Abstract

Access to electric light might have shifted the ancestral timing and duration of human sleep. To test this hypothesis, we studied two communities of the historically hunter-gatherer indigenous Toba/Qom in the Argentinean Chaco. These communities share the same ethnic and sociocultural background, but one has free access to electricity while the other relies exclusively on natural light. We fitted participants in each community with wrist activity data loggers to assess their sleep-wake cycles during one week in the summer and one week in the winter. During the summer, participants with access to electricity had a tendency to a shorter daily sleep bout (43 ± 21 min) than those living under natural light conditions. This difference was due to a later daily bedtime and sleep onset in the community with electricity, but a similar sleep offset and rise time in both communities. In the winter, participants without access to electricity slept longer (56 ± 17 min) than those with access to electricity, and this was also related to earlier bedtimes and sleep onsets than participants in the community with electricity. In both communities, daily sleep duration was longer during the winter than during the summer. Our field study supports the notion that access to inexpensive sources of artificial light and the ability to create artificially lit environments must have been key factors in reducing sleep in industrialized human societies.

Keywords: sleep timing, South American indigenous communities, natural light-dark cycle, artificial light-dark cycle

The daily timing and amount of sleep has changed throughout human history, particularly as our species transitioned from nomadic hunter-gatherer groups to agricultural societies and, more recently, to industrialized ones (Ekirch, 2006). Whereas historical records depict that the onset of sleep at night coincided with the inexorable arrival of dusk, modern society has crafted a sleep schedule that is heavily influenced by protected, artificially lit environments. Whether natural or artificial, light is among the most important environmental factors regulating sleep. In humans, light induces alertness and entrains a master circadian clock that regulates the timing of sleep (de la Iglesia and Lee, 2014). Thus, the ability to control our own exposure to light through artificial means likely altered when we sleep and for how long. Although this is clearly supported by human studies in sleep laboratories, testing this hypothesis in the field has been complicated by the lack of appropriate human populations. Although it is not difficult to find communities without access to electric light, it is difficult to find communities of the same ethnic and sociocultural background with free access to electricity that can be studied simultaneously.

The Toba/Qom are one of the 3 main indigenous groups in the Argentinean Gran Chaco region (provinces of Formosa and Chaco) of northeastern Argentina (Braunstein and Miller, 1999; Valeggia et al., 2010). The Western Toba represent a subgroup living in the western region of the province of Formosa (23°47′ S, 61°48′ W). Traditionally hunter-gatherers, they now exhibit a spectrum of subsistence and lifestyle patterns. Some live in neighborhoods on the outskirts of small towns, whereas others live in relatively isolated villages of 20 to 600 people and still rely on hunting and gathering for at least part of their subsistence (Lanza et al., 2009; Valeggia et al., 2010). We studied 2 Western Toba communities within this region. The first one has 24-h access to electricity (Electricity); the second one lives ∼50 km away and has no access to electricity (NO-electricity). This latter community relies on daylight for their daily activities. To examine the hypothesis that access to electric light affects the timing and amount of sleep, we fitted participants in each community with wrist data loggers that measure motor activity and light exposure with high-frequency sampling, allowing quantification of sleep duration and timing.

Materials and Methods

Study Communities

We studied participants in 2 Toba/Qom communities in the province of Formosa. The first community is located in the outskirts of the small town of Ingeniero Juárez (23°47′ S, 61°48′ W), and all the participants from this community have access to electric light throughout the 24-h day. The second one lives in a rural area 50 km north of the first community and has no access to electric light; although some children of school age could be exposed to electric light at the school, this never happened outside of the natural daylight hours. People in both communities share the same ethnohistorical past. In fact, people in the Electricity community originated from a few families who migrated from the NO-electricity community and its surroundings in the early 1990s; people are related by blood both within and between communities. In a spectrum of market integration, people in the Electricity community are more settled and participate less in foraging activities than people in the NO-electricity community, who rely more on hunting, gathering, and fishing for part of their subsistence, particularly during the summer when foraged items are more abundant. Importantly, the type of housing, daily chores participants are involved in, and social behavior are similar for both communities. Most adults in both communities are unemployed and subsist on governmental subsidies and/or very short-term temporary jobs; only one of the participants in the Electricity community had a job as a nurse requiring a regular schedule, which did not involve waking up before sunrise.

These communities experience a seasonal change in daylight of almost 3 h per day between the winter and summer solstices (Erkert et al., 2012). The first study took place close to the summer solstice, between November 24 and December 2, 2012. The second one was close to the winter solstice, between August 7 and August 21, 2013. Participants included adults and adolescents (ages 14-49 years) of both sexes. The mean ages (± SEM) for the summer and winter studies were, respectively, 17.3 ± 2.4 and 27.4 ± 3.1 for the NO-electricity groups and 28.8 ± 5.8 and 29.1 ± 2.7 for the Electricity groups. A 2-way analysis of variance on the ages revealed no statistically significant effects of season, electricity, or the interaction, although there was a trend for the NO-electricity group to be younger (F1,27 = 3.44, p = 0.07 for electricity; F1,27 = 2.1, p = 0.16 for season; F1,27 = 1.9, p = 0.18 for the interaction). All groups had 50% of female participants, except for the winter Electricity group, which included 73% of female participants. Due to the small sample size for each category, we did not analyze the statistical effects of age or sex. Sleep was sampled in both seasons for only 2 participants in the NO-electricity community and 1 in the Electricity community, preventing us from carrying out repeated-measures statistical tests. The experimental protocol was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. Oral consent was obtained after verbally explaining, in Spanish, the procedures to the participants. Parental oral consent was obtained for participants younger than 18 years. A printed copy of the detailed protocols and the rationale for the research study, in layperson language, was left with each family group, as most adolescents and adults in each family group could read Spanish.

Actigraphy and Sleep Data

For the summer study, we fitted 6 participants in each of the 2 communities with wrist data loggers (Actiwatch-L; Mini Mitter, Bend, OR) during 6 to 8 days. For the winter study, we fitted 11 and 8 participants in the Electricity and NO-electricity communities, respectively, during 4 to 13 days. Data loggers were programmed to record activity and light exposure at 1-min intervals. Locomotor activity (total counts per minute) or light exposure (light intensity at the end of the 1-min bin) data were then averaged for intervals of 20 min. These 20-min averages of activity and light exposure throughout the days were used to construct an individual waveform—namely, the 24-h profile of activity or light exposure for each individual that is based on all the sampled days (Suppl. Fig. S1). A mean waveform was then constructed by averaging the corresponding 20-min bins of all the individuals within each community.

Sleep Parameters

Participants kept an individual sleep diary in which they recorded bedtime, rise time, whether they took any naps, and whether they traveled outside their home community. All participants were literate enough to fill out the diaries in Spanish. Researchers lived on a site between the 2 study communities and visited each one daily to confirm that participants were properly recording diary entries. Bedtimes recorded in the sleep diaries were manually input into the Sleep Analysis package of the Mini Mitter Software (version 3.4). We then used the software to estimate the following parameters for each night: sleep onset, sleep latency (time between bedtime and sleep onset), sleep offset, sleep duration, rise time (reported wakeup time in the sleep diary), and fragmentation index (an index of restlessness during sleep based on interrupted immobility bouts within the nocturnal sleep episode).

Statistics

Twenty-minute mean waveforms for activity and light exposure were analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors electricity (NO-electricity vs. Electricity) and time. Homogeneity of variance was tested with the Bartlett test. When variances were not homogeneous, data were converted to log (x) or log (x + 1), where x is the value of activity or light intensity, respectively. Sleep parameters were analyzed with a 2-way ANOVA with factors electricity and season (Table 1); when the respective effect was statistically significant, comparisons were done with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 1. Sleep Parameters and Statistical Analysis.

| Sleep Parameters (Mean ± SEM) | Two-Way ANOVA Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| NO-Electricity, Summer (Winter) | Electricity, Summer (Winter) | Electricity (F1,27; p Value) | Season (F1,27; p Value) | Interaction (F1,27; p Value) | |

| Bedtime | 21:51 ± 0:14 (21:46 ± 0:12) | 22:59 ± 0:19 (22:45 ± 0:15) | (16; 0.0005) | (0.34; 0.56) | (0.08; 0.78) |

| Sleep onset | 22:14 ± 0:12 (22:12 ± 0:09) | 23:17 ± 0:14 (23:06 ± 0:18) | (13; 0.0011) | (0.16; 0.69) | (0.08; 0.78) |

| Sleep latency | 0.92 ± 0.23 (1.09 ± 0.25) | 0.60 ± 0.40 (1.10 ± 0.32) | (0.22; 0.64) | (1.0; 0.32) | (0.25; 0.62) |

| Sleep duration | 6.98 ± 0.18 (8.47± 0.23) | 6.27 ± 0.28 (7.53 ± 0.18) | (14; 0.0010) | (38; < 0.0001) | (0.26; 0.61) |

| Sleep offset | 06:23 ± 0:11 (07:29 ± 0:10) | 06:40 ± 0:22 (07:31 ± 0:14) | (0.43; 0.52) | (15; 0.0006) | (0.25; 0.62) |

| Rise time | 06:51 ± 0:12 (07:44 ± 0:13) | 06:53 ± 0:22 (07:55 ± 0:15) | (0.16; 0.69) | (12; 0.0017) | (0.085; 0.77) |

| Fragmentation index | 31.95 ± 2.48 (21.24 ± 3.69) | 28.25 ± 4.79 (25.63 ± 1.68) | (0.012; 0.91) | (4.5; 0.0438) | (1.6; 0.21) |

Bedtime, sleep onset, sleep offset, and rise time are indicated in clock time. Sleep duration and sleep latency are indicated in hours. ANOVA = analysis of variance. Boldface indicates statistically significant effects (P ≤ 0.05).

Results

Access to Electricity Is Associated with Changes in Daily Activity

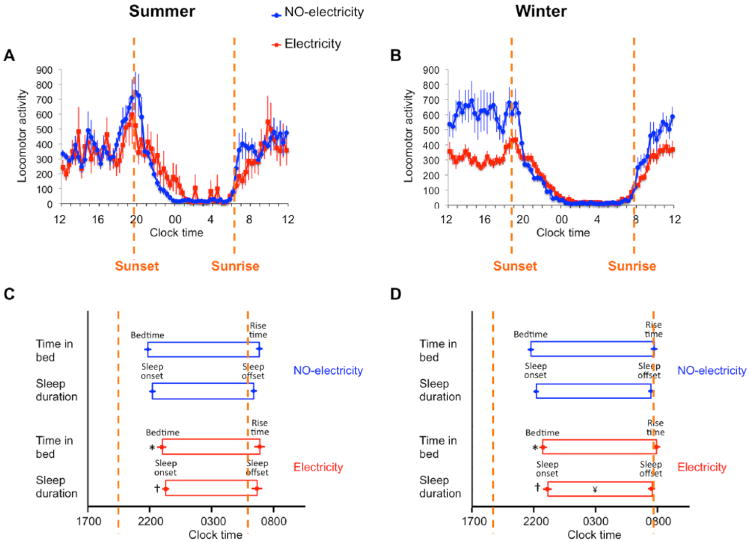

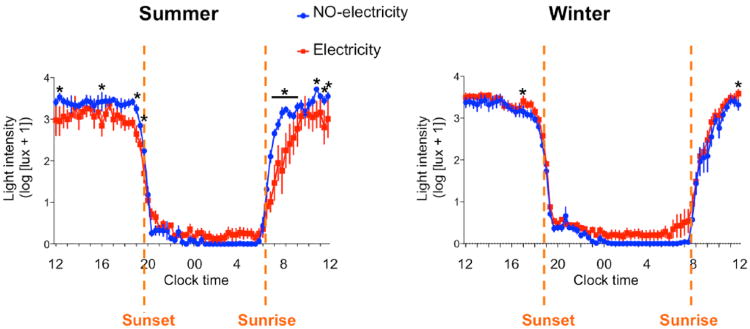

For the study close to the summer solstice, the temporal distribution of daily activity differed in the 2 communities (Fig. 1A). The mean activity waveforms showed less variability in locomotor activity levels in the NO-electricity than in the Electricity community (SD = 138 vs. 209; Bartlett test, F = 50, p < 0.0001). Inspection of the individual activity profiles (Suppl. Fig. S1A) suggests that the higher variance in the Electricity group results from higher intra- and inter-individual variability. Reduced interindividual variability in the NO-electricity group is consistent with the synchronous and more abrupt decrease and increase of activity at the times of sunset and sunrise, respectively (Fig. 1A). A 2-way ANOVA on the average waveforms of activity data from each group presented in Figure 1A yielded statistically significant effects of time (F71,710 = 32, p < 0.0001) and of the interaction between time and group (F71,710 = 1.9, p < 0.0001) but not of group (F1,10 = 0.6, p = 0.45). The pattern of activity between the two communities was similar to the patterns of light exposure between the 2 groups (Fig. 2). The variance in light exposure was also higher in the Electricity than in the NO-electricity group (SD = 1788 vs. 1225; Bartlett test, F = 60.10, p < 0.0001), and the 2-way ANOVA showed statistically significant effects of time (F71,710 = 163, p < 0.0001) and interaction between time and group (F71,710 = 3.1, p < 0.0001) but not of group (F1,10 = 2.0, p = 0.18). When we focused our comparison of light exposure between the 2 groups on the evening hours, we found that the NO-electricity group was exposed to light of higher intensity (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Rest-activity profiles and sleep parameters differ between Toba communities living without access to electricity (NO-electricity) and with free access to electricity (Electricity). (A, B) Mean waveforms for the 2 communities during the summer (A) and winter (B). (C, D) Sleep parameters derived from sleep diaries combined with wrist actimeters for each community during the summer (C) and winter (D). *, †, and ¥: significantly different from NO-electricity (p = 0.05) for bedtime, sleep onset, and sleep duration, respectively; post hoc comparisons, Fisher's least significant difference test. Summer, n = 6 for both communities; winter, n = 8 and 11 for NO-electricity and Electricity, respectively. Dashed lines mark sunset and sunrise times. Data represent mean ± SEM.

Figure 2.

Light-exposure profiles in Toba communities living without access to electricity (NO-electricity) and with free access to electricity (Electricity). Mean waveforms for the 2 communities during the summer and winter are shown. *Significant difference between groups (p < 0.05), post hoc comparisons, Fisher's least significant difference test. Data represent mean ± SEM.

To assess whether there were seasonal effects on the sleep patterns in the 2 communities, we conducted a second study during the winter solstice. The temporal distribution of daily activity also differed between the 2 communities during the winter (Fig. 1B). The variance for the Electricity group was lower than in the NO-electricity group (SD = 118 vs. 186; Bartlett test, F = 114, p < 0.0001). A 2-way ANOVA revealed statistically significant effects of time (F71,1207 = 98, p < 0.0001) and the interaction (F71,1207 = 2.3, p < 0.0001) but not of group (F1,17 = 0.5, p = 0.46). Inspection of the average waveforms also suggests a more synchronous wake offset and onset in the NO-electricity community, which was more closely associated with sunset and sunrise, respectively. The NO-electricity group showed higher activity levels as reflected by a larger mean area under the curve than did the Electricity group (2-tailed Student t test, t17 = 3.1, p = 0.007). The analysis of light exposure data (Fig. 2) showed that the variance was lower in the Electricity group than in the NO-electricity group (SD = 1176 vs. 1363; Bartlett test, F = 12, p = 0.0004), and a 2-way ANOVA showed statistically significant effects of time (F71,1207 = 331, p < 0.0001) and group (F1,17 = 4.7, p = 0.04, with higher intensity light exposure for the Electricity group) and no effect of the interaction (F71,1207 = 0.5, p = 0.9). In contrast to the summer results, comparisons of light exposure during the winter evening hours revealed that individuals in the Electricity group were exposed to higher light intensities (Fig. 2).

Access to Electricity Is Associated with Shorter Sleep Duration

The activity profiles for each community (Fig. 1A,B) suggest that access to electric light is associated with shorter sleep duration regardless of season (Table 1). During the summer, sleep duration in the NO-electricity community was 43 ± 21 min longer than in the Electricity community (Fig. 1C). Although this difference did not reach statistical significance in the Bonferroni post hoc comparison, it was statistically significant when evaluated with a 1-tailed Student t test (t10 = 2.1, p = 0.03). During the winter, the NO-electricity group slept on average 56 ± 17 min more than did the Electricity community (Fig. 1D); the difference was statistically significant. In both seasons, the longer duration of sleep in the NO-electricity community was due to a significantly earlier bedtime (summer: 68 ± 24 min; winter: 59 ± 20 min) and sleep onset (summer: 63 ± 25 min; winter: 54 ± 20 min) than in the Electricity community; however, both groups experienced a similar sleep offset and rise time within each season (Table 1; Fig. 1C,D; see figure legends for post hoc comparisons). Interestingly, the variance for sleep onset was greater for the Electricity group than the NO-electricity group in the winter (F10,7 = 5.5, p = 0.03) but not in the summer (F5,5 = 1.3, p = 0.8). The sleep onset variance within subjects (from day to day) did not differ for any of the seasons (2-tailed Student t test with Welch's correction for mean individual variances: t12.9 = 0.83, p = 0.4 for winter; t5.75 = 1.35, p = 0.2 for summer).

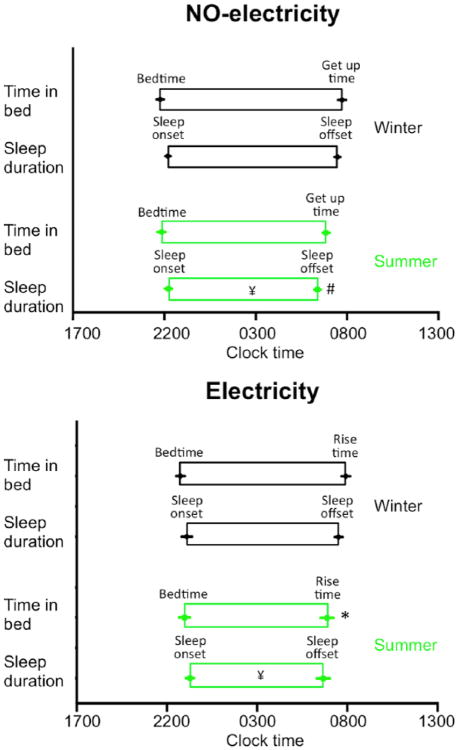

Sleep duration, sleep offset, rise time, and fragmentation index were also related to the season (Table 1). Individuals in both communities had shorter sleep durations during the summer than during the winter (Fig. 3). These differences were associated with a delay of 62 ± 22 min in the winter rise time (compared to summer rise time) for the Electricity community and a delay of 66 ± 22 min in the winter sleep offset (compared to summer sleep offset) for the NO-electricity community (Fig. 3). Rise time in the NO-electricity community showed a trend to occur earlier during the summer (not statistically significant in the Bonferroni comparison but significant with a 1-tailed Student t test, t12 = 2.8, p = 0.007). Sleep offset in the Electricity community showed a trend to occur earlier during the summer (not statistically significant in the Bonferroni comparison but significant with a 1-tailed Student t test, t15 = 2.06, p = 0.029). Thus, in both communities, longer sleep duration during the winter was associated with later sleep offsets and rise times, rather than with earlier bedtimes and sleep onsets. Finally, there was a trend for sleep to be more fragmented in the summer than in the winter for the NO-electricity community (not significant in the Bonferroni comparison but significant with a 1-tailed Student t test, t12 = 2.23, p = 0.023).

Figure 3.

Sleep parameters differ between winter and summer in Toba/Qom communities with and without access to electricity. Symbols as in Fig. 1C, D but significant differences are compared to the same community during the winter. Data represent mean ± SEM.

Discussion

We found that access to electricity in traditionally hunter-gatherer Toba/Qom communities is associated with later bedtimes and sleep onsets but not with later sleep-offset or rise times, leading to a shorter daily sleep duration than in individuals without access to electricity. This difference in sleep timing between the 2 communities also differed with season, with the community who had access to electricity sleeping approximately 40 min less in summer and an hour less in winter than the community without electricity. Examination of light levels in the 2 groups revealed that individuals in the community with access to electricity were exposed to brighter light intensities during the winter evenings, suggesting that their later sleep onset and shorter sleep duration are the result of their access to electric light. Similarly, a recent report of modern humans living in Stone Age conditions for 2 months found that the participants extended their time in bed and duration of sleep by approximately 90 min, with the majority of the extension achieved by earlier bedtimes (Piosczyk et al., 2014).

Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that access to electricity has allowed humans to extend the evening light hours, thereby delaying the time of sleep onset and reducing daily sleep duration (Czeisler, 2013). Most previous studies assessing the direct effects of artificial light on human sleep have been limited to laboratory experiments, in which the light can be controlled and manipulated as an independent variable. Light can directly affect human sleep through 2 mechanisms. First, light has direct effects on our ability to stay awake and active. This is, in part, by enabling us to stay alert and engage in activities that are not possible in the dark (Rahman et al., 2014) but also by directly inhibiting physiological systems that facilitate sleep, such as the nocturnal onset in the release of the hormone melatonin (Gooley et al., 2011; Wehr, 1999). Second, light can directly reset the phase of the circadian pacemaker responsible for the timing of sleep, which is remarkably sensitive to environmental light (Boivin et al., 1996; Czeisler et al., 1989; Zeitzer et al., 2000).

Field studies, in which the presence or absence of electric light is simultaneously studied in similar populations, are scarce. Indeed, there has been to date only one such report in which actimetry was used. Peixoto and collaborators (2009) studied adolescents with or without electricity in their home but attending the same school. Access to electricity at home was associated with a later sleep onset but not necessarily with shorter sleep duration. This result could be in part confounded by the fact that some of the students in the households without electricity went to artificially lit classes in the evening. Indeed, access to electricity was associated with shorter sleep times in adolescents who went to school in the morning but not in those who went to school in the afternoon. Importantly, adolescents in our study attended school in the morning, and school times were always during daylight hours; thus, students in neither community were exposed to electric light at school outside of natural daylight times. A recent study using actimetry in adults in a Haitian community without access to electricity suggested that, whereas the time in bed was longer than in more industrialized U.S. communities, sleep duration was not (Knutson, 2014). Wright and colleagues (2013) studied the sleep-wake cycle using actimetry and the phase of the circadian clock—assessed through melatonin release—in participants under typical conditions with access to artificial light and again in the same participants during a week-long camping trip under natural light conditions. This intervention study found that access to artificial lighting (and its corresponding enclosed environment) delayed both sleep timing and the phase of the circadian clock compared to the same variables measured under natural light-dark conditions. In contrast to our results, the authors did not find an effect on sleep duration in that short-term intervention.

The length of the natural night (from sunset to sunrise) during summer and winter in our study was 10.5 vs. 12.9 h, respectively. The delay in sleep onset and shorter sleep duration in the community with electricity were present during both seasons; however, sleep duration in the 2 communities differed less during the summer than during the winter (43 vs. 56 min, respectively). This result and the fact that individuals living under natural light had less exposure to light during the winter evening hours suggest that during the winter, artificial light may interfere more with the natural sleep pattern than during the summer (Bekinschtein et al., 2004).

Laboratory studies assessing the effect of long vs. short nights on sleep timing, duration, and quality determined that long nights are associated with more fragmented sleep and with a nocturnal sleep episode split into 2 by an interval of quiet wakefulness (reviewed in Wehr, 1999). In fact, these laboratory studies, as well as field studies using sleep diaries (Worthman and Brown, 2007; Worthman, 2009), have suggested that the consolidated sleep episode, which characterizes humans in modern societies, may be a consequence of a protected, artificially lit environment, where shielding from sleep disruptors and naturally long nights makes a consolidated bout of sleep possible. This is supported by historical records that portray a typical night as one that contains bouts of waking (Ekirch, 2006). Our results do not show evidence of fragmented sleep or a bout of quiet wakefulness in either community during the winter. In fact, in the NO-electricity community, the fragmentation index showed a trend to be higher in the summer than in the winter, which could be due to the high temperatures during the summer nights, when the temperature minimum can reach 30°C. Alternatively, this increased fragmentation may reflect the fact that the summer sample was taken around full moon nights, when individuals in the NO-electricity community reported being more active. Moon phases have been shown to be associated with specific changes in sleep changes (Cajochen et al., 2013); this association could potentially be stronger in the NO-electricity community. During the winter, at the subtropical latitude of our study site, the night (in the absence of civil twilight) is never longer than 12.3 h; the absence of sleep fragmentation or quiet wakefulness in this season could be due to the fact that 12.3 h of darkness may not be long enough to facilitate them. This is consistent with the findings of Piosczyk et al. (2014), who also did not observe sleep fragmentation under Stone Age living conditions in the summer, when the photoperiod was about 15 h. Future studies in indigenous populations during winter at higher latitudes will need to be carried out to explore whether this occurs under natural conditions (Bekinschtein et al., 2004). Wehr and collaborators reported that, compared to simulated short 8-h nights, simulated long 14-h nights led to longer episodes of nocturnal sleepiness and a longer and more fragmented nocturnal sleep bout (Wehr, 1999; Wehr et al., 1993). Interestingly, both Toba/Qom communities showed longer sleep times during the winter than during the summer, suggesting that a natural tendency to longer sleep as nights get longer is not fully overridden by access to electric light. This finding is consistent with seasonal variation in sleep parameters in European northern latitudes (Friborg et al., 2012; Hjorth et al., 2013) and with the hypothesis that the human circadian clock is influenced by solar time, particularly among people who live in small communities (Roenneberg et al., 2007).

During both seasons, the start of the rest phase was less synchronous in the Electricity community than in the NO-electricity community. The more synchronous sleep onset under natural light conditions likely reflects the fact that under these conditions, daily activities are tightly synchronized to the availability of sunlight and never take place in a self-selected artificially lit environment. This is clearly reflected by the fact that during the winter, the onset of sleep is more variable in the Electricity community, which is likely the result of each participant's choice of time to turn the lights off and go to sleep. This variability is likely also influenced by access to electronic devices such as radios, televisions, computers, and so on that may delay bedtime. Notably, the Argentinean government provides every high school student, including those in the communities we studied, with a laptop, which is obviously of limited use in the communities without electricity. Finally, analysis of the area under the activity curve showed that activity in the NO-electricity group was higher than in the Electricity group during the winter. This result suggests that the availability of electricity may have complex impacts on activity levels beyond the effect of extending wakefulness into the evening hours.

We recognize that a field study such as ours, in an ethnic group living in such a remote area, has inherent limitations. Specifically, we cannot manipulate light exposure as an independent variable, and therefore we can only establish relationships between the access to electric light and sleep patterns. Electricity was not only associated with a readily available source of artificial light but was also associated with a more comfortable and protected living environment. Furthermore, households in the electricity community typically have a television, which may not only change the exposure to light but also act as a stimulus to remain inside and awake during the evening. We are aware that the number of participants, particularly for the summer study, is relatively small. Nevertheless, a reduction of up to 1 h in the duration of sleep for the community with electricity points at a biologically relevant change in sleeping patterns. This statistically significant difference supports the prespecified hypothesis that electricity delays sleep onset and shortens sleep. Finally, although differences in daily habits between the 2 communities studied could contribute to our results, both communities live in very similar types of housing and have a similar social life, with large family groups that share a common piece of land with several houses.

Although daily sleep duration in industrialized groups is generally believed to have decreased relative to nonindustrialized groups, whether we have shortened our sleep and how much is still controversial (Bin et al., 2012; Matricciani et al., 2011). Nevertheless, several recent studies have found strong evidence for reduced sleep in modern societies (Carskadon, 2011; Klerman and Dijk, 2005; Matricciani et al., 2012). Daily sleep duration has lately received particular attention because of its clear link to both mental and physical health, safety, and performance (Czeisler, 2015); both excessively short or long sleep duration have been linked to disease and increased mortality (Cappuccio et al., 2008; Cappuccio et al., 2010; Knutsson, 2003). We found that sleep duration averaged 7 h in summer and nearly 8.5 h in winter in the community without access to electric light. While the winter sleep duration is longer than that typically reported from individuals in industrialized societies, the summer time duration is not (Ohayon et al., 2004; Reyner et al., 1995; Roffwarg et al., 1966).

Our field study in communities with and without electricity, but that are otherwise ethnically and socioculturally homogeneous, shows that access to electric light is associated with later bedtime and sleep onset timing, as well as reduced sleep duration. During the past century, the use of electric light has dramatically increased and its cost decreased (Ayres and Warr, 2004), which likely reduced our daily sleep time. Our study shows that the presence of electricity reduces sleep—a salient trait in human biology—in a traditionally hunter-gatherer group, a condition that represents a proxy for the human ancestral sleep-wake cycle. Importantly, the Toba/Qom community with access to electricity that we studied has remarkably less access to brightly artificially lit environments, appliances, eReaders, and sources of mass media than typical communities in industrialized societies (Chang et al., 2015); thus, the reduction of sleep we report likely underestimates the effect of electricity on human sleep.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Locomotor activity and light exposure recorded during the summer with wrist data loggers. (A) Raster plots of activity for Toba/Qom individuals (n=6) from the NO-Electricity and Electricity communities throughout the summer sampling days. Black bars on each 24-h horizontal line represent the activity levels. Successive days are stacked vertically. (B) Top, Two representative raster plots for activity and light exposure plotted as in (A). Bottom, a waveform for each parameter for one individual plotted by averaging the activity or light exposure throughout the sampling days for each 20-min bin.

Acknowledgments

In memory of Norberto Lanza, who is always present among us and his Toba/Qom friends. We are indebted to the Toba/ Qom community of Barrio Toba in Ingeniero Juárez, of Vaca Perdida, and of Isla García for their friendship and for allowing us to conduct this study. We also thank Natalia Benítez, Víctor Dávalos, Angélica Jaimez, Marcelo A. Rotundo, Alfonsina Salvarredy, and Mahboubeh Tavakoli for their help with data acquisition and analysis. We thank Dr. Ray Huey for comments on the manuscript. Fundación ECO, the Owl Monkey Project, and the CARE Project provided logistic support during and after field trips. This study was supported by Leakey Foundation grant 1266 and NSF IOS0909716 to HDI, NSF Career Award BCS-0952264 to CRV, NHLBI grant R01HL094654 to CAC, and ANPCyT y Universidad Nacional de Quilmes (Argentina) to DAG.

Footnotes

Conflict Of Interest Statement: The author(s) have no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Note: Supplementary material is available on the journal's website at http://jbr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Ayres RU, Warr B. Accounting for growth: the role of physical work. Struct Change Econ Dynamics. 2004;16(2):181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bekinschtein TA, Negro A, Goldín A, Fernández MP, Rosenbaum S, Golombek DA. Seasonality in a Mapuche native population. Biol Rhythm Res. 2004;35(1-2):145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bin YS, Marshall NS, Glozier N. Secular trends in adult sleep duration: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(3):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin DB, Duffy JF, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA. Dose-response relationships for resetting of human circadian clock by light. Nature. 1996;379(6565):540–542. doi: 10.1038/379540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein J, Miller E. Ethnohistorical introduction. In: Miller EK, editor. Peoples of the Gran Chaco. Bergin & Garvey; Westport, CT: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cajochen C, Altanay-Ekici S, Munch M, Frey S, Knoblauch V, Wirz-Justice A. Evidence that the lunar cycle influences human sleep. Curr Biol. 2013;23(15):1485–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, Currie A, Peile E, Stranges S, Miller MA. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep. 2008;31(5):619–626. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescents: The perfect storm. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(3):637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AM, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(4):1232–1237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418490112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler CA. Perspective: Casting light on sleep deficiency. Nature. 2013;497(7450):S13. doi: 10.1038/497S13a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler CA. Duration, timing and quality of sleep are each vital for health, performance and safety. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler CA, Kronauer RE, Allan JS, Duffy JF, Jewett ME, Brown EN, Ronda JM. Bright light induction of strong (type 0) resetting of the human circadian pacemaker. Science. 1989;244(4910):1328–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.2734611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Iglesia HO, Lee ML. A time to wake, a time to sleep. In: Aguilar-Roblero R, Fanjul-Moles ML, Díaz-Muñoz M, editors. Mechanisms of Circadian Systems in Animals and Their Clinical Relevance. Springer International; New York: 2014. p. 380. [Google Scholar]

- Ekirch AR. At Day's Close: Night in Times Past. Norton; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Erkert HG, Fernandez-Duque E, Rotundo M, Scheideler A. Seasonal variation of temporal niche in wild owl monkeys (Aotus azarai azarai) of the Argentinean Chaco: A matter of masking? Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(6):702–714. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.673190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friborg O, Bjorvatn B, Amponsah B, Pallesen S. Associations between seasonal variations in day length (photoperiod), sleep timing, sleep quality and mood: A comparison between Ghana (5 degrees) and Norway (69 degrees) J Sleep Res. 2012;21(2):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley JJ, Chamberlain K, Smith KA, Khalsa SB, Rajaratnam SM, Van Reen E, Zeitzer JM, Czeisler CA, Lockley SW. Exposure to room light before bedtime suppresses melatonin onset and shortens melatonin duration in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):E463–E472. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth MF, Chaput JP, Michaelsen K, Astrup A, Tetens I, Sjodin A. Seasonal variation in objectively measured physical activity, sedentary time, cardio-respiratory fitness and sleep duration among 8-11 year-old Danish children: A repeated-measures study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:808. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman EB, Dijk DJ. Interindividual variation in sleep duration and its association with sleep debt in young adults. Sleep. 2005;28(10):1253–1259. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL. Sleep duration, quality, and timing and their associations with age in a community without electricity in Haiti. Am J Hum Biol. 2014;26(1):80–86. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutsson A. Health disorders of shift workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53(2):103–108. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza N, Burke KM, Valeggia C. Fertility among the Toba, an Argentine indigenous population in transition. Soc Biol Hum Aff. 2009;73:26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Matricciani L, Olds T, Petkov J. In search of lost sleep: secular trends in the sleep time of school-aged children and adolescents. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(3):203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matricciani L, Olds T, Williams M. A review of evidence for the claim that children are sleeping less than in the past. Sleep. 2011;34(5):651–659. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: Developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1255–1273. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto CA, da Silva AG, Carskadon MA, Louzada FM. Adolescents living in homes without electric lighting have earlier sleep times. Behav Sleep Med. 2009;7(2):73–80. doi: 10.1080/15402000902762311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piosczyk H, Landmann N, Holz J, Feige B, Riemann D, Nissen C, Voderholzer U. Prolonged sleep under Stone Age conditions. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(7):719–722. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman SA, Flynn-Evans EE, Aeschbach D, Brainard GC, Czeisler CA, Lockley SW. Diurnal spectral sensitivity of the acute alerting effects of light. Sleep. 2014;37(2):271–281. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyner LA, Horne JA, Reyner A. Gender- and age-related differences in sleep determined by home-recorded sleep logs and actimetry from 400 adults. Sleep. 1995;18(2):127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg T, Kumar CJ, Merrow M. The human circadian clock entrains to sun time. Curr Biol. 2007;17(2):R44–R45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffwarg HP, Muzio JN, Dement WC. Ontogenetic development of the human sleep-dream cycle. Science. 1966;152(3722):604–619. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3722.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeggia CR, Burke KM, Fernandez-Duque E. Nutritional status and socioeconomic change among Toba and Wichi populations of the Argentinean Chaco. Econ Hum Biol. 2010;8(1):100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr T. The impact of changes in nightlength (scotoperiod) on human sleep. In: Turek FW, Zee PC, editors. Regulation of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1999. pp. 263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Wehr TA, Moul DE, Barbato G, Giesen HA, Seidel JA, Barker C, Bencer C. Conservation of pho-toperiod-responsive mechanisms in humans. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(34):R846–R857. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthman CM. Sleep in different cultures. Front Neurosci. 2009;3:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Worthman CM, Brown RA. Companionable sleep: Social regulation of sleep and cosleeping in Egyptian families. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(1):124–135. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KP, Jr, McHill AW, Birks BR, Griffin BR, Rusterholz T, Chinoy ED. Entrainment of the human circadian clock to the natural light-dark cycle. Curr Biol. 2013;23(16):1554–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitzer JM, Dijk DJ, Kronauer RE, Brown EN, Czeisler CA. Sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to nocturnal light: Melatonin phase resetting and suppression. J Physiol. 2000;526(3):695–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Locomotor activity and light exposure recorded during the summer with wrist data loggers. (A) Raster plots of activity for Toba/Qom individuals (n=6) from the NO-Electricity and Electricity communities throughout the summer sampling days. Black bars on each 24-h horizontal line represent the activity levels. Successive days are stacked vertically. (B) Top, Two representative raster plots for activity and light exposure plotted as in (A). Bottom, a waveform for each parameter for one individual plotted by averaging the activity or light exposure throughout the sampling days for each 20-min bin.