Abstract

Human neurodevelopment requires the organization of neural elements into complex structural and functional networks called the connectome. Emerging data suggest that prenatal exposure to maternal stress plays a role in the wiring, or miswiring, of the developing connectome. Stress-related symptoms are common in women during pregnancy and are risk factors for neurobehavioral disorders ranging from autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and addiction, to major depression and schizophrenia. This review focuses on structural and functional connectivity imaging to assess the impact of changes in women's stress-based physiology on the dynamic development of the human connectome in the fetal brain.

Human neurodevelopment requires the organization of neural elements into complex structural and functional networks called the connectome (1,2,3). While development of the connectome is contingent on many factors, emerging data suggest that prenatal exposure to maternal stress may also play a role (4,5,6,7). Stress is a signal in response to challenging and uncontrollable adverse events and perceived threat (8,9), and exposure to early life stress is a risk factor for neurobehavioral disorders ranging from autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and addiction, to depression and schizophrenia (10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21). Both high stress and stress-related conditions, including depression and anxiety, potently stimulate biological stress pathways (7), alter synaptogenesis (22,23), and change brain development (5,24,25,26,27,28). The prenatal period is critical for brain development, and prenatal stressors exhibit long-lasting influence on adult disorders, making stressor type and timing important factors to explore (27,29,30). Fetal sex and genetic variants may also mediate stress responsiveness (6,7,31,32,33,34).

Recent reports suggest that prenatal stress exposure (PNSE) is a global public health problem (13,29,35,36). PNSE has been reported in 10–35% of children worldwide (37). Nearly 8–23% of infants in the United States, or almost 800,000 neonates/year, experience prenatal exposure to depression (38,39), and reports from developing countries support similar numbers (40,41,42). Likewise, 1 in 7 to 1 in 13 pregnant women in the United States affirm symptoms of anxiety, while 5.6–14.8% in developing countries suffer a similar diagnosis (40,41,42,43,44). Since a nationally representative study found that more than half of the pregnant women (65.9%) experiencing depression in the United States went undiagnosed (45), these data may under-represent the problem.

PNSE is believed to both activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and result in epigenetic changes in the developing brain. This review will focus on converging preclinical and clinical imaging data to assess the impact of these changes in women's stress-based physiology on the functional development of the human fetal brain. Prior to reviewing published data, we review common causes of PNSE and methods for measuring the structural and functional connectome. We also provide preliminary human data demonstrating increasing connectivity in limbic system structures across the third trimester of gestation.

Stress Models in Clinical and Translational Studies

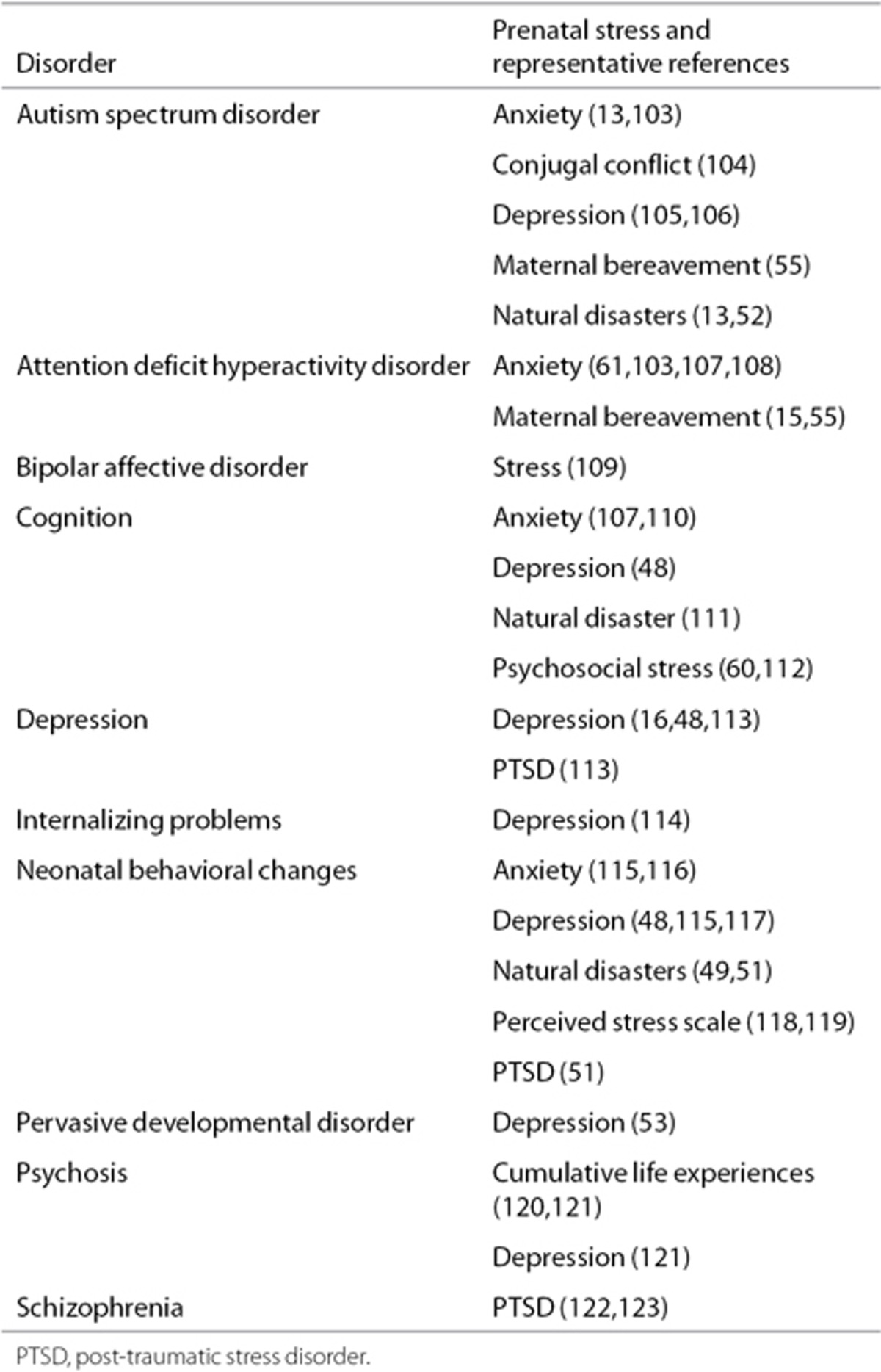

While the relationship between maternal psychosocial stress and adverse pregnancy outcomes has been shown in many studies, it is important to define the nature of the stressor and the subject population (46). Stressors range from depression and anxiety to natural disasters, bereavement and steroid administration. As stressors vary, so may the outcomes. For a listing of outcomes, putative prenatal stressors and representative publications, please see Table 1.

Table 1. Disorders and putative prenatal stressors.

Depression and Anxiety

Although some older studies relied on retrospective recall measures and few evaluated the effects of increasing duration and strength of psychosocial stressors, more recent investigations have employed depression and anxiety as markers of maternal stress. Estimates suggest that 8–23% of women have symptoms of depression during their pregnancy (47). Likewise, 7.7–14% report anxiety, and there are numerous reports of coexisting depression and anxiety in the same pregnant woman at any given time. While depression and anxiety are common proxies for stress, stress in pregnant women does not always coincide with elevated depression or anxiety scales. As such, cases of PNSE may be missed in such analysis. Finally, depression and anxiety may have independent or additive effects in regards to PNSE, making it difficult to fully disentangle these effects with this model. For a more complete review of this topic, please see Suri et al. (48).

Natural Disasters

Another approach to test the hypothesis that PNSE results in neurobehavioral disorders is the use of natural disasters as “experiments of nature.” Unlike depression and anxiety, natural disasters are independent of the subject's genetic background, personality or other confounding characteristics. Disasters strike in a random manner, similar to a randomized controlled experiment, and thus can provide data on prenatal stressors to which a given cohort of pregnant women were exposed (13). Using this strategy, the impact of disasters ranging from hurricanes to terrorist attacks on neurobehavioral outcomes of the offspring have been assessed (13,49,50,51,52).

Preconception Stress

In contrast, the influence of preconception adversity and the impact of high cumulative stress on maternal perception of prenatal stress on the developing connectome are just beginning to be explored (53,54,55). Consistent with preclinical studies showing effects of repeated stress on neural atrophy and neurobehavioral effects (56), human studies link altered structure and function of limbic, subcortical, and frontal regions to higher levels of cumulative stress (28,57,58). These data suggest that preconception adversity may shape perception and control of prenatal stress levels and should be considered in investigations of PNSE on neurobehavioral and MRI outcomes.

Prenatal Maternal Stress

PNSE has been widely associated with preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and reduced fetal head growth (50,51,59,60,61). In addition, several studies have reported that increased acute maternal stress is associated with changes in fetal heart rate, activity level, sleep patterns, and higher pulsatility indices in the middle cerebral artery (21,60). PNSE can also be directly measured using prospective data collections in samples of pregnant women with questionnaires, clinical interviews, and biological samples such as cortisol from maternal saliva, blood, or amniotic fluid.

Methods to Assess Connectivity Using MRI

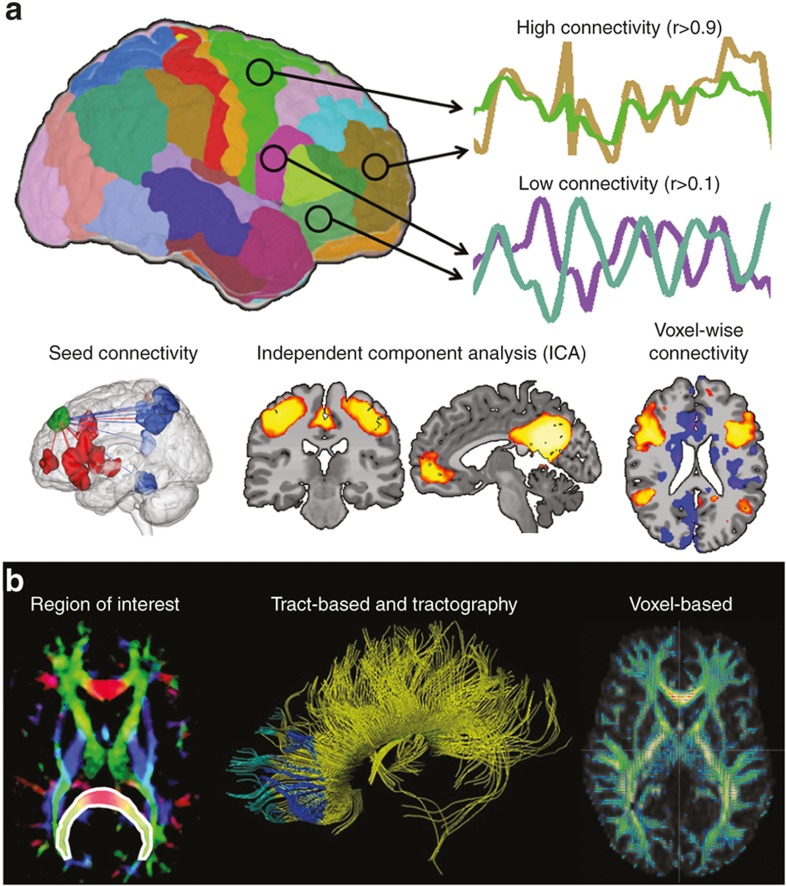

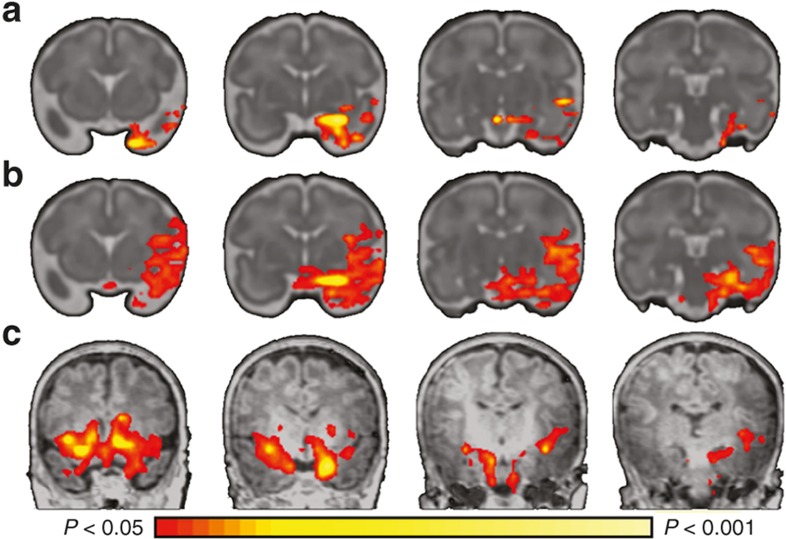

Advances in neuroimaging provide important information about microstructural and functional connectivity (62), and offer opportunities to understand the impact of PNSE on the developing connectome (1,2,3). In the following section, we define measures commonly used in connectomics with examples shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Examples of functional and structural connectivity. (a) Functional connectivity. Functional connectivity measures the synchrony or correlation of brain activity between two or more regions of the brain. Common methods include seed connectivity, independent components analysis, and voxel-wise connectivity. Seed-based connectivity measures functional connectivity from a predefined region of interest (ROI, or seed, shown in green) and the rest of the gray matter. Regions of positive or negative functional connectivity are shown as red and blue regions. Independent components analysis is mathematical modeling technique that parcellates the brain into independent spatial components or networks. Example components shown are the motor network and the defualt mode network. Voxel-wise connectivity methods involve correlating the time course of every voxel in the gray matter with the time course of every other voxel in the gray matter. Connectivity for each voxel are often summarized to a single number using network theory to highlight so-called hub regions in the brain. (b) Structural connectivity. Structural connectivity measures anatomical white matter connections linking different cortical and sub cortical regions. Common methods include ROI quantification, tract-based and tractography, and voxel-based morphometry. For ROI quantification, average FA across all voxels in a priori ROIs (shown in white outline and overlay) is compared across study groups. Tractography is modeling technique used to identifying white matter tracts used in further analyses. In VBM analysis, FA data from all subjects is transformed into a common space and comparison across each voxel of the white matter is performed. (Figure modified with permission, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ)

Functional connectivity provides information about neural regions that are physiologically functionally coupled, independent of structural connectivity (63). Based on the blood oxygen level dependent signal and derived from time series observations, it assesses “temporal correlations between spatially remote neurophysiological events.” (63) High correlation between time courses of two regions or voxels implies high functional connectivity. For the references included in this review, functional MRI (fMRI) data are largely collected in the resting state, or resting state-fMRI (rs-fMRI).

Methods to assess rs-fMRI data (64,65) include seed, independent components analysis, and voxel-wise connectivity. Seed-based connectivity is most frequently used in human studies and involves (i) selecting a predefined region of interest (ROI), (ii) extracting the average time course from this ROI, and (iii) correlating this average time course with the time courses of every other voxel in the gray matter. Independent components analysis is mathematical modeling technique that parcellates the brain into independent spatial components or networks. These networks can be compared across stubject groups or used for later analysis. Voxel-wise connectivity methods are generalizations of seed-based connectivity where many seed connectivity analyses are performed treating each voxel in the gray matter as a unique ROI. As these methods produce a large amount of data (approximately 20,000 seed-connectivity results), seed-connectivity results for each voxel are often summarized to a single number using network theory.

Anatomical connections in the developing brain represent microstructural connectivity (66). Diffusion-weighted imaging (dMRI) assesses the diffusion of water along axons and permits visualization of axonal pathways. By modeling the directional diffusion of water as an ellipsoidal shape, or “tensor”, at each voxel in the brain, dMRI permits assessment of white matter tracts. The first eigenvector, λ1, describes the direction of maximal diffusion, while the second and third define diffusivity perpendicular to this principle axis. Radial diffusivity represents the average of λ2 and λ3 and is affected by changes in axon caliber and myelination. Fractional anisotropy (FA) measures the degree to which water diffuses in one direction (along the axon) by computing the ratio of λ1 to λ2 and λ3 and is the most common measure used to assess axonal integrity. High values of FA suggest more highly organized, strongly myelinated tracts.

The three main approaches to analyzing dMRI data include region ROI quantification, tract-based analysis and tractography, and voxel-based morphometry (VBM). ROI quantification is frequently used in human studies investigating the impact of PNSE on the developing connectome. In this method, one or more ROIs are selected a priori and the average FA across all voxels in the ROI calculated. Typically, ROIs are major white matter tracts. Tractography is modeling technique used to identify these tracts. Once identified, they can be analyzed using graph theory or ROI analyses. In VBM analysis, FA data from all subjects are transformed into a common space and compared across each voxel of the white matter.

Finally, although not direct measures of the connectome, we include studies assessing brain morphometry, including cortical volumes and thickness. Morphological features of different brain regions are not independent of those of other areas, and the brain shows a high level of coordination between different structures (67). This coordination of morphological features is often referred to as anatomical covariance (67,68,69) and resembles functional and structural connectivity.

Preclinical Data Support the Impact of PNSE on Developing Connectome

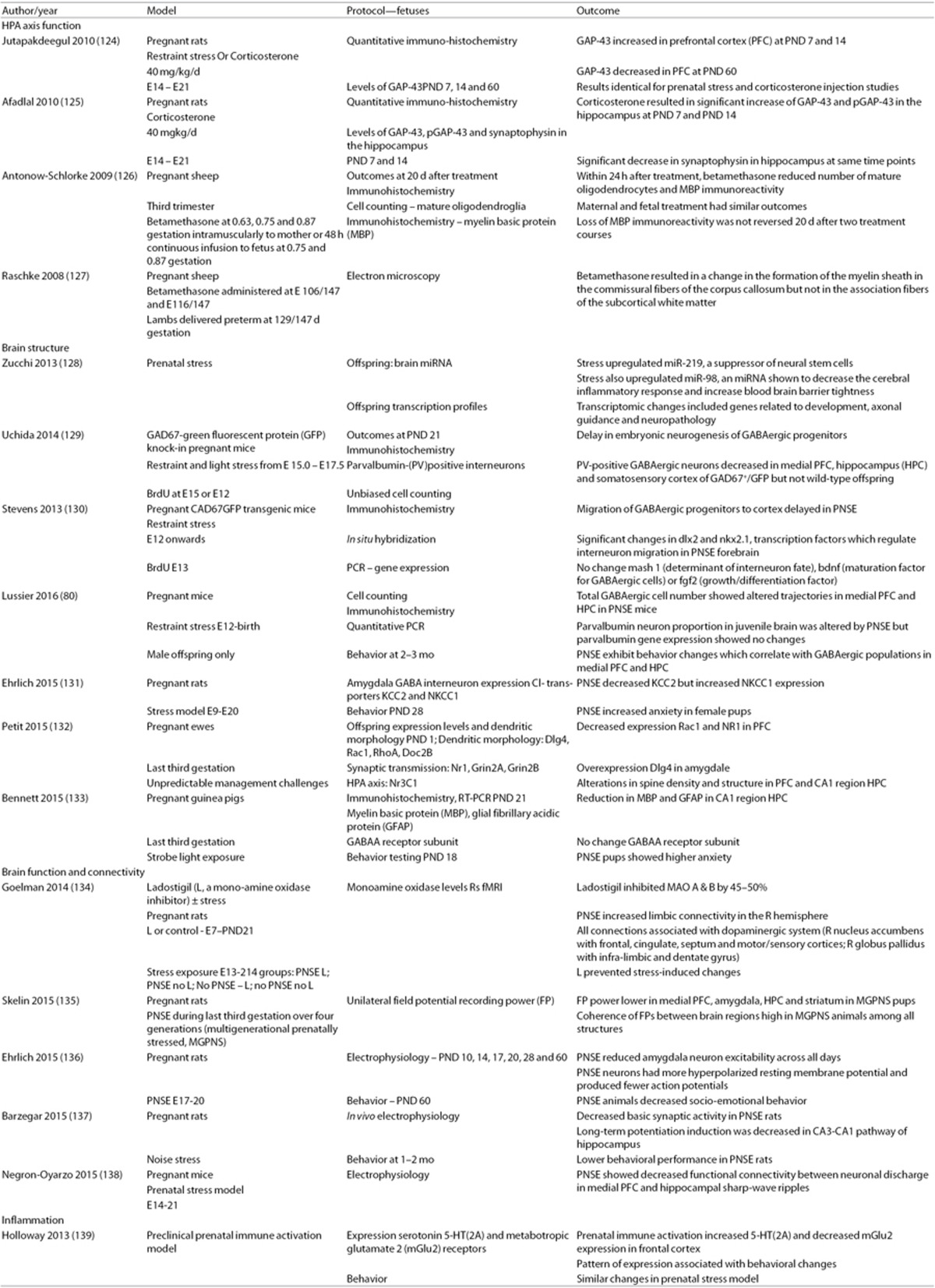

Across multiple species and numerous time points, converging data suggest that gestational stress influences brain development. Similar to the human subjects, the offspring of numerous species exposed to PNSE demonstrate increases in anxiety and depression, impaired spatial memory and alterations in cognition (70,71). Systematic experimental investigations using standardized animal models and outcome measures (6,72,73) address not only the impact of PNSE on maternal endocrine functions and the “re-programming” of the fetal HPA axis (74,75,76,77,78,79), but also suggest that changes in corticogenesis contribute to the long-lasting effects on brain and behavior (Table 2) (74,80,81).

Table 2. Prenatal stress and the connectome: preclinical data.

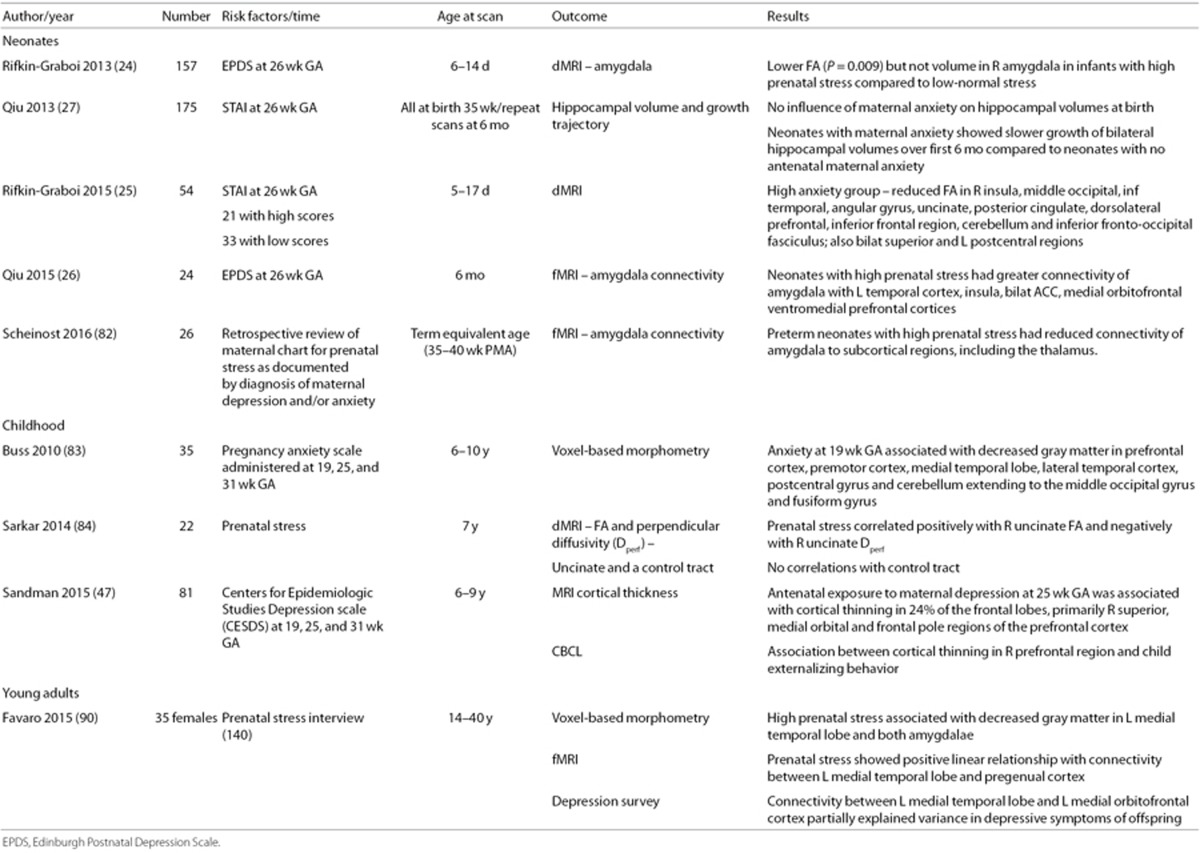

MRI Studies of PNSE and the Developing Brain

While the neural correlates of acute and cumulative postnatal stress in human subjects are active fields of study, MRI research investigating PNSE in human subjects is just starting to be explored. As described below and shown in Table 3, many investigators have interrogated the impact of PNSE on the limbic system and connected regions in the developing brain.

Table 3. Prenatal stress and the connectome: clinical data.

Studies during infancy

Recent studies suggest a significant relationship between antenatal maternal depression and/or anxiety and structure and function in the developing brain. Rifkin-Graboi performed structural MRI and dMRI on 157 nonsedated 6–14-day-old newborns whose mothers participated in the GUSTO study (Growing Up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes), a cohort of Asian women enrolled during the first trimester of pregnancy. Socioeconomic status, prenatal exposures, pregnancy measures, and birth outcomes were recorded, and imaging data were analyzed only for those infants who met the following criteria: (i) gestational age (GA) ≥37 wk, (ii) birth weight (BW) >2,500 g, and (iii) Apgar5 min > 7. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) were administered to all women at 26 wk of pregnancy. Adjusting for household income, maternal age and smoking exposure, postmenstrual age (PMA) at MRI, and BW, Rifkin-Graboi (24) found significantly lower FA but not volume in the right amygdala in infants of mothers with high EDPS scores. This suggests a significant relationship between PNSE and microstructure of the right amygdala, a region associated with stress reactivity and vulnerability for mood disorders.

Similarly, Qiu interrogated the GUSTO cohort to examine the consequences of PNSE to maternal anxiety on neonatal development of the hippocampus, a structure critical for stress regulation (27). Entry criteria for this analysis differed from those of Rifkin-Graboi's 2013 study, and included both term and late preterm infants who met the following criteria: (i) GA ≥ 35 wk; (ii) BW > 2,000 g; and (iii) Apgar5 min > 9. There were 175 GUSTO infants available for this analysis; 42 underwent repeat scans at age 6 mo, and 35 (83%) had usable data. In Qiu's analysis, antenatal maternal anxiety did not influence bilateral hippocampal volume at birth, but children of women with increased anxiety during pregnancy showed slower growth of both the left and right hippocampus between birth and age 6 mo. Subsequently, evaluating 21 GUSTO infants with high PNSE (i.e., maternal STAI > 90) and 34 with low PNSE (i.e., maternal STAI < 70), Rifkin-Graboi showed that antenatal anxiety predicted decreases in FA of regions important for cognitive-emotional responses to stress (i.e., right insula and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (PFC)), sensory processing (right middle occipital cortex), and socio-emotional function (i.e., right angular gyrus, uncinate fasciculus, posterior cingulate, and parahippocampus) at age 5–17 d (25). Of note, infants were eligible for this analysis if met the following criteria: (i) GA ≥ 36 wk; (ii) BW > 2,000 g; and (iii) Apgar5 min > 7.

Finally, Scheinost (82) and Qiu (26) investigated prenatal depression/anxiety exposure and amygdala connectivity using rs-fMRI in preterm neonates at term equivalent age and infants at age 6 mo, respectively. These data showed that, in the neonatal period, the amygdala is functionally connected to subcortical and posterior cortical regions, and, by age 6 mo, is connected to widespread networks subserving emotional regulation, memory, and social cognition. In preterm neonates, Scheinost showed that PNSE reduces amygdalar-thalamic connectivity and is additive to effects of preterm birth. Using 24 GUSTO infants, Qui showed that infants born to mothers with higher prenatal depressive symptoms had greater rs-fMRI of the amygdala with the left temporal cortex, insula, anterior cingulate (ACC), medial orbitofrontal, and ventromedial PFC. These networks are reported in children and adults with depression, suggesting that rs-fMRI data may foreshadow future neuropsychiatric disease.

Studies during childhood

Studies of older children also suggest that maternal anxiety is associated with specific changes in brain morphology. Buss evaluated children ages 6–10 y whose mothers had been enrolled in a prospective study of pregnancy at the University of California, Irvine or Cedars Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, CA, between 1998 and 2002 (83). Families were contacted again in 2007 and invited to participate in a follow-up study of their children to assess the influence of PNSE on brain development. At the time of this report, 35 mother–child dyads had both usable MRI data and complete maternal data. VBM on these children demonstrated that exposure to high maternal stress at 19 wk of gestation correlated with gray matter reductions in the PFC, premotor cortex, medial temporal lobe, lateral temporal cortex, post-central gyrus, and cerebellum extending to the middle occipital and fusiform gyri. Although the numbers are small and assessments of postnatal stress exposure were not included in the authors' analyses, high pregnancy stress at 25 and 31 wk of gestation was not associated with local reductions in gray matter volume, suggesting the importance of earlier exposure to gestational psychological stress. Similarly, Sarkar performed dMRI studies to assess both FA and perpendicular diffusivity (Dperp) on 22 children ages 6–9 y whose mothers were retrospectively assessed for PNSE when the children were age 17 mo (84). For these children, PNSE was positively correlated with right uncinate FA and negatively with right uncinate Dperp, while PNSE was not associated with control tract properties.

In addition, since reduced cortical volume and thickness have both been associated with a history of depression in adult populations (85,86), Sandman measured cortical thickness in 81 school aged children whose mothers had participated in the longitudinal study described above; (83) all were prospectively evaluated for depression at 19, 25, and 31 wk of gestation (47). Prenatal maternal depression exposure was associated with thinning in the right frontal lobe, and the strongest association was with exposure at 25 wk gestation. Morphological changes were primarily found in the superior, medial orbital, and frontal pole regions of the right PFC, consistent with data in adults with depressive symptomatology (85,86). Further, the significant association between prenatal depression exposure and child externalizing behavior in this cohort of children was mediated by these changes.

Studies during adulthood

Finally, although MR studies of young adults with early life stress exposures are just beginning to emerge (87,88,89), Favaro explored the relationship between PNSE, cortical volumes and rs-fMRI in a sample of 35 healthy women aged 14–40 y (90). The sample was composed of volunteers to whose mothers a semi-structured interview assessing stress related events during pregnancy was administered. Subject scores were assigned based on interview data and used for MRI analyses. For these women, greater PNSE was associated with decreased gray matter volume in the left medial temporal lobe and both amygdalae. Strength of PNSE was positively correlated with rs-fMRI between the left medial temporal lobe and pre-genual cortex, and connectivity between the left medial temporal lobe and left medial-orbitofrontal cortex partially explained variance in depressive symptoms in this cohort.

Emerging Factors

As studies begin to investigate the impact of PNSE on the connectome, several factors from both preclinical and clinical data have emerged as key considerations for future studies. These factors include defining the normal developmental trajectories of the fetal connectome, the type, timing and duration of PNSE, and the fetal sex. Other factors not addressed within this review include assessing the role of paternal preconception stress and identifying the molecular signatures of PNSE.

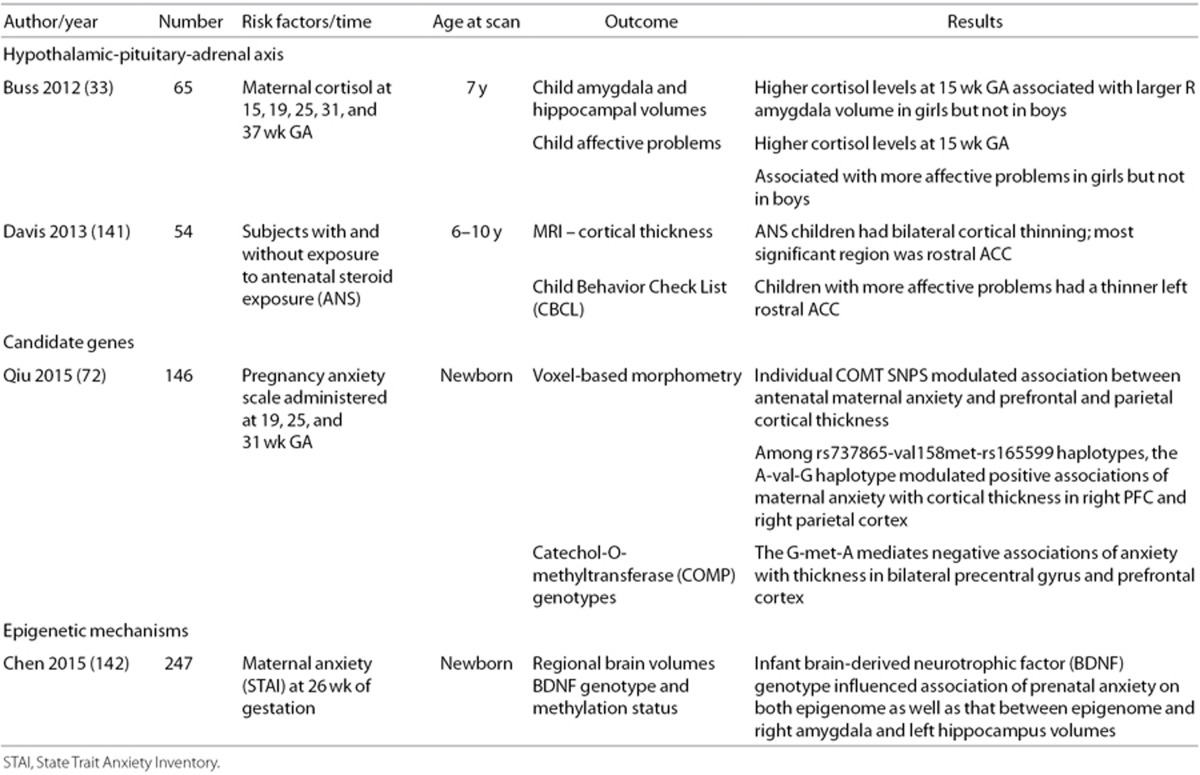

Fetal networks

“Trajectory analysis is central to the assessment of the impact of PNSE on the developing brain.” (2) Fetal rs-fMRI is an emerging technology obtaining information about neural network development in utero by directly measuring the fetal brain (91). These methods are needed to investigate the prenatal connectome as it develops and pinpoint how and when PNSE alters its development. Using cross-sectional functional connectivity data between 21–38 wk of gestation, fetuses show evidence of both long-range functional connectivity and the emergence of neural networks across the third trimester, mimicking those in older children and adults (92,93). However, both longitudinal and cross-sectional data are needed to more fully characterize the developmental trajectories of PNSE. To begin to address this problem, we performed longitudinal rs-fMRI on 10 typically developing fetuses at 30–32, 34–36 wk PMA and following term delivery. This study was approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee, and pregnant women signed consent for the protocol. Because of its documented role in neurobehavioral disorders and alterations in studies of PNSE described above, we interrogated the emergence of amygdala networks during the prenatal period. During the 3rd trimester, left amygdala connectivity is first characterized by local circuitry, then begins to connect to ipsilateral regions in the frontal and temporal lobes, and finally develops connections to the contralateral amygdala (Figure 2). The development of these important cross-hemispheric connections between the right and left amygdala develop during the end of the third trimester and likely increases the vulnerability of this circuitry to PNSE (55).

Figure 2.

Development of left amygdala functional connectivity during the perinatal period. During the perinatal period, (a) left amygdala connectivity is first characterized by a largely local circuitry, (b) then begins to connect to ipsilateral regions in the frontal and temporal lobes, and (c) finally develops connections to the contralateral amygdala.

Timing of stress exposure

There is increasing recognition that fetal stress exposure has a particularly pronounced impact during early periods of corticogenesis, commonly known as critical periods in the developing brain. Critical periods refer to epochs characterized by both increasing plasticity and greater vulnerability; thus, these are times when the developing brain may be most easily modified in either favorable or unfavorable directions. Critical periods are thought to be environmentally sensitive, and many authors believe they underlie the developmental origins of neurobehavioral disorders such as ASD.

Typically developing fetuses with PNSE during the middle second and third trimesters of gestation are reported to be at the greatest risk for neurobehavioral disorders (13,52). Reviewing Swedish birth registries, Class examined associations between PNSE in 738,144 offspring born in 1992–2000 for childhood outcomes and 2,155,221 offspring born in 1973–1997 for adult outcomes. Although data for GA are not available, third trimester bereavement stress significantly increased risk of both ASD and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (55). Similarly, children who had been exposed to tropical storms during gestation months 5–6 or 9–10 had 3.8 times greater risk of developing ASD than children who had been exposed to the same storms, in the same place, but during other months of gestation (52). Duration of maternal stress may also play a role. Analyzing data from 4,682 live births, Latendresse reported that children of mothers with the longest periods of prenatal depression exposure experienced more than seven times increased risk for pervasive developmental disorder when compared to children with no PNSE (53).

In contrast, in the GUSTO study, mothers were assessed for gestational depression and/or anxiety at 26 wk, and MRI measures were correlated with these data (24,25,26,27). In addition, Sandman performed depression screening on 82 pregnant mothers at 19, 25, and 31 wk gestation and found that antenatal exposure to maternal depression at 25 wk gestation was significantly correlated with cortical thinning in 24% of the frontal lobes in the offspring (47). Finally, although cortisol levels are not available for subjects in the prior MRI studies, high levels of maternal cortisol at 15 wk (but not 19, 25, 31, or 37 wk) of gestation were associated with amygdala volumetric changes in girls but not in boys (33). Since high levels of cortisol are believed to reprogram the fetal HPA axis and maternal stress has been reported to downregulate 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (75), the placental enzyme which metabolizes cortisol (75), future studies of maternal psychological stress during gestation should consider longitudinal assessments of maternal cortisol in tandem with fetal neuroimaging.

Sex differences in prenatal stress outcomes

The link between PNSE and outcomes may be moderated by fetal sex. The source of sex differences upon early development is unclear but may include placental functioning, exposure to adrenal hormones and testosterone and an assortment of epigenetic mechanisms (94,95,96,97). Recent fetal pathways also proposed include sex-dependent responses of the transcriptome (6,98,99,100), naturally occurring sexually-dimorphic processes mediating neuron-glial interactions (101), and differential responses of target regions in the developing brain (102). Thus, while PNSE may have consequences for both males and females, the specificity of effects may differ. To the best of our knowledge, however, only a single study has reported sex differences in MRI outcome measures. These data suggest that higher cortisol levels at 15 wk of gestation were associated with larger right amygdala volumes and more affective problems in female but not male offspring (33).

Mechanisms of Prenatal Stress and the Connectome

Taken together, published studies of PNSE suggest both proximate and long-lasting influence on the connectome. However, mechanisms of how PNSE alters the developing connectome must be explored. Mechanistic studies have focused on the HPA axis, candidate genes, and epigenetic pathways (see Table 4).

Table 4. Prenatal stress and the connectome: Endocrine and genetic mechanisms.

Moving Forward: Investigation of the Clinical Problem, Changes in Care

Converging data suggest that PNSE alters the developing connectome. As noted by Sporns, “The placement of brain connectivity as an intermediate phenotype between environmental exposures and behavior makes it an important target for studies that link networks across levels from behavior to molecules, neurons and emerging networks in the developing brain” (62). To better address the impact of PNSE on the connectome, longitudinal studies of maternal/fetal dyads with and without stress exposure are needed. Such investigations would benefit from repeated assessments of maternal stress in order to identify type, time of onset, and duration of PNSE and correlate these data with sequential imaging. In addition, preconceptional stress may influence offspring outcome, and pregnant women should be surveyed for cumulative stress at the time of study enrollment. Likewise, both genetic variants and epigenetic changes may contribute to outcome in the offspring, and consideration should be made to include these data in PNSE-offspring outcome analyses. Finally, longitudinal fetal imaging will provide important information about target regions, and developmental trajectory analyses are well suited for interrogation of the developing connectome.

These strategies can be used to detect developmental disturbances of the connectome that may underlie the development of neurobehavioral disorders.

Statement of Financial Support

This work was supported by Gates Foundation OPP1119263, Seattle, WA, and National Institutes of Health T32 HD07094, Bethesda, MD.

Disclosure

None of the authors have disclosures.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our medical, nursing and research colleagues and the infants and their mothers who agreed to take part in this study. We are also grateful to Michael Labrec, R.T.R., for technical expertise.

References

- Dennis EL, Thompson PM. Typical and atypical brain development: a review of neuroimaging studies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2013;15:359–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino A, Fair DA, Kelly C, et al. Unraveling the miswired connectome: a developmental perspective. Neuron 2014;83:1335–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham AM, Pfeifer JH, Fisher PA, Lin W, Gao W, Fair DA. The potential of infant fMRI research and the study of early life stress as a promising exemplar. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2015;12:12–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provençal N, Binder EB. The effects of early life stress on the epigenome: From the womb to adulthood and even before. Exp Neurol 2015;268:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Baram TZ. Toward understanding how early-life stress reprograms cognitive and emotional brain networks. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016;41:197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson SL, Bale TL. Prenatal stress-induced increases in placental inflammation and offspring hyperactivity are male-specific and ameliorated by maternal antiinflammatory treatment. Endocrinology 2014;155:2635–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinof A, Moisiadis VG, Matthews SG. Programming of stress pathways: A transgenerational perspective. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2016;160:175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1141:105–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. The neurobiology and neuroendocrinology of stress. Implications for post-traumatic stress disorder from a basic science perspective. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002;25:469–94, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS. Epidemiologic studies of exposure to prenatal infection and risk of schizophrenia and autism. Dev Neurobiol 2012;72:1272–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howerton CL, Bale TL. Prenatal programing: at the intersection of maternal stress and immune activation. Horm Behav 2012;62:237–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khashan AS, Abel KM, McNamee R, et al. Higher risk of offspring schizophrenia following antenatal maternal exposure to severe adverse life events. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney DK, Munir KM, Crowley DJ, Miller AM. Prenatal stress and risk for autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2008;32:1519–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JI, Kirkpatrick B, Lee P. Glucocorticoid hormones and early brain development in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002;27:309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Olsen J, Vestergaard M, Obel C. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the offspring following prenatal maternal bereavement: a nationwide follow-up study in Denmark. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;19:747–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RM, Evans J, Kounali D, et al. Maternal depression during pregnancy and the postnatal period: risks and possible mechanisms for offspring depression at age 18 years. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:1312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talge NM, Neal C, Glover V; Early Stress, Translational Research and Prevention Science Network: Fetal and Neonatal Experience on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007;48:245–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Buss C, Wadhwa PD. Prenatal stress, development, health and disease risk: a psychobiological perspective-2015 Curt Richter Award Paper. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;62:366–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagna A, Nosarti C. Socio-emotional development following very preterm birth: pathways to psychopathology. Front Psychol 2016;7:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani PG, Richter LM, Norris SA, Stein A. Maternal prenatal stress and later child behavioral problems in an urban South African setting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:239–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella MT, Monk C. Impact of maternal stress, depression and anxiety on fetal neurobehavioral development. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2009;52:425–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL, Baram TZ, Brown AS, et al. Early life programming and neurodevelopmental disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2010;68:314–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Taylor A, Korosi A, Molet J, Gunn BG, Baram TZ. Synaptic rewiring of stress-sensitive neurons by early-life experience: a mechanism for resilience? Neurobiol Stress 2015;1:109–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin-Graboi A, Bai J, Chen H, et al. Prenatal maternal depression associates with microstructure of right amygdala in neonates at birth. Biol Psychiatry 2013;74:837–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin-Graboi A, Meaney MJ, Chen H, et al. Antenatal maternal anxiety predicts variations in neural structures implicated in anxiety disorders in newborns. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54:313–21.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu A, Anh TT, Li Y, et al. Prenatal maternal depression alters amygdala functional connectivity in 6-month-old infants. Transl Psychiatry 2015;5:e508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu A, Rifkin-Graboi A, Chen H, et al. Maternal anxiety and infants' hippocampal development: timing matters. Transl Psychiatry 2013;3:e306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam NT, Rando K, Potenza MN, Tuit K, Sinha R. Childhood maltreatment, altered limbic neurobiology, and substance use relapse severity via trauma-specific reductions in limbic gray matter volume. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:917–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LP. Maternal and pediatric health and disease: integrating biopsychosocial models and epigenetics. Pediatr Res 2016;79:127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Barouki R, Bellinger DC, et al. Life-long implications of developmental exposure to environmental stressors: new perspectives. Endocrinology 2015;156:3408–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock J, Wainstock T, Braun K, Segal M. Stress in utero: prenatal programming of brain plasticity and cognition. Biol Psychiatry 2015;78:315–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howerton CL, Morgan CP, Fischer DB, Bale TL. O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) as a placental biomarker of maternal stress and reprogramming of CNS gene transcription in development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:5169–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Davis EP, Shahbaba B, Pruessner JC, Head K, Sandman CA. Maternal cortisol over the course of pregnancy and subsequent child amygdala and hippocampus volumes and affective problems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:E1312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Entringer S, Davis EP, et al. Impaired executive function mediates the association between maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and child ADHD symptoms. PLoS One 2012;7:e37758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertes DA, Kamin HS, Hughes DA, Rodney NC, Bhatt S, Mulligan CJ. Prenatal maternal stress predicts methylation of genes regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system in mothers and newborns in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Child Dev 2016;87:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen AB, Kertes DA, McNamara GI, et al. A role for the placenta in programming maternal mood and childhood behavioural disorders. J Neuroendocrinol 2016;28:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Sikander S, Bhalotra S, et al. Effect of an early perinatal depression intervention on long-term child development outcomes: follow-up of the Thinking Healthy Programme randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2:609–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:403–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Perinatal Depression Toolkit. 2016. http://mail.ny.acog.org/website/DepressionToolkit.pdf.

- Mapayi B, Makanjuola RO, Mosaku SK, et al. Impact of intimate partner violence on anxiety and depression amongst women in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Arch Womens Ment Health 2013;16:11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:139G–49G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2010;123:17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel D, Kriston L, Barkmann C, et al.; International CDS Study Group. Longitudinal course of ante- and postpartum generalized anxiety symptoms and associated factors in West-African women from Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire. J Affect Disord 2016;197:125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin: Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists number 92, April 2008 (replaces practice bulletin number 87, November 2007). Use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol 2008. 111:1001–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JY, Farr SL, Dietz PM, Robbins CL. Depression and treatment among U.S. pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005-2009. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:830–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, Lam SK, Sze Mun Lau SM, Chong CS, Chui HW, Fong DY. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1102–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandman CA, Buss C, Head K, Davis EP. Fetal exposure to maternal depressive symptoms is associated with cortical thickness in late childhood. Biol Psychiatry 2015;77:324–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suri R, Lin AS, Cohen LS, Altshuler LL. Acute and long-term behavioral outcome of infants and children exposed in utero to either maternal depression or antidepressants: a review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:e1142–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville E, Xiong X, Buekens P. Disasters and perinatal health:a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2010;65:713–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SM, Berkowitz GS, Wolff MS, Yehuda R. Psychological trauma associated with the World Trade Center attacks and its effect on pregnancy outcome. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2005;19:334–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand SR, Engel SM, Canfield RL, Yehuda R. The effect of maternal PTSD following in utero trauma exposure on behavior and temperament in the 9-month-old infant. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1071:454–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney DK, Miller AM, Crowley DJ, Huang E, Gerber E. Autism prevalence following prenatal exposure to hurricanes and tropical storms in Louisiana. J Autism Dev Disord 2008;38:481–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse G, Wong B, Dyer J, Wilson B, Baksh L, Hogue C. Duration of Maternal Stress and Depression: Predictors of Newborn Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Postpartum Depression. Nurs Res 2015;64:331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock J, Poeschel J, Schindler J, et al. Transgenerational sex-specific impact of preconception stress on the development of dendritic spines and dendritic length in the medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Struct Funct 2016;221:855–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Class QA, Abel KM, Khashan AS, et al. Offspring psychopathology following preconception, prenatal and postnatal maternal bereavement stress. Psychol Med 2014;44:71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Waters EM, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Estrogen Effects on Cognitive and Synaptic Health Over the Lifecourse. Physiol Rev 2015;95:785–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell EB, Rando K, Tuit K, Guarnaccia J, Sinha R. Cumulative adversity and smaller gray matter volume in medial prefrontal, anterior cingulate, and insula regions. Biol Psychiatry 2012;72:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Tsou KA, Ansell EB, Potenza MN, Sinha R. Cumulative adversity sensitizes neural response to acute stress: association with health symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014;39:670–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AJ, Austin E, Galbally M Prenatal maternal mental health and fetal growth restriction: a systematic review. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2016;7:416–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandman CA, Davis EP, Buss C, Glynn LM. Exposure to prenatal psychobiological stress exerts programming influences on the mother and her fetus. Neuroendocrinology 2012;95:7–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice F, Harold GT, Boivin J, van den Bree M, Hay DF, Thapar A. The links between prenatal stress and offspring development and psychopathology: disentangling environmental and inherited influences. Psychol Med 2010;40:335–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporns O. Structure and function of complex brain networks. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2013;15:247–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ. Functional and effective connectivity: a review. Brain Connect 2011;1:13–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007;8:700–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinost D, Finn ES, Tokoglu F, et al. Sex differences in normal age trajectories of functional brain networks. Hum Brain Mapp 2015;36:1524–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Zhang J. Principles of diffusion tensor imaging and its applications to basic neuroscience research. Neuron 2006;51:527–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechelli A, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS, Price CJ. Structural covariance in the human cortex. J Neurosci 2005;25:8303–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AC. Networks of anatomical covariance. Neuroimage 2013;80:489–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinost D, Kwon SH, Lacadie C, Vohr BR, Schneider KC, Papademetris X, Constable RT, Ment LR Alterations in anatomical covariance in the prematurely born. Cereb Cortex 2016. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhv248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kolb B, Mychasiuk R, Muhammad A, Li Y, Frost DO, Gibb R. Experience and the developing prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109 Suppl 2:17186–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniam J, Antoniadis C, Morris MJ. Early-life stress, HPA axis adaptation, and mechanisms contributing to later health outcomes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu A, Tuan TA, Ong ML, et al. COMT haplotypes modulate associations of antenatal maternal anxiety and neonatal cortical morphology. Am J Psychiatry 2015;172:163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsotsi S, Abdulla N, Li C, et al. Fetal DNA methylation of cortisol-related genes and infant neurobehavior at 6 months: The role of antenatal maternal anxiety. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;61:35. [Google Scholar]

- Bock J, Rether K, Gröger N, Xie L, Braun K. Perinatal programming of emotional brain circuits: an integrative view from systems to molecules. Front Neurosci 2014;8:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell KJ, Bugge Jensen A, Freeman L, Khalife N, O'Connor TG, Glover V. Maternal prenatal anxiety and downregulation of placental 11β-HSD2. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012;37:818–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mairesse J, Lesage J, Breton C, et al. Maternal stress alters endocrine function of the feto-placental unit in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007;292:E1526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen Peña C, Monk C, Champagne FA. Epigenetic effects of prenatal stress on 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-2 in the placenta and fetal brain. PLoS One 2012;7:e39791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Padbury JF. Third pathophysiology of prenatal cocaine exposure. Dev Neurosci 2009;31:23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gonzalez P, Zhang L. Fetal stress and programming of hypoxic/ischemic-sensitive phenotype in the neonatal brain: mechanisms and possible interventions. Prog Neurobiol 2012;98:145–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier SJ, Stevens HE. Delays in GABAergic interneuron development and behavioral inhibition after prenatal stress. Dev Neurobiol 2016;76:1078–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer FE, Leech R, Expert P, Lord LD, Vernon AC. The brain's code and its canonical computational motifs. From sensory cortex to the default mode network: A multi-scale model of brain function in health and disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;55:211–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinost D, Kwon SH, Lacadie C, et al. Prenatal stress alters amygdala functional connectivity in preterm neonates. Neuroimage Clin 2016;12:381–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Davis EP, Muftuler LT, Head K, Sandman CA. High pregnancy anxiety during mid-gestation is associated with decreased gray matter density in 6-9-year-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010;35:141–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Craig MC, Dell'Acqua F, et al. Prenatal stress and limbic-prefrontal white matter microstructure in children aged 6-9 years: a preliminary diffusion tensor imaging study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2014;15:346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Warner V, Bansal R, et al. Cortical thinning in persons at increased familial risk for major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:6273–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Weissman MM. A brain-based endophenotype for major depressive disorder. Annu Rev Med 2011;62:461–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MM, Wood K, Sreenivasan K, et al. Influence of early life stress on intra- and extra-amygdaloid causal connectivity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40:1782–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz NE, Boecker R, Hohm E, et al. The long-term impact of early life poverty on orbitofrontal cortex volume in adulthood: results from a prospective study over 25 years. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40:996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonzo GA, Ramsawh HJ, Flagan TM, et al. Early life stress and the anxious brain: evidence for a neural mechanism linking childhood emotional maltreatment to anxiety in adulthood. Psychol Med 2016;46:1037–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro A, Tenconi E, Degortes D, Manara R, Santonastaso P. Neural correlates of prenatal stress in young women. Psychol Med 2015;45:2533–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöpf V, Kasprian G, Brugger PC, Prayer D. Watching the fetal brain at ‘rest'. Int J Dev Neurosci 2012;30:11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Thomason ME. Functional plasticity before the cradle: a review of neural functional imaging in the human fetus. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013;37(9 Pt B):2220–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason ME, Grove LE, Lozon TA Jr, et al. Age-related increases in long-range connectivity in fetal functional neural connectivity networks in utero. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2015;11:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock M. Sex-dependent changes induced by prenatal stress in cortical and hippocampal morphology and behaviour in rats: an update. Stress 2011;14:604–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma SM, Pfaff DW. Etiologies underlying sex differences in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front Neuroendocrinol 2014;35:255–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Auyeung B, Chakrabarti B, Baron-Cohen S. Sex/gender differences and autism: setting the scene for future research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54:11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano E, Cosentino L, Laviola G, De Filippis B. Genes and sex hormones interaction in neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;67:9–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundwald NJ, Benitez DP, Brunton PJ. Sex-dependent effects of prenatal stress on social memory in rats: a role for differential expression of central vasopressin-1a receptors. J Neuroendocrinol 2015;28 doi:10.1111/jne.12343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundwald NJ, Brunton PJ. Prenatal stress programs neuroendocrine stress responses and affective behaviors in second generation rats in a sex-dependent manner. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;62:204–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mychasiuk R, Gibb R, Kolb B. Prenatal stress produces sexually dimorphic and regionally specific changes in gene expression in hippocampus and frontal cortex of developing rat offspring. Dev Neurosci 2011;33:531–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werling DM, Parikshak NN, Geschwind DH. Gene expression in human brain implicates sexually dimorphic pathways in autism spectrum disorders. Nat Commun 2016;7:10717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frahm KA, Peffer ME, Zhang JY, et al. Research resource: the dexamethasone transcriptome in hypothalamic embryonic neural stem cells. Mol Endocrinol 2016;30:144–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, Pennell CE, Whitehouse AJ. Prenatal maternal stress associated with ADHD and autistic traits in early childhood. Front Psychol 2010;1:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi E, Veggo F, Narzisi A, Compare A, Muratori F. Pregnancy risk factors in autism: a pilot study with artificial neural networks. Pediatr Res 2016;79:339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Xi QQ, Wu J, et al. Association between prenatal environmental factors and child autism: a case control study in Tianjin, China. Biomed Environ Sci 2015;28:642–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser JC, Rommelse N, Vink L, et al. Narrowly versus broadly defined autism spectrum disorders: differences in pre- and perinatal risk factors. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43:1505–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh BR, Mennes M, Oosterlaan J, et al. High antenatal maternal anxiety is related to impulsivity during performance on cognitive tasks in 14- and 15-year-olds. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005;29:259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bergh BR, Mennes M, Stevens V, et al. ADHD deficit as measured in adolescent boys with a continuous performance task is related to antenatal maternal anxiety. Pediatr Res 2006;59:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JA, Koenig JI. Prenatal stress: role in psychotic and depressive diseases. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:89–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Davis EP, Hobel CJ, Sandman CA. Maternal pregnancy-specific anxiety is associated with child executive function at 6-9 years age. Stress 2011;14:665–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante DP, Brunet A, Schmitz N, Ciampi A, King S. Project Ice Storm: prenatal maternal stress affects cognitive and linguistic functioning in 5 ½-year-old children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008;47:1063–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Sandman CA. The timing of prenatal exposure to maternal cortisol and psychosocial stress is associated with human infant cognitive development. Child Dev 2010;81:131–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Bell A, Bierer LM, Schmeidler J. Maternal, not paternal, PTSD is related to increased risk for PTSD in offspring of Holocaust survivors. J Psychiatr Res 2008;42:1104–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts KS, Williams GM, Najman JM, Alati R. Maternal depressive, anxious, and stress symptoms during pregnancy predict internalizing problems in adolescence. Depress Anxiety 2014;31:9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MP, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Leader L, Saint K, Parker G. Maternal trait anxiety, depression and life event stress in pregnancy: relationships with infant temperament. Early Hum Dev 2005;81:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair MM, Glynn LM, Sandman CA, Davis EP. Prenatal maternal anxiety and early childhood temperament. Stress 2011;14:644–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury AL, O'Grady KE, Battle CL, et al. The roles of maternal depression, serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment, and concomitant benzodiazepine use on infant neurobehavioral functioning over the first postnatal month. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:147–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Feng T, Lee S, Krupska I, Champagne FA, Tycko B. Distress during pregnancy: epigenetic regulation of placenta glucocorticoid-related genes and fetal neurobehavior. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:705–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Glynn LM, Waffarn F, Sandman CA. Prenatal maternal stress programs infant stress regulation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2011;52:119–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrington S, Zammit S, Asher L, Evans J, Heron J, Lewis G. Perinatal maternal life events and psychotic experiences in children at twelve years in a birth cohort study. Schizophr Res 2014;152:158–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts KS, Williams GM, Najman JM, Alati R. The relationship between maternal depressive, anxious, and stress symptoms during pregnancy and adult offspring behavioral and emotional problems. Depress Anxiety 2015;32:82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaspina D, Corcoran C, Kleinhaus KR, et al. Acute maternal stress in pregnancy and schizophrenia in offspring: a cohort prospective study. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran C, Perrin M, Harlap S, et al. Incidence of schizophrenia among second-generation immigrants in the jerusalem perinatal cohort. Schizophr Bull 2009;35:596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutapakdeegul N, Afadlal S, Polaboon N, Phansuwan-Pujito P, Govitrapong P. Repeated restraint stress and corticosterone injections during late pregnancy alter GAP-43 expression in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of rat pups. Int J Dev Neurosci 2010;28:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afadlal S, Polaboon N, Surakul P, Govitrapong P, Jutapakdeegul N. Prenatal stress alters presynaptic marker proteins in the hippocampus of rat pups. Neurosci Lett 2010;470:24–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonow-Schlorke I, Helgert A, Gey C, et al. Adverse effects of antenatal glucocorticoids on cerebral myelination in sheep. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:142–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschke C, Schmidt S, Schwab M, Jirikowski G. Effects of betamethasone treatment on central myelination in fetal sheep: an electron microscopical study. Anat Histol Embryol 2008;37:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchi FC, Yao Y, Ward ID, et al. Maternal stress induces epigenetic signatures of psychiatric and neurological diseases in the offspring. PLoS One 2013;8:e56967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T, Furukawa T, Iwata S, Yanagawa Y, Fukuda A. Selective loss of parvalbumin-positive GABAergic interneurons in the cerebral cortex of maternally stressed Gad1-heterozygous mouse offspring. Transl Psychiatry 2014;4:e371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens HE, Su T, Yanagawa Y, Vaccarino FM. Prenatal stress delays inhibitory neuron progenitor migration in the developing neocortex. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013;38:509–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich DE, Neigh GN, Bourke CH, et al. Prenatal stress, regardless of concurrent escitalopram treatment, alters behavior and amygdala gene expression of adolescent female rats. Neuropharmacology 2015;97:251–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit B, Boissy A, Zanella A, et al. Stress during pregnancy alters dendritic spine density and gene expression in the brain of new-born lambs. Behav Brain Res 2015;291:155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GA, Palliser HK, Shaw JC, Walker D, Hirst JJ. Prenatal stress alters hippocampal neuroglia and increases anxiety in childhood. Dev Neurosci 2015;37:533–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goelman G, Ilinca R, Zohar I, Weinstock M. Functional connectivity in prenatally stressed rats with and without maternal treatment with ladostigil, a brain-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Eur J Neurosci 2014;40:2734–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelin I, Needham MA, Molina LM, Metz GA, Gruber AJ. Multigenerational prenatal stress increases the coherence of brain signaling among cortico-striatal-limbic circuits in adult rats. Neuroscience 2015;289:270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich DE, Rainnie DG. Prenatal stress alters the development of socioemotional behavior and amygdala neuron excitability in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40:2135–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzegar M, Sajjadi FS, Talaei SA, Hamidi G, Salami M. Prenatal exposure to noise stress: anxiety, impaired spatial memory, and deteriorated hippocampal plasticity in postnatal life. Hippocampus 2015;25:187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrón-Oyarzo I, Neira D, Espinosa N, Fuentealba P, Aboitiz F. Prenatal stress produces persistence of remote memory and disrupts functional connectivity in the hippocampal-prefrontal cortex axis. Cereb Cortex 2015;25:3132–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway T, Moreno JL, Umali A, et al. Prenatal stress induces schizophrenia-like alterations of serotonin 2A and metabotropic glutamate 2 receptors in the adult offspring: role of maternal immune system. J Neurosci 2013;33:1088–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychol 1999;18:333–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Sandman CA, Buss C, Wing DA, Head K. Fetal glucocorticoid exposure is associated with preadolescent brain development. Biol Psychiatry 2013;74:647–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Pan H, Tuan TA, et al.; Gusto Study Group. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism influences the association of the methylome with maternal anxiety and neonatal brain volumes. Dev Psychopathol 2015;27:137–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]