Abstract

We investigated the associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the testis-specific Y-encoded-like protein 6 (TSPYL6) gene and breast cancer (BC) susceptibility in the Han Chinese population. A total of 183 BC patients and 195 healthy women were included in the study. Six SNPs in TSPYL6 were genotyped and the association with BC risk analyzed. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using unconditional logistic regression analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify SNPs that correlated with BC susceptibility. Rs11896604 was associated with a decreased risk of BC based on dominant and genotype models. Rs843706 was associated with an increased risk of BC based on a recessive model. Rs11125529 was associated with decreased BC susceptibility based on a genotype model. Finally, rs843711 inversely correlated with clinical stage III/IV BC. Our findings reveal a significant association between SNPs in the TSPYL6 gene and BC risk in a Han Chinese population.

Keywords: association study, breast cancer, TSPYL6, single nucleotide polymorphism

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common type of cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths among women worldwide (particularly in less developed regions including East Asian countries, which accounted for 324,000 deaths or 14.3% of the total) [1]. According to GLOBOCAN 2012, 187,213 individuals were diagnosed with BC in China in 2012, and 47,984 of these individuals died of the disease [2]. BC is a multifactorial disease that has been associated with various factors including age, gender, ethnicity, family history, personal history, lifestyle, as well as both hormonal and non-hormonal risk factors [3]. Hereditary BC clusters in families and is typically diagnosed at an earlier age [4]. Studies of twins have indicated that the risk of BC is higher for a monozygotic twin of a co-twin, suggesting that genetic factors play an important role in BC development [5]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) also play an important role in the genetic susceptibility to BC. Many genes have been associated with a moderate or high lifetime risk of BC including BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, ATM, and CHEK2. In addition, common variants at more than 70 loci have been identified through GWAS and large-scale replication studies [6–9].

The testis-specific Y-encoded-like protein 6 (TSPYL6) gene, located on human chromosome 2p16.2, is a member of the TSPY/TSPYL/SET/NAP-1 (TTSN) superfamily that includes TSPYL1, TSPYL2, TSPYL3, TSPYL4, and TSPYL5 [10]. Upregulation of TSPYL6 has been observed in both benign and malignant cells. The TSPYL6 protein has been associated with chromatin and nucleosome assembly [11]. However, the specific functions of TSPYL6 are not yet clear. Norling et al. [12] sequenced the TSPYL6 gene in an entire Sweden patient cohort, but no inactivating mutations were identified. Additionally, no studies have investigated correlations between the TSPYL6 gene and BC susceptibility. In this case-control study, we genotyped six SNPs in TSPYL6: rs843645, rs11125529, rs12615793, rs843711, rs11896604, and rs843706 and performed a comprehensive association analysis to identify SNPs associated with BC risk in Han Chinese women.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

A total of 183 patients with BC and 195 healthy individuals were enrolled in the study. The participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. No significant differences in age, body mass index (BMI), or the menopause age were observed between patients in the case and control groups (p > 0.05). The mean age of the participants was 45.35 years in the control group and 46.40 years in the case group. The mean BMI was 22.53 in the control group and 23.08 in the case group.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of the control individuals and patients with breast cancer.

| Characteristic | Cases (N = 183) | Controls (N = 195) | P -value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD | 46.40 ± 9.383 (N= 183) | 45.35 ± 6.899 (N= 195) | 0.218a | |

| Mean BMI ± SD | 23.08 ± 3.00 (N= 183) | 22.53 ± 2.55 (N = 195) | 0.056a | |

| Menopause | Premenopausal | 115 (62.8%) | 119 (61.0%) | 0.716b |

| Postmenopausal | 68 (37.2%) | 76 (39.0%) | ||

| Age of Menarche | ≤ 12 | 25 (13.7%) | ||

| > 12 | 158 (86.3%) | |||

| Breastfeeding Duration | ≤ 6 | 12 (6.5%) | ||

| > 6 | 158 (93.5%) | |||

| Clinical Stages | I/II | 135 (73.8%) | ||

| III/IV | 48 (26.2%) | |||

| Estrogen Receptor | negative | 60 (32.8%) | ||

| positive | 123 (67.2%) | |||

| Family Tumor History | no | 156 (85.2%) | ||

| yes | 27 (14.8%) | |||

| Incipientw or Recurrence | Incipient | 109 (59.9%) | ||

| Recurrence | 73 (40.1%) | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | no | 105 (58.3%) | ||

| yes | 75 (41.7%) | |||

| Menopause | no | 115 (62.8%) | ||

| yes | 68 (37.2%) | |||

| Primiparous Age | < 30 | 170 (96.6%) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 6 (3.4%) | |||

| Procreative Times | < 1 | 142 (81.1%) | ||

| ≥ 1 | 33 (18.9%) | |||

| Progestrone Receptor | negative | 75 (41.0%) | ||

| positive | 108 (59.0%) | |||

| Tumor Location | left | 84 (45.9%) | ||

| right | 97 (53.0%) | |||

| both | 2 (1.1%) | |||

| Tumor Size (cm) | ≤ 3 | 94 (51.4%) | ||

| > 3 | 89 (48.6%) | |||

| Tumor Type | carcinoma | 165 (90.2%) | ||

| others | 18 (9.8%) | |||

| Whether fertility | no | 7 (3.8%) | ||

| yes | 176 (96.2%) |

SD: Standard deviation. BMI: Body mass index (weight [kg]/height[m]2).

P value was calculated by Welch's t test.

P value was calculated by Pearson's χ2 test.

Association between TSPYL6 polymorphisms and BC risk

Detailed SNP data and the associations between various SNPs and BC risk are shown in Table 2. Our data indicated that all 6 SNPs investigated were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the control subjects (p > 0.05). No associations were observed between the alleles and BC risk in an allele model. We also performed a Bonferroni correction and determined that none of the SNPs showed statistical significant associations with BC risk.

Table 2. Basic information of candidate SNPs in this study.

| SNPs | Position | Band | AllelesA/B | MAF-control | MAF-case | HWE-p | OR | 95% CI | p-x2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs843645 | 54474664 | 2p16.2 | G/T | 0.297 | 0.279 | 0.4968 | 0.913 | 0.666–1.251 | 0.57 |

| rs11125529 | 54475866 | 2p16.2 | A/C | 0.195 | 0.150 | 0.1695 | 0.731 | 0.499–1.069 | 0.105 |

| rs12615793 | 54475914 | 2p16.2 | A/G | 0.201 | 0.161 | 0.1166 | 0.764 | 0.525–1.109 | 0.156 |

| rs843711 | 54479117 | 2p16.2 | C/T | 0.487 | 0.544 | 0.1531 | 1.254 | 0.942–1.669 | 0.12 |

| rs11896604 | 54479199 | 2p16.2 | G/C | 0.221 | 0.167 | 0.0929 | 0.707 | 0.491–1.018 | 0.062 |

| rs843706 | 54480369 | 2p16.2 | C/A | 0.482 | 0.544 | 0.06103 | 1.281 | 0.962–1.705 | 0.090 |

SNPs: Single nucleotide polymorphisms; MAF: Minor allele frequency; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Minor alleles.

Major alleles.

We further assessed the association between each SNP and BC risk in an unconditional logistic regression analysis, which was performed using four models: additive, dominant, recessive, and genotype model (Tables 3 and 4). Rs11896604 was associated with a decreased risk of BC in a dominant model (odds ratio [OR] = 0.623, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 0.405–0.958, p = 0.031). Rs843706 was associated with an increased risk of BC under the recessive model (OR = 1.709, 95% CI = 1.055–2.770, p = 0.030) (Table 3). Rs11125529 was associated with a decreased risk of BC under the genotype model (OR = 0.612, 95% CI = 0.391–0.959, p = 0.032) (Table 4). Rs11896604 was associated with a decreased risk of BC in a genotype model (OR = 0.574, 95% CI = 0.370–0.891, p = 0.013). No statistical associations were detected under the other models. In addition, no positive results were observed after Bonferroni correction.

Table 3. Single loci association with breast cancer risk (adjusted by age, BMI and menopause).

| SNP | Model | Genotype | Cases | Controls | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs843645 | Dominant model | T/T | 99 | 94 | 1 | 0.246 |

| G/G-G/T | 84 | 101 | 0.785 (0.521–1.182) | |||

| Recessive model | T/T-T/G | 165 | 180 | 1 | 0.535 | |

| G/G | 18 | 15 | 1.259 (0.608–2.606) | |||

| Additive model | - | - | - | 0.904 (0.658–1.241) | 0.532 | |

| rs11125529 | Dominant model | C/C | 133 | 123 | 1 | 0.057 |

| A/A-A/C | 50 | 72 | 0.652 (0.419–1.013) | |||

| Recessive model | C/C-C/A | 178 | 191 | 1 | 0.618 | |

| A/A | 5 | 4 | 1.413 (0.364–5.488) | |||

| Additive model | - | - | - | 0.730 (0.491–1.085) | 0.120 | |

| rs12615793 | Dominant model | G/G | 129 | 120 | 1 | 0.085 |

| A/A-A/G | 54 | 74 | 0.682 (0.441–1.054) | |||

| Recessive model | G/G-G/A | 178 | 190 | 1 | 0.625 | |

| A/A | 5 | 4 | 1.402 (0.361–5.445) | |||

| Additive model | - | - | - | 0.755 (0.510–1.117) | 0.159 | |

| rs843711 | Dominant model | T/T | 39 | 46 | 1 | 0.532 |

| C/C-C/T | 144 | 149 | 1.169 (0.405–0.958) | |||

| Recessive model | T/T-T/C | 128 | 154 | 1 | 0.066 | |

| C/C | 55 | 41 | 1.563 (0.972–2.515) | |||

| Additive model | - | - | - | 1.261 (0.937–1.700) | 0.126 | |

| rs11896604 | Dominant model | C/C | 128 | 114 | 1 | 0.031 |

| G/G-G/C | 55 | 81 | 0.623 (0.405–0.958) | |||

| Recessive model | C/C-C/G | 177 | 190 | 1 | 0.644 | |

| G/G | 6 | 5 | 1.336 (0.391–4.564) | |||

| Additive model | - | - | - | 0.709 (0.484–1.039) | 0.078 | |

| rs843706 | Dominant model | A/A | 39 | 45 | 1 | 0.603 |

| C/C-C/A | 144 | 149 | 1.140 (0.696–1.866) | |||

| Recessive model | A/A-A/C | 128 | 156 | 1 | 0.030 | |

| C/C | 55 | 38 | 1.709 (1.055–2.770) | |||

| Additive model | - | - | - | 1.294 (0.958–1.750) | 0.093 |

SNPs: Single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR: Odds ratio. CI: Confidence interval.

P value was calculated by Wald test. *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significant.

Table 4. The association between the single-nucleotide polymorphisms and BC risk in Genotype model (adjusted by age, BMI and menopause).

| Genotype | Cases | Controls | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs843645 | ||||

| TT | 99 | 94 | 1.00 [Ref] | |

| GT | 66 | 86 | 0.729 (0.475–1.117) | 0.147 |

| GG | 18 | 15 | 1.139 (0.543–2.391) | 0.730 |

| rs11125529 | ||||

| CC | 133 | 123 | 1.00 [Ref] | |

| AC | 45 | 68 | 0.612 (0.391–0.959) | 0.032 |

| AA | 5 | 4 | 1.156 (0.304–4.404) | 0.832 |

| rs12615793 | ||||

| GG | 129 | 120 | 1.00 [Ref] | |

| AG | 49 | 70 | 0.651 (0.419–1.013) | 0.057 |

| AA | 5 | 4 | 1.163 (0.305–4.432) | 0.825 |

| rs843711 | ||||

| TT | 39 | 46 | 1.00 [Ref] | |

| CT | 89 | 108 | 0.972 (0.583–1.620) | 0.913 |

| CC | 55 | 41 | 1.582 (0.879–2.848) | 0.126 |

| rs11896604 | ||||

| CC | 128 | 114 | 1.00 [Ref] | |

| GC | 49 | 76 | 0.574 (0.37–0.891) | 0.013 |

| GG | 6 | 5 | 1.069 (0.318–3.596) | 0.915 |

| rs843706 | ||||

| AA | 39 | 45 | 1.00 [Ref] | |

| CA | 89 | 111 | 0.925 (0.555–1.543) | 0.766 |

| CC | 55 | 38 | 1.670 (0.921–3.030) | 0.092 |

OR: odd ratio; CI: confidence interval;

p value was calculated by Wald test. *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

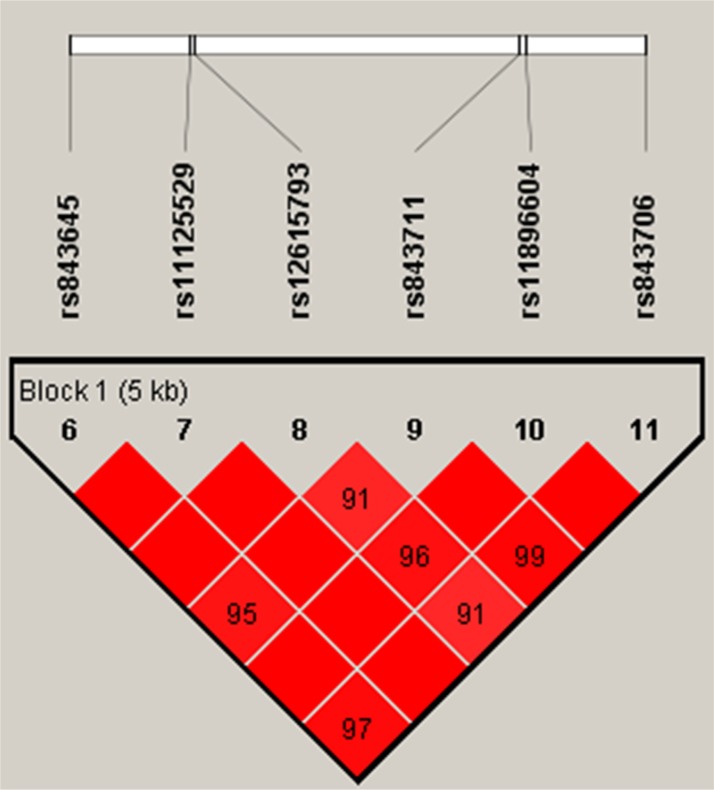

In order to assess the associations between SNP haplotypes and BC risk, a Wald test was performed using an unconditional multivariate regression analysis. However, no positive results were observed (Table 5, Figure 1).

Table 5. Haplotype frequency and their association with BC risk in case and control subjects (adjusted by age, BMI and menopause).

| SNPs | Haplotype | Freq % | P1 | OR | 95% CI | P2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| case | control | |||||||

| rs843645|rs11125529|rs12615793|rs8437 11|rs11896604|rs843706 |

TAATGA | 0.150 | 0.192 | 0.126 | 0.745 | 0.501 | 1.108 | 0.146 |

| TCGTGA | 0.016 | 0.023 | 0.510 | 0.741 | 0.256 | 2.149 | 0.581 | |

| GCGTCA | 0.276 | 0.292 | 0.619 | 0.912 | 0.662 | 1.257 | 0.574 | |

| TCGCCC | 0.530 | 0.474 | 0.126 | 1.266 | 0.939 | 1.707 | 0.122 | |

*P-value < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

P1- values were calculated from two-sided Chi-squared test.

P2 -values were calculated by unconditional logistic regression.

The reference standard for each haplotype is the other haplotype.

Figure 1. Haplotype block map for all the SNPs of the TSPYL6 gene.

Association between TSPYL6 polymorphisms and BC patient clinicopathological features

We next analyzed the association between TSPYL6 polymorphisms and BC patient clinicopathological features, which included age, age of menarche, BMI, breastfeeding duration, clinical stage, estrogen receptor status, family history of cancer, procreative time, progesterone receptor status, tumor location, tumor size (cm), tumor type, incipient recurrence, presence of lymph node metastasis, age of menopause, and prim parous age. Positive results are shown in (Table 6A, 6B). For rs11125529, we found that more recurrent BC patients had the AA + CA genotype than the CC genotype (OR = 2.321, 95% CI = 1.192–4.521, p = 0.012) (Table 6A). For rs843711, the CT + CC genotype was observed less frequently in patients with clinical stage III/IV disease (OR = 0.411, 95% CI = 0.194–0.869, p = 0.018) and in patients with recurrent BC (OR = 0.458, 95% CI = 0.222–0.944, p = 0.032) than the TT genotype (Table 6A). Our results suggested that the frequency of recurrent BC patients with the CC genotype of rs11896604 was higher than the frequency of patients with the GG + CG genotype (OR = 2.471, 95% CI = 1.290–4.734, p = 0.006) (Table 6B). Finally, the CA + CC genotype of rs843706 was more frequently observed in patients with clinical stage III/IV disease (OR = 0.411, 95% CI = 0.194–0.869, p = 0.018) and in patients with recurrent BC (OR = 0.458, 95% CI = 0.222–0.944, p = 0.032) than the AA genotype (Table 6B). No statistical associations were detected between the other loci and the clinical parameters that were investigated.

Table 6A. The Associations between TSPYL6 polymorphisms and clinical characteristics of breast cancer patients.

| Variables | rs11125529 | rs843711 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA + CA | CC | ORa | 95% CI | Pb | CT+CC | TT | ORa | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Age | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| ≤ 40 | 14 | 43 | 1 | (reference) | 41 | 16 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 40 | 36 | 90 | 1.229 | (0.600–2.515) | 0.573 | 103 | 23 | 1.748 | (0.839–3.639) | 0.133 |

| Age of Menarche | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| ≤ 12 | 5 | 20 | 1 | (reference) | 22 | 3 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 12 | 45 | 113 | 0.628 | (0.222–1.775) | 0.377 | 122 | 36 | 2.164 | (0.612–7.646) | 0.221 |

| BMI | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| ≤ 24 | 34 | 87 | 1 | (reference) | 98 | 23 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 24 | 16 | 46 | 0.89 | (0.445–1.780) | 0.742 | 46 | 16 | 0.675 | (0.326–1.397) | 0.288 |

| Breastfeeding Duration | 46 | 124 | 133 | 37 | ||||||

| ≤ 6 | 3 | 9 | 1 | (reference) | 10 | 2 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 6 | 43 | 115 | 0.891 | (0.230–3.448) | 0.868 | 123 | 35 | 1.423 | (0.298–6.797) | 0.657 |

| Clinical Stages | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| I/II | 38 | 97 | 1 | (reference) | 112 | 23 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| III/IV | 12 | 36 | 0.851 | (0.401–1.807) | 0.674 | 32 | 16 | 0.411 | (0.194–0.869) | 0.018* |

| Estrogen Receptor | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| negative | 17 | 43 | 1 | (reference) | 49 | 11 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| positive | 33 | 90 | 0.927 | (0.466–1.847) | 0.83 | 95 | 28 | 0.762 | (0.350–1.658) | 0.492 |

| Family Tumor History | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| no | 8 | 114 | 1 | (reference) | 121 | 35 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| yes | 42 | 19 | 1.143 | (0.465–2.807) | 0.771 | 23 | 4 | 1.663 | (0.539–5.031) | 0.372 |

| Procreative Times | 47 | 128 | 138 | 37 | ||||||

| < 1 | 37 | 105 | 1 | (reference) | 112 | 30 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| ≥ 1 | 10 | 23 | 0.81 | (0.353–1.862) | 0.62 | 26 | 7 | 1.005 | (0.398–2.539) | 0.991 |

| Progestrone Receptor | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| negative | 22 | 53 | 1 | (reference) | 59 | 16 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| positive | 28 | 80 | 0.843 | (0.437–1.627) | 0.611 | 85 | 23 | 1.002 | (0.488–2.058) | 0.995 |

| Tumor Location | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| left | 22 | 62 | 1 | (reference) | 66 | 18 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| right | 28 | 69 | 1 | (reference) | 77 | 20 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| both | 0 | 2 | --- | --- | 0.631 | 1 | 1 | --- | --- | 0.603 |

| Tumor Size (cm) | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| ≤ 3 | 24 | 70 | 1 | (reference) | 76 | 18 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 3 | 26 | 63 | 1.204 | (0.628–2.308) | 0.576 | 68 | 21 | 0.767 | (0.377–1.559) | 0.463 |

| Tumor Type | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| Infiltrating ductal carcinoma | 47 | 118 | 1 | (reference) | 128 | 37 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| others | 3 | 15 | 1.992 | (0.551–7.198) | 0.285 | 16 | 2 | 0.432 | (0.095–1.967) | 0.266 |

| Incipience/Recurrence | 49 | 133 | 144 | 38 | ||||||

| Incipience | 22 | 87 | 1 | (reference) | 92 | 17 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| Recurrence | 27 | 46 | 2.321 | (1.192–4.521) | 0.012* | 52 | 21 | 0.458 | (0.222–0.944) | 0.032* |

| Lymph node metastasis | 49 | 131 | 141 | 39 | ||||||

| no | 29 | 76 | 1 | (reference) | 83 | 17 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| yes | 20 | 55 | 0.953 | (0.489–1.857) | 0.887 | 58 | 22 | 0.904 | (0.442–1.851) | 0.783 |

| Menopause | 50 | 133 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| no | 27 | 88 | 1 | (reference) | 87 | 28 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| yes | 23 | 45 | 1.666 | (0.859–3.230) | 0.129 | 57 | 11 | 1.668 | (0.770–3.614) | 0.192 |

| Primiparous Age | 47 | 129 | 139 | 37 | ||||||

| < 30 | 45 | 125 | 1 | (reference) | 136 | 34 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 2 | 4 | 0.72 | (0.127–4.006) | 0.709 | 3 | 3 | 4 | (0.773–20.70) | 0.076 |

Table 6B. The Associations between TSPYL6 polymorphisms and clinical characteristics of breast cancer patients.

| Variables | rs11896604 | rs843706 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG + CG | CC | ORa | 95% CI | Pb | CA + CC | AA | ORa | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Age | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| ≤ 40 | 16 | 41 | 1 | (reference) | 41 | 16 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 40 | 39 | 87 | 1.149 | (0.576–2.291) | 0.694 | 103 | 23 | 1.748 | (0.839–3.639) | 0.133 |

| Age of Menarche | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| ≤ 12 | 6 | 19 | 1 | (reference) | 22 | 3 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 12 | 49 | 109 | 0.702 | (0.264–1.868) | 0.477 | 122 | 36 | 2.164 | (0.612–7.646) | 0.221 |

| BMI | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| ≤ 24 | 38 | 83 | 1 | (reference) | 98 | 23 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 24 | 17 | 45 | 0.825 | (0.419–1.624) | 0.578 | 46 | 16 | 0.675 | 90.326–1.397 | 0.288 |

| Breastfeeding Duration | 51 | 119 | 133 | 37 | ||||||

| ≤ 6 | 3 | 9 | 1 | (reference) | 10 | 2 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 6 | 48 | 110 | 0.764 | (0.198–2.946) | 0.695 | 123 | 35 | 1.423 | (0.298–6.797) | 0.657 |

| Clinical Stages | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| I/II | 43 | 92 | 1 | (reference) | 112 | 23 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| III/IV | 12 | 36 | 0.713 | (0.338–1.505) | 0.374 | 32 | 16 | 0.411 | (0.194–0.869) | 0.018** |

| Estrogen Receptor | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| negative | 19 | 41 | 1 | (reference) | 49 | 11 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| positive | 36 | 87 | 0.893 | (0.458–1.742) | 0.74 | 95 | 28 | 0.762 | (0.350–1.658) | 0.492 |

| Family Tumor History | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| no | 45 | 111 | 1 | (reference) | 121 | 35 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| yes | 10 | 17 | 1.151 | (0.617–3.410) | 0.391 | 23 | 4 | 1.663 | (0.539–5.131) | 0.372 |

| Procreative Times | 52 | 123 | 138 | 37 | ||||||

| < 1 | 41 | 101 | 1 | (reference) | 112 | 30 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| ≥ 1 | 11 | 22 | 0.812 | (0.361–1.824) | 0.614 | 26 | 7 | 1.005 | (0.398–2.539) | 0.991 |

| Progestrone Receptor | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| negative | 25 | 50 | 1 | (reference) | 59 | 16 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| positive | 30 | 78 | 0.769 | (0.406–1.457) | 0.42 | 85 | 23 | 1.002 | (0.488–2.058) | 0.995 |

| Tumor Location | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| left | 25 | 59 | 1 | (reference) | 66 | 18 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| right | 30 | 67 | 1 | (reference) | 77 | 20 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| both | 0 | 2 | --- | --- | 0.638 | 1 | 1 | --- | --- | 0.603 |

| Tumor Size (cm) | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| ≤ 3 | 27 | 67 | 1 | (reference) | 76 | 18 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| > 3 | 28 | 61 | 1.139 | (0.605–2.144) | 0.686 | 68 | 21 | 0.767 | (0.377–1.559) | 0.463 |

| Tumor Type | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| Infiltrating ductal carcinoma | 52 | 113 | 1 | (reference) | 128 | 37 | ||||

| others | 3 | 15 | 2.301 | (0.638–8.295) | 0.192 | 16 | 2 | 0.432 | (0.095–1.967) | 0.266 |

| Incipience/Recurrence | 54 | 128 | 144 | 38 | ||||||

| Incipience | 24 | 85 | 1 | (reference) | 92 | 17 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| Recurrence | 30 | 43 | 2.471 | (1.290–4.734) | 0.006* | 52 | 21 | 0.458 | (0.222–0.944) | 0.032* |

| Lymph node metastasis | 54 | 126 | 141 | 39 | ||||||

| no | 33 | 72 | 1 | (reference) | 83 | 22 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| yes | 21 | 54 | 0.848 | (0.442–1.627) | 0.621 | 58 | 17 | 0.904 | (0.442–1.851) | 0.783 |

| Menopause | 55 | 128 | 144 | 39 | ||||||

| no | 32 | 83 | 1 | (reference) | 87 | 28 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| yes | 23 | 45 | 1.326 | (0.694–2.532) | 0.393 | 57 | 11 | 1.668 | (0.770–3.614) | 0.192 |

| Primiparous Age | 52 | 124 | 139 | 37 | ||||||

| < 30 | 50 | 120 | 1 | (reference) | 136 | 34 | 1 | (reference) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 2 | 4 | 0.833 | (0.148–4.697) | 0.836 | 3 | 3 | 4 | (0.773–20.70) | 0.076 |

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval. OR: odds ratio.

Adjusted for Age, Age of Menarche, BMI, Breastfeeding Duration, Clinical Stages, Estrogen Receptor, Family Tumor History, Procreative Times, Progestrone Receptor, Tumor Location, Tumor Size (cm), Tumor Type, Incipient/Recurrence, Lymph node metastasis, Menopause and Primiparous Age.

Two-sided Chi-square test for the distributions of genotype frequencies.

p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the association between SNPs in the TSPYL6 gene and BC risk in Han Chinese women. We found that four SNPs (rs11896604, rs843706, rs11125529, and rs843711) were associated with the risk of BC in this population. Rs11896604 was associated with a decreased risk of BC in a dominant and genotype model, but the various genotypes were associated with an increased risk of recurrence in BC patients. An association between this locus and other diseases has not been previously reported. Rs843706 was associated with an increased risk of BC in a recessive model, but there was a decreased association between the SNP and the risk of recurrence as well as with clinical stage III/IV BC.

We are the first to demonstrate an association between this locus and BC susceptibility. Rs11125529 was associated with a decreased risk of BC in a genotype model, but an increased risk of recurrence. Although Ding et al. reported neither the genotype nor the allele frequencies at rs11125529 in ACYP2 differed significantly between coronary heart disease patients and normal controls [13]. The association between the telomere length-related variant rs11125529 in ACYP2 and gastric cancer risk was previously investigated in a Chinese population, but no significant association was identified [14]. We found that the rs843711 genotypes in the TSPYL6 gene were inversely correlated with clinical stage III/IV BC. Finally, rs843645 and rs12615793 were not associated with the risk of BC.

The function of TSPYL6 may be similar to those of other members of the TTSN superfamily. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying TSPYL6 function have not been elucidated. Mutation of TSPYL can cause sudden infant death with dysgenesis of the testes (SIDDT) in affected males, indicating that TSPYL is important for the development of the testis and other tissues such as the brain [15]. Although TSPYL is expressed in all tissues [16], the role of TSPYL in tumor cells is not clear. The TSPYL4 gene is located 25 kb from TSPYL, however no coding variants were identified in affected individuals with direct sequencing. The TSPYL1 gene does not contain any introns, but the exact composition has not been determined [17].

TSPYL2 gene and cyclin B can inhibit cell proliferation by arresting cell growth in response to DNA damage [18]. Thus, it has been suggested that TSPYL2 is a negative regulator of cell cycle progression. The TSPYL2 gene is silenced in glioma and malignant lung tissue, and in certain lung cancer cell lines [19]. Overexpression of TSPYL2 can inhibit human lung and breast cancer cell lines [20]. However, there is limited evidence for a direct function of TSPYL2 in cell cycle control. Interestingly, the TSPYL5 gene has been reported to suppress gastric cancer development [21]. Further studies are required to characterize the function of TSPYL6 and elucidate the mechanisms underlying the association between the TSPYL6 and BC susceptibility. Currently, the relationship between clinical characteristics in BC patients and TSPYL6 gene expression/function is not clear.

Our study is the first to demonstrate that polymorphisms in TSPYL6 affect the pathogenesis of BC and are associated with clinicopathological characteristics of BC patients. Collectively, the results provide insight into the pathogenesis of BC. Although this study had sufficient statistical power, there were still some intrinsic limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small (183 cases and 195 controls). Therefore, our findings must be confirmed in studies with larger sample sizes as well as in a meta-analysis. Additionally, we only analyzed Han Chinese women. Therefore, our results must be validated in studies of other populations. Finally, although we identified significant associations between four SNPs (rs11896604, rs843706, rs11125529, and rs843711) and BC susceptibility, the mechanisms responsible for the associations are still unclear. Further studies of TSPYL6 and other members of the TTSN superfamily are necessary to dissect the mechanisms by which polymorphisms in these genes contribute to BC risk. Hereditary, endocrine, environmental, and life style factors should be also considered.

We performed Bonferroni correction in our statistical analysis, but found no statistical significant associations between TSPYL6 SNPs and risk of BC. This may be due to the relatively small sample size, the selection criteria for TSPYL6 SNPs (minor allele frequency [MAF] > 5%), and the weakness of Bonferroni correction itself (the interpretation of a finding depends on the number of other tests performed). True differences may have been deemed non-significant given the likelihood of type II errors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

A total of 183 patients with BC and 195 healthy women were included in this study. The patients were treated at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiao Tong University between January 2013 and November 2015. All demographic and related clinical data including residential region, age, ethnicity, and education status were collected through a face-to-face questionnaire and a review of medical records. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Patients who had been recently diagnosed with primary BC (confirmed by histopathological analysis) were included in the study. Patients diagnosed with other types of cancers or who underwent radiotherapy or chemotherapy were excluded. Control patients who had undergone annual health evaluations were recruited from health checkup centers affiliated with our institution. All controls were matched with cases based on age (p = 0.218) and ethnicity. All control patients had no history of cancer. Factors that could influence the mutation rate were minimized. The participants were women who were ≥ 18 years old with good mental health and no blood relatives with BC going back three generations. This study was performed in accordance with the Chinese Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human research subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Xi'an Jiao Tong University.

SNP selection and genotyping

Validated SNPs that had a MAF > 5% in the HapMap Asian population were selected for the association analysis [12, 20, 22, 23]. Venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected from each patient during a laboratory examination. DNA was extracted from whole blood samples using the Gold Mag-Mini Whole Blood Genomic DNA Purification Kit (version 3.0; TaKaRa, Japan) [24]. The DNA concentration was measured by spectrometry (DU530 UV/VIS spectrophotometer, Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA). The Sequenom MassARRAY Assay Design 3.0 software (Sequenom, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to design the multiplexed SNP Mass EXTEND assay. Genotyping was performed using a Sequenom MassARRAY RS1000 (Sequenom, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol [25]. The SequenomTyper 4.0 Software™ (Sequenom, Inc.) was used to manage and analyze the data [26]. The primers corresponding to each SNP are shown in Table 7. Based on these results, the following six SNPs were selected: rs843645, rs11125529, rs12615793, rs843711, rs11896604, and rs843706. The SNP data are shown in Table 3.

Table 7. Primers used for this study.

| SNP_ID | 1st-PCRP | 2nd-PCRP | UEP_SEQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs843645 | ACGTTGGATGGAAATCTGA ATACCACCTAC | ACGTTGGATGACAGTGCCTTTA GCAAGGTG | TCATAGGCACTACT GTATC |

| rs11125529 | ACGTTGGATGGAGCTTAGTT GTTTACAGATG | ACGTTGGATGCCGAAGAAAAG AAGATGAC | AGAAAAGAAGATG ACTAAAACAT |

| rs12615793 | ACGTTGGATGTTTGAGCTTAG TTGTTTAC | ACGTTGGATGATCTTGGCCCTT GAAGAA | AAATTGAGTGACAA| ATATAAACTAC |

| rs843711 | ACGTTGGATGGACAAAGGACC TTACAACTC | ACGTTGGATGTGCCTTGTGGGA ATTAGAGC | gggaTCAGGGAACCA GTGCAAA |

| rs11896604 | ACGTTGGATGAAGTCAGAATA GTGCTTAC | ACGTTGGATGTGTCTCTGACCT AGCATGTA | GTTAAGCTTGCAA GGAG |

| rs843706 | ACGTTGGATGTGAAAGCCAT AAATATTTTG | ACGTTGGATGTGAATAACTTGG TCTTATC | cACTTGGTCTTATCT GATGC |

Statistical analysis

Chi-squared tests (categorical variables) and Student's t-tests (continuous variables) were used to evaluate the differences in the demographic characteristics between the cases and controls [27]. The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium of each SNP was assessed in order to compare the expected frequencies of the genotypes in the control patients. All of the minor alleles were regarded as risk alleles for BC susceptibility. To evaluate associations between the SNPs and risk of BC in the four models (genotype, dominant, recessive, and additive), ORs and 95% CIs were calculated using unconditional logistic regression analysis [28]. In multivariate analyses, unconditional logistic regression was used to assess the association between each SNP and the risk of BC after adjusting for BMI, age, and menopause [28]. Linkage disequilibrium analysis and SNP haplotypes were analyzed using the Haploview software package (version 4.2) and the SHEsi software platform (http://www.nhgg.org/analysis/) [29]. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 17.0 statistical package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and Microsoft Excel. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and all statistical tests were two-sided.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have identified four novel associations between SNPs (rs11896604, rs843706, rs11125529, and rs843711) in TSPYL6 and BC. Our results suggest that these SNPs may contribute to BC development and possibly other complex genetic traits. These SNPs may function as molecular markers of BC susceptibility, and could therefore be used as diagnostic and prognostic markers in clinical studies of BC patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND FUNDING

This work was supported by Shaanxi province science and technology research projects (No. S2015YFSF0310). The authors are also grateful to the patients and control individuals for their participation in the study. We thank the clinicians and hospital staff who contributed to sample and data collection for this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou L, He N, Feng T, Geng TT, Jin TB, Chen C. Association of five single nucleotide polymorphisms at 6q25. 1 with breast cancer risk in northwestern China. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:2467–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michailidou K, Beesley J, Lindstrom S, Canisius S, Dennis J, Lush MJ, Maranian MJ, Bolla MK, Wang Q, Shah M, Perkins BJ, Czene K, Eriksson M, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of more than 120,000 individuals identifies 15 new susceptibility loci for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47:373–380. doi: 10.1038/ng.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michailidou K, Beesley J, Lindstrom S, Canisius S, Dennis J, Lush MJ, Maranian MJ, Bolla MK, Wang Q, Shah M, Perkins BJ, Czene K, Eriksson M, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of more than 120,000 individuals identifies 15 new susceptibility loci for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47:373–380. doi: 10.1038/ng.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peto J, Mack TM. High constant incidence in twins and other relatives of women with breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2000;26:411–414. doi: 10.1038/82533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Closas M, Couch FJ, Lindstrom S, Michailidou K, Schmidt MK, Brook MN, Orr N, Rhie SK, Riboli E, Feigelson HS, Le Marchand L, Buring JE, Eccles D, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify four ER negative-specific breast cancer risk loci. Nat Genet. 2013;45:392–398. doi: 10.1038/ng.2561. 398e391–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bojesen SE, Pooley KA, Johnatty SE, Beesley J, Michailidou K, Tyrer JP, Edwards SL, Pickett HA, Shen HC, Smart CE, Hillman KM, Mai PL, Lawrenson K, et al. Multiple independent variants at the TERT locus are associated with telomere length and risks of breast and ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:371–384. doi: 10.1038/ng.2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milne RL, Burwinkel B, Michailidou K, Arias-Perez JI, Zamora MP, Menendez-Rodriguez P, Hardisson D, Mendiola M, Gonzalez-Neira A, Pita G, Alonso MR, Dennis J, Wang Q, et al. Common non-synonymous SNPs associated with breast cancer susceptibility: findings from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6096–6111. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Q, Zhang B, Sung H, Low SK, Kweon SS, Lu W, Shi J. Genome-wide association analysis in East Asians identifies breast cancer susceptibility loci at 1q32.1, 5q14.3 and 15q26.1. 2014;46:886–890. doi: 10.1038/ng.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinci G, Brauner R, Tar A, Rouba H, Sheth J, Sheth F, Ravel C, McElreavey K, Bashamboo A. Mutations in the TSPYL1 gene associated with 46, XY disorder of sex development and male infertility. Fertil steril. 2009;92:1347–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schayek H, Bentov I, Jacob-Hirsch J, Yeung C, Khanna C, Helman LJ, Plymate SR, Werner H. Global Methylation Analysis Identifies PITX2 as an Upstream Regulator of the Androgen Receptor and IGF-I Receptor Genes in Prostate Cancer. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44:511–519. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norling A, Hirschberg AL, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Iwarsson E, Wedell A, Barbaro M. Identification of a duplication within the GDF9 gene and novel candidate genes for primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) by a customized high-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization platform. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England) 2014;29:1818–1827. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding H, Yan F, Zhou LL, Ji XH, Gu XN, Tang ZW, Chen RH. Association between previously identified loci affecting telomere length and coronary heart disease (CHD) in Han Chinese population. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:857–861. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S60760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du J, Zhu X, Xie C, Dai N, Gu Y, Zhu M, Wang C, Gao Y, Pan F, Ren C, Ji Y, Dai J, Ma H, et al. Telomere length, genetic variants and gastric cancer risk in a Chinese population. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:963–970. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puffenberger EG, Hu-Lince D, Parod JM, Craig DW, Dobrin SE, Conway AR, Donarum EA, Strauss KA, Dunckley T, Cardenas JF, Melmed KR, Wright CA, Liang W, et al. Mapping of sudden infant death with dysgenesis of the testes syndrome (SIDDT) by a SNP genome scan and identification of TSPYL loss of function. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11689–11694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401194101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grasberger H, Bell GI. Subcellular recruitment by TSG118 and TSPYL implicates a role for zinc finger protein 106 in a novel developmental pathway. Int J Biochem Cell B. 2005;37:1421–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javaher P, Stuhrmann M, Wilke C, Frenzel E, Manukjan G, Grosshenig A, Dechend F, Schwaab E, Schmidtke J, Schubert S. Should TSPYL1 mutation screening be included in routine diagnostics of male idiopathic infertility? Fertil Steril. 2012;97:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu Y, Wu W, Wu T, Cao Z, Wilkins R, Toh BH, Cooper ME, Chai Z. Antiproliferative autoantigen CDA1 transcriptionally up-regulates p21(Waf1/Cip1) by activating p53 and MEK/ERK1/2 MAPK pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11722–11731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim TY, Zhong S, Fields CR, Kim JH, Robertson KD. Epigenomic profiling reveals novel and frequent targets of aberrant DNA methylation-mediated silencing in malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7490–7501. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandalaft LE, Zudaire E, Portal-Nunez S, Cuttitta F, Jakowlew SB. Differentially expressed nucleolar transforming growth factor-beta1 target (DENTT) exhibits an inhibitory role on tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1282–1289. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim EJ, Lee SY, Kim TR, Choi SI, Cho EW, Kim KC, Kim IG. TSPYL5 is involved in cell growth and the resistance to radiation in A549 cells via the regulation of p21(WAF1/Cip1) and PTEN/AKT pathway. Biochem Bioph Res C. 2010;392:448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Zou L, Li Q, Haibe-Kains B, Tian R, Li Y, Desmedt C, Sotiriou C, Szallasi Z, Iglehart JD, Richardson AL, Wang ZC. Amplification of LAPTM4B and YWHAZ contributes to chemotherapy resistance and recurrence of breast cancer. Nat Med. 2010;16:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nm.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu G, Chong RA, Yang Q, Wei Y, Blanco MA, Li F, Reiss M, Au JL, Haffty BG, Kang Y. MTDH activation by 8q22 genomic gain promotes chemoresistance and metastasis of poor-prognosis breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carracedo An. Forensic DNA typing protocols. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabriel S, Ziaugra L, Tabbaa D. SNP genotyping using the Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform. Haines Jonathan L, et al., editors. Current protocols in human genetics. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0212s60. Chapter 2:Unit 2 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas RK, Baker AC, Debiasi RM, Winckler W, Laframboise T, Lin WM, Wang M, Feng W, Zander T, MacConaill L, Lee JC, Nicoletti R, Hatton C, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:347–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamec C. [Example of the Use of the Nonparametric Test. Test X2 for Comparison of 2 Independent Examples] Ceskoslovenske zdravotnictvi. 1964;12:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes. The odds ratio. Bmj. 2000;320:1468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi YY, He L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. 2005;15:97–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]