Abstract

Activation of the serine-threonine kinase Akt promotes the survival and proliferation of various cancers. Hypoxia promotes the resistance of tumor cells to specific therapies. We therefore explored a possible link between hypoxia and Akt activity. We found that Akt was prolyl-hydroxylated by the oxygen-dependent hydroxylase EglN1. The von Hippel–Lindau protein (pVHL) bound directly to hydroxylated Akt and inhibited Akt activity. In cells lacking oxygen or functional pVHL, Akt was activated to promote cell survival and tumorigenesis. We also identified cancer-associated Akt mutations that impair Akt hydroxylation and subsequent recognition by pVHL, thus leading to Akt hyperactivation. Our results show that microenvironmental changes, such as hypoxia, can affect tumor behaviors by altering Akt activation, which has a critical role in tumor growth and therapeutic resistance.

Inactivation of the VHL tumor suppressor gene is the gatekeeper event in most hereditary [von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease] and sporadic clear-cell renal carcinomas (ccRCCs) (1–3). Approved targeted therapies against advanced renal carcinomas include mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (rapalogs) (4–6). Preclinical cancer models indicated that loss of VHL or phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) increases rapalog sensitivity (7). Because Akt is frequently activated in VHL-defective renal carcinomas (8), we thus tested whether VHL protein (pVHL) might directly regulate Akt.

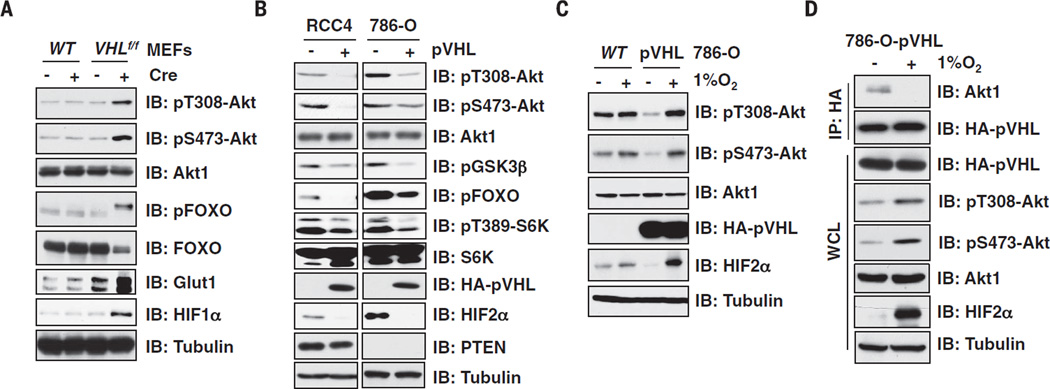

Cre-mediated deletion of VHL in conditional VHL-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts(MEFs) (9) increased Akt activity, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation at threonine 308 (pT308-Akt) and serine 473 (pS473-Akt) (Fig. 1A). Reintroducing pVHL in VHL-deficient renal carcinoma cells reduced pT308-Akt, and to a lesser extent pS473-Akt, in cells (Fig. 1B and fig. S1, A and B) and decreased Akt kinase activity in biochemical assays (fig. S1, C and D). Because phosphorylation of T308-Akt plays a more critical role in activating Akt than does phosphorylation of S473 (10), we focused on the regulation of the former by pVHL. (Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: A, Ala; C, Cys; D, Asp; E, Glu; F, Phe; G, Gly; H, His; I, Ile; K, Lys; L, Leu; M, Met; N, Asn; P, Pro; Q, Gln; R, Arg; S, Ser; T, Thr; V, Val; W, Trp; and Y, Tyr. In the mutants, other amino acids were substituted at certain locations; for example, P125N indicates that proline at position 125 was replaced by asparagine.)

Fig. 1. pVHL suppresses Akt phosphorylation.

(A) Immunoblot (IB) analysis of whole-cell lysates (WCL) derived from VHLf/f MEFs infected with Cre or control (EV) lentivirus. (B) IB analysis of WCL derived from RCC4 or 786-O cells infected with EV or VHL retrovirus. (C and D) 786-O cells were engineered via retroviral infection to stably express pVHL and harvested for hemagglutinin-immunoprecipitation (HA-IP) or IB analysis after culturing under normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2) condition for 16 hours.

To test whether the regulation of Akt by pVHL in our system was hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)–dependent, we depleted HIF1β (11) in renal carcinoma cells, which did not decrease pT308-Akt (fig. S2, A and B). Similarly, silencing HIF2α in 786-O cells or ectopically expressing a non-degradable HIF2α-PA (12, 13) in various cell lines did not alter pT308-Akt (fig. S2, C to F). Taken together, these results point to a HIF-independent link between pVHL and Akt activity.

Total Akt abundance was not affected by manipulating pVHL in different cell lines (Fig. 1, A and B). This left open the possibility that pVHL specifically polyubiquitylates phospho-Akt. However, depletion of Cullin 2, which is required for pVHL-dependent ubiquitylation and leads to stabilized HIF2α (14) as expected, did not affect Akt phosphorylation (fig. S2G). These data suggest that pVHL suppresses Akt kinase activity in an E3 ligase–independent manner.

Overexpressed pVHL bound to Akt1 and Akt2 but not to Akt3 (fig. S3, A to E). In contrast to the binding of HIF1α to pVHL (15, 16), Akt bound to wild type (WT) and most type 2 but not type 1 pVHL mutants (fig. S3, F to I) (3, 16). Site-directed mutagenesis of critical residues within the hydroxyl-proline binding pocket of pVHL (13, 17) revealed that pVHL residues critical for binding to Akt1 and HIF1α partially overlap but are not identical (fig. S3, J to M). Likewise, WT and most type 2 but not type 1 pVHL mutants inhibited pT308-Akt in 786-O cells (fig. S3N), suggesting that pVHL suppresses Akt through a direct physical association. Consistent with our findings in cell lines, pT308-Akt was increased in human VHL mutant ccRCC clinical samples relative to surrounding normal tissues (fig. S4, A to C).

HIFα must be prolyl-hydroxylated by the egg-laying defective nine (EglN) oxygen-sensitive enzymes to bind pVHL (18–20). To test whether inhibition of Akt by pVHL is likewise regulated by oxygen, we exposed cells to 1% O2 or the EglN inhibitor dimethyloxaloylglycine (DMOG). Both treatments increased pT308-Akt in VHL-proficient but not VHL-deficient ccRCC cells (Fig. 1C and fig. S5A) in a HIF2α-independent manner (fig. S5B). Hypoxia and hypoxia-mimetics also disrupted the interaction of pVHL with Akt1 (Fig. 1D and fig. S5, C to G).

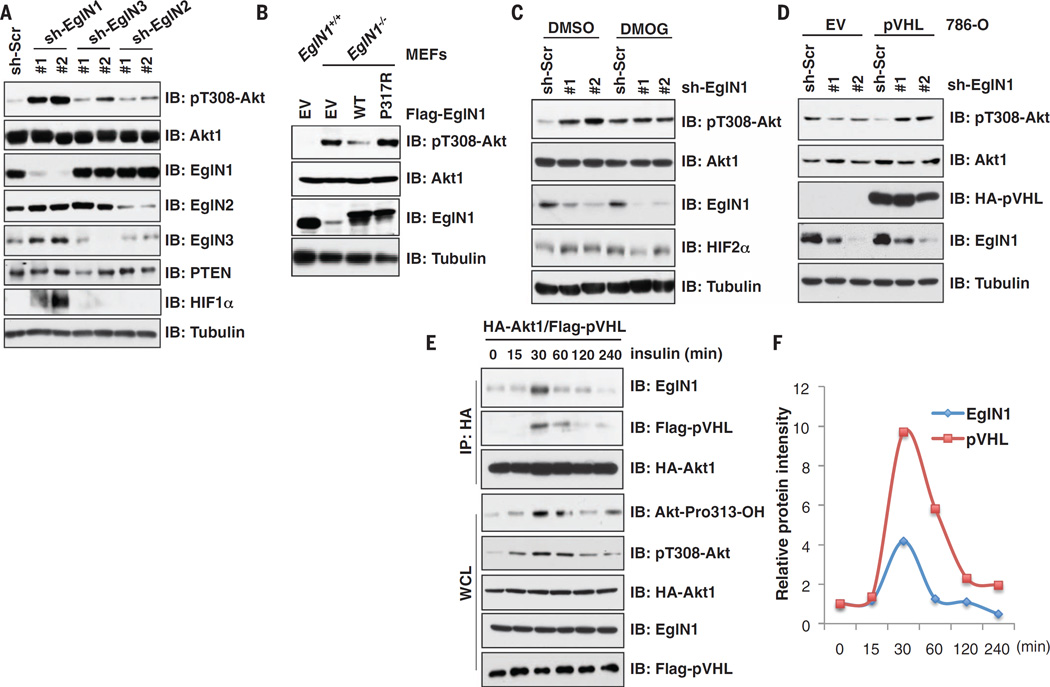

Depletion of EglN1 (also termed PHD2), but not EglN2 or EglN3, increased Akt kinase activity in various cell lines (Fig. 2A and fig. S6, A to E). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can destabilize PTEN and thereby activate Akt (21, 22). However, EglN1 inactivation minimally induced cellular ROS levels and did not down-regulate PTEN (Fig. 2A and fig. S6, F to I). Akt hyperactivation was reversed by reintroducing wild-type but not catalytic-inactive EglN1 in EglN1−/− MEFs (Fig. 2B) or EglN1-depleted human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (fig. S6J). Furthermore, DMOG or hypoxia activated Akt in parental but not EglN1-depleted cells (Fig. 2C and fig. S6, K and L). Consistent with these findings, Akt1 bound to EglN1 but not EglN2 or EglN3, whereas both pVHL and EglN1 bound to Akt1 and Akt2 but not Akt3 (fig. S7, A to K). Moreover, the interaction of pVHL with Akt1 was abolished in EglN1-depleted cells (fig. S8, A to C), and depleting EglN1 resulted in increased pT308-Akt only in VHL-WT cells but not VHL-deficient cells (Fig. 2D and fig. S8, D and E). Hence, EglN1 is required for pVHL to suppress Akt.

Fig. 2. EglN1 mediates the inhibition of Akt by pVHL.

(A and C) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells (A) infected with different short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviruses, and then (C) treated with or without DMOG (200 µM) for 12 hours before harvesting. (B) IB analysis of EglN1−/− MEFs infected with retroviruses encoding WT or catalytic-inactive (P317R)mutant form of EglN1. (D) IB analysis of WCL derived from786-O-pVHL and EV cells lentivirally infected with Scramble (sh-Src) or EglN1 shRNAs. (E and F) IB analysis of IP and WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with indicated constructs. (E) The cells were serum-starved for 24 hours and then stimulated with insulin (0.1 µM) before harvesting. The relative intensities of EglN1 and pVHL immunoprecipitated by Akt1 in (E) are quantified in (F).

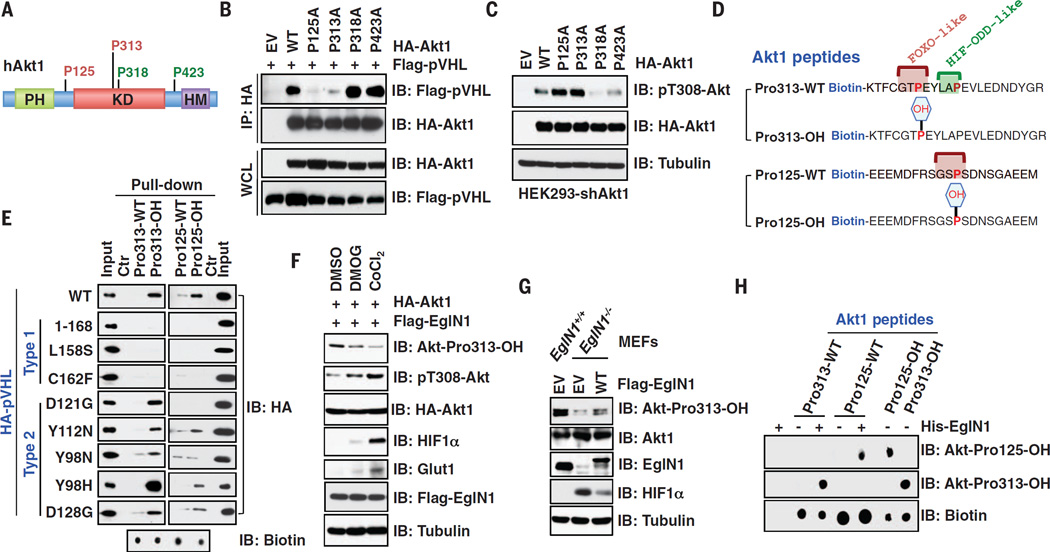

Both EglN1 and pVHL preferentially bound the activated form of Akt1 (E17K variant or myristoylated-Akt) (fig. S9, A to H) (23). Moreover, binding of EglN1 to Akt1 correlated with the appearance of pT308-Akt in cells stimulated with insulin or epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Fig. 2, E and F, and fig. S10, A to H). Conversely, blocking Akt phosphorylation decreased the interaction of Akt1 with EglN1 (fig. S10, I to K). To test whether Akt can be hydroxylated by EglN1, we identified hydroxylation of multiple Akt1 prolyl-residues including Pro125, Pro313, Pro318, and Pro423 by means of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis (Fig. 3A and fig. S11, A to E). These prolyl-residues are highly conserved and can be divided into HIF oxygen-dependent-degradation (ODD)–like sites (Pro318 and Pro423) (12, 13, 24) or Forkhead-Box-O3 (FOXO3)–like sites (Pro125 and Pro313) (fig. S11F) (25). Mutating FOXO-like but not HIF-ODD–like sites reduced the interaction of Akt1 with pVHL (Fig. 3B), leading to increased pT308-Akt (Fig. 3C), arguing that these two residues are pivotal for the regulation of Akt by pVHL. Mutating FOXO-like sites to HIF-ODD motifs in Akt1 impaired its interaction with indicated type 2 pVHL mutants (fig. S12, A to F), again supporting that the pVHL residues used to bind hydroxylated HIFα and Akt are similar but not identical.

Fig. 3. EglN1 hydroxylates Akt1 at the Pro125 and Pro313 residues to trigger Akt1 interaction with pVHL.

(A) A schematic illustration of Akt1 domain structures with four putative prolyl-hydroxylation residues identified by means of LC-MS/MS analysis. (B and C) IB analysis of co-immunoprecipitation and WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with Flag-pVHL and indicated HA-Akt1 constructs. (D) A schematic representation of the various biotinylated synthetic peptides used in this study. FOXO-like and HIF-ODD–like motifs were labeled in red and green, respectively. (E) Indicated peptides as denoted in (D) were incubated with WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with indicated constructs, and precipitated with streptavidin. (F) IB analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with indicated constructs. Where indicated, hypoxia mimetic reagents were used before harvesting for IB analysis. (G) IB analysis of WCL derived from WT or EglN1−/− MEFs infected with a retrovirus encoding Flag-tagged WT-EglN1. (H) In vitro hydroxylation assays with recombinant His-EglN1 and various Akt1 peptides were analyzed by means of dot immunoblot.

Mutations of Pro125 and Pro313 enhanced the interaction between Akt and its upstream kinase phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1), leading to increased pT308-Akt that is insensitive to DMOG treatment (fig. S13, A to D). Moreover, hydroxylation-dependent recruitment of pVHL promoted the interaction of Akt1, but not Akt3, with the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2AC) (fig. S14, A to D) (26), which dephosphorylates pT308-Akt (27). The binding of PP2AC to Akt1, but not Akt3, was diminished in cells deficient in EglN1 or VHL or by mutating the Akt1 FOXO-like motifs (fig. S14, E to I). Furthermore, recombinant pVHL promoted PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of pT308-Akt in vitro (fig. S14, J to L). Collectively, these data suggest that EglN1-induced hydroxylation of Akt suppresses Akt activation, in part, by triggering pVHL-mediated PP2A-induced dephosphorylation of pT308-Akt (fig. S14M).

To test whether prolyl-hydroxylation might alter the recognition of Akt1 by pVHL, we performed in vitro binding assays with biotinylated Akt1-derived peptides. Peptides spanning the Akt1 FOXO-like sites bound to pVHL in a hydroxylation-dependent manner (Fig. 3, D and E). Furthermore, hydroxylated Akt1 peptides bound to WT and most type 2 but not type 1 pVHL mutants (Fig. 3E and fig. S15, A to E). Synthetic hydroxyl-peptides derived from HIF1α or Akt1 competed with one another for binding to pVHL (fig. S15, F and G). To study the Akt1 FOXO-like hydroxylation sites in cells, we generated and validated antibodies to Akt-Pro125-OH or Akt-Pro313-OH (fig. S16, A to F). In agreement with EglN1 as the major upstream hydroxylase for Akt, recognition of Akt1 by the Akt-Pro313-OH antibody was diminished in EglN1-depleted cells and by hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3, F and G, and fig. S16, G to I). In multiple cell lines, Akt1 hydroxylation was triggered by growth factors (fig. S16, J to N). Using in vitro hydroxylation assays (fig. S17, A to C) (25, 28) coupled with MS analysis, we identified both Pro125 and Pro313 residues as hydroxylation sites by EglN1 (Fig. 3H and fig. S17, D to K).

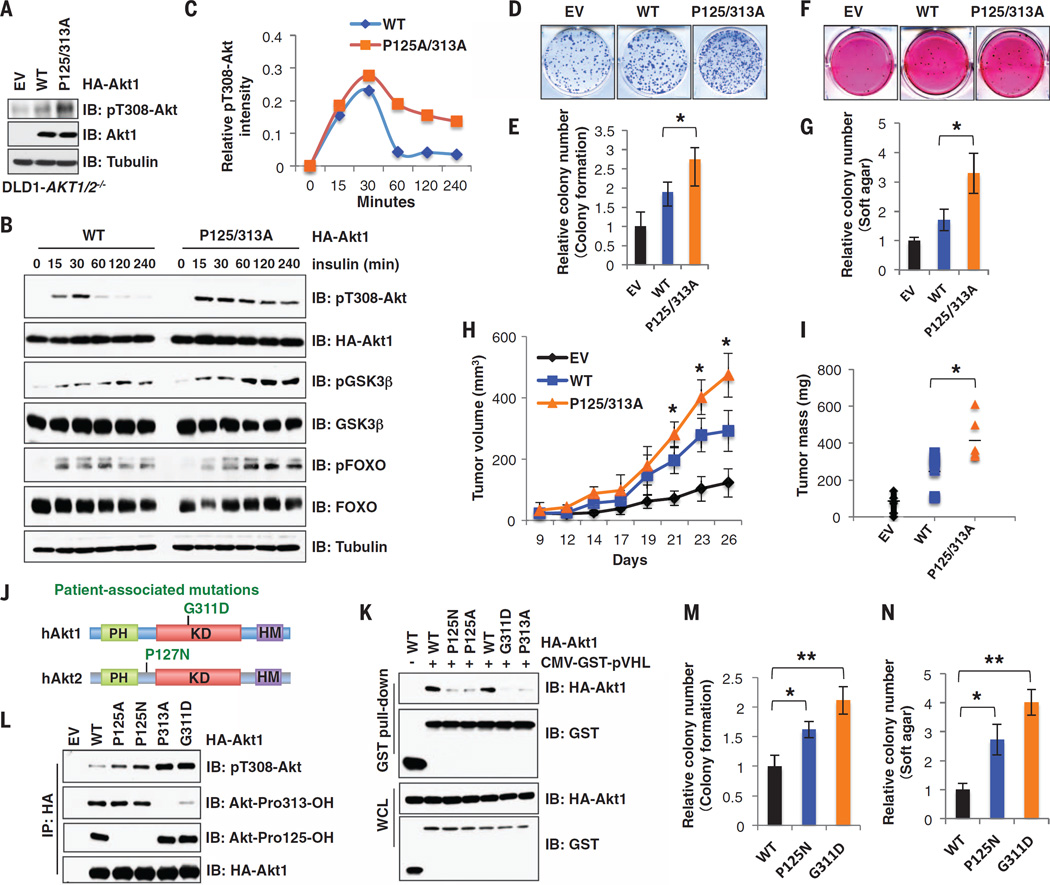

Given that aberrant Akt activation can alter cell survival and metabolism to favor tumorigenesis, we evaluated whether hydroxylation of Akt modulates Akt-oncogenic signaling. Reintroducing the FOXO-like hydroxylation-deficient mutants (P125A and/or P313A) of Akt1, but not the corresponding Akt3 variants, into DLD1-AKT1−/−/AKT2−/− cells (denoted AKT1/2−/−) led to increased pT308-Akt as compared with AKT1/2−/− cells expressing wild-type Akt (Fig. 4, A to C, and fig. S18, A to G). Moreover, P125A and/or P313A of Akt1, but not the corresponding mutation in Akt3, promoted colony formation and anchorage-independent growth in vitro, as well as enhanced tumor formation in vivo relative to wild-type Akt (Fig. 4, D to I, and fig. S18, H to R).

Fig. 4. Disruption of Akt proline-hydroxylation events leads to a sustained Akt kinase activation and increased colony formation and tumor growth.

(A to C) IB analysis of WCL derived fromDLD1-AKT1/2−/− cells (A) infected with lentiviruses encoding WT- or P125/313A-Akt1. (B) Cells were deprived of serum for 24 hours followed by stimulation with insulin (0.1 µM), and relative pT308-Akt intensity was quantified in (C). (D to G) Colony formation (D) and soft agar (F) assays were performed with DLD1-AKT1/2−/− cells generated in (A), and were quantified in (E) and (G) (mean ± SD, n = 3 wells per group). *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test). (H and I) Mouse xenograft experiments were performed with the cells generated in (A). Tumor growth curve (H) and tumor weight (I) were calculated (mean ± SD, n = 6 mice per group). *P < 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance test). (J) A schematic representation of cancer patient-associated Akt mutations. (K and L) Glutathione S-transferase pull-down and IP analysis of WCL derived from HEK293 cells transfected with indicated constructs. (M and N) Relative colony numbers were quantified for colony formation (M) and soft agar (N) assays (mean ± SD, n = 3 wells per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

We also identified two cancer-associated Akt mutations, Akt1-G311D and Akt2-P127N (www.cbioportal.org) (Fig. 4J) (29). The corresponding Akt mutants displayed reduced Akt hydroxylation, associated with reduced interaction with pVHL and PP2AC (Fig. 4K and fig. S19, A to E), leading to increased pT308-Akt (Fig. 4L). Biologically, reintroducing either P125N or G311D mutant of Akt1 or P127N-Akt2 in AKT1/2−/− cells led to sustained activation of Akt oncogenic signaling (fig. S19, F to I), as well as increased oncogenic functions (Fig. 4, M and N, and fig. S19, J to O). These results indicate that these cancer-associated mutations in Akt exhibit increased oncogenic activity because of loss of proline-hydroxylation–dependent inhibition of Akt by pVHL (fig. S19P).

Therefore, our studies revealed that hypoxia and deficiencies in the VHL/EGLN tumor-suppressive pathway, in a HIF-independent and prolyl hydroxylation–dependent manner, lead to aberrant Akt activation, which in many models promotes apoptotic resistance. Conceivably, hypoxia-induced Akt activation promotes the survival of stem cells within hypoxia niches, regenerating cells within ischemic tissues and wounds, and cancer cells within hypoxic tumors. In a VHL-deficient ccRCC setting, accumulation of HIFα and activated Akt are likely to be integrated to promote renal carcinogenesis and metastasis (30). This view provides further support for targeting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and/or Akt to treat pVHL-defective kidney cancers specifically and as a way to chemosensitize hypoxic tumors generally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. North, L. Wan, and other Wei laboratory members for critical reading of the manuscript; W. Yu for his critical help in providing the triple mutant form of VHL to analyze the critical amino acids in proline-hydroxylation binding pocket of VHL that mediates its interaction with hydroxylated Akt1; as well as members of Kaelin, Zhang, Toker, and Cheng laboratories for helpful discussions. J.G. is an NRSA T32 trainee and supported by 5T32HL007893-17. W.W. is an ACS research scholar. This work was supported in part by NIH grants (W.W., GM094777; W.W. and A.T., CA177910; and J.A., 1S10OD010612, 5P01CA120964, and 5P30CA006516).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/353/6302/929/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S19

References (31–38)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Chen F, et al. Hum. Mutat. 1995;5:66–75. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gossage L, Eisen T, Maher ER. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:55–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim WY, Kaelin WG. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:4991–5004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas GV, et al. Nat. Med. 2006;12:122–127. doi: 10.1038/nm1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudes G, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugarolas JB, Vazquez F, Reddy A, Sellers WR, Kaelin WG., Jr Cancer Cell. 2003;4:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hager M, et al. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13(8B):2181–2188. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young AP, et al. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:361–369. doi: 10.1038/ncb1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki M, Batista O, Bellacosa A, Tsichlis P, Vogt PK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:14950–14955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maltepe E, Schmidt JV, Baunoch D, Bradfield CA, Simon MC. Nature. 1997;386:403–407. doi: 10.1038/386403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maxwell PH, et al. Nature. 1999;399:271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min JH, et al. Science. 2002;296:1886–1889. doi: 10.1126/science.1073440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonergan KM, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:732–741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohh M, et al. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:423–427. doi: 10.1038/35017054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:5381–5392. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00282-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hon WC, et al. Nature. 2002;417:975–978. doi: 10.1038/nature00767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivan M, et al. Science. 2001;292:464–468. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaakkola P, et al. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu F, White SB, Zhao Q, Lee FS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:9630–9635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181341498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, et al. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang D, et al. Cell Reports. 2014;8:1930–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpten JD, et al. Nature. 2007;448:439–444. doi: 10.1038/nature05933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo W, et al. Cell. 2011;145:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng X, et al. Genes Dev. 2014;28:1429–1444. doi: 10.1101/gad.242131.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, et al. Nature. 2002;420:716–717. doi: 10.1038/nature01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millward TA, Zolnierowicz S, Hemmings BA. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:186–191. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang JH, et al. Anal. Biochem. 1999;271:137–142. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerami E, et al. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gan B, et al. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.