Abstract

The terrestrial vegetation emits large amounts of volatile organic compounds (VOC) into the atmosphere, which on oxidation produce secondary organic aerosol (SOA). By acting as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN), SOA influences cloud formation and climate. In a warming climate, changes in environmental factors can cause stresses to plants, inducing changes of the emitted VOC. These can modify particle size and composition. Here we report how induced emissions eventually affect CCN activity of SOA, a key parameter in cloud formation. For boreal forest tree species, insect infestation by aphids causes additional VOC emissions which modifies SOA composition thus hygroscopicity and CCN activity. Moderate heat increases the total amount of constitutive VOC, which has a minor effect on hygroscopicity, but affects CCN activity by increasing the particles' size. The coupling of plant stresses, VOC composition and CCN activity points to an important impact of induced plant emissions on cloud formation and climate.

Volatile organic compounds (VOC) emitted by vegetation influence cloud formation, yet the impact of environmental stresses remains little known. Here, manipulation experiments reveal insect infestation and heat stress are linked to induced VOC and constitutive VOC emissions shifts, respectively.

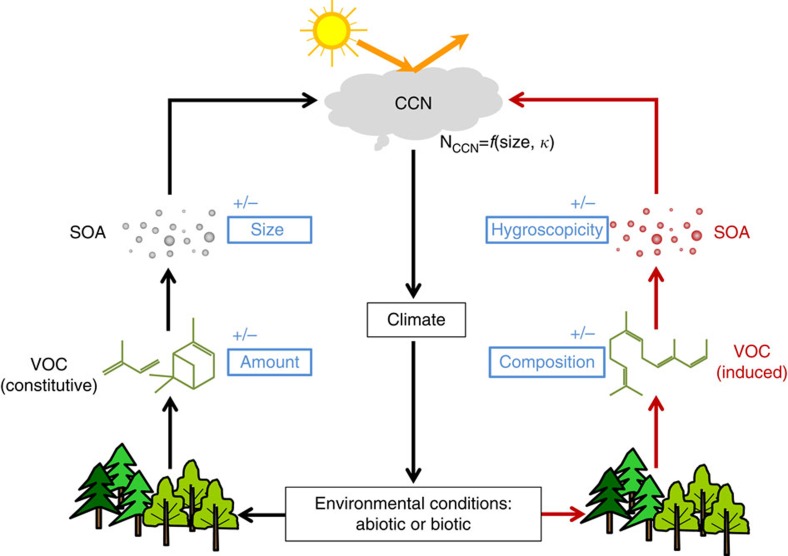

Volatile organic compounds (VOC) such as isoprene and terpenes emitted by plants have various biological functions, including plant growth, defense and communication1,2. It is estimated that 1,000 Tg of biogenic VOC are emitted globally per year, far exceeding total VOC emissions from human activities1,3. The VOC emissions from plants are closely coupled to cloud formation and climate via the formation of secondary organic aerosol (SOA)4,5,6 that contribute to the regional and global cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) budget7 (Fig. 1). VOC emissions are regulated by biotic and abiotic environmental factors. Heat, drought or infestation, are stress factors that cause deviations from the plants' optimal living conditions. Environmental factors and stresses change plant emissions significantly in two ways8,9,10. They can either increase or decrease the amount of constitutive VOC (Fig. 1, left path), or stimulate biochemical pathways that induce the emission of other types of VOC. The latter shifts the overall emission composition8, that is, the relative contributions of different classes of VOC (Fig. 1, right path). Such changes in emitted VOC result in changes of SOA particle size and chemical composition, hence hygroscopicity. Since both, size and hygroscopicity, determine the CCN activity of SOA11, changes in VOC will eventually influence cloud formation, and ultimately impact climate12,13. Already at present, environmental stress factors strongly affect plants14,15. According to regular inspections of forest plots, more than 40% of forest trees in Europe suffer from various stresses where biotic stresses account for ∼40% of the total stresses14,16. With climate change, stressors such as heat waves, droughts and infestation are projected to intensify and to more often influence the plants' environmental conditions15 (Fig. 1). This implies a potential important feedback between plants' emissions and climate13.

Figure 1. Interactions of plant emissions and cloud formation.

The schematic shows the interactions of environmental conditions, plant volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions, secondary organic aerosol (SOA), cloud formation and climate. In unstressed conditions, plants emit constitutive VOC (black arrows on the left path), which on oxidation form SOA that act as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) and can affect cloud formation and climate. Unfavourable environmental conditions (stresses) can induce VOC emissions (red arrows on the right path). Climatic changes and the resulting environmental conditions can affect the amount of constitutive VOC emissions and/or induce VOC emissions that modify the VOC composition. Such alterations in VOC emissions will be reflected in the particle size and/or particle composition. The latter determines the hygroscopicity parameter (κ) of the SOA, which is a measure of CCN activity at a given particle size. Both, particle size and κ, determine the CCN number concentration (NCCN) (cf. Supplementary Fig. 5), and thus affect cloud formation and climate. +/− indicates the changes of parameters.

The effects of environmental factors on VOC emissions of plants have been investigated in a number of studies, but significantly less than their effects on the net CO2 exchange of plants8,9,17. Only few studies addressed effects of environmental factors on induced VOC emissions and SOA formation10,12,18. Importantly, the eventual effects of environmental factors on the CCN activity of SOA and on CCN concentrations are unknown so far, restricting our understanding of how terrestrial plants interact with climate.

We address this gap with a new laboratory study on how plant emissions induced by biotic and abiotic environmental factors modify the hygroscopicity and CCN activity of SOA. We investigated the effect of aphid infestation as an example of biotic stresses and the effect of heat and drought as examples of abiotic stresses for both constitutive emissions and induced emissions. VOC emissions were taken from a mixed stand of pine, spruce, and birch, typical for boreal forests (thereafter referred to as boreal trees) and of individual trees of the same types kept in the Jülich Plant Atmosphere Chamber (JPAC)19 under varying conditions. SOA was formed by photochemical oxidation of constitutive and induced VOC (via homogeneous nucleation) and the CCN activity of the SOA particles was directly determined (see Methods section and Supplementary Fig. 1). It is found that insect infestation, as an example of biotic factors, caused additional VOC emissions which modified SOA composition thus hygroscopicity and CCN activity. And heat, as an example of abiotic factors, increased the total amount of constitutive VOC emissions, which had a minor effect on the hygroscopicity of SOA, but affected CCN activity by increasing the particles' size.

Results

Effect of insect infestation

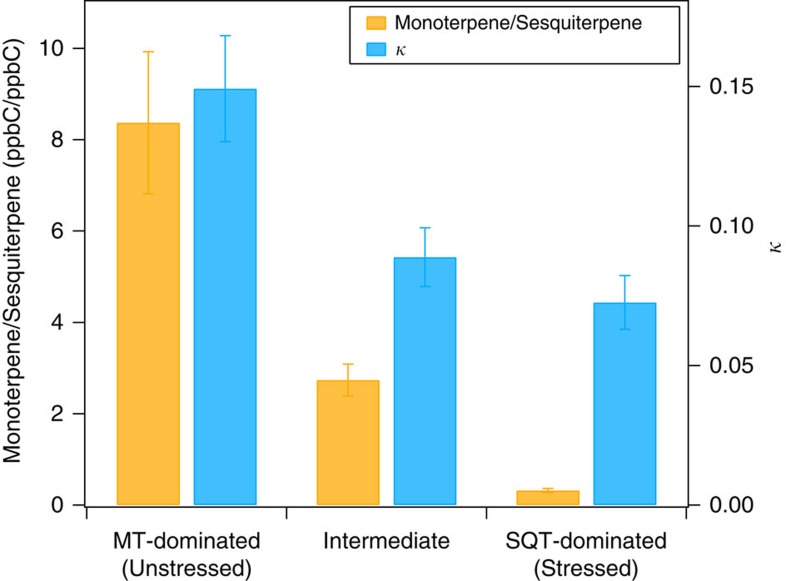

The constitutive VOC emissions of boreal trees in the absence of stresses are dominated by monoterpenes19 (see also Supplementary Fig. 2). Under biotic stress such as insect infestation, the composition of emitted VOC changes significantly and is often dominated by induced VOC such as sesquiterpenes and green leaf volatiles2,8,18. The CCN activity of SOA is characterized using the hygroscopicity parameter κ, wherein higher κ indicates higher CCN activity for particles of a given size. For comparison, the highly water-soluble inorganic salt ammonium sulfate has a κ of ∼0.6 and highly water insoluble and non-wettable black carbon has a κ of 0. κ was ∼0.15 for SOA from monoterpene-dominated VOC emissions from unstressed pines, composed of 78% monoterpenes and 8% sesquiterpenes (Fig. 2, ‘MT-dominated' case). During the measurements with insect infested boreal trees, sesquiterpenes dominated the VOC emissions (72% of the total carbon). Concomitant with the shift of the emission composition from monoterpene-dominated to sesquiterpene-dominated, κ of SOA decreased significantly from 0.15±0.02 to 0.07±0.01 (Fig. 2). Particles from VOC emissions with moderate sesquiterpene fraction (monoterpenes 70% versus sesquiterpenes 27%, Fig. 2, ‘intermediate' case) have κ values in the middle of the monoterpene- and sesquiterpene-dominated cases. While the monoterpene emission was more than double of the sesquiterpene emission for the intermediate case, the amount of sesquiterpene oxidation products in the particles was estimated to be similar to that of monoterpene oxidation products, since the particle yield of sesquiterpene oxidation is substantially higher than that of monoterpene oxidation (17% versus 5%)18,19 (see Methods section). Therefore, the CCN activity was still significantly reduced compared with the unstressed monoterpene-dominated case. As shown below, such changes of κ can significantly affect the CCN number concentration, demonstrating the important influence of the emission composition on the CCN activity of SOA.

Figure 2. Volatile organic compounds composition and hygroscopicity parameter κ.

The ratio of monoterpene (MT) to sesquiterpene (SQT) emissions (ppbC/ppbC, yellow bar, left axis) from unstressed trees (monoterpene-dominated emissions) and biotically stressed (aphid infestation) boreal trees (sesquiterpene-dominated emissions) and the corresponding κ value (blue bar, right axis) of the resulting secondary organic aerosol (SOA) are shown. The emissions from unstressed trees are from pines here. The ‘intermediate' case was obtained for the emissions of stressed boreal trees in the dark, when fractions of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes were between those of monoterpene-dominated and sesquiterpene-dominated cases. The emissions here were obtained at room temperature (22–25 °C). The error bars represent the standard deviations of measurements for κ and volatile organic compounds concentrations (see Supplementary Table 3 for detailed data).

The decrease of κ is related to the different chemical composition of the SOA from sesquiterpene-dominated emissions compared with that from monoterpene-dominated emissions. According to Petters and Kreidenweis20 (equation (3), see Methods section), κ is inversely proportional to the molecular weight of the solute compound provided that all other parameters are constant. The average sesquiterpene oxidation products have higher molecular weight than those from monoterpene oxidation due to higher carbon number and higher molecular weight of sesquiterpenes (sesquiterpene 204 g mol−1 versus monoterpene 136 g mol−1)21,22,23. Therefore, κ is expected to be lower for SOA from emissions with higher sesquiterpene fractions. κ of SOA from monoterpene- and sesquiterpene-dominated emissions in our study are generally consistent with κ of SOA from the oxidation of single monoterpenes and single sesquiterpenes21,24,25,26,27,28 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), considering the difference in VOC and experimental conditions which can cause variations of κ. We conclude that the presence of induced sesquiterpene emissions lowers κ.

Effects of heat and drought

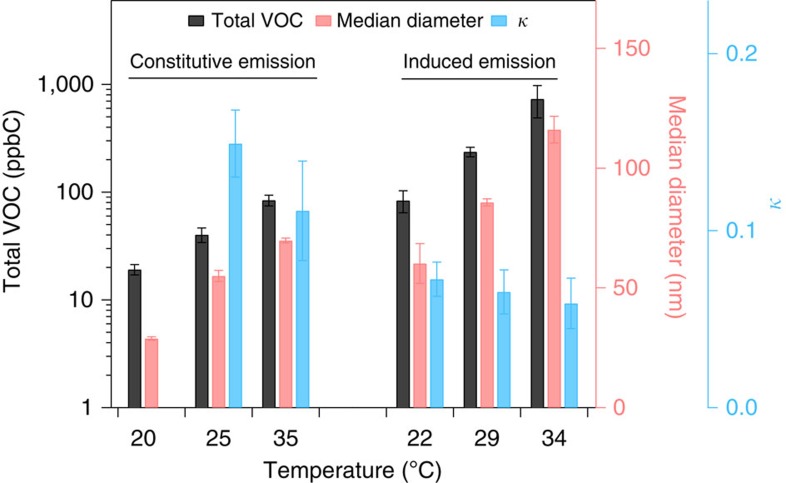

In contrast to biotic factors, abiotic factors such as mild heat (up to 35 °C) did not significantly change the relative contributions of the different VOC classes (monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and others, as described in Method) for both constitutive emissions (Supplementary Fig. 2) and induced emissions (Supplementary Fig. 3). Within each class, the contribution of some individual compounds changed, most distinct in the ‘others' class, because specific compounds respond to temperature changes differently (cf. Supplementary Fig. 4). However, even mild heat increased the total VOC emissions for both types of emissions substantially (Fig. 3), consistent with previous studies9,29. Accordingly, heat led to larger SOA particles under similar photooxidation conditions, but the κ values of the SOA remained relatively invariant as temperature changed, with a seemingly small decreasing trend with increasing plant temperature. For the SOA from constitutive emissions, the difference of κ between 25 and 35 °C are not statistically significant (t-test, P=0.09) and for the SOA from induced emissions, the difference in κ is significant only for the entire temperature interval of 22–34 °C (t-test, P=0.017, Fig. 3). The latter may be partly due to the detailed changes in the ‘others' class or minor variations in the contributions of specific VOC classes. In this study, the particles were formed by homogeneous nucleation which means that particle number and particle size increased with increasing emissions. In the presence of pre-existing particles, only the size of the particles will be affected.

Figure 3. Effect of heat on emission amounts and particle properties.

The mixing ratios of total volatile organic compounds (VOC) from plant emissions (black bar, note log axis), median diameter of aerosol particles (red bar) and hygroscopicity parameter κ (blue bar) is plotted as a function of plant temperature. The constitutive emissions from unstressed pine trees and induced emissions from stressed mixed boreal trees are shown. The error bars represent the s.d. of the measurement (the detailed number of measurements included in Supplementary Table 4). For constitutive emissions at 20 °C, κ data are not available (noted by *) because particle sizes were too small (median diameter 26 nm) for cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) activation measurements.

The CCN activity of particles is determined by their size and hygroscopicity7,11,30. The effect of elevated plant temperature on particle size was dramatic due to the substantial increase in the amount of VOC emitted and thus their oxidation products, which enhanced particle growth by condensation. However, the effect of elevated plant temperature on κ itself was small, which is attributed to the overall little change in the emission composition. κ determines the critical diameter for CCN activation. Larger aerosol size at constant κ implies that more particles will be activated and more cloud droplets will be formed (see also Supplementary Fig. 5). Moreover, the effect of mild heat on particle size and κ is independent whether the emissions are constitutive or induced. The effect of heat in the case of induced emissions by biotic stress represent the effect of co-occurring stressors, a common situation for plants under natural conditions31.

In addition to heat, we also investigated the effect of water shortage (drought) on plant VOC emissions. Similar to the effect of heat, we found that with monoterpenes dominating the total emissions (>80%), the general emission composition of a pine did not change much with drought (Supplementary Fig. 6a). However, drought decreased the total amount of emissions (by up to ∼30%, Supplementary Fig. 6b). The magnitude of the response of VOC emissions to drought was relatively insensitive compared with heat. We conclude that decreasing VOC emissions by drought should affect the CCN activity of SOA in the opposite way as heat, and the overall effect would be a smaller activated fraction and less cloud droplets.

Discussion

Biotic and abiotic stressors affect VOC emissions of plants and therefore the resulting SOA. Increased temperatures increase VOC emissions9,29 promoting particle growth leading to a higher number of particles larger than 100 nm, that is, higher fractions of CCN active particles in the boundary layer12,32,33,34. Biotic stresses enhances the SOA mass concentration16,17,18 and a model study assuming an increase of monoterpene emissions indicates higher aerosol and CCN concentrations in forests influenced by insect outbreaks17. The results, presented here for the first time, directly show how environmental conditions of plants can affect the CCN activity of biogenic SOA via the plants' emissions: biotic stresses by causing induced VOC emissions, modifying hygroscopicity, or abiotic stresses by changing the amount of constitutive VOC emissions, affecting particle size distribution.

Our findings provide important information on the potential impact of vegetation on the CCN activity of biogenic SOA, and thus on cloud properties. They are one puzzle piece for understanding the complex coupling between terrestrial plants and climate change. Climate change induces both long term, slow changes in the climate parameters such as global mean temperature change and short term episodic changes, such as heat and water shortage extremes. Plants can adapt to slow long-term climate changes to a varying extent via phenological changes, evolutionary and genetic changes and migration15. Plant species with long lifetime such as trees have limited capability to adapt15 and if climate zones move faster than vegetation zones, as currently observed15, more trees will experience stresses more often. Furthermore, with climate change, the frequency of unfavourable environmental conditions such as heat, droughts, and infestation are projected to increase in many regions3. Our study mainly considered mild abiotic stresses, excluding extreme heat waves and severe droughts. In this case, heat enhances the CCN activity of particles by forming larger SOA particles, which also scatter more solar radiation35. Insect infestation of plants is expected to become more prevalent since herbivorous insects survive better in warming climate15, adding to the fraction of forest being already affected by infestation at present16. These biotic stresses lead to induced VOC emissions which in case of sesquiterpenes decrease CCN activity. However, these changes in κ can be compensated by higher SOA yields of induced VOC18.

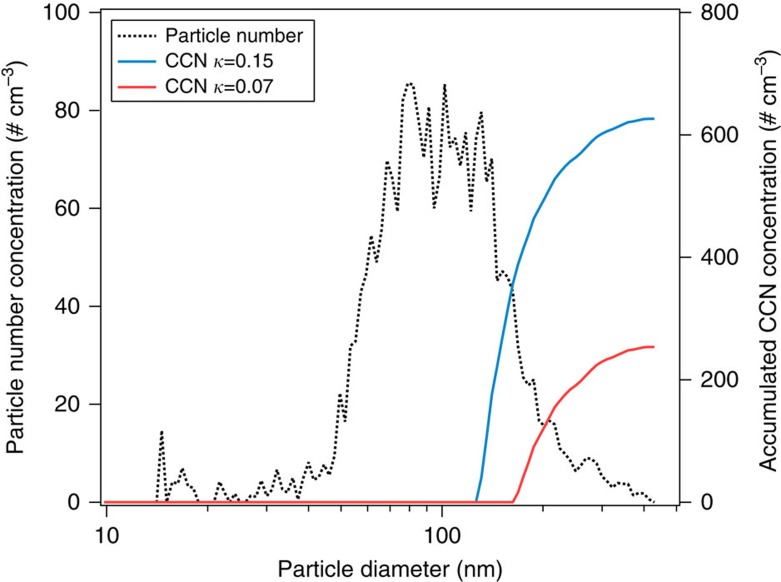

This study shows that environmental factors have an important impact on ambient CCN concentrations and properties of SOA. The effects of induced emissions should be considered in models that simulate the CCN concentrations and the impact on climate. Neglecting such effects can lead to significant biases. For example, models often simulate the CCN concentrations assuming a constant κ value of ∼0.1 for all organic aerosols regardless of the source. However, a study showed that a change of κ of SOA by 50% (from 0.14 to 0.07 and 0.21) affects the CCN number concentration by ∼40% (ref. 36). To demonstrate the potential effect of κ change obtained here, we applied a decrease of κ due to biotic stresses to a typical particle size distribution dominated by organic components as observed over a boreal forest in Finland as shown in Fig. 4. Our calculations show that if the plant emissions were dominated by sesquiterpenes instead of monoterpenes, the CCN number concentration would reduce by ∼60% at 0.2% supersaturation. This suggests that biotic stresses can have significant influence on the CCN concentration in areas where biogenic SOA components dominate the particle composition. Currently, there are no direct field measurements reporting the effects of biotic stress on the CCN activity of biogenic SOA and CCN number concentrations, to our knowledge. Future field measurements of CCN in periods when biotic stresses induced emissions are dominant will help to assess the impact of biotic stresses on CCN activity and concentration.

Figure 4. Impact of hygroscopicity parameter κ changes on cloud condensation nuclei concentrations.

Measured ambient particle number size distribution (black dotted line, left axis) and the derived accumulated cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) number size distribution (right axis) are shown. The particle size distribution was measured in a boreal forest near Jämijärvi, Finland in May 2013 at a period when organics dominated the total aerosol mass (>80%). The CCN concentration was obtained considering 0.2% supersaturation, a typical supersaturation in clouds, using κ of 0.15 (blue line) and 0.07 (red line) corresponding to the value for SOA from monoterpene-dominated and sesquiterpene-dominated emissions obtained in our plant chamber study shown above. Note the log x axis.

The specific impacts on the ambient CCN number concentration and cloud formation depends on parameters such as ambient particle size distribution, aerosol composition, mixing state and supersaturation in clouds. Moreover, more biotic and abiotic stressors than discussed here may affect plants' emissions8,37 and thus the composition and CCN activity of SOA. For example, mechanical stress due to a passing storm can induce higher monoterpene emissions from pine38,39, which should affect CCN activity similar to heat but in a more quick and episodic way. We investigated young boreal tree species. It is possible that different plant species with different ages may exhibit different responses in VOC emissions to stresses and thus further change SOA composition and properties. For example, simulated herbivory on different tree species has been shown to cause different responses in VOC emissions, which alters the SOA composition with some variability40,41. Because various plant species with different ages as well as various environmental factors are involved and multiple factors can have synergistic or counteracting effects, the overall impacts are complex and cannot be assessed quantitatively here. Nevertheless, we provide a general scheme derived from our findings of the effects of biotic stresses, heat and drought on particle size, κ and CCN number concentrations in Supplementary Fig. 7. Our results show the potential importance of induced emissions for SOA acting as CCN. Here for the constitutive emissions, heat and drought cause a 27% increase or a 37% decrease in the CCN number concentration, respectively. The biotic stress alone caused a 47% increase while biotic stress plus heat caused a 93% increase in the CCN number concentration compared with the reference case of constitutive emissions at room temperature (right lower white dot in Supplementary Fig. 7). Despite the complexity, the effects of various stresses, especially understudied biotic stresses, should be further investigated in laboratory and field studies as well as integrated into comprehensive models to better represent the feedbacks between terrestrial plants and climate.

Methods

Experimental setup and procedure

The experiments were conducted in the Jülich Plant Atmosphere Chamber (JPAC). VOC emitted from boreal forest trees (pine (Pinus sylvestris L.), spruce (Picea abies L.), and birch (Betula pendula L.)) in a plant chamber were fed into a separate reaction chamber and were degraded by photooxidation to form SOA via homogeneous nucleation. JPAC was optimized to generate and investigate SOA by oxidation of VOC emissions from plants. The setup used here has been described in details by Mentel et al19. and was used previously to study SOA formation and properties18,19,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. A schematic representation of the setup is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

JPAC consists of three large glass chambers (0.164, 1.150, and 1.450 m3), each in a separate temperature-controlled housing and operated as a continuously stirred tank reactor. The 1.450 m3 chamber served as reaction chamber (RC), while the smaller chambers were used to host the plants, denoted as plant chambers (PC, PC1 for the 1.150 m3 chamber and PC2 for 0.164 m3 chamber). VOC emitted from trees in a plant chamber were fed into the reaction chamber and were degraded by photooxidation to form SOA via homogeneous nucleation. The PC were illuminated with discharge lamps (HQI 400 W/D; Osram, Munich, Germany), which simulate the solar spectrum reaching photosynthetic photon flux densities (PPFD) of up to 480 μmol m−2 s−1 (PC1) and 700 μmol m−2 s−1 (PC2) at full illumination. Switching on and off these visible-light lamps provided a day-night cycle for the plants. Purified air, which was free of particles, VOC, NOx, and ozone with around 350 ppm CO2 added, flowed through the PC and transferred the VOC emitted by the plants to the RC. Besides the flow from the PC, two additional air streams supplied the RC with ozone (≈90 ppb) and water vapor. By controlling the humidity in this air stream, the relative humidity (RH) in the RC was held at constant 65% at constant RC temperature of 17 °C. The residence time of the chambers were ∼20 min in the PC1, 5–8 min in the PC2 and approximately 65 min in the RC. Inside the RC, a UV lamp (Philips, TUV 40W, λmax= 254 nm) was switched on for certain periods to produce OH radicals from ozone photolysis and the subsequent reaction of O (1D) radicals with water vapor. In the RC, OH concentrations depended on the introduced VOC amount since O3, H2O and UV intensity, and thus OH production, were kept constant. OH concentrations, derived from an OH tracer (deuterated cyclohexane-d10), typically ranged 2 × 107–6.5 × 107 molecules per cm3. This range is about an order of magnitude higher than that observed in the atmosphere in boreal regions during summer49.

The experiments were conducted by applying the following cycle: first the visible light in the PC was turned on to initiate the diurnal cycle as described below. We waited until the RC reached a steady-state regarding VOC concentrations. The steady state also included the ozonolysis reactions of VOC since ozone was constantly added into the RC. After reaching the steady state, the UV lamp in the RC was switched on to generate OH radicals and to induce photochemical particle formation. Formation of particles was only observed when the UV lamp was switched on and OH radicals were produced, as observed previously19. Experiment start is defined as the time when the UV lamp was switched on.

In this study, a mixed seedling stand of two pines (Pinus sylvestris L.), one spruce (Picea abies L.), and one birch (Betula pendula L.) (3–4 years old, about 1.1–1.3 m high) was housed in the PC1. These trees are mainly monoterpene emitters under unstressed conditions19. They were stored outdoor under natural conditions in the Forschungszentrum Jülich campus located near a forest. These trees were found to be infested by aphids, although we could not differentiate the exact species. They were only slightly infested and visual check only showed very slight defoliation and foliage discolouration without any significant damages. Such insect infestation is a part of the natural conditions that plants are facing. The aphid infestation was consistent with the high sesquiterpene emissions8,9,37 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Similar sesquiterpene dominated emission composition was observed reproducibly for different types of boreal trees on different individuals (pine, spruce and birch) and in different years. Therefore, such emission composition represents one typical emission composition when trees are under insect infestation. Regular forest inspections reveal that insect infestation is common to about 10% of boreal trees14,16,50.

To simulate the diurnal cycle for the trees, at 02:00 UTC the lamps were turned on sequentially creating an artificial dawn of 1 h. After 15 h of full illumination, the lamps were turned off in the reverse fashion. This led to a dark period of 7 h for the plants. The temperature in the PC was varied between 22 and 34 °C to investigate effects of temperature on VOC emission strength and composition, especially mild heat conditions51. After setting a new temperature in the PC, the plants had 8–18 h to adjust to the new conditions. In addition, two experiments were conducted in which the lamps in the PC remained off during the day and mainly VOC out of storage pools of the plants were emitted9. For these emissions, fractions of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes were between those of monoterpene-dominated and sesquiterpene-dominated cases (denotes as ‘intermediate' case) because light dependent sesquiterpene emissions decreased more than monoterpene emissions in the dark. All other experimental conditions except otherwise mentioned were kept the same to make the experiments comparable.

Trees in absence of biotic stress were studied in another series of experiments. A stand of eight pine trees situated in the PC1, a single spruce and a single birch situated in the PC2 were investigated separately for VOC emissions (Supplementary Fig. 2) and particle formation19. By raising the plant temperature, VOC emissions were increased and the CCN activity of particles produced from these tree emissions were investigated. In this series of experiments, the CCN data from the experiments with spruce and birch emissions are limited because particle sizes were small and particle numbers were low for CCN activity studies due to low VOC concentrations. Therefore mainly CCN data from pine are discussed. Similar to the stressed trees case, the temperature in the PC was varied between 20 and 35 °C to investigate effects of mild heat.

In addition, to investigate the effects of drought on pine VOC emissions, a single pine tree (unstressed) was placed in the PC2 and watering was stopped and restarted in the same way as described by Wu et al52. Briefly, in these experiments, a three to four year old Scots pine was exposed to a diurnal rhythm of 11 h illumination (06:00–17:00) and 11 h darkness, and a simulation of twilight of 1 h each in the morning and evening, respectively. The pine was exposed to several drought/watering cycles. The emission rates at the stable period during the day were used. Heat and drought are used as two examples of the various abiotic factors affecting plant VOC emissions37,39,53,54,55,56,57.

Instrumentation

The VOC were monitored with two Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS, Agilent) systems and with a Proton Transfer Reaction—Mass Spectrometer (PTR-MS, Ionicon) with the details described in Mentel et al19. and Kleist et al9. Briefly, GC-MS systems measured VOC at the outlet of the PC. One GC-MS system was optimized to measure VOC from C5 to C20 including isoprene, monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes as well as compounds from lipoxygenase activity (LOX products) or phenolic compounds such as methyl salicylate58. The second GC-MS system was optimized to measure short chained oxygenated VOC from methanol up to C10 compounds59. Calibration of both systems was conducted as described by Heiden et al60. The PTR-MS was used to determine the concentrations of VOC and oxidation products at a time resolution of 10 min and was switched continuously between the outlet of the PC and the outlet of the RC.

The number concentration and size distributions of particles were measured with an Ultrafine Condensation Particle Counter (CPC, TSI, Model 3025A) and a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS, TSI, Model DMA 3071 and CPC 3022A).

VOC emission composition and related SOA composition

Induced VOC emissions are de-novo emissions, that is, they are directly coupled to photosynthetic activity of the plants. Although VOC induced by stress depend on tree species and specific stressors, there are mainly three groups of compounds based on their biosynthesis pathways: terpenoids (such as monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes), C6 lipoxygenase (LOX) products (also known as green leaf volatiles) and aromatic products of the shikimate pathway (for example, methyl salicylate (MeSA))2. Constitutive terpenoid emissions are also of de novo type. In case plants have storage pools (for example, resin ducts), they are able to store some compounds like monoterpenes. Compounds from pools are emitted by physical diffusion governed by the plant temperature. Because monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes are dominant components in the VOC emissions of this study, which together typically account for more than 90% of the total VOC emissions, the VOC are classified as three classes: monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and others (including LOX products, oxygenated VOC, aromatic compounds, isoprene and so on). We use the notation ‘emission composition' to refer to the relative contributions of different emission classes (monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and others) in total VOC emissions.

On the basis of the particle yield data of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes from plant emissions in our previous studies18,19 (17% for sesquiterpenes and 5% for monoterpenes), the relative fraction of SOA components from monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes oxidation could be roughly estimated from the VOC emission composition. For example, assuming the total SOA mass can be predicted by a linear combination of SOA yields from each precursor, the mass ratio of the SOA components from monoterpenes to the SOA components from sesquiterpenes in the ‘Intermediate' case in Fig. 2 is around 0.8.

Droplet activation measurement

The number concentration of activated particles was measured with a Cloud Condensation Nuclei Counter (CCNC, Droplet Measurement Technologies, CCN-100) for supersaturations (SS=RH-100%) between 0.17 and 1.1% with the setup described previously61. In parallel, the particle size distribution (15.1–399.5 nm) and total number concentration were measured with a SMPS system (TSI Model 3071 and CPC 3022A) and a water-based CPC (TSI, Model 3785), respectively. Before entering the instruments, the poly-dispersed aerosol was dried with a silica gel diffusion drier to RH <5% and then neutralized with a Kr-85 neutralizer (TSI Model 3077).

The activated fraction was calculated as the ratio of the number concentration of activated particles to the total particle number concentration. The calculated activated fraction was compared with the cumulative size distribution starting from the maximum diameter. The size, at which the cumulative particle size distribution was equal to the activated fraction, was defined as dry critical activation diameter (Dcrit). It was assumed that the aerosol particles were internally mixed. This approach is applicable to the period when the nucleation already stopped i.e., we measured the CCN activity at the period when the conditions in the RC reached the steady state. Five different SS were set in the CCNC: the first step for 20 min, the others for 10 min each. To ensure stable conditions in the CCNC, only data from the last 6 min of each SS step were used to determine Dcrit, which overlapped with three SMPS scans each lasting 2 min. For each set of SS, the Dcrit values derived from three size scans were averaged. The contribution of multiple charged particles was corrected with the measured size distribution assuming a natural charge distribution. Ammonium sulfate aerosol was used to calibrate the SS of the CCNC based on data sets in the literature62 (OS1 data set therein).

From the Dcrit and SS data, the hygroscopicity parameter κ was determined using the method in Petters and Kreidenweis20. Petters and Kreidenweis20 developed a theory to parameterize CCN activity data using κ based on Köhler theory63. κ is a measure of the hygroscopicity of particles, which is defined in the following equation:

|

aw, Vs and Vw are the water activity, volume of solute and volume of water in an activated droplet, respectively.

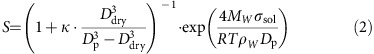

The following equation can be derived by using equation (1) in the original κ-Köhler theory.

|

S: saturation ratio, S=SS+1;

Dp: droplet diameter;

Ddry: dry particle diameter;

Mw: molecular weight of water;

σsol: surface tension of droplet solution;

ρw: density of water.

R: gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1)

T: temperature.

σsol is assumed to be equal to that of water. Although organics can partition to the droplet surface, using the surface tension of water to calculate κ is a reasonable assumption for droplet at activation64,65.

Comparing the κ definition in the κ-Köhler theory to other parameterizations of water activity (namely van't Hoff factor approach) yields20,

|

where ρs and ρw are the density of solute and water, and Ms and Mw are the molecular weight of solute and water, respectively. i is the van't Hoff factor. It is the actual number of molecules or ions produced per solute molecule when a substance is dissolved66,67,68. Since most organics do not dissociate, i is close to 1. The variability of density of most organics in SOA is small and can be assumed to be constant. equation (3) shows that κ is inversely proportional to the molecular weight of solute assuming other factors are relatively constant.

κ of SOA formed from the photooxidation of VOC emitted by unstressed trees and stressed trees were compared using t-test. κ of SOA formed at different plant temperature were also compared.

Ambient particle measurement

The ambient particle size distribution and chemical composition were measured in a boreal forest near Jämijärvi, Finland in May and June of 2013 during the PEGASOS (Pan-European Gas-AeroSOl-climate interaction Study) Finland campaign using instruments on board a Zeppelin-NT airship. The particle number and size distribution were measured using a CPC (TSI, model 3786) and SMPS (TSI, DMA 3081 and CPC 3786). The particle chemical composition was measured using a High-Resolution Time-of-Flight Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS, Aerodyne Research Inc.69) adapted to airship measurement70. The measured particle size distribution was used to derive the CCN number concentrations. The activation diameter (Dcrit) was obtained at 0.2% supersaturation. In the calculation of CCN number concentration, the activation fraction was set to 0, 0.5 and 1, respectively, if Dcrit was above, within and below a size bin of SMPS.

Modelling of the effects of stresses on CCN concentrations

The effects of various biotic stress, heat and drought on and κ and particle size, thus on CCN number concentration were conceptually modelled based on the results in this study as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. The CCN number concentration was derived at 0.2% supersaturation using a typical particle size distribution in the boreal forest in Finland (cf. Fig. 4).

While for the SOA from constitutive emissions, heat and drought have little effect on κ, heat increases particle size and drought decreases particle size due to their effects on VOC emission strengths. Similarly, for SOA from induced emissions, heat also increases particle size while having little effect on κ. The particle size changes due to heat were calculated using SOA mass changes corresponding to the exponential changes of VOC emissions with temperature as derived from Fig. 3. A temperature increase of 3.7 °C (a global mean temperature in 2100 projected by IPCC report 2013 (ref. 3)) was used here. The particle size change due to drought was calculated using the SOA mass change corresponding to the total VOC changes in Supplementary Fig. 6. A cubic relationship between the particle mass and diameter was assumed in the calculations of the effects of these environmental factors on particle size. The effect of particle size (shown as median diameter) on CCN number concentration was obtained by shifting the size distribution in constant logarithmical diameter steps.

Induced emissions decrease κ while increasing particle size due to the higher SOA yield of sesquiterpenes compared with monoterpenes18. The particle size change due to biotic stress induced emissions was calculated using the SOA mass corresponding to the SOA yields of sesquiterpene-dominated emissions (17%)18 and monoterpene-dominated emissions (5%) and assuming the same total VOC emissions (ppbC).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zhao, D. F. et al. Environmental conditions regulate the impact of plants on cloud formation. Nat. Commun. 8, 14067 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14067 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank the funding support from the EUROCHAMP2 and PEGASOS under EC 7th framework. We thank the support of PEGASOS Zeppelin 2013 campaign team.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions D.F.Z., A.B. and T.F.M. wrote the manuscript. T.F.M., A.K.S. and J.W. organized and designed the laboratory experiments. T.F.M. organized the PEGASOS Zeppelin Campaign. D.F.Z., A.B., R.T., E.K., C.W., J.W., T.F.M. conducted the laboratory data collection and analysis. D.F.Z, R.T., F.R. conducted ambient data collection and analysis. D.F.Z., A.B., A.K.-S., Y.R., J.W., T.F.M. edited the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

References

- Guenther A. B. et al. The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): an extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 1471–1492 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen J. K. & Blande J. D. Where do herbivore-induced plant volatiles go? Front. Plant Sci. 4, 185 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist M. et al. The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: current and emerging issues. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 5155–5236 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Tröstl J. et al. The role of low-volatility organic compounds in initial particle growth in the atmosphere. Nature 533, 527–531 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkby J. et al. Ion-induced nucleation of pure biogenic particles. Nature 533, 521–526 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae M. O. & Rosenfeld D. Aerosol-cloud-precipitation interactions. Part 1. The nature and sources of cloud-active aerosols. Earth Sci. Rev. 89, 13–41 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Penuelas J. & Staudt M. BVOCs and global change. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 133–144 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleist E. et al. Irreversible impacts of heat on the emissions of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, phenolic BVOC and green leaf volatiles from several tree species. Biogeosciences 9, 5111–5123 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Amin H. et al. Effect of Bark Beetle Infestation on Secondary Organic Aerosol Precursor Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 5696–5703 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer D. K., Cappa C. D. & Kreidenweis S. M. Atmospheric processes and their controlling influence on cloud condensation nuclei activity. Chem. Rev. 115, 4199–4217 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasonen P. et al. Warming-induced increase in aerosol number concentration likely to moderate climate change. Nat. Geosci. 6, 438–442 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Arneth A. et al. Terrestrial biogeochemical feedbacks in the climate system. Nat. Geosci. 3, 525–532 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Seidling W. et al. in Forest Condition in Europe: 2015 Technical Report of ICP Forests. Report under the UNECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP) eds Michel A., Seidling W. Ch. 3, BFW Austrian Research Centre for Forests (2015). [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom R., Hallquist M., Simpson D., Wildt J. & Mentel T. F. Biotic stress: a significant contributor to organic aerosol in Europe? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 13643–13660 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Joutsensaari J. et al. Biotic stress accelerates formation of climate-relevant aerosols in boreal forests. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 12139–12157 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Mentel T. F. et al. Secondary aerosol formation from stress-induced biogenic emissions and possible climate feedbacks. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8755–8770 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Mentel T. F. et al. Photochemical production of aerosols from real plant emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 4387–4406 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Petters M. D. & Kreidenweis S. M. A single parameter representation of hygroscopic growth and cloud condensation nucleus activity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 1961–1971 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Alfarra M. R. et al. The effect of photochemical ageing and initial precursor concentration on the composition and hygroscopic properties of beta-caryophyllene secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 6417–6436 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. Z., Cocker D. R., Griffin R. J., Flagan R. C. & Seinfeld J. H. Gas-phase ozone oxidation of monoterpenes: gaseous and particulate products. J. Atmos. Chem. 34, 207–258 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Jaoui M., Leungsakul S. & Kamens R. M. Gas and particle products distribution from the reaction of beta-caryophyllene with ozone. J. Atmos. Chem. 45, 261–287 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D. F. et al. Cloud condensation nuclei activity, droplet growth kinetics, and hygroscopicity of biogenic and anthropogenic secondary organic aerosol (SOA). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 1105–1121 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Asa-Awuku A., Engelhart G. J., Lee B. H., Pandis S. N. & Nenes A. Relating CCN activity, volatility, and droplet growth kinetics of beta-caryophyllene secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 795–812 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Frosch M. et al. CCN activity and volatility of beta-caryophyllene secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2283–2297 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Duplissy J. et al. Cloud forming potential of secondary organic aerosol under near atmospheric conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L03818 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Massoli P. et al. Relationship between aerosol oxidation level and hygroscopic properties of laboratory generated secondary organic aerosol (SOA) particles. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L24801 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Guenther A. B., Zimmerman P. R., Harley P. C., Monson R. K. & Fall R. Isoprene and monoterpene emission rate variability—model evaluations and sensitivity analyses. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 98, 12609–12617 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- McFiggans G. et al. The effect of physical and chemical aerosol properties on warm cloud droplet activation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 2593–2649 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen J. K. & Gershenzon J. Multiple stress factors and the emission of plant VOCs. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 176–184 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaitch W. R. et al. Temperature response of the submicron organic aerosol from temperate forests. Atmos. Environ. 45, 6696–6704 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Liao L., Kerminen V. M., Boy M., Kulmala M. & Dal Maso M. Temperature influence on the natural aerosol budget over boreal forests. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 8295–8308 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Kourtchev I. et al. Enhanced volatile organic compounds emissions and organic aerosol mass increase the oligomer content of atmospheric aerosols. Sci. Rep. 6, 35038 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moise T., Flores J. M. & Rudich Y. Optical properties of secondary organic aerosols and their changes by chemical processes. Chem. Rev. 115, 4400–4439 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. & Wang J. How important is organic aerosol hygroscopicity to aerosol indirect forcing? Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 044010 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F. & Schnitzler J.-P. Abiotic stresses and induced BVOCs. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 154–166 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase K. B. et al. Changes in monoterpene mixing ratios during summer storms in rural New Hampshire (USA). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 11465–11476 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Schade G. W. & Goldstein A. H. Increase of monoterpene emissions from a pine plantation as a result of mechanical disturbances. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1380 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Faiola C. L., Jobson B. T. & VanReken T. M. Impacts of simulated herbivory on volatile organic compound emission profiles from coniferous plants. Biogeosciences 12, 527–547 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Faiola C. L., Wen M. & VanReken T. M. Chemical characterization of biogenic secondary organic aerosol generated from plant emissions under baseline and stressed conditions: inter- and intra-species variability for six coniferous species. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 3629–3646 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Kiendler-Scharr A. et al. New particle formation in forests inhibited by isoprene emissions. Nature 461, 381–384 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiendler-Scharr A. et al. Aerosol mass spectrometric features of biogenic SOA: observations from a plant chamber and in rural atmospheric environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 8166–8172 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang-Yona N. et al. The chemical and microphysical properties of secondary organic aerosols from Holm Oak emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 7253–7265 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Kiendler-Scharr A. et al. Isoprene in poplar emissions: effects on new particle formation and OH concentrations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 1021–1030 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wildt J. et al. Suppression of new particle formation from monoterpene oxidation by NOx. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 2789–2804 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Ehn M. et al. A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol. Nature 506, 476–479 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D. F. et al. Size-dependent hygroscopicity parameter (κ) and chemical composition of secondary organic cloud condensation nuclei. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10920–10928 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Petaja T. et al. Sulfuric acid and OH concentrations in a boreal forest site. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 7435–7448 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Nevalainen S., Lindgren M. & Pouttu A. in Forest condition monitoring in Finland – National report 2002–2005. Metlan työraportteja/Working Papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute 45 eds Merilä P., Kilponen T., Derome J. Ch. 2.2, Finnish Forest Research Institute (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Tatarinov F. et al. Resilience to seasonal heat wave episodes in a Mediterranean pine forest. New Phytol. 210, 485–496 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. et al. Impacts of soil moisture on de novo monoterpene emissions from European beech, Holm oak, Scots pine, and Norway spruce. Biogeosciences 12, 177–191 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Kaser L. et al. Undisturbed and disturbed above canopy ponderosa pine emissions: PTR-TOF-MS measurements and MEGAN 2.1 model results. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 11935–11947 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kim L., Galbally I. E., Porter N., Weeks I. A. & Lawson S. J. BVOC emissions from mechanical wounding of leaves and branches of Eucalyptus sideroxylon (red ironbark). J. Atmos. Chem. 68, 265–279 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F., Pinelli P., Manes F. & Kollist H. Impact of ozone on monoterpene emissions and evidence for an isoprene-like antioxidant action of monoterpenes emitted by Quercus ilex leaves. Tree Physiol. 24, 361–367 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiiva P. et al. Isoprene emission from a subarctic peatland under enhanced UV-B radiation. New Phytol. 176, 346–355 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapparini F., Baraldi R., Miglietta F. & Loreto F. Isoprenoid emission in trees of Quercus pubescens and Quercus ilex with lifetime exposure to naturally high CO2 environment. Plant Cell Environ. 27, 381–391 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Heiden A. C. et al. Emission of volatile organic compounds from ozone-exposed plants. Ecol. Appl. 9, 1160–1167 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Folkers A. Sauerstoffhaltige fluechtige organische Verbindungen in der Troposphaere: Entwicklung und Anwendung einer gaschromatographischen Nachweismethode Ph. D. thesis University of Cologne (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Heiden A. C., Kobel K., Langebartels C., Schuh-Thomas G. & Wildt J. Emissions of oxygenated volatile organic compounds from plants—part I: Emissions from lipoxygenase activity. J. Atmos. Chem. 45, 143–172 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz A. Secondary organic aerosols: chemical aging, hygroscopicity, and cloud droplet activation Ph.D. thesis University of Cologne (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Rose D. et al. Calibration and measurement uncertainties of a continuous-flow cloud condensation nuclei counter (DMT-CCNC): CCN activation of ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride aerosol particles in theory and experiment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 1153–1179 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Koehler H. The nucleus in and the growth of hygroscopic droplets. Transact. Faraday Soc. 32, 1152–1161 (1936). [Google Scholar]

- Prisle N. L., Dal Maso M. & Kokkola H. A simple representation of surface active organic aerosol in cloud droplet formation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 4073–4083 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ruehl C. R., Davies J. F. & Wilson K. R. An interfacial mechanism for cloud droplet formation on organic aerosols. Science 351, 1447–1450 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrucci H. & Herring M. General Chemistry, Principles & Modern Applications 9th edn Pearson Education, Inc. (2007). [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. E. Erroneous cloud-physics applications of Raoult's law. J. Meteorol. 10, 68–70 (1953). [Google Scholar]

- Low R. D. H. A generalized equation for the solution effect in droplet growth. J. Atmos. Sci. 26, 608–611 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- DeCarlo P. F. et al. Field-deployable, high-resolution, time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer. Anal. Chem. 78, 8281–8289 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubach F. Aerosol processes in the Planetary Boundary Layer: High resolution Aerosol Mass Spectrometry on a Zeppelin NT Airship PhD thesis Wuppertal University (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables and Supplementary References

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.