA allosterically activates (i) pyruvate carboxylase (PC), thereby activating a metabolic control mechanism that augments anaplerotic entry of metabolites into the TCA cycle (Owen et al., 2002; Scrutton and Utter, 1967) and (ii) pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, which phosphorylates and inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) (Cooper et al., 1975), thereby further enhancing flow of pyruvate into the TCA cycle via anaplerosis. Furthermore, cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA, whose pool is augmented by mechanisms that convert mitochondrial acetyl-CoA to transportable metabolites, inhibits fatty acid oxidation: acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) catalyzes the conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, the lipogenic substrate and allosteric inhibitor of mitochondrial CPT1 [reviewed in (Kahn et al., 2005; McGarry and Foster, 1980)]. Thus, the mitochondrial acetyl-CoA pool both regulates and is regulated by the spillover pathway of ketogenesis, which orchestrates key aspects of hepatic intermediary metabolism.

Non-oxidative metabolic fates of ketone bodies

The predominant fate of liver derived ketones is SCOT-dependent extrahepatic oxidation. However, AcAc can be exported from mitochondria and utilized in anabolic pathways via conversion to AcAc-CoA by an ATP-dependent reaction catalyzed by cytoplasmic acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase (AACS, Fig. 1B). This pathway is active during brain development and in lactating mammary gland (Morris, 2005; Robinson and Williamson, 1978; Ohgami et al., 2003). AACS is also highly expressed in adipose tissue, and activated osteoclasts (Aguilo et al., 2010; Yamasaki et al., 2016). Cytoplasmic AcAc-CoA can be either directed by cytosolic HMGCS1 toward sterol biosynthesis, or cleaved by either of two cytoplasmic thiolases to acetyl-CoA (ACAA1 and ACAT2), carboxylated to malonyl-CoA, and contribute to the synthesis of fatty acids (Bergstrom et al., 1984; Edmond, 1974; Endemann et al., 1982; Geelen et al., 1983; Webber and Edmond, 1977).

While the physiological significance is yet to be established, ketones can serve as anabolic substrates even in the liver. In artificial experimental contexts, AcAc can contribute to as much as half of newly synthesized lipid, and up to 75% of new synthesized cholesterol (Endemann et al., 1982; Geelen et al., 1983; Freed et al., 1988). Because AcAc is derived from incomplete hepatic fat oxidation, the ability of AcAc to contribute to lipogenesis in vivo would imply hepatic futile cycling, where fat-derived ketones can be utilized for lipid production, a notion whose physiological significance requires experimental validation, but could serve adaptive or maladaptive roles (Solinas et al., 2015). AcAc avidly supplies cholesterogenesis, with a low AACS Km-AcAc (~50 µM) favoring AcAc activation even in the fed state (Bergstrom et al., 1984). The dynamic role of cytoplasmic ketone metabolism has been suggested in primary mouse embryonic neurons and in 3T3-L1 derived-adipocytes, as AACS knockdown impaired differentiation of each cell type (Hasegawa et al., 2012a; Hasegawa et al., 2012b). Knockdown of AACS in mice in vivo decreased serum cholesterol (Hasegawa et al., 2012c). SREBP-2, a master transcriptional regulator of cholesterol biosynthesis, and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)-γ are AACS transcriptional activators, and regulate its transcription during neurite development and in the liver (Aguilo et al., 2010; Hasegawa et al., 2012c). Taken together, cytoplasmic ketone body metabolism may be important in select conditions or disease natural histories, but are inadequate to dispose of liver derived ketone bodies, as massive hyperketonemia occurs in the setting of selective impairment of the primary oxidative fate via loss of function mutations to SCOT (Berry et al., 2001; Cotter et al., 2011).

Regulation of HMGCS2 and SCOT/OXCT1

The divergence of a mitochondrial from the gene encoding cytosolic HMGCS occurred early in vertebrate evolution due to the need to support hepatic ketogenesis in species with higher brain to body weight ratios (Boukaftane et al., 1994; Cunnane and Crawford, 2003). Naturally occurring loss-of-function HMGCS2 mutations in humans cause bouts of hypoketotic hypoglycemia (Pitt et al., 2015; Thompson et al., 1997). Robust HMGCS2 expression is restricted to hepatocytes and colonic epithelium, and its expression and enzymatic activity are coordinated through diverse mechanisms (Mascaro et al., 1995; McGarry and Foster, 1980; Robinson and Williamson, 1980). While the full scope of physiological states that influence HMGCS2 requires further elucidation, its expression and/or activity is regulated during the early postnatal period, aging, diabetes, starvation or ingestion of ketogenic diet (Balasse and Fery, 1989; Cahill GF Jr, 2006; Girard et al., 1992; Hegardt, 1999; Satapati et al., 2012; Sengupta et al., 2010). In the fetus, methylation of 5’ flanking region of Hmgcs2 gene inversely correlates with its transcription, and is partially reversed after birth (Arias et al., 1995; Ayte et al., 1993; Ehara et al., 2015; Ferre et al., 1983). Similarly, hepatic Bdh1 exhibits a developmental expression pattern, increasing from birth to weaning, and is also induced by ketogenic diet in a fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-21-dependent manner (Badman et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 1989). Ketogenesis in mammals is highly responsive to both insulin and glucagon, being suppressed and stimulated, respectively (McGarry and Foster, 1977). Insulin suppresses adipose tissue lipolysis, thus depriving ketogenesis of its substrate, while glucagon increases ketogenic flux though a direct effect on the liver (Hegardt, 1999). Hmgcs2 transcription is stimulated by forkhead transcriptional factor FOXA2, which is inhibited via insulin-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt, and is induced by glucagon-cAMP-p300 signaling (Arias et al., 1995; Hegardt, 1999; Quant et al., 1990; Thumelin et al., 1993; von Meyenn et al., 2013; Wolfrum et al., 2004; Wolfrum et al., 2003). PPARα (Rodriguez et al., 1994) together with its target, FGF21 (Badman et al., 2007) also induce Hmgcs2 transcription in the liver during starvation or administration of ketogenic diet (Badman et al., 2007; Inagaki et al., 2007). Induction of PPARα may occur before the transition from fetal to neonatal physiology, while FGF21 activation may be favored in the early neonatal period via βOHB-mediated inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC)-3 (Rando et al., 2016). mTORC1 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1) dependent inhibition of PPARα transcriptional activity is also a key regulator of Hmgcs2 gene expression (Sengupta et al., 2010), and liver PER2, a master circadian oscillator, indirectly regulates Hmgcs2 expression (Chavan et al., 2016). Recent observations indicate that extrahepatic tumor-induced interleukin-6 impairs ketogenesis via PPARα suppression (Flint et al., 2016). Despite these observations, it is important to note that physiological shifts in Hmgcs2 gene expression have not been mechanistically linked to HMGCS2 protein abundance or to variations of ketogenic rate.

HMGCS2 enzyme activity is regulated through multiple PTMs. HMGCS2 serine phosphorylation enhanced its activity in vitro (Grimsrud et al., 2012). HMGCS2 activity is allosterically inhibited by succinyl-CoA and lysine residue succinylation (Arias et al., 1995; Hegardt, 1999; Lowe and Tubbs, 1985; Quant et al., 1990; Rardin et al., 2013; Reed et al., 1975; Thumelin et al., 1993). Succinylation of HMGCS2, HMGCL, and BDH1 lysine residues in hepatic mitochondria are targets of the NAD+ dependent deacylase sirtuin 5 (SIRT5) (Rardin et al., 2013). HMGCS2 activity is also enhanced by SIRT3 lysine deacetylation, and it is possible that crosstalk between acetylation and succinylation regulates HMGCS2 activity (Rardin et al., 2013; Shimazu et al., 2013). Despite the ability of these PTMs to regulate HMGCS2 Km and Vmax, fluctuations of these PTMs have not yet been carefully mapped and have not been confirmed as mechanistic drivers of ketogenesis in vivo.

SCOT is expressed in all mammalian cells that harbor mitochondria, except those of hepatocytes. The importance of SCOT activity and ketolysis was demonstrated in SCOT-KO mice, which exhibited uniform lethality due to hyperketonemic hypoglycemia within 48h after birth (Cotter et al., 2011). Tissue-specific loss of SCOT in neurons or skeletal myocytes induces metabolic abnormalities during starvation but is not lethal (Cotter et al., 2013b). In humans, SCOT deficiency presents early in life with severe ketoacidosis, causing lethargy, vomiting, and coma (Berry et al., 2001; Fukao et al., 2000; Kassovska-Bratinova et al., 1996; Niezen-Koning et al., 1997; Saudubray et al., 1987; Snyderman et al., 1998; Tildon and Cornblath, 1972). Relatively little is known at the cellular level about SCOT gene and protein expression regulators. Oxct1 mRNA expression and SCOT protein and activity are diminished in ketotic states, possibly through PPAR-dependent mechanisms (Fenselau and Wallis, 1974; Fenselau and Wallis, 1976; Grinblat et al., 1986; Okuda et al., 1991; Turko et al., 2001; Wentz et al., 2010). In diabetic ketoacidosis, the mismatch between hepatic ketogenesis and extrahepatic oxidation becomes exacerbated by impairment of SCOT activity. Overexpression of insulin independent glucose transporter (GLUT1/SLC2A1) in cardiomyocytes also inhibits Oxct1 gene expression and downregulates ketones terminal oxidation in a non-ketotic state (Yan et al., 2009). In liver, Oxct1 mRNA abundance is suppressed by microRNA-122 and histone methylation H3K27me3 that are evident during the transition from fetal to the neonatal period (Thorrez et al., 2011). However, suppression of hepatic Oxct1 expression in the postnatal period is primarily attributable to the evacuation of Oxct1-expressing hematopoietic progenitors from the liver, rather than a loss of previously existing Oxct1 expression in terminally differentiated hepatocytes. In fact, expression of Oxct1 mRNA and SCOT protein in differentiated hepatocytes are extremely low (Orii et al., 2008).

SCOT is also regulated by PTMs. The enzyme is hyper-acetylated in brains of SIRT3 KO mice, which also exhibit diminished AcAc dependent acetyl-CoA production (Dittenhafer-Reed et al., 2015). Non-enzymatic nitration of tyrosine residues of SCOT also attenuates its activity, which has been reported in hearts of various diabetic mice models (Marcondes et al., 2001; Turko et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2010a). In contrast, tryptophan residue nitration augments SCOT activity (Brégère et al., 2010; Rebrin et al., 2007). Molecular mechanisms of residue-specific nitration or de-nitration designed to modulate SCOT activity may exist and require elucidation.

Controversies in extrahepatic ketogenesis

In mammals the primary ketogenic organ is liver, and only hepatocytes and gut epithelial cells abundantly express the mitochondrial isoform of HMGCS2 (Cotter et al., 2013a; Cotter et al., 2014; McGarry and Foster, 1980; Robinson and Williamson, 1980). Anaerobic bacterial fermentation of complex polysaccharides yields butyrate, which is absorbed by colonocytes in mammalians for terminal oxidation or ketogenesis (Cherbuy et al., 1995), which may play a role in colonocyte differentiation (Wang et al., 2016). Excluding gut epithelial cells and hepatocytes, HMGCS2 is nearly absent in almost all other mammalian cells, but the prospect of extrahepatic ketogenesis has been raised in tumor cells, astrocytes of the central nervous system, the kidney, pancreatic β cells, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and even in skeletal muscle (Adijanto et al., 2014; Avogaro et al., 1992; El Azzouny et al., 2016; Grabacka et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2015; Le Foll et al., 2014; Nonaka et al., 2016; Takagi et al., 2016a; Thevenet et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2011). Ectopic HMGCS2 has been observed in tissues that lack net ketogenic capacity (Cook et al., 2016; Wentz et al., 2010), and HMGCS2 exhibits prospective ketogenesis-independent ‘moonlighting’ activities, including within the cell nucleus (Chen et al., 2016; Kostiuk et al., 2010; Meertens et al., 1998).

Any extrahepatic tissue that oxidizes ketone bodies also has the potential to accumulate ketone bodies via HMGCS2 independent mechanisms (Fig. 2A). However, there is no extrahepatic tissue in which a steady state ketone body concentration exceeds that in the circulation (Cotter et al., 2011; Cotter et al., 2013b; Harrison and Long, 1940), underscoring that ketone bodies are transported down a concentration gradient via MCT1/2-dependent mechanisms. One mechanism of apparent extrahepatic ketogenesis may actually reflect relative impairment of ketone oxidation. Additional potential explanations fall within the realm of ketone body formation. First, de novo ketogenesis may occur via reversible enzymatic activity of thiolase and SCOT (Weidemann and Krebs, 1969). When the concentration of acetyl-CoA is relatively high, reactions normally responsible for AcAc oxidation operate in the reverse direction (GOLDMAN, 1954). A second mechanism occurs when β-oxidation-derived intermediates accumulate due to a TCA cycle bottleneck, AcAc-CoA is converted to l-βOHB-CoA through a reaction catalyzed by mitochondrial 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, and further by 3-hydroxybutyryl CoA deacylase to l-βOHB, which is indistinguishable by mass spectrometry or resonance spectroscopy from the physiological enantiomer d-βOHB (Reed and Ozand, 1980). l-βOHB can be chromatographically or enzymatically distinguished from d-βOHB, and is present in extrahepatic tissues, but not in liver or blood (Hsu et al., 2011). Hepatic ketogenesis produces only d-βOHB, the only enantiomer that is a BDH substrate (Ito et al., 1984; Lincoln et al., 1987; Reed and Ozand, 1980; Scofield et al., 1982; Scofield et al., 1982). A third HMGCS2-independent mechanism generates d-βOHB through amino acid catabolism, particularly that of leucine and lysine. A fourth mechanism is only apparent because it is due to a labeling artifact and is thus termed pseudoketogenesis. This phenomenon is attributable to the reversibility of the SCOT and thiolase reactions, and can cause overestimation of ketone body turnover due to the isotopic dilution of ketone body tracer in extrahepatic tissue (Des Rosiers et al., 1990; Fink et al., 1988). Nonetheless, pseudoketogenesis may be negligible in most contexts (Bailey et al., 1990; Keller et al., 1978). A schematic (Fig. 2A) indicates a useful approach to apply while considering elevated tissue steady state concentration of ketones.

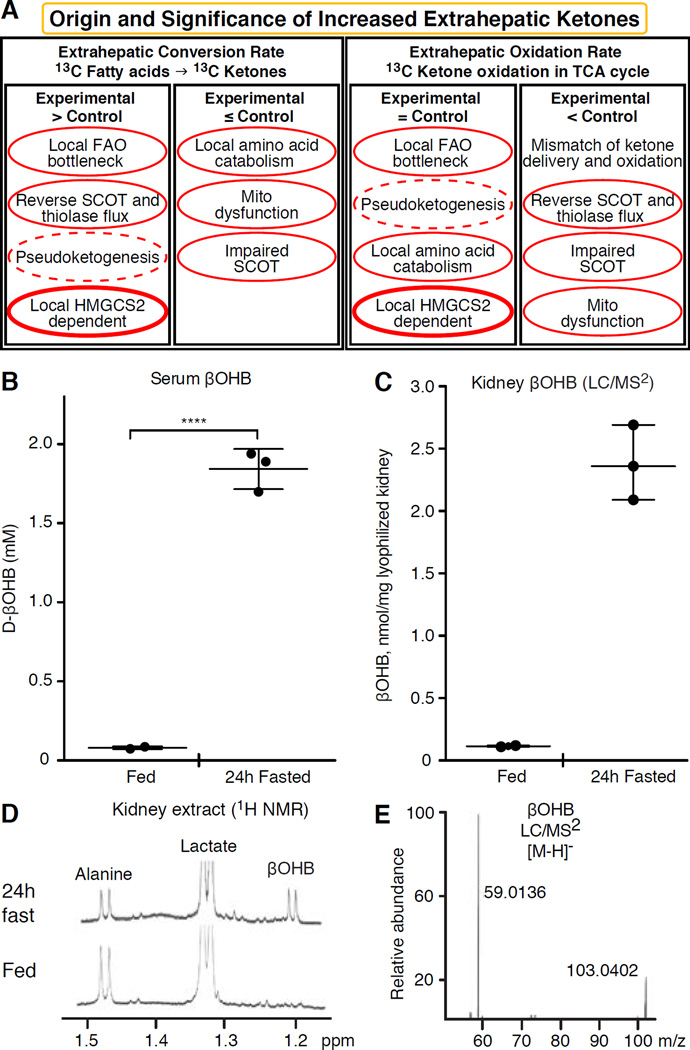

Fig. 2. Evaluation of extrahepatic ketone body concentrations.

(A) Increased steady state abundance of ketone bodies in one biological condition versus another may indicate local ketogenesis, but other interpretations are possible, including selective impairment of ketone oxidation, or global impairment of mitochondrial oxidative function. Experiments that employ isotopically labeled ketone bodies and fatty acids, specifically tracking the fate of the labeled intermediates, are often reliable approaches to demonstrate ketogenesis. Pseudoketogenesis is isotopic dilution without true ketone production, dashed elliptical line. SCOT function can be selectively inhibited by diminished expression or PTM. The SCOT and thiolase reactions are reversible, and can thus support either true ketogenesis or pseudoketogenesis. Only HMGCS2 dependent ketogenesis can support millimolar ketone accumulation (thick elliptical line). Results not clearly circumscribed by this analysis likely indicate that a difference in tissue ketone concentration is attributable to variations of hepatic ketogenesis. (B–E) Extrahepatic tissue ketone concentrations do not exceed that in the circulation. Ten week-old female C57BL/6 mice were bled, and kidneys were harvested in the random fed and 24h fasted states. All measurements (n=3/group) were performed in blinded manner. (B) βOHB concentrations were quantified in serum using standard biochemical enzymatic reagents coupled to a spectrophotometrically-coupled substrate (Wako). βOHB concentrations were also quantified in kidney from fed or 24h fasted mice by (C) LC/MS2 or (D) 1H NMR. For LC/MS2, two milligrams of lyophilized and homogenized kidney powder were extracted using optimized protocol in cold (−20°C) 2:2:1 methanol: acetonitrile: water containing sodium β-[U-13C]hydroxybutyrate as an internal standard. Quantitation was performed on Dionex 3000 RS liquid chromatography stack coupled to a Thermo Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer. Separation was optimized on a Phenomenex Luna NH2 column in hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography mode. Spectrometer was operated in negative Parallel Reaction Mode and MS resolution was set to 17,500. βOHB and its internal standard were quantified using expected m/z transitions of (E) 103.0401 → 59.0133 and 107.0535 → 61.0200 (internal standard’s transition not shown), respectively, with less than 10 ppm mass accuracy. NMR spectra were collected at 25°C in D2O from perchloric acid extracts of a single snap frozen kidney harvested from fed (bottom) and 24h fasted (top) mice. Data were collected under quantitative steady state conditions using a cryoprobe at 14.1T (Bruker) using trimethylsilylpropionate as an internal chemical shift and concentration reference. Chemical shifts corresponding to renal alanine, lactate, and βOHB are shown. Calculated mean renal βOHB concentrations were 0.08 nmol/mg wet tissue in the fed state, and 0.93 nmol/mg wet tissue in the 24h fasted state. Note that higher apparent βOHB concentrations were quantified via LC/MS2, compared to those derived from NMR-based measurements, due to the use of dry versus wet kidney tissue, respectively.

Kidney has recently received attention as a potentially ketogenic organ. In the vast majority of states, the kidney is a net consumer of liver-derived ketone bodies, excreting or reabsorbing ketone bodies from the bloodstream, and kidney is generally not a net ketone body generator or concentrator (Robinson and Williamson, 1980). The authors of a classical study concluded that minimal renal ketogenesis quantified in an artificial experimental system was not physiologically relevant (Weidemann and Krebs, 1969). Recently, renal ketogenesis has been inferred in diabetic and autophagy deficient mouse models, but it is more likely that multi-organ shifts in metabolic homeostasis alter integrative ketone metabolism through inputs on multiple organs (Takagi et al., 2016a; Takagi et al., 2016b; Zhang et al., 2011). One recent publication suggested renal ketogenesis as a protective mechanism against ischemia-reperfusion injury in the kidney (Tran et al., 2016). Absolute steady state concentrations of βOHB from extracts of mice renal tissue were reported at ~4–12 mM. To test whether this was tenable, we quantified βOHB concentrations in renal extracts from fed and 24h fasted mice. Serum βOHB concentrations increased from ~100 µM to 2 mM with 24h fasting (Fig. 2B), while renal steady state βOHB concentrations approximate 100 µM in the fed state, and only 1 mM in the 24h fasted state (Fig. 2C–E), observations that are consistent with concentrations quantified over 45 years ago (Hems and Brosnan, 1970). It remains possible that in ketotic states, liver-derived ketone bodies could be renoprotective, but evidence for renal ketogenesis requires further substantiation. Compelling evidence that supports true extrahepatic ketogenesis was presented in RPE (Adijanto et al., 2014). This intriguing metabolic transformation was suggested to potentially allow RPE-derived ketones to flow to photoreceptor or Müller glia cells, which could aid in the regeneration of photoreceptor outer segment.

βOHB as a signaling mediator

Although they are energetically rich, ketone bodies exert provocative ‘non-canonical’ signaling roles in cellular homeostasis (Fig. 3) (Newman and Verdin, 2014; Rojas-Morales et al., 2016). For example, βOHB inhibits Class I HDACs, which increases histone acetylation and thereby induces the expression of genes that curtail oxidative stress (Shimazu et al., 2013). βOHB itself is a histone covalent modifier at lysine residues in livers of fasted or streptozotocin induced diabetic mice (Xie et al., 2016) (also see below, The integration of ketone body metabolism, post-translational modification, and cell physiology, and Ketone bodies, oxidative stress, and neuroprotection).

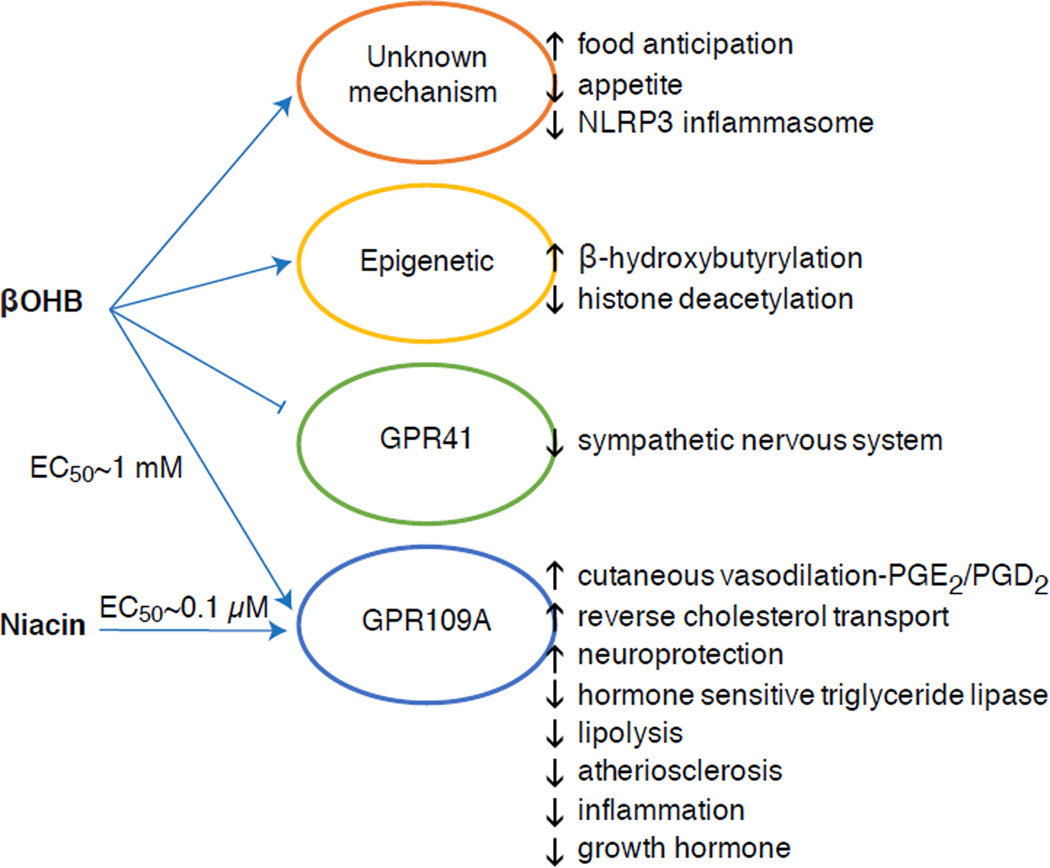

Fig. 3. Non-canonical signaling roles for βOHB.

Pleiotropic effects have been observed. Mechanisms of action still require elucidation for many of the observed effects, and ideal experiments discriminate among d-βOHB, l-βOHB, AcAc, and related compounds including butyrate and acetate, and the potential role of altered redox potential and oxidative fate. NLRP3, NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3; PGE2/PGD2, prostaglandins E2/D2.

βOHB is also an effector via G-protein coupled receptors. Through unclear molecular mechanisms, it suppresses sympathetic nervous system activity and reduces total energy expenditure and heart rate by inhibiting short chain fatty acid signaling through G protein coupled receptor 41 (GPR41) (Kimura et al., 2011). One of the most studied signaling effects of βOHB proceeds through GPR109A (also known as HCAR2), a member of the hydrocarboxylic acid GPCR sub-family expressed in adipose tissues (white and brown) (Tunaru et al., 2003), and in immune cells (Ahmed et al., 2009). βOHB is the only known endogenous ligand of GPR109A receptor (EC50 ~770 µM) activated by d-βOHB, l-βOHB, and butyrate, but not AcAc (Taggart et al., 2005). The high concentration threshold for GPR109A activation is achieved through adherence to a ketogenic diet, starvation, or during ketoacidosis, leading to inhibition of adipose tissue lipolysis. The anti-lipolytic effect of GPR109A proceeds though inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and decreased cAMP, inhibiting hormone sensitive triglyceride lipase (Ahmed et al., 2009; Tunaru et al., 2003). This creates a negative feedback loop in which ketosis places a modulatory brake on ketogenesis by diminishing the release of non-esterified fatty acids from adipocytes (Ahmed et al., 2009; Taggart et al., 2005), an effect that can be counterbalanced by the sympathetic drive that stimulates lipolysis. Niacin (vitamin B3, nicotinic acid) is a potent (EC50 ~ 0.1 µM) ligand for GRP109A, effectively employed for decades for dyslipidemias (Benyo et al., 2005; Benyo et al., 2006; Fabbrini et al., 2010a; Lukasova et al., 2011; Tunaru et al., 2003). While niacin enhances reverse cholesterol transport in macrophages and reduces atherosclerotic lesions (Lukasova et al., 2011), the effects of βOHB on atherosclerotic lesions remain unknown. Although GPR109A receptor exerts protective roles, and intriguing connections exist between ketogenic diet use in stroke and neurodegenerative diseases (Fu et al., 2015; Rahman et al., 2014), a protective role of βOHB via GPR109A has not been demonstrated in vivo.

Finally, βOHB may influence appetite and satiety. A meta-analysis of studies that measured the effects of ketogenic and very low energy diets concluded that participants consuming these diets exhibit higher satiety, compared to control diets (Gibson et al., 2015). However, a plausible explanation for this effect is the additional metabolic or hormonal elements that might modulate appetite. For example, mice maintained on a rodent ketogenic diet exhibited increased energy expenditure compared to chow control-fed mice, despite similar caloric intake, and circulating leptin or genes of peptides regulating feeding behavior were not changed (Kennedy et al., 2007). Among proposed mechanisms that suggest appetite suppression by βOHB includes both signaling and oxidation (Laeger et al., 2010). Hepatocyte specific deletion of circadian rhythm gene (Per2), and chromatin immunoprecipitation studies revealed that PER2 directly activates the Cpt1a gene, and indirectly regulates Hmgcs2, together leading to impaired ketosis in Per2 knockout mice (Chavan et al., 2016). These mice exhibited impaired food anticipation, which was partially restored by systemic βOHB administration. Future studies will be needed to confirm the central nervous system as a direct βOHB target, and whether ketone oxidation is required for the observed effects, or whether another signaling mechanism is involved. Other investigators have invoked the possibility of local astrocyte-derived ketogenesis within the ventromedial hypothalamus as a regulator of food intake, but these preliminary observations also will benefit from genetic and flux-based assessments (Le Foll et al., 2014). The relationship between ketosis and nutrient deprivation remains of interest because hunger and satiety are important elements in failed weight loss attempts.

Integration of ketone body metabolism, post-translational modification, and cell physiology

Ketone bodies contribute to compartmentalized pools of acetyl-CoA, a key intermediate that exhibits prominent roles in cellular metabolism (Pietrocola et al., 2015). One role of acetyl-CoA is to serve as a substrate for acetylation, an enzymatically-catalyzed histone covalent modification (Choudhary et al., 2014; Dutta et al., 2016; Fan et al., 2015; Menzies et al., 2016). A large number of dynamically acetylated mitochondrial proteins, many of which may occur through non-enzymatic mechanisms, have also emerged from computational proteomics studies (Dittenhafer-Reed et al., 2015; Hebert et al., 2013; Rardin et al., 2013; Shimazu et al., 2010). Lysine deacetylases use a zinc cofactor (e.g., nucleocytosolic HDACs) or NAD+ as co-substrate (sirtuins, SIRTs) (Choudhary et al., 2014; Menzies et al., 2016). The acetylproteome serves as both sensor and effector of the total cellular acetyl-CoA pool, as physiological and genetic manipulations each result in non-enzymatic global variations of acetylation (Weinert et al., 2014). As intracellular metabolites serve as modulators of lysine residue acetylation, it is important to consider the role of ketone bodies, whose abundance is highly dynamic.

βOHB is an epigenetic modifier through at least two mechanisms. Increased βOHB levels induced by fasting, caloric restriction, direct administration or prolonged exercise provoke HDAC inhibition or histone acetyltransferase activation (Marosi et al., 2016; Sleiman et al., 2016) or to oxidative stress (Shimazu et al., 2013). βOHB inhibition of HDAC3 could regulate newborn metabolic physiology (Rando et al., 2016). Independently, βOHB itself directly modifies histone lysine residues (Xie et al., 2016). Prolonged fasting, or steptozotocin-induced diabetic ketoacidosis increased histone β-hydroxybutyrylation. Although the number of lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation and acetylation sites was comparable, stoichiometrically greater histone β-hydroxybutyrylation than acetylation was observed. Distinct genes were impacted by histone lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation, versus acetylation or methylation, suggesting distinct cellular functions. Whether β-hydroxybutyrylation is spontaneous or enzymatic is not known, but expands the range of mechanisms through ketone bodies dynamically influence transcription.

Essential cell reprogramming events during caloric restriction and nutrient deprivation may be mediated in SIRT3- and SIRT5-dependent mitochondrial deacetylation and desuccinylation, respectively, regulating ketogenic and ketolytic proteins at post-translational level in liver and extrahepatic tissues (Dittenhafer-Reed et al., 2015; Hebert et al., 2013; Rardin et al., 2013; Shimazu et al., 2010). Even though stoichiometric comparison of occupied sites does not necessarily link directly to shifts in metabolic flux, mitochondrial acetylation is dynamic and may be driven by acetyl-CoA concentration or mitochondrial pH, rather than enzymatic acetyltransferases (Wagner and Payne, 2013). That SIRT3 and SIRT5 modulate activities of ketone body metabolizing enzymes provokes the question of the reciprocal role of ketones in sculpting the acetylproteome, succinylproteome, and other dynamic cellular targets. Indeed, as variations of ketogenesis reflect NAD+ concentrations, ketone production and abundance could regulate sirtuin activity, thereby influencing total acetyl-CoA/succinyl-CoA pools, the acylproteome, and thus mitochondrial and cell physiology. β-hydroxybutyrylation of enzyme lysine residues could add another layer to cellular reprogramming. In extrahepatic tissues, ketone body oxidation may stimulate analogous changes in cell homeostasis. While compartmentation of acetyl-CoA pools is highly regulated and coordinates a broad spectrum of cellular changes, the ability of ketone bodies to directly shape both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA concentrations requires elucidation (Chen et al., 2012; Corbet et al., 2016; Pougovkina et al., 2014; Schwer et al., 2009; Wellen and Thompson, 2012). Because acetyl-CoA concentrations are tightly regulated, and acetyl-CoA is membrane impermeant, it is crucial to consider the driver mechanisms coordinating acetyl-CoA homeostasis, including the rates of production and terminal oxidation in the TCA cycle, conversion into ketone bodies, mitochondrial efflux via carnitine acetyltransferase (CrAT), or acetyl-CoA export to cytosol after conversion to citrate and release by ATP citrate lyase (ACLY). The key roles of these latter mechanisms in cell acetylproteome and homeostasis require matched understanding of the roles of ketogenesis and ketone oxidation (Das et al., 2015; McDonnell et al., 2016; Moussaieff et al., 2015; Overmyer et al., 2015; Seiler et al., 2014; Seiler et al., 2015; Wellen et al., 2009; Wellen and Thompson, 2012). Convergent technologies in metabolomics and acylproteomics in the setting of genetically manipulated models will be required to specify targets and outcomes.

Anti- and pro-inflammatory responses to ketone bodies

Ketosis and ketone bodies modulate inflammation and immune cell function, but varied and even discrepant mechanisms have been posed. Prolonged nutrient deprivation reduces inflammation (Youm et al., 2015), but the chronic ketosis of type 1 diabetes is a pro-inflammatory state (Jain et al., 2002; Kanikarla-Marie and Jain, 2015; Kurepa et al., 2012). Mechanism-based signaling roles for βOHB in inflammation emerge because many immune system cells, including macrophages or monocytes, abundantly express GPR109A. While βOHB exerts a predominantly anti-inflammatory response (Fu et al., 2014; Gambhir et al., 2012; Rahman et al., 2014; Youm et al., 2015), high concentrations of ketone bodies, particularly AcAc, may trigger a pro-inflammatory response (Jain et al., 2002; Kanikarla-Marie and Jain, 2015; Kurepa et al., 2012).

Anti-inflammatory roles of GPR109A ligands in atherosclerosis, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, neurological disease, and cancer have been reviewed (Graff et al., 2016). GPR109A expression is augmented in RPE cells of diabetic models, human diabetic patients (Gambhir et al., 2012), and in microglia during neurodegeneration (Fu et al., 2014). Anti-inflammatory effects of βOHB are enhanced by GPR109A overexpression in RPE cells, and abrogated by pharmacological inhibition or genetic knockout of GPR109A (Gambhir et al., 2012). βOHB and exogenous nicotinic acid (Taggart et al., 2005), both confer anti-inflammatory effects in TNFα or LPS-induced inflammation by decreasing the levels of pro-inflammatory proteins (iNOS, COX-2), or secreted cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2/MCP-1), in part through inhibiting NF-κB translocation (Fu et al., 2014; Gambhir et al., 2012). βOHB decreases ER stress and the NLRP3 inflammasome, activating the antioxidative stress response (Bae et al., 2016; Youm et al., 2015). However, in neurodegenerative inflammation, GPR109A-dependent βOHB-mediated protection does not involve inflammatory mediators like MAPK pathway signaling (e.g., ERK, JNK, p38) (Fu et al., 2014), but may require COX-1-dependent PGD2 production (Rahman et al., 2014). It is intriguing that macrophage GPR109A is required to exert a neuroprotective effect in an ischemic stroke model (Rahman et al., 2014), but the ability of βOHB to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome in bone marrow derived macrophages is GPR109A independent (Youm et al., 2015). Although most studies link βOHB to anti-inflammatory effects, βOHB may be pro-inflammatory and increase markers of lipid peroxidation in calf hepatocytes (Shi et al., 2014). Anti- versus pro- inflammatory effects of βOHB may thus depend on cell type, βOHB concentration, exposure duration, and the presence or absence of co-modulators.

Unlike βOHB, AcAc may activate pro-inflammatory signaling. Elevated AcAc, especially with a high glucose concentration, intensifies endothelial cell injury through an NADPH oxidase/oxidative stress dependent mechanism (Kanikarla-Marie and Jain, 2015). High AcAc concentrations in umbilical cord of diabetic mothers were correlated with higher protein oxidation rate and MCP-1 concentration (Kurepa et al., 2012). High AcAc in diabetic patients was correlated with TNFα expression (Jain et al., 2002), and AcAc, but not βOHB, induced TNFα, MCP-1 expression, ROS accumulation, and diminished cAMP level in U937 human monocyte cells (Jain et al., 2002; Kurepa et al., 2012).

Ketone body dependent signaling phenomena are frequently triggered only with high ketone body concentrations (> 5 mM), and in the case of many studies linking ketones to pro- or anti-inflammatory effects, through unclear mechanisms. In addition, due to the contradictory effects of βOHB versus AcAc on inflammation, and the ability of AcAc/βOHB ratio to influence mitochondrial redox potential, the best experiments assessing the roles of ketone bodies on cellular phenotypes compare the effects of AcAc and βOHB in varying ratios, and at varying cumulative concentrations [e.g., (Saito et al., 2016)]. Finally, AcAc can be purchased commercially only as a lithium salt or as an ethyl ester that requires base hydrolysis before use. Lithium cation independently induces signal transduction cascades (Manji et al., 1995), and AcAc anion is labile. Finally, studies using racemic d/l-βOHB can be confounded, as only the d-βOHB stereoisomer can be oxidized to AcAc, but d-βOHB and l-βOHB can each signal through GPR109A, inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome, and serve as lipogenic substrates.

Ketone bodies, oxidative stress, and neuroprotection

Oxidative stress is typically defined as a state in which ROS are presented in excess, due to excessive production and/or impaired elimination. Antioxidant and oxidative stress mitigating roles of ketone bodies have been widely described both in vitro and in vivo, particularly in the context of neuroprotection. As most neurons do not effectively generate high-energy phosphates from fatty acids, but do oxidize ketone bodies when carbohydrates are in short supply, neuroprotective effects of ketone bodies are especially important (Cahill GF Jr, 2006; Edmond et al., 1987; Yang et al., 1987). In oxidative stress models, BDH1 induction and SCOT suppression suggest that ketone body metabolism can be reprogrammed to sustain diverse cell signaling, redox potential, or metabolic requirements (Nagao et al., 2016; Tieu et al., 2003).

Ketone bodies decrease the grades of cellular damage, injury, death and lower apoptosis in neurons and cardiomyocytes (Haces et al., 2008; Maalouf et al., 2007; Nagao et al., 2016; Tieu et al., 2003). Invoked mechanisms are varied and not always linearly related to concentration. Low millimolar concentrations of (d or l)-βOHB scavenge ROS (hydroxyl anion), while AcAc scavenges numerous ROS species, but only at concentrations that exceed the physiological range (IC50 20–67 mM) (Haces et al., 2008). Conversely, a beneficial influence over the electron transport chain’s redox potential is a mechanism commonly linked to d-βOHB. While all three ketone bodies (d/l-βOHB and AcAc) reduced neuronal cell death and ROS accumulation triggered by chemical inhibition of glycolysis, only d-βOHB and AcAc prevented neuronal ATP decline. Conversely, in a hypoglycemic in vivo model, (d or l)-βOHB, but not AcAc prevented hippocampal lipid peroxidation (Haces et al., 2008; Maalouf et al., 2007; Marosi et al., 2016; Murphy, 2009; Tieu et al., 2003). In vivo studies of mice fed a ketogenic diet (87% kcal fat and 13% protein) exhibited neuroanatomical variation of antioxidant capacity (Ziegler et al., 2003), where the most profound changes were observed in hippocampus, with increase glutathione peroxidase and total antioxidant capacities.

Ketogenic diet, ketone esters (also see Therapeutic use of ketogenic diet and exogenous ketone bodies), or βOHB administration exert neuroprotection in models of ischemic stroke (Rahman et al., 2014); Parkinson’s disease (Tieu et al., 2003); central nervous system oxygen toxicity seizure (D'Agostino et al., 2013); epileptic spasms (Yum et al., 2015); mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like (MELAS) episodes syndrome (Frey et al., 2016) and Alzheimer’s disease (Cunnane and Crawford, 2003; Yin et al., 2016). Conversely, a recent report demonstrated histopathological evidence of neurodegenerative progression by a ketogenic diet in a transgenic mouse model of abnormal mitochondrial DNA repair, despite increases in mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant signatures (Lauritzen et al., 2016). Other conflicting reports suggest that exposure to high ketone body concentrations elicits oxidative stress. High βOHB or AcAc doses induced nitric oxide secretion, lipid peroxidation, reduced expression of SOD, glutathione peroxidase and catalase in calf hepatocytes, while in rat hepatocytes the MAPK pathway induction was attributed to AcAc but not βOHB (Abdelmegeed et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2016).

Taken together, most reports link βOHB to attenuation of oxidative stress, as its administration inhibits ROS/superoxide production, prevents lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation, increases antioxidant protein levels, and improves mitochondrial respiration and ATP production (Abdelmegeed et al., 2004; Haces et al., 2008; Jain et al., 1998; Jain et al., 2002; Kanikarla-Marie and Jain, 2015; Maalouf et al., 2007; Maalouf and Rho, 2008; Marosi et al., 2016; Tieu et al., 2003; Yin et al., 2016; Ziegler et al., 2003). While AcAc has been more directly correlated than βOHB with the induction of oxidative stress, these effects are not always easily dissected from prospective pro-inflammatory responses (Jain et al., 2002; Kanikarla-Marie and Jain, 2015; Kanikarla-Marie and Jain, 2016). Moreover, it is critical to consider that the apparent antioxidative benefit conferred by pleiotropic ketogenic diets may not be transduced by ketone bodies themselves, and neuroprotection conferred by ketone bodies may not entirely be attributable to oxidative stress. For example during glucose deprivation, in a model of glucose deprivation in cortical neurons, βOHB stimulated autophagic flux and prevented autophagosome accumulation, which was associated with decreased neuronal death (Camberos-Luna et al., 2016). d-βOHB induces also the canonical antioxidant proteins FOXO3a, SOD, MnSOD, and catalase, prospectively through HDAC inhibition (Nagao et al., 2016; Shimazu et al., 2013).

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and ketone body metabolism

Obesity-associated NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are the most common causes of liver disease in Western countries (Rinella and Sanyal, 2016), and NASH-induced liver failure is one of the most common reasons for liver transplantation. While excess storage of triacylglycerols in hepatocytes >5% of liver weight (NAFL) alone does not cause degenerative liver function, the progression to NAFLD in humans correlates with systemic insulin resistance and increased risk of type 2 diabetes, and may contribute to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease (Fabbrini et al., 2009; Targher et al., 2010; Targher and Byrne, 2013). The pathogenic mechanisms of NAFLD and NASH are incompletely understood but include abnormalities of hepatocyte metabolism, hepatocyte autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress, hepatic immune cell function, adipose tissue inflammation, and systemic inflammatory mediators (Fabbrini et al., 2009; Masuoka and Chalasani, 2013; Targher et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010). Perturbations of carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism occur in and contribute to obesity, diabetes, and NAFLD in humans and in model organisms [reviewed in (Farese et al., 2012; Lin and Accili, 2011; Newgard, 2012; Samuel and Shulman, 2012; Sun and Lazar, 2013)]. While hepatocyte abnormalities in cytoplasmic lipid metabolism are commonly observed in NAFLD (Fabbrini et al., 2010b), the role of mitochondrial metabolism, which governs oxidative disposal of fats is less clear in NAFLD pathogenesis. Abnormalities of mitochondrial metabolism occur in and contribute to NAFLD/NASH pathogenesis (Hyotylainen et al., 2016; Serviddio et al., 2011; Serviddio et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2008). There is general (Felig et al., 1974; Iozzo et al., 2010; Koliaki et al., 2015; Satapati et al., 2015; Satapati et al., 2012; Sunny et al., 2011) but not uniform (Koliaki and Roden, 2013; Perry et al., 2016; Rector et al., 2010) consensus that, prior to the development of bona fide NASH, hepatic mitochondrial oxidation, and in particular fat oxidation, is augmented in obesity, systemic insulin resistance, and NAFLD. It is likely that as NAFLD progresses, oxidative capacity heterogenity, even among individual mitochondria, emerges, and ultimately oxidative function becomes impaired (Koliaki et al., 2015; Rector et al., 2010; Satapati et al., 2008; Satapati et al., 2012).

Ketogenesis is often used as a proxy for hepatic fat oxidation. Impairments of ketogenesis emerge as NAFLD progresses in animal models, and likely in humans. Through incompletely defined mechanisms, hyperinsulinemia suppresses ketogenesis, possibly contributing to hypoketonemia compared to lean controls (Bergman et al., 2007; Bickerton et al., 2008; Satapati et al., 2012; Soeters et al., 2009; Sunny et al., 2011; Vice et al., 2005). Nonetheless, the ability of circulating ketone body concentrations to predict NAFLD is controversial (Männistö et al., 2015; Sanyal et al., 2001). Robust quantitative magnetic resonance spectroscopic methods in animal models revealed increased ketone turnover rate with moderate insulin resistance, but decreased rates were evident with more severe insulin resistance (Satapati et al., 2012; Sunny et al., 2010). In obese humans with fatty liver, ketogenic rate is normal (Bickerton et al., 2008; Sunny et al., 2011), and hence, the rates of ketogenesis are diminished relative to the increased fatty acid load within hepatocytes. Consequently, β-oxidation-derived acetyl-CoA may be directed to terminal oxidation in the TCA cycle, increasing terminal oxidation, phosphoenolpyruvate-driven gluconeogenesis via anaplerosis/cataplerosis, and oxidative stress. Acetyl-CoA also possibly undergoes export from mitochondria as citrate, a precursor substrate for lipogenesis (Fig. 4) (Satapati et al., 2015; Satapati et al., 2012; Solinas et al., 2015). While ketogenesis becomes less responsive to insulin or fasting with prolonged obesity (Satapati et al., 2012), the underlying mechanisms and downstream consequences of this remain incompletely understood. Recent evidence indicates that mTORC1 suppresses ketogenesis in a manner that may be downstream of insulin signaling (Kucejova et al., 2016), which is concordant with the observations that mTORC1 inhibits PPARα-mediated Hmgcs2 induction (Sengupta et al., 2010) (also see Regulation of HMGCS2 and SCOT/OXCT1).

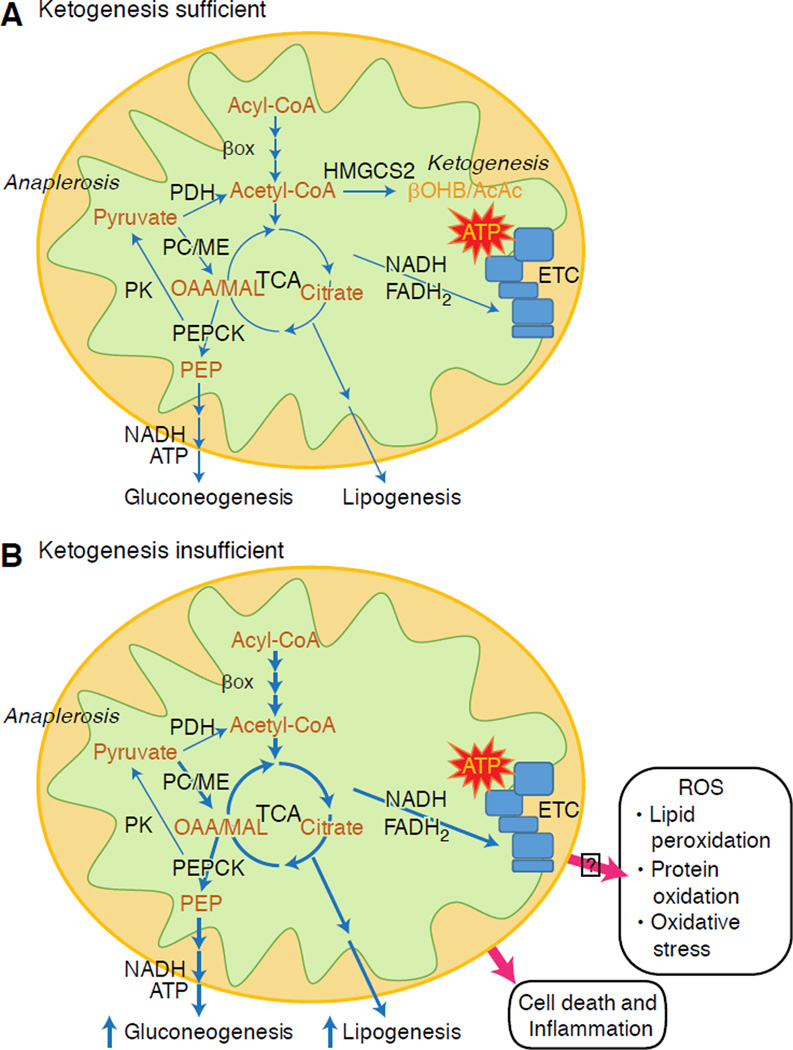

Fig. 4. Hepatic maladaptation to ketogenic insufficiency.

(A) Under homeostatic conditions, mitochondrial acetyl-CoA can be directed to ketogenesis, terminal oxidation in the TCA cycle, or exported to the cytoplasm for lipogenesis. (B) In the setting of ketogenic insufficiency, lipogenesis and glucose production are increased. Loss of the ketogenic conduit stimulates increased acetyl-CoA disposal through the TCA cycle prospectively increasing unsafe disposal of elections into reactive oxygen species. Ketogenic impairment also increases acetyl-CoA export to the cytoplasm for lipid-synthesizing pathways. These changes partly reflect the alterations encountered in NAFLD, in which the liver exhibits increased esterification to and lipolysis from lipid droplets, increased β-oxidation of fatty acids, increased terminal oxidation, and increased gluconeogenesis, but diminished ketogenesis relative to the availability of fat.

Preliminary observations from our group suggest adverse hepatic consequences of ketogenic insufficiency (Cotter et al., 2014). To test the hypothesis that impaired ketogenesis, even in carbohydrate-replete and thus ‘non-ketogenic’ states, contributes to abnormal glucose metabolism and provokes steatohepatitis, we generated a mouse model of marked ketogenic insufficiency by administration of antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) targeted to Hmgcs2. Loss of HMGCS2 in standard low fat chow-fed adult mice caused mild hyperglycemia and markedly increased production of hundreds of hepatic metabolites, a suite of which strongly suggested lipogenesis activation. High fat diet feeding of mice with insufficient ketogenesis resulted in extensive hepatocyte injury and inflammation. These findings support the central hypotheses that (i) ketogenesis is not a passive overflow pathway but rather a dynamic node in hepatic and integrated physiological homeostasis, and (ii) prudent ketogenic augmentation to mitigate NAFLD/NASH and disordered hepatic glucose metabolism is worthy of exploration.

How might impaired ketogenesis contribute to hepatic injury and altered glucose homeostasis? The first consideration is whether the culprit is deficiency of ketogenic flux, or ketones themselves. A recent report suggests that ketone bodies may mitigate oxidative stress-induced hepatic injury in response to n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (Pawlak et al., 2015). Recall that due to lack of SCOT expression in hepatocytes, ketone bodies are not oxidized, but they can contribute to lipogenesis, and serve a variety of signaling roles independent of their oxidation (also see Non-oxidative metabolic fates of ketone bodies and βOHB as a signaling mediator). It is also possible that hepatocyte-derived ketone bodies may serve as a signal and/or metabolite for neighboring cell types within the hepatic acinus, including stellate cells and Kupffer cell macrophages. While the limited literature available suggests that macrophages are unable to oxidize ketone bodies, this has only been measured using classical methodologies, and only in peritoneal macrophages (Newsholme et al., 1986; Newsholme et al., 1987), indicating that a re-assessment is appropriate given abundant SCOT expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages (Youm et al., 2015).

Hepatocyte ketogenic flux may also be cytoprotective. While salutary mechanisms may not depend on ketogenesis per se, low carbohydrate ketogenic diets have been associated with amelioration of NAFLD (Browning et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2010; Kani et al., 2014; Schugar and Crawford, 2012). Our observations indicate that hepatocyte ketogenesis may feedback and regulate TCA cycle flux, anaplerotic flux, phosphoenolpyruvate-derived gluconeogenesis (Cotter et al., 2014), and even glycogen turnover. Ketogenic impairment directs acetyl-CoA to increase TCA flux, which in liver has been linked to increased ROS-mediated injury (Satapati et al., 2015; Satapati et al., 2012); forces diversion of carbon into de novo synthesized lipid species that could prove cytotoxic; and prevents NADH re-oxidation to NAD+ (Cotter et al., 2014) (Fig. 4). Taken together, future experiments are required to address mechanisms through which relative ketogenic insufficiency may become maladaptive, contribute to hyperglycemia, provoke steatohepatitis, and whether these mechanisms are operant in human NAFLD/NASH. As epidemiological evidence suggests impaired ketogenesis during the progression of steatohepatitis (Embade et al., 2016; Marinou et al., 2011; Männistö et al., 2015; Pramfalk et al., 2015; Safaei et al., 2016) therapies that increase hepatic ketogenesis could prove salutary (Degirolamo et al., 2016; Honda et al., 2016).

Ketone bodies and heart failure (HF)

With a metabolic rate exceeding 400 kcal/kg/day, and a turnover of 6–35 kg ATP/day, the heart is the organ with the highest energy expenditure and oxidative demand (Ashrafian et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010b). The vast majority of myocardial energy turnover resides within mitochondria, and 70% of this supply originates from FAO. The heart is omnivorous and flexible under normal conditions, but the pathologically remodeling heart (e.g., due to hypertension or myocardial infarction) and the diabetic heart each become metabolically inflexible (Balasse and Fery, 1989; BING, 1954; Fukao et al., 2004; Lopaschuk et al., 2010; Taegtmeyer et al., 1980; Taegtmeyer et al., 2002; Young et al., 2002). Indeed, genetically programmed abnormalities of cardiac fuel metabolism in mouse models provoke cardiomyopathy (Carley et al., 2014; Neubauer, 2007). Under physiological conditions normal hearts oxidize ketone bodies in proportion to their delivery, at the expense of fatty acid and glucose oxidation, and myocardium is the highest ketone body consumer per unit mass (BING, 1954; Crawford et al., 2009; GARLAND et al., 1962; Hasselbaink et al., 2003; Jeffrey et al., 1995; Pelletier et al., 2007; Tardif et al., 2001; Yan et al., 2009). Compared to fatty acid oxidation, ketone bodies are more energetically efficient, yielding more energy available for ATP synthesis per molecule of oxygen invested (P/O ratio) (Kashiwaya et al., 2010; Sato et al., 1995; Veech, 2004). Ketone body oxidation also yields potentially higher energy than FAO, keeping ubiquinone oxidized, which raises redox span in the electron transport chain and makes more energy available to synthetize ATP (Sato et al., 1995; Veech, 2004). Oxidation of ketone bodies may also curtail ROS production, and thus oxidative stress (Veech, 2004).

Preliminary interventional and observational studies indicate a potential salutary role of ketone bodies in the heart. In the experimental ischemia/reperfusion injury context, ketone bodies conferred potential cardioprotective effects (Al-Zaid et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008), possibly due to the increase mitochondrial abundance in heart or up-regulation of crucial oxidative phosphorylation mediators (Snorek et al., 2012; Zou et al., 2002). Recent studies indicate that ketone body utilization is increased in failing hearts of mice (Aubert et al., 2016) and humans (Bedi et al., 2016), supporting prior observations in humans (BING, 1954; Fukao et al., 2000; Janardhan et al., 2011; Longo et al., 2004; Rudolph and Schinz, 1973; Tildon and Cornblath, 1972). Circulating ketone body concentrations are increased in heart failure patients, in direct proportion to filling pressures, observations whose mechanism and significance remains unknown (Kupari et al., 1995; Lommi et al., 1996; Lommi et al., 1997; Neely et al., 1972), but mice with selective SCOT deficiency in cardiomyocytes exhibit accelerated pathological ventricular remodeling and ROS signatures in response to surgically induced pressure overload injury (Schugar et al., 2014).

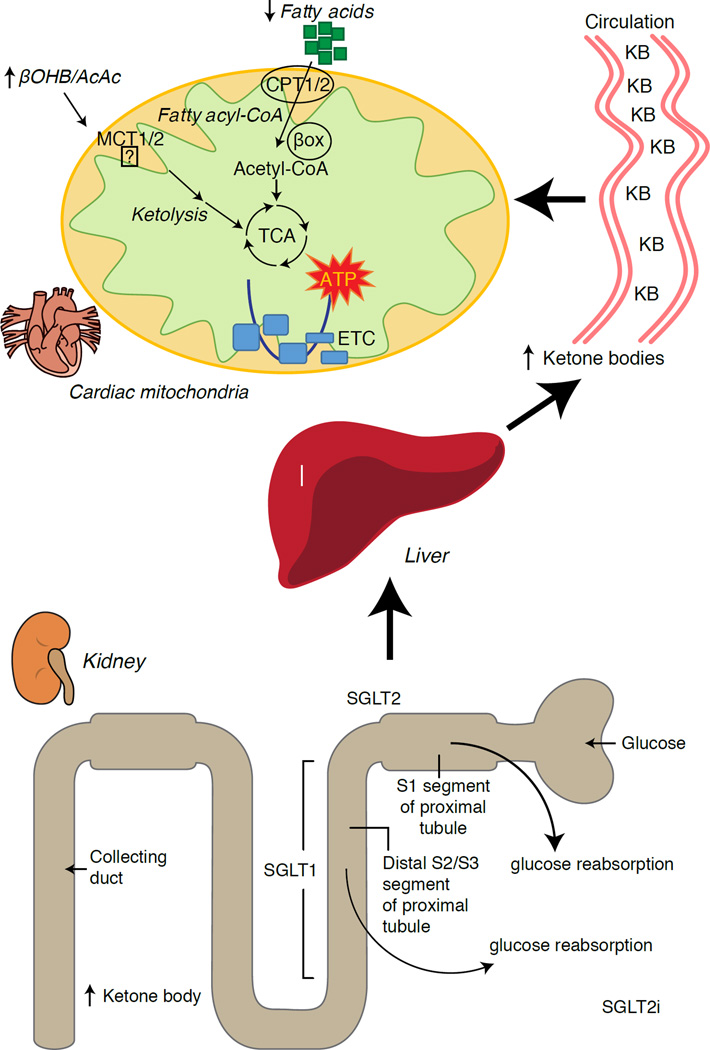

Recent intriguing observations in diabetes therapy have revealed a potential link between myocardial ketone metabolism and pathological ventricular remodeling (Fig. 5). Inhibition of the renal proximal tubular sodium/glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2i) increases circulating ketone body concentrations in humans (Ferrannini et al., 2016a; Inagaki et al., 2015) and mice (Suzuki et al., 2014) via increased hepatic ketogenesis (Ferrannini et al., 2014; Ferrannini et al., 2016a; Katz and Leiter, 2015; Mudaliar et al., 2015). Strikingly, at least one of these agents decreased HF hospitalization (e.g., as revealed by the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial), and improved cardiovascular mortality (Fitchett et al., 2016; Sonesson et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016a; Zinman et al., 2015). While the driver mechanisms behind beneficial HF outcomes to linked SGLT2i remain actively debated, the survival benefit is likely multifactorial, prospectively including ketosis but also salutary effects on weight, blood pressure, glucose and uric acid levels, arterial stiffness, the sympathetic nervous system, osmotic diuresis/reduced plasma volume, and increased hematocrit (Raz and Cahn, 2016; Vallon and Thomson, 2016). Taken together, the notion that therapeutically increasing ketonemia either in HF patients, or those at high risk to develop HF, remains controversial but is under active investigation in pre-clinical and clinical studies (Ferrannini et al., 2016b; Kolwicz et al., 2016; Lopaschuk and Verma, 2016; Mudaliar et al., 2016; Taegtmeyer, 2016).

Fig. 5. Prospective cardioprotection from ketone bodies.

The normal heart is omnvirous and flexible among substrate fuels, preferring fatty acids, but oxidizes ketones in proportion to their delivery at the expense of fatty acids. The failing heart becomes reprogrammed and inflexible, diminishing its use of fatty acids. Ketone bodies are mildly elevated in the circulation of human subjects and animal models of heart failure, and myocardial ketone body oxidation is increased. Renal SGLT2 inhibition, a therapy used to lower blood glucose concentrations in diabetics, also increases hepatic ketogenesis and ketonemia, and through unknown mechanisms, improves heart failure mortality rates. Prospective mechanisms that link further enhancement of myocardial ketone oxidation to protection from pathological ventricular remodeling are under investigation.

Ketone bodies in cancer biology

Connections between ketone bodies and cancer are rapidly emerging, but studies in both animal models and humans have yielded diverse conclusions. Because ketone metabolism is dynamic and nutrient state responsive, it is enticing to pursue biological connections to cancer because of the potential for precision-guided nutritional therapies. Cancer cells undergo metabolic reprogramming in order to maintain rapid cell proliferation and growth (DeNicola and Cantley, 2015; Pavlova and Thompson, 2016). The classical Warburg effect in cancer cell metabolism arises from the dominant role of glycolysis and lactic acid fermentation to transfer energy and compensate for lower dependence on oxidative phosphorylation and limited mitochondrial respiration (De Feyter et al., 2016; Grabacka et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2015; Poff et al., 2014; Shukla et al., 2014). Glucose carbon is primarily directed through glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and lipogenesis, which together provide intermediates necessary for tumor biomass expansion (Grabacka et al., 2016; Shukla et al., 2014; Yoshii et al., 2015). Adaptation of cancer cells to glucose deprivation occurs through the ability to exploit alternative fuel sources, including acetate, glutamine, and aspartate (Jaworski et al., 2016; Sullivan et al., 2015). For example, restricted access to pyruvate reveals the ability of cancer cells to convert glutamine into acetyl-CoA by carboxylation, maintaining both energetic and anabolic needs (Yang et al., 2014). An interesting adaptation of cancer cells is the utilization of acetate as a fuel (Comerford et al., 2014; Jaworski et al., 2016; Mashimo et al., 2014; Wright and Simone, 2016; Yoshii et al., 2015). Acetate is also a substrate for lipogenesis, which is critical for tumor cell proliferation, and gain of this lipogenic conduit is associated with shorter patient survival and greater tumor burden (Comerford et al., 2014; Mashimo et al., 2014; Yoshii et al., 2015).

Non-cancer cells easily shift their energy source from glucose to ketone bodies during glucose deprivation. This plasticity may be more variable among cancer cell types, but in vivo implanted brain tumors oxidized [2,4-13C2]-βOHB to a similar degree as surrounding brain tissue (De Feyter et al., 2016). ‘Reverse Warburg effect’ or ‘two compartment tumor metabolism’ models hypothesize that cancer cells induce βOHB production in adjacent fibroblasts, furnishing the tumor cell’s energy needs (Bonuccelli et al., 2010; Martinez-Outschoorn et al., 2012). In liver, a shift in hepatocytes from ketogenesis to ketone oxidation in hepatocellular carcinoma (hepatoma) cells is consistent with activation of BDH1 and SCOT activities observed in two hepatoma cell lines (Zhang et al., 1989). Indeed, hepatoma cells express OXCT1 and BDH1 and oxidize ketones, but only when serum starved (Huang et al., 2016). Alternatively, tumor cell ketogenesis has also been proposed. Dynamic shifts in ketogenic gene expression are exhibited during cancerous transformation of colonic epithelium, a cell type that normally expresses HMGCS2, and a recent report suggested that HMGCS2 may be a prognostic marker of poor prognosis in colorectal and squamous cell carcinomas (Camarero et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2016). Whether this association requires or involves ketogenesis, or a moonlighting function of HMGCS2, remains to be determined. Conversely, apparent βOHB production by melanoma and glioblastoma cells, stimulated by the PPARα agonist fenofibrate, was associated with growth arrest (Grabacka et al., 2016). Further studies are required to characterize roles of HMGCS2/SCOT expression, ketogenesis, and ketone oxidation in cancer cells.

Beyond the realm of fuel metabolism, ketones have recently been implicated in cancer cell biology via a signaling mechanism. Analysis of BRAF-V600E+ melanoma indicated OCT1-dependent induction of HMGCL in an oncogenic BRAF-dependent manner (Kang et al., 2015). HMGCL augmentation was correlated with higher cellular AcAc concentration, which in turn enhanced BRAFV600E-MEK1 interaction, amplifying MEK-ERK signaling in a feed-forward loop that drives tumor cell proliferation and growth. These observations raise the intriguing question of prospective extrahepatic ketogenesis that then supports a signaling mechanism (also see βOHB as a signaling mediator and Controversies in extrahepatic ketogenesis). It is also important to consider independent effects of AcAc, d-βOHB, and l-βOHB on cancer metabolism, and when considering HMGCL, leucine catabolism may also be deranged.

The effects of ketogenic diets (also see Therapeutic use of ketogenic diet and exogenous ketone bodies) in cancer animal models are varied (De Feyter et al., 2016; Klement et al., 2016; Meidenbauer et al., 2015; Poff et al., 2014; Seyfried et al., 2011; Shukla et al., 2014). While epidemiological associations among obesity, cancer, and ketogenic diets are debated (Liskiewicz et al., 2016; Wright and Simone, 2016), a meta-analysis using ketogenic diets in animal models and in human studies suggested a salutary impact on survival, with benefits prospectively linked to the magnitude of ketosis, time of diet initiation, and tumor location (Klement et al., 2016; Woolf et al., 2016). Treatment of pancreatic cancer cells with ketone bodies (d-βOHB or AcAc) inhibited growth, proliferation and glycolysis, and a ketogenic diet (81% kcal fat, 18% protein, 1% carbohydrate) reduced in vivo tumor weight, glycemia, and increased muscle and body weight in animals with implanted cancer (Shukla et al., 2014). Similar results were observed using a metastatic glioblastoma cell model in mice that received ketone supplementation in the diet (Poff et al., 2014). Conversely, a ketogenic diet (91% kcal fat, 9% protein) increased circulating βOHB concentration and diminished glycemia, but had no impact on either tumor volume or survival duration in glioma-bearing rats (De Feyter et al., 2016). A glucose ketone index has been proposed as a clinical indicator that improves metabolic management of ketogenic diet induced brain cancer therapy in humans and mice (Meidenbauer et al., 2015). Taken together, roles of ketone body metabolism and ketone bodies in cancer biology are tantalizing because they each pose tractable therapeutic options, but fundamental aspects remain to be elucidated, with clear influences emerging from a matrix of variables, including (i) differences between exogenous ketone bodies versus ketogenic diet, (ii) cancer cell type, genomic polymorphisms, grade, and stage; and (iii) timing and duration of exposure to the ketotic state.

Therapeutic application of ketogenic diet and exogenous ketone bodies

The applications of ketogenic diets and ketone bodies as therapeutic tools have also arisen in non-cancerous contexts including obesity and NAFLD/NASH (Browning et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2010; Schugar and Crawford, 2012); heart failure (Huynh, 2016; Kolwicz et al., 2016; Taegtmeyer, 2016); neurological and neurodegenerative disease (Martin et al., 2016; McNally and Hartman, 2012; Rho, 2015; Rogawski et al., 2016; Yang and Cheng, 2010; Yao et al., 2011); inborn errors of metabolism (Scholl-Bürgi et al, 2015); and exercise performance (Cox et al., 2016). The efficacy of ketogenic diets has been especially appreciated in therapy of epileptic seizure, particularly in drug-resistant patients. Most studies have evaluated ketogenic diets in pediatric patients, and reveal up to a ~50% reduction in seizure frequency after 3 months, with improved effectiveness in select syndromes (Wu et al., 2016b). The experience is more limited in adult epilepsy, but a similar reduction is evident, with better response in symptomatic generalized epilepsy patients (Nei et al., 2014). Underlying anti-convulsant mechanisms remain unclear, although postulated hypotheses include reduced glucose utilization/glycolysis, reprogrammed glutamate transport, indirect impact on ATP-sensitive potassium channel or adenosine A1 receptor, alteration of sodium channel isoform expression, or effects on circulating hormones including leptin (Lambrechts et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2017; Lutas and Yellen, 2013). It remains unclear whether the anti-convulsant effect is primarily attributable to ketone bodies, or due to the cascade metabolic consequences of low carbohydrate diets. Nonetheless, ketone esters (see below) appear to elevate the seizure threshold in animal models of provoked seizures (Ciarlone et al., 2016; D'Agostino et al., 2013; Viggiano et al., 2015).

Atkins-style and ketogenic, low carbohydrate diets are often deemed unpleasant, and can cause constipation, hyperuricemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, lead to nephrolithiasis, ketoacidosis, cause hyperglycemia, and raise circulating cholesterol and free fatty acid concentrations (Bisschop et al., 2001; Kossoff and Hartman, 2012; Kwiterovich et al., 2003; Suzuki et al., 2002). For these reasons, long-term adherence poses challenges. Rodent studies commonly use a distinctive macronutrient distribution (94% kcal fat, 1% kcal carbohydrate, 5% kcal protein, Bio-Serv F3666), which provokes a robust ketosis. However, increasing the protein content, even to 10% kcal substantially diminishes the ketosis, and 5% kcal protein restriction confers confounding metabolic and physiological effects. This diet formulation is also choline depleted, another variable that influences susceptibility to liver injury, and even ketogenesis (Garbow et al., 2011; Jornayvaz et al., 2010; Kennedy et al., 2007; Pissios et al., 2013; Schugar et al., 2013). Effects of long-term consumption of ketogenic diets in mice remain incompletely defined, but recent studies in mice revealed normal survival and the absence of liver injury markers in mice on ketogenic diets over their lifespan, although amino acid metabolism, energy expenditure, and insulin signaling were markedly reprogrammed (Douris et al., 2015).

Mechanisms increasing ketosis through mechanisms alternative to ketogenic diets include the use of ingestible ketone body precursors. Administration of exogenous ketone bodies could create a unique physiological state not encountered in normal physiology, because circulating glucose and insulin concentrations are relatively normal, while cells might spare glucose uptake and utilization. Ketone bodies themselves have short half-lives, and ingestion or infusion of sodium βOHB salt to achieve therapeutic ketosis provokes an untoward sodium load. R/S-1,3-butanediol is a non-toxic dialcohol that is readily oxidized in the liver to yield d/l-βOHB (Desrochers et al., 1992). In distinct experimental contexts, this dose has been administered daily to mice or rats for as long as seven weeks, yielding circulating βOHB concentrations of up to 5 mM within 2 h of administration, which is stable for at least an additional 3h (D'Agostino et al., 2013). Partial suppression of food intake has been observed in rodents given R/S-1,3-butanediol (Carpenter and Grossman, 1983). In addition, three chemically distinct ketone esters (KEs), (i) monoester of R-1,3-butanediol and d-βOHB (R-3-hydroxybutyl R-βOHB); (ii) glyceryl-tris-βOHB; and (iii) R,S-1,3-butanediol acetoacetate diester, have also been extensively studied (Brunengraber, 1997; Clarke et al., 2012a; Clarke et al., 2012b; Desrochers et al., 1995a; Desrochers et al., 1995b; Kashiwaya et al., 2010). An inherent advantage of the former is that 2 moles of physiological d-βOHB are produced per mole of KE, following esterase hydrolysis in the intestine or liver. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and tolerance have been most extensively studied in humans ingesting R-3-hydroxybutyl R-βOHB, at doses up to 714 mg/kg, yielding circulating d-βOHB concentrations up to 6 mM (Clarke et al., 2012a; Cox et al., 2016; Kemper et al., 2015; Shivva et al., 2016). In rodents, this KE decreases caloric intake and plasma total cholesterol, stimulates brown adipose tissue, and improves insulin resistance (Kashiwaya et al., 2010; Kemper et al., 2015; Veech, 2013). Recent findings indicate that during exercise in trained athletes, R-3-hydroxybutyl R-βOHB ingestion decreased skeletal muscle glycolysis and plasma lactate concentrations, increased intramuscular triacylglycerol oxidation, and preserved muscle glycogen content, even when co-ingested carbohydrate stimulated insulin secretion (Cox et al., 2016). Further development of these intriguing results is required, because the improvement in endurance exercise performance was predominantly driven by a robust response to the KE in 2/8 subjects. Nonetheless, these results do support classical studies that indicate a preference for ketone oxidation over other substrates (GARLAND et al., 1962; Hasselbaink et al., 2003; Stanley et al., 2003; Valente-Silva et al., 2015), including during exercise, and that trained athletes may be more primed to utilize ketones (Johnson et al., 1969a; Johnson and Walton, 1972; Winder et al., 1974; Winder et al., 1975). Finally, the mechanisms that might support improved exercise performance following equal caloric intake (differentially distributed among macronutrients) and equal oxygen consumption rates remain to be determined. Clues may emerge from animal studies, as temporary exposure to R-3-hydroxybutyl R-βOHB in rats was associated with increased treadmill time, improved cognitive function, and an apparent energetic benefit in ex vivo perfused hearts (Murray et al., 2016).

Future perspective