Abstract

YKL-40 is a mammalian glycoprotein associated with progression, severity, and prognosis of chronic inflammatory diseases and a multitude of cancers. Despite this well documented association, identification of the lectin′s physiological ligand and, accordingly, biological function has proven experimentally difficult. YKL-40 has been shown to bind chito-oligosaccharides; however, the production of chitin by the human body has not yet been documented. Possible alternative ligands include proteoglycans, polysaccharides, and fibers like collagen, all of which makeup the extracellular matrix. It is likely that YKL-40 is interacting with these alternative polysaccharides or proteins within the body, extending its function to cell biological roles such as mediating cellular receptors and cell adhesion and migration. Here, we consider the feasibility of polysaccharides, including cello-oligosaccharides, hyaluronan, heparan sulfate, heparin, and chondroitin sulfate, and collagen-like peptides as physiological ligands for YKL-40. We use molecular dynamics simulations to resolve the molecular level recognition mechanisms and calculate the free energy of binding the hypothesized ligands to YKL-40, addressing thermodynamic preference relative to chito-oligosaccharides. Our results suggest that chitohexaose and hyaluronan preferentially bind to YKL-40 over collagen, and hyaluronan is likely the preferred physiological ligand, because the negatively charged hyaluronan shows enhanced affinity for YKL-40 over neutral chitohexaose. Collagen binds in two locations at the YKL-40 surface, potentially related to a role in fibrillar formation. Finally, heparin non-specifically binds at the YKL-40 surface, as predicted from structural studies. Overall, YKL-40 likely binds many natural ligands in vivo, but its concurrence with physical maladies may be related to associated increases in hyaluronan.

Keywords: chitinase, glycosaminoglycan, glycoside hydrolase, lectin, molecular modeling, thermodynamics

Introduction

YKL-40, also known as chitinase 3-like 1, is a mammalian glycoprotein implicated as a biomarker associated with progression, severity, and prognosis of chronic inflammatory diseases and a multitude of cancers (1–4). Many different types of cells including synovial, endothelial, epithelial, smooth muscle, and tumor cells produce YKL-40 in vivo, likely in response to environmental cues (5–8). Speculation as to biological function of YKL-40 varies from both inhibiting and antagonizing collagen fibril formation as a result of injury or disease (9), as well as conferring drug resistance and increasing cell migration leading to progression of cancer (3), and protection from chitin-containing pathogens (10). Although the association of YKL-40 with physical maladies is well documented, identification of the physiological ligand of this lectin, and thus biological function, remains elusive.

Mammalian YKL-40 is classified as a family 18 glycoside hydrolase based on high homology with this well conserved class of enzymes in the CAZy database (10–12). Although similar in structure to family 18 glycoside hydrolases, YKL-40 lacks catalytic activity as a result of substitution of the glutamic acid and aspartic acid motif typical of catalytically active family 18 hydrolases, rendering YKL-40 a lectin, a non-catalytic sugar-binding protein. Structural evidence suggests that YKL-40 exhibits at least two functional binding regions (10). The primary binding cleft has nine binding subsites lined with aromatic residues compatible with carbohydrate binding (Fig. 1). A putative heparin-binding site, located within a surface loop, has also been suggested (Fig. 1), although in vitro binding affinity studies have been unable to conclusively demonstrate this (11).

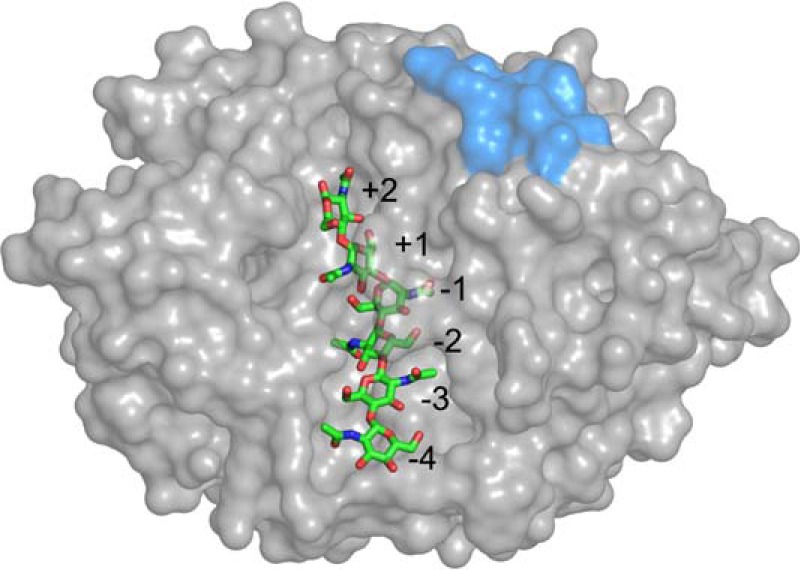

FIGURE 1.

Surface representation of YKL-40 showing the binding cleft with a bound hexamer of chitin. Binding sites +2 through −4 are numbered. Sites −5, −6, and −7 have also been identified but are not shown. The putative heparin-binding site is shown in blue.

Binding affinity and structural studies reveal that chito-oligosaccharides are natural substrates (6, 10, 11). In line with family 18 glycoside hydrolases, YKL-40 uniquely binds short and long chito-oligomers, indicating preferential site selection based on affinity (10). Chitohexaose binding has also been purported to induce conformational changes in YKL-40 (10), although this has not been observed in all structural studies (11). Lectin binding niches are widely believed to be “preformed” to the preferred ligand, exhibiting little conformational change upon binding (13, 14). Despite apparent affinity, chitin is not a natural biopolymer within mammalian or bacterial cells, and the presence of chitin or chito-oligosaccharides in mammals is likely related to fungal infection (15). The noted up-regulation of YKL-40 in response to inflammation lends credence to the argument that YKL-40 functions as part of the innate immune response in recognition of self from non-self (6, 16); however, high expression levels of YKL-40 in carcinoma tissues suggest function beyond the innate immune response may also exist (17, 18). The extracellular matrix is comprised of a mesh of proteoglycans (protein-attached glycosaminoglycans), polysaccharides, and fibers including collagen. An alternate theory to the pathogenic protection function is that a closely related polysaccharide, instead of chitin, plays the role of the physiological ligand in mediating cellular function (11).

Despite the structural similarity between chito-oligosaccharides and the proteoglycan carbohydrate monomers, little evidence of polysaccharide binding beyond the original structural studies exists (10, 11). In fact, we are aware of only one other study focusing on the molecular-level mechanism of carbohydrate binding in YKL-40 (19). From a bioinformatics and structural comparison of YKL-40 to a similar chi-lectin, mammary gland protein 40 (20), the authors propose an oligosaccharide binding mechanism that involves tryptophan-mediated gating of the primary carbohydrate binding site (Fig. 1) (19). However, in lieu of a dynamics-based investigation, little can be concluded about the binding mechanism of YKL-40 ligands other than chito-oligosaccharides, and conformational changes relative to binding are inaccessible. From protein purification techniques, namely heparin-Sepharose chromatography, we also know that YKL-40 reversibly binds heparin (7, 11, 21); however, affinity data for this interaction do not exist. Based on the interaction with heparin, it is reasonable to hypothesize heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans, existing as part of the extracellular matrix construct, are potential physiological ligands. Visual inspection of the protein structure suggests that heparan sulfate fragments may be easier to accommodate within the carbohydrate-binding site than heparin itself (11). It follows that other structurally similar carbohydrate fragments would bind with similar affinity in a comparable mechanism.

The association of YKL-40 with ailments such as arthritis, fibrosis, and joint disease is suggestive of molecular-level interactions with connective tissue and thus collagen (22–26). Motivated by understanding the physiological role of YKL-40 in connective tissue remodeling and inflammation, Bigg et al. (9) investigated association of YKL-40 with collagen types I, II, and III using affinity chromatography to confirm binding to each type. The authors report YKL-40 specifically binds to all three collagen types. Additionally, the authors used surface plasmon resonance to confirm binding to collagen type I. Unfortunately, the reported affinity constants were inconsistent across experiments as a result of aggregation. Nevertheless, the work clearly indicates that YKL-40 is capable of binding collagen. This further confounds the question of mechanism when considering physiological ligands, because YKL-40 is capable of binding both protein and carbohydrates.

Understanding the mechanism and affinity by which YKL-40 binds ligands is crucial to our understanding of its physiological function. This knowledge will serve as a foundation for future campaigns toward rational development of a potent antagonists enabling cell biological study and addressing YKL-40 as a therapeutic target. To accomplish this goal, we must describe the molecular level mechanisms governing the interaction of YKL-40 with both polysaccharide and collagen-like polypeptides and quantitatively evaluate affinity. In this study, we used classical molecular dynamics (MD)2 simulations to differentiate modes of ligand recognition and specificity. Using free energy perturbation with replica exchange molecular dynamics (FEP/λ-REMD) and umbrella sampling MD, we quantitatively determined affinities overcoming the experimental difficulties encountered thus far. As physiological ligands, we considered several options within both the polysaccharide and proteinaceous classes. Below, we provide a brief description of each carbohydrate ligand considered, as well as justification for consideration of the collagen-like models.

Polysaccharides

We selected polysaccharides for this study based on their similarity to chito-oligomers, as well as natural occurrence in mammalian cell walls and/or the extracellular matrix. The chito-oligomer from structural studies was included as a control (10, 11). Chitin is a naturally occurring biopolymer comprised of repeating N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (GlcNAc) monomeric units connected by β-1,4-glycosidic linkages (Fig. 2). The central ring of the monomer, a six-membered pyranose, is common to a number of carbohydrates including glucose. Given the chemical similarity, as well as the general presence of glucose in mammalian cells as a form of energy, a hexameric cello-oligomer was also examined as a potential physiological ligand, despite its unlikely presence among mammalian glycosaminoglycans.

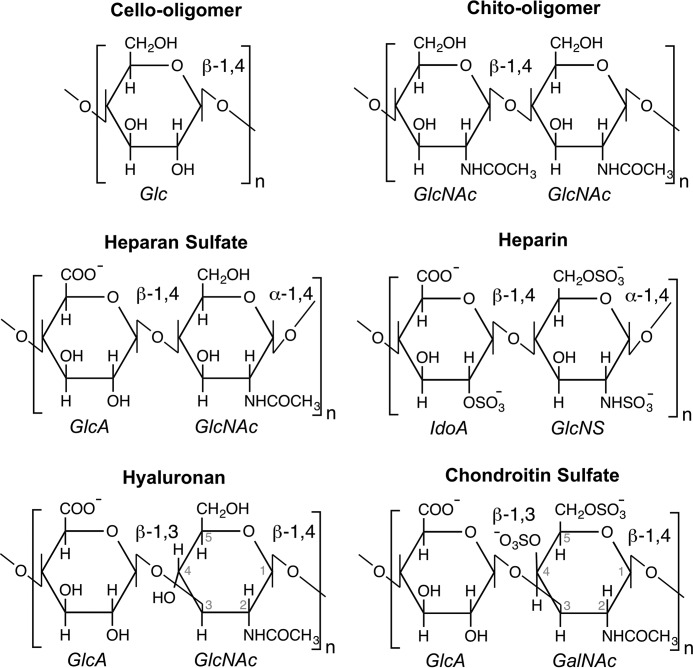

FIGURE 2.

Monomeric units of the polysaccharides considered as potential physiological ligands of YKL-40: cellohexaose, chitohexaose, heparan sulfate, heparin, hyaluronan, and chondroitin sulfate. The chito-oligomer is a polymer of β-1,4-linked GlcNAc monomers. Heparan sulfate was modeled as a β-1,4, α-1,4-linked chain of GlcA and GlcNAc. Heparin was represented as the β-1,4, α-1,4-linked oligomer of GlcA and GlcNS. Hyaluronan and chondroitin sulfate are β-1,3, β-1,4-linked oligomers; the former consists of GlcA and GlcNAc, and the latter consists of GlcA and GalNAc. GlcA, β-d-glucuronic acid; IdoA, α-d-iduronic acid; GlcNS, N-sulfo-α-d-glucosamine; GalNAc, N-acetyl-β-d-galactosamine.

As described above, YKL-40 binds heparin, and thus, likely also binds heparan sulfate. Heparan sulfate, a less sulfated form of heparin, is a polysaccharide found in abundance in the extracellular matrix and at the cell surface (27). Heparan sulfate is constructed from a repeating disaccharide of β-d-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-α-d-glucosamine (Fig. 2). Of all the glycosaminoglycans, heparan sulfate is the most structurally complex. At least 24 different combinations of the disaccharide monomer exist, with differences arising as a result of variation in both isomer and degree of side chain sulfation (28). Additionally, the heparan sulfate polysaccharide can exhibit both sulfated and unsulfated domains. Physiologically, the unsulfated disaccharide β-d-glucuronic acid (1, 4) N-acetyl-α-d-glucosamine is the most prevalent form of heparan sulfate (28). Focusing on the most relevant physiological ligands, we examined the fully sulfated form heparin and the unsulfated form heparan sulfate.

Hyaluronan is a particularly interesting glycosaminoglycan relative to this study, because chito-oligosaccharides are precursors to hyaluronan synthesis in vivo (29–31). The structural relationship of these two molecules is such that binding mechanisms may be similar at alternating binding sites. Hyaluronan is a polysaccharide of a repeating β-d-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosamine disaccharides connected by alternating β-1,3- and β-1,4-glycosidic linkages (Fig. 2). As with heparan sulfate, hyaluronan is also a glycosaminoglycan comprising the extracellular matrix. At extracellular pH, the carboxyl groups of glucuronic acid are fully ionized, giving the ligand an overall negative charge under typical physiological conditions (32).

Finally, we consider chondroitin sulfate, which is also a glycosaminoglycan prevalent in mammals. The primary structural units of chondroitin sulfate are a repeating β-d-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-α-d-galactosamine disaccharides connected by alternating β-1,3- and β-1,4-glycosidic linkages (Fig. 2). As with heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate exists in variably sulfated types (33); we have selected the C4 and C6 sulfated variant of chondroitin sulfate polysaccharide as a model.

Collagen-like Peptide Models

Collagen has also been considered as a potential physiological ligand based on the noted affinity and participation of YKL-40 in collagen fibril formation (9). Collagen, unlike the other potential physiological ligands, is a macromolecular protein with a triple helix structure. There are at least 27 distinct types of human collagen, forming a variety of biological networks, all of which are constructed of a basic Gly-Xaa-Yaa repeating amino acid sequence (34). Generally, the unspecified amino acids, Xaa and Yaa, are proline and hydroxyproline, respectively.

Model collagen peptides have been observed in two different symmetries: the original Rich and Crick model with 10/3 symmetry (10 units in 3 turns) and the 7/2 symmetry of a more tightly symmetrical triple helix (35–37). On the molecular scale, collagen type will have relatively little impact on binding to YKL-40. However, symmetry may have an impact on hydrogen bonding in the binding site, and thus, overall affinity, which will provide unique insight into physiological relevance. To date, model collagen peptides of a true 10/3 symmetry have not been reported. Rather, the peptides either have a 7/2 helical pitch or are somewhat “intermediate” in symmetry leading some to believe that the 7/2 symmetry is representative of the true collagen helical structure (38). However, it is not known how universally true this hypothesis is because the structures of model peptides capture just a small subsection of the larger macromolecular structure (39).

With a broad range of possible collagen architectures, we have selected four representative model collagen peptides whose structures are both available from crystallographic evidence and span the 10/3 and 7/2 symmetries to the greatest possible extent. The first collagen peptide considered is that of the basic collagen peptide model, PDB code 1CAG (40). The reported 1.9 Å resolution structure exhibits a single Gly to Ala substitution and 7/2 symmetry overall. Near the substitution site, the helix relaxes somewhat from 7/2 symmetry, although not so much as to change overall symmetry. The second collagen model peptide we consider is a variation of the 1CAG peptide, where we reverted the alanine substitution to its native glycine. Minimization of this structure returns the helix to full 7/2 symmetry; we refer to this peptide as “native 1CAG” here. The third model represents a segment from type III homotrimer collagen with approximate 10/3 symmetry in the middle part of the helix (PDB code 1BKV) (35). This middle part of the 1BKV model peptide, also referred as the T3–785 peptide, has an imino acid-poor sequence of GITGARGLA. Our fourth model, 1Q7D, is a triple helical collagen-like peptide sequence including a hexapeptide Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Glu-Arg (GFOGER) motif in the middle (41); this motif is not sufficiently long to exhibit 10/3 symmetry, exhibiting, rather, an intermediate degree of 7/2 helical symmetry. This 1Q7D model is known to bind the integrin α2β1-I domain protein (42), and the GFOGER motif is found in the α1 chain of type I collagen.

Experimental Procedures

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

MD simulations were constructed starting from the chitohexaose-bound YKL-40 structure (PDB code 1HJW) deposited by Houston et al. (10). The apo simulation simply removed the chito-oligomer from the primary binding cleft. The N-linked glycan captured in the YKL-40 structure, at Asn60, was included in system preparation. Because crystal structures of YKL-40 bound to other polysaccharides are not available, we used the structural similarity of polysaccharides as the basis for modeling the remaining polysaccharides in this investigation. In the case of cellohexaose, hyaluronan, heparan sulfate, heparin, and chondroitin sulfate, we located the central ring atoms of the ligand backbone in the same location as that of the original chitohexaose. Appropriate pyranose side chains and glycosidic linkages (Fig. 2) were added using CHARMM internal coordinate tables to construct the remainder of the sugar residue (43). All polysaccharides were described using the CHARMM36 carbohydrate force field (44–46). The missing force-field parameters for N-sulfated glucosamine (supplemental Fig. S1) in heparin were developed using the force-field Toolkit plugin for VMD (47, 48). Details of this parameterization and output parameters (supplemental Table S2) are reported in the supplemental materials.

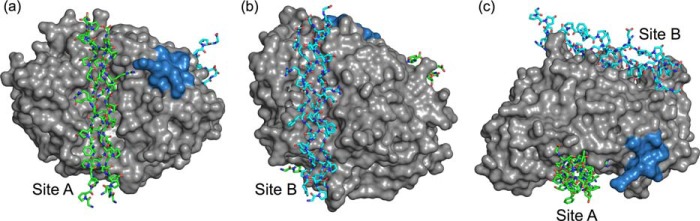

Construction of the collagen-bound YKL-40 models required docking calculations to appropriately position the ligand. The collagen peptides are significantly larger than any of the carbohydrate ligands; thus, it is unlikely that a collagen molecule occupies the primary YKL-40 binding site in the same manner as chito-oligomer. Standard affinity-based docking calculations, such as the ones performed in AutoDock, are not feasible for determination of an initial collagen-binding domain given the size and flexibility of the triple helix structures. Rather, the collagen peptides were docked on the basis of molecular shape complementarity using the online web server PatchDock Beta version 1.3 (49, 50). In the case of each of the four collagen-like model peptides, PatchDock predicted two potential occupancies along the surface of YKL-40, site A and site B. Binding site A corresponds to the primary carbohydrate-binding domain of YKL-40; however, the collagen ligand was not as deeply entrenched in the cleft as chitohexaose. Binding site B is located on the opposite side of YKL-40 from the primary binding cleft. Thus, for each collagen-like peptide, two MD simulations were constructed representing the two potential binding sites. Fig. 3 illustrates the results of the docking with predicted collagen binding sites A and B for the 1Q7D collagen-like model peptide.

FIGURE 3.

Molecular shape complementarity docking calculations predict collagen-like peptides will bind to YKL-40 in two possible orientations. a, the front view of YKL-40 (gray surface) with collagen docked in site A (green stick). b, the back view where collagen is docked in site B (cyan stick). c, top view of YKL-40 illustrating relative positions of binding sites. The putative heparin-binding subsite is shown in blue surface to aid in visualization of relative orientation of the protein·protein complexes. This particular figure shows the integrin-binding collagen peptide, 1Q7D (41), in the predicted binding sites along the surface of YKL-40; similar docking was carried out for other collagen models.

The constructed protein-ligand systems were minimized in vacuum and subsequently solvated with water and sodium ions. Using CHARMM (43), the solvated systems were extensively minimized and heated to 300 K for 20 ps, which was followed by MD simulation for 100 ps in the NPT ensemble. The coordinates following density equilibration were used as a starting point for 250 ns of MD simulation in the NVT ensemble at 300 K using NAMD (51). Explicit procedural details are provided in the supplemental materials.

Free Energy Calculations

FEP/λ-REMD

Free energy perturbation with Hamiltonian replica exchange molecular dynamics (FEP/λ-REMD) was used to calculate the absolute free energy of binding the polysaccharide ligands to YKL-40 (52, 53). This protocol uses Hamiltonian replica exchange as a means of improving the Boltzmann sampling of free energy perturbation calculations. The parallel/parallel replica exchange MD algorithm in NAMD was implemented as recently described (51, 54). The free energy calculations performed using this approach were accomplished through two separate sets of free energy calculations following the thermodynamic cycle illustrated in supplemental Fig. S2. To obtain each binding free energy, ΔG, the bound carbohydrate ligand was first decoupled from the solvated protein·carbohydrate complex to determine ΔG1. The second calculation entailed decoupling the solvated oligosaccharide from solution into vacuum to obtain ΔG2. The difference between the two values, ΔG2 − ΔG1, gives the absolute free energy of binding the given ligand to YKL-40.

In each free energy calculation, five separate terms contribute to the potential energy of the system: the non-interacting ligand potential energy, repulsive and dispersive contributions to the Lennard-Jones potential, electrostatic contributions, and the restraining potential. In each calculation, the ligand was decoupled from the system by thermodynamic coupling parameters controlling the non-bonded interaction of the ligand with the environment. The parameters decoupled the ligand in a four-stage process, wherein the coupling parameters defined replicas that were exchanged along the length of the alchemical pathway. This decoupling has been described in detail previously (54) and is also reported in the supplemental materials. A total of 128 FEP replicas were used, and a conventional Metropolis Monte Carlo exchange criterion governed the swaps throughout the replica exchange process (53). The free energy of binding was determined from 20 consecutive, 0.1-ns simulations of each corresponding system, where the first 1 ns of data were discarded as equilibration. One standard deviation of the last 1 ns of simulation data were used to obtain an estimate of error. Additional details about these calculations are described in the supplemental materials.

Umbrella Sampling

Convergence challenges make FEP/λ-REMD inappropriate for determining the binding free energy of the much larger and more flexible collagen-like model peptides. Thus, umbrella sampling was used to determine the work required to detach the collagen ligands from the shallow clefts of YKL-40. Over the entire reaction coordinate, this value equates to binding affinity, enabling relative comparison of collagen peptide affinity. The MD umbrella sampling simulations used a native contacts-based reaction coordinate analogous to that defined by Sheinerman and Brooks (55) and as implemented in recent cellulose decrystallization studies (56, 57). Here, a native contact was defined as a YKL-40 protein residue within 12 Å of a collagen peptide residue; distance was defined by center of geometry of a given residue. The cutoff distance was selected to be larger than the non-bonded cutoff distance, ensuring that the collagen ligand was no longer interacting with YKL-40. Additionally, the water boxes of the collagen-YKL-40 systems were made bigger to accommodate the required separation distance.

The change in free energy was determined as a function of the reaction coordinate, ρ, formulated as the weighted sum of the states of the native contacts. The initial coordinates of the bound systems were selected from 250-ns equilibrated snapshots. The initial number of native contacts and their weights were calculated from these snapshots. An initial reaction coordinate of 0 (normalized) corresponds to this initial condition, and a final reaction coordinate of 1 corresponds to all of the native contacts being outside the 12-Å cutoff (i.e. the ligand is decoupled and freely sampling the bulk). The reaction coordinate was divided into 20 windows evenly spaced along the reaction coordinate, and each window was sampled for 5 ns, where the reaction coordinate was maintained at the specified value using a harmonic biasing force with the force constant of 41,840 kJ/mol. The potentials of mean force profiles were calculated using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM software), and error analysis was performed using bootstrapping. A detailed listing of all the simulations and free energy calculations performed as part of the objectives of this study is provided in supplemental Table S1.

Results and Discussion

Protein-Polysaccharide Binding in YKL-40

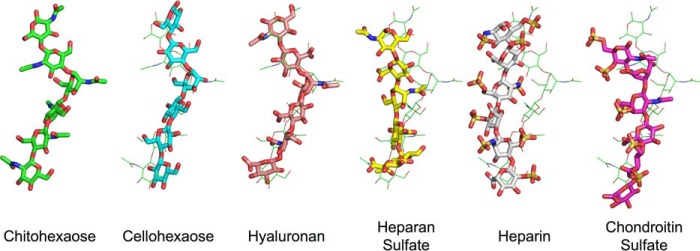

MD simulation suggests that of the six polysaccharide oligomers investigated, only three bind in a stable fashion in the primary carbohydrate binding site of YKL-40. The three potential polysaccharide physiological ligands at this site include chitohexaose, cellohexaose, and hyaluronan. In the section that follows, we will describe the dynamics of chitohexaose, cellohexaose, and hyaluronan binding to YKL-40. The remaining three ligands—heparin, heparan sulfate, and chondroitin sulfate—were dislodged from the binding site over the course of MD simulations. The α-1,4-glycosidic linkages in heparin and heparan sulfate, instead of β-1,4, modifies the relative orientation of disaccharide monomers from that of the chito-oligosaccharide. The NMR solution structure of heparin (PDB code 1HPN) shows that the relaxed conformation is semi-helical (59), which cannot be feasibly accommodated in the conserved, narrow carbohydrate binding site of YKL-40. Heparan sulfate suffers from similar steric constraints posed by the relaxation driving force. The bulky sulfated side chains of heparin introduce further steric hindrance and, in the case of heparin and chondroitin sulfate, unfavorably strong electrostatic interactions resulting from negatively charged moieties inconveniently located along the cleft (i.e. without a co-located, oppositely charged protein residue) eject the ligands from the cleft.

In the cases of heparin, heparan sulfate, and chondroitin sulfate, the ligands quickly “relax” from the initial wide V-shaped conformation as they are expelled from the cleft by charge- and steric-based effects. Relaxation of the sugar from the initial binding pose is sufficient to initiate loss of critical non-bonded interactions along with a subsequent reduction in affinity (Fig. 4). Within 25 ns, heparin, heparan sulfate, and chondroitin sulfate were expelled from the cleft into bulk solution. Each of the three ligands capable of binding with the primary binding cleft maintained the −1 boat conformation over the entire simulation. Chitohexaose and cellohexaose remained in the binding cleft over the entire 250-ns MD simulation while maintaining the initial wide V shape. Hyaluronan developed a sharp V shape within a few nanoseconds and maintained this conformation within the binding cleft for the remainder of the simulation (supplemental Fig. S6); this is primarily due to variation in glycosidic linkage, where hyaluronan exhibits a β-1,3-linkage within the monomer instead of the β-1,4-linkage of cello- and chitohexaose. Also, comparison of the equilibrated chitohexaose- and hyaluronan-bound structures disabuses one of the notion that similar binding mechanisms exist at alternate binding sites, because only the −1 site pyranose appears to maintain similar side chain orientation.

FIGURE 4.

Relaxation of the polysaccharide ligands in the primary binding cleft of YKL-40. Each ligand is shown after a 100-ps equilibration in a thick stick representation. For comparison, the chito-oligomer, in its equilibrated conformation, is shown in thin green lines behind each oligosaccharide. The YKL-40 protein has been aligned such that each oligosaccharide is oriented in the same manner; although YKL-40 is not shown for visual clarity. Heparan sulfate, heparin, and chondroitin sulfate relax significantly from the initial distorted conformation.

The native distorted conformation is characteristic of glycoside hydrolase pyranose binding behavior in the −1 site (Fig. 4) (60). In solution, polysaccharide pyranose moieties adopt the energetically favorable chair conformation (61); however, when bound to an enzyme, the active sites of catalytically active glycoside hydrolases distort the pyranose ring in the −1 binding subsite into a less energetically favorable conformation, such as a boat or skew conformation (62–65), priming the substrate for hydrolytic cleavage. Interestingly, the chitohexaose ligand bound in the primary binding site of YKL-40 exhibits a boat conformation despite not being catalytically active (10). This suggests that the sugar distortion in the −1 binding site contributes to ligand binding as well as catalysis, because there is no evolutionary requirement to overcome an activation energy barrier in catalytically inactive lectins. A recent study of a homologous chitinase suggested that −1 pyranose relaxation reduces binding affinity and affords the ligand more flexibility and entropic freedom (66), which is consistent with our findings from the 250-ns MD here.

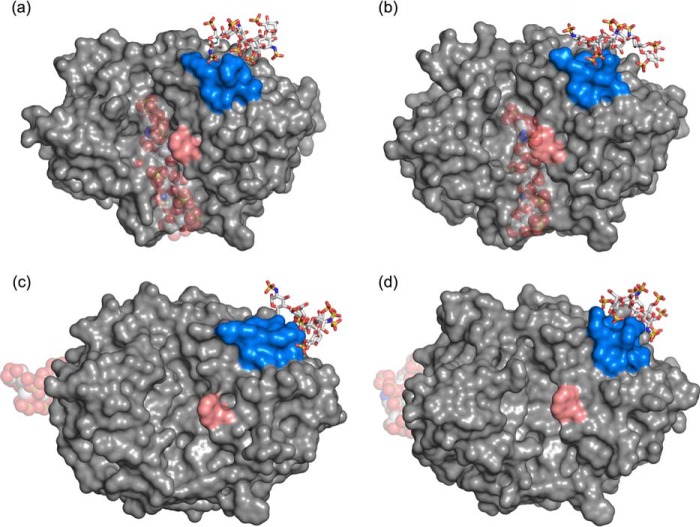

Putative Heparin-binding Site

Despite the fact that the heparin oligomer could not be accommodated by the YKL-40 binding cleft, MD simulations do suggest that the oligomer interacts with the surface of YKL-40 at a putative heparin-binding site (Fig. 1). After ejection from the primary binding site, the oligomer spontaneously binds to the YKL-40 heparin-binding site (supplemental Movie S1). To address the significance of this unanticipated event, we performed three additional independent MD simulations of the YKL-40/heparin system: one with a new random number seed, although in the same configuration, and two additional simulations with the ligand randomly placed in solution (supplemental Movie S2). In each case, the heparin oligomers were capable of finding and binding to a group of charged residues at the surface of YKL-40 (Fig. 5); these were the basic residues of a putative heparin-binding site, GRRDKQH, at positions 143–149. Interestingly, this domain follows a consensus protein sequence, XBBXBX (where B is a basic residue and X is any non-basic amino acid), that is noted for its ability to recognize polyanions like heparin (67). In all four cases, heparin recognized the binding site within 25 ns of MD simulation (Fig. 5), occasionally visiting other moderately basic surface locations before localizing around the GRRDKQH motif. The strong electrostatic interaction arose from the dynamic formation of salt bridges between either the sulfate or the carboxyl groups of the heparin oligosaccharide and the side chains of the basic amino acids (supplemental Table S3). Lys155 and Lys193 also exhibit large, favorable interactions with heparin, interacting with the opposite end of the polysaccharide ligand as it binds at the surface. Coupled with experimental observation of heparin affinity, our MD simulations suggest a non-specific, surface-mediated binding interaction between YKL-40 and the extensively sulfated heparin oligomer (10, 11). Although the unsulfated variant, heparan sulfate, did not visit the heparin-binding site, chondroitin sulfate also attached to the putative heparin-binding site in a similar fashion to heparin. Given the chemical similarity of these glycosaminoglycans, i.e. highly sulfated and negatively charged, we anticipate the XBBXBX motif may also routinely appear in chondroitin-binding proteins.

FIGURE 5.

Snapshots from four independent MD simulations of heparin (white stick) binding to a putative heparin-binding site (blue surface) of YKL-40 (gray surface). The primary oligosaccharide binding site of YKL-40 is marked by an aromatic residue shown in salmon surface representation. Transparent spheres illustrate the initial simulation positions of heparin. In two cases, a and b, the heparin ligand was initially bound in the primary YKL-40 binding site. In both cases, the ligand was expelled from the primary binding site into solution and located the heparin-binding site through electrostatic interactions. Two additional simulations, c and d, were initialized with the heparin ligand free in solution. Again, the ligands identified the YKL-40 heparin-binding domain through charge-based interactions. The ligand did not specifically bind in a particular conformation. Rather, the ligand dynamically interacted with the heparin-binding domain.

Polysaccharide Ligand Binding Affinity

Each of the three polysaccharides maintaining contact with the primary binding site of YKL-40, cellohexaose (or likely any glucose derivative), chitohexaose, and hyaluronan, are feasible ligands. However, free energy calculations suggest that hyaluronan may preferentially bind with YKL-40 if chitin is not present in the human body as a result of fungal infection. The absolute free energies of binding cellohexaose, chitohexaose, and hyaluronan to YKL-40 were −12.6 ± 3.7, −63.3 ± 12.6, and −106.8 ± 4.6 kJ/mol, respectively. Repulsive, dispersive, and electrostatic components of the free energy changes are tabulated in Table 1. Convergence assessment of the free energy calculations has been provided in supplemental Fig S3. We recently calculated the free energy of solvation for chitohexaose as part of a study on family 18 chitinases (68); this value has been used in our calculation of chitohexaose binding affinity to YKL-40 for computational efficiency. The methods used to calculate solvation free energy of chitohexaose were identical to those described here. Furthermore, the binding free energy of chitohexaose to YKL-40 is in good agreement with that of homologous family 18 chitinases, despite mutation of the catalytic motif in the lectin.

TABLE 1.

Energetic components of the free energy of ligand binding to YKL-40

| System | ΔGrepu | ΔGdisp | ΔGelec | ΔGrstr | ΔGTot | ΔGb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kJ mol−1 | kJ mol−1 | kJ mol−1 | kJ mol−1 | kJ mol−1 | kJ mol−1 | |

| YKL-40 + Cellohexaose | 379.5 ± 3.8 | −382.3 ± 2.1 | −306.6 ± 2.2 | −1.1 | −310.5 ± 3.6 | −12.6 ± 3.7 |

| Cellohexaose | 316.2 ± 1.8 | −287.4 ± 1.3 | −326.7 ± 1.6 | 0 | −297.9 ± 2.8 | |

| YKL-40 + Chitohexaose | 535.9 ± 11.7 | −538.9 ± 4.2 | −407.7 ± 7.5 | −5.5 | −416.2 ± 11.2 | −63.3 ± 12.6 |

| Chitohexaosea | 329.6 ± 4.5 | −306.2 ± 3.0 | −376.3 ± 3.4 | 0 | −352.9 ± 5.9 | |

| YKL-40 + Hyaluronan | 438.1 ± 2.8 | −439.5 ± 1.5 | −1395.9 ± 4.2 | −1.3 | −1398.6 ± 4.3 | −106.8 ± 4.6 |

| Hyaluronan | 333.1 ± 1.4 | −306.0 ± 1.3 | −1318.9 ± 1.5 | 0 | −1291.8 ± 2.5 |

a Hamre et al. (68).

Chitohexaose and cellohexaose are both neutral ligands but display a significant difference in binding affinity to YKL-40. Electrostatic interactions appear to be one of the more significant contributors to the enhanced affinity of chitohexaose over cellohexaose (Table 1). For cellohexaose, the change in the electrostatic component of binding free energy was unfavorable (20.1 ± 2.7 kJ/mol), whereas the same component for chitohexaose was energetically favorable (−31.4 ± 8.2 kJ/mol). In the case of hyaluronan, electrostatic interactions play an even greater role in enhancing affinity of the ligand for YKL-40 (−77.0 ± 4.5 kJ/mol). This increasing electrostatic contribution is reflective of increasing number of electronegative atoms in the side chains of carbohydrates as we go from cellopentaose to chitohexaose to hyaluronan. We observe no significant differences in cellohexaose, chitohexaose, or hyaluronan binding to YKL-40 arising from Weeks-Chandler-Anderson (WCA) dispersion and repulsion (Table 1). This is largely a function of the molecular similarity of the pyranose rings comprising the monomeric units of three oligosaccharides (Fig. 2). The pyranose rings of carbohydrates bound in the active sites of glycoside hydrolases, and by extension the binding clefts of lectins, form carbohydrate-π stacking interactions with surrounding aromatic residues along the clefts (69). In YKL-40, these stacking interactions are formed in the −3 and −1 binding sites with residues Trp31 and Trp352, respectively. Naturally, any polysaccharide ligand capable of binding in the YKL-40 binding cleft will likely exhibit a similarly favorable WCA binding free energy component. In the following section, we expand upon the molecular level interactions that contribute to polysaccharide binding affinity in YKL-40.

Based on these results, it is unlikely that a cello-oligomer would bind in the cleft of YKL-40 over a chito-oligomer, and thus, although there is potential for YKL-40 to bind a cello-oligomer or glucose, it would not be inhibitory. Hyaluronan, on the other hand, likely competes with chito-oligomers in binding, which is due in large part to the electrostatic favorability of the charged side chains of hyaluronan in the YKL-40 binding cleft. Clinical data support hyaluronan as a biomarker for cancer prognosis and inflammation (32, 70), the same events in which YKL-40 appears at elevated serum levels (5). To our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating the co-existence of YKL-40 and hyaluronan. The cell receptor protein CD44 has been implicated in hyaluronan binding interactions and is also involved in confounding scenarios, both aggravating and improving inflammation (71). Sequence alignment of YKL-40 with the hyaluronan-binding domain of human CD44 (72), using BLASTP 2.3.0 (73), shows no homology, further suggesting that this YKL-40-hyaluronan binding is different from previously known hyaluronan-binding proteins (74).

Polysaccharide Binding Dynamics

YKL-40 is highly homologous with carbohydrate-active enzymes found in glycoside hydrolase family 18 (12, 75). Despite lacking catalytic ability, the primary polysaccharide binding site of YKL-40 exhibits remarkable similarity to these family 18 chitinases. As such, one may reasonably expect that ligand binding within this family will demonstrate similar trends, regardless of evolutionary origin. Indeed, we observe that chitohexaose, cellohexaose, and hyaluronan binding in the primary binding site of YKL-40 follow a general pattern common to carbohydrate-active enzymes. Namely, that ligand binding interactions are mediated by carbohydrate-π stacking interactions with aromatic residues, and hydrogen bonding interactions are critical to overall ligand affinity and stability. We investigate these trends quantitatively through analysis of the MD simulation trajectories, including root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the protein, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of both the protein and the ligands over the course of the simulation, hydrogen bonding analysis, degree of solvation of the ligand, and interaction energy of the ligand with the protein.

Cellohexaose, chitohexaose, and hyaluronan binding in the primary YKL-40 binding site did not adversely affect protein dynamics. In each case, binding the polysaccharide ligand did not significantly disturb the protein backbone (i.e. protein fold), and the ligand remained relatively unperturbed over the course of the simulation. The relatively consistent RMSD of the protein backbones suggests that the simulations reached a local equilibrium (supplemental Fig. S4a). As with the RMSD calculation, the RMSF of the protein backbone suggests that the binding of polysaccharides does little to disturb the overall protein conformation (supplemental Fig. S4b). Additionally, we did not observe significant conformational changes in the carbohydrate-binding site of YKL-40 before or after ligand binding (supplemental Fig. S5). More details of protein dynamics and conformational changes have been provided in the supplemental text.

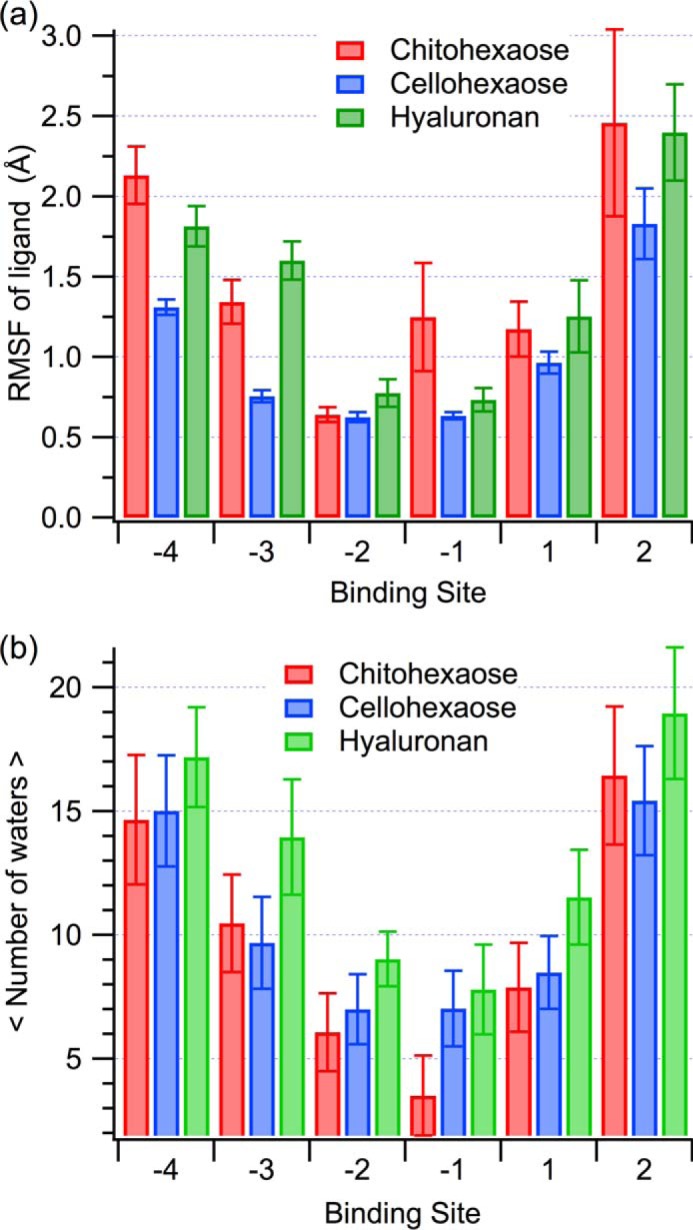

The RMSF of the ligand, averaged over 250 ns as a function of binding site, provides a measure of relative ligand stability. Error was estimated by block averaging over 2.5-ns blocks. Ligand stability over the course of the simulation suggests hyaluronan is as stable, if not more so, as chitohexaose in the primary binding site (Fig. 6a); however, cellohexaose appears to be more stable relative to the two other ligands at the ends of the binding cleft. This latter finding is a function of the length of the side chains attached to the pyranose rings of each of the ligands. Of the three carbohydrates, the cello-oligomer has the shortest side chains, and thus, the ligand fluctuates less because it does not need to rearrange as significantly to induce binding. As shown above, this does not necessarily correspond to the most thermodynamically preferential ligand, and lower RMSF could also be interpreted hypothetically as loss of translational and conformational freedom, resulting in unfavorable entropic contribution.

FIGURE 6.

a, RMSF of the polysaccharide ligands on a per-binding-subsite basis. The error bars were calculated using block averaging over 2.5 ns. b, average number of water molecules within 3.5 Å of each ligand monomer. The error bars represent one standard deviation.

The hydrogen-bonding partners of chitohexaose, cellohexaose, and hyaluronan are quite different, largely as a result of the conformational change of hyaluronan (supplemental Table S4). Defining a hydrogen bond as a polar atom within 3.4 Å and 60° of a donor, we identified the formation of donor-acceptor pairs and percent occupancy of these hydrogen bonds between the protein and each carbohydrate moiety over the course of the 250-ns MD simulations (supplemental Table S4). As described above, hyaluronan formed a sharp V shape in the polysaccharide binding cleft, which minimized steric hindrance and, in turn, modified accessible hydrogen bonding partners relative to chito- and cellohexaose. Hydrogen bonds at the +1 site, between glucuronic acid and Asp207, Arg263, and Tyr141, stabilized the hyaluronan conformation (supplemental Table S4). In the −1 subsite, chitohexaose primarily hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Tyr206 and the main chain of Trp99. In the cases of both cellohexaose and hyaluronan, the interaction with Tyr206 was abolished and instead supplemented by Trp99 alone. In the −2 subsite, the oxygen of the chitohexaose acetyl forms a long-lived hydrogen bond with the indole nitrogen of the buried Trp352; neither hyaluronan nor cellohexaose interact with the −2 site through this tryptophan. Rather, Trp31, which stacks with the pyranose in the −3 subsite, acts as a hydrogen donor to the −2 subsite glucuronic acid side chain of hyaluronan. In the case of cellohexaose, the main chain of a solvent-exposed asparagine, Asn100, almost exclusively mediates hydrogen bonding in the −2 site. The +2, −3, and −4 binding subsites exhibit less frequent hydrogen bonding between the ligand and the protein, and there is little consistency in bonding partners across ligands. Certainly, these variations will manifest in enthalpic contributions to ligand binding, because even a single hydrogen bond may account for 4–29 kJ/mol of binding free energy in biological systems (76, 77); such is likely the case for cellohexaose and chitohexaose binding to YKL-40, where the latter exhibits both greater hydrogen bonding capability and a more favorable binding free energy.

Key aromatic residues, Trp31, Trp99, and Trp352, play a significant role in binding all three oligosaccharides. Notably, these tryptophans are conserved in other lectins, including mammary gland protein (MGP-40) and mammalian lectin Ym1 (20, 78). According to previous structural studies, these aromatic residues form hydrophobic stacking interactions with pyranose moieties at the −3, +1, and −1 binding subsites, respectively (11). As mentioned above, this carbohydrate-π stacking was observed across the three polysaccharide ligands as a result of the chemically similar carbohydrate “backbone” of pyranose rings. However, at the +1 site of hyaluronan, the stacking interaction with Trp99 was not maintained. Instead, prominent hydrogen bonding forces the +1 pyranose ring in an orientation that is perpendicular to aromatic Trp99 (supplemental Fig. S6). Nevertheless, the similarity in WCA contributions to binding free energy for all three polysaccharides suggests that this +1 site stacking interaction weakly contributes to the overall binding free energy.

The degree to which the binding cleft of YKL-40 was accessible to water molecules did not change significantly with the bound polysaccharide. The degree of ligand solvation was determined by calculating the average number of water molecules within 3.5 Å of a given pyranose ring over the course of the simulations (Fig. 6b); error is given as one standard deviation. Chitohexaose and cellohexaose display similar degrees of solvation across the length of the cleft. Hyaluronan allows a moderate increase in degree of solvation of the cleft by comparison to chitohexaose, across the −3 and +1 subsites, where its sharp V shape again contributes to variation in behavior. Given the similarity in solvent accessibility within the binding cleft regardless of ligand, it is unlikely that entropic contributions from solvation play a role in the observed differences in ligand binding free energy.

Protein-Protein Binding in YKL-40

Based on biochemical characterization, it is clear that YKL-40 functionally interacts with collagen. For example, Bigg et al. (9) uncovered the ability of YKL-40 to specifically bind types I, II, and III collagen fibers, and Iwata et al. (79) recently discovered that YKL-40 secreted by adipose tissue inhibits degradation of type I collagen by matrix metalloproteinase-1 and further stimulates the rate of type I collagen formation. However, a lack of structural evidence has precluded development of an understanding of the molecular nature of these interactions. Using molecular docking, MD simulation, and free energy calculations, we describe interactions of four collagen-like peptides with two putative protein-binding sites along the surface of YKL-40. The selection of model peptides, as well as multiple binding sites, encompasses as many potential binding modes as feasible to describe protein-protein binding dynamics and relative affinity of YKL-40 for collagen.

Ligand Binding Dynamics and Comparison of Model Collagen-like Peptides

Dynamics of the collagen-like peptide ligands varies with both binding site and the pitch of the triple helix. Root mean square deviation illustrates the relative stability of each collagen peptide in each of the two binding sites, A and B (supplemental Fig. S7). Although the molecular docking results in very close contact between collagen and YKL-40 (Fig. 4), such that collagen appears to be almost buried in the primary carbohydrate-binding site of YKL-40, minimization and MD simulation results in the slight rise and shift in the position of collagen for every model at binding site A. Each of the four ligands maintains association with the binding site A over the course of 250 ns, although with slightly different protein-protein contacts with YKL-40 (Fig. 7). Native 1CAG, 1BKV, and 1Q7D attained relative stability in a position not significantly different from the initial docked position, but the 1CAG peptide (supplemental Movie S3), with disrupted helical content resulting from the glycine to alanine mutation, required an adjustment in pitch before associating with YKL-40. This relative change in position is shown in the RMSD of the peptides during first 50–100 ns before stabilization (supplemental Fig. S7a). Binding site B accommodates helical pitches of 7/2 collagen peptides, because native 1CAG and 1Q7D associated with YKL-40 with very little change in orientation relative to the initial docked positions. The 1CAG ligand was expelled from binding site B, as was the somewhat imperfect 10/3-pitched 1BKV peptide. This suggests that YKL-40 may avoid physiological interactions with certain collagen fibril domains, especially those having imperfect helical pitches. The integrin-binding collagen-like peptide 1Q7D demonstrated the greatest stability among collagen peptides in both binding sites (supplemental Fig. S7) and formed more native contacts with YKL-40 than the other three collagen peptides at binding site A (Fig. 7). We anticipate that the GFOGER motif plays substantial role in mediating the interaction of this collagen peptide with YKL-40.

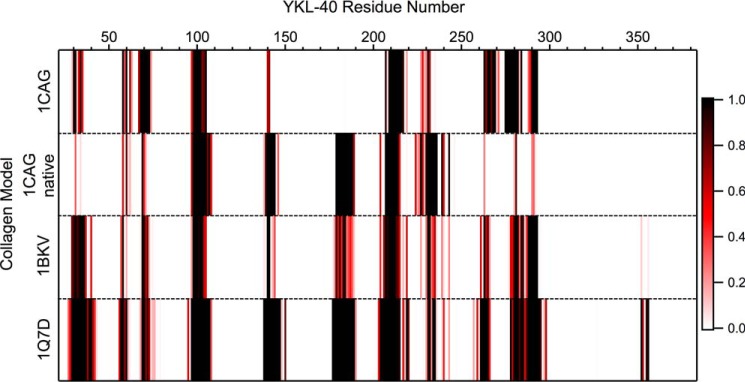

FIGURE 7.

Native contact analysis of each collagen-like peptide model binding to YKL-40 at site A. The color scale represents the normalized frequency (i.e. fractional percentage of frames in which the contact was formed) of the respective YKL-40 residue as a native contact. A native contact was defined as any time a collagen residue was within 12 Å of a YKL-40 residue, where distance was defined by center of geometry of a given residue. Only frames from the last 100 ns of simulation, following a period of equilibration, were considered in this analysis.

Examining the number of native contacts between each collagen peptide and binding site A of YKL-40 reveals several common interaction sites mediate collagen binding and helps narrow down key regions of interest (Fig. 7). YKL-40 residues 69–71, 98–108, 205–215, and 230–235 interact with all four collagen peptides and likely contribute to binding affinity, as we will discuss below. The region of YKL-40 between residues 179 and 189 associates with native 1CAG, 1BKV, and 1Q7D, but not with the original 1CAG, as this peptide with relaxed symmetry needed to adjust its position from docked conformation to stabilize the interactions. The 1Q7D model formed the greatest number of interactions with YKL-40 residues relative to the other three models. Similar native contact analysis for binding site B shows that even N-terminal and C-terminal residues of YKL-40 are involved in collagen binding at binding site B (supplemental Fig. S8). It shows that, unlike binding site A, there is little difference in the number of interactions of model 1Q7D and native 1CAG collagen peptide with the binding site B of YKL-40.

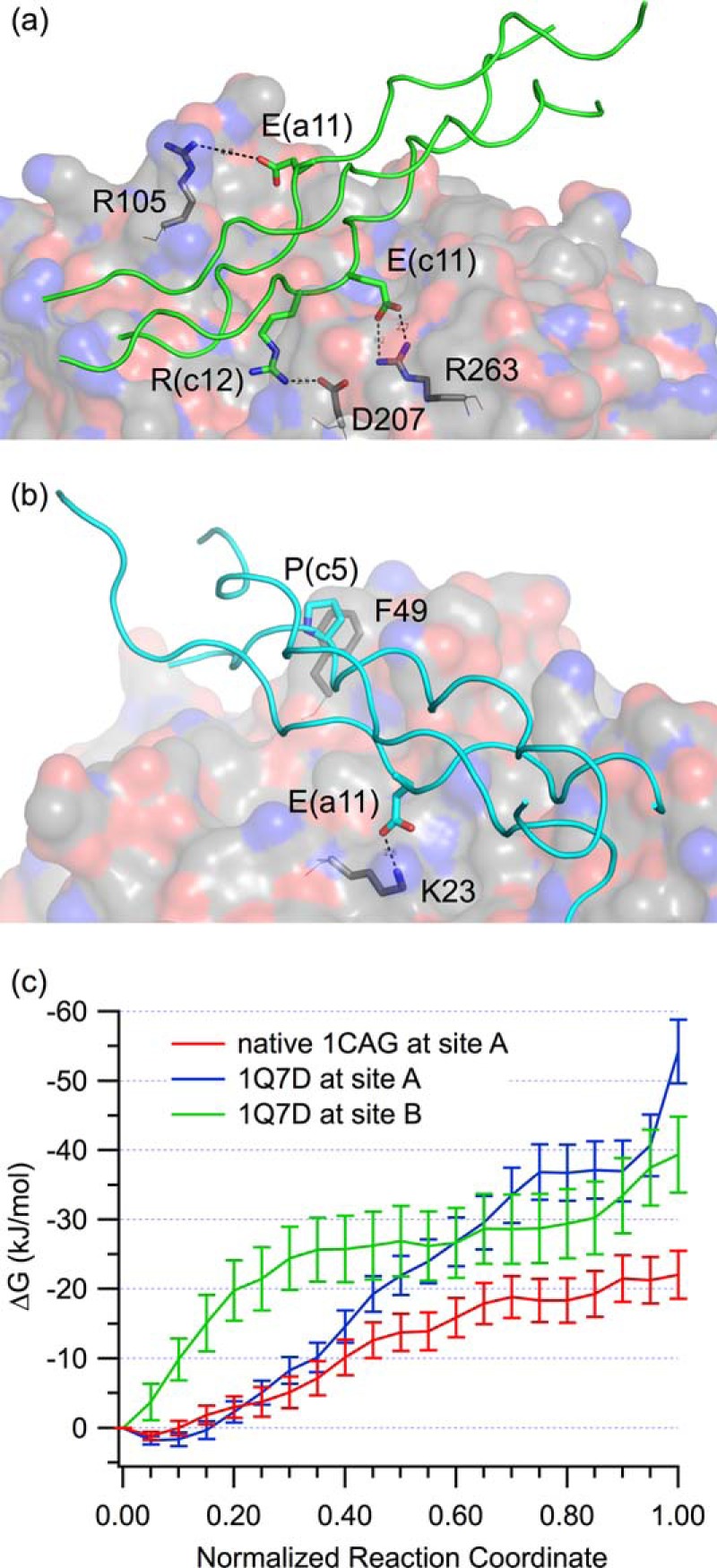

To better understand the interactions collagen makes with YKL-40, identified through the native contact analysis, we calculated electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energies of each YKL-40 residue with each collagen peptide over the 250-ns MD simulations (supplemental Table S5). Visual inspection of the simulations reveals aromatic residues in the binding sites, such as Trp212 and Trp99 in binding site A and Phe49 in binding site B, were involved in aromatic-proline stacking interactions with the collagen triple helices. Such interactions are favorable, occurring because of both hydrophobic effects and interaction between the π aromatic face and the polarized C-H bonds (80). This is illustrated in the van der Waals component of the interaction energy, where at binding site A, Trp69, Trp71, Trp99, Trp212, and Phe234 show substantial favorable interaction with collagen peptides, although the contribution varies with each collagen peptide (supplemental Table S5). Additionally, acidic and basic residues of the integrin-binding GFOGER motif from collagen-like peptide 1Q7D form ionic interactions with the counter-ionic amino acids of YKL-40, also known as salt bridges. Specifically, 1Q7D forms three salt bridges at binding site A and one salt bridge at binding site B (Fig. 8). At site A, Arg105, Asp207, and Arg263 of YKL-40 interact with Glu(a11), Arg(c12), and Glu(c11) of 1Q7D, respectively, where the a, b, or c in the parentheses corresponds to one of the three strands of the collagen model. Notably, Glu(a11), Arg(c12), and Glu(c11) belong to the GFOGER integrin-binding motif. At site B, Lys23 of YKL-40 forms a salt bridge with Glu(a11) of 1Q7D. As anticipated, the GFOGER motif played a substantial role in the interaction of this collagen peptide with YKL-40, but its role was different from that of the integrin binding mechanism, which further involves coordination of a metal ion (42). Nevertheless, salt bridges and hydrophobic contacts are very important in both cases, significantly contributing to the electrostatic component of the binding affinity of this collagen peptide relative to collagen peptides lacking acidic or basic amino acids (e.g. native 1CAG) (supplemental Table S5). The hydroxyl oxygens of hydroxyprolines from 1CAG and native 1CAG appear to be involved in ionic interactions with acidic YKL-40 residues (favorable electrostatic interaction energies; supplemental Table S5), although as a result of hydrogen bonding rather than salt bridge formation. We note that the interaction energies of YKL-40 residues with residues of each collagen model peptide are not conserved as a result of differences in the collagen sequences, particularly in the middle regions consisting of different imino-triplets.

FIGURE 8.

Collagen binding with YKL-40. a, salt bridges formed between the 1Q7D collagen peptide (green cartoon) and binding site A (gray surface). b, salt bridge interactions of the 1Q7D collagen peptide (cyan cartoon) with binding site B (gray surface). c, binding free energy obtained from umbrella sampling MD simulations of the YKL-40-collagen peptide systems, interpreted as negative of PMF to decouple the partners. The collagen peptides in question are 1Q7D (at both sites) and 1CAG (at site A only). The free energy is shown as a function of normalized reaction coordinate, where the reaction coordinate is fraction of native contacts.

From MD simulation, we observe substantial hydrogen bonding between the collagen peptides and YKL-40 across the length of each binding site, which contributes to overall stability and binding affinity. The hydrogen bonding analysis for the collagen-YKL-40 systems was performed as described above for the polysaccharide ligands; pairs exhibiting greater than 10% occupancy over the simulation are reported individually insupplemental Table S6. The YKL-40 residues responsible for hydrogen bonding are not consistent across each collagen model (supplemental Table S6). In general, Glu70, Trp99, Asn100, Tyr141, Arg145, Ser179, Lys182, Thr184, Asp207, Arg213, Phe218, Asp232, and Arg263 in binding site A form hydrogen bonds with the peptides. Similarly at site B, Tyr22, Lys23, Asn87, Asn89, Lys91, Lys377, and Asp378 are typically involved in hydrogen bonding. The variation in hydrogen bonding pairs between YKL-40 and the collagen peptides is a natural extension of the varying amino acids along the repeating Gly-Xaa-Yaa sequence; there are many different potential donor and acceptor pairs in each case. Hydroxyproline residues play a crucial role both as donor and acceptor in most pairs, benefitting from the extra hydroxyl group relative to proline. Although all the collagen peptides maintain association with collagen-binding site A, the hydrogen bonding characteristics are slightly different for each, which will in turn lead to affinity differences. The relaxed helical pitch of the 1CAG peptide effectively disrupts hydrogen bonding, and affinity for the ligand is lost at binding site B. The 1BKV peptide model with 10/3 symmetry was also unable to remain associated with binding site B, suggesting that binding site B may be more sensitive to helical pitch and prefers 7/2 symmetrical helices.

Collagen-like Peptide Binding Affinity

The relative binding affinity of collagen-like peptides to YKL-40 was determined from umbrella sampling MD simulations. Here, we report the binding affinity of the 1Q7D collagen-like peptide, which is the integrin binding peptide with an overall 7/2 helical pitch (41, 42), at both sites A and B. We have also calculated binding affinity of native 1CAG at binding site A for comparison of binding affinities of two different collagen peptides having different residue substitutions and helical pitches. Unfortunately, in case of umbrella sampling for the native 1CAG peptide at site B, we were unable to obtain statistically reliable results, and thus, we will not discuss findings relative to the affinity of this model.

The umbrella sampling MD simulations of the 1Q7D collagen peptide at both sites A and B show that YKL-40 has similar affinity for 1Q7D at both sites; however, the native 1CAG collagen peptide appears to bind with a lower affinity than 1Q7D at binding site A (Fig. 8c). We note that the last umbrella sampling window in case 1Q7D at binding site A shows a sudden, sharp increase in the potential of mean force (PMF), which is an artifact of the use of native contacts as an umbrella sampling reaction coordinate. As the standard C termini of three strands of collagen helix are negatively charged, they are attracted to the nearby, highly positively charged surface of heparin-binding site. As a result, the final window of the PMF overestimates the work to remove the 1Q7D peptide from binding site A exclusively (Fig. 8). Removing this latter window from the calculation, the free energy of binding 1Q7D is −40.8 ± 4.7 kJ/mol in site A and −42.9 ± 5.0 kJ/mol in site B. The free energy of binding native 1CAG in site A is −22.0 ± 3.4 kJ/mol. The relatively low statistical uncertainty at each window along the potential of mean force suggests sampling of the system was sufficient, providing a meaningful estimate of binding affinity.

The potential of mean force determined from umbrella sampling MD simulations determines the amount of work required to pull the collagen ligand from the binding site. Because free energy is a state function, the difference between the beginning and end state is the binding affinity, regardless of the path taken, as reported above. The path can provide information as to barriers to unbinding; however, the collagen peptides are readily removed from the binding sites along a relatively smooth path. This suggests there is little conformational rearrangement required of YKL-40 in the release of the collagen ligand. The difference between affinity for 1Q7D and native 1CAG at binding site A is reflected in the total hydrogen bonding occupancy in those two cases (supplemental Table S6). Notably, the binding free energies of collagen to YKL-40 are approximately half that of the tighter binding polysaccharide ligands. This suggests that YKL-40 will bind both hyaluronan and chito-oligomers over collagen in the presence of all three. This does not rule out collagen as a physiological ligand but strongly supports hyaluronan as a preferred physiological ligand of YKL-40.

Conclusions

We constructed polysaccharide-bound YKL-40 models and collagen peptide-bound models to understand the molecular level interactions of the protein with potential physiological ligands. MD simulations, as well as free energy calculations, overwhelmingly suggest that polysaccharide ligands, in particular chito-oligomers and hyaluronan, are preferential physiological ligands of YKL-40. However, YKL-40 does appear to bind collagen peptides at two locations along the surface of the molecule. This demonstrates diversity of function of YKL-40 and may potentially be related to the promotion or inhibition of collagen fibril formation, because one could easily imagine that YKL-40 mediates interaction between the triple helix fibers, potentially disrupting the natural matrix. Further structural studies of YKL-40·collagen complexes are certainly warranted and would be invaluable in our understanding of YKL-40 protein-protein interactions.

The apparent difference in binding affinity of YKL-40 for the polysaccharide ligands and collagens is related to the ability of the smaller ligands to penetrate the primary binding cleft. These ligands are able to form longer-lived hydrogen bonds deeper in the hydrophobic interior of the protein. Additionally, electrostatic interactions play a key role in ligand recognition and affinity to YKL-40. Improper alignment of the large, charged side chains of heparan sulfate, heparin, and chondroitin sulfate with the residues lining the YKL-40 cleft prohibits these ligands from binding in the primary binding cleft. However, the smaller, negatively charged side chain of hyaluronan interacts favorably in the primary binding cleft and contributes significantly to the affinity of this molecule. Additionally, we confirmed the non-specific interaction of heparin with the putative heparin-binding domain suggested from previous structural studies. The charged side chains repeatedly and spontaneously interact with charged residues at this secondary surface-binding site.

Overall, our findings indicate that YKL-40 may interact with several ligands in vivo, including both polysaccharides and collagen. We suggest that hyaluronan is a preferential physiological ligand of YKL-40, which may explain the pervasive association of YKL-40 with the physical maladies in which hyaluronan has been associated (2, 5, 81, 82). These findings not only identify physiological ligands of YKL-40, they enable future efforts to rationally guide design of YKL-40 inhibitors, the design of which is invaluable in the control of inflammation-based disorders and possibly several types of cancer.

Author Contributions

C. M. P. designed and coordinated the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. A. A. K. performed the simulations, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The Center for Computational Sciences DLX cluster at University of Kentucky was used for data storage and simulation analysis.

This work was supported by Kentucky Science and Engineering Foundation Grant KSEF-148-502-13-307). Computational time for this research was provided by the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (83), which is supported by National Science Foundation Grant ACI-1053575 under Allocation MCB090159. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental text, Tables S1–S6, Figs. S1–S8, and Movies S1–S3.

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- PMF

- potential of mean force

- FEP

- free energy perturbation

- REMD

- replica exchange molecular dynamics

- WCA

- Weeks-Chandler-Anderson

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation

- RMSF

- root mean square fluctuation

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank.

References

- 1. Faibish M., Francescone R., Bentley B., Yan W., and Shao R. (2011) A YKL-40-neutralizing antibody blocks tumor angiogenesis and progression: a potential therapeutic agent in cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 742–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Francescone R. A., Scully S., Faibish M., Taylor S. L., Oh D., Moral L., Yan W., Bentley B., and Shao R. (2011) Role of YKL-40 in the angiogenesis, radioresistance, and progression of glioblastoma. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 15332–15343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ku B. M., Lee Y. K., Ryu J., Jeong J. Y., Choi J., Eun K. M., Shin H. Y., Kim D. G., Hwang E. M., Yoo J. C., Park J.-Y., Roh G. S., Kim H. J., Cho G. J., Choi W. S., et al. (2011) CHI3L1 (YKL-40) is expressed in human gliomas and regulates the invasion, growth and survival of glioma cells. Int. J. Cancer 128, 1316–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park J.-A., Drazen J. M., and Tschumperlin D. J. (2010) The chitinase-like protein YKL-40 is secreted by airway epithelial cells at base line and in response to compressive mechanical stress. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29817–29825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johansen J. S. (2006) Studies on serum YKL-40 as a biomarker in diseases with inflammation, tissue remodelling, fibroses and cancer. Danish Med. Bull. 53, 172–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mizoguchi E. (2006) Chitinase 3-like-1 exacerbates intestinal inflammation by enhancing bacterial adhesion and invasion in colonic epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 130, 398–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nyirkos P., and Golds E. E. (1990) Human synovial-cells secrete a 39-kDa protein similar to a bovine mammary protein expressed during the nonlactating period. Biochem. J. 269, 265–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Renkema G. H., Boot R. G., Strijland A., Donker-Koopman W. E., van den Berg M., Muijsers A. O., and Aerts J. M. (1997) Synthesis, sorting, and processing into distinct isoforms of human macrophage chitotriosidase. Eur. J. Biochem. 244, 279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bigg H. F., Wait R., Rowan A. D., and Cawston T. E. (2006) The mammalian chitinase-like lectin, YKL-40, binds specifically to type I collagen and modulates the rate of type I collagen fibril formation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21082–21095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Houston D. R., Recklies A. D., Krupa J. C., and van Aalten D. M. (2003) Structure and ligand-induced conformational change of the 39-kDa glycoprotein from human articular chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30206–30212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fusetti F., Pijning T., Kalk K. H., Bos E., and Dijkstra B. W. (2003) Crystal structure and carbohydrate-binding properties of the human cartilage glycoprotein-39. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37753–37760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P. M., and Henrissat B. (2014) The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lis H., and Sharon N. (1998) Lectins: Carbohydrate-specific proteins that mediate cellular recognition. Chem. Rev. 98, 637–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weis W. I., and Drickamer K. (1996) Structural basis of lectin-carbohydrate recognition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 441–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siaens R., Eijsink V. G., Dierckx R., and Slegers G. (2004) 123I-Labeled chitinase as specific radioligand for in vivo detection of fungal infections in mice. J. Nucl. Med. 45, 1209–1216 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Drickamer K., and Taylor M. E. (1993) Biology of animal lectins. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 9, 237–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lal A., Lash A. E., Altschul S. F., Velculescu V., Zhang L., McLendon R. E., Marra M. A., Prange C., Morin P. J., Polyak K., Papadopoulos N., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W., Strausberg R. L., and Riggins G. J. (1999) A public database for gene expression in human cancers. Cancer Res. 59, 5403–5407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lau S. H., Sham J. S., Xie D., Tzang C. H., Tang D., Ma N., Hu L., Wang Y., Wen J. M., Xiao G., Zhang W. M., Lau G. K., Yang M., and Guan X. Y. (2006) Clusterin plays an important role in hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Oncogene 25, 1242–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zaheer-ul-Haq, Dalal P., Aronson N. N. Jr., and Madura J. D. (2007) Family 18 chitolectins: comparison of MGP40 and HUMGP39. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 359, 221–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mohanty A. K., Singh G., Paramasivam M., Saravanan K., Jabeen T., Sharma S., Yadav S., Kaur P., Kumar P., Srinivasan A., and Singh T. P. (2003) Crystal structure of a novel regulatory 40-kDa mammary gland protein (MGP-40) secreted during involution. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14451–14460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Ceuninck F., Pastoureau P., Bouet F., Bonnet J., and Vanhoutte P. M. (1998) Purification of guinea pig YKL40 and modulation of its secretion by cultured articular chondrocytes. J. Cell. Biochem. 69, 414–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Connor J. R., Dodds R. A., Emery J. G., Kirkpatrick R. B., Rosenberg M., and Gowen M. (2000) Human cartilage glycoprotein 39 (HC gp-39) mRNA expression in adult and fetal chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteocytes by in-situ hybridization. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 8, 87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hakala B. E., White C., and Recklies A. D. (1993) Human cartilage gp-39, a major secretory product of articular chondrocytes and synovial-cells, is a mammalian member of a chitinase protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 25803–25810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harvey S., Weisman M., O'Dell J., Scott T., Krusemeier M., Visor J., and Swindlehurst C. (1998) Chondrex: new marker of joint disease. Clin. Chem. 44, 509–516 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johansen J. S., Hvolris J., Hansen M., Backer V., Lorenzen I., and Price P. A. (1996) Serum YKL-40 levels in health children and adults: comparison with serum and synovial fluid levels of YKL-40 in patients with osteoarthritis or trauma of the knee joint. Br. J. Rheumatol. 35, 553–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johansen J. S., Jensen H. S., and Price P. A. (1993) A new biochemical marker for joint injury: analysis of YKL-40 in serum and synovial-fluid. Br. J. Rheumatol. 32, 949–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iozzo R. V. (1998) Matrix proteoglycans: from molecular design to cellular function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 609–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rabenstein D. L. (2002) Heparin and heparan sulfate: structure and function. Nat. Prod. Rep. 19, 312–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meyer M. F., and Kreil G. (1996) Cells expressing the DG42 gene from early Xenopus embryos synthesize hyaluronan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 4543–4547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Semino C. E., Specht C. A., Raimondi A., and Robbins P. W. (1996) Homologs of the Xenopus developmental gene DG42 are present in zebrafish and mouse and are involved in the synthesis of Nod-like chitin oligosaccharides during early embryogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 4548–4553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Varki A. (1993) Biological roles of oligosaccharides: all of the theories are correct. Glycobiology 3, 97–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fraser J. R., Laurent T. C., and Laurent U. B. (1997) Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J. Intern. Med. 242, 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Malavaki C., Mizumoto S., Karamanos N., and Sugahara K. (2008) Recent advances in the structural study of functional chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate in health and disease. Connect. Tissue Res. 49, 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brodsky B., and Persikov A. V. (2005) Molecular structure of the collagen triple helix. Adv. Protein Chem. 70, 301–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kramer R. Z., Bella J., Mayville P., Brodsky B., and Berman H. M. (1999) Sequence dependent conformational variations of collagen triple-helical structure. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 454–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Okuyama K., Miyama K., Mizuno K., and Bächinger H. P. (2012) Crystal structure of (Gly-Pro-Hyp)9: implications for the collagen molecular model. Biopolymers 97, 607–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rich A., and Crick F. H. (1961) The molecular structure of collagen. J. Mol. Biol. 3, 483–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Okuyama K., Xu X., Iguchi M., and Noguchi K. (2006) Revision of collagen molecular structure. Biopolymers 84, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shoulders M. D., and Raines R. T. (2009) Collagen structure and stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 929–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bella J., Eaton M., Brodsky B., and Berman H. M. (1994) Crystal-structure and molecular-structure of a collagen-like peptide at 1.9-angstrom resolution. Science 266, 75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Emsley J., Knight C. G., Farndale R. W., and Barnes M. J. (2004) Structure of the integrin α2β1-binding collagen peptide. J. Mol. Biol. 335, 1019–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Emsley J., Knight C. G., Farndale R. W., Barnes M. J., and Liddington R. C. (2000) Structural basis of collagen recognition by integrin α2β1. Cell 101, 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brooks B. R., Brooks C. L. 3rd, Mackerell A. D. Jr., Nilsson L., Petrella R. J., Roux B., Won Y., Archontis G., Bartels C., Boresch S., Caflisch A., Caves L., Cui Q., Dinner A. R., Feig M., et al. (2009) CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 1545–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guvench O., Greene S. N., Kamath G., Brady J. W., Venable R. M., Pastor R. W., and Mackerell A. D. Jr. (2008) Additive empirical force field for hexopyranose monosaccharides. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 2543–2564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Guvench O., Hatcher E. R., Venable R. M., Pastor R. W., and Mackerell A. D. (2009) CHARMM additive all-atom force field for glycosidic linkages between hexopyranoses. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 2353–2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guvench O., Mallajosyula S. S., Raman E. P., Hatcher E., Vanommeslaeghe K., Foster T. J., Jamison F. W. 2nd, and Mackerell A. D. Jr. (2011) CHARMM additive all-atom force field for carbohydrate derivatives and its utility in polysaccharide and carbohydrate-protein modeling. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 3162–3180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mayne C. G., Saam J., Schulten K., Tajkhorshid E., and Gumbart J. C. (2013) Rapid parameterization of small molecules using the force field toolkit. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 2757–2770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Humphrey W., Dalke A., and Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Duhovny D., Nussinov R., and Wolfson H. J. (2002) Efficient unbound docking of rigid molecules. In Gusfield, et al., Ed. Proceedings of the 2'nd Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics(WABI) Rome, Italy Lect. Notes Comput. Sc. 2452, 185–200, Springer Verlag [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schneidman-Duhovny D., Inbar Y., Nussinov R., and Wolfson H. J. (2005) PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W363–W367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., and Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jiang W., Hodoscek M., and Roux B. (2009) Computation of absolute hydration and binding free energy with free energy perturbation distributed replica-exchange molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 2583–2588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jiang W., and Roux B. (2010) Free energy perturbation hamiltonian replica-exchange molecular dynamics (FEP/H-REMD) for absolute ligand binding free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6, 2559–2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Payne C. M., Jiang W., Shirts M. R., Himmel M. E., Crowley M. F., and Beckham G. T. (2013) Glycoside hydrolase processivity Is directly related to oligosaccharide binding free energy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18831–18839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Beckham G. T., Matthews J. F., Peters B., Bomble Y. J., Himmel M. E., and Crowley M. F. (2011) Molecular-level origins of biomass recalcitrance: decrystallization free energies for four common cellulose polymorphs. J. Phys. Chem. B. 115, 4118–4127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Payne C. M., Himmel M. E., Crowley M. F., and Beckham G. T. (2011) Decrystallization of oligosaccharides from the cellulose I β surface with molecular simulation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 1546–1550 [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sheinerman F. B., and Brooks C. L. 3rd (1998) Calculations on folding of segment B1 of streptococcal protein G. J. Mol. Biol. 278, 439–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Deleted in proof

- 59. Mulloy B., Forster M. J., Jones C., and Davies D. B. (1993) N.m.r., and molecular-modelling studies of the solution conformation of heparin. Biochem. J. 293, 849–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Payne C. M., Knott B. C., Mayes H. B., Hansson H., Himmel M. E., Sandgren M., Ståhlberg J., and Beckham G. T. (2015) Fungal cellulases. Chem. Rev. 115, 1308–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Angyal S. J. (1969) The composition and conformation of sugars in solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 8, 157–166 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Davies G., and Henrissat B. (1995) Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure 3, 853–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Davies G. J., Planas A., and Rovira C. (2012) Conformational analyses of the reaction coordinate of glycosidases. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 308–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sinnott M. L. (1990) Catalytic mechanisms of enzymatic glycosyl transfer. Chem. Rev. 90, 1171–1202 [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vocadlo D. J., and Davies G. J. (2008) Mechanistic insights into glycosidase chemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12, 539–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hamre A. G., Jana S., Reppert N. K., Payne C. M., and Sørlie M. (2015) Processivity, substrate positioning, and binding: The role of polar residues in a family 18 glycoside hydrolase. Biochemistry 54, 7292–7306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cardin A. D., and Weintraub H. J. (1989) Molecular modeling of protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Arteriosclerosis 9, 21–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hamre A. G., Jana S., Holen M. M., Mathiesen G., Väljamäe P., Payne C. M., and Sørlie M. (2015) Thermodynamic relationships with processivity in Serratia marcescens family 18 chitinases. J. Phys. Chem. B. 119, 9601–9613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Asensio J. L., Ardá A., Cañada F. J., and Jiménez-Barbero J. (2013) Carbohydrate-aromatic interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 946–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Josefsson A., Adamo H., Hammarsten P., Granfors T., Stattin P., Egevad L., Laurent A. E., Wikström P., and Bergh A. (2011) Prostate cancer increases hyaluronan in surrounding nonmalignant stroma, and this response is associated with tumor growth and an unfavorable outcome. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 1961–1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Aruffo A., Stamenkovic I., Melnick M., Underhill C. B., and Seed B. (1990) CD44 is the principal cell surface receptor for hyaluronate. Cell 61, 1303–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Liu L.-K., and Finzel B. (2014) High-resolution crystal structures of alternate forms of the human CD44 hyaluronan-binding domain reveal a site for protein interaction. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 70, 1155–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., and Lipman D. J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Toole B. P. (1990) Hyaluronan and its binding proteins, the hyaladherins. Curr. Opin Cell Biol. 2, 839–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]