Abstract

Methods to selectively detect and manipulate nuclear spins by single electrons of solid-state defects play a central role for quantum information processing and nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). However, with standard techniques, no more than eight nuclear spins have been resolved by a single defect centre. Here we develop a method that improves significantly the ability to detect, address and manipulate nuclear spins unambiguously and individually in a broad frequency band by using a nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centre as model system. On the basis of delayed entanglement control, a technique combining microwave and radio frequency fields, our method allows to selectively perform robust high-fidelity entangling gates between hardly resolved nuclear spins and the NV electron. Long-lived qubit memories can be naturally incorporated to our method for improved performance. The application of our ideas will increase the number of useful register qubits accessible to a defect centre and improve the signal of nanoscale NMR.

Single electrons of solid-state defects can be used to detect nearby nuclear spins, but so far only a few at a time have been resolved. Here the authors propose an approach based on delayed entanglement echo that demonstrates improved detection and manipulation capabilities of nuclear spins by an NV centre.

Nuclear spins are natural quantum bits with long coherence times for quantum information tasks1 and they encode information about the structure of molecules and materials in a form that is accessible to nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques2 or electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR)3. However, because of the weak magnetic moments of nuclear spins and their similar precession frequencies, it is challenging to detect and control nuclear spins individually. The nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centre in diamond represents a promising nanoscale platform for detection and coherent control of such nuclear spins4,5,6. In type IIa diamonds, the decoherence of the NV electron spin is dominated by the presence of 13C nuclei. However, when properly controlled, the 13C nuclei in the vicinity of an NV centre become useful resources7,8,9 for quantum computing purposes. Furthermore, shallow implanted NV centres can be used to detect the signal of nuclear spins on the surface10,11, which opens opportunities for both quantum simulation12 and single molecule NMR11.

Using magnetic resonance techniques originally developed in NMR, nuclear spins have successfully been detected by single NV centres6,10,11,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Among them, dynamical decoupling (DD) techniques2,20 provide remarkable advantages, including significant extension of qubit coherence times and, more importantly, the ability of addressing single nuclear spins13,14,15,21,22. Nevertheless, standard DD techniques can only be used to address a few nuclear spins because of a number of drawbacks such as low spectral resolution23, resonance ambiguities24,25 and perturbations from the electron-nuclear coupling21. In this respect ENDOR techniques are applied to improve the spectral resolution by measuring the NV signal over long evolution times23,26,27, but without the abilities of individual spin addressing and control. The main reason of the lack of selective addressing comes from the unfiltered coupling to undesired nuclear spins such as those in the spin bath. Moreover, in spin detection the presence of undesired coupling unavoidably produces noise on the sensor electron and reduces the sensitivity. For example, the signals from the target nuclear spins which has weaker coupling can be damaged by those with stronger coupling, regardless of the potential high spectral resolution. As a consequence reported results using the ENDOR techniques18,23,26,27 provide high spectral resolution but do not demonstrate any increase in the number of detectable nuclear spins by sensor electrons comparing with the achieved numbers by standard DD techniques6,14. Note that individual addressing of nuclear spins and the implementation of quantum gates on them are more demanding than nuclear-spin detection, but essential in quantum information processing and thorough characterization of nuclear spins.

Our method overcomes these difficulties to selectively address specific nuclear spins by applying radio frequency (RF) fields in a delay window, while the entanglement with the electron spin sensor is preserved by a subsequent Hahn echo operation2. In this manner highly selective entangling gates between the electron spin and different target nuclear spins can be achieved via selective double resonance. We demonstrate that with our method one can address, control, and identify nuclear spins and spin clusters that are not detectable by standard DD techniques. Additionally, our protocol provides the ability to identify the number of nuclear spins sharing an unresolvable signal dip in the resonance spectrum. Furthermore, we show how one can individually address nuclear spins to perform high-fidelity two-qubit quantum gates between the NV electron qubit and the addressed nuclear qubit in a robust way, even when they are hardly resolved in spectrum. We also show how the efficiency of our method can be enhanced by using a nuclear memory, which has coherence times much larger than the life time of the electron spin of the sensor.

Results

Working principle

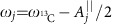

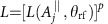

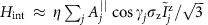

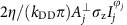

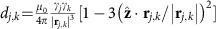

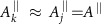

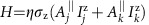

Now we describe the details of our method. A magnetic field  parallel to the NV symmetry axis splits the spin triplet of the orbital ground electronic state of the NV centre. We use two of the three levels ms=0, ±1 to define an NV electron spin qubit4. Under a strong magnetic field such that the nuclear Zeeman energies exceed the perpendicular components,

parallel to the NV symmetry axis splits the spin triplet of the orbital ground electronic state of the NV centre. We use two of the three levels ms=0, ±1 to define an NV electron spin qubit4. Under a strong magnetic field such that the nuclear Zeeman energies exceed the perpendicular components,  , of the hyperfine field Aj at the locations of nuclear spins, see Fig. 1a, the interaction between the NV electron spin and its surrounding nuclear spins is described by (Supplementary Note 1)

, of the hyperfine field Aj at the locations of nuclear spins, see Fig. 1a, the interaction between the NV electron spin and its surrounding nuclear spins is described by (Supplementary Note 1)

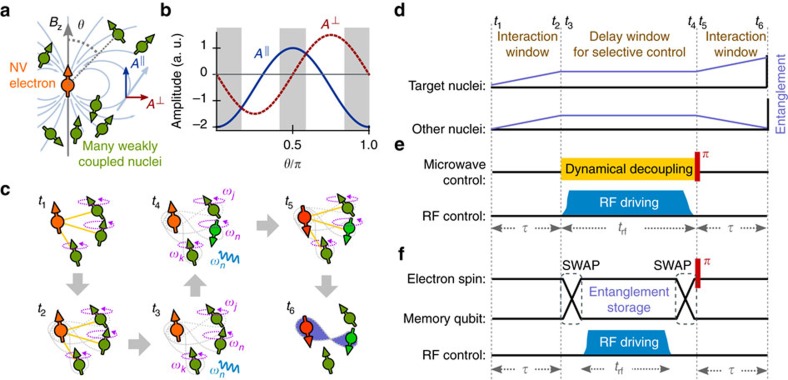

Figure 1. Delayed entanglement control between the electron and its surrounding nuclear spins.

(a) A large number of nuclear spins weakly coupled to the electron spin of NV centre by the hyperfine field. (b) Relative amplitudes of the components of the hyperfine field. The perpendicular component  is weaker than the parallel component A|| at the shaded regions of the plot. (c) Illustration of the spin states in the process of delayed entanglement echo, with the entanglement changes sketched in d. Implementation of the delay window by DD (e) or by storing the entanglement to a long-lived memory qubit (f). During the delay window, the driving at RF frequencies provides highly selective control on nuclear spins for addressing. A π pulse applied at the end of the delay window eliminates the coupling from unwanted nuclei as well as static noise.

is weaker than the parallel component A|| at the shaded regions of the plot. (c) Illustration of the spin states in the process of delayed entanglement echo, with the entanglement changes sketched in d. Implementation of the delay window by DD (e) or by storing the entanglement to a long-lived memory qubit (f). During the delay window, the driving at RF frequencies provides highly selective control on nuclear spins for addressing. A π pulse applied at the end of the delay window eliminates the coupling from unwanted nuclei as well as static noise.

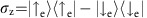

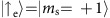

|

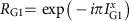

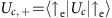

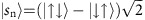

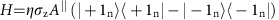

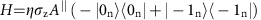

with  . Here we use

. Here we use  as one of the qubit states while the second qubit state may be

as one of the qubit states while the second qubit state may be  , when η=1/2, or

, when η=1/2, or  with η=1. For each nuclear spin,

with η=1. For each nuclear spin,  denotes the component of Aj parallel to the nuclear spin quantization axes (see Fig. 1a,b). The nuclear precession frequencies are shifted by

denotes the component of Aj parallel to the nuclear spin quantization axes (see Fig. 1a,b). The nuclear precession frequencies are shifted by  , which can be used to address individually nuclear spins of the same species (homonuclear spins).

, which can be used to address individually nuclear spins of the same species (homonuclear spins).

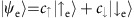

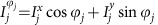

An initial superposition state of the electron spin  loses its coherence because of the electron-nuclear coupling Hint. This effect can be removed by a Hahn echo. In our case, a microwave π pulse exchanges the states

loses its coherence because of the electron-nuclear coupling Hint. This effect can be removed by a Hahn echo. In our case, a microwave π pulse exchanges the states  and effectively reverses Hint→−Hint. When the evolutions before and after the π pulse have the same duration τ, entanglement from all the nuclear spins is erased, preserving the electron spin coherence. In this manner, the nuclei are effectively decoupled from the electron. However, no nuclear spins can be addressed in this way.

and effectively reverses Hint→−Hint. When the evolutions before and after the π pulse have the same duration τ, entanglement from all the nuclear spins is erased, preserving the electron spin coherence. In this manner, the nuclei are effectively decoupled from the electron. However, no nuclear spins can be addressed in this way.

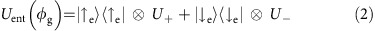

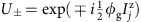

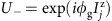

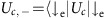

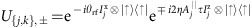

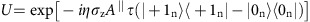

To preserve the coupling with a target spin while eliminating the influence of the rest on our sensor, we apply RF driving at the precession frequency of the target spin during the delay window. By flipping the target spin j by an angle θrf=π, we selectively rephase its interaction with the electron spin and realize a quantum gate

|

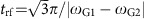

with  and

and  , up to single-spin rotations. Note that, by choosing a proper rotating frame, this is equivalent to write U+=I and

, up to single-spin rotations. Note that, by choosing a proper rotating frame, this is equivalent to write U+=I and  . Hence, we can generate entanglement between the NV centre and selected nuclear spins which forms a key ingredient of our method (see Fig. 1c,d). Note that it is not essential that θrf=π as almost any choice of θrf ≠2mπ (m being an integer number) will create entanglement with the target and lead to a coherence dip in the electron spin spectrum. In addition, more than one nuclear spin can be addressed in the same delay window by using RF driving with different frequencies. Now, we describe two strategies to achieve selective nuclear spin control in the delay window.

. Hence, we can generate entanglement between the NV centre and selected nuclear spins which forms a key ingredient of our method (see Fig. 1c,d). Note that it is not essential that θrf=π as almost any choice of θrf ≠2mπ (m being an integer number) will create entanglement with the target and lead to a coherence dip in the electron spin spectrum. In addition, more than one nuclear spin can be addressed in the same delay window by using RF driving with different frequencies. Now, we describe two strategies to achieve selective nuclear spin control in the delay window.

Spin addressing and high-fidelity quantum gate

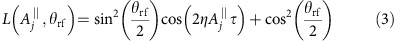

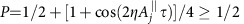

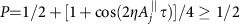

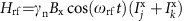

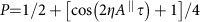

The first procedure corresponds to use DD techniques to suppress electron-nuclear interactions and to protect the NV coherence during the delay window, while the RF driving is applied to achieve selective rotations on the target nuclei (Fig. 1e). In nuclear spin sensing protocols, the electron qubit is initialized in an equally weighted superposition state  and its population signal at the end of the protocol P=(1+L)/2 is directly related to the observable of NV electron coherence15

and its population signal at the end of the protocol P=(1+L)/2 is directly related to the observable of NV electron coherence15

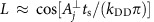

with ρe being the reduced density matrix of electron qubit. Figure 2a,b shows the obtained spectrum when scanning the frequency of the RF driving applied at the delay window, for a diamond sample of natural abundance (1.1%) with 736 13C spins. The NV coherence at the delay window is protected by the Carr–Purcell (CP) sequence2. Note that we can also use modified versions21,28,29 of CP sequence by changing the phases of pulses to provide improved robustness at the present of control errors. When the RF frequency ωrf matches one of the nuclear precession frequencies that, under strong magnetic fields, read

with ρe being the reduced density matrix of electron qubit. Figure 2a,b shows the obtained spectrum when scanning the frequency of the RF driving applied at the delay window, for a diamond sample of natural abundance (1.1%) with 736 13C spins. The NV coherence at the delay window is protected by the Carr–Purcell (CP) sequence2. Note that we can also use modified versions21,28,29 of CP sequence by changing the phases of pulses to provide improved robustness at the present of control errors. When the RF frequency ωrf matches one of the nuclear precession frequencies that, under strong magnetic fields, read  (with

(with  denoting the bare Larmor frequency of 13C) we observe the coherence contributed by the corresponding spin under on-resonant RF driving (see Methods)

denoting the bare Larmor frequency of 13C) we observe the coherence contributed by the corresponding spin under on-resonant RF driving (see Methods)

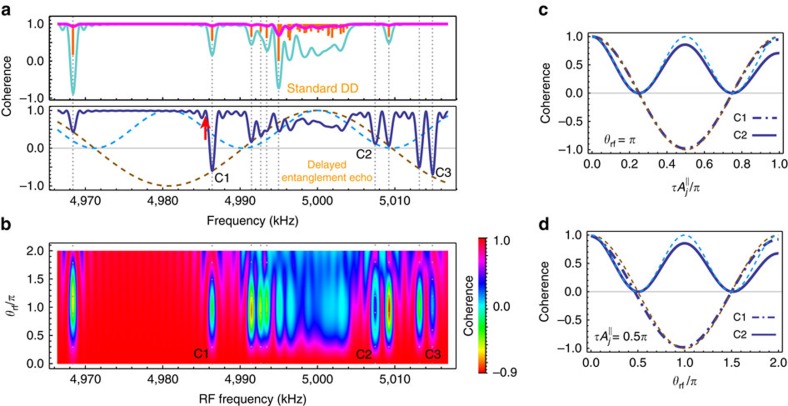

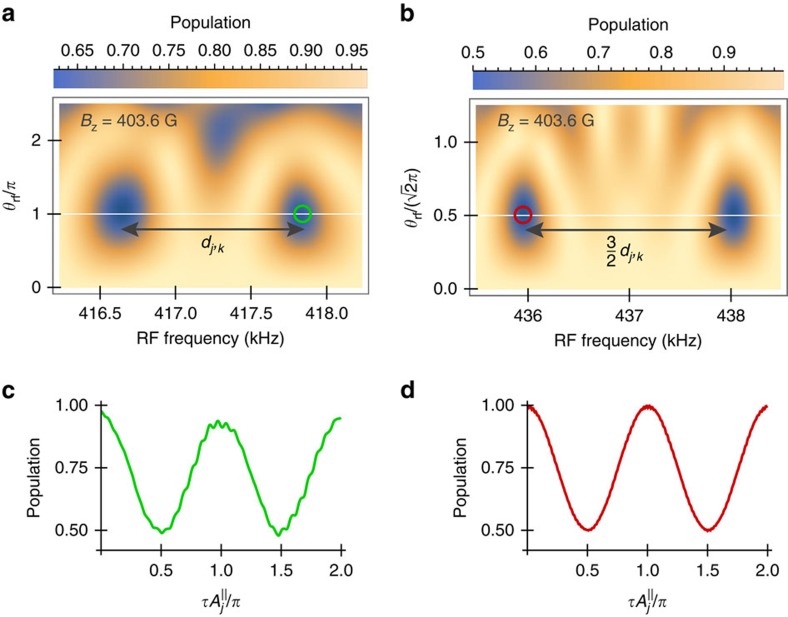

Figure 2. Coherence signals of delayed entanglement echo.

(a) Comparison between the delayed entanglement echo and standard DD method on the coherence dips of NV electron qubit by using the electron spin levels ms=0 and +1. The magenta (turquoise) solid line shows the population signal of standard DD method by 100-pulse (400-pulse) CP sequences as a function of the frequency kDD/(2τCP), where the harmonic branches kDD=25 (99) are chosen for a sequence duration of ≈1 ms. The blue solid line shows the signal of delayed entanglement echo with the interaction time τ=13 μs, and the RF driving for the single-spin rotation angle θrf=π is protected by 100-pulse CP sequences to achieve a duration of ≈1 ms. The dashed lines show the expected height of the signal dips Lp(ωrf—ω13C,θrf) for the delayed entanglement echo (see equation (3)) when there are one (p=1, brown) or two (p=2, cyan) spins at the corresponding spectral position. The lengths of the vertical orange lines are proportional to  , and the vertical dotted lines show the precession frequencies ωj (bare Larmor frequency ω13C=2π × 5 MHz). (b) Signal of delayed entanglement echo as in a but changing θrf and transferring the NV electron qubit to the levels ms=±1 for the interaction windows. (c,d) Coherence oscillations when changing τ and θrf using the scheme in b.

, and the vertical dotted lines show the precession frequencies ωj (bare Larmor frequency ω13C=2π × 5 MHz). (b) Signal of delayed entanglement echo as in a but changing θrf and transferring the NV electron qubit to the levels ms=±1 for the interaction windows. (c,d) Coherence oscillations when changing τ and θrf using the scheme in b.

|

which lies in the range  . For the case of θrf=π we have a maximum signal

. For the case of θrf=π we have a maximum signal  . When there are a number p of nuclear spins with indistinguishable precession frequencies ωj≈ωrf the coherence signal becomes

. When there are a number p of nuclear spins with indistinguishable precession frequencies ωj≈ωrf the coherence signal becomes  . The one-to-one correspondence between L and ωj (see the brown dashed lines on Fig. 2 for p=1 and the cyan dashed lines for p=2, and compare the brown dashed lines with the signals of C1 and C3, as well as the cyan dashed lines with the dip of C2) and the coherence patterns in Fig. 2c,d easily identify the number of nuclear spins in a dip, even when they are not resolved in the spectrum. Because of the relation between the interaction strength and the spectral position of a signal dip, we know the electron-nuclear interactions when we set the RF driving at the frequency of the signal dip. In this manner, we can selectively control the nuclear spins creating the signal dip.

. The one-to-one correspondence between L and ωj (see the brown dashed lines on Fig. 2 for p=1 and the cyan dashed lines for p=2, and compare the brown dashed lines with the signals of C1 and C3, as well as the cyan dashed lines with the dip of C2) and the coherence patterns in Fig. 2c,d easily identify the number of nuclear spins in a dip, even when they are not resolved in the spectrum. Because of the relation between the interaction strength and the spectral position of a signal dip, we know the electron-nuclear interactions when we set the RF driving at the frequency of the signal dip. In this manner, we can selectively control the nuclear spins creating the signal dip.

Our method works well even when the perpendicular components of hyperfine field  =0 (see Fig. 1a,b). Note that standard methods13,14,15,21,22,30,31 on spin detection based on DD techniques require both

=0 (see Fig. 1a,b). Note that standard methods13,14,15,21,22,30,31 on spin detection based on DD techniques require both  and

and  to be different from zero. In this respect, Fig. 2a shows the signal obtained with standard DD13,14,15 by scanning the pulse interval

to be different from zero. In this respect, Fig. 2a shows the signal obtained with standard DD13,14,15 by scanning the pulse interval  of the CP sequences. The coherence signal

of the CP sequences. The coherence signal  is determined by the strength of

is determined by the strength of  for a sequence duration ts, when the kDD-th harmonic branch matches the precession frequency ωj (that is, kDDωDD=ωj)22. Therefore, nuclear spins with

for a sequence duration ts, when the kDD-th harmonic branch matches the precession frequency ωj (that is, kDDωDD=ωj)22. Therefore, nuclear spins with  =0 (for example, C2 and C3 in Fig. 2a) are not detected by standard DD techniques. Furthermore, in Fig. 2a the signal obtained by DD is weak when compared with our method for the same number of 100 π pulses. See Supplementary Note 2 for a discussion of standard DD methods, a more detailed comparison with our technique, and other shortcomings of standard DD techniques.

=0 (for example, C2 and C3 in Fig. 2a) are not detected by standard DD techniques. Furthermore, in Fig. 2a the signal obtained by DD is weak when compared with our method for the same number of 100 π pulses. See Supplementary Note 2 for a discussion of standard DD methods, a more detailed comparison with our technique, and other shortcomings of standard DD techniques.

In addition, our protocol allows to enhance the interaction and, therefore, the obtained signal by transferring the electronic state  to

to  for the interaction windows (t1, t2) and (t5, t6) in Fig. 1, with the results shown in Fig. 2b. In contrast, homonuclear spins can not be distinguished by the standard DD methods13,14,15 when the qubit states ms=±1 are used, because the averaged nuclear precession frequencies are not shifted by the hyperfine field (Supplementary Note 2) and are not resolvable in spectrum.

for the interaction windows (t1, t2) and (t5, t6) in Fig. 1, with the results shown in Fig. 2b. In contrast, homonuclear spins can not be distinguished by the standard DD methods13,14,15 when the qubit states ms=±1 are used, because the averaged nuclear precession frequencies are not shifted by the hyperfine field (Supplementary Note 2) and are not resolvable in spectrum.

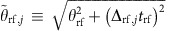

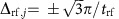

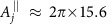

Figure 2b also shows that a change in the rotation angle θrf due to, for example, intensity fluctuations in the RF driving field does not affect the locations of signal dips, demonstrating an intrinsic robustness of our method for nuclear spin detection. The fringes that appear around θrf=2π are caused by the side excitation of the rectangular RF driving with a finite length trf. The RF driving with a frequency detuning Δrf,j≡ωrf−ωj turns the nuclear spin around an axis out of the  plane with a tilting angle αj≡arctan(Δrf,jtrf/θrf) and an effective rotation angle

plane with a tilting angle αj≡arctan(Δrf,jtrf/θrf) and an effective rotation angle  . For example, for θrf=2π there is a spin flip

. For example, for θrf=2π there is a spin flip  around the tilting axis if the detuning is

around the tilting axis if the detuning is  , giving the side fringe signal shown in Fig. 2b.

, giving the side fringe signal shown in Fig. 2b.

This single-spin contribution can be completely eliminated when  is an integer multiple of 2π, even ωj is not far detuned from the RF frequency. For example, for θrf=π a spin with a frequency detuning

is an integer multiple of 2π, even ωj is not far detuned from the RF frequency. For example, for θrf=π a spin with a frequency detuning  is rotated by the rectangular RF driving by an angle 2π. Hence, the NV centre and the nuclear spin remain disentangled and a coherence dip is not produced (for example, see the red arrow near the main C1 coherence dip in Fig. 2a).

is rotated by the rectangular RF driving by an angle 2π. Hence, the NV centre and the nuclear spin remain disentangled and a coherence dip is not produced (for example, see the red arrow near the main C1 coherence dip in Fig. 2a).

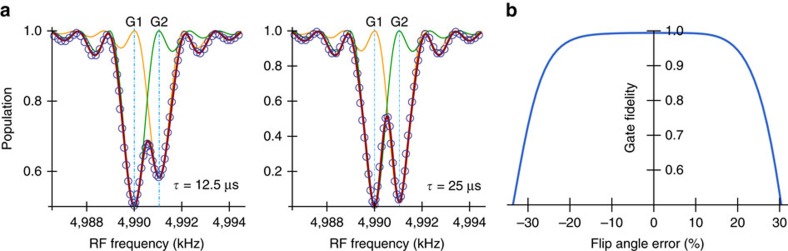

To investigate the effect of control errors from DD pulses used in our method, in Fig. 3 we consider a sample with two spectrally close 13C spins (G1 and G2). Figure 3a shows the population signals obtained by our method; during the delay window we apply ideal instantaneous decoupling control on the NV centre in the form of CP sequences (red solid lines), while the blue circles correspond to the signal when errors in the external control are present. In the latter case we modify the phases of corresponding CP pulses to the ones of adaptive XY-8 (AXY-8) sequences21 because AXY-8 sequences have good robustness against control errors. As shown in Fig. 3a, the case with errors fits well with the ideal signal even when we introduce a 10% of amplitude error on the DD pulses, and a microwave detuning error of ∼2.2 MHz caused by uncertain spin states of the strongly coupled 14N spin. As discussed above when we tune the RF-driving length to  , the spin G2 does not perturb the dynamics of the NV electron and G1 spins. This is a situation that can be confirmed by changing the time τ of the interaction window and observing that the population change of the spin G1 follows the one of a single spin (see the pattens in Fig. 2c and compare the panels of Fig. 3a). With this value of trf, we can perform high-fidelity quantum gate on only one of the spins, even through the two spins G1 and G2 are not well separated in spectrum (see Fig. 3a). In Fig. 3b, we address the spin G1 by using the RF control ωrf=ωG1 and θrf=π. The RF driving implements a π rotation gate

, the spin G2 does not perturb the dynamics of the NV electron and G1 spins. This is a situation that can be confirmed by changing the time τ of the interaction window and observing that the population change of the spin G1 follows the one of a single spin (see the pattens in Fig. 2c and compare the panels of Fig. 3a). With this value of trf, we can perform high-fidelity quantum gate on only one of the spins, even through the two spins G1 and G2 are not well separated in spectrum (see Fig. 3a). In Fig. 3b, we address the spin G1 by using the RF control ωrf=ωG1 and θrf=π. The RF driving implements a π rotation gate  around the

around the  direction, unconditional on the NV electron qubit state. If τ>0, the entanglement echo subsequently implement an entangling gate

direction, unconditional on the NV electron qubit state. If τ>0, the entanglement echo subsequently implement an entangling gate  (see equation (2)) on G1. Figure 3b shows the fidelity (see Supplementary Note 5 for the definition) of the implemented maximally entangling gate Uent(π)RG1, achieving a combined gate fidelity of 0.992 even for a 10% amplitude and ∼2π × 2.2 MHz detuning errors on the π pulses in the delay window.

(see equation (2)) on G1. Figure 3b shows the fidelity (see Supplementary Note 5 for the definition) of the implemented maximally entangling gate Uent(π)RG1, achieving a combined gate fidelity of 0.992 even for a 10% amplitude and ∼2π × 2.2 MHz detuning errors on the π pulses in the delay window.

Figure 3. Single-spin addressing at the presence of control errors.

(a) Population signals (circles) of the delayed entanglement echo. Equally spaced AXY-8 sequences with a total number of 80 π pulses (pulse length 50 ns and amplitude error 10%) are applied at the delay window, accompanied with the rectangular RF driving of the duration trf=0.827 ms. Solid lines are the signals of G1 and/or G2 spins when the delay window is protected by ideal CP control. (b) Fidelity of combined quantum gate as a function of the flip angle error, with the G1 spin being addressed. The quantum gate on the G1 spin is an unconditional π gate followed by a logical entanglement gate Uent(φg) with the NV electron qubit. Here τ=12.5 μs to achieve φg=π for a maximum entanglement gate. The no operation (NULL) gates implemented on the G2 and the intrinsic 14N spins are included in the calculation of the combined gate fidelity. Without the interaction window (φg=0) the gate on G1 is an unconditional gate. In both a,b, the unpolarized 14N spin introduces a microwave detuning error of ∼2π × 2.2 MHz, but the combined fidelity achieves a value of 0.992 even for a flip angle error of 10%. The bare Larmor frequency ω13C=2π × 5 MHz.

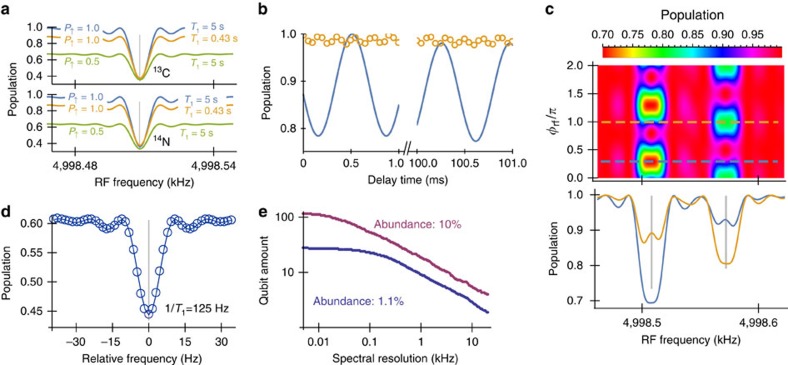

Enhanced performance via a quantum memory

An alternative strategy to achieve selective nuclear spin control in the delay window is to store the electron spin state in a long-lived nuclear spin (see Fig. 1f). In Fig. 4a, we show the NV electron spin population signal when it addresses an isolated 13C spin, by using an initially polarized nuclear memory qubit. The memory qubit can be initialized by swapping a polarized NV electron state to the memory spin or by using dynamical nuclear polarization16. Because after a swap operation (Supplementary Note 3) between the NV electron and memory qubits the electron spin gets polarized to the ms=+1 state during the delay window, it is not necessary to protect electron coherence. In addition, the shifts of the nuclear spin precession frequencies (now  under strong magnetic fields) are larger than those achieved by the method using DD or by standard DD techniques13,14,15,21,22.

under strong magnetic fields) are larger than those achieved by the method using DD or by standard DD techniques13,14,15,21,22.

Figure 4. Delayed entanglement echo by using a nuclear memory qubit.

(a) Signal dips when addressing to a single distant 13C nuclear spin ≈2.2 nm away from the NV centre by storing the qubit state in a 13C or in the intrinsic 14N memory qubit during the delay windows, for trf=100 ms, τ=100 μs, and various low-temperature electron spin relaxation times T1 and initial populations P↑ of the memory qubit state  . (b) Population modulation (solid line) caused by two interacting 13C nuclei in a C–C bond ∼1.5 nm away from the NV centre with τ=200 μs and a 14N memory. Application of LG decoupling suppresses nuclear dipolar coupling and hence the modulation (circles). (c) Signal patterns from two uncoupled distant 13C spins (2.2 and 2.3 nm away from the NV centre) when using a 14N memory qubit and DD to protect the interaction windows of duration τ=500 μs. The cross-sectional plots show the signals in the two-dimensional plot (dashed lines) when the initial RF phases φrf match the azimuthal angles of addressed nuclear spins. (d) Room-temperature signal of one proton spin placed 4 nm away from the NV centre using a 13C memory qubit and optical illumination during the delay window (Supplementary Note 5). With the RF driving of trf≈10T1, the line-width of the signal is well beyond the limit set by electron spin relaxation time 1/T1. One major reason of the reduction of signal contrast is the leakage out from the electron qubit to another electron spin triplet level. (e) Log-log plot of the average number of individual 13C register qubits with

. (b) Population modulation (solid line) caused by two interacting 13C nuclei in a C–C bond ∼1.5 nm away from the NV centre with τ=200 μs and a 14N memory. Application of LG decoupling suppresses nuclear dipolar coupling and hence the modulation (circles). (c) Signal patterns from two uncoupled distant 13C spins (2.2 and 2.3 nm away from the NV centre) when using a 14N memory qubit and DD to protect the interaction windows of duration τ=500 μs. The cross-sectional plots show the signals in the two-dimensional plot (dashed lines) when the initial RF phases φrf match the azimuthal angles of addressed nuclear spins. (d) Room-temperature signal of one proton spin placed 4 nm away from the NV centre using a 13C memory qubit and optical illumination during the delay window (Supplementary Note 5). With the RF driving of trf≈10T1, the line-width of the signal is well beyond the limit set by electron spin relaxation time 1/T1. One major reason of the reduction of signal contrast is the leakage out from the electron qubit to another electron spin triplet level. (e) Log-log plot of the average number of individual 13C register qubits with  kHz and

kHz and  different from other spins by amounts larger than the spectral resolution, by averaging over 1000 samples. A magnetic field is used for the bare Larmor frequency ω13C=2π × 5 MHz. In a,d,c, θrf=π, and θrf=0 in b. In a,b, the electron qubit state

different from other spins by amounts larger than the spectral resolution, by averaging over 1000 samples. A magnetic field is used for the bare Larmor frequency ω13C=2π × 5 MHz. In a,d,c, θrf=π, and θrf=0 in b. In a,b, the electron qubit state  is transferred to

is transferred to  during the interaction windows.

during the interaction windows.

The electron spin relaxation creates magnetic noise on the nuclear spins and can reduce the signal contrast32. However, at low temperatures, the relaxation time T1 of NV electron spin can reach minutes33. When  the effects of electron spin relaxation can be neglected. In addition, we can protect the memory qubit against the electron-relaxation noise for example by strong driving32. The coherence times of memory qubits (for example, a 13C or a 14N in Fig. 4a) are determined by the electron-relaxation time T1 when their hyperfine fields are sufficiently larger than 1/T1 (Supplementary Note 3)32. Therefore, the signal contrasts in Fig. 4a are similar for both memory qubits and we may use a more strongly coupled 13C spin as a quantum memory. Note that the use of unpolarized memory qubit still gives large signal contrast, showing that in the application of spin detection our method is insensitive to initialization error of the qubit memory (see Fig. 4a).

the effects of electron spin relaxation can be neglected. In addition, we can protect the memory qubit against the electron-relaxation noise for example by strong driving32. The coherence times of memory qubits (for example, a 13C or a 14N in Fig. 4a) are determined by the electron-relaxation time T1 when their hyperfine fields are sufficiently larger than 1/T1 (Supplementary Note 3)32. Therefore, the signal contrasts in Fig. 4a are similar for both memory qubits and we may use a more strongly coupled 13C spin as a quantum memory. Note that the use of unpolarized memory qubit still gives large signal contrast, showing that in the application of spin detection our method is insensitive to initialization error of the qubit memory (see Fig. 4a).

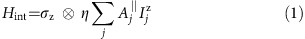

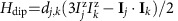

Structural information of coupled spin clusters can also be observed by our method. The dynamics of two coupled homonuclear spins under a strong magnetic field is characterized by the dipolar coupling strength dj,k (see Methods) and the difference  between the hyperfine components34. A spin pair close to the NV centre with δj,k and dj,k the same order of strengths can modulate the NV coherence34,35, in the absence of RF control as shown in Fig. 4b. Spin pairs with

between the hyperfine components34. A spin pair close to the NV centre with δj,k and dj,k the same order of strengths can modulate the NV coherence34,35, in the absence of RF control as shown in Fig. 4b. Spin pairs with  (we call this as type-h) or

(we call this as type-h) or  (called type-d) could be useful quantum resources. But these two types of spin pair were regarded as unobservable, because they form stable pseudo-spins which have negligible effects on electron coherence34. However by using our method, we can detect, identify and control these spin pairs close to the NV centre. After the delayed entanglement echo with on-resonant RF driving, the population signal (see Methods) of a type-h or a type-d spin pair

(called type-d) could be useful quantum resources. But these two types of spin pair were regarded as unobservable, because they form stable pseudo-spins which have negligible effects on electron coherence34. However by using our method, we can detect, identify and control these spin pairs close to the NV centre. After the delayed entanglement echo with on-resonant RF driving, the population signal (see Methods) of a type-h or a type-d spin pair  is different from the case of single spin, as shown in Fig. 5. The type-h and type-d spin pairs can be distinguished. For type-h pair the on-resonant RF field flips a 13C spin by θrf=π, while for type-d pair the on-resonant RF field drive the triplet state with a Rabi frequency

is different from the case of single spin, as shown in Fig. 5. The type-h and type-d spin pairs can be distinguished. For type-h pair the on-resonant RF field flips a 13C spin by θrf=π, while for type-d pair the on-resonant RF field drive the triplet state with a Rabi frequency  times as the one for single nuclear spins (compare Fig. 5a,b and see Methods).

times as the one for single nuclear spins (compare Fig. 5a,b and see Methods).

Figure 5. Population signal of coupled spin pairs.

(a) Signal patterns of a type-h 13C spin pair in a C–C bond ≈1.0 nm away from the NV centre, using the interaction time τ=10 μs and length of RF driving trf≈2 ms. The dipolar coupling strength dj,k≈2π × 1.37 kHz. The hyperfine components of the two spins  kHz and

kHz and  kHz. (b) Same as a but for a type-d pair located ≈1.55 nm away from the NV centre and τ=50 μs, and the hyperfine components of the two spins

kHz. (b) Same as a but for a type-d pair located ≈1.55 nm away from the NV centre and τ=50 μs, and the hyperfine components of the two spins  kHz and

kHz and  kHz have similar strengths. The parameters used in c,d are indicated by the circles in a,b, respectively.

kHz have similar strengths. The parameters used in c,d are indicated by the circles in a,b, respectively.

To address and control nuclear spins individually in a coupled cluster the internuclear dipolar coupling needs to be suppressed. Internuclear interactions also reduce the Hahn-echo electron coherence times and, hence, the achievable interaction times τ (available values36,37

ms for natural abundance of 13C and can be increased using lower abundance, see Supplementary Fig. 7). To solve the problem of spin interactions, we use the Lee–Goldburg (LG) off-resonance decoupling2,12,22. The LG decoupling field can remain turned on for the entire duration of our protocol, including NV electron spin initialization and readout, because the frequency of RF decoupling field is far off-resonance to the transition frequencies of the NV electron spin. This allows for the RF decoupling field to be applied by external coils and resonators to avoid possible heating on the diamond sample. When the LG decoupling field is tuned such that

ms for natural abundance of 13C and can be increased using lower abundance, see Supplementary Fig. 7). To solve the problem of spin interactions, we use the Lee–Goldburg (LG) off-resonance decoupling2,12,22. The LG decoupling field can remain turned on for the entire duration of our protocol, including NV electron spin initialization and readout, because the frequency of RF decoupling field is far off-resonance to the transition frequencies of the NV electron spin. This allows for the RF decoupling field to be applied by external coils and resonators to avoid possible heating on the diamond sample. When the LG decoupling field is tuned such that  , the dipole-dipole interactions between nuclear spins are suppressed12,22, giving rise to the effective Hamiltonian

, the dipole-dipole interactions between nuclear spins are suppressed12,22, giving rise to the effective Hamiltonian  with

with  the nuclear spin operators projected along effective rotating axes (see Supplementary Note 1). Figure 4b demonstrates the effect of LG decoupling with ΔLG=2π × 20 kHz, which can be achieved by a RF field with the amplitude much smaller than the values of ∼0.1 T in the control fields reported in refs 38, 39. The suppression of the internuclear interactions allows us to achieve longer interaction times τ and RF-driving lengths trf for single-spin addressing. The improved spectral resolution

the nuclear spin operators projected along effective rotating axes (see Supplementary Note 1). Figure 4b demonstrates the effect of LG decoupling with ΔLG=2π × 20 kHz, which can be achieved by a RF field with the amplitude much smaller than the values of ∼0.1 T in the control fields reported in refs 38, 39. The suppression of the internuclear interactions allows us to achieve longer interaction times τ and RF-driving lengths trf for single-spin addressing. The improved spectral resolution  leads to an increase of the number of individually addressable spins (see Fig. 4e).

leads to an increase of the number of individually addressable spins (see Fig. 4e).

In the case that there are other significant decoherence sources that are acting on the NV electron spin, our method can be combined with DD to further protect the NV coherence. Applying a CP sequence (or its modified versions21,28,29 for better control robustness) with an inter π-pulse interval π/ωDD and the sequence duration τ at each of the interaction windows, noise with frequencies slower than ωDD is suppressed, and at the same time the electron spin couples to nuclear spins through the interactions  when the kDD-th harmonic branch matches the precession frequency ωj up to a frequency uncertainty of

when the kDD-th harmonic branch matches the precession frequency ωj up to a frequency uncertainty of  (refs 14, 21, 22). The nuclear spin operators

(refs 14, 21, 22). The nuclear spin operators  depend on the azimuthal angles

depend on the azimuthal angles  of nuclear spins relative to the magnetic field direction. Nuclear spins unresolvable by the CP sequences may nevertheless have different precession rates. To ensure the same effective Hamiltonian at the two interaction windows, we apply a two-pulse CP sequence on the nuclear spins during the delay window to remove this inhomogeneity. Then adding a weak RF drive during the delay window allows us to address the target spins with high spectral resolutions.

of nuclear spins relative to the magnetic field direction. Nuclear spins unresolvable by the CP sequences may nevertheless have different precession rates. To ensure the same effective Hamiltonian at the two interaction windows, we apply a two-pulse CP sequence on the nuclear spins during the delay window to remove this inhomogeneity. Then adding a weak RF drive during the delay window allows us to address the target spins with high spectral resolutions.

In addition, our scheme allows to measure the spin directions  , as detailed in the following. The azimuthal directional angle φrf of RF control fields is controlled by the RF phase in the rotating frame of nuclear spin precession. When the RF driven rotation does not commute with the effective interaction Hamiltonian, it breaks the erasing process of delayed entanglement echo on the target spins, and thereby, we address the nuclear spins in a highly selective way. On the other hand, when the RF rotation axis is parallel to the azimuthal angle of a target nuclear spin (φrf=

, as detailed in the following. The azimuthal directional angle φrf of RF control fields is controlled by the RF phase in the rotating frame of nuclear spin precession. When the RF driven rotation does not commute with the effective interaction Hamiltonian, it breaks the erasing process of delayed entanglement echo on the target spins, and thereby, we address the nuclear spins in a highly selective way. On the other hand, when the RF rotation axis is parallel to the azimuthal angle of a target nuclear spin (φrf= or

or  +π), the RF driving commutes with the interaction window and the electron-nuclear entanglement is removed after the echo, giving vanishing signal dips. By measuring the RF phases φrf which cause vanishing signal dips, we obtain the relative locational directions of nuclear spins (see Fig. 4c). Note that we can combine LG decoupling with DD using recently proposed protocols22,40.

+π), the RF driving commutes with the interaction window and the electron-nuclear entanglement is removed after the echo, giving vanishing signal dips. By measuring the RF phases φrf which cause vanishing signal dips, we obtain the relative locational directions of nuclear spins (see Fig. 4c). Note that we can combine LG decoupling with DD using recently proposed protocols22,40.

Our method allows to improve the spectral resolution beyond the limit set by the room-temperature electron T1 when we decouple the nuclear memory from the electron spin at the delay window. The decoupling technique that uses optical illumination has been demonstrated to prolong the room-temperature coherence time of nuclear spin memory over one second (∼267 times of T1)32, because the optically induced NV ionization decouples the nuclear spins from the NV centre by a mechanism related to the motional averaging effect in NMR32,41. In Fig. 4d, we simulate the application of optical illumination and RF driving during the delay window to detect a proton spin placed 4 nm away from the NV centre with the interaction time τ=100 μs (Supplementary Note 5). A delay time trf≈80 ms already provide enough frequency resolution to detect a chemical shift of ∼1 p.p.m. for the applied magnetic field Bz≈0.467 T. Using a higher magnetic field can further improve the chemical shift detection. We can apply LG decoupling when there are more target spins and internuclear interactions. In addition, we can use DD to protect the interaction windows from noise for extending the interaction time τ. Electron spin coherence time of shallow NV centre has reported values of ∼1 ms using continuous DD (spin lock)11.

Discussion

In summary, we have proposed a method to address and control nuclear spins which were regarded as undetectable or unresolvable. High-fidelity quantum gates on these nuclear spins can be achieved by our method even when the external control has relative large errors and the nuclear spins present a dense resonance spectrum. Therefore, by our method more nuclear spins become useful and robust quantum resources. For example, with more reliable nuclear spins it is expected an improvement in quantum metrology assisted by quantum error correction42. The ability to address and control nuclear spins individually is also vital in the development of a solid-state quantum information processor that uses host electron spins and surrounding nuclear spins40 as well as for large-scale quantum simulators in diamond12. Our method provides a substantial advancement over the ENDOR techniques3,18,23,26,27 which do not individually address nuclear spins because of inefficient elimination of the noise from other bath spins (see Supplementary Note 4 for a discussion on the ENDOR sequences utilizing both microwave and RF control fields). As a consequence, our work is expected to find applications as well in traditional fields of NMR and ENDOR, for example, in analysis of chemical shifts. Finally, the method has a general character being equally applicable to other electron-nuclear spin systems43,44.

Methods

Signals of delayed entanglement echo

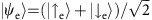

During the sensing protocol, the NV dynamics can be calculated by the methods in refs 37, 45. Given the initial electron spin state  , the population left in the original equal superposition state is P=(1+L)/2 and the NV coherence

, the population left in the original equal superposition state is P=(1+L)/2 and the NV coherence  can be expressed by the contributions Lc of spin clusters c when the interactions between different spin clusters can be neglected37,45. Because kB/ħ≈2π × 21 GHz K−1, the thermal energies are much larger than the Zeeman energies of nuclear spins at relevant temperatures. Therefore the thermal state of nuclear spins is approximately described by the identity operator up to a normalization factor. The quantity Lc reads

can be expressed by the contributions Lc of spin clusters c when the interactions between different spin clusters can be neglected37,45. Because kB/ħ≈2π × 21 GHz K−1, the thermal energies are much larger than the Zeeman energies of nuclear spins at relevant temperatures. Therefore the thermal state of nuclear spins is approximately described by the identity operator up to a normalization factor. The quantity Lc reads

|

where  ,

,  〉,

〉,  the dimension of the spin cluster c, and Uc the NV-cluster evolution37,45.

the dimension of the spin cluster c, and Uc the NV-cluster evolution37,45.

Single spins

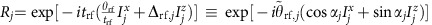

Single-spin dynamics dominate the effect on the NV electron spin37. The signal from single nuclear spins (a spin cluster c=j with one spin j) is calculated as follows. The evolution of a single nuclear spin after an interaction window with time τ is  , where η is determined by the qubit manifold used in the interaction window. During the delay window, we apply a RF driving field that rotates the nuclear spins with the evolution Rj. For resonant RF driving (that is, the RF frequency ωrf=ωj matching the nuclear precession frequency ωj), the nuclear spin is rotated by an angle θrf and

, where η is determined by the qubit manifold used in the interaction window. During the delay window, we apply a RF driving field that rotates the nuclear spins with the evolution Rj. For resonant RF driving (that is, the RF frequency ωrf=ωj matching the nuclear precession frequency ωj), the nuclear spin is rotated by an angle θrf and  (assuming rotation around the

(assuming rotation around the  direction). For the rectangular RF-driving with a duration trf and a frequency detuning Δrf,j=ωrf−ωj, we obtain the spin rotation at the delay window

direction). For the rectangular RF-driving with a duration trf and a frequency detuning Δrf,j=ωrf−ωj, we obtain the spin rotation at the delay window  . Following by another interaction window with time τ between two π pulses on the electron spin (the last π pulse is optional, but we keep it for simplicity), we have the coupled evolution between the NV electron spin and a single nuclear spin

. Following by another interaction window with time τ between two π pulses on the electron spin (the last π pulse is optional, but we keep it for simplicity), we have the coupled evolution between the NV electron spin and a single nuclear spin  , which gives the coherence signal by using equation (4). The contribution of a single spin-

, which gives the coherence signal by using equation (4). The contribution of a single spin- after the delayed entanglement echo with on-resonant RF driving is given by equation (3).

after the delayed entanglement echo with on-resonant RF driving is given by equation (3).

Coupled spin pairs

Strongly coupled nuclear spin pair (a spin cluster c={j, k} with two spins j and k) can modulate the NV electron spin dynamics. Under a strong magnetic field the dipolar coupling reads  , where rj,k is the relative position of the coupled j and k spins and γj(k) the gyromagnetic ratios. The coupled dynamics between the NV electron spin and the spin pairs of type-h

, where rj,k is the relative position of the coupled j and k spins and γj(k) the gyromagnetic ratios. The coupled dynamics between the NV electron spin and the spin pairs of type-h  and type-d

and type-d  under a strong magnetic field is shown as follows.

under a strong magnetic field is shown as follows.

For type-h pairs, homonuclear spin flip processes are suppressed and therefore the precession frequency of each nuclear spin is split by dj,k by the internuclear interaction  . The nuclear spin flip by the RF driving at the delay window is conditional to the state of the other spin in the nuclear spin pair. Similar to the calculation of single spin, the evolution after the delayed entanglement echo is

. The nuclear spin flip by the RF driving at the delay window is conditional to the state of the other spin in the nuclear spin pair. Similar to the calculation of single spin, the evolution after the delayed entanglement echo is  , after an on-resonant RF driving θrf=π to flip the nuclear spin j conditioned on the state

, after an on-resonant RF driving θrf=π to flip the nuclear spin j conditioned on the state  of spin k. Different from the case of single spins, the dimension of the spin pair is NjNk, and the corresponding population signal for two 13C is

of spin k. Different from the case of single spins, the dimension of the spin pair is NjNk, and the corresponding population signal for two 13C is  when applying θrf=π on resonant to the spin j.

when applying θrf=π on resonant to the spin j.

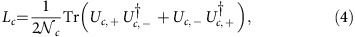

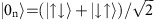

For type-d pair of homonuclear spins, the interaction takes the form  under a strong magnetic field. For the nuclear spins with spin I=1/2, the composited spin cluster has a singlet state with a composited spin J=0,

under a strong magnetic field. For the nuclear spins with spin I=1/2, the composited spin cluster has a singlet state with a composited spin J=0,  . The triplet states with J=1 are

. The triplet states with J=1 are  ,

,  , and

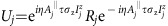

, and  . A radio frequency control

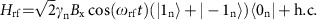

. A radio frequency control  can be written as

can be written as  . Scanning the RF frequency ωrf to the splitting between

. Scanning the RF frequency ωrf to the splitting between  and

and  , the nuclear spins are rotated. The nuclear state

, the nuclear spins are rotated. The nuclear state  has an energy of −dj,k/2 (because

has an energy of −dj,k/2 (because  ), while the energies for

), while the energies for  are ±ωn+dj,k/4, where ωn is the nuclear precession frequency shifted by the hyperfine field. Therefore, the transition frequencies between

are ±ωn+dj,k/4, where ωn is the nuclear precession frequency shifted by the hyperfine field. Therefore, the transition frequencies between  and

and  are ωn±3dj,k/4, shifted by the dipolar coupling. Different from the case of single spins that a spin flip requires a RF driving time 2π/(γnBx), here the Rabi frequency is increased and transitions between

are ωn±3dj,k/4, shifted by the dipolar coupling. Different from the case of single spins that a spin flip requires a RF driving time 2π/(γnBx), here the Rabi frequency is increased and transitions between  and

and  can be finished in a time of

can be finished in a time of  π/(γnBx). This time difference is a signature to distinguish the signals from that of single spins and of a type-h spin pair. Before a spin flip of the nuclear spin pair, the interaction Hamiltonian with the NV electronic spin reads

π/(γnBx). This time difference is a signature to distinguish the signals from that of single spins and of a type-h spin pair. Before a spin flip of the nuclear spin pair, the interaction Hamiltonian with the NV electronic spin reads  , that is,

, that is,  . After a time τ, we flip the electron spin and the nuclear triplet state, for example, with a transition

. After a time τ, we flip the electron spin and the nuclear triplet state, for example, with a transition  in a delay window, giving an effective interaction

in a delay window, giving an effective interaction  after the delay window for a time τ. The join evolution up to single qubit operations reads

after the delay window for a time τ. The join evolution up to single qubit operations reads  and the corresponding population signal

and the corresponding population signal  .

.

Data availability

The data files used to prepare the figures shown in the manuscript are available from the first corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Wang, Z.-Y. et al. Delayed entanglement echo for individual control of a large number of nuclear spins. Nat. Commun. 8, 14660 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14660 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the ERC Synergy grant BioQ, the EU projects DIADEMS, and EQUAM as well as the DFG via the SFB TRR/21. We thank Thomas Unden and Fedor Jelezko for discussions. Simulations were performed on the computational resource bwUniCluster funded by the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts Baden-Württemberg and the Universities of the State of Baden-Württemberg, Germany, within the framework program bwHPC.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions Z.-Y.W., J.C. and M.B.P. conceived the idea. Z.-Y.W. carried out the simulations and analytical work with input from J.C. and M.B.P. All authors discussed extensively on the results and contributed to the manuscript.

References

- Zhong M. et al. Optically addressable nuclear spins in a solid with a six-hour coherence time. Nature 517, 177–180 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehring M. Principle of High Resolution NMR in Solids Springer (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger A. & Jeschke G. Principles of Pulse Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Oxford (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Doherty M. W. et al. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Phys. Rep. 528, 1–45 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovitski V. V., Fuchs G. D., Falk A. L., Santori C. & Awschalom D. D. Quantum control over single spins in diamond. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 23–50 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Schirhagl R., Chang K., Loretz M. & Degen C. L. Nitrogen-vacancy centres in diamond: nanoscale sensors for physics and biology. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 65, 83–105 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.-Q., Po H. C., Du J., Liu R.-B. & Pan X.-Y. Noise-resilient quantum evolution steered by dynamical decoupling. Nat. Commun. 4, 2254 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taminiau T. H., Cramer J., van der Sar T., Dobrovitski V. V. & Hanson R. Universal control and error correction in multi-qubit spin registers in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 171–176 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldherr G. et al. Quantum error correction in a solid-state hybrid spin register. Nature 506, 204–207 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with single spin sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 5, 4703 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovchinsky I. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance detection and spectroscopy of single proteins using quantum logic. Science 351, 836–841 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Retzker A., Jelezko F. & Plenio M. B. A large-scale quantum simulator on a diamond surface at room temperature. Nat. Phys. 9, 168–173 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kolkowitz S., Unterreithmeier Q. P., Bennett S. D. & Lukin M. D. Sensing distant nuclear spins with a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 137601 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taminiau T. H. et al. Detection and control of individual nuclear spins using a weakly coupled electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 137602 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N. et al. Sensing single remote nuclear spins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 657–662 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London P. et al. Detecting and polarizing nuclear spins with nuclear double resonance on a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 067601 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sushkov A. O. et al. Magnetic resonance detection of individual proton spins using quantum reporters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 197601 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamin H. J. et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with a nitrogen-vacancy spin sensor. Science 339, 557–560 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudacher T. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a (5-nanometer)3 sample volume. Science 339, 561–563 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Wang Z.-Y. & Liu R.-B. Preserving qubit coherence by dynamical decoupling. Front. Phys. 6, 2–14 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J., Wang Z.-Y., Haase J. F. & Plenio M. B. Robust dynamical decoupling sequences for individual-nuclear-spin addressing. Phys. Rev. A 92, 042304 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.-Y., Haase J. F., Casanova J. & Plenio M. B. Positioning nuclear spins in interacting clusters for quantum technologies and bioimaging. Phys. Rev. B 93, 174104 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Laraoui A. et al. High-resolution correlation spectroscopy of 13C spins near a nitrogen-vacancy centre in diamond. Nat. Commun. 4, 1651 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loretz M. et al. Spurious harmonic response of multipulse quantum sensing sequences. Phys. Rev. X 5, 021009 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Haase J. F., Wang Z.-Y., Casanova J. & Plenio M. B. Pulse-phase control for spectral disambiguation in quantum sensing protocols. Phys. Rev. A 94, 032322 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Staudacher T. et al. Probing molecular dynamics at the nanoscale via an individual paramagnetic centre. Nat. Commun. 6, 8527 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X. et al. Towards chemical structure resolution with nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4, 024004 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Souza A. M., Álvarez G. A. & Suter D. Robust dynamical coupling. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 370, 4748–4769 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farfurnik D. et al. Optimizing a dynamical decoupling protocol for solid-state electronic spin ensembles in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 92, 060301 (R) (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Cai J.-M., Jelezko F., Plenio M. B. & Retzker A. Diamond based single molecule magnetic resonance spectroscopy. New J. Phys. 15, 013020 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ma W.-L. & Liu R.-B. Angstrom-resolution magnetic resonance imaging of single molecules via wave-function fingerprints of nuclear spins. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 024019 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Maurer P. C. et al. Room-temperature quantum bit memory exceeding one second. Science 336, 1283–1286 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. et al. High-fidelity transfer and storage of photon states in a single nuclear spin. Nat. Photon. 10, 507–511 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N., Hu J.-L., Ho S.-W., Wan J. T. K. & Liu R.-B. Atomic-scale magnetometry of distant nuclear spin clusters via nitrogen-vacancy spin in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 242–246 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi F. Z. et al. Sensing and atomic-scale structure analysis of single nuclear-spin clusters in diamond. Nat. Phys. 10, 21–25 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cramer J. et al. Repeated quantum error correction on a continuously encoded qubit by real-time feedback. Nat. Commun. 7, 11526 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N., Ho S.-W. & Liu R.-B. Decoherence and dynamical decoupling control of nitrogen vacancy centre electron spins in nuclear spin baths. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115303 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Michal C. A., Hastings S. P. & Lee L. H. Two-photon Lee-Goldburg nuclear magnetic resonance: simultaneous homonuclear decoupling and signal acquisition. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 052301 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs G. D., Dobrovitski V. V., Toyli D. M., Heremans F. J. & Awschalom D. D. Gigahertz dynamics of a strongly driven single quantum spin. Science 326, 1520–1522 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J., Wang Z.-Y. & Plenio M. B. Noise-resilient quantum computing with a nitrogen-vacancy center and nuclear spins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 130502 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L. et al. Coherence of an optically illuminated single nuclear spin qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 073001 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unden T. et al. Quantum metrology enhanced by repetitive quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 230502 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmann M. et al. Coherent control of single spins in silicon carbide at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 14, 164–168 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehollain J. P. et al. Bell's inequality violation with spins in silicon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 242–246 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maze J. R., Taylor J. M. & Lukin M. D. Electron spin decoherence of single nitrogen-vacancy defects in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 78, 094303 (2008). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References.

Data Availability Statement

The data files used to prepare the figures shown in the manuscript are available from the first corresponding author upon request.