Abstract

Background

Lesbian and bisexual women are at greater risk of being obese than heterosexual women, however, there is little research on dietary intake among lesbian and bisexual women.

Objective

This study estimated differences in dietary quality and intake during adulthood comparing heterosexual women to lesbian and bisexual women.

Design

Biennial mailed questionnaires were used to collect data from a cohort between 1991-2011. Heterosexual-identified women were the reference group.

Participants/Setting

Over 100,000 female registered nurses in the United States, ages 24-44 years were recruited in 1989 to participate in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Over 90% of the original sample are currently active in the study. About 1.3% identified as lesbian or bisexual.

Main outcome measures

Dietary measures were calculated from a 133-item food frequency questionnaire administered every four years. Measures included diet quality (Alternative Healthy Eating Index-2010 (AHEI-2010) and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension); calorie, fat, and fiber intake; and glycemic load and index.

Statistical analyses

Multivariable adjusted repeated measures linear regression models were fit.

Results

On average, lesbian and bisexual women reported better diet quality (p<0.001) and diets lower in glycemic index (p<0.001) than heterosexual women. In the whole cohort, diet quality scores increased as participants aged and were lower among women living in rural compared to urban regions. Comparisons in dietary intake across sexual orientation groups were generally similar across age and rurality status. However, differences between lesbian and heterosexual women in AHEI-2010 were larger during younger compared to older ages, suggesting that diet quality estimates among sexual orientation groups converged as women aged.

Conclusion

Lesbian and bisexual women reported higher diet quality than heterosexuals. More research examining how diet effects risk for chronic conditions, such as diabetes, among sexual minorities is needed. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, disordered eating behaviors, and psychosocial and minority stress should be explored as potential contributors to higher rates of obesity among sexual minority women.

Keywords: sexual orientation, diet, disparities, women’s health, epidemiology

Introduction

A growing body of research shows that lesbian and bisexual women are at greater risk than heterosexual women for numerous health risks including smoking,1-7 alcohol use,1-4,6,8 and poor mental health.3,5,9-11 Less research has been conducted with regard to weight-related health, although evidence suggests that lesbian and bisexual women are at greater risk than heterosexual women for overweight and obesity,3,6,12-22 which are major risk factors for chronic health conditions including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers.23 However, little is known about the modifiable behaviors associated with excess weight gain over the life course, such as poor dietary quality, among lesbian and bisexual women.24

The few existing studies examining sexual orientation differences in dietary intake have primarily assessed fruit and vegetable consumption.4,6,13 While some of these studies have found no differences in fruit and vegetable consumption across sexual orientation, one study found that lesbian women older than 50 years of age were less likely to meet the recommendation of five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day than their heterosexual counterparts in the same age range.4,6,13 The paucity of dietary exposure measures assessed in these studies has limited our understanding of diet as a potentially modifiable risk factor to address overweight and obesity, as well as obesity-related conditions, among lesbian and bisexual women.

A recent study among college students assessed a variety of eating behaviors including consumption of fruits and vegetables, soda, diet soda, restaurant food, fast food, and breakfast and found a broad array of disparities across sexual orientation.15 Findings from this study indicated that bisexual women were more likely than heterosexual women to not eat breakfast, to eat out at restaurants, to engage in unhealthy weight control behaviors (including laxative use, vomiting, and diet pills) and binge eating, but they were less likely than heterosexual women to eat fast food. Fewer differences between lesbian and heterosexual women were found, but lesbian women were more likely than their heterosexual peers to eat out at restaurants and to binge eat. These findings suggest the need for more comprehensive assessments of dietary intake among lesbian and bisexual women in order to gain a better understanding of factors that may contribute to the documented disparity in overweight and obesity.

Moreover, existing research on dietary intake among lesbian and bisexual women has primarily relied on cross-sectional data,3,4,6,12-20,25 resulting in little understanding of dietary patterns across sexual orientation groups throughout the life course. Information on how dietary intake may vary over the life course and whether dietary patterns differ across sexual orientation groups is important for developing effective and appropriate interventions. Differing dietary patterns may further elucidate critical life-course periods when interventions need to be focused to promote healthy living and healthy weight maintenance and to address health disparities.

In addition to the methodological limitations of few dietary measures and cross-sectional data, there has been little work that has examined whether sexual orientation differences in dietary intake is modified by sociodemographic factors such as age or rural living. A previous Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) analysis found that lesbian and bisexual women experienced more pronounced weight gain from ages 25-59 years than heterosexual women.26 Building on this study, it was hypothesized that weight-related behavioral factors, such as diet quality, might also vary by age with greater deterioration in diet quality over time among lesbian and bisexual women than among heterosexual women.

Generally, living in rural areas is associated with greater prevalence of obesity.27-29 A small body of research suggests that living in rural areas may also have further adverse implications on the health of lesbian and bisexual women in that they experience less social support and lack of community, as well as more health risk behaviors.30-32 As a result, rurality has been emphasized by the Institute of Medicine as an area in need of further exploration with regard to sexual orientation-related health disparities.24 Recently, a study examining lesbian women’s weight status and dietary behaviors found higher body mass index (BMI) and diets higher in protein among rural-residing lesbian women than urban-residing lesbian women.33 However, questions remain about whether differences between heterosexual and sexual minority women in dietary quality and intake are similar or different by rurality status.

To address the literature gaps described above, this study examined sexual orientation differences in dietary quality and intake among women ages 26-67 years participating in the longitudinal NHSII cohort. Based on evidence that lesbian and bisexual women are more likely to be overweight and obese,3,6,12-20 and more specifically, women in NHSII,26 it was hypothesized that lesbian and bisexual women would have less healthy diets than heterosexual women throughout adulthood as a possible contributing behavioral factor for documented weight status disparities. In addition, the study tested for effect measure modification by age to examine if sexual-orientation patterns in diet were consistent or different across 5-year age periods. It was further hypothesized that rural living status would modify the relationship between sexual orientation and dietary quality and intake.

Methods

Study Population

The NHSII was established in 1989 and is a prospective cohort study of female registered nurses living in 15 states in the United States who were 24-44 years of age in 1989.34 Nurses were recruited from state nursing boards based on age and sex. The baseline questionnaire was mailed to 517,000 women, of which 123,000 responded (24%). After excluding incomplete surveys and those who were ineligible (including those who reported breast cancer), 116,671 remained in the cohort. Biennial mailed questionnaires were used for follow-up. The follow-up rate exceeded 90% for every two-year period, and the overall follow-up rate was 93.6% between 1989 and 2011. Participants who completed a survey in 2011 were more likely to be white (93% versus 91%; p=<0.001), to live in the Midwest (34% versus 33%; p=0.02), and less likely to have a household income in 2001 greater than $50,000/year (89% versus 90%; p=<0.001) compared to baseline participants. There were no differences between baseline and active participants in rurality status (24% for both; p=0.08). In the current study sample, heterosexual women had an age-standardized mean BMI over all waves of data included in the study of 26.9 (SD=6.3), while lesbian and bisexual women’s mean BMIs were 28.5 (SD=6.8) and 28.9 (SD=8.0), respectively (p<0.001).

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation was assessed in 1995 and 2009 using a sexual orientation identity question that stated, “Whether or not you are currently sexually active, what is your sexual orientation or identity? (Please choose one answer).”35 Response options included “Heterosexual,” “Lesbian, gay, or homosexual,” “Bisexual,” “None of these,” and “Prefer not to answer.” For these analyses, reported sexual orientation in 2009 was used, except where there was missing information (i.e., not identifying as heterosexual, lesbian, or bisexual), in which case, sexual orientation reported in 1995 was used. This yielded a total of 926 lesbian women and 415 bisexual women out of a total of 99,658 women. Additional analyses were conducted examining results with an alternative assignment of sexual orientation. In these alternative analyses, sexual orientation reported in 1995 was used for waves 1991-2007 and sexual orientation reported in 2009 was used for the final 2011 wave. Results between the two different sexual orientation categorizations were largely the same.

Outcomes

Beginning in 1991, a 133-food item semi-quantitative (i.e., portion sizes are specified as part of the question) food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was used to obtain dietary information. A similar questionnaire was used every four years. Details on this FFQ, as well as the measures used in these analyses, have been described extensively in previous research, including a validation of the instrument.36 A broad array of dietary measures were included that have been known to be associated with excess weight gain or chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Alternative Healthy Eating Index-2010 (AHEI-2010)37 and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH),38 total energy intake (kcal/day),39 saturated fat (% energy),40 total fat (% of energy),39,40 cereal fiber (g/day),39,41,42 total fiber (g/day),39,41,43 glycemic load, and glycemic index.39,40,44 Participants who left 70 or more items unanswered on the overall FFQ, did not complete the sweets/baked goods/miscellaneous section, did not complete two or more other sections (includes dairy foods, fruits, vegetables, eggs/meat, breads/cereals, and beverages), or participants who reported implausible calorie intake (<600 and >3500 kcal) were excluded from analyses (9.4%). For each food item, a portion size was specified and participants were asked how often they had consumed that item quantity over the past year. Nutrient intake was calculated by multiplying frequency of intake by nutrient content of each food item and then summing nutrient contributions across all food items.37

The AHEI-2010 score emphasizes higher intake of vegetables, fruit, whole grains, nuts and legumes, long-chain (n-3) fats (EPA and DHA), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and lower intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice, red and processed meat, trans fat, sodium, and alcohol. All components were scored from 0 (unhealthy) to 10 (healthiest), and the total score ranged from 0 to 110.37

The DASH score was computed based on eight food components (fruit, vegetables, nuts/legumes/soy, red/processed meats, whole grains, low-fat dairy, sugar sweetened beverages, and sodium). A score ranging from 1 to 5 (5 representing the healthiest quintile of each food component) was assigned to each component, with total DASH scores ranging from 8 to 40.45

Covariates

Age in years at time of survey completion (grouped into categories of 26-30, 31-35, 36-40, 41-45, 46-50, 51-55, 56-60, 61-67), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs. other), rural vs. urban living status (based on zip code, less than 500 persons per square mile was defined as a rural area), region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and missing or outside the US), and annual household income reported in 2001 (<$50,000, $50,000-$75,000, $75,000-$100,000, >$100,000, and missing) were all included in models as covariates. Age, urban living status and region of residence were updated at each wave of data. Income was only assessed in 2001 and therefore, was not a time-varying covariate.

Data Analysis

Six waves of outcome data (1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007, and 2011) from NHSII were used in these analyses. Participants who reported being currently pregnant in each wave (from 1991-2007) were excluded from analyses for that year. Participants were not assessed pregnancy status in 2011, since the youngest participant was beyond typically defined child-bearing years (15-44 years).

To assess differences in sociodemographic characteristics by sexual orientation, bivariate Wald chi-square tests were performed for time invariant covariates (i.e., age at baseline, race/ethnicity, annual household income in 2001), while for time varying covariates (i.e., region of residence and rural living status), age-adjusted Wald chi-square tests were used. In examining the relationship between sexual orientation and dietary intake measures, several models were fit. First, age-standardized means were estimated of all dietary intake measures across all waves of data using a person-period dataset and tested for differences using age-adjusted Wald chi-square tests. Then, general patterns of key dietary intake measures were examined, specifically total calorie intake and overall diet quality. Unadjusted means were estimated for each age group across the three sexual orientation categories. Finally, to test for differences in the dietary measures by sexual orientation groups, repeated measures analyses using generalized estimating equations (to account for within-person correlation) were conducted to estimate the population average over the multiple waves of data. Linear regression models estimated β-coefficients for all outcomes. Both crude and adjusted (including age group, race, rural living status, region of residence, and income) models were fit and results were largely similar, therefore, only adjusted regression results are presented. In addition, two sets of interaction models were examined to assess for sexual orientation differences by age period and by rural living status. Further, in sexual orientation-by-age interaction models, age at baseline was controlled for to account for cohort effects, however, this did not change the results. Additionally, models including BMI as a covariate were examined, however, this did not substantially change results. Therefore, BMI was not included as a covariate. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (2010, SAS Institute, Inc.) with a significance level of 0.05. Participants provided informed consent for this study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Human Subjects Committee at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Results

There were significant differences across sexual orientation for all sociodemographic characteristics examined (Table 1). In this sample, when compared to heterosexual women, lesbian women were older at baseline, bisexual women were less likely to be white, and both lesbian and bisexual women reported lower incomes. Using all available waves of data, a greater proportion of heterosexual women lived in the Midwest than lesbian or bisexual women, and a greater proportion of heterosexual women lived in rural areas compared to lesbian women.

Table 1. Prevalence of demographic characteristics by sexual orientation among U.S. women in the Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2011).

| Heterosexual (n=98,317) | Lesbian (n=926) | p- valuea | Bisexual (n=415) | p- valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group in 1991b | <0.001 | 0.46 | |||

| 26-30 | 14.0% | 11.0% | 12. 5% | ||

| 31-35 | 30.2% | 26.8% | 27.7% | ||

| 35-40 | 34.4% | 36.8% | 36.9% | ||

| 41-46 | 21.5% | 25.4% | 22.9% | ||

|

| |||||

| Race/ethnicityb | 0.28 | 0.003 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 92.7% | 93.6% | 88. 9% | ||

| Other | 7.3% | 6.3% | 11.1% | ||

|

| |||||

| Income in 2001b | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| <$50,000 | 11.3% | 17.2% | 21.9% | ||

| $50,000-$75,000 | 19.1% | 25.4% | 25.5% | ||

| $75,000-$100,000 | 14.7% | 13.8% | 14.7% | ||

| >$100,000 | 24.1% | 21.7% | 18.3% | ||

| Missing | 30.9% | 21.9% | 19.5% | ||

|

| |||||

| Region of residencec | |||||

| Northeast | 32.9% | 31.7% | 0.48 | 34.4% | 0.32 |

| Midwest | 32.7% | 23.5% | <0.001 | 21.0% | <0.001 |

| South | 19.0% | 19.3% | 0.88 | 16.2% | 0.16 |

| West | 15.2% | 25.4% | <0.001 | 28.1% | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Ruralc | 31.7% | 21.8% | <0.001 | 28.0% | 0.08 |

calculated from Wald chi-square test; compared to heterosexual women

time invariant demographic characteristic

time varying demographic characteristic; age-standardized prevalence was calculated over all available waves of data

Age-standardized means of dietary intake measures across all available waves are presented in Table 2. Across all waves of data, adjusting for age only, there were significant differences in dietary intake across sexual orientation for nearly every measure except glycemic load and polyunsaturated fat consumption. Generally, lesbian and bisexual women reported more healthful levels of dietary intake than heterosexual women.

Table 2. Age-standardized measures of dietary intake across all available waves by sexual orientation, Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2011).

| mean(SD)a,b

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual (n=98,317) | Lesbian (n=926) | p-valuec | Bisexual (n=415) | p-valuec | |

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index-2010 Score | 54.43(13.18) | 57.14(13.30) | <0.001 | 58.47(13.70) | <0.001 |

| Vegetables (servings/day) | 3.29(2.06) | 3.24(2.13) | 0.26 | 3.56(2.33) | 0.002 |

| Fruits (servings/day) | 1.43(1.13) | 1.42(1.12) | 0.34 | 1.60(1.29) | <0.001 |

| Whole grains (g/day) | 28.95(19.54) | 30.81(20.32) | <0.001 | 31.47(19.59) | <0.001 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice (servings/day) | 0.93(1.10) | 0.85(1.04) | 0.01 | 0.93(1.13) | 0.99 |

| Nuts and legumes (servings/day) | 0.48(0.63) | 0.58(0.77) | <0.001 | 0.70(0.81) | <0.001 |

| Red/processed meat (servings/day) | 0.88(0.63) | 0.71(0.63) | <0.001 | 0.72(0.63) | <0.001 |

| trans fat (% energy) | 0.01(0.01) | 0.01(0.01) | d | 0.01(0.01) | d |

| Long-chain (n-3) fats (EPA + DHA) (mg/day) | 242.89(265.24) | 242.26(253.73) | 0.63 | 290.71(311.87) | <0.001 |

| PUFAa (% energy) | 5.95(1.88) | 5.90(1.89) | 0.21 | 5.99(1.97) | 0.93 |

| Sodium (mg/day) | 2112.91(756.01) | 2020.57(749.14) | <0.001 | 2169.26(803.98) | 0.02 |

| Alcohol (drinks/day) | 0.35(0.63) | 0.51(0.84) | <0.001 | 0.47(0.80) | <0.001 |

| DASHa Score | 23.54(4.75) | 24.23(4.92) | <0.001 | 24.82(4.92) | <0.001 |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 1809.23(572.72) | 1756.18(571.18) | <0.001 | 1916.91(618.11) | <0.001 |

| Saturated fat (% energy) | 10.56(2.73) | 10.38(2.94) | 0.005 | 10.38(2.90) | 0.11 |

| Total fat (% energy) | 31.71(6.73) | 31.26(7.16) | <0.001 | 31.39(7.05) | 0.10 |

| Cereal fiber (g/day) | 6.40(3.76) | 6.28(3.98) | 0.27 | 6.92(4.19) | <0.001 |

| Total fiber (g/day) | 20.33(8.83) | 20.55(9.45) | 0.59 | 22.81(10.51) | <0.001 |

| Glycemic Load | 118.50(24.60) | 118.15(26.34) | 0.98 | 118.24(25.89) | 0.96 |

| Glycemic Index | 52.43(4.22) | 51.91(4.43) | <0.001 | 51.70(4.37) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations - SD: Standard Deviation; PUFA: Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid; DASH: Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

Values are means(SD) and are standardized to the age distribution of the study population

p-values were generated from Wald chi-square test of age-adjusted repeated measures models; compared to heterosexual women

model not estimated due to poor convergence

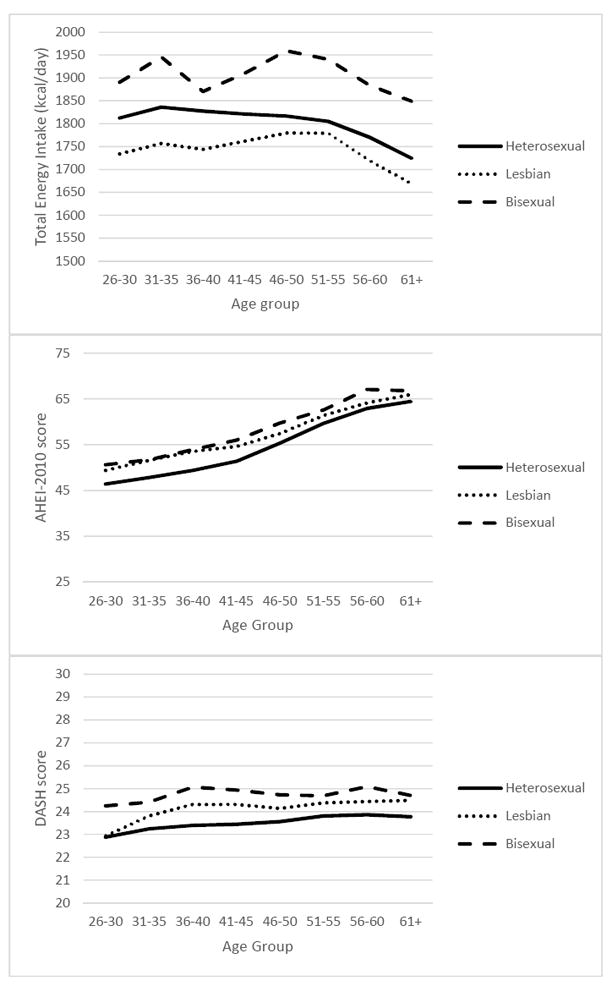

Figure 1 shows descriptive unadjusted mean levels of diet quality (AHEI-2010 and DASH scores) and total energy intake over adulthood by sexual orientation. Measures of overall diet quality (i.e., AHEI-2010 and DASH) suggest that bisexual women have the highest diet quality score, followed by lesbian women. In addition, diet quality scores appeared to be increasing with age across all sexual orientation groups for AHEI-2010, while DASH scores appeared relatively stable. Regardless of age, lesbian women reported lower energy intake than bisexual or heterosexual women.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted means of total energy intake, Alternative Healthy Eating Index-2010, and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension scores by sexual orientation among 99,658 women participating in the Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2011)

Results from repeated measures analyses are presented in Table 3. After adjusting for covariates, both lesbian and bisexual women had higher diet quality scores than heterosexual women [β (95% CI): AHEI-2010, lesbian: 2.41 (1.76, 3.06); AHEI-2010, bisexual: 3.38 (2.39, 4.38); DASH, lesbian: 0.59 (0.33, 0.85); DASH, bisexual: 1.16 (0.77, 1.56)]. Lesbian women reported consuming, on average over the repeated measures, fewer calories daily, while bisexual women reported consuming more calories than heterosexual women. Lesbian women reported consuming less fat [β (95% CI): saturated fat: -0.16 (-0.30, -0.03); total fat: -0.49 (-0.79, -0.18)] and reported diets with lower glycemic index [β (95% CI): -0.46 (-0.65, -0.28)] than heterosexual women. On average, there were no appreciable differences between lesbian and heterosexual women in reported fiber consumption. Bisexual women, on average, reported consuming more fiber [β (95% CI): cereal fiber: 0.54 (0.26, 0.82); total fiber: 2.33 (1.52, 3.13)] and reported diets lower in glycemic index [β (95% CI): -0.66 (-0.93, -0.39)] than heterosexual women. On average, there were no notable differences in reported glycemic load across sexual orientation.

Table 3. Multivariable adjusteda regression models estimating association between sexual orientation and dietary intake, Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2011).

| β (95% CI)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Heterosexual (ref)c | Lesbiand | Bisexuald | |

| AHEIb (score range: 0-110) | 45.56 (45.25,45.88) | +2.41 (1.76,3.06)*** | +3.38 (2.39,4.38)*** |

| DASHb (score range: 8-40) | 23.07 (22.94,23.20) | +0.59 (0.33,0.85)*** | +1.16 (0.77,1.56)*** |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 1782.83 1766.45,1799.20) | -60.64 (-90.96,-30.32)*** | +107.83 (58.68,156.98)*** |

| Saturated fat (% energy) | 11.03 (10.96,11.10) | -0.16 (-0.30,-0.03)* | -0.12 (0.33,0.08) |

| Total fat (% energy) | 30.76(30.59,30.92) | -0.49 (-0.79,-0.18)** | -0.36 (0.82,0.10) |

| Cereal fiber (g/day) | 4.61 (4.51,4.70) | -0.12 (-0.30,0.06) | +0.54 (0.26,0.82)*** |

| Total fiber (g/day) | 16.57 (16.32,16.82) | +0.04 (-0.44,0.52) | +2.33 (1.52,3.13)*** |

| Glycemic load | 129.55 (128.90,130.19) | -0.05 (-1.23,1.13) | -0.43 (-2.09,1.22) |

| Glycemic index | 55.13 (55.03,55.23) | -0.46 (-0.65,-0.28)*** | -0.66 (-0.93,-0.39)*** |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, rural living status, region of residence, and annual household income

Abbreviations – β: regression parameter estimate; CI: Confidence Interval; AHEI: Alternative Healthy Eating Index; DASH: Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

point estimate for heterosexual women, based on adjusted intercept of linear repeated measures analyses

difference in β estimate from the heterosexual reference group

For nearly all dietary measures, there were important changes in dietary quality and intake from ages 26-67 years. For example, both cereal and total fiber intake statistically significantly increased with age while glycemic load and glycemic index decreased (data not shown). Interestingly, AHEI-2010 scores indicate improvement in diet quality with age while DASH scores indicate more stable diet quality (unadjusted measures in Figure 1). Generally, there were no significant age-by-sexual-orientation interactions, except among lesbian women for AHEI-2010, suggesting that differences in dietary intake remained largely consistent across sexual orientation during ages 26-67 years (data not shown). For AHEI, lesbian women between the ages of 26-50 had higher AHEI scores than same-aged heterosexual women. However, by age 51, although lesbian women still had higher AHEI scores than heterosexual women, the difference was smaller than during younger ages (unadjusted measures in Figure 1).

On average, those living in rural areas had statistically significant overall diet quality scores based on AHEI-2010 and DASH that were slightly lower than those living in urban areas (data not shown). Additionally, rurality-by-sexual orientation interactions were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Findings from this study suggest that during ages 26-67 years, lesbian and bisexual women, on average, reported consumption of foods with higher diet quality. Additionally, lesbian and bisexual women reported similar or slightly healthier levels of dietary intake on other indicators compared with heterosexual women. Finding also suggest that lesbian women had lower calorie intake, while bisexual women had higher calorie intake, when compared with heterosexual women. However, it is possible that differences in physical activity levels could account for this small difference. Similarly, although there were statistically significant sexual orientation differences in fat intake, actual differences were small and suggest comparable intake across sexual orientation groups. It is possible that the observed sexual orientation differences in dietary intake could be explained by reporting bias, measurement error, or limited precision associated with the use of FFQ.36 Regardless, taken together these findings do not support the study’s hypothesis that lesbian and bisexual women would have less healthy diets than heterosexual women.

Previous population-based studies on disparities in dietary intake by sexual orientation groups have cross-sectionally focused on fruit and vegetable consumption with some suggesting less consumption among lesbian or bisexual women4,46 and others finding no difference in fruit and vegetable consumption when compared with heterosexual women.6,13,15,18 In contrast to these population-based studies, bisexual women in our study were on average, reporting consuming more fruits and vegetables than heterosexual women, although there were no differences between lesbian and heterosexual women. While fruit and vegetable consumption is an important aspect of dietary intake, it represents only a small part overall. This study provides a much more comprehensive understanding of sexual orientation differences in dietary quality and intake during adulthood. Only one other study has examined different aspects of dietary intake beyond fruit and vegetable consumption, including regular and diet soda consumption, as well as general eating habits (such as eating fast food and eating breakfast) that are important to health.15 Findings further complement existing research by the addition of a longitudinal study design as well as the use of a FFQ rather than a brief screener to assess multiple measures of diet. Longitudinal data from our study indicate that diet quality increases as women age, irrespective of sexual orientation. Therefore, it is important to improve diet quality during younger ages, as well as to develop interventions for different life stages when disparities are present.

Corroborating existing research,3,6,12-20 a previous study using NHSII data found that lesbian and bisexual women were more likely than heterosexual women to experience obesity and weight gain during adulthood.26 The findings in the current study that dietary quality and intake may be better among lesbian and bisexual women suggests that other weight-related factors, such as low levels of physical activity, and high levels of sedentary behaviors, disordered eating behaviors, and psychosocial and minority stress, could be contributing to weight gain among lesbian and bisexual women more so than dietary intake. It is also possible that greater calorie intake among bisexual women, in conjunction with other obesogenic behaviors among lesbian and bisexual women compared to heterosexual women could be contributing to sexual orientation disparities in obesity and weight gain, but additional research is needed to test this hypothesis. Moreover, other factors, such as social norms regarding health, diet, and body image, may contribute to differences in health behaviors and outcomes across sexual orientation subgroups.47,48 These factors may partially explain why our sample of lesbian and bisexual women have higher diet quality scores than their heterosexual counterparts. However, existing research on these areas of weight-related health remains underexplored and future research should identify how these other factors relate to weight gain and health conditions associated with overweight and obesity.

Measures of overall diet quality suggest that lesbian and bisexual women may have healthier diets than heterosexual women. These measures of diet quality, AHEI-2010 and DASH, have been associated with numerous chronic conditions in prior studies.37,38 Even after adjusting for BMI, higher AHEI-2010 scores (i.e., increasing score quintiles) among women in the first Nurses’ Health Study cohort were still inversely associated with numerous chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease ((RR (95% CI)) quintile 2: 0.91 (0.84, 0.99); quintile 3: 0.82 (0.74, 0.89); quintile 4: 0.79 (0.72, 0.86); quintile 5: 0.74 (0.67, 0.81)) and diabetes (quintile 2: 0.88 (0.81, 0.94); quintile 3: 0.82 (0.75, 0.87); quintile 4: 0.74 (0.68, 0.80); quintile 5: 0.65 (0.59, 0.71)).37 This is a promising finding, suggesting that although overweight and obesity adversely impact lesbian and bisexual women, higher diet quality scores among lesbian and bisexual women, such as the findings in this study, may provide some protective effect against development of chronic conditions; although, the risk of developing chronic conditions with slightly higher diet quality scores across adulthood should be explored to determine the clinical significance of these differences. Future research is needed to corroborate the findings from this study and should examine sexual orientation disparities in health outcomes such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer and the mediating effect of dietary intake on these outcomes for lesbian and bisexual women.

While rural versus urban living situation has been highlighted as an area for potential disparities for lesbian, gay, and bisexual people,24 our findings suggest that with regard to diet, living in rural areas does not seem to differentially impact lesbian and bisexual women compared to heterosexual women. Although, those living in rural areas reported significantly less healthy levels of dietary intake than those living in urban settings, the magnitude of the differences were small and similar for all sexual orientation groups. Nonetheless, previous research has shown that overweight and obesity are more prevalent in rural settings,27,29,33,49,50 therefore, rurality continues to be an important factor to consider in weight-related research and should be incorporated into future work on sexual orientation disparities in weight-related health.

This study was novel because it was able to longitudinally examine a comprehensive assessment of dietary intake over the ages 26-67 years by sexual orientation. Further, findings add to the scant literature on sexual orientation disparities in nutrition by expanding understanding beyond fruit and vegetable consumption and by using a validated FFQ rather than a brief screener on specific food items. Despite this, there are several caveats to consider. Although the FFQ has been validated, measurement of, for example, calorie intake, is less precise than other tools such as a food diary; this is particularly notable for women who are obese, as they may underreport their calorie intake.51 However, given the large sample size, an FFQ is the most reasonable approach for data collection.

In addition, compared to the general population, the study sample of nurses comprised a narrower distribution of socioeconomic positions and racial/ethnic diversity. Therefore, findings from this study may not be generalizable to women in low or high socioeconomic positions, women who are not in the nursing profession, or non-white women. This sample difference may also explain why findings differ slightly from population-based studies, however, as no other study has examined dietary intake using a FFQ, more research is needed to examine this issue. Related, sample differences may also partially explain the lower prevalence of lesbian and bisexual women in this study (1.3%) compared to estimates from national population-based studies, which have varying estimates of 2.4% in the 2013 National Health Interview Survey20and 4.1%-4.6% in the 2012-2013 National Survey of Family Growth.12,52 However, it should be noted that due to differences in sampling procedures, study methods, and age and cohort ranges of participants (NHSII participants are older in age and from an older cohort), the estimates between this study and population-based studies should not be directly compared. Moreover, there are limitations in measurement with this sample; notably, household income was only measured once and therefore, this demographic characteristic was not included as a time-varying covariate. This may result in residual confounding. Additional research using longitudinal population-based samples are needed to examine these issues. Further, dietary intake and sexual orientation data were based on self-reports with pre-determined categorical responses, therefore there is likely to be some measurement error and misclassification.

Conclusion

Finding from this study suggest that lesbian and bisexual women may have more healthful diets during adulthood than heterosexual women. However, more research is needed to corroborate these findings. Results also indicate that, irrespective of sexual orientation, diet quality was lower during younger ages and gradually improved as women aged. This finding suggest the need for interventions in young adulthood aimed at improving diet quality. Further, among adults over age 50 years, the difference between lesbian and heterosexual women’s diet quality scores was smaller compared to younger ages when the difference in diet quality score was greater, which suggests there may also be benefits to intervening among older adults. Our study did not find substantial differences in dietary intake based on rural versus urban living, however, more research is needed to corroborate these findings. Given existing research documenting lesbian and bisexual women’s disparities in overweight and obesity, further work is needed to understand the complex relationships between dietary intake, physical activity, sedentary behaviors, disordered eating behaviors, and stress in weight management among lesbian and bisexual women.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by Award Number DK099360, DK58845, and UM1CA176726 from NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nicole A. VanKim, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts, 405 Arnold House, 715 North Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003-9304, Phone: 413-545-4019, Fax: 413-545-1645.

S. Bryn Austin, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 333 Longwood Ave, Room #634, Boston, MA 02115, Phone: 617-355-8194.

Hee-Jin Jun, Institute for Behavioral and Community Health, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, 9245 Sky Park Ct., Suite 100, San Diego, CA 92123, Phone: 619-594-0170, Fax: 619-594-1462.

Frank B. Hu, Department of Nutrition, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 655 Huntington Avenue, Building II 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02115, Phone: 617-432-0113.

Heather L. Corliss, Institute for Behavioral and Community Health, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, 9245 Sky Park Ct., Suite 100, San Diego, CA 92123, Phone: 619-594-3470, Fax: 619-594-1462.

References

- 1.Farmer GW, Jabson JM, Bucholz KK, Bowen DJ. A population-based study of cardiovascular disease risk in sexual minority women. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1845–1850. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Przedworski JM, McAlpine D, Karaca-Mandic P, VanKim NA. Health and health risks among sexual minority women: an examination of three subgroups. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1045–1047. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP. Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehmer U, Miao X, Linkletter C, Clark MA. Adult health behaviors over the life course by sexual orientation. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:292–300. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1953–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dilley JA, Simmons KW, Boysun MJ, Pizacani BA, Stark MJ. Demonstrating the importance of feasibility of including sexual orientation in public health surveys: Health disparities in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corliss HL, Wadler BM, Jun H-J, et al. Sexual-orientation disparities in cigarette smoking in a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):213–22. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin SB. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents: Findings from the Growing Up Today Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(11):1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, Balsam KF, Mincer SL. Disparities in health-related quality of life: A comparison of lesbians and bisexual women. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2255–2261. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochran SD, Mays VM, Sullivan JG. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(1):53–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehmer U, Bowen DJ, Bauer GR. Overweight and obesity in sexual-minority women: evidence from population-based data. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1134–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boehmer U, Bowen DJ. Examining factors linked to overweight and obesity in women of different sexual orientations. Prev Med (Baltim) 2009;48(4):357–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deputy NP, Boehmer U. Weight status and sexual orientation: differences by age and within racial and ethnic subgroups. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):103–109. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laska MN, VanKim NA, Erickson DJ, Lust K, Eisenberg ME, Rosser BRS. Disparities in weight and weight behaviors by sexual orientation in college students. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):111–121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ, et al. Sexual orientation, health risk factors, and physical functioning in the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Women’s Heal. 2004;13(9):1033–1047. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H, Barkan S. Disability among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Disparities in prevalence and risk. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:16–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garland-Forshee RY, Fiala SC, Ngo DL, Moseley K. Sexual orientation and sex differences in adult chronic conditions, health risk factors, and protective health practices: Oregon 2005-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E136. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Hispanic lesbians and bisexual women at heightened risk for health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e9–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward BW, Dahlhamer JM, Galinsky AM, Joestl SS. National health statistics reports; no 77. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. Sexual orientation and health among US adults: National Health Interview Survey 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowen DJ, Balsam KF, Ender SR. A review of obesity issues in sexual minority women. Obesity. 2008;16(2):221–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliason MJ, Ingraham N, Fogel SC, et al. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Weight in Sexual Minority Women. Women’s Heal Issues. 2015;25(2):162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obes Res. Suppl 2. Vol. 6. National Institutes of Health; 1998. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report; pp. 51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanKim NA, Erickson DJ, Eisenberg ME, Lust K, Rosser BRS, Laska MN. College women’s weight-related behavior profiles differ by sexual identity. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(4):461–470. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.4.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jun H, Corliss HL, Nichols LP, Pazaris MJ, Spiegelman D, Austin SB. Adult body mass index trajectories and sexual orientation: the Nurses’ Health Study II. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(4):348–54. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson JE, Doescher MP, Jerant AF, Hart LG. A national study of obesity prevalence and trends by type of rural county. J Rural Heal. 2005;21(2):140–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patterson PD, Moore CG, Probst JC, Shinogle JA. Obesity and physical inactivity in rural America. J Rural Heal. 2004;20(2):151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Befort CA, Nazir N, Perri MG. Prevalence of obesity among adults from rural and urban areas of the United States: findings from NHANES (2005-2008) J Rural Heal. 2012;28(4):392–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comerford SA, Henson-Stroud MM, Sionainn C, Wheeler E. Crone Songs: Voices of Lesbian Elders on Aging in a Rural Environment. Affilia. 2004;19(4):418–436. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin EL, Irwin Ja. Health Behaviors and Health Care Utilization of Southern Lesbians. Women’s Heal Issues. 2010;20(3):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King S, Dabelko-Schoeny H. “Quite Frankly, I Have Doubts About Remaining”: Aging-In-Place and Health Care Access for Rural Midlife and Older Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals. J LGBT Health Res. 2009;5(1-2):10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barefoot KN, Warren JC, Smaller KB. An examination of past and current influences of rurality on lesbians’ overweight/obesity risks. LGBT Heal. 2015;2(2):154–161. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. The Nurses’ Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(5):388–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ, et al. Disclosure of sexual orientation and behavior in the Nurses’ Health Study II: results from a pilot study. J Homosex. 2006;51(1):13–31. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willett WC, Sampson L, Browne ML, et al. The use of a self-administered questionnaire to assess diet four years in the past. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(1):188–199. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, et al. Alternative Dietary Indices Both Strongly Predict Risk of Chronic Disease. J Nutr. 2012;142:1009–1018. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.157222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liese AD, Nichols M, Sun X, D’Agostino RB, Haffner SM. Adherence to the DASH Diet is inversely associated with incidence of type 2 diabetes: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(8):1434–6. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shai I, Jiang R, Manson JE, et al. Ethnicity, obesity, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1585–90. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu FB, van Dam RM, Liu S. Diet and risk of Type II diabetes: the role of types of fat and carbohydrate. Diabetologia. 2001;44(7):805–17. doi: 10.1007/s001250100547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer KA, Kushi LH, Jacobs DR, Jr, Slavin J, Sellers TA, Folsom AR. Carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and incident type 2 diabetes in older women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:921–930. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulze MB, Liu S, Rimm EB, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and dietary fiber intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in younger and middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;(10):348–356. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Threapleton DE, Greenwood DC, Evans CEL, et al. Dietary fibre intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6879. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):790–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tobias DK, Hu FB, Chavarro J, Rosner B, Mozaffarian D, Zhang C. Healthful dietary patterns and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(20):1566–72. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosario M, Corliss HL, Everett BG, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related risk behaviors of tobacco, alcohol, sexual behaviors, and diet and phyiscal activity: pooled Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):245–254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowen DJ, Balsam KF, Diergaarde B, Russo M, Escamilla GM. Healthy eating, exercise, and weight: Impressions of sexual minority women. Women Health. 2008;44(1):79–93. doi: 10.1300/J013v44n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.VanKim NA, Porta CM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer DR, Laska MN. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual college student perspectives on weight-related behaviors: A qualitative analysis. J Clin Nurs. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13106. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sobal J, Troiano RP, Frongillo EA. Rural-urban differences in obesity. Rural Sociol. 1996;61(2):289–305. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramsey PW, Glenn LL. Obesity and health status in rural, urban, and suburban southern women. South Med J. 2002;95(7):666–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lavienja AL, Braam LM, Ocké MC, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Seidell JC. Determinants of obesity-related underreporting of energy intake. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(11):1081–1086. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chandra A, Mosher WD, Copen C, Sionean C. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: Data From the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, MD: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]