Abstract

Default mode network (DMN) deactivation has been shown to be functionally relevant for goal‐directed cognition. In this study, the DMN's role during olfactory processing was investigated using two complementary functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) paradigms with identical timing, visual‐cue stimulation, and response monitoring protocols. Twenty‐nine healthy, non‐smoking, right‐handed adults (mean age = 26 ± 4 years, 16 females) completed an odor–visual association fMRI paradigm that had two alternating odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. During odor + visual trials, a visual cue was presented simultaneously with an odor, while during visual‐only trial conditions the same visual cue was presented alone. Eighteen of the twenty‐nine participants (mean age = 27.0 ± 6.0 years, 11 females) also took part in a control no‐odor fMRI paradigm that consisted of a visual‐only trial condition which was identical to the visual‐only trials in the odor–visual association paradigm. Independent Component Analysis (ICA), extended unified structural equation modeling (euSEM), and psychophysiological interaction (PPI) were used to investigate the interplay between the DMN and olfactory network. In the odor–visual association paradigm, DMN deactivation was evoked by both the odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. In contrast, the visual‐only trials in the no‐odor paradigm did not evoke consistent DMN deactivation. In the odor–visual association paradigm, the euSEM and PPI analyses identified a directed connectivity between the DMN and olfactory network which was significantly different between odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. The results support a strong interaction between the DMN and olfactory network and highlights the DMN's role in task‐evoked brain activity and behavioral responses during olfactory processing. Hum Brain Mapp 38:1125–1139, 2017. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: fMRI, default mode network (DMN), olfaction

INTRODUCTION

The functional relevance of the Default Mode Network (DMN) deactivations during goal directed and externally oriented task performance has been well established [Anticevic et al., 2012; Calhoun et al., 2008]. For example, cognitive tasks, that demand attention and working or episodic memory, are generally accompanied by blood‐oxygen‐level‐dependent (BOLD) signal modulations in brain regions considered to be part of the DMN [Anticevic et al., 2012; Binder, 2012; Biswal et al., 1995; Buckner et al., 2008; Fox et al., 2005; Fox and Raichle, 2007; Greicius et al., 2003; Li et al., 2012; Raichle et al., 2001; Raichle and Snyder, 2007]. These task‐induced DMN deactivations represent competition for cognitive resources and have been shown to be proportional to the cognitive load associated with a task [McKiernan et al., 2003; Wen et al., 2013]. Therefore, data support the premise that DMN deactivation is a phenomenon characterized by rich cognitive activity that can potentially help unravel how brain networks interact during externally oriented task performance [Anticevic et al., 2012; Andrews‐Hanna, 2012; Fox et al., 2005; Hampson et al., 2006].

While DMN modulations have previously been reported during auditory‐ and visual‐sensory task performance, no study has explicitly investigated the DMN's role during olfactory processing [Greicius et al., 2009; Greicius and Menon, 2004]. This relationship is important because unlike other dominant human sensory systems such as vision, the multidimensional olfactory perception is highly dependent on top‐down as well as bottom‐up brain networks [Doty et al., 1994; Savic et al., 2000]. A tight functional connection between the DMN and the olfactory network, consisting of brain regions typically recognized to be responsible for generating an olfactory percept, may suggest that olfactory processing is subserved by attentional and memory demands [Gonzalez et al., 2006; Gottfried, 2010; Olofsson et al., 2012; Zelano et al., 2011]. This is in line with the notion that DMN interactions with task positive networks (TPNs) are modulating task‐evoked activity [Barber et al., 2013; Chai et al., 2014a; Di and Biswal, 2014]. For example, a dynamic point of view of the DMN's role suggests that the DMN activity before performing an executive or attentional task may predict subsequent task‐evoked brain response and behavioral performance [Fox and Raichle, 2007; Fox et al., 2006, 2007; Gottfried, 2010; Gottfried et al., 2002; Heimer, 1978; Royet et al., 2015; Saive et al., 2014; Wilson and Stevenson, 2006]. Therefore, investigating DMN deactivation during olfactory processing can further elucidate how the formation of a human odor percept is dynamically modulated at the neural network level, providing information about the role of DMN in a new sensory modality [Doty et al., 1994; Karunanayaka et al., 2014].

The goal of this research was to combine two functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) paradigms with an integrated analytical method that included Independent Component Analysis (ICA), extended unified structural equation modeling (euSEM), and psychophysiological interaction (PPI) to establish and characterize the interaction between the DMN and olfactory network. The two fMRI paradigms were complementary to each other and had identical timing, visual cue stimulation, and response monitoring protocols. The first odor–visual association or four‐intensity paradigm had alternating odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions [Karunanayaka et al., 2015]. During odor + visual trials, a visual cue was displayed simultaneously with an odor, while during visual‐only trials the same visual cue was presented alone. The no‐odor fMRI paradigm consisted of a visual‐only trial condition that was identical to the visual‐only trial condition in the odor–visual association paradigm.

Previously, we demonstrated a rapid and transient interaction between olfactory and visual networks by highlighting the ability of visual‐only trial conditions in the odor–visual association paradigm to elicit robust BOLD activation within primary and secondary olfactory structures [Bone and Jantrania, 1992; Karunanayaka et al., 2015; Maaswinkel and Li, 2003; Martinez et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 1995; Seigneuric et al., 2010; Seo et al., 2010]. These results raised further questions, including whether intrinsic resting state networks (RSNs), such as the DMN, are involved in odor processing or whether the visual cue itself is responsible for this activation [Karunanayaka et al., 2015]. One goal of the current study, therefore, was to delineate the interaction between the primary olfactory network (PON) and the DMN. The PON encompasses the primary olfactory cortex (POC), which is considered to be the earliest site of olfactory information processing and includes the piriform cortex, anterior olfactory nucleus, olfactory tubercle, entorhinal cortex, amygdala, and periamygdaloid cortex, regions that receive direct projections from the olfactory bulb [Gottfried, 2010]. Because of odor–visual pairing, we hypothesized a similar level of DMN deactivation during both the odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions in the odor–visual association paradigm [Karunanayaka et al., 2015]. In contrast, we hypothesized different levels of DMN deactivations between visual‐only trial conditions in the odor–visual association (or four‐intensity) and no‐odor paradigms. This is because the DMN deactivation caused by the same visual cue in the respective paradigms should be similar unless visual cues in the odor–visual association paradigm are influenced by the odor–visual pairing. Additionally, in the odor–visual association paradigm, we hypothesized differential DMN functional connectivity (FC) with the olfactory network during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. Such DMN connectivity may highlight that the communication between the DMN and olfactory network might play an important role in inhibiting unwanted brain activities, thus making behavior responses more reliable during goal‐directed, olfactory task performance [Anticevic et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2013].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Twenty‐nine healthy, non‐smoking, right‐handed young adult participants (mean age = 26 ± 4 years, 16 females) took part in the study with written consent and prior approval from the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB). All were screened for complications specific to olfactory dysfunction (e.g., viral infection, allergies) and MRI safety (e.g., metal implants, claustrophobia). All participants had normal smell function based on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) [Doty, 2000; Doty et al., 1984].

Experimental Design

Odor–visual association paradigm

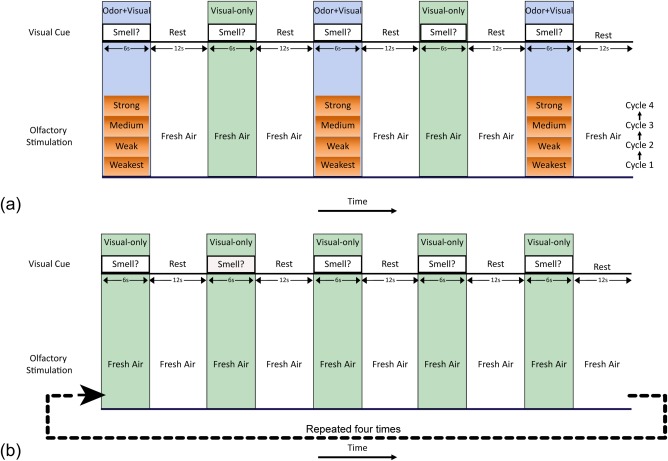

Figure 1a illustrates the details of the event related, odor–visual association lavender fMRI paradigm. In our previous publications, we have referred to this paradigm as the four‐intensity paradigm [Karunanayaka et al., 2014, 2015]. The unique advantages of this paradigm, including its ability to overcome olfactory habituation, have been discussed in detail elsewhere [Karunanayaka et al., 2014]. Odor delivery was synchronized with presentation of the visual cue, “Smell?” using a MR compatible olfactometer [Emerging Tech Trans, LLC, Hershey, PA; Karunanayaka et al., 2014]. Each odor + visual trial (6 s) was followed by two visual‐only trial conditions: the first consisted of 12 s of the visual cue “Rest,” and the second consisted of 6 s of the visual cue “Smell?”. Odorants were mixed with moisturized room temperature fresh air and delivered to both nostrils once every 36 s at a constant air flow‐rate of 8 L/min during odor + visual trials. The baseline air flow‐rate of 8 L/min was held constant so that odorant delivery was also at the same flow rate. To avoid tactile or thermal stimulation, the same constant fresh airflow was maintained across the visual‐only trial conditions. Participants were instructed to press a button with the index finger of their right hand to indicate that they smelled an odor, and to press with their left hand if they did not smell an odor. There was no time limit to respond and participants were not instructed to respond rapidly, but rather to be as accurate as possible. Participants were instructed to respond with a button press (i.e., as to whether or not an odorant was present) during both odor + visual and visual‐only conditions. Additionally, all participants were instructed not to sniff, but to follow their normal breathing patterns during fMRI scanning which were also monitored using a chest belt [Wang et al., 2011].

Figure 1.

(a) The odor–visual association or four‐intensity fMRI paradigm with alternating odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. During odor + visual trials, the visual cue, “Smell?,” was presented on an LCD screen paired with lavender odor. During visual‐only trials the same visual cue was presented by itself. The word “Rest” was displayed on the LCD screen during the rest period. Four intensities of lavender odorant were presented starting with the weakest intensity and ending with the strong intensity. Each intensity was presented three times before the next odor intensities were presented in a progressive manner from weakest to strong. A constant fresh airflow of 8 L/min was maintained throughout all conditions (including the “Rest”) to avoid tactile or thermal stimulation. Participants had to perform a button press response to indicate the presence/absence of an odor during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. (b) Eighteen of the study participants took part in the control no‐odor paradigm consisting of visual‐only trials during which a constant fresh airflow of 8 L/min was maintained. These visual‐only trials were identical in timing, visual‐cue stimulation and response motoring structure to that of the odor–visual association paradigm. Participants were also asked to respond to the presence or absence of an odor during each visual‐only trial. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The odorant intensities were adjusted by diluting lavender oil (Quest International Fragrances Co., Mount Olive, NJ) in 1,2‐propanediol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to generate weakest (0.032%), weak (0.10%), medium (0.32%), and strong (1.0%) odor intensities. Lavender odorant was used for several reasons: (1) most people can easily detect lavender odor intensity variations, (2) minimal habituation, and (3) lavender has no propensity to stimulate the trigeminal system [Allen, 1936; Grunfeld et al., 2005; Karunanayaka et al., 2014; Patton and Fulton, 1960; Wang et al., 2010]. Additionally, lavender is generally perceived as being pleasant and familiar by most North Americans.

No‐odor paradigm

To investigate the effects of the visual cue “Smell?” itself on DMN dynamics, eighteen subjects (mean age = 27.0 ± 6.0 years, 11 female) who also participated in the odor–visual association paradigm took part in a control no‐odor fMRI paradigm as shown in Figure 1b. These 18 subjects completed the two paradigms in a counterbalanced order. The no‐odor paradigm consisted of visual‐only trials during which the visual cue “Smell?” was presented alone with constant fresh airflow at the same flowrate as in the odor–visual association paradigm. These visual‐only trials were identical in timing, visual cue stimulation, and response monitoring to that of the visual‐only trials in the odor–visual association paradigm. Again, participants were asked to respond whether or not an odor was present during each visual‐only trial condition by pressing a button with the index finger of their right hand to indicate that they smelled an odor, and to press with their left hand if they did not smell an odor. Additionally, they were instructed not to sniff during fMRI scanning, but to follow their normal breathing patterns which were monitored using the chest belt.

In summary, the two paradigms had identical timing, visual cue stimulation, and response monitoring protocols. Behavioral performance during both fMRI paradigms was carefully monitored by the study coordinator during scanning. Button responses, respiration patterns and motion parameters were used to identify and exclude subjects with irregular respiration changes, excessive sniffing, and/or poor task performance. A post fMRI interview ensured that all subjects smelled odors only during the odor + visual condition and not during the visual‐only condition (see Supporting Information).

fMRI Image Acquisition

MR images of the entire brain were acquired using GE‐EPI (with an acceleration factor of 2) on a Siemens Trio 3.0 T system with the following parameters: time of repetition (TR)/time of echo (TE)/flip angle (FA) = 2,000 ms/30 ms/90°, FOV = 220 mm × 220 mm, acquisition matrix = 80 × 80, 30 slices, slice thickness = 4 mm, and the number of repetitions = 234. T1‐MPRAGE anatomical images were also acquired for anatomical underlay with the following parameters: slices = 160, slice thickness = 1 mm, FOV = 256 mm × 256 mm × 160 mm, matrix size = 256 × 256 × 160, TE = 30 ms, TR = 2,300 ms, and acquisition time = 321 s.

Data Analysis

The fMRI data were preprocessed with standard procedures such as realignment, co‐registration, normalization, and smoothing (8 mm) using the SPM 8 software [Wellcome Trust; Ashburner et al., 2009]. These steps were followed by ICA decomposition to identify spatially independent BOLD activation patterns and their temporal behavior during olfactory fMRI paradigms [Calhoun et al., 2001; Karunanayaka et al., 2007, 2010, 2014].

A promising feature of ICA is its ability to uncover hidden information otherwise hard to obtain from standard fMRI data analysis techniques. Group ICA methodology, as implemented in this manuscript, consisted of two parts: (1) preprocessing steps (i.e., mean centering and Principal Components Analysis (PCA)] at both individual (40 components) and group (50 components) levels, and (2) ICA decomposition (using 25 repeated runs of the FastICA algorithm), followed by hierarchical agglomerative clustering. Details of the ICA decomposition for this paradigm have been explained in Karunanayaka et al. [2014]. Finally, a voxel‐wise random effects analysis (one‐sample t‐test) was performed on individual IC maps to determine the group IC maps [Karunanayaka et al., 2014].

The task‐relatedness of each IC was determined by (1) the spectral power of the IC time course at the task frequency and (2) the phase of the IC time course relative to the task on‐off reference time course [Karunanayaka et al., 2007, 2014; Schmithorst et al., 2006]. Using IC time courses, the associated hemodynamic response function (HRF) and the single‐trial response of each network were evaluated using methods described elsewhere [Eichele et al., 2008]. Specifically, this method entails estimating the HRF by forming a convolution matrix of the stimulus onsets and multiplying its pseudoinverse with the IC time course. This was then followed by single‐trial β estimation by fitting a design matrix containing predictors for the onset times of each trial convolved with the estimated HRF in the previous step onto the IC time course. Since the primary olfactory networks showed almost identical temporal behavior during odor + visual and visual‐only conditions, a single composite HRF was estimated for both conditions in each network followed by respective β estimates.

The extended unified structural equation modeling (euSEM) was combined with Group Iterative Multiple Model Estimation (GIMME) to estimate directional influences between the DMN and olfactory network during the odor–visual association paradigm [Gates et al., 2011; Gates and Molenaar, 2012]. The combination of these two techniques is an established effective connectivity estimation technique for olfactory fMRI data [Karunanayaka et al., 2014]. Briefly, this method iteratively identifies the optimal causal structure during a given fMRI paradigm across participants such that, if estimated, would offer the greatest statistical improvement for at least 75% of the individuals in the sample [Gates and Molenaar, 2012].

Using the psychophysiological interaction (PPI), we further investigated whether the connectivity between the DMN and the olfactory network was modulated by the two trial conditions [Cisler et al., 2014; Friston et al., 1997; O'Reilly et al., 2012]. In the PPI linear regression model, the main effects of the task (i.e., task on‐off reference time course) and DMN time course, and the PPI effects between them were added as independent variables along with a constant. A significant interaction effect implied that the connectivity between the DMN and olfactory network was modulated by the two types of trial conditions in the odor‐visual association paradigm.

RESULTS

Olfactory and DMN Network Behavior During the Odor–Visual Association Paradigm

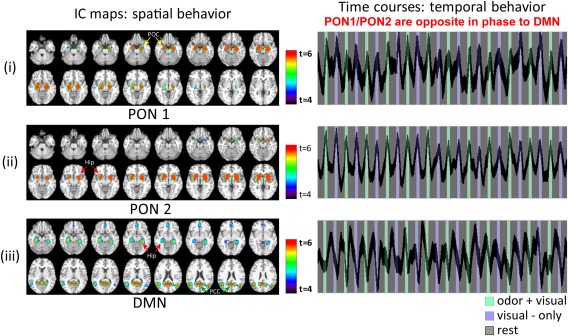

Figure 2 shows two highly task‐related IC maps, identified as primary olfactory networks (PON1 (i) and PON2 (ii)) and the DMN (iii) that subserve the odor–visual association paradigm. The brain regions encompassed in each network are tabulated in Table 1. Previously, using a non‐overlapping data set, we proposed a framework to investigate causal connections of IC maps that subserve this task [Karunanayaka et al., 2014]. In this article, we focus on PON1 and PON2 that show clear distinction between anterior and posterior aspects of the primary olfactory cortex [Karunanayaka et al., 2014]. Since the anterior POC is implicated in deciphering chemical identity of odorants and the posterior POC in mediating perceptual features, these two networks are hypothesized to handle primary olfactory‐related processing [Gottfried, 2010; Karunanayaka et al., 2014]. Additionally, the hippocampus/parahippocampal region is differentially synchronized with the PON1 and the DMN during odor + visual (or visual‐only) trial conditions and interleaved rest conditions [Goodrich‐Hunsaker et al., 2009; Lehn et al., 2013; Royet et al., 2011]. Figure 2(i) and (ii) right shows the corresponding time courses of PON1 and PON2 networks. Of note is the nearly identical and task‐related temporal behaviors of PON1 and PON2 during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. In contrast, the DMN was found to be deactivated during both odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions [Figure 2(iii) right].

Figure 2.

The primary olfactory network (PON1 and PON2) and the Default Mode Network (DMN) behavior during the odor–visual association or four‐intensity paradigm. PON1 (i) and PON2 (ii) showed task‐related behavior for both the odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. The DMN (iii) was deactivated or suppressed and opposite in phase during both odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. In contrast to the PON1 and PON2 behavior, the DMN was active during rest conditions. Hippocampus/parahippocampal cortex was differentially synchronized with PON1 and the DMN during odor + visual (or visual‐only) trials and interleaved rest conditions. DMN, Default Mode Network. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 1.

Brain structures and maximum activation foci for each IC component shown in Figure 2

| Network | L/R | Main brain regions | Peak Z |

MNI coordinates (X,Y,Z) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | R | L | R | |||

| PON1 | L&R | POC | 15 | 7 | −29,−1,−20 | 23,−3,−22 |

| L&R | Hippocampus | 14 | 9 | −25,−15,−20 | 23,−15,−22 | |

| L&R | Putamen | – | 8.2 | – | 31,−13,−8 | |

| L&R | Globus pallidus | 6.3 | 8.4 | −17,−1,−6 | 17,−3,−6 | |

| PON2 | L&R | Putamen/ Ventral striatum | 15.5 | 17.3 | −15,13,2 | 19,5,4 |

| L&R | Globus pallidus | 16.8 | 16.5 | −15,9,0 | 19,5,−2 | |

| L&R | Caudate | 15.5 | 11.2 | −15,13,2 | 15,7,14 | |

| L&R | POC | 10.8 | 13 | −21,9,−14 | 23,5,−12 | |

| L&R | Thalamus | 8.1 | 12..2 | −19,−15,14 | 21,−11,6 | |

| DMN | L&R | Hippocampus | 6.7 | 6.2 | −27,−27,−18 | 29,−33,−12 |

| L&R | Parahippocampus | 7.1 | 7.2 | −31,−31,−18 | 31,−37,−16 | |

| L&R | Medial prefrontal | 5.2 | 5 | −3,55,−8 | 1,53,−10 | |

| L&R | Posterior cingulate | 10.2 | 10.2 | −1,−57,20 | 1,−57,20 | |

| L&R | Inferior parietal | 9.8 | 9.9 | −49,−67,26 | 43,−73,26 | |

The voxel size is 2 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm. PON, Primary Olfactory Network; DMN, Default Mode Network; L, left; R, right.

DMN Deactivation During Odor + Visual and Visual‐Only Trial Conditions in the Odor–Visual Association Paradigm

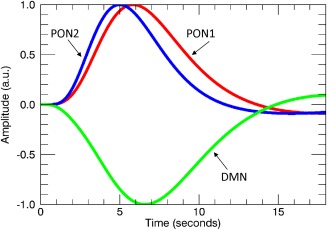

Figure 3 shows the estimated HRF of the DMN for both the odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions in respective PONs. The correlation coefficient of the average time courses of PON1, PON2 and DMN with the on‐off task reference function were: 0.55 (P < 0.00001), 0.85 (P < 0.00001), and −0.48 (P < 0.00001), respectively. As such, the DMN is in opposite phase to both olfactory networks during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. In contrast, our data‐driven methods were unable to estimate the HRF and detect DMN deactivations during visual‐only trial conditions in the no‐odor paradigm. This is because the DMN temporal behavior was mostly unsuppressed and random during visual‐only trial conditions as shown in Figure 4(iii).

Figure 3.

Estimated hemodynamic response functions (HRFs) for each network using IC time‐courses shown in Figure 2 (right hand side) where PON1 and PON2 exhibited almost identical temporal behavior during odor + visual and visual‐only conditions. Similarly, the DMN suppression was almost identical during odor + visual and visual‐only conditions. Therefore, a single composite HRF was estimated for both conditions in each network to investigate phase differences between the olfactory networks and the DMN. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

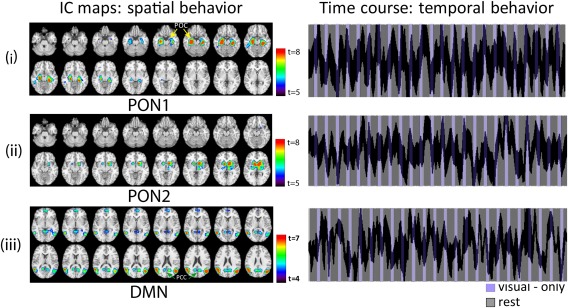

Figure 4.

The primary olfactory PON1 (i) and PON2 (ii) networks during the control no‐odor paradigm. In contrast to the odor–visual association paradigm (Fig. 3), PON1 and PON2 showed high intersubject variability in its temporal behavior and also inconsistent task‐related behavior. The data driven method was unable to estimate the HRF and thus single‐trial β estimates for visual‐only trial conditions in this paradigm. The DMN (iii) behavior during the no‐odor paradigm. In contrast to the odor–visual association paradigm, the DMN behavior persisted across both the rest and visual‐only conditions. The temporal behavior of the DMN was uncoupled from the task on‐off reference time course, and mostly unsuppressed in a random fashion. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The Corresponding Olfactory and DMN Network Behavior During the Control No‐Odor Paradigms

Figure 4 shows the corresponding PON1 (i) and PON2 (ii) spatial as well as temporal behaviors during the no‐odor paradigm. They showed high inter‐subject variability while exhibiting inconsistent task‐related behavior. Therefore, unlike the odor–visual association paradigm, the data‐driven method was unable to estimate the HRF and single‐trial β estimates for visual‐only trial conditions. Figure 4(iii) shows the spatial and temporal behavior of the DMN during the no‐odor paradigm. The DMN activity in this case did not show consistent deactivation, in addition to showing a high degree of inter‐subject variability as indicated by the thickness (std. in a.u.) of the time course.

DMN and Olfactory Network Activity During Odor + Visual and Visual‐Only Trial Conditions in the Odor–Visual Association Paradigm

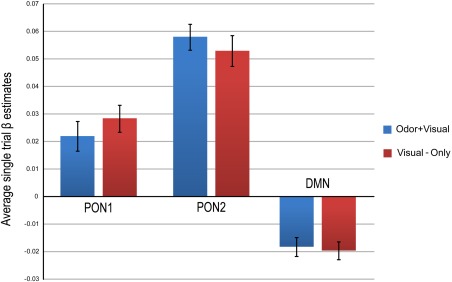

In the odor–visual association paradigm, using a general linear model approach, we have previously demonstrated that the BOLD activation produced by visual‐only trial conditions in olfactory structures (such as the POC, insula, etc.) was nearly identical to that of odor + visual trial conditions [Karunanayaka et al., 2015]. This raised the possibility that activation elicited by visual‐only trials might be caused by preceding odor + visual trial conditions in this paradigm. In the current analysis, the almost identical temporal behavior of PON1 and PON2 during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions provide direct support for this possibility (Fig. 2). Therefore, we quantified the respective network behaviors during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions in terms of average single‐trial β estimates as shown in Figure 5. No significant differences in β estimates were found in any of the three networks between the two trial conditions. Table 2 shows the correlation analyses between the β estimates of odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions in all three networks. These highly significant correlations provide additional evidence that olfactory network activity during visual‐only trial conditions might be influenced by odor–visual pairing causing suppression of the DMN.

Figure 5.

Network responses during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions in terms of average single trial β estimates. The average was first across odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions and then across subjects. All three networks showed no significant differences between average β estimates of odor + visual and visual‐only conditions, implying comparable network behavior during both trial conditions. Overall, PON2 had greater network activation (P < 0.001) when compared with PON1 during both the odor + visual and visual‐only conditions. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients between odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions in PON1, PON2 and the DMN in the odor‐visual association paradigm

| Correlation coefficient between odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions | |

|---|---|

| PON1 | r = 0.78, P <10‐5 |

| PON2 | r = 0.68, P <10‐5 |

| DMN | r = 0.47, P < 0.01 |

PON, Primary Olfactory Network; DMN, Default Mode Network.

Interactions Between the DMN and Olfactory Network in the Odor–Visual Association Paradigm

The extent of the DMN interaction with the olfactory networks was investigated using correlational analyses of single trial β values. Both PON1 and PON2 showed negative correlations with DMN activity during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. However, only the PON1 activity during visual‐only trials showed a significant correlation (r = −0.4, P < 0.03), implying a potential ability of the DMN to impact the olfactory network activity during the performance of this task.

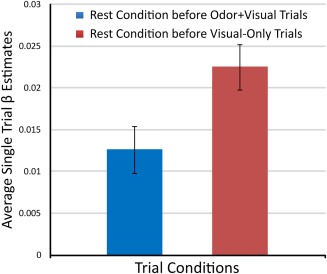

To gauge the extent to which a subject's DMN activity before odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions influence the olfactory network activity, we calculated the correlation coefficient between the time series of the DMN and the inverse task on‐off reference time course (task design with +1 assigned to rest epochs and −1 assigned to stimulus epochs, convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function). We found the DMN is positively correlated (r = 0.487000, P < 0.00001) with the inverse task waveform, implying higher DMN activity during rest conditions. Figure 6 shows higher DMN activity in terms of single trial average β estimates during rest conditions before visual‐only trials when compared with odor + visual trial conditions. Additionally, the DMN activity level in rest conditions before respective trial conditions was not correlated. However, the DMN suppression during odor + visual (r = −0.71, P < 0.0001) and visual‐only (r = −0.67, P < 0.0001) conditions (i.e., β estimates) increased with increasing correlation with the inverse task waveform and the DMN time course. The DMN activity before odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions, both subject‐wise and trial‐wise, was not correlated with activity during respective odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. Taken together, it is highly likely that modulations of cognitive processes such as persistent attention, goal‐oriented attention, working memory, etc., are reflected in the DMN activity during the odor–visual association paradigm.

Figure 6.

The DMN activity in terms of single trial average β estimates during rest conditions before respective odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. The mean activity was significantly different between the two types of trial conditions. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DMN Connectivity with PON1 and PON2 in the Odor–Visual Association Paradigm

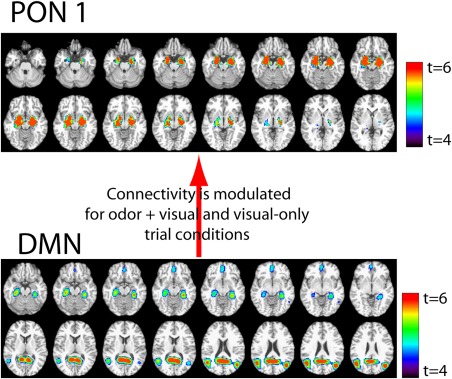

Two separate runs of euSEM were used to investigate the effective connectivity between DMN and PON1 and PON2. Figure 7 shows that a directed connection from the DMN to PON1 was identified in the optimal group model of the euSEM and is presumed to reflect the ability of the DMN to modulate olfactory‐related behavioral responses during this task.

Figure 7.

The optimal euSEM represents the interaction between the DMN and PON1 during the odor–visual association paradigm. The subsequent PPI analysis revealed that this connectivity is modulated for odor + visual and visual only trial conditions. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The PPI analysis revealed that the connectivity between the DMN and PON1 was significantly different between odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions (P < 0.002). As such, it appears that the DMN tends to increase the contrast between the effects of the two trial conditions on PON1. Since all participants correctly identified the presence or absence of an odor in respective trial conditions (>95%), it is reasonable to postulate that the modulated connectivity between the DMN and olfactory network might be influencing behavioral responses which are olfactory in nature during the odor–visual association paradigm.

DISCUSSION

The odor–visual association paradigm produced similar levels of DMN deactivation during both the odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions and can be reasonably interpreted as an indirect measure of odor detectability. This is because participants had to correctly identify the presence or absence of an odor during respective odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. On the other hand, differences in the “level” of DMN deactivation could be interpreted as differences in “influence” or “modulation” between the DMN and olfactory network. The results of single trial β estimates, however, did not provide evidence for modulatory effects. Nevertheless, the results of the euSEM and PPI analyses supported an interaction between the DMN and PON1, which was modulated by odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. This DMN behavior during the odor–visual association paradigm was in stark contrast to the no‐odor paradigm. Our data driven method failed to detect systematic DMN deactivations by the visual‐only trial condition in the no‐odor paradigm. Therefore, results of this study provide support for different levels of DMN deactivations between visual‐only trial conditions in the odor–visual association and no‐odor paradigms. Taken together, these observations suggest that cognitive resources needed for successful odor–visual pairing may cause systematic DMN deactivations by visual‐only trial conditions in the odor–visual association paradigm, compared with the visual‐only trials in the no‐odor paradigm.

During interleaved rest conditions, the DMN was active and strongly correlated with the task on‐off reference time course. Additionally, the preceding rest condition DMN activity was significantly different between odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. This DMN activity before odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions, however, was not correlated with activity during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. The euSEM and PPI results provided evidence for a DMN involvement in modulating olfactory network activity and related behavioral responses. As such, the interaction between the DMN and olfactory networks seems to be dynamic and responsive in nature. This adds new information to a previously published study where it was shown that resting state brain activity accounts for a significant fraction of the variability in measured event‐related BOLD responses and that resting state and task‐related activity are linearly superimposed in the human brain [Fox et al., 2007].

Our data driven approach to use IC time courses to estimate the HRF and subsequent responses of event‐related olfactory fMRI stimulation is innovative. In addition, it provided a basis to highlight the functional relevance of DMN deactivations during olfactory processing at many levels, which are in line with other sensory and cognitive tasks where DMN modulations have been reported [Arfanakis et al., 2000; Binder et al., 1999; Frith et al., 1991; Greicius and Menon, 2004; Haxby et al., 1994]. The results of this study clearly demonstrated a modulation in connectivity between the DMN and olfactory network and raised the possibility that DMN interactions might be influencing task‐evoked activity, and thus indirectly behavioral responses [Sadaghiani et al., 2015]. Such information is critically important because most task‐related topographies of brain networks are recapitulated during resting state networks (RSNs), suggesting that RSNs are sculpted from the history of brain region co‐activation as part of functional networks [Buckner et al., 2008; Deco and Corbetta, 2011; Deco et al., 2011; Patton and Fulton, 1960; Shulman et al., 1997]. Furthermore, a tight functional connection between the DMN and olfactory network is a clear indication that olfactory processing is multidimensional and relies on top‐down processing [Zelano et al., 2011; Olofsson et al., 2012]. Thus, the overall findings of this study provided both new insight into the selectivity and dynamics of the olfactory network in terms of an interaction with the DMN and a novel approach to investigate interactions of RSNs during olfactory processing in the human brain [Andrews‐Hanna, 2012; Arfanakis et al., 2000]. Below we focus on additional details and insight provided by the current study results.

DMN Behavior During Odor + Visual and Visual‐Only Trial Conditions

Task‐induced deactivation of the DMN may signal the suppression of attention to one's own thoughts or feelings and promote the allocation of mental and neural resources to task‐related stimuli [Anticevic et al., 2012; Whitfield‐Gabrieli et al., 2009]. When forming associations between multiple stimuli, DMN deactivations may indicate resource allocation during memory encoding [Chai et al., 2014b]. Additionally, higher working memory demands generally result in both increased activation in cognitive control regions (e.g., prefrontal cortex [PFC]) and greater DMN deactivations [McKiernan et al., 2003; Miller and Cummings, 2007; Shulman et al., 1997]. From this perspective, the DMN deactivations during visual‐only trial conditions in the odor–visual association paradigm further support the notion that rapid and transient associative learning mechanisms are involved in this paradigm.

In line with forming associations, we have already shown that BOLD activity elicited by visual‐only trials in olfactory structures is in fact dependent on and modulated by odor‐intensity variations of preceding odor + visual trials [Karunanayaka et al., 2015]. Similarly, we showed that visual‐only trials elicited higher BOLD activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) when compared with odor + visual trials [Karunanayaka et al., 2015]. Therefore, it is highly likely that visual‐only trial conditions are subserved by cognitive processes such as persistent attention, goal‐oriented attention and working memory as part of the odor–visual pairing process. As such, the DMN deactivation caused by visual‐only trial conditions in the odor–visual association paradigm may be due to cross‐modal activation or due to a learned expectation of the olfactory network [Karunanayaka et al., 2015]. Our previous publications have highlighted the failure of visual‐only trials in the no‐odor paradigm to produce significant visually‐evoked activity in olfactory structures [Karunanayaka et al., 2014, 2015]. The absence of consistent DMN deactivation during visual‐only trials in the no‐odor paradigm is, therefore, another indication that subjects might be utilizing different cognitive strategies in the respective paradigms [Lepage et al., 1998]. For example, in the no‐odor paradigm, after presentation of several visual cues, subjects might “figure out” stimulation structure and adopt a strategy that is different to the one in the odor–visual association paradigm.

It is possible that the visual cue itself may induce search behavior for the presence of an odorant activating olfactory structures such as the POC. The no‐odor paradigm, where subjects were thought to utilize different cognitive strategies, does not completely invalidate the possibility that visual‐only trials in the odor–visual association paradigm are facilitating search behavior. Therefore, further work will be required to describe the time course of this associative behavior of visual‐only trials and how the nature and quality of visual cues would influence this effect.

Active sniffing in the absence of an odorant is also capable of inducing BOLD signal change in the POC [Mainland and Sobel, 2006; Sobel et al., 1998]. Our experimental protocol, however, included specific instructions (see Supporting Information) to study participants not to sniff during both fMRI paradigms and to follow their normal breathing patterns. Before fMRI scanning, subjects were also trained to perform the task without sniffing and the sniffing behavior was monitored and recorded during the execution of paradigms using a chest belt [Wang et al., 2013]. Button responses and respiration patterns were then used to identify and exclude subjects with irregular respiration patterns and poor task performance. Thus, it seems highly unlikely that sniffing behavior was significantly contributing to the observed activation during visual‐only trial conditions in the odor–visual association paradigm.

Interplay Between the DMN and the Olfactory Network

The degree of DMN suppression has been associated with better memory formation in healthy subjects [Daselaar et al., 2004, 2009]. This is because the hippocampus, which is functionally connected to the DMN through posteromedial regions (extending from the posterior cingulate to precuneus and lateral parietal regions), is deactivated and considered essential for successful memory formation [Greicius et al., 2004; Kahn et al., 2008; Sperling et al., 2003; Vincent et al., 2006]. Additionally, the functional synchrony in the DMN may be differentially modulated for memory encoding and retrieval by reciprocally coordinating activities in brain regions within the DMN [Daselaar et al., 2003, 2006; Miller et al., 2008; Pihlajamaki et al., 2008]. Since PON1 includes the hippocampus, we argue that PON1's anti‐correlated behavior to that of the DMN accounts for encoding and retrieval mechanisms that may underlie odor–visual pairing mechanisms in the odor–visual association paradigm [Eichenbaum et al., 1996, 2007; Gottfried et al., 2004; Sperling et al., 2003; Yeshurun et al., 2009]. Additionally, PON1 activity was negatively correlated with DMN activation, highlighting its potential importance in terms of cognitive demand during odor processing. However, it should be noted that the negative correlation was not corrected for multiple comparisons. This behavior of PON1 is also in agreement with previous findings where the POC (part of PON1) was implicated in optimized sensory associations to incorporate cognitive and experiential factors when constructing odor object percepts [Gottfried, 2010]. Similarly, a plethora of evidence points to the involvement of the ventral striatum, a main structure in PON2, in certain forms of associative learning [Cerf‐Ducastel and Murphy, 2006; Gottfried et al., 2002; Livingston and Horny, 1978]. Therefore, brain structures encompassed in PON1 and PON2, and their temporal and connectivity patterns with respect to the DMN behavior during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions, appear to underscore the DMN's significance in odor–visual association during olfactory processing [Gottfried, 2010].

The DMN and olfactory network showed differential connectivity during odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions (Fig. 7). This modulatory behavior signifies the importance of DMN's influence for olfactory processing and/or odor–visual associations. Since participants almost correctly identified respective trial conditions, the modulated connectivity between the DMN and PON1 may be interpreted as relating to olfactory‐related behavioral responses. Such functional connections are important because anatomic, as well as functional, imaging studies have repeatedly shown a tight connection between the DMN and the temporal lobe hippocampal memory system, which is part of PON1 [Kobayashi and Amaral, 2007]. In sum, the DMN behavior during the odor–visual association paradigm provided a mechanistic avenue to assess and quantify associative links such as odor–visual pairing that may utilize certain memory processes unique to olfaction.

Study Limitations

Some participants in our study completed the odor–visual association paradigm before the no‐odor paradigm. One can, therefore, expect carryover effects such as POC activation and DMN deactivation during the no‐odor paradigm. Previous work, however, suggested that odor–visual pairing is rapid and transient, making the carryover effect negligible in the current experimental design [Karunanayaka et al., 2015]. The sample size differences between the two paradigms is another study limitation, although, the number of participants in the no‐odor paradigm fell within the optimal sample size range for an imaging study [Friston, 2012]. Findings of this study can be further strengthened by using non‐lexical or incongruent visual cues that have been paired with an odorant in prior encoding trial conditions. Implementing experimental designs with additional internal control conditions may also provide the opportunity for more straightforward comparisons between odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions. For example, a null trial with a different visual cue might be helpful in controlling for pure attention‐induced variations during this paradigm. The four‐odor intensity paradigm had alternating odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions and, therefore, a randomized design may be better suited to delineate ordering effects in current experiments. Event‐related fMRI designs with long inter‐stimulus intervals (ISI) can also facilitate better differentiation between cognitive processes that subserve odor–visual pairing and after effects of olfactory stimulation. Finally, by increasing the number of trials for each odor intensity within the odor–visual association paradigm can provide an avenue to investigate how the fMRI signal varies with odor intensity for both the odor + visual and visual‐only trial conditions.

New Frontiers in DMN Deactivations During Olfactory Processing

Further characterization of these networks in healthy subjects will be important to elucidate how olfactory processing is modulated by the DMN and its differences in subjects with impaired olfaction. Extensions of this work will also help understand the mechanisms of top‐down modulations in olfaction and potentially how impaired olfaction is connected to neurodegenerative disorders such as the Alzheimer's Disease (AD) [Devanand et al., 2000, 2010; Serby et al., 1991]. The DMN consists of subnetworks that have different spatial relationship with the POC, in terms of both Euclidean distance and structural connectivity [Di and Biswal, 2014]. How these network activities are modulated during olfactory perception and monitoring will be of great importance and should be investigated in future research. The findings of this study will also have implications in the interpretation of olfactory tasks with no measure of performance or attention. Constructing a measure which will gauge subject attention to stimuli during olfactory processing by quantifying the interaction (or lack thereof) between the DMN and the olfactory network may be possible. Answers to such questions will have implications for task design and may provide methods with which to quantify the task‐demands and subject‐engagement in terms of interruptions to the (presumably) cognitive processes mediated by the DMN.

Summary and Conclusions

The results of this study provided novel evidence that olfactory information processing deactivates the DMN, suggesting that olfactory perception may draw cognitive, attentional, and memory resources during odor processing [Gottfried, 2010]. The DMN exhibited modulated connectivity signifying the potential importance of the DMN's influence to predict subsequent olfactory‐related task‐evoked brain responses and behavioral performances. From a basic neuroscience perspective, quantifying the strength and, possibly, the efficacy of such DMN deactivations are important because this approach will help in understanding and assessing the types of cognitive processes involved in top‐down projections allowing the olfactory network to process odor information in many different contexts [Dayan and Balleine, 2002; Gottfried and Dolan, 2003; Li et al., 2006; Osterbauer et al., 2005; Rabin and Cain, 1984; Stevenson, 2001; Stevenson and Oaten, 2008; Zhou et al., 2012]. In this regard, complementary approaches such as novel olfactory fMRI paradigms and advanced network modeling approaches such as ours can provide a powerful cross‐disciplinary approach to further stimulate this exciting area of basic and clinical neuroscience.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by the Leader Family Foundation, a grant from the U.S. National Institute of Aging (R01‐AG027771) and the Department of Radiology, Penn State College of Medicine. The authors report no conflict of interest. D.A.W. was funded by NIDCD: R01‐DC03906.

REFERENCES

- Allen W (1936): Studies on the level of anesthesia for the olfactory and trigeminal respiratory reflexes in dogs and rabbits. Am J Physiol 115:579–587. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews‐Hanna JR (2012): The brain's default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. Neuroscientist 18:251–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Cole MW, Murray JD, Corlett PR, Wang XJ, Krystal JH (2012): The role of default network deactivation in cognition and disease. Trends Cogn Sci 16:584–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arfanakis K, Cordes D, Haughton VM, Moritz CH, Quigley MA, Meyerand ME (2000): Combining independent component analysis and correlation analysis to probe interregional connectivity in fMRI task activation datasets. Magn Reson Imaging 18:921–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Barnes G, Chen C‐C, Daunizeau J, Flandin G, Friston K, Kiebel S, Kilner J, Litvak V, Moran R, Penny W, Rosa M, Stephan K, Gitelman D, Henson R, Hutton C, Glauche V, Mattout J, Phillips C (2009): SPM8 Manual. London, UK: Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging Institute of Neurology, UCL. p 475.

- Barber AD, Caffo BS, Pekar JJ, Mostofsky SH (2013): Developmental changes in within‐ and between‐network connectivity between late childhood and adulthood. Neuropsychologia 51:156–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR (2012): Task‐induced deactivation and the “resting” state. Neuroimage 62:1086–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS (1995): Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo‐planar MRI. Magn Reson Med 34:537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Frost JA, Hammeke TA, Bellgowan PS, Rao SM, Cox RW (1999): Conceptual processing during the conscious resting state. A functional MRI study. J Cogn Neurosci 11:80–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Andrews‐Hanna JR, Schacter DL (2008): The brain's default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1124:1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ (2001): A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 14:140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Kiehl KA, Pearlson GD (2008): Modulation of temporally coherent brain networks estimated using ICA at rest and during cognitive tasks. Hum Brain Mapp 29:828–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerf‐Ducastel B, Murphy C (2006): Neural substrates of cross‐modal olfactory recognition memory: An fMRI study. Neuroimage 31:386–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai XJ, Ofen N, Gabrieli JD, Whitfield‐Gabrieli S (2014a): Development of deactivation of the default‐mode network during episodic memory formation. Neuroimage 84:932–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai XJ, Ofen N, Gabrieli JD, Whitfield‐Gabrieli S (2014b): Selective development of anticorrelated networks in the intrinsic functional organization of the human brain. J Cogn Neurosci 26:501–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Bush K, Steele JS (2014): A comparison of statistical methods for detecting context‐modulated functional connectivity in fMRI. Neuroimage 84:1042–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Veltman DJ, Rombouts SA, Raaijmakers JG, Jonker C (2003): Neuroanatomical correlates of episodic encoding and retrieval in young and elderly subjects. Brain J Neurol 126:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Prince SE, Cabeza R (2004): When less means more: Deactivations during encoding that predict subsequent memory. Neuroimage 23:921–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Dobbins IG, Madden DJ, Cabeza R (2006): Effects of healthy aging on hippocampal and rhinal memory functions: An event‐related fMRI study. Cerebr Cortex 16:1771–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Prince SE, Dennis NA, Hayes SM, Kim H, Cabeza R (2009): Posterior midline and ventral parietal activity is associated with retrieval success and encoding failure. Front Hum Neurosci 3:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P, Balleine BW (2002): Reward, motivation, and reinforcement learning. Neuron 36:285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deco G, Corbetta M (2011): The dynamical balance of the brain at rest. Neuroscientist 17:107–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deco G, Jirsa VK, McIntosh AR (2011): Emerging concepts for the dynamical organization of resting‐state activity in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 12:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanand DP, Michaels‐Marston KS, Liu X, Pelton GH, Padilla M, Marder K, Bell K, Stern Y, Mayeux R (2000): Olfactory deficits in patients with mild cognitive impairment predict Alzheimer's disease at follow‐up. Am J Psychiatry 157:1399–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanand DP, Tabert MH, Cuasay K, Manly JJ, Schupf N, Brickman AM, Andrews H, Brown TR, DeCarli C, Mayeux R (2010): Olfactory identification deficits and MCI in a multi‐ethnic elderly community sample. Neurobiol Aging 31:1593–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di X, Biswal BB (2014): Modulatory interactions between the default mode network and task positive networks in resting‐state. Peer J 2:e367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, editor. (2000): The Odor Threshold Test. Administration Manual. Haddon Heights, NJ: Sensonics, Inc (OTT). [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M (1984): Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: A standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav 32:489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Smith R, McKeown DA, Raj J (1994): Tests of human olfactory function: Principal components analysis suggests that most measure a common source of variance. Percept Psychophys 56:701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichele T, Debener S, Calhoun VD, Specht K, Engel AK, Hugdahl K, von Cramon DY, Ullsperger M (2008): Prediction of human errors by maladaptive changes in event‐related brain networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:6173–6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Schoenbaum G, Young B, Bunsey M (1996): Functional organization of the hippocampal memory system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:13500–13507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C (2007): The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 30:123–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME (2007): Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:700–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME (2005): The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:9673–9678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Zacks JM, Raichle ME (2006): Coherent spontaneous activity accounts for trial‐to‐trial variability in human evoked brain responses. Nat Neurosci 9:23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Raichle ME (2007): Intrinsic fluctuations within cortical systems account for intertrial variability in human behavior. Neuron 56:171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston K (2012): Ten ironic rules for non‐statistical reviewers. Neuroimage 61:1300–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Buechel C, Fink GR, Morris J, Rolls E, Dolan RJ (1997): Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage 6:218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Friston KJ, Liddle PF, Frackowiak RS (1991): A PET study of word finding. Neuropsychologia 29:1137–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates KM, Molenaar PC (2012): Group search algorithm recovers effective connectivity maps for individuals in homogeneous and heterogeneous samples. NeuroImage 63:310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates KM, Molenaar PC, Hillary FG, Slobounov S (2011): Extended unified SEM approach for modeling event‐related fMRI data. NeuroImage 54:1151–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J, Barros‐Loscertales A, Pulvermuller F, Meseguer V, Sanjuan A, Belloch V, Avila C (2006): Reading cinnamon activates olfactory brain regions. Neuroimage 32:906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich‐Hunsaker NJ, Gilbert PE, Hopkins RO (2009): The role of the human hippocampus in odor‐place associative memory. Chem Senses 34:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA (2010): Central mechanisms of odour object perception. Nat Rev Neurosci 11:628–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA, O'Doherty J, Dolan RJ (2002): Appetitive and aversive olfactory learning in humans studied using event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci 22:10829–10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA, Dolan RJ (2003): The nose smells what the eye sees: Crossmodal visual facilitation of human olfactory perception. Neuron 39:375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA, Smith AP, Rugg MD, Dolan RJ (2004): Remembrance of odors past: Human olfactory cortex in cross‐modal recognition memory. Neuron 42:687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Menon V (2004): Default‐mode activity during a passive sensory task: Uncoupled from deactivation but impacting activation. J Cogn Neurosci 16:1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V (2003): Functional connectivity in the resting brain: A network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:253–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V (2004): Default‐mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from healthy aging: Evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:4637–4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF (2009): Resting‐state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cerebr Cortex 19:72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld R, Wang J, Meadowcroft MD, Ansel I, Sun X, Eslinger PJ, Connor JR, Smith MB, Yang QX (2005): The responsiveness of fMRI signal to odor concentration In: Chemical Senses. Sarasota, FL: pp 237–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson M, Tokoglu F, Sun Z, Schafer RJ, Skudlarski P, Gore JC, Constable RT (2006): Connectivity‐behavior analysis reveals that functional connectivity between left BA39 and Broca's area varies with reading ability. Neuroimage 31:513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Horwitz B, Ungerleider LG, Maisog JM, Pietrini P, Grady CL (1994): The functional organization of human extrastriate cortex: A PET‐rCBF study of selective attention to faces and locations. J Neurosci 14:6336–6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L (1978): The olfactory cortex and the ventral striatum In: KE Livingston, O Horny, editors. The Limbic Mechanisms. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn I, Andrews‐Hanna JR, Vincent JL, Snyder AZ, Buckner RL (2008): Distinct cortical anatomy linked to subregions of the medial temporal lobe revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 100:129–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunanayaka PR, Holland SK, Schmithorst VJ, Solodkin A, Chen EE, Szaflarski JP, Plante E (2007): Age‐related connectivity changes in fMRI data from children listening to stories. Neuroimage 34:349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunanayaka P, Schmithorst VJ, Vannest J, Szaflarski JP, Plante E, Holland SK (2010): A group independent component analysis of covert verb generation in children: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroimage 51:472–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunanayaka P, Eslinger PJ, Wang J‐L, Weitekamp CW, Molitoris S, Gates KM, Molenaar PC, Yang QX (2014): Networks involved in olfaction and their dynamics using independent component analysis and unified structural equation modeling. Hum Brain Mapp 35:2055–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunanayaka P, Wilson AD, Vasavada M, Wang J, Tobia MJ, Martinez B, Kong L, Eslinger PJ, Yang QX (2015): Rapidly acquired multisensory association in the olfactory cortex. Brain Behav 5:e00390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Amaral DG (2007): Macaque monkey retrosplenial cortex: III. Cortical efferents. J Comp Neurol 502:810–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehn H, Kjonigsen LJ, Kjelvik G, Haberg AK (2013): Hippocampal involvement in retrieval of odor vs. object memories. Hippocampus 23:122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage M, Habib R, Tulving E (1998): Hippocampal PET activations of memory encoding and retrieval: The HIPER model. Hippocampus 8:313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Luxenberg E, Parrish T, Gottfried JA (2006): Learning to smell the roses: Experience‐dependent neural plasticity in human piriform and orbitofrontal cortices. Neuron 52:1097–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Wu X, Fleisher AS, Reiman EM, Chen K, Yao L (2012): Attention‐related networks in Alzheimer's disease: A resting functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 33:1076–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston KE, Horny O (1978): The Limbic Mechanisms. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maaswinkel H, Li L (2003): Olfactory input increases visual sensitivity in zebrafish: A possible function for the terminal nerve and dopaminergic interplexiform cells. J Exp Biol 206:2201–2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainland J, Sobel N (2006): The sniff is part of the olfactory percept. Chem Senses 31:181–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez B, Wang J, Karunanayaka P, Yang QX (2015): Men are more susceptible to age‐related central olfactory functional decline: An Olfactory fMRI Study. In: AChemS XXXVII. Hyatt Regency: Coconut Point Bonita Springs, Florida.

- McKiernan KA, Kaufman JN, Kucera‐Thompson J, Binder JR (2003): A parametric manipulation of factors affecting task‐induced deactivation in functional neuroimaging. J Cogn Neurosci 15:394–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BL, Cummings JL (2007): The Human Frontal Lobes, 2nd ed New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, Fenstermacher E, Bates J, Blacker D, Sperling RA, Dickerson BC (2008): Hippocampal activation in adults with mild cognitive impairment predicts subsequent cognitive decline. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79:630–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DJ, Kahn BE, Knasko SC (1995): There's something in the air: Effects of congruent or incongruent ambient odor on consumer decision making. J Consum Res 22:229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson JK, Bowman NE, Khatibi K, Gottfried JA (2012): A time‐based account of the perception of odor objects and valences. Psychol Sci 23:1224–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly JX, Woolrich MW, Behrens TE, Smith SM, Johansen‐Berg H (2012): Tools of the trade: Psychophysiological interactions and functional connectivity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 7:604–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterbauer RA, Matthews PM, Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Hansen PC, Calvert GA (2005): Color of scents: Chromatic stimuli modulate odor responses in the human brain. J Neurophysiol 93:3434–3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton HD, editor. (1960): Taste, olfaction and visceral sensation In: Fulton TCR, editor. Medical Physiology and Biophysics, Chapter 16. Philadelphia: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Pihlajamaki M, DePeau KM, Blacker D, Sperling RA (2008): Impaired medial temporal repetition suppression is related to failure of parietal deactivation in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 16:283–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin MD, Cain WS (1984): Odor recognition: Familiarity, identifiability, and encoding consistency. J Exp Psychol 10:316–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, Snyder AZ (2007): A default mode of brain function: A brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage 37:1083–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL (2001): A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP, Morin‐Audebrand L, Cerf‐Ducastel B, Haase L, Issanchou S, Murphy C, Fonlupt P, Sulmont‐Rosse C, Plailly J (2011): True and false recognition memories of odors induce distinct neural signatures. Front Hum Neurosci 5:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP, Saive AL, Plailly J, Veyrac A (2015): Etreparfumeur, une questiondeprédispositionoud'entraînement? In: Jaquet C, editor. Contemporary Art Olfactory. Paris: Classiques Garnier; pp 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sadaghiani S, Poline JB, Kleinschmidt A, D'Esposito M (2015): Ongoing dynamics in large‐scale functional connectivity predict perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:8463–8468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saive AL, Royet JP, Plailly J (2014): A review on the neural bases of episodic odor memory: From laboratory‐based to autobiographical approaches. Front Behav Neurosci 8:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savic I, Gulyas B, Larsson M, Roland P (2000): Olfactory functions are mediated by parallel and hierarchical processing. Neuron 26:735–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmithorst VJ, Holland SK, Plante E (2006): Cognitive modules utilized for narrative comprehension in children: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroimage 29:254–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneuric A, Durand K, Jiang T, Baudouin JY, Schaal B (2010): The nose tells it to the eyes: Crossmodal associations between olfaction and vision. Perception 39:1541–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo HS, Roidl E, Müller F, Negoias S (2010): Odors enhance visual attention to congruent objects. Appetite 54:544–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serby M, Larson P, Kalkstein D (1991): The nature and course of olfactory deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 148:357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman GL, Fiez JA, Corbetta M, Buckner RL, Miezin FM, Raichle ME, Petersen SE (1997): Common blood flow changes across visual tasks: II. Decreases in cerebral cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 9:648–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel N, Prabhakaran V, Hartley CA, Desmond JE, Zhao Z, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD, Sullivan EV (1998): Odorant‐induced and sniff‐induced activation in the cerebellum of the human. J Neurosci 18:8990–9001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Bates JF, Chua EF, Cocchiarella AJ, Rentz DM, Rosen BR, Schacter DL, Albert MS (2003): fMRI studies of associative encoding in young and elderly controls and mild Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RJ (2001): Perceptual learning with odors: Implications for psychological accounts of odor quality perception. Psychon Bull Rev 8:708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RJ, Oaten M (2008): The effect of appropriate and inappropriate stimulus color on odor discrimination. Percept Psychophys 70:640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Snyder AZ, Fox MD, Shannon BJ, Andrews JR, Raichle ME, Buckner RL (2006): Coherent spontaneous activity identifies a hippocampal‐parietal memory network. J Neurophysiol 96:3517–3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Eslinger PJ, Doty RL, Zimmerman EK, Grunfeld R, Sun X, Meadowcroft MD, Connor JR, Price JL, Smith MB, Yang QX (2010): Olfactory deficit detected by fMRI in early Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 1357:184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xiaoyu S, Weitekamp CW, Karunanayaka P, Yang QX (2011): The implication of respiratory patterns on olfactory bold signal. In: AChemS xxxIII. St. Pete Beach, Florida.

- Wang J, Sun X, Yang QX (2013): Methods for olfactory fMRI studies: Implication of respiration. Hum Brain Mapp [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X, Liu Y, Yao L, Ding M (2013): Top‐down regulation of default mode activity in spatial visual attention. J Neurosci 33:6444–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield‐Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV, McCarley RW, Shenton ME, Green AI, Nieto‐Castanon A, LaViolette P, Wojcik J, Gabrieli JD, Seidman LJ (2009): Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first‐degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:1279–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DA, Stevenson RJ (2006): Learning to Smell. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yeshurun Y, Lapid H, Dudai Y, Sobel N (2009): The privileged brain representation of first olfactory associations. Curr Biol: CB 19:1869–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelano C, Mohanty A, Gottfried JA (2011): Olfactory predictive codes and stimulus templates in piriform cortex. Neuron 72:178–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Zhang X, Chen J, Wang L, Chen D (2012): Nostril‐specific olfactory modulation of visual perception in binocular rivalry. J Neurosci 32:17225–17229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information