Abstract

Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (Brd4) is a cellular chromatin-binding factor and transcriptional regulator that recruits sequence-specific transcription factors and chromatin modulators to control target gene transcription. Papillomaviruses (PVs) have evolved to hijack Brd4’s activity in order to create a facilitating environment for the viral life cycle. Brd4, in association with the major viral regulatory protein E2, is involved in multiple steps of the PV life cycle including replication initiation, viral gene transcription, and viral genome segregation and maintenance. Phosphorylation of Brd4, regulated by casein kinase II (CK2) and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), is critical for viral gene transcription as well as E1- and E2-dependent origin replication. Thus, pharmacological agents regulating Brd4 phosphorylation and inhibitors blocking phospho-Brd4 functions are promising candidates for therapeutic intervention in treating human papillomavirus (HPV) infections as well as associated disease.

Keywords: Brd4, Papillomavirus life cycle, E2 protein, Papillomavirus replication, Papillomavirus transcription

1. Introduction

Papillomaviruses (PVs) are a large group of more than 300 viruses (https://pave.niaid.nih.gov; Van Doorslaer et al., 2013) that contain a double-stranded (ds) DNA genome of approximately 8 kb in size (Fig. 1). Except for a few cases, each PV specifically infects a certain host species and clinical outcomes range from persistent asymptomatic infections to tumor formation. A subset of the alpha genus of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) – termed high-risk HPV – are the etiologic agent of cervical cancer and have also been found in epithelial tumors of the oropharynx and the remaining anogenital area besides the cervix (Haedicke and Iftner, 2013).

Fig. 1.

Human papillomavirus genome and its transcription in relation to high-risk or low-risk HPV types. The papillomavirus genome contains approximately 8000 bp and encodes 7–10 open reading frames (ORFs). The viral E2 protein functions as a transcriptional activator or a repressor depending on the location and sequence context of the E2 binding sites in relation to the TATA box. URR: upstream regulatory region; E2BS: E2-binding site.

One major regulator of the PV life cycle is the viral early protein 2 (E2), which is a dimeric, sequence-specific DNA binding protein that functions primarily as a transcription factor acting either as a repressor or activator depending on the location of the E2 binding sites (E2BS) in relation to the early PV promoter (Fig. 1) (McBride, 2013; Rapp et al., 1997). E2 is also involved in the replication of the viral genome (McBride, 2013). In the case of beta- and kappa-HPV, which infect the skin outside the anogenital region, E2 also appears to have oncogenic activities (Howley and Pfister, 2015).

Full-length E2 protein consists of an N-terminal transactivation/transrepression domain and a C-terminal DNA-binding domain, which is also the site of dimerization. These two domains are linked by the hinge region, whose length and sequence varies considerably between PV genera (Fig. 2). The amino-terminal domain is required for the activation of replication, modulation of transcription and attachment of PV genomes to mitotic chromosomes. These functions are mediated by interactions with the viral E1 protein as well as host proteins, which bind to highly conserved amino acid residues within the N-terminal domain of E2 (McBride, 2013). One of the best-characterized interactors of E2 is the bromodomain-containing protein 4 (Brd4), which is a member of the bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) protein family (Wu and Chiang, 2007). As a scaffold protein, Brd4 recruits a variety of transcription factors and chromatin regulators to control transcription (Rahman et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2013). Among the best characterized factors recruited by Brd4 are positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb), general cofactor Mediator, and transcriptional regulators such as NFκB, p53 and PV E2 (Chiang, 2009).

Fig. 2.

Papillomavirus E2 protein domains and functions. The crystal structures have been obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB; http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/; Berman et al., 2000). The crystal structure of the transactivation domain is a representation of HPV16 E2 in complex with Brd4 (PDB 2NNU; Abbate et al., 2006). The C-terminal domain of Brd4, which interacts with the E2 N-terminal domain, is highlighted in purple. The crystal structure of the DNA-binding/dimerization domain shows a dimer of the C-terminus of HPV18 E2 bound to double-stranded DNA, which is shown in green (PDB 1JJ4; Kim et al., 2000). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Brd4 is known to influence transcription by direct and indirect mechanisms leading to the phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) (Devaiah et al., 2016b). For this, it recruits transcription initiation and elongation factors including Mediator and P-TEFb as well as Top I, which in turn stimulates transcription by releasing pausing of Pol II at the promoter-proximal region (McBride and Jang, 2013). E2 competes with P-TEFb binding at the extreme C-terminus of Brd4 thereby partly causing repression of the early HPV promoter (Yan et al., 2010). Association of HPV E2 to specific E2 binding sites (E2BS) in close proximity to the HPV promoter prevents recruitment of core promoter-binding transcription factor II D (TFIID) and subsequent Pol II preinitiation complex assembly (Hou et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2006), which is another way of repressing viral transcription (Fig. 1). In contrast, the recently discovered intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity of Brd4, which causes acetylation of the N-terminal tails of histones H3K14, H4K5 and H4K12, and at the C-terminal globular domain of H3K122, leads to nucleosome eviction and chromatin decompaction as well as instability resulting in strong transcriptional activation of target genes (Devaiah et al., 2016a).

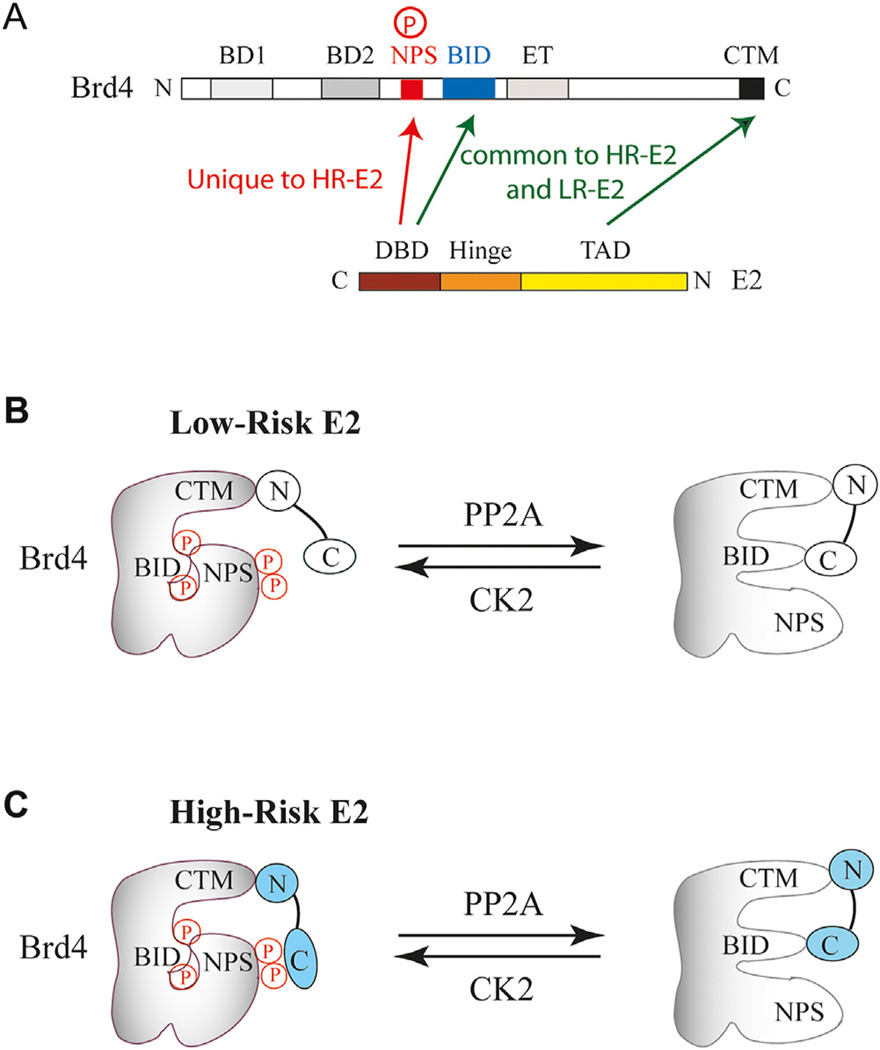

Brd4 binding to E2 prevents degradation of E2, modulates E2-mediated transcription and anchors E2 and a number of PV genomes to the host chromosome during mitosis to prevent loss of viral genomes (McBride and Jang, 2013). Recently, E2 of high-risk (HR) and low-risk (LR) HPVs were shown to interact differently with phosphorylated Brd4 (Wu et al., 2016). While the C-terminal motif (CTM) and a basic residue-enriched interaction domain (BID) of Brd4 are used for contacting HR and LR E2 proteins, the N-terminal phosphorylation sites (NPS) of Brd4 are uniquely recognized by HR-E2 (Fig. 3A). Phospho-NPS and BID interact independently with the DNA-binding domain of E2, and CTM contacts specifically the transactivation domain (TAD) of E2. The intramolecular contact between BID and NPS, depending on the extent of BRD4 phosphorylation regulated by casein kinase II (CK2) and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), dictates specific Brd4 domains available for E2 interaction (Fig. 3B and C). This phospho-switch mechanism also controls the ability of Brd4 binding to acetylated chromatin and recruitment of critical cellular transcription factors, such as p53, AP-1 and NFκB, to modulate viral and cellular transcription programs (Wu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2016).

Fig. 3.

Domain contact and model for Brd4 interaction with high-risk and low-risk E2. (A) Domain interactions between Brd4 and E2. Bromodomain I (BD1), bromodomain II (BD2), N-terminal phosphorylation sites (NPS), basic residue-enriched interaction domain (BID), extra-terminal domain (ET), and C-terminal motif (CTM) in Brd4 are shown from the N-terminus (N) on the left to the C-terminus (C) on the right, whereas DNA-binding domain (DBD), hinge region, and the transactivation domain (TAD) of high-risk (HR) or low-risk (LR) E2 are depicted from C to N. (B) Model for BRD4 domain interaction with low-risk E2 regulated by CK2 and PP2A. (C) Model for BRD4 domain interaction with high-risk E2 regulated by CK2 and PP2A.

2. Role of Brd4 in viral genome replication, segregation, maintenance and DNA damage response

PVs generally infect keratinocytes within the basal layer of stratified epithelia by gaining access through microwounds allowing the attachment of the viral particles to the basal lamina within the skin and mucosa. After infection, the HPV genome is present in the form of chromatinized DNA and replicates as a minichromosome with 10–100 copies per cell in undifferentiated basal-like keratinocytes (Stubenrauch and Laimins, 1999). The copy numbers are kept constant by a control mechanism that is not yet fully understood (Kadaja et al., 2009). Upon differentiation of the host cell, viral genomes amplify to several thousand copies, consequently resulting in infectious virus production (Stubenrauch and Laimins, 1999).

The viral proteins E1 and E2 function as sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins and are involved in the initiation of DNA replication, control of viral transcription, and segregation of viral genomes (Bergvall et al., 2013; McBride, 2013). The mechanisms by which viral genomes are segregated correspond to the phylogeny of PVs (McBride and Jang, 2013; Oliveira et al., 2006). Alpha-PV E2 proteins show a weak to undetectable binding to Brd4 and do not stabilize the association of Brd4 with host chromatin, leading to a low detection rate on mitotic chromosomes (Donaldson et al., 2007; Jang et al., 2014; Oliveira et al., 2006). On the other hand, E2 proteins from beta-PV strongly associate with mitotic chromosomes in close proximity to the centromere in regions of the ribosomal RNA genes (Jang et al., 2014; Oliveira et al., 2006; Poddar et al., 2009). The E2 domains required are different from those necessary for E2-Brd4 interaction and involve the DNA-binding domain and a peptide within the hinge region that has been shown to be necessary for chromatin interaction (Sekhar et al., 2010). The E2 proteins from a diverse group of PVs (delta, mu, kappa and others) strongly bind to Brd4 and thereby stabilize the association of Brd4 with interphase chromatin (Jang et al., 2014). The interaction of E2 and Brd4 is then visible as distinct dots on mitotic chromosomes (Oliveira et al., 2006).

The role of Brd4 in PV genome replication appears to be cell type- and context-dependent as shown by overexpression studies of viral proteins. In the absence of E1 or E2, or when each protein is expressed individually, Brd4 is localized in small dots throughout the nucleus. When E1 and E2 are co-expressed, Brd4 is reorganized to be concentrated in nuclear foci together with E1 and E2 (Sakakibara et al., 2013a). However, as soon as viral genome amplification starts, Brd4 is relocated to the periphery of the replication foci. This observation suggests that Brd4 plays a role in the switch from initial amplification to maintenance replication, but is not involved in the vegetative amplification of the viral genome in terminally differentiated cells (Sakakibara et al., 2013a). Evidence that Brd4 is indeed not required for the stable maintenance of PV genomes in cell lines was reported by Stubenrauch et al. in 1998, where the authors used a HPV31 genome with an E2 protein defective in Brd4 binding. This early finding was later confirmed by a number of different groups (see review by McBride and Jang, 2013).

Two publications investigating the requirement of Brd4 in genome replication came to contrasting conclusions (Sakakibara et al., 2013a; Wang et al., 2013). Wang et al. (2013) provided evidence that Brd4 was essential for genome replication as it forms replication foci together with E1, E2 and an artificial HPV16 origin-containing construct. The authors provide supportive data by mutagenesis disrupting the E2-Brd4 interaction, small RNA interference against Brd4 in a cell-free replication system, where replication could be rescued by recombinant Brd4 protein, and by using the BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1. Wang et al. (2013) concluded that Brd4 might have two independent functions: firstly in chromatin-associated transcriptional regulation and secondly in PV genome replication. Sakakibara et al. (2013a) on the other hand reported that combined expression of the homologous E1 protein together with E2 of oncogenic alpha-HPV type 16 leads to a tight association of E2 to regions of host chromatin enriched for Brd4. High-resolution 3D analysis showed that each of the potential replication foci consisted of a cluster of several E1, E2 and Brd4 spots where Brd4, however, did not fully overlap with regard to localization of E1 and E2 thereby contradicting an essential role of Brd4 for genome replication (Wang et al., 2013). Using different pre-extraction conditions with increasing salt concentrations, they were able to show that the E1 protein was resistant to salt extraction when expressed alone whereas the HPV16 E2 protein was not. However, when alpha PV E1 and E2 proteins were co-expressed, the E1–E2 complex was tightly bound to chromatin. This implies that the chromatin association is primarily mediated by the alpha-PV E1 protein and not by Brd4, which is in contrast to the assumption of Wang et al. (2013) that Brd4 is required for all steps of viral genome replication. Pre-extraction of keratinocytes with high-salt concentrations removed Brd4 from the nucleus in the presence or absence of E1 and E2. In addition, the PV genome origin stabilized the association of E1 and E2, but decreased the association of Brd4 with E1–E2 nuclear foci. Therefore, in the case of alpha PV, the E2-Brd4 interaction is different from the E2-Brd4 complex observed for non-alpha PV, which binds tightly to chromatin (Sakakibara et al., 2013a). Later, another group showed that phosphorylation of serine 243 of E2 allows binding of the HPV16 E2-Brd4 complex to chromosomal DNA (Chang et al., 2014).

As PVs only replicate in keratinocytes within lesions, it is notable that the mode of replication changes in differentiated cells in vitro, where PV genomes replicate using a DNA damage and repair response (DDR) – based recombination-directed replication mechanism indicated by incorporation of repair factors Rad51, RPA70, RFC1 (replication factor C1) and DNA polymerase delta into the replication foci (McBride and Jang, 2013; Sakakibara et al., 2013b). Sakakibara et al. (2013a) investigated in vitro replication foci in differentiated cells initially derived from a clinical lesion (9E cell line with full-length HPV31 genomes) which contain physiological levels of E1 and E2 as well as of all other viral proteins and a complete chromatinized HPV genome. Those foci showed similarities to the E1–E2-ori replication foci investigated with in vitro transfected cells.

The cellular ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) DDR pathway is necessary for productive replication of HPV genomes in differentiated cells (Moody and Laimins, 2009). For the induction of the ATM/ATR pathways and the formation of nuclear replication foci, the origin-specific binding and the ATP-dependent helicase function of the E1 protein are absolutely necessary (Sakakibara et al., 2011). The E2 protein itself does not induce DDR, but is required for the formation of nuclear foci. A role of Brd4 in DDR seems possible as shown by the interaction of a short isoform of Brd4 that plays a role in insulating chromatin from DDR signalling (Floyd et al., 2013) and also by the identification of the RFC – subunit ATAD5 protein that forms a complex with the Brd4-ET domain (Rahman et al., 2011) potentially helping release of the PCNA clamp loader from a replication fork (Kubota et al., 2013).

In summary, the current model assumes that after successful infection of a cell, Brd4 tethers the viral genome to active cellular chromatin to allow viral transcription and initiates together with the first translated E2 an extended wound healing response via c-Fos/AP-1 (see Section 3). After chromosome attachment, Brd4 recruits E1 and E2 to the viral genome and E1 excites a DDR response through its helicase activity. As viral genomes replicate and the foci grow larger, Brd4 seems to be no longer necessary for continuous replication of the genome and is displaced to the periphery of the growing foci. This implies that Brd4 is not directly involved in continuous replication, but supports the initial phase by binding to permissive regions of the nucleus. That allows amplification of PV genomes in terminally differentiated cells where controlled host DNA synthesis no longer takes place. The presence of Brd4 adjacent to the larger productive replication foci could mean that Brd4 might protect neighbouring cellular chromatin from the DDR signalling cascade initiated by E1 (Choi and Bakkenist, 2013; Floyd et al., 2013). The McBride group reported that the PV E2-Brd4 complex of HPV1 and HPV16 binds to fragile sites of the human genome in C-33A cells (Jang et al., 2014) and cervical cancers, which often contain integrated HPV genomes close to fragile sites (Smith et al., 1992). In fact, integration might result from the close association of replication foci with such fragile sites. It is possible that other regions of Brd4, such as BID and phospho-NPS, might interact with E2 to stabilize the complex in nuclear foci. A model can be delineated suggesting that in the early small E1–E2-Brd4 foci, E2 predominantly acts as a transcription factor regulating expression of not only early viral genes (Sakakibara et al., 2013a), but also cellular genes including the immediate early gene c-Fos (Delcuratolo et al., 2016). At later time points, when the foci begin to amplify viral genomes the acetylated chromatin marks are dispersed to the periphery of the foci together with Brd4 and transcription may continue. The controversy about the requirement of Brd4 for HPV replication in E1–E2 foci (Wang et al., 2013) might be due to different cell systems and by using ori-containing constructs versus complete genomes in the various studies.

3. Brd4 regulates viral transcription

The PV genome consists of the upstream regulatory region (URR) and nine to ten open reading frames (ORFs) encoding the viral early and late genes (see Fig. 1). Late gene expression takes place only in differentiated keratinocytes within the squamous epithelium and produces the structural proteins L1 and L2, which assemble into the viral capsid structure, whereas early gene expression starts in the basal cell layer producing the regulatory proteins E1–E8. PVs do not carry viral transcription factors in the viral capsid and are therefore initially dependent on the host cell transcription machinery.

Using an in vitro-reconstituted HPV chromatin transcription system to analyze cellular factors able to trigger gene activation from transcriptionally silenced HPV chromatin, AP-1 was identified as the key cellular factor initiating HPV transcription (Wu et al., 2006). Reconstitution and purification of various dimeric AP-1 complexes formed between Jun (c-Jun, JunB, and JunD) and Fos (c-Fos, FosB, Fra-1, and Fra-2) family proteins (Wang et al., 2008) allowed an unambiguous demonstration of the involvement of AP-1 binding to AP-1-binding sites present in every type of HPV genome (Wang et al., 2011). The establishment of an AP-1-dependent HPV chromatin transcription system made it possible to identify cellular factors critical for E2-mediated repression of HPV transcription, leading to the biochemical identification of Brd4 as an E2 core-pressor (Wu et al., 2006) that was later confirmed by an unbiased genome-wide siRNA knockdown screen (Smith et al., 2010).

While the N-terminal domain of all E2 proteins interacts with the CTM of Brd4, the C-terminal domain of low-risk E2 only binds to Brd4 when the N-terminal CK2 phosphorylation site cluster (i.e., NPS) of Brd4 is unphosphorylated as this exposes the internal BID interaction domain of Brd4 (see Fig. 3B). The C-terminal domain of high-risk E2, however, binds to phosphorylated as well as unphosphorylated Brd4 (Fig. 3C). The significance of this observation for viral genome maintenance and viral pathogenesis needs to be further investigated. Via sequence alignment between HR-E2 and LR-E2 as well as structure-guided mutagenesis analysis, the molecular determinants of phospho-NPS-interacting residues were mapped to two basic residues (K306 and K307 in HPV16 E2, and R307 and K308 in HPV18 E2) situated on the immediate C-terminal end of the E2 DBD. These residues do not interfere with E2 binding to DNA and appear conserved among the phospho-NPS-binding domain in the p53 C-terminal region as well as the BID and Brd4 itself (Wu et al., 2016). Substitutions of the corresponding residues in HPV11 E2 (N304 and D305) to KK, as found in HPV16 E2, converted HPV11 E2 into a phospho-NPS-interacting protein, highlighting the importance of these two basic residues in dictating specific E2 contact with phosphorylated residues in Brd4. This phospho switch-regulated Brd4 interaction with E2, potentially fine-tuned by the opposing activity of CK2 and PP2A through epithelial differentiation, is likely important for all steps of the PV life cycle where the Brd4-E2 complex is involved in the control of viral and host gene transcription.

4. Brd4 and E2 in the regulation of cellular genes and their role for tumorigenesis

Vosa et al. conclusively demonstrated that the host genome contains a large number of E2BSs (Vosa et al., 2012) and a previous report showed that E2 binds to active cellular promotors in a genome-wide ChIP-on-chip analysis (Jang et al., 2009). In addition, a global microarray screen of HPV16 E2 overexpressed in C-33A cells revealed widespread differences in host gene expression profiles compared to the control (Ramirez-Salazar et al., 2011). However, to date only a limited number of genes are validated to be regulated by E2. These include MMP-9 (Behren et al., 2005), hTERT (Lee et al., 2002), SF2/ASF (Klymenko et al., 2016; Mole et al., 2009), IL-10 (Bermudez-Morales et al., 2011), p21 (Steger et al., 2002), involucrin (Hadaschik et al., 2003), β4-integrin (Oldak et al., 2010) and most recently c-Fos (Delcuratolo et al., 2016). Brd4 is necessary for E2’s function as a transcriptional activator when E2BS is positioned away from the promoter-proximal region in an enhancer-like sequence context (Lee and Chiang, 2009) as found in CRPV (see Fig. 1, top drawing) and cellular MMP-9. At present, involvement of Brd4 together with E2 in the regulation of host gene transcription has only been demonstrated for MMP-9 and c-Fos.

Activator protein-1 (AP-1) includes a group of 18 homo/hetero-dimers formed between Jun and Fos family members (Wang et al., 2008), which function as sequence-specific transcription factors. AP-1-binding sites are present in many viral and cellular promoters, particularly in genes related to cellular processes such as differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis. At least one AP-1-binding site is present in every enhancer of PVs and is a major determinant of the total enhancer activity (Chan et al., 1990; Thierry et al., 1992). The AP-1 member c-Fos has recently been demonstrated to be transcriptionally upregulated by a concerted action of E2 and Brd4. This activation has further been shown to be important for papillomavirus-induced tumor formation (Delcuratolo et al., 2016), which is also supported by previous findings showing that c-Fos is overexpressed in HPV-positive lesions (Nurnberg et al., 1995) and that a shift from c-Jun/Fra-1 to c-Jun/c-Fos dimers occurs during HPV-induced carcinogenesis (de Wilde et al., 2008). An increase of c-Fos expression via E2 and Brd4 also results in the activation of the viral promotor, which leads to an increase in oncogene expression and rendering all components of this regulatory cascade essential for tumorigenesis (Behren et al., 2005). AP-1-dependent promoters are upregulated by a complex consisting of full-length Brd4 and E2 and this mechanism depends on the phosphorylation status of the NPS within the Brd4 protein as well as on the HPV-type specific E2 protein and the differentiation status of keratinocytes (Wu et al., 2016).

Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) belongs to the protein family of zinc-metalloproteinases and is involved in the degradation of collagen within the extracellular matrix. In the presence of E2, MMP-9 expression is increased (Akgul et al., 2011; Behren et al., 2005; Gasparian et al., 2007; Muhlen et al., 2009). However, Behren et al. (2005) showed that specific binding of E2 to the −670 bp upstream region of the MMP-9 promotor was not necessary for activation and that transcription was rather mediated through a mechanism involving AP-1 binding. An involvement of Brd4 in MMP-9 transactivation was first indirectly shown by using an I73A E2 mutant defective in Brd4-binding and transactivation, which resulted in a loss of MMP-9 induction (Behren et al., 2005). Nevertheless, when differentiated keratinocytes were used, direct E2 binding to its cognate sequence in the native −2 kb upstream chromatinized MMP-9 gene was critical for E2-regulated MMP-9 gene transcription in addition to its potentiating effect on AP-1 and NFκB binding to their cognate sequences (Wu et al., 2016), again indicating a cell state-specific and context-dependent gene regulation.

In proliferating keratinocytes, MMP-9 transcription is generally low, if detectable, as NFκB is absent in the nucleus and only HR- or LR-E2 and JunB or JunD, representing either repressive (or weak) AP-1 activity, are found in the promoter-proximal region of MMP-9 (Fig. 4, upper panel). Upon differentiation, binding of JunB and JunD to two promoter-proximal AP-1-binding sites is replaced by the potent c-Jun activator, along with differentiation-induced nuclear translocation of NFκB that binds to the NFκB site whose binding is further enhanced by HR-E2 via phospho-NPS-dependent Brd4 association (Fig. 4, lower panel). All the binding events in proliferating and differentiating keratinocytes require Brd4, as inclusion of the BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 for 24 h completely abolished the recruitment of E2, AP-1 and NFκB to their cognate sequences (Wu et al., 2016), highlighting the importance of Brd4 in facilitating the formation of an active enhanceosome-like complex in combinatorial regulation of gene transcription. In contrast, the phospho-Brd4-targeting DC-1 peptoid (Cai et al., 2011) only selectively inhibited phospho-NPS-potentiated HR-E2 binding to the E2BS in proliferating keratinocytes and phospho-NPS-and HR-E2-enhanced NFκB binding to the NFκB site upon induced differentiation, without globally inhibiting other factor recruitment to their respective chromatin target sites (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Model for MMP-9 gene transcription in proliferating and differentiating keratinocytes regulated by E2, NFκB and AP-1 family members. Binding of JunB and JunD to three AP-1 sites in MMP-9 in proliferating keratinocytes is replaced by c-Jun binding to two promoter-proximal AP-1 sites upon differentiation, which is coupled with differentiation-induced translocation of NFκB from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. DC-1 is a phospho-Brd4-targeting peptoid (Cai et al., 2011) that effectively blocks phosphorylation-dependent Brd4 function in stimulating high-risk (HR) E2 binding to its cognate sequence in proliferating keratinocytes or in enhancing NFκB binding to the NFκB site upon differentiation.

A pivotal role of Brd4 in in vivo tumorigenesis was recently demonstrated by using a recombinant CRPV genome carrying an shRNA expression cassette for knocking down endogenous rabbit Brd4 for the infection of New Zealand white rabbits (Leiprecht et al., 2014). With the help of two different shRNAs directed against rabbit Brd4 in the context of all early viral genes expressed at physiological levels, an important role of Brd4 for tumor formation and endogenous enhanced c-Fos expression in the wt CRPV-induced tumors was shown (Delcuratolo et al., 2016). Mutant genomes with an E2 defective for Brd4 binding (Jeckel et al., 2003) caused only very few tumors, which revealed severely retarded growth and were defective in enhanced c-Fos expression. These findings underline the potential oncogenic activities of the E2 proteins of kappa and beta PVs in conjunction with Brd4 (Delcuratolo et al., 2016; Schaper et al., 2005).

Besides transcription, Brd4 phosphorylation also plays a critical role in HPV origin replication as loss of E1- and E2-dependent HPV origin replication upon endogenous Brd4 knockdown in C-33A cells could only be rescued by reintroducing wild-type but not phosphorylation-defective Brd4 protein (Wu et al., 2016). Because only phosphorylated Brd4 is active in binding acetylated chromatin and regulating viral transcription and origin replication (Fig. 5, upper panel), control of Brd4 phosphorylation by pharmaceutical inhibitors or activators of CK2 and PP2A, or the use of phospho-PDID-targeting compounds such as DC-1 peptoid (Fig. 5, lower panel), should be useful in modulating HPV life cycle. Moreover, the effectiveness of phospho-Brd4-targeting compounds (Cai et al., 2011) in blocking the phosphorylation-dependent Brd4 function in gene transcription also provides a proof-of-principal in developing drug inhibitors targeting the phospho region of Brd4 (Wu et al., 2016).

Fig. 5.

Phospho-Brd4 is critical for HPV origin replication and viral early promoter-driven transcription. Phosphorylation of Brd4 plays a positive role in enhancing E1- and E2-dependent HPV origin replication but is also required for E2-mediated inhibition of HPV early promoter activity (upper panel). In the presence of phospho-PDID (pPDID)-targeting compounds such as DC-1 peptoid, Brd4 interaction with E2 is inhibited, leading to suppressed origin replication but enhanced early promoter transcription (lower panel).

5. Conclusions

Brd4 is involved in multiple steps of the PV life cycle including replication initiation, viral gene transcription as well as viral genome segregation and maintenance during cell division. Brd4 also plays a crucial role in regulating cellular gene expression in order to provide a facilitating environment for initiation of viral transcription and viral replication ultimately leading to the spread of viral particles and/or PV-induced carcinogenesis. As PVs heavily rely on Brd4 for all these activities, it could possibly be a prime candidate target for therapeutic intervention strategies. Pharmacological inhibitors specific for BET bromodomains have been shown to be effective in the treatment of hematopoietic cancers and solid tumors (Zhang et al., 2015). This class of inhibitors disrupts the chromatin-binding function of Brd4. Recently, phospho-Brd4 targeting compounds, different from the widely used BET inhibitors, have further increased the therapeutic potential of targeting BET proteins for antiviral and cancer therapy. Targeting phospho-Brd4 offers an advantage that the global chromatin-binding activity of Brd4 remains unaffected while specifically inhibiting phosphorylation-dependent gene-specific transcription pathways (Chiang, 2016). Future research needs to evaluate the applicability of these specific Brd4 inhibitors for the treatment of PV infections as well as PV-induced cancers.

Acknowledgments

Research in the Chiang lab is currently supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA103867), Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP110471 and RP140367), and the Welch Foundation (I-1805). Reseach in the Iftner lab was supported by the German research Foundation (DFG), grant number SFB 773 B4.

References

- Abbate EA, Voitenleitner C, Botchan MR. Structure of the papillomavirus DNA-tethering complex E2:Brd4 and a peptide that ablates HPV chromosomal association. Mol. Cell. 2006;24(6):877–889. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akgul B, Garcia-Escudero R, Ekechi C, Steger G, Navsaria H, Pfister H, Storey A. The E2 protein of human papillomavirus type 8 increases the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in human keratinocytes and organotypic skin cultures. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2011;200(2):127–135. doi: 10.1007/s00430-011-0183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behren A, Simon C, Schwab RM, Loetzsch E, Brodbeck S, Huber E, Stubenrauch F, Zenner HP, Iftner T. Papillomavirus E2 protein induces expression of the matrix metalloproteinase-9 via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/activator protein-1 signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11613–11621. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergvall M, Melendy T, Archambault J. The E1 proteins. Virology. 2013;445(1–2):35–56. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The protein data bank. Nucl. Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez-Morales VH, Peralta-Zaragoza O, Alcocer-Gonzalez JM, Moreno J, Madrid-Marina V. IL-10 expression is regulated by HPV E2 protein in cervical cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2011;4(2):369–375. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D, Lee AY, Chiang CM, Kodadek T. Peptoid ligands that bind selectively to phosphoproteins. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21(17):4960–4964. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WK, Chong T, Bernard HU, Klock G. Transcription of the transforming genes of the oncogenic human papillomavirus-16 is stimulated by tumor promotors through AP1 binding sites. Nucl. Acids Res. 1990;18(4):763–769. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SW, Liu WC, Liao KY, Tsao YP, Hsu PH, Chen SL. Phosphorylation of HPV-16 E2 at serine 243 enables binding to Brd4 and mitotic chromosomes. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CM. Brd4 engagement from chromatin targeting to transcriptional regulation: selective contact with acetylated histone H3 and H4. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2009;1:98. doi: 10.3410/B1-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CM. Phospho-BRD4: transcription plasticity and drug targeting. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2016;19:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Bakkenist CJ. Brd4 shields chromatin from ATM kinase signaling storms. Sci. Signal. 2013;6(293):pe30. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wilde J, De-Castro Arce J, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Rosl F, Steenbergen RD. Alterations in AP-1 and AP-1 regulatory genes during HPV-induced carcinogenesis. Cell. Oncol. 2008;30(1):77–87. doi: 10.1155/2008/279656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcuratolo M, Fertey J, Schneider M, Schuetz J, Leiprecht N, Hudjetz B, Brodbeck S, Corall S, Dreer M, Schwab RM, Grimm M, Wu SY, Stubenrauch F, Chiang CM, Iftner T. Papillomavirus-associated tumor formation critically depends on c-Fos expression induced by viral protein E2 and bromodomain protein brd4. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(1):e1005366. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaiah BN, Case-Borden C, Gegonne A, Hsu CH, Chen Q, Meerzaman D, Dey A, Ozato K, Singer DS. BRD4 is a histone acetyltransferase that evicts nucleosomes from chromatin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016a;23(6):540–548. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaiah BN, Gegonne A, Singer DS. Bromodomain 4: a cellular Swiss army knife. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016b;100(4):679–686. doi: 10.1189/jlb.2RI0616-250R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson MM, Boner W, Morgan IM. TopBP1 regulates human papillomavirus type 16 E2 interaction with chromatin. J. Virol. 2007;81(8):4338–4342. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02353-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd SR, Pacold ME, Huang Q, Clarke SM, Lam FC, Cannell IG, Bryson BD, Rameseder J, Lee MJ, Blake EJ, Fydrych A, Ho R, Greenberger BA, Chen GC, Maffa A, Del Rosario AM, Root DE, Carpenter AE, Hahn WC, Sabatini DM, Chen CC, White FM, Bradner JE, Yaffe MB. The bromodomain protein Brd4 insulates chromatin from DNA damage signalling. Nature. 2013;498(7453):246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparian AV, Fedorova MD, Kisselev FL. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 transcription in squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix: the role of human papillomavirus gene E2 expression and activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB. Biochemistry. 2007;72(8):848–853. doi: 10.1134/s0006297907080068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaschik D, Hinterkeuser K, Oldak M, Pfister HJ, Smola-Hess S. The Papillomavirus E2 protein binds to and synergizes with C/EBP factors involved in keratinocyte differentiation. J. Virol. 2003;77(9):5253–5265. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5253-5265.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedicke J, Iftner T. Human papillomaviruses and cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2013;108(3):397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou SY, Wu SY, Zhou T, Thomas MC, Chiang CM. Alleviation of human papillomavirus E2-mediated transcriptional repression via formation of a TATA binding protein (or TFIID)-TFIIB-RNA polymerase II-TFIIF preinitiation complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20(1):113–125. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.113-125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howley PM, Pfister HJ. Beta genus papillomaviruses and skin cancer. Virology. 2015;479–480:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.004. https://pave.niaid.nih.gov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang MK, Kwon D, Mc Bride AA. Papillomavirus E2 proteins and the host BRD4 protein associate with transcriptionally active cellular chromatin. J. Virol. 2009;83(6):2592–2600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02275-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang MK, Shen K, McBride AA. Papillomavirus genomes associate with BRD4 to replicate at fragile sites in the host genome. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(5):e1004117. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeckel S, Loetzsch E, Huber E, Stubenrauch F, Iftner T. Identification of the E9/E2C cDNA and functional characterization of the gene product reveal a new repressor of transcription and replication in cottontail rabbit papillomavirus. J. Virol. 2003;77(16):8736–8744. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8736-8744.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaja M, Silla T, Ustav E, Ustav M. Papillomavirus DNA replication – from initiation to genomic instability. Virology. 2009;384(2):360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS, Tam JK, Wang AF, Hegde RS. The structural basis of DNA target discrimination by papillomavirus E2 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(40):31245–31254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klymenko T, Hernandez-Lopez H, MacDonald AI, Bodily JM, Graham SV. Human papillomavirus E2 regulates SRSF3 (SRp20) to promote capsid protein expression in infected differentiated keratinocytes. J. Virol. 2016;90(10):5047–5058. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03073-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T, Myung K, Donaldson AD. Is PCNA unloading the central function of the Elg1/ATAD5 replication factor C-like complex? ABBV Cell Cycle. 2013;12(16):2570–2579. doi: 10.4161/cc.25626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AY, Chiang CM. Chromatin adaptor Brd4 modulates E2 transcription activity and protein stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(5):2778–2786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805835200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Kim HZ, Jeong KW, Shim YS, Horikawa I, Barrett JC, Choe J. Human papillomavirus E2 down-regulates the human telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(31):27748–27756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiprecht N, Notz E, Schuetz J, Haedicke J, Stubenrauch F, Iftner T. A novel recombinant papillomavirus genome enabling in vivo RNA interference reveals that YB-1, which interacts with the viral regulatory protein E2, is required for CRPV-induced tumor formation in vivo. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2014;4(3):222–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride AA, Jang MK. Current understanding of the role of the Brd4 protein in the papillomavirus lifecycle. Viruses. 2013;5(6):1374–1394. doi: 10.3390/v5061374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride AA. The papillomavirus E2 proteins. Virology. 2013;445(1–2):57–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mole S, Milligan SG, Graham SV. Human papillomavirus type 16 E2 protein transcriptionally activates the promoter of a key cellular splicing factor, SF2/ASF. J. Virol. 2009;83(1):357–367. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01414-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody CA, Laimins LA. Human papillomaviruses activate the ATM DNA damage pathway for viral genome amplification upon differentiation. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(10):e1000605. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlen S, Behren A, Iftner T, Plinkert PK, Simon C. AP-1 and ERK1 but not p38 nor JNK is required for CRPV early protein 2-dependent MMP-9 promoter activation in rabbit epithelial cells. Virus Res. 2009;139(1):100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberg W, Artuc M, Vorbrueggen G, Kalkbrenner F, Moelling K, Czarnetzki BM, Schadendorf D. Nuclear proto-oncogene products transactivate the human papillomavirus type 16 promoter. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;71(5):1018–1024. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldak M, Maksym RB, Sperling T, Yaniv M, Smola H, Pfister HJ, Malejczyk J, Smola S. Human papillomavirus type 8 E2 protein unravels JunB/Fra-1 as an activator of the beta4-integrin gene in human keratinocytes. J. Virol. 2010;84(3):1376–1386. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01220-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira JG, Colf LA, McBride AA. Variations in the association of papillomavirus E2 proteins with mitotic chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103(4):1047–1052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507624103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poddar A, Reed SC, McPhillips MG, Spindler JE, McBride AA. The human papillomavirus type 8 E2 tethering protein targets the ribosomal DNA loci of host mitotic chromosomes. J. Virol. 2009;83(2):640–650. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01936-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, Sowa ME, Ottinger M, Smith JA, Shi Y, Harper JW, Howley PM. The Brd4 extraterminal domain confers transcription activation independent of pTEFb by recruiting multiple proteins, including NSD3. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;31(13):2641–2652. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01341-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Salazar E, Centeno F, Nieto K, Valencia-Hernandez A, Salcedo M, Garrido E. HPV16 E2 could act as down-regulator in cellular genes implicated in apoptosis, proliferation and cell differentiation. Virol. J. 2011;8:247. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp B, Pawellek A, Kraetzer F, Schaefer M, May C, Purdie K, Grassmann K, Iftner T. Cell-type-specific separate regulation of the E6 and E7 promoters of human papillomavirus type 6a by the viral transcription factor E2. J. Virol. 1997;71(9):6956–6966. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6956-6966.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara N, Mitra R, McBride AA. The papillomavirus E1 helicase activates a cellular DNA damage response in viral replication foci. J. Virol. 2011;85(17):8981–8995. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00541-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara N, Chen D, Jang MK, Kang DW, Luecke HF, Wu SY, Chiang CM, McBride AA. Brd4 is displaced from HPV replication factories as they expand and amplify viral DNA. PLoS Pathog. 2013a;9(11):e1003777. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara N, Chen D, McBride AA. Papillomaviruses use recombination-dependent replication to vegetatively amplify their genomes in differentiated cells. PLoS Pathog. 2013b;9(7):e1003321. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper ID, Marcuzzi GP, Weissenborn SJ, Kasper HU, Dries V, Smyth N, Fuchs P, Pfister H. Development of skin tumors in mice transgenic for early genes of human papillomavirus type 8. Cancer Res. 2005;65(4):1394–1400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar V, Reed SC, McBride AA. Interaction of the betapapillomavirus E2 tethering protein with mitotic chromosomes. J. Virol. 2010;84(1):543–557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01908-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PP, Friedman CL, Bryant EM, McDougall JK. Viral integration and fragile sites in human papillomavirus-immortalized human keratinocyte cell lines. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1992;5(2):150–157. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, White EA, Sowa ME, Powell ML, Ottinger M, Harper JW, Howley PM. Genome-wide siRNA screen identifies SMCX, EP400, and Brd4 as E2-dependent regulators of human papillomavirus oncogene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107(8):3752–3757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914818107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger G, Schnabel C, Schmidt HM. The hinge region of the human papillomavirus type 8 E2 protein activates the human p21(WAF1/CIP1) promoter via interaction with Sp1. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83(Pt. 3):503–510. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubenrauch F, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus life cycle: active and latent phases. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1999;9(6):379–386. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry F, Spyrou G, Yaniv M, Howley P. Two AP1 sites binding JunB are essential for human papillomavirus type 18 transcription in keratinocytes. J. Virol. 1992;66(6):3740–3748. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3740-3748.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorslaer K, Tan Q, Xirasagar S, Bandaru S, Gopalan V, Mohamoud Y, Huyen Y, McBride AA. The Papillomavirus Episteme: a central resource for papillomavirus sequence data and analysis. Nucl. Acids Res. 2013;41:D571–D578. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks984. (Database issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosa L, Sudakov A, Remm M, Ustav M, Kurg R. Identification and analysis of papillomavirus E2 protein binding sites in the human genome. J. Virol. 2012;86(1):348–357. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05606-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WM, Lee AY, Chiang CM. One-step affinity tag purification of full-length recombinant human AP-1 complexes from bacterial inclusion bodies using a polycistronic expression system. Protein Expr. Purif. 2008;59(1):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WM, Wu SY, Lee AY, Chiang CM. Binding site specificity and factor redundancy in activator protein-1-driven human papillomavirus chromatin-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(47):40974–40986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Helfer CM, Pancholi N, Bradner JE, You J. Recruitment of Brd4 to the human papillomavirus type 16 DNA replication complex is essential for replication of viral DNA. J. Virol. 2013;87(7):3871–3884. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03068-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Chiang CM. The double bromodomain-containing chromatin adaptor Brd4 and transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(18):13141–13145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Lee AY, Hou SY, Kemper JK, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Chiang CM. Brd4 links chromatin targeting to HPV transcriptional silencing. Genes Dev. 2006;20(17):2383–2396. doi: 10.1101/gad.1448206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Lee AY, Lai HT, Zhang H, Chiang CM. Phospho switch triggers Brd4 chromatin binding and activator recruitment for gene-specific targeting. Mol. Cell. 2013;49(5):843–857. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Nin DS, Lee AY, Simanski S, Kodadek T, Chiang CM. BRD4 phosphorylation regulates HPV E2-mediated viral transcription, origin replication, and cellular MMP-9 expression. Cell Rep. 2016;16(6):1733–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Li Q, Lievens S, Tavernier J, You J. Abrogation of the Brd4-positive transcription elongation factor B complex by papillomavirus E2 protein contributes to viral oncogene repression. J. Virol. 2010;84(1):76–87. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01647-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Smith SG, Zhou MM. Discovery of chemical inhibitors of human bromodomains. Chem. Rev. 2015;115(21):11625–11668. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]