Abstract

Early childhood experiences have lasting effects on development, including the risk for psychiatric disorders. Research examining the biologic underpinnings of these associations has revealed the impact of childhood maltreatment on the physiologic stress response and activity of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis. A growing body of literature supports the hypothesis that environmental exposures mediate their biological effects via epigenetic mechanisms. Methylation, which is thought to be the most stable form of epigenetic change, is a likely mechanism by which early life exposures has lasting effects. In this review, we present recent evidence related to epigenetic regulation of genes involved in HPA axis regulation, namely the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP5), after childhood adversity and associations with risk for psychiatric disorders. Implications for the development of interventions and future research are discussed.

Introduction

Childhood adversity lays a fragile foundation for health across the lifespan. Adverse childhood experiences including child maltreatment, trauma, and exposure to other contextual stressors associated with poverty are major risk factors for the development of psychiatric disorders as well as other medical conditions in children and adults (Benjet, Borges & Medina-Mora, 2010; Cohen, Janicki-Deverts & Miller, 2007; Felitti et al., 1998; Green et al., 2010; Slopen, Koenen & Kubzansky, 2014). Indeed, one study found that adults with numerous adverse childhood experiences died nearly 20 years earlier than others (Brown et al., 2009). The mechanisms underlying the links between childhood adversity and poor health outcomes are not fully understood. It is clear that childhood adversity can alter the physiologic stress response and it has been posited that changes to the stress response system may underlie the connection between early adversity and psychiatric and other health consequences (McEwen, 2013; Ridout, Carpenter & Tyrka, 2016; Ridout et al., 2015). There is growing appreciation that epigenetic modifications to genes that regulate the stress response are a likely mechanism by which the early environment has long-lasting impact on stress biology. In this selective review, we describe the role of glucocorticoid signaling and epigenetic modifications in the biological response to environmental exposures and review emerging findings from our laboratory and others that suggest this mechanism underlying risk for psychiatric and other health problems.

Alterations of HPA Axis Function and Glucocorticoid Signaling with Childhood Adversity

Research examining the biologic underpinnings of the associations between childhood maltreatment and psychopathology highlights the importance of the physiologic stress response system, and in particular, the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis. In response to stressful stimuli, glucocorticoids are released and exert cellular responses by binding at the intracellular glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Glucocorticoid receptors are distributed throughout the body and brain where they regulate basal physiologic function and effect changes in various organ systems and tissues that promote adaptive responding to acute stressors (de Kloet, Joels & Holsboer, 2005; Kadmiel & Cidlowski, 2013). Activation of the GR through cortisol binding at the hypothalamus and pituitary engages a negative feedback loop that inhibits further release of cortisol and prevents damaging effects of extreme or chronic activation (Herman et al., 2012; Laryea et al., 2015).

Excessive stimulation by severe or prolonged stress may result in adaptive changes that alter function of the HPA axis (Doom, Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2014; Fries et al., 2005; Heim, Ehlert & Hellhammer, 2000; McEwen, 2007; Pryce et al., 2005; Tyrka et al., 2008). Frequent or excessive activation of the HPA axis in response to stress exposure can progress to a counter-regulatory state of chronic adrenal stress hyporeactivity (Fries et al., 2005; Heim et al., 2000; McEwen, 2007; Pryce et al., 2005). The timing of adversity exposure during development may impact HPA axis programming (Bosch et al., 2012), and chronic stress exposure may have the most profound effects, as repeated attempts at maintaining homeostasis alters set points and response characteristics of stress-responsive physiologic systems (Lee & Sawa, 2014; McEwen, Nasca & Gray, 2016).

Several studies from our group and others have revealed that early adversity is linked to abnormalities in HPA axis function in both children and adults (Gonzalez, 2013; Gunnar & Vazquez, 2001; McCrory, De Brito & Viding, 2010). Early work in our laboratory with a sample of 50 healthy adults demonstrated that those with a history of moderate-to-severe childhood maltreatment (n = 23) exhibited blunted cortisol reactivity to a standardized psychosocial stress paradigm (the Trier Social Stress Test, TSST) compared to adults with no maltreatment history (Carpenter et al., 2007). That these adults did not have any active psychiatric conditions, including Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), suggests that early adversity poses a significant independent risk factor for altered HPA functioning even among individuals who are otherwise healthy. Several studies have replicated these findings (Carpenter et al., 2011; Carpenter et al., 2009; Elzinga et al., 2008; Klaassens et al., 2010; Klaassens et al., 2009; Tyrka et al., 2008). In another study of 230 adults, our group demonstrated that a history of childhood emotional abuse was also associated with a blunted cortisol response to a pharmacological challenge (Carpenter et al., 2009). Similar to earlier work in our laboratory, none of the adult participants currently met criteria for mood or anxiety disorders including MDD and PTSD, and these links were observed even when controlling for sub-threshold symptoms of psychopathology and past psychiatric conditions. Furthermore, the association of emotional maltreatment and cortisol reactivity was stronger among older adults in the sample suggesting that the effects of early adversity contribute to “wear and tear” on this system across the lifespan. Exaggerated cortisol responses have also sometimes been seen in association with early stress. In a study of 88 healthy adults, we demonstrated that the nature of childhood experiences moderated the cortisol response to pharmacologic challenge (Tyrka et al., 2008). Childhood parental death or desertion (N=44) was linked with an exaggerated cortisol response to the dexamethasone corticotropin-releasing hormone (Dex/CRH) test, a pharmacological challenge designed to assess HPA function. This response was moderated by the type of loss and the level of parental care. Those who experienced parental desertion coupled with low parental care demonstrated a blunted cortisol response, supporting the hypothesis that severe or chronic forms of stress may be more likely to lead to cortisol hyporeactivity. Taken together, this work from our laboratory underscores the persistent effects of childhood maltreatment on neuroendocrine function into adulthood, and highlights the importance of adversity characteristics as determinants of the pattern of HPA axis dysfunction.

The long-lasting effects of early adversity on HPA axis function have also been observed in numerous studies of children (Gonzalez, 2013; van Andel et al., 2014; Doom & Gunnar, 2013). Similar to work with adults, several studies have shown blunted diurnal cortisol concentrations with adversity, but others have shown no difference or elevated cortisol levels. A number of studies have examined the determinants of diurnal cortisol patterns in children who experience significant adversity such as maltreatment. A study of 187 maltreated and 154 nonmaltreated 5–13 year-old children found that overall cortisol levels across 20 weeks did not differ between maltreated and nonmaltreated children, but the maltreated group showed elevated within-person variation in cortisol values, and those with higher initial cortisol levels had cortisol suppression over time (Doom et al., 2014). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that glucocorticoid downregulation may occur over time in response to elevations in cortisol levels. In addition, maltreatment severity, timing, and the number of maltreatment subtypes predicted cortisol variability. Both maltreatment and greater cortisol variability were associated with more behavior problems (Doom et al., 2014). Attenuation of HPA function has been reported in children referred for child protective services; importantly, blunted cortisol was linked to more externalizing behaviors and mediated the relationship between child protective service involvement and externalizing symptoms (Bernard, Zwerling & Dozier, 2015), and an attachment based intervention normalized wake-up and diurnal cortisol levels in this study (Bernard, 2015). The role of HPA axis dysfunction in the pathogenesis of psychopathology and the response to interventions is discussed further below.

Role of the HPA axis and Glucocorticoid Signaling in Risk for Psychopathology

Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that excessive exposure to stress-induced glucocorticoid activity may be involved in the pathogenesis of stress-related psychiatric disorders, including depressive and anxiety disorders. In rodent models, prolonged stress or glucocorticoid exposure produces anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors (Maccari et al., 2014; Skupio et al., 2015; van Donkelaar et al., 2014). In children and adolescents, altered cortisol responses are associated with internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, suicidal ideation, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and depression (Braquehais et al., 2012; Doom & Gunnar, 2013; Faravelli et al., 2012; Guerry & Hastings, 2011; Ruttle et al., 2011). In a racially-mixed community sample of 102 boys aged 8–11, we found that afternoon basal cortisol concentrations were positively associated with internalizing behavior problems, social problems, and emotionality. In addition, greater declines across a home-visit challenge task were significantly associated with internalizing behavior, as well as social, attention, and thought problems (Tyrka et al., 2010). In a two-year follow-up assessment of 78 of the boys, greater cortisol declines across the home visit task were predictive of internalizing and externalizing behaviors, as well as attention and social problems. Moreover, morning and afternoon cortisol concentrations at the initial assessment significantly predicted the later development of child depressive symptoms (Tyrka et al., 2012a).

As discussed above, adversity and trauma can be associated with both exaggerated and attenuated profiles of neuroendocrine function (Doom & Gunnar, 2013; Miller, Chen & Zhou, 2007; Morris, Compas & Garber, 2012). A meta-analysis of 6,000 trauma-exposed participants with and without PTSD (Morris et al., 2012) showed that relative to non-exposed participants, those with PTSD as well as those with both PTSD and MDD had lower morning cortisol, lower daily output of cortisol, and lower cortisol response to dexamethasone. Trauma-exposed participants (including those with childhood neglect and abuse) without PTSD or MDD also showed blunted post-dexamethasone cortisol and afternoon/evening cortisol (Morris et al., 2012). The only group to show elevated cortisol had comorbid PTSD/MDD, and only evening cortisol was elevated. Interestingly, this was also the only group to also show an effect of developmental timing: after controlling for the time elapsed since the focal trauma, exposure during adulthood was associated with large negative effects on morning cortisol and post-dexamethasone cortisol, whereas exposure in childhood had negligible effects in this group. However, it is important to note that overall, in both PTSD groups, time elapsed since exposure to the focal trauma was significantly associated with lower daily and post-dexamethasone cortisol levels, and with lower afternoon/evening cortisol at trend level. Other work has identified additional characteristics that influence patterns of adrenocortical dysregulation, including the nature of the trauma and other contextual factors, timing of the exposure, comorbid psychiatric and other conditions, and genetic background (De Bellis & Zisk, 2014; Doom & Gunnar, 2013; Struber, Struber & Roth, 2014).

Given the critical negative feedback role of the GR, alterations of the number and sensitivity of the GR may explain abnormalities of HPA function associated with adversity and psychopathology. Depressed patients who have non-suppression to the dexamethasone-suppression test have impaired leukocyte GR responses to GR agonists (Gormley et al., 1985; Lowy et al., 1988). Patients with PTSD, who often have blunted cortisol responses to stress, show “super-suppression” to dexamethasone and associated negative feedback sensitivity of lymphocyte GRs (Rohleder et al., 2004; Yehuda, 2001; Yehuda et al., 2010b; Yehuda et al., 2002; Yehuda et al., 2004; Yehuda et al., 2003). High premorbid GR expression is a risk factor for PTSD (van Zuiden et al., 2011). Taken together, these findings indicate that abnormalities in leukocyte GR number and function may be risk factors for the development of stress-related psychiatric disorders, and may reflect effects due to early-life stress exposure (Anacker et al., 2011).

The GR is distributed throughout limbic brain regions and numerous other organ systems, so that excessive glucocorticoid activation at these receptors, or changes to the sensitivity of this system may underlie psychiatric and other stress-related conditions. Findings from animal models and human neuroimaging studies indicate that the hippocampus and amygdala are highly vulnerable to the effects of early-life stress and trauma (Lupien et al., 2009; Rifkin-Graboi et al., 2015; Tottenham & Sheridan, 2009). The hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex have a high density of GRs, and animal models show that exposure to stress or glucocorticoids, along with effects on other stress mediators, alters neural structure in these regions (McEwen et al., 2016). Chronic stress and glucocorticoids impair neuronal growth and survival in these brain regions; this may explain neuroimaging findings of reduced brain region volumes in association with early stress (McEwen et al., 2015). In the hippocampus, chronic stress and glucocorticoid treatment inhibit neurogenesis, cell proliferation and dendritic branching, and induce cell loss and atrophy (Duman, 2009; McEwen et al., 2016; van der Kooij et al., 2015). In contrast, in the amygdala, which mediates fear responses, chronic stress may induce a proliferative effect on neuronal dendritic branching and spine density (Vyas, Jadhav & Chattarji, 2006). These changes in dendritic length are accompanied by elevations in glucocorticoids (Lakshminarasimhan & Chattarji, 2012) and administration of glucocorticoids can elicit similar dendritic lengthening while increasing anxiety behaviors (Mitra & Sapolsky, 2008). Interestingly, administration of low to moderate doses of glucocorticoids at the time of acute or chronic stress exposure prevents dendritic changes in the amygdala and the development of anxiety (Rao et al., 2012; Zohar et al., 2011), suggesting that glucocorticoids may impart protection under conditions of moderate stress but risk with more extreme exposures. Recent evidence shows that glucocorticoid signaling in the prefrontal cortex modifies fear conditioning and responses in animal models (Reis et al., 2015; Wislowska-Stanek et al., 2013). Similar to the hippocampus, chronic stress also causes structural remodeling of the prefrontal cortex that is reversible after the termination of stress; this is not as readily reversible in aged animals (Bloss et al., 2010). Thus, animal models show that stress and glucocorticoid exposure have the potential to cause structural changes to the brain circuitry critical to affective and behavioral adaptation, and thus likely underlie associations between early adversity and risk for psychopathology.

Epigenetic Mechanisms of Risk

Epigenetic changes to DNA are a mechanism by which the environment can impact gene activity and expression (Hernando-Herraez et al., 2015). Methylation, thought to be the most stable form of epigenetic change, is a likely mechanism by which stress exposure has long-lived effects. In mammals, methylation mainly occurs at CpG dinucleotides, which are sites in the DNA where a cytosine nucleotide occurs next to a guanine nucleotide. Regions of densely clustered CpGs, known as CpG islands (CGIs), occur where gene transcription is initiated (Deaton & Bird, 2011). Methylation at CGIs can lead to alterations in chromatin architecture and inhibit transcription factor binding to gene promoter regions, resulting in reduced gene expression. Consistent with this, genes such as the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) that are highly expressed typically have low levels of promoter methylation (Brenet et al., 2011; Moore, Le & Fan, 2013). Low levels of methylation typically characterize regions of the genome that are open to transcriptional regulation by methylation, such as CGIs (Deaton & Bird, 2011; Liyanage et al., 2014). In contrast, high methylation is often seen at CpG sites outside of CGIs and may have roles in genome regulation outside of genetic transcription (Hernando-Herraez et al., 2015).

Epigenetic Processes Related to HPA Functioning

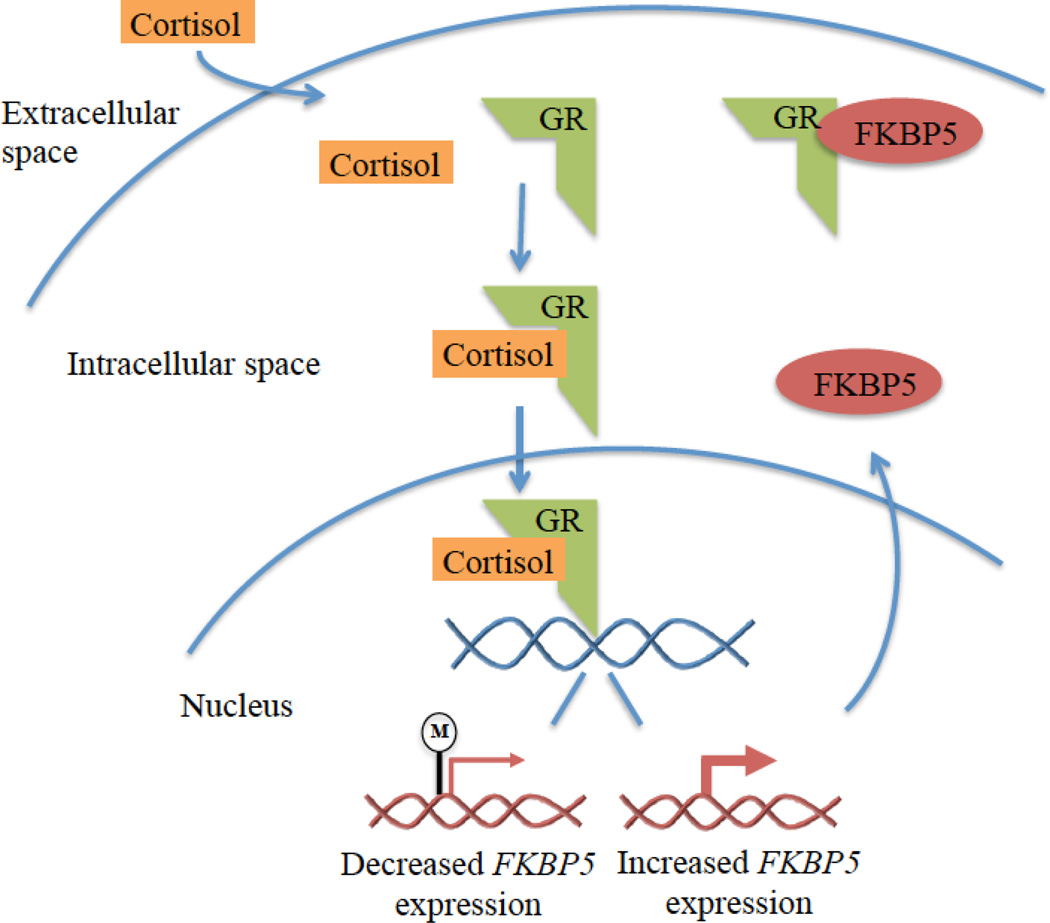

In response to stressful stimuli, the HPA axis is triggered and cortisol is released from the adrenal cortex. Cortisol exerts cellular responses by binding at the intracellular glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (Kadmiel & Cidlowski, 2013). GRs are distributed throughout the body and brain where they regulate basal physiologic function and effect changes that promote adaptive responses to acute stressors (de Kloet et al., 2005; Kadmiel & Cidlowski, 2013). Cortisol binding to the GR in the cytosol induces translocation of the GR into the nucleus (Figure 1), where it can activate and repress expression of a wide range of genes (Galon et al., 2002), thereby regulating systems necessary to cope with stressors. Interestingly, glucocorticoids induce the expression of different genes depending on the stress history of the organism (McEwen et al., 2015). In addition to impacting gene expression, cortisol binding at GRs affects cellular signaling pathways and mitochondrial function (McEwen, 2015).

Figure 1. FKBP5 and glucocorticoid signaling.

Note. Cortisol circulating through the blood stream enters the intracellular space and binds to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) to exert its effects on gene expression. Methylation of the GR gene NR3C1 reduces GR gene expression so there are fewer GRs available to bind to cortisol. FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP5) decreases sensitivity of the GR to cortisol. GR activation by cortisol binding results in rapid induction of FKBP5 gene expression, and FKBP5 then binds to the GR and decreases its ability to bind cortisol and to translocate to the nucleus. Thus, FKBP5 exerts a negative feedback loop on cortisol activity. Methylation interferes with gene expression and demethylation at intron 7 of FKBP5 is associated with increased FKBP5 gene expression and decreased GR sensitivity. Childhood maltreatment and chronic glucocorticoid administration have been linked with demethylation of FKBP5 intron 7.

As discussed above, activation of the GR through cortisol binding at the hypothalamus and pituitary also triggers a negative feedback mechanism that inhibits further cortisol release, preventing the damaging effects of chronic HPA axis activation (Herman et al., 2012; Laryea et al., 2015). Changes in GR number and function in the brain and in peripheral cells such as leukocytes have been shown with PTSD, MDD, and early stress exposure (Barden, 2004; Klengel et al., 2013; Provencal et al., 2012; van Zuiden et al., 2011; Yehuda et al., 2015b; Yehuda et al., 2010a; Yehuda & Seckl, 2011). GR-mediated negative feedback is critical to regulate the activity of the HPA axis. Alterations in GR number or function in the cell can influence the activity of this system and biological adaptation to stressful and traumatic experiences. Below, we describe how epigenetic modifications to two HPA regulatory genes, NR3C1 and FKBP5, affect GR transcription and activity, and may alter responses to stress and impart risk for psychopathology.

Childhood Adversity and Methylation of NR3C1

The human GR is encoded by the NR3C1 gene, which is located on chromosome 5q31-32, contains 8 translated exons (numbered 2 through 9) and 9 untranslated alternative first exons (Daskalakis & Yehuda, 2014). Methylation of CGIs in the GR alternative first exons controls tissue-specific expression of the GR (Turner et al., 2008) and have a role in the translational control of the GR, influencing total GR levels, as well as trafficking to the cell surface (Turner et al., 2014). There is now substantial evidence that methylation of NR3C1 is responsive to environmental exposures in both the prenatal period and during early childhood. Animal models have been highly informative for understanding mechanisms underlying links between environmental exposures, NR3C1 methylation, and subsequent gene expression. In rodents, low levels of maternal care (low frequency of licking and grooming behaviors and arched-back nursing) have been linked to greater methylation of the rodent GR gene nr3c1 in the hippocampus and cerebellum (Kosten & Nielsen, 2014; Weaver et al., 2004), specifically of the region homologous to the human alternative exon 1F. Methylation of nr3c1 in turn contributes to reduced nr3c1 gene expression. When methylation occurs at the binding site for the transcription factor nerve growth factor inducible protein A (NGFI-A), it interferes with gene transcription; methylation at other CpG sites may interfere with transcription through other mechanisms (Armstrong et al., 2014; Turner et al., 2010). Methylation of this region of nr3c1, and associated reductions in GR number and GR-mediated negative feedback, has been linked to increased glucocorticoid secretion and behavioral distress (see Zhang et al., 2013 for a review). This groundbreaking mechanistic work, coupled with evidence that both pre- and post-natal stressors contribute to methylation of nr3c1 in rodents (Kundakovic et al., 2013; Lillycrop et al., 2007; Szyf, 2013; Witzmann et al., 2012), complements research in humans reviewed below.

In humans, there is now compelling evidence that NR3C1 methylation is responsive to stress in both the pre- and post-natal periods. The majority of this work has focused on promoter methylation at exon 1F. Prenatal exposure to adverse conditions including maternal depression and anxiety, intimate partner violence, and war-related stressors (such as rape and refugee status) has been linked to increased methylation of NR3C1 at exon 1F in several studies (Braithwaite et al., 2015; Conradt et al., 2013; Hompes et al., 2013; Kertes et al., 2016; Mulligan et al., 2012; Oberlander et al., 2008; Radtke et al., 2011). Links with prenatal exposures have been demonstrated in DNA from a variety of cell types and tissues including umbilical cord blood (Hompes et al., 2013; Kertes et al., 2016; Mulligan et al., 2012; Oberlander et al., 2008), placenta (Conradt et al., 2013; Kertes et al., 2016), buccal cells in infancy (Braithwaite et al., 2015), and whole blood in adolescents (Radtke et al., 2011).

Work from our laboratory and others has also demonstrated that stress exposure in childhood is linked with methylation of NR3C1. In a sample of 99 healthy adults with no history of psychiatric disorders, our group found that early adversity including childhood maltreatment, parental loss, and low levels of parental care was associated with increased methylation of NR3C1 at exon 1F (Tyrka et al., 2012b). That these links were observed in adults with no history of psychopathology is consistent with work in our laboratory linking early adversity to cortisol production in healthy adults as described above (Carpenter et al., 2007; Carpenter et al., 2009), and suggests that early adversity exerts a lasting effect on the biological stress response system that is independent of effects of stress-related disorders or medications.

More recently, this work has been applied in children. In a study of 184 impoverished maltreated and non-maltreated preschool-aged children, we found that exposure to early adversity was linked with increased methylation of saliva DNA NR3C1 at exon 1F among preschoolers (Tyrka et al., 2015). Both past month and lifetime contextual stress assessed during an interview in the home, as well as a composite measure of adversity exposure, were positively associated with mean methylation across the region. These links were also observed at several individual CpG sites in this region, including CpG sites that are known to exert a functional effect on the HPA axis given their role as a transcription factor binding site. These findings are consistent with a recent study of older children between 11 and 14 years of age demonstrating that physical maltreatment was associated with increased methylation of NR3C1 at exon 1F in whole blood (Romens et al., 2015). Associations of childhood adversity and increased methylation of NR3C1 in blood at exon 1F have also been recently observed in a population-based sample of adolescents (van der Knaap et al., 2014). Collectively, this emerging work demonstrates compelling evidence that methylation of NR3C1 at exon 1F, is sensitive to childhood stress exposure.

A few studies have also examined methylation of alternate first exons of NR3C1 in relation to stress exposure. In our study of preschoolers with early adversity described above, we demonstrated that maltreated children had greater methylation at exon 1D in saliva DNA than preschoolers with no maltreatment history (Tyrka et al., 2015). This effect was consistent with the links observed between early adversity and methylation at exon 1F described above. Methylation at exon 1D assessed in cord blood is also sensitive to maternal pregnancy related anxiety symptoms, and is associated with maternal diurnal cortisol levels in the first trimester (Hompes et al., 2013). Exons 1B, 1C, and 1H have also been demonstrated to be sensitive to child maltreatment in postmortem hippocampal tissue of adult suicide victims (Labonte et al., 2012). Taken together, these studies suggest that although most prior work has focused on methylation of NR3C1 at exon 1F, alternate first exons in the promoter of NR3C1 also respond to stress exposure. Important questions remain regarding the functional role of each of these alternate first exons in the stress response in various tissues, and precisely how this relates to risk for psychiatric disorders.

Emerging work supports the hypothesis that methylation of NR3C1 may be a mechanism of risk for psychopathology or maladaptive behavioral outcomes among children and adults (For a review, see Palma-Gudiel et al., 2015). For example, elevations of NR3C1 methylation in DNA from whole blood have been observed in adults with borderline personality disorder (Dammann et al., 2011), and adults with both bulimia and borderline personality disorder demonstrate greater NR3C1 methylation at exon 1C, and lower methylation at exon 1H (Steiger et al., 2013). Among adults with borderline personality disorder, methylation of NR3C1 in blood is positively associated with clinical severity (Martin-Blanco et al., 2014). In contrast, lower methylation of NR3C1 in blood has also been observed in adults with MDD, PTSD, and externalizing disorders (Heinrich et al., 2015; Labonte et al., 2014; Na et al., 2014; Yehuda et al., 2015b).

These links to behavioral outcomes have also been seen in childhood and adolescence. In newborns, NR3C1 methylation is associated with decreased quality of movement and self-regulation, increased arousal and excitability, and increased non-optimal reflexes and stress abstinence scores (Paquette et al., 2015). In our own work with preschoolers we recently demonstrated that methylation of NR3C1 in saliva DNA is associated with the development of internalizing behavior problems, and methylation of NR3C1 mediates links between early adversity and internalizing behavior problems (Parade et al., 2016). Likewise, NR3C1 methylation is positively associated with internalizing problems in adolescence (van der Knaap et al., 2015) and both internalizing problems and morning cortisol levels in childhood and adolescence (Dadds et al., 2015). This work is complemented by animal models demonstrating that methylation of NR3C1 is linked with increased anxiety-like behaviors in rodents (Kosten, Huang & Nielsen, 2014; Lutz & Turecki, 2014; Pan et al., 2014). Taken together, this emerging body of literature supports the hypothesis that methylation of NR3C1 is linked with the development of behavioral difficulties in childhood. Furthermore, this work suggests that NR3C1 methylation is potential mechanism underlying the development of psychopathology among children and adults exposed to early adversity.

Childhood Adversity and Methylation of FKBP5

In addition to NR3C1, an important regulator of the GR is the FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP5), which mediates an additional negative feedback loop on glucocorticoids. GR activation results in rapid induction of FKBP5, which binds to the GR and decreases its ability to bind cortisol and to translocate to the nucleus (Figure 1). Thus, FKBP5 decreases systemic sensitivity to cortisol and may also impair GR-mediated negative feedback modulation of the HPA axis (Binder, 2009; Cioffi, Hubler & Scammell, 2011; Schmidt et al., 2015; Tatro et al., 2009), and methylation of the FKBP5 gene, with associated reductions in transcription, might limit these effects. Genetic variation in FKBP5 confers altered GR function and a poorly regulated neuroendocrine response to stress (Zannas & Binder, 2014). A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in FKBP5 (C to T SNP in intron 2, rs1360780) enhances the ability of the GR to bind to the glucocorticoid response elements and induce FKBP5 expression (Zannas & Binder, 2014). This “risk” T allele is associated with GR resistance (Hohne et al., 2015; Ising et al., 2008; Menke et al., 2013) and has been linked with PTSD, depressive and anxiety symptoms and disorders, and suicide (Leszczynska-Rodziewicz et al., 2014; Suzuki et al., 2014; Szczepankiewicz et al., 2014; VanZomeren-Dohm et al., 2015; Zannas & Binder, 2014).

Recent work by Klengel and colleagues (Klengel et al., 2013) examined the rs1360780 SNP and methylation of FKBP5 in relation to childhood maltreatment. Compared to adults with no childhood abuse, those with a history of childhood maltreatmend had lower levels of methylation in the regulatory regions of intron 7 of FKBP5 in those with the rs1360780 risk allele, and this was associated with decreased GR sensitivity. Moreover, treatment of human hippocampal progenitor cells with glucocorticoids induced long-lasting demethylation of this regulatory region and increased FKBP5 gene expression, suggesting that prolonged cortisol exposure may be a mechanism by which this region is demethylated (Klengel et al., 2013). In our study of preschoolers with early adversity, we also found that child maltreatment was associated with lower levels of FKBP5 intron 7 methylation in saliva DNA, however rs1360780 was not a significant moderator of this association (Tyrka et al., 2015). These findings of FKBP5 demethyation in association with childhood maltreatment are in contrast to recent work suggesting that low childhood socioeconomic status is associated with increased FKBP5 methylation (Needham et al., 2015). It is possible that low socioeconomic status in the absence of other adversities activates the HPA system to initially increase methylation but does not contribute to demethylation over time. A recent study found methylation of FKBP5 was correlated in Holocaust survivors and their offspring; survivors also showed greater methylation of FKBP5 in comparison with participants who were not Holocaust survivors, whereas the children of these survivors exhibited low levels of methylation (Yehuda et al., 2015a). This study suggested the possibility of intergenerational effects of trauma exposure. Weder and colleagues (Weder et al., 2014) found links between child maltreatment and methylation of a different region of FKBP5 in saliva DNA among children 5–14 years of age using a 450K methylation array. Although more work is needed to understand the conditions under which adversity is linked with hyper- or hypo-methylation of FKBP5 and which regions and variants of this gene are critically involved, this emerging literature suggests that stress-induced changes in methylation of FKBP5 may play a key role in long-term alterations of glucocorticoid activity.

Methylation of FKBP5 at intron 7 has also been linked to behavioral outcomes. Among neonates, placental methylation of FKBP5 at intron 7 was associated with higher levels of arousal during a physical examination (Paquette et al., 2014). Patients with bipolar disorder, particularly those with a late stage of illness, had increased post-dexamethasone cortisol levels compared to those without bipolar disorder, as well as higher levels of the FKBP5 protein and higher levels of FKBP5 methylation (Fries et al., 2015). These studies suggest the possibility that methylation of FKBP5 could be a mechanism underlying links between adversity and behavioral health outcomes. However, more work is needed to replicate these findings and clarify patterns of methylation and demethylation in relation to stress exposures, glucocorticoid activation, and risk for various forms of psychopathology.

Summary: Childhood Adversity and Methylation of Glucocorticoid Signaling Genes

Taken together, this emerging literature indicates that childhood adversity is associated with altered methylation patterns in regulatory regions of both NR3C1 and FKBP5. Activity of these genes plays a vital role in the regulation and function of the HPA axis, and could account for some of the findings of adversity-related abnormalities in basal and provoked cortisol levels and risk for psychopathology. Regulation of these systems is complex and adaptive, and more work is needed to understand the conditions under which methylation is promoted or inhibited. It is also critical to recognize that epigenetic modulation of other genes involved in glucocorticoid signaling and other pathways are likely involved in these processes (e.g., (Weder et al., 2014).

Relevance of Epigenetics for Inventions to Address Childhood Adversity

Recent calls have been made to integrate biological measures of program efficacy into evaluations of preventative interventions for children at risk (Bruce et al., 2013; Cicchetti & Gunnar, 2008; Moffitt & Klaus-Grawe 2012 Think Tank, 2013). Several studies have shown normalizing effects of psychosocial interventions on diurnal or provoked cortisol levels in children exposed to significant adversity (e.g., Cicchetti et al., 2011; Dozier et al., 2008; Fisher et al., 2007; Fisher, Van Ryzin & Gunnar, 2011; Laurent et al., 2014; Nelson & Spieker, 2013; Slopen, McLaughlin & Shonkoff, 2014; van Andel et al., 2014). Altered methylation of glucocorticoid signaling genes including NR3C1 and FKBP5 may underlie adversity-induced HPA axis dysfunction and interventions might stably alter these methylation patterns. Given the complexity in the genetic regulation of HPA axis function, different methylation patterns may explain inconsistencies in the literature on cortisol, early stress, and psychiatric illness. Consideration of alterations in gene methylation would complement examination of behavioral and endocrine outcomes in intervention trials. Furthermore, understanding whether effective behavioral interventions reverse effects of adversity on gene methylation will inform the basic science of biological pathways contributing to risk and resilience.

Although methylation is thought to be the most stable form of epigenetic modification, there is evidence that gene methylation may be plastic during childhood and into adulthood. Therapeutic interventions may alter methylation patterns and could reduce the biologic risk engendered by early life adversity (Szyf, 2015). There is preliminary evidence that methylation of genes involved in the stress response system might serve as biomarkers of treatment response for psychiatric disorders. In children, FKBP5 DNA methylation was significantly associated with treatment response to a cognitive behavioral therapy-based intervention for anxiety disorders (Roberts et al., 2015). Specifically, children with a smaller reduction in symptoms showed an increase in DNA methylation while children with a larger symptom reduction showed a decrease in DNA methylation. When corrected for multiple testing, the association between DNA methylation and treatment response remained significant in participants with the “risk” T FKPB5 genotype. Likewise, in a pilot study, pre-treatment methylation of the NR3C1 exon 1F promoter predicted treatment response to prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD in combat veterans; in addition, FKBP5 promoter methylation decreased and FKBP5 expression increased in association with recovery (Yehuda et al., 2013). Future studies are warranted to understand how methylation changes in response to psychosocial interventions, and if methylation is potential marker for the efficacy of intervention.

Several drugs can alter methylation patterns across the lifespan. Trichostatin A is a compound that inhibits enzymes involved in epigenetic processes that decrease gene expression. In rats, treatment with trichostatin A reversed the decreased gene expression that was imparted by neglect in early life; this reversal was associated with decreased behavioral phenotypes of depression and anxiety (Weaver, Meaney & Szyf, 2006). Conversely, treatment with methionine, a compound that is known to increase gene methylation, suppressed gene expression in rats with high levels of early life maternal care and was associated with increased depressive and anxious behaviors (Weaver et al., 2006). A number of medications commonly used in psychiatry, including clozapine, sulpiride, and valproic acid, have been shown to actively promote demethylation in cell culture (Detich, Bovenzi & Szyf, 2003a; Milutinovic et al., 2007) and in mouse brain (Dong et al., 2010; Dong et al., 2008). Antidepressants have been associated with changes in DNA methylation (Menke & Binder, 2014). The DNA methylation inhibitors zebularine and 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine reverse DNA methylation and block synaptic long-term potentiation in mouse hippocampal slices (Levenson et al., 2006) as well as fear memory formation (Miller & Sweatt, 2007). Another potential therapeutic approach is to modify the intracellular environment such that it promotes demethylation. The methyl donor, S-adenosine methionine (SAM) inhibits demethylase activity (Detich et al., 2003b). Levels of SAM are controlled in part by dietary intake of folic acid and vitamin B12 (Bottiglieri, 2013). Both the presence of Ca2+ as well as the redox state of the cell can influence demethylase activity (Szyf, 2015). Finally, exercise modulates changes in DNA methylation associated with stress exposure (Kashimoto et al., 2016; Rodrigues et al., 2015), suggesting that physical activity interventions may have a role in modifying the effects of early adversity on gene methylation. Together, these findings suggest that interventions or treatments that interfere with or reverse DNA methylation could potentially modify the risk for psychopathology imparted by early life adversity.

Directions for Future Research

Despite accumulating knowledge of the role of epigenetics and glucocorticoid signaling in the biological response to environmental risk and protection, many questions remain regarding the biological processes underlying these links. First, a basic understanding of how methylation of glucocorticoid signaling genes longitudinally changes over time has yet to be achieved, with little understanding of the role of risk and protective factors that impact these developmental trajectories. Understanding how methylation patterns change across developmental stages, and whether there are sensitive periods of development for changes in methylation as a consequence of environmental exposures, is a critical next step. Knowledge of how quickly methylation occurs in response to adversity and which genes and gene networks have the largest effects is lacking. Elucidation of these influences and determinants would serve to identify the most critical developmental periods for intervention, as well as the length of time and intensity of services needed to reverse effects of adversity on methylation. Thus, many questions remain to be answered before knowledge of the basic science of epigenetic processes can be translated into the most effective clinical interventions for children exposed to adversity.

In addition to the longitudinal examination of change in methylation over time, examining links between methylation and environmental exposures from a transactional perspective is an important next step. It is well established that development is best characterized by transactional relationships between the child and their environment, such that the environment exerts influence on the child and the child in turn exerts influence on the environment over time (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993; Combs-Ronto et al., 2009). Although historically focused on child behavior such as temperament, emerging work considering transactive effects suggests that child biological stress responding has the potential to exert influence on the environment, in this case parental behavior, through transactional relationships as well (e.g.(Perry et al., 2014). Examining the longitudinal course of methylation through a transactional lens would allow us to understand how the environment influences methylation and methylation in turn potentially exerts influence on the environment. As an example, compromised parental behavior may contribute to methylation of glucocorticoid signaling genes in the child, resulting in child behavior problems that evoke parental stress and further undermine sensitive parenting. Parenting stress related to child behavior problems might contribute to change in gene methylation patterns among parents as well.

Future work should also aim to understand the role of epigenetics in resilience processes. It is possible that alterations in methylation associated with adversity have the potential to be adaptive. For example, in male Rwandan genocide survivors, increased NR3C1 promoter DNA methylation was associated with reduced risk for PTSD, and less intrusive memories of trauma (Vukojevic et al., 2014). This work in conjunction with emerging literature suggesting that MDD, PTSD, and externalizing disorders can be linked with reduced NR3C1 methylation (Heinrich et al., 2015; Labonte et al., 2014; Na et al., 2014; Yehuda et al., 2015b) suggests that increases in NR3C1 methylation are not always markers of risk. Future work should also begin to examine potential moderators of the links between early adversity and methylation, and methylation and behavioral outcomes. For example, parental sensitivity and responsiveness may buffer children from effects of early adversity on methylation, and may promote adaptive behavioral outcomes even when adversity alters methylation (Conradt et al., 2016).

Finally, the consideration of epigenetic processes in response to environmental exposures has typically either focused on environment in the prenatal period or environment following birth with few studies concurrently examining both prenatal and postnatal factors to contribute to methylation of glucocorticoid signaling genes. Consideration of environmental risk from the pre-conception period through the postnatal period and childhood is critical for understanding potential sensitive periods during which adversity is biologically encoded, as well as to uncover the most opportune times to intervene with children and families at risk.

Conclusion

Accumulating knowledge supports the perspective that childhood adversity undermines children’s health across the lifespan. As reviewed above, methylation of glucocorticoid signaling genes including NR3C1 and FKBP5 are increasingly recognized as potential mechanisms by which childhood adversity is biologically encoded. Although exponential progress has been made over the past decade to understand these epigenetic processes, critical gaps in knowledge remain in our understanding of methylation across typical development and in the face of early adversity. Advancing understanding of these processes will inform prevention and intervention efforts aimed at enhancing the lives of the most vulnerable children and families.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by R01 MH101107 (ART), R01 MH083704 (ART), R25 MH101076 (KKR), and Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Grant 21296 (SHP).

References

- Anacker C, Zunszain PA, Carvalho LA, Pariante CM. The glucocorticoid receptor: pivot of depression and of antidepressant treatment? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(3):415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DA, Lesseur C, Conradt E, Lester BM, Marsit CJ. Global and gene-specific DNA methylation across multiple tissues in early infancy: implications for children's health research. The FASEB Journal. 2014;28(5):2088–2097. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-238402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barden N. Implication of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the physiopathology of depression. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2004;29(3):185–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME. Chronic childhood adversity and onset of psychopathology during three life stages: childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44(11):732–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Hostinar CE, Dozier M. Intervention effects on diurnal cortisol rhythms of Child Protective Services-referred infants in early childhood: preschool follow-up results of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(2):112–119. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Zwerling J, Dozier M. Effects of early adversity on young children's diurnal cortisol rhythms and externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychobiology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/dev.21324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder EB. The role of FKBP5, a co-chaperone of the glucocorticoid receptor in the pathogenesis and therapy of affective and anxiety disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Supplement 1):S186–S195. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss EB, Janssen WG, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Interactive effects of stress and aging on structural plasticity in the prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(19):6726–6731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0759-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch NM, Riese H, Reijneveld SA, Bakker MP, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ. Timing matters: long term effects of adversities from prenatal period up to adolescence on adolescents' cortisol stress response. The TRAILS study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(9):1439–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottiglieri T. Folate, vitamin B(1)(2), and S-adenosylmethionine. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2013;36(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite EC, Kundakovic M, Ramchandani PG, Murphy SE, Champagne FA. Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms predict infant NR3C1 1F and BDNF IV DNA methylation. Epigenetics. 2015;10(5):408–417. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1039221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braquehais MD, Picouto MD, Casas M, Sher L. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction as a neurobiological correlate of emotion dysregulation in adolescent suicide. World Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;8(3):197–206. doi: 10.1007/s12519-012-0358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenet F, Moh M, Funk P, Feierstein E, Viale AJ, Socci ND, Scandura JM. DNA methylation of the first exon is tightly linked to transcriptional silencing. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e14524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, Giles WH. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(5):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce J, Fisher PA, Graham AM, Moore WE, Peake SJ, Mannering AM. Patterns of brain activation in foster children and nonmaltreated children during an inhibitory control task. Developmental Psychopathology. 2013;25(4 Pt 1):931–941. doi: 10.1017/S095457941300028X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LL, Carvalho JP, Tyrka AR, Wier LM, Mello AF, Mello MF, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW, Price LH. Decreased adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol responses to stress in healthy adults reporting significant childhood maltreatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(10):1080–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LL, Shattuck TT, Tyrka AR, Geracioti TD, Price LH. Effect of childhood physical abuse on cortisol stress response. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214(1):367–375. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR, Ross NS, Khoury L, Anderson GM, Price LH. Effect of childhood emotional abuse and age on cortisol responsivity in adulthood. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Gunnar MR. Integrating biological measures into the design and evaluation of preventive interventions. Developmental Psychopathology. 2008;20(3):737–743. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: consequences for children's development. Psychiatry. 1993;56(1):96–118. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL, Sturge-Apple ML. Normalizing the development of cortisol regulation in maltreated infants through preventive interventions. Developmental Psychopathology. 2011;23(3):789–800. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi DL, Hubler TR, Scammell JG. Organization and function of the FKBP52 and FKBP51 genes. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2011;11(4):308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685–1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs-Ronto LA, Olson SL, Lunkenheimer ES, Sameroff AJ. Interactions between maternal parenting and children's early disruptive behavior: bidirectional associations across the transition from preschool to school entry. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(8):1151–1163. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9332-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt E, Hawes K, Guerin D, Armstrong DA, Marsit CJ, Tronick E, Lester BM. The Contributions of Maternal Sensitivity and Maternal Depressive Symptoms to Epigenetic Processes and Neuroendocrine Functioning. Child Development. 2016;87(1):73–85. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt E, Lester BM, Appleton AA, Armstrong DA, Marsit CJ. The roles of DNA methylation of NR3C1 and 11beta-HSD2 and exposure to maternal mood disorder in utero on newborn neurobehavior. Epigenetics. 2013;8(12):1321–1329. doi: 10.4161/epi.26634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Moul C, Hawes DJ, Mendoza Diaz A, Brennan J. Individual Differences in Childhood Behavior Disorders Associated With Epigenetic Modulation of the Cortisol Receptor Gene. Child Development. 2015;86(5):1311–1320. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann G, Teschler S, Haag T, Altmuller F, Tuczek F, Dammann RH. Increased DNA methylation of neuropsychiatric genes occurs in borderline personality disorder. Epigenetics. 2011;6(12):1454–1462. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.12.18363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis NP, Yehuda R. Site-specific methylation changes in the glucocorticoid receptor exon 1F promoter in relation to life adversity: systematic review of contributing factors. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2014;8:369. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Zisk A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2014;23(2):185–222. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6(6):463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton AM, Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes & Development. 2011;25(10):1010–1022. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detich N, Bovenzi V, Szyf M. Valproate induces replication-independent active DNA demethylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003a;278(30):27586–27592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detich N, Hamm S, Just G, Knox JD, Szyf M. The methyl donor S-Adenosylmethionine inhibits active demethylation of DNA: a candidate novel mechanism for the pharmacological effects of S-Adenosylmethionine. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003b;278(23):20812–20820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Chen Y, Gavin DP, Grayson DR, Guidotti A. Valproate induces DNA demethylation in nuclear extracts from adult mouse brain. Epigenetics. 2010;5(8):730–735. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.8.13053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Nelson M, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A. Clozapine and sulpiride but not haloperidol or olanzapine activate brain DNA demethylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2008;105(36):13614–13619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doom JR, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Longitudinal patterns of cortisol regulation differ in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(11):1206–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doom JR, Gunnar MR. Stress physiology and developmental psychopathology: past, present, and future. Developmental Psychopathology. 2013;25(4 Pt 2):1359–1373. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Peloso E, Lewis E, Laurenceau JP, Levine S. Effects of an attachment-based intervention on the cortisol production of infants and toddlers in foster care. Developmental Psychopathology. 2008;20(3):845–859. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS. Neuronal damage and protection in the pathophysiology and treatment of psychiatric illness: stress and depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;11(3):239–255. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/rsduman. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga BM, Roelofs K, Tollenaar MS, Bakvis P, van Pelt J, Spinhoven P. Diminished cortisol responses to psychosocial stress associated with lifetime adverse events a study among healthy young subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(2):227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faravelli C, Lo Sauro C, Lelli L, Pietrini F, Lazzeretti L, Godini L, Benni L, Fioravanti G, Talamba GA, Castellini G, Ricca V. The role of life events and HPA axis in anxiety disorders: a review. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2012;18(35):5663–5674. doi: 10.2174/138161212803530907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M, Gunnar MR, Burraston BO. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster preschoolers on diurnal cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(8–10):892–905. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Van Ryzin MJ, Gunnar MR. Mitigating HPA axis dysregulation associated with placement changes in foster care. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):531–539. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries E, Hesse J, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(10):1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries GR, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Gubert C, dos Santos BT, Sartori J, Eisele B, Ferrari P, Fijtman A, Ruegg J, Gassen NC, Kapczinski F, Rein T, Kauer-Sant'Anna M. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and illness progression in bipolar disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;18(1) doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J, Franchimont D, Hiroi N, Frey G, Boettner A, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, O'Shea JJ, Chrousos GP, Bornstein SR. Gene profiling reveals unknown enhancing and suppressive actions of glucocorticoids on immune cells. The FASEB Journal. 2002;16(1):61–71. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0245com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A. The impact of childhood maltreatment on biological systems: Implications for clinical interventions. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2013;18(8):415–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormley GJ, Lowy MT, Reder AT, Hospelhorn VD, Antel JP, Meltzer HY. Glucocorticoid receptors in depression: relationship to the dexamethasone suppression test. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142(11):1278–1284. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerry JD, Hastings PD. In search of HPA axis dysregulation in child and adolescent depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(2):135–160. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Vazquez DM. Low cortisol and a flattening of expected daytime rhythm: potential indices of risk in human development. Developmental Psychopathology. 2001;13(3):515–538. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(1):1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich A, Buchmann AF, Zohsel K, Dukal H, Frank J, Treutlein J, Nieratschker V, Witt SH, Brandeis D, Schmidt MH, Esser G, Banaschewski T, Laucht M, Rietschel M. Alterations of Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene Methylation in Externalizing Disorders During Childhood and Adolescence. Behavior Genetics. 2015;45(5):529–536. doi: 10.1007/s10519-015-9721-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Solomon MB, Carvalho-Netto E, Myers B. Neural regulation of the stress response: glucocorticoid feedback mechanisms. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2012;45(4):292–298. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernando-Herraez I, Garcia-Perez R, Sharp AJ, Marques-Bonet T. DNA Methylation: Insights into Human Evolution. PLoS Genetics. 2015;11(12):e1005661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohne N, Poidinger M, Merz F, Pfister H, Bruckl T, Zimmermann P, Uhr M, Holsboer F, Ising M. FKBP5 genotype-dependent DNA methylation and mRNA regulation after psychosocial stress in remitted depression and healthy controls. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;18(4) doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hompes T, Izzi B, Gellens E, Morreels M, Fieuws S, Pexsters A, Schops G, Dom M, Van Bree R, Freson K, Verhaeghe J, Spitz B, Demyttenaere K, Glover V, Van den Bergh B, Allegaert K, Claes S. Investigating the influence of maternal cortisol and emotional state during pregnancy on the DNA methylation status of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) promoter region in cord blood. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47(7):880–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising M, Depping AM, Siebertz A, Lucae S, Unschuld PG, Kloiber S, Horstmann S, Uhr M, Muller-Myhsok B, Holsboer F. Polymorphisms in the FKBP5 gene region modulate recovery from psychosocial stress in healthy controls. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(2):389–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadmiel M, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling in health and disease. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2013;34(9):518–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashimoto RK, Toffoli LV, Manfredo MH, Volpini VL, Martins-Pinge MC, Pelosi GG, Gomes MV. Physical exercise affects the epigenetic programming of rat brain and modulates the adaptive response evoked by repeated restraint stress. Behavioural Brain Research. 2016;296:286–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertes DA, Kamin HS, Hughes DA, Rodney NC, Bhatt S, Mulligan CJ. Prenatal Maternal Stress Predicts Methylation of Genes Regulating the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical System in Mothers and Newborns in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Child Development. 2016;87(1):61–72. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassens ER, Giltay EJ, van Veen T, Veen G, Zitman FG. Trauma exposure in relation to basal salivary cortisol and the hormone response to the dexamethasone/CRH test in male railway employees without lifetime psychopathology. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(6):878–886. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassens ER, van Noorden MS, Giltay EJ, van Pelt J, van Veen T, Zitman FG. Effects of childhood trauma on HPA-axis reactivity in women free of lifetime psychopathology. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2009;33(5):889–894. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klengel T, Mehta D, Anacker C, Rex-Haffner M, Pruessner JC, Pariante CM, Pace TW, Mercer KB, Mayberg HS, Bradley B, Nemeroff CB, Holsboer F, Heim CM, Ressler KJ, Rein T, Binder EB. Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene-childhood trauma interactions. Nature Neuroscience. 2013;16(1):33–41. doi: 10.1038/nn.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Huang W, Nielsen DA. Sex and litter effects on anxiety and DNA methylation levels of stress and neurotrophin genes in adolescent rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 2014;56(3):392–406. doi: 10.1002/dev.21106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Nielsen DA. Litter and sex effects on maternal behavior and DNA methylation of the Nr3c1 exon 17 promoter gene in hippocampus and cerebellum. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2014;36:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic M, Lim S, Gudsnuk K, Champagne FA. Sex-specific and strain-dependent effects of early life adversity on behavioral and epigenetic outcomes. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2013;4:78. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labonte B, Azoulay N, Yerko V, Turecki G, Brunet A. Epigenetic modulation of glucocorticoid receptors in posttraumatic stress disorder. Translational Psychiatry. 2014;4:e368. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labonte B, Yerko V, Gross J, Mechawar N, Meaney MJ, Szyf M, Turecki G. Differential glucocorticoid receptor exon 1(B), 1(C), and 1(H) expression and methylation in suicide completers with a history of childhood abuse. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarasimhan H, Chattarji S. Stress leads to contrasting effects on the levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor in the hippocampus and amygdala. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laryea G, Muglia L, Arnett M, Muglia LJ. Dissection of glucocorticoid receptor-mediated inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by gene targeting in mice. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2015;36:150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Gilliam KS, Bruce J, Fisher PA. HPA stability for children in foster care: mental health implications and moderation by early intervention. Developmental Psychobiology. 2014;56(6):1406–1415. doi: 10.1002/dev.21226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RS, Sawa A. Environmental stressors and epigenetic control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Neuroendocrinology. 2014;100(4):278–287. doi: 10.1159/000369585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leszczynska-Rodziewicz A, Szczepankiewicz A, Narozna B, Skibinska M, Pawlak J, Dmitrzak-Weglarz M, Hauser J. Possible association between haplotypes of the FKBP5 gene and suicidal bipolar disorder, but not with melancholic depression and psychotic features, in the course of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2014;10:243–248. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S54538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson JM, Roth TL, Lubin FD, Miller CA, Huang IC, Desai P, Malone LM, Sweatt JD. Evidence that DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferase regulates synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(23):15763–15773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillycrop KA, Slater-Jefferies JL, Hanson MA, Godfrey KM, Jackson AA, Burdge GC. Induction of altered epigenetic regulation of the hepatic glucocorticoid receptor in the offspring of rats fed a protein-restricted diet during pregnancy suggests that reduced DNA methyltransferase-1 expression is involved in impaired DNA methylation and changes in histone modifications. British Journal of Nutrition. 2007;97(6):1064–1073. doi: 10.1017/S000711450769196X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage VR, Jarmasz JS, Murugeshan N, Del Bigio MR, Rastegar M, Davie JR. DNA modifications: function and applications in normal and disease States. Biology (Basel) 2014;3(4):670–723. doi: 10.3390/biology3040670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy MT, Reder AT, Gormley GJ, Meltzer HY. Comparison of in vivo and in vitro glucocorticoid sensitivity in depression: relationship to the dexamethasone suppression test. Biological Psychiatry. 1988;24(6):619–630. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(6):434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz PE, Turecki G. DNA methylation and childhood maltreatment: from animal models to human studies. Neuroscience. 2014;264:142–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccari S, Krugers HJ, Morley-Fletcher S, Szyf M, Brunton PJ. The consequences of early-life adversity: neurobiological, behavioural and epigenetic adaptations. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2014;26(10):707–723. doi: 10.1111/jne.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Blanco A, Ferrer M, Soler J, Salazar J, Vega D, Andion O, Sanchez-Mora C, Arranz MJ, Ribases M, Feliu-Soler A, Perez V, Pascual JC. Association between methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene, childhood maltreatment, and clinical severity in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;57:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E. Research review: the neurobiology and genetics of maltreatment and adversity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(10):1079–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87(3):873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. The Brain on Stress: Toward an Integrative Approach to Brain, Body, and Behavior. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(6):673–675. doi: 10.1177/1745691613506907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Preserving neuroplasticity: Role of glucocorticoids and neurotrophins via phosphorylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2015;112(51):15544–15545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521416112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Bowles NP, Gray JD, Hill MN, Hunter RG, Karatsoreos IN, Nasca C. Mechanisms of stress in the brain. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18(10):1353–1363. doi: 10.1038/nn.4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Nasca C, Gray JD. Stress Effects on Neuronal Structure: Hippocampus, Amygdala, and Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(1):3–23. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke A, Binder EB. Epigenetic alterations in depression and antidepressant treatment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2014;16(3):395–404. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.3/amenke. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke A, Klengel T, Rubel J, Bruckl T, Pfister H, Lucae S, Uhr M, Holsboer F, Binder EB. Genetic variation in FKBP5 associated with the extent of stress hormone dysregulation in major depression. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2013;12(3):289–296. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Sweatt JD. Covalent modification of DNA regulates memory formation. Neuron. 2007;53(6):857–869. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(1):25–45. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milutinovic S, D'Alessio AC, Detich N, Szyf M. Valproate induces widespread epigenetic reprogramming which involves demethylation of specific genes. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(3):560–571. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra R, Sapolsky RM. Acute corticosterone treatment is sufficient to induce anxiety and amygdaloid dendritic hypertrophy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2008;105(14):5573–5578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705615105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE Klaus-Grawe 2012 Think Tank. Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: clinical intervention science and stress-biology research join forces. Developmental Psychopathology. 2013;25(4 Pt 2):1619–1634. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):23–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Compas BE, Garber J. Relations among posttraumatic stress disorder, comorbid major depression, and HPA function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(4):301–315. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan CJ, D'Errico NC, Stees J, Hughes DA. Methylation changes at NR3C1 in newborns associate with maternal prenatal stress exposure and newborn birth weight. Epigenetics. 2012;7(8):853–857. doi: 10.4161/epi.21180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na KS, Chang HS, Won E, Han KM, Choi S, Tae WS, Yoon HK, Kim YK, Joe SH, Jung IK, Lee MS, Ham BJ. Association between glucocorticoid receptor methylation and hippocampal subfields in major depressive disorder. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL, Smith JA, Zhao W, Wang X, Mukherjee B, Kardia SL, Shively CA, Seeman TE, Liu Y, Diez Roux AV. Life course socioeconomic status and DNA methylation in genes related to stress reactivity and inflammation: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Epigenetics. 2015;10(10):958–969. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1085139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EM, Spieker SJ. Intervention Effects on Morning and Stimulated Cortisol Responses Among Toddlers in Foster Care. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2013;34(3) doi: 10.1002/imhj.21382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3(2):97–106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma-Gudiel H, Cordova-Palomera A, Leza JC, Fananas L. Glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) methylation processes as mediators of early adversity in stress-related disorders causality: A critical review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015;55:520–535. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan P, Fleming AS, Lawson D, Jenkins JM, McGowan PO. Within- and between-litter maternal care alter behavior and gene regulation in female offspring. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;128(6):736–748. doi: 10.1037/bne0000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette AG, Lester BM, Koestler DC, Lesseur C, Armstrong DA, Marsit CJ. Placental FKBP5 genetic and epigenetic variation is associated with infant neurobehavioral outcomes in the RICHS cohort. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette AG, Lester BM, Lesseur C, Armstrong DA, Guerin DJ, Appleton AA, Marsit CJ. Placental epigenetic patterning of glucocorticoid response genes is associated with infant neurodevelopment. Epigenomics. 2015;7(5):767–779. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parade SH, Ridout KK, Seifer R, Armstrong DA, Marsit CJ, McWilliams MA, Tyrka AR. Methylation of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene Promoter in Preschoolers: Links With Internalizing Behavior Problems. Child Development. 2016;87(1):86–97. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry NB, Mackler JS, Calkins SD, Keane SP. A transactional analysis of the relation between maternal sensitivity and child vagal regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(3):784–793. doi: 10.1037/a0033819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencal N, Suderman MJ, Guillemin C, Massart R, Ruggiero A, Wang D, Bennett AJ, Pierre PJ, Friedman DP, Cote SM, Hallett M, Tremblay RE, Suomi SJ, Szyf M. The signature of maternal rearing in the methylome in rhesus macaque prefrontal cortex and T cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(44):15626–15642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1470-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryce CR, Ruedi-Bettschen D, Dettling AC, Weston A, Russig H, Ferger B, Feldon J. Long-term effects of early-life environmental manipulations in rodents and primates: Potential animal models in depression research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29(4–5):649–674. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke KM, Ruf M, Gunter HM, Dohrmann K, Schauer M, Meyer A, Elbert T. Transgenerational impact of intimate partner violence on methylation in the promoter of the glucocorticoid receptor. Translational Psychiatry. 2011;1:e21. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RP, Anilkumar S, McEwen BS, Chattarji S. Glucocorticoids protect against the delayed behavioral and cellular effects of acute stress on the amygdala. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72(6):466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis FM, Almada RC, Fogaca MV, Brandao ML. Rapid Activation of Glucocorticoid Receptors in the Prefrontal Cortex Mediates the Expression of Contextual Conditioned Fear in Rats. Cerebral Cortex. 2015 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout KK, Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR. The Cellular Sequelae of Early Stress: Focus on Aging and Mitochondria. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(1):388–389. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout SJ, Ridout KK, Kao HT, Carpenter LL, Philip NS, Tyrka AR, Price LH. Telomeres, early-life stress and mental illness. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine. 2015;34:92–108. doi: 10.1159/000369088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]