Abstract

PURPOSE

To compare effectiveness of fornix- and limbal-based conjunctival flaps in trabeculectomy surgery.

DESIGN

Systematic review.

METHODS

Setting

CENTRAL, MEDLINE, LILACS, ISRCTN registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO, and ICTRP were searched to identify eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Study Population

RCTs in which benefits and complications of fornix- vs limbal-based trabeculectomy for glaucoma were compared in adult glaucoma patients.

Observation Procedure

We followed Cochrane methodology for data extraction.

Main Outcome Measures

Proportion of failed trabeculectomies at 24 months, defined as the need for repeat surgery or uncontrolled intraocular pressure (IOP) > 22 mm Hg, despite topical/systemic medications.

RESULTS

The review included 6 trials with a total of 361 participants, showing no difference in effectiveness between fornix-based vs limbal-based trabeculectomy surgery, although with a high level of uncertainty owing to low event rates. In the fornix-based and limbal-based surgery, mean IOP at 12 months was similar, with ranges of 12.5–15.5 mm Hg and 11.7–15.1 mm Hg, respectively. Mean difference was 0.44 mm Hg (95% CI −0.45 to 1.33) and 0.86 mm Hg (95% CI −0.52 to 2.24) at 12 and 24 months of follow-up, respectively. Mean number of postoperative glaucoma medications was similar between the 2 groups. Mean difference was 0.02 (95% CI −0.15 to 0.19) at 12 months. As far as postoperative complications, an increased risk of shallow anterior chamber was observed in the limbal-based group.

CONCLUSION

Similar efficacy of trabeculectomy surgery with respect to bleb failure or IOP control was observed in both types of conjunctival flap incisions. A significant difference was detected in the risk of postoperative shallow anterior chamber, which was increased in the limbal-based group.

Glaucoma is a leading and largely preventable cause of blindness worldwide.1 Glaucoma-filtering surgery is one of the mainstay treatment options, especially for cases that are unresponsive to medical or laser therapy.2,3 Over the last 40 years, variations in surgical technique have been debated, including whether the conjunctival flap should be limbal- or fornix-based. Several studies of limbus-based vs fornix-based conjunctival flaps for trabeculectomy have been conducted,4,5 with differences in success criteria among those studies. Some investigators assessed success via outcomes such as intraocular pressure (IOP) measurements, while others assessed visual field progression, optic disc cupping, and changes in visual acuity.4,6–8 Furthermore, some investigators combined trabeculectomy with cataract extraction or application of antimetabolite therapy; and yet others combined it with both.8–11 Varying results regarding IOP outcomes and postoperative complications like hypotony, wound leak, and shallow anterior chamber have been observed.

We conducted a Cochrane systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to assess the effectiveness of fornix-based vs limbal-based trabeculectomy in 2015.12 We also summarized adverse events as reported in the included studies. The Cochrane review included all RCTs comparing these 2 approaches (fornix vs limbal incision) for trabeculectomy alone or in combination with cataract extraction or antimetabolite application of mitomycin C (MMC) or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), or both.

METHODS

We followed the methods recommended by Cochrane.13 The protocol for the original systematic review was published in 2011; the original systematic review was published in 2015.12 The American University of Beirut institutional review board waived the need for approval. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and all Lebanese federal laws.

DATA EXTRACTION

We included all RCTs assessing benefits and complication rates of fornix- vs limbal-based trabeculectomy for glaucoma among adults (at least 18 years old), irrespective of publication status and language. Uncontrolled glaucoma was defined as an IOP above 21 mm Hg with or without progressive visual field loss or optic disc cupping despite maximal medical therapy. We included RCTs that enrolled participants irrespective of the type of glaucoma or evidence of cataract, refractive errors, retinal problems, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension. We included trials in which participants underwent trabeculectomy using either the limbal or fornix approach, with or without the use of antimetabolites, and with or without concurrent cataract surgery. Only RCTs in which participants were trabeculectomy treatment naïve with at least 12 months of follow-up were included.

RCTs that included participants younger than 18 years of age were excluded, since wound healing is different in this age group and the rate of bleb scarring postoperatively is higher.14

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROCESS

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) (2015, Issue 9), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to October 2015), EMBASE (January 1980 to October 2015), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS) (January 1982 to October 2015), the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). There were no date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on October 23, 2015. Detailed search strategies for the electronic databases are provided in the Cochrane systematic review.12

We reviewed the bibliographic references of included RCTs to discover additional RCTs not identified by the electronic searches. We contacted researchers and practitioners active in the field of glaucoma to identify other published and unpublished trials.

TRIAL SELECTION

Two authors independently reviewed titles and abstracts of all records identified by the electronic search using the criteria for considering studies for this review.12 The final eligibility decision was based on review of the full text of articles labeled definitely or potentially eligible for inclusion by 1 author. We contacted the investigators of studies classified as “unsure” for further clarification. We documented reasons for exclusion of trials.

OUTCOMES OF INTEREST

The primary outcome for the review was assessment of the proportion of failed trabeculectomies at 24 months and mean postoperative IOP at 24 months. Failure of trabeculectomy was defined as the need for repeat surgery or uncontrolled IOP (more than 22 mm Hg) despite additional topical/systemic medications. Secondary outcomes were the proportion of failed trabeculectomies at 12 months, mean postoperative IOP at 12 months, the proportion of subjects with loss of visual acuity equal to or greater than 0.3 logMAR at 12 months, number of medications required after surgery at 12 and 24 months of follow-up, and the proportion of subjects experiencing any postoperative adverse events at any time of the study, including wound leaks, hypotony, choroidal hemorrhage, shallow anterior chamber, endophthalmitis, and bleb-related infection.

DATA COLLECTION AND ASSESSMENT OF TRIALS FOR RISK OF BIAS

Two authors independently extracted data regarding trial characteristics, methods, participants, interventions, and outcomes, using a form developed by Cochrane Eyes and Vision.13 In case of more than 1 publication of the same RCT, we reviewed data from all articles and extracted data as appropriate. One author entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) and a second review author reviewed the accuracy of all entries.15

Risk of bias of the included trials was assessed by 2 authors independently according to the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.13 This assessment focused on selection of trial participants, masking of outcomes assessors, masking of outcome reporting, incomplete outcome data reporting, and selective outcome reporting. Trials were categorized as being at high, unclear, or low risk of bias for each aspect assessed. For unclear issues, we contacted the investigators of the studies for additional information.

DATA SYNTHESIS AND ANALYSIS

Data synthesis and analysis were guided by Cochrane methods.13 We estimated risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes. For the outcome of failed trabeculectomy, we had initially planned to calculate a summary RR with 95% CI as dichotomous outcome. As a post hoc decision, owing to the low number of events reported, we used a fixed-effect model. For mean IOP and mean number of medications as continuous outcomes, we calculated mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs. The unit of analysis was the eye; there was 1 eye for each participant in 2 studies, 2 studies enrolled a few bilateral cases, and 2 studies enrolled bilateral cases exclusively. When both eyes from 1 participant were included in a trial, we extracted and analyzed the data to properly account for the non-independence of eyes, following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.14

In case of missing data or difficulty in interpretation, study investigators were contacted. However, no additional data could be obtained. Consequently, we conducted an “available case analysis,” analyzing data as provided in the individual studies, as the primary analysis.

We based our assessment of statistical heterogeneity of outcomes using the I2 and χ2 statistics. Statistical heterogeneity was considered as substantial either when the I2 statistic was greater than 50% or when the P value was <.10 in the χ2 test for heterogeneity. Clinical and methodological heterogeneity of included studies were also assessed by examining variations in the study design and methods, characteristics of the participants, variation in interventions, and length of follow-up.

We used RevMan 2014 to perform statistical analyses.15 We used a fixed-effect model for meta-analysis. We did not detect sufficient clinical heterogeneity or substantial heterogeneity to use a random-effects model for any primary meta-analysis. Although we planned to perform subgroup analyses of trabeculectomy without any additional procedure, trabeculectomy with use of antimetabolites (MMC or 5-FU), trabeculectomy with cataract surgery, and trabeculectomy with cataract surgery and use of antimetabolites, the analysis was not possible owing to insufficient data and low number of trials.

RESULTS

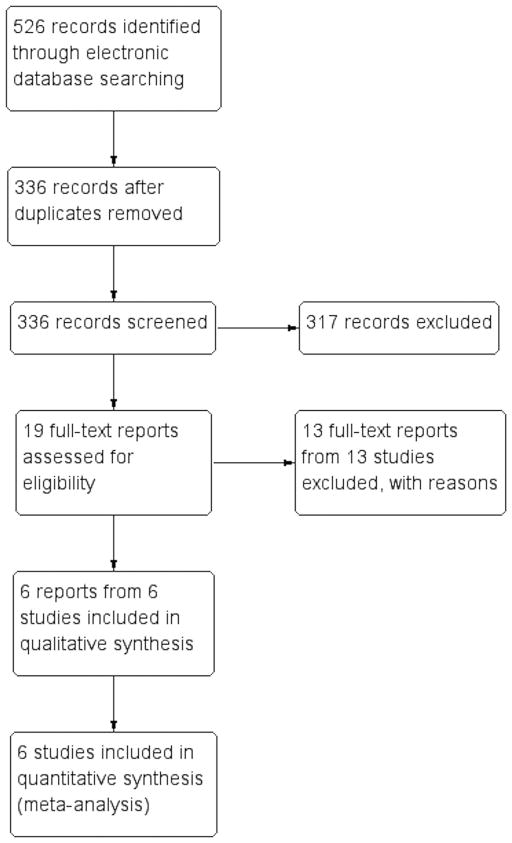

FROM A TOTAL OF 526 RECORDS RETRIEVED, WE EXCLUDED duplicate records and screened 336 records. We obtained 19 full-text reports for further assessment, out of which 13 studies were excluded. Of these, 6 trials met the criteria for inclusion7,9–11,16,17 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Selection of trials comparing fornix-based with limbal-based conjunctival trabeculectomy flaps in glaucoma surgery.

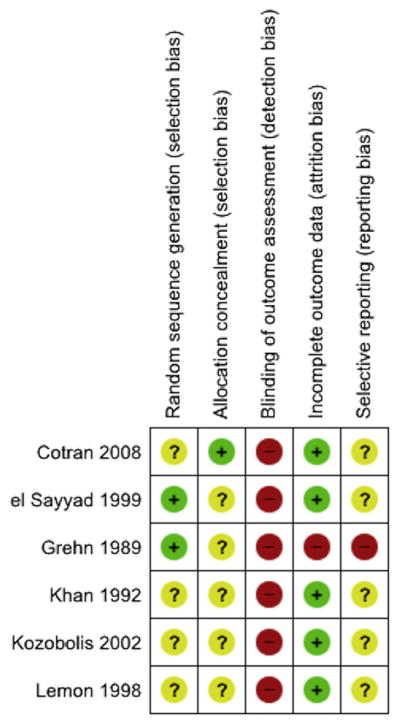

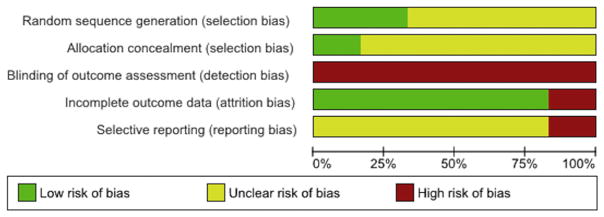

A total of 361 participants were enrolled in the 6 trials. Two of the trials were conducted in the United States of America11,16 and 1 each in Germany,7 Greece,10 India,17 and Saudi Arabia.9 No corresponding clinical trial registrations were identified for any of the included trials. Risk of bias was judged unclear or high for most domains assessed (Figures 2 and 3).

FIGURE 2.

Review authors’ judgment of the risk of bias in the different trials comparing fornix-based with limbal-based conjunctival trabeculectomy flaps in glaucoma surgery.

FIGURE 3.

Risk of bias summary, presented as percentages, of trials comparing fornix-based with limbal-based conjunctival trabeculectomy flaps in glaucoma surgery.

All included trials compared fornix-based vs limbal-based trabeculectomy surgery for glaucoma. Three studies used a combined procedure (trabeculectomy plus phacoemulsification) for all participants.10,11,16 One study used a 1-site phacotrabeculectomy in the fornix-based conjunctival flap group and a 2-site phacotrabeculectomy in the limbal-based conjunctival flap group.16 Trabeculectomy with MMC was performed for all participants in 3 studies.10,11,16 Trabeculectomy with 5-FU was used in 1 study.9 Two trials did not report using either MMC or 5-FU.7,17

OUTCOMES

All trials had at least 12 months of follow-up; 3 trials had at least 24 months of follow-up.9,16

Failed trabeculectomy

None of the included trials reported trabeculectomy failure at 24 months. One trial noted that 2 of 43 (4.6%) eyes in each group required reoperation during 3 years of follow-up.16 Three trials evaluated failure rate of trabeculectomy at 12 months.9,10,17 No failures were observed in 2 of these trials (118 eyes), precluding an estimation of the Peto odds ratio (OR) and inclusion in meta-analysis.9,10 In 1 study, 1 of 50 eyes (2%) failed trabeculectomy in the fornix group, compared with 3 of 50 eyes (6%) in the limbal group (Peto OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.05 to 2.61).17 Two trials did not report trabeculectomy failure at any time point.7,11

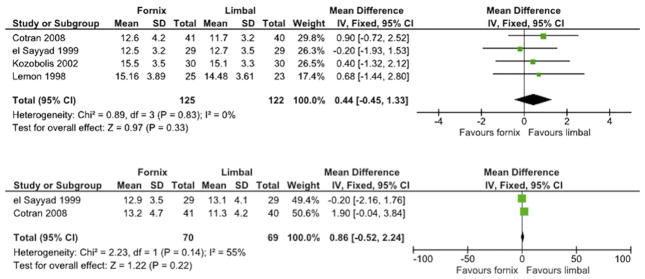

Mean postoperative intraocular pressure

Three trials reported mean IOP at 24 months, a primary outcome measure in our review.7,9,16 One study did not report precision measures for effect estimates, but found that mean IOP was 17 mm Hg in both groups 24 months postoperatively7 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of trials comparing fornix-based vs limbal-based trabeculectomy surgery with respect to mean intraocular pressure at 12 months (Top) and 24 months (Bottom).

All included studies, with the exception of 1, reported mean IOP at 12 months postoperatively.7,9–11,16

Visual acuity outcomes

Four trials reported visual acuity outcomes10,11,16,17; however, none reported outcomes assessed as the proportion with a loss of visual acuity equal to or greater than 0.3 logMAR (Snellen visual acuity loss of 2 lines or more). One trial assessed visual deterioration at 1 month17; 2 studies reported visual acuity improvement at 12 months10 or 18 months.11 No trial reported visual acuity outcomes at 24 months. One trial studied visual acuity deterioration at 1 month17: 10 of 50 eyes (20%) in the fornix-based surgery group and 15 of 50 eyes (30%) in the limbal-based surgery group had visual acuity deterioration. Two trials assessed improvement in vision: 1 study noted no difference between the 2 types of incisions at 12 months.10 One study reported vision improvement was more favorable but not significantly better in the fornix-based group after 18 months.11 Two trials studied phacotrabeculectomy outcomes. One trial reported that “corrected visual acuity improved markedly in both groups after surgery,” but there was minimal clinical difference in Snellen decimal acuity between groups at 3 months after surgery (MD −0.09, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.00; 86 eyes).16 Two trials did not report visual acuity outcomes at any time point.7,9

Mean number of antiglaucoma medications

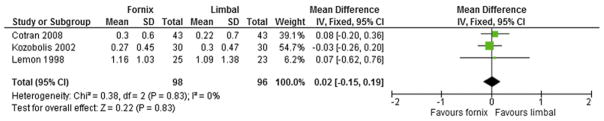

Four trials reported the mean number of medications needed to control IOP after surgery: 1 at 4 months, 2 at 12 months, and 1 at both 12 and 24 months.7,10,11,16 One trial reported the number of antiglaucoma medications at 24 months,16 with no difference noted between surgical groups (MD −0.09 mm Hg, 95% CI −0.43 to 0.25; 86 eyes). Three trials reported the mean number of antiglaucoma medications at 12 months of follow-up.10,11,16 Analysis of the available data in the 3 trials showed no difference among surgical groups in the mean number of postoperative IOP-lowering medications at 12 months (MD 0.02, 95% CI −0.15 to 0.19; 194 eyes) (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of trials comparing fornix- vs limbal-based trabeculectomy surgery with respect to mean number of antiglaucoma medications at 12 months.

In 1 trial, there was no difference in the number of anti-glaucoma medications between groups at 4 months of follow-up7; no data at 12 or 24 months of follow-up were reported. Two trials did not report the mean number of antiglaucoma medications needed.9,17

Quality of life

Quality-of-life data were not reported in any of the included studies.

Adverse events

Although adverse events were reported in all trials, the types of adverse events varied. No trial reported the number of participants with expulsive hemorrhage (choroidal hemorrhage), early or late endophthalmitis, or bleb-related discomfort or pain. The Table summarizes the most common complications reported. The only significant difference was the higher risk of shallow anterior chamber after limbal-based surgery compared with fornix-based surgery, which was observed in 4 trials.

TABLE.

Adverse Events for Fornix-Based Versus Limbal-Based Trabeculectomy

| Adverse Event | Number of Trials | Number of Participants | Odds Ratio [95% Confidence Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | |||

| Wound leak | 3 | 185 | 1.20 [0.37 to 3.87] |

| Hypotony | 3 | 198 | 1.97 [0.68 to 5.74] |

| Shallow anterior chamber | 4 | 302 | 0.44 [0.22 to 0.92] |

| Bleb infection | 1 | 86 | 0.33 [0.01 to 8.22] |

| Choroidal detachment | 2 | 125 | 0.60 [0.13 to 2.85] |

| Choroidal effusion | 2 | 146 | 0.55 [0.15 to 1.97] |

| Hyphema | 3 | 215 | 0.66 [0.20 to 2.17] |

| Corneal toxicity | 2 | 112 | 1.39 [0.45 to 4.30] |

| Conjunctival bleb leak within 3 months | 1 | 86 | 15.08 [0.82 to 276.66] |

| Conjunctival bleb leak after 3 months | 1 | 86 | 0.19 [0.01 to 4.09] |

| Avascularized bleb | 1 | 62 | 2.74 [0.88 to 8.55] |

| Hypertrophy of bleb | 1 | 100 | 0.13 [0.01 to 2.60] |

| Iridocyclitis | 1 | 100 | 0.64 [0.17 to 2.41] |

| Intraoperative trauma to lens | 1 | 100 | 0.65 [0.10 to 4.09] |

| Cataract requiring surgery | 1 | 100 | 0.14 [0.03 to 0.71] |

| Capsule opacification | 1 | 60 | 1.00 [0.28 to 3.54] |

| Cystic bleb/bleb fibrosis | 1 | 60 | 1.56 [0.24 to 10.05] |

| Fibrin exudation | 1 | 60 | 0.69 [0.21 to 2.30] |

| Pupillary membrane | 1 | 60 | 0.46 [0.08 to 2.75] |

| Cystoid macular edema | 1 | 69 | 2.38 [0.09 to 60.42] |

| Hemiretinal vein occlusion | 1 | 69 | 0.25 [0.01 to 6.33] |

| Postoperative procedures | |||

| Needling with 5-fluorouracil | 2 | 155 | 0.63 [0.22, 1.81] |

| Suture lysis procedure | 3 | 211 | 1.07 [0.50, 2.29] |

| Digital massage | 1 | 86 | 1.63 [0.53 to 5.07] |

| Releasable suture removal | 1 | 60 | 0.85 [0.27 to 2.67] |

| Repair of wound | 1 | 69 | 0.49 [0.08 to 3.11] |

DISCUSSION

In this summary review of findings from 6 randomized controlled trials (with 361 participants) in which we compared surgical outcomes of fornix- vs limbal-based conjunctival flaps for trabeculectomy surgery, no difference was observed between the 2 groups, although with a high level of uncertainty. This was owing mostly to low event rates and wide confidence intervals. This also applied to postoperative complications, except for the incidence of postoperative shallow anterior chamber, which was twice as common in limbal-based trabeculectomy as compared with fornix-based trabeculectomy. As far as other complications, although limbal-based surgeries were reportedly better in regard to wound leakage, hypotony, bleb leak and bleb fibrosis, we were very uncertain as to a definite effect of incision type on those complications owing to the small number of cases reported. In addition, the risk of chance findings is increased when multiple analyses of several rare adverse events are conducted.

Clinically, no significant difference was found between groups with regard to postoperative IOP measurements or number of glaucoma medications needed after surgery. In eyes that have had multiple surgeries or significant scarring, fornix-based flaps tended to provide better surgical exposure for dissection of the scleral flap and better access to the trabeculectomy performed at the iris root. Also in combined procedures where trabeculectomy was performed with cataract surgery, fornix-based surgery provided easier access to the surgical wound. Three of the trials studied phacotrabeculectomy with MMC10,11,16; 1 studied trabeculectomy with 5-FU9; and 2 were done on isolated trabeculectomy.7,17 Although we included combined procedures (phacotrabeculectomy and use of antimetabolites), results should be viewed with that consideration in mind. The number of eligible trials was too small to allow subanalysis by the specific type of procedure performed or antimetabolite used. Phacotrabeculectomy entails performing 2 surgeries (cataract and glaucoma surgery); thus the operating time is longer and the risk of potential complications is higher than a simple trabeculectomy. Surgical outcomes would also be expected to differ between 1-site and 2-site phacotrabeculectomy, and that requires subgroup comparison. This could not be practically performed in this review owing to the small numbers of eligible trials. Of note is that lens extraction may have an effect on IOP18,19; the use of antimetabolites similarly has an additional effect on glaucoma control.20

Selecting the best outcome measure in glaucoma research is a difficult and nonstandardized process. A systematic review by Ismail and associates showed that a large variability exists in outcomes selected in glaucoma Cochrane Reviews and Protocols, with IOP being the most commonly used outcome measure; in addition, inconsistency was noted among those reviews and protocols.21–23 Our main outcome measures were trabeculectomy failure and mean IOP at 24 and 12 months postoperatively. However, glaucoma is a chronic disease and long-term follow-up is needed to assess surgical success. Most trial investigators assessed IOP as the main measure of glaucoma control; visual field loss and cup-to-disc ratio have not been well reported. Trials where visual acuity was measured were those studying phacotrabeculectomy outcomes, and thus improvement in visual acuity would be more related to the cataract extraction than to glaucoma surgery or IOP control.10,11 Prognosis and approach to management also vary by type of glaucoma. Although most participants in the included trials had primary open-angle glaucoma, 1 trial also enrolled subjects with pseudoexfoliative glaucoma10 and another included eyes with narrow-angle glaucoma.17 Postoperative course and complications are expected to be different among these types of glaucoma; for example, eyes with pseudoexfoliative glaucoma had higher rates of fibrin exudation and pupillary membrane formation.10

With only 6 trials in this review, no difference in effectiveness and complications between fornix- vs limbal-based trabeculectomy surgery was noted, except in the risk of postoperative shallow anterior chamber (with moderate evidence). We found 3 trials that assessed the failure rate between fornix and limbal trabeculectomy at 12 months of follow-up, and none reported the failure rate at 24 months. Throughout our search we found other studies that compared fornix to limbal trabeculectomy, but most were not randomized and some of them had only short-term follow-up, so they were excluded.

The primary outcome for most of the studies was the mean IOP at a specific follow-up time. The definition of trabeculectomy failure was variable across studies with different cutoffs for acceptable IOP. Similarly, there were discrepancies in definitions for vision deterioration and the time point in the postoperative period that these outcomes were measured. IOP measurements are subjective and thus are prone to “examiner bias,” especially when not masked. Central corneal thickness does affect IOP measurement, and this confounding factor has not been considered in the included studies. Combined procedures (like trabeculectomy and cataract surgery) introduce additional sources of bias when deriving conclusions from these studies.

All the trials included in this review used randomized controlled methodology and did not report masking of the outcomes. Most of the outcomes studied in the 6 trials included in this review were uniformly reported in all the trials. No study reported outcomes for failed trabeculectomy at 24 months after surgery. At 12 months, we graded the quality of the evidence as low, owing to methodological issues with 1 study that reported this outcome and the high degree of imprecision in the effect estimate. The quality of the evidence was moderate for estimates of IOP at 24 and 12 months. For this outcome, the measurements at 12 and 24 months both had confidence intervals that crossed the null and were within 3 mm Hg. Addition of other studies could change the point estimate of the effect, but is unlikely to change the clinical implications. Because of the small numbers of events and total participants, the risk of many reported adverse events was uncertain and those that were found to be statistically significant may have been owing to chance. Another limitation is that for the outcome of number of glaucoma medications, the distribution was skewed and thus had a large standard deviation. Based on the data available in the reported studies, accounting for this asymmetry was not possible and further subanalysis could not be performed.

All relevant studies have been included in this review. The decision to exclude 1 RCT was based on the difficulty in obtaining all the necessary data.24 If trials with negative findings are more likely to remain unpublished (publication bias), the difference between the limbal and fornix approach in trabeculectomy surgery may not be fully estimated in this review. Some criteria regarding risk of bias were not clear in a number of studies, and efforts to contact the authors have failed; these were thus labeled as “unclear.” Also, we intended to perform further subgroup analyses, but because of insufficient data and the small number of trials included in this review, we could not practically perform such an analysis. Results of this systematic review agreed with most of the previous reviews and studies in that no statistically significant difference in IOP control between the 2 techniques existed.25

In conclusion, similar efficacy of trabeculectomy surgery with respect to IOP control or bleb failure was observed in both types of conjunctival flap incisions (fornix- vs limbal-based). A significant difference was detected in the risk of postoperative shallow anterior chamber, which was increased in the limbal-based group. In patients with preexisting shallow chambers or at risk of such a complication, fornix-based conjunctival flaps are a safer option when performing trabeculectomy surgery. Longer follow-up time is needed to assess long-term surgical failure and IOP control, glaucoma being a chronic disease. Results reported in this review were at 12 and 24 months of follow-up; future trials with longer follow-up could detect differences in surgical outcomes not identified at this time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Cochrane Eyes and Vision in this work.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: NO FUNDING OR GRANT SUPPORT. FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: THE FOLLOWING AUTHORS HAVE NO financial disclosures: Christiane E. Al-Haddad, Marwan Abdulaal, Ahmad Al-Moujahed, Ann-Margret Ervin, and Karine Ismail. All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Supplemental Material available at AJO.com.

References

- 1.Thylefors B, Negrel AD, Pararajasegaram R, Dadzie KY. Global data on blindness. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73(1):115–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairns JE. Trabeculectomy. Preliminary report of a new method. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66(4):673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson P. Trabeculectomy. A modified ab externo technique. Vestn Oftalmol. 1970;2:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shuster JN, Krupin T, Kolker AE, Becker B. Limbus- v fornix-based conjunctival flap in trabeculectomy. A long-term randomised study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(3):361–362. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030279018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tezel G, Kolker AE, Kass MA, Wax MB. Comparative results of combined procedures for glaucoma and cataract: II. Limbus based versus fornix-based conjunctival flaps. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1997;28(7):551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alwitry A, Patel V, King AW. Fornix vs limbal-based trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Eye. 2005;19(6):631–636. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grehn PD, Mauthe S, Pfeiffer N. Limbus-based versus fornix-based conjunctival flap in filtering surgery. A randomized prospective study. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13(1–2):139–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02028654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murchison JF, Jr, Shields MB. Limbal-based vs fornix-based conjunctival flaps in combined extracapsular cataract surgery and glaucoma filtering procedure. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109(6):709–715. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72441-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.el Sayyad F, el-Rashood A, Helal M, Hisham M, el-Maghraby A. Fornix-based versus limbal-based conjunctival flaps in initial trabeculectomy with postoperative 5-fluorouracil: four-year follow-up findings. J Glaucoma. 1999;8(2):124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozobolis VP, Siganos CS, Christodoulakis EV, Lazarov NP, Koutentaki MG, Pallikaris IG. Two-site phacotrabeculectomy with intraoperative mitomycin-C: fornix-versus limbus-based conjunctival opening in fellow eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28(10):1758–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemon LC, Shin DH, Kim C, Bendel RE, Hughes BA, Juzych MS. Limbus-based vs fornix-based conjunctival flap in combined glaucoma and cataract surgery with adjunctive mitomycin C. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125(3):340–345. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Haddad C, Abdulaal M, Al-Moujahed A, Ervin AM. Fornix-based versus limbal-based conjunctival trabeculectomy flaps for glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;11:CD009380. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009380.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Accessed September 23, 2016]. Available at: http://handbook.cochrane.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parc CE, Johnson DH, Oliver JE, Hattenhauer MG, Hodge DO. The long-term outcome of glaucoma filtration surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00923-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Review Manager (RevMan) [computer software]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotran PR, Roh S, McGwin G. Randomized comparison of 1-site and 2-site phacotrabeculectomy with 3-year follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(3):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan AM, Jilani FA. Comparative results of limbal based versus fornix based conjunctival flaps for trabeculectomy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1992;40(2):41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman D, Vedula SS. Lens extraction for chronic angle-closure glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD005555. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005555.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrivastava A, Singh K. The effect of cataract extraction on intraocular pressure. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(2):118–122. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283360ac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkins M, Indar A, Wormald R. Intraoperative mitomycin C for glaucoma surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD002897. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002897.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ismail R, Azuara-Blanco A, Ramsay CR. Consensus on outcome measures for glaucoma effectiveness trials: results from a delphi and nominal group technique approaches. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(6):539–546. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ismail R, Azuara-Blanco A, Ramsay CR. Variation of clinical outcomes used in glaucoma randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(4):464–468. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismail R, Azuara-Blanco A, Ramsay CR. Outcome measures in glaucoma: a systematic review of Cochrane reviews and protocols. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(7):533–538. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auw-Hädrich C, Bömer TG, Funk J. Limbus-based versus fornix-based conjunctival flap in trabeculectomy: long-term results after 6–9 years. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36(4):S343. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohl DA, Walton DS. Limbus-based versus fornix based conjunctival flaps in trabeculectomy: 2005 update. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005;45(4):107–113. doi: 10.1097/01.iio.0000176369.93887.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.