Abstract

Objective

A systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the impact of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and/or electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS) versus no smoking cessation aid, or alternative smoking cessation aids, in cigarette smokers on long-term tobacco use.

Data sources

Searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycInfo, CINAHL, CENTRAL and Web of Science up to December 2015.

Study selection

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective cohort studies.

Data extraction

Three pairs of reviewers independently screened potentially eligible articles, extracted data from included studies on populations, interventions and outcomes and assessed their risk of bias. We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to rate overall certainty of the evidence by outcome.

Data synthesis

Three randomised trials including 1007 participants and nine cohorts including 13 115 participants proved eligible. Results provided by only two RCTs suggest a possible increase in tobacco smoking cessation with ENDS in comparison with ENNDS (RR 2.03, 95% CI 0.94 to 4.38; p=0.07; I2=0%, risk difference (RD) 64/1000 over 6 to 12 months, low-certainty evidence). Results from cohort studies suggested a possible reduction in quit rates with use of ENDS compared with no use of ENDS (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.00; p=0.051; I2=56%, very low certainty).

Conclusions

There is very limited evidence regarding the impact of ENDS or ENNDS on tobacco smoking cessation, reduction or adverse effects: data from RCTs are of low certainty and observational studies of very low certainty. The limitations of the cohort studies led us to a rating of very low-certainty evidence from which no credible inferences can be drawn. Lack of usefulness with regard to address the question of e-cigarettes' efficacy on smoking reduction and cessation was largely due to poor reporting. This review underlines the need to conduct well-designed trials measuring biochemically validated outcomes and adverse effects.

Keywords: electronic cigarettes, ENDS, smoking cessation, GRADE, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strengths of our review include a comprehensive search; assessment of eligibility, risk of bias and data abstraction independently and in duplicate; assessment of risk of bias that included a sensitivity analysis addressing loss to follow-up; and use of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach in rating the certainty of evidence for each outcome.

The primary limitation of our review is the low certainty consequent on study limitations. Moreover, loss to follow-up was substantial, and our sensitivity analysis demonstrated the vulnerability of borderline effects to missing data. The limitations of the cohort studies led us to a rating of very low-certainty evidence from which no credible inferences can be drawn.

The small number of studies made it impossible to address our subgroup hypotheses related dose–response of nicotine, more versus less frequent use of e-cigarettes or the relative impact of newer versus older e-cigarette models.

Introduction

Tobacco smokers who quit their habit reduce their risk of developing and dying from tobacco-related diseases.1–4 Psychosocial5–7 and pharmacological interventions (eg, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT))5–7 increase the likelihood of quitting cigarettes. Even with these aids, however, most smokers fail to quit.

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS) represent a potential third option for those seeking to stop smoking. ENDS are devices that deliver nicotine in an aerosolised form, while ENNDS devices are labelled as not containing nicotine (though labelling may not always be accurate). In theory, these devices as well as the nicotine inhalers may facilitate quitting smoking to a greater degree than other nicotine-based products or no intervention because they deal, at least partly, with the behavioural and sensory aspects of smoking addiction (eg, hand mouth movement).8 The debate about the role of ENDS in smoking cessation, however, is compounded by the lack of clear evidence about their value as a smoking cessation tool, their potential to hook tobacco-naïve youth on nicotine as well as act as a bridge to combustible tobacco use.9 While evidence about all these aspects of ENDS is accumulating, establishing their real place in smoking cessation is essential to outline the public health context of considering them as potential harm-reduced products. There are, however, other reasons for ENDS use such as for relaxation or recreation (ie, the same reason people smoke), with the possibility that adverse health effects may be less than conventional smoking.

There are many types of ENDS. The cigalikes are the first generation of ENDS that provide an appearance of tobacco cigarettes; they are not rechargeable. The second generation of ENDS looks like a pen, allows the user to mix flavours and may contain a prefilled or a refillable cartridge. The third generation of ENDS includes variable wattage devices and are used only with refillable tank systems. The fourth generation contains a large, refillable cartridge and has a tank-style design.

A previous Cochrane systematic review8 summarised results from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies. The authors included two RCTs and 11 cohort studies, and concluded that there was evidence to support the potential benefit of ENDS in increasing tobacco smoking cessation.8 The certainty of evidence supporting this conclusion was, however, deemed low, primarily due to the small number of trials resulting in wide CIs around effect estimates.8 Another systematic review10 including a total of six studies (RCTs, cohort and cross-sectional studies) involving 7551 participants concluded that ENDS is associated with smoking cessation and reduction; however, the included studies were heterogeneous, due to different study designs and gender variation. One other review11 comparing e-cigarettes with other nicotine replacement therapies or placebo included five studies (RCTs and controlled before–after studies) and concluded that participants using nicotine e-cigarettes were more likely to stop smoking, but noted no statistically significant differences.11 In a more recent systematic review, Kalkhoran and Glantz9 included 20 studies (15 cohort studies, 3 cross-sectional studies and 2 clinical trials), and found 28% lower odds rates of quitting cigarettes in those who used e-cigarettes compared with those who did not use e-cigarettes; however, the methodological aspects of the observational studies were rated as unclear or high on outcome assessors, and a RCT was rated as high risk of performance and attrition bias.

Previous reviews were, however, limited in that they did not include all studies in this rapidly evolving field, and all but one did not use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to rating quality of evidence. We therefore conducted an updated systematic review of RCTs and cohort studies that assessed the impact of ENDS and/or ENNDS versus no smoking cessation aid or alternative smoking cessation aids on long-term tobacco use, among cigarette smokers, regardless of whether the users were using them as part of a quit attempt.

Methods

We adhered to methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Intervention Reviews.12 Our reporting adheres to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA)13 and meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) statements.14 This work was commissioned by the WHO.

Eligibility criteria

Study designs: RCTs and prospective cohort studies.

Participants: cigarette smokers, regardless of whether the users were using them as part of a quit attempt.

Interventions: ENDS or ENNDS.

- Comparators:

- no smoking cessation aid;

- alternative non-electronic smoking cessation aid, including NRT, behavioural and/or pharmacological cessation aids (eg, bupropion and varenicline) and

- alternative electronic smoking cessation aid (ENDS or ENNDS).

- Outcomes:

- tobacco smoking cessation, with preference to biochemically validated outcomes (eg, carbon monoxide (CO)) measured at 6 months or longer follow-up;

- reduction in cigarette use of at least 50% and

- serious (eg, pneumonia, myocardial infarction) and non-serious (eg, nausea, vomiting) adverse events measured at 1 week or longer follow-up.

Data source and searches

A previous Cochrane review with similar eligibility criteria ran a comprehensive search strategy up to July 2014.8 Using medical subject headings (MeSH) based on the terms ‘electronic nicotine,’ ‘smoking-cessation,’ ‘tobacco-use-disorder,’ ‘tobacco-smoking’ and ‘quit’, we replicated the search strategy of that review8 in Medline, EMBASE, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ISI Web of Science and the trial registry (clinicaltrials.gov). The appendix table 1 shows the search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE. This strategy was adapted for the other databases and run from 1 April 2014 to 29 December 2015. We did not impose any language restrictions.

bmjopen-2016-012680supp_table-1.pdf (10KB, pdf)

In addition, we established a literature surveillance strategy based on the weekly search alerts by Centers for Disease Control and prevention (CDC)'s Smoking and Health Resource Library of published articles (http://nccd.cdc.gov/shrl/NewCitationsSearch.aspx) as well as the Gene Borio's daily news items (http://www.tobacco.org). The surveillance strategy started from the time of running the comprehensive literature search up to the time of the submission of this manuscript.

Selection of studies

Three pairs of reviewers underwent calibration exercises and used standardised pilot tested screening forms. They worked in teams of two and independently screened all titles and abstracts identified by the literature search, obtained full-text articles of all potentially eligible studies and evaluated them for eligibility. Reviewers resolved disagreement by discussion or, if necessary, with third party adjudication. We also considered studies reported only as conference abstracts. For each study, we cite all articles that used data from that study.

Data extraction

Reviewers underwent calibration exercises, and worked in pairs to independently extract data from included studies. They resolved disagreement by discussion or, if necessary, with third party adjudication. They abstracted the following data using a pretested data extraction form: study design; participants; interventions; comparators; outcome assessed and relevant statistical data. When available, we prioritised CO measurements as evidence of quitting. When CO measurement was unavailable, we used self-report measures of quitting.

Risk of bias assessment

Reviewers, working in pairs, independently assessed the risk of bias of included RCTs using a modified version of the Cochrane Collaboration's instrument15 (http:/distillercer.com/resources/).16 That version includes nine domains: adequacy of sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding of participants and caregivers, blinding of data collectors, blinding for outcome assessment, blinding of data analysts, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and the presence of other potential sources of bias not accounted for in the previously cited domains.16

For cohort studies, reviewers independently assessed risk of bias with a modified version of the Ottawa–Newcastle instrument17 that includes confidence in assessment of exposure and outcome, adjusted analysis for differences between groups in prognostic characteristics and missing data.17 For incomplete outcome data in individual studies (RCTs and prospective cohort studies), we stipulated as low risk of bias for loss to follow-up of <10% and a difference of <5% in missing data between intervention/exposure and control groups.

When information regarding risk of bias or other aspects of methods or results was unavailable, we attempted to contact study authors for additional information.

Certainty of evidence

We summarised the evidence and assessed its certainty separately for bodies of evidence from RCTs and cohort studies. We used the GRADE methodology to rate certainty of the evidence for each outcome as high, moderate, low or very low.18 In the GRADE approach, RCTs begin as high certainty and cohort studies as low certainty. Detailed GRADE guidance was used to assess overall risk of bias,19 imprecision,20 inconsistency,21 indirectness22 and publication bias23 and to summarise results in an evidence profile. We planned to assess publication bias through visual inspection of funnel plots for each outcome in which we identified 10 or more eligible studies; however, we were not able to because there were an insufficient number of studies to allow for this assessment. Cohort studies can be rated up for a large effect size, evidence of dose–response gradient or if all plausible confounding would reduce an apparent effect.24

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

We analysed all outcomes as dichotomous variables. In three-arm studies, we combined results from arms judged to be sufficiently similar (eg, Caponnetto 2013,25 two arms with similar ENDS regimens: 7.2 mg ENDS and 7.2 mg ENDS plus 5.4 mg ENDS). When studies reported results for daily or intensive use of ENDS separately from non-daily or less intensive use, we included only the daily/intensive use in the primary pooled analysis (eg, Brose 2015,26–28 we excluded patients with non-daily users; and Biener and Hargraves,29 we excluded patients with intermittent defined use). We conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we included all ENDS users, daily/intensive and intermittent/less intensive use. For this analysis, when necessary, we assumed a correlation of 0.5 between the effects in the daily/intensive and intermittent/less intensive groups.

We synthesised the evidence separately for bodies of evidence from RCTs and cohort studies. For RCTs, we calculated pooled Mantel-Haenszel risk ratios (RRs) and associated 95% CIs using random effects models. For observational studies, we pooled adjusted ORs using random effects models.

After calculating pooled relative effects, we also calculated absolute effects and 95% CI. For each outcome, we multiplied the pooled RR and its 95% CI by the median probability of that outcome. We obtained the median probability from the control groups of the available randomised trials. We planned to perform separate analyses for comparisons with interventions consisting of ENDS and/or ENNDS and each type of control interventions with known different effects (no smoking cessation aid; alternative non-electronic smoking cessation aid including NRT and alternative electronic smoking cessation aid (ENDS or ENNDS)). For meta-analyses, we used 6 months data or the nearest follow-up to 6 months available.

For dealing with missing data, we used complete case as our primary analysis; that is, we excluded participants with missing data. If results of the primary analysis achieved or approached statistical significance, we conducted sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of those results. Specifically, we conducted a plausible worst-case sensitivity analysis in which all participants with missing data from the arm of the study with the lower quit rates were assumed to have three times the quit rate as those with complete data, and those with missing data from the other arm were assumed to have the same quit rate as participants with complete data.30 31

We assessed variability in results across studies by using the I2 statistic and the p-value for the χ2 test of heterogeneity provided by Review Manager. We used Review Manager (RevMan) (V.5.3; Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane) for all analyses.32

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 presents the process of identifying eligible studies, including publications in the last systematic review,8 citations identified through search in electronic databases and studies identified through contact with experts in the field. Based on title and abstract screening, we assessed 69 full texts of which we included 19 publications describing three RCTs involving 1007 participants25 33–39 and nine cohort studies with a total of 13 115 participants.26–29 40–46 The interobserver agreement for the full-text screening was substantial (kappa 0.73).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of included studies. *McRobbie, 2014.8 **Further two publications from one RCT included by the Cochrane review were identified only in our search strategy. ***Further one publication from one cohort study identified by our search strategy was identified throughout the expert search.

We contacted the authors of the 12 included studies, 9 of whom26–29 33 41 43 44 46 supplied us with all requested data; authors of further 3 studies25 42 46 did not supply the requested information (see online supplementary appendix table S2).

bmjopen-2016-012680supp_table-2.pdf (181.7KB, pdf)

Study characteristics

Table 1 describes study characteristics related to design of study, setting, number of participants, mean age, gender, inclusion and exclusion criteria and follow-up.

Table 1.

Study characteristics related to design of study, setting, number of participants, mean age, gender, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and follow-up.

| Author, year | Design of study | Location | No.* participants | Mean age | No. male (%) | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials | ||||||||

| Adriaens, 201430 | Parallel RCT |

Leuven, Belgium | 50 | ENDS1: 44.7 ENDS2: 46.0 ENDS and e-liquid**: 40.3 |

21 (43.7) | Being a smoker for at least three years; smoking a minimum of 10 factory-made cigarettes per day and not having the intention to quit smoking in the near future, but willing to try out a less unhealthy alternative | Self-reported diabetes; severe allergies; asthma or other respiratory diseases; psychiatric problems; dependence on chemicals other than nicotine, pregnancy; breast feeding; high blood pressure; cardiovascular disease; currently using any kind of smoking cessation therapy and prior use of an e-cigarette | 8 |

| Bullen, 201331–36 | Parallel RCT |

New Zealand | 657 | 16 mg ENDS: 43.6 21 mg patches NRT: 40.4 ENNDS: 43.2 |

252 (38.3) | Aged 18 years or older; had smoked ten or more cigarettes per day for the past year; wanted to stop smoking; and could provide consent | Pregnant and breastfeeding women; people using cessation drugs or in an existing cessation programme; those reporting heart attack, stroke, or severe angina in the previous two weeks; and those with poorly controlled medical disorders, allergies, or other chemical dependence | 6 |

| Caponnetto, 201325 | Parallel RCT |

Catania, Italy | 300 | 7.2 mg ENDS: 45.9 7.2 mg ENDS+5.4 mg ENDS: 43.9 ENNDS: 42.2 |

190 (63.3) | Smoke 10 factory made cigarettes per day (cig/day) for at least the past five years; age 18–70 years; in good general health; not currently attempting to quit smoking or wishing to do so in the next 30 days; committed to follow the trial procedures | Symptomatic cardiovascular disease; symptomatic respiratory disease; regular psychotropic medication use; current or past history of alcohol abuse; use of smokeless tobacco or nicotine replacement therapy, and pregnancy or breastfeeding | 12 |

| Cohort studies | ||||||||

| Al-Delaimy, 201537 | Cohort | California, US | 628 | Not reported | 478 (47.8) | Residents of California; aged 18 to 59 years who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and are current smokers | Participants who reported that they “might use e-cig” or changed their reporting at follow-up, as they did not represent a definitive group of users or never-users e-cig and might overlap with both | 12 |

| Biener, 201538 | Cohort | Dallas and Indianapolis areas, US | 1374 | Not reported | 383 (55.2) | Adults smokers residing in the Dallas and Indianapolis metropolitan areas, who had been interviewed by telephone and gave permission to be re-contacted | Anyone over 65 years old | 36 |

| Brose, 201540–42 | Cohort | Web-based, United Kingdom | 3891*** | ENDS Among daily users: 45.7 Among non-daily users: 45.2 No ENDSα: 45.7 |

2,015 (49.6) | Members were invited by e-mail to participate in an online study about smoking and who answered a screening question about their past-year smoking status | Baseline pipe or cigar smokers, and follow-up pipe or cigar smokers or unsure about smoking status | 12 |

| Hajek 201546 | Cohort | Europe | 100 | ENDS: 41.8 No ENDS: 39 |

57 (57) | All smokers joining the UK Stop Smoking Services in addition to the standard treatment (weekly support and stop smoking medications including NRT and varenicline). | No exclusion criteria | 4 weeksβ |

| Harrington 201546 | Cohort | US | 979 | 46.0**** | 525 (53.6) | Hospitalized cigarette smokers at a tertiary care medical center; self-identified smoker who smoked at least one puff in previous 30 days; English speaking and reading; over age 18 and; cognitively and physically able to participate in study | Pregnant | 6 |

| Manzoli, 201543 | Cohort | Abruzzo and Lazio region, Italy | 1355 | ENDS only: 45.2 Tobacco cigarettes only: 44.2 Dual smoking: 44.3 |

757 (55.9) | Aged between 30 and 75 years; smoker of e-cig (inhaling at least 50 puffs per week) containing nicotine since six or more months (E-cig only group); smoker of at least one traditional cigarette per day since six or more months (traditional cigarettes only group); smoker of both electronic and traditional cigarettes (at least one per day) since six or more months (mixed Group) | Illicit drug use, breastfeeding or pregnancy, major depression or other psychiatric conditions, severe allergies, active antihypertensive medication, angina pectoris, past episodes of major cardiovascular diseases (myocardial infarction, stroke/TIA, congestive heart failure, COPD, cancer of the lung, esophagus, larynx, oral cavity, bladder, pancreas, kidney, stomach, cervix, and myeloid leukemia | 12 |

| Borderud, 201439 | Cohort | New York, US | 1074 | ENDS use+ behavioral and pharmacological treatment: 56.3 No ENDS+behavioral and pharmacological treatment: 55.6 |

467 (43.5) | Patients with cancer referred to a tobacco cessation program who provided data on their recent (past 30 days) e-cig use | No exclusion criteria | 6 to 12 |

| Prochaska 201444 | Cohort | US | 956 | 39.0**** | 478 (50.0) |

Adult daily smokers (at least 5 cigarettes/day with serious mental illness at four psychiatric hospitals in the San Francisco Bay Area | Non-English speaking; medical contraindications to NRT use (pregnancy, recent myocardial infarction); and lack of capacity to consent as determined by a 3-item screener of study purpose, risks, and benefits | 18 |

| Vickerman 201345 | Cohort | US | 2,758€ | Used ENDS one month or more: 48.1 Used ENDS less than one month: 45.3 No ENDS: 49.6 |

913 (36.9) | Participants from six state quitlines who registered for tobacco cessation services. Adult tobacco users, consented to evaluation follow-up, spoke English, provided a valid phone number, and completed at least one intervention call | No exclusion criteria | 7 |

no.: number; e-cig: e-cigarettes; ENDS: Electronic nicotine delivery system; ENNDS: electronic non-nicotine delivery systems; RCT: randomized controlled trial; US: United States; ENDS1 and ENDS2: the e-cig groups received the e-cig and four bottles of e-liquid at session 1 (group e-cig1 received the “Joyetech eGo-C” and group e-cig2 received the “Kanger T2-CC”); at session 2, participants' empty bottles were replenished up to again four bottles and at session 3, they were allowed to keep the remaining bottles.

*Randomized or at baseline

**For the first two months control group consisted of no e-cigarettes use. After that period, the participants of control group received the e-cig and e-liquid. ENDS1=“Joyetech eGo-C” e-cig and ENDS2=“Kanger T2-CC” e-cig.

***The 4117 were reported in a publication that focused on baseline characteristics, not on the use of e-cigarettes and changes in smoking behavior, so the remaining 53 participants are irrelevant to this review.

****Mean age of the overall population.

αThe comparator comprises of current non-users of e-cig, which included never-users and those who had previously tried but were not using at the moment.

βHajek 2015 was the only study that entered in the review due to meet the criteria for adverse events.

€But only 2,476 asnwered the question “Have you ever used e-cigarettes, electronic, or vapor cigarettes?”

Five studies25–28 33 42 46 were conducted largely in Europe, six in the USA,29 40 41 43–45 and one in New Zealand.34–39 Randomised trials sample size ranged from 5033 to 657,34–39 and observational studies from 10046 to 3891.26–28 Typical participants were women in their 40 s and 50 s. Studies followed participants from 4 weeks46 to 36 months.29

Table 2 describes study characteristics related to population, intervention or exposure groups, comparator and assessed outcomes.

Table 2.

Study characteristics related to population, intervention or exposure groups, comparator, and assessed outcomes.

| Author, year | Population | No.* of participants intend to quit smoking | No.* of participants in intervention or exposure groups and comparator | Description of intervention or exposure groups | Description of comparators | Measured outcomes | Definition of quitters or abstinence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials | |||||||

| Adriaens, 201433 | Participants unwilling to quit smoking (participants from the control group kept on smoking regular tobacco cigarettes during the first eight weeks of the study) | Yes 0 No 50 |

ENDS 1: 16 ENDS 2: 17 Control/ENDS: 17 |

ENDS (“Joyetech eGo-C”) ENDS E-cigarettes (“Kanger T2-CC”) |

ENDS and e-liquid** | Quitting, defined as eCO of 5 ppm or smaller; questionnaire self-report of reduction in cigarettes of>50% or complete quitting | No more cigarette smoking |

| Bullen, 201334–39 | Had smoked ten or more cigarettes per day for the past year, interested in quitting | Yes 657 No 0 |

ENDS: 289 NRT: 295 ENNDS: 73 |

16 mg nicotine ENDS | 21 mg patches NRT ENNDS |

Continuous smoking abstinence, biochemically verified (eCO measurement <10 ppm); seven day point prevalence abstinence; reduction; and adverse events | Abstinence allowing ≤5 cigarettes in total, and proportion reporting no smoking of tobacco cigarettes, not a puff, in the past 7 days |

| Caponnetto, 201325 | Smokers not intending to quit | Yes 0 No 300 |

ENDS 1: 100 ENDS 2: 100 ENNDS: 100 |

7.2 mg nicotine ENDS 7.2 mg nicotine ENDS+5.4 mg nicotine ENDS |

ENNDS | Self-report of reduction in cigarettes of>50%; abstinence from smoking, defined as complete self-reported abstinence from tobacco smoking - not even a puff, biochemically verified (eCO measurement ≤7 ppm); and adverse events | Complete self-reported abstinence from tobacco smoking - not even a puff |

| Cohort studies | |||||||

| Al-Delaimy, 201540 | Current smokers; regardless of whether the users were using ENDS as part of a quit attempt | Yes 415 No 542 |

ENDS: 236Ψ No ENDS: 392Ψ |

ENDS | No ENDS | Quit attempts; 20% reduction in monthly no. of cigarettes; and current abstinence from cigarette use | Duration of abstinence of one month or longer to be currently abstinent |

| Biener, 201529 | All respondents had reported being cigarette smokers at baseline; regardless of whether the users were using ENDS as part of a quit attempt | Yes 364β No 331€ |

1374$ | ENDS£ intermittent use ENDS£ intensive use |

No ENDS (used once or twice ENDS) | Smoking cessation; and reduction in motivation to quit smoking among those who had not quit, not otherwise specified | Smoking cessation was defined as abstinence from cigarettes for at least one month |

| Brose, 201526–28 | Current smokers; regardless of whether the users were using ENDS as part of a quit attempt | Not reported | ENDS: 1507 No ENDS: 2610 |

ENDS daily ENDS non-daily |

No ENDS€ | Quit attemptsφ; cessationϖ; and substantial reduction defined as a reduction by at least 50% from baseline CPD to follow-up CPD | Change from being a smoker at baseline to being an ex-smoker at follow-up was coded as cessation |

| Hajek, 201546 | 69% (n=69) accepted e-cigs as part of their smoking cessation treatment | Not reported | ENDS: 69 No ENDS: 31 |

ENDS was offered to all smokers in addition to the standard treatment (weekly support and stop smoking medications including NRT and varenicline) | No ENDS | Self-reported abstinence was biochemically validated by exhaled CO levels in end-expired breath using a cut-off point on 9ppm, adverse events | Self-reported abstinence from cigarettes at 4 weeks |

| Harrington, 201545 | Hospitalized cigarette smokers. All were cigarette smokers initially; regardless of whether the users were using ENDS as part of a quit attempt | Yes: 220*** No: not reported |

ENDS: 171 No ENDS: 759 |

ENDS | No ENDS | Quitting smoking based on 30-day point prevalence at 6 months | Only self-reported quitting smoking |

| Manzoli, 201542 | Smokers of ≥1 tobacco cigarette/day (tobacco smokers), users of any type of e-cig, inhaling ≥50 puffs weekly (e-smokers), or smokers of both tobacco and e-cig (dual smokers) | Not reported | ENDS: 343 Tobacco and ENDS: 319 Tobacco only: 693 |

ENDS Tobacco and ENDS |

Tobacco cigarettes only | Abstinence, proportion of quitters, biochemically verified (eCO measurement>7ppm), reduce tobacco smoking, and serious adverse events | Percentage of subjects reporting sustained (30 days) smoking abstinence from tobacco smoking |

| Borderud, 201441 | Patients who presented for cancer treatment and identified as current smokers (any tobacco use within the past 30 days); regardless of whether the users were using ENDS as part of a quit attempt | Yes 633¥ No 42¥ |

ENDS: 285 No ENDS: 789 |

ENDS£+Evidence-based behavioral and pharmacologic treatment | No ENDS+Evidence-based behavioral and pharmacologic treatment | Smoking cessation by self-report | Patients were asked if they had smoked even a puff of a (traditional) cigarette within the last 7 days |

| Prochaska, 201443 | Adult daily smokers with serious mental illness; regardless of whether the users were using ENDS as part of a quit attempt | At baseline, 24% intended to quit smoking in the next month | ENDS: 101 No ENDS: 855 |

ENDS | No ENDS | Smoking cessation by self-report and, biochemically verified (CO and cotinine) | Past 7 day tobacco abstinence |

| Vickerman, 201344 | Adult tobacco current or past users; regardless of whether the users were using ENDS as part of a quit attempt | Not reported | ENDS: 765 No ENDS: 1,711 |

ENDS used for 1 month or more ENDS used for less than 1 month |

No ENDS (never tried) | Tobacco abstinence | Self-reported 30-day tobacco abstinence at 7 month follow-up |

no.: number; C: comparator group; CPD: cigarettes smoked per day; e-cig: e-cigarettes; ENDS: Electronic nicotine delivery system; ENNDS: electronic non-nicotine delivery systems; eCO: exhaled breath carbon monoxide; NE: non-exposure group; NRT: Nicotine replacement therapy.

*Numbers randomized or at baseline.

**For the first two months control group consisted of no e-cigarettes use. After that period, the participants of control group received the e-cig and e-liquid. ENDS1=“Joyetech eGo-C” e-cig and ENDS2=“Kanger T2-CC” e-cig.

***Only among those who reported any previous use of e-cigs.

αInformation retrieved through contact with author.

€The comparator comprises of current non-users of e-cig, which included never-users and those who had previously tried but were not using at the moment.

ΨParticipants who will never use e-cig plus those who never heard of e-cig=392; participants who have used e-cig=236 (numbers taken from the California Smokers Cohort, a longitudinal survey).

βIntentions to quit smoking, those who tried e-cigarettes only once or twice are grouped with never users (“non-users/triers”).

€Intermittent use (i.e., used regularly, but not daily for more than 1 month) plus intensive use (i.e., used e-cig daily for at least 1 month).

$No. of the whole sample including comparator.

£All ENDS.

¥The other participants either quit more than a month ago but less than six months, less than a month ago, or more than six months ago.

φSmokers and recent ex-smokers were asked about the number of attempts to stop they had made in the previous year. Those reporting at least one attempt and 37 respondents who did not report an attempt but had stopped smoking be- tween baseline and follow-up were coded as having made an attempt.

ϖChange from being a smoker at baseline to being an ex-smoker at follow-up was coded as cessation.

Of the three RCTs, one compared ENDS with NRT and ENNDS,34–39 another compared different concentrations of ENDS with ENNDS25 and the third compared different types of ENDS.33 Only the Borderud study41 included participants who were also currently receiving other behavioural and pharmacologic treatment. The participants from Vickerman 201344 study were all enrolled in a state quitline programme that provided behavioural treatment and in some cases NRT. All nine cohort studies26–29 34–46 compared ENDS with no use of ENDS26–29 40 41 or tobacco cigarettes only;42 in one,41 exposure and non-exposure groups received behavioural and other pharmacologic treatment.

Table 3 describes the mean number of conventional cigarettes used per day at baseline and the end of study.

Table 3.

Mean number of conventional cigarettes used per day at baseline and the end of study*

| Author, year | Groups | Mean no. of conventional cigarettes used per day at baseline | Mean no. of conventional cigarettes used per day at the end of study | Biochemically quitters (no. of events per no. of total participants) | Self-reported quitters (no. of events per no. of total participants) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adriaens, 201433 | ENDS 1 | 20.1 | 7.0† | 3/13 | 4/13 |

| ENDS 2 | 20.6 | 8.1† | 3/12 | 3/12 | |

| Control/ENDS‡,§ | 16.7 | 7.7† | 4/13 | 4/13 | |

| Bullen, 201334–39 | ENDS | 18.4 | 0.7¶ | 21/241 | Not available |

| ENNDS | 17.7 | 0.7 | 3/57 | Not available | |

| NRT | 17.6 | 0.8¶ | 17/215 | Not available | |

| Caponnetto, 201325 | 7.2 mg ENDS | 19.0 (14.0–25.0)** | 12 (5.8–20)**,†† | Combined ENDS groups: 22/128 | Not available |

| 7.2 mg ENDS plus 5.4 mg ENDS | 21.0 (15.0–26.0)** | 14 (6–20)**,†† | Not available | ||

| ENNDS | 22.0 (15.0–27.0)** | 12 (9–20)**,†† | 4/55 | Not available | |

| Al-Delaimy, 201540 | ENDS | 14.1‡‡ | 13.8§§ | Not available | 12/179 |

| ENNDS | Not available | 32/145 | |||

| Biener, 201529 | ENDS intermittent use | 16.7¶¶ | Not available | Not available | Combined ENDS groups: 42/331 |

| ENDS intensive use | 17.1¶¶ | Not available | Not available | ||

| No ENDS | 15.4¶¶ | Not available | Not available | 82/364 | |

| Brose, 201526–28 | ENDS daily users | 14.3 | 13.0*** | Not available | 7/86 |

| ENDS non-daily users | 13.5 | 13.9*** | Not available | 25/263 | |

| No ENDS††† | 13.3 | 13.5 | Not available | 168/1307 | |

| Hajek, 201546 | ENDS | Not available | Not available | Not applicable‡‡‡ | Not applicable‡‡‡ |

| No ENDS | Not available | Not available | Not applicable‡‡‡ | Not applicable‡‡‡ | |

| Harrington, 201545 | ENDS | 14.1§§§ | 10.3§§§ | Not available | 21/171 |

| No ENDS | 11.9§§§ | 9.8§§§ | Not available | 62/464 | |

| Manzoli, 201542 | ENDS only | Not available | 12 | Not available | Not available |

| Tobacco cigarettes only | 14.1 | 12.8 | 101/491 | Not available | |

| Dual smoking | 14.9 | 9.3 | 51/232 | Not available | |

| Borderud, 201441 | ENDS | 13.7 | 12.3 | Not available | 25/58 |

| No ENDS | 12.4 | 10.1 | Not available | 158/356 | |

| Prochaska, 201443 | ENDS | 17.0 | 10.0 | 21/101 | Not available |

| No ENDS | 17.0 | 10.1 | 162/855 | Not available | |

| Vickerman, 201344 | ENDS used for 1 month or more | 19.4 | 13.5 | Not available | 59/273 |

| ENDS used for less than 1 month | 18.9 | 14.0 | Not available | 73/439 | |

| No ENDS (never tried) | 18.1 | 12.9 | Not available | 535/1711 |

*When authors provided data for different time points, we presented the data for the longest follow-up.

†8 months from start of intervention.

‡Control group consisted of received the e-cig and e-liquid (six bottles) for 2 months at the end of session 3 (eight of the 16 participants of the control group received the ‘Joyetech eGo-C’ and the remaining eight participants received the ‘Kanger T2-CC’).

§For the first 2 months control group consisted of no e-cigarettes use. After that period, the participants of control group received the e-cig and e-liquid. ENDS1=’Joyetech eGo-C’ e-cig and ENDS2=’Kanger T2-CC’ e-cig.

¶For those reporting smoking at least one cigarette in past 7 days.

**Data shown as median and interquartile.

††At 6 months after the last laboratory session.

‡‡Of the 1000 subjects, 993 responded to the question “How many conventional cigarettes smoked per day during the past 30 days”.

§§Of the 1000 subjects, 881 responded to the question “How many cigarettes smoked per day during the past 30 days.”

¶¶Number of conventional cigarettes used in the prior month at baseline.

***No. of cigarette per week divided by 7 days.

†††The comparator comprises of current non-users of e-cig which included never-users and those who had previously tried but were not using at the moment.

‡‡‡Not applicable because they followed participants only for 4 weeks, but the study reported adverse events at 1 week or longer.

§§§Data for baseline current e-cig users.

e-cig, eletronic cigarettes; ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery system; ENDS1 and ENDS 2, the e-cig groups received the e-cig and four bottles of e-liquid at session 1 (group e-cig1 received the ‘Joyetech eGo-C’ and group e-cig2 received the ‘Kanger T2-CC’); at session 2; ENNDS, electronic non-nicotine delivery systems; No., number; RYO, roll your own (loose tobacco) cigarettes.

The mean number at baseline ranged from 11.9 in the no ENDS group45 to 20.6 in the ENDS group.33 In only two studies26–28 45 the mean number of conventional cigarettes used per day presented a reduction from the baseline to the end of study in the ENDS group compared with the no ENDS groups, mainly in the daily users.26–28 No included study addressed users of combustible tobacco products other than cigarettes.

Online supplementary appendix table S3 presents the types of e-cigarettes used in the included studies. The three RCTs25 33 36–39 evaluated only ENDS-type cigalikes. A total of 23.7% of the participants from Brose 201526–28 study used tank and in the Hajek 201546 study participants used either cigalike or tank. The remaining studies did not report the type of ENDS used.

bmjopen-2016-012680supp_table-3.pdf (65.4KB, pdf)

Risk of bias

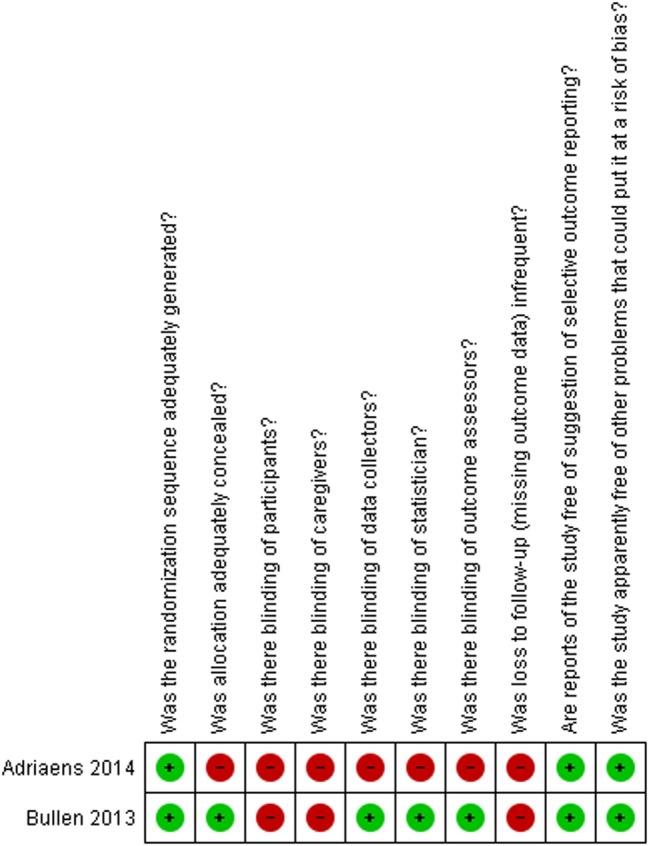

Figures 2 and 3, and table 4, describe the risk of bias assessment for the RCTs.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias for RCTs comparing ENDS versus ENNDS.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias for RCTs comparing ENDS versus other strategies.

Table 4.

Risk of bias assessment for the randomised controlled trials

| Author, year | Was the randomisation sequence adequately generated? | Was allocation adequately concealed? | Was there blinding of participants? | Was there blinding of caregivers? | Was there blinding of data collectors? | Was there blinding of statistician? | Was there blinding of outcome assessors? | Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?* | Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? | Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised controlled trials assessing ENDS vs ENNDS | ||||||||||

| Bullen, 201334–39 | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely no | Definitely yes | Definitely yes |

| Caponnetto, 201325 | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely no | Definitely yes | Definitely yes |

| Randomised controlled trials assessing ENDS vs other quitting mechanisms | ||||||||||

| Adriaens, 201433 | Definitely yes | Probably no | Probably no | Probably no | Probably no | Probably no | Probably no | Definitely no | Probably yes | Probably yes |

| Bullen, 201334–39 | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Definitely no | Definitely no | Probably yes | Probably yes | Definitely yes | Definitely no | Definitely yes | Definitely yes |

All answers as: definitely yes (low risk of bias), probably yes, probably no, definitely no (high risk of bias).

*Defined as less than 10% loss to outcome data or difference between groups less than 5% and those excluded are not likely to have made a material difference in the effect observed.

ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery systems; ENNDS, electronic non-nicotine delivery systems.

The major issue regarding risk of bias in the RCTs of ENDS versus ENNDS was the extent of missing outcome data.25 34–39 RCTs comparing ENDS with other nicotine replacement therapies had additional problems of concealment of randomisation33 and blinding.33–39

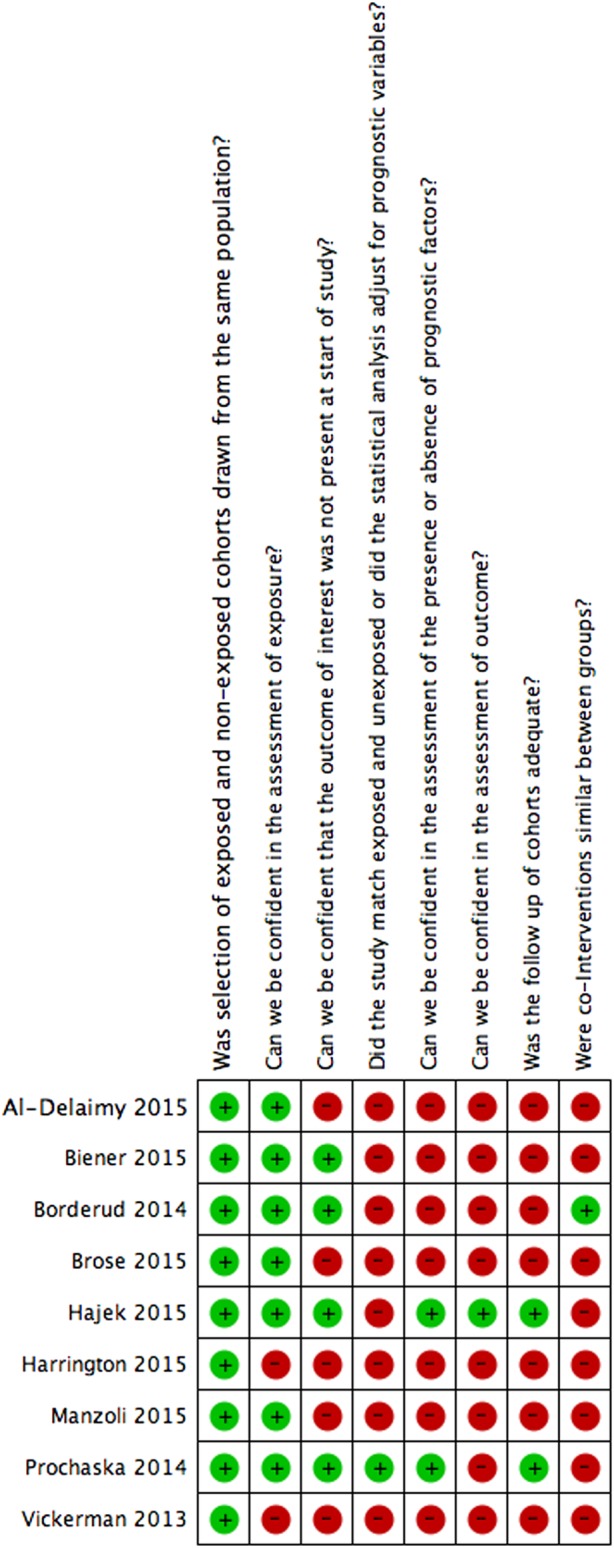

Figure 4 and table 5 describe the risk of bias assessment of the cohort studies.

Figure 4.

Risk of bias for cohort studies.

Table 5.

Risk of bias assessment of the cohort studies

|

Author, year |

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?* |

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?† |

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?‡ |

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these prognostic variables?§ |

Can we be confident in the assessment of the presence or absence of prognostic factors?¶ |

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?** |

Was the follow-up of cohorts adequate?†† |

Were cointerventions similar between groups?‡‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Delaimy 201540 | Definitely yes | Probably yes | Definitely yes | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Probably no |

| Biener 201529 | Definitely yes | Probably yes | Definitely yes | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Probably no |

| Brose 201526–28 | Definitely yes | Probably yes | Probably no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Probably no |

| Hajek 201546 | Probably yes | Probably yes | Probably yes | Definitely no | Probably yes | Probably yes | Probably yes | Probably no |

| Harrington 201545 | Definitely yes | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no |

| Manzoli 201542 | Definitely yes | Probably yes | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Probably no | Definitely no | Probably no |

| Borderud 201441 | Definitely yes | Probably yes | Definitely yes | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely yes |

| Prochaska 201443 | Definitely yes | Probably yes | Definitely yes | Definitely yes | Probably yes | Definitely no | Definitely yes | Probably No |

| Vickerman 201344 | Probably yes | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no | Definitely no |

All answers as: definitely yes (low risk of bias), probably yes, probably no, definitely no (high risk of bias).

*Examples of low risk of bias: Exposed and unexposed drawn from same administrative data base of patients presenting at same points of care over the same time frame.

†This means that investigators accurately assess the use of ENDS at baseline.

‡This means that smoking cessation was not present at the start of the study.

§Examples of low risk of bias: comprehensive matching or adjustment for all plausible prognostic variables.

¶Examples of low risk of bias: Interview of all participants; self-completed survey from all participants; review of charts with reproducibility demonstrated; from data base with documentation of accuracy of abstraction of prognostic data.

**Outcome self-reported was considered as definitely no for adequate assessment. Smoking abstinence, biochemically verified was considered as definitely yes for adequate assessment.

††Defined as less than 10% loss to outcome data or subjects lost to follow-up unlikely to introduce bias.

‡‡Examples of low risk of bias: Most or all relevant cointerventions that might influence the outcome of interest are documented to be similar in the exposed and unexposed.

Seven26–29 40–42 44 45 of nine cohort studies were rated as high risk of bias for limitations in matching exposed and unexposed groups or adjusting analysis for prognosis variables; confidence in the assessment of the presence or absence of prognostic factors; confidence in the assessment of outcome and similarity of cointerventions between groups; all studies suffered from high risk of bias for missing outcome data.

Outcomes

The mean number of conventional cigarettes/tobacco products used per day at the end of the studies ranged from 0.734–39 in ENDS and ENNDS groups to 13.926–28 among non-daily users of ENDS (table 3). The three RCTs25 33–39 and one cohort study42 biochemically confirmed nicotine abstinence while the others presented only self-reported data26–29 40 41 43–45 (table 3).

Tobacco cessation smoking

Synthesised results from RCTs

Results from two RCTs25 34–39 suggest a possible increase in smoking cessation with ENDS in comparison with ENNDS (RR 2.03, 95% CI 0.94 to 4.38; p=0.07; I2=0%, risk difference (RD) 64/1000 over 6 to 12 months, low-quality evidence) (figure 5, table 6).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of RCTs on cessation smoking comparing ENDS versus ENND.

Table 6.

GRADE evidence profile for RCTs: Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS) for reducing cigarette smoking.

| Quality assessment |

Summary of findings |

Certainty in estimates | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of participants (studies) Range follow-up time |

Study event rates |

Anticipated absolute effects over 6-12 months |

|||||||||

| Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | ENNDS* | ENDS | Relative risk (95% CI) |

ENNDS* | ENDS | OR Quality of evidence |

|

| Mortality | |||||||||||

| 481 (2) 6-12 mo |

No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Serious imprecision1 | Undetected | 7/ 112 | 43/ 369 | 2.03 (0.94-4.38) |

213 per 1000 | 219 more per 1000 (13 fewer to 720 more) |

⊕⊕OO LOW |

| Renal insufficiency | |||||||||||

| 481 (2) 6-12 mo |

Serious limitations1 | Serious limitations | No serious limitations | Serious imprecision2 | Undetected | 45/ 112 | 184/ 369 | 0.97 (0.57-1.66) |

213 per 1000 | 7 fewer per 1000 (92 fewer to 140 more) |

⊕⊕OO LOW |

*The estimated risk control was taken from the median estimated control risks of the cohort studies.

195% CI for absolute effects include clinically important benefit and no benefit.

A plausible worse case sensitivity analysis yielded results that were inconsistent with the primary complete case analysis and fail to show a difference in the effects of ENDS in comparison with ENNDS (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.87; p=0.54; I2=0%) (see online supplementary appendix figure 1). Certainty in evidence was rated down to low because of imprecision and risk of bias, due to missing outcome data in all studies and lack of blinding of participants,34–39 caregivers, data collectors, statistician and outcome assessors in the ENDS versus other NRT studies (figure 2, tables 4 and 6).

bmjopen-2016-012680supp_figures.pdf (117.1KB, pdf)

Adriaens 201433 also compared two types of ENDS and ENDS and e-liquid; results failed to show a difference between the ENDS groups with a very wide CI (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.28 to 4.76, p=0.84).

Bullen 201334–39 also compared ENDS and ENNDS with NRT; results failed to show a difference between these groups with a very wide CI (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.03, p=0.76) and (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.20 to 2.19, p=0.50), respectively.

Synthesised results from cohort studies

The adjusted OR from primary meta-analysis of eight cohort studies26–29 40–45 comparing ENDS with no ENDS without reported concomitant interventions failed to show a benefit in cessation smoking (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.00; p=0.051; I2=56%) (figure 6). A sensitivity analysis from the eight cohort studies26–29 40–45 using any rather than daily use of ENDS for Brose study,26–28 intensive (used e-cigarettes daily for at least 1 month) and intermittent use (used regularly, but not daily for more than 1 month) of ENDS for Biener study29 and any use versus never used for Vickerman study44 suggested a reduction in cessation smoking rates with ENDS (adjusted OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.91; p=0.01; I2=59%) (see online supplementary appendix figure 2).

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of cohort studies on cessation smoking with adjusted ORs.

Another sensitivity analysis from the same eight cohort studies26–29 40–45 examined whether low and high risk of bias limited to the one characteristic in which the studies differed substantially: confidence in whether the outcome was present at the beginning of the study. Although there were substantial differences in the point estimates in the low risk of bias group (adjusted OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.94; p=1.00; I2=67%) and the high risk of bias group (adjusted OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.77; p<0.001; I2=0%), the difference is easily explained by chance (interaction p-value was 0.19) (see online supplementary appendix figure 3).

A second sensitivity analysis from the same eight cohort studies26–29 40–45 examined whether low and high risk of bias limited to ‘two or fewer domains rated as low risk of bias’ versus ‘three or more domains rated as low risk of bias’ differed substantially. There were substantial differences in the point estimates between the ‘two or fewer domains rated as low risk of bias’ group (adjusted OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.75; p<0.001; I2=0%) and the ‘three or more domains rated as low risk of bias’ (adjusted OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.68 to 2.33; p=0.46; I2=51%), with an interaction p-value of 0.03 (see online supplementary appendix figure 4).

Certainty in evidence from the observational studies was rated down from low to very low because of risk of bias due to missing outcome data, imprecision in the assessment of prognostic factors and outcomes (figure 4, tables 5 and 7), as well as inconsistency in the results.

Table 7.

GRADE evidence profile for cohort studies: Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and no ENDS for reducing cigarette smoking

| Quality assessment |

Summary of findings |

Certainty in estimates | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study event rates | Relative risk (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects over 6–12 months | OR Quality of evidence |

||||||||

| No of participants (studies) Range follow-up time |

Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | ENNDS* | ENDS | ENNDS* | ENDS | ||

| Cessation/nicotine abstinence (Includes self-reported and biochemically validated by eCO) | |||||||||||

| 7826 (8) 6–36 mo |

Serious limitations† | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Serious imprecision‡ | Undetected | 1300/5693 | 336/2133 | 0.74 (0.55 to 1.00) | 213 per 1000 | 56 fewer per 1000 (96 fewer to 0 more) | ⊕OOO VERY LOW |

*The estimated risk control was taken from the median estimated control risks of the cohort studies.

†All studies were rated as high risk of bias for adjustment for prognosis variable; assessment of prognostic factors; assessment of outcomes; adequate follow-up of cohort; and similarity of cointerventions between groups.

‡95% CI for absolute effects include clinically important benefit and no benefit.

Borderud 201441 reported cessation smoking in 25 out of 58 patients with cancer using ENDS plus behavioural and pharmacologic treatment versus in 158 out of 356 patients with cancer who received only behavioural and pharmacologic treatment (adjusted OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.33).

Reduction in cigarette use of at least 50%

Synthesised results from RCTs

Two RCTs25 34–39 results failed to show a difference between ENDS-type cigalikes versus ENNDS group with regards to reduction in cigarettes but with a very wide CI (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.66; p=0.92; I2=61%) (see online supplementary appendix figure 5). Certainties in evidence were rated low because of imprecision and risk of bias25 34–36 38 39 (figure 2, tables 4 and 6).

Synthesised results from cohort studies

Two studies26–29 suggested increased reduction rates in those with greater versus lesser use of ENDS. Biener29 reported an adjusted OR for quitting of 6.07 (95% CI 1.11 to 33.2) in those with intensive use versus an OR of 0.31 (0.04, 2.80) in those with intermittent use. Brose26–28 reported a greater likelihood of substantial reduction (but not quitting) in those with daily use of ENDS (OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.14 to 5.45) but not those with intermittent use (OR 0.85 0.43 to 1.71).

Adverse effects

Synthesised results from RCTs

The Bullen 201334–37 39 study reported serious side effects in 27 out of 241 participants in the 16 mg ENDS group and 5 out of 57 for the ENNDS group followed at 6 months; results failed to show a difference between these groups with a very wide CI (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.48 to 3.57; p=0.59). Results suggested possible increase in side effects in the 21 mg nicotine patches group (14 of 215) in comparison with ENDS (OR 1.81, 95% CI 0.92 to 3.55; p=0.08). Serious side effects include death (n=1, in nicotine e-cigarettes group), life threatening illness (n=1, in nicotine e-cigarettes group), admission to hospital or prolongation of hospital stay (12% of all events in nicotine e-cigarettes group, 8% in patches group and 11% in placebo e-cigarettes group), persistent or significant disability or incapacity and other medically important events (6% of all events in nicotine e-cigarettes group, 4% in patches group and 3% placebo e-cigarettes group).

Adriaens 201433 study reported no serious adverse events in ENDS groups as well as in the e-liquid group at 8 months of follow-up; however at 1 week from start of intervention there were three cases of non-serious adverse events in the ENDS groups.

Caponnetto 201325 mentioned that no serious adverse events occurred during the study and authors found a significant reduction in frequency of reported symptoms compared with baseline.

Synthesised results from cohort studies

Manzoli42 reported no significant differences in self-reported serious side effects, but observed four cases of pneumonia, four COPD exacerbations, three myocardial infarctions and one angina as possibly related serious side effects: two among the ENDS users (both switched to tobacco smoking during follow-up); six among tobacco smokers (three quit all smoking) and four among tobacco and ENDS smokers.

Hajek 201546 reported one leak irritating a participant's mouth and some reports of irritation at the back of the throat and minor coughing. The remaining studies did not report adverse effects.

Discussion

Main findings

Based on pooled data from two randomised trials with 481 participants, we found evidence for a possible increase in tobacco smoking cessation with ENDS in comparison with ENNDS (figure 5). The evidence is, however, of low certainty: the 95% CI of the relative risk crossed 1.0 and a plausible worse case sensitivity analysis to assess the risks of bias associated with missing participant data yielded results that were inconsistent with the primary complete case analysis (see online supplementary appendix figure 1). Furthermore, in all these RCTs, the ENDS tested were of earlier generation; it is unknown whether providing later generation of e-cigarettes or a realistic scenario of allowing users to choose e-cigarettes based on self-preference would have greater benefit. There was no robust evidence of side effects associated with ENDS in the RCTs.

Cohort studies provide very low-certainty evidence suggesting a possible reduction in quit rates with use of ENDS compared with no use of ENDS (figure 6). These studies had a number of limitations: an unknown number of these participants were not using ENDS as a cessation device; some were not using ENDS during a quit attempt; many did not have immediate plans to quit smoking and some may have already failed attempts to stop smoking. In our risk of bias assessment, we judged that seven of nine studies did not have optimal adjustment for prognostic variables. Further, as any cohort study, the results are vulnerable to residual confounding. In particular, use of ENDS may reflect the degree of commitment to smoking cessation, and it may be the degree of commitment, rather than use of ENDS, that is responsible for the change in quit rates. For instance, the finding in two studies that daily use of ENDS, but not intermittent use, increased quit/reduction rates could be interpreted as evidence of the effectiveness of daily use. An alternative interpretation, however, is that those that used ENDS daily were more motivated to stop smoking, and the increased motivation, rather than daily use of ENDS, was responsible for their degree of success. It is worth to mention that motivation to quit smoking is a major determinant of success regardless of the aid used.

In terms of bias against ENDS, cohort studies sometimes enrol smokers already using ENDS and still smoking. Such individuals may already be failing in their attempts to stop smoking. If so, enrolling these participants will underestimate ENDS beneficial effects. Additional concerns with cohort studies include their failure to provide optimal adjustment for prognostic variables or provide data regarding use of alternative smoking reduction aids.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our review include a comprehensive search; assessment of eligibility, risk of bias and data abstraction independently and in duplicate; assessment of risk of bias that included a sensitivity analysis addressing loss to follow-up and use of the GRADE approach in rating the certainty of evidence for each outcome.

The primary limitation of our review is the low certainty consequent on study limitations. We identified only a small number of RCTs with a modest number of participants resulting wide CIs. Moreover, loss to follow-up was substantial, and our sensitivity analysis demonstrated the vulnerability of borderline effects to missing data. The limitations of the cohort studies led us to a rating of very low-certainty evidence from which no credible inferences can be drawn.

Another limitation of this review is the fact that we could not address our hypothesis about increased rates in smoking cessation in those who used e-cigarettes with higher concentrations of nicotine compared with those using less nicotine, or daily e-cigarette users compared with non-daily e-cigarette users, or those who use newer forms of ENDS compared with users of first generation devices due to lack of evidence. However, although these assumptions seems logical, nicotine delivery from ENDS depends on other factors such as the efficiency of the device in aerosolising the liquid and user experience, apart from the concentration of nicotine in the ENDS liquid.

Furthermore, whether or not ENDS are an effective aid in the cessation of smoking may depend on whether the users were using ENDS as part of a quit attempt or not, and this may play an important role also as a possible confounder. Data is not yet available to conduct a subgroup analysis addressing this hypothesis. Subsequent trials should help provide information regarding whether their impact on cessation of smoking depends on whether users were intended to quit smoking, as well as the other unresolved issues.

Other limitations of this review were the fact of having insufficient number of included studies to allow the complete statistical analysis that we had planned. We were not able to assess publication bias because there were <10 eligible studies addressing the same outcome in a meta-analysis. We also planned to perform subgroup analyses according to the characteristics of:

participants (commitment to stopping smoking, use of e-cigarettes at baseline);

interventions (dose of nicotine delivered by the e-cigarette, frequency of use of the e-cigarette and type of e-cigarettes) and

concomitant interventions in e-cigarettes and control groups.

However, we also were not able to conduct these analyses because they did not meet our minimal criteria, which were at least five studies available, with at least two in each subgroup. A final statistical limitation is that we calculated differences from 6 to 12 months of follow-up. Absolute differences may differ across this time frame and constitute a source of variability. Moreover, there are three schools of thought with respect to use of fixed and random effect models: those who prefer always to use fixed effects, those who prefer (almost) always random effects and those who would choose fixed and random depending on the degree of heterogeneity. Each argument has its proponents within the statistical community. The argument in favour of the second rather than the third is 1) there is always some heterogeneity, so any threshold of switching models is arbitrary and 2) when there is little heterogeneity, fixed and random yield similar or identical results, so one might as well commit oneself to random from the start. We find these two arguments compelling; thus, our choice.

Finally, another limitation of the observational studies in this review is the potential for selection bias as the populations compared differ in terms of intention to quit. Furthermore, in all these RCTs, the ENDS tested were earlier generation; it is possible that later generation of e-cigarettes would have greater benefit.

Although this review presents several limitations, the issue is whether one should dismiss these results entirely or consider them bearing in mind the limitations. The latter represent our view of the matter.

Relation to prior work

The previous Cochrane review8 concluded that due to low event rates and wide CIs, only low-certainty evidence was available from studies comparing ENDS with ENNDS. We excluded some studies included in that Cochrane review as they were either case series, cross-sectional or did not include one arm with ENDS/ENNDS compared with alternative strategies. We also included one additional RCT,33 and nine new cohort studies,26–29 40–44 46 not included in the Cochrane review. The rationale for including the prospective cohort studies in our review was that it was anticipated that the search would return few RCTs. The authors of the Cochrane review found that ENDS is a useful aid to stop smoking long term compared with ENNDS.

Another review10 including two of our three RCTs,25 34–39 and further two case series and two cross-sectional studies, assessed the impact of e-cigarettes in achieving smoking abstinence or reduction in cigarette consumption among current smokers who had used the devices for 6 months or more. The authors concluded that e-cigarette use is associated with smoking cessation; these results are similar to our meta-analysis comparing ENDS with ENNDS (figure 5). Khoudigian's 2016 review11 reported a non-statistically significant trend toward smoking cessation in adults using nicotine e-cigarettes compared with other therapies or placebo. However, the review by Kalkhoran and Glatz 20169 concluded that e-cigarettes are associated with significantly less quitting among smokers.

Implications

Existing smoking reduction aids such as NRT are effective, but their impact is limited: the proportion of those who quit when using these aids remains small. The available evidence, of low or very low quality, can neither verify nor exclude the hypothesis that, because they address nicotine addiction and potentially deal with behavioural and sensory aspects of cigarette use, ENDS may be more effective than other nicotine replacement strategies. This is an important finding, and raises questions regarding how effective it may be addressing the behavioural and sensory aspects of cigarette use in their addictive potential. Thus, the focus of subsequent work should perhaps be on the dose and delivery of nicotine, though teasing out the nicotine effects from sensory aspects is likely to be challenging. It is possible that type of ENDS or dose of exposure may influence quit rates, and that newer models may be more effective, but there is insufficient data to provide insight into these issues. Lack of usefulness with regard to address the question of e- cigarettes' efficacy on smoking reduction and cessation was largely due to poor reporting.

Therefore, owing to the limitations of the studies included in this analysis it is impossible to make strong inferences regarding whether e-cigarette use promotes, has no effect or hinders smoking cessation. This review underlines the need to conduct well-designed trials in this field measuring biochemically validated outcomes and adverse effects.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Karolien Adriaens, Dr Frank Baeyen, Dr Wael Al-Delaimy, Dr Lois Biener, Dr Sarah Borderud, Dr Jamie Ostroff, Dr Chris Bullen and Dr Katrina Vickerman to provide us with additional data; and Dr Norbert Hirschhorn to provide us with the results of weekly search alerts. We also would like to thank Rachel Couban for the search strategy, and Dr Konstantinos Farsalinos, Dr Hayden McRobbie and Dr Kristian Filion for the great inputs during revisions.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to all aspects of this study, including conducting the literature search, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and writing of the paper. AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS GG, RED, WM and EAA conceived the review. DH-A undertook the searches. RED, EAS, HG, AA, YC, MP and VA screened search results. EAS organised the retrieval of papers. RED, EAS, HG, AA, YC, MP and VA screened the retrieved papers against inclusion criteria. RED, EAS, HG, AA, YC, MP and VA appraised quality of papers. RED, EAS, HG, AA, YC, MP and VA extracted data from papers. RED wrote to authors of papers for additional information. RED provided additional data about papers. RED and EAS obtained and screened data on unpublished studies. RED managed the data for the review. RED and EAS contributed in entering data into Review Manager (RevMan). RED, EAS, GHG, WM and EAA contributed in analysing RevMan statistical data. RED, EAS, GHG, WM and EAA interpreted the data. RED, EAS, GG, WM and EAA contributed in making statistical inferences. RED, GHG, WM and EAA wrote the review. RED, EAS, HG, AA, YC, MP, VA, EAA, WM and GH took responsibility for reading and checking the review before submission.

Funding: The study is funded by a WHO grant.

Disclaimer: The funding agencies played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: Regina El Dib received a Brazilian Research Council (CNPq) scholarship (CNPq 310953/2015-4).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking-50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. (accessed 21 May 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2010. (accessed 21 May 2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004. (accessed 21 May 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health benefits of smoking cessation: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 1990. (accessed 21 May 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD007253 10.1002/14651858.CD007253.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maziak W, Jawad M, Jawad S et al. . Interventions for waterpipe smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;7: CD005549 10.1002/14651858.CD005549.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Meer RM, Wagena E, Ostelo RWJG et al. . Smoking cessation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;1:CD002999 10.1002/14651858.CD002999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J et al. . Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;12:CD010216 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:116–28. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A et al. . E-cigarettes and smoking cessation: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0122544 10.1371/journal.pone.0122544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khoudigian S, Devji T, Lytvyn L et al. . The efficacy and short-term effects of electronic cigarettes as a method for smoking cessation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Int J Public Health 2016;61:257–67. 10.1007/s00038-016-0786-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al. . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC et al. , Cochrane bias methods group, Cochrane statistical methods group. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyatt GH, Busse JW. Modification of Cochrane tool to assess risk of bias in randomized trials. http://distillercer.com/resources/

- 17.Guyatt GH, Busse JW. Modification of Ottawa-Newcastle to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized trials. http://distillercer.com/resources/

- 18.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. , GRADE working group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G et al. . GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias). J ClinEpidemiol 2011a;64:407–15. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. . GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence—imprecision. J ClinEpidemiol 2011b;64:1283–93. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. , GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence—inconsistency. J ClinEpidemiol 2011c;64:1294–302. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. , GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence—indirectness. J ClinEpidemiol 2011d;64:1303–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V et al. . GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence—publication bias. J ClinEpidemiol 2011e;64:1277–82. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Sultan S et al. , GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines: 9. Rating up the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1311–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Cibella F et al. . EffiCiency and safety of an electronic cigarette (ECLAT) as tobacco cigarettes substitute: a prospective 12-month randomized control design study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e66317 10.1371/journal.pone.0066317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brose LS, Hitchman SC, Brown J et al. . Is the use of electronic cigarettes while smoking associated with smoking cessation attempts, cessation and reduced cigarette consumption? A survey with a 1-year follow-up. Addiction 2015;110: 1160–8. 10.1111/add.12917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown J, West R, Beard E et al. . Prevalence and characteristics of e-cigarette users in Great Britain: findings from a general population survey of smokers. Addict Behav 2014;39:1120–5. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hitchman SC, Brose LS, Brown J et al. . Associations between e-cigarette type, frequency of use, and quitting smoking: findings from a longitudinal online panel survey in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1187–94. 10.1093/ntr/ntv078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biener L, Hargraves JL. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use among a population-based sample of adult smokers: association with smoking cessation and motivation to quit. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:127–33. 10.1093/ntr/ntu200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akl EA, Kahale LA, Agoritsas T et al. . Handling trial participants with missing outcome data when conducting a meta-analysis: a systematic survey of proposed approaches. Syst Rev 2015;4:98 10.1186/s13643-015-0083-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akl EA, Johnston BC, Alonso-Coello P et al. . Addressing dichotomous data for participants excluded from trial analysis: a guide for systematic reviewers. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e57132 10.1371/journal.pone.0057132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adriaens K, Van Gucht D, Declerck P et al. . Effectiveness of the electronic cigarette: an eight-week Flemish study with six-month follow-up on smoking reduction, craving and experienced benefits and complaints. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:11220–48. 10.3390/ijerph111111220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M et al. . Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:1629–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bullen C, Williman J, Howe C et al. . Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial of electronic cigarettes versus nicotine patch for smoking cessation. BMC Public Health 2013;13:210 10.1186/1471-2458-13-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M et al. . Do electronic cigarettes help smokers quit? Results from a randomised controlled trial [Abstract]. European respiratory society annual congress; 7–11 September 2013, Barcelona, Spain 2013;42:215s–[P1047]. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M et al. . Electronic cigarettes and smoking cessation: a quandary?—Authors’ reply. Lancet 2014;383:408–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60146-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shahab L, Goniewicz M. Electronic cigarettes are at least as effective as nicotine patches for smoking cessation. Evid Based Med 2014;19:133 10.1136/eb-2013-101690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]