Abstract

Significant advances have been achieved in the outcomes of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) after both HLA-matched sibling donor transplants (MSDT) and non-MSDT, the latter including HLA-matched unrelated donor (MUDT) and haplo-identical donor transplants (HIDT). In this retrospective study, we analyzed the data of 85 consecutive patients with MDS who received allogeneic HSCT between Dec 2007 and Apr 2014 in our center. These patients comprised 38 (44.7%) who received MSDT, 29 (34.1%) MUDT, and 18 (21.2%) HIDT. The median overall survival (OS) was 60.2 months, the probabilities of OS being 63%, 57%, and 48%, at the first, second, and fifth year, respectively. Median OS post-transplant (OSPT) was 57.2 months, the probabilities of OSPT being 58%, 55%, and 48% at the first, second, and fifth year, respectively. The survival of patients receiving non-MSDT was superior to that of MSDT, median OSPT being 84.0 months and 23.6 months, respectively (P = 0.042); the findings for OS were similar (P = 0.028). We also found that using ATG in conditioning regimens significantly improved survival after non-MSDT, with better OS and OSPT (P = 0.016 and P = 0.025). These data suggest that using ATG in conditioning regimens may improve the survival of MDS patients after non-MSDT.

Despite the improvement in prognosis with the introduction of hypomethylating agents (HMAs)1,2, allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is still the only potentially curative treatment for selected patients with lower risk MDS and most patients with higher risk MDS. In general, HLA-matched sibling donors transplants (MSDT), which account for about 30% of transplants3, are the first choice in patients who are eligible for transplantation4,5. With the routine use of high-resolution HLA typing techniques, HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors have emerged as alternative donor sources for most patients without suitable HLA-matched sibling donors. Studies comparing MSDT and matched unrelated donors transplants (MUDT) have yielded conflicting results, some reporting inferior survival or disease-free survival (DFS) with MUDT6,7 and others reporting similar survival8,9. In recent years, haplo-identical donor transplants (HIDT) have been proved to be effective in patients with haematological malignancies, achieving comparable survival rates to those following MSDT or MUDT10,11.

However, one of the major drawbacks to non-MSDT (including MUDT and HIDT) is graft versus host disease (GVHD), which is the most important cause of death after allo-HSCT. Many approaches to minimizing GVHD complications after non-MSDT have been evaluated. Administration of antithymocyte globulin (ATG) during the conditioning regimen to promote in vivo T cell depletion of the graft is of particular interest12,13,14. Several retrospective studies have reported clinical outcomes of HIDT with an ATG-based regimen that are comparable to those of MSDT and MUDT15,16. Researchers from Zhejiang University, China prospectively compared the clinical outcome of 305 patients with haematological malignancies who underwent MSDT, MUDT, and HIDT and found that the incidence of GVHD and transplant-related mortality (TRM) were similar between MUDT and HIDT, both being higher than for MSDT13.

Most published studies on MDS have compared the results of MSDT and MUDT4,6,7,8,9. Recently, Wang et al. used data from the multicenter observational database of the Chinese Bone Marrow Transplant Registry to compare the outcomes between MSDT (n = 226) and HIDT (n = 228). They found that matched sibling donors (MSDs) remain the best donor source for patients with MDS, and that haplo-identical donors (HIDs) can be a valid alternative when an MSD is not available5. Until now, there have been few direct comparisons of the results from MSDT and non-MSDT (MUDT and HIDT). For this purpose, in the present study we retrospectively analyzed the data from our center and compared the clinical outcomes between MSDT and non-MSDT with the aim of identifying the prognostic factors that impact OS and OS post-transplant (OSPT). We further analyzed the effect of ATG on the survival of patients with MDS after allo-HSCT.

Results

Transplant-related complications

Graft-versus-host disease

Acute GVHD (aGVHD) grades I–II had occurred in 28 patients (35.9%) and grades III–IV in 15 (19.2%) at day 100 after transplantation. Ten of these patients had isolated skin aGVHD and 13 isolated intestinal GVHD. Hepatic GVHD occurred in two patients with high bilirubin and transaminase concentrations and aGVHD involved other organs in three patients. The most common type of aGVHD was involvement of two or more organs, such as skin and liver or skin and intestine. Thirty-five of the 67 patients who survived for at least 100 days post-transplantation and were thus evaluable for chronic GVHD (cGVHD).

Infectious complications

Bacterial or fungal infections had occurred by the last follow date in 52 of the 78 patients (69.4%) in whom infectious complications were evaluated. The most common type of infection was pneumonia (34 cases), which occurred repeatedly in some cases. Other infectious complications involved the digestive system (presenting with mucositis and diarrhea; 5 cases), sepsis (3 cases), skin and soft tissue (2 cases), central nervous system (1 case), or were complex infections involving two or more organs (7 cases). Cytomegalovirus (CMV) or Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) viremia was detected in 37 patients (21 with CMV, 9 with EBV, and 7 with both CMV and EBV viremia), and haemorrhagic cystitis with BK virus positivity occurred in 20 patients (25.6%).

Relapse and NRM

Relapses occurred in 16 patients (18.8%), the cumulative incidence of relapses at the first, second, and third year being 14%, 23%, and 27%, respectively. As shown in Table 1, patients with more than 5% bone marrow blasts at diagnosis and with intermediate karyotype had higher relapse rates after transplantation. In addition, disease that had progressed to advanced stage or evolved to AML was associated with higher risk of relapse after transplantation. However, the incidence of relapse did not differ significantly between patients with MSDT and non-MSDT (18.4% vs. 19.1%, respectively; P = 0.932). Similarly, whether or not ATG was included in the conditioning regimen for GVHD prophylaxis did not significantly impact the risk of disease relapse after transplant. Of note, intensive chemotherapy and/or decitabine therapy did not confer an advantage over supportive care pre-HSCT in terms of risk of relapse after transplantation (25.6% vs. 11.9%, respectively; P = 0.107).

Table 1. Correlations between relapse rate and clinical variables.

| Variables | Not relapse No. (%) | Relapse No. (%) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM blast (n = 85) | 3.85 | 0.050 | ||

| <5% | 36 (90.0) | 4 (10.0) | ||

| ≥5% | 33 (73.3) | 12 (26.7) | ||

| WHO classification (n = 85) | 3.31 | 0.191 | ||

| RCUD/RCMD/MDS-U | 34 (89.5) | 4 (10.5) | ||

| RAEB-1 | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | ||

| RAEB-2 | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) | ||

| IPSS (n = 84) | 2.73 | 0.098 | ||

| Low/Int-1 | 41 (87.2) | 6 (12.8) | ||

| Int-2/High | 27 (73.0) | 10 (27.0) | ||

| Karyotype (n = 84) | 11.19 | 0.004 | ||

| Good | 43 (91.5) | 4 (8.5) | — | |

| Int | 17 (60.7) | 11 (39.3) | ||

| Poor | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Secondary MDS (n = 85) | 1.01 | 0.449 | ||

| Yes | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| No | 58 (79.5) | 15 (20.5) | ||

| Progression pre-HSCT(n = 85) | 8.02 | 0.005 | ||

| Yes | 9 (56.2) | 7 (43.8) | ||

| No | 60 (87.0) | 9 (13.0) | ||

| Donor type (n = 85) | 0.07 | 0.932 | ||

| MSD | 31 (81.6) | 7 (18.4) | ||

| Non-MSD | 38 (80.9) | 9 (19.1) | ||

| Conditioning (n = 85) | 0.47 | 0.491 | ||

| MAC | 64 (82.1) | 14 (17.9) | ||

| RIC | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | ||

| ATG (n = 85) | 0.036 | 0.849 | ||

| Yes | 32 (82.1) | 7 (17.9) | — | |

| No | 37 (80.4) | 9 (19.6) | ||

| Therapies pre-HSCT (n = 85) | 2.60 | 0.107 | ||

| DAC ± chemotherapy | 32 (74.4) | 11 (25.6) | ||

| BSC | 37 (88.1) | 5 (11.9) |

Secondary MDS: MDS that transformed from chronic aplastic anemia; Progression pre-HSCT: MDS that progressed to advanced stage or AML; MSD: matched sibling donors; Non-MSD: including matched unrelated donors (MUD) and haplo-identical donors (HID); MAC: myeloablative conditioning; RIC: reduced intensive conditioning; ATG: Rabbitantithymocyte globulin; DAC: decitabine; BSC: basic supportive care, including erythropoiesis-stimulating agent and blood transfusion.

Overall, 38 patients had died, 30 of those deaths being from NRM. The cumulative incidence of NRM at the first, second, and third year were 13%, 23%, and 28%, respectively. NRM did not differ significantly between patients who received MAC conditioning regimens and those who received RIC regimens (P = 0.318). It is noteworthy that patients who received MSDT had higher NRM than those who received non-MSDT. The cumulative incidence of NRM at 1, 2, and 3years was 14%, 37%, and 48% in the MSDT group, which is higher than the 15%, 22%, and 26% in the non-MSDT group. Similarly, NRM occurred significantly less frequently in the ATG (9/39) than in the non-ATG cohort (21/46; P = 0.03).

Prognostic analysis

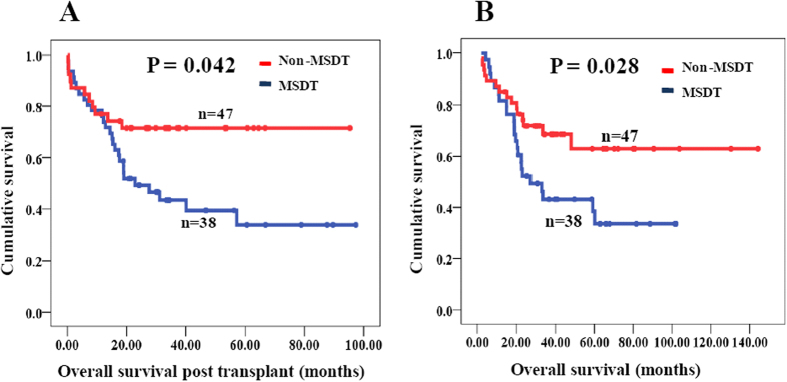

For all 85 patients who received allo-HSCT, the median OS was 60.2 months and the probabilities of OS at the first, second, and fifth year 63%, 57%, and 48%, respectively. The median OSPT was 57.2 months and the probabilities of OSPT at the first, second, and fifth year 58%, 55%, and 48%, respectively. To evaluate the impact of donor sources on the OSPT, patients were divided with two groups: MSDT and non-MSDT. The 5-year OSPT rates were 67 and 32% for non-MSDT and MSDT, respectively. The non-MSDT group had a superior survival than the MSDT group, with median OSPT of 84.0 months and 23.6 months, respectively (P = 0.042, Fig. 1A). The results were similar for OS of patients in the non-MSDT or MSDT groups (P = 0.028, Fig. 1B). The incidences of transplant-related complications in the MSDT and non-MSDT groups are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1. Overall survival post transplant (OSPT) and overall survival (OS) of MDS patients with non-MSDT and MSDT.

(A) OSPT of MDS patients with non-MSDT and MSDT; (B) OS of MDS patients with non-MSDT and MSDT. MSDT: matched sibling donor transplant; non-MSDT: non-matched sibling donor transplant, including matched unrelated donor transplants (MUDT) and haplo-identical donor transplants (HIDT).

Table 2. Transplant-related complications in MSDT and non-MSDT groups.

| Complications | MSDT No. (%) | Non-MSDT No. (%) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 0.007 | 0.932 | ||

| Yes | 7 (18.4) | 9 (19.1) | ||

| No | 31 (81.6) | 38 (80.9) | ||

| NRM | 4.387 | 0.036 | ||

| Yes | 18 (47.4) | 12 (25.5) | ||

| No | 20 (52.6) | 35(74.5) | ||

| aGVHD | 6.152 | 0.013 | ||

| Yes | 23 (71.9) | 20 (43.5) | ||

| No | 9 (28.1) | 26 (56.5) | ||

| cGVHD | 0.323 | 0.570 | ||

| Yes | 16 (50) | 20 (43.5) | ||

| No | 16 (50) | 26 (56.5) | ||

| Infection | 0.001 | 0.970 | ||

| Yes | 21 (65.4) | 30 (65.2) | ||

| No | 11 (34.4) | 16 (34.8) | ||

| EBV | 6.77 | 0.009 | ||

| Yes | 2 (6.2) | 14 (30.4) | ||

| No | 30 (93.8) | 32 (69.6) | ||

| CMV | 4.64 | 0.03 | ||

| Yes | 7 (21.9) | 21 (45.7) | ||

| No | 25 (78.1) | 25 (54.3) | ||

| HC | 0.012 | 0.914 | ||

| Yes | 8 (25) | 12 (26.1) | ||

| No | 24 (75) | 34 (73.9) |

MSDT: matched sibling donors transplant; non-MSDT: non-matched sibling donors transplant, including matched unrelated donors transplant (MUDT) and haplo-identical donors transplant (HIDT).NRM: nonrelapse mortality; Infection: bacterial and fungal infection; HC: hemorrhagic cystitis.

The results of univariate analysis of the prognostic factors affecting OS and OSPT are summarized in Table 3. Non-MSDT, peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs), and use of ATG for GVHD prevention were found to be associated with superior OS and OSPT. Additionally, EBV viremia was associated with both better OS and OSPT according to multivariate analysis. Older age and RIC regimen were predictors of worse OS. However, OS and OSPT were not influenced by sex, WHO classification, IPSS risk, or karyotype at diagnosis. Additionally, differences in pre-HSCT therapies and disease evolution did not significantly impact OS or OSPT.

Table 3. Univariate analysis of prognostic factors impacting OSPT and OS.

| Variables | No. | Median-OSPT | P-value | Median-OS | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 85) | 0.438 | 0.374 | |||

| Male | 53 | NA. | 48 | ||

| Female | 32 | 57.2 | NA. | ||

| Age (n = 85) | 0.056 | 0.047 | |||

| <40years | 43 | NA. | NA. | ||

| ≥40years | 42 | 27.6 | 32.9 | ||

| WBC (n = 85) | 0.774 | 0.691 | |||

| <4*10E9/L | 72 | 57.2 | 60.2 | ||

| ≥4*10E9/L | 13 | NA. | NA. | ||

| HB (n = 85) | 0.545 | 0.566 | |||

| <100 g/L | 70 | 57.2 | 59.1 | ||

| ≥100 g/L | 15 | 40.1 | 60.2 | ||

| PLT (n = 85) | 0.701 | 0.781 | |||

| <50*10E9/L | 54 | NA. | NA. | ||

| ≥50*10E9/L | 31 | 57.2 | 60.2 | ||

| BM blast (n = 85) | 0.809 | 0.954 | |||

| <5% | 40 | 40.1 | 60.2 | ||

| ≥5% | 45 | 57.2 | NA. | ||

| WHO classification(n = 85) | 0.554 | 0.582 | |||

| RCUD/RCMD/MDS-U | 38 | 40.1 | 60.2 | ||

| RAEB-1 | 22 | NA. | NA. | ||

| RAEB-2 | 25 | 57.2 | 59.1 | ||

| IPSS (n = 84) | 0.632 | 0.880 | |||

| Low/Int-1 | 47 | 40.1 | 60.2 | ||

| Int-2/High | 37 | NA. | 59.1 | ||

| Karyotype (n = 84) | 0.918 | 0.965 | |||

| Good | 47 | 57.2 | NA. | ||

| Int | 28 | 40.1 | 48.0 | ||

| Poor | 9 | NA. | NA. | ||

| Conditioning (n = 85) | 0.056 | 0.043 | |||

| MAC | 78 | NA. | NA. | ||

| RIC | 7 | 8.17 | 11.2 | ||

| Stem cell source (n = 85) | 0.004 | 0.004 | |||

| Marrow | 17 | 22.9 | 23.2 | ||

| PBSCs | 43 | NA. | NA. | ||

| Marrow + PBSCs | 24 | 57.2 | 59.1 | ||

| Cord | 1 | 0.4 | 4.73 | ||

| Therapies pre-HSCT(n = 85) | 0.843 | 0.902 | |||

| DAC ± chemotherapy | 43 | 57.2 | 60.2 | ||

| BSC | 42 | NA. | NA. | ||

| CR Pre-HSCT(n = 85) | 0.249 | 0.290 | |||

| Yes | 13 | NA. | NA. | ||

| No | 72 | 40.1 | 60.2 | ||

| Secondary MDS (n = 85) | 0.525 | 0.563 | |||

| Yes | 12 | 16.1 | 33.4 | ||

| No | 73 | 57.2 | 60.2 | ||

| ATG (n = 85) | 0.025 | 0.016 | |||

| Yes | 39 | NA. | NA. | ||

| No | 46 | 22.9 | 27.2 | ||

| Progressionpre-HSCT (n = 85) | 0.506 | 0.520 | |||

| Yes | 16 | 19.0 | 22.7 | ||

| No | 69 | 57.2 | 60.2 | ||

| Donor type (n = 85) | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| MSDs | 38 | 22.9 | 27.2 | ||

| MUDs | 29 | NA. | NA. | ||

| HIDs | 18 | NA. | NA. | ||

| Infection (n = 78) | 0.053 | 0.094 | |||

| Yes | 52 | 27.6 | 33.5 | ||

| No | 26 | 57.2 | NA. | ||

| aGVHD (n = 78) | 0.795 | 0.877 | |||

| Yes | 43 | 57.2 | 59.1 | ||

| No | 35 | NA. | NA. | ||

| aGVHD (n = 78) | 0.524 | 0.631 | |||

| No | 35 | NA. | NA. | ||

| I-II | 25 | NA. | NA. | ||

| III-IV | 18 | 19.0 | 27.2 | ||

| cGVHD (n = 67) | 0.069 | 0.075 | |||

| Yes | 35 | 57.2 | 59.1 | ||

| No | 32 | NA. | NA. | ||

| HC (n = 78) | 0.922 | 0.720 | |||

| Yes | 20 | NA. | 48.0 | ||

| No | 58 | 57.2 | 59.1 | ||

| EBV (n = 78) | 0.013 | 0.013 | |||

| Yes | 16 | NA. | NA. | ||

| No | 62 | 27.6 | 33.4 | ||

| CMV (n = 78) | 0.232 | 0.212 | |||

| Yes | 28 | NA. | NA. | ||

| No | 50 | 31.1 | 48.0 |

OS: overall survival; OSPT: overall survival post transplant.

Multivariate analysis indicated that EBV viremia after transplantation was the only independent factor associated with better OS and OSPT and age was the only independent predictor of shorter OS (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors impacting OSPT and OS.

| Variables | OSPT | OS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Age ≥ 40y | 2.17 (1.05–4.46) | 0.035 | ||

| RIC Conditioning | 1.08 (0.36–3.21) | 0.893 | ||

| PBSCs | 0.76 (0.46–1.25) | 0.282 | 0.70 (0.42–1.15) | 0.154 |

| MSDT | 1.32 (0.73–2.40) | 0.360 | 1.58 (0.83–3.03) | 0.167 |

| ATG | 0.42 (0.16−1.09) | 0.075 | 0.37 (0.13–1.07) | 0.067 |

| EBV | 0.22 (0.05–0.95) | 0.042 | 0.19 (0.44–0.85) | 0.029 |

OSPT: overall survival post transplant; RIC: reduced intensive conditioning; PBSCs: peripheral blood stem cells; MSDT: matched sibling donor transplant; ATG: Rabbitantithymocyte globulin.

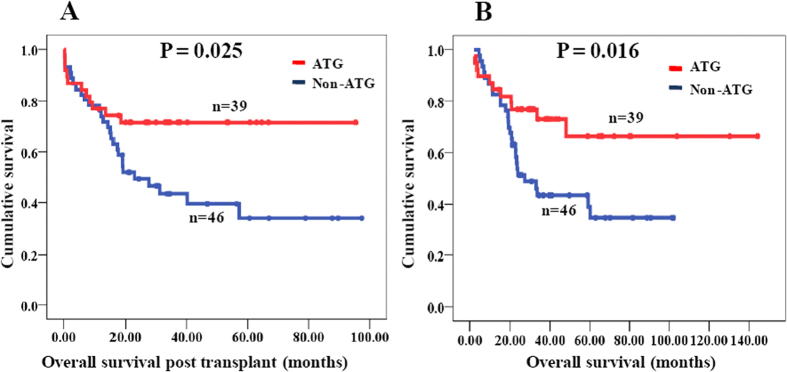

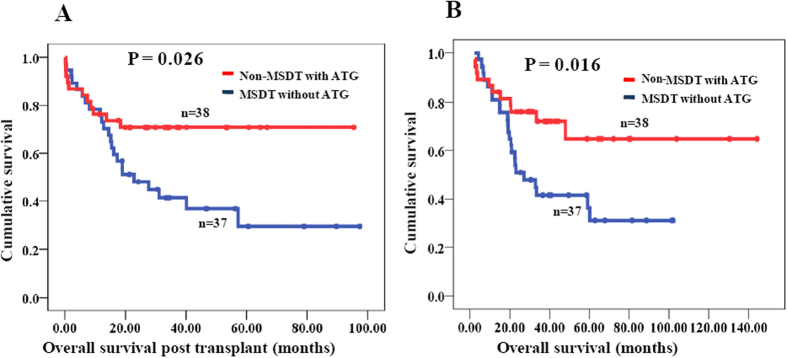

The impact of ATG on survival and transplant related complications

According to multivariate analysis, ATG tended to be associated with OSPT and OS (P = 0.075 and P = 0.067); however, this association was not statistically significant. The impact of ATG on OSPT and OS is shown in Fig. 2. Because ATG was usually used for GVHD prevention in the non-MSDT and rarely in the MSDT group, the OSPT or OS of patients who received non-MSDT with ATG (n = 38) and MSDT without ATG (n = 37) were further compared. And the result revealed that using ATG in the conditioning regimen significantly improved both OSPT and OS of in the non-MSDT group (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Overall survival post transplant (OSPT) and overall survival (OS) of MDS patients with ATG and non-ATG groups.

(A) OSPT of MDS patients with ATG and non-ATG groups; (B) OS of MDS patients with ATG and non-ATG groups.

Figure 3. Overall survival post transplant (OSPT) and overall survival (OS) of MDS patients in non-MSDT with ATG group and MSDT without ATG group.

(A) OSPT of MDS patients in non-MSDT with ATG group and MSDT without ATG group; (B) OS of MDS patients in non-MSDT with ATG group and MSDT without ATG group.

Correlations between ATG and other transplant-related complications are shown in Table 5. There was no significant difference in incidence of aGVHD (47.4% vs.62.5%; P = 0.18) or cGVHD (48.5% vs. 55.9%; P = 0.54) between the ATG and non-ATG groups. Similarly, there was no significant difference in relapse rate between these groups. However, patients in the ATG group had a significantly greater rate of CMV or EBV viremia than those in the non-ATG group (Table 5). There was also a non-significant trend to more frequent infection (bacterial and fungal) and haemorrhagic cystitis in the ATG than thenon-ATG patients (Table 5).

Table 5. Transplant-related complications in ATG and non-ATG groups.

| Complications | Non-ATG group No. (%) | ATG group No. (%) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 0.036 | 0.85 | ||

| Yes | 9 (19.6) | 7 (17.9) | ||

| No | 37 (80.4) | 32 (82.1) | ||

| NRM | 4.71 | 0.03 | ||

| Yes | 21 (45.7) | 9 (23.1) | ||

| No | 25 (54.3) | 30 (76.9) | ||

| aGVHD | 1.80 | 0.18 | ||

| Yes | 25 (62.5) | 18 (47.4) | ||

| No | 15 (37.5) | 20 (52.6) | ||

| cGVHD | 0.37 | 0.54 | ||

| Yes | 19 (55.9) | 16 (48.5) | ||

| No | 15 (44.1) | 17 (51.5) | ||

| Infection | 1.05 | 0.31 | ||

| Yes | 25 (60) | 27 (71.1) | ||

| No | 15 (40) | 11 (28.9) | ||

| EBV | 8.53 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 3 (7.5) | 13 (34.2) | ||

| No | 37 (92.5) | 25 (65.8) | ||

| CMV | 4.24 | 0.04 | ||

| Yes | 10 (25) | 18 (47.4) | ||

| No | 30 (75) | 20 (52.6) | ||

| HC | 0.43 | 0.52 | ||

| Yes | 9 (22.5) | 11 (28.9) | ||

| No | 31 (77.5) | 27 (71.1) |

Discussion

Allo-HSCT remains a curative approach to treatment for patients with MDS. In the past few years, significant advances involving all aspects of transplantation have been achieved and clinical outcomes after both MSDT and MUDT have consequently improved7. The promising outcomes achieved with HIDT have made it a valid alternative treatment option for patients lacking HLA-matched related or unrelated donors5,17,18. Thus far, few studies have directly compared the clinical outcomes of MSDT and non-MSDT in patients with MDS. In the present study, we found no significant differences in relapse or infection rates between the MSDT and non-MSDT groups. Similarly, these two groups had comparable cGVHD rates. Patients who received non-MSDT had longer OS and OSPT than those who received MSDT. The results of our study differ from those of previous studies, most of which demonstrated better prognosis for MSDT5,7,13. In our study, the superior OS and OSPT in the non-MSDT group were mainly attributable to the lower rates of NRM and aGVHD. Additionally, there was a greater percentage of patients aged less than 40 years in the non-MSDT group (non-MSDT 59.6% vs. MSDT 39.5%); older age has been suggested as a predictor of increased NRM and is correlated with adverse cytogenetic abnormalities19,20,21. In addition, a similar percentage of patients received MSDT during the years 2007–2011 and 2012–2015 (19 cases, 50% vs. 19 cases, 50%), whereas a greater percentage of patients received non-MSDT from 2012–2015 (68.1%, 32 cases) than from 2007–2011 (31.9%, 15 cases). With improvements in supportive care and management of transplant-related complications, the greater proportion of patients receiving non-MSDTs in 2012–2015 than in 2007–2011 may partly explain their superior OS and OSPT in our study.

Promising outcomes of in vivo T-cell depletion with ATG for GVHD prophylaxis and have been reported in previous studies of both MUDT and HIDT13,14,22,23. Among them were two prospective randomized trials in which patients undergoing MUDT were assigned to standard GVHD prophylaxis with or without ATG. Their findings suggested that the addition of ATG resulted in decreased acute and chronic GVHD; however, the relapse rate and OS were similar regardless of ATG administration24,25. Recently, another prospective, multicenter, randomized phase 3 study of ATG as part of a conditioning regimen in patients with acute leukemia undergoing MSDT showed that inclusion of ATG resulted in a significantly lower 2-year rate of cGVHD after MSDT than did without ATG (32.2% vs. 68.7%, respectively; P < 0.001). The survival rates were similar in the two groups26. In our study, the incidence of aGVHD and cGVHD were lower in the ATG than the non-ATG group; however, this difference was not significant. In line with other studies, the incidences of both CMV and EBV positivity were significantly higher in the ATG than the non-ATG group26,27. The transplant-related complication of viral reactivation is thought to be correlated with the delayed immune reconstitution after allo-HSCT. Additionally, administration of ATG may increase the risk of viral infections, which can be exacerbated by the use of ATG28,29,30. Interestingly, EBV positivity was a predictor of better OS or OSPT in our study, which may be attributable to the following. First, all EBV viremia were successfully treated in our study. Second, there was a strong correlation between ATG and EBV positivity and ATG suggested better survival in our study.

The dosage of ATG may also significantly influence the clinical outcome after HSCT. In a retrospective study of 465 patients treated with RIC and ATG, doses of ATG exceeding 10 mg/kg were associated with inferior even-free survival and OS31. Another study from Hamadani et al. reported improved NRM and infection rate with reduction in the dose of ATG from 7.5 mg/kg to 6 mg/kg in patients undergoing RIC–HSCT (including MSDT and MUDT) without compromising the control of aGVHD32. Devillier et al. reported that an ATG dose of 5 mg/kg in the setting of RIC was associated with a dramatically lower incidence of both aGVHD and cGVHD than a dose of 2.5 mg/kg, without a significant increase in relapse rate in patients receiving MSDT33. A recent randomized clinical study enrolled 224 patients with standard-risk hematological malignancies who underwent unmanipulated HIDT; 112 of them received 6 mg/kg ATG and the other 112 10 mg/kg ATG. These researchers found that 6 mg/kg ATG decreased the risk of EBV reactivation compared with 10 mg/kg ATG (9.6% vs.25.3%, P = 0.001); however, the lower-dose treatment was associated with a higher risk of severe aGVHD (16.1% vs.4.5%, P = 0.005)34. In our study, most patients received the MAC regimen and a total dose of 10 mg/kg ATG was used pre-HSCT (2.5 mg/kg/day for 4 days). Overall, the optimal dose of ATG in both MSDT and non-MSDT remains unclear and warrants further studies.

The graft versus leukemia (GVL) effect of non-MSDT was not superior to that of MSDT. There was no significant difference in relapse rates between MSDT and non-MSDT in our study, which is in contrast with reports from some previous studies5. Although our data should be interpreted cautiously because of our small patient cohort, our results are similar to those of another two studies13,35. The lower relapse rate in our study may be attributable to the following. First, half the patients in our study were younger than 40 years and most patients received MAC (78/85) conditioning regimens, in contrast to previous studies, which contained a greater percentage of older patients and in which RIC conditioning regimens were administered4,7. Second, administration of prophylactic donor lymphocyte infusions, which reportedly provide useful immunotherapy for managing post-transplantation relapses36, may have contributed to reducing the relapse rates of several patients with refractory disease in our study. Finally, several patients received low dose HMAs for thrombocytopenia after transplantation, which may have played a role in decreasing relapse rates after transplant37.

Our study has several limitations. Because we had no data concerning mutations in some patients, we were unable to evaluate the prognostic effect of mutations such as DNMT3a, TP53, and TET2, which have been shown to be correlated with poor prognosis38. Another limitation is that insufficient data on ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase, blood transfusion, and coexistence of other comorbidities limited our ability to incorporate these important variables into the analysis. Importantly, our analysis was retrospective and the cohort was small.

In all, despite its retrospective nature and small number of participants, our results indicate that ATG has a beneficial effect in patients with MDS undergoing non-MSDT, being associated with superior survival and a low rate of NRM. These results provide a framework for the refinement and further development of the use of ATG in allo-HSCT, which may have a significant effect on the probability of a favorable outcome.

Materials and Methods

Patient characteristics

Data of 85 consecutive patients with MDS who had received allo-HSCT between December 2007 and April 2014 in the first affiliated hospital of Suchow University were analyzed in our study. Informed consent was obtained from the patients before data collection in accordance with institutional guidelines, and the study was approved by the Committees for the Ethical Review of Research at the first affiliated hospital of Suchow University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Patient clinical characteristics were shown in Supplemental file.

Allo-HSCT was considered for patients with higher-risk MDS. Patients with lower-risk MDS (RCUD, MDS-U) with evidence of progression or sustained profound cytopenia (defined as a neutrophil count <0.5 × 109/L and/or platelet count <20 × 109/L) or severe blood transfusion dependence were also considered as candidates for allo-HSCT.

Donor Selection and HLA-Typing

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donors transplants (MSDT) were the first choice for allo-HSCT. If an MSD was unavailable, a suitably matched unrelated donor (MUD) was used, suitable closeness of HLA-matching being defined as >8/10 matching HLA-A, B, C, DR, and DQ loci. Patients without MSD or MUD or whose clinical condition precluded taking the time required for MUD search were eligible for haploidentical donors transplants (HIDT).

Transplant procedure and GVHD prophylaxis

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) (5 μg/kg per day) was used to mobilize bone marrow and peripheral blood. The target mononuclear cell and CD34+cell counts were ≥6 × 108/kg and ≥2 × 106/kg of recipient weight, respectively. Fresh and un-manipulated bone marrow and peripheral blood stem cells (retrieved on Day 5 after G-CSF) were infused into the recipient on the day of collection.

The majority of patients (n = 78, 91.8%) received MAC regimens, the remaining seven receiving RIC regimens. The details of conditioning regimens in MSDT and non-MSDT were shown in supplemental file.

All patients received GVHD prophylaxis consisting of cyclosporine, mycophenolatemofetil and methotrexate.

Study endpoints, definitions and statistical analysis

Endpoints were OS and OS post transplant (OSPT). OS was defined from the time of diagnosis until death from any cause or until the last follow-up and OSPT from the date of transplant until death from any cause or until the last follow-up. Non-relapse morbidity (NRM) was defined as death from any cause other than disease progression or relapse. Relapse was defined as morphological recurrence of disease. Correlations between the frequencies of different groups were analyzed using the χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests. Distributions of OS and OSPT curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. OS or OSPT were compared between groups using the log-rank test. Prognostic factors with P < 0.05 by univariate analysis were entered into a Cox proportional hazards model to determine the effects of those factors on survival. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant if P values were less than 0.05 in a two-tailed test. All analyses were performed using an SPSS software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, H. et al. Antithymocyte globulin improves the survival of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome undergoing HLA-matched unrelated donor and haplo-identical donor transplants. Sci. Rep. 7, 43488; doi: 10.1038/srep43488 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81100342 and No. 81270617).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Hong Wang: Design of study, acquisition of funding, contribution of patients, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Hong Liu: Design of study, contribution of patients, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Jin-Yi Zhou: Design of study, contribution of patients, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. Tong-Tong Zhang: Acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Song Jin: Acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and revising the manuscript. Xiang Zhang: Analysis of data, acquisition of data, and revising the manuscript. Su-Ning Chen: Interpretation of data, drafting the article, and revising the manuscript. Wei-Yang Li: Interpretation of data, drafting the article, and revising the manuscript. Yang Xu: Analysis of data, interpretation of data, and revising the manuscript; Miao Miao: Design of study, contribution of patients, analysis of data, and writing of manuscript. De-Pei Wu: Design of study, contribution of patients, analysis of data, writing of manuscript, and acquisition of funding.

References

- Fenaux P. et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol 10, 223–232 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian H. et al. Decitabine improves patient outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes: results of a phase III randomized study. Cancer 106, 1794–1803 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty P. G. et al. Marrow transplantation from HLA-matched unrelated donors for treatment of hematologic malignancies. Transplantation 51, 443–447 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saber W. et al. Impact of donor source on hematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Blood 122, 1974–1982 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Haploidentical transplant for myelodysplastic syndrome: registry-based comparison with identical sibling transplant. Leukemia (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima M. et al. Phase I/II study of gemtuzumab ozogamicin added to fludarabine, melphalan and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for high-risk CD33 positive myeloid leukemias and myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia 22, 258–264 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Z. et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for patients 50 years or older with myelodysplastic syndromes or secondary acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 28, 405–411 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alyea E. P. et al. Comparable outcome with T-cell-depleted unrelated-donor versus related-donor allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 8, 601–607 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler C. et al. Extended follow-up of methotrexate-free immunosuppression using sirolimus and tacrolimus in related and unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood 109, 3108–3114 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Haploidentical vs identical-sibling transplant for AML in remission: a multicenter, prospective study. Blood 125, 3956–3962 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D. P. et al. Conditioning including antithymocyte globulin followed by unmanipulated HLA-mismatched/haploidentical blood and marrow transplantation can achieve comparable outcomes with HLA-identical sibling transplantation. Blood 107, 3065–3073 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Who is the best donor for a related HLA haplotype-mismatched transplant? Blood 124, 843–850 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y. et al. T-cell-replete haploidentical HSCT with low-dose anti-T-lymphocyte globulin compared with matched sibling HSCT and unrelated HSCT. Blood 124, 2735–2743 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. H. et al. Feasible outcomes of T cell-replete haploidentical stem cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21, 342–349 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P. J. et al. Outcomes of pediatric bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and myelodysplasia using matched sibling, mismatched related, or matched unrelated donors. Blood 116, 4007–4015 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao-Jun H. et al. Partially matched related donor transplantation can achieve outcomes comparable with unrelated donor transplantation for patients with hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 15, 4777–4783 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bartolomeo P. et al. Haploidentical, unmanipulated, G-CSF-primed bone marrow transplantation for patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies. Blood 121, 849–857 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X. et al. Long-term outcome of HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without in vitro T-cell depletion based on an FBCA conditioning regimen for hematologic malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant 50, 1092–1097 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakoub-Agha I. et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia: a long-term study of 70 patients-report of the French society of bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol 18, 963–971 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino R. et al. Evidence for a graft-versus-leukemia effect after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 100, 2243–2245 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Witte T. et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with myelo-dysplastic syndromes and secondary acute myeloid leukaemias: a report on behalf of the Chronic Leukaemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Br J Haematol 110, 620–630 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohty M. et al. Antithymocyte globulins and chronic graft-vs-host disease after myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation from HLA-matched unrelated donors: a report from the Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle et de Therapie Cellulaire. Leukemia 24, 1867–1874 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peccatori J. et al. Sirolimus-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis promotes the in vivo expansion of regulatory T cells and permits peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from haploidentical donors. Leukemia 29, 396–405 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke J. et al. Standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin in haematopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: a randomised, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 10, 855–864 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupo A. et al. Thymoglobulin prevents chronic graft-versus-host disease, chronic lung dysfunction, and late transplant-related mortality: long-term follow-up of a randomized trial in patients undergoing unrelated donor transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 12, 560–565 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger N. et al. Antilymphocyte Globulin for Prevention of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. N Engl J Med 374, 43–53 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C. et al. Comparison of conditioning regimens with or without antithymocyte globulin for unrelated cord blood transplantation in children with high-risk or advanced hematological malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21, 707–712 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemans C. A. et al. Impact of thymoglobulin prior to pediatric unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation on immune reconstitution and clinical outcome. Blood 123, 126–132 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaenman J. M. et al. Early CMV viremia is associated with impaired viral control following nonmyeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation with a total lymphoid irradiation and antithymocyte globulin preparative regimen. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17, 693–702 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter C. et al. Serious infection risk and immune recovery after double-unit cord blood transplantation without antithymocyte globulin. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17, 1460–1471 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michallet M. et al. Predictive factors for outcomes after reduced intensity conditioning hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematological malignancies: a 10-year retrospective analysis from the Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle et de Therapie Cellulaire. Exp Hematol 36, 535–544 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadani M. et al. Improved nonrelapse mortality and infection rate with lower dose of antithymocyte globulin in patients undergoing reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15, 1422–1430 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devillier R. et al. The increase from 2.5 to 5 mg/kg of rabbit anti-thymocyte-globulin dose in reduced intensity conditioning reduces acute and chronic GVHD for patients with myeloid malignancies undergoing allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 47, 639–645 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Influence of two different doses of antithymocyte globulin in patients with standard-risk disease following haploidentical transplantation: a randomized trial. Bone Marrow Transplant 49, 426–433 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringden O. et al. The graft-versus-leukemia effect using matched unrelated donors is not superior to HLA-identical siblings for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 113, 3110–3118 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guieze R. et al. Management of Myelodysplastic Syndrome Relapsing after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Study by the French Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cell Therapies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22, 240–247 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj G. et al. Impact of azacitidine before allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndromes: a study by the Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle et de Therapie-Cellulaire and the Groupe-Francophone des Myelodysplasies. J Clin Oncol 30, 4533–4540 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar R. et al. Somatic mutations predict poor outcome in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 32, 2691–2698 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.